Abstract

Background:

Children with prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) have significant social skills deficits and are often treated in community mental health settings. However, it remains unclear whether these children can be effectively treated using manualized, evidence-based interventions that have been designed for more general mental health populations.

Methods:

To shed light on this issue, the effectiveness of Children’s Friendship Training (CFT) versus Standard of Care (SOC) was assessed for 85 children ages 6 to 12 years with and without PAE in a community mental health center.

Results:

Children participating in CFT showed significantly improved knowledge of appropriate social skills, improved self-concept, and improvements in parent-reported social skills compared to children in the SOC condition. Moreover, results revealed that within the CFT condition, children with PAE performed as well as children without PAE. Findings indicated that CFT, an evidence-based social skills intervention, yielded greater gains than a community SOC social skills intervention and was equally effective for children with PAE as for those without PAE.

Conclusions:

Results suggest that children with PAE can benefit from treatments initiated in community settings in which therapists are trained to understand their unique developmental needs, and that they can be successfully integrated into treatment protocols that include children without PAE.

Keywords: Social Skills Training, Prenatal Alcohol Exposure, Community Mental Health Center

OVER THE PAST 30 years, mounting evidence has prompted increased attention to the role of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) in the occurrence of a wide range of disorders known as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASDs; Warren and Hewitt, 2009). Fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), one of the most severe conditions resulting from in utero alcohol exposure, is defined by a pattern of characteristic facial malformations, growth deficiencies, and neurodevelopmental deficits (Jones and Smith, 1973). A substantial body of research has documented significant neurocognitive difficulties among individuals with FAS as well as among individuals who have been prenatally exposed to alcohol but do not meet full criteria for FAS (Chasnoff et al., 2010; Guerri et al., 2009; Kodituwakku, 2009; McGee and Riley, 2007; O’Connor and Paley, 2009; Rasmussen, 2005; Rasmussen et al., 2006). This latter group of individuals may be described as having partial FAS (pFAS), alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder (ARND), or alcohol-related birth defects (ARBD) according to the diagnostic categories proposed by the Institute of Medicine (Hoyme et al., 2005; Stratton et al., 1996). The entire continuum of effects is estimated to represent up to 2 to 5% of the population of children born in the United States (May et al., 2009), suggesting that the effects of PAE are pervasive and represent a major public health concern.

Studies reveal that children with PAE have multiple developmental deficits including inattention, hyperactivity, poor language performance, as well as difficulties in memory and executive functioning (Astley, 2010; Chasnoff et al., 2010; Kodituwakku, 2009). Given the neurocognitive problems associated with PAE, it is not surprising that psychosocial dysfunction has been consistently noted in the literature. Longitudinal studies suggest that individuals with PAE are at a greatly increased risk for adverse long-term outcomes, including psychiatric disorders and poor social adjustment (O’Connor and Paley, 2009; O’Leary et al., 2009; Streissguth and O’Malley, 2000; Streissguth et al., 2004). Furthermore, reports suggest that individuals with PAE are overrepresented in psychiatric samples (O’Connor et al., 2006a) and in juvenile detention and correctional settings (Burd et al., 2004; Fast and Conry, 2004).

Importantly, studies demonstrate that alcohol-exposed children without intellectual disabilities may be at greatest risk for poor adaptation. In studies using parent and self-report, alcohol-exposed individuals with less cognitive impairment were found to be more likely than those with intellectual disabilities to lack consideration for the rights and feelings of others, resist limits set by authority figures, and exhibit conduct problems suggestive of early delinquency (Roebuck et al., 1999; Schonfeld et al., 2005). These findings are consistent with the increased rate of delinquency and school failure found in alcohol-exposed adolescents with higher IQs without FAS (Streissguth et al., 1996). Given the high percentage of individuals with PAE who have significant social problems, it is important to begin promoting social problem solving and competence early in development.

Related to their significant social, behavioral, and psychiatric problems, children with PAE are commonly seen in community mental health centers. These centers have various programs designed for children who have specific psychiatric diagnoses such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), mood and anxiety disorders, and pervasive developmental disorders, but generally such programs are not designed specifically for children with PAE. As children with PAE frequently have similar comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, they are often enrolled in community treatment programs, which may or may not be effective for them. Unfortunately, children with PAE often receive treatment that is less than effective because their developmental disability is often not recognized or understood by many mental health professionals and treatment approaches often do not address their specific developmental needs (O’Connor and Paley, 2009). In spite of underrecognition and lack of understanding of FASDs in the majority of mental health settings, the question remains whether, with appropriate training, mental health practitioners can successfully integrate interventions demonstrated to be effective with children with PAE into community settings that serve the general mental health population.

Prior to addressing this question, we first tested the efficacy of an evidence-based manualized social skills treatment protocol, Children’s Friendship Training (CFT; Frankel and Myatt, 2003), on children with PAE in a university-based setting (O’Connor et al., 2006b). The innovation afforded by this intervention was in its incorporation of parents as facilitators of their children’s social competence and in its use with a unique sample consisting only of children with PAE. Results of this controlled efficacy study were that children in the CFT condition showed statistically significant improvement in their knowledge of appropriate social behaviors, improved overall social skills, and a reduction in problem behaviors compared to children in a delayed treatment control condition. The current study represents an important extension of our previous work and is a controlled trial conducted at a community mental health agency. Using this approach, we sought to bridge the transition between university-based research and community implementation.

The aims of the study were (i) to examine the impact of CFT compared to a community Standard of Care (SOC) intervention on the social skills of children seeking treatment in a community mental health center and (ii) to examine whether there was a differential impact of the treatment on children with PAE as compared to children without PAE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Recruitment efforts yielded a total of 100 families who agreed to be screened for eligibility. Following screening, 85 children met eligibility requirements. Failure to meet these requirements was because of the following factors: (i) no reliable documentation of PAE or nonexposure (n = 3); (ii) a previous diagnosis of intellectual disability (n = 1) or pervasive developmental disorder (n = 2); (iii) a composite IQ < 70 (n = 4); or (iv) a conflicting parental work schedule making attendance at groups not possible (n = 5). The majority of children were boys (77.6%), averaging 8.77 (SD = 1.62) years of age. Approximately 25% of the sample was White, non-Hispanic and 75% was Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, or Asian. The participants’ average IQ was 94.92 (SD = 12.43). The majority of the children’s parents were married or living with a partner. Approximately 56% of the parents were Spanish-speaking. Approximately 38% of the children were prenatally exposed to alcohol. The majority of children were being treated for externalizing problems. See Table 1

