Abstract

Our research examines the development of social health insurance (SHI) in Vietnam between 1992 and 2016 and SHI's role as a financial mechanism towards achieving universal health coverage (UHC). We reviewed and analysed legislation from the Government of Vietnam (GoV) and performance data from the GoV and the World Bank. Stages of development were identified from legislative change leading to change in SHI functioning as a public financing mechanism: revenue collection, pooling of risk, and purchasing. Movement towards UHC was assessed relative to: population coverage, benefit coverage, and financial protection. Vietnam has implemented SHI through five stages: Stage I (1992–1998), Stage II (1998–2005), Stage III (2005–2008), Stage IV (2008–2014), and Stage V (2014 onwards). Coverage has widened from a compulsory scheme for civil servants and pensioners and a voluntary scheme for others, to a scheme that targets the entire population. However, UHC has not been achieved with 19% of the population uninsured in 2016 and high out-of-pocket payments. The benefit package includes a wide range of services and many expensive medications and considered to be generous. It is recommended that Vietnam focus on improving population coverage rather than further expanding the benefit package to achieve UHC.

Keywords: Social health insurance, Universal health coverage, Policy review, Vietnam

Highlights

-

•

Social health insurance in Vietnam has evolved through five stages of development.

-

•

The benefit package is considered generous given inclusion of expensive medications.

-

•

The individual enrolment mechanism is considered to have serious limitations.

-

•

Moving forwards, population coverage should be prioritised over expanding the benefit package.

-

•

Household enrolment should be considered to achieve universal health coverage.

1. Background

In 1948, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared “health” to be a fundamental human right [1]. Subsequently, the 1978 Alma-Ata declaration of Health for All asserted the responsibility of governments to provide adequate health and social measures to enable all people to attain the highest possible level of health [2]. The precursor is universal health coverage (UHC) [3] - the ability of all people to access adequate quality health services without financial obstacles [[4], [5], [6]]. There are three inter-related dimensions of UHC: coverage of the entire population, provision of the range of services necessary to meet needs, and financial protection against out-of-pocket (OOP) and catastrophic expenditure [7].

While there is “no one way to achieve UHC”, it is not possible without a healthcare financing mechanism, public and/or private [8]. Recommendations are that the mechanism should be publicly-governed and mandatory [9,10], that population coverage should be prioritised over the breadth of the benefit package [9], and that enrolment of all members of a household (household enrolment) should be undertaken to lessen the impact of economic disadvantage, reduce adverse selection and expand coverage [11].

1.1. Social health insurance: a health financing mechanism towards achieving UHC

Social health insurance (SHI) is a health financing mechanism that embodies each of three basic functions of a public financing mechanism (revenue collection, pooling of risks and purchasing), and can facilitate UHC [8]. SHI was first introduced in Germany in 1883 [12], and is in operation in many countries, including Vietnam [10,13].

Country-specific implementation of SHI involves varying degrees of autonomy from the government but adopts core principles and objectives. The government usually controls participant eligibility [12], with population coverage initially restricted to specific groups (such as government employees) [4,10,14]. The government usually provides partial or full subsidization to vulnerable groups [12]. There is open enrolment, so no one can be excluded on the basis of risk [14]. Inherent to the concept is the right to a defined package of health benefits available to contributors only; and financial protection against catastrophic health care expenditure [15]. Premiums are set in accordance with average population risk – community rating [4] but must reflect capacity to pay [14]. SHI is intended to embody a high level of cross-subsidization between risk categories [10].

Successful SHI systems are found in more urbanised countries with administrative systems that facilitate registration of members and collection of contributions by payroll deductions, and electronic transfers [10]. Other features of a country that favour SHI are a dominance of the formal sector in the labour market, capable public service administrators, good quality health care infrastructure, a preference for SHI among citizens, and political stability [10]. At least 27 countries have supported a state of UHC through the implementation of SHI [8], although a number have since converted to general taxation systems [13].

1.2. The historical foundations of social health insurance in Vietnam

Consequent to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s, reduced international aid to Vietnam led to an economic crisis [16]. To adapt to the changed circumstances, in 1986, the Government of Vietnam (GoV) implemented economic reforms, namely “Doi Moi”, that introduced “a socialism-oriented market economy” [17]. The reforms began by allowing private sector development, foreign investment and greater autonomy in public enterprises, and by reducing state subsidization of many sectors including health care [18,19]. In consequence, the health system faced difficulties with reduced investment in infrastructure, shortages of medication and equipment, and in meeting payment of salaries to medical professionals. Together, these factors adversely affected health service quality [20,21].

In response, a cost-sharing mechanism was established in 1989, with the financial burden partially shifted to patients [22,23]. The introduction of this new financing mechanism led to criticism that it had resulted in reduced accessibility to health services, particularly for vulnerable groups such as older persons, children, the disabled and others unable to work and the poor [24]. To address this criticism, the GoV implemented changes to the health financing mechanism. Firstly, they permitted the private provision of medical services [25] and supply of pharmaceuticals [26]. In 1992, SHI was introduced to cover specified health services within the public sector [19].

Several articles have reviewed reforms associated with the introduction of SHI system in Vietnam [19,21,[27], [28], [29], [30], [31]] including the processes involved in policy development (inception to 2013) [29], the role of stakeholders in policy implementation (1989 to 2014) [30], the introduction of SHI [21], the effectiveness of SHI's health financing functions during implementation up to 2007 [28] and in 2008 [19] and an assessment of the barriers to achieving UHC through a comparison of the Vietnamese and Korean SHI systems in 2009 and 1977 respectively [31]. Studies have also identified multiple pools and fee-for-service as risks to the sustainability of the system [21], and the need for continued evaluation of reforms in terms of impacts on key outcomes and the political dimensions of health reform [28]. Solutions to improve the financing system, including an argument for the expansion of SHI coverage through the tax system have also been suggested [19]. Further research to support the evolution of “universal health insurance” was recommended by Ha et al. (2014) [29]. The current financial performance of SHI in Vietnam is unknown, and there has been no assessment linking SHI development to its financial performance and UHC objectives.

This paper extends the aforementioned works and aims to: i) examine the development of SHI in Vietnam during 1992–2016 and its contribution as a financial mechanism towards the goal of achieving UHC; ii) highlight some key lessons in the roadmap to UHC; and iii) provide policy recommendations based on underlying economic principles, socioeconomic conditions, and institutional realities.

2. Materials and methods

We undertook a desk review of GoV's documents pertaining to SHI, supplemented by data reported by the World Bank and other publicly available sources.

3. Data sources

For the period 1992 to 2016, a list of all legislation - including Laws, Decrees, Circulars and Decisions of the GoV - relevant to the development and implementation of SHI in Vietnam - were identified through a systematic search of the Legal Normative Document (http://vbpl.vn/TW/Pages/vbpqen.aspx) and the Legislation Library Website (https://thuvienphapluat.vn/). To be eligible for review, documents were required to include “social health insurance” in their titles and pertain to non-sectoral funds.

Materials on the performance of SHI as a financial mechanism were obtained from the Ministry of Health (MoH) and the Vietnam Social Security Agency (VSS). Documents identified for inclusion a priori were Health Statistics Yearbooks and National Health Account from the MoH; and Annual Progress Reports and Health Insurance Reports from the VSS. Data were sought from the commencement of SHI (where possible) until the latest available data release.

The Health Statistic Yearbooks (1992–2016) provided data on health expenditure on treatment and prevention and the SHI coverage rate [32]. The Annual Progress Reports of the VSS (2008–2014) provided data on SHI expenditure for compulsory and voluntary schemes (1992–2012 and 2006–2012 respectively) [33]. The Health Insurance Reports provide data on SHI expenditure for the compulsory scheme (2014–2016) [34]. The National Health Account provides data on OOPs (1998–2012) [35]. Data on OOPs were also retrieved from the World Bank's website for the period (2000–2016) [36] to facilitate inter-country comparisons given that the MoH's definition includes health insurance premiums, which is non-standard.

4. Evaluation and analyses

4.1. Stages of development of SHI in Vietnam

To determine the stages of development of SHI all included legislative documents were examined to identify changes in policy that impacted one or more functions of SHI as a public financing mechanism: collection of revenue, pooling of risk, and purchasing [10].

4.2. Contribution of SHI as a financial mechanism towards achieving UHC in Vietnam

Data on the performance of SHI was assessed with respect to the three dimensions of UHC: population coverage (how many people were covered), scope of benefits (what services were covered), and contributions (premiums and payees, out-of-pocket expenses) across each stage of development. The financial performance of SHI was assessed in regard to annual revenue and expenditure (1992 to 2016, excluding 2013 due to unavailability), and net expenditure for compulsory and voluntary schemes from 2006 to 2012, data in 2013 was unavailable and the voluntary scheme ended in 2014.

Net expenditure was calculated as the difference between annual expenditure and revenue. For the compulsory and voluntary schemes, net expenditure was assessed by per cardholder, technical level of providers, occasion of service and type of service (inpatient and outpatient).

