Abstract

Background:

Unintended pregnancies contribute to the high burden of unsafe abortion, maternal deaths and morbidities among undergraduates.

Objective:

To assess the determinants of good knowledge and evaluate the trends in the practice of Emergency Contraception (EC) among female undergraduates.

Methods:

This was a cross sectional study involving four hundred and twenty female undergraduates from two universities in Ibadan, Nigeria. Participants were recruited from their hostels and classrooms. Data collection was done using self-administered questionnaires and good knowledge was defined as three correct answers to five questions testing knowledge. The questionnaires also addressed their practices of EC. The data was stored on the computer, cleaned and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05.

Results:

Two hundred and fourteen (51.0%) participants were aware of EC and the common sources were friends (43.4%), media (42.9%) and pharmacies (42.0%). One hundred and sixty-four participants (39.1%) had good knowledge of EC. Participants in the age group 20-24 years, second year of study, those who were aware of EC and had ever used EC were associated with good knowledge. Less than half (48%) of the sexually active participants used EC in the past six months and Levonogestrel (51%) was the commonest EC used. Menstrual irregularity and abdominal pain were the major side effects of EC.

Conclusion:

The practice of EC is poor and with poor knowledge demonstrated among female undergraduates. There is therefore the need to improve information and access to EC in the university community.

Keywords: Emergency contraception, Determinants, Knowledge, Practice, Female undergraduates

INTRODUCTION

Unintended pregnancies account for approximately forty percent of all pregnancies worldwide.1 With this growing scourge, it is no surprise that over 44 million pregnancies end in abortion annually. In Africa, many of these abortions being unsafe are major contributors to maternal and infant mortality.2 It is common knowledge that youths have risky sexual behaviours and constitute a high-risk group for these unwanted pregnancies.3-5 Despite the social and cultural importance of childbearing in African societies, unwanted pregnancies are a source of concern in most families. This problem is magnified in unmarried youths, and those who follow through with the pregnancies have higher unmet social needs and obstetric risks.5-7

Contraceptive use is an important strategy for the prevention of unwanted pregnancy and consequently reduces the incidence of induced abortion. In developing countries where the fertility rates are high, contraceptive use will guarantee human and socioeconomic development.2 Furthermore, the rate of induced abortion is an appropriate indicator of the current state of medical care and family planning in any country.8

Studies have shown varying levels of knowledge, attitude, and practice of contraception among adolescents in Nigeria.9,10 The Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey in 2018 revealed that contraception prevalence rates in the country were low while modern contraceptive use was higher among sexually active unmarried women (28%) than among currently married women (12%).11 The promotion of emergency contraception (EC) may be a 'second chance method' or an 'option B' in preventing pregnancy in adolescents with an unmet need, improper and/or inconsistent use of contraception, and those who have experienced coerced unprotected sex or in cases of sexual assault.12

EC is defined as any drug or device which when used after intercourse will prevent pregnancy. Since the first description of EC in 1960, its popularity has increased but knowledge is still limited globally.13 Generally, a lack of awareness restricts access to the use of EC, and increased access is generally associated with increased use. It has also been shown that good knowledge of EC does not translate to adequate uptake.14

Currently, there are several options for EC, including progestin-only pills (ECPs) which contain Levonorgestrel, progesterone modulators (Ulipristal acetate), anti-progesterone synthetic steroids (Mifepristone), and the copper intrauterine device (IUD).15 In many countries, Levonorgestrel is the most available, accessible, and acceptable of the lot.1

Youths in Nigeria have poor awareness, knowledge, and practice of EC.12,16 Ajayi et al. revealed that some female undergraduates erroneously use non-emergency contraceptive pills and concoctions as EC in Nigeria.14 It is important to study the awareness, practice, and knowledge of females to EC as these should be the major drivers of its uptake since the available options are tailored to their use, and females bear the brunt of the consequences of unwanted pregnancies.

This study aimed to assess the awareness and knowledge of emergency contraception among young females with undergraduates as a case study. The results from this study will help develop strategies necessary in reducing morbidities and mortalities from unwanted pregnancies and achieving universal access to sexual and reproductive health.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study involving four hundred and twenty female undergraduates from two Nigerian Universities in Ibadan, namely University of Ibadan (UI) and Lead City University (LCU), Ibadan. The UI, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria is a public university and the oldest degree-awarding institution in Nigeria which is made up of ninety-two academic departments organised into 17 faculties. LCU, Ibadan, on the other hand, is a private university founded in 2005 and is made up of seven faculties.

