ABSTRACT

YouTube is a highly popular social media platform capable of widespread information dissemination about COVID-19 vaccines. The aim of this mini scoping review was to summarize the content, quality, and methodology of studies that analyze YouTube videos related to COVID-19 vaccines. COVIDENCE was used to screen search results based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. PRISMA was used for data organization, and the final list of 9 articles used in the mini review were summarized and synthesized. YouTube videos included in each study, total number of cumulative views, results, and limitations were described. Overall, most of the videos were uploaded by television and internet news media and healthcare professionals. A variety of coding schemas were used in the studies. Videos with misleading, inaccurate, or anti-vaccination sentiment were more often uploaded by consumers. Officials seeking to encourage vaccination may utilize YouTube for widespread reach and to debunk misinformation and disinformation.

KEYWORDS: YouTube, COVID-19, vaccination, immunization, scoping review

Introduction

COVID-19 vaccination is a powerful countermeasure, touted as essential in mitigating the devastating effects of SARS-CoV-2.1 COVID-19 vaccine development and testing for efficacy were accelerated2 with emergency use authorization by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in December 2020.3 At the current time, there are four approved vaccines available in the US.4 Two are mRNA-based vaccines, one is a protein subunit vaccine, and the other is a viral vector vaccine.3 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) highly recommends staying current on vaccine uptake5 including receipt of boosters at pertinent times for appropriately aged individuals and those with comorbidities. COVID-19 vaccine uptake has been found to decrease the risk of contracting COVID-19, and in instances where vaccinated individuals do in fact get infected with the virus, it has been shown to significantly reduce severity of illness,6,7 risk of hospitalization,8–10 and mortality.5,11

There has been a steady increase in COVID-19 vaccination,12 improved confidence in vaccine efficacy, and concomitant benefits.13 However, vaccine hesitancy was prevalent during the height of the pandemic, throughout both the early stages of vaccination development and the eventual rollout, both worldwide14 and in the US specifically.15 In fact, in January 2021, nearly 62% of those who had not yet been vaccinated expressed a reluctance to receive the vaccine16

Multiple reasons have been posited for vaccine hesitancy, including the proliferation of misinformation, disinformation,17–21 as well as difficult-to-understand information about adverse events on the news,22,23 and on social media.24–26 Issues of mistrust27 and equitable access further exacerbated skepticism and reluctance.28

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic was met by fear, lack of preparedness, confusion, and uncertainty.29,30 This unprecedented experience contributed to the need to accelerate vaccine production, a process that many were unaccustomed to.3 This, coupled with an ‘infodemic’31–33 of information overload34,35 led consumers to seek information to make informed decisions for themselves and their loved ones.

YouTube is a highly popular source of information, which is widely accessible due to delivery via video content. More than 80% of Americans indicate that they use YouTube as a source of news, according to survey results.36 Current estimates suggest that YouTube is an important source of news for Americans.37 Given the free nature of the medium, there is a likelihood for individuals to upload content as well as for accessing information.

Seeking information via YouTube, eliminates literacy issues as a barrier, and consumers are drawn to hear about experiences from each other. Nonetheless, without rigorous oversight, there is the potential for variability in the comprehensiveness, usefulness, and quality of content. In fact, in May 2020, YouTube outlined a misinformation policy to combat the spread of information on COVID-19 vaccines that was counter to evidence-based, public health knowledge.38 Given the popularity of YouTube and the uptick in public health research based on the platform, the purpose of this mini scoping review is to describe the content, quality, and methodology of YouTube videos related to COVID-19 vaccines. The mini scoping review format was chosen as the aim is to summarize a specific subfield. The review methodology used the 5-step process recommended by Arksey and O’Malley39 that were: Stage 1: identifying the research question; Stage 2: identifying relevant studies; Stage 3: study selection; Stage 4: charting the data; Stage 5: collating, summarizing and reporting the results.

The research question studied was as follows: What is the content, quality, and methodology of studies analyzing YouTube videos related to COVID-19 vaccines? The review aims were:

to identify existing evaluations of YouTube videos with respect to COVID-19 vaccines

to synthesize the results of evaluation studies of YouTube videos on COVID-19 vaccines in terms of study design, upload source, view counts, coding methodology, definition of what constitutes misinformation.

