Key Points

Question

Is dual antiplatelet therapy noninferior to intravenous thrombolysis in patients with minor nondisabling acute ischemic stroke?

Findings

In this noninferiority randomized clinical trial that included 760 participants, excellent neurologic function at 90 days (modified Rankin Scale score of 0 or 1) occurred in 93.8% of those randomized to receive dual antiplatelet therapy and 91.4% of those randomized to receive intravenous alteplase, a difference greater than the prespecified noninferiority margin of −4.5%.

Meaning

Among patients with minor nondisabling acute ischemic stroke, dual antiplatelet therapy, compared with intravenous alteplase, met the criteria for noninferiority with regard to excellent functional outcome at 90 days.

Abstract

Importance

Intravenous thrombolysis is increasingly used in patients with minor stroke, but its benefit in patients with minor nondisabling stroke is unknown.

Objective

To investigate whether dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is noninferior to intravenous thrombolysis among patients with minor nondisabling acute ischemic stroke.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter, open-label, blinded end point, noninferiority randomized clinical trial included 760 patients with acute minor nondisabling stroke (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤5, with ≤1 point on the NIHSS in several key single-item scores; scale range, 0-42). The trial was conducted at 38 hospitals in China from October 2018 through April 2022. The final follow-up was on July 18, 2022.

Interventions

Eligible patients were randomized within 4.5 hours of symptom onset to the DAPT group (n = 393), who received 300 mg of clopidogrel on the first day followed by 75 mg daily for 12 (±2) days, 100 mg of aspirin on the first day followed by 100 mg daily for 12 (±2) days, and guideline-based antiplatelet treatment until 90 days, or the alteplase group (n = 367), who received intravenous alteplase (0.9 mg/kg; maximum dose, 90 mg) followed by guideline-based antiplatelet treatment beginning 24 hours after receipt of alteplase.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was excellent functional outcome, defined as a modified Rankin Scale score of 0 or 1 (range, 0-6), at 90 days. The noninferiority of DAPT to alteplase was defined on the basis of a lower boundary of the 1-sided 97.5% CI of the risk difference greater than or equal to −4.5% (noninferiority margin) based on a full analysis set, which included all randomized participants with at least 1 efficacy evaluation, regardless of treatment group. The 90-day end points were assessed in a blinded manner. A safety end point was symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage up to 90 days.

Results

Among 760 eligible randomized patients (median [IQR] age, 64 [57-71] years; 223 [31.0%] women; median [IQR] NIHSS score, 2 [1-3]), 719 (94.6%) completed the trial. At 90 days, 93.8% of patients (346/369) in the DAPT group and 91.4% (320/350) in the alteplase group had an excellent functional outcome (risk difference, 2.3% [95% CI, −1.5% to 6.2%]; crude relative risk, 1.38 [95% CI, 0.81-2.32]). The unadjusted lower limit of the 1-sided 97.5% CI was −1.5%, which is larger than the −4.5% noninferiority margin (P for noninferiority <.001). Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage at 90 days occurred in 1 of 371 participants (0.3%) in the DAPT group and 3 of 351 (0.9%) in the alteplase group.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with minor nondisabling acute ischemic stroke presenting within 4.5 hours of symptom onset, DAPT was noninferior to intravenous alteplase with regard to excellent functional outcome at 90 days.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03661411

This randomized trial examines whether dual antiplatelet therapy is noninferior to intravenous thrombolysis among patients with minor nondisabling acute ischemic stroke.

Introduction

Current guidelines recommend intravenous alteplase for patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) presenting within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.1,2,3 Minor stroke, defined as a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score less than or equal to 5, accounted for approximately half of patients with AIS in 2016 (50.0%)4 and in 2019 (46.9%),5 but the evidence in support of intravenous thrombolysis for these patients has remained inconclusive.6,7 The Effect of Alteplase vs Aspirin on Functional Outcome for Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke and Minor Nondisabling Neurologic Deficits (PRISMS) study compared intravenous alteplase vs aspirin alone in patients with minor nondisabling deficits.7 The results showed no significant difference in the 90-day functional outcomes between the groups, but a higher rate of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH) in the alteplase group.

