Abstract

Objective

To perform a review evaluating management of and complications stemming from dog bite trauma sustained to the head and neck over the past decade.

Data Sources

PubMed and Cochrane Library.

Methods

The authors searched the PubMed and Cochrane Library databases for relevant published literature. A total of 12 peer‐reviewed canine‐exclusive series inclusive of 1384 patient cases describing facial dog bite trauma met inclusion criteria. Wounds including fractures, lacerations, contusions, and other soft‐tissue injuries were evaluated. Demographics related to clinical course and management, operating room requirements, and antibiotic usage were compiled and analyzed. Initial trauma and surgical management complications were also assessed.

Results

75.5% of patients sustaining dog bites required surgical intervention. Of these patients, 7.8% suffered from postsurgical complications, including hypertrophic scarring (4.3%), postoperative infection (0.8%), or nerve deficits and persistent paresthesias (0.8%). Prophylactic antibiotics were administered to 44.3% of patients treated for facial dog bites and the overall infection rate was 5.6%. Concomitant fracture was present in 1.0% of patients.

Conclusion

Primary closure, often in the OR may be necessary, with few cases requiring grafts or flaps. Surgeons should be aware that the most common complication is hypertrophic scarring. Further research is needed to elucidate the role of prophylactic antibiotics.

Keywords: bite, canine, dog, face, facial, injury, laceration, trauma

INTRODUCTION

Traumatic facial injuries from mammalian bites are most commonly caused by canines, with dog bites accounting for nearly 90% of all animal bites presented to emergency departments. 1 Over recent decades, notable increases in traumatic facial injuries due to animal bites have been observed across the United States, a probable consequence of rises in the domestic animal ownership. In investigating the incidence of animal bites in the United States over the years, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reported an 86% increase in hospitalizations due to dog bites alone from 1993 to 2008. 2 The rise in dog ownership has been estimated to confer a 50% lifetime risk of being bitten by a dog, and therefore presents a significant public health concern. 1

Although dog bites are rarely fatal, the injuries they incite often require significant surgical reconstruction and revision operations. Unfortunately, these injuries commonly result in permanent facial scarring and also pose a risk for both local and systemic infections, including brain abscesses, and rabies transmission. 3 , 4 , 5 The risk of rabies infection following exposure to a rabid animal is about 15%, however, a bite injury to the head and facial region carries a higher risk of transmission. 6 Previous studies have demonstrated the need for reconstructive surgery and scar revisions for these injuries in 77% of patients. 7 In 2014 alone, over 28,000 reconstructive surgical procedures were performed due to dog bites. 8 Despite their increasing prevalence and subsequent morbidity, the management of facial dog bites remains controversial, particularly in regard to the role of primary closure and the necessity of prophylactic antibiotic administration. Due to the significant morbidity and controversy surrounding the management of facial dog bite injuries, our objective was to perform a systematic review of the literature evaluating current surgical and medical management in patients presenting with facial dog bite injuries.

