Abstract

Oligonucleotide-functionalized graphene biosensors show immense promise for use as label-free point of care devices for detection of nucleic acid biomarkers at clinically relevant levels. Graphene-based nucleic acid sensors can be fabricated at low cost and have been shown to reach limits of detection in the attomolar range. Here we demonstrate devices functionalized with 22mer or 8omer DNA probes are capable of detecting full length genomic HIV-1 subtype B RNA, with a limit of detection below 1 aM in nuclease free water. We also show that these sensors are suitable for detection directly in Qiazol lysis reagent, again with a limit of detection below 1 aM for both 22mer and 8omer probes.

Keywords: Graphene, Biosensors, Attomolar, Viral RNA, Nucleic Acid Detection

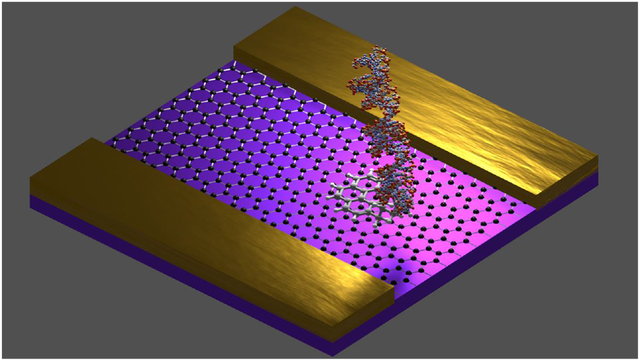

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The existence of scalable fabrication methods 1 and low limits of detection 2, 3 make graphene field effect transistors (GFETs) excellent candidates for the monitoring of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) viral load 4-6. When HIV-1 infection is controlled with antiretroviral therapy (ART) medications, viral load can be suppressed to undetectable levels in plasma, which eliminates the risk of transmitting the virus to others 7-9. To ensure that patients are fully suppressed, HIV viral load must be monitored. Furthermore, extensive efforts are currently focused on developing strategies to sustain viral suppression in the absence of ART 10, but frequent monitoring for viral rebound will be critical for this approach. Finally HIV-1 infection in newborns cannot be done by antibody assay due to placental transfer of maternal antibodies, so direct measurement of virus is necessary 11, which is a challenge in resource limited settings. Viral load is monitored by detection and quantifying viral RNA genome copy numbers in plasma. Currently there are no FDA-approved at home tests to directly monitor HIV viral load; viral load monitoring must be done through a doctor’s office and involves the use of expensive qRT-PCR machinery 12.

Graphene FETs are particularly promising for this application. Graphene intrinsically offers very high sensitivity to charged target molecules since all electronic orbitals in the material are strongly coupled to the immediate environment. GFET sensors for blood sugar 13, and nucleic acids 2,14 have been the subject of earlier reports. There are reports of DNA and RNA detection at the aM level 3,15; the use of “crumpled” graphene has been reported to provide sensitivity of 600 zM 16, although it remains to be seen if this material is suitable for scaling to production. Electronic detection may be performed in the biological fluid itself using an electrolytic gate or, as in this work, the GFET sensor can be incubated in the target solution, washed, and then measured in a “dry” state, which eliminates the need for a complex microfluidic system. We are not aware of any reports of direct detection of full genomic viral RNA, which is the subject of this work.

Here we describe a method for using oligonucleotide coupled graphene biosensors to detect full genomic length HIV-1 subtype B RNA, for the eventual purpose of detecting a clinically meaningful low (200 copies/ml or about 0.5 aM 17-20) HIV-1 viral load indicative of early rebound or drug failure. The recombinant HIV RNA used in these experiments was noninfectious due to missing its 3’ and 5’ long terminal repeats. When detecting in nuclease free water, our graphene biosensors have a limit of detection of 0.1 aM for 8omer probe, and 1 aM for 22mer probes. When detecting in Qiazol lysis reagent, which is a candidate reagent for a home test, both 22mer- and 8omer-based biosensors have a limit of detection of 0.1 aM. These positive results represent a significant step towards the ultimate goal of graphene-based biosensors for home tests for monitoring of HIV viral load.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. GFET fabrication and electronic measurement

