Abstract

Antibiotic resistance has become a global health issue, negatively affecting the quality and safety of patient care, and increasing medical expenses, notably in Indonesia. Antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) aim to reduce resistance rates and their implementation in hospitals, has a high priority worldwide.

We aimed to monitor the progress in the organizational implementation of ASPs in Indonesian hospitals by an Antimicrobial Resistance Control Program (ARCP) team and to identify possible hurdles. We conducted a cross-sectional study with structured interviews based on a checklist designed to assess the achievement of structural indicators at the organizational level in four private and three public hospitals in four regions (Surabaya, Sidoarjo, Mojokerto, Bangil) in East Java, Indonesia.

The organizational structure of public hospitals scored better than that of private hospitals. Only three of the seven hospitals had an ARCP team. The most important deficiency of support appeared to be insufficient funding allocation for information technology development and lacking availability and/or adherence to antibiotic use guidelines. The studied hospitals are, in principle, prepared to adequately implement ASPs, but with various degrees of eagerness. The hospital managements have to construct a strategic plan and to set clear priorities to overcome the shortcomings.

Keywords: Antibiotic stewardship, Structural indicators, Needs assessment, Hospital, Indonesia

Highlights

-

•

This information is important to propose:

-

•

an effective intervention needed by the hospital in Indonesia

-

•

implementation of a safe and sustainable antibiotic stewardship program in Indonesia

Key messages

There is an obvious need for sufficient resources for information technology development, for dissemination of guidelines for antibiotic use, and for provision of information about the use of appropriate antibiotics to educate patients.

1. Introduction

Any use of antibiotics will contribute to antibiotic resistance, including the appropriate use of antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is caused by the mutation of pathogenic micro-organisms, following inappropriate and superfluous use of antibiotics [1,2]. An antibiotic resistance study by the Indonesia Agency for Health Research and Development, Indonesian Ministry of Health (Badan Litbang Kesehatan Indonesia 2013) reported during a seminar in 2014, revealed that in six public hospitals in Indonesia the prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase in isolates of E. coli was 45%, in isolates of K. pneumonia 42%, and in isolates of K. oxytoca 26% [3].

Antibiotic resistance is a serious worldwide health problem that jeopardizes the quality and safety of patient care and may substantially increase treatment costs. For these reasons the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) emphasize the necessity for every hospital worldwide to implement an antibiotic stewardship program in order to prevent the development of antibiotic resistance [1,3]. The implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs in Indonesia is achieved by the establishment of an Antimicrobial Resistance Control Program (ARCP) team in all hospitals as stipulated in the Ministry of Health Regulation of the Republic of Indonesia No. 8 Year 2015 [4]. The ARCP is a new important standard for hospital accreditation in this country (Standar Nasional Akreditasi Rumah Sakit, SNARS) published in 2017 [5,6]. Therefore, in 2018 an assessment of the ARCPs was conducted by a hospital accreditation committee in every hospital in Indonesia for the purpose of hospital accreditation [5]. The ongoing high rates of antibiotic resistance in Indonesia, however indicate that the implementation of ARPs in most hospitals has not adequately been achieved, possibly due to a lack of facilities, infrastructure and strategies such as audits and feedback [7].

Strategies and priorities to provide resources to overcome the problems with implementation of antibiotic stewardship are based on a hospital's individual policy. Several studies reported that the needed resources required not only include audits and feedback by antibiotic stewardship teams but also comprise the purchase of information technology and software as well as the set-up of a microbiology laboratory [8]. There is a study in a single large tertiary care teaching medical center, where a stewardship program was considered part of the infection control program and no additional resources were required [9].

1.1. The aim of the study

To make a complete ARCP needs assessment, we aimed to assess the fulfillment of four domains (organization structure, leader support, internal and external factors, and information availability) necessary for the organizational implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs in selected private and public hospitals in Indonesia.

2. Materials and methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study with structured interviews in which observations were made using a questionnaire (Appendix 1) designed to assess the achievement of structural indicators at the organizational level of hospitals. In Table 1 demographic details of the seven hospitals included in this study are listed. The hospitals were selected based on their nature (public versus private), variety in number of beds, different levels of care provided and location (East Java, Indonesia).

Table 1.

