Abstract

Fabry disease is an X-linked progressive lysosomal disorder, due to α-galactosidase A deficiency. Patients with a classic phenotype usually present in childhood as a multisystemic disease. Patients presenting with the later onset subtypes have cardiac, renal and neurological involvements in adulthood. Unfortunately, the diagnosis is often delayed until the organ damage is already irreversibly severe, making specific treatments less efficacious. For this reason, in the last two decades, newborn screening has been implemented to allow early diagnosis and treatment. This became possible with the application of the standard enzymology fluorometric method to dried blood spots. Then, high-throughput multiplexable assays, such as digital microfluidics and tandem mass spectrometry, were developed. Recently DNA-based methods have been applied to newborn screening in some countries. Using these methods, several newborn screening pilot studies and programs have been implemented worldwide. However, several concerns persist, and newborn screening for Fabry disease is still not universally accepted. In particular, enzyme-based methods miss a relevant number of affected females. Moreover, ethical issues are due to the large number of infants with later onset forms or variants of uncertain significance. Long term follow-up of individuals detected by newborn screening will improve our knowledge about the natural history of the disease, the phenotype prediction and the patients’ management, allowing a better evaluation of risks and benefits of the newborn screening for Fabry disease.

Keywords: Fabry disease, newborn screening, lysosomal storage disease, digital microfluidics, tandem mass spectrometry, second tier test, LysoGb3

1. Introduction

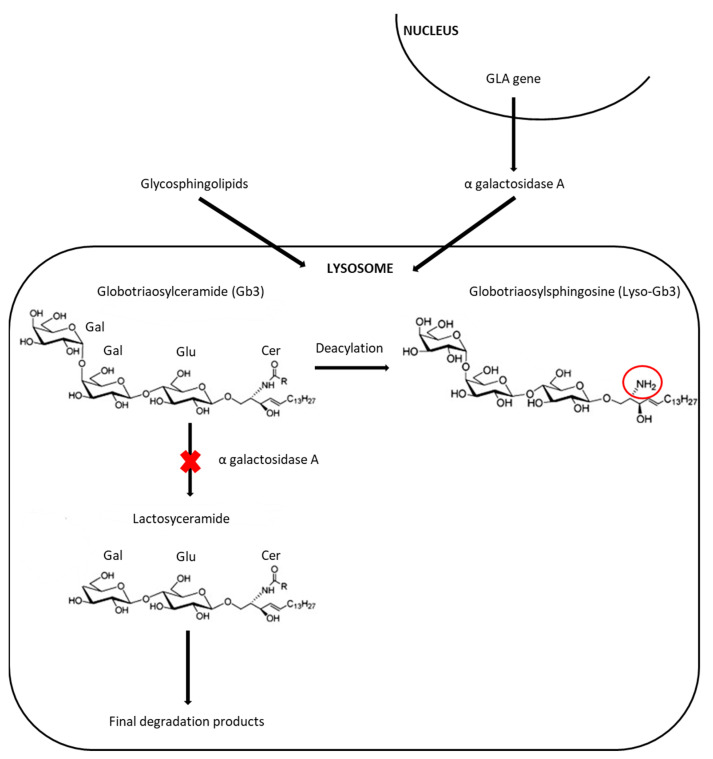

Fabry disease (FD, OMIM 301500) is an X-linked lysosomal disorder, caused by α-galactosidase A (α-GalA) deficiency, encoded by GLA gene, that leads to progressive accumulation of globotriaosylceramide (Gb3) and related glycosphingolipids (Figure 1) [1,2].

Figure 1.

Metabolic pathway involved in FD. αGalA deficiency, due to the GLA gene pathogenic variant, leads to lysosomal storage of globotriaosylcramide (Gb3) and related glycosphingolipids (for example, its deacylated form, globotriaosylsphingosine or lysoGb3).

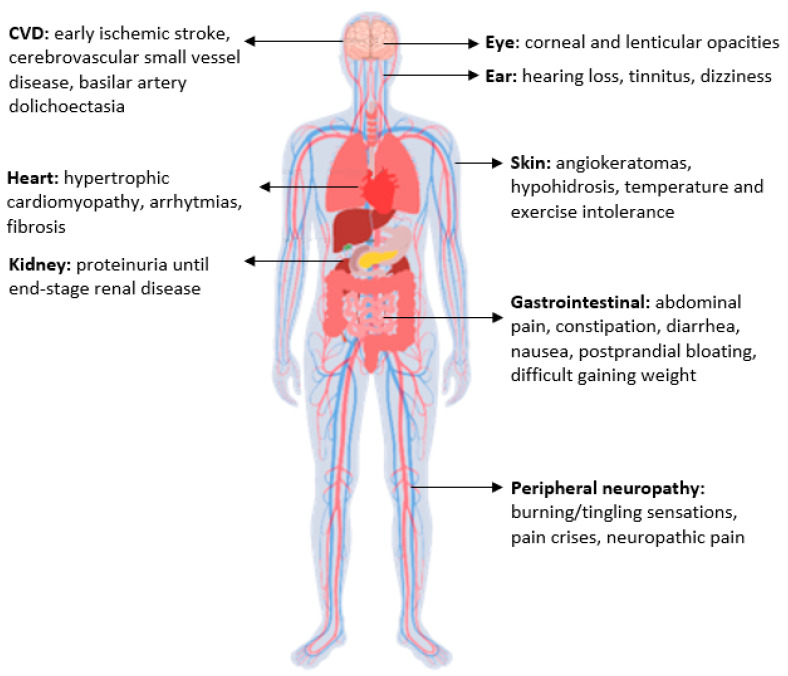

The clinical spectrum of FD is wide (Figure 2). Patients with a classic phenotype present with angiokeratomas, neuropathic pain, hypohidrosis, hearing loss and gastrointestinal symptoms. These symptoms can occur in early childhood before age 5 years, especially neuropathic pain and gastrointestinal symptoms [3]. In adulthood, the patients can show severe involvement of kidney, heart, central nervous (mainly cerebrovascular disease) and peripheral nervous system. Patients presenting with the later onset subtypes have cardiac, renal and neurological involvements, with a different degree of clinical severity, in adulthood [4,5]. The clinical manifestations in female heterozygotes also depend on the X-chromosome random inactivation that increases the phenotypic variability [6]. Unlike other X-linked disorders, females with Fabry disease often show clinical manifestations. One possible explanation, besides X-inactivation and skew deviation, is the ineffective cross-correction of the enzyme activity in vivo. Unaffected fibroblasts from Fabry heterozygotes mostly secrete the mature form of the enzyme, which lacks the high-uptake mannose-6-phosphate residues. This form cannot be efficiently endocytosed by the affected cells. Therefore, a less active enzyme can complement the activity of the cells lacking expression of the enzyme [7].

Figure 2.

Principal signs and symptoms of FD. CVD: cerebrovascular disease.

The diagnosis can be confirmed by the enzyme activity measurement in dried blood spot (DBS), leukocytes, plasma or fibroblasts in FD males, identification of glycosphingolipid accumulation (Gb3 and especially its deacylated form lysoGb3 in plasma, urine, tissues) and genetic analysis [8,9]. Several therapies are available: enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with recombinant human-galactosidase A (alfa 0.2 mg/kg or beta 1 mg/kg), to be given intravenously biweekly [10,11], and oral pharmacologic chaperon (migalastat) in patients with amenable pathogenic variants [12].

FD is a pan-ethnic disease, but a particularly high incidence of the later onset form is reported in Taiwan, due to the high prevalence of the pathogenic variant c.640−801G>A (IVS4+919G>A) [13].

The therapy should be initiated as soon as possible on presentation of early signs [14,15]. However, diagnostic delay is common, due to the heterogeneous and non-specific symptoms that frequently arise when organ damage is already irreversibly severe [16,17,18]. In the absence of a detailed family history or in case of de novo variants, presymptomatic detection of FD can be achieved only through a newborn screening (NBS) program.

Here, we summarize the current state of newborn screening for FD, including our long-term experience. Finally, we give an overview of programs with some level of implementation worldwide, discuss these data and highlight advantages and limitations.

