ABSTRACT

Parents’ stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine, such as beliefs that it promotes adolescent sexual activity, constitute a notable barrier to vaccine uptake. The purpose of this study is to describe the associations between parents’ stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine, psychosocial antecedents to vaccination, and parents’ intentions to vaccinate their children. Parents of vaccine-eligible children (n = 512) were surveyed in a large urban clinical network. Results indicate that two stigmatizing beliefs were significantly associated with self-efficacy in talking with a doctor about the HPV vaccine. Believing that the vaccine would make a child more likely to have sex was associated with citing social media as a source of information about the vaccine. Other stigmatizing beliefs were either associated with citing healthcare professionals as sources of information about the vaccine, or they were not significantly associated with any information source. This finding suggests that stigmatizing beliefs might discourage parents from seeking out information about the vaccine. This study is significant because it further highlights the importance of doctor recommendations to all patients at recommended ages; doctor visits may represent one of the few opportunities to normalize HPV vaccination and address parents’ stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine.

KEYWORDS: HPV vaccine, stigma, information-seeking, vaccine hesitance

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States1 and is a known cause of several cancers, including cervical, vaginal, vulvar, penile, and anal cancers.2 Vaccination against HPV is safe and highly effective, and current guidelines recommend that children be vaccinated at age 11 or 12.3 However, only 59% of teens in the US are up-to-date on HPV vaccination.4 Parents may face several barriers when deciding whether or not to vaccinate their children against HPV, including financial concerns, vaccine safety concerns, and low perceived risk of HPV infection.5 Stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine also remain a common barrier that effects parents’ decision-making.6–10

Stigma can be defined as “a social process or related personal experience characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame, or devaluation that results from experience or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgment about a person or group identified with a particular health problem.”11(p536) Stigmas surrounding sexually transmitted infections shame or blame individuals for becoming infected and associate them with sexual promiscuity.12 Often, these stigmas extend to screenings and preventative health technologies for sexually transmitted infections, such as the HPV vaccine, creating a deterrent for people who fear being perceived as promiscuous.13,14

Stigmas that associate the HPV vaccine with sexual activity and promiscuity are prevalent among parents of vaccine-eligible children and are associated with lower intentions to vaccinate one’s child.6,8,15,16 For example, some parents fear that receiving the HPV vaccine will make their children think it is okay to become sexually active or that choosing to vaccinate their child implicitly condones sexual activity.6,8,9,16,17 Parental beliefs that the HPV vaccine is inappropriate for sexually inactive children, who are “too young” for a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection,18 are also rooted in stigma that associates the HPV vaccine with sexual activity or promiscuity. These stigmatizing beliefs are stronger in cultural contexts that value a “feminine honor” based on sexual purity6,7 and have been documented in a variety of samples, ranging from predominately white mothers6 and US college women7 to parents in India19 and Malaysia.20

Although the prevalence and effects of parents’ stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine have been reported, less is known about how these beliefs interact with other antecedents of vaccination, such as awareness raising through information-gathering from in-person communication (e.g. health care provider, social network) or online information seeking (e.g. social media, websites). The model of stigma management communication21 (SMC Model) provides insights regarding how parents’ stigmatizing beliefs may impact antecedents of vaccination, especially information-seeking. The SMC Model predicts that people who accept that a public stigma perception exists, but do not accept that the stigma applies to themselves, will engage in avoidance behaviors to distance themselves from the stigma.21 One avoidance behavior identified in the model involves avoiding stigmatizing situations.21 Applied to HPV vaccination, the SMC Model predicts that parents who perceive an association between the HPV vaccine and sex-related stigma will avoid conversations about the HPV vaccine with their child’s health care provider. It is possible that feelings of discomfort, stemming from perceived stigma, may decrease parents’ confidence in their ability to discuss the vaccine with their child’s health care provider and contribute to conversation avoidance. In other words, one explanation for parents’ conversation avoidance might involve low self-efficacy to communicate with their child’s health care provider about the HPV vaccine.

