Abstract

Introduction

Comprehensive national non-communicable disease (NCD) policy development and implementation are crucial for preventing and controlling the increasing NCD burden, particularly in the Africa region where the largest increase in NCD related mortality is expected by 2030. Yet, even where national NCD policies exist, effective implementation remains hindered for reasons not clearly elucidated. This study explored the experiences of key health stakeholders at national and sub-national levels with implementing a national NCD policy in Ghana.

Methods

This was an explanatory, cross-sectional and grounded theory study using in-depth interview guides to collect primary data from 39 purposively sampled health policymakers and implementing officials at the national and sub-national levels in Ghana. A thematic approach was used in data analysis.

Results

Several interwoven factors including poor policy awareness, poor coordination and intersectoral engagements and inadequate funding for NCD programs and activities are key challenges thwarting the effective implementation of the national NCD policy in Ghana. At the sub-national levels, inadequate clarity and structure for translating policy into action and inadequate integration further affect operationalizing of the national NCD policy.

Conclusion

The findings call for policymakers to adopt a series of adaptive measures including sustainable NCD financing mechanisms, effective intersectoral coordination, policy sensitisation and capacity building for implementing health professionals, which should be coupled with governmental and global resource investment in effective implementation of national NCD policies to make sustained population level gains in NCD control in Ghana and in other resource constrained settings.

Keywords: NCD policy implementation, perceptions and experiences, implementation bottlenecks, Africa, Qualitative study

Highlights

-

•

Africa's NCD policy responses remain poor for reasons that are not clearly elucidated.

-

•

Explorative analysis of Ghana's NCD policy implementation shows several interconnected challenges.

-

•

Poor awareness, inadequate intersectoral coordination and funding are national-level challenges.

-

•

Difficulties translating policy strategies and with integration influence subnational level operationalisation.

-

•

Adaptive measures surrounding funding, coordination and capacity building are crucially needed.

1. Introduction

Comprehensive non-communicable diseases (NCDs) policy implementation is crucial for the prevention and control of NCDs particularly in the Africa region where NCDs are expected to account for about 46% of all mortality by 2030 [1,2]. Yet, despite committing to the World Health Organisation (WHO) Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020 [3], evidence shows that the African region made limited NCD policy progress towards achieving the indicators by the set deadlines of 2015 and 2016 [[4], 5., 6.].

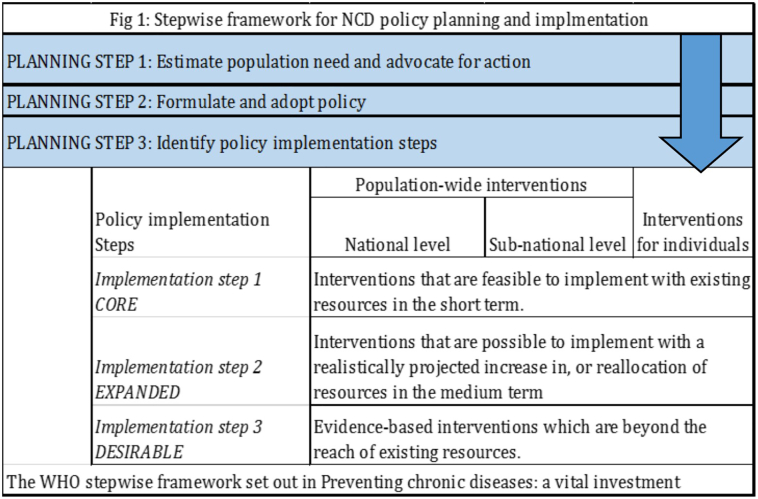

Like other African countries, Ghana faces a growing NCD burden [7., 8., [9], [10]] that, coupled with a prevalent burden of communicable diseases, compound an already fragile health system. Key NCD policy responses over the last two decades have included; the institution of the NCD Control and Prevention Programme (NCDCP) in 1992 by the Ministry of Health (MoH) to design, coordinate, mobilise and implement key NCD prevention and control strategies [7]; a draft national NCD policy in 2002 [7]; the establishment of the Regenerative Health and Nutrition Programme (RHNP) in 2006 [7,11]; and the inclusion of key medicines for some NCDs into the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) [11]. In line with WHO's stepwise framework (Fig. 1) for the prevention and control of chronic diseases [12], the 2002 draft national NCD policy was adopted with few modifications as national policy in 2012 [7]. The key objectives of the national NCD policy include reducing a) the incidence and prevalence of chronic NCDs b) exposure to risk factors c) NCD related morbidity and d) improving the overall quality of life for persons with NCDs [13]. Adopting a life course approach, the NCD policy utilises an integrated approach focusing on health promotion, early detection and clinical care, health system strengthening and surveillance of NCDs and risk factors among others [13].