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variables | Total sample (N = 85) | CFT (n = 41) | SOC (n = 44) | With PAE (n = 32) | Without PAE (n = 53) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child gender, male (%) | 77.6 | 78.0 | 77.3 | 71.9 | 81.1 |

| Child age in years (M, SD) | |||||

| Ethnicity (%) | 8.77 (1.62) | 8.71 (1.72) | 8.83 (1.54) | 8.96 (1.60) | 8.66 (1.63) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 24.7 | 29.3 | 20.5 | 25.0 | 24.5 |

| Child composite IQ (M, SD)a | 94.92 (12.43) | 95.12 (13.01) | 94.73 (12.01) | 94.84 (12.43) | 94.96 (12.97) |

| Primary caregiver married/partner (%) | 71.8 | 73.2 | 70.5 | 65.6 | 75.5 |

| Primary caregiver yrs education (M, SD) | 12.65 (4.15) | 12.78 (3.72) | 12.52 (4.56) | 13.22 (4.66) | 12.30 (3.82) |

| Primary caregiver English-speaking (%) | 56.5 | 58.5 | 54.5 | 71.9 | 47.2* |

| FASD classification | |||||

| FAS | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| pFAS | 11.8 | 14.6 | 9.1 | 31.3 | 0 |

| ARND | 22.4 | 19.0 | 25.0 | 68.8 | 0 |

| Completed 4+ sessions | 75.3 | 78.0 | 72.7 | 81.3 | 71.7 |

| Prenatal alcohol exposure (%) | 37.6 | 41.5 | 34.1 | 100 | 0 |

| CFGC diagnosis externalizing (%) | 62.4 | 63.4 | 61.4 | 53.1 | 67.9 |

ARND, alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder; CFGC, Child and Family Guidance Center; CFT, Children’s Friendship Training; FAS, fetal alcohol syndrome; FASD, Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders; PAE, prenatal alcohol exposure; pFAS, partial FAS; SOC, Standard of Care.

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test Composite IQ.

p < 0.05.

Description of the Community Partner: Child and Family Guidance Center

The Child and Family Guidance Center (CFGC) is a 501(c)3 nonprofit corporation that has been providing services for children and their families in the San Fernando and Antelope Valleys of California since 1962. The CFGC mission is to promote better mental health for children and their families in response to individual and community needs, and in coordination with community resources. A particular strength of CFGC is its openness to working with other community agencies and past experience in working with university investigators on federally funded research projects.

Located on the main campus of the Center, the Northridge Outpatient Department provides mental health services including individual, family and group treatment, psychiatric services, and case management. Approximately 300 elementary-aged children each year are seen in the outpatient department. Therapeutic groups offered in the outpatient department cover a broad spectrum of issues and include parenting groups, ADHD parent and child groups, multifamily groups, acculturation issues groups, social skills groups, and anger management groups. Most treatment groups are offered in English and Spanish to accommodate Spanish-speaking children and their families.

CFGC Staff

For this study, the administrative liaisons from CFGC were the Director of Outreach/Outpatient Treatment Programs (KW-T) and the Division Manager of the Outpatient Treatment Services (EL). The multidisciplinary professional staff includes: psychiatrists, psychologists, psychology interns, clinical social workers, social work interns, marriage and family therapists, recreation therapists, special education teachers, speech therapists, and psychiatric nurses.

Institutional Review Board and Informed Consent

The university institutional review board approved all procedures and acted as the oversight agency for CFGC. A certificate of confidentiality was obtained from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Informed consent was obtained from the parent(s) and assent from children ≥7 years of age.

Study Design and Procedures

Participants were recruited from September 2006 to May 2009. As part of CFGC protocol, all children and families were required to complete 2 intake sessions with a CFGC clinician composed of an assessment session and a treatment planning session. During the intake, demographic information, physical health, and mental health status and history were obtained. After the assessment phase, the treatment plan was developed with the family. All children who were determined to be able to benefit from social skills intervention were invited to participate in the study. Prior to their participation, the clinician explained the purpose of the research to the parent(s) and the child. All interested families were offered an appointment for evaluation to determine eligibility.

To meet the eligibility criteria, all children had to (i) be between 6 and 12 years of age; (ii) have a composite IQ of ≥70; (iii) be English speaking; (iv) be living with at least 1 custodial parent or guardian who agreed to be responsible for the consistent implementation of the treatment; and (v) have varying degrees of PAE from no exposure to heavy exposure. Parents could be either English- or Spanish-speaking. Children were not enrolled if they had major sensory or motor deficits or a past diagnosis of intellectual disability, psychotic disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder.

Once eligible, children were assigned to 1 of 2 conditions: CFT or SOC. Each consecutive set of approximately 14 eligible children formed a cohort and children within a cohort were assigned, in alternating sequence based on when they were evaluated, to 1 of the 2 study conditions with an attempt to equate groups on gender, ethnicity, and whether they had PAE. In addition, families having 2 children in the study were allowed to have both children in the same condition. Children were treated in 6 cohorts averaging approximately 7 children in each condition. In the CFT condition, 2 therapists led each child group and 2 therapists led each parent group (n = 4). Two therapists lead each child group in the SOC condition (n = 2). There was no parent component in the SOC condition. To make conditions as comparable as possible, we attempted to match the therapists in the CFT condition with those in the SOC condition on gender, age, ethnicity, educational degree, and years of experience.

Both the CFT and the SOC conditions consisted of 12 sessions, of 90 minutes each, delivered over the course of 12 weeks. In the CFT condition, parents attended separate concurrent sessions in which they were instructed on the key skills being taught to their children. The parents were also taught how to facilitate social competence in their children by arranging play dates, facilitating completion of weekly homework assignments, and providing in vivo social coaching when appropriate. Meetings were held in the early evening, and child care was provided for siblings. Outcome measures were administered to participants in both the CFT and the SOC conditions prior to treatment (pretreatment) and following treatment (posttreatment).

CFT Condition

The intervention procedure used in this study and its social skills components have been validated empirically and have been successfully implemented for children with and without PAE (Frankel, 2005; Frankel and Myatt, 2003; Frankel et al., 1997, 2010; O’Connor et al., 2006b). The CFT intervention was modified with specific treatment adaptations to account for the neurocognitive deficits common among children with PAE (Laugeson et al., 2007). The modifications made primarily involved augmentation in how the treatment was delivered, rather than changes in the content or components of the intervention, thus preserving the basic integrity of the treatment. Skills taught included the following: (i) social network formation with the aid of the parent (Parke et al., 1994); (ii) informational exchange with peers leading to a common-ground activity (Black and Hazen, 1990); (iii) entry into a group of children already in play (Gelb and Jacobson, 1988); (iv) in-home play dates (Frankel, 2005; Frankel and Myatt, 2003); and (v) conflict avoidance and negotiation (Rose and Asher, 1999). See Table 2 for a more detailed outline of the social skills curriculum. The key social skills of CFT were taught using instruction on simple rules of social behavior; modeling, behavioral rehearsal, and performance feedback through coaching during treatment sessions; distribution of parent handouts outlining the skills being taught to children; behavioral rehearsal at home; weekly socialization homework assignments; and social coaching by parents during play with a peer. Parents were able to choose whether they wanted to participate in a Spanish-speaking or English-speaking treatment group. All Spanish-speaking groups were conducted by bilingual and bicultural therapists.

Table 2.

