Abstract

The development and management of health policies, strategies and guidelines (collectively, policies) in many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are often ad hoc and fragmented due to resource constraints a variety of other reasons within ministries of health. The ad hoc nature of these policy processes can undermine the quality of health policy analysis, decision-making and ultimately public health program implementation. To identify potential areas for policy system strengthening, we reviewed the literature to identify potential best practices for ministries and departments of health in LMICs regarding the development and management of health policies. This review led us to identify 34 potential best practices for health policy systems categorized across all five stages of the health policy process. While our review focused on best practices for ministries of health in LMICs, many of these proposed best practices may be applicable to policy processes in high income countries. After presenting these 34 potential best practices, we discuss the potential of operationalizing these potential best practices at ministries of health through the adoption of policy development and management manuals and policy information management systems using the South Africa National Department of Health's experience as an example.

Keywords: Policy development, Policy system strengthening, Policy management, Policy best practices, Policy standards, Policy information

Highlights

-

•

Health policy development processes are often ad hoc, potentially undermining effective implementation.

-

•

Standardizing health policy development could improve effectiveness of health programs.

-

•

The literature reveals 34 potential best practices for health policy systems.

-

•

Standardized policy development processes and policy information systems could facilitate uptake of these best practices.

1. Introduction

The development and management of health policies, strategies and guidelines (collectively, policies) in many low and middle income countries (LMICs) are often ad hoc and fragmented due to a variety of reasons, undermining the quality of policy analysis, decision-making, and ultimately public health program implementation [1]. Poor health policy management practices can unnecessarily lengthen policy development and adoption processes, which can delay scale up of programmatic best practices and scientific breakthroughs. These challenges can be especially pronounced in LMICs where ministries of health often face severe budget constraints that may restrict spending on policy administrative, coordination, and management functions [2]. Once policies are adopted, many LMICs also struggle to effectively implement policies for a variety of reasons, including a lack of financial and human resources, poor policy dissemination, or lack of implementer buy-in. [3] Poor policy practices and weak processes can make it challenging for ministry of health staff to effectively monitor and manage policy processes and performance. Ministry of health investment in policy management will vary by country, as illustrated by variable public health spending rates across LMICs [4]. To avoid confusion of terms, the term “policy” is used to refer to all types of instruments adopted by a health ministry to guide the functioning of the health sector, including policies, strategies and guidelines.

The National Department of Health of the Republic of South Africa (NDoH) partnered with [name of institution redacted for peer review purposes] from 2016 to 2019 on a project to strengthen its policy development and management systems with the goal of improving the quality of NDoH policy processes and strengthening policy implementation. We determined that existing NDoH policies varied in structure, content, and process, and that the NDoH currently lacks a comprehensive database of its existing policies, and inconsistent policy development and management processes, with resultant risks such as conflicts between some policies, insufficient funding for implementation, untended policy consequences which could have been averted through consistent policy analyses. This project attempts to respond to these concerns.

In an effort to identify potential best practices to strengthen NDoH's policy development and management processes, we reviewed the literature but determined that the literature does not offer consolidated guidance on best practices for policy development and management practices in LMICs. To address this gap, we conducted a literature review to identify potential best practices for ministries and departments of health in LMICs regarding the development and management of health policies that could be used to develop greater standardization in various stages of the policy management process. This comprehensive review led us to identify and consolidate 34 potential best practices that are described in this manuscript. After presenting these potential best practices, we discuss NDoH's plans to translate these findings into practice by creating a Manual for the Development and Management for National Health Sector Policies and designing a policy information management system to manage information regarding health policy development and implementation at NDoH.

2. Methods

We conducted an inductive scope review of the literature to identify potential best practices for policy development and management in LMICs. The literature review search parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Literature review methodology.

| Dates searches conducted | November 30, 2016–December 2, 2016 |

|---|---|

| Databases | PubMed |

| Inclusion criteria | Published between 2006 and 2016; indexed on PubMed; accessible through the Library at the authors' institution (online or in print); available in English |

| Search terms | “Policy surveillance”; “policy adoption” AND (Africa OR Low and middle income countries OR LMIC); “policy development” AND (Africa OR Low and middle income countries OR LMIC); “policy analysis” AND (Africa OR low and middle income countries OR LMIC); “policy implementation” AND (Africa OR low and middle income country OR LMIC); “policy evaluation” AND (Africa OR low and middle income countries OR LMIC); “policy process” AND (Africa OR low and middle income countries OR LMIC). |

| Articles responsive after search terms | 642 |

| Secondary inclusion criteria used for abstract screening | Abstract indicates that article addresses how and why policies are analyzed, developed and/or adopted, including influential actors, processes, and context. |

| Responsive articles after abstract screen | 190 |

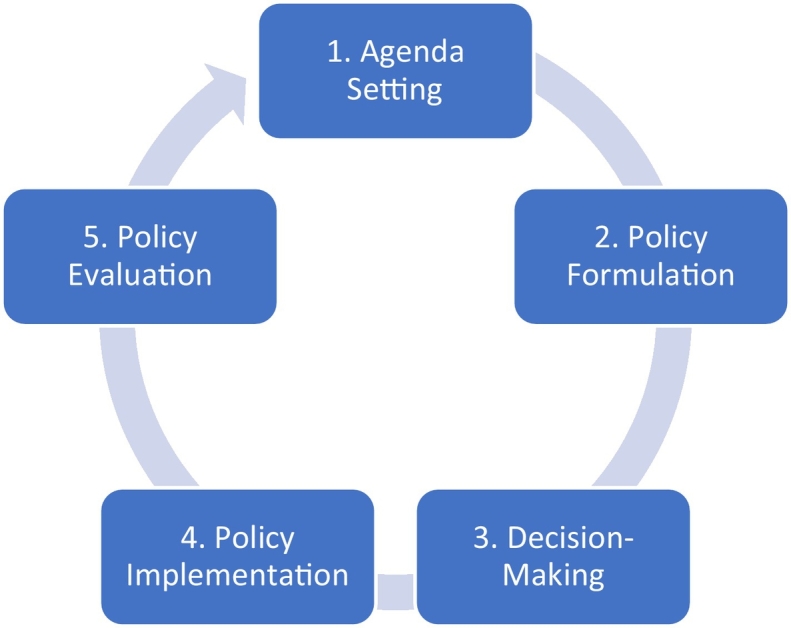

The initial inclusion criteria identified 642 responsive articles. We then conducted an abstract review of the 642 articles applying a secondary inclusion criterion to limit the scope to articles that appear to address how and why policies are analyzed, developed and/or adopted, including influential actors, processes, and context. This secondary inclusion criterion reduced the number of responsive articles to 190. Two co-authors ([co-author initials redacted]) reviewed the 190 responsive articles using inductive grounded theory to identify potential policy process best practices. Articles were coded using Excel and codes were updated throughout the review process in consultation with two additional co-authors ([co-author initials redacted]). We then organized the potential best practices using a 5-stage policy process heuristic adopted by Howlett, Ramesh, and Perl (2009), consisting of the following stages: agenda setting, policy formulation, decision-making, policy implementation, and policy evaluation (see Fig. 1: 5-Stage Policy Cycle). [5] Agenda setting was defined as identifying and describing a public health problem as a priority for governmental action. Policy formulation was defined as identifying and evaluating possible policy options and detailing and drafting a specific policy proposal. Decision-making was defined as the formal process of review and approval of a policy proposal by governmental decision-makers and/or structures. Implementation was defined as the process of carrying out the plan established in the adopted policy, including the development and adoption of related implementation policies, such as regulations, standard operating procedures, or budgets. Evaluation was defined as the process of verifying whether the policy's implementation, and its effects, align with its objectives. A number of potential best practices were coded as applicable to more than one stage.