GFET biosensors were fabricated as described in Materials and Methods using wafer scale photolithographic processing. Each wafer held 11 arrays, with each array comprised of 52 individual GFET devices arranged into 4 quadrants The graphene used for the biosensor arrays was grown in-house by chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and assessed for quality via Raman spectroscopy and electronic measurement (Supplemental Information). The CVD-grown graphene material was of excellent quality, with a minimal D peak (G/D peak ratio <0.05) and a 2D/G peak ratio of −2.7. Electronic measurements were performed using a wafer probing system capable of measuring the current-gate voltage (I-Vg) characteristic of each of the 52 GFET devices simultaneously. The Dirac voltages were then obtained from each I-Vg curve by fitting the hole branch of the curve to the form

| (1) |

where is the gate capacitance per unit area for 285nm-thick SiO2 (12.1 nF/cm2), the electrical conductivity as a function of gate voltage, the Dirac voltage, the gate voltage, the saturation conductivity as approaches −∞, and the hole carrier mobility 21,22 . The electronic measurements confirmed that unfunctionalized graphene devices exhibited very high uniformity across a wafer and between wafers, with an average Dirac voltage of 3.8 ± 0.5 V and a hole carrier mobility of 4150± 190 cm2V −1s −1 (Supplemental Information).

2.2. GFET probe selection

DNA oligonucleotide probes used for the graphene biosensors (Supplemental Information) were selected to be complementary to the integrase region of the HIV-1 subtype B (strain NL4) pol gene (nucleotides 4930-5059) and the HIV-1 subtype B gag gene (nucleotides 1299-1377), as determined by HXB2 sequencing 23, 24. The pol and gag gene regions were selected due to their relatively high sequence similarity across HIV-1 clade B viruses 25, 26. Probes of different length were selected to determine whether this would affect the sensing signal, with 22 nucleotides being the usual size for PCR probes and 80 nucleotides being the oligomer length that produced 1 aM limit of detection in our previously published work 3.

2.3. GFET functionalization and electronic characterization

The graphene FET arrays were functionalized using the linker molecule 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (PBASE), which was used to immobilize the probe molecule on the graphene surface. (See the Methods section for additional details) PBASE interacts with graphene via π−π stacking, and with the probe molecule via amine reactive cross-linking chemistry. After each functionalization step, the I-Vg characteristics of the biosensor devices were measured. Successful functionalization was confirmed by the observation of a shift in the Dirac voltage after each step (Supplemental Information). This shift is ascribed to an electrostatic chemical gating effect 27, and was used to determine the surface coverage of the probe molecules on the graphene channel. The surface coverage was estimated to be ~200 molecules per μm2 for the gag and pol 80mer probes and ~370 molecules per μm2 for the gag and pol 22mer probes.

2.4. Controls for RNA detection in Nuclease free water

We demonstrated the selectivity of the graphene biosensors by incubating probe functionalized sensors with 1pM concentration of the sense HIV-1 RNA sequence, as well as 1pM of the antisense HIV-1 RNA sequence 28 as a negative control. Compared to the signal produced by the sense HIV-1 RNA target, ~ 10 V for 22mer gag and pol and ~14 V for 80mer gag and pol, the signals for the antisense RNA were greatly diminished at ~2V for each of the 4 probe molecules (Supplemental Information). This confirmes that the sensors were cable of binding to their intended target sequences, and that they have a specificity for HIV-1 subtype B RNA.

2.5. Detection of viral RNA in Nuclease free water

For initial HIV-1 RNA detection, data was collected from HIV-1 RNA samples serial diluted into Nuclease free water as described in the Methods section. Sensing data was collected for all four probes and reported in dose response plot as shown in (Figure 1). For sensing experiments, we used 10 μL sample droplets from our 100 μL serial diluted sample solutions. With this droplet volume, we expect that concentrations below ~ 0.1 aM would most likely contain 0 target molecules. Each sample droplet was placed on an individual quadrant of the graphene biosensor array; the relative Dirac voltage shifts for each quadrant after target incubation were individually analyzed, and then pooled for each RNA concentration. When diluted in Nuclease free water, sensors based on 80mer probes were capable of detecting HIV-1 RNA with a limit of detection of 0.1 aM, while sensors incorporating 22mer probes were capable of detecting with a limit of 1.0 aM. This translates into detecting as few as 10 RNA molecules per sample droplet for 22mer, and 1 RNA molecule per sample droplet for 80mer. There was no significant difference in the detection behavior of the pol and gag probes, with both having similar limits of detection and voltage shifts.