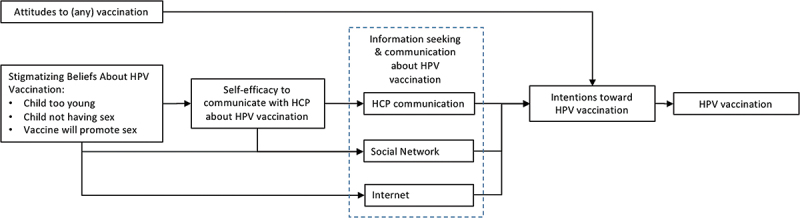

To avoid such conversations, parents with stigmatizing beliefs may instead turn to alternative means of seeking health information, such as friends, family members, or the internet. Existing research documents the prevalence and use of online sources of health information about potentially stigmatizing health topics (e.g. prevention of human immunodeficiency virus, a sexually transmitted virus22,23 cancer,24 and mental health25). Parents who perceive stigma associated with the HPV vaccine may similarly seek out alternative information sources. Although parents also turn to the internet for information about other vaccines,26 research suggests that their likelihood for online information-seeking is significantly higher when it comes to the HPV vaccine.27 Information gathered via alternative channels, like the internet, may contain misinformation that further discourages vaccination.28 Additionally, because doctor recommendations have been identified as important facilitators of HPV vaccine uptake,15,29 preference for alternative sources of information – rather than health care providers – may contribute to missed opportunities for doctors to persuade parents to have their child vaccinated and subsequently lower vaccination intentions. These theorized relationships are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Concept diagram of the association between stigmatizing beliefs, information seeking and communication behavior, and HPV vaccination intentions.

A recent scoping review of stigma associated with HPV and HPV screening/vaccination highlighted the need for research that examines pathways through which stigma lowers uptake of HPV prevention technologies, such as vaccination.10 This study begins to address that gap by exploring the associations between stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine and variables that might underlie stigma’s negative impact on uptake – namely variables related to information-seeking and communicating about the vaccine. Learning more about these relationships will shed light on potential leverage points in parents’ information-seeking and communication processes where health promotion efforts could potentially mitigate the effects of stigmatizing beliefs on vaccine uptake. Specifically, we address the following research questions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Research questions.

Methods

Recruitment

This study uses cross-sectional data from the pretest of a parent study30 conducted within Texas Children’s Pediatrics, a network of 51 clinics in the greater Houston, TX area. Clinics are located in five counties and serve over 100,000 children and adolescents. Parents of 11–17 year old girls and boys were recruited to participate in the study through the following methods: invitations sent to eligible parents through the MyChart patient portal, flyers placed in clinic waiting rooms, in-person recruitment by study staff in waiting rooms, and posts on the network Facebook page. To participate in the study, parents were required to agree to participate in the parent study, involving pre- and post-surveys about adolescent vaccination; have one child between the ages of 11 and 17 who had never received an HPV vaccine and who did not have a contraindication for vaccination (e.g., severe allergies); and have access to a mobile device. Parents received a $50 gift card upon completion of pre- and posttest surveys. This project was approved by UTHealth Institutional Review Boards (CPHS number: HSC-SPH-15-0202). Data were collected between September 20, 2017 and September 30, 2018.

Measures

Demographics

Demographic measures included: parent gender and age, child gender and age, race/ethnicity, employment, education, and medical insurance. Parents with multiple children eligible for HPV vaccination were asked to answer questions about their youngest unvaccinated child.

Intention to vaccinate

To assess intention to vaccinate, participants were asked, “Which statement is closest to where you are now in your plans to get your child the HPV vaccine?” Answer choices included: “I have no intention of getting my child the HPV vaccine,” “I haven’t thought of getting my child the vaccine,” “I am considering getting my child the vaccine,” “I will probably get my child the vaccine,” and “I will definitely get my child the vaccine.” Responses were assigned values between 0 and 4, with 0 representing no intention and 4 representing “definitely will.”

Attitudes toward vaccines (other than stigma)

To measure parents’ attitudes toward vaccines in general, the following question was adapted from Leask et al.31 “Choose the description that best describes how you feel about vaccines in general.” Answers choices included: “I always vaccinate my children and am confident that vaccines are safe,” “I vaccinate my children, despite minor concerns about rare side effects,” “I usually vaccinate my children but have significant concerns about the risks of vaccination,” “I prefer to delay vaccinations or choose only some recommended vaccines of my children,” and “I choose not to vaccinate my children for personal or religious reasons.” Responses were assigned values between 0 and 4, with 0 representing choosing not to vaccinate and 4 representing “always vaccinate.”

Stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine

Five survey items assessed stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine (e.g. it causes sexual behavior) and parental cognitions that achieve stigma avoidance by distancing their child from sex-related stigma associated with the HPV vaccine (e.g. my child is too young or not sexually active). Each belief was analyzed separately. The first three items were designed by the study team and were included in a list of “reasons your child has not gotten the HPV vaccine:” “My child is too young,” “My child is not having sex,” and “It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex.” For each belief, parents who did not select the belief as a reason for not vaccinating their child were assigned a value of “0,” and parents who selected the belief as a reason for not vaccinating their child were assigned a value of “1.”

The remaining two survey items were measured on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The items were: “My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection like HPV,” and “If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex.” These items were adapted from a subscale of the Carolina HPV Immunization Attitudes and Beliefs Scale.18 Cronbach’s alpha was 0.69.

Information source

To assess sources of information-seeking, participants were asked: “Where do you get your information about the HPV vaccine (select all that apply).” Answer choices included: “Healthcare provider,” “friend,” “family member,” “television,” “advertisement from drug company,” “Internet,” “social media,” “Other media (newspaper, radio),” and “Don’t remember.”

