Abstract

Background

Diversity in orthopedics is lacking despite ongoing efforts to create a more inclusive workforce. Increasing diversity necessitates recruitment and retainment of underrepresented providers, which involves representation among leadership, mentorship initiatives, and development of a safe work environment. Discrimination and harassment behaviors are prevalent within orthopedics. Current initiatives aim to address these behaviors among peers and supervising physicians, but patients are an additional underrecognized source of these negative workplace behaviors. This report aims to establish the prevalence of patient-initiated discrimination and harassment within a single academic orthopedic department and establish methods to reduce these behaviors in the workplace.

Methods

An internet-based survey was designed using the Qualtrics platform. The survey was distributed to all employees of a single academic orthopedic department including nursing staff, clerks, advanced practice providers, research staff, residents/fellows, and staff physicians. Survey was distributed on two occasions between May and June of 2021. The survey collected information on respondent demographics, experience with patient-initiated discrimination/harassment, and opinions regarding possible intervention methods. Fisher exact test was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Over one half of survey respondents report observing or personally experiencing patient-initiated discrimination within our orthopedics department (57%, n=110). Nearly half of respondents report observing or personally experiencing patient-initiated harassment within our department (46%, n=80). Encounters with these behaviors were more commonly reported from resident and staff female physicians. The most frequently reported negative patient-initiated behaviors include gender discrimination and sexual harassment. Discordance exists regarding optimal methods to address these behaviors, but one third of respondents indicate potential benefit from visual aids throughout the department.

Conclusion

Discrimination and harassment behaviors is common within orthopedics, and patients are a significant source of this negative workplace behavior. Identification of this subset of negative behaviors will allow us to provide patient education and provider response tools for the protection of orthopedic staff members. Ideally, minimizing discrimination/harassment behaviors within our field will help create a more inclusive workplace environment and allow continued recruitment of diverse candidates into our field.

Level of Evidence: V

Keywords: diversity

Introduction

Diversity is imperative in healthcare as increased gender, ethnic, and cultural representation among providers affords benefits to patient care, minimizes healthcare disparities, and enhances the educational value of training programs.1-4 Despite ongoing efforts to create a more diverse workforce, orthopedic surgery remains the least gender diverse of the surgical subspecialties (females represent only 15% of current trainees—lower than both neurosurgery at 17.5% and urology at 25%).5 Orthopedics also lacks minority representation, in view of the fact that Black/African American and Hispanic providers represent only 4.0% and 5.6% of the orthopedic workforce, respectively.6 Perhaps unsurprisingly, these trends are reflected in that the first Black/African American and female presidents of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) were only appointed in 2008 and 2019. Increasing diversity necessitates recruitment and retainment of providers from underrepresented backgrounds, and orthopedic initiatives including the Ruth Jackson Orthopedic Society (RJOS), The Perry Initiative, and J. Robert Gladden Orthopaedic Society (JRGOS) aim to address these disparities. Establishing diversity among physicians both in mentorship and leadership positions is critical, and lack of female and ethnic underrepresented minority (URM) mentors are potential deterrents to choosing orthopedics as a specialty.7,8

In addition to mentorship resources, work environment can largely factor into specialty choice and an unwelcoming workplace creates an additional barrier to successful recruitment of diverse applicants. Discrimination, which involves differential treatment of an individual based on characteristics such as gender, race, religion, or sexual orientation; and harassment, which involves unwelcome conduct toward an individual based on these same factors, can both contribute to a negative workplace environment. Ongoing efforts exist to reduce discrimination and harassment within orthopedics. However, while much of the current discussion involves addressing negative behaviors from peers and supervising physicians, 43% of respondents in a survey by Whicker et al. noted patients as a source of workplace harassment.9 Raising awareness and implementing procedures to address patient-initiated discrimination and harassment behaviors should be included in efforts to address workplace safety and inclusivity. This study aims to establish and analyze the prevalence of patient-initiated discrimination and harassment within a single academic orthopedic department and explore methods to reduce these behaviors in the workplace.

