Highlights

-

•

Tackle compliance and accountability versus patient negligence in healthcare.

-

•

Outline and debate existing patient negligence resolution systems.

-

•

Create a quantitative unbiased accountability model to treat patient negligence.

-

•

Guide negligence through suitable resolutions systems based on specific criteria.

-

•

Pinpoint just sanctions against healthcare professionals and institutions.

-

•

Support decisions on fair compensations due to patients.

Keywords: Healthcare, Negligence, Accountability, Litigation, Compensations, Sanctions

Abstract

Being an element of healthcare malpractice, negligence resides as a threat to patient safety, a source of distress to healthcare providers, an economic burden, and an impediment to healthcare improvement. During an age where compliance becomes a necessity, accountability realization remains a hindrance facing the resolution of patient negligence cases. This manuscript intends to create a standardized and well-structured accountability model that tackles patient negligence in healthcare systems. A random sample of 41 hospitals (33 private and 8 public) – representing more than 25% of hospitals in Lebanon – was selected for participation in interviews discussing compliance and accountability against patient negligence in healthcare. Of the selected 41 hospitals, 21 interviews were approved and conducted with hospitals representatives (16 private and 5 public) covering around 13% of hospitals in Lebanon. The formulated model represents an unbiased approach in pinpointing accountability against patient negligence through choosing a suitable resolution system, deciding on sanctions, and determining compensations. Further testing of the model is recommended for verification of its applicability.

1. Introduction

Be it a practitioner from the Hippocratic Greek Era or a sub-specialist in the 21st century; Be it a primitive care house founded by churches or a complex tertiary hospital funded by governments or private sectors; Be it an individual judgment upon the quality of care or an intricate accreditation system; Healthcare has evolved; yet, a basic and fundamental rule hasn’t changed, and it won’t. It’s an axiom beyond doubt, criticism or even debate. The statement “FIRST, DO NO HARM” undoubtedly encompasses the concept of a humane fingerprint to save lives, alleviate pain and illness, and provide patients with good care and quality of life.

To all stakeholders, it is not a choice to “FIRST, DO NO HARM” but rather a prerequisite obligation. Such an expression can be evidenced in the translation of the Hippocratic Oath mentioned by Hulkower (2010) [1]. To achieve so, mankind has developed laws and rules to comply by, and hence, assigned accountabilities upon those who decide and execute actions such as the Hammurabi Code 2030 BCE, cited by Bal (2009) [2]. On the other end of the spectrum, a non-arguable statement looms to rather not oppose but complicate the abidance by the above. It relates to the nature of human beings: “TO ERR IS HUMAN”. No matter how educated, intelligent, and wise a healthcare professional can be, the chance – low or high – to make a mistake is always there even if the supreme aim is to do no harm. In short, errors are the unhappy side of healthcare [3].

This relationship between the above two statements becomes a self-fueled duality where healthcare systems thrive to do no harm and still account for its participants who are expected to err. A proactive approach to ensure compliance and reduce – as much as possible – any potential incidence of an error would employ a risk management mindset. Yet, the focus of this manuscript transcends proactive measures and concentrates on devising a reactive accountability model that treats errors after they happen in an objective and quantitative manner. The model’s aim is to define and regulate necessary resolution systems to process patient negligence cases, hold healthcare professionals and institutions responsible, and compensate patients for experienced harm.

This manuscript is divided into 5 Sections: Background section which tackles a thorough literature review of the topic, Methodology section which discusses adopted research design and sampling, Accountability Model Formulation section which pinpoints the suggested patient negligence resolution model along with proposed measures, Discussion section that comments on model integration within healthcare, and finally a conclusion and future work section to sum up the topic.

2. Background

In order to serve the purpose of designing an accountability model against patient negligence, the state of the art of this paper attempts to sketch patient negligence, describe the patient – healthcare relationship, and further pinpoint compliance and accountability programs.

2.1. Patient negligence

Through evolution, the definition of healthcare malpractice widened its scope from medical malpractice as depicted in Hammurabi’s code to engulf later on and subsequently the realms of Law, Ethics, Finance, and Social Responsibility. Nonetheless, the aim of this manuscript is to concentrate on one type of malpractice, i.e. patient negligence and study its impact upon accountability.

Bal (2009) articulated negligence as the conduct that deviates or doesn’t fully satiate the application of a rule [2]. In addition, Lachs and Pillemer define patient neglect as the event when a healthcare professional flops in attending to the patient needs [4]. In the same article, the World Health Organization’s definition of neglect was also cited as the lack of minimum necessities to handle basic requirements [4]. Reader and Gillespie (2013) came later to refine the understanding of negligence by differentiating between “Procedural Neglect” and “Caring Neglect”. The variance between the two types is the nature of negligence rather than its intent. An example of procedural neglect in a hospital would be not providing a patient his/her meal on time. This is recognized as a breach of a known and documented procedure. On the other hand, an example of caring neglect would be not helping the patient eat when he is in need of someone to aid him. Nonetheless, a caring neglect can become a procedural neglect if done in a repeated manner which would eventually harm the patient [4]. According to the Institute of Medicine, “An error is the failure of a planned action to be completed as intended or the use of a wrong plan to achieve an aim” [5]. Some skeptics say that errors resulting in death are rare. However, reality says differently. According to Kohn and Corrigan (2000), “To Err is Human”. It is the outcome of those errors that patient deaths in the US range between 44,000 and 98,000 per year as a result of medical errors [6].

