Abstract

Exposure to traumatic events during pregnancy may influence pregnancy and birth outcomes. Growing evidence suggests that exposure to traumatic events well before pregnancy, such as childhood maltreatment (CM), also may influence the course of pregnancy and risk of adverse birth outcomes. We aimed to estimate associations between maternal CM exposure and small-for-gestational-age birth (SGA) and preterm birth (PTB) in a diverse US sample, and to examine whether common CM-associated health and behavioral sequelae either moderate or mediate these associations. The Measurement of Maternal Stress (MOMS) Study was a prospective cohort study that enrolled 744 healthy English-speaking participants ≥ 18 years with a singleton pregnancy, who were < 21 weeks at enrollment, between 2013 and 2015. CM was measured via the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) and participants above the moderate/severe cut-off for any of the five childhood abuse and neglect scales were assigned to the CM-exposed group. Common CM-associated health (obesity, depressive symptoms, hypertensive disorders) and behavioral (substance use) sequelae were obtained from standardized questionnaires and medical records. The main outcomes included PTB (gestational age < 37 weeks at birth) and SGA (birthweight < 10%ile for gestational age) abstracted from the medical record. Multivariable logisitic regression was used to test associations between CM, sequeale, and birth outcomes, and both moderation and mediation by CM-related sequelae were tested. Data were available for 657/744 participants. Any CM exposure was reported by 32% of participants. Risk for SGA birth was 61% higher among those in the CM group compared to the non-CM group (14.1% vs. 7.6%), and each subsequent form of CM that an individual was exposed to corresponded with a 27% increased risk for SGA (aOR 1.27, 95% CI 1.05, 1.53). There was no significant association between CM and PTB (9.3% vs. 13.0%, aOR 1.07, 95% CI 0.58, 1.97). Of these sequelae only hypertensive disorders were associated with both CM and SGA and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy did not mediate the association between CM and SGA. Our findings indicate that maternal CM exposure is associated with increased risk for SGA birth and highlight the importance of investigating the mechanisms whereby childhood adversity sets the trajectory for long-term and intergenerational health issues.

Subject terms: Neuroscience, Psychology, Medical research, Risk factors

Introduction

The effects of exposure to excess stress on health are well established, and are known to be particularly pronounced when exposure occurs during sensitive developmental windows in early life. Exposure to childhood maltreatment (CM, defined as adverse experiences that occur in childhood such as physical, sexual, emotional childhood abuse, or physicial or emotional neglect) represents among the most pervasive and potent stressors in early life1. Population-based surveys in the United States suggest that a considerable proportion of children experience maltreatment, with about 12% reporting abuse or neglect within the past year2,3. Globally, lifetime prevalence of CM varies between 8 and 35% depending on maltreatment type and gender4.

Individuals exposed to CM exhibit elevated risk for adverse health outcomes during the lifecourse, including cardiovascular, metabolic, and mental disease5–9. This notion is based on the concept of developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD), which postulates that environmental influences such as adversity during sensitive periods of development, when organs are characterized by a high degree of plasticity, can lead to profound and persistent changes in the developing brain and other regulatory systems with significant consequences for an individual’s short- and long-term health10,11. Growing evidence from this literature suggests that the effects of CM, particularly among childbearing persons who subsequently become pregnant, may influence the course of their pregnancy, birth and child health outcomes11–13. To date, birth outcomes studied in association with CM mainly have focused on length of gestation, demonstrating greater risk of preterm delivery among those exposed to CM1–3. There has been less attention on fetal growth restriction, which also poses significant long-term health risks including obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease4. Three prior studies have found decreased fetal growth in pregnant individuals with a history of CM14–16. However, two of these15,16 studies were conducted in small, high-risk cohorts, and none of the three studies account for gestational age at delivery in estimating adjusted birth weight percentiles, thereby calling into question whether the observed associations were specific to fetal growth restriction.

Depression17–19, substance abuse20–22, obesity23,24, and hypertension25–27 are common CM-associated sequelae that increase risk for adverse birth outcomes28–32 and may thus mediate the association of CM with preterm birth and SGA. It is also possible that these sequelae may moderate these associations because CM-associated variation in maternal-placental-fetal stress biology has been shown to be especially pronounced in the presence of such sequelae11,33.

The purpose of this study was three-fold: we aimed to (1) replicate previous reports of associations between maternal CM exposure and adverse birth outcomes (growth restriction and preterm delivery) in a large, representative US sample, (2) examine whether common CM-associated sequelae (depression, substance use, obesity, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy) mediate the association between CM and adverse birth outcomes, and (3) characterize the potential moderating role of these CM-associated sequelae in the association between CM and birth outcomes.

Methods

Study sample

This study uses data from the Measurement of Maternal Stress (MOMS) Study, in which we prospectively enrolled 744 participants from prenatal clinics at four geographically- and racially-diverse US regions (Pittsburgh, PA, Chicago IL, Schuylkill County PA, and San Antonio TX) between June 2013 and May 201534–37. Recruitment was designed to be representative of the sample populations and was powered to examine differences in preterm delivery assuming a rate of 10%. The study included English-speaking participants 18 years and older with a singleton intrauterine pregnancy who were less than 21 weeks pregnant at time of enrollment. Individuals were excluded from participation if they had a known major fetal congenital or chromosomal abnormality, progesterone treatment > 14 weeks of gestation, or chronic corticosteroid treatment (not including inhalers or topical). Institutional Review Boards at each site approved the protocol (Overall IRB Northwestern University #STU00039484 approved 2/13/14), and all participants provided informed consent. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Procedure

Participants completed questionnaires and self-reported sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics in the second (16.5 ± 2.5 weeks’ gestation) and third (33.7 ± 1.2 weeks’ gestation) trimesters. Pregnancy and clinical outcomes were abstracted from the medical record by trained staff.

Key variables

Preterm birth (PTB) delivery at < 37 weeks of gestation, calculated from last menstrual period and verified by ultrasound dating, indicated in both the birth parental and neonatal medical record.

Small for Gestational Age (SGA). Infant birthweight, as recorded in the medical record, measuring < 10th percentile for gestational age at birth. Percentile rankings were sex-specific, based on national norms38,39.