Description of Child and Parent Treatment Sessions

| Session | Topic child group | Goals—child group | Topic parent group | Goals—parent group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rules of the group; elements of good communication | Children learn and practice elements of good communication by introducing themselves to one another | Goals and methods of treatment; limitations of intervention; what not to expect | Parents learn about importance of their role in the intervention; group leader reviews context and stability of sociometric categories |

| 2 | Having a conversation | Children learn how to exchange information; identify good and bad places to make friends | Having a conversation | Parents learn how to help their child develop two-way conversation skills; how to better communicate with their child |

| 3 | Joining a group of children already at play: “slipping in” | Children learn when, where, and how to “slip in” or join a group of children already at play | Supporting child friendships | Parents learn about appropriate settings for play dates; sources of potential playmates; importance of adequate time availability for play dates. |

| 4 | Joining a group of children already at play: “slipping in” | Children learn more techniques for group entry, reasons for rejection from group entry, and what to do in response to rejection | Joining a group of children already at play, “slipping in” | Parents learn when, where, and how their children should “slip in” to a group of children already at play; importance of their child taking “no” for an answer |

| 5 | How to be a good sport | Children learn and practice basic rules of being a good sport | Joining a group of children already at play, “slipping in” | Parents learn how to help their child practice “slipping in” outside of the session |

| 6 | How to be a good sport | Children learn to praise other children, techniques of persuasion and negotiation | Appropriate games for play dates | Parents learn appropriate games and identify games to exclude for indoor and outdoor play |

| 7 | Rules of being a good host | Children learn and practice rules of being the “host” during interactive indoor games | Play dates | Parents learn about sources for potential playmates for their child. Parents learn about their responsibilities for the play date |

| 8 | How to handle teasing | Children learn and practice strategies for reacting neutrally or humorously to teasing, so as to reduce the likelihood of further teasing | How to handle teasing | Parents learn about effective strategies their child can use to handle teasing and are instructed on appropriate role-play strategies for practice |

| 9 | Unjustified accusations | Children learn how to handle situations when unjustly accused of bad behavior by an adult | How to handle adult complaints about child’s behavior | Parents learn how to respond appropriately and effectively to other adults who complain about their child’s behavior so as to minimize their child getting a negative reputation |

| 10 | How to be a good winner | Children learn and practice rules of being a good winner | How to be a good winner | Parents learn rules of being a good winner and how to encourage their child’s practice of those rules |

| 11 | Bullies and conflict situations | Children learn how to avoid conflict and have the opportunity to practice strategies for conflict resolution | Bullies and conflict situations | Parents learn how to support their child’s use of strategies for defusing confrontations with another child |

| 12 | Graduation | Posttreatment evaluation, graduation ceremony, and party for the children and their parents | Graduation | Parents complete posttreatment evaluation and participate in the child’s graduation ceremony and party |

Therapist Training in CFT.

All therapists were chosen by the CFGC administration. Training procedures that were developed for the university-based efficacy study were adapted using input from CFGC supervisors and therapists. It has been our experience that most community providers, while they are aware that alcohol is a physical and behavioral teratogen, often do not understand the ways in which a prenatally alcohol-exposed child’s behavior may be a function of the significant primary deficits associated with brain damage. Therefore, the first task of training was to educate the therapists about the challenges faced by children with PAE. Didactic information was provided on the diagnosis of FASDs, on the primary and secondary disabilities of children with PAE, and on treatment strategies that are effective with these children.

Following training on the effects of PAE, we introduced the therapists in the CFT condition to the CFT protocol. The training began with didactic instruction on the developmental literature pertaining to children’s friendships, the theoretical and empirical rationale underlying the treatment protocol, and a review of the elements of the treatment. In addition to didactic instruction and discussion of the treatment protocol, the training incorporated live role-play demonstrations and a review of video demonstrations of each of the 12 parent and child sessions that were developed for this study.

Common therapist concerns were explicitly addressed in training, including concerns that it would be difficult to establish a therapeutic relationship with participants using a manualized treatment or that it would be difficult to apply the treatment flexibly to meet participants’ individual needs. To address therapists’ concerns about using the treatment in a flexible manner, information about the theoretical underpinnings for each key component was provided to help therapists understand how to preserve the integrity of those key components while still meeting the needs of the participants. Specific examples were provided regarding how various components could be adapted for particular participants, such as using the extensive homework review portion of each session to troubleshoot treatment barriers, thereby individualizing the treatment to meet the specific needs of each child. Upon completion of the initial training, therapists were assessed with a criterion-referenced test developed for the study to ensure that they had acquired sufficient knowledge and competence to deliver the treatment. To preserve the integrity of the treatment protocol, therapists were advised not to share any of the information or techniques that they had learned with other therapists at the CFGC.

Therapist Supervision in CFT.

Therapists met with study clinical psychology supervisors (EL and CM) for 1 hour per week to discuss the issues that arose during the previous treatment session and to address any questions about the upcoming session. A few issues that arose in the parent groups included how to help parents overcome barriers to implementation of the homework assignments, how to work with parents who speak negatively about their children, and how to handle parents who monopolize group conversation. The clinical supervisors also addressed how to work with children who were disruptive to the group, shy or anxious, or overly active or inattentive. In light of the many cognitive and learning challenges encountered by children with PAE, strategies for facilitating the children’s understanding and application of the material taught to them were also reviewed.

Treatment Integrity of CFT.

For the first cohort, the study supervisors observed all 12 sessions of both the parent and child groups in person to provide feedback to the therapists immediately following the sessions and to ensure that fidelity to the treatment protocol was adequately established. For subsequent cohorts, staff members from the research team, trained to reliability, observed and coded each parent and child session live using fidelity checklists covering the primary content of the protocol. If a therapist failed to cover any of the primary content in any session, the coder reminded the therapist during the sessions.

Treatment integrity was ensured using the guidelines of Moncher and Prinz (1991) through the use of trained and qualified therapists, standardized treatment manuals, ongoing weekly supervision, and live monitoring of sessions using fidelity checklists.

Community SOC Condition

The SOC for social skills training at CFGC was also conducted in a group format. The social skills groups were process-oriented as well as behaviorally based, involving group discussion and cooperative projects. The treatment focused on different topics such as characteristics of good friends, how to give appropriate feedback to a peer, expressing and managing feelings, decisionmaking, and accepting and giving compliments. In addition, the children participated in group projects, such as making collages that required sharing and teamwork. In contrast to the CFT treatment condition, the SOC condition involved discussion and practice of rules of social behavior typically thought important by adults, but not necessarily empirically demonstrated to be predictive of peer acceptance nor often practiced by socially skilled children in naturalistic settings (Frankel, 2005). Moreover, the SOC condition did not include parental participation. Therapists in the SOC condition were provided weekly supervision by their CFGC supervisors

FASD Diagnosis

Every child received a physical examination to assess for the presence of the diagnostic features of FASD using the Diagnostic Guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (Astley, 2004). This system uses a 4-digit diagnostic code reflecting the magnitude of expression of 4 key diagnostic features of FAS: (i) growth deficiency; (ii) the FAS facial phenotype, including short palpebral fissures, flat philtrum, and thin upper lip; (iii) central nervous system dysfunction; and (iv) gestational alcohol exposure. Using this code, the magnitude of expression of each feature was ranked independently on a 4-point scale with 1 reflecting complete absence of the FAS feature and 4 reflecting the full manifestation of the feature. The study physician administered this examination after achieving 100% reliability with the senior study clinician (MJO) who has extensive expertise in the use of the diagnostic system and who was trained by Dr. Astley, the developer of the system. The physician was unaware of the participants’ PAE history or social skills group assignment. After the 4-digit code for each participant was calculated, participant diagnosis was converted to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) criteria according to the guidelines developed by Dr. Astley (personal communication, July 2005).

Measures

Measures were presented to the children in English. Parents could choose to complete measures in English or Spanish. To accommodate Spanish-speaking parents, all study measures were translated and back-translated into Spanish if they were not already published in Spanish.