Figure 1:

Dose-response curve for (blue) 22mer pol, (green) 22mer gag, (orange) 80mer pol and (purple) 80mer gag GFET devices after incubation with HIV-1 type B RNA diluted in nuclease free water. All of the devices are capable of detecting HIV 1 type-B RNA at the few copy level (1aM).

2.6. Controls for viral RNA detection in Qiazol reagent

In addition to detection of HIV-1 RNA in Nuclease free water (the usual end result of RNA isolation techniques), we tested the capability of graphene biosensors for detecting HIV-1 RNA in a lysis solution, which is potentially relevant for a home test or point-of-care system. To this end, the RNA target was diluted in Qiazol, a phenol-guanidine based lysis reagent produced by Qiagen N.V. To ensure the selectivity of devices was maintained, we incubated each of our probe functionalized sensors with 1fM concentration of sense HIV-1 RNA diluted in Qiazol, as well as 1fM of antisense HIV-1 RNA diluted in Qiazol as a negative control. The signals produced by the sense RNA sequence were ~ 40 V for both the 22mer and 80mer gag and pol probe molecules, while the signals produced by the negative control were ~ 3 V for each of the probe molecules. This difference in signal size confirms that our devices continue to be specific for the sense sequence even in complex solution.

2.7. Detection of viral RNA in Qiazol reagent

After confirming sensor selectivity, we performed detection experiments for various concentrations of serial diluted HIV-1 RNA in Qiazol reagent. This was done by incubating each quadrant of the GFET chip with 10 μL of Qiazol-diluted RNA samples, and independently analyzing the shift data collected from each isolated quadrant. For each of the probes tested, the relative Dirac Voltage shifts for RNA detection in Qiazol reagent were about 3 times larger than that of the same concentrations diluted in Nuclease free water (Figure 2). The limit of detection for Qiazol was 0.1 aM for both the 22mer and 80mer probes.

Figure 2:

Dose-response curve for (blue) 22mer pol, (green) 22mer gag, (orange) 80mer pol, and (purple) 80mer gag GFET devices after incubation with HIV-1 type B RNA diluted in Qiazol lysis reagent. The limit of detection is 0.1 aM for all of the devices.

2.8. Detection reproducibility and response range

As is often the case for GFET devices 2 and functionalized GFETs 13, we observed significant sensor-to-sensor variation in the value of the Dirac voltage (Supplemental Information). However, we also found excellent reproducibility in the Relative Dirac Voltage Shift that was induced by bound target molecules. This is reflected in the error bars in Figures 1 and 2, and also in the Supplemental Information. Based on the data collected in these experiments, we estimate the effective target response range to be 1 aM to 1 fM in Nuclease free water and 0.1 aM to 1 fM in Qiazol. Although comparatively narrow, this is suitable for the intended application, where our goal is a measurable response to 0.5 aM in Qiazol, which would indicate possible loss of viral suppression and the need for medical intervention.

3. Conclusion

Here we have shown that functionalized graphene biosensors are capable of detecting full genomic length HIV-1 subtype B RNA when diluted in Nuclease free water and Qiazol lysis reagent. There was minimal difference in the sensing signals and limits of detection for the two probe lengths, as well as for the two probe gene targets. The sensing devices for HIV-1 RNA diluted in Nuclease free water had a limit of detection of 1 aM using 22mer probes, and a limit of 0.1 aM using 80mer probes specific to the gag and pol regions of the HIV-1 subtype B genome. Furthermore, we have shown that both our 22mer and 80mer devices are capable of detecting genomic length HIV-1 subtype B RNA to limit of 0.1 aM in Qiazol lysis reagent. This confirms that our devices are capable of monitoring clinically meaningful low viral loads of HIV RNA, for example 200-1000 copies/ml (0.3-1.5 aM), in both simple and complex solutions. Key next questions are sensitivity for clinical isolates of HIV subtype B, which will not be perfectly sequence-matched to the probes, and development of methods for isolation of viral RNA from biological solution (plasma) that are suitable for home or point-of-care use.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Graphene Growth