Methods

This study does not meet the regulatory definition of human subject research under institutional IRB and therefore did not require IRB review. An internet-based survey was constructed using Qualtrics XM. Demographic data including age, department role, gender, and race was collected. Survey contents include questions addressing situations of discrimination and harassment, questions regarding training and techniques for responding to discrimination and harassment, and a narrative section to share examples of personal experience. A definition of “harassment” and “discrimination” was provided at the beginning of the survey. In this survey, discrimination was defined as ‘differential treatment of an individual or group of people based on their race, color, national origin, religion, sex, age, disability, sexual orientation, or genetic information’, and harassment was defined as ‘unwanted conduct toward an individual based on these characteristics’. Responses to survey questions include “yes/no” (binary), “Likert scale”, multiple choice, matrix questions and free-response questions.

The survey was distributed via email to all 359 orthopedic staff members at a single institution between May and June of 2021. Staff members of the orthopedics department include Clerks, Nurses, Advanced Practice Providers, Residents, Fellows, Researchers and Attending Physicians. The survey was sent in two instances separated by 10 days for non-respondents. Response collection and data analysis was performed using Qualtrics XM. Descriptive statistics (means, medians, percentages, standard deviations, and inter-quartile ranges) were computed for all variables. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

A total of 173 survey responses were submitted representing a 48% response rate. Resident and staff physicians comprised 35% of respondents (n=49), in addition to advanced practice providers, nurses, medical assistants, administrative staff, athletic training, and research staff. Respondents were 65% female (n=89), and 93% of respondents self-identify as White (n=128). Overall, over half of survey respondents reported observing or personally experiencing patient-initiated discrimination within our orthopedics department (57%, n=110). The most frequent types of patient-initiated discrimination encountered include gender/identity based (37%, n=43) and race/ ethnicity-based behaviors (33.6%, n=39). 46% (n=80) of respondents reported observing or personally experiencing patient-initiated harassment within our department. The most frequent types of harassment encountered were gender/identity based (n=22, 25.6%), sexual harassment (n=19, 22.1%), and race/ethnicity based (n=10, 11.63%). Among clinical respondents (resident/staff physicians, advanced practice providers, nursing staff, medical assistants), 25% (n=25) and 39% (n=39) report experiencing or observing patient-initiated discrimination, and 33% (n=32) and 26% (n=25) report experiencing or observing patient-initiated harassment. Comparatively, approximately 2/3 of non-clinical staff respondents (administrative/clerical, research), have never encountered these behaviors in the workplace (62%, n=36 and 75%, n=43).

Over half of survey respondents indicate patient-initiated discrimination and harassment has contributed to personal burnout, and between 40-60% of participants cite negative effects on job satisfaction and patient care (Figure 1, A and B). Among respondents that chose not to report these events (91%, n=40) reasons for not reporting include not knowing whether the incident was severe enough to report (24%), assumptions that nothing would be done in response to the report (19%), fear of negative professional consequence (15%), and not knowing how to report the event (13%).

Figure 1A to 1B.

Effect of Patient-Initiated Discrimination (1A) and Harassment (1B) on job satisfaction, quality of patient care, personal risk of burnout, and relationship with peers. Unlabeled portions of bar graph represent <5% of responses.

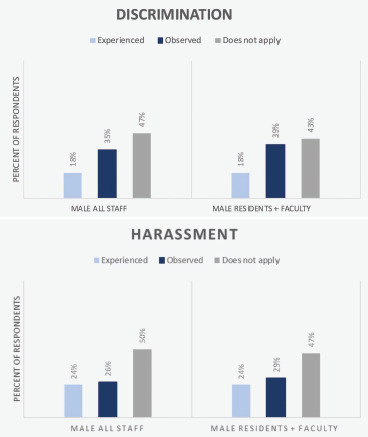

When analyzed by gender and job classification of respondents, results showed that of all female orthopedic staff, 34% (n=36) report having observed patient-initiated discrimination, and 23% (n=24) report having experienced this type of behavior. In an analysis of a subgroup of female staff including only female residents and faculty, 29% and 50% (n=7, n=4) of respondents report having observed or experienced patient-initiated discrimination respectively. Similarly, 17% (n=17) and 27% (n=27) of female all staff respondents report having observed or experienced patient-initiated harassment, compared to 31% and 46% (n=10, n=13) of female resident/staff respondents (Figure 2a). Of all male orthopedic staff, 35% report having observed patient-initiated discrimination (n=17), and 18% (n=9) report having experienced this type of behavior, while 26% (n=13) and 24% (n=12) report having observed and experienced patient-initiated harassment. Subgroup analysis of male staff including only male residents and faculty demonstrated similar results to the all-staff group (Figure 2b).