Childhood Maltreatment (CM) was assessed with the Childhood Trauma Quesitonnaire (CTQ), a widely used instrument to characterize the extent and nature of exposure to abuse and/or neglect before the age of 1840. The CTQ measures exposure across five domains: physical abuse; physical neglect; emotional abuse; emotional neglect; and sexual abuse. For each domain, exposure is measured based on responses to five questions with a five-point Likert scale; the total scores within each domain can range from 5 to 25. Standardized cut-off scores can be used to classify exposure levels as being either “none to minimal”, “low to moderate”, “moderate to severe”, or “severe to extreme.” As applied in previous work that utilized the CTQ to classify CM exposure in pregnant individuals and reported associated variation in maternal-placental stress biology relevant for birth outcomes33,41, exposure to each domain of CM was defined as the basis of scores indicative of at least “moderate to severe” abuse or neglect. Recognizing that CM varies in type and severity and that these factors may have differential impact upon pregnancy outcomes, we defined CM exposure in 3 ways. First, to characterize overall exposure to any CM, we examined any CM as a binary variable that assigned individuals to the CM group (reference group) if their sum score was 0, and to the CM+ group if the score was > = 1 (i.e., comparing individuals with less than “moderate to severe” CM to those with at least “moderate to severe” experiences in one or more of the 5 domains). Second, we evaluated exposure to each of the 5 domains of CM separately with the same “moderate to severe” cut off. Finally, recognizing that these individual domains are highly correlated, we assessed cumulative CM, defined as the sum of the number of domains at or above the “moderate to severe” cutoff (range of 0–5), as our exposure variable.

Covariates: The analyses included covariates that might provide alternative explanations for an observed association between CM and either SGA or PTB. Age in pregnancy has a bi-modal association with risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes42, and was categorized as ≤ 20, 21–34, and ≥ 35 years. Prevalence of CM as well as adverse pregnancy outcomes are more frequent among Black and Hispanic/Latine individuals43, so we assessed ethnicity and race as White, Black, Hispanic/Latine, and ‘Other’. Because in the US CM44, PTB45, and SGA46 are more prevalent in families of low socioeconomic status, we included measures of both childhood socioeconomic status and current socioeconomic status: Childhood poverty, indicating whether the participant’s family received public assistance before the participant’s 18th birthday; and current educational attainment, which is highly correlated with adult income and was coded as high school or less, some college or associates, and bachelor’s degree or more.

CM-associated sequelae as potential mediators or moderators: Potential mediators/moderators included variables from 4 categories that have been reported as common health and behavioral CM sequelae. Mental health was indexed by presence of depressive symptoms in mid pregnancy based on a score of 16 or greater on the CES-D, a widely used tool designed to evaluate depressive symptomatology32,47,48. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy included gestational hypertension, pre-eclampsia, or eclampsia diagnosed during pregnancy and documented in the medical record25,49. Any substance use during pregnancy was defined as any alcohol consumption, recreational drug use (marijuana, cocaine, heroin), or smoking since becoming pregnant. (4) Metabolic risk was indexed by an individual’s pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), categorized as underweight (< 18.5), normal weight (18.5 to < 25), or overweight/obese (≥ 25)50.

Statistical analysis

The associations between the three CM exposure variables and birth outcomes (SGA, PTB) were examined via multivariable logistic regression in separate models, which included ethnicity/race, age, education, and childhood poverty as covariates. Analyses were not adjusted for any of the above-listed CM-associated sequelae because these may be on the potential causal pathway.

Moderation analyses, adjusting for the same covariates listed above, were conducted to evaluate whether CM-associated sequelae modified risk for adverse birth outcomes. For these analyses an interaction term was created between the cumulative CM exposure score, as it best captures variation in CM severity, and each of the 4 potential CM-related sequelae which was included in multiple regression models. Because the moderating influence of the different sequelae may increase if several sequelae are present, we also created a total sequelae score by assigning one point for each CM-associated sequela reported by the participant (range 0–4) and used it in the moderation analyses.

For those CM-associated sequelae that were significantly associated with both CM and SGA or CM and PTB, their mediating effect was tested using PROC CAUSALMED in SAS, which uses a counterfactual approach for mediation analysis51,52. Each mediator was considered separately and models were adjusted for ethnicity/race, childhood poverty, age, education, and the other CM-associated sequelae not evaluated as mediators. As CM exposure was evaluated in three different ways (any, cumulative, and domains), a Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple testing and a p-value of 0.0167 (0.05/3) was used to determine statistical significance. Analyses were conducted using SAS Software Version 9.4.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Review Boards at each site approved the protocol (Overall IRB Northwestern University #STU00039484 approved 2/13/14), and all participants provided consent.

Results

CM and delivery data were available for 657 of the 744 MOMS study participants. The sociodemographic characteristics of these 657 participants were not significantly different from those in the full cohort (Table 1). The distribution of key study variables and the crude associations between key variables and birth outcomes are summarized in Table 2. 14.6% of study participants reported one form of moderate-to-severe CM, 6.1% reported 2, 6.1% reported 3, 3.0% reported 4, and 1.7% reported all 5 forms of CM. In total, 31.5% reported at least one form of moderate-to-severe CM, which is consistent with the estimated prevalence of CM in the US53. The most commonly-reported forms of CM included sexual abuse (18.4%), emotional abuse (16.1%), and physical abuse (13.1%), followed by emotional neglect (9.7%) and physical neglect (8.2%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included versus excluded participants.