The Clopidogrel and Aspirin in Acute Ischemic Stroke and High-Risk TIA (POINT) and Clopidogrel with Aspirin in Acute Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (CHANCE) studies confirmed the efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients presenting with minor stroke within 12 and 24 hours of symptom onset, respectively.8,9 The CHANCE study indicated that the benefit of reducing recurrent stroke with DAPT would be most effective within the first 2 weeks.10

In this context, it is possible that a 2-week course of DAPT could have a similar efficacy as intravenous alteplase on 90-day functional outcomes in patients presenting with minor nondisabling stroke. The aim of the Antiplatelet vs R-tPA for Acute Mild Ischemic Stroke (ARAMIS) study was to determine whether DAPT would be noninferior to intravenous alteplase with respect to efficacy and less hemorrhagic events in patients with AIS presenting with nondisabling deficits within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a multicenter, randomized, open-label, blinded end point assessment, noninferiority trial to assess the efficacy and safety of DAPT compared with intravenous alteplase in patients presenting with minor stroke and nondisabling deficits within 4.5 hours of symptom onset.

The protocol, which has been published11 and is available in Supplement 1, was approved by the ethics committees of all participating sites. Both the final protocol and statistical analysis plan (Supplement 2) were completed on May 6, 2020. Signed informed consent was obtained from patients or their authorized representatives. The investigators vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data, for the adherence to the trial protocol, and for the accurate reporting of adverse events.

The trial was conducted at 38 hospitals (eAppendix 1 in Supplement 3) in China. On-site and online training were provided before and during the study to ensure protocol compliance. A steering committee met monthly to oversee the trial. An independent data and safety monitoring committee regularly reviewed safety data (eAppendix 2 in Supplement 3). An independent clinical research organization (Liaoning Zhongshuang Medical Technology Co, Ltd) monitored the trial for quality control.

Participants

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were 18 years or older; had an acute ischemic stroke with an NIHSS score (range, 0 to 42; higher scores indicate greater stroke severity) less than or equal to 5, with less than or equal to 1 point on single-item scores, such as vision, language, neglect, or single limb weakness, and a score of 0 in the consciousness item at the time of randomization; had computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging performed on admission to identify ischemic stroke; and could start receiving study treatment within 4.5 hours of stroke symptoms. Exclusion criteria were prestroke disability (modified Rankin Scale [mRS] score ≥2; range, 0 [no symptoms] to 6 [death]), history of intracerebral hemorrhage, or definite indication for anticoagulation. All investigators were trained with regards to adjudicating a prestroke deficit as nondisabling by consultation with patients and their available family members based on the patient’s career and hobbies to adjudicate whether the neurologic deficit would affect the patient’s activities of daily living and work. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 3.