Self-efficacy in communicating with a doctor

Self-efficacy in communicating with a doctor was evaluated using 4 items (e.g. “How confident are you in your ability to ask your child’s pediatrician questions about the HPV vaccine?”), measured on a four-point Likert scale. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79. Three of these measures were adapted from the Perceived Efficacy in Patient-Physician Interactions Questionnaire.32

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the sample. Correlations between general attitudes toward vaccination and stigmatizing beliefs were calculated using Pearson’s Correlation coefficient and point-biserial correlations for stigmatizing beliefs coded as binary variables.

To examine the association of stigmatizing beliefs with parent self-efficacy in communicating with a doctor, separate t-tests were calculated for the first three stigmatizing beliefs, in which one group included the mean self-efficacy scores for the participants who did not rank the belief as a barrier and the other group represented the mean self-efficacy scores for participants who did rank the belief as a barrier. The remaining two barriers were in a 4-point Likert scale. T-tests were calculated for each of these stigmatizing beliefs, in which one group included the mean self-efficacy scores for participants who responded “strongly agree” or “agree” to the stigmatizing belief, and the other group represented the mean self-efficacy scores for participants who responded “strongly disagree” or “disagree.”

To examine the association between stigmatizing beliefs and sources of information-seeking, separate Mantel-Haenszel tests were calculated for the odds ratio of selecting a specific source of HPV vaccine information given the selection of each barrier to vaccination, i.e., odds ratio < 1 = less likely to select that source.

To examine the association between self-efficacy in communicating with a doctor and sources of information seeking, separate t-tests were calculated for each information source, where one group included the mean self-efficacy scores for each participant who did not select that information source, and the other group included the mean self-efficacy scores for each participant who did select that information source.

To examine the association of stigmatizing beliefs with intentions to vaccinate, separate t-tests were calculated for the first three stigmatizing beliefs, in which one group included the mean intention ratings for parents who did not rank the stigmatizing belief as a barrier and the other group represented the mean intention ratings for the parents who did rank the belief as a barrier. The remaining two beliefs were measured in a 4-point Likert scale. ANOVAS were calculated for each of those stigmatizing beliefs. Participants were grouped according to their rating of the belief (i.e. strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree)

Results

Participants

In response to recruitment messages, 881 parents accessed the survey. Out of these parents, 732 agreed that they were eligible and completed the consent form. Next, 636 parents met the eligibility requirement of having at least one child, age 10–17, who had never received the HPV vaccine. Participants did not complete the full survey (n = 19) and duplicate or fraudulent responses (n = 105) were removed, resulting in a final sample of 512 eligible parents. Parents were mainly female, white, had a college degree, and were privately insured (Table 1). The average age of parents was 41 years. Most parents had positive attitudes toward vaccination in general, responding either definitely or probably plan have their child receive the HPV vaccine (Table 2). A notable portion of parents reported stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine, especially regarding the beliefs “My child is too young” and “My child is not having sex.” Pearson’s correlation coefficients between stigmatizing beliefs and attitudes toward vaccination ranged from −0.15 to 0.2 (Table 3).

Table 1.

Parents demographics (N = 512).

| Characteristics | Mean | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Parent age | 41 | 24–61 |

| Parent gender | N | % |

| Male | 29 | 5.7 |

| Female | 483 | 94.3 |

| Child gender | ||

| Male | 248 | 48.4 |

| Female | 264 | 51.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 278 | 54.3 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 75 | 14.7 |

| Hispanic | 109 | 21.3 |

| Asian | 36 | 7.0 |

| Native American | 2 | 0.4 |

| College degree or more | ||

| No | 202 | 39.5 |

| Yes | 310 | 60.6 |

| Health Insurance | ||

| Private | 380 | 74.2 |

| Public | 120 | 23.4 |

| None | 12 | 2.3 |

Table 2.

Parents attitudes and beliefs.

| Intent to vaccinate child against HPV | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Definitely will | 180 | 35.2 |

| Probably will | 97 | 19.0 |

| Considering | 112 | 21.9 |

| Haven’t thought of it | 41 | 8.0 |

| Do not intend | 82 | 16.0 |

| Attitude toward vaccines in general | ||

| Always vaccinate | 196 | 38.3 |

| Vaccinate despite minor concerns | 216 | 42.2 |

| Usually vaccinate | 70 | 13.7 |

| Prefer to delay vaccination | 26 | 5.1 |

| Choose not to vaccinate | 4 | 0.8 |

| Stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine | ||

| N=# participants selected this as a barrier | ||

| Child is too young | 162 | 31.6 |

| Child is not having sex | 109 | 21.3 |

| Child might think it’s okay to have sex | 16 | 3.1 |

| Stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine | ||

| 1=strongly disagree; 2=somewhat disagree; 3=somewhat agree; 4=strongly agree | Mean | SD |

| Child is too young to get a sexually transmitted infection like HPV | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| Child is likelier to have sex | 1.3 | 0.6 |

Table 3.