Figure 2A.

Percentage of female staff and female residents/faculty that report personally experiencing or observing patient-initiated discrimination (A) and harassment (B) behaviors within our department.

Figure 2B.

Percentage of male staff and male residents/faculty that report personally experiencing or observing patient-initiated discrimination(A) and harassment(B) behaviors within our department.

Participants were surveyed regarding potential learning tools to reduce the frequency of patient-initiated discrimination and harassment in our department. While discordance exists regarding optimal methods to address discrimination/harassment behaviors, 33% of respondents indicate potential benefit from implementing visual aids (posters/signs) throughout the department, 32% feel that online trainings might be beneficial, and 22% of respondents answered that didactic materials, such as lectures, would help address this issue. Regarding the utility of visual aids throughout the department, 55% of participants feel this intervention would “likely” or “very likely” reduce the frequency of patient-initiated negative workplace behaviors (Figure 3).

Figure 3A to 3B.

(3A) Percent of survey responses indicating which types of learning tools are likely to aid in reducing discrimination and harassment behaviors, (3B). Percent of survey responses indicating likelihood that visual or didactic based training can aid in reducing discrimination and harassment behaviors.

Discussion

Lack of existing gender, racial, and cultural diversity among practicing orthopedists is both a detriment to patient care and a barrier to successful recruitment of diverse orthopedic providers. Promoting diversity in orthopedics involves creating an inclusive work environment, but a 2020 survey by Samora et al. highlights the ubiquity of negative workplace behaviors such as discrimination, sexual harassment, and bullying in Orthopaedics. Nearly 4 of 5 female and Black/African American AAOS member respondents report having personally experienced these behaviors in the workplace, while a separate survey notes a staggering 68% of female trainees report experiencing episodes of sexual harassment during their residency training.9,10

Despite slow progress, representation in orthopedics is increasing. The current 15% of female trainees represents a significant improvement and nearly a 30% increase from only 11.6% female trainees a decade prior,8 likely due to both increased recruitment efforts and improvements in overall workplace culture. As an unwelcoming workplace can deter underrepresented candidates from pursing orthopedics, current initiatives such as #SpeakUpOrtho help prompt discussion that drives necessary change to minimize these behaviors from fellow resident and staff surgeons.11,12

Current literature seldom discusses other sources of these behaviors, but as demonstrated by the results of this survey, patients are a common and underrecognized source of workplace discrimination and harassment in orthopedics. Gender discrimination and sexual harassment were the most frequently reported behaviors in this study. Survey respondents in this study cite behaviors including verbal attacks, insulting comments, and unwanted sexual advances, among others (Table 1). Over half of respondents in this survey have encountered these behaviors from patients, and female resident/staff providers are twice as likely to report personal harassment from patients in comparison with the remainder of this cohort. While male providers report lower rates of patient-initiated discrimination and harassment than their female counterparts, they are not exempt from this behavior—nearly ¼ of male respondents in this survey also reported personal experience with discrimination and harassment. Unfortunately, assessment of race/ ethnicity related patient-initiated discrimination/harass-ment was limited in this study given lack of non-White survey respondents. Additionally, demographic information of non-respondents in this survey was not available and unrecognized response bias may therefore limit this report. Nonetheless, this report demonstrates the ubiquity of patient-initiated discrimination and harassment behaviors in the orthopedic workplace.

Table 1.