Categorization of errors involves another four types according to Al Assaf et al (2003); they are [7]:

-

(1)

Diagnostic errors which include a delay or a wrong diagnosis of a patient’s case,

-

(2)

Treatment errors which involve a delayed or an inappropriate element belonging to a procedure to treat patients,

-

(3)

Preventive errors which encompass an absence of or an unsuccessful attempt to prevent a sentinel event or a disease,

-

(4)

Failure errors which describe a healthcare process that crashes down such as communication, equipment, or the system itself.

2.2. Patient - healthcare provider relationship

Historically, there has been an asymmetric power disposition to the provider’s side against the patient in terms of knowledge, problem analysis, and treatment decision making. As a matter of fact, healthcare doesn’t offer a service that is frequently sought out [8]. That is, patients don’t have the luxury to learn from other customers’ feedback on service quality, satisfaction, and criticism. The patient – healthcare provider relationship is also shaped by the mode of communication the healthcare professional adopts whereby it is characterized most of the times as defensive, hierarchal, closed, and confrontational as referenced by Rabinovich-Einy (2011) [9].

Moving towards the event when negligence emerges or is suspected to have happened, the interaction takes an unexpected turn. Where patients seek clarity, transparency and empathy to better apprehend the incident, the majority of healthcare providers adopt the “Deny and Defend” strategy as pinpointed by Boothman et al (2009) [10]. This is due to the fear of facing mad patients/families, be prone to unexpected claims, or even be subject to economic/insurance losses.

A broadminded progressive understanding of patient-practitioner relationship, Mor and Rabinovich-Einy (2012) ridicule views claiming that this relation is affected only in the aftershock of a medical error. Their inclination asserts that healthcare misconduct impacts the whole timeline of the relation from the first day of the encounter until the last day when therapy ends regardless if injury occurs or not. In addition, this can be extrapolated from one patient to a whole society leading to a grave crisis of mistrust between the healthcare system and the community it serves [11].

2.3. Compliance and accountability programs

Arriving at the doorsteps of compliance, two terminologies emerge to serve this understanding. They are compliance and adherence. Researchers have used these two terms interchangeably when the truth is that they are different. Adherence and compliance were cited in a paper titled “Adherence: A Concept Analysis” by Gardner (2015) where she quotes the Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary on both terminologies [12]. Adherence was referred to as the practice through which one sticks or attaches to something. Compliance was represented as the action or course of undertaking what’s requested [12]. The base for both terms is mutual where one actor doesn’t deviate from a something, but Gardner (2015) was able to spot why, through evolution, the term adherence was considerably more utilized than compliance [12]. This is to eliminate the negative connotation of compliance where it may involve coercion and sanctions in case of noncompliance. Such an approach was specified to analyze the adherence of patients to prescribed treatments. Nevertheless, and as a partial disagreement with Gardner (2015) when it comes to the practice of a healthcare professional, the negative connotation of the word “compliance” is of significant value to align practitioners to a certain code of conduct [12]. The use of adherence will only paint a grey zone to the interaction with non-adherence. Another attempt to define compliance was done by Breaux et al (2008) referring to compliance as the capability to sustain a secure stand in a court of law [13]. In addition, they linked the term “compliance” with “due diligence” for an organization or individual to exert adequate endeavors to meet legal necessities [13].

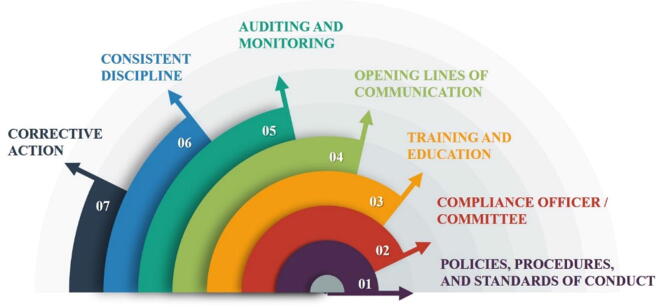

The application of compliance programs, according to a webinar conducted between June 17, 2014 and June 26, 2014 on the Affordable Care Act Provider Compliance Programs describes seven elements of compliance depicted in Fig. 1 [14]. Another reference for compliance programs is illustrated by the International Standardization Organization (ISO) initiative to develop a standard on compliance management. Dee (2008) confirms that management of organizations rush to recognize compliance risks only when disasters occur [15]. For so, he continues to say that an international standard on compliance management would reflect direction to lessen noncompliance [15]. According to Bleker and Hortensius (2014), the origin of compliance is Australia’s national standard AS 8306 [16]. As designated, ISO 19600 will be a guideline rather than a requirement since certifications covering the topic of compliance was covered in previously published standards such as ISO 14001 on Environmental Management and ISO 18001 on Occupational Health and Safety. In addition, ISO 19600 will follow a risk-based model aligned with ISO 31000 on Risk Management [16].

Fig. 1.

Seven Components of Compliance Programs.

In conclusion, substantial proactive efforts are being exerted to formulate a proper and adequate compliance programs/schemes taking into account the inevitability of error-making that engulfs the handling of malpractice, defining accountabilities, and controlling the scopes of healthcare stakeholders’ behaviors, rights and responsibilities to ensure best practice in relevance to what is known and accepted at the current time and place.