Ethical approval was obtained from the UI/University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Institution Research Board. The sample size was calculated using the Kish and Leslie formula for cross-sectional studies, assuming a 95% level of confidence and 5% margin of error. The proportion of sexually exposed undergraduates of 48.2% from a previous similar study was used in the sample size calculation.

The five institutions in Ibadan, namely Ajayi Crowther University, LCU, Kola Daisi University, Dominion University, and UI, were allocated numbers from 1-5, folded and put in an opaque envelope, and two sample institutions were selected by simple random sampling techniques, while participants were recruited from their halls of residence and classrooms. Four research personnel were trained to collect the data using self-administered, pre-tested questionnaires. Good knowledge of EC was defined as three correct options in a five-item questions testing knowledge. The confidentiality of participants was ensured throughout the study.

The data was stored on the computer, cleaned and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22. Data analysis was summarized using descriptive statistics and charts. Test of associations was done using Chi square and Yates correction, while statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

The mean age of the respondents was 20.4 + 3.3 years. More than half (228; 54.0%) of the respondents were between 20 and 24 years old. Most were of the Yoruba tribe (359; 85.5%), Christian (324; 77.2%), and in their first year of study (120; 28.6%). A vast majority were single (412; 98.1%) as expected in many undergraduate programs, and a little over half (216; 51.4%) of the respondents were aware of EC. This is shown in table 1.

Table 1:

Socio-demographic data of the study participants

| Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (in years) | ||

| <20 | 161 | 38.4 |

| 20-24 | 228 | 54.0 |

| 25-29 | 27 | 6.6 |

| 30-34 | 2 | 0.5 |

| ≥35 | 2 | 0.5 |

| Year of Study | ||

| 1st | 120 | 28.6 |

| 2nd | 111 | 26.4 |

| 3rd | 72 | 17.1 |

| 4th | 83 | 19.8 |

| 5th | 34 | 8.1 |

| Religion | ||

| Islam | 93 | 22.1 |

| Christianity | 324 | 77.2 |

| Traditional | 3 | 0.7 |

| Tribe | ||

| Yoruba | 359 | 85.5 |

| Hausa | 3 | 0.7 |

| Igbo | 26 | 6.2 |

| Others | 32 | 7.6 |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 412 | 98.1 |

| Married | 8 | 1.9 |

| Total | 420 | 100.0 |

Table 2 showed the awareness and practice of EC. Of those who were aware of EC, friends were the largest contributors with 43.4% closely followed by media and pharmacies with 42.9% and 42%, respectively. Health workers, parents, and family planning clinics had the least impact on awareness of EC. One hundred and fifty-six participants (37.1%) had ever had sex in the past, and 81 participants (19.3%) had ever used EC. Table 2 showed that 102 (65.4% of those who had ever had sex) had been sexually active in the last 6 months, most of them in the preceding month of the study. About 3 out of 10 female undergraduates were willing to recommend EC, while two-thirds of those who had 'ever had sex' approved of EC. Forty-eight percent of the sexually active group used EC in the last 6 months, mostly (55.2%) because of a condom break. Levonorgestrel (51%) was the most used EC, and the majority (57.1%) used EC within 24 hours of sex.

Table 2:

Awareness and practice of EC among the study participants

| Frequency (N) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Awareness of EC | ||

| Yes | 219 | 52.1 |

| No | 201 | 47.9 |

| Source of Awareness of EC | ||

| Pharmacy | 92 | 42.0 |

| Health Worker | 47 | 21.5 |

| Family Planning Unit | 22 | 10.5 |

| Parents | 36 | 16.4 |

| Friends | 95 | 43.4 |

| Books | 66 | 30.1 |

| Media | 94 | 42.9 |

| Sexual Activity | ||

| Ever had sex | 156 | 37.1 |

| Sex in the past 6 months | 102 | 24.3 |

| Practice of EC | ||

| Recommend EC to others | 124 | 29.5 |

| Ever used EC | 81 | 19.3 |

| Ever used EC in the past 6 months | 49 | 11.6 |

| Approve use of EC* (n=102) | 60 | 58.8 |

| Type of EC used in the last use** (n==49) | ||

| Intrauterine Device | 7 | 14.3 |

| Levonorgestrel (Postinor) | 25 | 51.0 |

| Contraceptive Pills | 17 | 34.7 |

Among currently sexually active participants

Among participants who are sexually active and used emergency contraception within the last 6 months of the study

