Abstract

Introduction: In the last few decades, there has been a rapid development in cancer therapies and improved detection strategies, hence the death rates caused by cancer have decreased. However, it has been reported that cardiovascular disease has become the second leading cause of long-term morbidity and fatality among cancer survivors. Cardiotoxicity from anticancer drugs affects the heart’s function and structure and can occur during any stage of the cancer treatments, which leads to the development of cardiovascular disease.

Objectives: To investigate the association between anticancer drugs for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and cardiotoxicity as to whether: different classes of anticancer drugs demonstrate different cardiotoxicity potentials; different dosages of the same drug in initial treatment affect the degree of cardiotoxicity; and accumulated dosage and/or duration of treatments affect the degree of cardiotoxicity.

Methods: This systematic review included studies involving patients over 18 years old with NSCLC and excluded studies in which patients’ treatments involve radiotherapy only. Electronic databases and registers including Cochrane Library, National Cancer Institute (NCI) Database, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, ClinicalTrials.gov and the European Union Clinical Trials Register were systematically searched from the earliest available date up until November 2020. A full version protocol of this systematic review (CRD42020191760) had been published on PROSPERO.

Results: A total of 1785 records were identified using specific search terms through the databases and registers; 74 eligible studies were included for data extraction. Based on data extracted from the included studies, anticancer drugs for NSCLC that are associated with cardiovascular events include bevacizumab, carboplatin, cisplatin, crizotinib, docetaxel, erlotinib, gemcitabine and paclitaxel. Hypertension was the most reported cardiotoxicity as 30 studies documented this cardiovascular adverse event. Other reported treatment-related cardiotoxicities include arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, cardiac arrest, cardiac failure, coronary artery disease, heart failure, ischemia, left ventricular dysfunction, myocardial infarction, palpitations, and tachycardia.

Conclusion: The findings of this systematic review have provided a better understanding of the possible association between cardiotoxicities and anticancer drugs for NSCLC. Whilst variation is observed across different drug classes, the lack of information available on cardiac monitoring can result in underestimation of this association.

Systematic Review Registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020191760, identifier PROSPERO CRD42020191760.

Keywords: anticancer drugs, cancer treatments, cardiotoxicity, cardiovascular events, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

1 Introduction

The WHO’s Global Health Estimates reported that lung cancer and heart diseases are two of the major causes of death in the world (World Health Organization, 2020). Due to drug development in cancer therapies and early detection strategies, death rates from cancer have decreased over the last 30 years (Jemal et al., 2010; 2005; Howlader et al., 2010). However, even though survival rates have improved, cardiovascular (CV) disease has become the second leading cause of long-term morbidity and fatality among cancer survivors (DeSantis et al., 2014; Bodai, 2019). Therefore, the risk of cardiotoxicity is one of the major limitations of oncology drug development, due to drug-induced cardiotoxic complications (Csapo and Lazar, 2014).

According to the GLOBOCAN 2020 database released by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), it was estimated that there were 19.3 million new cancer cases and 10 million cancer deaths worldwide in 2020 alone (Ferlay et al., 2020). In recent years, there has been a breakthrough in the development of novel targeted oncology drugs. According to the Global Oncology Trends 2021, 17 new oncology therapeutic drugs were launched in 2020 alone for 22 different applications with capmatinib being the first therapy approved for targeting metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) exon 14 skipping while both pralsetinib and selpercatinib approved for rearranged during transfection (RET)-altered NSCLC (IQVIA, 2021).

Cardio-oncology is a field that focuses on the CV diseases in cancer patients and addresses the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cardiotoxicity brought about by oncology drugs or radiotherapy. Chemotherapy aims to destroy the maximum number of tumour cells with minimal damage to other healthy tissues. However, this can be difficult to achieve due to the non-selectivity of chemotherapeutics (Bursác, 2018). Cardiotoxicity can occur during any stage of the cancer treatments and it includes, but is not limited to, subclinical myocardial toxicity, ischemia, hypertension, supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, systolic and diastolic cardiac dysfunction, coronary artery disease and heart failure (Hahn et al., 2014; Ewer and Ewer, 2015; Curigliano et al., 2016). Cardiotoxicity was first observed in 1967 in treating leukaemia patients with daunomycin (a type of anthracycline) (Tan et al., 1967). More reports on cardiotoxicity induced by anthracycline emerged in the early 1970s. Thereafter, there has been an increasing number of reports of cardiotoxicity induced by different oncology drugs, e.g., trastuzumab, cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide (Gollerkeri et al., 2001; Moslehi, 2016).

Cardiotoxicity can be generally defined in two ways, according to time of onset or mechanisms. Based on the time cardiotoxicity occurs after receiving chemotherapy, it can be divided into acute (during and up to 2 weeks after chemotherapy), subacute (2–4 weeks after chemotherapy) and chronic (more than 4 weeks after the completion of course) (Bursác, 2018). Chronic cardiotoxicity can be further divided into two types: early onset (cardiotoxicity developing within the first year after chemotherapy); and late onset (cardiotoxicity developing years after the completion of chemotherapy). Initially, there are two types of cardiotoxicity when categorised by mechanisms—Type I is often caused by anthracyclines and chemotherapeutics, of irreversible cardiac cells death and is related to cumulative dosage; while Type II is usually caused by biological or target therapy, of reversible cells dysfunction and is not dose related (Bursác, 2018). Although Type I versus Type II cardiotoxicity was originally described, increasingly more nuanced mechanisms and types of cardiotoxicity have been identified (Tocchetti et al., 2019).

Existing studies suggested that different oncology drugs, even within the same class of drugs, demonstrate different cardiotoxicity potential (Kerkelä et al., 2006; Santoni et al., 2017; Shah et al., 2018). For instance, by blocking the activity of tyrosine kinase, nintedanib prevents the formation of collagen and other extracellular matrix components in the heart, which can lead to cardiotoxicity. In addition, nintedanib may also act directly on the heart, leading to cardiotoxicity. It is believed that the drug can increase the activity of the Na+/K+-ATPase enzyme, which can lead to a decrease in cardiac output. This decrease in cardiac output can lead to arrhythmias, myocardial infarction, decreased contractility, and even heart failure (Ameri et al., 2021). Both sunitinib and sorafenib are in the same class as nintedanib, but they are believed to induce vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFR) inhibition, which lead to a decreased production of the vasorelaxant nitric oxide by endothelial cells, thus resulting in hypertension (Wu et al., 2008; León-Mateos et al., 2015).

There are many studies on complications, including cardiotoxicity, relating to thoracic surgery and radiotherapy complications, however there is much less research on the clinical and prognostic impact of toxicity of systemic therapy in non-small cell lung cancer (Zaborowska-Szmit et al., 2020). Therefore, this systematic review aimed to investigate associations between oncology drugs used in the treatment of NSCLC and cardiotoxicity. It also investigated whether different classes of drugs, e.g., anthracyclines, alkylating agents, angiogenesis inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), and monoclonal antibodies, demonstrate different cardiotoxicity potential. In addition, it aimed to examine whether different dosages of the same drug in initial treatment affect the degree of cardiotoxicities and whether accumulated dosage and/or duration of treatments affect the degree of cardiotoxicities.

2 Methods

This systematic review followed the guideline recommended in the ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’ 2020 statement (Page et al., 2021a; Page et al., 2021b). A full version protocol of this systematic review has been published on PROSPERO (CRD42020191760) (Chan et al., 2020).

2.1 Search strategy

Electronic databases including Cochrane Library, National Cancer Institute (NCI) Database, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science were searched for articles reporting clinical trials of cytotoxic drugs where cardiotoxicity was being observed in NSCLC patients. ClinicalTrials.gov and the European Union (EU) Clinical Trials Register were also used to search for recently completed trials. The reference lists of retrieved papers were also hand-searched. All databases and registers were searched from the earliest available date up until November 2020. This time frame was chosen given cardiotoxicity was first observed in 1967 with the use of daunomycin in leukaemia patients (Tan et al., 1967) and more reports on cardiotoxicity induced by anthracyclines emerged in the early 1970s. In addition, from 1997 onwards, there has been a rapid development in targeted treatments and immunotherapies.

Two reviewers (SHYC and YK) independently screened all the articles according to the eligibility criteria until the final list of articles to be reviewed was identified. SHYC and YK independently reviewed all final set of identified articles meeting the eligibility criteria. SHYC extracted all data using the agreed template. SS acted as an adjudicator when there was discrepancy between the two independent reviewers.

2.2 Eligibility criteria

This review included studies of patients of ≥18 years old with NSCLC and excluded studies of participants whose treatments involved multiple cancers or radiotherapy only. Only completed clinical trials including at least two arms were included. Other types of studies and reports, e.g., observational studies and conference abstracts were excluded. Observational studies were excluded as they are more prone to bias and confounding associated with their study design than that of randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Participants and/or studies without dosage details and duration of treatments were also excluded. Only records reported in English were included.