| Total 744 |

Excluded 87 |

Included 657 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.21 | |||

| < 20 | 41 (5.5) | 7 (8.0) | 34 (5.2) | |

| 20–29 | 578 (77.7) | 71 (80.5) | 508 (77.3) | |

| 30–39 | 103 (13.8) | 10 (11.5) | 93 (14.2) | |

| 40+ | 22 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 22 (3.3) | |

| Income (76 missing overall) | 0.23 | |||

| ≤ $15,000 | 108 (14.5) | 17 (19.5) | 91 (13.9) | |

| $15,000–50,000 | 221 (29.7) | 19 (21.8) | 202 (30.7) | |

| ≥ $50,000 | 339 (45.6) | 39 (44.8) | 300 (45.7) | |

| Missing | 76 (10.2) | 13 (14.9) | 63 (9.6) | |

| Race and ethnicity | 0.07 | |||

| Black | 127 (17.1) | 19 (21.8) | 108 (16.4) | |

| White | 429 (57.7) | 40 (46.0) | 389 (59.2) | |

| Hispanic | 145 (19.5) | 22 (25.3) | 123 (18.7) | |

| Other | 43 (5.8) | 6 (6.9) | 37 (5.6) | |

| Married | 601 (81.1) | 72 (84.7) | 529 (80.6) | 0.37 |

| Education | 0.94 | |||

| High school or less | 198 (26.7) | 24 (28.2) | 174 (26.5) | |

| Some college or associates | 254 (34.3) | 29 (34.1) | 225 (34.3) | |

| Bachelors degree or more | 298 (39.0) | 32 (37.6) | 257 (39.2) | |

| CESD score | 13.7 ± 10.6 | 15.5 ± 10.1 | 13.5 ± 10.6 | 0.12 |

| CTQ score | 37.8 ± 14.6 | 39.2 ± 18.1 | 37.6 ± 14.2 | 0.39 |

| Smoking in pregnancy | 76 (10.0) | 6 (6.9) | 70 (10.7) | 0.28 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 27.8 ± 7.4 | 27.7 ± 7.3 | 27.9 ± 7.6 | 0.84 |

Table 2.

Sample characteristics by birth outcomes and any Childhood Maltreatment (CM) exposure.

| Total | non-SGA | SGA | p-value | Term birth (non-PTB) | Preterm birth (PTB) | p-value | No CM reported | CM reported | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 657 | 594 | 63 | 603 | 54 | 450 | 207 | ||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Sex of the baby | 0.18 | 0.35 | 0.77 | |||||||

| Female | 307 (46.8) | 272 (45.9) | 35 (54.7) | 285 (47.2) | 22 (42.3) | 212 (47.1) | 95 (45.9) | |||

| Male | 350 (53.4) | 320 (54.1) | 29 (45.3) | 318 (52.6) | 32 (61.5) | 238 (52.9) | 112 (54.1) | |||

| Maternal age (years) | 0.39 | 0.98 | 0.25 | |||||||

| ≤ 20 | 32 (4.9) | 29 (4.9) | 3 (4.8) | 30 (5.0) | 2 (3.7) | 17 (3.8) | 15 (7.3) | |||

| 21–29 | 334 (50.8) | 306 (51.5) | 28 (44.4) | 306 (50.8) | 28 (51.9) | 228 (50.7) | 106 (51.2) | |||

| 30–39 | 269 (40.9) | 241 (40.6) | 28 (44.4) | 247 (41.0) | 22 (40.7) | 190 (42.2) | 79 (38.2) | |||

| ≥ 40 | 22 (3.4) | 18 (3) | 4 (6.4) | 20 (3.3) | 2 (3.7) | 15 (3.3) | 7 (3.4) | |||

| Income (63 missing) | 0.99 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| ≤ $15,000 | 89 (15) | 81 (15.1) | 8 (14.3) | 70 (12.9) | 19 (35.2) | 45 (11.0) | 44 (23.9) | |||

| $15,000–50,000 | 200 (33.7) | 181 (33.6) | 19 (33.9) | 189 (34.7) | 11 (20.4) | 133 (32.4) | 67 (36.4) | |||

| ≥ $50,000 | 305 (51.3) | 276 (51.3) | 29 (51.8) | 285 (52.4) | 20 (37.0) | 232 (56.6) | 73 (39.7) | |||

| Race/ethnicity | 0.45 | < 0.01 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| Non-Latine White | 391 (59.7) | 359 (60.6) | 32 (50.8) | 372 (61.9) | 19 (35.2) | 295 (65.7) | 96 (46.6) | |||

| Non-Latine Black | 104 (15.9) | 93 (15.7) | 11 (17.5) | 90 (15) | 14 (25.9) | 64 (14.2) | 40 (19.4) | |||

| Hispanic/Latine | 123 (18.8) | 107 (18.1) | 16 (25.4) | 109 (18.1) | 14 (25.9) | 61 (13.6) | 62 (30.1) | |||

| Other | 37 (5.7) | 33 (5.6) | 4 (6.4) | 30 (5) | 7 (13.0) | 29 (6.5) | 8 (3.9) | |||

| Married | 536 (81.7) | 483 (81.5) | 53 (84.1) | 0.6 | 495 (82.2) | 41 (75.9) | 0.25 | 376 (83.7) | 160 (77.3) | 0.05 |

| Education | 0.72 | 0.35 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| High school or less | 169 (25.7) | 150 (25.3) | 19 (30.2) | 150 (24.9) | 19 (35.2) | 95 (21.1) | 74 (35.7) | |||

| Some college or associates | 222 (33.8) | 201 (33.8) | 21 (33.3) | 204 (33.8) | 18 (33.3) | 142 (31.6) | 80 (38.6) | |||

| Bachelors degree or more | 265 (40.4) | 242 (40.7) | 23 (36.5) | 248 (41.1) | 17 (31.5) | 213 (47.3) | 52 (25.1) | |||

| Childhood poverty | 249 (37.9) | 212 (35.7) | 37 (58.7) | < 0.01 | 223 (37.0) | 26 (48.1) | 0.11 | 135 (30.0) | 114 (55.1) | < 0.01 |

| Depression (CES-D ≥ 16) | 209 (31.8) | 184 (31) | 25 (39.7) | 0.16 | 191 (31.7) | 18 (33.3) | 0.8 | 109 (24.2) | 100 (48.3) | < 0.01 |