Methods

Database search and screening

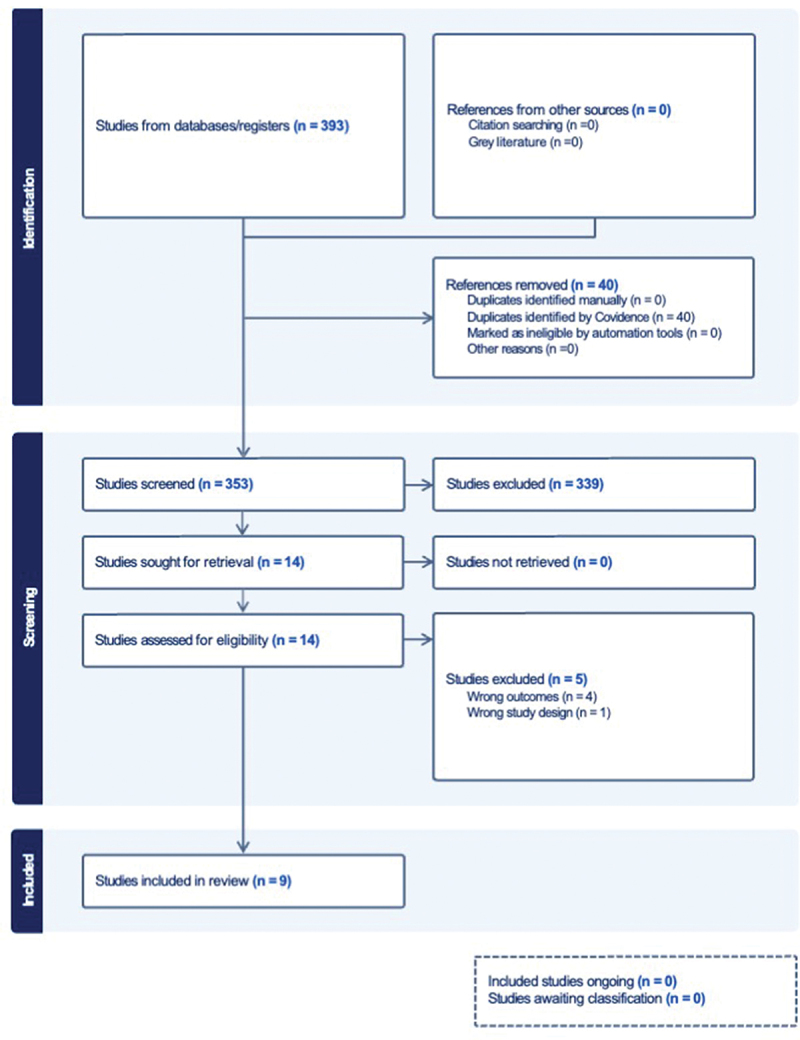

The first search for articles was conducted using the Columbia University Library system (CLIO), using the search terms “YouTube AND (vaccine OR Vaccination) AND COVID-19.” Search criteria excluded newspaper articles, including journal articles only, published in the English language between 1/1/2020 and 10/28/2022. The search returned 301 articles, which were imported into COVIDENCE, a data screening and extraction software. A second search was conducted on October 29, 2022, on the National Library of Medicine website using the search terms YouTube and (covid-19 or coronavirus) and vaccine” which yielded 49 results that were imported into COVIDENCE. Lastly, a third search was conducted by the second author on the National Library of Medicine website on December 2, 2022, using the search terms, “COVID-19 and vaccine and YouTube; and “coronavirus and vaccine and YouTube which returned 22 and 43 results, respectively. Forty-three results returned included the first set of 22 and were imported into COVIDENCE. A total of 393 articles were imported into COVIDENCE which automatically removed 40 duplicates, leaving 353 studies for screening against title and abstract. At this stage, 339 studies were excluded and further full-text review was conducted for 14 studies using inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined below with the final result of 9 articles included in the analysis of the scoping review. The five studies that were excluded were for misaligned outcome measures (n = 4), misaligned interventions (n = 1). The entire search was then repeated using the search terms “YouTube AND immunization AND COVID-19” and no additional studies were identified. The entire review from screening to final inclusion was conducted by two reviewers. Discussion between the authors resolved any conflicts in votes. The authors consulted with each other on the methodology, search terms, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. Figure 1 depicts the data flow.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of data flow.

Inclusion criteria

Criteria for inclusion in the mini-scoping review were English language journal articles published between 2020 and 2022 that mentioned key search terms YouTube and (COVID-19 or coronavirus) and (vaccine or vaccination).

Exclusion criteria

Search results that referred to social media other than YouTube, such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram; non-English language journals.

Analysis

COVIDENCE software was used to extract pertinent information about the articles and exported to an Excel spreadsheet. The study design, whether the study was to the general population or to a specific subset, total number of videos included in the analysis, total cumulative views, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the results were all tabulated. Additionally, limitations and implications are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Articles Included in Mini Scoping Review.