5. Results

5.1. Stages of SHI development in Vietnam

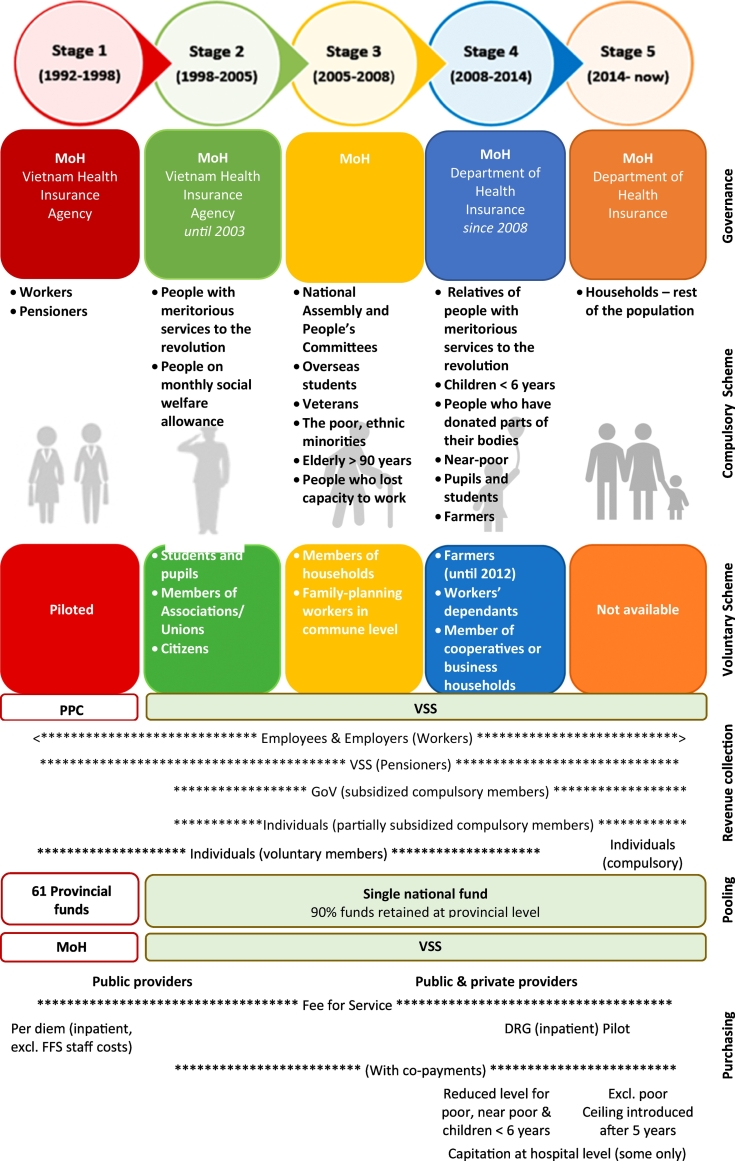

Reform of regulations and policy relating to SHI occurred in five stages (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Five stages of social health insurance evolution, and system characteristics.

DRG: Diagnosis Related Group; FFS: Fee for Service; GoV: Government of Vietnam; MoH: Ministry of Health; PPC: Provincial People's Committee; VSS: Vietnam Social Security Agency.

5.1.1. Stage I: August 1992 to August 1998

SHI commenced following the release of Decree 299/HDBT 15/8/1992 with implementation of a compulsory scheme for civil servants and pensioners (see Fig. 1), in which premiums were set at 3% of total salary [37], of which 2% was paid by the employer (see Appendix 1). This scheme was then expanded to include a pilot voluntary scheme for the families of workers in June 1994 through Decree 47/CP 06/06/1994 [38,39]. In this inaugural stage, SHI was overseen by the MoH, and implemented through the newly established Vietnam Health Insurance Agency [40]. Revenue collection and payments were managed at the provincial level by Provincial People's Committees [37]. Four additional stages of development were identified Stage II (1998–2005), Stage III (2005–2008), Stage IV (2008–2014), and Stage V (2014 onwards). Stage II arose consequent to Decree 63/2005/ND-CP in August 1998 with the commencement of an official voluntary scheme, the introduction of co-payments [44], the implementation of a single pool and significant changes in administrative structures. Stage III arose consequent to Decree 63/2005/ND-CP in May 2005 with expansions in eligibility for both the compulsory and voluntary schemes and revision of the benefit package and co-payment mechanism and led to the commencement of the third stage of SHI. Stage IV arose through the introduction of the first Health Insurance Law (No. 25/2008/QH12) which was effective from 1st July 2009. Stage V arose in 2014, through amendment of the first Health Insurance Law.

The SHI scheme was in turn comprised of 61 provincial pools operated by their respective Provincial People's Committee, with some provinces offering a voluntary scheme. There were also four sectoral pools (oil and gas, transportation, public security, and the armed forces) administered by their respective head of agency. Initially, SHI fully-funded services and medications through fee-for-service payments with inpatient “hotel” care funded through a per-diem-payment [41]. In 1995, the central government agencies including the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Social, Invalids and Social Affairs, and the National Committee of Pricing released a new list of eligible health services [42] based on a list from 1989 [23], and set reimbursement price ranges for public providers based on the cost of providing services in public hospitals by level [43]. Provincial People's Committees set specific prices for their province from the price range specified, based on socio-economic circumstances. By 1997, 17 out of 61 provincial funds (28%) were in deficit, having been co-managed with the provincial state budget and leading to appropriation for non-SHI purposes [20]. Concerns also existed about the low coverage rate and differences in benefits available between provinces [20].

5.1.2. Stage II: August 1998 to May 2005

Decree 58/1998/NĐ-CP of 13/8/1998 gave rise to the second stage of SHI development, ushering in the commencement of an official voluntary scheme, the introduction of co-payments [44], the implementation of a single pool and significant changes in administrative structures. The pool was initially administered by the Vietnam Health Insurance Agency within the MoH before being absorbed into the Vietnam Social Security Agency (VSS) - a government organization in charge of implementing social insurance policies - in 2002 [45]. The main SHI functions of the VSS were premium collection, improvement in fund management through centralised fund disbursement of claims received from providers, investment of fund reserves and implementation of SHI policy prepared by the MoH's Department of Health Service Administration [46,47]. The MoH remained responsible for setting policy regarding SHI functions, including setting premiums, designing the benefit package and setting reimbursement prices and co-payments, maintaining a focus on UHC.

5.1.3. Stage III: May 2005 to June 2009

Decree 63/2005/ND-CP on 16/5/2005 gave rise to expansions in eligibility for both the compulsory and voluntary schemes and revision of the benefit package and co-payment mechanism and led to the commencement of the third stage of SHI. Poor people were transitioned from the “Health care fund for poor people” to the compulsory scheme, with their premiums fully funded by the GoV. To minimise the risk of adverse selection, at least 10% of students/people in a school/commune were required to participate in the voluntary scheme [48]. Within the MoH, the Health Insurance Department was established in 2015 to design SHI policy and provide governance in terms of “administrative management” [49]. In addition to fee-for-service, payment mechanisms were expanded to include capitation in order to address financial sustainability issues [20,50].

5.1.4. Stage IV: July 2009 to June 2014

The first Health Insurance Law (No. 25/2008/QH12, approved by the National Assembly), was released on 14th November 2008 and became effective on 1st July 2009, and marked the start of the fourth stage of SHI development. This stage coincided with the transition of Vietnam from a low income country into a low-middle income country in 2009 as defined by the World Bank, with anticipated reductions of international aid for health, and in turn, the need for greater reliance on SHI to fund care.

The first Health Insurance Law, that gave rise to Stage IV, comprehensively changed SHI policy by expanding coverage to 25 insurance categories with poor people and children under 6 included within the compulsory scheme, with premiums fully subsidized by the GoV (see Appendix 1). A roadmap was established for compulsory enrolment for the entire population, to commence in 2014 [51]. In 2013, the GoV confirmed its intention to achieve “UHC” by releasing a master plan aimed at expanding SHI coverage to 75% of the population by 2015 and 80% of the population by 2020 [52], with increased coverage to be supported through expanded access to SHI subsidization.

Under the Health Insurance Law, funding arrangements were modified including increases in insurance premiums (see Appendix 1), with 10% of premiums received from each province to be retained centrally for administrative purposes [51]. The remaining provincial funds were to be used to reimburse health care costs incurred for curative examination and treatment at the provincial level. Co-payments were revised on a group-by-group basis. Provider payment mechanisms were modified to include capitation payments for primary health care providers [51,53], implementable at provincial and district levels. To encourage implementation, 20% of any surplus attributed to capitation could be used to reward hospitals, even if the total expenditure of the province was in deficit. The use of diagnosis related group (DRG) payments was defined in the Law due to the perceived unsustainability of fee-for-service, and piloted in four indications (treatment of pneumonia for children, treatment of pneumonia for adult, caesarean section and normal delivery).

In 2012, the GoV released Decree No. 85/2012/NĐ-CP to regulate institutional arrangements and financial mechanisms of public health facilities. Through this Decree a schedule (road map) was established to withdraw all government subsidization for public hospitals incurred outside SHI, e.g. salaries, electricity, capital equipment depreciation and research by 2016 [54], increasing reliance on SHI to fund health expenditure.