Graphene was grown by CVD in a 4” furnace on a catalytic Cu foil substrate (Alfa Aesar, 99.8%). First, the furnace was heated to 1020 °C and held at that temperature for 1 hr to anneal the foil, all under a H2 (99.999% purity) flow of 80 sccm. For graphene growth, maintaining the 80 sccm flow of H2, a 10 sscm flow of CH4 (99.999% purity) was introduced for 20 minutes. Following the completion of the growth, the furnace was cooled to 900C with the gases still flowing, at which time the furnace was slid to one side to rapidly cool the copper foil. At 500 °C, the furnace lid was opened and the methane turned off. At 80 °C, the H2 was turned off, and the furnace was allowed to cool to room temperature before the foil was removed.

4.2. Graphene Transfer

A sacrificial layer of 400 μm of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA, MicroChem A4 950K) was spin-coated onto the surface of the graphene/Cu foil. Transfer of graphene was carried out via an electrolysis bubbling method utilizing a 50 mM NaOH solution in deionized water with one electrode attached to the Cu foil and another in contact with the NaOH solution. The formation of H2 bubbles at the interface of the PMMA/graphene and the Cu foil separated the film from the foil, and the film was then washed in a series of DI water baths before being transferred onto the desired substrate. The graphene/PMMA film was allowed to dry on the substrate for approximately 1 hour. The PMMA layer was then removed by soaking the substrate in acetone for 1 hour, followed by rinsing the substrate in isopropanol (IPA) and drying with compressed N2.

4.3. GFET Fabrication

The GFET channels were defined using photolithography and plasma etching. First, a 50 nm protective layer polymethylglutarimide (PMGI, Microchem) resist was spin coated onto the graphene, followed by a 1.25 μm layer of positive photoresist S1813 (Microchem). Channel regions with dimensions 10 μm x 100 μm were defined, and the sample was developed in AZ300 (Microposit). To remove unwanted graphene regions, the chip was placed in a plasma etcher and etched with O2 for 30 seconds at 1.25 Torr and 60 W. The photoresist was then removed by soaking the chip in a bath of Remover NMP (Microposit) for 3minutes, a second NMP bath for 5 minutes, an acetone bath for 10 minutes, and an IPA bath for 3 minutes, after which the sample was blown dry with compressed N2. The GFET array was then annealed in an open tube furnace at 225 °C, with an Ar (99.999% purity) flow rate of 1000 sccm and a H2 (99.999% purity) flow rate of 250 sccm , for 1 hour.

4.4. GFET Functionalization

GFET arrays were soaked in a bath of 0.2 mM solution of P-BASE in N-N-dimethylformamide (DMF) for approximately 16 hours to ensure uniform coverage of P-BASE on the graphene surface. The chips were then removed from the PBASE-DMF bath and soaked in a series of DMF, IPA, and deionized water baths for 3 minutes each before being blown dry with compressed N2. The chips were then incubated with a 1 μM solution of aminated probe DNA for 3 hours, rinsed with deionized water, and blown dry with compressed N2. The probe molecules used were obtained commercially from ThermoFisher Scientific. Devices prepared following this protocol and stored in standard wafer containers have proven to be stable for periods of at least one week.

4.5. Synthetic HIV RNA

Synthetic sense and antisense HIV-1 RNA were generated in vitro from a near-full-length sequence of the NL4-3 strain 29. Briefly, an 8.5 kb region of the viral genome (lacking the LTRs) was amplified from linearized pNL4-3 plasmid using ThermoFisher High-Fidelity PCR kit and 5’ primer (5'-ATTACG TCTA GACTCGGCTT GCTGAAGCGC GCACGG-3') and 3' primer (5'- GGTGGT TCTAG AGTCATT GGTCTTAAAG GTACCTGAGG) (primer extension including restriction site indicated by underline). Fragments were digested with Xba1, cloned into pGEM-4Z (Promega), and two plasmids selected with the insert in both forward and reverse orientations relative to the T7 promoter. To generate sense or antisense RNA, the respective plasmid was linearized with Sma1 and subjected to in vitro transcription using the T7 RiboMAX transcript kit (Promega) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was column-purified (Zymo RNA clean & Concentrator-5), analyzed by gel electrophoresis, and quantified by nanodrop spectrophotometry.