Fig. 1.

Policy cycle.

3. Results

Our literature review identified 34 potential best practices for policy development and management processes in LMICs that, if adopted, could strengthen the quality of policies developed by ministries and departments of health in LMICs and ultimately increase the likelihood of successful implementation of these policies. Table 2 lists each of the 34 proposed best practices organized by the stage or stages of the policy process where the potential best practice is most applicable.

Table 2.

Potential best practices for policy development and management by stage.

| Policy stage(s) | Potential best practices |

|---|---|

| 1 | Conduct robust situation analysis |

| 1,2 | Facilitate ideas and feedback from key stakeholders (e.g., providers, clients, & researchers) to policymakers |

| 1,2 | Develop clearly defined problem statements |

| 1,2 | Provide policymakers access to resources with current evidence (e.g. eLibrary access, access to researchers) |

| 1,2 | Conduct stakeholder analysis |

| 2 | Brainstorm possible interventions to address problem statement |

| 2 | Analyze potential interventions using expressly defined criteria (e.g. multi-criteria decision analysis) |

| 2,3 | Develop stakeholder engagement plan to ensure input from all relevant stakeholders (e.g., geographic, key populations, implementers) |

| 2 | Model implementation to identify potential implementation barriers |

| 2 | Model policy implementation on work load burden |

| 2 | Consider impact of staff turnover on policy implementation |

| 2 | Conduct a policy conflict analysis |

| 2 | Estimate potential change in resource needs over time |

| 2,4 | Identify sources of funding |

| 2 | Policies should be clear and areas of flexibility should be expressly acknowledged |

| 2,5 | Clearly define targets, objectives, goals and indicators |

| 2,5 | Include clear implementation targets with timelines |

| 2,5 | Establish consistent framework for M&E plans |

| 2,5 | Identify and coordinate M&E system(s)/data sources |

| 3 | Standardize definitions & adoption processes for different types of policies |

| 3 | Establish consistent requirements for who should review and who must adopt different types of policies |

| 4 | Disseminate policies through push and pull mechanisms to all relevant stakeholders |

| 4 | Provide sufficient role-specific training on policy details |

| 4 | Educate all key stakeholders on policy components (e.g., implementers, consumers, traditional practitioners, private sector) |

| 4 | Verify knowledge of policy details by key stakeholders |

| 4 | Empower managers to provide guidance and support to front line implementers |

| 4 | Empower frontline implementers to engage in policy development and implementation processes |

| 4 | Designate champions/ leaders responsible for implementation at each level |

| 4 | Ensure strong financial management throughout implementation |

| 5 | Engage in regular implementation monitoring using implementation indicators identified in monitoring plan |

| 5 | Monitor availability of inputs/supplies/drugs for Policy compliance |

| 5 | Conduct evaluation when required by policy |

| 5 | Ensure evaluation is transparent and verifiable |

| 5,1 | Use results of policy evaluation to inform policymaking processes |

3.1. Stage 1 – agenda setting

Our review identified five potential best practices in the agenda setting stage.

3.1.1. Conduct robust situational analysis

The literature identified the importance of conducting a robust situational analysis to understand the contextual factors contributing to specific public health problems [3,6]. The goal of a situational analysis is to develop a common understanding of contextual factors affecting a public health problem. These contextual factors can include economic, social, racial, historical, cultural, political, gender, technological, and institutional considerations. Situational analyses can include both qualitative and quantitative data. The time frame for the situation analysis should examine the current context and sufficient historical context to identify relevant trends.

3.1.2. Facilitate ideas and feedback from key stakeholders to policymakers

Our review identified the importance of soliciting ideas and feedback from key stakeholders to policymakers during the agenda setting and policy formulation stages [7., 8., 9., 10., 11., 12., 13., 14., 15., 16.]. Stakeholders can and should include a wide range of perspectives, such as health care providers, public health practitioners, patients, community members, advocates, and researchers. Methods could include open consultative forums, surveys, and interviews. This proactive engagement can help improve the diversity of perspective reflected in the situation analysis and policy formulation.

3.1.3. Develop clearly defined problem statements

We identified the importance of developing clearly defined problem statements as part of the agenda setting stage [9., 10., 11.,13]. Developing these problem statements helps to adequately describe issues that need to be addressed through policy action. This is an important step to having a common internal frame of the problems – and their relative importance – that need to be addressed in the policy development process [17].

3.1.4. Facilitate policymaker access to resources with current evidence

The literature showed the importance of facilitating policymaker access to resources with current evidence, to facilitate evidence-informed situational analyses and subsequently identifying potential interventions in the policy formulation stage [3,8,12,14,15,18., 19., 20., 21., 22.]. These resources could include access to online libraries or systematic linkages to experts (e.g., researchers, think tanks, or policy research units within ministries or departments of health).

3.1.5. Conduct stakeholder analyses

The literature pointed to the importance of conducting a stakeholder analysis as part of the agenda setting and policy formulation stages [21., 22., 23.]. Ongoing stakeholder analyses are important to identify key interests at stake, their views of the policy issue and its importance, how optional policy interventions might align or conflict with those interests, and whether certain groups may be disproportionately burdened or benefited by the policy proposal, which may affect the relative equity of each proposal. As policy proposals become increasingly detailed and evolve, stakeholder analyses often need to be updated.

3.2. Stage 2 - policy formulation

Our review identified fourteen potential best practices that primarily align with the policy formulation stage.

3.2.1. Brainstorm possible interventions to address problem statement

We identified the importance of thinking broadly and creatively about possible interventions to address public health problems identified during the situation analysis [6,9,13,16,22., 23., 24.]. This brainstorming process should include thinking about the various levers of influence available to governments, including direct service provision, taxation, regulation, insurance mechanisms, and purchasing power. Often policy proposals are limited to direct service delivery proposals, when governments have other mechanisms at their disposal that can have a substantial impact on health systems and health outcomes (e.g. taxes on tobacco products to reduce consumption or regulations mandating benefits in commercial insurance products to facilitate uptake of beneficial therapies).