2. Methods

We searched PubMed and EMBASE until 28 February 2023, using the search terms “Fabry disease” and “newborn screening” or “Fabry disease” and “second tier test” or “newborn screening” and “lysoGb3”. The search was extended with synonyms for FD and matching terms or headings. We selected full-text articles in peer reviewed journals in the English language. References were cross-checked for additional relevant papers.

3. Results

3.1. Screening Methods

From a technology perspective, high-throughput newborn screening for FD may be feasible using various analytical approaches (Table 1). Among these, the most frequently used are digital microfluidics (DMF) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), because they are multiplexable with commercially available reagents.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the available screening methods for FD newborn screening.

| Characteristics | Fluorometry | Digital Microfluidics | Tandem Mass Spectrometry | Immune Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | enzymatic assay | enzymatic assay | enzymatic assay | protein abundance |

| Multiplexable | no | yes | yes | yes |

| Incubation time | overnight | 3 h | overnight | overnight |

| Assay conditions (specific pH, additives, buffers) | optimal | optimal | fixed pH (4.7) | not applicable |

| Interferences | low | low | very low | non-functioning enzyme |

| Analytical range | good | good | very good | not applicable |

| Instrumentation costs | low | low | high | low |

| Assay costs | low | intermediate | intermediate | low |

| Reagents | commercially available | commercially available | commercially available | not commercially available |

| Laboratory training | simple | simple | intermediate | Intermediate |

| Automation | Intermediate | high | high | Intermediate |

| Sample throughput | low | intermediate | high | low |

Immune quantification applies microbead array technology with detection of fluorescence to determine the amount of each protein. It requires protein-specific antibodies that are currently not commercially available. Moreover, the method is not useful in cases where a non-functional protein is produced [19,20].

Fluorometric enzymatic assay uses a fluorogenic substrate (4-methylumbelliferyl-D-galactopyranoside). After overnight incubation, the fluorescence of the enzyme product 4-MU (4-methylumelliferone) is measured [21,22,23].

DMF enzymatic assay is a multiplex approach, also based on fluorometric enzyme activity assays. Digital microfluidics involves the transport of sub-microliter volumes of both sample and enzyme assay components over an array of electrodes under the influence of an electric field, by a process known as electrowetting [24,25,26]. The “spatial multiplexing” DMF method permits each LSD enzyme reactions to be performed in an individual droplet under its individually optimized conditions [27]. It is the fastest currently available method, enabling same-day result reporting [28].

MS/MS enzymatic assay uses an assay mixture containing the substrate and internal standard. After overnight incubation, and remotion of detergents, salts and excess substrate, the samples are introduced to a tandem mass spectrometer. The enzymatic reaction product is quantified by determination of the ion abundance ratio of product to internal standard for each sample. Since all products and internal standards have different masses, several enzymes could be analyzed together by MS/MS [29,30,31,32,33].

Comparison between MS/MS and fluorometric method: DMF and MS/MS allow for the determination of multiple enzyme activities on a 3 mm disc-punch. Both use reagent kits supplied by commercial vendors (Babies Inc and Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, respectively) that are inexpensive and readily available, but MS/MS, in contrast to DMF, can be modified by any laboratory to include more enzyme assays or other markers in a single assay [34]. MS/MS assay needs overnight incubation and is performed in a 96-well format. DMF analyzes 40 samples within 4 h in 48-well cartridges. In an MS/MS assay, the pH is not optimized. For more enzymes that necessitate of different buffers, multiple incubations can be combined prior to a single injection into the mass spectrometer instrument [35], whereas with DMF, additional microfluidics cartridges and readers are required [32].

There are numerous reports claiming superior performance for MS/MS relative to fluorometry and DMF for LSD screening [31,36,37,38].

The superior analytical range of MS/MS compared to fluorometric assays has been described by several groups [31,36,39,40], providing a more accurate value of enzymatic activity, especially for very low values. This in turn predicts a lower number of screen positives. These data have been confirmed by retrospective comparative studies in Taiwan [41] and USA [36]. An additional advantage of MS/MS is that the substrates are closer in structure to the natural enzyme substrates, because incorporation of a fluorogenic group into the molecule is not required [36]. Comparison of false positive rates is complicated by the fact that the values depend on the chosen cutoffs and by the uncertainty in establishing a positive sample based on gene sequencing (given the large numbers of variant of uncertain significance VUS). Probably the most important metric is the measured ratio of mean enzymatic activity of random newborns to that of affected samples. This ratio for MS/MS is 5- to 23-fold higher than that for DMFs, and it is expected to lead to a lower false positive rate [31]. Precision studies carried out by the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA) in an identical setting and with identical samples show that MS/MS provides improved assay precision over DMF [32]. However, a prospective comparative effectiveness study on 89,508 deidentified residual newborn DBS performed in California demonstrated that MS/MS, DMF and immunocapture showed high sensitivity, but lack in specificity, with need for improvement [34].

3.2. Second Tier Test

Specificity of the screening test can be improved with second tier biochemical or molecular testing. This latter is questionable because of the disclosure of genotypes associated with VUS and unclassified variants. Additionally, most NBS laboratories do not have the expertise to provide such second-tier testing [28].

As a biomarker, lysoGb3 can be measured in DBS by liquid chromatography-MS/MS technology [42,43,44]. In patients with FD, the concentration of lysoGb3 has been shown to have diagnostic value, and it correlates with phenotype and severity of manifestations (high levels in patients with classic phenotype, especially male, mild-to-moderately elevated levels in individuals with later onset phenotype) and females [42,43]. Moreover, it is a non-invasive marker for monitoring the disease during follow-up and treatment [42]. There are a few reports in which lysoGb3 has been evaluated in the neonatal period [33,42,45,46,47]. Increased values are very suggestive of FD [46,47], but normal lysoGb3 cannot exclude the possibility of later onset FD. In follow-ups of positive newborns with predicted later onset forms, the levels of lysoGb3 gradually increase with age, which might suggest a progressive and insidious accumulation. Thus, it may allow non-invasive investigation of patients in the presymptomatic period [45], despite it being yet unclear whether there is a critical threshold that justifies initiation of therapy [48].

3.3. Genetic Screening

Two molecular high-throughput methods, high-resolution melting analysis and Sequenom iPlex (Agena iPlex), have been investigated (Table 2).

Table 2.

Molecular assays for FD newborn screening.

| Molecular Assay | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| High resolution melting | Cover the 7 exons and the IVS4 variant | Low sensitivity for variants located at exons 2 and 6 Sensitivity to variable concentrations of nucleic acid or salts Need of experience for periodic parameters adjustment Not reliable for males |

| Agena iPlex | Not stringent DNA quality control Easy, simple training Less than one day |

Only known pathogenic variants |

High resolution melting (HRM) analysis: Primer sets were designed to cover the seven exons and the Asian common intronic pathogenic variant, IVS4+919G>A, of the GLA gene. The assay starts with PCR amplification in the presence of an appropriate DNA binding dye, followed by the formation of heteroduplex molecules and a final melting and analysis step. Variants are identified through a change in melting curve position, shape or deviated melting curve shape. Possible concerns may be the low sensitivity to identify all Fabry variants, especially those located at exons 2 and 6 because their amplicons are greater than 300 bp. The sensitivity to variable concentrations of nucleic acids or salts necessitates experience in analyzing the study results, because many parameters need periodic adjustment. Finally, HRM is not reliable for detecting male individuals, as the assay procedure depends on the formation of the heteroduplex [49].

Agena iPlex: It is a MassARRAY® genotyping platform that analyzes nucleotide variations by mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF), using a distinguishing allele-specific primer to amplify the extension products. Advantages of the Agena iPLEX assay are that stringent DNA quality control of the samples is not required, the procedure is relatively easy to perform in less than one day and the results can be interpreted by simply trained physicians and medical technologists. The limitation is that it only can detect known variants that have been designed into the assay panel. It is suitable when hotspot variants and common variations are known in a well-studied population. For example, in Taiwan, ~98% of Fabry patients carry variants out of a pool of only 21 pathogenic variants. An Agena iPLEX platform was designed to detect these 21 pathogenic variants and is being used [50,51].

3.4. Newborn Screening for FD in the World

Several NBS pilot studies and programs for FD have been implemented worldwide in recent years. However, state-based NBS programs still vary across countries, based on the economic cost of screening, local expertise and interest, political decisions and patient/family advocacy. A summary of available data on the reported NBS programs for FD is present in Table 3.