Fig. 1.

Stepwise framework for NCD policy planning and implmentation.

With evidence showing limited NCD policy response progress and increasing NCD related mortality from 42% of all deaths in 2012 to 44% of all deaths in 2015 [5,14], the implementation of the national NCD policy is urgently needed to reduce NCD related premature morbidity and mortality. Yet, policy implementation is a complex process influenced by several interwoven factors. A prior review of NCD policy response documents shows that Ghana's NCD policy planning and implementation process is riddled with challenges such as lack of political interest and inadequate funding [7]. While the adoption of the national NCD policy is a key step towards the prevention and control of NCDs, there is scant evidence on its operationalisation and implementation challenges particularly from the experiences of health policymakers and health officials tasked with implementation at the national and sub-national levels. This is key evidence needed to inform NCD policy implementation progress as studies show that achieving the objectives of national policies are often mired by implementation difficulties particularly at the operational level [15,16]. This study explored the perceptions and experiences of key health policymakers and implementers at the national and subnational levels in Ghana regarding the implementation of the national NCD policy.

2. Materials and methods

This explanatory qualitative research study followed the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (Supplementary File 1) and was conducted between March and June 2017. Individual interviews using open-ended topic guides exploring perceptions and experiences [17] were conducted with purposively sampled national, regional and district level health stakeholders involved in NCD policy formulation and implementation in Ghana. Formal letters were submitted to relevant institutions outlining the purpose of the research and inviting pre-identified officers to participate. The first author followed up physically at offices and/or electronically through email or phone calls to meet and schedule interview dates after institutional permission was granted. Invited officers received both an information sheet and verbal information about the study and interviews were conducted in their offices. We were unable to schedule meetings with three identified health officers at the national and regional levels because they were unavailable during the study period. The first author, who has nearly a decade of qualitative research experience conducted all the interviews in English using a topic guide developed by the authors, which allowed for further exploration of emerging thems with interview time ranging from 30 to 65 minutes per interview. The topic guide developed by authors was informed by a review of NCD policy literature in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) and Ghana specifically and authors'contextual research experiences. We sought written and verbal consent from each participant before collecting data in the form of digitally recorded audio files.

As data saturation is the main criteria for sampling in qualitative data [18,19], a sample of 15 national level policymakers and 24 implementing health officers at the regional and district (sub-national) levels was sufficient to reach data saturation in this study. Because all national institutions including the Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Ghana Health Service (GHS) are headquartered in Accra, the national capital, 10 interviews were conducted with policymakers, three with national NCD program representatives and two with focal persons in international health organisations. These interviews focused on their perceptions regarding the national NCD policy and it's associated implementation. Quotes from these interview transcripts are labelled PM.

Interviews were also conducted in three locations at the sub-national levels; Kumasi in the Ashanti Region, Tamale in Northern Region (NR) and Bolgatanga in Upper East Region (UER). Kumasi was selected because it houses the second-largest hospital in Ghana and is a tertiary referral hospital for five regions while in northern Ghana, Tamale and Bolgatanga were purposively selected based on population size, poverty and literacy profiles. Interviews were conducted with three national, 12 regional and nine district level health officers, which focused on experiences and factors influencing the implementing the NCD policy at regional and district levels. Quotes from interview transcripts from Kumasi are labelled SG-PA and transcripts from northern Ghana are labelled NG-PA. The study received ethical approval from the Ghana Health Service Ethical Review Services (GHS\ ERC) numbered GHS-ERC 09/01/201 and administrative consent from the three regional health directorates.

Data analysis was conducted with QRS Nvivo Pro version 11.0 using an inductive thematic approach [20,21]. Two research assistants transcribed the audio interviews verbatim into Microsoft Word documents and the first author reviewed, coded and analysed all transcripts in constant comparison. Using a thematic approach, the initial coding framework was generated by the first author using the key themes contained in the topic guide. Data were triangulated to identify and compare commonalities and differences from multiple stakeholders. The coding framework was reviewed with co-authors and broadened to include open-ended inductive and deductive codes. To ensure credibility and consistency, patterns and linkages were explored and interpreted by the first author, which were revised with co-authors. To ensure external validity and generalizability, we compared the study findings with existing literature and models of health policy implementation processes in SSA. Emphasis was placed on practical and structural factors influencing the effective implementing of the national NCD policy at the regional and district levels. Themes and codes were recoded and recategorised after co-authors reviewed the revised coding framework, which guided data analysis and writing.