3.2.2. Analyze potential interventions using expressly defined criteria

The literature revealed the importance of analyzing and comparing possible interventions using expressly defined criteria. [9,13,25] One method for conducting this analysis is multi-criteria decision analysis. Under this method, specific criteria are selected, and each intervention is scored against each selected criterion. The total scores for each intervention are then compared to facilitate a prioritization process. Other forms of intervention analysis can also be used, such as: Program Budgeting and Marginal Analysis (PBMA); Propriety, Economics, Acceptability, Resources and Legality component (PEARL); Multi-Voting Technique; and the Delphi technique [26].

3.2.3. Develop stakeholder engagement plan to ensure input from all relevant stakeholders

To ensure adequate stakeholder input during the analysis stage, a stakeholder engagement plan should be developed and followed to ensure input from all relevant stakeholders (e.g., geographic, key populations, and implementers). [7,11,14,27] In contrast to ad hoc stakeholder consultations, developing a thoughtful stakeholder engagement plan can help ensure that a broad array of key stakeholders are engaged in the policy development process at critical points, including during policy conceptualization and prioritization processes.

3.2.4. Model implementation to identify potential implementation barriers

The literature revealed the importance of policy implementation modeling, such as creating an implementation logic model [7,28,29]. Implementation modeling requires that the policy development team develop its intervention proposals to a relatively detailed stage to facilitate detecting potential barriers to effective implementation during the policy development phase. If these barriers are identified during the policy development phase, the team can integrate proactive strategies into their policy proposal to address and overcome these barriers, instead of waiting to identify and address these during implementation. An implementation logic model or theory of change framework can be used to support implementation modeling.

3.2.5. Model policy implementation on work load

The literature supported the importance of modeling policy implementation on work load burden of implementers [16,28,32., 33., 34., 35., 36., 37., 38., 39., 40., 41., 42., 43., 44., 45., 46., 47., 48., 49.]. Modeling work load burden was primarily discussed in the context of clinical settings. For example, do nurses in public clinics have the time to conduct an additional screening for a new priority condition? If the additional screening is added, what effect will that have on the number of patients that can be seen by that nurse each day? Identifying work load burden-related barriers in the development stage may lead to consideration as to whether, for example, a task-sharing approach will be necessary to effectively roll out the intervention at scale.

3.2.6. Consider impact of staff turnover on policy implementation

Teams should consider the impact of staff turnover on policy implementation and training [7,34,36,37,40,41,44,46,49., 50., 51.]. Many health systems, especially in rural areas, suffer from chronic turnover of staff. Frequent turnover can undermine training health care providers and other implementers on a new policy. Online or virtual learning modalities may be one method to help address the impact of staff turnover by allowing new staff to be oriented to all relevant policies during their initial orientation process. In addition, long processes for mentorship or supervision may also be challenging to implement in areas with high staff turnover.

3.2.7. Conduct a policy conflict analysis

As part of the analysis process, the literature showed the importance of conducting a policy conflict analysis before adopting the policy [3,6,9,10,16,30,31]. Conflict analyses compare a draft policy with existing policies and laws and can help identify other policies that may need to be updated to ensure a consistent policy framework. Reliable access to a searchable, comprehensive database of governmental policies and laws is necessary to conduct effective policy conflict analyses.

3.2.8. Conduct a costing analysis that estimates resource needs over time

A costing analysis of policy proposal should estimate potential changes in resource needs over time [3,27,36,40., 41., 42.,48,52., 53., 54., 55., 56., 57., 58., 59., 60., 61., 62., 63., 64., 65., 66.]. Frequently the resource needs of specific policies fluctuate over time. For example, a policy may require relatively high resources at the outset to fund the initial rollout, but then its resource needs may decline over time once the delivery system is established. Alternatively, a policy may require relatively few resources at the outset with significant additional resources required over time as the service is made available at a wider array of facilities or beneficiaries.

3.2.9. Identify sources of funding

Policy processes should identify sources (e.g., dedicated funds, general funds, donor funds) and levels of funding for implementation, including supply chain [3,27,35,38,48,54,55,63,67., 68., 69., 70., 71.]. In many countries, budget processes occur separately from policy processes led by ministries or departments of health. This bifurcation often leads to policies being adopted by ministries of health without clear costing analysis or, if costing analysis is conducted, adequate funds are not allocated during the budget process to effectively implement the policy. The literature emphasized the need to better align budget, finance, and taxation processes with policy development processes overseen by ministries of health.

3.2.10. Policies should be clear and areas of flexibility should be expressly acknowledged

The literature pointed to the importance of drafting policies in plain language and expressly acknowledging areas of flexibility [3,11,29,31,40,44,60., 61., 62., 63., 64., 65., 66.,69,72., 73., 74., 75., 76., 77., 78., 79.]. This clarity is critical to facilitate consistent and reliable interpretation of the policy by implementers, community members, and other key stakeholders. Clarity in national policies may also be necessary to ensure consistent adoption and implementation by subnational units in decentralized countries, which may have some authority and autonomy to adapt national policies to their local contexts.

3.2.11. Clearly define targets, objectives, goals and indicators

Policies should have clearly defined targets, objectives, goals, and indicators [29,33,40,41,52,59., 60., 61.,67,68,80., 81., 82., 83., 84.]. Policies often have a great deal of variability in whether and how policy targets, objectives, goals, and indicators are included and defined.

3.2.12. Include clear implementation targets with timelines

Policy targets should include timelines against which progress can be measured [27,29,33,40,52,54,60,61,67,79., 80., 81., 82., 83.]. These timelines are critical to performance management of policy implementation processes.

3.2.13. Establish consistent framework for M&E plans

To facilitate management of policies across a ministry or department of health, the literature supported establishing consistent frameworks for M&E plans [11,21,29,33,41,57,60,68,72,74,83,85., 86., 87., 88.]. Having a consistent M&E framework to outline expected reporting systems, frequency, and data will allow ministry leadership to more easily assess implementation progress across a range of policies.

3.2.14. Identify and coordinate M&E system(s)/data sources

When developing policy implementation M&E plans, existing M&E system(s) and data sources should be used when possible instead of creating a new or standalone M&E system for each new policy [33,47,52., 53., 54.,70,83,87,89]. Establishing new M&E systems and data feeds can be costly and time-consuming, which can deplete limited resources that may be better targeted at policy implementation activities. In addition, establishing new data collection processes can take many months or even years to establish.

3.3. Stage 3 – decision-making

Our review identified two potential best practices applicable to the decision-making or adoption stage.

3.3.1. Standardize definitions for different types of policies

The literature discusses the importance of standardizing definitions for different types of policies. Often ministries of health develop a range of different types of policies with different purposes, including guidelines, strategies, frameworks, and standard operating procedures. Often the content and objectives of these different policy types overlap, but developing standard definitions will be important for standardizing structure and review procedures for different policy types [7,14,16,18,29,69,77,86,90].