Hospital demography.

| Characteristics | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital classificationa | B | B | B | C | A | B | C |

| Levels of care | A tertiary hospital | A tertiary hospital | A tertiary hospital | A secondary hospital | A tertiary hospital | A tertiary hospital | A secondary hospital |

| Number of bed | 117 | 172 | 235 | 225 | 467 | 134 | 109 |

| Area geographical | Surabaya municipality | Mojokerto regency | Surabaya municipality | Sidoarjo regency | Sidoarjo regency | Surabaya municipality | Bangil district |

| Ownership | Private | Government (public) | Private | Private | Government (public) | Private | Government (public) |

According to Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia (MoH-RI). [Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan No. 56 tahun 2014: Klasifikasi dan perizinan rumah sakit]: MoH-RI; 2014.

Hospital classification in Indonesia is done according to the Ministry of Health regulations [10]. There are three levels of care in the Indonesian health system. The primary care is a health facility providing a patient's first access to the health care. If specialized care is needed, the patient can be referred promptly to secondary (a secondary hospital) or tertiary care (a tertiary hospital) [11,12]. The Indonesian health system has a mixture of public and private providers and financing [13,14].

The questionnaire was based on CDC Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs [15], Structural Indicators for Evaluating Antimicrobial Stewardship Programs in European Hospitals [16], the Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee (BAPCOC) (used in Belgium, Europe and America for auditing the quality of antibiotic stewardship programs) [17], and National Standards for Hospital Accreditation in Indonesia [5,6]. The respondent (one for each hospital) was the person in charge of the hospital management who was responsible for the medical service to the patients. The interviews were performed by the authors. To ensure validity of interview result per respondent, the interview results were compared to document observation results by the authors, including circular letters of director, operational standards manuals, antibiotic usage manuals, formularies, hospital antibiogram, and antibiotic resistance prevalence reports available in the hospital. We attributed score 2 (Table 2, Internal and External Factors of the Hospital) in case a document was available support the interview. The results were presented to and discussed with the hospital staff. What we found was fully acknowledged and already recognized by them.

Table 2.

The hospitals readiness in the implementation of antibiotic stewardship.

| No. | Components | Max score | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Organizational structure | |||||||||

| Availability of ARCP team | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Multidisciplinary communication | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 8 (57) | |

| Multidisciplinary in ARCP | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Doctor as ARCP leader | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Presence of clinical pharmacist | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 (71) | |

| Total | 10 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 10 | ||

| 2. | Leader support | |||||||||

| Formal statement of ARCP team establishment | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 (57) | |

| Fund allocation for ARCP | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Fund allocation for health personnel education | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 (57) | |

| Fund allocation for IT development | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (14) | |

| Provision of education | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 10 (71) | |

| Total | 10 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 8 | ||

| 3. | Internal and external factors of the hospital | |||||||||

| Availability of policy for the doctor to administer doses, amounts, and direction of antibiotic use in hospital | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 14 (100) | |

| Availability of antibiotic use guidelines (Pedoman Penggunaan Antibiotik, PPAB) | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 (29) | |

| Availability of operational standards for audit and feedback by pharmacy | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Policy of antibiotic use | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 (43) | |

| Access of guidelines/journal | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 8 (57) | |

| Total | 10 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 8 | ||

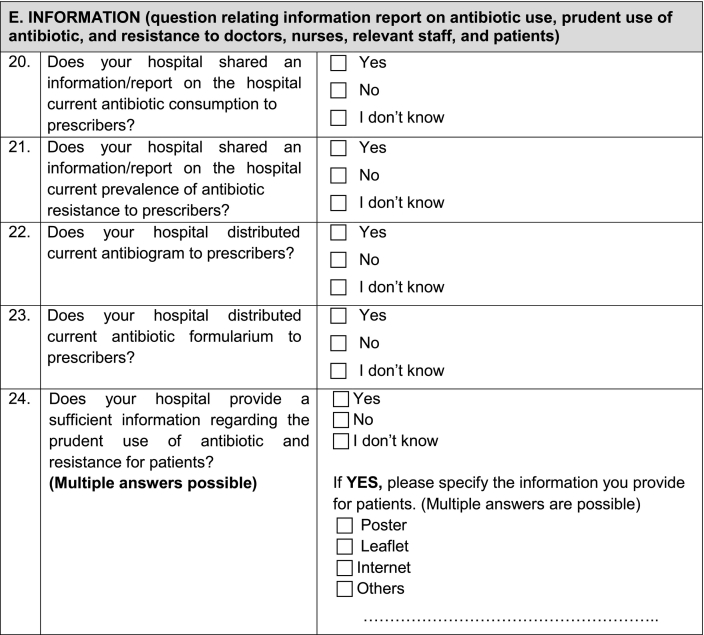

| 4. | Information availability | |||||||||

| Availability of data on the level of antibiotic use (DDD/100 bed-days) | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Socialization of the prevalence of resistant bacteria to prescriber | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Distribution of antibiograms throughout the wards | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 (71) | |

| Distribution of formularies to the entire wards | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Information on the wise use of antibiotics for patients | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 6 (43) | |

| Total | 10 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 10 | 10 | ||

| Total | 4 | 8 | 18 | 18 | 22 | 36 | 36 | |||

| Scale organization level: total/40 × 10 | 1 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 9 | 9 | |||