METHODS

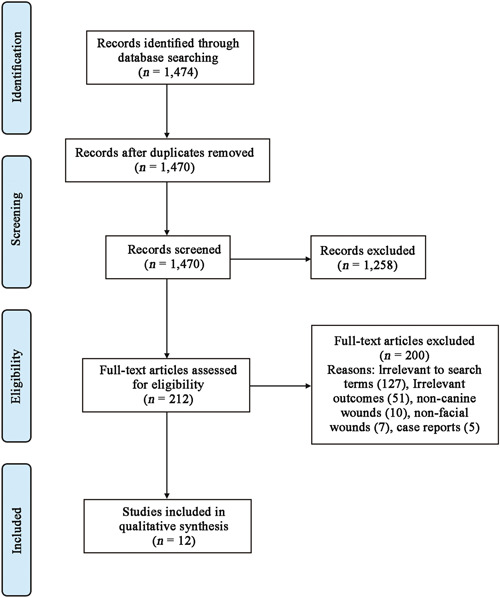

The Preferred Reporting Systems for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were followed for this systematic review. A comprehensive search of PubMed/MEDLINE and Cochrane Library was conducted with the search term: ((dog OR canine) AND (bite OR trauma OR injury OR laceration)) AND (face OR facial OR head). Figure 1 illustrates the search strategy and inclusion process used for this evidence‐based review. Exclusion criteria included articles older than 10 years, inability to extract dog‐specific injuries, non‐English, nonfacial trauma, examining outcomes on nonhuman populations, and without full text availability. Articles published over 10 years ago were excluded to include only the most recent material on the topic and highlight only current management practices. A total of 12 peer‐reviewed canine‐exclusive series encompassing 1384 patients from July 2010 to July 2020 met inclusion criteria and were comprehensively reviewed by two independent reviewers (T. C. and M. K.) with conflicts resolved by the senior author (P. F. S). Retrospective analyses, prospective randomized trials and studies, and case series were among the included study designs.

Figure 1.

Search method

All studies were assessed for the grade of evidence and any risk of bias via the MINORS criteria (Table 1). MINORS scores are calculated based upon credibility criteria, one of which pertains to unbiased assessment, that evaluate the methodological quality of studies, and has been externally validated according to the standards of high‐quality trials. 9 The items were scored 0 if not reported, 1 when reported but inadequate, and 2 when reported and adequate. A score of 16 is given to an ideal noncomparative study and 24 to a comparative study.

Table 1.

MINORS score

| Study | A clearly stated aim | Inclusion of consecutive patients | Prospective collection of data | Endpoints appropriate to aim of the study | Unbiased assessment of the study endpoint | Follow‐up period appropriate to study aim | Loss to follow‐up of less than 5% | Prospective calculation of the study size | Adequate control group* | Contemporary groups* | Baseline equivalence of groups* | Adequate statistical analyses* | MINORS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. 18 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 14 |

| Macedo et al. 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 12 |

| Mannion et al. 12 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 8 |

| Foster and Hudson 17 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 12 |

| Toure et al. 11 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 10 |

| Eppley and Schleich 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 14 |

| O'Brien et al. 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 10 |

| Gurunluoglu et al. 14 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 10 |

| Wei et al. 19 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 8 |

| Kumar et al. 13 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 8 |

| Paschos et al. 15 , a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 22 |

| Rui‐feng et al. 16 , a | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 20 |

Randomized control trial (RCT).

Injuries including fractures, lacerations, contusions, and other soft‐tissue injuries were evaluated as primary outcomes of focus. Data were collected on demographics, clinical course and management, surgical requirements, and antibiotic usage as secondary outcomes of focus.

RESULTS

In total, 1384 patients with dog bite injuries from 2 Randomized control trials, 3 prospective case series, and 7 retrospective case series were included in this systematic review. The overall quality of articles was determined to be low as a majority of articles did not meet the ideal MINORS score (Table 1). Analysis of the reported patient population revealed that 49.7% of victims were male and 50.3% of victims were female (Table 2). The average age of injured victims was 13.9 years.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with dog bite injuries

| Study | Number of patients | Age range | Mean age (years) | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. 18 | 87 | 9 months to 17 years | ‐ | 41 | 46 |

| Rui‐feng et al. 16 | 600 | 1–64 years old | ‐ | 272 | 328 |

| Macedo et al. 10 | 146 | 1–12 years old | 7 | 88 | 58 |

| Mannion et al. 12 | 65 | 1–71 years old | 22 | 37 | 28 |

| Foster and Hudson 17 | 20 | 8 months to 66 years old | ‐ | 9 | 11 |

| Toure et al. 11 | 108 | <2–70 years old | ‐ | 49 | 59 |

| Eppley and Schleich 3 | 107 | 6 weeks to 11.5 years old | ‐ | 56 | 51 |

| O'Brien et al. 7 | 101 | 11 months to 73 years old | 15.1 ± 18.1 | 47 | 53 |

| Gurunluoglu et al. 14 | 75 | ‐ | 46 children = 6.8, 27 adults = 47.3 | 45 | 30 |

| Wei et al. 19 | 17 | 6 months to 10 years old | 3.9 ± 3.2 | 8 | 9 |

| Paschos et al.15 | 41 | ‐ | ‐ | 27 | 14 |

| Kumar et al. 13 | 17 | ‐ | 2.5 | 9 | 8 |

All reviewed articles included descriptions of dog bite injuries to the head and neck. The particular area injured was specified in 5 of the 12 articles reviewed (Table 3). Areas of head and neck injury included the scalp, nose, lips, ear, eyelids, cheek, forehead, neck, and chin. In studies that specified the location of the patient's injuries, the lip was the area of the face most commonly injured, accounting for 23.0% of injuries. The second most commonly injured site was the cheek, which was injured in 19.0% of cases. Intraoral lacerations, temple, eye, and cheekbone injuries were the least common, occurring in only three patients each (0.5%).