3. Results

Table 1 and Supplementary File 2 present the background characteristics of study participants and additional supporting quotations in line with the themes and sub-themes respectively.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of study participants.

| Characteristics | Policy makers (n = 15) | Implementing participants (n = 24) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Ghana N = 9 | Northern Ghana N = 15 | ||

| Age range | 35–55 | 30–56 | 28–54 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 10 | 7 | 12 |

| Female | 5 | 2 | 3 |

| Level of education | |||

| First degree | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| Masters | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| PhD | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Organisation | |||

| Ministry of Health | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| NCD Control and Prevention Programme | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Regenerative Health and Nutrition Program | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| International Health organisations | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Ghana Health Service (GHS) - National | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| GHS (Regional Health Directorates) | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| GHS (District Health officers) | 0 | 2 | 9 |

3.1. Perceptions and current achievements of the national NCD policy

All participants perceived the national NCD policy as a crucial framework for guiding and coordinating all NCD prevention and control activities in Ghana but added that several factors account for the slow policy implementation progress.

“It's one thing to have a policy and another thing for it to see the light of day… the NCD policy is not being implemented so well because between policy and implementation, there are gaps and the reasons for that will be multi-factorial.”

SG-PA-08

Regarding current achievements of the national NCD policy, some policymakers reported that a draft implementation work plan had been developed in collaboration with the national NCD control and prevention programme. Other policymakers added that a draft alcohol policy is currently in the process of been legalised. Implementers in northern and southern Ghana reported the institutionalisation of specific clinic days for some selected prevalent NCDs at selected regional and district health facilities and the creation of NCD focal persons at regional health directorates (Supplementary File 2A).

“We have the alcohol policy, which we just launched…. the next step is to legalize it and, extend it to ELI be a legislative instrument.”

GA-PM-01

“[W]e have a focal person for NCDs for the region as the policy indicates and some special NCD clinics in some of the health facilities…”

SG-PA-01

3.2. Factors influencing the implementation of the NCD policy

3.2.1. Low awareness of the national NCD policy

Participants reported a low awareness of the NCD policy particularly among regional and district level implementing health authorities, which was attributed to poor NCD policy dissemination at the sub-national levels (Supplementary File 2B.1). In northern Ghana, implementers attributed the low NCD policy awareness to a top-down approach to information sharing with the policy dissemination activities focused at the national level.

“These policies don't trickle down to the grassroots so implementation will be poor. They are formulated there and people who will implement it here don't know… All the policies are made and kept in Accra… during the launch, if it gets media attention, we get to know more about it … it remains at the higher levels”

NG-PA-01

Implementers in northern Ghana called for increased dissemination of the policy strategies at subnational implementing levels while implementers in southern Ghana called for capacity building for implementing health professionals on the NCD policy strategies. Policymakers further called for committed NCD leadership and suggested that NCD advocacy champions could potentially increase awareness about the NCD policy and galvanise support for its implementation (Supplementary File 2B.1).

“Policy should also begin from the bottom. It should not always be a top-down approach … they should make sure to disseminate them so the staff implementing it will understand the policy and the strategies and know-how to integrate it at their level, … If those who work with the patients don't know it, how will the control improve?”

NG-PA-01

3.2.2. Inadequate clarity and structure for translating policy into action

Linked to low NCD policy awareness, participants added the lack of clarity and structure of the NCD policy, which they reported hinders effective translation into actionable interventions for effective implementation. Policymakers emphasised the lack of a comprehensive implementation guideline and monitoring framework to structure the implementation of the NCD policy strategies. Sub-national implementers, particularly in southern Ghana, reported that the NCD policy lacked clarity on proposed strategies to facilitate translation into actionable implementation activities (Supplementary File 2B.2).

“It is not clear… It is just giving general direction but what will I do with it as a practitioner?. It is good, like in the books but how do we make it into real actions? It doesn't have like clear target populations and what interventions for what type of people. No regional or district action plans you see? And if it is not clear, how can we translate to programs? We only have clinics in some hospitals to provide services for NCDs.”