Table 3.

The most important FD pilot studies and screening programs worldwide.

| Study Period | Country | Method | Type of Cutoff | Number of NBS Samples | Number of below Cutoff Samples | Number of below Cutoff Samples/100,000 Newborns | Confirmed Patients from Genetic Analysis * | Presumed Incidence ** | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | |||||||||

| 2003–2005 | Italy | Fluorometric enzyme assay | fixed | 37,104 (only males) | 12 (m) | 32 (m) | 12 (m) | 1:3100 (m) | Spada et al. [22] |

| 2008 | Spain | Fluorometric enzyme assay | fixed | 14,600 (m 7575) | 106 (m 68) | 726 (m 898) | 37 (m 20) | 1:394 (m 1:378) | Colon et al. [52] |

| 2010–2012 | Italy | Fluorometric enzyme assay | fixed | 3403 (m 1702) | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | Paciotti et al. [53] |

| 2010 ** | Austria | MS/MS | fixed | 34,736 (deidentified) | 28 | 81 | 9 (m 6) | 1:3860 | Mechtler et al. [54] |

| 2011 *** | Hungary | MS/MS | fixed | 40,024 (deidentified) | 34 | 85 | 3 | 1:13,341 | Wittmann et al. [55] |

| 2015–2021 | Italy | MS/MS | fixed | 173,342 (m 89,485) | 23 (m 22) | 13 (m 25) | 22 (m) | 1:7879 (m 1:4068) | Gragnaniello et al. [45] |

| Asia | |||||||||

| 2006–2008 | Taiwan | Fluorometric enzyme assay | fixed | 171,977 (m 90,288) | 94 (m 91) | 55 (m 53) | 75 (m 73) | 1:2293 (m 1:1237) | Hwu et al. [23] |

| 2006–2018 | Japan | Fluorometric enzyme assay | fixed | 599,711 | 138 | 23 | 108 (m 64) | 1:5552 | Sawada et al. [56] |

| 2007–2010 | Japan | Fluorometric enzyme assay | fixed | 21,170 (m 10,827) | 7 (m 5) | 33 (m 46) | 6 (5 m) | 1:3024 (m 1:2166) | Inoue et al. [57] |

| 2007–2014 | Japan | Fluorometric enzyme assay | fixed | 2443 | 2 (m 2) | 82 | 2 (m 2) | 1:1222 | Chinen et al. [58] |

| 2008–2014 | Taiwan | Fluorometric enzyme assay then MS/MS | fixed | 792,247 (m 412,299) | 764 (m 425) | 96 (m 103) | 324 (m 272) | 1:2445 (m 1:1515) | Liao et al. [59] |

| 2010–2013 | Taiwan | MS/MS (compared with fluorometry) | fixed | 191,767 | 79 | 41 | 64 (m 61) | 1:2996 | Liao et al. [41] |

| 2015–2019 | Taiwan | MS/MS | fixed | 137,891 | 13 | 19 | 13 | 1:10,607 | Chiang et al. [60], Chien et al. [46] |

| 2019–2022 | China | MS/MS | %DMA | 38,945 | 21 | 54 | 3 | 1:12,982 | Li et al. [61] |

| USA | |||||||||

| 2011–2013 *** | California | MS/MS, immunocapture assay, DMF (comparative) | 89,508 (m 44,664) (deidentified) | Variable based on method | Not applicable | 50 (m 46) | 1:1790 (m 1:1970) | Sanders et al. [34] | |

| 2013 ** | Washington State | MS/MS | %DMA | 108,905 (m 54,800) (deidentified) | 16 (m 13) | 15 (m 24) | 7 (m 7) | 1:15,558 (m 1:7800) | Scott et al. [62] |

| 2013 | Missouri | DMF | fixed | 43,701 | 28 | 64 | 15 (m 15) | 1:2913 | Hopkins et al. [14] |

| 2013–2019 | New York | MS/MS | % DMA | 65,605 | 31 | 47 | 7 (m 7) | 1:9372 | Wasserstein et al. [63] |

| 2014–2016 | Illinois | MS/MS | % DMA | 219,793 | 107 | 49 | 32 (m 32) | 1:6968 | Burton et al. [64] |

| 2016 *** | Washington State | MS/MS | % DMA | 43,000 (deidentified) | 8 | 19 | 6 | 1:7167 | Elliot et al. [38] |

| Latin America | |||||||||

| 2012–2016 | Petroleos Mexicanos Health Services | MS/MS | fixed | 20,018 (m 10,241) | 5 (m 5) | 25 (m 49) | 5 (m 5) | 1:4003 (m 1:2048) | Navarrete-Martinez et al. [65] |

| 2017 | Brazil | DMF | fixed | 10,527 | 0 | 0 | 0 | / | Camargo Neto et al. [66] |

* We include all patients carrying a GLA variant. ** Disease incidence is only an estimate, assuming that all genetically confirmed newborns will develop symptoms. *** Because most pilot NBS are anonymous, confirmatory tests could not be performed. In these studies, samples that screen positive biochemically are genotyped. Abbreviations: m: males; DMA: daily mean activity; DMF: digital microfluidics; MS/MS: tandem mass spectrometry.

We reported the results from more than 5 years of NBS for FD in northeastern Italy, based on the determination of α-GalA enzyme activity in DBS using a multiplex MS/MS assay. Since 2015, 173,342 newborns (89,485 males) were screened. A genetic variant in the GLA gene (1:7879 newborns, 1:4068 males) was confirmed in 22 males. Among them, 13 carried a known pathogenic later onset variant (1:6883 males), and 9 had VUS or benign variants. The most common pathogenic variant was the later onset variant p.Asn215Ser (three patients). All patients were asymptomatic at the last follow-up (mean age 3 years), and none were receiving specific treatment. We did not detect any heterozygotes among the 83,853 newborn females screened [45].

Asia: In Taiwan, FD NBS started in 2006 using the fluorometric assay and then MS/MS [17,23,41,59]. The prevalence of FD is very high in Taiwan. The IVS4+919G>A variant is the most common (82%, about 1 in 1600 males). This variant can activate an alternative splicing in intron 4, causing insertion of a 57-nucleotide sequence between exon 4 and 5 of the αGalA cDNA and subsequent premature termination after seven altered amino acid residues downstream from exon 4 [13]. This variant has been reported to be prevalently associated with cardiac involvement in FD, although a small portion of patients carrying this variant have clinical manifestations [67]. Due to the low number of common pathogenic variants, and the high false negative rate in females (especially carrying IVS4 variant), a DNA-based NBS has been implemented (see above) [51].

In Japan, enzyme-based pilot screening started in 2007 [60], whereas in China only recently it has been introduced [61].

USA: FD was proposed for inclusion in the Recommended Uniform Screening Panel (RUSP) in 2008. However, because of uncertainties about the NBS test’s sensitivity, the prevalence of later onset variants, the unknown effectiveness of treatment and possible immunological response and the lack of prospective NBS and treatment studies, the Advisory Committee on Heritable Disorders in Newborns and Children (ACHDNC) rejected the proposal [68]. However, local laws supported by NBS advocates and parents allowed the implementation of systemic screening for FD in several states. In 2013, Missouri became the first state to screen all newborns for multiple LSDs (including FD), using a DMF-based fluorescent assay. Within the first 6 months, 43,701 specimens were screened, and 15 newborns were reported to have a genetic diagnosis of FD (1:2913) [14]. In 2014, Illinois initiated a pilot screening program for five LSDs, including FD, using MS/MS, and it was followed by statewide screening in June 2015 [64]. Pilot studies and programs were then started in other states.

Europe: In Europe, the screening for LSDs is in its early stage. The first pilot study worldwide was conducted in 2003 in northern Italy using a fluorometric assay on 37,104 consecutive male newborns, and 12 of them were identified with FD (1 in 3100 males, of which 1 with a classic form) [22]. In Austria, a small pilot study was performed with almost 35,000 samples, using an MS/MS methodology, during which nine patients with FD were identified [54]. There was also a pilot screening study in Hungary on about 40,000 samples using MS/MS, and three cases of FD were confirmed [55]. A small pilot screening was also performed in Spain, with a high number of benign variants detected in confirmatory tests [52]. The most relevant number of screened newborns in Europe was reported by our group in 2021 (see above) [45].