In the questionnaire four domains were distinguished: organizational structure, leader support, internal and external factors of the hospital, and information availability (Appendix 1), each with a number of questions (items), that were answered by the interviewed staff. These domains were based on the sources [5,6,15., 16., 17.] used to compile the questionnaire. In the analysis, the scores per item within a domain and overall were summed (Table 2). The total score per hospital was divided by the maximum score of 40 points and multiplied by 10. We subdivided a scale of 0–3 as “low” ARCP implementation; scale 4–6 as “intermediate” ARCP implementation; scale 7–10 as “high” ARCP implementation.

3. Results

Not all hospitals under study had an ARCP team. Only one hospital allocated funds for information technology (IT) development. All hospitals had a policy for the medical doctors with respect to antibiotic use. Nearly all hospitals had an antibiogram. The antibiotic stewardship implementation scores between hospitals varied, from low (hospitals A and B), to intermediate (hospitals C, D, and E), and high (hospitals F and G) (see Table 2). Of the three public (government financed) hospitals, two had an ARCP team installed. Two hospitals were in the readiness stage from an organizational perspective (score 9 out of 10), three hospitals were in the intermediate readiness stage (4.5/10, 4.5/10, 5.5/10 respectively), and two hospitals was in the early readiness stage (1/10, 2/10) of implementing the antibiotic stewardship program (see Table 2). The data from the seven participating private and public hospitals show that the stage of developing ARCP varied. One hospital (hospital A) was not ready to implement the antibiotic stewardship program; it merely had a policy for the doctors to prescribed antibiotic and the antibiogram.

Among the four domains, from lowest score to the highest score, leader support and information availability had the lowest average score (6.8), the subsequent domains were organization structure (7.2), internal and external factors (7.6).

Descriptive analysis of all potential barriers revealed that in all participating hospitals fund allocation for IT development and availability of guidelines for antibiotic use were not well developed or even absent.

Organizational aspects that were well developed in all hospitals included the presence of a hospital pharmacist as part of the ARCP team, the provision of educational information from the management, the availability of information for doctors on the appropriate type and dosing and administration of antibiotics, and the distribution of antibiogram throughout the wards.

4. Discussion

Similar to other developing countries, addressing antibiotic resistance in Indonesia requires a systems perspective. For the successful implementation of a sustainable and comprehensive antibiotic stewardship program in hospitals, leadership, commitment, and sufficient funding are needed [18., 19., 20., 21.]. The results of the Organization Structure domain show that less than 50% of the hospitals have an ARCP team. ARCP serves to control the use of antibiotics to reduce the incidence of antibiotic resistance.

The relevance of an ARCP is supported by a systematic review of 32 studies by Baur et al. showing that the implementation of antibiotic stewardship programs for at home illness in 19 countries could significantly reduce 51% of incidence of infection, 48% of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Gram-negative bacteria, 37% of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and 32% the incidence of Clostridium difficile infections [22]. Based on this research evidence it was recommended that every hospital should immediately start the implementation of formation of an ARCP. Not only the availability of ARCP team but also multidisciplinary communication among professionals is a critical point to the success of the ASP implementation [23].

From the scores of the Leader Support domain, it appears that less than 50% of the hospitals had fund allocation for ARCP and that only 14% of the hospitals had fund allocation for IT development. In 1999 The Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee (BAPCOC) created a situation in which all acute care hospitals in the country received financial and technical support for hiring a trained manager for their antimicrobial management teams. This intervention, the antimicrobial management teams and the antimicrobial management teams funding, improved the antimicrobial use for patients admitted to hospital for pneumonia and lower limb surgery between 1999 and 2010 in Belgium [24]. Based on this information, fund allocation is strongly recommended for needed supports for the ARCP in each hospital.