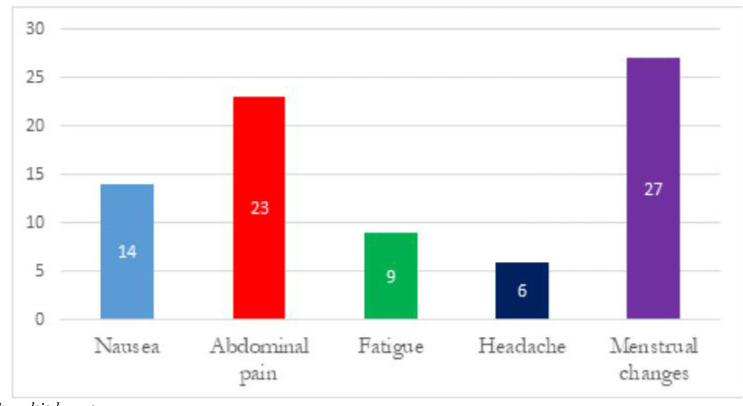

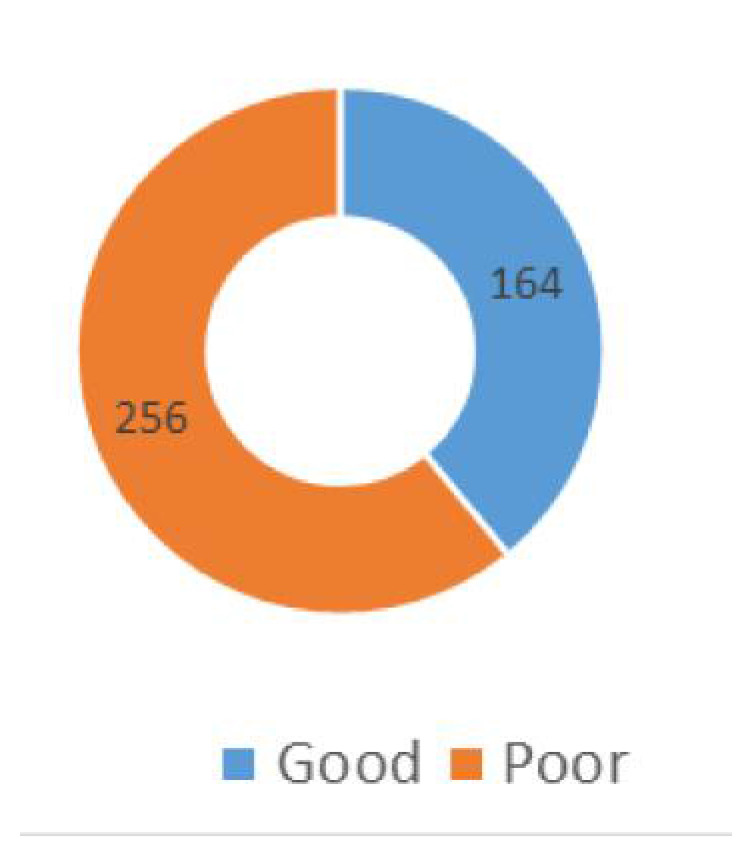

The common problems associated with the use of EC among the participants who had used EC in the past six months of the research were menstrual irregularity (27; 55.1%) and abdominal pains (23; 46.9%). This is shown in figure 1. Only about two-fifths (164; 40%) of the female undergraduates had good knowledge of EC as shown in figure 2.

Figure. 1:

Problems with use of emergency contraception among the study participants

Figure. 2:

Knowledge scores of emergency contraception among the study participants

Table 3 shows good knowledge score of EC was associated with increasing age and higher levels of education. The female undergraduates who were aware of EC, used EC in the last 6 months, or ever used EC had good knowledge scores. Those who were willing to recommend EC to others or had a partner who used EC had good knowledge scores too, however, the partner's approval did not influence knowledge of EC.