These programs have demonstrated the feasibility of newborn screening for FD. It is difficult to make comparisons among studies because of the differences in screening techniques, the classification of later onset, benign variant and VUS, the cutoffs (usually more conservative at the start of the program), the numbers of screened newborns, the geographical/ethnical variation and the changes in the classification of variants over time as knowledge accumulates. While the positive predictive value (PPV, the fraction of test positives that are true positives) is the gold standard for evaluating medical tests, currently PPVs for NBS in FD cannot be used as a performance metric due to difficulty in the definition of true positives, because of the uncertainly in the onset of disease symptoms. In addition, the use of the false positive rate has the same problems. The only metric that can be reliably obtained is the ratio between the number of screen positives normalized to the number of newborns screened (the screen positive rate). This ratio can be used for prospective pilot studies, pilot studies with de-identified DBS and prospective NBS programs (PPV can only be obtained from live NBS programs). However, the rate of screen positives depends on the cutoff value chosen by each NBS laboratory [69].

Furthermore, disease incidence is only an estimate assuming that all “true positive” infants will develop symptoms. Moreover, most studies do not distinguish between male and female newborns, and these latter are lost to NBS. For example, a Spanish study reported a very high incidence of disease (1:394 births), but the number of screened newborns was relatively low (n = 14,600). Moreover, only 1 patient had a known pathogenic variant, while 25/37 carried benign variants [52]. Different genetic backgrounds can also explain differences in incidence between countries. For example, in Taiwan, high incidence of the later onset GLA splicing variant (IVS4+919G>A) was detected [17]. However, all studies showed that FD is surprisingly more prevalent than previously estimated (1:40,000 by Desnick et al. [5]), especially the later onset form, which may represent an important unrecognized genetic disease.

3.5. Recommendations for Management of Positive Neonates

In most programs, if the αGalA activity is below the cutoff, the sample is retested (in duplicate), and, if the average of the duplicate persists below the cutoff, a second spot is requested. If the activity of the second spot is still below the cutoff, the infant is referred to the Clinic Unit for confirmatory testing. Samples are generally collected at a definite time in the first week of life, in several programs a second sample is required for premature babies (e.g., <34 gestational weeks and/or weight < 2000 g) and for sick newborns (e.g., those receiving transfusion or parenteral nutrition) or for samples with low activities for several enzymes due to a suspected preanalytical error [14,33,45,52,54,65,70].

Notably, different laboratories have different methods of determining cutoff values. Some laboratories use fixed cutoff values, established after the analysis of a set of normal control specimens. However, enzyme activity shows seasonal variation, related to the environmental temperature and humidity. Therefore, it is optimal to change the cutoff value for each test batch (e.g., % daily mean activity, DMA) [61]. Another method to identify suspected positive newborns is the use of postanalytical tools, such as Collaborative Laboratory Integrate Reports CLIR [71]. This multivariate pattern recognition software compares each new case with disease and control profiles and determines a likelihood of disease score. It integrates all possible permutations of enzyme assay ratios (in multiplex assays) but also demographic information, such as age at specimen collection, birth weight and sex (that can impact white cell count and therefore enzyme activity) [72]. Sanders et al. demonstrated that CLIR tools markedly improves the performance of each NBS platform (false positive rates and PPVs) [34].

Before the initiation of the NBS, protocols for definitive diagnostic tests, genetic counseling, follow up and treatment should be defined. Wang et al. developed guidelines for the diagnostic confirmation and management of presymptomatic individuals with lysosomal diseases, but more recent guidelines are lacking [73].

They suggested that once the diagnosis of FD has been confirmed, baseline diagnostic studies should be obtained. The infant should be seen by the metabolic specialist at 6-month intervals and monitored for onset of Fabry symptoms. For the individuals who have atypical variants, the strategy for regular follow-up and therapeutic intervention should be different from those with the classic type [73].

Gragnaniello et al. suggested that patients carrying variants associated with later onset forms should be monitored every 12 months, with clinical, instrumental and biochemical assessments [45]. A suggested diagnostic and follow up algorithm for presymptomatic patients is presented in Table 4. However, further investigations are needed to find the optimal way for monitoring and treatment timing, especially for patients with unclassified, VUS and later onset variants. In part, the difficulty is due to the poor correlations of residual enzyme activity and genotype with the clinical phenotype. Long term follow-up programs will allow a better definition of natural history, management and response to therapies, providing answers to the many outstanding question.

Table 4.

Confirmatory tests and follow-up of positive infants.

| Timing | Suggested Tests |

|---|---|

| Diagnostic confirmation | Genetic analysis * (patient and parents), substrate quantification (plasma lysoGb3) and enzyme activity in leukocytes, lymphocytes or plasma (in males). |

| Baseline diagnostic studies | ECG, echocardiogram, ophthalmologic examination, renal function tests, plasma and/or urine GL3 |

| Follow up every 6 months (classic form) or 12 months (later onset form) | Clinical examination (angiokeratomas, hypohidrosis, gastrointestinal symptoms, limb pain), kidney (eGFR according to Schwartz formula, microalbuminuria, proteinuria), cardiac assessments (ECG, echocardiography, 24-h holter), neurologic evaluation, plasma lyso-Gb3. |

* Variants are classified according to published clinical reports and public databases.

An important aspect of the management of positive newborns is the family screening. The combination of a detailed pedigree analysis and cascade genetic testing of at-risk family members can increase the number of patients identified, improve early diagnosis and clarify the pathogenicity of novel GLA variants [74]. In several studies it is reported that none of the infants with FD identified by NBS had a positive family history of FD or relatives with symptoms suggestive of the disease [45,64]. However, when a family genetic screening was performed, all studied families had previously undiagnosed family members, symptomatic or not [23,45]. Germain and the International Fabry Family Screening Advisory Board reviewed the literature on the family screening. For 365 probands, reported in 82 publications, 1744 affected family members were identified, which is equivalent to an average of 4.8 additional affected family members per proband [74]. A similar number has also been reported in a US study [75]. Potential barriers to the implementation of family genetic testing in some countries include associated costs, low awareness of its importance and cultural and societal issues [74].

3.6. Benefits and Challenges of FD Newborn Screening

In 1968, Wilson and Jungner described 10 principles that should be met prior to introducing a screening program [76]. According to this algorithm, FD reaches a score of 8. Although the authors proposed a disease scoring ≥ 8.5 for consideration for NBS programs, it should be noted that most LSDs don’t reach this threshold [77,78]. Thus, the implementation of FD newborn screening is still controversial.

Advantages and disadvantages of the FD newborn screening are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Advantages and disadvantages of FD newborn screening.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Available methods for NBS on DBS | Enzyme based assays do not identify many female heterozygotes. |

| Approved treatments | Higher than expected numbers of later onset forms |

| Importance of early diagnosis and treatment, often delayed clinical diagnosis | Lack of definite guidelines for follow up and start therapy especially for later onset forms |

| Better knowledge of the natural history | Frequent detection of VUS or benign variants |

| Genetic counseling | Phenotype prediction can be difficult |

| Family screening | |

| High incidence, more frequent than previously expected |

Abbreviations: DBS: dried blood spot, NBS: newborn screening, VUS: variant of uncertain significance.

As discussed above, reliable and effective methods for screening on DBS are available. The disease is more prevalent than previously clinically estimated. Newborn screening allows the early diagnosis and treatment, leading to a better prognosis. Moreover, the diagnosis of a newborn can be followed by family counselling and screening.

Later onset forms: The high incidence of later onset forms has raised ethical issues. Detection in the newborn period may have a negative psychological impact on parents and carries the risk to create “vulnerable children” [79] or “patients in waiting” [80], labelled and overmedicated. Moreover, it increases the costs for diagnostic laboratory testing and follow-up visits. The long-term follow-up of these infants will be essential to understand the natural history of the disease (which includes the manifestations of the different phenotypes) and the impact of early treatment. However, an early diagnosis of the later onset forms may have several advantages. A significant number of patients currently remain mis- or undiagnosed for many years [18]. The implementation of NBS could avoid this “diagnostic odyssey”, allowing timely treatment and subsequently better outcome [64]. Moreover, their identification allows physicians to perform cascade genotyping in at risk family members and identify undiagnosed relatives [74].