The sixth and seventh components (Consistent Discipline and Corrective Action) of the compliance program specifically target the accountability dimension in the case where a certain incompliance occurs. These are the reactive portions that complement the proactive risk management mindset of compliance. According to Brinkerhoff (2003), accountability is a concept of liability of the responsible person/institution and formed of two components: Answerability and Sanctions [17]. Answerability is composed of two questions to be settled: What and Why. Each question refers to a subsequent step in the process. The first query serves the detection of malpractice or close calls. This is related to the effectiveness and efficiency of the upward reporting system within the organization from on-ground activities up the ladder reaching the compliance officer/committee and the downward auditing system from governance to front-liners of healthcare delivery. The why question, on the other end, serves investigation of the event. Similar to Rout Cause Analysis, it is a structured method to pinpoint the event/act/person which or who is responsible for the subsequent malpractice or near-miss. Once Answerability is achieved, a suitable conclusion is formulated where liabilities are assigned through the execution of adequate sanctions upon the convicted person/institution. Sanctions are the measures taken or removed as a sentence relevant to bad behavior or malpractice. Note that, sanctions can include compensation fees, licensure freezing, imprisonment, etc. [17].

Accountability can be categorized as either system (enterprise liability) or individual based. A fierce tug of war exists on how to fairly balance between system and individual responsibilities. Personalized responsibility is the factor that serves to better identify individuals who are expected to defend their activities [18]. Typically, health institutions, if it’s up to their choice, prefer not be accountable for the mistakes done by healthcare professionals attending to their duties within the organization. In other words, hospitals favor a personal accountability approach be exercised upon the physician committing malpractice. Proponents defend this by claiming that they have built a complex healthcare structures that revolve around patient safety. On the other end, professional unions of healthcare practitioners fancy the system-based allocation of liabilities as a form of protection for individuals who are human beings at the end of the day and might do mistakes unintentionally. Advocates claim that a system’s approach has a better shot at mitigation of and recovery from faults [19]. This is also confirmed by Banja (2010), as he criticized the misleading belief that mistakes within the healthcare profession are rooted back to individual wrong doing [20]. He continues to draw a conclusion that disasters in healthcare are the outcome of latent (dormant) errors of the system that allow active (direct) errors of individuals to result in a breach [20]. To wrap it up, both sides, individuals and institutions, should learn that it is their combined responsibility to hold the fire ball of malpractice.

2.4. Negligence resolution systems

This manuscript addresses the need for a standardized and objective accountability model that targets the resolution of patient negligence cases in the healthcare sector. Systems and methods include internal and external healthcare structures that are utilized to compensate patients’ righteous claims, hold healthcare professionals and institutions accountable, and further attempt to treat and proactively lessen the occurrence of such malpractice in the future using a risk management mindset.

2.4.1. Tort law - litigation

The current and most globally applied system to confront malpractice is tort law. Litigation is, without a doubt, a lengthy demanding process that exerts its toll on the plaintiff and the defendant. According to Goldenberg et al (2012), a patient in the United Kingdom has to prove four points for claim consideration [21]:

-

(1)

A healthcare provider had a duty towards a patient.

-

(2)

The obligation in step 1 wasn’t fulfilled or was breached.

-

(3)

The gap in step 2 triggers a damage or injury.

-

(4)

A patient suffered the damage in step 3 as a consequence.

Kessler (2011), on the other hand, pinpointed three points for claims consideration in the United States [22]:

-

(1)

An adverse event was experienced by the patient.

-

(2)

The provider contributed to the event.

-

(3)

Proven negligence on the side of provider was present.

Frivolous lawsuits are a logical and expected outcome. According to Studdert et al (2006), “non-error claims were more than twice as likely as error claims to go to trial”. With the empowerment of patients and the impact of awarded financial compensations, more and more claims are submitted regardless if they are righteous or not. This provides a clear motive for any patient who suffered or even thinks he suffered any damage, even if negligible, due to care delivery to attempt to sue the healthcare provider hoping for a good amount of money in return. Nahed et al (2012) commented on the litigation system saying that it does aid a patient to file a claim against physician’s negligence, but it also opens the window for frivolous lawsuits [23]. Moreover, frivolous lawsuits require a fair amount of resources allocation by every party involved, from courts to attorneys to healthcare providers and even patients [23].

Attorneys’ influence upon the progress of a lawsuit is also a predictable result. Studdert et al (2004) explained that a lawyer acts as the gatekeeper of healthcare lawsuits as he is in charge of moving forward with the process [24]. With the increase of healthcare related lawsuits, attorneys become interested in a niche market characterized by a good opportunity for personal profit. As such, lawyers seek specialization in this type of litigation to become knowledgeable of the dynamics and determinants of healthcare systems. As a result, this bequeaths onto them a drive to study the gaps and exploit them against the defendant on behalf of the plaintiff. Furthermore, lawyers study the cost-effectiveness of each case and are then able to cut down deals with patients on one hand and healthcare providers on the other. Their argument is to alleviate the toll that a litigation system has on both parties [24].

Another perspective concerns willful neglect. To prove it according to a lawsuit case “R v Newington”, Alghrani et al (2011), the court had to prove that a deliberate action was executed by the healthcare professional culminating to maltreat the patient regardless if damage occurs to this latter or not and that the healthcare professional exercised the action/task with a guilt-ridden mind [25].

With the upsurge of trending litigation, healthcare systems were subject to the rise of defensive medicine, lucrative patient awards, frivolous, high malpractice insurance premiums, Attorneys’ manipulation and influence over the progress of malpractice related lawsuits, aggressive behaviors of both patients/relatives and healthcare providers/professionals, reputation damage of healthcare providers/professionals, and anti-quality improvement effects. All this entails an emotional and psychological toll upon both parties through and beyond the litigation process. To enhance tort law based on what has preceded, it has undergone several reforms such as: Statute of Limitations, cited by Lammers (2009), Elimination of res ipsa loquitur, cited by Waters et al (2007), and Caps on damages, collateral source rules and periodic payments [5], [26], [27].