| Search term | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Total number of videos | Method/Measures | Total Cumulative Views | Time Period | Results | Implications | Limitations noted in manuscript | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The first search terms were ‘COVID-19,’ ‘Coronavirus’ and ‘Coronavirus pandemic.’ Then closed captionining text was searched for ‘Vaccine/Vaccines;’ ‘Vaccination/Vaccinations;’ ‘Immunization/Immunize/Immunizations;’ ‘Vaccine-preventable;’ ‘Live-attenuated;’ ‘Inactivated vaccines;’ ‘Subunit,’ ‘recombinant,’ ‘polysaccharide,’ and ‘conjugate vaccine(s);’ ‘Toxoid vaccine(s);’ and ‘Placebo.’ Last round of search on just the keyword ‘Vaccine’ | English language videos, 150 most viewed videos using search terms | non-English language videos, live-streams, or content not related to COVID-19. | 32 | DISCERN, GQS, JAMA benchmark criteria; content categories – Independent Users/Consumers, Professional Organization, University Channels, Entertainments News, Network News, Internet News, Government, Newspaper, Education, or Medical Advertisements/For-Profit Companies. | 13,97,64,188 | Jan-June 2020 | A total of 29 rated as useful and 3 misleading; average quality score 3.63 of 5 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.83), the average accuracy score 1.28 of 4 (SD = 0.81), and the average reliability score was 3.69 of 5 (SD = 1.12). | Low quality scores raise concerns for the information being disseminated to the public. | Ratings subjective. Offset by using multiple scales used before and using 3 raters.Closed captioning could have missed some relevant videos. | |

| ‘COVID-19 and Pregnancy’ | English language videos on COVID-19 and pregnancy, videos with over 100,000 views | Non-English language, less than 100,000 views | 45 | Videos coded for content and technical data, quality evaluated using DISCERN, Vidoe Power Index(VPI) and Global Quality Scale. | 2,35,27,620 | Sept 7–10, 2022 | A total of 38 presented by health care workers, 36 of them recommended vaccination. Network news scored the lowest on quality indices | Healthcare workers in USA proponents of protective features of vaccination | Excluded videos with<100 k views, cross-sectional so changing views and likes not captured. | |

| ‘Pregnancy and COVID-19 Vaccine’ | English language, 50 most widely viewed | Non-English Language | 50 | Content related to vaccine development, manufacturing, fast-tracking, emergency use authorization, eligibility, concerns about adverse reactions, fear, and effectiveness. Additional Categories CDC factsheet on COVID-19 vaccination, 39 a CDC factsheet on COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant and lactating individuals, 6 and joint statements on COVID-19 vaccination from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine (SMFM). | 45,89,613 | Feb, 2021 | Source of uploads were broken down as follows: 44% of videos were from internet/television news; 67.6% of the views. 40% medial professionals;Consumer videos more often mentioned human trials and more often mentioned anti-vaccine sentiment or fear and were also unlikely to mention emergency use authorization. Overall videos often mentioned that vaccines studies did not include pregnant patients (56%, 28/50), that there is not enough data regarding the vaccine and pregnant people (48%, 24/50), and that pregnant people who get COVID-19 have more risk to experience a worse outcome (54%, 27/50). | Information found in most viewed YouTube videos on this topic can quickly become outdated in light of new information regarding the COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy. | Non-representative sample size and limited data on safety of vaccines in pregnant people at the time this study was conducted due to vaccine trial exculsion of pregnant people. | |

| ‘Coronavirus vaccination’ | English language videos, 100 most widely-viewed videos | Non-English Language | 100 | Coding based on CDC fact sheet. | 5,50,86,261 | July and December 2020 | Increase in number and cumulative views from July to Dec. 2020 of videos addressing fear, concerns with vaccine effectiveness and adverse reactions; >80% uploaded by television or internet news, and fewer than 10% from consumer, professionals or entertainment television; most reveiewed topics were vaccine developement process adn fast-tracking in that order. | Potential for social media to provide inaccurate information or have negative influence on vaccine uptake. | Short-time period, only 100 most viewed, limited content coded, don’t know difference between #views and #viewers. No data on characteristics of viewers such as geography or demographcis. Reliance on YouTube search algorithm. | |

| Vacuna Covid,’ ‘Vacuna coronavirus,’ and ‘Vacuna Covid19.’ | Spanish language videos, available for viewing, videos containing content related to COVID-19 vaccines | not available for viewing, language other than Spanish, videos that were duplicated, and videos that did not provide information on COVID-19 vaccines | 118 | 2 authors independenty coded. date of upload, country of publication, type of source (media, health professionals, user-generated content, and others), type of publication, video duration (seconds), message tone (message’s attitude toward the vaccination), and number of views, likes, dislikes and comments. Positive tone defined as clear recommendation for vaccination, negative – arguments against and ambiguous if both positve and negative statements were made and netural if no statements made for or against vaccines. | 5,73,90,500 | Feb, 2021 | Place of origin was broken down as follows: 63.6% origninated in Mexcio and USA; 57.6 created by media, however, vidoes by health professionals garnered significantly higher # of views than those by media and also showed a more positive tone. Positive messages in 53.6% of videos with 53.1% of total views.Most discussed topics included target groups for vaccinations and safety. | COVID-19 vaccination campaigns should monitor the reliability of YouTube information about vaccines. | Cross-sectional design, does not distinguish #views from #viewers, small sample size. | |