5.1.5. Stage V: June 2014 onwards

In June 2014, the Health Insurance Law was amended through Law No.46/2014/QH13 to reclassify the eligibility categories, eliminate the voluntary scheme, and schedule premium increases (see Appendix 1), change the mechanism of collection of revenue, and revise the benefit package (see Appendix 2). The SHI categories were reclassified based on source of premium payment, and included a new category for household enrolment [55]. The household category required all household members not eligible for any other SHI scheme to enrol together and pay the combined premium with the objective of maximising coverage and preventing adverse selection through enrolment of proportionally greater numbers of sick people. These changes in turn led to increased involvement of the Provincial People's Committees at an administrative level, and increased financial responsibility of the Committees [55]. One sectoral health insurance pool for the armed forces remained independent [56].

In 2015, a revised list of reimbursement prices for health services under SHI payment was released by the MoH. This revision was to ensure consistency, with all hospitals at the same level having to charge the same price for the same service to address the differences between provinces introduced by the authority of Provincial People's Committees to set health service price from Stage I. Further, at this time, prices were increased to cover salary of health care workers [54,57]. In the same year, the use of provincial level facilities no longer required referral from district level health facilities [58]. Co-payment requirements for the poor and other fully-subsidised individuals were stopped. New regulations were introduced on management of health insurance fund surplus to support primary health care (but were not implemented).

In 2015, the MoH commenced a project to enable electronic claims management, provide insured persons with a smart card and collect information for policy making [59]. The GoV regulated principles in electronic transactions in SHI management [60]. In 2017, 97% of service providers had access via a portal to the VSS claims management system, and 60% connected daily [61]. However, the smart card was yet to be implemented.

5.2. Contribution of SHI as a financing mechanism towards achieving UHC in Vietnam

5.2.1. Population coverage

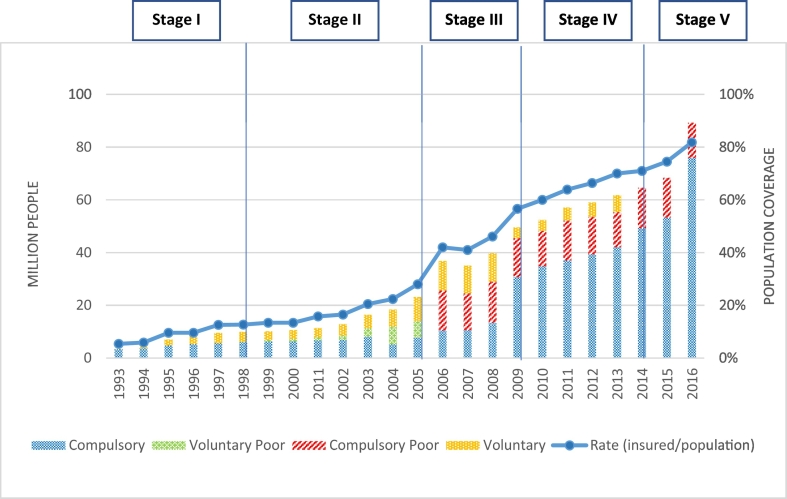

Population coverage across the stages of development of SHI are illustrated in Fig. 2. SHI coverage increased significantly from 5% to more than 70% between commencement of Stage I (1993) to the commencement of Stage V (2014). By 2016, coverage had reached almost 82% of total population. Compulsory enrolment was largely stable during Stage I and Stage II with growth in enrolments due to the inclusion of voluntary members, including poor persons, in Stage II. At the end of Stage II, voluntary members comprised two-thirds of enrolments, of which about two-fifths (41%) were poor persons. In Stage III, the inclusion of a compulsory poor scheme led to significant growth in enrolments: the number of poor people covered increased from 6.39 million in 2005 to 15.18 million in 2006. However, growth in other compulsory enrolments increased 76% between 2005 and 2008 (from 7.69 million to 13.53 million, respectively). Newly-included groups in the compulsory scheme during Stage III were older people, veterans, and people no longer able to work [50]. Premiums for these individuals were fully subsidized. At the end of Stage III, SHI coverage had increased to 46% of the population. Stage IV produced the most marked upturn in enrolments in the general compulsory scheme (i.e., excluding the compulsory poor), when enrolments more than doubled between 2008 and 2009 – from 13.53 million to 30.74 million. At this time, the scheme was expanded to include children under 6 years of age and the near-poor, which were fully and partially subsidized, respectively. Further growth occurred with the inclusion to the voluntary scheme with school pupils and higher education students in 2010 and farmers in 2012. In turn, there was a significant reduction in voluntary membership at the commencement of Stage IV. Nevertheless, the voluntary scheme experienced growth during Stage IV due to an expansion in eligibility. Stage V saw a further expansion of the compulsory scheme coinciding with the cessation of the voluntary scheme.

Fig. 2.

Social health insurance coverage of the Vietnamese population, 1993–2016, by SHI scheme: numbers of people covered and rate of coverage.

5.2.2. Provision of services

Since inception, the core elements of the SHI benefit package have always comprised inpatient and outpatient services, which include consultation fees, pathology, medications, and consumables (Appendix 1), with the first formal listing released in 1995 [43]. Beyond Stage II, the benefit package was widened to include pregnancy check-ups and transportation for vulnerable groups [50] in Stage III, introduction of partial payment for higher-level services when lower-level services were by-passed [51,53] in Stage IV, and treatment of squint, short-sightedness and refractive defects for children under 6 and treatment of self-inflicted injuries or physical or mental injuries caused by the patient's illegal acts [55] in Stage V. However, some benefits introduced in Stage IV proved to be transitory, being removed in Stage V (Appendix 1). The benefit package has never covered preventive health care, and has only covered HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis treatment since Stage IV, coinciding with the reduction in international aid [62] [63].

An essential drugs list was introduced at the end of Stage II (in 2005) and underwent modifications in each subsequent stage. At the commencement of Stage V (in 2014), the essential drugs list contained 1201 types of medication including combination therapies, and included expensive drugs which were not in the essential drug list of the WHO (e.g. erlotinib, gefinitib, sorafenib, tacrolimus and imatinib) [64] (Appendix 1). In 2018, the list was expanded to 1030 types of medication including combination therapies [65].

5.2.3. Financial protection from out-of-pocket payments (OOPs)

During Stage I there were no co-payments under SHI, including for prescribed medicines. In Stage II, a 20% co-payment was introduced, except for veterans, although prescribed medicines were fully subsidized for most of this Stage [66] and a co-payment ceiling equivalent to six-months basic salary applied. The voluntary scheme had lower levels of reimbursement per service compared to the compulsory scheme, and reimbursement ceilings for several expensive services including heart surgery and hemodialysis. In Stage III, co-payments remained at 20% but the general ceiling for co-payments was removed. Rather, ceilings were applied for outpatient services (voluntary schemes only) and to a list of expensive services (both schemes) [67,68]. Levels of reimbursement remained more generous for the compulsory scheme. In Stage IV, all payment ceilings were removed and co-payments set at either 0% (children under 6, people who lost working capacity, and unemployed); 5% (poor people, veterans, and people received social allowance) and 20% (the remainder). In Stage V, the 5% co-payment was removed for poor people and veterans, so all fully-subsidized people had no co-payments. Otherwise, a co-payment ceiling was re-introduced for members with 5 years of continuous membership.

To receive the maximum level reimbursement, each member was required to first attend their allocated “primary health care facility” before referral to higher technical level facilities (e.g. provincial level hospital) across all Stages, except the commune level from Stage IV and district level in Stage V [69] (seeAppendix 1).

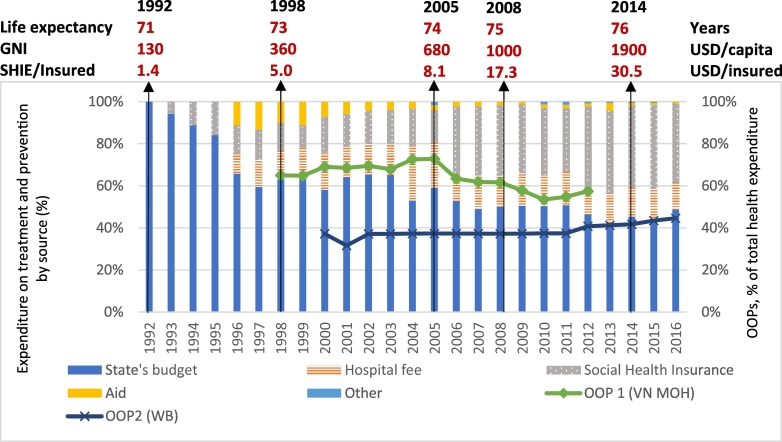

5.3. Contribution of social health insurance to health expenditure

Over time, SHI has become an important source of health expenditure for treatment and prevention in Vietnam (Fig. 3), increasing from 5% in Stage I (1993) to 13% in Stage II (1998), 15% in Stage III (2005), 33% in Stage IV (2009), and 48% in Stage V (2016). Meanwhile, out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) as defined by MoH declined from 65% (1998) to 57% (2012) of total health expenditure, while OOPs as defined by the World Bank increased from 37% to 45% between 2001 and 2016. Hospital fees fluctuated around 15% of health expenditure for treatment and prevention during 1997–2016, with a peak of 26% in 2004.

Fig. 3.

Social health insurance as a component of health expenditure for treatment and prevention and out-of-pocket payment in Vietnam from 1992 to 2016.