Narrative Responses of Personal Examples with Patient Initiated Discrimination and Harassment within our Department

| Frequently harassment happens on phone triage when a patient or family member is pushing for something and we can't do it. |

| Patients screaming and swearing at our staff over the telephone. |

| Because I'm female, some patients lessen my value as a part of the care team compared to my male coworkers. |

| Patients are sometimes ignorant when it comes to the diversity of our staff. |

| Patients questioning my competency as a female provider, making comments about my appearance. |

| Gender discrimination with or without sexual harassment - unwanted sexual advances or crude jokes. |

| Discrimination or harassment based on national origin, "I want a doctor I can understand, not this (pejorative ethnic or racial slur)" |

| Female trainees and staff are not treated with the same respect. |

| I have had multiple adult patients assume that I am the medical student/nurse/trainee and not the staff surgeon due to my gender |

| Patient phone calls are a frequent source of patient-initiated harassment. |

| On several occasions I witnessed patients treat an african american resident much differently than his caucasian colleagues. |

| Patients being very sexually inappropriate in their comments/gestures with our female APP and MD staff. |

Similar to prior literature demonstrating the ill effects of negative workplace behaviors on providers’ health and well-being,13 respondents of this survey indicate patient-initiated discrimination and harassment negatively affects workplace environment, particularly relating to burn out and job satisfaction. If unaddressed, repeated occurrences of these negative workplace behaviors can contribute to an unsustainable work environment.

Attempts should be made to minimize these behaviors in the workplace given implications on provider wellbeing and patient care, but limited solutions have been proposed. In this survey, discordance exists among respondents regarding optimal methods to address dis-crimination/harassment behaviors, although over half of respondents believe visual and/or didactic training techniques would reduce the amount of these behaviors experienced in our department. Visual aids such as posters or pamphlets throughout the department would be a simple intervention to ideally help elucidate the problem, deter inappropriate patient behavior, and provide potential response tools and accessible reporting mechanisms when these behaviors are encountered.

Overall, this survey demonstrates that patient-initiated discrimination and harassment behaviors is a frequent occurrence in our department, particularly among female resident and staff physicians. Identification of this subset of negative behaviors will allow us to develop patient education and provider response tools to minimize these behaviors, protect orthopedic staff members, and build a more inclusive orthopedic environment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Patrick Barlow for his assistance with the development of this survey.

References

- 1.Marrast LM, Zallman L, Woolhandler S, Bor DH, McCormick D. Minority physicians' role in the care of underserved patients: diversifying the physician workforce may be key in addressing health disparities. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(2):289–291. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, et al. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. Jama. 1999;282(6):583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitla DK, Orfield G, Silen W, Teperow C, Howard C, Reede J. Educational benefits of diversity in medical school: a survey of students. Acad Med. 2003;78(5):460–466. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200305000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Day MA, Owens JM, Caldwell LS. Breaking Barriers: A Brief Overview of Diversity in Orthopedic Surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 2019;39(1):1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Heest AE, Agel J, Samora JB. A 15-Year Report on the Uneven Distribution of Women in Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Training Programs in the United States. JB JS Open Access. 2021;6(2) doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.20.00157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emery SE. Diversity in Orthopaedic Surgery: International Perspectives: AOA Critical Issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(21):e113. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okike K, Phillips DP, Johnson WA, O'Connor MI. Orthopaedic Faculty, Resident Racial/Ethnic. Diversity is Associated With the Orthopaedic Application Rate Among Underrepresented Minority Medical Students. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(6):241–247. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Heest AE, Agel J. The uneven distribution of women in orthopaedic surgery resident training programs in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(2):e9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whicker E, Williams C, Kirchner G, Khalsa A, Mulcahey MK. What Proportion of Women Ortho-paedic Surgeons Report Having Been Sexually Harassed During Residency Training? A Survey Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478(11):2598–2606. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balch Samora J, Van Heest A, Weber K, Ross W, Huff T, Carter C. Harassment, Discrimination, and Bullying in Orthopaedics: A Work Environment and Culture Survey. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(24):e1097–e1104. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gianakos AL, Mulcahey MK, Weiss JM, et al. #SpeakUpOrtho: Narratives of Women in Orthopae-dic Surgery-Invited Manuscript. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30(8):369–376. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gianakos AL, LaPorte DM, Mulcahey MK, Weiss JM, Samora JB, Cannada LK. Dear Program Director: Solutions for Handling and Preventing Abusive Behaviors During Surgical Residency Training. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30(13):594–598. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-21-00630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halim UA, Riding DM. Systematic review of the prevalence, impact and mitigating strategies for bullying, undermining behaviour and harassment in the surgical workplace. Br J Surg. 2018;105(11):1390–1397. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]