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) | 88 (13.4) | 70 (11.8) | 18 (28.1) | < 0.01 | 69 (11.4) | 19 (35.2) | < 0.01 | 52 (11.6) | 36 (17.4) | 0.04 |

| Alcohol use in pregnancy | 55 (8.2) | 48 (8.1) | 7 (12.5) | 0.63 | 50 (8.4) | 5 (5.8) | 0.88 | 38 (8.4) | 15 (7.3) | 0.62 |

| Smoking in pregnancy | 70 (10.5) | 59 (9.9) | 11 (17.4) | 0.07 | 62 (10.4) | 8 (11.5) | 0.3 | 40 (8.9) | 30 (14.5) | 0.03 |

| Recreational drug use in pregnancy | 16 (2.5) | 15 (2.5) | 1 (1.6) | 0.64 | 14 (2.3) | 2 (3.8) | 0.51 | 5 (1.1) | 11 (5.3) | < 0.01 |

| Any substance use | 123 (18.7) | 106 (17.9) | 17 (27.0) | 0.08 | 111 (18.4) | 12 (22.2) | 0.49 | 79 (17.6) | 44 (21.3) | 0.26 |

| Body mass index BMI (kg/m2) | 0.76 | 0.02 | < 0.01 | |||||||

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 13 (2) | 11 (1.9) | 2 (3.2) | 10 (1.7) | 3 (5.6) | 9 (2.0) | 4 (1.9) | |||

| Normal weight (18.5–24.9) | 287 (43.9) | 260 (43.9) | 27 (43.6) | 271 (45.2) | 16 (29.6) | 216 (48.2) | 71 (34.5) | |||

| Overweight/obese (≥ 25.0) | 354 (54.1) | 321 (54.2) | 33 (53.2) | 319 (53.2) | 35 (64.8) | 223 (49.8) | 131 (63.6) | |||

| Childhood Maltreatment (CM) | ||||||||||

| Physical neglect | 54 (8.2) | 42 (7.1) | 12 (19.1) | < 0.01 | 47 (7.8) | 7 (13.0) | 0.19 | |||

| Physical abuse | 86 (13.1) | 72 (12.1) | 14 (22.2) | 0.02 | 77 (12.8) | 9 (16.7) | 0.42 | |||

| Emotional neglect | 64 (9.7) | 53 (8.9) | 11 (17.5) | 0.03 | 57 (9.5) | 7 (13.0) | 0.41 | |||

| Emotional abuse | 106 (16.1) | 89 (15) | 17 (27.0) | 0.01 | 97 (16.1) | 9 (16.7) | 0.92 | |||

| Sexual abuse | 121 (18.4) | 102 (17.2) | 19 (30.2) | 0.01 | 109 (18.1) | 12 (22.2) | 0.45 | |||

| Number of Childhool Maltreatment (CM) sub-scales moderate/severe | < 0.01 | 0.44 | ||||||||

| 0 | 450 (68.5) | 416 (70) | 34 (54.0) | 416 (69) | 34 (63) | |||||

| 1 | 96 (14.6) | 85 (14.3) | 11 (17.5) | 87 (14.4) | 9 (16.7) | |||||

| 2 | 40 (6.1) | 36 (6.1) | 4 (6.4) | 36 (6.0) | 4 (7.4) | |||||

| 3 | 40 (6.1) | 34 (5.7) | 6 (9.5) | 38 (6.3) | 2 (3.7) | |||||

| 4 | 20 (3) | 16 (2.7) | 4 6.4) | 16 (2.7) | 4 (7.4) | |||||

| 5 | 11 (1.7) | 7 (1.2) | 4 (6.4) | 10 (1.7) | 1 (1.9) | |||||

| Adverse birth outcomes | ||||||||||

| Small for getational age (SGA) | 63 (9.6) | 56 (9.3) | 7 (13.0) | 0.38 | 34 (7.6) | 29 (14.1) | < 0.01 | |||

| Preterm birth (PTB) | 54 (8.2) | 47 (7.9) | 7 (11.1) | 0.38 | 34 (7.6) | 20 (9.7) | 0.36 | |||

Participants with any history of CM were more likely to have experienced childhood poverty and to have lower educational attainment and income compared to those without exposure to CM. These participants were also more likely to be overweight or obese, use recreational drugs during pregnancy, smoke cigarettes, report symptoms of depression, and develop hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (Table 2).

Sixty three participants (9.6%) delivered SGA infants. Participants who delivered an SGA infant were more than twice as likely to have developed hypertensive disorders during the index pregnancy, and were more likely to have experienced childhood poverty compared to those who did not deliver SGA (Table 2).

Fifty-four participants (8.2%) had a PTB. PTB was more prevalent among participants who were from low-income households (< $15 k/year), identified as Non-Latine Black, had a diagnosis of HDP, and were overweight/obese (Table 2).

Maternal childhood maltreatment and offspring preterm birth

Having any maternal CM exposure was not associated with PTB in the current study. The PTB rate among participants with CM was 9.7% compared to 7.6% for participants without CM, and this difference was not statistically significant in either crude or adjusted analyses (OR 1.31, 95% CI 0.73, 2.33/aOR 1.07, 95% CI 0.58, 1.97). When using the different types of CM or cumulative CM as a predictor, there was also no significant association with PTB (Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression results: relationship between small-for-gestational age (SGA) or preterm birth (PTB) and childhood maltreatment (CM).

| Small for gestational age (SGA) | Preterm birth (PTB) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

p-value | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) |

p-value | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) |

p-value | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) |

p-value | |

| Any childhood maltreatment | 1.99 (1.18, 3.37) | 0.010 | 1.61 (0.92, 2.82) | 0.097 | 1.31 (0.73, 2.33) | 0.362 | 1.07 (0.58, 1.97) | 0.841 |

| Sum of childhood maltreatment types | ||||||||

| Each additional childhood maltreatment scale moderate/severe | 1.36 (1.14, 1.62) | < 0.001 | 1.27 (1.05, 1.53) | 0.016 | 1.12 (0.90, 1.38) | 0.308 | 1.02 (0.82, 1.29) | 0.841 |

| Type of childhood maltreatment | ||||||||

| Physical neglect | 3.09 (1.53, 6.25) | 0.002 | 2.35 (1.12, 4.90) | 0.023 | 1.76 (0.76, 4.11) | 0.191 | 1.28 (0.53, 3.11) | 0.588 |

| Physical abuse | 2.07 (1.09, 3.94) | 0.026 | 1.67 (0.85, 3.31) | 0.138 | 1.37 (0.64, 2.91) | 0.417 | 1.06 (0.48, 2.32) | 0.894 |

| Emotional neglect | 2.16 (1.06, 4.39) | 0.033 | 1.62 (0.77, 3.41) | 0.208 | 1.43 (0.62, 3.30) | 0.407 | 1.16 (0.48, 2.79) | 0.748 |

| Emotional abuse | 2.10 (1.15, 3.82) | 0.016 | 1.76 (0.94, 3.30) | 0.078 | 1.04 (0.49, 2.20) | 0.912 | 0.91 (0.42, 1.98) | 0.814 |

| Sexual abuse | 2.08 (1.17, 3.72) | 0.013 | 1.74 (0.94, 3.21) | 0.078 | 1.30 (0.66, 2.54) | 0.452 | 1.02 (0.50, 2.08) | 0.951 |

aAdjusted for covariates: maternal ethnicity/race, maternal age, education, and childhood poverty.