VUS/benign variants: NBS revealed a high incidence of polymorphisms, e.g., p.Asp313Tyr in European population and p.Glu66Gln in Japan, that are considered to be non-pathogenic based on in vitro expression, lysoGb3 concentrations in plasma, prevalence in healthy alleles and clinical and histological features [81,82,83,84].

Screening for FD also reveals a high prevalence of individuals with VUS or novel not yet classified genetic variants [56]. To determine whether these variants were pathogenic or not, functional (e.g., in vitro analysis, in silico tools), biochemical (e.g., lysoGb3), pedigree analyses and especially clinical manifestations should be performed [59] and often many years are needed to correctly classify a variant. For example, in Caucasian newborns, the most frequent genetic alteration reported is p.Ala143Thr [45,54,64,85]. Although it has been reported in association with both classic [86] and later onset (renal and cardiac) FD [87], it has been recently suggested to be a benign variant. Study in COS cells demonstrated a high residual enzyme activity of 36% [22]. Reported individuals with this variant showed unspecific symptoms, but no increase of plasma Gb3 and LysoGb3 [88] and no storage in tissue biopsies [89,90]. The high incidence of this variant in gnomAD database (5.06 × 10−4) and in the screening programs supports its lack of pathogenicity [91]. Furthermore, the αGalA enzyme is localized within the lysosome, suggesting normal trafficking [92]. Therefore, the pathogenicity of this variant is still debatable [74,93,94].

Female newborns: Enzymatic tests are not reliable for screening females due to random X-inactivation in different tissues. False negative results with enzymatic assays are about 40% [95,96] (up to 80% in Taiwan, where the IVS4 variant is predominant) [97], whereas DNA-based methods appear to be more sensitive and reliable. In most countries, mutational heterogeneity hampers the use of molecular analysis for high-throughput screening. Nevertheless, genetic assays may be considered in the near future, specifically due to improved technologies.

NBS cannot accurately distinguish classic from later onset forms: The prediction of disease severity is difficult, because enzyme activity and genotype do not clearly correlate with the phenotype and there is a large number of private GLA variants [57]. Moreover, the influence of modifier genes or other genetic factors on phenotype severity may be confounding, since individuals with the same GLA variant may occasionally have variable clinical manifestations during disease progression [93]. For heterozygotes, lyonization makes presymptomatic prediction of phenotypic severity impossible [73]. The only test that seems to predict a classic form on NBS is lysoGb3 measurement (elevated) [47], but, as discussed above, it cannot accurately differentiate the different forms.

Ideally FD NBS program should include: (1) a combined enzymatic and genetic approach, to perform a complete screening of all patients (males and females), and the enzymatic and genetic approach would be complementary in supporting the difficult interpretation of genetic variants; (2) an improved biomarker to use as second tier test. At the moment we do not have an ideal disease-specific biomarker for Fabry disease. Plasma lysoGb3 has been established as a good diagnostic biomarker for Fabry disease [98]. Nevertheless, lysoGb3 is not highly sensitive and highly specific as lysoGb1 for NBS in Gaucher disease [99]. LysoGb3 correlates well with the classic form, male sex, but normal levels cannot rule out a later-onset form. Furthermore, most of the literature regarding lysoGb3 refers to measurements in adult Fabry patients, and we need more data on values during infancy; (3) a newborn screening program for FD should be associated with a long-term follow-up program. Indeed, only such a clinical follow-up could determine the impact of this early diagnosis in the real-life management.

However, despite these limitations, the opinion of FD patients about NBS is favorable. Several studies explored the opinion of FD patients (n = 88) on NBS for FD (and other later onset diseases). Most participants agree with NBS. They felt NBS could result in better current health, eliminate diagnostic odysseys, lead to more timely and efficacious treatment and lead to different life-decision, including lifestyle, financial and reproductive decisions [100,101,102]. A different opinion is reported by genetic healthcare providers. Indeed, Lisi et al. evaluated the opinion of 38 genetic healthcare providers: FD was viewed less favorable that other LSDs due to later age of onset (potential for medicalization, stigmatization and psychological burden) and ambiguity regarding prognosis [103].

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

The frequency and technical practicability make NBS for FD feasible and affordable to be extended to large population. However, several issues still need further study:

The lack of a second-tier test suitable to cover all the forms of the disease and reduce the recall rate;

No biochemical detection of heterozygous females;

The clinical interpretation of unclassified variants and VUS;

The impact of early diagnosis on patients with later onset forms.

Efforts to capture long term follow-up data, associated to functional characterization of the controversial variants, studies of biomarkers and modifier genes to a better phenotype prediction and patients’ management will be crucial to address important ethical issues. To conclude, both the benefits and risks of NBS merit further study, underscoring the need for long term follow up.