4.6. Sensor Response Measurement in nuclease free Water

100 μL samples containing 100 fM to 1zM of HIV-1 RNA were created from serial dilutions of a stock at 1 pM concentration. 10 μL of each concentration of target HIV-1 RNA solution was pipetted onto each individual quadrant of the chip. The solution was left to incubate in a humid environment for an amount of time that was chosen to allow for diffusion of target molecules to the sensor surface, and found experimentally to give reproducible target binding (Supplemental Information). For the experiments using the 80mer probe, this time was 3 hours, and for experiments using 22mer probe this time was 30 minutes. Devices were then rinsed with deionized water, and blown dry with compressed N2.

4.7. Sensor Response Measurement in Qiazol Reagent:

The previously mentioned nuclease free water samples were further diluted to create100 μL samples of HIV-1 RNA serial diluted in Qiazol reagent to concentrations ranging from 1 fM to 1 zM. 10 μL of each concentration of Qiazol diluted HIV-1 RNA was pipetted onto each individual quadrant of the chip. The solution was left to incubate in a humid environment for 3 hours for 80mer probes and 30 minutes for 22mer probes. The devices were then aggressively rinsed for 10 seconds with a spray of deionized water, and blown dry with compressed N2.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Short oligonucleotide probes can be used to capture full length RNA molecules

Probe functionalized graphene field effect transistors are capable of detecting RNA at attomolar concentrations

Graphene field effect transistors can reliably detect RNA in both simple and complex solutions

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grants R61-AI140486 and R33-AI-147406-04. It also received support from the Penn Center for AIDS Research (NIH grant P30-AI045008), R33-AI133696 (RGC). This work was carried out in part at the Singh Center for Nanotechnology, which is supported by the NSF National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure Program under grant NNCI-2025608.

Biographies

Olivia O. Dickens is currently a Senior Associate Scientist in industry. She received her BS from Howard University and her PhD from the University of Pennsylvania. Her interests include biomolecule detection, education, and science outreach.

Inayat Bajwa is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania. She received her Bachelor of Technology degree in Biotechnology from Punjab Technical University, India. Her research interests include graphene biosensors, biosensor design and fabrication, and over the counter diagnostic tests.

Kelly Garcia-Ramos is an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania studying Neuroscience and Chinese East Asian Studies. They will be graduating in the Spring of 2024 with a Bachelor of the Arts in Neuroscience. Their current research interests include learning bioinformatics and creating biological models using a variety of coding languages and machine learning

Yeonjoon Suh is currently pursuing PhD in Electrical and Systems Engineering at University of Pennsylvania, and his current research focuses on the graphene biosensor and carbon nanotube gas sensor. He received his M.S. in Nanotechnology at University of Pennsylvania and B.S. in Food Biotechnology at Seoul National University, where he worked in the Graphene Research Laboratory.

Chengyu Wen is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Electrical and Systems Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania. He received his BS degree in Materials Science and Engineering from Xi'an Jiaotong University, China, in 2016 and MS degree in Materials Science and Engineering from University of Pennsylvania in 2018. His current research focuses on the synthesis of 2D materials and their applications.

Annie Cheng is an undergraduate student studying physics at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research interests lie in the intersection of 2D materials and nanophotonics.

Victoria Fethke is an accelerated master student in Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics and a fourth-year undergraduate in Physics at the University of Pennsylvania. Her research interests lie in nanotechnology and energy.

Yanjie Yi is a Senior Research Investigator at the University of Pennsylvania. He received his MD degree from Hunan Medical University in Changsha, China, followed by postdoctoral training at the Institute of Virology in Beijing, and the US National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, MD. He has studied the molecular virology of HIV-1 for the past 25 years.