NG-PA-06

3.2.3. Prioritisation of communicable diseases and challenges with integration

Participants reported that NCD focal persons have been instituted in regional health directorates as part of the NCD policy implementation. Implementing sub-national participants in northern and southern Ghana added that because the health system still prioritises communicable diseases and focuses on clinical care for persons living with NCDs, NCD focal persons are not adequately resourced to undertake any policy implementation programs for NCD prevention. Policymakers attributed the focus on communicable diseases to donor interests while implementers in southern Ghana attributed the communicable disease focus to a lack of awareness of the long term implications of uncontrolled NCDs on the health system and developmental efforts. Implementers in northern Ghana attributed the focus on communicable diseases to the higher prevalence of communicable diseases in their regions (Supplementary File 2B.3).

“The donors are interested in the communicable… TB, malaria and HIV/AIDS have a lot of funding so the health system is focusing on that because that is what donors will fund and they are prevalent… integrating NCDs is difficult because the donor funds specific items and there is no money for NCDs so the integration is hard because of reporting to the donors… so if NCDs are not backed with financial support, it is indirectly telling you that, it's not a priority.”

GA-PM-07

All implementers reported attempts at integrating NCDs into routine health system activities such as the institutionalisation of hypertension and diabetes clinics days at regional hospitals and selected district health facilities (Supplementary file 2B.3). Implementers in southern Ghana further reported periodic intervention program for prevalent NCDs such as using selected pharmacies/drugstores for providing healthcare for persons living with hypertension, NCD training for selected health professionals and establishing coordinated health teams to provide healthcare for persons living with NCDs with shared behavioural risk factors.

“The infectious diseases are still taking a chunk of our time… NCDs, the focus is more on the management, not prevention… We are trying to integrate NCDs at the primary care level so we can identify and start management early as the policy indicates but no resources… we trained teams to run clinics for people to manage diet-related issues … screening for NCDs is said in the policy so we did some screening with the churches…we also tried the New Model of Care, where people were checking their BP at pharmacies so we are trying”

SG-PA-01

3.2.4. Inadequate funding for NCD policy implementation

All participants reported inadequate funding for NCD policy implementation resulting from a lack of clearly stated funding sources as a key implementation bottleneck. They perceived this to be due to the lack of an allocated government budget to guide the NCD policy implementation process and the lack of global funding support for NCD prevention and control activities. Implementers at the sub-national levels in northern and southern Ghana further reported the untimely release of health funding to the regional levels and the lack of resources for regional level NCD focal persons as key contributors to the poor NCD policy implementation at the sub-national level (Supplementary File 2B.4).

“If you want to implement the policy, you have to send the funding for the work to be done. Why don't you have a budget for implementing the policy? NCDs, nobody gives funding so no budget for the NCD focal person…national health insurance does not cover medical screening, some tests and drugs… public screening is expensive… financing are not clearly stated in the policy”

NG-PA-03

“If you don't have funds, you can't implement a policy. The NCD policy implementation is supposed to be funded by our GoGs… once donors show interest in NCDs, the health sector too will prioritise it and the policy implementation.”

GA-PM-07

3.2.5. Poor coordination

Poor coordination between the policy and service delivery arms of the health sector and poor intersectoral coordination between the health sector and other relevant sectors were frequently reported by participants as key implementation bottlenecks. Policymakers attributed this to the lack of committed national level leadership to coordinate intersectoral activities and emphasised this hinders leveraging on sector-wide opportunities for addressing behavioural risk factors using the life course approach to facilitate behavioural modifications, which is a key objective of the NCD policy (Supplementary File 2B.5). Implementing sub-national participants attributed the poor coordination between health policy and service delivery to the lack of clearly drawn structures and processes to facilitate coordination between health policy and service delivery. Implementing participants in southern Ghana further stressed the lack of coordination between professionals working in public health and clinical care and within NCD programs and interventions as key bottlenecks to effective implementation of the NCD policy (Supplementary File 2B.5).