The study by Van Limburg et al. aimed at analyzing progress and obstacles in the implementation of the antibiotic stewardship program at nine hospitals in the Netherlands (three educational and six non-educational hospitals) [25]. It was shown that only 25% of educational hospitals and 18% non-educational hospitals had implemented IT for antibiotic stewardship programs. According to the CDC, the role of IT in the integration of antibiotic stewardship with the services provided at a hospital is imperative. This role includes giving support for decisions regarding antibiotic prescriptions, providing facilities for the collection and reporting of antibiotic use, as well as providing information and protocols that can be directly linked to ARCP or clinical pathways owned by the hospital, thereby potentially improving the rational use of medicines [9]. This finding is supported by the study by Charani et al. showing that there was an insignificant increase in the adherence to the use of antibiotics on empirical therapy in the treatment of hospitalized patients [26]. The increase was significant, however, in the operating theater. In addition, there was an increased (but insignificant) percentage in documenting a stop/review date regarding the prescription of hospitalized patients. Based on this research evidence, it is necessary to allocate funds for IT development in order to realize the optimum goals of an effective ARCP at each hospital.

Research on the internal and external factors of the hospital showed that the availability of guidelines for antibiotic use was in the low category, because not all hospitals have guidelines for antibiotic use. The study by Van Limburg et al. showed that 88% of educational hospitals and 73% of non-educational hospitals implement antibiotic formulary for antibiotic stewardship program [25]. Guidelines for Antibiotic Use is a guideline according to the types of infections in patients or as prophylaxis for surgery [27,28]; therefore an ARCP can assist in the selection of antibiotics. According to the IDSA's guideline, the development of Guidelines for Antibiotic Use from recent literature and antibiotic resistance reports is an additional component for implementing antibiotic stewardship. This is supported by a study reporting that the use of Guidelines for Antibiotic Use in intensive care unit (ICU) could reduce approximately 77% of antibiotic use and treatment costs, decrease patient mortality resulting from infections and decrease the length of stay in ICU compared to before using an ARCP as a guide for choosing antibiotic therapy [29]. Based on this information, it is recommended that each hospital immediately starts to prepare guidelines for antibiotic use to be used in the rational and responsible selection of antibiotic therapy.

The results of the research on the information availability domain showed that only 43% hospitals provide information to the patient to use antibiotics wisely. Hospitals provide information on the rational use of antibiotics through leaflets, posters and light-emitting diode (LED) banner displays for both outpatients and inpatients, as there are several out-of-hospital patients who still continue to consume antibiotics in accordance with the duration of administration. Research conducted by Eells et al. in 188 patients with skin infections aimed to determine the adherence to the use of antibiotics during out-of-hospital care [30]. This study showed that patients had poor adherence to antibiotic use after checking out of hospital with worsening clinical outcomes.

Based on Rosenstock's Health Belief Model (HBM) theory, there are several construct determinants for the likelihood behavior (i.e. individual perception), some modifying factors (age, sex, ethnicity, personality, socioeconomic, knowledge), and cues to action. Knowledge is a modifiable factor and the perception of the provision of information to patients is useful for improving their knowledge [31]. Knowledge is one of the factors that influence our beliefs, which in turn affects behavior such as an increase in the adherence to the use of antibiotics as a means to improve the success of therapy and prevent antibiotic resistance. This is in line with a study conducted by Munoz et al. [32], where 126 patients were divided into two groups: 62 patients in the intervention group and 64 patients in the control group. The results showed that there was a significant difference in the level of conformity between the intervention group that was educated and the control group. Based on this information, it is recommended that each hospital provides reliable information regarding the use of antibiotics to patients through leaflets, posters and LED banner displays as an appropriate form of action and a means to increase the rational use of antibiotic.

5. Conclusions

The studied hospitals are, in principle, ready to implement adequate ASPs, but with various degrees of readiness. The main barriers are a lack of fund allocation for IT development (6/7) and unavailability of guidelines for antibiotic use (5/7). Every hospital should immediately start to implement an ARCP according to Indonesian national standards.