Ronald Collman is Professor of Medicine and Microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine, and Director of the Penn Center for AIDS Research. He received his undergraduate and MD degrees from Boston University, and did clinical Critical Care Medicine and postdoctoral virology research training at the University of Pennsylvania. His research program focuses on molecular virology and viral pathogenesis of HIV as well as respiratory tract microbiome studies.

A T Charlie Johnson is the Rebecca W Bushnell Professor of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Pennsylvania. He received his PhD from Harvard University in 1990. His current research interests include nanosensor technology and topological phononics.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available: The supporting information contains droplet positioning for target incubation, the Raman spectrum of CVD grown graphene, current-gate voltage characteristics of the GFET devices, supplemental plots for Dirac voltage shift, and nucleic acid sequences for each of the probe molecules.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- (1).Gao Z; Kang H; Naylor CH; Streller F; Ducos P; Serrano MD; Ping J; Zauberman J; Rajesh; Carpick RW; et al. Scalable Production of Sensor Arrays Based on High-Mobility Hybrid Graphene Field Effect Transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8 (41), 27546–27552. DOI: 10.1021/acsami.6b09238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ping J; Vishnubhotla R; Vrudhula A; Johnson ATC Scalable Production of High-Sensitivity, Label-Free DNA Biosensors Based on Back-Gated Graphene Field Effect Transistors. ACS Nano 2016, 10 (9), 8700–8704. DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.6b04110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Vishnubhotla R; Sriram A; Dickens OO; Mandyam SV; Ping J; Adu-Beng E; Johnson ATC Attomolar Detection of ssDNA Without Amplification and Capture of Long Target Sequences With Graphene Biosensors. IEEE Sensors 2020, 20 (11), 5720 – 5724. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Schito ML; D'Souza MP; Owen SM; Busch MP Challenges for rapid molecular HIV diagnostics. J Infect Dis 2010, 201 Suppl 1, S1–6. DOI: 10.1086/650394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Drummond TG; Hill MG; Barton JK Electrochemical DNA sensors. Nat. Biotechnol 2003, 21, 1192. DOI: 10.1038/nbt873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Menon S; Mathew MR; Sam S; Keerthi K; Kumar KG Recent advances and challenges in electrochemical biosensors for emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. J Electroanal Chem (Lausanne) 2020, 878, 114596. DOI: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.114596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Saag MS; Holodniy M; Kuritzkes DR; O'Brien WA; Coombs R; Poscher ME; Jacobsen DM; Shaw GM; Richman DD; Volberding PA HIV viral load markers in clinical practice. Nat Med 1996, 2 (6), 625–629. From Nlm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Eisinger RW; Dieffenbach CW; Fauci AS HIV Viral Load and Transmissibility of HIV Infection: Undetectable Equals Untransmittable. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2019, 321 (5), 451–452. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2018.21167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Cohen MS; Chen YQ; McCauley M; Gamble T; Hosseinipour MC; Kumarasamy N; Hakim JG; Kumwenda J; Grinsztejn B; Pilotto JH; et al. Antiretroviral Therapy for the Prevention of HIV-1 Transmission. N Engl J Med 2016, 375 (9), 830–839. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Davenport MP; Khoury DS; Cromer D; Lewin SR; Kelleher AD; Kent SJ Functional cure of HIV: the scale of the challenge. Nat Rev Immunol 2019, 19 (1), 45–54. DOI: 10.1038/s41577-018-0085-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Read JS; Committee on Pediatric Aids, A. A. o. P. Diagnosis of HIV-1 infection in children younger than 18 months in the United States. Pediatrics 2007, 120 (6), e1547–1562. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2007-2951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Luft LM; Gill MJ; Church DL HIV-1 viral diversity and its implications for viral load testing: review of current platforms. Int J Infect Dis 2011, 15 (10), e661–670. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijid.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lin Z; Wu G; Zhao L; Lai KWC Carbon nanomaterial-based biosensors: a review of design and applications. IEEE Nanotechnology Magazine 2019, 13, 4–14. DOI: 10.1109/MNANO.2019.2927774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hwang MT; Wang Z; Ping J; Ban DK; Shiah ZC; Antonschmidt L; Lee J; Liu Y; Karkisaval AG; Johnson ATC; et al. DNA nanotweezers and graphene transistor enable label-free genotyping. Adv Mater 2018, 30, 1802440. DOI: 10.1002/adma.201802440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Campos R; Borme J; Guerreiro JR; Machado G Jr.; Cerqueria MF; Petrovykh DY; Alpuim P Attomolar label-free detection of DNA hybridization with electrolyte-gated graphene field-effect transistors. ACS Sensors 2019, 4, 286–293. DOI: 10.1021/acssensors.8b00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Hwang MT; Heiranian M; Kim Y; You S; Leem J; Taqieddin A; Faramarzi V; Jing Y; Park I; van der Zande AM; et al. Ultrasensitive detection of nucleic acids usng deformed graphene channel field effect biosensors. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1543. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-15330-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Palmer S; Maldarelli F; Wiegand A; Bernstein B; Hanna GJ; Brun SC; Kempf DJ; Mellors JW; Coffin JM; King MS Low-level viremia persists for at least 7 years in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105 (10), 3879–3884. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0800050105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Cobb BR; Vaks JE; Do T; Vilchez RA Evolution in the sensitivity of quantitative HIV-1 viral load tests. J Clin Virol 2011, 52 Suppl 1, S77–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Calmy A; Ford N; Hirschel B; Reynolds SJ; Lynen L; Goemaere E; Garcia de la Vega F; Perrin L; Rodriguez W HIV viral load monitoring in resource-limited regions: optional or necessary? Clin Infect Dis 2007, 44 (1), 128–134. DOI: 10.1086/510073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).De Scheerder MA; Vrancken B; Dellicour S; Schlub T; Lee E; Shao W; Rutsaert S; Verhofstede C; Kerre T; Malfait T; et al. HIV Rebound Is Predominantly Fueled by Genetically Identical Viral Expansions from Diverse Reservoirs. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26 (3), 347–358 e347. DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).CHen J-H; Jang C; Adam S; Fuhrer MS; Williams ED; Ishigami M Charged-impurity scattering in graphene. Nat. Phys 2008, 4, 377–381. DOI: doi: 10.1038/nphys935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Gao Z; Xia H; Zauberman J; Tomaiuolo M; Ping J; Zhang Q; Ducos P; Ye H; Wang S; Yang X; et al. Detection of Sub-fM DNA with Target Recycling and Self-Assembly Amplification on Graphene Field-Effect Biosensors. Nano Lett 2018, 18 (6), 3509–3515. DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Yang OO Candidate vaccine sequences to represent intra- and inter-clade HIV-1 variation. PLoS One 2009, 4 (10), e7388. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Rolland M; Nickle DC; Mullins JI HIV-1 group M conserved elements vaccine. PLoS Pathog 2007, 3 (11), e157. DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Cillo AR; Vagratian D; Bedison MA; Anderson EM; Kearney MF; Fyne E; Koontz D; Coffin JM; Piatak M Jr.; Mellors JW Improved single-copy assays for quantification of persistent HIV-1 viremia in patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Microbiol 2014, 52 (11), 3944–3951. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.02060-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Letourneau S; Im EJ; Mashishi T; Brereton C; Bridgeman A; Yang H; Dorrell L; Dong T; Korber B; McMichael AJ; et al. Design and pre-clinical evaluation of a universal HIV-1 vaccine. PLoS One 2007, 2 (10), e984. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lerner MB; Resczenski JM; Amin A; Johnson RR; Goldsmith JI; Johnson AT Toward quantifying the electrostatic transduction mechanism in carbon nanotube molecular sensors. J Am Chem Soc 2012, 134 (35), 14318–14321. DOI: 10.1021/ja306363v From NLM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Landry S; Halin M; Lefort S; Audet B; Vaquero C; Mesnard JM; Barbeau B Detection, characterization and regulation of antisense transcripts in HIV-1. Retrovirology 2007, 4, 71. DOI: 10.1186/1742-4690-4-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Adachi A; Gendelman HE; Koenig S; Folks T; Willey R; Rabson A; Martin MA Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol 1986, 59 (2), 284–291. DOI: 10.1128/JVI.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.