Randomization and Masking

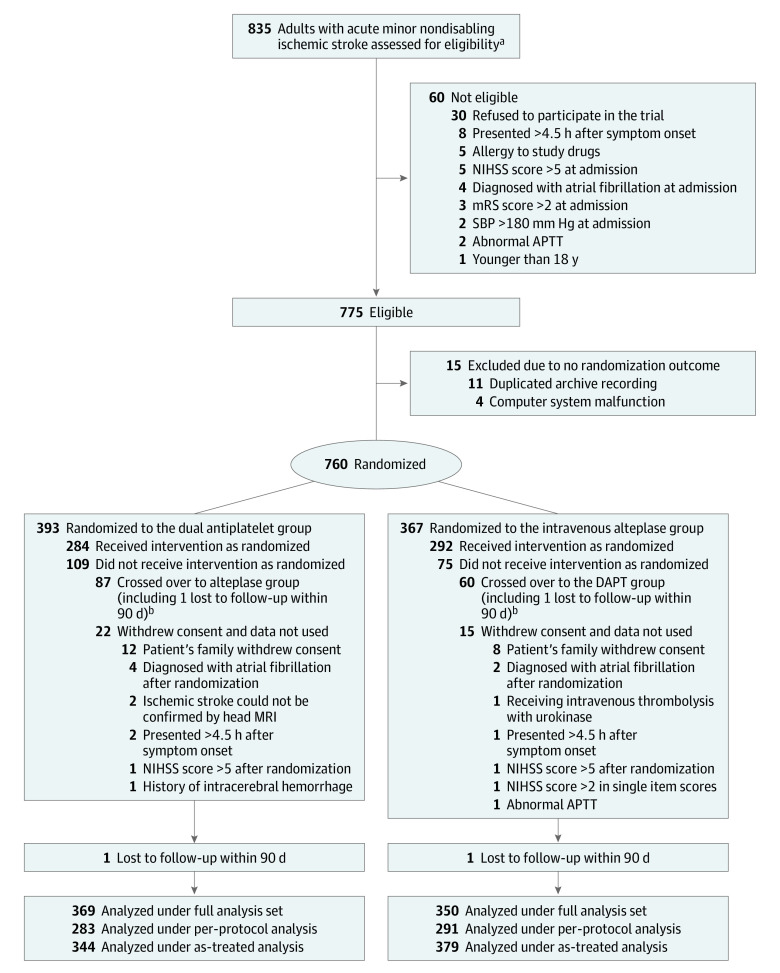

Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive DAPT or intravenous alteplase (Figure 1) with the simple randomization method without blocking schema through a computer-generated random sequence via a central web-based program at http://aramis.medsci.cn (Shanghai Meisi Medical Technology Co, Ltd). The study team members were unblinded to treatment randomization. Trained assessors, who determined 90-day outcomes, were unaware of the treatment group assignments.

Figure 1. Patient Flow in the ARAMIS Randomized Clinical Trial.

APTT indicates abnormal activated partial thromboplastin time; ARAMIS, Antiplatelet vs R-tPA for Acute Mild Ischemic Stroke; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

aEligibility was assessed according to inclusion criteria by local trained neurologists.

bThe high crossover rate was attributed to consent misunderstanding or fluctuation of neurological deficit, which resulted in the crossover requested by patients or their authorized representatives, or as decided by investigators. The baseline characteristics in patients who crossed over are shown in eTable 10 in Supplement 3.

Procedures

Patients were randomized to the alteplase group (according to guidelines1,2,3: 0.9 mg/kg [10% as a bolus, 90% infused over 1 hour] to a maximum of 90 mg, followed by guideline-based antiplatelet treatment beginning 24 hours after intravenous thrombolysis) or DAPT group (a loading dose of 300 mg of clopidogrel on the first day, followed by 75 mg per day for 12 [±2] days; 100 mg of aspirin on the first day, followed by 100 mg daily for 12 [±2] days; and single antiplatelet therapy or DAPT based on guidelines until 90 days).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was excellent functional outcome at 90 days, defined as an mRS score of 0 to 1. The secondary outcomes were favorable functional outcome (mRS score of 0 to 2) at 90 days, change in NIHSS score at 24 hours, early neurological improvement at 24 hours (defined as a decrease of 2 or more points in the NIHSS score), early neurological deterioration at 24 hours (defined as an increase of 2 or more points in the NIHSS score but not as a result of cerebral hemorrhage), new stroke or other vascular events at 90 days, 90-day all-cause mortality, and ordinal shift of the mRS score at 90 days.

The safety outcomes were sICH and any bleeding event during the study. sICH was defined as evidence of bleeding on head computed tomographic scan associated with neurological deterioration (≥4-point increase in NIHSS score).

Clinical assessments were performed at baseline and 24 hours, 7 days, 12 days (or hospital discharge if earlier), and 90 days after randomization. The baseline and follow-up NIHSS scores were evaluated by the same neurologist. Follow-up at 90 days was done in person or by telephone (if in-person assessment was not possible) by a certified staff member in each center who was unaware of the treatment assignment. To ensure validity and reproducibility of the evaluation, a training course was held for all investigators. Central adjudication of clinical outcomes and adverse events was done by trained physicians unaware of patient treatment assignment (eMethods in Supplement 3).