2.4.2. Alternative dispute resolution programs

ADRs, which include, but not limited to, direct negotiation between patients/relatives and healthcare providers/professionals, mediation, arbitration, court based small claims procedures, and court based collective actions for damages, have had their own opponents due to the rigid nature and culture of healthcare, uneven power distribution, and the obvious foreignness of ADRs to healthcare professionals [28]. On the other hand, proponents claim that the application of ADRs will have a positive impact on costs in terms of monetary compensations, dedicated resources, and even time frames. Furthermore, a surge in patient satisfaction proves ADRs have the ability to convert healthcare culture into a more flexible setting to resolve conflicts [28].

2.4.3. Guidelines based system

A guidelines-based system doesn’t change the tort system but rather shifts the point of view of negligence. In other words, a healthcare provider who complied with accepted clinical guidelines would never be considered negligent regardless of the damage. Advocates argue that it promotes the application of evidence-based practice. On the other hand, adversaries see that established guidelines cannot cover the inconsistency of patients’ health circumstances which, sometimes, urge physicians to deviate from a pre-planned protocol to achieve the best outcome.

2.4.4. Enterprise liability

Enterprise liability aligns a healthcare institution to channel the burden of malpractice litigation and its costs from the individual to the organizational level. Kessler (2011) sketched this approach as a means to facilitate the resolution of malpractice in a more efficient way. It’s worth noting that a limited application of this concept has been evidenced [22].

2.4.5. Health courts

A variation of tort law, initiation of health courts specializes in healthcare related lawsuits with dedicated and trained judges or arbitrators. This trend hasn’t had the opportunity yet to thrive; little evidence exists on its efficacy. Some skeptics argue that it imposes some substantial political pressure to adopt it. Nonetheless, it’s a revolutionary approach that needs further research as it might turn out to be the closest it can get to reach a healthcare based and justified court decision.

2.4.6. No fault system

Perhaps, the most controversial replacement of Tort Law is the “No Fault” system which concentrates on compensating a larger section of injured patients with minimal focus on negligence itself. This effort strives to increase the reporting of negligence cases in reference to a no blame, no fault system where healthcare professionals feel more secure towards sharing their mistakes. Learning from slips is the ultimate aim of the “No Fault” system. Nonetheless, this methodology has had a huge share of criticism due to the fact that liability is almost absent. With that in mind, most healthcare professionals would be less cautious, and infrequent mistakes would be more recurrent [8].

3. Methodology

This manuscript employs a qualitative research design. The target population includes public and private hospitals in Lebanon. The rationale behind hospitals being the center of the targeted population is that they are the providers of healthcare. They are at the heart of the compliance and accountability dilemma.

Lebanese hospitals can be categorized as private and public depending on the source of funding. Public hospitals are those which receive funding from the government. Private ones, by elimination, receive funding from nongovernmental parties. It is worth mentioning that all invited hospitals to participate in this study must be licensed and operating. All licensed but non-operating hospitals were eliminated. According to the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), 31 public hospitals were effectively operating at the time. As to private hospitals and according to their syndicate, they amount to 131 operating hospitals at the time. The reference population incorporated the total of 162 hospitals.

To obtain a representative sample of the hospitals, at least 25% of population size is to be taken as a reference. After population stratification according to the below diversification criteria, 41 hospitals were randomly selected and contacted for participation in this study.

Before random selection, the considered population of 162 hospitals has been stratified according to the below diversification criteria which can be categorized as prospective and retrospective. The goal of diversification criteria is to ensure that the approached sample is diverse enough to represent the population. Prospective diversification criteria are taken into consideration during the selection process, while retrospective diversification criteria are only monitored beyond data collection. The first prospective diversification criterion concerns the source of funding of the hospital. A 25% sample of 31 public hospitals suggests the selection of around 8 public hospitals across Lebanon. For private hospitals, a 25% sample amounts to around 33 private hospitals across Lebanon. The second prospective diversification criterion concerns the location of the hospital across different governorates in Lebanon. Lebanon is composed of six governorates: Beirut, Bekaa, Mount Lebanon, Nabatieh, North, and South. At least 5 hospitals (including 1 public hospital) per governorate were randomly selected to ensure a fair representation covering 30 hospitals. The remaining 11 were randomly selected regardless of the governorate. With respect to retrospective diversification criteria, the following factors were considered: number of beds, MOPH accredited vs not accredited, non-profit vs for-profit, university hospital vs non-university hospital, and the average length of stay.

Table 1, Table 2 depict the distribution of the randomly contacted 41 hospitals across prospective diversification criteria along with differentiation of approved participations vs non-approved participations. Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 depict the distribution of the 21 participating hospitals across retrospective diversification criteria.

Table 1.

Participations versus Non-participations per Governorate.

| Governorate | Participations | Non-participations |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejected | No Response | Approved yet not conducted – Time Limitations | |||

| Beirut | 4 (9.76%) | 4 (9.76%) | 2 (4.88%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (24.39%) |

| Bekaa | 4 (9.76%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.44%) | 1 (2.44%) | 6 (14.63%) |

| Mount Lebanon | 5 (12.19%) | 3 (7.32%) | 1 (2.44%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (21.95%) |

| Nabatieh | 2 (4.88%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7.32%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (12.19%) |

| North | 2 (4.88%) | 2 (4.88%) | 2 (4.88%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (14.63%) |

| South | 4 (9.76%) | 1 (2.44%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (12.19%) |

| Total | 21 (51.22%) | 11 (26.83%) | 8 (19.51%) | 1 (2.44%) | 41 (100%) |

Table 2.