(Abbreviations: GNI: Gross National Income; MoH: Ministry of Health; OOP: Out-of-pocket payment; SHIE/Insured: Social Health Insurance expenditure per insured people; USD: United States Dollars; WB World Bank; VN: Vietnam.)

OOP 1: Out-of-pocket payments as % of expenditure on total health expenditure. OOP defined by the Vietnam Ministry of Health: “Total household spending: user fees paid at public providers (including health insurance co-payment) + user fees paid at private providers + payment for health insurance premium (voluntary) + other payments (for drugs, consumables at pharmacies and etc.)” [35]. No data are available since 2012.

OOP 2: Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure). Out-of-pocket payments defined as spending on health directly out-of-pocket by households. As reported by The World Bank (since 2000). Indicator code: SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS [36].

http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.ZS?name_desc=true

5.4. Financial performance of social health insurance in 2006–2016

5.4.1. Total net expenditure, and expenditures for inpatient and outpatient care

SHI was in surplus all years, except for each year of Stage III and 2016, Stage V (see Fig. 4a). Notably, the revenue in 2010 was approximately double that in 2009, while expenditure increased by 35%, SHI transitioning from Stage III to Stage IV from October 2009. During the last year of Stage IV (2014), and first year of Stage V (2015), SHI gave rise to substantial surpluses, of VND 15,000 Billion. However, in 2016, SHI again returned to deficit, but less marked at, VND 1000 Billion.

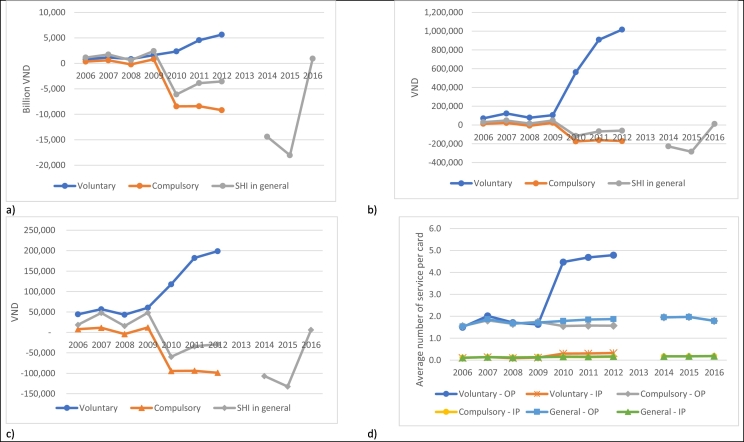

Fig. 4.

Financial performance by scheme 2006–2016 a) net expenditure (VND) b) average net expenditure per cardholder (VND) c) average net expenditure per occasion of service (VND) d) average service utilization by type of service.

The evidence supports SHI as having facilitated progress towards UHC, although almost 20% of the population were not covered in 2016. SHI was in surplus all years, except for each year of Stage III and 2016, Stage V. An assessment of financial performance during the transition from Stage III to Stage IV, provided evidence towards the importance of premiums to financial sustainability, ‘adverse selection’, cross-subsidization, and the potential impact of co-payments. Expenditure on inpatient services exceeded that for outpatient services in all years, except for 2001 and was highest in 1993 (the first year for which we have SHI data), when inpatient services accounted for 65% of SHI expenditure. The proportion of SHI expenditure on inpatient services otherwise fluctuated between 50% to approximately 60% (see Appendix 3).

5.4.2. Financial performance of compulsory and voluntary schemes during 2006–2016

In Stage III (i.e., 2006–2008) and in 2009 (the transition year between Stage III and Stage IV), both compulsory and voluntary schemes were in deficit. From 2010, the first full-year of Stage IV, net expenditure of the compulsory scheme reduced markedly leading to a surplus of VND 9 trillion in 2012, while net expenditure for the voluntary scheme increased steadily from VND 2 trillion (in 2010) to around VND 6 trillion (in 2012) (Fig. 4a). Fig. 4b shows that average cost per SHI cardholder was always greater for the voluntary than compulsory schemes, particularly since 2010. From 2010, net expenditure per SHI cardholder for the compulsory scheme became negative (i.e., revenue positive at VND 200,000 per cardholder), while the average net expenditure per voluntary cardholder approached VND 1 million in 2012, which was nearly double the premium. A similar pattern to average cost per cardholder was observed for net expenditure per visit (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4d indicates that the average service use for the compulsory scheme differed slightly from that for the voluntary scheme for both outpatient and inpatient services from 2006 to 2009. However, from 2010, the average number of outpatient and inpatient services increased for voluntary scheme members. This increase was most marked for outpatient services, which increased 2.75-fold (from 1.63 to 4.47 visits per annum per cardholder). Voluntary scheme cardholders thus gave rise to around triple the number of outpatient visits and double the number of inpatient visits on average, as compared with the compulsory scheme cardholders during 2010–2012. In Stage V, the average inpatient services and outpatient services per card for all members within the Scheme, given the transition to a compulsory scheme only, did not change markedly compared to Stage IV.

6. Discussion

During the period 1992–2016, the SHI system in Vietnam evolved through five dynamic stages of expanded coverage, increased pooling of risk, and inclusion of financial protections, primarily for the vulnerable. Coverage increased from 5% of the population in 1993 to 71% in 2014, and to 81% in 2016. The number of funds at the provincial level reduced from 61 in Stage I to a single pool in Stage II. Vulnerable groups (comprising the poor and near-poor, children under 6, older people, and people with lost work capacity) became compulsorily enrolled, and fully- or partially-subsidized; and by Stage V, had no co-payments for services provided under SHI, except from the near-poor with 5% co-payment. Benefits initially comprised core services and treatments, and any prescribed drugs. However, an essential drugs list was introduced in Stage II, and expanded in each subsequent stage. Other benefits were introduced from Stage III to Stage V. Most were retained, including transportation for vulnerable groups (Stage III), coverage of sexually transmitted diseases (Stage IV), and treatment of persons self-harming or injured in illegal activity (Stage V). The major exception was bypassing for outpatient care that was introduced in Stage IV, and then eliminated in Stage V. The contribution of SHI expenditure to health expenditure for treatment and prevention increased eight-fold over the study period. In addition to subsidization, financial protection was strongest for members in Stage I (with full payment) and at its weakest in Stage III (with 20% co-payments and no co-payment ceiling, with voluntary members also facing more limited re-imbursement compared with compulsory members). From Stage IV, increased protection has been facilitated through co-payment reductions and/or ceilings. Currently, there are efforts to automate processes by implementing an electronic payment system. Electronic systems will support monitoring capabilities, including the performance of health facilities, provider behavior and consumption of drugs enabling audit capabilities, improvements in efficiency and support assessments of service utilization across provinces.

6.1. SHI has facilitated progress towards UHC

There has been evidence that SHI has facilitated progress towards UHC. First, SHI has expanded from a restricted program covering people whose premiums could be obtained from the existing payments infrastructure to a “compulsory” scheme covering over four-fifths of the total population in 2016 (Fig. 2). This level of coverage exceeded the 2020 target of 80% of the total population set in 2012 [52]. We also noted that the voluntary scheme was in effect used as a stepping stone towards compulsory enrolment, with the use of open enrolment and community rating of premiums, as expected in a SHI scheme [14]. Such an approach could be considered for other countries looking to implement SHI but unable to establish universal coverage in the first instance. Second, SHI has enabled Vietnam to extend financial protection to vulnerable groups through full- or partial-subsidization of premiums, and no requirement for co-payments for fully-subsidized members introduced over Stages IV and V. Third, the unification of 61 provincial funding pools in Stage II resulted in a single risk pool that, while not necessary for UHC, increased the prospects of UHC by facilitating cross-subsidization [10] and improving the viability and sustainability of the financing mechanism. The importance of the single pool was reflected in the net expenditure data, with SHI in deficit in each year of Stage III, becoming in surplus in Stage IV and remaining so until mid-Stage V. There was also evidence of significant cross-subsidization between compulsory and voluntary schemes in Stage IV when both were operational. However, while co-payments were removed for all fully-subsidized members by Stage V and a ceiling on co-payments re-introduced for the long-term insured, the contribution of OOPs to total health expenditure has been increasing since 2011 (mid-Stage IV) based on WB data. Further, as the percentage of expenditure on hospital fees was constant over this period, these findings indicate that OOPs were increasingly for non-hospital related costs of care. We note that OOPs as assessed by the MoH have decreased over the study period as compared with the increase for the WB, reflecting the importance of the definition of OOP employed.

6.1.1. Financial performance and protection

Through the assessment of financial performance during the transition from Stage III to Stage IV, we observed evidence of the importance of premiums to financial sustainability, ‘adverse selection’, cross-subsidization, and the potential impact of co-payments.

To ensure financial sustainability, revenue must be sufficient to cover expenditure and thus generate a reserve [10]. We observed that SHI was in deficit during Stage III, and this arguably led to the premium increases observed in Stage IV, with the fund then remaining in surplus until 2016. In 2016, the SHI fund gave rise to a deficit even through service utilization decreased, the impact thus attributed to the increase in health service list prices in 2015 [57]. The VSS has requested a further premium increase [71], and on the basis of these findings, this claim might be vindicated. However, further monitoring of trends in service utilization and expenditure is recommended to inform any adjustments, given the accumulated surplus available to the VSS.