Maternal childhood maltreatment and small for gestational age infant

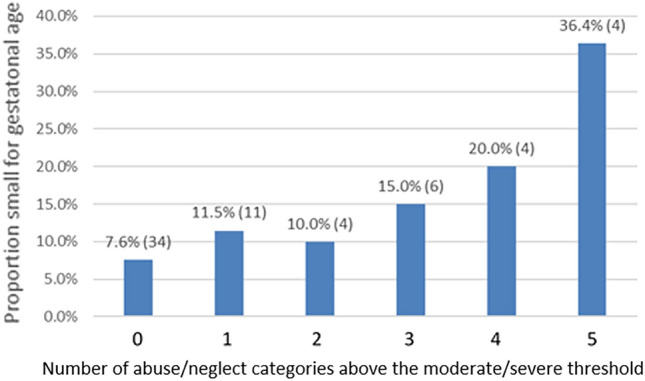

The prevalence of SGA birth among individuals with any CM was 14.1%, compared to 7.6% among the non-CM group (OR 1.99, 95% CI 1.18, 3.37/aOR 1.61, 95% CI 0.92, 2.82, Table 2). Each of the 5 domains of CM were significantly associated with increased odds of SGA delivery (see Table 2) and cumulative CM exposure was also significantly associated with SGA in both crude and adjusted analyses (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.14, 1.62/aOR 1.27, 95% CI 1.05, 1.53) (Table 3), even after accounting for multiple testing. In general, as the number of CM domains increased, the proportion of SGA births increased (Fig. 1). When models were adjusted for race/ethnicity, age at delivery, education, and childhood poverty, each subsequent domain of moderate or severe CM endorsed by a participant was associated with a 27% increased likelihood of delivering an SGA infant, compared to subjects who did not report any severe/moderate CM (aOR 1.27, 95% CI 1.05, 1.53) (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Proportion of small for gestational age (SGA) births by the number of abuse/neglect categories above the moderate/severe threshold.

CM-associated sequelae as potential moderators of the association between maternal childhood maltreatment and birth outcomes

As depicted in Table 4 none of the 4 CM-associated sequelae or the sequelae sum score moderated the association between CM and SGA, nor that between CM and PTB.

Table 4.

Results for models of depression, gestational hypertensive disorders, substance abuse, and obesity as moderators of the association between childhood maltreatment (sum score of moderate/severe domains) and adverse outcomes.

| Small for gestational age (SGA) | Preterm birth (PTB) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | Interaction p-value | OR | 95% CI | Interaction p-value | OR | 95% CI | Interaction p-value | OR | 95% CI | Interaction p-value | |

| Maternal depression risk | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.51 | ||||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.24 | 0.95, 1.61 | 1.14 | 0.87, 1.50 | 1.02 | 0.74, 1.42 | 0.95 | 0.68, 1.33 | ||||

| No depressive symptoms | 1.45 | 1.13, 1.86 | 1.37 | 1.05, 1.78 | 1.21 | 0.90, 1.62 | 1.11 | 0.82, 1.51 | ||||

| Obstetric risk | 0.22 | 0.26 | 0.62 | 0.65 | ||||||||

| Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) | 1.56 | 1.12, 2.18 | 1.47 | 1.03, 2.09 | 0.99 | 0.69, 1.41 | 0.92 | 0.63, 1.35 | ||||

| No hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) | 1.22 | 0.97, 1.53 | 1.15 | 0.91, 1.46 | 1.11 | 0.81, 1.45 | 1.03 | 0.77, 1.37 | ||||

| Substance use | 0.79 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.91 | ||||||||

| Any substance use | 1.30 | 0.92, 1.81 | 1.15 | 0.80, 1.66 | 1.23 | 0.83, 1.84 | 1.04 | 0.67, 1.59 | ||||

| No substance use | 1.37 | 1.11, 1.68 | 1.29 | 1.04, 1.61 | 1.07 | 0.83, 1.38 | 1.01 | 0.77, 1.31 | ||||

| Obesity | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.56 | ||||||||

| Overweight (BMIb ≥ 25) | 1.38 | 1.11, 1.72 | 1.29 | 1.03, 1.62 | 1.04 | 0.81, 1.34 | 0.99 | 0.76, 1.27 | ||||

| Normal weight/underweight (BMIb < 25) | 1.26 | 0.87, 1.82 | 1.11 | 0.75, 1.64 | 1.26 | 0.81, 1.95 | 1.16 | 0.72, 1.86 | ||||

aModels adjusted for ethnicity/race, maternal age, education, childhood poverty. bBMI = Body Mass Index weight/height2.

CM-associated sequelae as potential mediators of the association between CM and SGA

Of the CM-associated sequelae, only hypertensive disorders was significantly associated with CM and SGA (Table 2) and was therefore tested as a potential mediator. As shown in Table 5, hypertensive disorders did not significantly mediate the relationship between CM and SGA.

Table 5.

Results for models gestational hypertensive disorders as a mediator of the association between childhood trauma (score of moderate/severe domains) and small for gestational age birth (SGA).

| Total effect OR (95% C.I.) |

Direct effect OR (95% C.I.) |

Indirect effect | % Mediated (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator of interest | ||||

| Hypertensiona | 1.21 (0.95, 1.47) | 1.18 (0.93, 1.43) | 1.03 (0.99, 1.07) | 14.7 (− 5.9, 35.3) |

aModel adjusted for ethnicity/race, maternal age, BMI, education, childhood poverty, substance use, and depression.