Eligibility Measures

Demographic Questionnaire.

All parents completed a demographic questionnaire that included the child’s gender, age, ethnicity, caregiver marital status, years of education, and language preference (English or Spanish).

Health Interview for Women.

All biological mothers were interviewed using the Health Interview for Women (O’Connor et al., 2002), which yields standard measures of the average number of drinks per drinking occasion and the frequencies of those occasions. One drink was considered to be 0.60 oz of absolute alcohol (e.g., one 12-oz can of beer containing 5% absolute alcohol was considered 1 drink).

Questionnaire for Foster/Adoptive Parents.

For adopted or foster children, medical or legal records documenting known exposure or reliable collateral reports by others who had observed the mother drinking during pregnancy were obtained. Such documentation included medical records that indicated the biological mother was intoxicated at delivery, or records indicating that the mother was observed drinking alcohol during pregnancy by a reliable collateral source (i.e., friend, close relative, partner, or spouse). These records provided sufficient information to meet the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic Guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (Astley, 2004). Because many children with PAE are in foster care or adopted, it is often necessary to employ review of such records as an accepted method for establishing PAE in the scientific community.

Nonexposure was defined as exposure to less than 1 drink of alcohol throughout pregnancy. Children with unknown exposure were not included in the study.

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test—Second Edition (K-BIT-2).

The K-BIT-2 (Kaufman and Kaufman, 2004) is a brief screening tool used to assess intellectual functioning along verbal (verbal subtest) and nonverbal (nonverbal subtest) domains. Normative data are available for individuals aged 4 to 90 and are presented as standard scores with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. The K-BIT-2 verbal subtest is used as a screening of receptive vocabulary, verbal comprehension, verbal reasoning, and factual knowledge. The K-BIT-2 nonverbal subtest is used as a screening of nonverbal intellectual functioning and involves nonverbal perceptual reasoning and flexibility in problem solving. The K-BIT-2 IQ composite score is an estimate of general intellectual functioning and is presented as a standard score with a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. The test has high internal consistency across ages 4 through 18 for the verbal (M = 0.90) and nonverbal subtests (M = 0.88), as well as the IQ composite (M = 0.93). Test–retest reliability is 0.88 for verbal, 0.76 for nonverbal, and 0.88 for the IQ composite scores. The correlation between the IQ composite score and the General Ability Index of the WISC-IV is 0.84.

Outcome Measures

Test of Social Skills Knowledge (TSSK).

The TSSK is a 17-item forced choice criterion-based measure designed to assess children’s social skills knowledge (Frankel, 2005). The items, which were read to the child, directly relate to social skills relevant for successful social interaction. This measure, and similar measures, has been used successfully in evaluating treatment gains in other studies of social skills training (Frankel and Myatt, 2003; Frankel et al., 2010; O’Connor et al., 2006b; Pfiffner and McBurnett, 1997). Scores on the TSSK range from 0 to 17, with a higher score reflecting higher social skills knowledge.

Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale-Second Edition (Piers-Harris 2).

The Piers-Harris 2 (Piers and Herzberg, 2005) is a 60-item self-report questionnaire designed for children between the ages of 6 and 18 years of age. In this study, the measure was read to all children. The Piers-Harris 2 items are statements that express how people may feel about themselves using a “yes” or “no” response. The measure includes a Total Self-Concept score which is a general measure of the respondent’s overall self-concept and 6 domain scales that assess specific components of self-concept. The domain scales include behavioral adjustment, intellectual and school status, physical appearance and attributes, freedom from anxiety, popularity, and happiness and satisfaction. Higher scores reflect more positive self-evaluation. The Piers-Harris 2 has high construct validity, correlating significantly with other established measures of child self-concept. The Piers-Harris 2 demonstrates good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74–0.91). Although test–retest reliability has yet to be established for the Piers-Harris 2, reliability has been reported to range from 0.65 to 0.87 for the total and domain scales of the original Piers-Harris Scale (Hattie, 1992). Feelings of low self-concept have been described clinically in children with PAE and have been demonstrated to relate to parent ratings of social competence (Frankel and Myatt, 2003).

Social Skills Rating System-Parent Form (SSRS-P).

Social skills were evaluated with the SSRS-P (Gresham and Elliott, 1990). Two scales comprise the SSRS-P: social skills and problem behaviors, presented as standard scores (M = 100; SD = 15). For this study, only the social skills scale and its index measures were examined. The social skills index scales measure cooperation, assertion, responsibility, and self-control. These indices are coded as raw scores. Higher scores represent better social functioning. The SSRS-P has high construct validity, correlating significantly with other established measures of child social behaviors. The SSRS-P has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.65–0.87) and test–retest reliability (0.77–0.87).

Satisfaction Measures

Parent Satisfaction.

A parent satisfaction questionnaire was developed for this study and was used to assess parent satisfaction with the CFT or SOC treatment programs. The parent (s) were asked to rate if they thought that their child was better able to get along with other children, if they felt confident that they could better facilitate their child’s friendship seeking attempts, and their overall satisfaction with the treatment. All items were scored on a 3-point scale, with a score of 3 reflecting that they strongly agreed or were satisfied with the treatment, a score of 2 reflecting a neutral opinion, and a score of 1 reflecting that they strongly disagreed or were dissatisfied with the treatment.

Therapist Satisfaction.

Therapists were asked whether the CFT program was helpful to their clients, if their clients enjoyed the treatment, if they would like to see the program adopted permanently at CFGC, and if they would continue to use the program after the study was over. These items were scored similarly to the items on the Parent Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Data Analysis Plan

Data analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistical Analysis software (17.0). The participants’ knowledge of social skills measure (TSSK), self-report on the self-concept scale (Piers-Harris 2), and the parent report on social skills behaviors (SSRS-P) were assessed prior to treatment (pretreatment), and at the end of the 12-week treatment (posttreatment) for both the CFT and the SOC conditions. The effectiveness of the treatment was evaluated using separate 2 × 2 treatment condition (CFT, SOC) × alcohol exposure (with PAE, without PAE) analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs), performed at the group level, using the posttreatment TSSK, Piers-Harris 2, and SSRS-P scores as outcome variables. Treatment (CFT vs. SOC) and alcohol exposure (with PAE, without PAE) were the grouping factors, and pretreatment scores on the TSSK, Piers-Harris 2, and SSRS-P were used as the primary covariates. Cohort, child gender, age, ethnicity, K-BIT composite IQ, and FASD classification were evaluated in preliminary correlational analyses to determine whether they should be included as possible covariates. Other possible covariates included caregiver marital status, years of education, and language preference. None of these variables was found to be significantly related to the outcome measures and thus they were not included in the statistical models.