| ‘COVID-19 Vaccine’ | 100 most viewed English language videos | Non-English Language | 100 | Upload source categorized, content coded using CDC fact sheet. | 33,410,789 | April, 2020 | Nearly 75% uploaded by news sources. Consumers loaded 16% but accumulated over 25% of views.Professionals uploaded 11% of videos Vaccine manufacturing process and the length of time required for a ready vaccine most frequently mentioned. No significant difference in content uploaded by the 3 sources. Nearly 90% of videos had a live presenter. Others animated. | The number of views (>33 million in just 100 videos) indicates importance of YouTube to disseminate information | Cross-sectional design, does not distinguish #views from #viewers, delimited scope of information on coding form, small sample size. | |

| ‘COVID-19 Vaccine’ | English language videos, audiovisual, ≤1-hour duration, meeting search term, 150. most viewed videos | non-English, non-audiovisual, exceeding 1-hour duration, or videos unrelated to COVID-19 vaccine were excluded. | 122 | Quality and reliability evaluated using DISCERN (mDISCERN) score, the modified Journal of the American Medical Association (mJAMA) score and the COVID-19 Vaccine Score (CVS). | 169,446,382 | July, 2021 | Findings illustrated that 11% of videos (with 18 million views), contradicted WHO or CDC information. These videos also had lower quality scores. | Misinformation regarding COVID-19 vaccines continues to be prevalent in highly viewed content. | No limitations noted in the manuscript | |

| ‘Coronovirus Vaccine’ and ‘COVID-19 Vaccine’ | English Language, description of 1 or more of following: mechanisms of action of vaccine, clinical trial procedures, manufacturing processes, side effects or safety, and vaccine efficacy | Non-English language, no discussion of specified topics. | 48 | Video content and features rated by 2 authors. Using Health on the net Foudnation code of Ethics (HCON) and DISCERN for evaluation. | 3,01,00,561 | December, 2020 | Vaccine trials, side effects, vaccine science and efficacy were the the most often discussed topics; Continued public health measures were promoted by 21% of the videos with only 2 videos deemed to make non factual claims. All but one scored either low or moderate in adherence to HCON. Professionals scored higher than independent users on DISCERN, although medical professionals score the highest overall. | Overall poor quality and low reliability of information pertaining to COVID-19 on YouTube. However, given higher quality of videos featuring professionals, especially medical professinals,public health officicals will beenefit from collaborating with highly viewed medical content producers of videos. | English language videos only, limited search terms, and screening by title relevance irrespective of the content. | |

| ‘COVID-19 Vaccination Rheumatic Disease,’ ‘COVID-19 Vaccine Rheumatic Disease,’ ‘SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination Rheumatic Disease,’ ‘SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine Rheumatic Disease,’ ‘Coronavirus Vaccination Rheumatic Disease’ and ‘Coronavirus Vaccine Rheumatic Disease’ | English language videos | Videos not relevant to the topic, videos in languages other than English, repeated videos, and videos with audio – video problems preventing accurate assessment | 56 | GQS used to evaluate high, medium and low quality, DISCERN for reliability and content coded for vaccine related content:development processes, COVID-19 vaccine types, main features and differences of vaccine types, clinical efficiency, safety dosage regimen, administration techniques, potential interactions with antirheumatic drugs, adverse effects, and cautions; features such as length and source of upload also captured. | median and range; 1409 (32–51,018) | July, 2021 | Approximately 2/3 (37/56)of videos deemed high quality, 12 intermediate and 7 low quality. Of the high quality vidoes 85% were uploaded by a society-organization. No significant difference in views, likes, dislikes or comments by level of quality. | Possible results are consequenec of October 2020 misinformation policy implemented by YouTube. Still, one third of videos were interemediate or low quality. News providers had lower quality vidoes than other upload sources. | English language videos only, cross sectional design, subjectivity in content coding. | |

Ethics approval

As per the policy at William Paterson University, studies not involving human subjects (such as this) are not subject to review by the Institutional Review Board.

Results

Inclusion/Exclusion of studies

Eight of the nine studies that met the final inclusion criteria for this review were cross-sectional and descriptive. One study used a successive sampling with replacement method. Eight of the nine studies included English language videos, while one included Spanish language videos. Upload source was documented in all nine videos and seven categorized videos as being from health worker/medical professionals, television/internet/entertainment news-based sources, consumer/patient//individual users. Two of the studies added categories for government/for-profit organizations, education/university channels and newspapers.40,41 Cumulative view counts reported for the videos included in 8 of 9 the studies ranged from 4.6 million to 169.4 million. One study42 reported a range of view counts from 32 to 51,018.

Characteristics of studies

Of the nine studies, six did not limit the scope of the search on YouTube to a particular demographic or condition. Two of the studies specifically looked at COVID-19 vaccines and pregnancy,43,44 and one study analyzed videos related to COVID-19 vaccines and rheumatic disease.42 Content elements were coded as binary variables (YES/NO), depending on whether they were mentioned or not mentioned. The determination of which content elements to code were based on a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) fact sheet in three of the studies.43,45,46 Two studies developed additional coding criteria based on statements or guidelines from reputable organizations such as the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) and the Society for Maternal and Fetal Medicine (SMFM)43 World Health Organization (WHO) or CDC.40 Two of the studies created study-specific parameters based on literature on the topic.42,44

Quality and accuracy of information in studies

Four of the studies used DISCERN to rate the quality and reliability of the information provided.