3.3.2. Establish consistent requirements for review and approval of different types of policies

The literature pointed to the importance of standardizing the review and approval processes for different policy types. The level of review may be different depending on the type of policy. For example, a policy may require a higher level of review than a standard operating procedure. Standardizing these review and approval processes could make the processes more predictable and potentially more streamlined and efficient [3,10,12,16,52,69,91., 92., 93.].

3.4. Stage 4 – implementation

Our review identified eight potential best practices for the implementation stage.

3.4.1. Disseminate policies through push and pull mechanisms to all relevant stakeholders

Policies should be disseminated through push and pull mechanisms to all relevant stakeholders [7,19,52,54,58,59,61,64,68,70,72,77., 78., 79.,91,94., 95., 96., 97., 98., 99., 100., 101.]. Push communication strategies include mechanisms to proactively send content to implementers and community members, such as distributing hardcopies of policies at health facilities. Pull communication mechanisms refer to passive dissemination mechanisms that allow users to access the policy when needed by the user, such as by posting the policy on an accessible website. Push and pull approaches recognize that some implementers may only need access to a policy intermittently, and at those times they should be able to access the policy in a central location, in paper or electronic form.

3.4.2. Provide sufficient role-specific training on policy details

Sufficient education and training should be provided to implementers on policy details, and this training must be relevant to their role in policy implementation. [7,28,29,31,33,35,36,38,39,41,42,51,54,58,59,61,62,64,68,70,72,74,95,102., 103., 104.] This may require that different training curriculum or materials be developed for different cadres.

3.4.3. Educate key stakeholders on policy components

Key components of the policy should be communicated to all key stakeholders, not just implementers (e.g., consumers, traditional practitioners or private sector) [7,11,19,28,29,36,39,52,54,61,68,78,86,88,98,105., 106., 107.]. Community education initiatives can take many forms, including media campaigns, civil society outreach, and making policy documents publicly available on governmental or facility websites. Making policies available in local languages and dialects and with nontechnical language summaries may also be necessary to ensure that key stakeholders can understand how policies may affect them.

3.4.4. Verify knowledge of policy details by key stakeholders

The knowledge of key implementers about policy details should be verified [7,28,29,31,38,47,54,68,95,98]. Often, policy training programs may fail to effectively transfer the necessary knowledge to key implementers. To ensure that policy trainings are transferring the necessary information to implementers, trainings should verify trainee knowledge and understanding of their role in the policy process. These training verifications can be implemented via paper tests or online training modules that ask the trainees to correctly answer certain key questions before they can proceed to the next section of the training.

3.4.5. Empower managers to provide guidance and support to front line implementers

Frontline managers should be empowered to provide guidance and support to front line implementers [29,31,32,35,36,38,39,41,43,51,61,66,68,69,75,92,96,102,107., 108., 109., 110.]. This may require more in-depth training for managers so implementers have a local resource to answer questions about how a policy should be interpreted in a particular situation. These managers may also need to be connected with other managers or resources at district, provincial, or national departments of health who can provide guidance to them when required.

3.4.6. Empower frontline implementers to engage in policy development and implementation processes

Frontline implementers should be empowered to engage in policy development and implementation processes [29,31,36,45,50,51,56,64,65,69,92,95,102,104,106., 107., 108.,111., 112., 113.]. Engagement of frontline implementers in the policy development and implementation process was cited broadly in the literature as key to policy implementation success. The power of frontline implementers to affect policy implementation is sometimes referred to as “street-level bureaucracy” because often frontline implementers have a tremendous amount of power in practice to decide whether and how to implement policies [107]. Engaging these implementers in the policy development process can help improve the likelihood that they will be accepting of and willing to play their role in the policy implementation process, as envisioned in the adopted policy.

3.4.7. Designate champions/ leaders responsible for implementation at each level

Champions and leaders responsible for implementation should be designated at each level (e.g., provincial, district, and facility-level) [7,22,23,28,32,35,36,43,44,51,53,60,77,96]. The literature revealed the importance of identifying these champions and leaders at each level to provide accountability and support for implementation at each level of government.

3.4.8. Ensure strong financial management throughout implementation

Ministries of health and finance must ensure strong financial management throughout implementation [16,27,28,35,48,52., 53., 54., 55.,63,89,101,114]. Costing analysis, budget impact analysis, and financial planning are important to successful policy implementation, but these resources must also be managed effectively during policy implementation phases. Financial management and accounting systems will be necessary to strengthen financial management of funds and resources critical to policy implementation.

3.5. Stage 5 – evaluation

Our review identified five potential best practices that primarily align with the evaluation stage.

3.5.1. Engage in regular implementation monitoring

Ministries and departments of health should engage in regular implementation monitoring using indicators identified in the monitoring plan [15,16,29,33,39., 40., 41.,48,52,54,62,64,83,87,106]. Regular monitoring, using readily and inexpensively available information, can help identify unforeseen barriers to implementation early in the rollout or on an ongoing basis so they can be addressed in real-time.

3.5.2. Monitor availability of inputs/supplies/medicines for policy compliance

The literature emphasized the need to monitor the availability of policy inputs, such as medical supplies and medicines [33,35,55,60,63,64,67,68,79,95,101,103]. Various supply chain management systems have been established to monitor health system input availability and access. Establishing and maintaining such a system will be critical for the successful implementation of policies that rely on the availability of certain commodities. The quality of these commodities will also need to be monitored to identify substandard commodities that may compromise quality of health service provision.

3.5.3. Conduct evaluation when required by policy

An evaluation should be conducted when required by the policy [27,28,33,52,54,64,80,81,85,103,106,115]. Many policies include a requirement that a policy evaluation be conducted a certain number of years after implementation. Unfortunately, these evaluations are frequently not conducted either due to management oversight, lack of human resources capacity, or lack of funding to conduct the evaluation. The cost of conducting the evaluation should be included in the costing analysis to help ensure that funding is available for policy evaluation activities. Due to financial or time constraints, it may not be feasible to conduct an in-depth evaluation of every policy, so ministries and departments of health, in consultation with key stakeholders, should think strategically about what evaluation methods are appropriate for each policy.

3.5.4. Ensure evaluation is transparent and verifiable

Policy evaluations should be transparent [15,28,33,53,54,82,83,109,114]. Policy evaluations are more powerful if their methodologies can be validated by key stakeholders and the public. Publishing the evaluation results, including the methodology used to conduct the evaluation, can help build the credibility of the recommendations.

3.5.5. Use results of policy evaluation to inform policymaking processes

The results of policy monitoring and evaluation should be used to inform policy revisions and future policy development [15,21,33,37,81,85,87,94,103,116., 117., 118., 119.]. For example, policy monitoring and evaluation results could be required to be presented to ministry leadership and/or to public stakeholders to improve the likelihood of the results being used to inform future policy decisions. Evaluation results can also be shared publicly to facilitate buy-in or advocacy by civil society organizations for continuous performance improvement.