Sample Size Calculation

Power calculations were based on the estimated treatment effects of a binary assessment of excellent functional outcomes at 90 days. Sample size assumptions were amended in May 2020 based on new registry information regarding the expected excellent functional outcome rate in the thrombolytic group and recognition that the initial sample size calculations had inadvertently been based on a superiority design. In the Intravenous Thrombolysis Registry for Chinese Ischemic Stroke Within 4.5 Hours of Onset Study (INTRECIS),12 the percentage of patients with excellent functional outcome in minor acute stroke treated with alteplase was estimated to be 87%. Based on the PRISMS trial,7 we assumed that the percentage of patients with excellent functional outcome was 89.5% in the DAPT group. We estimated that a sample size of 666 would provide 80% power (at a 1-sided α level of .025) to test the hypothesis that the percentage of patients with excellent functional outcomes in the DAPT group would be noninferior to the alteplase group with a lower boundary of the 1-sided 97.5% CI of the risk difference greater than or equal to −4.5%. The choice of the noninferiority margin of −4.5% was based on the Third International Stroke Trial (IST-3), in which a subgroup analysis showed a 9% absolute difference in the proportion of favorable outcome in patients with minor stroke who were treated with intravenous alteplase compared with standard medical treatment.13 We contended that preserving at least 50% of the alteplase treatment effect observed in the IST-3 trial would be clinically meaningful considering the convenience, cost, and safety of DAPT vs alteplase. Therefore, −4.5% was used as the noninferiority margin in this trial. Assuming a 12% attrition rate, the sample size was 757 participants and was rounded up to 760 participants.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed on a full analysis set, which included all randomized participants with at least 1 efficacy evaluation according to the group they were originally assigned. A generalized linear model (GLM) with binomial distribution and identity link function was performed for the primary outcome, generating a risk difference between DAPT or intravenous alteplase treatment with the 2-sided 95% CI (equivalent to the 1-sided 97.5% CI). Risk ratios and 95% CIs were also calculated using GLMs. In sensitivity analyses, missing values in the primary outcome were imputed using the last observation carried forward, the worst-case scenario, and best-case scenario approaches. An interim analysis was planned after 50% of patients had completed follow-up, but was not performed due to no safety concerns after discussion of the steering committee with the data and safety monitoring committee (Supplement 2). Other secondary outcomes were analyzed similarly.

The 90-day mRS score was compared using ordinal logistic regression via GLM with treatment effect presented as odds ratio with 95% CIs. A GLM was also used to compare changes in log (NIHSS score + 1) between admission and 24 hours and a geometric mean ratio and 95% CI was calculated between the DAPT and alteplase groups. Time-to-event outcomes of stroke and other vascular events were compared using Cox regression models, and the corresponding treatment effects are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs. The proportionality assumption was tested by including a time × treatment interaction in the Cox model.

The primary analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes were unadjusted. A death event was equivalent to an mRS score of 6. Covariate-adjusted GLM analyses were performed for all outcomes, adjusting for 7 prespecified factors: age, sex, diabetes, baseline NIHSS, time from symptom onset to treatment, location of responsible vessel, and stroke etiology. The degree of vascular stenosis was not included as an adjustment covariate as originally prespecified because missingness exceeded 30%. In addition, for sensitivity analyses of the primary outcome, prespecified factors plus crossover as a post hoc covariate-adjusted analysis was performed with the same method.