Correlation between attitude toward vaccines in general and stigmatizing beliefs.

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection | −0.0699 |

| My child is not having sex | 0.1303 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.2037 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection | −0.1529 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | −0.0483 |

Stigmatizing beliefs and self-efficacy

There were no statistically significant differences in mean self-efficacy scores between parents who did and did not endorse the following stigmatizing beliefs: “My child is too young,” “My child is not having sex,” “It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex,” and “If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex” (Table 4). However, parents who agreed or strongly agreed with the belief “My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection” were significantly more likely than parents who disagreed with the belief to report lower self-efficacy scores in speaking with their doctor.

Table 4.

Differences in self-efficacy to communicate with doctor about the HPV vaccine score, according to stigmatizing belief and source of information seeking.

| Difference in mean self-efficacy | Mean self-efficacy score (SD) agree | Mean self-efficacy score (SD) disagree |

t(DF) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmatizing belief | |||||

| My child is too young. | 0.04 | 3.53 (0.55) | 3.49 (0.54) | −0.79 (510) | .22 |

| My child is not having sex. | 0.02 | 3.52 (0.53) | 3.5 (0.55) | −0.3 (510) | .38 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex. | 0.1 | 3.41 (0.49) | 3.51 (0.55) | 0.73 (510) | .77 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 0.23 | 3.4 (0.55) | 3.6 (0.48) | 4.76 (510) | .00 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.14 | 3.4 (0.56) | 3.51 (0.55) | 1.4 (510) | .08 |

| Source of information seeking | |||||

| Healthcare provider | 0.2 | 3.5 (0.52) | 3.35 (0.62) | −3.47 (510) | .00 |

| Friend | 0.04 | 3.47 (0.51) | 3.51 (0.56) | 0.73 (510) | .77 |

| Family member | 0.09 | 3.58 (0.48) | 3.49 (0.56) | −1.36 (510) | .08 |

| TV | 0.01 | 3.5 (0.56) | 3.51 (0.54) | 0.15 (510) | .56 |

| Internet | 0.04 | 3.49 (0.53) | 3.53 (0.57) | 0.85 (510) | .8 |

| Other media (newspaper, radio) | 0.12 | 3.6 (0.52) | 3.48 (0.55) | −1.82 (510) | .03 |

| Ads from drug company | 0.01 | 3.5 (0.57) | 3.51 (0.54) | 0.13 (510) | .55 |

| Social media | 0.1 | 3.41 (0.56) | 3.52 (0.54) | 1.42 (510) | .92 |

Stigmatizing beliefs and information-seeking

Two stigmatizing beliefs were associated with specific sources of information seeking. Parents who reported the stigmatizing belief “My child is not having sex” had significantly higher odds than parents who did not report this belief of reporting healthcare providers as a source of information. Parents who reported the stigmatizing belief “It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex” had significantly higher odds of reporting social media as a source of information than parents who did not report this belief (Table 5). The associations between the other stigmatizing beliefs and sources of information seeking were not statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association of HPV vaccination-related information sources, and stigmatizing belief.

| 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmatizing belief | Univariable Odds of using information source | p | LL | UL |

| Healthcare provider | ||||

| My child is too young. | 1.58 | .06 | 0.97 | 1.56 |

| My child is not having sex. | 2.63 | .00 | 1.38 | 5.03 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex. | 1.97 | .67 | 0.04 | 8.83 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 0.85 | .09 | 0.70 | 1.03 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.8 | .17 | 0.55 | 1.11 |

| Friend | ||||

| My child is too young. | 0.99 | .98 | 0.63 | 1.56 |

| My child is not having sex. | 0.71 | .23 | 0.41 | 1,23 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex | 0.83 | .77 | 0.23 | 2.97 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 0.94 | .50 | 0.77 | 1.13 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.9 | .54 | 0.63 | 1.28 |

| Family member | ||||

| My child is too young. | 0.68 | .178 | 0.39 | 1.19 |

| My child is not having sex. | 1.08 | .80 | 0.6 | 1.94 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex. | 1.34 | .66 | 0.37 | 4.82 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 0.93 | .54 | 0.75 | 1.17 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.88 | .55 | 0.59 | 1.33 |

| TV | ||||

| My child is too young. | 0.92 | .71 | 0.6 | 1.41 |

| My child is not having sex. | 1.08 | .76 | 0.67 | 1.73 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex. | 1.71 | .305 | 0.61 | 4.8 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 1.08 | .39 | 0.9 | 1.3 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.83 | .27 | 0.6 | 1.15 |