Participations versus Non-participations per Funding Source.

| Funding | Participations | Non-participations |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rejected | No Response | Approved yet not conducted – Time Limitations | |||

| Public | 5 (12.19%) | 1 (2.44%) | 2 (4.88%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (19.51%) |

| Private | 16 (39.02%) | 10 (24.39%) | 6 (14.63%) | 1 (2.44%) | 33 (80.49%) |

| Total | 21 (51.22%) | 11 (26.83%) | 8 (19.51%) | 1 (2.44%) | 41 (100%) |

Table 3.

Participations Distribution across Bed Size Classes.

| Number of Beds | Participations |

|---|---|

| 1–100 | 6 (28.57%) |

| 101–200 | 13 (61.91%) |

| 201 and Above | 2 (9.52%) |

| Total | 21 (100%) |

Table 4.

Participations Distribution across Lengths of Stays.

| Length of Stay | Participations |

|---|---|

| Short | 12 (57.14%) |

| Short and Long | 9 (42.86%) |

| Long | 0 (0%) |

| Total | 21 (100%) |

Table 5.

Participations Distribution per University and Non-university Hospitals.

| University Hospital | Participations |

|---|---|

| Yes | 10 (47.62%) |

| No | 11 (52.38%) |

| Total | 21 (100%) |

Selected hospitals were contacted through at least two out of three methods of communication: phone calls, emails and field visits. Hospitals were informed about the topic in question and further offered a confidentiality and anonymity consent form signed by the author along with the questionnaire. Several follow ups were conducted over a period of 45 days with all contacted hospitals. Once participation is approved by the concerned hospital, an appointment for the interview was coordinated. One answered questionnaire per hospital was requested. Interviewees of interest included, but not limited to, Compliance Officers, Medical Directors, Heads of Quality, and any other suggested position/person from the hospital’s side. Beyond day 45 of data collection, gathered information were retrieved and entered in an excel sheet per question per hospital. Hospitals’ and interviewees’ names were eliminated to protect anonymity of the data.

4. Accountability model formulation

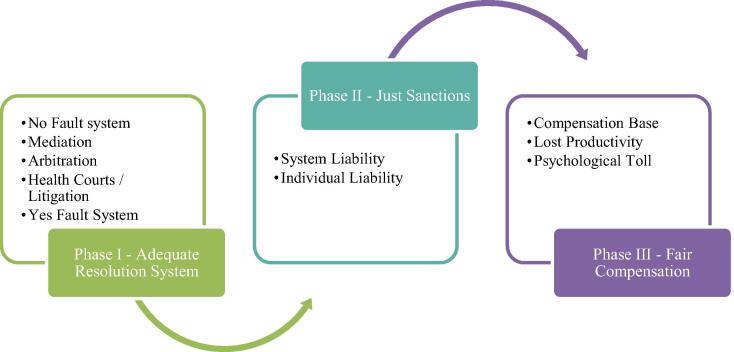

The manuscript’s accountability model to be formulated shall depend on three main phases to reach the sought-out fair application of accountability principles depicted in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Phases of the Formulated Accountability Model.

4.1. Phase I - adequate resolution system

Phase I targets the selection of the adequate resolution system for each particular negligence case. The currently dominant system relies on litigation which is burdened by the number of lawsuits and claims. The logical solution is represented by the attempt to diversify the dependency on multiple resolution systems based on an escalation sequence. This shall spread the management of patient negligence cases over a myriad range of resolution channels. From a proactive point of view i.e. before negligence happens, healthcare systems must have a foundation of guidelines that govern the acceptable performance of healthcare providers where evidence-based medicine is applied with unified protocols and standards. Following so, the reliance on enterprise liability shall channel the burden from the individual level to the system level offering an insurance coverage against malpractice. Such proactive measures shall provide the basis upon which all other reactive resolution systems can operate. From a reactive point of view i.e. after negligence happens, a no-fault system can be embraced provided that it doesn’t result in loose authority and a harboring environment for more errors to occur. As such, its application should be limited to cases where such negative consequences are not induced. Mediation and Arbitration come next where both parties carry their disagreement to a third independent party who shall evaluate the case and issue a ruling. If no agreement arises from mediation and arbitration, litigation based on tort law is always an available option. Nonetheless, the referral to health courts should be a better solution than litigation since it guarantees a more reliable system to reach justice within healthcare contexts. Beyond so, a yes fault system should be created as a symmetrical on the other end of the spectrum opposing no fault systems. The implementation of a yes fault system should be limited to cases where obvious and dire harm is caused by healthcare providers towards patients. With respect to direct negotiation where patients and providers can discuss possible solutions to reach an agreement may indeed cut the time short. However, it is highly unadvised since an imbalance of power exists between the patient and the provider besides its non-systematic nature which won’t guarantee a fair agreement most of the times.