Subgroup analysis of the primary outcome was performed using a GLM with identity link function on 8 prespecified subgroups (age [<65 years or ≥65 years], history of diabetes [present or not present], time from symptom onset to treatment [≤2 hours or >2 hours], location of index vessel [anterior circulation or posterior circulation], sex [women or men], NIHSS score at randomization [0-3 or 4-5], stroke etiology (large artery atherosclerosis, cardioembolic, small artery occlusion, other determined cause, and undetermined cause) and degree of vascular stenosis (<50% vs ≥50%). Detailed statistical analyses are described in the statistical analysis plan (Supplement 2). In addition, large artery occlusion (yes or no) as a post hoc subgroup analysis was also performed with the same method. Assessment of the homogeneity of treatment effect by a subgroup variable was conducted using a GLM model with the treatment, subgroup variable, and their interaction term as independent variables and the P value presented for the interaction term.

The primary analysis was based on a full analysis set population, defined as all patients with valid informed consent regardless of whether they prematurely discontinued treatment or otherwise violated protocol, which did not include patients who were lost to follow-up or withdrew consent. Per-protocol and as-treated analyses for the primary and secondary outcomes were performed using the same methods. The safety population, which consisted of all randomized patients who received at least 1 dose of the study drug and didn’t withdraw consent, was used for the analysis of adverse events. Complete definitions of all analytic populations are shown in Supplement 2. For the secondary outcomes, a 2-sided P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. Because of the potential for inflating the type I error due to multiple comparisons, the findings from subgroup and secondary outcome analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute), SPSS version 23 (IBM Corporation), and R version 4.1.0 (R Development Core Team; http://www.r-project.org) were used for the statistical analyses.

Results

Trial Population

Between October 1, 2018, and April 18, 2022, a total of 835 patients were screened and 760 were randomized to the DAPT (393 patients) or alteplase (367 patients) groups, after exclusion of 75 patients (60 were ineligible because they did not meet inclusion criteria and 15 were excluded due to no randomization outcome). After 37 patients (5.0%) were additionally excluded (20 withdrew consent due to patient decision and 17 withdrew due to clinical reasons), the full analysis set population included 719 patients (369 in the DAPT group and 350 in the alteplase group; Figure 1). Due to a total of 147 patients who had a protocol violation, which involved 87 patients in the DAPT group crossing over to the alteplase group and 60 patients in the alteplase group crossing over to the DAPT group, 574 patients in the per-protocol population (283 in DAPT group and 291 in alteplase group) and 723 in the as-treated population (344 in DAPT group and 379 in alteplase group) were included (Figure 1; eFigure 1 in Supplement 3). The trial was completed in July 2022.

The treatment groups were well balanced with respect to baseline patient characteristics in the full analysis set (Table 1), per-protocol (eTable 1 in Supplement 3), and as-treated (eTable 2 in Supplement 3) populations. The median (IQR) age of the patients was 64 (57-71) years and 223 patients (31.0%) were women. The median (IQR) NIHSS score was 2 (1-3). The median (IQR) time from stroke onset to treatment was 182 (133-230) minutes in the DAPT group and 180 (126-225) minutes in the alteplase group. There were 241 patients (33.7%) with missing vessel imaging data. Detailed information on antiplatelet treatment after hospital discharge is shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 3.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics in the Full Analysis Set.

| Baseline characteristics | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dual antiplatelet therapy (n = 369) | Alteplase (n = 350) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 65 (57-71) | 64 (56-71) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 256 (69.5) | 240 (68.6) |

| Women | 113 (30.6) | 110 (31.4) |

| Current smokinga | 122 (33.1) | 118 (33.7) |

| Current drinkinga | 59 (16.0) | 56 (16.0) |

| Medical history | ||

| Hypertension | 211 (57.2) | 169 (48.3) |

| Diabetes | 101 (27.4) | 86 (24.6) |

| Prior ischemic strokeb | 82 (22.2) | 77 (22.0) |

| Prior transient ischemic attack | 4 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| Time from onset of symptoms to receipt of assigned treatment, median (IQR), min | 182 (134-230) | 180 (127-225) |

| Time from onset of symptoms to hospital discharge, median (IQR), d | 8 (6-11) | 8 (6-10) |