| Internet | ||||

| My child is too young. | 0.83 | .32 | 0.57 | 1.2 |

| My child is not having sex. | 0.75 | .19 | 0.49 | 1.15 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex. | 1.37 | .55 | 0.49 | 3.84 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 0.97 | .67 | 0.82 | 1.13 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.92 | .57 | 0.69 | 1.23 |

| Other media (newspaper, radio) | ||||

| My child is too young. | 1.07 | .78 | 0.65 | 1.77 |

| My child is not having sex. | 0.99 | .98 | 0.56 | 1.75 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex. | 0.33 | .26 | 0.04 | 2.52 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 0.85 | .14 | 0.69 | 1.05 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.98 | .91 | 0.66 | 1.44 |

| Ads from drug company | ||||

| My child is too young. | 0.83 | .52 | 0.48 | 1.44 |

| My child is not having sex. | 0.68 | .25 | 0.35 | 1.32 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex. | 1.38 | .62 | 0.38 | 4.98 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 0.92 | .49 | 0.74 | 1.16 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 0.95 | .79 | 0.63 | 1.43 |

| Social media | ||||

| My child is too young. | 0.64 | .154 | 0.35 | 1.19 |

| My child is not having sex. | 0.85 | .643 | 0.44 | 1.67 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex. | 3.43 | .02 | 1.14 | 10.3 |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection. | 1.08 | .56 | 0.84 | 1.37 |

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | 1.05 | .813 | 0.68 | 1.64 |

Self-efficacy and information-seeking

Parents reporting higher scores on self-efficacy in communicating with a doctor about the HPV vaccine were significantly more likely to report seeking out information from healthcare providers and seeking out information from “Other media (newspaper, radio).” (Table 4).

Stigmatizing beliefs and intentions to vaccinate

The following stigmatizing beliefs were associated with statistically significant lower intentions to give their child the HPV vaccine (p < .001): “My child is not having sex” and “It might make my child think it’s okay to have sex.” The stigmatizing belief “My child is too young” was associated with significantly higher intentions to vaccinate (p < .001). For two stigmatizing beliefs, mean intention ratings were highest for parents who strongly disagreed with the belief (Table 6). ANOVAs for the category differences for the following two stigmatizing beliefs were statistically significant (p < .001): “My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection” and “If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex.”

Table 6.

Differences in intention to vaccinate against HPV, according to reported barriers. Intent to vaccinate: 0 = don’t intend, 1 = haven’t thought of it, 2 = considering, 3 = will probably get it, 4 = definitely will.

| Difference in mean intent | Mean of intention (SD) agree | t(DF) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmatizing belief | ||||

| My child is too young. | ||||

| Agree | 2.93 (1.16) | 4.80 | ||

| Disagree | 0.64 | 2.29 (1.51) | (510) | < .000 |

| My child is not having sex. | ||||

| Agree | 2.09 (1.46) | 3.30 | ||

| Disagree | 0.51 | 2.6(1.42) | (510) | .0010 |

| It might make my child think it’s okay to have | ||||

| sex. | ||||

| Agree | 1.25(1.34) | 3.54 | ||

| Disagree |

1.28 |

2.53(1.42) |

(510) |

.0004 |

| |

|

Mean of intention |

|

p |

| My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 3.11 (1.31) | |||

| Somewhat disagree | 2.48(1.29) | |||

| Somewhat agree | 2.13 (1.38) | |||

| Strongly agree | 1.77 (1.49) | < .000 | ||

| If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 2.68 (1.41) | |||

| Somewhat disagree | 1.97(1.38) | |||

| Somewhat agree | 1.68 (1.39) | |||

| Strongly agree | 1.00 (1) | < .000 |

Discussion and conclusion

Our findings underscore the importance of stigma associated with the HPV vaccine among parents. Four of the five stigmatizing beliefs measured were associated with lowered intentions to vaccinate; only “My child is too young” was associated with higher intentions to vaccinate. Furthermore, weak correlations between stigmatizing beliefs and attitudes about vaccines in general (Table 3) suggest little overlap between stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine and other vaccine attitudes. Although 80.5% of parents had positive attitudes toward vaccines in general, 31.6% of parents listed “My child is too young” as a reason for not yet vaccinating their child against HPV – even though their child was at least 11 years old, the recommended age for HPV vaccination. Similarly, 21.3% of parents listed “My child is not having sex” as a reason. These two survey items describe cognitions that helps parents distance their children and themselves from sex-related stigma associated with the HPV vaccine, a common response to stigma outlined in the stigma management communication model (SMC model).21 This finding underscores the need for future research to use theories of stigma, such as the SMC model, to guide conceptualization and measurement of stigma associated with the HPV vaccine. Studies that only measure stigma in terms of parents’ perception that the vaccine would promote adolescent sexual activity or make their child more likely to have sex report that 6% to 12% of parents in the US hold stigmatizing beliefs about the vaccine.15 These studies fail to capture the broader range of stigmatizing beliefs held by parents that act as a barrier to communicating with providers.