“The way the policy is, you need broader collaboration with sectors like education, agric or roads… but they are all territorial so you need to set up the structure with clear outputs and deadlines and who should do what… we cannot increase physical activity when there aren't even places for people to exercise…We can't get school children to do it or diet if it's not being taught in school...the sectors talk on paper like the way the policy says life course approach but if we want to make progress for NCDs, they need to work together for peoples' behaviour to change ”

GA-PM- 04

3.2.6. Inadequate human resource and expertise

Participants reported inadequate human resources for health and limited capacity on NCDs among health providers for providing clinical care for NCDs particularly in northern Ghana. They elaborated that effective implementation of the policy strategies surrounding public sensitisation and screening for NCDs requires that health workers have the knowledge and capacity to identify, diagnose and manage NCDs, their complications and co-morbid conditions (Supplementary File 2B.6).

“One of the difficulties is shortages in human resources and capacity… they are mostly trained for communicable diseases… Health workers have little training on NCDs, which has implications for public sensitisation and screening… women come and the BP is rising and the one [health worker] checking will not know… because they have difficulty understanding the meaning of the BP readings, …the quality of some lower non-medical staff is not that good.”

SG-PA-02

Implementers, particularly in northern Ghana urged the need to incorporate capacity building for screening, diagnosing and management of NCDs into the training curriculum for pre-service health workers as the best strategy for building health providers capacity and expertise for achieving the NCD policy objectives (Supplementary File 2B.6).

“I think that it [NCD policy] should be taught in the training schools so that by the time they pass out, they already know about it … health worker shortages here, time to learn more about these policies after school is not there so we need to emmm ‘catch them young’ [in-school training] and give them orientation on NCDs and the policy.… that's the way to get them trained.”

NG-PA-02

3.2.7. Inadequate surveillance of NCDs and poor data quality

Participants from disease surveillance departments reported that they currently capture some prevalent NCDs but added that data quality is poor, which hinders accurate assessment of NCDs and risk factors to inform effective implementation of the policy strategies. Policymakers attributed this to the poorly equipped and underfunded diseases surveillance system while implementers added structural factors such as poor internet connectivity and access to electricity as key contributors (Supplementary File 2B.7).

“It is recently in 2011… major ones like diabetes and hypertension are under surveillance but data quality is not that good…the annual or biannual surveys where we can get data on risk factors are very capital intensive and supported by WHO so if they don't give funding it is difficult.”

GA-PM-08

4. Discussion

Evidence shows that having a national NCD policy is a crucial framework for the prevention and control of NCDs in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) [22]. Yet, in the African region where the greatest NCD related mortality is expected by 2030 and health systems are poorly equipped to handle the increasing NCD burden, implementation of globally recommended NCD policy responses has been slow for reasons that are not clearly elucidated [1,6,23]. Ghana adopted a national NCD policy in 2012 yet, there is scant evidence on Ghana's national NCD policy implementation progress and bottlenecks. The findings contribute contextual evidence on factors influencing the effective implementation of the national NCD policy drawing from the experiences of health policymakers and implementers at the national and sub-national levels in Ghana. While the inclusion of some NCDs into disease surveillance, the institution of regional level NCD focal persons and the draft alcohol policy are key achievements in line with the NCD policy strategy, several interconnected factors including low policy awareness, inadequate clarity and structure and poor coordination facilitate the slow implementation of the NCD policy in Ghana. The insights presented have the potential to inform NCD policy implementation efforts not only in Ghana but potentially in other SSA countries with similar contexts.

The findings show a poor awareness of the NCD policy at the sub-national levels, particularly in northern Ghana where poverty is endemic, making people more vulnerable to NCDs. While other studies have reported poor awareness at the operational level as a barrier to national health policy implementation in Africa [24,25], this finding challenges the inherent assumption that implementing stakeholders would have a high level of awareness of the NCD policy directives. The situation is compounded by the inadequate clarity and structure of the national NCD policy, which hinders the translation of the policy strategies into implementation activities at the sub-national levels. Despite a key NCD policy focus on health promotion, early detection and clinical care, at the sub-national implementing levels which could have larger population level impact, fewer NCD activities are undertaken to sensitise and improve screening, diagnosis and management of NCDs because implementers are unaware or at most, do not clearly understand the policy strategies. The consequences are particularly grave in northern Ghana where an understaffed, under-resourced and inaccessible health system grapples with healthcare delivery in a relatively more rural context that records the highest poverty and illiteracy rates nationally [[26], [27], [28]]. It is evident that without increased awareness, familiarity and clarity of the NCD policy strategies at the implementation levels, NCD sensitization programs would result in little NCD prevention and control improvements at the population level and further compound an overburdened health system. To further enable structure and clarity regarding the national NCD policy, it is key that a coordinated implementation guideline and monitoring framework be developed to guide the implementation process. It is essential for informing health delivery practices and gauging the extent of potential impact the NCD policy strategies can make at the population level. Mendis S. et al. advocates that national NCD implementation guidelines are essential for effective policy implementation and should clearly define roles and targets, detailed implementation activities and include sub-national actions plans developed in alignment with national NCD policy strategies [22]. Such sub-national action plans should be adapted to suit prevailing economic and socio-cultural norms in low resource settings.