The purpose of formulating this sequence is to develop an escalation chain of resolution systems for patient negligence through which a patient can jump from one system to another. Nonetheless, this escalation should not be loose as the system will suffer from frivolous cases triggering a waste of time, resources and even a negative influence on the healthcare system’s reputation. In this respect, the creation and calculation of an accountability coefficient shall aid in the determination of which resolution system shall be adopted. Based on the conducted interviews with hospitals, the accountability coefficient (AC) is dependent on the event-injury causality (EIC), the injury severity (IS) and the procedure risk (PR). The relation between the accountability coefficient and the event-injury causality and the injury severity is directly proportional. As EIC or IS increases, AC should increase too. As to PR, the relation becomes inversely proportional. Equation (1) depicts the calculation method of AC.

| (1) |

EIC describes the cause-effect relationship between the healthcare provider’s actions and the resulting injury by assigning a rating between zero and ten, where zero means no causal relation, and ten means absolute causal relation. IS describes the intensity of the injury by assigning a rating between zero and ten, where zero means no injury and ten means patient death. PR coefficient describes the degree of risk for the applied procedure/action by the healthcare provider by assigning a rating between one and ten, where one has the lowest risk and ten has the highest risk. The reason why PR does not consider zero on its scale is that no procedure/action within the healthcare context has zero risk. As a result, the scale for AC is zero to hundred. Based on this scale, the reactive resolution systems will be ordered in a way to induce a systematic escalation process through the different systems. The proposed ranges in Table 6 are theoretical. The main purpose is to deliver the idea rather than prove it. As one can observe, the second, third, and fourth ranges are intertwined at their boundaries to allow a more flexible process where several options are available.

Table 6.

Escalation of Resolution Systems Across Accountability Coefficient Ranges.

| AC Range | Adopted Resolution System |

|---|---|

| 0–10 | A no fault system approach is implemented whereby compensations are previously set and subsequently awarded to patients. Sanctions are not allocated because it is an opportunity for improvement |

| 11–35 | A patient has the option has the option to refer his case to a mediator. |

| 20–50 | A patient has the choice to further escalate the process to an arbitrator. |

| 40–80 | A patient has the freedom to go for litigation and health courts. |

| 81–100 | A yes fault system should be implemented. Such a system dictates that the provider should offer a predefined compensation to the patient/family for his/her/their loss regardless of the causality, severity and risk factors. In addition, sanctions are a must and of severe nature which is the exact opposite of the no fault system |

4.2. Phase II - just sanctions

Similar to the above reasoning, the manuscript attempts the formulation of an equation that calculates the sanctions coefficient as a result of discussed factors during interviews: Event-Injury Causality (EIC), Procedure Risk (PR), Incident Preventability (IP), Individual Responsibility (IR), and System Responsibility (SR). With respect to EIC, it has a directly proportional relationship with the sought-out sanctions’ coefficient. As the causality increases, the sanctions should increase due to the tight relation between the event that happened and the resulting injury. With respect to PR, it has an inversely proportional relationship with the sought-out sanctions’ coefficient. As the procedure risk increases, the healthcare provider will be less liable to the sanctions due to the riskiness of the procedure. As to IP, this factor measures the degree to which the occurrence of the negligence was avoidable by assigning a rating between one and ten, where one is barely preventable and ten being absolutely preventable. The third and fourth factors of the sanction’s coefficient are IR and SR. These two variables are considered to be co-dependent in the sense that they belong to the same scale. The idea comes from the fact that no error falls solely on the system or the individual. As such, the scale for the two variables ranges between one and ten, whereby if IR is seven, SR becomes three, and vice versa. Concerning IS, it is not considered in the sanctions’ determination based on the analysis that trivial errors in healthcare can lead to the most severe injuries and devastating errors in healthcare may lead to minimal injuries. As such, the preliminary judgement of the correlation between sanctions determination and injury severity proves to be weak.

Equation (2) and Equation (3) are formulated for the Individual Sanctions Coefficient (ISC) and System Sanctions Coefficient (SSC), respectively.

| (2) |

| (3) |

The range for ISC can be identified through its lower and upper limits. After determining its full range (zero – Nine Hundred), it can be divided into subranges where each subrange dictates a certain level of sanction. The proposed subranges in Table 7 are for demonstration purposes only. Note that, the ranges are intertwined to allow the investigator or the judge to have a margin of choice on the appropriate combination of sanctions. Of course, the frequency of negligence by the same individual is a vital indicator to level up the sanction even if it falls within a lower range. For example, if a nurse receives a sanction coefficient between seventy-five and two-hundred, an oral notification is delivered and a retraining session is arranged. If a second negligence case is repeated by the same nurse, a written warning is applied even if the incident still falls within the first range.

Table 7.

Escalation of Individual Sanctions Across Sanctions Coefficient Ranges.

| ISC Range | Adopted Sanctions |

|---|---|

| 0–100 |

|

| 75–200 |

|

| 150–300 |

|

| 250–400 |

|

| 350–500 |

|

| 450–700 |

|

| 650–900 |

|

With respect to healthcare institutions, SSC ranges should also be formulated with increasing strictness to fit similarly assigned subranges based on the previously presented equation (3). Suggested sanctions include, but not limited to, notifications, fines, certification or accreditation withdrawal, etc.

4.3. Phase III - fair compensations

To calculate the monetary compensation to be paid, the following components need to be considered as per the findings of the conducted interviews: Remedy Compensation (RC) portion, Lost Productivity (LP) portion, and Psychological Effect (PE) portion.