Our findings also provide insight into the role that stigma plays in parents’ information-seeking. Notably, parents holding the stigmatizing belief “My child is too young to get a vaccine for a sexually transmitted infection” had lower scores for self-efficacy in communicating with a doctor than other parents (Table 4). Parents who hold this stigmatizing belief may especially benefit from educational materials that they can consult independently from a doctor. Interventions that deliver educational materials to parents should be theoretically- and empirically-based, with methods designed to enhance parent communication self-efficacy and mitigate stigma-related barriers to vaccination. For example, the HPVcancerFree App was designed for parents of vaccine-eligible adolescents to raise awareness about HPV and reduce vaccine hesitancy by mitigating barriers to vaccination.33

Parents who held the stigmatizing belief “If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex” had higher odds of seeking out social media for information about the HPV vaccine. Currently, there is conflicting evidence about whether online information sources are harmful or helpful for parents. While some studies have documented detrimental effects of online misinformation about the HPV vaccine,28,34 another found that internet-based information-seeking is associated with more knowledge about HPV and greater intentions to vaccinate among parents.35 Our results add to this literature, suggesting that social media may serve as a place where uneasy parents feel more comfortable seeking information about the HPV vaccine, but it also may reinforce, rather than refute, stigmatizing beliefs. Furthermore, parents may turn to the internet as a way to avoid conversations about the HPV vaccine with their child’s health care providers, in turn reducing doctors’ opportunities to convince parents to vaccinate. Educational materials designed for parents who feel less confident talking with a doctor should address this stigmatizing belief (the vaccine makes children more likely to have sex) and may benefit from calling attention to the inaccuracy of some vaccine-related discourse on social media.

However, parents who endorsed the other stigmatizing beliefs did not seek out alternative information sources. In fact, endorsement of the belief “My child is not having sex” was associated with higher odds of reporting healthcare providers as sources of information seeking. Rather than driving parents to seek out alternative sources of information, these findings suggest that stigmatizing beliefs might instead shut down parents’ interest in information-seeking behaviors – perhaps because they feel uncomfortable thinking about the possibility of their child’s future sexual initiation and ensuing HPV risk, or perhaps because they feel resolute in their belief of their children’s low HPV risk and perceive no need to gather more information. If parents are actively avoiding engaging with the topic of HPV vaccination, patient-provider conversations might constitute one of the few opportunities to mitigate stigmatizing beliefs and thus decrease vaccine hesitancy. Future research should continue to investigate feasible methods for supporting providers in assessing and remediating stigma-associated beliefs of parents.

Our results partially support the relationships between stigma, antecedents to vaccination, and intentions to vaccinate suggested by the SMC model and outlined in Figure 1. One stigmatizing belief was associated with decreased self-efficacy in communicating with a doctor. A different stigmatizing belief was associated with information-seeking on the internet. However, other stigmatizing beliefs were not associated with information-seeking outside of the doctor’s office, suggesting the addition of an additional pathway – perhaps lower communication efficacy, resulting from stigma, is associated with lower intentions to engage in information-seeking. Future research should continue to study the complex relationships between stigma regarding the HPV vaccine and parents’ information-seeking processes. This study represents an important first step toward constructing a model to understand these relationships and pinpointing promising points of intervention.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several limitations. Data are cross-sectional and do not prove causation, nor do the analyses establish the temporal relationship between the factors examined. Out of our sample of 512 parents, only 29 participants were male. Our results may not be generalizable to male parents. However, research suggests that the gender distribution in this sample reflects national trends; national-level surveys find that between 80% and 90% of women are responsible for making healthcare decisions about family members.36,37 Over half the sample consisted of white parents in a large urban clinical network. Stigmatizing beliefs are rooted in social norms that may vary across time and across cultures. Cultural contexts that value “feminine honor” based on sexual purity report higher levels of stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine,6,7 and these beliefs may shape decision-making processes in unique ways. A strength of this study includes that 21% of study participants are Latino, representing a subgroup with a higher burden of cervical cancer.10 Still, our findings may not generalize to other populations or to rural settings. Larger surveys should continue to examine stigma, in more diverse populations, to inform future communication interventions aimed at decreasing stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine, in addition to correcting the beliefs once they are developed. Another limitation involves our measurement of information-seeking. Survey items captured broad categories of information sources (e.g. television, internet, social media) and do not provide detail about specific ads, websites, or social media platforms, nor the quality of the information encountered from these sources. Future research should further investigate the quality and content of specific sources of vaccine information, such as websites, widely-shared social media posts, etc. Finally, a recent study noted a dimension of HPV vaccine stigma that was not measured in the current study. In a sample of mothers in Hong Kong, some mothers reported concern that HPV vaccination may mark or single out their daughters as promiscuous and cause them to be stigmatized.38 Future research should continue to study the prevalence of this stigmatizing belief in other populations and explore how it interacts with other attitudes about the HPV vaccine.