Two effect sizes were calculated. The first was the standardized difference in means based on the raw group means posttreatment divided by the pooled standard deviation across groups, namely Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988). By convention, d = 0.5 corresponds to a medium effect size and d = 0.8 to a large effect size. In this case, the confidence intervals can be approximated analytically (Odgaard and Fowler, 2010). Cohen’s d has the advantage of being easy to interpret as it is given in terms of the observed outcome. However, the effect size corresponding to the raw difference in means is likely to be overly conservative in this study as it does not take advantage of the information supplied by the pretreatment measurement of the outcome and the child’s PAE. The second effect size calculated was Cohen’s f2 for the main effect of group in the full model, which was a 2 × 2 ANCOVA (treatment condition by alcohol exposure) with pretreatment scores on the TSSK, Piers-Harris 2, and SSRS-P used as the primary covariates. Cohen’s f2 reflects the amount of variability in the outcome that is explained by the variable of interest after adjusting for the presence of the other predictors. Values around 0.02 are considered small effects, values around 0.15 are considered medium effects, and values around 0.35 are considered large effects. The confidence intervals for f2 were obtained via a bootstrap resampling procedure (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993) as there is no simple analytical approximation formula.

The study was powered for the primary aim which was to detect differential treatment effects favoring the CFT over the SOC group. The main hypotheses were directional because CFT had already shown success in previous studies (O’Connor et al., 2006a,b), so a 1-sided significance level of alpha = 0.05 was employed. With a total of 84 subjects (42 per group), a 2-sample t-test has 74% power to detect a posttreatment group difference of d = 0.5, a conventional medium effect. With the addition of a baseline covariate accounting for 25% of the variance (i.e., a conservative pre–postcorrelation of r = 0.5), the power rises to 83%.

RESULTS

Participant Attrition

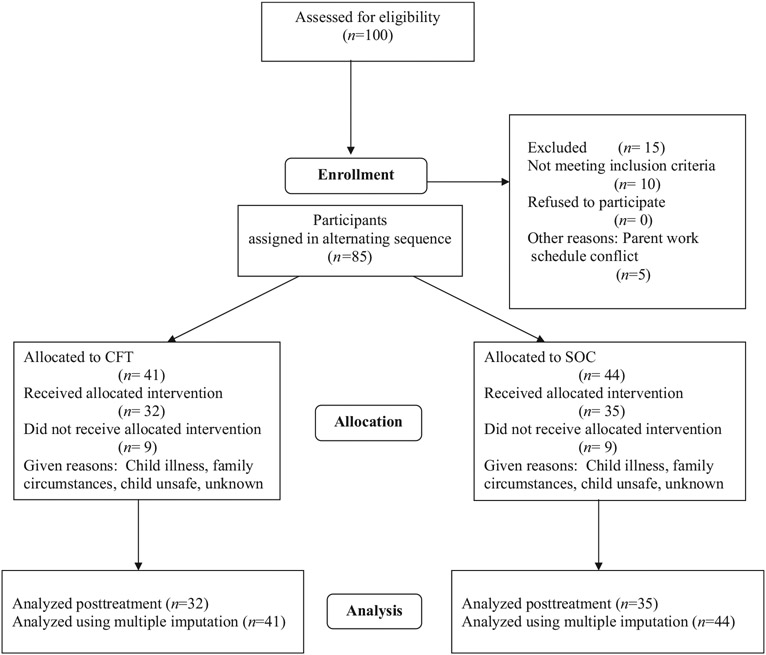

Of the 85 children who were recruited and found eligible for the study, 41 were assigned to the CFT condition and 44 were assigned to the SOC condition. Of that number, 67 children (CFT, n = 32; SOC, n = 35) completed the 12-week study. Thirteen children did not start the treatment because of illness or family circumstances (CFT, n = 7; SOC, n = 6), and 2 were asked to leave the program because of significant disruptive behavior that could not be safely monitored in the groups (CFT, n = 1; SOC, n = 1). There were 3 (CFT, n = 1; SOC, n = 2) other noncompleters who provided no explanation for not finishing treatment. The attrition rate for this study was 21% and was consistent with the rates of approximately 20% for other treatment groups at CFGC. Completers did not differ from noncompleters on any child or caregiver pretreatment characteristics or on treatment condition or alcohol exposure. See Fig. 1 for a flow chart depicting recruitment and retention of participants.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart depicting recruitment and retention of participants across the study.

Analyses included all participants with outcome data; however, to check for possible effects of missing data on the results, supplemental analyses were carried out on each of the outcome measures using multiple imputation (Rubin, 1987). These supplemental analyses were not meaningfully different from the primary analyses and are not reported.

Pretreatment Comparison of CFT to SOC

Chi-square and independent t-tests revealed no statistically significant differences at pretreatment between the CFT and SOC conditions on study demographic variables. See Table 1 for a summary of sample characteristics as a function of condition.

Comparison of Therapist Characteristics in CFT Versus SOC

The therapists in the CFT and SOC conditions were compared on age, ethnicity, highest educational degree, and years in practice. Therapists in the CFT and SOC conditions did not differ significantly on any of these variables, which can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Therapists’ Characteristics

| Variables | Total sample (N = 21) |

CFT (n = 15) |

SOC (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Therapist gender, female (%) | 95.2 | 93.3 | 100 |

| Therapist age (M, SD) | 29.57 (5.28) | 29.67 (5.91) | 29.33 (1.50) |

| Therapist ethnicity | |||

| White, non-Hispanic (%) | 85.7 | 86.7 | 83.3 |

| Degree, master’s+ (%) | 61.9 | 60.0 | 66.7 |

| Therapist years in practice (M, SD) | 3.71 (4.16) | 3.90 (4.72) | 3.25 (2.56) |

CFT, Children’s Friendship Training; SOC, Standard of Care.

Pretreatment Comparison of Participants with PAE to those without PAE

As expected, children with PAE were diagnosed with features associated with FASD. Using the IOM conversion, 0% of children with PAE were diagnosed with FAS, 31.3% of the children were diagnosed with pFAS, and 68.8% were diagnosed with ARND. No child met the criteria for ARBD. No child without PAE met the criteria for any FASD diagnosis.

Children with PAE were more likely to have parents who were English-speaking than parents who were Spanish-speaking, Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.05. Otherwise, there were no statistically significant differences between children with or without PAE on parent or child characteristics, which can been seen in Table 1

Children’s Report of Social Skills Knowledge.

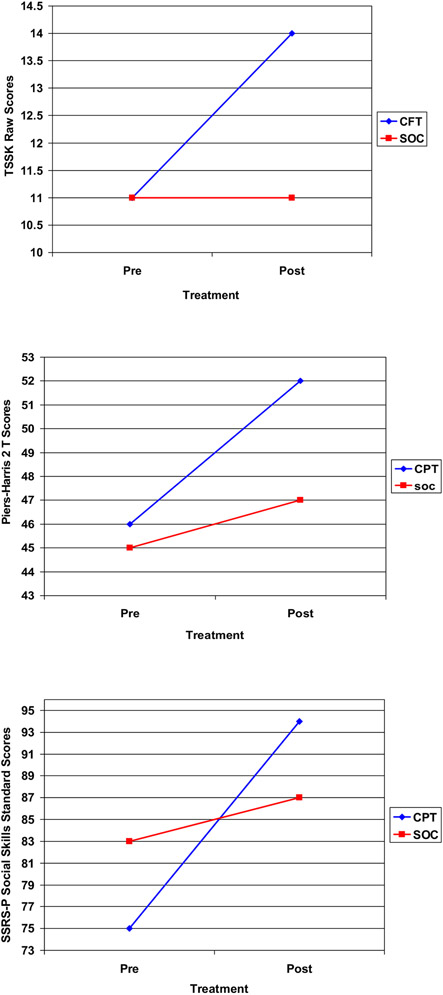

A 2 × 2 treatment condition (CFT, SOC) × alcohol exposure (with PAE, without PAE) ANCOVA was conducted on the posttreatment scores derived from the TSSK completed by the children. The analysis yielded a significant condition effect, with the children in the CFT showing significantly improved knowledge of appropriate social skills compared to children in the SOC condition, F(1, 62) = 21.34, p < 0.0001. There were no other significant main or interaction effects. See Table 4 for pretreatment mean scores and standard deviations, posttreatment estimated mean scores and standard errors, effect sizes and confidence intervals. Also see Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Comparison of Children’s Friendship Training (CFT) to Community Standard of Care (SOC)