Table 3.

Topographical distribution of injuries

| Study | Scalp | Nose | Lip | Ear | Periorbital | Cheek | Forehead | Neck | Intraoral | Chin | Temple |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macedo et al. 10 | 39 | 15 | 13 | 9 | 5 | 44 | 21 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Mannion et al. 12 | 2 | 18 | 32 | 5 | 6 | 18 | 1 | 2 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Foster and Hudson 17 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 3 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Toure et al. 11 | ‐ | 25 | 69 | 23 | 41 | 78 | 32 | 2 | ‐ | 10 | 7 |

| Gurunluoglu et al. 14 | 4 | 14 | 28 | 5 | 6 | 24 | 7 | ‐ | ‐ | 10 | ‐ |

| Overall | 47 | 80 | 152 | 45 | 61 | 173 | 64 | 9 | 3 | 20 | 7 |

Analysis of the 678 patients with reported data on the need for surgical repair (Table 4) revealed that 75.5% of patients sustaining facial dog bites underwent surgical intervention in the operating room for proper wound repair. 7.8% of patients suffered from reported postoperative complications, including hypertrophic scarring, postoperative wound infections, and persistent neurological deficits or paresthesia. Evaluation of the complications revealed that hypertrophic scarring was the most common complication following surgery, occurring in 4.3% of injuries. Postoperative infections were noted in 0.8% of patients. Approximately 0.8% of patients suffered persistent neurological deficits and persistent paresthesias after their procedures. 19.1% of patients required revision surgery. Flaps were used in 0.1% of patients who underwent surgery. 10.4% of patients required grafting.

Table 4.

Surgical management and complications

| Study | Total number of cases | Number of surgeries | Postsurgical complications | Revision surgery | Cases using flaps | Cases using grafting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foster and Hudson 17 | 20 | 9 | Hypertrophic scarring (2), persistent paresthesia in V2 (1) | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Toure et al. 11 | 108 | 120 | Hypertrophic scarring (10), suppuration (6), necrosis (2), scar flange (2), | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| O'Brien et al. 7 | 101 | 10 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gurunluoglu et al. 14 | 75 | 40 | Hypertrophic scarring (2), postoperative wound infection (1) | 17 | 25 | 10 |

| Wei et al. 19 | 17 | 14 | Postoperative wound infection (2), prominent scarring, ptosis or epiphora (6) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kumar et al. 13 | 17 | 22 | Neurological deficits (3) | ‐ | ‐ | 1 |

| Macedo et al. 10 | 146 | 146 | ‐ | ‐ | 6 | 38 |

| Eppley and Schleich 3 | 107 | 107 | Postoperative wound infection (1) | 79 | 0 | 4 |

| Wu et al. 18 | 87 | 44 | Hypertrophic scarring (2) | 0 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Total | 678 | 512 | Hypertrophic scarring (16), postoperative wound infection (4), prominent scarring, ptosis or epiphora (6), suppuration (6), neurological deficits (3), scar flange (2), necrosis (2), persistent paresthesia in V2 (1) | 98 | 34 | 53 |

Fractures were a rare occurrence in the patient population being evaluated, present in only 1.0% of patients included in this study (Table 5). A significant portion of these noted fractures can be attributed to the inclusion criteria of the reports by Wei et al. 19 who only reviewed patients who sustained facial fractures from dog bites. Another significant elevation to data on fractures was from Kumar et al. 13 who evaluated a series of dog bite injuries that required neurosurgical consultation. These injuries often involved depressed skull fractures, and therefore could be classified as being more severe overall.

Table 5.

Incidence of concomitant fractures (%)

Wound infections were reported throughout the course of management in 5.6% of total cases, which was reported independently of prophylactic antibiotic use (Table 6).