The situation is further aggravated by the poor coordination within the health sector and poor intersectoral engagement with other sectors such as education and agriculture with major implications for improving the environment, advocacy and community mobilisation for NCD programs/activities, which are key NCD policy planning and implementation levers [12]. Similarly, a recent study found a poor awareness of the roles of the various sectors and weak coordination as key barriers to the use multi-sectoral action (MSA) in NCD prevention policy development in five SSA countries [29]. While the poor intersectoral engagement could be attributed to poor recognition of the crucial roles that other sectors play in NCD prevention and control, it compromises the utilisation of the life course approach as stipulated in the NCD policy. It further obstructs improvements in the physical environment such as in roads and town planning which are needed to encourage uptake of behavioural modifications. Rasanathan K. et al. calls for the health sector to cultivate a collaborative leadership role among all sectors and engage with identified sector champions working towards agreed on objectives across all levels [30]. Within the health sector, poor collaboration appears to facilitate duplication of NCD control programs, which has implications for the use of scarce resources. For example, the Regenerative Health and Nutrition Program (RHNP) and the national NCD Control Program are similar NCD programs operating vertically by the policy (MoH) and service delivery (GHS) arms of the health sector respectively. A previous study in 2012 advocated that they should be integrated to ensure efficiency [7] with the national NCD policy proposing a restructuring of the national NCD control program under the GHS to enable integration into health service delivery [13]. While the institution of regional level NCD focal persons is a commendable achievement of the NCD policy, it is potentially a tick box as instituted regional NCD focal persons remain under-resourced to undertake any NCD related activities. Effective coordination and intersectoral engagement for implementing the NCD policy strategies to facilitate the adoption of behavioural modifications necessary for the prevention and control of the growing NCD burden is even more important now than ever given their catastrophic impacts on population health and national, regional and global development efforts.

Furthermore, similar to findings reported in other studies conducted in LMICs [31,32], the implementation of the national NCD policy in Ghana is hindered by inadequate financial commitments. Identified as a major influencer in NCD policy planning and implementation [12,33], the lack of adequate funding is aggravated by the health systems' low prioritization of NCDs due to the continued high prevalence of communicable diseases and donor funding for communicable diseases. This is evidenced by the lack of clearly stated funding mechanisms to guide the NCD policy implementation process, which has significant rippling implications for effective NCD policy implementation at the sub-national levels. For instance, while the inclusion of selected prevalent NCDs into routine disease surveillance is a creditable achievement under the NCD policy, it is obvious that the lack of adequate funding for NCDs constraints their surveillance, which hinders the generation of timely quality data on NCDs and their risk factors as key NCD policy objective. Such timely quality NCD related data is crucial to informing NCD policy decisions and the implementation process while also facilitating sub-national adaption and implementation of interventions to make sustained population level gains. Moreover, the national NCD policy clearly outlines the need for public screening for NCDs and integration to facilitate early diagnosis and management, which requires significant financial investment into health professional training, equipment and logistics, which are sorely lacking. African governments need to invest in providing the necessary healthcare infrastructure, human resource and medicines while adopting a coordinated life course approach to sensitization on the behavioural risk factors in order to urgently address the increasing NCD threat to enhance sustainable development.

The finding on inadequate funding is a further reflection of the paucity of global financial commitments to the prevention and control of NCDs which has remained persistently under 2% over the last decade [32,34]. The influence of donor funding on the prioritisation of communicable disease is consistent with findings in another study where donor funding was found to significantly influence national health policy planning and implementation in LMICs [32]. As global funding often drives African governments' priorities, it is important that global advocacy be suited by global resource investments into NCDs. Given the catastrophic costs associated with seeking healthcare and the long-term impacts of NCDs on population health outcomes, funding for the implementation of NCD policies should be considered as crucial investments towards developmental efforts. African governments should consider allocating fixed budget lines for NCD activities in health planning and/or earmarking revenue accrued from tobacco and alcohol taxes to finance the implementation of NCD policies. Utilisation of alternate sustainable financing mechanisms such as joint financing and public-private sector partnerships could further improve funding for effective NCD policy implementation.