| Pretreatment |

Posttreatment |

Effect sizes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFT |

SOC |

CFT |

SOC |

d (95% CI) |

F2(95% CI) |

|

| Variables |

M (SD) n = 32 |

M (SD) n = 35 |

Est M (SE) n = 32 |

Est M (SE) n = 35 |

Posttreatment | Posttreatment adjusted |

| Child | ||||||

| TSSK | 11.03 (2.42) | 10.63 (2.43) | 14.22 (2.21) | 11.40 (2.42) | 1.22 (0.69, 1.73) | 0.34 (0.09, 0.90)*** |

| Piers-Harris 2 | 46.16 (7.63) | 45.20 (8.33) | 51.75 (7.43) | 47.63 (10.39) | 0.45 (−0.03, 0.94) | 0.07 (0.001, 0.30)* |

| Behavioral adjustment | 47.13 (8.98) | 45.66 (8.85) | 52.69 (8.83) | 47.51 (8.95) | 0.58 (0.09, 1.07) | 0.09 (0.004, 0.36)* |

| Intellectual/school status | 48.56 (7.49) | 49.66 (8.04) | 51.69 (6.77) | 48.71 (8.42) | 0.39 (−0.10, 0.87) | 0.10 (0.006, 0.34)* |

| Physical appearance | 47.13 (8.86) | 46.83 (9.49) | 48.25 (7.34) | 48.23 (9.10) | 0.003 (−0.48, 0.48) | 0.002 (0.00001, 0.10) |

| Freedom from anxiety | 47.31 (9.45) | 46.40 (8.93) | 54.97 (7.66) | 48.63 (10.10) | 0.70 (0.21, 1.19) | 0.12 (0.008, 0.42)** |

| Popularity | 43.41 (6.92) | 43.23 (7.28) | 46.41 (8.14) | 45.57 (9.77) | 0.09 (−0.39, 0.57) | 0.008 (0.00003, 0.13) |

| Happiness | 48.09 (8.11) | 47.00 (9.07) | 53.56 (7.24) | 50.63 (8.19) | 0.38 (−0.11, 0.86) | 0.03 (0.0001, 0.20) |

| Parent | ||||||

| SSRS-SS | 75.09 (12.62) | 82.89 (18.09) | 90.84 (16.84) | 88.51 (17.45) | 0.14 (−0.34, 0.62) | 0.04 (0.0002, 0.22) |

| Cooperation | 7.50 (3.21) | 8.63 (3.81) | 10.59 (4.21) | 10.43 (4.02) | 0.04 (−0.44, 0.52) | 0.005 (0.00002, 0.12) |

| Assertion | 10.88 (3.38) | 12.29 (3.35) | 13.31 (3.29) | 12.71 (3.50) | 0.18 (−0.31, 0.66) | 0.07 (0.0009, 0.28)* |

| Responsibility | 9.34 (3.15) | 10.91 (3.00) | 12.56 (3.23) | 12.06 (2.97) | 0.16 (−0.32, 0.64) | 0.07 (0.001, 0.31)* |

| Self-control | 7.56 (3.20) | 9.54 (3.83) | 10.03 (2.96) | 10.00 (3.35) | 0.01 (−0.47, 0.49) | 0.01 (0.00004, 0.12) |

Analyses included all participants with outcome data; however, to check for possible effects of missing data on the results, supplemental analyses were done on each of the outcome measures using multiple imputation (Rubin, 1987). These supplemental analyses were not meaningfully different from the primary analyses and are not reported. TSSK, Test of Social Skills Knowledge; SSRS-SS, Social Skills Rating System-Social Skills; Piers-Harris 2, Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale.

Two effect sizes are reported. The first is the standardized difference in means based on the raw group means posttreatment, namely Cohen’s d. By convention, d = 0.5 corresponds to a medium effect size and d = 0.8 to a large effect size. In this case, the confidence intervals can be approximated analytically (Odgaard and Fowler, 2010). Cohen’s d has the advantage of being easy to interpret as it is given in terms of the observed outcome. However, the effect size corresponding to the raw difference in means is likely to be overly conservative in this study as it does not take advantage of the information supplied by the pretreatment measurement of the outcome and the child’s prenatal alcohol exposure. The second effect size shown is Cohen’s f2 for the main effect of group in the full model, which is a 2 × 2 ANCOVA (Treatment Condition × Alcohol Exposure) with pretreatment as a covariate. Cohen’s f2 reflects the amount of variability in the outcome that is explained by the variable of interest after adjusting for the presence of the other predictors. Values around 0.02 are considered small effects, values around 0.15 are considered medium effects, and values around 0.35 are considered large effects. The confidence intervals for f2 presented in the last column were obtained via a bootstrap resampling procedure (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993) as there is no simple analytical approximation formula.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of Children’s Friendship Training (CFT) to Community Standard of Care (SOC). TSSK, Test of Social Skills Knowledge; Piers-Harris 2, Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale-Second Edition; SSRS-P, Social Skills Rating System-Parent Form (SSRS-P).

Children’s Report of Self-Concept.

The 2 × 2 treatment condition (CFT, SOC) × alcohol exposure (with PAE, without PAE) ANCOVAs were conducted on the posttreatment scores derived from the Piers-Harris 2 completed by the children. The analysis yielded a significant condition effect, with the children in the CFT showing significantly improved overall self-concept, F(1, 62) = 4.21, p < 0.05. Specifically, on individual domains of self-concept, children reported improved behavioral adjustment, F(1, 62) = 5.69, p < 0.02, intellectual/school status, F(1, 62) = 6.01, p < 0.02, and freedom from anxiety, F(1, 62) = 7.63, p < 0.01, compared to children in the SOC condition. They did not report significant improvement in physical appearance, F(1, 62) = 0.12, p = 0.73, popularity, F(1, 62) = 0.51, p = 0.48, or happiness and satisfaction, F(1, 62) = 1.85, p = 0.18. There were no other significant main or interaction effects. See Table 4 and Fig. 2.

Parent Report of Social Skills.

The 2 × 2 treatment condition (CFT, SOC) × alcohol exposure (with PAE, without PAE) ANCOVAs were conducted on the posttreatment scores derived from the SSRS-P completed by the parents. The analysis yielded no significant condition effect in improvement of overall social skills, F(1, 62) = 2.37, p = 0.12. This was because the 2 groups differed on their pretreatment social skills scores. Some children in the SOC group started out scoring higher than the children in the CFT group and actually demonstrated a significant decline in social skills according to parent report. The CFT group, while showing a significant 18 point improvement compared to the improvement of 4 points in the SOC group, did not differ from the SOC group after controlling for pretreatment levels. However, analyses of individual index scores revealed statistically significant condition effects for assertion, F(1, 62) = 4.04, p < 0.05, and responsibility, F(1, 62) = 4.53, p < 0.04, in favor of the children in the CFT condition over the children in the SOC condition. Analyses of cooperation, F(1, 62) = 0.30, p = 0.59, and self-control, F(1, 62) = 0.75, p = 0.39, did not yield statistically significant effects. There were no other significant main or interaction effects. See Table 4 and Fig. 2.