2.3 Search term

(“non-small cell lung cancer”) AND (“chemotherapy” OR “targeted therapy” OR “immunotherapy” OR “cancer treatment” OR “systemic anticancer therapy” OR “anticancer”) AND (“cardiac adverse events” OR “cardiovascular events” OR “cardiotoxicity” OR “drug-related side effects and adverse reactions”).

2.4 Data extraction

The standardised data extraction tool from Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool was adopted for data extraction. Data items were collected under three main areas—setting, participants and outcome.

Setting—“Title of Paper”, “Name of Authors”, “Publication Year”, “Reporting Country”, “Aim of Study”, “Primary Objective”, “Secondary Objectives”, “Study Design”, “Unit of Allocation”, “Enrolment Start Date”, “Enrolment End Date”, “Follow-Up End Date”, “Ethics Approval”, “Clinical Trial Identifier/Registration Number”.

Participants—“Population Description”, “Inclusion Criteria”, “Exclusion Criteria’, “Informed Consent”, “Method of Recruitment”, “Total Number of Cluster Groups, “Total Number of Participants”, “Age”, “Sex”, “Severity of Illness”, “Co-Morbidities”, “Subgroups Measured”, “Name of NSCLC Drug”, “Mode of Administration”, “Dosage Details”, “Duration of Treatment”, “Frequency of Treatment” and “Delivery of Treatment”.

Outcome—“Overall Incidence of Cardiotoxicity”, “Type of Cardiotoxicity”, “Incidence of Each Type of Cardiotoxicity” and “Key Conclusion from Authors”.

Data items were repeatedly collected for each individual placebo or treatment arm where relevant. All data items were input into Microsoft Excel®, where each row represented one publication. If certain data items were not available within the publication, then the data and results listed under its corresponding clinical trial identifier were cross-checked to complete the data extraction.

2.5 Risk of bias in individual studies

The risk of bias assessment in individual studies was carried out according to the guideline listed in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al., 2022).

The following criteria were assessed –

– Allocation bias: Allocation concealment

– Attrition bias: Incomplete outcome data

–Performance and detection bias: Blinding of participants, Blinding of outcome assessors

– Reporting bias: Selective reporting

– Selection bias: Random sequence generation

3 Results

3.1 Results of literature search

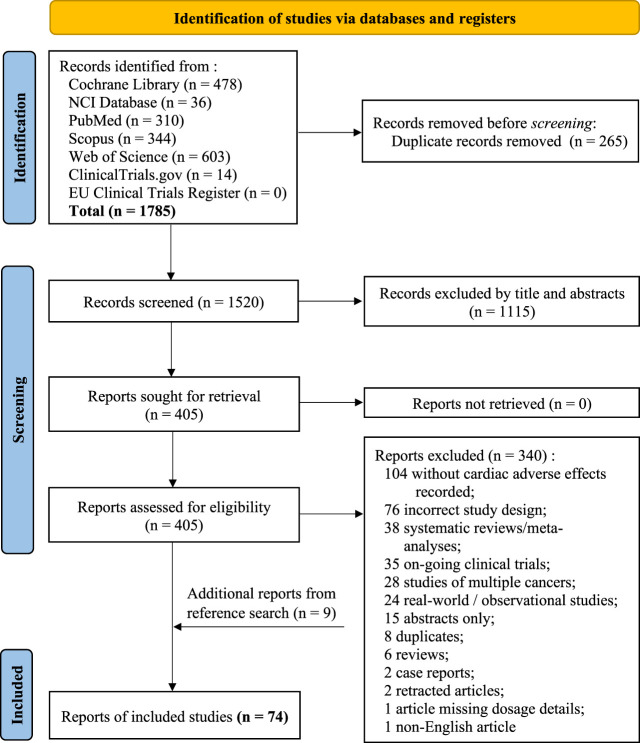

A total of 1785 records were identified from the seven databases and registers using the search term listed in ‘Methods’. This search time frame (earliest available date up until November 2020) was used in order to maximise the records identified as cardiotoxicity was first observed in 1967 in treating leukaemia patients with daunomycin and more reports on cardiotoxicity induced by anthracycline emerged in the early 1970s. A PRISMA 2020 flow diagram explaining the selection process for this systematic review is presented in Figure 1. A total number of 74 eligible studies were included for data extraction. A summary of the study design, patient population and NSCLC drugs used for all publication is listed in Table 1. Treatment details and patients’ characteristics of each eligible study are available in Supplementary Material S1. Table 2 demonstrates the types of cardiotoxicities and their corresponding number of occurrences reported per publication.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for this new systematic review which included searches of databases and registers only.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the study design, patient population and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) drug used for each publication.

| References (publication year) | Clinical trial identifier | Reporting country | Study design | Total number of cluster groups | Total number of patients | Age, median (range) | Sex (M/F) | Severity of Illness/NSCLC stage | Co-morbidities | Subgroups measured | Drugs involved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mizugaki et al. (2015) | NCT01617928 | Japan | Open-label, Phase I Study | 3 | 12 | 67 (44–73 years old) | 10M 2F | Stage IIIIB, Stage IV, Postoperative recurrence | Smoker status | Dose | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Veliparib |

| Huang et al. (2020) | NCT03201146 | China | Phase I Study | 3 | 12 | 53.4 (42.2–63.4 years old) | 7M 5F |

Stage IVA, Stage IVB |

Smoker status | Dose | Apatinib, Carboplatin, Pemetrexed |

| Sebastian et al. (2019) | N/A | Germany & Switzerland | Prospective, multicenter, open-label, uncontrolled phase I/IIa trial | 4 | 46 | 64.7 (SD: 10.2) | 29M 1 7F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | Dose | CV9201 (generated using proprietary RNActive® Technology) |

| Novello et al. (2014a) | NCT01086254 | Italy, France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom | Phase II, randomized, open-label, non-comparative study | 2 | 119 | 58.7 (29–73 years old) | 90M 29F | Stage I, Stage III, Stage IV |

Smoker status | N/A | Cisplatin, Iniparib, Gemcitabine |

| Cappuzzo et al. (2006) | N/A | Italy | Phase II, randomized Study | 2 | 117 | 72.5 (54–81 years old) | 98M 19F | Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

N/A | Infusion Duration | Chemotherapy, Gemcitabine |

| Srinivasa et al. (2020) | N/A | India | Randomized prospective study | 2 | 36 | 57 (45–65 years old) | 33M 3F | Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB | N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Etoposide, Paclitaxel |

| Yoshioka et al. (2017) | NCT01207011 | Japan | Randomized, open-label, phase III trial | 2 | 197 | 20–75 years old | 135M 62F |

Stage IIIIB, Stage IV, Postoperative recurrence | Smoker status | N/A | Amrubicin, Docetaxel |

| Johnson et al. (2013) | NCT00257608 | United States | Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase IIIB Trial | 2 | 743 | 64 (23–88 years old) | 389M, 354F | Stage IIIB, Stage IV, Recurrent | Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Erlotinib (Chemotherapy prior to trial) |

| EU Clinical Trials Register. (2011) | MEK114653 (EU Clinicals Register) | France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, United States | Phase II, Open-label, Multicenter, Randomized Study | 2 | 134 (4 drop out) | 61.2 (18–64 years old) | 69M, 65F | Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | Crossover Phase | Docetaxel, GSK1120212 |

| Gridelli et al. (2001) | N/A | Italy | Pilot Single-Stage Phase II Study | 2 | 98 | 74 (70–82 years old) | 83M, 15F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | N/A | Gemcitabine, Vinorelbine |

| Martoni et al. (1991) | N/A | Italy | Phase I Trial | 4 | 24 | 60 (36–68 years old) | 24M, 0F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

N/A | Dose, LVEF values |

Epirubicin |

| Sequist et al. (2013), Boehringer Ingelheim (2018a), Wu et al. (2018) | NCT00949650 (LL3) | Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Peru, Philippines, Romania, Russia, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States | Global, randomized, open-label phase III study | 2 | 345 | 60.3 (S.D. 10.1 years old) | 121M, 224F | Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Afatinib, Cisplatin, Pemetrexed |

| Boehringer Ingelheim, (2018a) Boehringer Ingelheim. (2018b) | NCT01121393 | China, South Korea, Thailand | Randomized, Open-label, Phase III Study | 2 | 364 | 56.4 (SD: 10.9) | 126M, 238F | Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Afatinib (BIBW2992), Cisplatin, Gemcitabine |

| Boehringer Ingelheim (2020) | NCT01466660 | Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Ireland, Norway, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, United Kingdom | Randomised, Open-label Phase IIB Trial | 2 | 319 | 62.4 (SD: 11.0) | 122M, 197F | Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Afatinib, Gefitinib |

| Hida et al. (2017) | JapicCTI-132316 (Japan Pharmaceutical Information Centre) | Japan | Phase III, Open-label, Multicenter, Randomised Trial | 2 | 207 | 60.2 (25–85 years old) | 82M, 125F |