Discussion

The present results replicate the previously-observed association between CM and risk of an SGA birth, and indicate that CM is associated with a 61% overall increased risk of SGA. CM may be a significant clinical risk factor for SGA birth, as the association was comparable to that of established risk factors54 including older age in pregnancy (aOR 1.455), hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (RR 1.0–4.856), nulliparity (aOR 1.3–2.157), and smoking during pregnancy (aOR 2.4157). Additionally, we demonstrated a dose–response association between number of abuse/neglect categories experienced during childhood and likelihood of an SGA delivery, with the risk of SGA birth increasing by 27% for every additional form of severe/moderate abuse/neglect category reported. The prevalence of CM in our sample was consistent with US epidemiological data53, though we found higher rates of sexual abuse and lower rates of neglect in this sample than expected. The 8.1% of PTB rate in this study was slightly lower than the national average for that same period (9.6%), and the 9.6% SGA rate was similar to that of the US overall (10%)58. In this healthy sample that was not enriched for CM exposure, elevated risk for SGA did not appear to stem from depression, substance use, obesity, or hypertension associated with CM exposure. We were unable to replicate a significant association between CM and PTB which has been demonstrated, albeit inconsistently, in prior studies13,59. Unlike those studies, the MOMS cohort was inherently at lower risk for PTB due to the exclusion of individuals on progesterone treatment for prior preterm birth, so this may in part explain our findings.

These findings extend the literature in a number of ways. First, we replicated CM and growth associations previously detected in small relatively disadvantaged cohorts15,16 in a large US sampleStevens-Simon and McAnarney 1994 included 127 low-income Black adolescent individuals from Rochester NY16, and Gavin et al. 2011 examined a cohort of 136 deliveries from Seattle, WA with greater than 50% childhood and adult poverty rates15.

Second, while SGA and PTB incidence overlap, our results suggest that CM may impact fetal growth and length of gestation differentially. Only three prior studies have investigated fetal growth as an outcome, and these studies examined low birthweight but not growth percentile14–16, which does not identify growth abnormalities per se, since it combines consequences of PTB with those of growth restriction. By differentiating growth effects from length of gestation in our outcomes variables, our analysis indicates that these outcomes may result from different pathways.

Third, our results suggest a CM and SGA association independent of CM-related sequelae. In concordance with previous studies we observed that depression, substance use, obesity, and gestational hypertensive disorders were significantly more common among individuals exposed to any form of CM, compared to those with no CM exposure. Of these, only gestational hypertensive disorders was more common among those delivering SGA infants, but gestational hypertensive disorders did not mediate nor moderate the association between CM and SGA. Substance use has previously been reported to mediate associations between CM and both birthweight and PTB15,16. However, these study populations had considerably higher rates of prenatal tobacco, alcohol, and recreational drug use (29% in Simon and McAnarney 1994 and 21% in Gavin et al. 2011) than our cohort15,16. The prevalence of substance use in our cohort may have been insufficient to exhibit a significant association with either birthweight or length of gestation.

Our results add to a growing literature evidencing the importance of early life exposures on intergenerational health outcomes. Adverse experiences during this sensitive developmental period may induce permanent or long-term alterations in neural, endocrine and immune systems which may be adaptive from the perspective of increased chances of survival in the short term. Over time these alterations may, however, have deleterious or unfavorable effects on the health and well-being of an individual72 and future generations11. CM-associated variation in maternal-placental-fetal (MPF) stress biology may underlie the observed association between CM and SGA60. CM has been associated with variation in cortisol concentrations, steeper increases in placental CRH and increased systemic inflammation during pregnancy (reviewed in Moog et al.11), biological alterations that may impair fetal growth by leading to maternal vascular underperfusion and/or chronic placental inflammatory lesions that reduce placental function critical for fetal growth61. Reduced intrauterine growth in association with maternal CM may contribute to higher cross-disease morbidity in offspring62, starting with the effects on fetal growth and development1–3,14–16 and extending to subsequent infant, child (behavioral problems, autism), and even adult health and disease risk63,64.

While prevalence rates for the other sequelae were in concordance with reported national rates65–67, our sample size (and consequent number of SGA deliveries in this sample) was too small to identify mediators of the association between CM and this complex phenotype with multifactorial etiology. We suggest that future studies take advantage of cohorts enriched for SGA births to replicate the higher prevalence of CM among individuals delivering an SGA offspring and investigate the role of these sequelae as potential mediators.

In the context of a healthy population not enriched for CM, our findings point to the potential clinical significance of screening for CM to detect risk for growth restriction and other adverse outcomes. The CTQ has been validated in multiple iterations that may be clinically useful68, and by identifying individuals exposed to CM, may provide opportunity for therapeutic intervention during pregnancy. Moreover, these findings indicate the need to identify effective treatments, such as those that may reduce stress and normalize stress physiology, which as a consequence may reduce SGA risk among those with CM histories.

This study has some limitations. First, CM was based on retrospective self-report using the CTQ. Retrospective reports in adulthood of childhood adverse experiences are subject to problems like non-awareness, non-disclosure, simple forgetting, and reporting biases due to mood states. However, while the recall of subtle details of early traumatic experiences may depend upon personal interpretations and more prone to recall bias, major experiences (i.e., abuse) are better recalled. In general, false negatives are more frequent than false positives69. This downward bias should, therefore, result in an observed estimate of the association between CM and SGA during pregnancy70 that is more conservative than the one that actually exists. Additionally, the CTQ demonstrates high internal consistency, good test–retest reliability, and convergence with other instruments65. The CTQ does not collect the date of exposure to CM, so we were unable to examine whether the timing of abuse is relevant to the association of CM and obstetric outcomes. We were also unable to evaluate PTSD symptomology or diagnosis, another highly prevalent consequence of CM, which in future studies should be examined as a potential mediator or moderator. Smoking and substance use during pregnancy was also based on self report, which is typically underreported66 and could have obscured this pathway in our study. Finally, we are not able to comment on resilience factors that may have contributed to these findings.

Our findings extend those from previous studies of childhood adversity and birth outcomes14,34,67 to show that CM is associated with increased risk for SGA birth independent of substance use, depression, obesity, and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. These findings support the notion that adversity in childhood sets a trajectory for long-term and intergenerational patterns of health, and may underlie persistent population disparities71.