Table 6.

Infection rate

| Study | Total number | Number infected | Infection rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. 18 | Not specified | ‐ | |

| Rui‐feng et al. 16 | 600 | 50 | 8.3% |

| Macedo et al. 10 | 146 | 0 | 0% |

| Mannion et al. 12 | Not specified | ‐ | |

| Foster and Hudson 17 | 20 | 0 | 0% |

| Toure et al. 11 | Not specified | ‐ | |

| Eppley and Schleich 3 | 107 | 1 | 0.9% |

| O'Brien et al. 7 | Not specified | ‐ | |

| Gurunluoglu et al. 14 | 75 | 1 | 1.3% |

| Wei et al. 19 | 17 | 2 | 11.7% |

| Paschos et al. 15 | 41 | 3.4 | 8.3% |

| Kumar et al. 13 | 17 | 1 | 5.9% |

| Overall | 1,023 | 57.7 | 5.6% |

Prophylactic antibiotics were administered to 45.4% of patients presenting for management of facial dog bites (Table 7). In studies that administered antibiotics, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was the most commonly used in studies where specific antibiotics were reported, being administered to 98.7% of patients. This was a common choice due to its broad coverage of infections caused by canines or human flora.

Table 7 .

Prophylactic antibiotic choice

| Study | Number of patients given amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | Number of patients given TMP/SMX and clindamycin | Number of patients given cephalexin | Number of patients given ampicillin/sulbactam |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu et al. 18 | 85 | 1 | 1 | ‐ |

| Foster and Hudson 17 | 15 (outpatient) | ‐ | ‐ | 15 (inpatient) |

| Paschos et al. 15 | 41 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Kumar et al. 13 | 16 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

DISCUSSION

Epidemiology

There have been many epidemiological studies that have been performed on this subject and the general consensus is that children are at the greatest risk for facial dog bite trauma. 10 This correlation is generally attributed to the shorter stature of children, lack of experience in recognizing warning signs of an imminent dog attack, and lack of ability to defend against an attack. 10 , 11 Children are also more likely to interact with dogs closely and in ways such as petting and hugging, and as a result, placing their faces in closer proximity to animals. 11 , 12 , 13 In our systematic review, the calculated mean age of patients in studies providing detailed information about age was 13.9 years of age, with 49.7% male and 50.2% female, reflecting the approximately equal prevalence found in many studies. To date, a consensus has been reached on the identified risk factors of pediatric age as well as a few specific breeds of dogs, which was not the focus of this review. Touré et al. 11 2015 uniquely identified that children from single‐parent households may be at increased risk due to the nature of shared custody and the more relative lack of supervision of a single parent compared to two.

The role of antibiotic prophylaxis

An ongoing point of contention in facial dog bite management is the role of antibiotic prophylaxis. 14 The risk of infection associated with the mixture of anaerobic and aerobic pathogens introduced into dog bite wounds from both the offending animal and the skin flora of the victim has been variably described in several papers. Some authors have previously argued that the main risk for infection is mitigated with thorough cleaning and debridement and the rich vascularity of the face and neck, negating the need for prophylactic antibiotic administration. 15 In this review, 45.4% of the patients received antibiotics prophylactically.

According to the 2014 Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines, the preemptive antibiotic of choice is amoxicillin/clavulanic acid for 3–5 days to cover for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria for specific populations, including moderate to severe injuries to the hand or face. Unfortunately, most studies in this review did not specify the duration of administration. However, in the studies with specified antibiotic administration, 157 out of 159 patients receiving prophylactic antibiotics were given amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Other alternatives included TMP/SMX and clindamycin, cephalexin, ampicillin/sulbactam. In one study, the 600 patients were not given prophylactic antibiotics and the reported infection rate was 8.3%. 16 Of the studies that did provide antibiotics, the highest infection rate was reported in Paschos et al. 15 where the infection rate was 8.3% as well. The overall infection rate of studies in our review that did give prophylactic antibiotics was 2.0%, indicating that there may be some clinical benefit in the use of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Surgical management