| INR at randomization, median (IQR) | 1.00 (0.94-1.05) | 0.98 (0.93-1.04) |

| INR >1.2 at randomization | 5/358 (1.4) | 4/344 (1.2) |

| APTT at randomization, median (IQR), s | 31.8 (27.2-36.3) | 31.9 (27.4-35.7) |

| Median APTT >43.5 s at randomization | 15 (4.1) | 13 (3.7) |

| Systolic blood pressure at randomization, median (IQR), mm Hg | 150 (137-166) | 151 (139-162) |

| Median systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg at randomization | 245 (66.4) | 242 (69.1) |

| Diastolic blood pressure at randomization, median (IQR), mm Hg | 88 (81-95) | 88 (80-95) |

| Median (IQR) diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg at randomization | 142 (38.5) | 132 (37.7) |

| Blood glucose level at randomization, median (IQR), mmol/L | 6.3 (5.4-8.3) | 6.4 (5.4-8.1) |

| Blood glucose level >7.0 mmol/L at randomization | 112/316 (35.4) | 121/314 (38.5) |

| NIHSS score at randomization, median (IQR)c | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) |

| NIHSS score of 0 at randomization | 27 (7) | 29 (8) |

| Estimated prestroke function (mRS score) | ||

| No symptoms (score of 0) | 275 (74.5) | 256 (73.1) |

| Symptoms without any disability (score of 1) | 94 (25.5) | 94 (26.9) |

| Presumed stroke caused | ||

| Undetermined cause | 225 (61.0) | 221 (63.1) |

| Small artery occlusion | 87 (23.6) | 79 (22.6) |

| Large artery atherosclerosis | 54 (14.6) | 46 (13.1) |

| Other determined cause | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.9) |

| Cardioembolic | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Location of responsible vessele | ||

| Anterior circulation | 283 (76.7) | 279 (79.7) |

| Posterior circulation | 83 (22.5) | 70 (20.0) |

| Anterior and posterior circulation | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| Degree of responsible vessel stenosisf | ||

| Mild (<50%) | 191/246 (77.6) | 185/232 (79.7) |

| Moderate (50%-69%) | 21/246 (8.5) | 15/232 (6.5) |

| Severe (70%-99%) | 14/246 (5.7) | 16/232 (6.9) |

| Occlusion (100%) | 20/246 (8.1) | 16/232 (6.9) |

Abbreviations: APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; INR, international normalized ratio.

SI conversion factor: To convert glucose to mg/dL, divide by 0.0555.

Current smoking defined as consuming at least 1 cigarette per day within 1 year before the onset of the disease. Current drinking defined as consuking alcohol at least once a week within 1 year before the onset of the disease and consume alcohol continuously for more than 1 year.

Referring only to patients with premorbid modified Rankin Sclae (mRS) score ≤1.

Patients with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores less than or equal to 5 were eligible for this study; NIHSS scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe neurological deficit.

The presumed stroke cause was classified according to the Trial of Org 10172 in the Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification system.

The classification was defined according to the anatomical location of responsible vessel based on the patient’s clinical presentation and neuroimaging, which refers to the clinical features of the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project classification system.

The degree of stenosis was determined by cerebral vessel examination. The diagnosis was based on the clinician’s interpretation of the clinical presentation and results of the investigations at the time of hospital discharge.