DISCERN is a 16-point rating scale with three sections developed to evaluate the quality of web-based written material providing consumer health information related to clinical treatment choices.47

One study used a modified DISCERN scale. Other scales used to rate quality were the Global Quality Scale (3 studies), JAMA criteria (1) modified JAMA (1), Health on the Net Foundation Code (1). In one study,40 an unvalidated COVID Vaccine Score (CVS) was developed based on information obtained from prior published literature. Another study48 grouped videos as 1) having a positive tone if a clear recommendation was made for vaccines; 2) having a negative tone if arguments were presented against vaccination and 3) ambiguous if both positive and negative statements were made and 4) neutral if no statements made for or against vaccines.

Summary of individual studies

Two studies examined YouTube videos related to COVID-19 vaccines and pregnancy. The first study43 used a CDC fact sheet to code the content of 50 of the most widely viewed English videos, discussing COVID-19 vaccines in relation to pregnancy in early 2021, during the initial phase of the vaccine rollouts. The most common upload source of the videos was television-internet-based news (44%) and medical professionals (40%). Although consumers uploaded only 6% of the videos in the study, they were most likely to express anti-vaccine sentiment, fear or distrust of vaccines. In contrast, medical professionals more frequently mentioned the low likelihood of vaccines causing harm while breastfeeding.

The second study related to COVID-19 vaccines and pregnancy44 analyzed 45 English language videos on YouTube pertaining to COVID-19 vaccines and pregnancy. Content evaluation categories ranged from broad topic areas covering COVID-19 vaccination in general to its specific effects on breastfeeding and pregnancy outcomes, miscarriage, maternal mortality, and fetus anomaly. A majority (84%) of the videos were presented by health-care workers, with all but 2 recommending vaccination. In addition to describing the characteristics such as upload source and topics mentioned, the videos were rated using a Video Power Index (VPI), DISCERN and the Global Quality Scale (GQS). VPI computed a ratio of likes in relation to overall likes and dislikes. The mean quality indices were lowest for videos uploaded by network news sources.

One of the nine studies42 evaluated the quality and reliability of videos discussing COVID-19 and rheumatic disease, using GQS and DISCERN. Analysis revealed two-thirds of the 56 videos included in the study to be of high quality. Eighty-five percent of the high-quality videos were uploaded by a society or organization. The quality of the videos may have been affected by YouTube’s misinformation policy implemented in 2020.38 In the early stages of the pandemic, in April 2020, researchers45 studied the implications for uptake of vaccines by evaluating 100 of the most-widely viewed (indicated by filtering the number of views) videos discussing the vaccine development process. Nearly 75% of videos were uploaded by news sources. Consumers uploaded 16% of videos, but accumulated over 25% of views. Professionals uploaded a mere 11% of videos. Vaccine manufacturing process and the length of time required for a ready vaccine were the most frequently mentioned topics. No significant difference was found in the content uploaded by the three different sources.

Li et al.40 determined the accuracy, usability and quality of the most widely viewed YouTube videos on COVID-19 vaccination using a modified DISCERN and modified JAMA scale. Additionally, a COVID Vaccine Scale score was developed using WHO and CDC guidelines. Videos (n = 122) were scored 1 if they were factually correct based on the guidelines, 0.5 if they were ambiguous and 0 if they contained one or more nonfactual statements.

The majority of videos were uploaded by network news, followed by health professionals.

Although 89.3% of the videos were deemed factual, the 11% that were nonfactual garnered nearly 18 million views.

Hernandez-Garcia and Gimenez-Julvez48 evaluated 118 Spanish language videos discussing COVID-19 vaccines. Besides studying characteristics of videos such as country of origin and upload source, the tone of messages indicating attitude toward vaccination was also analyzed. Of the Spanish language videos, 63.6% originated in Mexico and USA; 57.6% were created by media. Videos uploaded by health professionals garnered a significantly higher number of views than those by the media and also showed a more positive tone. Positive messages were identified in 53.6% of videos with 53.1% of total views. The most discussed topics included target groups for vaccinations and safety of vaccinations.

Chan et al.49 evaluated the reliability and quality of information on COVID-19 vaccination in 48 YouTube videos. Vaccine trials, side effects, vaccine science and efficacy were the most often discussed topics; Continued public health measures were promoted by 21% of the videos with only 2 videos deemed to make non-factual claims. All but one scored either low or moderate in adherence to HCON. Professionals scored higher than independent users on DISCERN, although medical professionals score the highest overall.

Basch et al.46 conducted a successive sampling with replacement study to identify the source and characteristics of the 100 most widely viewed videos on COVID-19 vaccines. Two samples were obtained from a YouTube search in July and December of 2020 with 29 from the July sample retained in December. There was a significant increase in number and cumulative views from July to December, 2020 of videos addressing fear, concerns with vaccine effectiveness and adverse reactions; More than 80% of the videos were uploaded by television or internet news, and fewer than 10% from consumer, professionals, or entertainment television; most reviewed topics were vaccine development process and fast-tracking in that order.