In Stage IV, when enrolment in the voluntary scheme was opened to all Vietnamese, adverse selection became evident with the marked increase in the average outpatient visits per cardholder (assuming those who demanded care, needed care). Adverse selection is expected within a voluntary scheme [10], but from the perspective of UHC we argue this should be viewed as a positive outcome, as it enables those who need care, to access ongoing funding for health care – “leave no one behind” [72].

Given this ‘adverse selection’ and a lower average premium for a voluntary cardholder, cross-subsidization of the voluntary scheme members by the compulsory scheme members is expected and was evident. This cross-subsidization is considered a positive outcome of the scheme, as the healthy subsidized the unwell as per UHC principles [10].

Between 2010 and 2012, expenditure per compulsory cardholder and their average service utilization remained stable. However, net expenditure per visit decreased slightly. We believe that this was a consequence of the re-introduction of co-payment ceilings in Stage IV. Given that co-payments are intended to reduce unnecessary service utilization [10,14], and given no clear reduction in service utilization, their appropriateness should be questioned. Are they leading to unnecessary financial burden on members who need care? Some studies have suggested that for some vulnerable groups including people living with a disability and poor people living in rural areas, financial hardship has been experienced even though they were insured [73,74]. Given that these studies were undertaken before introduction of zero co-payments for fully-subsidized members, these concerns may no longer be so acute.

6.1.2. Mechanisms that have supported increased coverage

subsidization was associated with the most significant increases in coverage as reflected in the almost doubling of coverage with the inclusion of the poor and other vulnerable groups in Stage III, and the more than doubling of the general compulsory scheme in Stage IV with the inclusion of children under 6 and the near-poor. However, it must be acknowledged that this achievement required a significant financial commitment from Vietnam relative to other Asian countries and regions that have successfully achieved UHC through SHI. For example, the levels of full-subsidization for the poor comprised 15% of Vietnam's total population as compared with 2% in Taiwan [75] and 3% in South Korea [76]. Furthermore, loans through the World Bank and Asian Development Bank were required to support subsidization of the near-poor [[77], [78], [79]].

6.2. Ongoing challenges on the path towards universal health coverage in Vietnam

Compared to other countries who were at similar levels of socioeconomic status when they commenced on the pathway to achieve UHC, Vietnam is taking longer, than Thailand at 27 years [80] and South Korea at 12 years [31]. Furthermore, Vietnam is facing several challenges ahead, as follows.

6.2.1. Facilitating enrolment for the uninsured

As of 2016, nearly 20% of the total population were not covered by SHI, even though SHI had been regulated to be compulsory. The underlying problem is that enrolment still relies on a voluntary mechanism and the identity of people who are not enrolled is unknown. Non-enrolled individuals primarily work within the informal sector, a common issue for developing countries [13], and there is no connection between SHI and an individual's taxation number nor their national identity number. Thus, there is no efficient mechanism to identify the identity of the uninsured. In addition, it still remains possible for people from the informal sector to enrol only during periods of anticipated medical need [55]. To encourage continuous enrolment and minimise adverse selection, benefits to expensive services are restricted to those who have a minimum of 6-month enrolment, as introduced for the voluntary scheme in Stage II. Also, an annual co-payment ceiling was introduced for any cardholder with continuous enrolment for at least five years in Stage V. The effectiveness of these measures has not been assessed.

Potential solutions to periodic enrolment can be discerned from mechanisms employed in other countries. For example, in Singapore, Switzerland and Germany, each of which has achieved UHC through individual mandate, and penalties are employed against non-participation. In Germany, people who re-enrolled may be charged outstanding premiums with interest, while penalties are applied in Singapore and Switzerland [81]. Similar financial sanctions for non-enrolment have been announced in Vietnam [82], but have not been applied [83]. Another potential and recommended mechanism to facilitate enrolment is household enrolment [11]. Household enrolment is employed in Thailand [84], South Korea [76], Japan and China [11], each of which has achieved UHC, with household enrolment based around an existing member. This contrasts to the household enrolment mechanism introduced in Vietnam in Stage V [55], which is limited to those who are not eligible to enrol in any other category. As previously mentioned, identification of those who are not currently enrolled is problematic, arguably making Vietnam's household enrolment mechanism less effective than it could otherwise be. Further, the lack of an electronic database of enrolees limits the ability to pursue those who dropout of enrolment, as it does to identify those who maintain enrolment and reach the co-payment ceiling, impairing its efficiency.

6.2.2. Generous benefit package

The SHI benefit package provided in Vietnam is generous compared to that provided in most other countries with similar GDP in the Asian region, at least regarding the drugs subsidized. For example, Vietnam's drugs list currently includes 1201 non-traditional medications while Bhutan's list has 429 [85], the Maldives has 394 [86], the Philippine's list has 627 [87], and the WHO's essential drugs list has 408, and all include vaccinations. Moreover, the Vietnam list includes expensive drugs (including erlotinib, gefinitib, sorafenib, tacrolimus and imatinib) which are not included in the WHO's list. A generous benefit package runs counter to the advice that a country should prioritise population coverage [9] and start with a small benefit package that all can access [88]. Also, Vietnam does not have specific criteria for including benefits in the SHI benefit package (e.g. cost-effectiveness analysis as recommended), but rather is determined on the basis of historical provision and general guidance under SHI Laws. In addition, each province will develop their own sub-list of approved services, which can lead to a gap between policy and practice and inequalities in service provision between provinces. Thus, we recommend that any future expansions to the benefit package be limited until UHC is achieved. We also recommend that economic evaluation, budget impact evidence, and equity be considered in relation to existing and future benefits in line with the World Bank guidelines [10,11], and WHO and MoH recommendations [5,89,90].

6.2.3. Institutional arrangements to support universal health coverage

The health insurance system in Vietnam is currently showing signs of dysfunction as reflected in the denial of payment of claims by the VSS for alternate view x-rays [91,92], sending letters to provincial health services demanding reduced claims against provincial funds [91,93,94] and tensions between the VSS and MoH within the press [95] and between VSS and providers [92,[95], [96], [97]]. The underlying issue is conflicts regarding organizational role and responsibilities [[98], [99], [100]]. The need for “a referee” to adjudicate disputes is evident. Such an approach is applied in South Korea [101,102] where a third agency separate to the providers and fund holder reviews claims, makes assessment of reimbursement, and undertakes assessment to revise and update the benefit package. We suggest that the introduction of an equivalent agency in Vietnam may assist the sustainability and functioning of the system. The World Bank has also recognised the problems in Vietnam SHI institutional arrangements and recommended reform [11].

6.2.4. Transition to a middle-income country

International aid has historically played an important role for many national health programs in Vietnam for the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. For example, international aid funded 19% of the total budget of the HIV/AIDS program during 2012–2015 [103], and made a major contribution to the tuberculosis prevention program, including all medications for drug-resistant tuberculosis in 2017 [104]. However, with the transition of Vietnam to a low-middle income country, there has been a reduction in international aid since 2008 [105], and an increase in funding that needs to be serviced, given the provision of funds through loans rather than grants [106]. This change has and will continue to lead to increased burden on the GoV's budget, and the need to further expand both the population and benefit coverage under SHI given, for example, only 40% of HIV/AIDS patients have SHI coverage in 2018 [107]. Other concerns include the sustainability of the SHI fund, inclusion of preventive clinics into the SHI payment system, and the challenge to retain the confidentiality of HIV/AIDS patients.

On the basis of these findings, other countries contemplating the introduction of SHI should consider prioritizing the introduction of a single pool from implementation; that population coverage should be prioritised over the benefit package and that a staggered approach to including population sub-groups may facilitate population coverage. Further, a household enrolment mechanism based on a member with coverage be considered. A voluntary scheme can also support coverage, but the evidence indicates that self-selection will occur. Further, it is essential to undertake ongoing budget impact assessments, as modifications to the Scheme can impact its overall sustainability. Institutional arrangements should be designed so that conflicts of interest are minimised. Further, that automation for enrolments and electronic claims systems be introduced as a priority to support transparency and policymaking, and the efficiency of the system.

6.3. Strengths and limitations of this research

This study has been the first to review the development of SHI in Vietnam from its commencement in 1992 as a financial mechanism towards achieving UHC and is based on formal written documents in the public domain, including laws, decrees, circulars and decisions of the GoV. Our assessment of the achievement of UHC has been limited, however, being focussed on a system level analysis. As such we could not consider performance at the provincial level, nor functioning and impacts at household or individual levels, including access to care and the extent of financial risk protection afforded by SHI at these levels. Such considerations will be the focus of our future studies on SHI in Vietnam.

7. Conclusions

There has been considerable progress towards universal SHI in Vietnam. However, coverage in the informal sector remains incomplete and the benefit package appears overly generous for a low-middle income country. It is crucial to the achievement of UHC that Vietnam prioritises population coverage over the size of the benefit package by employing a mechanism that can effectively target both formal and informal sectors. Also, the benefit package should be revised in the light of cost-effectiveness and other recommended considerations. Finally, the roles and responsibilities of purchasers, service providers and regulators should be clearly established to minimise conflicts of interest and ensure transparency.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

Social health insurance benefit coverage by stage of development

Premium and premium subsidy for social health insurance by stage of development

Revenue and expenditure by type of service under SHI fund 1993–2016

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Quynh Ngoc Le: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Leigh Blizzard: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Lei Si: Writing - review & editing. Long Thanh Giang: Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing - review & editing. Amanda L. Neil: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Visualization.