Table 3:

Associations with knowledge of emergency contraception among female undergraduates

| Variable | Good Knowledge | Poor Knowledge | Chi-square | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=164) | (n=256) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Age group (in years) | |||||

| <20 | 56 | 105 | 10.1 | *0.038 | |

| 20-24 | 88 | 140 | |||

| 25-29 | 18 | 9 | |||

| 30-34 | 1 | 1 | |||

| ≥35 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Level of Education (year) | |||||

| 1st | 25 | 95 | 29.8 | <0.001 | |

| 2nd | 47 | 64 | |||

| 3rd | 30 | 42 | |||

| 4th | 40 | 43 | |||

| 5th | 22 | 12 | |||

| Religion | |||||

| Islam | 30 | 63 | 5.04 | *0.28 | |

| Christianity | 132 | 192 | |||

| Traditional | 1 | 1 | |||

| Others | 1 | 0 | |||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Single | 158 | 254 | 3.023 | *0.082 | |

| Married | 6 | 2 | |||

| Awareness of EC | |||||

| Yes | 144 | 75 | 138.8 | <0.001 | |

| No | 20 | 181 | |||

| Ever used EC | |||||

| Yes | 57 | 24 | 41.4 | <0.001 | |

| No | 107 | 232 | |||

| Sex in the past 6 months | |||||

| Yes | 58 | 44 | 18.0 | <0.001 | |

| No | 106 | 212 | |||

| Recommend to others | |||||

| Yes | 77 | 47 | 39.3 | <0.001 | |

| No | 87 | 209 | |||

Yates correction

The associations with the use of EC among the sexually active participants are depicted in Table IV. The age group (p < 0.001), level of education (p = 0.002), knowledge of EC (p < 0.001), willingness to recommend EC to others (p < 0.001), and partner's approval (p = 0.002) were statistically significant.

Table 4:

Associations with the use of EC among sexually active participants

| Variable | Use of EC | Non-use of EC | Chi-square | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n %) | (n %) | ||||

|

| |||||

| Age group (Years) | |||||

| <20 | 23 (22.6) | 138 (40.7) | 41.8 | *<0.001 | |

| 20-24 | 59 (57.8) | 179 (56.2) | |||

| 25-29 | 19 (18.6) | 8 (2.5) | |||

| 30-34 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| ≥35 | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| Level of Education (Year) | |||||

| 1st | 15 (14.7) | 105 (33.1) | 17.32 | 0.002 | |

| 2nd | 26 (25.5) | 85 (26.7) | |||

| 3rd | 27 (26.5) | 46 (14.5) | |||

| 4th | 25 (24.5) | 57 (17.9) | |||

| 5th | 9 (8.8) | 25 (7.8) | |||

| Religion | |||||

| Islam | 16 (15.6) | 77 (24.2) | 4.49 | *0.212 | |

| Christianity | 84 (82.4) | 240 (75.5) | |||

| Traditional | 1 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | |||

| Others | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Marital Status | |||||

| Single | 98 (96.1) | 314 (98.7) | 1.68 | *0.195 | |

| Married | 4 (3.9) | 4 (1.3) | |||

| Knowledge of EC | |||||

| Good | 83 (81.4) | 173 (54.4) | 23.80 | <0.001 | |

| Poor | 19 (18.6) | 145 (45.6) | |||

| Recommend EC to others | |||||

| Yes | 76 (77.0) | 64 (20.1) | 111.55 | <0.001 | |

| No | 26 (23.0) | 264 (79.9) | |||

| Partner's approval of EC | |||||

| Approves | 21 (20.6) | 117 (36.8) | 9.19 | 0.002 | |

| Disapproves | 81 (79.4) | 201 (63.2) | |||

| Total | 102 (100.0) | 308 (100.0) | |||

Yates correction

DISCUSSION

Most of the students were single and aged between 20 and 24 years which was comparable with similar studies among undergraduates in Nigeria, Ghana, Ethiopia, and Cameroon.15-19 In a study in the South-West of Nigeria, the awareness levels of EC were just average and although higher than the studies from Ile-Ife (South-West) and Anambra (South-East), studies in Nigeria still fell short of surveys from Cameroon and Ethiopia.10,16,20,21 Friends, media, and pharmacies were the major influencers of awareness in this population of female undergraduates and unfortunately each of these was independently greater than the combination of healthcare workers and the family planning unit together. It is rather unfortunate that awareness of EC is skewed towards these unvetted sources. The quality of information from these sources needs to be investigated because this may influence knowledge of EC and consequently improve uptake of EC.19