With respect to the remedy compensation portion, the conducted interviews showed that the calculation of a compensation coefficient (CC) relies on four factors: Event-Injury Causality (EIC), Injury Severity (IS), Incident Preventability (IP), and Procedure Risk (PR). These factors follow the same rules and proportional relations whereby EIC, IS, and IP are directly proportional to CC and PR is inversely proportional to CC. Equation (4) depicts the calculation of CC.

| (4) |

To get RC, CC is multiplied by a base monetary value (BMV) to be agreed upon or bestowed based for each country. For example, the base value can be assumed to be a constant such as a hundred USD across any negligence case or variable depending on the case. For instance, a death case might have a BMV of a thousand USD, while a treatable surgery complication might have a BMV of fifty USD. The decision to pinpoint a fixed BMV or a variable BMV requires model testing and comparison of results to know which method is fairer given the economic situation in each country. Equation (5) depicts the calculation method of RC.

| (5) |

With respect to lost productivity (LP), the interviews findings show a dependency on the following variables: Period of Incapacity (PoI), Number of Dependents (NoD), and average Cost of Living per Day per Capita (CoL). Equation (6) conveys the calculation method of lost productivity.

| (6) |

The remaining factor is the Psychological Effect (PE) which proved to be hard to quantify. Nonetheless, the literature provides certain dimensions and/or tools to address such as the Quality of Life Questionnaire [29], the measurement of psychological wellbeing [30], or the measurement of happiness [31], [32]. The idea is to measure the difference in the psychological state of the patient before and after the incidence in order to decide a monetary amount to compensate this factor. This factor is kept flexible for subjective decision making by the responsible person and on a case by case basis.

The accumulation of all these components in Equation (7) results in the sought out Total Compensation (TC) due to the side of the patient.

| (7) |

5. Discussion

Unescapable is not a true attribute of errors; yet, one cannot, with absolute certainty, nullify the probability for them to occur. It’s very important to assert that errors can be avoided for if they weren’t, the motive to reduce their occurrence can no longer survive. What’s alarming about negligence is the healthcare system’s perception of its risk. Cook (1998) cited by Banja (2010) exclaims about the notion of an “acceptable” risk [20], [33]. It is widely acknowledged that healthcare participants do not practice their profession with an intent to commit an error or willfully and knowingly neglect patient care. Nevertheless, it’s inappropriate and unwise to blindly believe that not one healthcare professional would commit or be obliged to commit such an act. What matters is that negligence can be caused by unintentional errors, willful neglect, and any notion spanning the distance between the two terminologies.

To address the skepticism around the risks and effects of negligence, take a surgeon’s error where he/she doesn’t cause death of a patient but cuts the limb of the wrong patient. Consequences upon the severed person will include physical harm that will entail an emotional complex. In addition, the patient will lose at least part of his/her functionality to meet his/her needs, to act as an active member of his/her family and society, and to be a productive person on the professional level. Consequences on the family would also encompass an emotional toll to cope with the new condition and adapt to the needs of this challenging state. More pressure to achieve vital life necessities to cover the gap that the injured patient will leave. Every Healthcare professional that participated in this error will suffer less confidence in his/her work. At least part of the healthcare professional’s work environment will point fingers to promote the feel of guilt. Regardless whether such a culture promotes patient safety or not, it is a raw evidence about the seriousness of the error. And yet, one shouldn’t forget the monetary compensation to correct what happened and provide the patient with the best remedies and treatments over a not-so-short period of time. All in all, the toll that negligence leaves on healthcare stakeholders is way more expensive and tougher than finding ways to avoid it.

Regardless of the ethical, financial, medical, legal and social implications of patient negligence, it’s a manifestation of incompliance with the Hippocratic Oath’s ultimate promise to First Do No Harm. Any breach of this rule should proactively be monitored from a risk management point of view to ensure an acceptable level of compliance and should reactively be dealt with to ensure a fair level of accountability. The topic of compliance and accountability is of paramount importance in healthcare systems since it presides at the overlap between the duality of First Do No Harm and To Err is Human. The articulation of compliance initiatives and guidelines is rendered incomplete if not coupled with a just accountability model.

With respect to the model’s shortcomings, opponents might argue that a quantitative approach is not the subtlest way to tackle sensitive topics such as patient negligence and healthcare accountability. Furthermore, a case by case assessment is imperative to have the fairest ruling whereby decision makers have an input based on their perceptions and comprehensive understanding of the situation rather than following numbers and calculations. This allows for a more flexible range of options and styles to treat the case. To argue against such views, proposing an objective quantitative model to set an escalation sequence of patient negligence resolution systems, just sanctions, and fair compensations addresses tensions between patients and healthcare systems in a systematic and unbiased manner. Furthermore, it shall reduce costs of litigation, save time, and emotionally unburden both healthcare professionals and patients as well. Despite its pragmatic methodology, this model aims at reducing decision making errors and biases. Again, the coupling of compliance and accountability won’t serve as a hundred percent assurance that no malpractice occurs. However, its beauty lies within the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) concept passed onto us by Deming. It’s a motive to think, execute, check, correct then learn and improve, and so on.

6. Conclusion and future work

Collaboration is the key to success. All healthcare stakeholders, without exception, are invited and urged to pull every possible effort to cause an imbalance between the discussed duality between “To Err is Human” and “First, Do No Harm” towards the latter. The testing, tweaking, and further adoption of the suggested model by healthcare systems shall prove the viability of this approach to serve an enhanced level of compliance and accountability in healthcare. This study opens the gate in front of fellow researchers, through qualitative and quantitative studies, to build upon it, negate its outcomes where possible, or test the suggested models/formulas for applicability. Qualitative studies may follow to elaborate more on the subject in order to fixate the understanding of compliance and accountability in healthcare. Quantitative studies may handle the statistical testing of the suggested model along with its equations to assess its viability. A pilot study coupled with a comparison between its results and real-life situations shall better sketch the reliability of this model in treating patient negligence cases.