Declaration of competing interest

QNL is an Officer, Department of Health Insurance, Ministry of Health, Vietnam on study leave. GTL has undertaken contractual work for the Ministry of Health, Vietnam.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The assistance of Ms Nguyen Thi Hong Yen in document retrieval, the Department of Health Insurance – Vietnam Ministry of Health for providing data. QLN is supported by an Atlantic Philanthropies Scholarship through the Menzies Institute for Medical Research, University of Tasmania. ALN is supported by a Select Foundation Research Fellowship. LS is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Availability of data and material

Source data are available through the Ministry of Health and World Bank websites as cited. All data is presented in the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Quynh Ngoc Le, Email: ngoc.le@utas.edu.au.

Leigh Blizzard, Email: leigh.blizzard@utas.edu.au.

Lei Si, Email: lsi@georgeinstitute.org.au.

Long Thanh Giang, Email: longgt@neu.edu.vn.

Amanda L. Neil, Email: amanda.neil@utas.edu.au.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 1948. Constitution. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 1978. Alma Ata Declaration. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Health financing for universal coverage: the World Health Organization; 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/health_financing/universal_coverage_definition/en/. [Accessed 19 September 2016].

- 4.Culyer A.J. Edward Elgar Publishing; Cheltenham, UK: 2005. The dictionary of health economics. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Manila, Philippines: 2015. Universal health coverage moving towards better health. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . Guiding health systems development in the Western Pacific. World Health Organization West Pacific Regional Office; Manila, Philippines: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda A., Araujo E., Cashin C., Harris J., Ikegami N., Reich M.R. The World Bank; Washington DC: 2014. Universal health coverage for inclusive and sustainable development: a synthesis of 11 country case studies. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrin G., James C. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. Reaching universal coverage via social health insurance: key design features in the transition period. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shin Ja-Eun. KDIS-WB-NHIS-HIRA JLN International Conference conference; South Korea: 2016. A model of delivering universal health coverage. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottert P., Schieber G. The World Bank; Washington DC: 2006. Health financing revisited. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somanathan A., Tandon A., Dao L.H., Hurt K.L., Fuenzalida-Puelma H.L. The World Bank; Washington DC: 2014. Moving toward universal coverage of social health insurance in Vietnam. Assessment and options. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folland S., Goodman A.C., Stano M. seventh edition. Pearson Education; New Jersey, USA: 2013. The economics of health and health care; pp. 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagstaff A. Social health insurance reexamined. Health Econ. 2010;19(5):503–517. doi: 10.1002/hec.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culyer A.J. 3rd ed. Edward Elgar Publishing; Cheltenham, UK: 2014. The dictionary of health economics. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsiao W.C., Shaw R.P. The World Bank; 2007. Social health insurance for developing nations. Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dao H.T., Waters H., Le Q.V. User fees and health service utilization in Vietnam: how to protect the poor? Public Health. 2008;122(10):1068–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabriele A. Social services policies in a developing market economy oriented towards socialism: the case of health system reforms in Vietnam. Rev Int Polit Econ. 2006;13(2):258–289. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolffers I. The role of pharmaceuticals in the privatization process in Vietnam health-care system. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(9):1325–1332. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00415-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tien T.V., Phuong H., Inke M., Phuong N. World Health Organization; 2011. A health financing review of Viet Nam with a focus on social health insurance. Bottlenecks in institutional design and organizational practice of health financing and options to accelerate progress towards universal coverage. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Vietnam Ministry of Health; Hanoi: 2007. Báo cáo 15 năm thực hiện bảo hiểm y tế [15 years progress report of health insurance implementation] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ensor T. Introducing health insurance in Vietnam. Health Policy Plan. 1995;10(2):154–163. doi: 10.1093/heapol/10.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Government of Vietnam . Quyết định số 45-HĐBT ngày 24-4-1989 của Hội đồng Bộ trưởng về việc thu một phần viện phí y tế [Decision no 45-HĐBT on partial hospital fee] Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inter-Ministries of Vietnam . Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance of Vietnam; Hanoi: 1989. Thông tư liên tịch số 14-TTLB của Bộ Y tế - Tài chính - Lao động TBXH - Ban Vật giá chính phủ Hướng dẫn thực hiện thu một phần viện phí [Joint Circular no 14-TTLB on 15-6-1989 about Decision no 45-HĐBT of 24-4-1989 on partial contribution for hospital fees] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaudhuri A., Roy K. Changes in out-of-pocket payments for healthcare in Vietnam and its impact on equity in payments, 1992-2002. Health Policy. 2008;88(1):38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quyết định Số: 217-BYT/QĐ Ban hành quy chế về tổ chức và hoạt động của các bệnh viện, nhà hộ sinh, phòng khám bệnh, phòng xét nghiệm phòng thăm dò chức năng và dịch vụ y tế tư gọi chung là Quy chế về hành nghề y tế tư nhân [Decision no 217-BYT/QĐ on regulating conditions for establishment of private medical practice]

- 26.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Vietnam Ministry of Health; Hanoi: 1989. Quyết định 94-BYT/QĐ ban hành Quy chế về tổ chức mạng lưới kinh doanh thương mại thuốc chữa bệnh thuộc khu vực tập thể và tư nhân (gọi tắt là mở nhà thuốc) nhằm ấn định các nguyên tắc, nhiệm vụ, quyền hạn, phương thức hoạt động của các nhà thuốc [Decision no 94-BYT/QĐ on establishment condititons of pharmacies] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jowett M., Contoyannis P., Vinh N.D. The impact of public voluntary health insurance on private health expenditures in Vietnam. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(2):333–342. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ekman B., Liem N.T., Duc H.A., Axelson H. Health insurance reform in Vietnam: a review of recent developments and future challenges. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(4):252–263. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ha B.T., Frizen S., Thi le M., Duong D.T., Duc D.M. Policy processes underpinning universal health insurance in Vietnam. Global Health Action. 2014;7(24928):24928. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoang C.K., Hill P., Nguyen H.T. Universal health insurance coverage in Vietnam: A stakeholder analysis from policy proposal (1989) to implementation (2014) Journal of Public Health Management & Practice. 2018;24(March/April):S52–S59. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Do N., Oh J., Lee J.S. Moving toward universal coverage of health insurance in Vietnam: barriers, facilitating factors, and lessons from Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(7):919–925. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.7.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vietnam Ministry of Health. Niên giám thống kê y tế [Health Statistics Yearbook 1993 to 2016]. Hanoi: Medicine Publishing House; Various.

- 33.Vietnam Social Security Agency Báo cáo quyết toán tài chính năm 2008 - 2014 [Financial report 2008 - 2014] Vietnam Social Security Agency. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vietnam Social Security Agency . Progress report on Social Health Insurance 2014–2016. Vietnam Social Security Agency; Hanoi: 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vietnam Ministry of Health, World Health Organization. National health account implemented in Vietnam period 1998–2012. Statistical Publishing House; Hanoi: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The World Bank. Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS?locations=VN. [Accessed 31 May 2020].

- 37.Government of Vietnam . Nghị định 299-HĐBT ban hành Nghị định Điều lệ bảo hiểm Y tế [Decree 299-HĐBT on Health Insurance Principles] Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Council of Ministers . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 1988. Quyết định 203-HĐBT của hội đồng bộ trưởng ngày 28-12-1988 về tiền lương công nhân, viên chức hành chính, sự nghiệp, lực lượng vũ trang và các đối tượng hưởng chính sách xã hội [Decision 203-HĐBT on regulating the salaries of workers, civil servants and beneficiaries of social policy] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Government of Vietnam . Nghị định 47-CP ngày 06/6/1994 sửa đổi một số điều của Nghị định số 299-HĐBT ngày 15-8-1992 ban hành Điều lệ bảo hiểm y tế của Hội đồng Bộ trưởng [Decree 47-CP on Health Insurance Principles] Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Vietnam Ministry of Health; Hanoi: 1992. Quyết định 958/BYT-QĐ về việc thành lập Bảo hiểm y tế Việt Nam [Decision no 958/BYT-QĐ on Vietnam Health Insurance Agency establishment] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Vietnam Ministry of Health; Hanoi: 1993. Thông tư của Bộ Y tế số 09-BYT/TT ngày 04 tháng 05 năm 1994 hướng dẫn thực hiện pháp lệnh hành nghề y, dược tư nhân và Nghị định 06/CP ngày 29-01-1994 của chính phủ về cụ thể hóa một số điều trong pháp lệnh hành nghề y, dược tư nhân thuộc lĩnh vực dược [Circular no 09/BYT-TT 17/6/1993 on guiding implementation of private health and pharmaceutical facilities] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inter-Ministries of Vietnam Thông tư liên tịch của Bộ Y tế - Tài Chính - Lao Động - Thương Binh và Xã Hội - Ban Vật giá Chính Phủ số 20/TTLB ngày 23/11/1994 hướng dẫn thực hiện Nghị Định số 95/CP NGÀY 27/8/1994 của Chính Phủ về việc thu một phần viện phí [Circular 20/TTLB on partial hospital fee] Hanoi: Vietnam Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Labor, War Invalids and Social Welfare and Government Price Committee. 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inter-Ministries of Vietnam. Thông tư liên tịch của Bộ Y tế - Tài Chính - Lao động TBXH - Ban Vật giá chính phủ số 14/TTLB ngày 30 tháng 9 năm 1995 Hướng dẫn thực hiện việc thu một phần viện phí [Joint Circular no 14/TTLB on 30/9/1995 about guiding part contribution rate for health service]. Hanoi: Vietnam Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Labor, War Invalids and Social Welfare and Government Price Department; 1995.