Abbreviations

- ARCP

Antimicrobial Resistance Control Program

- ASPs

Antibiotic stewardship programs

- BAPCOC

The Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee

- CDC

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- HBM

Health Belief Model

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- IT

Information technology

- LED

Light-emitting diode

- Menristekdikti

Menteri Riset, Teknologi dan Pendidikan Tinggi (Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia)

- SNARS

Standar Nasional Akreditasi Rumah Sakit (National Standards for Hospital Accreditation)

- WHO

The World Health Organization

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted in the framework of a collaboration agreement between the Faculty of Pharmacy University of Surabaya, Jalan Raya Kalirungkut, Surabaya and the Groningen Research Institute of Pharmacy, Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Groningen, The Netherlands. We would like to thank to Erik Christopher, Klinik Bahasa, Faculty Kedokteran, Universitas Gadjah Mada (Yogyakarta) for helping to edit the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

FA was conceptualization and made the original draft the manuscript. The interviews were performed and the interview results were compared to document observation results by the authors SC, IA, SS, NL, NA, VA. HJW was writing, reviewing and editing. S, RY, EH, CA were reviewing and editing.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The written consent to participate were obtain from study participant. The study was approved by the respective hospital managements and was conducted in accordance with the Indonesian Law for the Protection of Personal Data. The study was ethically cleared by the Health Research Ethics Committee of Politeknik Kesehatan Kemenkes Surabaya, Kementerian Kesehatan No. 025/S/KEPK/V/2017.

Consent for publication

Interview participants received a participant information sheet and gave written consent.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Contributor Information

Fauna Herawati, Email: fauna@staff.ubaya.ac.id.

Setiasih, Email: setiasih@staff.ubaya.ac.id.

Rika Yulia, Email: rika_y@staff.ubaya.ac.id.

Eelko Hak, Email: e.hak@rug.nl.

Herman J. Woerdenbag, Email: h.j.woerdenbag@rug.nl.

Christina Avanti, Email: c_avanti@staff.ubaya.ac.id.

Appendix 1. Questionnaire

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC; Atlanta: 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2013.https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/pdf/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin J., Nishino K., Roberts M.C., Tolmasky M., Aminov R.I., Zhang L. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Front Microbiol. 2015;6(34) doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siswanto [Seminar Nasional] Jakarta: Center for Indonesian Veterinary Analytical Studies (CIVAS); 2014. Kajian Resistensi Antimikroba dan Situasinya pada Manusia di Indonesia. http://civas.net/cms/assets/uploads/2014/03/Kajian-Resistensi-Antimikrobial-dan-Situasinya-pada-Manusia-di-Indonesia.pdf