4. Discussion

The 34 potential best practices in this manuscript present a framework for governments, especially in LMICs, to review their existing processes with an eye toward greater standardization and improved management.

One step that governments could take to integrate these considerations into practice is to develop a manual, guide, or internal directive that standardizes policy processes and incorporates these best practices at the appropriate stage. Table 3 lists examples of these types of guides.

Table 3.

Examples policy development manuals.

| Title | Government agency | Year |

|---|---|---|

| A Practical Guide to Policy Making in Northern Ireland | Northern Ireland Executive, Ireland | 2016 |

| A Guide to Policy Development | Office of Auditor General, Manitoba, Canada | 2003 |

| Alberta Health Services Policy Development Framework | Alberta Health Services, Alberta, Canada | 2016 |

| A Guide to Policy Development and Management | Republic of Uganda | 2013 |

| National Guide for the Health Sector and Strategic Plan Development | Ministry of Health, Republic of Rwanda | 2014 |

| Standard Operating Procedures of the Directorate General of Planning and Health Information System | Ministry of Health, Republic of Rwanda | 2014 |

| Policy Development Guidelines for Ministry of Health | Ministry of Health, Government of Fiji | 2014 |

| A Manual for Policy Analysts | Government of Jamaica | 2002 |

| Policy for the Development of the North West Department of Health Policies and Standard Operating Procedures | Department of Health; North West Province, Republic of South Africa | 2017 |

| Departmental Policy Development Framework | Department of Sport, Art and Culture; Limpopo Province, Republic of South Africa | 2012 |

| Amathole District Municipality Policy Development Framework | Amathole District Municipality, Republic of South Africa | 2014 |

| Policy on Policies (Development, Writing, and Implementation) | Department of Health; Northern Cape Province, Republic of South Africa | 2013 |

| Framework for the Development and Quarterly Monitoring of the Annual Performance Plans (APPs) and the Operational Plans of the National Department of Health | National Department of Health, Republic of South Africa | 2012 |

The South Africa NDoH has developed a Manual on the Development and Management of National Health Policies that was informed by best practices identified in this manuscript. The manual includes sections on definitions and key terms, required processes, and formats (or structure) of different types of policies. The manual also includes resource guides on defining public health problems and conducting a situational analysis; analyzing possible policy interventions; stakeholder analysis; implementation modeling; policy costing; implementation monitoring; policy evaluation; and tools and checklists to support these key policy activities. NDoH hopes this manual will act as both an educational resource and management tool to strengthen NDoH policy processes and improve programmatic rollout of strategic priorities.

The South Africa NDoH also identified a need for a digitsed system to manage the policy development and implementation processes. To address this need, NDoH developed a policy information management system which aims to: improve the ability of leadership to know the status of policies and to monitor progress in developing and reviewing policies; provide tools for NDoH managers to support the policy development and review process; aggregate documents and data associated with specific policies to improve policy implementation and monitoring; and make policies more readily accessible to frontline clinicians and the public. The system was designed to include a comprehensive database of policies organized by type of policy and health topic. The system also includes functionality for managing policy drafts and associated situation and health policy analysis documents, to support managers during the policy development process.

5. Conclusion

The 34 potential best practices presented in this manuscript provides a structure for standardizing and strengthening the very complex processes of health policy development, management and implementation by ministries of health in LMICs. This list is intended as illustrative and not exclusive. The authors hope that health policy professionals and researchers build on and refine this list in support of strengthening health policy processes globally. Champions will also be required to translate policy best practices into operationalized procedures and practices within ministries and departments of health. South Africa's NDoH is embarking on such a path by adopting a Manual for the Development and Management for National Health Policies, and an associated policy information management system. Its approach may be a useful model for ministries and departments of health in other LMICs.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jeffrey Lane: Conceptualization; Writing-Original Draft Gail Andrews: Conceptualization; Writing – Review & Editing Erica Orange: Investigation; Writing – Review & Editing Audrey Brezak: Investigation; Writing – Review & Editing Gaurang Tanna: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing Lebogang Lebese: Conceptualization; Writing – Review & Editing Terence Carter: Writing – Review & Editing Evasen Naidoo: Conceptualization; Writing – Review & Editing Elise Levendal: Writing – Review & Editing Aaron Katz: Conceptualization; Writing-Review & Editing

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: This research is a product of the University of Washington International Training and Education Center for Health and was supported by the United States President's Emergency Plan for Aids Relief (PEPFAR) through the U. S. Health Resources and Services Administration under Cooperative Agreement number 5 U91HA0680112. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors.

References

- 1.Lavis J.N., Oxman A.D., Lewin S., Fretheim A. SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 3: setting priorities for supporting evidence-informed policymaking. Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7(Suppl. 1):S3. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottret P., Schieber G. World Bank; Washington, DC: 2006. Health financing revisited: a practitioner's guide. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Erasmus E., Orgill M., Schneider H., Gilson L. Mapping the existing body of health policy implementation research in lower income settings: what is covered and what are the gaps? Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(Suppl. 3):iii35. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu063. [50] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Organization WH. Global spending on health: a world in transition. Geneva; 2019. Contract No.: WHO/HIS/HGF/HFWorkingPaper/19.4.