Good knowledge scores of EC were only demonstrated in two-fifths of these young females, and this was significantly associated with awareness. It is very probable that higher scores will have been attained with quality sources of information like health workers and the family planning service providers. A qualitative study among female undergraduates in Ekiti, South-West, Nigeria revealed many unconventional and unproven methods adopted for EC like Ampiclox, "Alabukun" (a local brand of analgesic), saltwater solution, and lime and potash which many of the young females perceived to be effective in preventing unplanned pregnancies. There was a strong recommendation by friends for these unproven methods.14 Kongnyuy et al. in Cameroon revealed that less than a tenth of a mixed undergraduate population had adequate knowledge of EC, an outcome which was associated with identified medical sources, female sex, and previous use of ECPs.20 In another female-dominated undergraduate population with low knowledge levels, younger age was associated with good knowledge.12 It is imperative that many other studies on this subject matter use an objective scoring system to assess knowledge of EC.

Studies in Ethiopia revealed that the uptake of EC increased with age. These authors also noted increased knowledge with higher levels of education, a finding which is in keeping with this study.19,21 We also noted associations between good knowledge scores and having 'ever had sex', previous use of EC (also use in the previous 6 months), or having a partner who had used EC in the past. Likewise, other studies in Nigeria acknowledge that good knowledge of EC was a significant predictor of its use.12,17 About a third of our respondents were sexually active like many other surveys among females of tertiary institutions in Africa.12,17,19,21 However, in a study in Ile-ife, Nigeria, 86.6% of the population were sexually active, out of which 89% were using a form of contraception. This level of sexual activity would have birthed a high unwanted pregnancy rate but for the commensurate consistent use of diverse forms of modern contraception.10 About 1 in 5 females in this study had used EC in the past with ECP containing Levonogestrel being the most common of the options available. These pills are highly effective in preventing pregnancies and one tablet of 0.75 mg Levonogestrel should be taken as soon as possible but not later than 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, followed by another pill 12 hours later.8 It is encouraging to know that an overwhelming majority of those who had used EC used it appropriately within the stipulated time contrary to studies that have shown that many did not know the correct timing for taking ECPs.16,20 EC should not be subjected to frequent use as these methods are not without side effects which may be cumulative. With a little under half of the respondents attesting to rare use, there is still room for improvement in this regard.

Male partners have a prominent role with regards to adopting contraceptive methods (EC inclusive). In San Francisco, United States of America, surveys among women, most of whom were aware of EC, identified some factors like male dominance, male pressure for sex, and male partner unhappy with a pregnancy as factors associated with the use of EC.22,23 Among the female undergraduates who were sexually active in this study, 58.8% of their partners approved of EC. Interestingly, this was not associated with the respondent's knowledge of EC, a finding which was incongruent with another study in South-west Nigeria.12 It may mean that this approval may have just empowered the females to adopt one form of EC without creating a forum for discussing the mechanism(s) of action, correct use, and side effects that may be expected. The most common reason for using EC was condom break with most reporting menstrual changes and abdominal pain as common side effects. It is refreshing to know that there was a significant association between good knowledge of EC and recommending it to others. It may, therefore, mean that these females with good knowledge may propagate good practice while recommending EC.

Our study on knowledge of EC among this young female undergraduate population is necessary to improve uptake of EC, but it has its limitations. This survey was conducted among an educated cohort and as such may not be representative of the general population. Due to the sensitive nature of questions, the responses may have been subjected to bias. It is very likely that a mixed methods approach incorporating in-depth interviews may highlight more factors (like previous or current pregnancies, financial status, and regular use of other forms of modern contraception) that may be associated with knowledge of EC and some misconceptions regarding EC.

CONCLUSION

This conclusion of this study is that the awareness and knowledge levels of EC among female undergraduates are low. There is a need to improve the quality of the source of awareness. We strongly recommend that accurate information be disseminated through education and communication by healthcare workers. Universities should have vibrant reproductive health clinics with a family planning unit. Also, in line with technological advancement, quality information about EC could be promulgated through audio-visual media, which has been found to be reliable and associated with good knowledge of EC. When good knowledge ultimately increases the uptake of EC, a reduction in unsafe abortion and its attendant morbidities and mortalities is inevitable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was self-sponsored, and we did not receive any funds from any organization. We thank the research assistants, including Mrs. Bidemi Oladapo, who assisted in data collection and entry, respectively. We are grateful to the female undergraduates who participated in this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