Marwah et al.41 studied the quality, accuracy, and reliability of YouTube videos on COVID-19 vaccines. Results of an initial search on “coronavirus” and “COVID-19” were sorted by view count and 150 of the most widely viewed videos were selected for further analysis. A qualitative analysis of closed-caption text from the 150 videos for mention of the word ‘vaccine,’ yielded 32 videos. DISCERN, JAMA benchmark criteria and the Global Quality Scale (GQS) were utilized to rate the 32 videos. Twenty-nine of the videos were deemed useful and three misleading; The average quality score was 3.63 of 5 (standard deviation [SD] = 0.83), the average accuracy score 1.28 of 4 (SD = 0.81), and the average reliability score was 3.69 of 5 (SD = 1.12).

Discussion

The findings of this mini-scoping review indicate that there are relatively few studies evaluating YouTube videos related to COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination. Study methodology varies across studies in several aspects, as highlighted in this review. First, while filtering by view count is commonplace in YouTube studies, several studies included in this review do not appear to seek out the most commonly viewed videos. View counts, especially as they pertain to COVID-19 content are subject to algorithms put in place by YouTube. Filtering by view count does not provide information on who is viewing the video, the percent of the video that was observed, what information is retained, and how content may influence behavior. Nonetheless, the view count is commonly being used as a metric for popularity, which infers a level of impact.

As noted in a synthesis of literature on vaccine hesitancy in the media (both traditional and social media), studies of this nature are often devoid of a theoretical framework.50 In concert, another review of social media studies in general found that the overwhelming number of studies included in the review did not include a theoretical framework.51 The findings of this mini-review echo these sentiments in that the included papers were not linked to health education or health communication theories. Use of theories can provide an in-depth understanding of concepts or issues revealed through analysis of social media. Further, use of theoretical frameworks can provide a greater opportunity for evidence-based reflection.51 A search of the literature did not reveal any systematic reviews on COVID-19 vaccinations and YouTube, nor did we identify review studies on vaccination in general. One review examined general healthcare information.52 Findings were similar to those in this mini scoping review in that the designs tended to rely on content analysis and that YouTube videos contained anecdotal information that was generally unreliable and that professionally created videos were more reliable.52 While each study in this review sets out to describe content in one or more aspects, there is a gap in the literature in terms of evaluating videos related to COVID-19 vaccines for accuracy. In particular, this is concerning due to the large number of videos created by nonprofessionals. YouTube has an algorithm that prioritizes COVID-19 videos that are the most reliable.

As a result, almost all studies that perform searches on YouTube likely overestimate quality. Since content on YouTube persists regardless of knowledge gains, it is difficult to assess how much of the information was aligned with scientific knowledge at the time of creation. With greater efforts on behalf of YouTube Health to create valid and reliable health content, there is greater potential for clarity in trusted sources and/or validated information.

Moreover, most studies conducted on YouTube have a cross-sectional design, which means that results are time-bound, limiting temporal generalizability. This is especially true for a medium like YouTube which is dynamic, with content and number of views changing almost daily, if not hourly. Another significant limitation in YouTube analysis studies is the sheer volume of videos that searches can return. Researchers then pick arbitrary cutoff limits for the number of videos included. These limitations are seemingly universal for this type of research.

This mini scoping review is also limited. Despite researchers’ efforts, it is possible that papers may be excluded from the review due to the database in which they are stored. The methods relied on COVIDENCE systematic review software, use of different software may reveal different content, which is why we supplemented our search with manual techniques. Furthermore, the inclusion of papers written in English only does not adequately represent the breadth of literature on a platform that is accessed worldwide. Despite these limitations, the review results have implications for public health practitioners in terms of creating evidence-based, accurate, literacy-controlled video content that is far-reaching, especially to underserved areas and communities.

This mini-scoping review had narrow search criteria on a niche topic and therefore included only those studies that evaluated content of YouTube videos related COVID-19 vaccines. Studies have been conducted in which the characteristics of YouTube videos disseminated on other social media platforms such as Twitter were examined.53 Future scoping reviews can focus on such multi-platform YouTube video distribution, differences in methodology and assessment of accuracy by vaccine type, and evaluate changes over time.

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author’s contribution

SN and CHB conceptualized the study. SN conducted the search. SN and CHB conducted screening, data extraction, drafted and edited the manuscript.

References

- 1.Statement for healthcare professionals: how COVID-19 vaccines are regulated for safety and effectiveness. World Health Organization. 2022 Mar no date [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.who.int/news/item/17-05-2022-statement-for-healthcare-professionals-how-covid-19-vaccines-are-regulated-for-safety-and-effectiveness.