Conclusion

In spite of these limitations, our findings illustrate how stigmatizing beliefs about the HPV vaccine are associated with parents’ communication and information-seeking processes. Parents who perceive their child is too young to get a sexually transmitted infection, and, therefore, too young for the HPV vaccine, are less likely to feel confident in their ability to communicate with a doctor. Although a few parents endorsed the stigmatizing belief “If my child gets the HPV vaccine, he/she may be more likely to have sex,” a larger portion of parents endorsed statements that reflect stigma avoidance via beliefs that distance their child from association with vaccine-related stigma. These beliefs were not associated with alternative sources of information-seeking, suggesting that parents who hold these stigmatizing beliefs wish to avoid engaging with the topic of their child’s future sexual initiation.

This study adds to the existing literature, highlighting the importance of doctors’ recommendations in favor of the HPV vaccine; not only are they effective,15,29 but also they may represent one of the few opportunities to engage parents in thinking about the HPV vaccine and to address parents’ stigmatizing beliefs about the vaccine.

Funding Statement

University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health Cancer Education and Career Development Program – National Cancer Institute/NIH Grant T32/CA057712 and Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT), Research Program, Grant RP150014.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Satterwhite CL, Torrone E, Meites E, Dunne EF, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MCB, Su J, Xu F, Weinstock H.. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2013;40(3):1–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318286bb53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, Markowitz LE, Thomas CC, DThompson T, Razzaghi H, Saraiya M.. Human papillomavirus–associated cancers — United States, 2008–2012. Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2016;65(26):661–6. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meites E, Kempe A, Markowitz LE. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination — updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. Morb Mort Wkly Rep. 2016;65(49):1405–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6549a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, Markowitz LE, Williams CL, Fredua B, McNamara LA, Stokley S, Singleton JA. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years — United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021 Sept 3;70(35):1183–90. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7035a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, Watson M, Liddon N, Stokley S. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among US adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Jan 1;168(1):76–82. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster S, Carvallo M, Lee J, Fisher R, Traxler H. An implication of impurity: the impact of feminine honor on human papillomavirus (HPV) screenings and the decision to authorize daughter’s HPV vaccinations. Stigma Health. 2021;6(2):216–27. doi: 10.1037/sah0000230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster S, Carvallo M, Song H, Lee J, Lee J. When culture and health collide: feminine honor endorsement and attitudes toward catch-up HPV vaccinations in college women. J Am Coll Health. 2021 Aug 16;0(0):1–9. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2021.1935970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedman AL, Shepeard H. Exploring the knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and communication preferences of the general public regarding HPV: findings from CDC focus group research and implications for practice. Health Educ Behav. 2007 June 1;34(3):471–85. doi: 10.1177/1090198106292022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lahijani AY, King AR, Gullatte MM, Hennink M, Bednarczyk RA. HPV vaccine promotion: the church as an agent of change. Social Sci Med. 2021 Jan 1;268:113375. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson CE, Silva A, Goben AH, Ongtengco NP, Hu EZ, Khanna D, Nussbaum ER, Jasenof IG, Kim SJ, Dykens JA. Stigma and cervical cancer prevention: a scoping review of the U.S. literature. Prev Med. 2021 Dec 1;153:106849. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J. Stigma interventions and research for international health. Lancet. 2006 Feb 11;367(9509):536–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hood JE, Friedman AL. Unveiling the hidden epidemic: a review of stigma associated with sexually transmissible infections. Sex Health. 2011 May 18;8(2):159–70. doi: 10.1071/SH10070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rees HD, Lombardo AR, Tangoren CG, Meyers SJ, Muppala VR, Niccolai LM. Knowledge and beliefs regarding cervical cancer screening and HPV vaccination among urban and rural women in León, Nicaragua. PeerJ. 2017 Oct 25;5:e3871. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomann M, Grosso A, Zapata R, Chiasson MA. ‘WTF is PrEP?’: attitudes towards pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York city. Cult Health Sex. 2018 July 3;20(7):772–86. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2017.1380230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brewer NT, Fazekas KI. Predictors of HPV vaccine acceptability: a theory-informed, systematic review. Prev Med. 2007 Aug 1;45(2):107–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olshen E, Woods ER, Austin SB, Luskin M, Bauchner H. Parental acceptance of the human papillomavirus vaccine. J Adolesc Health. 2005 Sept 1;37(3):248–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escoffery C, Riehman K, Watson L, Priess AS, Borne MF, Halpin SN, Rhiness C, Wiggins E, Kegler MC. Facilitators and barriers to the implementation of the HPV VACs (vaccinate adolescents against cancers) program: a consolidated framework for implementation research analysis. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019 July 3;16:180406. doi: 10.5888/pcd16.180406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McRee AL, Brewer NT, Reiter PL, Gottlieb SL, Smith JS. The Carolina HPV immunization attitudes and beliefs scale (CHIAS): scale development and associations with iintentions to vaccinate. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(4):234–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c37e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madhivanan P, Li T, Srinivas V, Marlow L, Mukherjee S, Krupp K. Human papillomavirus vaccine acceptability among parents of adolescent girls: obstacles and challenges in Mysore, India. Prev Med. 2014 July 1;64:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sam IC, Wong LP, Rampal S, Leong YH, Pang CF, Tai YT, Tee H-C, Kahar-Bador M. Maternal acceptance of human papillomavirus vaccine in Malaysia. J Adolesc Health. 2009 June 1;44(6):610–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meisenbach RJ. Stigma management communication: a theory and agenda for applied research on how individuals manage moments of stigmatized identity. J Appl Commun Res. 2010 Aug 1;38(3):268–92. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2010.490841. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannaford A, Lipshie-Williams M, Starrels JL, Arnsten JH, Rizzuto J, Cohen P, Jacobs D, Patel VV. The use of online posts to identify barriers to and facilitators of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among men who have sex with men: a comparison to a systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature. AIDS Behav. 2018 Apr 1;22(4):1080–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-2011-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hedrick AM, Carpentier FRD. How current and potential pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users experience, negotiate and manage stigma: disclosures and backstage processes in online discourse. Cult Health Sexuality. 2021 Aug 2;23(8):1079–93. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1752398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazard AJ, Collins MKR, Hedrick A, Varma T, Love B, Valle CG, Brooks E, Benedict C. Using social media for peer-to-peer cancer support: interviews with young adults with cancer. JMIR Cancer. 2021 Sept 2;7(3):e28234. doi: 10.2196/28234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright KB, Rains SA. Weak-tie support network preference, health-related stigma, and health outcomes in computer-mediated support groups. J Appl Commun Res. 2013 Aug 1;41(3):309–24. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2013.792435. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbieri CL, Couto MT. Decision-making on childhood vaccination by highly educated parents. Revista de Saúde Pública. 2015 Mar 31;49. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2015049005149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bragazzi NL, Barberis I, Rosselli R, Gianfredi V, Nucci D, Moretti M, Salvatori T, Martucci G, Martini M. How often people google for vaccination: qualitative and quantitative insights from a systematic search of the web-based activities using google trends. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2017 Feb 1;13(2):464–9. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1264742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luisi MLR. From bad to worse II: risk amplification of the HPV vaccine on Facebook. Vaccine. 2021 Jan 8;39(2):303–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gargano LM, Herbert NL, Painter2 JE, Sales JM, Morfaw3 C, Rask2 K, Murray D, DiClemente RJ, Hughes JM. Impact of a physician recommendation and parental immunization attitudes on receipt or intention to receive adolescent vaccines. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2013 Dec 24;9(12):2627–33. doi: 10.4161/hv.25823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vernon SW, Savas LS, Shegog R, Healy CM, Frost EL, Coan SP, Gabay, EK, Preston, SM, Crawford, CA, Spinner, SW, et al. Increasing HPV vaccination in a network of pediatric clinics using a multi-component approach. J Appl Res Child. 2019;10(2):11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leask J, Kinnersley P, Jackson C, Cheater F, Bedford H, Rowles G. Communicating with parents about vaccination: a framework for health professionals. BMC Pediatr. 2012 Sept 21;12(1):154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, DiMatteo MR, Reuben DB. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(7):889–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shegog R, Savas LS, Healy CM, Frost EL, Coan SP, Gabay EK, Preston SM, Spinner SW, Wilbur M, Becker E, et al. AVPCancerFree: impact of a digital behavior change intervention on parental HPV vaccine –related perceptions and behaviors. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2022 Nov 30;18(5):2087430. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2087430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dunn AG, Surian D, Leask J, Dey A, Mandl KD, Coiera E. Mapping information exposure on social media to explain differences in HPV vaccine coverage in the United States. Vaccine. 2017 May 25;35(23):3033–40. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McRee AL, Reiter PL, Brewer NT. Parents’ internet use for information about HPV vaccine. Vaccine. 2012 May 28;30(25):3757–62. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) . Fixing health care: what women want. Leawood (KS): AAFP; 2008. http://www.aafp.org/media-center/kits/women.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranji U, Salganicoff A.. Data note: balancing on shaky ground: women, work and family health [Internet]. KFF; 2014. [accessed 2023 Apr 5]. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/data-note-balancing-on-shaky-ground-women-work-and-family-health/. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loke AY, Chan ACO, Wong YT. Facilitators and barriers to the acceptance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination among adolescent girls: a comparison between mothers and their adolescent daughters in Hong Kong. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Aug 10;10(1):390. doi: 10.1186/s13104-017-2734-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]