Stage IIIIB, Stage IV, Postoperative recurrence | Smoker Status | N/A | Alectinib, Crizotinib |

| Berghmans et al. (2013) | NCT00622349 | Belgium, France, Greece, Spain | Phase III Trial | 3 | 693 | 58 (28–84 years old) | 523M,170F | Stage IIB, Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | N/A | Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Gemcitabine, Ifosfamide |

| GlaxoSmithKline (2014) | NCT01362296 | France, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, United States | Phase II, Open-label, Multicenter, Randomised Trial | 2 | 134 | 61.2 (SD: 9.32) | 69M, 65F |

Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Docetaxel, GSK1120212 (Trametinib) |

| Martoni et al. (1999) | N/A | Italy | Pilot Study | 2 | 212 | 61 (42–72 years old) | 179M, 33F | Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB, Stage IV, Recurrence | N/A | N/A | Epirubicin, cisplatinum, vinorelbine |

| Reck et al. (2015) | NCT00805194 | Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, China, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, India, Israel, Italy, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Ukraine, United Kingdom | Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase III trial | 2 | 1314 | 59.8 | 955M, 359F |

<Stage IIIB, Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Docetaxel, Nintedanib |

| Saito et al. (2003) | N/A | Japan | Parallel | 2 | 25 | 61.8 (40–79 years old) | 16M, 9F |

Stage III, Stage IV |

N/A | LVEF | Carboplatin, Docetaxel, Paclitaxel |

| Barlesi et al. (2018) | NCT02395172 | Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, Colombia, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Mexico, Peru, Poland, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, United Kingdom, and United States | Open-label, multicentre, randomised Phase III trial | 2 | 792 | 63.5 (57–69 years old) | 542M 250F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV, Recurrent NSCLC with disease progression after previous platinum doublet treatment> |

Smoker Status | N/A | Avelumab, Docetaxel |

| Camidge et al. (2018) | NCT02737501 | Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, South Korea, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, United Kingdom, United States | Open-label, multicenter, randomized, international, Phase III trial | 2 | 275 | 59 (27–89 years old) | 125M 150F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Brigatinib, Crizotinib |

| Wachters et al. (2004) | N/A | Netherlands | Randomised phase III trial | 2 | 69 | 61 (43–76 years old) | 49M 20F |

Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB Stage IV |

N/A | LVEF | Cisplatin, Epirubicin, Gemcitabine |

| Shaw et al. (2013) | NCT00932893 | Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, China, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Poland, Russian Federation, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, United Kingdom, United States | Phase 3, Randomized, Open-label Study | 2 | 347 | 50 (22–85 years old) | 154M 193F | Advanced | Smoker Status | N/A | Crizotinib (PF-02341066), Docetaxel, Pemetrexed |

| Solomon et al. (2014) | NCT01154140 | Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, China, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Peru, Portugal, Russian Federation, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States | Phase 3, Randomized, Open-label Study | 2 | 343 | 53 (19–78 years old) | 131M 212F |

Advanced | Smoker Status | N/A | Crizotinib, Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Pemetrexed |

| Bonomi et al. (2000) | N/A | United States | A Phase III Study | 3 | 574 | 61.8 | 365M 209F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | Dose | Cisplain, Etoposide, Paclitaxel |

| Zatloukal et al. (2004) | N/A | Czech Republic | Prospective, randomized open, parallel group study | 2 | 102 | 61.5 (42–75 years old) | 69M 33F |

Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB |

N/A | N/A | Cisplatin, Vinorelbine |

| Zarogoulidis et al. (2013) | N/A | Greece | Four-arm Phase III Trial | 4 | 229 | 62.5 | 187M 37F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Docetaxel, Erlotinib |

| Koch et al. (2011) | NCT00300729 | Sweden | Double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre Phase III Trial | 2 | 316 | 65.5 (37–85 years old) | 160M 156F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Celecoxib, Chemotherapy (carboplatin/cisplatin/gemcitabine/vinorelbine) |

| Bi et al. (2019) | NCT01503385 | China | A Phase II Randomized Clinical Trial | 2 | 96 | 60 | 73M 23F |

Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB |

Smoker Status | N/A | Celecoxib, Cisplatin, Etoposide |

| Herbst et al. (2011) | NCT00130728 | 12 countries including United States | Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled, Randomised Phase 3 trial | 2 | 636 | 64.9 | 341M 295F |

N/A | Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Erlotinib |

| Kato et al. (2018); Seto et al. (2014) | JapicCTI-111390 (Japan Pharmaceutical Information Centre) | Japan | Open-label, randomised, multicentre, Phase II Study | 2 | 152 | 67 (59–73 years old) | 56M 96F |

Stage IIIB Stage IV, Postoperative recurrence |

Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Erlotinib |

| National Cancer Institute. (2019) | NCT00126581 | United States | A Phase II Randomized, Open label Study | 2 | 181 | 59 (32–81 years old) | 74M 107F |

Stage III, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Carboplatin, Erlotinib, Paclitaxel |

| Stathopoulos et al. (2004) | N/A | Greece | Multicenter, randomized, phase III trial | 2 | 360 | 65 (30–84 years old) | 312M 48F |

Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Vinorelbine |

| Valdivieso et al. (1984) | N/A | United States | Prospective, randomised study | 2 | 100 | 56.5 (33–78 years old) | 79M 21F |

N/A | Biopsy | Weekly VS. once every 3 weeks doxorubicin | Cisplatin, Cyclo-phosphamide, Doxorubicin, Ftorafur |

| Baggstrom et al. (2017a) | NCT00693992 | United States | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial | 2 | 210 | 64.9 (25–89 years old) | 117M 93F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Chemotherapy, Sunitinib |

| Paz-Ares et al. (2015) | NCT00863746 | Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Netherlands, Pakistan, Peru, Phillippines, Poland, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, United Kingdom, United States | Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 2 | 703 | ≥18 years old | 395M 308F |

N/A | Smoker Status | N/A | Best supportive care, Sorafenib |

| Novello et al. (2014b) | NCT00460317 | 32 countries including Italy, Germany, Romania, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States | Phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled, doubleblind study | 2 | 360 | 60.8 (31–81 years old) | 295M 65F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Motesanib |

| Akamatsu et al. (2018) | NCT02151981 | Australia, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Hungary Italy, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, Russia, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, United Kingdom, United States | Randomized, open-label, phase III clinical trial | 2 | 419 | 62.5 (20–90 years old) | 150M 269F |

N/A | Smoker Status | N/A | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Pemetrexed, Osimertinib |

| Kosmidis et al. (2008) | N/A | Greece | Phase III Study | 2 | 452 | 63 (36–83 years old) | 378M 74F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Gemcitabine |

| Reinmuth et al. (2019) | NCT02364999 | Australia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Chile, Croatia, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, India, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Netherlands, Philippines, Poland, Romania, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, United States | Multinational, double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study | 2 | 719 | 61.5 (25–87 years old) | 467M 252F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV, Recurrent | Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, PF-06439535 |

| Blumenschein et al. (2010) | NCT00094835 | United States | Multicenter, Open-label, Dose-finding, Phase IB study of motesanib | 3 | 45 | 61.3 (32–79 years old) | 29M 16F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

Smoker Status | N/A | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Panitumumab, Motesanib |

| Choy et al. (2013) | NCT00482014 | India, United States | Open-label, Randomised Trial | 2 | 98 | 63.6 (43.7–85.2 years old) | 61M 37F |

Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB |

N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Cisplatin Pemetrexed |

| William et al. (2007) | N/A | United States | Open-label, Phase I, Dose-escalationStudy | 4 | 21 | 52 (38–71 years old) | 13M 8F |

Stage IV | N/A | Dose | Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Motexafin gadolinium |

| Chang et al. (1993) | N/A | United States | Phase II Study | 3 | 103 | 61.3 (31–85 years old) | 70M 33F |

Stage IV | N/A | N/A | Merbarone, Piroxantrone, Taxol |

| Kubota et al. (2017) | JapicCTI-121887 (Japan Primary Registries Network) | Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan | Phase III, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-blind Study | 2 | 401 | 65 (Upper Quartile: 58; Lower Quartile: 70) | 288M 113F |

Stage IV, Recurrent | Smoker Status | N/A | Carboplatin, Motesanib, Paclitaxel |

| Zinner et al. (2015) | NCT00948675 | United States | Multicenter, Randomized, Open-label, US-only Phase III Trial | 2 | 361 | 65.6 (38.4–86.2 years old) | 209M 152F |

Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel Pemetrexed |

| Heigener et al. (2013) | NCT00160069 | Germany | Prospective, Multicenter, Phase II study | 3 | 128 | 63 | 83M 45F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | Dose, Duration of Infusion | Sagopilone |

| Jie Wang et al. (2018) | N/A | China | Randomised Controlled Trial | 2 | 128 | No mean/median (36–76 years old) | 96M 32F |

N/A | N/A | N/A | Cisplatin, Endostar, Pemetrexed |

| Eli Lilly and Company (2019a) | NCT01469000 | China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan | Multicenter, Randomized, open-label, parallel-arm, phase II study | 2 | 191 | 61.71 (S.D.: 9.38) | 68M 123F |