- 5.Howlett M., Ramesh M., Perl A. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; 2009. Studying public policy policy cycles & policy subsystems. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dar O.A., Hasan R., Schlundt J., Harbarth S., Caleo G., Dar F.K., et al. Exploring the evidence base for national and regional policy interventions to combat resistance. Lancet. 2016;387(10015):285–295. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00520-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Draper C.A., Draper C.E., Bresick G.F. Alignment between chronic disease policy and practice: case study at a primary care facility. PLoS One. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ellen M.E., Leon G., Bouchard G., Ouimet M., Grimshaw J.M., Lavis J.N. Barriers, facilitators and views about next steps to implementing supports for evidence-informed decision-making in health systems: a qualitative study. Implement Sci. 2014;9:179. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0179-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berlan D., Buse K., Shiffman J., Tanaka S. The bit in the middle: a synthesis of global health literature on policy formulation and adoption. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(Suppl. 3):iii23. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu060. [34] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Awenva A.D., Read U.M., Ofori-Attah A.L., Doku V.C., Akpalu B., Osei A.O., et al. From mental health policy development in Ghana to implementation: what are the barriers? Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg) 2010;13(3):184–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S., Myburgh N.G., Lalloo R. Policy analysis of oral health promotion in South Africa. Glob Health Promot. 2010;17(1):16–24. doi: 10.1177/1757975909356631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cliff J., Lewin S., Woelk G., Fernandes B., Mariano A., Sevene E., et al. Policy development in malaria vector management in Mozambique, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(5):372–383. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavis J.N., Oxman A.D., Grimshaw J., Johansen M., Boyko J.A., Lewin S., et al. SUPPORT Tools for evidence-informed health Policymaking (STP) 7: finding systematic reviews. Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7(Suppl. 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Politis C.E., Halligan M.H., Keen D., Kerner J.F. Supporting the diffusion of healthy public policy in Canada: the prevention policies directory. Online J Public Health Inform. 2014;6(2) doi: 10.5210/ojphi.v6i2.5372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilson L., Raphaely N. The terrain of health policy analysis in low and middle income countries: a review of published literature 1994-2007. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):294–307. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheikh K., Saligram P.S., Hort K. What explains regulatory failure? Analysing the architecture of health care regulation in two Indian states. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(1):39–55. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiffman J., Smith S. Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1370–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akhlaq A., McKinstry B., Muhammad K.B., Sheikh A. Barriers and facilitators to health information exchange in low- and middle-income country settings: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(9):1310–1325. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El-Jardali F., Lavis J., Moat K., Pantoja T., Ataya N. Capturing lessons learned from evidence-to-policy initiatives through structured reflection. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andermann A., Pang T., Newton J.N., Davis A., Panisset U. Evidence for health II: overcoming barriers to using evidence in policy and practice. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:17. doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0086-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nabyonga-Orem J., Mijumbi R. Evidence for informing health policy development in Low-income Countries (LICs): perspectives of policy actors in Uganda. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(5):285–293. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2015.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woelk G., Daniels K., Cliff J., Lewin S., Sevene E., Fernandes B., et al. Translating research into policy: lessons learned from eclampsia treatment and malaria control in three southern African countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2009;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wenger E. How we learn. Communities of practice. The social fabric of a learning organization. Healthc Forum J. 1996;39(4):20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burris S.C., Anderson E.D. Making the case for laws that improve health: the work of the Public Health Law Research National Program Office. J Law Med Ethics. 2011;39(Suppl. 1):15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2011.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mirelman A., Mentzakis E., Kinter E., Paolucci F., Fordham R., Ozawa S., et al. Decision-making criteria among national policymakers in five countries: a discrete choice experiment eliciting relative preferences for equity and efficiency. Value Health. 2012;15(3):534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Organization WH . 2016. Strategizing national health in the 21st century: a handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasanathan K., Muniz M., Bakshi S., Kumar M., Solano A., Kariuki W., et al. Community case management of childhood illness in sub-Saharan Africa - findings from a cross-sectional survey on policy and implementation. J Glob Health. 2014;4(2) doi: 10.7189/jogh.04.020401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mugwagwa J., Edwards D., de Haan S. Assessing the implementation and influence of policies that support research and innovation systems for health: the cases of Mozambique, Senegal, and Tanzania. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:21. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Belaid L., Ridde V. An implementation evaluation of a policy aiming to improve financial access to maternal health care in Djibo district, Burkina Faso. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ditlopo P., Blaauw D., Penn-Kekana L., Rispel L.C. Contestations and complexities of nurses' participation in policy-making in South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25327. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheikh K., Porter J. Discursive gaps in the implementation of public health policy guidelines in India: the case of HIV testing. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(11):2005–2013. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gilson L., Elloker S., Olckers P., Lehmann U. Advancing the application of systems thinking in health: South African examples of a leadership of sensemaking for primary health care. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014;12:30. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawonga M., Blaauw D., Fonn S. Aligning vertical interventions to health systems: a case study of the HIV monitoring and evaluation system in South Africa. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012;10:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-10-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cailhol J., Craveiro I., Madede T., Makoa E., Mathole T., Parsons A.N., et al. Analysis of human resources for health strategies and policies in 5 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, in response to GFATM and PEPFAR-funded HIV-activities. Global Health. 2013;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olinyk S., Gibbs A., Campbell C. Developing and implementing global gender policy to reduce HIV and AIDS in low- and middle-income countries: policy makers' perspectives. Afr J AIDS Res. 2014;13(3):197–204. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2014.907818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daniels K., Clarke M., Ringsberg K.C. Developing lay health worker policy in South Africa: a qualitative study. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buchan J., Couper I.D., Tangcharoensathien V., Thepannya K., Jaskiewicz W., Perfilieva G., et al. Early implementation of WHO recommendations for the retention of health workers in remote and rural areas. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(11):834–840. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moetlo G.J., Pengpid S., Peltzer K. An evaluation of the implementation of integrated community home-based care services in Vhembe district. South Africa Indian J Palliat Care. 2011;17(2):137–142. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.84535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sato M., Gilson L. Exploring health facilities' experiences in implementing the free health-care policy (FHCP) in Nepal: how did organizational factors influence the implementation of the user-fee abolition policy? Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(10):1272–1288. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crawley J., Hill J., Yartey J., Robalo M., Serufilira A., Ba-Nguz A., et al. From evidence to action? Challenges to policy change and programme delivery for malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7(2):145–155. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uwimana J., Jackson D., Hausler H., Zarowsky C. Health system barriers to implementation of collaborative TB and HIV activities including prevention of mother to child transmission in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17(5):658–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanefeld J. The impact of Global Health initiatives at national and sub-national level - a policy analysis of their role in implementation processes of antiretroviral treatment (ART) roll-out in Zambia and South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22(Suppl. 1):93–102. doi: 10.1080/09540121003759919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dieleman M., Shaw D.M., Zwanikken P. Improving the implementation of health workforce policies through governance: a review of case studies. Hum Resour Health. 2011;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dambisya Y.M., Matinhure S. Policy and programmatic implications of task shifting in Uganda: a case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:61. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Minzi O.M., Haule A.F. Poor knowledge on new malaria treatment guidelines among drug dispensers in private pharmacies in Tanzania: the need for involving the private sector in policy preparations and implementation. East Afr J Public Health. 