- 2.Bok K, Sitar S, Graham BS, Mascola JR.. Accelerated COVID-19 vaccine development: milestones, lessons, and prospects. Immunity. 2021;54(8):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FDA Takes Key Action in Fight Against COVID-19 By Issuing Emergency Use Authorization for First COVID-19 Vaccine . U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19.

- 4.Overview of COVID-19 Vaccines . Centers for disease control and prevention. 2022. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/different-vaccines/overview-COVID-19-vaccines.html. [PubMed]

- 5.Your COVID-19 Vaccination . Centers for disease control and prevention. 2022. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/your-vaccination.html. [PubMed]

- 6.Boehmer TK, Kompaniyets L, Lavery AM, Hsu J, Ko JY, Yusuf H, Romano SD, Gundlapalli AV, Oster ME, Harris AM. Association between COVID-19 and myocarditis using hospital-based administrative data — United States, March 2020–January 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(35):1228–32. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7035e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews N, Tessier E, Stowe J, Gower C, Kirsebom F, Simmons R, Gallagher E, Thelwall S, Groves N, Dabrera G, et al. Duration of protection against mild and severe disease by covid-19 vaccines. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):340–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2115481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Havers FP, Pham H, Taylor CA, Whitaker M, Patel K, Agline O, Kambhampati AK, Milucky J, Zell E, Moline HL, et al. COVID-19-associated hospitalizations among vaccinated and unvaccinated adults 18 years or older in 13 US States, January 2021 to April 2022. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(10):1071–81. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scobie HM, Johnson AG, Suthar AB, Severson R, Alden NB, Balter S, Bertolino D, Blythe D, Brady S, Cadwell B, et al. Monitoring incidence of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, by vaccination status - 13 U.S. jurisdictions, April 4-July 17, 2021. MMWR. 2021;70(37):1284–90. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenforde MW, Self WH, Adams K, Gaglani M, Ginde AA, McNeal T, Ghamande S, Douin DJ, Talbot HK, Casey JD, et al. Association between mRNA vaccination and COVID-19 hospitalization and disease severity. JAMA. 2021;326(20):2043–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.19499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tenforde MW, Self WH, Gaglani M, Ginde AA, Douin DJ, Talbot HK, Casey JD, Mohr NM, Zepeski A, McNeal T, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA vaccination in preventing COVID-19–Associated invasive mechanical ventilation and death — United States, March 2021–January 2021. MMWR. 2022;71(12):71. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7112e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaccines . Johns Hopkins University and medicine coronavirus resource center. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/vaccines.

- 13.Funk C, Tyson A. Growing share of Americans say they plan to get a COVID-19 vaccine – or already have. Pew Research Center Science & Society; 2021. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/03/05/growing-share-of-americans-say-they-plan-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-or-already-have/. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sallam M. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy worldwide: a concise systematic review of vaccine acceptance rates. Vaccines. 2021;9(2):160. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9020160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasmin F, Najeeb H, Moeed A, Naeem U, Asghar MS, Chughtai NU, Yousaf Z, Seboka BT, Ullah I, Lin CY, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in the United States: a systematic review. Front Pub Heal. 2021;9:770985. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.770985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaccine Acceptance . Johns Hopkins center for communication programs. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://ccp.jhu.edu/kap-covid/vaccine-acceptance.

- 17.Gisondi M, Barber R, Faust J, Raja A, Strehlow M, Westafer L, Gottlieb M. A deadly infodemic: social media and the power of COVID-19 misinformation. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(2):e35552. doi: 10.2196/35552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basch CH, Meleo-Erwin Z, Fera J, Jaime C, Basch CE. A global pandemic in the time of viral memes: COVID-19 vaccine misinformation and disinformation on TikTok. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2022;17(8):2373–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1894896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmerman T, Shiroma K, Fleischmann KR, Xie B, Jia C, Verma N, Lee MK. Misinformation and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Vaccine. 2023;41(1):136–44. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grimes DR, Serra R. Medical disinformation and the unviable nature of COVID-19 conspiracy theories. PLoS One. 2021;6(3):e0245900. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.León B, Martinez-Costa M, Salaverria R, López-Goñi I. Health and science-related disinformation on COVID-19: a content analysis of hoaxes identified by fact-checkers in Spain. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0265995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basch CH, Kecojevic A, Wagner VH. Reporting of recombinant adenovirus-based COVID-19 vaccine adverse events in online versions of three highly circulated US newspapers. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2021;17(12):5114–9. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1979847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh YL, Rak S, SteelFisher GK, Bauhoff S. Effect of the suspension of the J&J COVID-19 vaccine on vaccine hesitancy in the United States. Vaccine. 2022;40(3):424–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cascini F, Pantovic A, Al-Ajlouni Y, Failla G, Puleo V, Melnyk A, Lontano A, Ricciardi W. Social media and attitudes towards a COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic review of the literature. EClin Med. 2022;48:101454. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larson HJ, Gakidou E, Murray CJL, Longo DL. The vaccine-hesitant moment. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(1):58–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2106441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muric G, Wu Y, Ferrara E. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy on social media: building a public Twitter data set of antivaccine content, vaccine misinformation, and conspiracies. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(11):e30642. doi: 10.2196/30642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palamenghi L, Barello S, Boccia S, Graffigna G. Mistrust in biomedical research and vaccine hesitancy: the forefront challenge in the battle against COVID-19 in Italy. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):785–8. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00675-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vaccine equity. World Health Organization . [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.who.int/campaigns/vaccine-equity.