- 4.Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia (MoH-RI) MoH-RI; 2014. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan No. 8 tahun 2015: Program pengendalian resistensi antimikroba di rumah sakit. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia (MoH-RI) MoH-RI; 2017. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan Republik Indonesia No. 34 tahun 2017: Akreditasi rumah sakit. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Indonesian Commission for Hospital Accreditation (ICHA) Komisi Akreditasi Rumah Sakit (KARS); 2017. Standar Nasional Akreditasi Rumah Sakit Edisi 1. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parathon H., Kuntaman K., Widiastoety T.H., Muliawan B.T., Karuniawati A., Qibtiyah M., Djanun Z., Tawilah J.F., Aditama T., Thamlikitkul V., Vong S. Progress towards antimicrobial resistance containment and control in Indonesia. BMJ. 2017;358:j3808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wagner B., Filice G.A., Drekonja D., Greer N., MacDonald R., Rutks I., Butler M., Wilt T.J. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in inpatient hospital settings: a systematic review. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(10):1209–1228. doi: 10.1086/678057. [Epub 2014 Aug 21] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenehjem E., Hyun D.Y., Septimus E., Yu K.C., Meyer M., Raj D., Srinivasan A. Antibiotic stewardship in small hospitals: barriers and potential solutions. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(4):691–696. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia (MoH-RI) MoH-RI; 2014. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan No. 56 tahun 2014: Klasifikasi dan perizinan rumah sakit. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health Republic of Indonesia (MoH-RI) MoH-RI; 2013. Peraturan Menteri Kesehatan No. 71 tahun 2013: Pelayanan kesehatan pada jaminan kesehatan nasional. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hensher M., Price M., Adomakoh S. In: Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed. Jamison D.T., Breman J.G., Measham A.R., Alleyne G., Claeson M., Evans D.B., Jha P., Mills A., Musgrove P., editors. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. Referral hospitals. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heywood P., Harahap N.P. Health facilities at the district level in Indonesia. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 2009;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahendradhata Y., Trisnantoro L., Listyadewi S., Soewondo P., Marthias T., Harimurti P., Prawira J. The Republic of Indonesia health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2017;7(1):1–292. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254716/9789290225164-eng.pdf;jsessionid=C14704A620474D133474DEFDDD9E5003?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; Atlanta, GA: 2014. Core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs.http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/implementation/core-elements.html [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buyle F.M., Metz-Gercek S., Mechtler R., Kern W.V., Robays H., Vogelaers D., Struelens M.J. Development and validation of potential structure indicators for evaluating antimicrobial stewardship programmes in European hospitals. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32(9):1161–1170. doi: 10.1007/s10096-013-1862-4. [Epub 2013 Mar 23] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balligand E., Costers M., Van Gastel E. Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee (BAPCOC); 2014. Belgian Antibiotic Policy Coordination Committee: policy paper for the 2014 – 2019 term. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrett G.L., Bloom G., Wilkinson A., MacGregor H. Towards the just and sustainable use of antibiotics. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2016;9:31. doi: 10.1186/s40545-016-0083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James R.S., McIntosh K.A., Luu S.B., Cotta M.O., Marshall C., Thursky K.A., Buising K.L. Antimicrobial stewardship in Victorian hospitals: a statewide survey to identify current gaps. Med J Aust. 2013;199(10):692–695. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cairns K.A., Roberts J.A., Cotta M.O., Cheng A.C. Antimicrobial stewardship in Australian hospitals and other settings. Infect Dis Ther. 2015;4(Suppl. 1):27–38. doi: 10.1007/s40121-015-0083-9. [Epub 2015 Sep 11] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung V., Wu J.H., Langford B.J., Garber G. Landscape of antimicrobial stewardship programs in Ontario: a survey of hospitals. CMAJ Open. 2018;6(1):E71–E76. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20170111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baur D., Gladstone B.P., Burkert F., Carrara E., Foschi F., Döbele S., et al. Effect of antibiotic stewardship on the incidence of infection and colonisation with antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(9):990–1001. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30325-0. [Epub 2017 Jun 16] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Setiadi A., Wibowo Y., Herawati F., Irawati S., Setiawan E., Presley B., Zaidi M.A., Sunderland B. Factors contributing to interprofessional collaboration in Indonesian health centres: a focus group study. J Interprofessional Educ Pract. 2017;8:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.xjep.2017.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert M.L., Bruyndonckx R., Goossens H., Hens N., Aerts M., Catry B., Neely F., Vogelaers D., Hammamiet N. The Belgian policy of funding antimicrobial stewardship in hospitals and trends of selected quality indicators for antimicrobial use, 1999–2010: a longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van Limburg M., Sinha B., Lo-Ten-Foe J.R., van Gemert-Pijnen J.E. Evaluation of early implementations of antibiotic stewardship program initiatives in nine Dutch hospitals. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2014;3(33) doi: 10.1186/2047-2994-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charani E., Gharbi M., Moore L.S.P., Castro-Sanchéz E., Lawson W., Gilchrist M., Holmes A.H. Effect of adding a mobile health intervention to a multimodal antimicrobial stewardship programme across three teaching hospitals: an interrupted time series study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72(6):1825–1831. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herawati F., Yulia R., Hak E., Hartono A.H., Michiels T., Woerdenbag H.J., et al. A retrospective surveillance of the antibiotics prophylactic use of surgical procedures in private hospitals in Indonesia. Hosp Pharm. 2019;54(5):323–329. doi: 10.1177/0018578718792804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yulia R., Giovanny B.E., Khansa A.A., Utami S.P., Alkindi F.F., Herawati F., Jaelani A.K. The third-generation cephalosporin use in a regional general hospital in Indonesia. Int Res J Pharm. 2018;9(9):41–45. doi: 10.7897/2230-8407.099185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dellit T.H., Owens R.C., McGowan J.E., Jr., Gerding D.N., Weinstein R.A., Burke J.P., Huskins W.C., Paterson D.L., Fishman N.O., Carpenter C.F., Brennan P.J., Billeter M., Hooton T.M. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program to enhance antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(2):159–177. doi: 10.1086/510393. Epub 2006 Dec 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eells S.J., Nguyen M., Jung J., Macias-Gil R., May L., Miller L.G. Relationship between adherence to oral antibiotics and postdischarge clinical outcomes among patients hospitalized with Staphylococcus aureus skin infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:2941–2948. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02626-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glanz K., Rimer B.K., Viswanath K. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2008. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muñoz E.B., Dorado M.F., Guerrero J.E., Martínez F.M. The effect of an educational intervention to improve patient antibiotic adherence during dispensing in a community pharmacy. Aten Primaria. 2014;46(7):367–375. doi: 10.1016/j.aprim.2013.12.003. [Epub 2014 Feb 26] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.