2008;5(2):117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deller B., Tripathi V., Stender S., Otolorin E., Johnson P., Carr C. Task shifting in maternal and newborn health care: key components from policy to implementation. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(Suppl. 2):S25–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Agyepong I.A., Abankwah D.N., Abroso A., Chun C., Dodoo J.N., Lee S., et al. The "Universal" in UHC and Ghana's National Health Insurance Scheme: policy and implementation challenges and dilemmas of a lower middle income country. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):504. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1758-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sheikh K., Uplekar M. What can we learn about the processes of regulation of tuberculosis medicines from the experiences of health policy and system actors in India, Tanzania, and Zambia? Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(7):403–415. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hanefeld J., Musheke M. What impact do Global Health initiatives have on human resources for antiretroviral treatment roll-out? A qualitative policy analysis of implementation processes in Zambia. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kouanda S., Yameogo W.M., Ridde V., Sombie I., Baya B., Bicaba A., et al. An exploratory analysis of the regionalization policy for the recruitment of health workers in Burkina Faso. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12(Suppl. 1):S6. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-S1-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schneider H., English R., Tabana H., Padayachee T., Orgill M. Whole-system change: case study of factors facilitating early implementation of a primary health care reform in a South African province. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:609. doi: 10.1186/s12913-014-0609-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faydi E., Funk M., Kleintjes S., Ofori-Atta A., Ssbunnya J., Mwanza J., et al. An assessment of mental health policy in Ghana, South Africa. Uganda and Zambia Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:17. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jenkins R., Mussa M., Haji S.A., Haji M.S., Salim A., Suleiman S., et al. Developing and implementing mental health policy in Zanzibar, a low income country off the coast of East Africa. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Witter S., Garshong B., Ridde V. An exploratory study of the policy process and early implementation of the free NHIS coverage for pregnant women in Ghana. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:16. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sambo L.G., Kirigia J.M., Ki-Zerbo G. Health financing in Africa: overview of a dialogue among high level policy makers. BMC Proc. 2011;5(Suppl. 5):S2. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S5-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jolley G., Freeman T., Baum F., Hurley C., Lawless A., Bentley M., et al. Health policy in South Australia 2003-10: primary health care workforce perceptions of the impact of policy change on health promotion. Health Promot J Austr. 2014;25(2):116–124. doi: 10.1071/HE13088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paul C., Kramer R., Lesser A., Mutero C., Miranda M.L., Dickinson K. Identifying barriers in the malaria control policymaking process in East Africa: insights from stakeholders and a structured literature review. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:862. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2183-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Witter S., Dieng T., Mbengue D., Moreira I., De Brouwere V. The national free delivery and caesarean policy in Senegal: evaluating process and outcomes. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(5):384–392. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ganaba R., Ilboudo P.G.C., Cresswell J.A., Yaogo M., Diallo C.O., Richard F., et al. The obstetric care subsidy policy in Burkina Faso: what are the effects after five years of implementation? Findings of a complex evaluation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16:84. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0875-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tumwesigye B.T., Nakanjako D., Wanyenze R., Akol Z., Sewankambo N. Policy development, implementation and evaluation by the AIDS control program in Uganda: a review of the processes. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11(1):7. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ditlopo P., Blaauw D., Rispel L., Thomas S., Bidwell P. Policy implementation and financial incentives for nurses in South Africa: a case study on the occupation-specific dispensation. Glob Health Action. 2013;6(1) doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.19289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olivier de Sardan J.P., Ridde V. Public policies and health systems in Sahelian Africa: theoretical context and empirical specificity. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(Suppl. 3):S3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-15-S3-S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chuma J., Musimbi J., Okungu V., Goodman C., Molyneux C. Reducing user fees for primary health care in Kenya: policy on paper or policy in practice? Int J Equity Health. 2009;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Witter S., Khalid Mousa K., Abdel-Rahman M.E., Hussein Al-Amin R., Saed M. Removal of user fees for caesareans and under-fives in northern Sudan: a review of policy implementation and effectiveness. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013;28(1):e95–e120. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Naude C.E., Zani B., Ongolo-Zogo P., Wiysonge C.S., Dudley L., Kredo T., et al. Research evidence and policy: qualitative study in selected provinces in South Africa and Cameroon. Implement Sci. 2015;10:126. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0315-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.El-Jardali F., Lavis J.N., Ataya N., Jamal D. Use of health systems and policy research evidence in the health policymaking in eastern Mediterranean countries: views and practices of researchers. Implement Sci. 2012;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rispel L.C., de Sousa C.A., Molomo B.G. Can social inclusion policies reduce health inequalities in sub-Saharan Africa?--a rapid policy appraisal. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009;27(4):492–504. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i4.3392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Luhalima T.R., Netshandama V.O., Davhana-Maselesele M. An evaluation of the implementation of tuberculosis policies at a regional hospital in the Limpopo Province. Curationis. 2008;31(4):31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kamuzora P., Gilson L. Factors influencing implementation of the community health Fund in Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22(2):95–102. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Colvin C.J., Leon N., Wills C., van Niekerk M., Bissell K., Naidoo P. Global-to-local policy transfer in the introduction of new molecular tuberculosis diagnostics in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(11):1326–1338. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boateng D., Awunyor-Vitor D. Health insurance in Ghana: evaluation of policy holders' perceptions and factors influencing policy renewal in the Volta region. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:50. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eamer G.G., Randall G.E. Barriers to implementing WHO's exclusive breastfeeding policy for women living with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: an exploration of ideas, interests and institutions. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013;28(3):257–268. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Blas E., Ataguba J.E., Huda T.M., Bao G.K., Rasella D., Gerecke M.R. The feasibility of measuring and monitoring social determinants of health and the relevance for policy and programme – a qualitative assessment of four countries. Glob Health Action. 2016;9(1) doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.29002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rao K.D., Nagulapalli S., Arora R., Madhavi M., Andersson E., Ingabire M.G. An implementation research approach to evaluating health insurance programs: insights from India. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5(5):295–299. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bennett S., Corluka A., Doherty J., Tangcharoensathien V., Patcharanarumol W., Jesani A., et al. Influencing policy change: the experience of health think tanks in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(3):194–203. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nabyonga-Orem J., Ousman K., Estrelli Y., Rene A.K., Yakouba Z., Gebrikidane M., et al. Perspectives on health policy dialogue: definition, perceived importance and coordination. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(Suppl. 4):218. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1451-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nabyonga Orem J., Marchal B., Mafigiri D., Ssengooba F., Macq J., Da Silveira V.C., et al. Perspectives on the role of stakeholders in knowledge translation in health policy development in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:324. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Orem J.N., Mafigiri D.K., Marchal B., Ssengooba F., Macq J., Criel B. Research, evidence and policymaking: the perspectives of policy actors on improving uptake of evidence in health policy development and implementation in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:109. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Agyepong I.A., Nagai R.A. "we charge them; otherwise we cannot run the hospital" front line workers, clients and health financing policy implementation gaps in Ghana. Health Policy. 2011;99(3):226–233. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gomez P.P., Gutman J., Roman E., Dickerson A., Andre Z.H., Youll S., et al. Assessment of the consistency of national-level policies and guidelines for malaria in pregnancy in five African countries. Malar J. 2014;13:212. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wan X., Stillman F., Liu H., Spires M., Dai Z., Tamplin S., et al. Development of policy performance indicators to assess the implementation of protection from exposure to secondhand smoke in China. Tob Control. 2013;22(Suppl. 2):ii9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050890. [15] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Peterson P.J., bin Mokhtar M., Chang C., Krueger J. Indicators as a tool for the evaluation of effective national implementation of the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS) J Environ Manage. 