Along the same lines, the debate between primary and delayed closure had been unclear until recently. Primary closure methods employed in the management of facial dog bite injuries involve direct sutures of the wound, grafting, or local flaps. Several authors argue that the benefit of primary closure is that it not only minimizes the consequences of infection and significant aesthetic damage or scarring, but also circumvents the regular dressings, analgesics, and maintenance of wounds that delayed closure requires. Further variability exists in the data on the relationship between primary closure and infection occurrence, with earlier studies showing an increased rate of infection associated with primary closure of wounds, and more recent studies showing no relationship between the two. 15 Recently, management has favored primary closure as there had been some literature that suggested that infection rates were not higher with this method. 17 , 18

In this systematic review, most patients received treatment with primary closure and the infection rate was at a low 1.0%, reaffirming that the trend toward primary closure has not been drastically increasing infection rates. Two studies reviewed looked specifically at the rates of infection and outcomes between primary and delayed closure. In the first, Rui‐feng et al. 16 compared the outcomes of 600 patients randomized into two groups of primary and delayed closure. Antibiotics were only administered if there were signs of infection, however, the number of patients that received antibiotics was not specified. There was no statistical difference in infection rate between the two groups but results showed better cosmesis and faster recovery with primary closure. The study specifically emphasized the role of thorough cleaning, disinfection with 0.05% iodophors, and debridement of the wound before primary closure in keeping infection rates low. Similarly, the second study, Paschos et al. 15 studied 41 patients with head and neck injuries randomized into sutured and nonsutured groups, with all patients from both groups receiving prophylactic amoxicillin and clavulanic acid. There was no difference in infection rates between the two groups.

Complications

Out of the 678 patients in the studies reporting on surgical outcomes, 512 (75.5%) underwent surgery. Out of those surgeries, 17.0% required procedures beyond simple debridement and primary closure, with 34 cases that required flaps and 53 cases that required grafting. Therefore, the likelihood of requiring more complex reconstructive techniques is moderate. In addition, the rate of hypertrophic scarring as the most common complication was calculated to be 4.3%, occurring in 16 cases. There were 23 revision surgeries that were performed, indicating that it may be useful for surgeons to take steps to minimize any risk factors that increase the incidence of hypertrophic scarring in the initial surgery. These are important factors to discuss with patients as part of a comprehensive preoperative informed consent process.

Fracture risk

The rate of concomitant fracture with initial trauma across the 12 studies in this review was calculated to be 1.0%. Most studies did not discuss or emphasize the use of computed tomography scans in detecting fractures in facial dog bite injuries except in cases of severe injury, 19 which may possibly be attributed to simple lack of reporting or to the rarity of co‐occurrence.

Site of injury

There is some variability in the literature on what area of the face is most likely to be affected. 10 , 11 , 12 , 14 , 17 Out of 1384 patients, our calculations revealed that the lip was the most commonly affected area in 152 (23.0%) cases. The cheek was injured in 126 (19.1%) cases and the nose was injured in 80 (12.1%) cases. Fifty eight (8.0%) cases involved the eyelid and periorbital area, indicating that ophthalmological consultation is relatively likely to be needed in the management of these injuries.

Limitations

This study shares limitations common among all systematic reviews. A relatively limited number of databases were included in identifying potentially eligible studies available in a full‐text to the reviewers. The references included were biased towards ones that included the search term ((dog OR canine) AND (bite OR trauma OR injury OR laceration)) AND (face OR facial OR head) and upon review, included data on dog‐specific injuries to human victims. The search results may thus represent a small cross‐section of the literature that could potentially exist on the topic due to the selected inclusion criteria and search term. The results were further filtered to include only studies published within the last 10 years and available in English, which may have introduced further selection bias. The resultant studies were heterogeneous in their study designs, methods of dog bite management described, and reporting of data, which limited the methods of management of dog bite trauma that we could effectively analyze. Associated maxillofacial bony injuries were not reported universally among included studies, which limits the authors' analysis of the extent of facial dog bite trauma. Furthermore, the duration of antibiotic treatment was rarely reported in the reviewed data, which may pose a difficulty to clinicians wishing to judiciously prescribe antibiotics and avoid complications of over‐treatment. Despite the aforementioned limitations, this review, including 1384 patients, is the first systematic review of our knowledge of the surgical and medical management of facial dog bite trauma synthesized within the last decade.