Abbreviations

4-MU: 4-methylumbelliferone. α-GalA: α-galactosidase A. DBS: dried blood spot. DMA: daily mean activity. DMF: digital microfluidics. ERT: enzyme replacement therapy. FD: Fabry disease. Gb3: globotriaosylceramide. lysoGb3: globotriaosylsphingosine. LSD: lysosomal storage disease. MS/MS: tandem mass spectrometry. NBS: newborn screening. PPV: positive predictive value. RUSP: Recommended Uniform Screening Panel. VUS: variant of uncertain significance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Germain D.P. Fabry Disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010;5:30. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-5-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kok K., Zwiers K.C., Boot R.G., Overkleeft H.S., Aerts J.M.F.G., Artola M. Fabry Disease: Molecular Basis, Pathophysiology, Diagnostics and Potential Therapeutic Directions. Biomolecules. 2021;11:271. doi: 10.3390/biom11020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laney D.A., Peck D.S., Atherton A.M., Manwaring L.P., Christensen K.M., Shankar S.P., Grange D.K., Wilcox W.R., Hopkin R.J. Fabry disease in infancy and early childhood: A systematic literature review. Genet. Med. 2015;17:323–330. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burlina A.P., Politei J. Fabry Disease. In: Burlina A.P., editor. Neurometabolic Hereditary Diseases of Adults. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2018. pp. 67–98. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desnick R.J., Ioannou Y.A., Eng C.M. Alpha-Galactosidase A Deficiency: Fabry Disease. In: Scriver C.R., Beaudet A.L., Sly W.S., Valle D., editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY, USA: 2001. pp. 3733–3774. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echevarria L., Benistan K., Toussaint A., Dubourg O., Hagege A.A., Eladari D., Jabbour F., Beldjord C., De Mazancourt P., Germain D.P. X-chromosome inactivation in female patients with Fabry disease. Clin. Genet. 2016;89:44–54. doi: 10.1111/cge.12613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck M., Cox T.M. Comment: Why are females with Fabry disease affected? Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2019;21:100529. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2019.100529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Massaccesi L., Burlina A., Baquero C.J., Goi G., Burlina A.P., Tettamanti G. Whole-Blood Alpha-D-Galactosidase A Activity for the Identification of Fabry’s Patients. Clin. Biochem. 2011;44:916–921. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.03.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Effraimidis G., Feldt-Rasmussen U., Rasmussen Å.K., Lavoie P., Abaoui M., Boutin M., Auray-Blais C. Globotriaosylsphingosine (Lyso-Gb 3) and Analogues in Plasma and Urine of Patients with Fabry Disease and Correlations with Long-Term Treatment and Genotypes in a Nationwide Female Danish Cohort. J. Med. Genet. 2021;58:692–700. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-107162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiffmann R., Murray G.J., Treco D., Daniel P., Sellos-Moura M., Myers M., Quirk J.M., Zirzow G.C., Borowski M., Loveday K., et al. Infusion of α-Galactosidase A Reduces Tissue Globotriaosylceramide Storage in Patients with Fabry Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:365–370. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eng C.M., Guffon N., Wilcox W.R., Germain D.P., Lee P., Waldek S., Caplan L., Linthorst G.E., Desnick R.J. Safety and Efficacy of Recombinant Human α-Galactosidase A Replacement Therapy in Fabry’s Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:9–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Germain D.P., Hughes D.A., Nicholls K., Bichet D.G., Giugliani R., Wilcox W.R., Feliciani C., Shankar S.P., Ezgu F., Amartino H., et al. Treatment of Fabry’s Disease with the Pharmacologic Chaperone Migalastat. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:545–555. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin H.-Y., Chong K.-W., Hsu J.-H., Yu H.-C., Shih C.-C., Huang C.-H., Lin S.-J., Chen C.-H., Chiang C.-C., Ho H.-J., et al. High Incidence of the Cardiac Variant of Fabry Disease Revealed by Newborn Screening in the Taiwan Chinese Population. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2009;2:450–456. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.862920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hopkin R.J., Jefferies J.L., Laney D.A., Lawson V.H., Mauer M., Taylor M.R., Wilcox W.R., Fabry Pediatric Expert Panel The management and treatment of children with Fabry disease: A United States-based perspective. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2016;117:104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biegstraaten M., Arngrímsson R., Barbey F., Boks L., Cecchi F., Deegan P.B., Feldt-Rasmussen U., Geberhiwot T., Germain D.P., Hendriksz C., et al. Recommendations for Initiation and Cessation of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Patients with Fabry Disease: The European Fabry Working Group Consensus Document. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015;10:36. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0253-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oqvist B., Brenner B.M., Oliveira J.P., Ortiz A., Schaefer R., Svarstad E., Wanner C., Zhang K., Warnock D.G. Nephropathy in Fabry Disease: The Importance of Early Diagnosis and Testing in High-Risk Populations. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009;24:1736–1743. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu T.-R., Hung S.-C., Chang F.-P., Yu W.-C., Sung S.-H., Hsu C.-L., Dzhagalov I., Yang C.-F., Chu T.-H., Lee H.-J., et al. Later Onset Fabry Disease, Cardiac Damage Progress in Silence. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;68:2554–2563. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.09.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Germain D.P., Altarescu G., Barriales-Villa R., Mignani R., Pawlaczyk K., Pieruzzi F., Terryn W., Vujkovac B., Ortiz A. An Expert Consensus on Practical Clinical Recommendations and Guidance for Patients with Classic Fabry Disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2022;137:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2022.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meikle P.J., Grasby D.J., Dean C.J., Lang D.L., Bockmann M., Whittle A.M., Fietz M.J., Simonsen H., Fuller M., Brooks D.A., et al. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2006;88:307–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meikle P.J., Ranieri E., Simonsen H., Rozaklis T., Ramsay S.L., Whitfield P.D., Fuller M., Christensen E., Skovby F., Hopwood J.J. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Clinical Evaluation of a Two-Tier Strategy. Pediatrics. 2004;114:909–916. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamoles N.A., Blanco M., Gaggioli D. Fabry disease: Enzymatic diagnosis in dried blood spots on filter paper. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2001;308:195–196. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(01)00478-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spada M., Pagliardini S., Yasuda M., Tukel T., Thiagarajan G., Sakuraba H., Ponzone A., Desnick R.J. High Incidence of Later-Onset Fabry Disease Revealed by Newborn Screening*. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;79:31–40. doi: 10.1086/504601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwu W.-L., Chien Y.-H., Lee N.-C., Chiang S.-C., Dobrovolny R., Huang A.-C., Yeh H.-Y., Chao M.-C., Lin S.-J., Kitagawa T., et al. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease in Taiwan Reveals a High Incidence of the Later-Onset GLA Mutation c.936+919G>A (IVS4+919G>A) Hum. Mutat. 2009;30:1397–1405. doi: 10.1002/humu.21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sista R.S., Eckhardt A.E., Wang T., Graham C., Rouse J.L., Norton S.M., Srinivasan V., Pollack M.G., Tolun A.A., Bali D., et al. Digital Microfluidic Platform for Multiplexing Enzyme Assays: Implications for Lysosomal Storage Disease Screening in Newborns. Clin. Chem. 2011;57:1444–1451. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2011.163139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sista R., Eckhardt A.E., Wang T., Séllos-Moura M., Pamula V.K. Rapid, Single-Step Assay for Hunter Syndrome in Dried Blood Spots Using Digital Microfluidics. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2011;412:1895–1897. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sista R.S., Wang T., Wu N., Graham C., Eckhardt A., Winger T., Srinivasan V., Bali D., Millington D.S., Pamula V.K. Multiplex Newborn Screening for Pompe, Fabry, Hunter, Gaucher, and Hurler Diseases Using a Digital Microfluidic Platform. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2013;424:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millington D., Bali D. Current State of the Art of Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2018;4:24. doi: 10.3390/ijns4030024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matern D., Gavrilov D., Oglesbee D., Raymond K., Rinaldo P., Tortorelli S. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Semin. Perinatol. 2015;39:206–216. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Y., Scott C.R., Chamoles N.A., Ghavami A., Pinto B.M., Turecek F., Gelb M.H. Direct Multiplex Assay of Lysosomal Enzymes in Dried Blood Spots for Newborn Screening. Clin. Chem. 2004;50:1785–1796. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.035907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duffey T.A., Bellamy G., Elliott S., Fox A.C., Glass M., Turecek F., Gelb M.H., Scott C.R. A Tandem Mass Spectrometry Triplex Assay for the Detection of Fabry, Pompe, and Mucopolysaccharidosis-I (Hurler) Clin. Chem. 2010;56:1854–1861. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.152009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gelb M.H., Scott C.R., Turecek F. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Clin. Chem. 2015;61:335–346. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.225771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gelb M., Lukacs Z., Ranieri E., Schielen P. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Methodologies for Measurement of Enzymatic Activities in Dried Blood Spots. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2018;5:1. doi: 10.3390/ijns5010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burlina A.B., Polo G., Rubert L., Gueraldi D., Cazzorla C., Duro G., Salviati L., Burlina A.P. Implementation of Second-Tier Tests in Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Disorders in North Eastern Italy. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2019;5:24. doi: 10.3390/ijns5020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders K.A., Gavrilov D.K., Oglesbee D., Raymond K.M., Tortorelli S., Hopwood J.J., Lorey F., Majumdar R., Kroll C.A., McDonald A.M., et al. A Comparative Effectiveness Study of Newborn Screening Methods for Four Lysosomal Storage Disorders. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020;6:44. doi: 10.3390/ijns6020044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spáčil Z., Elliott S., Reeber S.L., Gelb M.H., Scott C.R., Tureček F. Comparative Triplex Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assays of Lysosomal Enzyme Activities in Dried Blood Spots Using Fast Liquid Chromatography: Application to Newborn Screening of Pompe, Fabry, and Hurler Diseases. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:4822–4828. doi: 10.1021/ac200417u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schielen P., Kemper E., Gelb M. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Diseases: A Concise Review of the Literature on Screening Methods, Therapeutic Possibilities and Regional Programs. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2017;3:6. doi: 10.3390/ijns3020006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peake R., Bodamer O. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2016;6:051–060. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1593843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elliott S., Buroker N., Cournoyer J.J., Potier A.M., Trometer J.D., Elbin C., Schermer M.J., Kantola J., Boyce A., Turecek F., et al. Pilot Study of Newborn Screening for Six Lysosomal Storage Diseases Using Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2016;118:304–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar A.B., Masi S., Ghomashchi F., Chennamaneni N.K., Ito M., Scott C.R., Turecek F., Gelb M.H., Spacil Z. Tandem Mass Spectrometry Has a Larger Analytical Range than Fluorescence Assays of Lysosomal Enzymes: Application to Newborn Screening and Diagnosis of Mucopolysaccharidoses Types II, IVA, and VI. Clin. Chem. 2015;61:1363–1371. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.242560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelb M.H., Ronald Scott C., Turecek F., Liao H.-C. Comparison of Tandem Mass Spectrometry to Fluorimetry for Newborn Screening of LSDs. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2017;12:80–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao H.-C., Chiang C.-C., Niu D.-M., Wang C.-H., Kao S.-M., Tsai F.-J., Huang Y.-H., Liu H.-C., Huang C.-K., Gao H.-J., et al. Detecting Multiple Lysosomal Storage Diseases by Tandem Mass Spectrometry—A National Newborn Screening Program in Taiwan. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2014;431:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Duro G., Zizzo C., Cammarata G., Burlina A., Burlina A., Polo G., Scalia S., Oliveri R., Sciarrino S., Francofonte D., et al. Mutations in the GLA Gene and LysoGb3: Is It Really Anderson-Fabry Disease? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:3726. doi: 10.3390/ijms19123726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Polo G., Burlina A.P., Ranieri E., Colucci F., Rubert L., Pascarella A., Duro G., Tummolo A., Padoan A., Plebani M., et al. Plasma and Dried Blood Spot Lysosphingolipids for the Diagnosis of Different Sphingolipidoses: A Comparative Study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM. 2019;57:1863–1874. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2018-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malvagia S., Ferri L., Della Bona M., Borsini W., Cirami C.L., Dervishi E., Feriozzi S., Gasperini S., Motta S., Mignani R., et al. Multicenter Evaluation of Use of Dried Blood Spot Compared to Conventional Plasma in Measurements of Globotriaosylsphingosine (LysoGb3) Concentration in 104 Fabry Patients. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. CCLM. 2021;59:1516–1526. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2021-0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gragnaniello V., Burlina A.P., Polo G., Giuliani A., Salviati L., Duro G., Cazzorla C., Rubert L., Maines E., Germain D.P., et al. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease in Northeastern Italy: Results of Five Years of Experience. Biomolecules. 2021;11:951. doi: 10.3390/biom11070951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chien Y.-H., Lee N.-C., Chen P.-W., Yeh H.-Y., Gelb M.H., Chiu P.-C., Chu S.-Y., Lee C.-H., Lee A.-R., Hwu W.-L. Newborn Screening for Morquio Disease and Other Lysosomal Storage Diseases: Results from the 8-Plex Assay for 70,000 Newborns. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2020;15:38. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-1322-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spada M., Kasper D., Pagliardini V., Biamino E., Giachero S., Porta F. Metabolic Progression to Clinical Phenotype in Classic Fabry Disease. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2017;43:1. doi: 10.1186/s13052-016-0320-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kritzer A., Siddharth A., Leestma K., Bodamer O. Early Initiation of Enzyme Replacement Therapy in Classical Fabry Disease Normalizes Biomarkers in Clinically Asymptomatic Pediatric Patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2019;21:100530. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2019.100530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tai C.-L., Liu M.-Y., Yu H.-C., Chiang C.-C., Chiang H., Suen J.-H., Kao S.-M., Huang Y.-H., Wu T.J.-T., Yang C.-F., et al. The Use of High Resolution Melting Analysis to Detect Fabry Mutations in Heterozygous Females via Dry Bloodspots. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2012;413:422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee S.-H., Li C.-F., Lin H.-Y., Lin C.-H., Liu H.-C., Tsai S.-F., Niu D.-M. High-Throughput Detection of Common Sequence Variations of Fabry Disease in Taiwan Using DNA Mass Spectrometry. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2014;111:507–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu Y.-H., Huang P.-H., Wang L.-Y., Hsu T.-R., Li H.-Y., Lee P.-C., Hsieh Y.-P., Hung S.-C., Wang Y.-C., Chang S.-K., et al. Improvement in the Sensitivity of Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease among Females through the Use of a High-Throughput and Cost-Effective Method, DNA Mass Spectrometry. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;63:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s10038-017-0366-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Colon C., Ortolano S., Melcon-Crespo C., Alvarez J.V., Lopez-Suarez O.E., Couce M.L., Fernández-Lorenzo J.R. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease in the North-West of Spain. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2017;176:1075–1081. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2950-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paciotti S., Persichetti E., Pagliardini S., Deganuto M., Rosano C., Balducci C., Codini M., Filocamo M., Menghini A.R., Pagliardini V., et al. First Pilot Newborn Screening for Four Lysosomal Storage Diseases in an Italian Region: Identification and Analysis of a Putative Causative Mutation in the GBA Gene. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2012;413:1827–1831. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mechtler T.P., Stary S., Metz T.F., De Jesús V.R., Greber-Platzer S., Pollak A., Herkner K.R., Streubel B., Kasper D.C. Neonatal Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Feasibility and Incidence from a Nationwide Study in Austria. Lancet. 2012;379:335–341. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61266-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wittmann J., Karg E., Turi S., Legnini E., Wittmann G., Giese A.-K., Lukas J., Gölnitz U., Klingenhäger M., Bodamer O., et al. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders in Hungary. In: SSIEM, editor. JIMD Reports—Case and Research Reports, 2012/3. Volume 6. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2012. pp. 117–125. JIMD Reports. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sawada T., Kido J., Yoshida S., Sugawara K., Momosaki K., Inoue T., Tajima G., Sawada H., Mastumoto S., Endo F., et al. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease in the Western Region of Japan. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2020;22:100562. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2019.100562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Inoue T., Hattori K., Ihara K., Ishii A., Nakamura K., Hirose S. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease in Japan: Prevalence and Genotypes of Fabry Disease in a Pilot Study. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;58:548–552. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chinen Y., Nakamura S., Yoshida T., Maruyama H., Nakamura K. A New Mutation Found in Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease Evaluated by Plasma Globotriaosylsphingosine Levels. Hum. Genome Var. 2017;4:17002. doi: 10.1038/hgv.2017.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liao H.-C., Hsu T.-R., Young L., Chiang C.-C., Huang C.-K., Liu H.-C., Niu D.-M., Chen Y.-J. Functional and Biological Studies of α-Galactosidase A Variants with Uncertain Significance from Newborn Screening in Taiwan. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018;123:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chiang S.-C., Chen P.-W., Hwu W.-L., Lee A.-J., Chen L.-C., Lee N.-C., Chiou L.-Y., Chien Y.-H. Performance of the Four-Plex Tandem Mass Spectrometry Lysosomal Storage Disease Newborn Screening Test: The Necessity of Adding a 2nd Tier Test for Pompe Disease. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2018;4:41. doi: 10.3390/ijns4040041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li R., Tian L., Gao Q., Guo Y., Li G., Li Y., Sun M., Yan Y., Li Q., Nie W., et al. Establishment of Cutoff Values for Newborn Screening of Six Lysosomal Storage Disorders by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Front. Pediatr. 2022;10:814461. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.814461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott C.R., Elliott S., Buroker N., Thomas L.I., Keutzer J., Glass M., Gelb M.H., Turecek F. Identification of Infants at Risk for Developing Fabry, Pompe, or Mucopolysaccharidosis-I from Newborn Blood Spots by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Pediatr. 2013;163:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wasserstein M.P., Caggana M., Bailey S.M., Desnick R.J., Edelmann L., Estrella L., Holzman I., Kelly N.R., Kornreich R., Kupchik S.G., et al. The New York Pilot Newborn Screening Program for Lysosomal Storage Diseases: Report of the First 65,000 Infants. Genet. Med. 2019;21:631–640. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burton B.K., Charrow J., Hoganson G.E., Waggoner D., Tinkle B., Braddock S.R., Schneider M., Grange D.K., Nash C., Shryock H., et al. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders in Illinois: The Initial 15-Month Experience. J. Pediatr. 2017;190:130–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Navarrete-Martínez J.I., Limón-Rojas A.E., Gaytán-García M.D.J., Reyna-Figueroa J., Wakida-Kusunoki G., Delgado-Calvillo M.D.R., Cantú-Reyna C., Cruz-Camino H., Cervantes-Barragán D.E. Newborn Screening for Six Lysosomal Storage Disorders in a Cohort of Mexican Patients: Three-Year Findings from a Screening Program in a Closed Mexican Health System. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017;121:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Camargo Neto E., Schulte J., Pereira J., Bravo H., Sampaio-Filho C., Giugliani R. Neonatal Screening for Four Lysosomal Storage Diseases with a Digital Microfluidics Platform: Initial Results in Brazil. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2018;41:414–416. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-gmb-2017-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ishii S., Nakao S., Minamikawa-Tachino R., Desnick R.J., Fan J.-Q. Alternative Splicing in the A-Galactosidase A Gene: Increased Exon Inclusion Results in the Fabry Cardiac Phenotype. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:994–1002. doi: 10.1086/339431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Previously Nominated Conditions. [(accessed on 1 April 2023)]; Available online: http://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/mchbadvisory/heritabledisorders/nominatecondition/workgroup.html.