Stage IV | N/A | N/A | Gefitinib, Pemetrexed |

| Douillard (2004) | N/A | Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, United States | Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled, Phase II Feasibility Study | 2 | 75 | 61.4 | 56M 19F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | N/A | BMS-275291, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel |

| Butts et al. (2007) | N/A | Canada, United States | Multicenter, Open-label, Randomized Phase II study | 2 | 131 | 66 (35–84 years old) | 58M 73F |

Stage IIIB Stage IV, Recurrent |

N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Cetuximab, Gemcitabine |

| Fukuda et al. (2019) | UMIN000008771 (University Hospital Medical Information Network) | Japan | Randomised Phase II Study | 2 | 40 | 78 (75–83 years old) | 23M 17F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV, Postoperative recurrence |

Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Pemetrexed |

| Passardi et al. (2008) | N/A | Italy | Randomized Phase II Trial | 2 | 81 | 63 (35–77 years old) | 65M 16F |

Stage IV | N/A | N/A | Docetaxel, Gemcitabine |

| Gatzemeier et al. (2004) | N/A | Canada, Italy, Germany, Netherlands, United Kingdom | Randomized, Open-label, Phase II study | 2 | 101 | 58.5 (35–76 years old) | 63M 38F |

Stage IB, Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

N/A | N/A | Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, Trastuzumab |

| Park et al. (2017) | NCT01282151 | South Korea | Open-label, Multicenter Prospective Phase III Study | 2 | 148 | 63.3 | 103M 45F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Pemetrexed |

| Movsas et al. (2005) | N/A | Canada, United States | Randomised Trial | 2 | 242 | ≥18 years old | 150M 92F |

Stage IIA, Stage IIB, Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB | N/A | N/A | Amifostine, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel |

| Jänne et al. (2014) | N/A | Canada, Germany, Spain, United States | Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase II Trial | 3 | 200 | 61.4 (27.8–87.8 years old) | 127M 68F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | Smoker Status | Dose | Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, LY293111 |

| Groen et al. (2011) | N/A | Netherlands | Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Study | 2 | 561 | 61 (33–84 years old) | 355M 206F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Celecoxib, Docetaxel |

| Currow et al. (2017) | NCT01395914 | Australia, Belarus, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Ukraine | Double-blind, safety extension Phase III Study | 2 | 513 | 62.0 | 387M 126F |

Stage IIIA, Stage IIIB, Stage IV |

N/A | N/A | Anamorelin, Placebo |

| Langer et al. (2017) | NCT00789373 | Australia, Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, India, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Turkey, United Kingdom | Phase 3, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study | 2 | 939 | 61.3 (24.4–83.0 years old) | 577M 362F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Cisplatin, Pemetrexed, Placebo |

| Kotsakis et al. (2015) | NCT00620971 | Greece | A Multicenter, Randomized, Phase II study | 2 | 77 | 59 (36–77 years old) | 57M 20F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Gemcitabine, Vinorelbine |

| Eli Lilly and Company (2015) | NCT00112294 | United States | A Phase III, Randomised, Open Label Study | 2 | 676 | 64 (S.D.: 10.2) | 396M 280F |

N/A | N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Cetuximab, Taxane (Paclitaxel/Docetaxel) |

| GlaxoSmithKline (2019) | NCT01868022 | Belgium, Denmark, Netherlands, Russia, Spain, United Kingdom, United States | Multi-arm, Non-randomized, Open-Label Phase IB Study | 9 | 65 | 66.52 (S.D.: 3.08) | 52M 13F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | Dose | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Docetaxel, GSK3052230, Paclitaxel, Pemetrexed |

| Lara et al. (2016) | N/A | United States | Randomised, Phase II Selection Design Trial | 2 | 59 | 73.1 (40.9–85.9 years old) | 24M 35F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Carboplatin, Erlotinib, Paclitaxel |

| Wu et al. (2020) | NCT01982955 | China, Italy, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea Spain, Taiwan | Open-label, randomized, Phase 1b/2 study | 5 | 88 | N/A | 36M 52F |

Advanced | N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Gefitinib, Pemetrexed, Tepotinib, |

| Umsawasdi et al. (1989) | N/A | N/A | Randomised Study | 2 | 102 | 56.5 (33–78 years old) | 71M 31F |

Stage III | N/A | N/A | Cisplatin, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin |

| Cortot et al. (2020) | NCT01763671 | France | Double-arm, Randomised, Open-label, Multicentre, Phase III Clinical Trial | 2 | 166 | 59.7 (18.6–81.8 years old) | 120M 46F |

Stage III, Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Bevacizumab, Docetaxel, Paclitaxel |

| AstraZeneca (2021) | NCT01933932 | Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, France, Germany, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russian Federation, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, United States | A Phase III, Double-Blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Study | 2 | 510 | 61.4 (S.D.: 8.3) | 303M 207F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | N/A | Docetaxel, Selumetinib |

| Johnson et al. (2004) | N/A | United States | Randomized Phase II Study | 3 | 99 | ≥18 years old | 60M 39F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | N/A | Dose | Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel |

| Eli Lilly and Company (2022) | NCT00981058 | Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Croatia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, South Korea, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, South Africa, Spain, Taiwan, Thailand, United Kingdom, United States | Multinational, Randomized, Multicenter, Open-label, Phase III Study | 2 | 1093 | 62 (32–86 years old) | 908M 185F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, Necitumumab |

| Eli Lilly and Company (2021) | NCT00982111 | Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Croatia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, South Africa, Spain, United Kingdom, United States | Multinational, Randomized, Multicenter, Open-label Phase III Study | 2 | 633 | 61 (26–88 years old) | 424M 209F |

Stage IIIB, Stage IV | Smoker Status | N/A | Cisplatin, Pemetrexed, Necitumumab |

| Eli Lilly and Company (2019b) | NCT01769391 | Germany, South Korea, Mexico, Poland, Russia, United States | Randomized, Multicenter, Open-Label, Phase II Study | 2 | 167 | 65.3 | 131M 36F |

Stage IV | N/A | N/A | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Necitumumab |

TABLE 2.

Types of cardiotoxicity and their corresponding number of frequencies reported per publication.

| References (publication year) | Drug combination | Dose escalation study | Arrhythmia | Cardiac arrest | Cardiac failure | Cardiotoxicity (Grade 1–4) | Hypertension | Hypotension | Ischaemia | Myocardial infarction | Palpitations | Pericardial effusion | Thromboembolic event (both arterial/venous) | Other cardiovascular event | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmia (general) | Atrial/Supra-ventricular arrhythmia | Ventricular arrhythmia | |||||||||||||||||

| Atrial fibrillation | Atrial flutter | Bradycardia | Tachycardia | QT prolongation | |||||||||||||||

| Mizugaki et al. (2015) | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Veliparib | V-40 mg | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| V-80 mg | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| V-120 mg | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Huang et al. (2020) | Apatinib, Carboplatin, Pemetrexed | A-750 mg | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| A-500 mg | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| A-500 mg 2/1 (500 mg/day 2 weeks on 1 week off) | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sebastian et al. (2019) | CV9201 | CI - 400 μg | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| CII - 800 μg | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| CIII - 1600 μg | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Phase IIA - 1600 μg | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Novello et al. (2014a) | Cisplatin, Iniparib, Gemcitabine | GC | 9 | ||||||||||||||||

| GCI | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cappuzzo et al. (2006) | Chemotherapy, Gemcitabine | Standard 50 mg/min | 16 | ||||||||||||||||

| Low 10 mg/min | 11 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Srinivasa et al. (2020) | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Etoposide, Paclitaxel | Cis-Etop | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Car-Pac | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Yoshioka et al. (2017) | Amrubicin, Docetaxel | Amrubicin | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | Ventricular extrasystole: 2 Cardiac tamponade: 1 |

||||||||||||

| Docetaxel | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Johnson et al. (2013) | Bevacizumab, Erlotinib (CT prior to trial) | Bev-Plac | 31 | 85 | |||||||||||||||

| Bev-Erlo | 29 | 88 | |||||||||||||||||

| Gridelli et al. (2001) | Gemcitabine, Vinorelbine | Gem | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Gem-Vin | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Martoni et al. (1991) | Epirubicin | 120Epi | LVEF value decrease | ||||||||||||||||

| 135Epi | |||||||||||||||||||

| 150Epi | |||||||||||||||||||

| 165Epi | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Sequist et al. (2013), Boehringer Ingelheim (2018a), Wu et al. (2018) | Afatinib, Cisplatin, Pemetrexed | Afatinib | 0 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Mitral valve incompetence: 1 | ||||||||||

| Pemetrexed/Cisplatin Chemotherapy | 1 | 14 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Boehringer Ingelheim (2018b) | Afatinib, Cisplatin, Gemcitabine | Afatinib | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Cisplatin, Gemcitabine Chemotherapy | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Boehringer Ingelheim (2020) | Afatinib, Gefitinib | Afatinib | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | Acute coronary syndrome: 1 Angina pectoris: 1 Coronary heart disease: 1 |