- 44.Government of Vietnam. Nghị định số 58/1988/NĐ-CP ngày 13 tháng 8 năm 1989 ban hành Điều lệ bảo hiểm y tế [Decree 58/1998/NĐ-CP on Health Insurance Principles, 13/8/1998]. Hanoi: Government of Vietnam; 1998.

- 45.Government of Vietnam . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2002. Quyết định số 20/2002/QĐ-TTg của Thủ tướng Chính phủ về việc chuyển bảo hiểm y tế Việt Nam sang Bảo hiểm xã hội Việt Nam [Decision no 20/2002/QĐ-TTg of Prime Minister on transition of Vietnam Health Insurance Agency into Vietnam Social Security Agency] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Government of Vietnam . Nghị định số 01/2016/NĐ-CP của Chính phủ: Quy định chức năng, nhiệm vụ, quyền hạn và cơ cấu tổ chức của Bảo hiểm xã hội Việt Nam [Decree 01/2016/NĐ-CP on Functions, Tasks, Authority and Organization Structure of Vietnam Social Security Agency] Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Government of Vietnam . Nghị định 94/2008/NĐ-CP Của Thủ tướng Chính phủ quy định chức năng, nhiệm vụ, quyền hạn và cơ cấu tổ chức của Bảo hiểm xã hội Việt Nam [Decree 94/2008/NĐ-CP on Functions, Tasks, Authority and Organization Structure of Vietnam Social Security Agency] Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inter-Ministries of Vietnam Thông tư liên tịch 14/2007/TTLT-BYT-BTC sửa đổi Thông tư liên tịch 06/2007/TTLT-BYT-BTC hướng dẫn thực hiện bảo hiểm y tế tự nguyện do Bộ Y tế và Bộ Tài chính ban hành [Joint circular on voluntary health insurance] Hanoi: Vietnam Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Government of Vietnam . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2005. Quyết định 196/2005/QĐ-TTg của Thủ tướng Chính phủ về việc thành lập Vụ Bảo hiểm y tế [Decision no 196/2005/QĐ-TTg on establishing Health Insurance Department under Ministry of Health] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Government of Vietnam. Nghị định của Chính phủ số 63/2005/NĐ-CP ngày 16/5/2005 ban hành điều lệ bảo hiểm y tế [Decree 63/2005/NĐ-CP on Health Insurance Principles, 16/5/2005]. Hanoi: Government of Vietnam; 2005.

- 51.National Assembly of Vietnam. Luật Bảo hiểm y tế số 25 [Law on Health Insurance 25]. Hanoi: National Assembly of Vietnam; 2008.

- 52.Government of Vietnam. Quyết định số 538/QĐ-TTg của Thủ tướng Chính phủ . Hanoi; Vietnam Government Cabinet: 2013. Phê duyệt Đề án thực hiện lộ trình tiến tới bảo hiểm y tế toàn dân giai đoạn 2012–2015 và 2020 [Decision 538/QD-TTg on Approving Roadmap Toward Universal Health Insurance Coverage] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Government of Vietnam . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2009. Nghị định 62/2009/NĐ-CP Quy định chi tiết và hướng dẫn thi hành một số điều của Luật bảo hiểm y tế [Decree 62/2009/NĐ-CP Guiding Health Insurance Law 25] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Government of Vietnam . Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2012. Nghị định số 85/2012/NĐ-CP của Chính phủ: Về cơ chế hoạt động, cơ chế tài chính đối với các đơn vị sự nghiệp y tế công lập và giá dịch vụ khám bệnh, chữa bệnh của các cơ sở khám bệnh, chữa bệnh công lập [Decree 85/2012/NĐ-CP about principles of financial mechanism for public health providers] [Google Scholar]

- 55.National Assembly of Vietnam . Luật Bảo hiểm y tế số 46 [Law on Health Insurance 46] National Assembly of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Government of Vietnam . Nghị định số 70/2015/NĐ-CP của Thủ tướng Chính phủ: Quy định chi tiết và hướng dẫn thi hành một số điều của Luật Bảo hiểm y tế đối với Quân đội nhân dân, Công an nhân dân và người làm công tác cơ yếu [Decree 70/2015/NĐ-CP on Detailed Regulation and Guidance on the Health Insurance Implementation for Armed Forces and Police] Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inter-Ministries of Vietnam . Vietnam Ministry of Health, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Labor, War Invalids and Social Welfare; Hanoi: 2015. Thông tư liên tịch số 37/2015/TTLT-BYT-BTC quy định thống nhất giá dịch vụ khám bệnh, chữa bệnh bảo hiểm y tế giữa các bệnh viện cùng hạng trên toàn quốc [Joint Circular no 37/2015/TTLT-BYT-BTC regulate united prices for health services within health facilities at the same technical level] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vietnam Ministry of Health Thông tư 40/2015/TT-BYT quy định đăng ký khám, chữa bệnh bảo hiểm y tế ban đầu và chuyển tuyến khám, chữa bệnh bảo hiểm y tế do Bộ trưởng Bộ Y tế ban hành [Circular no 40/2015/TT-BYT on registration of primary health care faclility under SHI payment] Hanoi: Vietnam Ministry of Health. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Vietnam Ministry of Health; Hanoi: 2015. Đề án triển khai ứng dụng công nghệ thông tin trong quản lý khám, chữa bệnh và thanh toán bảo hiểm y tế [Project on Development of Information Technology for Health Insurance Payment and Management] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Government of Vietnam . Nghị định 166/2016/NĐ-CP quy định về giao dịch điện tử trong lĩnh vực bảo hiểm xã hội, bảo hiểm y tế và bảo hiểm thất nghiệp do Chính Phủ ban hành [Decree 166/2016/NĐ-CP on electronic transactions in social health insurance, social insurance and unemployment insurance] Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vietnam Social Security Agency . Vietnam Social Security Agency; Hanoi: 2017. Tài liệu giao ban Bộ Y tế -BHXH Việt Nam về thực hiện chính sách BHYT [Report on Health Insurance Implementation in 2016] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vietnam Ministry of Health . AIDS-related medical services] Ministry of Health; Hanoi: 2015. Thông tư 15/2015/TT-BYT hướng dẫn thực hiện khám, chữa bệnh bảo hiểm y tế đối với người nhiễm HIV và người sử dụng các dịch vụ y tế liên quan đến HIV/AIDS do Bộ trưởng Bộ Y tế ban hành [Circular on guiding the implementation of medical examination and treatment covered by health insurance for HIV-infected people and users of HIV. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Thông tư 04/2016/TT-BYT quy định về khám, chữa bệnh và thanh toán chi phí khám, chữa bệnh bảo hiểm y tế liên quan đến khám, chữa bệnh lao do Bộ trưởng Bộ Y tế ban hành [Circular no 04/2016/TT-BYT on treatment and payment of TB under social health insurance] Ministry of Health; Hanoi: Vietnam: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Thông tư 40/2014/TT-BYT Ban hành và hướng dẫn thực hiện danh mục thuốc tân dược thuộc phạm vi thanh toán của Quỹ Bảo hiểm y tế [Circular 40/2014/TT-BYT on regulating Medication Drugs List under Health Insurance Benefit] Ministry of Health; Hanoi: Vietnam: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Thông tư 30/2018/TT-BYT ban hành danh mục và tỷ lệ, điều kiện thanh toán đối với thuốc hóa dược, sinh phẩm, thuốc phóng xạ và chất đánh dấu thuộc phạm vi được hưởng của người tham gia bảo hiểm y tế [Essential drug list for social health insurance cardholder] Ministry of Health; Hanoi: Vietnam: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vietnam Ministry of Health Thông tư Liên Bộ Y tế - Tài chính - Lao động - Thương binh và Xã hội số 12/TTLB hướng dẫn thi hành Nghị định số 299-HĐBT ngày 15-8-1992 của Hội đồng Bộ trưởng ban hành điều lệ bảo hiểm y tế [Circular 12/TTLB Guiding Decree 299 on Health Insurance Principles] Hanoi: Vietnam Ministry of Health. 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vietnam Inter-Ministry of Health-Finance . Thông tư liên tịch số 22/2005/TTLT-BYT-BTC ngày 24/8/2005 của liên Bộ Y tế-Tài chính hướng dẫn thực hiện bảo hiểm y tế tự nguyện [Joint Circular No. 22/2005/TTLT-BYT-BTC on August 24, 2005 of the Inter-Ministry of Health-Finance guides the implementation of voluntary health insurance] Vietnam Ministry of Health; Hanoi: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vietnam Inter-Ministry of Health - Finance . Thông tư liên tịch 21/2005/TTLT-BYT-BTC ngày 27-7-2005 của liên Bộ Y tế – Bộ Tài chính hướng dẫn thực hiện BHYT bắt buộc [Joint Circular 21/2005/TTLT-BYT-BTC on July 27, 2005 of the Inter-Ministry of Health - Ministry of Finance to guide the implementation of compulsory health insurance] Vietnam Ministry of Health; Hanoi: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vietnam Ministry of Health . Thông tư 39/2018/TT-BYT quy định thống nhất giá dịch vụ khám bệnh, chữa bệnh bảo hiểm y tế giữa các bệnh viện cùng hạng trên toàn quốc và hướng dẫn áp dụng giá, thanh toán chi phí khám bệnh, chữa bệnh trong một số trường hợp do Bộ trưởng Bộ Y tế ban hành [Circular 39/2018/TT-BYT on unify health service price at same level health facility] Ministry of Health; Hanoi: Vietnam: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ngoc Dung. Sẽ tăng mức đóng BHYT [Social health insurance premium to be increased]: Nguoi Lao Dong; 2016. Available from: https://nld.com.vn/thoi-su-trong-nuoc/se-tang-muc-dong-bhyt-20160909223030462.htm. [Accessed 6 June 2018].