Parent Satisfaction

Families were queried on parent satisfaction with the treatment that they received in both the CFT and the SOC conditions. In the CFT condition, 90.7% of parents reported confidence in their children’s ability to get along better with other children because of the treatment. In the SOC condition, 68.6% of the parents reported that they were confident that their children would get along better because of the treatment, Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.04. While 87.5% of parents in the CFT condition reported that they were confident that they were better able to help their children make and keep friends because of the treatment, only 57% of parents in the SOC condition reported feeling confident that they were better able to help their child, Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.007. Groups were comparable in their overall satisfaction with both the CFT and the SOC treatments, Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.68. Overall, 93.7% of the parents in the CFT group reported being very satisfied or highly satisfied with the treatment that their children received and 88.6% of the parents in the SOC condition reported similar satisfaction.

Therapists’ Assessment of Treatment Effectiveness

Posttreatment data were collected from CFT therapists on their assessment of the effectiveness of CFT in their treatment setting. When asked whether CFT was helpful to their clients, 84% of therapists agreed or strongly agreed. One hundred percent agreed or strongly agreed that their clients enjoyed the treatment. Over 92% agreed that they would like to see the program adopted permanently at CFGC and would continue to use it. However, there were concerns voiced by the therapists, suggesting that it was hard to integrate the treatment into their already busy schedules and significant clinical responsibilities. They also expressed a desire to have more time to prepare for the groups.

DISCUSSION

Children enrolled in a community mental health center who participated in CFT showed clear evidence of improvement in their knowledge of appropriate social behaviors posttreatment, as compared to children in the community SOC. Moreover, CFT was also effective in significantly changing children’s self-concepts particularly in the areas of behavioral adjustment, intellectual/school status, and freedom from anxiety. These findings are not surprising in that many items, such as “I get into a lot of fights,” “I am dumb about most things,” “I am shy,” “I am nervous,” “I worry a lot,” “ I feel left out of things,” and “I am often afraid,” reflect concepts that are likely to change with more confidence and success in social situations. Likewise, children appeared to be realistic about the limits of their social skills training reporting that it had little effect on their physical appearance “I am good looking,” their overall popularity “I have many friends,” or happiness “I am a happy person.” Although there was not a significant statistical difference in parent report of overall social skills between the CFT and SOC groups because of differing initial levels, there were some children in the SOC group who actually became worse unlike children in the CFT group who generally showed improvement as a function of treatment. On specific indices, children in the CFT condition showed improvement on items on the assertion subscale such as “makes friends,” “is self-confident in social situations,” “introduces self,” “starts conversations,” “joins group activities,” “invites others home,” and “participates in group activities.” On the subscale responsibility, parents reported that their children demonstrated improvement on items such as “shows concern for friends,” “waits turn in games,” “is liked by others,” and “follows rules in games.” Many of these attributes and skills were directly addressed in the CFT intervention such as how to start a conversation, how to join a group of children at play, and good sportsmanship.

In contrast, parents did not report changes on subscales of the SSRS-P reflecting self-control which measures the child’s ability to control their tempers in conflict situations or on cooperation which measures the child’s compliance with parental and teacher directives. These findings are not surprising in light of the fact that children with psychopathology requiring mental health treatment often have problems in behavioral regulation. These results suggest that adjunctive therapies such as parent training, family therapy, and psychopharmacological interventions might improve these behavioral outcomes.

A goal of this study was to determine whether there were differences between children with PAE and those without PAE in responsiveness to the social skills treatment protocol. Results revealed that children with and without PAE who were enrolled in the CFT condition showed similar positive responses to treatment. There was clear evidence of improvement as reported by both children and parents regardless of prenatal alcohol history. These findings indicate that children with PAE can benefit from treatments initiated in community settings in which therapists are trained to understand their unique developmental needs. In addition, children with PAE can be successfully integrated into treatment protocols that include children without PAE. Findings also revealed that parents were highly satisfied with the treatment and therapists reported that they were able to integrate the treatment protocol into their practices and planned to continue to use it after study completion. These findings are extremely important in that there are few mental health providers with extensive expertise in working with children with PAE in most communities. Furthermore, there is a great need for these children to be treated in settings that commonly accommodate populations with more diverse mental health, behavioral, and social problems.

One caveat to these positive findings is that the CFGC therapists indicated that they felt they needed more time to prepare for the intervention. This is a commonly voiced concern of mental health professionals working in busy community mental health clinics who must account for their time based upon the number of clients they treat and the hours for which they can bill. Although CFGC was an exemplary community partner, the constraints under which therapists operate are understandable and their willingness to incorporate new evidence-based treatments is commendable. To be successful, community agencies must be willing to allow their staff time to learn new therapies and reward them for their special expertise.

The conclusions of this study should be considered in the context of some methodological issues. The absence of independent evaluation of child behaviors represents a limitation of the study, and future research would ideally measure social behaviors in more naturalistic settings such as during unstructured play both at home and at school.

An additional possible limitation of the study is that parents who participated in the CFT treatment may have overestimated changes in their children simply as a function of being involved in treatment compared to parents in the SOC group who did not participate in a parent component. Although this is a plausible explanation for the differences in parent ratings, children in the CFT condition demonstrated a significant increase in their knowledge of the rules of social behavior as well as improved self-concept, suggesting that they did learn socially appropriate behaviors and felt more confident socially as a function of treatment compared to those in the SOC condition. Moreover, parents did not report improvement in their children in all social domains of the SSRS-P, suggesting that they were responding selectively to the various domains assessed by the measure.

Finally, some factors restrict our ability to generalize study findings to larger populations of children with and without PAE. First, it was necessary to work only with children with composite IQs of 70 or above because the treatment required that the children understand the instructions provided during the didactic portions of the sessions. This necessarily limits the generalizability of the study to some children. It is recommended that future interventions consider modifications of the protocol to accommodate children with intellectual disabilities as social skills are extremely important for these children as well to foster more positive social adaptations.

Another limitation to generalization is that the study sample was composed of parents who were actively seeking help for their children and who were highly motivated to participate. Although this may represent a potential limitation with regard to generalization to other children and their families, research shows that the children with and without PAE who have the best treatment outcomes are those who come from stable supportive homes, whose parents are actively involved in their care, and who receive intervention early in life (El Nokali et al., 2010; Streissguth et al., 2004). Given the requirement of parent involvement for the success of the present treatment, we would expect that it is those highly motivated families who would benefit most from this particular intervention.