||||||||||||

| Gefitinib | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | Coronary heart disease: 1 Coronary artery occlusion: 1 |

||||||||||||||

| Hida et al. (2017) | Alectinib, Crizotinib | Alectinib | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Crizotinib | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Berghmans et al. (2013) | Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Gemcitabine, Ifosfamide | IG | 10 | ||||||||||||||||

| GIP | 8 | ||||||||||||||||||

| DP | 20 | ||||||||||||||||||

| EU Clinical Trials Register, (2011); GlaxoSmithKline, (2014) | Docetaxel, GSK1120212 (Trametinib) | Doc | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Tra | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Martoni et al. (1999) | Epirubicin, Cisplatinum, Vinorelbine | HDEpi-Cis | 3 | >15% LVEF decrease: 9 | |||||||||||||||

| Vin-Cis | 0 | >15% LVEF decrease: 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Reck et al. (2015) | Docetaxel, Nintedanib | Doc-Nin | 23 | 22 | |||||||||||||||

| Doc-Plac | 6 | 19 | |||||||||||||||||

| Saito et al. (2003) | Carboplatin, Docetaxel, Paclitaxel | Car-Doc | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Car-Pac | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Barlesi et al. (2018) | Avelumab, Docetaxel | Avelumab | 1 | Person with acute cardiac failure also suffered from autoimmune myocarditis | |||||||||||||||

| Docetaxel | 0 | Cardiovascular insufficiency: 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Camidge et al. (2018) | Brigatinib, Crizotinib | Brigatinib, | 7 | 31 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| Crizotinib | 17 | 10 | 8 | ||||||||||||||||

| Wachters et al. (2003) | Cisplatin, Epirubicin, Gemcitabine | Gem-Cis | 7 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Gem-Epi | 21 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Shaw et al. (2013) | Crizotinib, Docetaxel, Pemetrexed | Criz | 1 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Cardiac tamponade: 1 Coronary artery disease: 1 Syncope: 1 |

||||||||||

| Doc-Pem | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | Cardiac tamponade: 1 | ||||||||||||

| Solomon et al. (2014) | Crizotinib, Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Pemetrexed | Criz | 1 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Atrioventricular block: 1 Cardiac tamponade: 2 |

|||||||||||

| Pem-Car/Cis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Pericarditis: 1 Syncope: 2 |

|||||||||||||

| Bonomi et al. (2000) | Cisplain, Etoposide, Paclitaxel | Cis-Etop | Fatal cardiac events: 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cis-250Pac | Fatal cardiac events: 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cis-135Pac | Fatal cardiac events: 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| *The six fatal Grade 5 cardiac events listed above were summarised overall instead of by treatment group - sudden death in 3 patients, myocardial infarction in 2 patients, and hypotension with acute pericarditis in 1 patient | |||||||||||||||||||

| Zatloukal et al. (2004) | Cisplatin, Vinorelbine | Con | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Seq | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Zarogoulidis et al. (2013) | Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Docetaxel, Erlotinib | Car-Doc | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Car-Doc-Erlo | |||||||||||||||||||

| Bev-Car-Doc | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Bev-Car-Doc-Erlo | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Koch et al. (2011) | Celecoxib, Chemotherapy (carboplatin/cisplatin/gemcitabine/vinorelbine) | Celecoxib | 2 | 17 | Cerebrovascular ischaemia: 4 | ||||||||||||||

| Placebo | 1 | 12 | Cerebrovascular ischaemia: 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Bi et al. (2019) | Celecoxib, Cisplatin, Etoposide | CE | 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| CE-Cele | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Herbst et al. (2011) | Bevacizumab, Erlotinib | Erlo | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Erlo-Bev | 15 | 12 | |||||||||||||||||

| Seto et al. (2014), Kato et al. (2018) | Bevacizumab, Erlotinib | Erlo | 2 | 11 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Erlo-Bev | 1 | 58 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| National Cancer Institute, (2019) | Carboplatin, Erlotinib, Paclitaxel | Erlo | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||||||

| Erlo-Car-Pac | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 9 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 12 | ||||||||

| Stathopoulos et al. (2004) | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Vinorelbine | Pac-Car | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pac-Vin | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Valdivieso et al. (1984) | Cisplatin, Cyclo-phosphamide, Doxorubicin, Ftorafur | Weekly-Dox | |||||||||||||||||

| Standard-Dox | |||||||||||||||||||

| * By an objective grading system of myocardial damage by endomyocardial biopsy, it was suggested that the weekly administration of doxorubicin was associated with lower cardiac toxicity than that of the standard/tri-weekly administration of doxorubicin | |||||||||||||||||||

| Baggstrom et al. (2017a) | Chemotherapy, Sunitinib | CT-Placebo | 9 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| CT- Sunitinib | 27 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Paz-Ares et al. (2015) | Best supportive care, Sorafenib | BSC-Placebo | 16 | ||||||||||||||||

| BSC-Sorafenib | 68 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Novello et al. (2014b) | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Motesanib | Car-Pac-Placebo | 15 | 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Car-Pac-Mote | 47 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| Akamatsu et al. (2018) | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Pemetrexed, Osimertinib | Osim | 7 | 9 | |||||||||||||||

| Plat (car/cis)-Pem | 1 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Kosmidis et al. (2008) | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Gemcitabine | Gem-Pac | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Gem-Car | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Reinmuth et al. (2019) | Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, PF-06439535 | Car-Pac-Bev | 3 | 32 | 10 | Cardiac disorders: 12 | |||||||||||||

| Car-Pac-PF06439535 | 1 | 34 | 14 | Cardiac disorders: 10 | |||||||||||||||

| Blumenschein et al. (2010) | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Panitumumab, Motesanib | Mote(E)-CP | 1 | 0 | 10 | Conduction disorder: 1 | |||||||||||||

| Mote(E)-Pani | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||

| Mote(125)-CP-Pani | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Choy et al. (2013) | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Pemetrexed | Pem-Car | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Pem-Cis | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| William et al. (2007) | Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Motexafin gadolinium | MGd-2.5 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| MGd-5 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| MGd-10 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| MGd-15 | 2 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Chang et al. (1993) | Merbarone, Piroxantrone, Taxol | Merba | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Piro | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Taxol | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kubota et al. (2017) | Carboplatin, Motesanib, Paclitaxel | Car-Pac-Placebo | 29 | ||||||||||||||||

| Car-Pac-Mote | 86 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Zinner et al. (2015) | Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Pemetrexed | Car-Pem | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| Car-Bev-Pac | 4 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||

| Heigener et al. (2013) | Chemotherapy, Sagopilone | S-16,3 h | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| S-22, 0.5 h | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| S-22,3 h | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Jie Wang et al. (2018) | Cisplatin, Endostar, Pemetrexed | Cis-Pem | 40 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cis-Pem-Endostar | 54 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Eli Lilly and Company (2019a) | Gefitinib, Pemetrexed | Gef | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Angine pectoris: 0 | ||||||||||

| Gef-Pem | 1 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Angina pectoris: 1 | ||||||||||||

| Douillard (2004) | BMS-275291, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel | Car-Pac-Placebo | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |||||||||||||

| Car-Pac-BMS275291 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Butts et al. (2007) | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Cetuximab, Gemcitabine | Car-Cis-Gem | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Car-Cis-Gem-Cet | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Fukuda et al. (2019) | Bevacizumab, Pemetrexed | CT-Pem | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||

| CT-Pem-Bev | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||||||||

| Passardi et al. (2008) | Docetaxel, Gemcitabine | Gem3,8-Doc1 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| Gem1,8-Doc8 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gatzemeier et al. (2004) | Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, Trastuzumab | Cis-Gem | LVEF decrease >15%: 0 LVEF <30%: 0 |

||||||||||||||||

| Cis-Gem-Tras | LVEF decrease >15%: 8 LVEF <30%: 0 |

||||||||||||||||||

| Park et al. (2017) | Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Pemetrexed | Cis-Doc | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cis-Pem | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Movsas et al. (2005) | Amifostine, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel | Car-Pac | 11 | ||||||||||||||||

| Car-Pac-Ami | 30 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Jänne et al. (2014) | Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, LY293111 | Cis-Gem-Placebo | |||||||||||||||||

| Cis-Gem-200LY | Cardiorespiratory arrest: 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Cis-Gem-600LY | |||||||||||||||||||

| Groen et al. (2011) | Carboplatin, Celecoxib, Docetaxel | Car-Doc | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Pulmonary embolism: 2 | ||||||||||||

| Car-Doc-Celeco | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | Pulmonary embolism: 3 | ||||||||||||||

| Currow et al. (2017) | Anamorelin, Placebo | Anamorelin | 13 | Electrocardiogram:4 Ischemic Heart Disease: 4 |

|||||||||||||||

| Placebo | 4 | Electrocardiogram:7 Ischemic Heart Disease: 0 |

|||||||||||||||||

| Langer et al. (2017) | Cisplatin, Pemetrexed, Placebo | Induction: Cis-Pem | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Acute coronary syndrome: 1 Cardiac tamponade: 1 Cardio-respiratory arrest: 3 Diastolic dysfunction: 1 Pericarditis: 1 |