Author contributions

A.B. conceptualized and coordinated the analyses, L.K.D. and A.F. performed statistical analyses, L.K.D., P.W., C.B., A.F., and A.B. interpreted the findings, L.K.D. was the primary writer of the mauscript, and G.M., W.G., S.E., H.S., P.W., C.B., A.F., and A.B. all contributed to writing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscipt.

Funding

Financial support for this research provided by the following sources: Funding for this study was provided by: HHSN275201200007I-HHSN27500005. National Children’s Study: Vanguard Study—Task Order 5: Stress and Cortisol Measurement for the National Children’s Study. Principal Investigator: Ann E.B. Borders, MD, MSc, MPH. This work was also supported, in part, by US PHS (NIH) grants R01 MH-105538, UH3 OD-023349 and ERC grant ERC-Stg 639766.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wosu AC, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Maternal history of childhood sexual abuse and preterm birth: An epidemiologic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15:174. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeners B, Stiller R, Block E, Gorres G, Rath W. Pregnancy complications in women with childhood sexual abuse experiences. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010;69(5):503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noll JG, Schulkin J, Trickett PK, Susman EJ, Breech L, Putnam FW. Differential pathways to preterm delivery for sexually abused and comparison women. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2007;32(10):1238–1248. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crispi F, Miranda J, Gratacós E. Long-term cardiovascular consequences of fetal growth restriction: Biology, clinical implications, and opportunities for prevention of adult disease. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018;218(2):S869–S879. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heim C, Binder EB. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: Review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp. Neurol. 2012;233(1):102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heim C, Newport DJ, Mletzko T, Miller AH, Nemeroff CB. The link between childhood trauma and depression: Insights from HPA axis studies in humans. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33(6):693–710. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danese A, Pariante CM, Caspi A, Taylor A, Poulton R. Childhood maltreatment predicts adult inflammation in a life-course study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104(4):1319–1324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610362104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006;256(3):174–186. doi: 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heim CM, Entringer S, Buss C. Translating basic research knowledge on the biological embedding of early-life stress into novel approaches for the developmental programming of lifelong health. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;105:123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moog NK, Heim CM, Entringer S, Simhan HN, Wadhwa PD, Buss C. Transmission of the adverse consequences of childhood maltreatment across generations: Focus on gestational biology. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2022;215:173372. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2022.173372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buss C, Entringer S, Moog NK, et al. Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood maltreatment exposure: Implications for fetal brain development. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2017;56(5):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Selk SC, Rich-Edwards JW, Koenen K, Kubzansky LD. An observational study of type, timing, and severity of childhood maltreatment and preterm birth. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2016;70(6):589–595. doi: 10.1136/jech-2015-206304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harville EW, Boynton-Jarrett R, Power C, Hypponen E. Childhood hardship, maternal smoking, and birth outcomes: A prospective cohort study. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2010;164(6):533–539. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gavin AR, Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Maas C. The role of maternal early-life and later-life risk factors on offspring low birth weight: Findings from a three-generational study. J. Adolesc. Health. 2011;49(2):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.11.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stevens-Simon C, McAnarney ER. Childhood victimization: Relationship to adolescent pregnancy outcome. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18(7):569–575. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burke HM, Davis MC, Otte C, Mohr DC. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: A meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30(9):846–856. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seth S, Lewis AJ, Galbally M. Perinatal maternal depression and cortisol function in pregnancy and the postpartum period: A systematic literature review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-0915-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iob E, Steptoe A. Adverse childhood experiences, inflammation, and depressive symptoms in later life: A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2019;394:S58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32855-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S. Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):68–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Bellis MD. Developmental traumatology: A contributory mechanism for alcohol and substance use disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27(1–2):155–170. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4530(01)00042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez WD, Seng JS. Posttraumatic stress disorder, smoking, and cortisol in a community sample of pregnant women. Addict. Behav. 2014;39(10):1408–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matthews KA, Chang Y-F, Thurston RC, Bromberger JT. Child abuse is related to inflammation in mid-life women: Role of obesity. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014;36:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell AM, Porter K, Christian LM. Examination of the role of obesity in the association between childhood trauma and inflammation during pregnancy. Health Psychol. 2018;37(2):114. doi: 10.1037/hea0000559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bublitz MH, Ward LG, Simoes M, Stroud LR, Salameh M, Bourjeily G. Maternal history of adverse childhood experiences and ambulatory blood pressure in pregnancy. Psychosom. Med. 2020;82(8):757. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petrov ME, Davis MC, Belyea MJ, Zautra AJ. Linking childhood abuse and hypertension: Sleep disturbance and inflammation as mediators. J. Behav. Med. 2016;39(4):716–726. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9742-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suglia SF, Clark CJ, Boynton-Jarrett R, Kressin NR, Koenen KC. Child maltreatment and hypertension in young adulthood. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dadi AF, Miller ER, Bisetegn TA, Mwanri L. Global burden of antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8293-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald SD, Han Z, Mulla S, Beyene J. Overweight and obesity in mothers and risk of preterm birth and low birth weight infants: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ. 2010;341:c3428. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quesada O, Gotman N, Howell HB, Funai EF, Rounsaville BJ, Yonkers KA. Prenatal hazardous substance use and adverse birth outcomes. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(8):1222–1227. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.602143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LC. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:2301. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Accortt EE, Cheadle AC, Schetter CD. Prenatal depression and adverse birth outcomes: An updated systematic review. Matern. Child Health J. 2015;19(6):1306–1337. doi: 10.1007/s10995-014-1637-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moog NK, Buss C, Entringer S, et al. Maternal exposure to childhood trauma is associated during pregnancy with placental-fetal stress physiology. Biol. Psychiat. 2016;79(10):831–839. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller GE, Culhane J, Grobman W, et al. Mothers' childhood hardship forecasts adverse pregnancy outcomes: Role of inflammatory, lifestyle, and psychosocial pathways. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017;65:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross KM, Miller G, Culhane J, et al. Patterns of peripheral cytokine expression during pregnancy in two cohorts and associations with inflammatory markers in cord blood. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2016;76:406–414. doi: 10.1111/aji.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keenan-Devlin LS, Smart BP, Grobman W, et al. The intersection of race and socioeconomic status is associated with inflammation patterns during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2022;87(3):e13489. doi: 10.1111/aji.13489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keenan-Devlin LS, Caplan M, Freedman A, et al. Using principal component analysis to examine associations of early pregnancy inflammatory biomarker profiles and adverse birth outcomes. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021;86(6):e13497. doi: 10.1111/aji.13497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elo IT, Culhane JF, Kohler IV, et al. Neighbourhood deprivation and small-for-gestational-age term births in the United States. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2009;23(1):87–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fenton TR, Kim JH. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bernstein, D. P., Fink, L., Handelsman, L., Foote, J. Childhood trauma questionnaire. In Assessment of Family Violence: A Handbook for Researchers and Practitioners. (1998).