The realization of limitations remains a cornerstone for future work and efforts. The author’s bias in this dissertation may be detected and accounted for in two phases. The first phase is the interview process whereby the author is an interacting party in the conduction of the interview. As such, this interaction, despite the author’s will and effort to try to be as much objective as possible, has the potential to hold a small percentage of bias. The second phase is the analysis part whereby the author analyzed open ended questions according to his own perception of the supplied answers. It’s not a secret that perceptions of information may vary from one person to another. On the other end of the spectrum, the interviewee’s bias cannot be overridden. Not all interviewees shared the same positions and expertise. This is a key element when it comes to weighing the depth of supplied answers. Furthermore, not all interviewees – even in case of similar roles and experience – have the same perception to the subject under study.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tarek Moukalled: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Ali Elhaj: . : Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Hulkower R. The history of the Hippocratic Oath: outdated, inauthentic, and yet still relevant. Einstein J Biol Med. 2016;25(1):41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bal B.S. An introduction to medical malpractice in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(2):339–347. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0636-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greco P.M. To err is human. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2015;147(2):165. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reader T.W., Gillespie A. Patient neglect in healthcare institutions: a systematic review and conceptual model. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):156. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Studdert D.M., Mello M.M., Gawande A.A., Gandhi T.K., Kachalia A., Yoon C., et al. Claims, errors, and compensation payments in medical malpractice litigation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(19):2024–2033. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa054479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohn L.T., Corrigan J., Donaldson M.S. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2000. To err is human: building a safer health system; p. 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Al-Assaf A.F., Bumpus L.J., Carter D., Dixon S.B. Preventing errors in healthcare: a call for action. Hospital Topics. 2003;81(3):5–13. doi: 10.1080/00185860309598022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danzon P.M. Liability for medical malpractice. J Econ Perspect. 1991;5(3):51–69. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rabinovich-Einy O. Escaping the shadow of malpractice law. Law Contemp Probl. 2011;74(3):241–279. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boothman R.C., Blackwell A.C., Campbell J.D., Commiskey E., Anderson S. A better approach to medical malpractice claims? The University of Michigan experience. J Health Life Sci Law. 2009;2(2):125–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mor S., Rabinovich-Einy O. Relational malpractice. Seton Hall Law Rev. 2012;42(2):601–642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardner C.L. Adherence: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Knowl. 2015;26(2):96–101. doi: 10.1111/2047-3095.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Breaux T.D., Antón A.I., Spafford E.H. A distributed requirements management framework for legal compliance and accountability. Comput Secur. 2009;28(1–2):8–17. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Affordable Care Act Provider Compliance Programs: Getting Started Webinar; 2014. [PowerPoint presentation]. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNEdWebGuide/Downloads/MLN-Compliance-Webinar.pdf [accessed on 03 January 2021].

- 15.Dee B. Compliance programmes - a roadmap to accountability. ISO Focus: The Magazine of the International Organization for Standardization. 2008;5(3):33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bleker-van Eyk S.C., Hortensius D. ISO 19600-The development of a global standard on compliance management. Bus Compl. 2014;2014(2):3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinkerhoff D. The Partners for Health Reformplus Project, Abt Associates Inc; Bethesda, MD: 2003. Accountability and Health Systems: Overview, Framework, and Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renkema E., Broekhuis M., Ahaus K. Conditions that influence the impact of malpractice litigation risk on physicians’ behavior regarding patient safety. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):38. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glance D.G. A systems approach to accepted standards of care: Shifting the blame. Austral Med J. 2011;4(9):490. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banja J. The normalization of deviance in healthcare delivery. Bus Horiz. 2010;53(2):139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldenberg S.D., Volpé H., French G.L. Clinical negligence, litigation and healthcare-associated infections. J Hosp Infect. 2012;81(3):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler D.P. Evaluating the medical malpractice system and options for reform. J Econ Perspect. 2011;25(2):93–110. doi: 10.1257/jep.25.2.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nahed B.V., Babu M.A., Smith T.R., Heary R.F. Malpractice liability and defensive medicine: a national survey of neurosurgeons. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Studdert D.M., Mello M.M., Brennan T.A. Medical malpractice. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(3) doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr035470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alghrani A., Brazier M., Farrell A.M., Griffiths D., Allen N. Healthcare scandals in the NHS: crime and punishment. J Med Ethics. 2011;37(4):230–232. doi: 10.1136/jme.2010.038737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lammers S.P. Recent Developments in Medical Malpractice. Indiana Law Rev. 2010;43(3):855–872. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waters T.M., Budetti P.P., Claxton G., Lundy J.P. Impact of state tort reforms on physician malpractice payments. Health Aff. 2007;26(2):500–509. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stuyck J, Terryn E, Colaert V, Van Dyck T, Peretz N, Hoekx N, et al. An analysis and evaluation of alternative means of consumer redress other than redress through ordinary judicial proceedings Final Report. Final report, The Study Center for Consumer Law-Center for European Economic Law, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium; 2007.

- 29.Cohen S.R., Mount B.M., Strobel M.G., Bui F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: a measure of quality of life appropriate for people with advanced disease. A preliminary study of validity and acceptability. Palliat Med. 1995;9(3):207–219. doi: 10.1177/026921639500900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryff C.D., Singer B. Psychological well-being: Meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychother Psychosom. 1996;65(1):14–23. doi: 10.1159/000289026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linley P.A., Maltby J., Wood A.M., Osborne G., Hurling R. Measuring happiness: The higher order factor structure of subjective and psychological well-being measures. Personality Individ Differ. 2009;47(8):878–884. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hills P., Argyle M. The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: a compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality Individ Differ. 2002;33(7):1073–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cook RI. How complex systems fail. Cognitive Technologies Laboratory, University of Chicago. Chicago IL; 1998. Available Online: https://cache.chrisshort.net/file/cache-chrisshort-net/How-Complex-Systems-Fail.pdf [accessed on 03 January 2021].