2010;91(5):1202–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hargreaves J.R., Goodman C., Davey C., Willey B.A., Avan B.I., Schellenberg J.R. Measuring implementation strength: lessons from the evaluation of public health strategies in low- and middle-income settings. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(7):860–867. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dickson K.E., Tran N.T., Samuelson J.L., Njeuhmeli E., Cherutich P., Dick B., et al. Voluntary medical male circumcision: a framework analysis of policy and program implementation in eastern and southern Africa. PLoS Med. 2011;8(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Church K., Kiweewa F., Dasgupta A., Mwangome M., Mpandaguta E., Gomez-Olive F.X., et al. A comparative analysis of national HIV policies in six African countries with generalized epidemics. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(7):457–467. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.147215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Langlois E.V., Becerril Montekio V., Young T., Song K., Alcalde-Rabanal J., Tran N. Enhancing evidence informed policymaking in complex health systems: lessons from multi-site collaborative approaches. Health Res Policy Syst. 2016;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s12961-016-0089-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gelli A., Espejo F. School feeding, moving from practice to policy: reflections on building sustainable monitoring and evaluation systems. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16(6):995–999. doi: 10.1017/S1368980012003989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Armstrong C.E., Lange I.L., Magoma M., Ferla C., Filippi V., Ronsmans C. Strengths and weaknesses in the implementation of maternal and perinatal death reviews in Tanzania: perceptions, processes and practice. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(9):1087–1095. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Starkl M., Brunner N., Stenstrom T.A. Why do water and sanitation systems for the poor still fail? Policy analysis in economically advanced developing countries. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47(12):6102–6110. doi: 10.1021/es3048416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bowen S., Zwi A.B. Pathways to "evidence-informed" policy and practice: a framework for action. PLoS Med. 2005;2(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Beran D., Miranda J.J., Cardenas M.K., Bigdeli M. Health systems research for policy change: lessons from the implementation of rapid assessment protocols for diabetes in low- and middle-income settings. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:41. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Erasmus E., Gilson L. How to start thinking about investigating power in the organizational settings of policy implementation. Health Policy Plan. 2008;23(5):361–368. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Daniels K., Lewin S. Translating research into maternal health care policy: a qualitative case study of the use of evidence in policies for the treatment of eclampsia and pre-eclampsia in South Africa. Health Res Policy Syst. 2008;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Juma P.A., Mohamed S.F., Wisdom J., Kyobutungi C., Oti S. Analysis of non-communicable disease prevention policies in five Sub-Saharan African countries: study protocol. Arch Public Health. 2016;74:25. doi: 10.1186/s13690-016-0137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Djellouli N., Quevedo-Gomez M.C. Challenges to successful implementation of HIV and AIDS-related health policies in Cartagena, Colombia. Soc Sci Med. 2015;133:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Witter S., Boukhalfa C., Cresswell J.A., Daou Z., Filippi V., Ganaba R., et al. Cost and impact of policies to remove and reduce fees for obstetric care in Benin, Burkina Faso, Mali and Morocco. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):123. doi: 10.1186/s12939-016-0412-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cooper D., Mantell J.E., Moodley J., Mall S. The HIV epidemic and sexual and reproductive health policy integration: views of South African policymakers. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:217. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1577-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Idd A., Yohana O., Maluka S.O. Implementation of pro-poor exemption policy in Tanzania: policy versus reality. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2013;28(4):e298–e309. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shroff Z., Aulakh B., Gilson L., Agyepong I.A., El-Jardali F., Ghaffar A. Incorporating research evidence into decision-making processes: researcher and decision-maker perceptions from five low- and middle-income countries. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:70. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0059-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gilson L., McIntyre D. The interface between research and policy: experience from South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(5):748–759. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maluka S.O. Why are pro-poor exemption policies in Tanzania better implemented in some districts than in others? Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:80. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Scott V., Mathews V., Gilson L. Constraints to implementing an equity-promoting staff allocation policy: understanding mid-level managers' and nurses' perspectives affecting implementation in South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2012;27(2):138–146. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ucakacon P.S., Achan J., Kutyabami P., Odoi A.R., Kalyango N.J. Prescribing practices for malaria in a rural Ugandan hospital: evaluation of a new malaria treatment policy. Afr Health Sci. 2011;11(Suppl. 1):S53–S59. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v11i3.70071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Twum-Danso N.A., Dasoberi I.N., Amenga-Etego I.A., Adondiwo A., Kanyoke E., Boadu R.O., et al. Using quality improvement methods to test and scale up a new national policy on early post-natal care in Ghana. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(5):622–632. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Odoch W.D., Kabali K., Ankunda R., Zulu J.M., Tetui M. Introduction of male circumcision for HIV prevention in Uganda: analysis of the policy process. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:31. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kleintjes S., Lund C., Swartz L., Flisher A. The Mhapp Research Programme C. Mental health care user participation in mental health policy development and implementation in South Africa. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2010;22(6):568–577. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2010.536153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Erasmus E. The use of street-level bureaucracy theory in health policy analysis in low- and middle-income countries: a meta-ethnographic synthesis. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(Suppl. 3):iii70. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu112. [8] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lehmann U., Gilson L. Actor interfaces and practices of power in a community health worker programme: a south African study of unintended policy outcomes. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28(4):358–366. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Cheung K.K., Mirzaei M., Leeder S. Health policy analysis: a tool to evaluate in policy documents the alignment between policy statements and intended outcomes. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34(4):405–413. doi: 10.1071/AH09767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hill Z., Dumbaugh M., Benton L., Källander K., Strachan D., ten Asbroek A., et al. Supervising community health workers in low-income countries – a review of impact and implementation issues. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1) doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Shung-King M. From 'stepchild of primary healthcare' to priority programme: lessons for the implementation of the National Integrated School Health Policy in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2013;103(12):895–898. doi: 10.7196/samj.7550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Gilson L., Schneider H., Orgill M. Practice and power: a review and interpretive synthesis focused on the exercise of discretionary power in policy implementation by front-line providers and managers. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(Suppl. 3):iii51. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czu098. [69] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Aniteye P., Mayhew S.H. Shaping legal abortion provision in Ghana: using policy theory to understand provider-related obstacles to policy implementation. Health Res Policy Syst. 2013;11:23. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-11-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Waweru E., Goodman C., Kedenge S., Tsofa B., Molyneux S. Tracking implementation and (un)intended consequences: a process evaluation of an innovative peripheral health facility financing mechanism in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(2):137–147. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ngoasong M.Z. Transcalar networks for policy transfer and implementation: the case of global health policies for malaria and HIV/AIDS in Cameroon. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(1):63–72. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Daire J., Khalil D. Analysis of maternal and child health policies in Malawi: the methodological perspective. Malawi Med J. 2015;27(4):135–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Panisset U., Koehlmoos T.P., Alkhatib A.H., Pantoja T., Singh P., Kengey-Kayondo J., et al. Implementation research evidence uptake and use for policy-making. Health Res Policy Syst. 2012;10:20. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-10-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Thow A.M., Sanders D., Drury E., Puoane T., Chowdhury S.N., Tsolekile L., et al. Regional trade and the nutrition transition: opportunities to strengthen NCD prevention policy in the Southern African Development Community. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1) doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.28338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Onwujekwe O., Uguru N., Russo G., Etiaba E., Mbachu C., Mirzoev T., et al. Role and use of evidence in policymaking: an analysis of case studies from the health sector in Nigeria. Health Res Policy Syst. 2015;13:46. doi: 10.1186/s12961-015-0049-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]