- 41.Kleih TS, Entringer S, Scholaske L, et al. Exposure to childhood maltreatment and systemic inflammation across pregnancy: The moderating role of depressive symptomatology. Brain Behav. Immun. 2022;101:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2022.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schummers L, Hacker MR, Williams PL, et al. Variation in relationships between maternal age at first birth and pregnancy outcomes by maternal race: A population-based cohort study in the United States. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12):e033697. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wildeman C, Emanuel N, Leventhal JM, Putnam-Hornstein E, Waldfogel J, Lee H. The prevalence of confirmed maltreatment among US children, 2004 to 2011. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):706–713. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hussey JM, Chang JJ, Kotch JB. Child maltreatment in the United States: Prevalence, risk factors, and adolescent health consequences. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):933–942. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ewing AC, Ellington SR, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Barfield WD, Kourtis AP. Full-term small-for-gestational-age newborns in the US: Characteristics, trends, and morbidity. Matern. Child Health J. 2017;21(4):786–796. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2165-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiPietro JA, Ghera MM, Costigan K, Hawkins M. Measuring the ups and downs of pregnancy stress. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004;25(3–4):189–201. doi: 10.1080/01674820400017830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leeners B, Stiller R, Block E, Görres G, Rath W. Pregnancy complications in women with childhood sexual abuse experiences. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010;69(5):503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bodnar LM, Siega-Riz AM, Simhan HN, Himes KP, Abrams B. Severe obesity, gestational weight gain, and adverse birth outcomes. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010;91(6):1642–1648. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.29008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valeri L, Vanderweele TJ. Mediation analysis allowing for exposure-mediator interactions and causal interpretation: Theoretical assumptions and implementation with SAS and SPSS macros. Psychol. Methods. 2013;18(2):137–150. doi: 10.1037/a0031034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.SAS Institute I. SAS/STAT® 14.3 User’s Guide: The CAUSALMED Procedure. (SAS Institute Inc., 2017).

- 53.Scher CD, Forde DR, McQuaid JR, Stein MB. Prevalence and demographic correlates of childhood maltreatment in an adult community sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(2):167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McCowan L, Horgan RP. Risk factors for small for gestational age infants. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2009;23(6):779–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Odibo AO, Nelson D, Stamilio DM, Sehdev HM, Macones GA. Advanced maternal age is an independent risk factor for intrauterine growth restriction. Am. J. Perinatol. 2006;23(5):325–328. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-947164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Groom KM, North RA, Poppe KK, Sadler L, McCowan LM. The association between customised small for gestational age infants and pre-eclampsia or gestational hypertension varies with gestation at delivery. BJOG Int. J. Obstetr. Gynaecol. 2007;114(4):478–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson JM, Clark PM, Robinson E, et al. Risk factors for small-for-gestational-age babies: The Auckland Birthweight Collaborative Study. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2001;37(4):369–375. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2001.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martin, J. A., Hamilton, B. E., Osterman, M. J., Driscoll, A. K., Mathews, T. J. Births: Final Data for 2015. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 66(1), 1 (2017). [PubMed]

- 59.Wosu AC, Gelaye B, Williams MA. Maternal history of childhood sexual abuse and preterm birth: An epidemiologic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12884-015-0606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McCrory EJ, Gerin MI, Viding E. Annual research review: childhood maltreatment, latent vulnerability and the shift to preventative psychiatry–the contribution of functional brain imaging. J. Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2017;58(4):338–357. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buss C, Entringer S, Moog NK, et al. Intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood maltreatment exposure: Implications for fetal brain development. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2017;56(5):373–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnston RC, Faulkner M, Carpenter PM, et al. Associations between placental corticotropin-releasing hormone, maternal cortisol, and birth outcomes, based on placental histopathology. Reprod. Sci. 2020;27:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s43032-020-00182-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moog NK, Cummings PD, Jackson KL, et al. Intergenerational transmission of the effects of maternal exposure to childhood maltreatment in the USA: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(3):e226–e237. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(23)00025-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luu TM, Mian MOR, Nuyt AM. Long-term impact of preterm birth: Neurodevelopmental and physical health outcomes. Clin. Perinatol. 2017;44(2):305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raju TN, Pemberton VL, Saigal S, Blaisdell CJ, Moxey-Mims M, Buist S. Long-term healthcare outcomes of preterm birth: An executive summary of a conference sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. J. Pediatr. 2017;181(309–318):e301. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bernstein DP, Fink L, Handelsman L, et al. Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994;151:1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hall ES, Wexelblatt SL, Greenberg JM. Self-reported and laboratory evaluation of late pregnancy nicotine exposure and drugs of abuse. J. Perinatol. 2016;36(10):814–818. doi: 10.1038/jp.2016.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morton SM, De Stavola BL, Leon DA. Intergenerational determinants of offspring size at birth: A life course and graphical analysis using the Aberdeen Children of the 1950s Study (ACONF) Int. J. Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):749–759. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, et al. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27(2):169–190. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Moog NK, Wadhwa PD, Entringer S, Heim CM, Gillen DL, Buss C. The challenge of ascertainment of exposure to childhood maltreatment: Issues and considerations. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2020;125:105102–105102. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2020.105102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shonkoff JP, Boyce WT, McEwen BS. Neuroscience, molecular biology, and the childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. JAMA. 2009;301(21):2252–2259. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.