|||||

| Maintenance: Pem | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pericarditis: 2 Ventricular fibrillation: 1 |

|||||||

| Maintenance: Place | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||

| Kotsakis et al. (2015) | Bevacizumab, Cisplatin, Docetaxel, Gemcitabine, Vinorelbine | VCB - > DGB | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| DCB | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Eli Lilly and Company (2015) | Carboplatin, Cetuximab, Taxane (Paclitaxel/Docetaxel) | Tax-Car | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 20 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |||||||

| Tax-Car-Cel | 1 | 6 | 0 | 27 | 3 | 39 | 1 | 5 | 4 | 3 | Cardio-respiratory arrest: 2 | ||||||||

| GlaxoSmithKline (2019) | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Docetaxel, GSK3052230, Paclitaxel, Pemetrexed | 5GSK-Car-Pac | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| 10GSK-Car-Pac | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 20GSK-Car-Pac | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Cardiomegaly: 1 | |||||||||

| 5GSK-Doc | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Acute Coronary Syndrome: 1 Angina Pectoris: 1 |

|||||||||

| 10GSK-Doc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 20GSK-Doc | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 10GSK-Cis-Pem | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||

| 15GSK-Cis-Pem | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Conduction disorder: 1 | |||||||||

| 20GSK-Cis-Pem | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Conduction disorder: 1 Left ventricular hypertrophy: 1 Ventricular extrasystoles: 1 |

|||||||||

| Lara et al. (2016) | Carboplatin, Erlotinib, Paclitaxel | Erlo | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Erlo-Car-Pac | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Wu et al. (2020) | Carboplatin, Cisplatin, Gefitinib, Pemetrexed, Tepotinib, | 1b-300Tep-Gef | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||

| 1b-500Tep-Gef | 1 | 1 | 1 | Cardiac discomfort: 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 2Neg-Tep-Gef | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2Neg-Pem-Car/Cis | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2Pos-Tep-Gef | 0 | 0 | 0 | Supraventricular extrasystoles: 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Umsawasdi et al. (1989) | Cisplatin, Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin | Weekly-Dox | |||||||||||||||||

| Triweekly-Dox | |||||||||||||||||||

| * Endomyocardial biopsies were done when a total cumulative doxorubicin dose of 300 or 480 mg/m2 was reached. Results showed an increase in cardiotoxicity with an increase dosage of doxorubicin, and that the weekly administration of doxorubicin was less toxic than that of the standard/tri-weekly administration of doxorubicin | |||||||||||||||||||

| Cortot et al. (2020) | Bevacizumab, Docetaxel, Paclitaxel | Bev-Pac | 22 | Ischaemic stroke leading to death: 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Doc | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

| AstraZeneca (2021) | Docetaxel, Selumetinib | Doc-Plac | 4 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 5 | 4 | Cardiovascular insufficiency: 1 Cardiomegaly: 1 |

|||||||

| Doc-Selu | 5 | 2 | 6 | 8 (1 is congestive) | 4 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Bundle branch block left: 1 Coronary artery dissection: 1 Diastolic dysfunction: 1 Left Ventricular Dysfunction:1 Mitral valve imcopetence: 1 Pericarditis constrictive: 1 |

|||||||||

| Johnson et al. (2004) | Bevacizumab, Carboplatin, Paclitaxel | Car-Pac | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Car-Pac-7.5Bev | 5 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| Car-Pac-15Bev | 6 | 6 | |||||||||||||||||

| Eli Lilly and Company (2022) | Cisplatin, Gemcitabine, Necitumumab | Cis-Gem | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4* | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | Acute Coronary Syndrome: 1 Cardio-respiratory arrest: 1 Pericarditis: 1 * including 1 acute, 1 congestive |

||||||

| Cis-Gem-Nec | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1* | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 9 | Cardiac Tamponade: 1 Cardio-respiratory arrest: 3 Coronary artery disease: 1 * including 1 congestive |

||||||||

| Eli Lilly and Company (2021) | Cisplatin, Pemetrexed, Necitumumab | Cis-Pem | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 30 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Angina pectoris: 1 Cardiomyopathy: 1 |

|||||||

| Cis-Pem-Nec | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 17 | 2 | 3 | 6 | Cardiac tamponade: 2 Cardio-respiratory arrest: 1 Cardiopulmonary failure: 1 |

|||||||||

| Eli Lilly and Company (2019b) | Carboplatin, Paclitaxel, Necitumumab | Car-Pac | 4 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Car-Pac-Nec | 4 | 1 | 1* | 13 | 2 | 1 | * including 1 congestive | ||||||||||||

Remarks: All cardiovascular events with ≤3 studies reported are include in “others”.

Of the 74 eligible studies, 67 reported treatment emergent cardiovascular events, i.e., arrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, bradycardia, cardiac arrest, cardiac failure, coronary artery disease, heart failure, hypertension, ischemia, left ventricular dysfunction, myocardial infarction, palpitations, and tachycardia.

Based on data extracted from the included studies, anticancer drugs for NSCLC that are associated with cardiovascular events include bevacizumab, carboplatin, cisplatin, crizotinib, docetaxel, erlotinib, gemcitabine and paclitaxel.

3.2 Dose-related cardiotoxicity

As shown in Table 2, twelve studies reported the use of different or escalating dosages of anticancer drugs.

According to the study by Mizugaki et al., cardiotoxicity, i.e., hypertension, was observed only in the 80 mg veliparib cohort, but neither the 40 mg nor the 120 mg cohort, so it cannot be concluded that veliparib is associated with dose-related cardiotoxicity (Mizugaki et al., 2015).

In the study by Huang M, 2020, patients received oral apatinib combined with intravenous pemetrexed and intravenous carboplatin for 4 cycles. Pemetrexed (500 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC = 5) were given on day 1 of 21-day cycle. The incidence of hypertension of the cohort which received 500 mg of apatinib per day for 2 weeks and then 1 week off (16.7%) was lower than the other two cohorts which received 500 mg (66.7%) and 700 mg (66.7%) of apatinib per day for 3 weeks respectively (Huang et al., 2020). In the study by Huang M, 2020, patients received oral apatinib combined with intravenous pemetrexed and intravenous carboplatin for 4 cycles. Pemetrexed (500 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC = 5) were given on day 1 of 21-day cycle. The incidence of hypertension of the cohort which received 500 mg of apatinib per day for 2 weeks and then 1 week off (16.7%) was significantly lower than the other two cohorts which received 500 mg (66.7%) and 700 mg (66.7%) of apatinib per day for 3 weeks respectively.

For CV9201, no dose-limiting toxicity was found across the three cohorts (400 μg, 800 μg, 1600 µg) during the Phase I trial, so 1600 µg was chosen to be used for the Phase II trial. With a larger sample size (n = 37), it was reported that one patient suffered from atrial tachycardia, however this adverse event was considered unrelated to the treatment by the clinicians of this trial (Sebastian et al., 2019).

Although reported incidence of cardiotoxicity in Arm A (standard infusion duration 50 mg/min) and Arm B (low infusion duration 10 mg/min) were 28.5% and 18.1% respectively in the study by Cappuzzo et al., it was believed that only one event of cardiac stroke in Arm B was associated with gemcitabine (Cappuzzo et al., 2006).

It was reported in Martoni et al. that 1 of the 3 patients in the cohort who initially received 165 mg/m2 dose and later continued the treatment at the reduced dose of 150 mg/m2, suffered from severe leukopenia, hypotension and fever after the third course. The patient later died 8 days after the epirubicin dose, which was believed to be caused by septic shock (Martoni et al., 1991). Besides, treatments were discontinued for 4 patients out of the total 24 patients as their left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) values dropped by 14%, 20%, 25% and 31% at the cumulative doses of 240 mg/m2 (120Epi), 560 mg/m2 (120Epi), 300 mg/m2 (150Epi) and 516 mg/m2 (150Epi) respectively. Despite the drop of LVEF values, no patients experienced any clinical signs of cardiotoxicity either at that time or subsequently. Also, no systematic pattern was observed in decrease of LVEF values across cohorts of different dosage and accumulated dosage, so it cannot be concluded that whether certain single and/or accumulated dosage of epirubicin had possibly caused a decrease in LVEF values (Martoni et al., 1991).

In Bonomi et al., fatal cardiac events were observed in 0.5% (Cis-Etop), 0.5% (Cis-Pac-250) and 2% (Cis-Pac-135) patients respectively. The frequency of cardiotoxicity was significantly higher when using higher dose (250 mg/m2) of paclitaxel (p = 0.026) whereas that of lower dose (135 mg/m2) of paclitaxel was insignificant (p = 0.143). Grade 5 cardiac events were also observed in 6 patients, including 3 sudden deaths, 2 myocardial infarction and 1 hypotension with acute pericarditis. However, this data needs to be considered carefully as four of the above-mentioned patients had a history of cardiovascular disease—two patients suffered from coronary artery disease, one patient had hypertension and the remaining was previously treated for cardiac arrhythmia (Bonomi et al., 2000).