- 29.Feldman DB. Hope and fear in the midst of coronavirus: what accounts for COVID-19 preparedness? Am Behav Sci. 2021;65(14):1929–50. doi: 10.1177/00027642211050900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CERC: Psychology of a Crisis.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . CERC Manual. 2019. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://emergency.cdc.gov/cerc/manual/index.asp.

- 31.Duffy C. How health officials and social media are teaming up to fight the coronavirus ‘infodemic’. CNN Business. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/01/tech/coronavirus-social-media-reliable-sources/index.html.

- 32.Infodemic . World health organization. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic.

- 33.Zarocostas J. How to fight an infodemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):676. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30461-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Badell-Grau RA, Cuff JP, Kelly BP, Waller-Evans H, Lloyd-Evans E. Investigating the prevalence of reactive online searching in the COVID-19 pandemic: infoveillance study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(10):e19791. doi: 10.2196/19791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valika TS, Maurrasse SE, Reichert L. A second pandemic? Perspective on information overload in the COVID-19 Era. Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2020;163(5):931–3. doi: 10.1177/0194599820935850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Auxier B, Anderson M. Social media use in 2021. Pew Research Center: internet, Science & Tech. 2021. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/.

- 37.Stocking G, Kessel PV, Barthel M, Matsa KE, Khuzam M. Many Americans get news on YouTube, where news organizations and independent producers thrive side by side. Pew Research Center; 2020. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/09/28/many-americans-get-news-on-youtube-where-news-organizations-and-independent-producers-thrive-side-by-side/. [Google Scholar]

- 38.COVID-19 medical misinformation policy . YouTube help. [accessed 2022 Dec 31]. https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/9891785?hl=en&ref_topic=10833358.

- 39.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2002;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li HO-Y, Pastukhova E, Brandts-Longtin O, Tan MG, Kirchhof MG. YouTube as a source of misinformation on COVID-19 vaccination: a systematic analysis. BMJ Global Health. 2022;7(3):e008334. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marwah HK, Carlson K, Rosseau NA, Chretien KC, Kind T, Jackson HT. Videos, views, and vaccines: evaluating the quality of COVID-19 communications on YouTube. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 202:1–7. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2021.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kocyigit BF, Akyol A. YouTube as a source of information on COVID-19 vaccination in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41(12):2109–15. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-05010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Laforet PE, Basch CH, Tang H. Understanding the content of COVID-19 vaccination and pregnancy videos on YouTube: an analysis of videos published at the start of the vaccine rollout. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(5):2066935. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2066935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Atigan A. Analysis of YouTube videos on pregnant COVID-19 patients during the pandemic period. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e29934. doi: 10.7759/cureus.29934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Basch CH, Hillyer GC, Zagnit EA, Basch CE. YouTube coverage of COVID-19 vaccine development: implications for awareness and uptake. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2020;16(11):2582–5. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1790280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Basch CE, Basch CH, Hillyer GC, Meleo-Erwin ZC, Zagnit EA. YouTube videos and informed decision-making about COVID-19 vaccination: successive sampling study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(5):e28352. doi: 10.2196/28352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welcome to DISCERN . DISCERN. [accessed 2022 Dec 30]. http://www.discern.org.uk/index.php.

- 48.Hernandez-Garcia I, Gimenez-Julvez T. Characteristics of YouTube videos in Spanish on how to prevent COVID- 19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4671. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17134671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chan C, Sounderajah V, Daniels E, Acharya A, Clarke J, Yalamanchili S, Normahani P, Markar S, Ashrafian H, Darzi A. The reliability and quality of YouTube videos as a source of public health information regarding COVID-19 vaccination: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(7):e29942. doi: 10.2196/29942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin JD. Media data and vaccine hesitancy: scoping review. JMIR Infodemiol. 2022;2(2):e37300. doi: 10.2196/37300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Osch W, Coursaris CK. A meta-analysis of theories and topics in social media research 2015. 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences; 2015. p. 1668–75; Kauai, HI, USA. doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2015.201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Madathil KC, Rivera-Rodriguez AJ, Greenstein JS, Gramopadhye AK. Healthcare information on YouTube: a systematic review. Health Informatics J. 2015;21(3):173–94. doi: 10.1177/1460458213512220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ginossar T, Cruickshank IJ, Zheleva E, Sulskis J, Berger-Wolf T. Cross-platform spread: vaccine-related content, sources, and conspiracy theories in YouTube videos shared in early Twitter COVID-19 conversations. Human Vaccines Immunother. 2022;18(1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.2003647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]