This study represents a promising intervention for children with PAE who experience multiple failures in social interaction, leading to poor peer choices and, for some, juvenile delinquency. The effectiveness of the treatment was tested on children enrolled in a typical community-based outpatient mental health setting and included children with and without PAE. Given the high rates of mental health problems among children with PAE (O’Connor and Paley, 2009), these children are likely to be seen for treatment in these community settings. Indeed, in the current sample, almost 40% had histories of PAE. Unlike many studies using a wait list control design, the treatment examined here was compared with an active treatment already being used by therapists in the community mental health setting. Given this rigorous test of the treatment protocol, the findings are robust in substantiating the effectiveness of this particular treatment approach. Taken together, the findings from this study suggest that, with specialized training, community mental health practitioners can successfully treat children with PAE and, just as important, these clinicians are receptive to manualized treatment approaches. Furthermore, children with PAE benefit from this treatment approach as successfully as children without PAE. Providing increased access to interventions that have been empirically demonstrated to be efficacious with this population and integrating them into existing programs for children with behavioral disorders is a critical next step toward reducing some of the devastating secondary disabilities faced by children with PAE and in helping their families to promote more adaptive outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Grant Number UDD000041 (MJO, PI). We thank Johanna Walthall, PhD, Marleen Castaneda, and Jennifer Ly for their assistance on this study. Special thanks to Catherine Sugar, PhD, for her help in statistical analyses.

Contributor Information

Mary J. O’Connor, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles California

Elizabeth A. Laugeson, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles California

Catherine Mogil, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles California.

Evy Lowe, Child and Family Guidance Center, Los Angeles, California..

Kathleen Welch-Torres, Child and Family Guidance Center, Los Angeles, California..

Vivien Keil, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles California.

Blair Paley, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles California.

REFERENCES

- Astley SJ (2004) Diagnostic Guide for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: The 4-Digit Diagnostic Code. 3rd ed. University of Washington, Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- Astley SJ (2010) Profile of the first 1,400 patients receiving diagnostic evaluations for fetal alcohol spectrum disorder at the Washington State Fetal Alcohol Syndrome Diagnostic & Prevention Network. Can J Clin Pharmacol 17:132–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black B, Hazen NL (1990) Social status and patterns of communication in acquainted and unacquainted preschool children. Dev Psychol 26:379–387. [Google Scholar]

- Burd L, Selfridge R, Klug M, Bakko S (2004) Fetal alcohol syndrome in the United States corrections system. Addict Biol 9:177–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasnoff IJ, Wells AM, Telford E, Schmidt C, Messer G (2010) Neurodevelopmental functioning in children with FAS, pFAS, and ARND. J Dev Behav Pediatr 31:192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical Power Analyses for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani J (1993) An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall, New York. [Google Scholar]

- El Nokali NM, Bachman HJ, Votruba-Drzal E (2010) Parent involvement and children’s academic and social development in elementary school. Child Dev 81:988–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast DK, Conry J (2004) The challenge of fetal alcohol syndrome in the criminal legal system. Addict Biol 9:161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel F (2005) Parent-assisted children’s friendship training, in Psychosocial Treatments for Child and Adolescent Disorders: Empirically Based Approaches (Hibbs ED, Jensen PS eds), pp 693–715. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel F, Myatt R (2003) Children’s Friendship Training. Brunner-Routledge Publishers, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Frankel F, Myatt R, Cantwell DP, Feinberg DT (1997) Parent-assisted children’s social skills training: effects on children with and without attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36:1056–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel F, Myatt R, Whitham C, Gorospe C, Laugeson EA (2010) A controlled study of parent-assisted Children’s Friendship Training with children having Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 40:827–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelb R, Jacobson JL (1988) Popular and unpopular children’s interactions during cooperative and competitive peer group activities. J Abnorm Child Psychol 16:247–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott S (1990) The Social Skills Rating System. American Guidance Service, Circle Pines, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Guerri C, Bazinet A, Riley EP (2009) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and alterations in brain and behavior. Alcohol Drug Res 44:108–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattie J (1992) Self-Concept. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyme H, May P, Kalberg W, Kodituwakku P, Gossage J, Trujillo P, Robinson LK (2005) A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 Institute of Medicine criteria. Pediatrics 115:39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Smith DW (1973) Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet 2:999–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL (2004) Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test—Second Edition (K-BIT-2). American Guidance Service, Circle Pines, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Kodituwakku PW (2009) Neurocognitive profile in children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15:218–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugeson EA, Paley B, Schonfeld A, Frankel F, Carpenter EM, O’Connor MJ (2007) Social skills training for children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: adaptations for manualized behavioral treatment. Child Family Behav Ther 29:57–69. [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Kalberg WO, Robinson LK, Buckley D, Manning M, Hoyme HE (2009) Prevalence and epidemiologic characteristics of FASD from various research methods with an emphasis on recent in-school studies. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15:176–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee CL, Riley EP (2007) Social and behavioral functioning in individuals with prenatal alcohol exposure. Int J Disabil Human Dev 6:369–382. [Google Scholar]

- Moncher FJ, Prinz RJ (1991) Treatment fidelity in outcome studies. Clin Psychol Rev 11:247–266. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Frankel F, Paley B, Schonfeld AM, Carpenter E, Laugeson E, Marquardt RA (2006b) A controlled social skills training for children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 74:639–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Kogan N, Findlay R (2002) Prenatal alcohol exposure and attachment behavior in children. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26:1592–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, McCracken J, Best A (2006a) Under recognition of prenatal alcohol exposure in a child inpatient psychiatric setting. Mental Health Aspects Dev Disabil 9:105–108. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Paley B (2009) Psychiatric conditions associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15:225–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgaard EC, Fowler RL (2010) Confidence intervals for effect sizes: compliance and clinical significance in the journal of consulting and clinical psychology. J Consult Clin Psychol 78:287–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary CM, Nassar N, Zubrick SR, Kurinczuk JJ, Stanley F, Bower C (2009) Evidence of a complex association between dose, pattern and timing of prenatal alcohol exposure and child behavior problems. Addiction 105:47–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Neville B, Burks VM, Boyum LA, Carson JL (1994) Family-peer relationship: a tripartite model, in Exploring Family Relationships with Other Social Contexts (Parke RD, Kellam SG eds), pp 115–145. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K (1997) Social skills training with parent generalization: treatment effects for children with attention deficit disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 65:749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piers EV, Herzberg DS (2005) Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale. 2nd ed. Western Psychological Services, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C (2005) Executive functioning and working memory in fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:1359–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C, Horne K, Witol A (2006) Neurobehavioral functioning in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Child Neuropsychol 12:453–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebuck TM, Mattson SN, Riley EP (1999) Behavioral and psychosocial profiles of alcohol exposed children. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 23:1070–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Asher SR (1999) Children’s goals and strategies in response to conflicts within a friendship. Dev Psychol 35:69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB (1987) Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Schonfeld AM, Mattson SN, Riley EP (2005) Moral maturity and delinquency after prenatal alcohol exposure. J Stud Alcohol 66:545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton K, Howe C, Battaglia F (eds) (1996) Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention, and Treatment. Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Kogan J, Bookstein FL (1996) Understanding the Occurrence of Secondary Disabilities in Clients with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) and Fetal Alcohol Effects (FAE): Final Report to the Center for Disease Control. University of Washington, Fetal Alcohol and Drug Unit, Seattle. [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Sampson PD, O’Malley K, Young JK (2004) Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr 25:228–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, O’Malley K (2000) Neuropsychiatric implications and long-term consequences of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry 5:177–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren KT, Hewitt BG (2009) Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: when science, medicine, public policy, and laws collide. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15:170–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]