A study published by Valdivieso et al., in 1984 demonstrated that the administration of weekly 20 mg/m2 of doxorubicin was associated with a lower incidence of cardiotoxicity than that of the standard regimen (every 3 weeks at 60 mg/m2 of doxorubicin) (Valdivieso et al., 1984). Cardiotoxicity was determined by an objective grading system of myocardial damage by endomyocardial biopsy. This study’s results aligned with previous studies which also suggested that the weekly treatment schedule was less cardiotoxic (Weiss et al., 1976; Weiss and Manthel, 1977). Due to the reduced risk of cardiotoxicity in weekly schedule of doxorubicin, it was suggested that the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin was associated with its peak plasma levels (Valdivieso et al., 1984).

Dose-limiting cardiotoxicities were observed in the 10 mg/kg (day 1 only) and 7.5 mg/kg (day 1 and/or day 2) motexafin gadolinium cohorts in William Jr. et al. Four patients suffered from hypertension and two patients suffered from myocardial ischemia within the first 24 hours administration of motexafin gadolinium (William et al., 2007). For the two patients who suffered from myocardial ischaemia—one experienced chest pain during the infusion of cycle 2 docetaxel, while the other patient experienced dyspnea 5 hours after completion of chemotherapy. Cardiac enzyme elevations were observed in both patients; T-wave inversion on the electrocardiogram and non-specific ST segment alterations in the electrocardiogram was observed in respective patient (William et al., 2007).

In Heigener DF et al., one patient, who was treated with 22 mg/m2 sagopilone at 0.5 hour infusion every 3 weeks, suffered from cardiac failure. However, it was considered that this was not a dose-limiting factor and also non-related to the drug as this was a single case and the cause of death for other cases were also miscellaneous events (Heigener et al., 2013).

In Jänne. et al., it was reported that there was a treatment-related death caused by cardiorespiratory arrest, which was treated with 200 mg LY293111 with gemcitabine and cisplatin. However, no treatment-related cardiotoxicity was reported in the 600 mg LY293111 cohort (Jänne et al., 2014).

In a non-randomised, 9-arm, open label Phase IB clinical trial which evaluated anticancer activity of GSK3052230, three different combinations of drugs were used—1) GSK3052230 with carboplatin and paclitaxel, 2) GSK3052230 with docetaxel and 3) GSK3052230 with cisplatin and pemetrexed. For each combination, there were three arms which consisted of different dosages of GSK3052230, i.e., 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg of GSK3052230 (GlaxoSmithKline, 2019). Counts of cardiotoxicity reported for each individual arm were shown in Table 2. As there was no systematic pattern of cardiotoxicity across arms, so it cannot be concluded that if there was dose-related cardiotoxicity associated with GSK3052230 (GlaxoSmithKline, 2019).

In a clinical trial conducted by Johnson. et al., carboplatin and paclitaxel were used as a control arm, and 2 arms consisted of different dosages of bevacizumab with carboplatin and paclitaxel were investigated. It was reported that higher dosage (15 mg/kg) of bevacizumab experienced a higher incidences of cardiotoxicity than that of 7.5 mg/kg of bevacizumab (Johnson et al., 2004).

3.3 Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias assessment is important as it can provide insight of possible bias for each study, thus aiding the transparency of results and findings in this systematic review. Table 3 includes a summary of the risk of bias assessment of each individual study. Light gray (+) indicates low risk; dark gray (−) indicates high risk and medium gray (?) means unclear as there is not enough information to make a clear judgement.

TABLE 3.

A summary of the risk of bias assessment of all eligible studies.

It was observed that for most publications, the risk of blinding of outcome assessment were unclear. Hence, there should be a more comprehend guideline for developing and reporting clinical trials, so to ensure clinical trials are conducted in a manner with as little bias as possible.

4 Discussion

Cardiotoxicity is a type of cardiovascular side effect caused by anticancer drugs used to treat NSCLC. This type of toxicity occurs when the anticancer drugs damage the heart or its surrounding structures, leading to a range of symptoms including arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, and high blood pressure. While the risk of cardiotoxicity is low in patients with early-stage NSCLC, it is higher in those with advanced or metastatic cancer. There are several factors that can increase the risk of cardiotoxicity in those receiving NSCLC treatments, such as age, pre-existing heart conditions, and the specific drug(s) used. Certain NSCLC drugs are more likely to cause cardiotoxicity than others, and certain combinations of drugs may also increase the risk. For example, traditional chemotherapy agents including gemcitabine, cisplatin, and carboplatin are all known to cause cardiotoxicity in some patients. With the rapid development of targeted therapies and immunotherapies, it was observed among the included eligible studies that a lot of treatments were still used in combination with conventional treatments, such as cisplatin, carboplatin, docetaxel and paclitaxel. Similar findings was reported by other literature, in which cytotoxic chemotherapies are still being used in ∼30% of cancer regiments (McGowan et al., 2017). Table 4 categorised all NSCLC drugs included in this systematic review by their therapeutic class, according to ATC/DDD Index 2022 (WHOCC, 2022).

TABLE 4.

Anticancer drugs included in this systematic review, categorised by therapeutic class.

| Chemotherapy | Targeted Therapy | Immunotherapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthracycline | Platinum Compound | Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) Inhibitor | Angiogenesis Inhibitor | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Inhibitor | Programmed cell death protein 1/death ligand 1 (PD-1/PDL-1) Inhibitor | Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Inhibitor |

| Amrubicin (L01DB10) | Carboplatin (L01XA02) | Alectinib (L01ED03) | Nintedanib (L01EX09) | Erlotinib (L01EB02) | Avelumab (L01FF04) | Cetuximab (L01FE01) |

| Epirubicin (L01DB03) | Cisplatin (L01XA01) | Brigatinib (L01ED04) | Sorafenib (L01EX02) | Gefitinib (L01EB01) | Necitumumab (L01FE03) | |

| Crizotinib (L01ED01) | Sunitinib (L01EX01) | Osimertinib (L01EB04) | Panitumumab (L01FE02) | |||

| Alkylating Agent | Anti-metabolite Agent | Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) Inhibitor | Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitors | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor | Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) Inhibitor | mRNA-based |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ifosfamide (L01AA06) | Gemcitabine (L01BC05 - Pyrimidine analogues) | Celecoxib (L01XX33) | Selumetinib (L01EE04) | Veliparib (L01XK05) | Trastuzumab (L01FD01) | CV9201 |

| Pemetrexed (L01BA04 – folic acid analogues) | GSK1120212/ Trametinib (L01EE01) |

| Plant Alkaloid | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGFR) Inhibitor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Docetaxel (L01CD02) | Bevacizumab (L01FG01) | |||||

| Etoposide (L01CB01) | ||||||

| Paclitaxel (L01CD01) | ||||||

| Vinorelbine (L01CA04) |

Hypertension was observed in over 30 studies, making it the most reported cardiotoxicity. Hypertension is mostly acute and self-limited and is known to be one of the common non-hematologic adverse events of antiangiogenic agents (Li et al., 2013). This systematic review also found that other drug classes such as anti-microtubule agents, alkylating agents were associated with treatment-induced hypertension which aligns with findings by Chung et al. (Chung et al., 2020). Hypertension was also observed with the combination use of cisplatin, docetaxel and motexafin gadolinium; they were normally observed within the first 24 hours administration of motexafin gadolinium, and subsided after receiving oral clonidine (William et al., 2007).

As most studies reported cardiotoxicity at aggregate level, it is unclear whether certain patient experienced more than one type of cardiotoxicity, therefore it cannot be determined to what extent hypertension could have potentially contributed to other cardiovascular diseases, such as ischaemia in individual patients. Hence, the lack of information available may result in overestimation of the association between NSCLC drugs and cardiotoxicity.