- 72.World Health Organization in South-East Asia. Leave no one behind, make Universal Health Coverage a reality: WHO New Delhi, India 110 002: World Health Organization in South-East Asia; 2016. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/mediacentre/releases/2016/1621/en/. [Accessed 24 May 2018].

- 73.Palmer M.G. Inequalities in universal health coverage: evidence from Vietnam. World Dev. 2014;64:384–394. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mitra S., Palmer M., Mont D., Groce N. Can households cope with health shocks in Vietnam? Health Econ. 2016;25(7):888–907. doi: 10.1002/hec.3196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ministry of Health and Welfare Taiwan . Ministry of Health and Welfare Taiwan; R.O.C. Taiwan: 2015. Taiwan Health and Welfare Report. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kwon S., Lee T., Kim C. Republic of Korea health system review (Health Systems in Transition, Vol. 5 No. 4 2015). Geneva: World Health Organization (on behalf of the Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies); 2015.

- 77.The World Bank . The World Bank; Hanoi: 2017. Implementation completion and results report on a credit in the amount of SDR 41.5 million (US$65.0 million equivalent) to the socialist republic of Vietnam for a central north region health support project. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bach Mai Hospital. Thông tin cơ bản của dự án Hỗ trợ y tế các tỉnh vùng Đông Bắc Bộ và Đồng bằng Sông Hồng [Basic information of the North-East and Red River Delta Regions Health System Support Project – NORRED]; 2015. Available from: http://bachmai.edu.vn/vi/du-an-norred.nd441/gioi-thieu-ve-du-an.i891.bic. [Accessed 18 January 2018].

- 79.The Asian Development Bank Second period of health care in Tay Nguyen Provinces Project: Asian Development Bank. 2014. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-document/81476/44265-013-vie-pds-vi.pdf [02 February 2018]. Available from:

- 80.Tangcharoensathien V., Patcharanarumol W., Kulthanmanusorn A., Saengruang N., Kosiyaporn H. The political economy of UHC reform in Thailand: lessons for low-and middle-income countries. Health Systems & Reform. 2019;5(3):195–208. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2019.1630595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Herzlinger R.E., Richman B.D., Boxer R.J. Achieving universal coverage without turning to a single payer: lessons from 3 other countries. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1409–1410. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Government of Vietnam . Nghị định 92/2011/NĐ-CP về xử phạt vi phạm hành chính trong lĩnh vực bảo hiểm y tế [Decree 92/2011/NĐ-CP on Sanction on Health Insurance Violation] Government of Vietnam; Hanoi: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Social Affairs Committee of Vietnam National Assembly . Báo cáo 525/BC-UBTVQH13 Kết quả giám sát việc thực hiện chính sách, pháp luật về bảo hiểm y tế giai đoạn 2009–2012 [Report 525/BC-UBTVQH13 on Health Insurance Implementation 2009–2012] National Assembly; Hanoi: Vietnam: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tangcharoensathien V., Limwattananon S., Patcharanarumol W., Thammatacharee J., Jongudomsuk P., Sirilak S. Achieving universal health coverage goals in Thailand: the vital role of strategic purchasing. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(9):1152–1161. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bhutan National Medicines Committee . National essential medicines list. Department of Medical Services; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maldives Food and Drug Authority . Maldives Ministry of Health and Family; Male: 2009. Maldives essential medicine list 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Philippine National Drug Committee . The National Formulary Committee - National Drug Policy; Manila, Philippines: 2008. Philippine National Drug Formulary - essential medicines list. [Google Scholar]

- 88.World Health Organization . United Nation Foundation. 10 years of public health progress: How it was done and lessons learned for the future. World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vietnam Ministry of Health. Health Partnership Group . Vietnam Ministry of Health and Health Partnership Group; Hanoi: 2008. Joint annual health review 2008 health financing in Vietnam. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ottersen T., Norheim O.F. Making fair choices on the path to universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92(6):389. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.139139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bao Han, Tuyet Minh. Chống trục lợi bảo hiểm y tế: Sẽ thay đổi cách chi trả [To prevent embezzlement of Social Health Insurance Fund: changing payment mechaism]; 2017. Available from: http://hanoimoi.com.vn/Tin-tuc/Xa-hoi/871235/chong-truc-loi-bhyt-se-thay-doi-phuong-thuc-thanh-toan. [Accessed 02 February 2018].

- 92.Lan Anh. Chia nhỏ dịch vụ để trục lợi quỹ bảo hiểm y tế [Vietnam Social Security: “dividing treatment into seperate services to get more money from health insurance fund”]: Tuoitre.vn; 2017. Available from: https://tuoitre.vn/chia-le-dich-vu-de-an-quy-bao-hiem-1319385.htm. [Accessed 02 February 2018].

- 93.Hoang Manh. Vụ “siết chi” Bảo hiểm xã hội lên tiếng [Case of “refused payment” - Vietnam Social Security responds]: Dantri.com; 2017. Available from: http://dantri.com.vn/suc-khoe/vu-siet-chi-kham-bhyt-bao-hiem-xa-hoi-len-tieng-20170825063219153.htm. [Accessed 02 February 2018].

- 94.Hong Hai. Bệnh viện kêu trời vì bị “siết chi” khám BHYT, Bộ Y tế vào cuộc [Vietnam Social Security Refuses Payment for Health Services - Hospitals Upset, Ministry of Health Objects] Dantri.com; 2017 . Available from: http://dantri.com.vn/suc-khoe/benh-vien-keu-troi-vi-bi-siet-chi-kham-bhyt-bo-y-te-vao-cuoc-20170823171844387.htm. [Accessed 02 February 2018].

- 95.Hien Anh. Người dân “vấp ngã” khi Bảo hiểm và Bộ Y tế không “đều bước” [Patients Suffer when Ministry of Health and Vietnam Social Security Do Not Cooperate Well]: Infonet.vn; 2017. Available from: http://infonet.vn/nguoi-dan-vap-nga-khi-bao-hiem-va-bo-y-te-khong-deu-buoc-post245582.info. [Accessed 02 February 2018].

- 96.Tra Phuong. Bộ Y tế và BHXH 'giằng co' bảo hiểm y tế [Health Insurance in “Tug-of-War” between Ministry of Health and Vietnam Social Security]: Phapluatonline; 2017. Available from: http://plo.vn/thoi-su/bo-y-te-va-bhxh-giang-co-bao-hiem-y-te-708717.html. [Accessed 02 February 2018].

- 97.Lan Anh. Y tế và bảo hiểm 'cự' nhau, quyền lợi người bệnh vẫn mơ hồ [Health sector and Vietnam Social Security in argument, patients' benefits in doubt]: tuoitre.vn; 2017. Available from: https://tuoitre.vn/y-te-va-bao-hiem-cu-nhau-quyen-loi-nguoi-benh-van-mo-ho-20171019165537616.htm. [Accessed 02 February 2018].

- 98.World Health Organization. Self-learning e-course Health Financing Policy for Universal Health Coverage [Training course material]. World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: http://who.campusvirtualsp.org/mod/simplecertificate/verify.php?code=3fa1a2b0-620a-11e7-94fd-6b01b6d03c87. [Accessed 06 July 2017].

- 99.Siverbo S. The purchaser-provider split in principle and practice: experiences from Sweden. Financial Accountability & Management. 2004;20(4):401–420. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mathauer I., Dale E., Meessen B. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Strategic purchasing for universal health coverage: key policy issues and questions: a summary from expert and practitioners’ discussions. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chun C.B., Kim S.Y., Lee J.Y., Lee S.Y. Republic of Korea: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2009;11(7):1–184. [Google Scholar]

- 102.National Health Insurance Service of South Korea. National Health Insurance System Operation Structure 2017 [Available from: http://www.nhic.or.kr/static/html/wbd/g/a/wbdga0401.html]. [Accessed 20 February 2017].

- 103.Prime Minister of Vietnam . Vietnam Government Cabinet Hanoi; 2012. Quyết định số 1202/QĐ-TTg của Thủ tướng Chính phủ: Phê duyệt Chương trình mục tiêu quốc gia phòng, chống HIV/AIDS giai đoạn 2012–2015 [Decision 1202/QD-TTG on approving the National Program on HIV/AIDS Prevention and Treatment in 2012–2015] [Google Scholar]