- 69.Gelb M. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Diseases: Methodologies, Screen Positive Rates, Normalization of Datasets, Second-Tier Tests, and Post-Analysis Tools. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2018;4:23. doi: 10.3390/ijns4030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burlina A.B., Polo G., Salviati L., Duro G., Zizzo C., Dardis A., Bembi B., Cazzorla C., Rubert L., Zordan R., et al. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders by Tandem Mass Spectrometry in North East Italy. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2018;41:209–219. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.CLIR [(accessed on 1 April 2023)]. Available online: https://Clir.Mayo.Edu/

- 72.Hall P.L., Marquardt G., McHugh D.M.S., Currier R.J., Tang H., Stoway S.D., Rinaldo P. Postanalytical Tools Improve Performance of Newborn Screening by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Genet. Med. 2014;16:889–895. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang R.Y., Bodamer O.A., Watson M.S., Wilcox W.R. Lysosomal Storage Diseases: Diagnostic Confirmation and Management of Presymptomatic Individuals. Genet. Med. 2011;13:457–484. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e318211a7e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Germain D.P., Moiseev S., Suárez-Obando F., Al Ismaili F., Al Khawaja H., Altarescu G., Barreto F.C., Haddoum F., Hadipour F., Maksimova I., et al. The Benefits and Challenges of Family Genetic Testing in Rare Genetic Diseases—Lessons from Fabry Disease. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2021;9:e1666. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Laney D.A., Fernhoff P.M. Diagnosis of Fabry Disease via Analysis of Family History. J. Genet. Couns. 2008;17:79–83. doi: 10.1007/s10897-007-9128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilson J.M.G., Jungner G., WHO . Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1968. 163p Public Health Papers no. 34. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Burlina A., Jones S.A., Chakrapani A., Church H.J., Heales S., Wu T.H.Y., Morton G., Roberts P., Sluys E.F., Cheillan D. A New Approach to Objectively Evaluate Inherited Metabolic Diseases for Inclusion on Newborn Screening Programmes. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022;8:25. doi: 10.3390/ijns8020025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jones S.A., Cheillan D., Chakrapani A., Church H.J., Heales S., Wu T.H.Y., Morton G., Roberts P., Sluys E.F., Burlina A. Application of a Novel Algorithm for Expanding Newborn Screening for Inherited Metabolic Disorders across Europe. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2022;8:20. doi: 10.3390/ijns8010020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kokotos F. The Vulnerable Child Syndrome. Pediatr. Rev. 2009;30:193–194. doi: 10.1542/pir.30.5.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Timmermans S., Buchbinder M. Patients-in-Waiting: Living between Sickness and Health in the Genomics Era. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010;51:408–423. doi: 10.1177/0022146510386794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kobayashi M., Ohashi T., Fukuda T., Yanagisawa T., Inomata T., Nagaoka T., Kitagawa T., Eto Y., Ida H., Kusano E. No Accumulation of Globotriaosylceramide in the Heart of a Patient with the E66Q Mutation in the α-Galactosidase A Gene. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;107:711–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Togawa T., Tsukimura T., Kodama T., Tanaka T., Kawashima I., Saito S., Ohno K., Fukushige T., Kanekura T., Satomura A., et al. Fabry Disease: Biochemical, Pathological and Structural Studies of the α-Galactosidase A with E66Q Amino Acid Substitution. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;105:615–620. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yasuda M., Shabbeer J., Benson S.D., Maire I., Burnett R.M., Desnick R.J. Fabry Disease: Characterization of Alpha-Galactosidase A Double Mutations and the D313Y Plasma Enzyme Pseudodeficiency Allele. Hum. Mutat. 2003;22:486–492. doi: 10.1002/humu.10275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eng C.M., Resnick-Silverman L.A., Niehaus D.J., Astrin K.H., Desnick R.J. Nature and Frequency of Mutations in the A-Galactosidase A Gene That Cause Fabry Disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;53:1186–1197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Viall S., Dennis A., Yang A. Newborn Screening for Fabry Disease in Oregon: Approaching the Iceberg of A143T and Variants of Uncertain Significance. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part C. 2022;190:206–214. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Elliott P., Baker R., Pasquale F., Quarta G., Ebrahim H., Mehta A.B., Hughes D.A., on behalf of the ACES Study Group Prevalence of Anderson-Fabry Disease in Patients with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: The European Anderson-Fabry Disease Survey. Heart. 2011;97:1957–1960. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Brabander I., Yperzeele L., Ceuterick-De Groote C., Brouns R., Baker R., Belachew S., Delbecq J., De Keulenaer G., Dethy S., Eyskens F., et al. Phenotypical Characterization of α-Galactosidase A Gene Mutations Identified in a Large Fabry Disease Screening Program in Stroke in the Young. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2013;115:1088–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Krüger R., Tholey A., Jakoby T., Vogelsberger R., Mönnikes R., Rossmann H., Beck M., Lackner K.J. Quantification of the Fabry Marker LysoGb3 in Human Plasma by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B. 2012;883–884:128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Terryn W., Vanholder R., Hemelsoet D., Leroy B.P., Van Biesen W., De Schoenmakere G., Wuyts B., Claes K., De Backer J., De Paepe G., et al. Questioning the Pathogenic Role of the GLA p.Ala143Thr “Mutation” in Fabry Disease: Implications for Screening Studies and ERT. In: Zschocke J., Gibson K.M., Brown G., Morava E., Peters V., editors. JIMD Reports—Case and Research Reports, 2012/5. Volume 8. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2012. pp. 101–108. JIMD Reports. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lenders M., Weidemann F., Kurschat C., Canaan-Kühl S., Duning T., Stypmann J., Schmitz B., Reiermann S., Krämer J., Blaschke D., et al. Alpha-Galactosidase A p.A143T, a Non-Fabry Disease-Causing Variant. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2016;11:54. doi: 10.1186/s13023-016-0441-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.GnomAD: The Genome Aggregation Database. [(accessed on 1 April 2023)]. Available online: https://Gnomad.Broadinstitute.Org.

- 92.Garman S.C. Structure-Function Relationships in α-Galactosidase A: Structure-Function Relationships in α-Galactosidase A. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:6–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00198.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Germain D.P., Levade T., Hachulla E., Knebelmann B., Lacombe D., Seguin V.L., Nguyen K., Noël E., Rabès J. Challenging the Traditional Approach for Interpreting Genetic Variants: Lessons from Fabry Disease. Clin. Genet. 2022;101:390–402. doi: 10.1111/cge.14102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schiffmann R., Fuller M., Clarke L.A., Aerts J.M.F.G. Is It Fabry Disease? Genet. Med. 2016;18:1181–1185. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Linthorst G.E., Poorthuis B.J.H.M., Hollak C.E.M. Enzyme Activity for Determination of Presence of Fabry Disease in Women Results in 40% False-Negative Results. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008;51:2082. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Linthorst G.E., Vedder A.C., Aerts J.M.F.G., Hollak C.E.M. Screening for Fabry Disease Using Whole Blood Spots Fails to Identify One-Third of Female Carriers. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2005;353:201–203. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hsu T.-R., Niu D.-M. Fabry Disease: Review and Experience during Newborn Screening. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2018;28:274–281. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Burlina A., Brand E., Hughes D., Kantola I., Krämer J., Nowak A., Tøndel C., Wanner C., Spada M. An expert consensus on the recommendations for the use of biomarkers in Fabry disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2023;139:107585. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2023.107585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Revel-Vilk S., Fuller M., Zimran A. Value of Glucosylsphingosine (Lyso-Gb1) as a Biomarker in Gaucher Disease: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:7159. doi: 10.3390/ijms21197159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bouwman M.G., de Ru M.H., Linthorst G.E., Hollak C.E.M., Wijburg F.A., van Zwieten M.C.B. Fabry Patients’ Experiences with the Timing of Diagnosis Relevant for the Discussion on Newborn Screening. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2013;109:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lisi E.C., Ali N. Opinions of Adults Affected with Later-onset Lysosomal Storage Diseases Regarding Newborn Screening: A Qualitative Study. J. Genet. Couns. 2021;30:1544–1558. doi: 10.1002/jgc4.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lisi E.C., Gillespie S., Laney D., Ali N. Patients’ Perspectives on Newborn Screening for Later-Onset Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2016;119:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lisi E.C., McCandless S.E. Newborn Screening for Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Views of Genetic Healthcare Providers. J. Genet. Couns. 2016;25:373–384. doi: 10.1007/s10897-015-9879-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]