Anthracyclines are effective anticancer treatments, however, their benefits are often limited by possible fatal dose-dependent cardiotoxicity (Smith et al., 2010). Anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin, are believed to cause direct damage to the heart by inducing oxidative stress and direct damage to the cardiomyocytes (Zhang et al., 2012). According to an included study by Valdivieso et al., higher dose of doxorubicin leads to a higher incidence of cardiotoxicity (Valdivieso et al., 1984). This finding was supported by Swain et al., which suggested the incidence of heart failure after doxorubicin treatment increased with cumulative dose (Swain et al., 2003). An included study by Wachters et al., suggested that epirubicin caused a much higher incidence of cardiotoxicity than that of cisplatin (Wachters et al., 2004). In a study by Martoni et al., it was discovered that a higher dose of epirubicin was linked to a higher decrease in LVEF values, but no systematic pattern was observed in decrease of LVEF values across cohorts of different dosage and accumulated dosage, so it cannot be concluded that whether certain single and/or accumulated dosage of epirubicin possibly caused a decrease in LVEF values (Martoni et al., 1991). But this assumption can be supported by other studies, which concluded that epirubicin was associated with cumulative-dose cardiotoxicity (Wils et al., 1990; Feld et al., 1992; Smit et al., 1992). Others, such as daunorubicin, are believed to cause indirect damage to the heart by interfering with calcium homeostasis. One of the potential mechanisms of anthracycline cardiotoxicity is the inhibition of topoisomerase, which causes mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to the activation of cell death pathways and generation of reactive oxygen species (Carrasco et al., 2021). Additionally, different anthracyclines may have different levels of cardiotoxicity due to the presence of different metabolites or active forms of the drug, which could also contribute to the different onset of cardiotoxicity. For anti-microtubule agents, mechanisms of onset of cardiotoxicity include interfering with the normal function of the heart’s cells, such as the contractility of the cells and the electrical conduction pathways; blocking the formation of new microtubules, which is necessary for the heart’s cells to divide and multiply; and direct damage to the heart tissue, leading to arrhythmias, heart failure, and other cardiotoxic effects (Zhang et al., 2019).

Cisplatin is a type of alkylating agents and is also a commonly used drug to treat NSCLC (Table 4). As listed in Table 2, several studies demonstrated that cisplatin can cause cardiotoxicity, which ranged from arrhythmias, hypertension, myocardial infarction to chronic heart failure (Gatzemeier et al., 2004; Wachters et al., 2004; Butts et al., 2007; Berghmans et al., 2013; Choy et al., 2013; Novello et al., 2014a; Jänne et al., 2014, p. 4; Park et al., 2017; Jie Wang et al., 2018; Srinivasa et al., 2020; Eli Lilly and Company, 2022; 2021). The cisplatin-induced cardiotoxicities are possibly related to the imbalance of electrolytes (Miller et al., 2010; Oun and Rowan, 2017). Increased platelet reactivity by activation of arachidonic pathway is believed to be one of the mechanisms of cardiotoxicity caused by alkylating drugs. Oxidative stress and direct endothelial capillary damage with resultant extravasation of proteins, erythrocytes, and toxic metabolites, can then damage the myocardium, leading to cardiomyocyte degeneration and necrosis (Mudd et al., 2021).

For angiogenesis inhibitors that interfere with the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway, such as bevacizumab, can lead to hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure. Bevacizumab is a targeted therapy that starves tumours by preventing new blood vessels from growing. It was observed among a number of eligible studies that there were higher incidence rates of hypertension with the addition of bevacizumab in anticancer treatments than those without. Several studies showed that with the addition of bevacizumab, there was an increased incidence of arterial thromboembolic events. This result was expected as arterial thromboembolism is a known adverse reaction to bevacizumab (Herbst et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2013; Kato et al., 2018; Reinmuth et al., 2019). These adverse events were potentially caused by the VEGFR inhibition effects of bevacizumab, which negatively affected the coagulation system (Reck et al., 2015). Same as bevacizumab, sorafenib and sunitinib are also angiogenesis inhibitors, and more specifically VEGF receptor kinase inhibitor and multitargeted RTK inhibitors respectively. The mechanism of this class of drug is to inhibit neovascularization which will then inhibit the growth of tumour as new blood vessels are needed for tumours to grow. Sorafenib and sunitinib demonstrated similar cardiotoxicity potentials as only hypertension was observed in both of them (Paz-Ares et al., 2015; Baggstrom et al., 2017b). In contrast, inhibitors of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) pathway can lead to cardiomyopathy and increased risk of ischemic events due to increased myocardial oxygen consumption. Other angiogenesis inhibitors can cause cardiomyopathy due to their direct effect on the myocardium, leading to decreased contractility (Maurea et al., 2016; Dobbin et al., 2021).

In Gatzemeier et al., it was reported that cardiotoxicity was associated with the use of trastuzumab (Gatzemeier et al., 2004). This clinical finding differed from the safety profile of preclinical studies as there was no evidence of neither acute nor dose-related cardiotoxicity (Mellor et al., 2011). Inhibition of the NRG-1/ErbB2 signalling—a protective intracellular signalling pathway—is one of the proposed mechanisms that causes trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity (Perez and Rodeheffer, 2004). It was reported in Barlesi et al. that the patient in the avelumab group with acute cardiac failure also suffered from autoimmune myocarditis (Barlesi et al., 2018). In Butts et al., it was demonstrated that the addition of cetuximab to platinum/gemcitabine treatment did not increase cardiotoxicity as both groups reported the same percentage of cardiovascular events (Butts et al., 2007).

Through this systematic review, it is suggested that several NSCLC treatments are associated with cardiotoxicity, but the actual incidence of cardiotoxicity induced by NSCLC treatments is still undefined. This is because systematic cardiac monitoring was not carried out in most of the clinical trials, thus compromising the ability to detect cardiotoxicity during clinical trials. Moreover, all included clinical trials had different eligibility criteria, treatment regimens and reporting styles, therefore the lack of standardisation made it difficult to compare the safety data among different clinical trials.

In addition, most treatments reported were a combination of several anticancer drugs, hence it was difficult to identify exactly which drug contributes to cardiotoxicity or if a single drug has higher cardiotoxic potential.

This systematic review analysed data collected from clinical trials (i.e., aggregate data instead of individual patients’ data), hence it was difficult to tell whether one person suffered from more than one type of cardiotoxicities. Also, based on the eligibility criteria, some of the studies which did not match the required study design (i.e., single arm study) were excluded even though counts of cardiotoxicity were recorded, so this might have caused selection bias of studies. In addition, the authors of some included publications mentioned that the incidences of cardiotoxicity were believed to be unrelated to the anticancer treatments. Therefore, for this systematic review, we adopted their opinions and did not include those cardiotoxicities thought not to be associated with NSCLC treatments. Moreover, due to the limitations of the eligibility criteria, the drugs included in the eligible studies might not necessarily be the most commonly used first/second-line treatments of NSCLC. Another limitation was that differences in duration of follow-up period among studies may potentially result in inaccurate representation of the frequency of cardiotoxicity associated with corresponding anticancer drug. In some studies, only adverse events with an overall incidence of ≥10% were reported, thus might cause reporting bias. One of the limitations observed was that most cardiotoxicities reported were symptomatic cardiotoxicities, whereas some expected asymptomatic cardiotoxicities such as QT prolongation were not commonly reported, thus it is suggested that systematic cardiac monitoring should be carried out and corresponding data should be reported. Lastly, by restricting our literature search only to studies reported in English other relevant studies might have been missed.

5 Conclusion

In the last few decades, there has been a rapid development in cancer therapies and improved detection strategies, hence the death rates caused by cancer have decreased. However, it has been reported that cardiovascular disease has become the second leading cause of long-term morbidity and fatality among cancer survivors. The findings of this systematic review have provided a better understanding of the types of cardiotoxicities each anticancer drug is associated with. However, as systematic cardiac monitoring was not carried out in most of the clinical trials, the actual incidence of cardiotoxicity induced by NSCLC treatments remains undefined. Cardiotoxicity reported ranges from hypertension to heart failure with hypertension being the most common contributor. Although some cardiac adverse events are reversible, further research on identifying patients at risk for potentially serious cardiovascular events as well as implementation of early detection and screening strategies are needed to improve benefit-risk balance of treatments in cancer patients.

Funding Statement

This study is part of a programme funded by the Jenny Greenhorn Research Scholarship.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualisation of the systematic review, development of the selection criteria, the risk of bias assessment and data extraction criteria. The draft of the manuscript was written by SHYC and all authors reviewed this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

DL was employed by the company IQVIA UK and PEPI Consultancy Limited.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1137983/full#supplementary-material

Summary of treatment details and patients’ characteristics of each publication.

References

- Akamatsu H., Katakami N., Okamoto I., Kato T., Kim Y. H., Imamura F., et al. (2018). Osimertinib in Japanese patients with EGFR T790M mutation-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: AURA3 trial. Cancer Sci. 109, 1930–1938. 10.1111/cas.13623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameri P., Tini G., Spallarossa P., Mercurio V., Tocchetti C. G., Porto I. (2021). Cardiovascular safety of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor nintedanib. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 87, 3690–3698. 10.1111/bcp.14793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AstraZeneca (2021). “A phase III, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of selumetinib (AZD6244; ARRY-142886) (Hyd-Sulfate) in combination with docetaxel,” in Patients receiving second line treatment for KRAS mutation-positive locally advanced or metastatic non small cell lung cancer (stage IIIB - IV) (SELECT 1) (clinical trial registration No. NCT01933932) (clinicaltrials.gov; ). [Google Scholar]

- Baggstrom M. Q., Socinski M. A., Wang X. F., Gu L., Stinchcombe T. E., Edelman M. J., et al. (2017a). Maintenance sunitinib following initial platinum-based combination chemotherapy in advanced-stage IIIB/IV non–small cell lung cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study—CALGB 30607 (alliance). J. Thorac. Oncol. 12, 843–849. 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]