Moreover, as part of the NCD policy implementation measures, some attempts have been made to integrate NCD activities into routine health care services such as instituting prevalent NCDs related clinics at regional and selected district health facilities and occasional public screening programs. While this is a significant achievement to enable early detection and clinical care, the poor coordination between NCD disease-specific units, shortage of health professionals coupled with inadequate NCD related capacity present key challenges to integration within the context of an overburdened health system. Several studies have advocated for NCD related training for health professionals [11,[35], [36], [37]] with a recent study advocating for the inclusion of screening, diagnosis and management of NCDs into the pre-training curriculum of health training institutions to build sustained health worker capacity for addressing the key aspects of long-term care for NCDs and co-morbid conditions [37]. This is crucial to enhancing the integration of NCDs into routine primary health care services as is a key NCD policy strategy.

5. Conclusions

The study contributes contextual evidence, on the need for national NCD policies to be complemented with the creation of awareness particularly at sub-national levels; detailed implementation plans and clearly defined structures and processes to enable effective policy implementation. The findings further call for health sector leadership and collaborative intersectoral engagement in adopting adaptive measures including, devising sustainable financing mechanisms aligned with NCD policy implementation; awareness creation on the NCD policy and its strategies particularly at the implementation levels; building NCD related capacity pre and post professional training for health professionals to facilitate effective integration for improved preventive and clinical care for addressing the increasing NCD burden in Ghana and potentially in other SSA countries.

CRediT author statement

GNN: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, analysis, writing - original draft; KS: Conceptualization, visualisation and writing - Review & Editing; LM: methodology, writing - Review & Editing; CLK: writing - Review & Editing; CA: Conceptualization, visualisation and writing - Review & Editing.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

COREQ (Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research) Checklist.

Additional supporting quotes.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The Erasmus Mundus Joint Doctorate Program of the European Union Framework Partnership Agreement 2013-0039, Specific Grant Agreement 2015-1595 supports this work though the Amsterdam Institute of Global Health and Development (AIGHD) as part of Ms. Nyaaba's PhD candidacy at the Amsterdam University Medical Centres, University of Amsterdam. We thank Professor Ama de-Graft Aikins (Regional Institute for Population Studies, University of Ghana, Ghana) for contributing to the conception and design of the study protocol and for supervising data collection during fieldwork. The authors also thank the study participants for participating in this study.

Contributor Information

Gertrude Nsorma Nyaaba, Email: g.n.nyaaba@amsterdamumc.nl, ngertrude@gmail.com.

Karien Stronks, Email: k.stronks@amstermanumc.nl.

Lina Masana, Email: lina.masana@gmail.com.

Cristina Larrea- Killinger, Email: larrea@ub.edu.

Charles Agyemang, Email: c.o.agyemang@amsterdamumc.nl.

References

- 1.Africa WROf NCDs. https://afro.who.int/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases Available from:

- 2.Dalal S., Beunza J.J., Volmink J., Adebamowo C., Bajunirwe F., Njelekela M., et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: what we know now. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(4):885–901. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. Global action plan for the prevention and control of NCDs 2013–2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyaaba G.N., Stronks K., Aikins Ad-G, Kengne A.P., Agyemang C. Tracing Africa’s progress towards implementing the Non-Communicable Diseases Global action plan 2013–2020: a synthesis of WHO country profile reports. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1) doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4199-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . 2017. Noncommunicable diseases: progress monitor 2017. Report No.: 9241513020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO. Noncommunicable diseases country profiles 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Report No.: 978-92-4-151462-0 Contract No.: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- 7.Bosu W. A comprehensive review of the policy and programmatic response to chronic non-communicable disease in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2013;46(2):69–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de-Graft Aikins A. Ghana's neglected chronic disease epidemic: a developmental challenge. Ghana Med J. 2007;41(4):154. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de-Graft Aikins A., Addo J., Ofei F., Bosu W., Agyemang C. Ghana’s burden of chronic non-communicable diseases: future directions in research, practice and policy Ghana. Med J. 2012;46(2 Suppl):1–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de-Graft Aikins Ad-G. Multidisciplinary perspectives. Sub-Saharan Publishers; 2014. Chronic non-communicable diseases in Ghana. [Google Scholar]