CONCLUSIONS

Dog bite injuries often occur in the face, head, and neck, and therefore are important for otolaryngologists and facial plastic surgeons to understand. In the approach of facial dog bite management, surgical repair is necessary in many cases, predominantly via primary closure, with few cases requiring grafts or flaps. Surgeons should be aware that the most common complication is hypertrophic scarring, and the risk of concomitant fracture is low. The administration of prophylactic antibiotics demonstrated clinical benefit in this review, but this field of research lacks high‐quality studies such as randomized control trials, therefore future research is suggested to support our findings and reduce confounding factors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Tiffany Chen: Data collection; manuscript writing and editing; table and figure design. Maria Karim: Data collection; manuscript writing and editing; table and figure design. Zachary T. Grace: Manuscript writing and editing. Andrew R. Magdich: Manuscript writing and editing. Eric C. Carniol: Manuscript editing. Brian E. Benson: Manuscript editing. Peter F. Svider: Data collection; manuscript writing and editing; table and figure design.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

IRB approval was not needed due to lack of primary patient data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are no acknowledgments and fundings.

Chen T, Karim M, Grace ZT, et al. Surgical management of facial dog bite trauma: a contemporary perspective and review. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;9:123‐130. 10.1002/wjo2.75

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available upon reasonable request of authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hon KL, Fu CC, Chor CM, et al. Issues associated with dog bite injuries in children and adolescents assessed at the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:445‐449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Department of Health and Human Services . Hospital admissions for dog bites increase 86% over a 16‐year period. Accessed November 20, 2020. http://archive.ahrq.gov/news/newsroom/news-and-numbers/120110.html

- 3. Eppley BL, Schleich AR. Facial dog bite injuries in children: treatment and outcome assessment. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:384‐386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Santana‐Montero BL, Ahumada‐Mendoza H, Vaca‐Ruíz MA, et al. Cerebellar abscesses caused by dog bite: a case report. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:1137‐1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klein DM, Cohen ME. Pasteurella multocida brain abscess following perforating cranial dog bite. J Pediatr. 1978;92:588‐589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Di Quinzio M, McCarthy A. Rabies risk among travellers. Can Med Assoc J. 2008;178:567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Brien DC, Andre TB, Robinson AD, Squires LD, Tollefson TT. Dog bites of the head and neck: an evaluation of a common pediatric trauma and associated treatment. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36:32‐38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2014. Plastic surgery statistic report. 2014. Accessed November 20, 2020. www.plasticsurgery.org

- 9. Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non‐randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712‐716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Macedo JL, Rosa SC, Queiroz MN, Gomes TG. Reconstruction of face and scalp after dog bites in children. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2016;43:452‐457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Touré G, Angoulangouli G, Méningaud JP. Epidemiology and classification of dog bite injuries to the face: a prospective study of 108 patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2015;68:654‐658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mannion CJ, Graham A, Shepherd K, Greenberg D. Dog bites and maxillofacial surgery: what can we do? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53:522‐525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kumar R, Deleyiannis FW, Wilkinson C, O'Neill BR. Neurosurgical sequelae of domestic dog attacks in children. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2017;19:24‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gurunluoglu R, Glasgow M, Arton J, Bronsert M. Retrospective analysis of facial dog bite injuries at a level I trauma center in the Denver metro area. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76:1294‐1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paschos NK, Makris EA, Gantsos A, Georgoulis AD. Primary closure versus non‐closure of dog bite wounds. a randomised controlled trial. Injury. 2014;45:237‐240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rui‐feng C, Li‐song H, Ji‐bo Z, Li‐qiu W. Emergency treatment on facial laceration of dog bite wounds with immediate primary closure: a prospective randomized trial study. BMC Emerg Med. 2013;13:1‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Foster MD, Hudson JW. Contemporary update on the treatment of dog bite: injuries to the oral and maxillofacial region. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73:935‐942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu PS, Beres A, Tashjian DB, Moriarty KP. Primary repair of facial dog bite injuries in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27:801‐803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wei LA, Chen HH, Hink EM, Durairaj VD. Pediatric facial fractures from dog bites. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;29:179‐182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request of authors.