The study was conceived by OO, RT, and AA, and they all participated in the design, data analysis, and interpretation of the result. OO, AO, and AA were involved in data acquisition and writing of the draft manuscript as well as editing it per the suggestions of the co-authors. AO critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koyama A, Hagopian L, Linden J. Emerging options for emergency contraception. Clin Med Insights Reprod Heal. 2013;7(23):35. doi: 10.4137/CMRH.S8145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kofuor E, Darteh M, Doku DT. Knowledge and usage of emergency contraceptives among university students in Ghana. J Community Health. 2016;41:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Envuladu EA, Anke VDK, Zwanikken P, Zoakah AI. Sexual and reproductive health challenges of adolescent males and females in some communities of Plateau State Nigeria. Int J Psychol Behav Sci. 2017;7(2):55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adimora DE, Akaneme IN, Aye EN. Peer pressure and home environment as predictors of disruptive and risky sexual behaviors of secondary school adolescents. Afr Health Sci. 2018;18(2):218–226. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ilika A, Anthony I. Unintended Pregnancy among unmarried adolescents and young women in Anambra State, South East Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health. 2004;8(3):92–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salami KK, Ayegboyin M, Adedeji IA. Unmet social needs and teenage pregnancy in Ogbomosho, South-western Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14(4):959–966. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v14i4.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezegwui HU, Ikeako LC, Ogbuefi F. Obstetric outcome of teenage pregnancies at a tertiary hospital in Enugu, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2012;15(2):147–150. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.97289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartfai G. Emergency contraception in clinical practice: global perspectives. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2000;70:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idonije BO, Oluba OM, Otamere HO. A study on knowledge, attitude and practice of contraception among secondary school students in Ekpoma, Nigeria. J Chem Pharm Sci. 2011;2(2):22–27. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orji EO, Adegbenro CA, Olalekan AW. Prevalence of sexual activity and family-planning use among undergraduates in Southwest Nigeria. Eur J Contracept Reprod Heal Care. 2005;10(4):255–260. doi: 10.1080/13625180500331259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria], ICF Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2018. 2019.

- 12.Fasanu A, Adekanle D, Adeniji A, Akindele R. Emergency contraception: knowledge and practices of tertiary students in Osun State, South Western Nigeria. Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;4(1):doi: 10.4172/2161-0932.1000196. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasier A. Emergency contraception. Br Med Bull. 2000;56(3):729–738. doi: 10.1258/0007142001903319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajayi AI, Nwokocha EE, Akpan W, Adeniyi OV. Use of non-emergency contraceptive pills and concoctions as emergency contraception among Nigerian University students: results of a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1046):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3707-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ashoka PW, Stalderb C, Wagaarachchia PT, et. al. A randomised study comparing a low dose of mifepristone and the Yuzpe regimen for emergency contraception. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2002;109:553–560. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nworah JAO, Sunday UM, Joseph OU, Monday OO. Knowledge, attitude and practice of emergency contraception among students in tertiary schools in Anambra State Southeast Nigeria. Int J Med Med Sci. 2010;2(1):001–004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aziken MiE, Okonta PI, Ande ABA. Knowledge and Perception of Emergency Contraception Among Female Nigerian Undergraduates. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2003;29(2):84–87. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.084.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Addo VN, Tagoe-darko ED. Knowledge, practices, and attitudes regarding emergency contraception among students at a university in Ghana. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;105:206–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tilahun De, Assefa T, Belachew T. Predictors of emergency contraceptive use among Regular Female Students at Adama University, Central Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2010;7(16):1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kongnyuy EJ, Ngassa P, Fomulu N, et al. A survey of knowledge, attitudes and practice of emergency contraception among university students in Cameroon. BMC Emerg Med. 2007;7(7) doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nibabe WT, Mgutshini T. Emergency contraception amongst female college students knowledge, attitude and practice. African J Prim Heal Care Fam Med. 2014;6(1):Art. #538. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v6i1.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harper CC, Minnis AM, Padian NS. Sexual partners and use of emergency contraception. Am Coll Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1093–1099. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00544-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wright RL, Fawson PR, Frost CJ, Turok DK. U.S. Men's Perceptions and Experiences of Emergency Contraceptives. Am J Mens Health. 2017;11(3):469–478. doi: 10.1177/1557988315595857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]