- 11.de-Graft Aikins Ad-G, Kushitor M., Koram K., Gyamfi S., Ogedegbe G. Chronic non-communicable diseases and the challenge of universal health coverage: insights from community-based cardiovascular disease research in urban poor communities in Accra, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(Suppl. 2):S3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-S2-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. Preventing chronic diseases: a vital investment: WHO global report. [Google Scholar]

- 13.MoH G. Ministry of Health; 2012. National policy for the prevention and control of chronic non-communicable diseases in Ghana. 2012 August. [Google Scholar]

- 14.WHO . 2015. Noncommunicable diseases progress monitor 2015. Report No.: 978 92 4 150945 9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agyepong I.A., Nagai R.A. “We charge them; otherwise we cannot run the hospital” front line workers, clients and health financing policy implementation gaps in Ghana. Health Policy. 2011;99(3):226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyonator F., Kutzin J. Health for some? The effects of user fees in the Volta Region of Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14(4):329–341. doi: 10.1093/heapol/14.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Britten N. Qualitative research: qualitative interviews in medical research. Bmj. 1995;311(6999):251–253. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis J.J., Johnston M., Robertson C., Glidewell L., Entwistle V., Eccles M.P., et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. 2010;25(10):1229–1245. doi: 10.1080/08870440903194015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason M., editor. Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Forum qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: qualitative social research. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charmaz K. Sage; 2006. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mays N., Pope C. Qualitative research: rigour and qualitative research. Bmj. 1995;311(6997):109–112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6997.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mendis S., Fuster V. National policies and strategies for noncommunicable diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:723. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nyaaba G.N., Stronks K., Meeks K., Beune E., Owusu-Dabo E., Addo J., et al. 2019. Is social support associated with hypertension control among Ghanaian migrants in Europe and non-migrants in Ghana? The RODAM study: Social support hypertension control among a SSA migrant population. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assan A., Takian A., Aikins M., AJBo Akbarisari. Challenges to achieving universal health coverage through community-based health planning and services delivery approach: a qualitative study in Ghana. 2019;9(2) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mauti J., Gautier L., De Neve J.-W., Beiersmann C., Tosun J., AJHrp Jahn, et al. Kenya’s health in all policies strategy: a policy analysis using Kingdon’s multiple streams. 2019;17(1) doi: 10.1186/s12961-019-0416-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.GHS RHD Upper East Region. UER/RHD 2015. Annu Rep. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Service GS . Ghana Statistical Service, Service GS; Ghana: 2014. Poverty profile in Ghana 2005–2013. 2014 August. [Google Scholar]

- 28.GHS RHD Northern Region. Ghana Health Service; 2015. Annual report. 2015 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juma P.A., Mapa-Tassou C., Mohamed S.F., Mwagomba B.L.M., Ndinda C., Oluwasanu M., et al. Multi-sectoral action in non-communicable disease prevention policy development in five African countries. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5826-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasanathan K., Bennett S., Atkins V., Beschel R., Carrasquilla G., Charles J., et al. Governing multisectoral action for health in low-and middle-income countries. 2017;14(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen LNJGha. Financing national non-communicable disease responses. 2017;10(1):1326687. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1326687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green A., Bennett S. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2007. Sound choices: enhancing capacity for evidence-informed health policy. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ovretveit J., Siadat B., Peters D., Thota A., El-Saharty S. Improving health service delivery in developing countries: from evidence to action. 2009. Review of strategies to strengthen health services; pp. 35–68. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seattle W. Financing Global Health . 2015. Development assistance steady on the path to new global goals 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de-Graft Aikins A., Boynton P., Atanga L.L. Developing effective chronic disease interventions in Africa: insights from Ghana and Cameroon. Glob Health. 2010;6(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-6-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de-Graft Aikins Ad-G, Unwin N., Agyemang C., Allotey P., Campbell C., Arhinful D. Tackling Africa’s chronic disease burden: from the local to the global. Glob Health. 2010;6(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-6-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nyaaba G.N, Masana L., Aikins Ad-G, Beune E., Agyemang C. Factors hindering hypertension control: perspectives of front-line health professionals in rural Ghana. Public Health. 2020;181:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

COREQ (Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research) Checklist.

Additional supporting quotes.