Primary Outcome

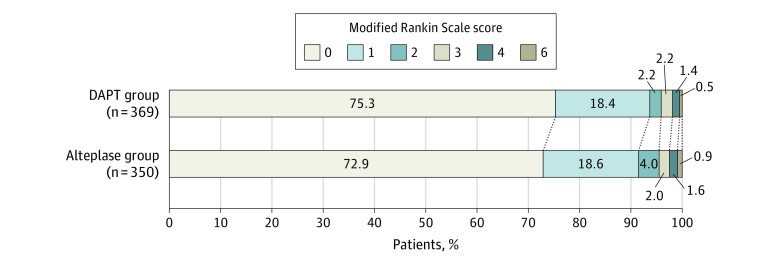

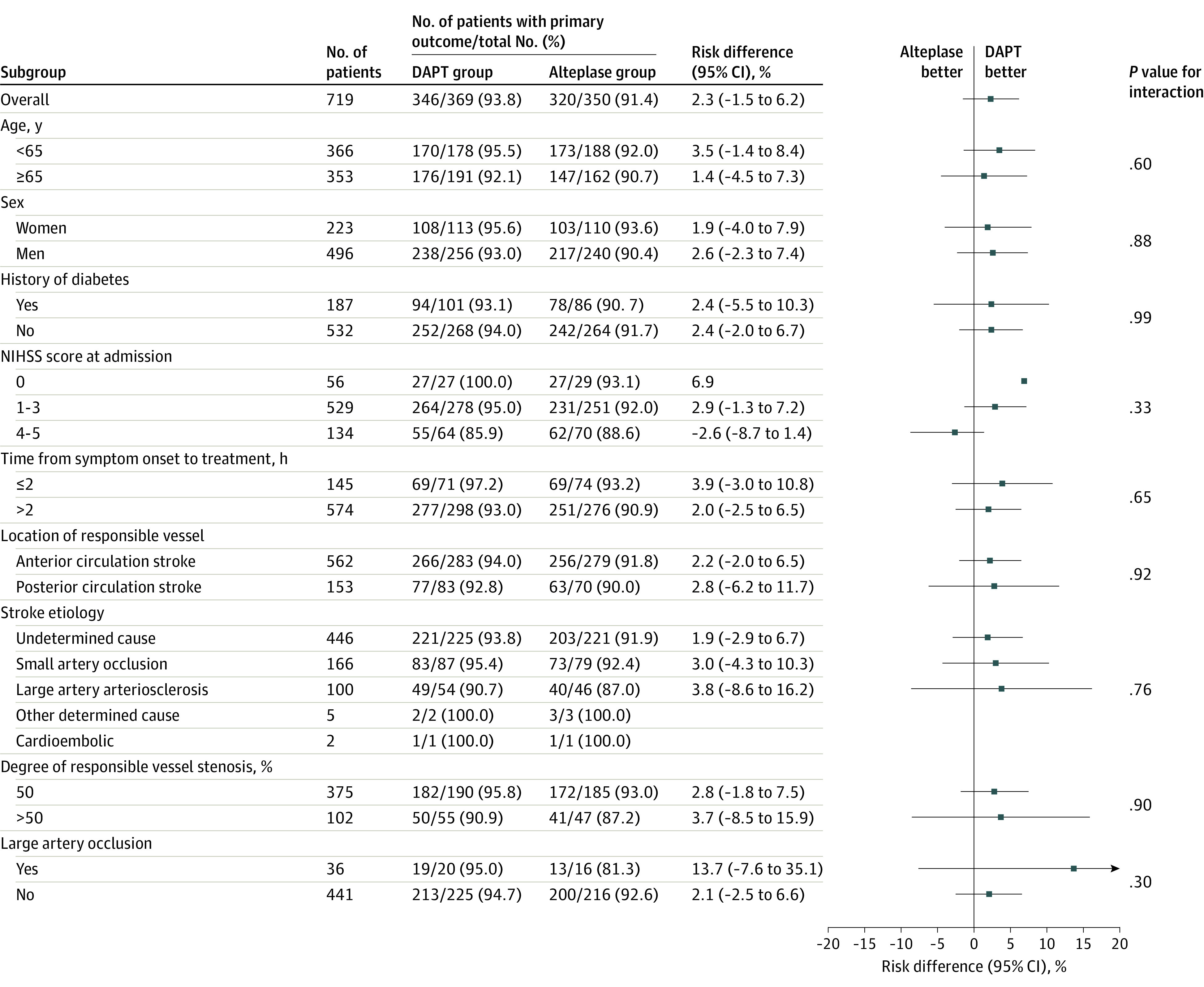

For the primary outcome, the percentage of patients with mRS scores of 0 or 1 at 90 days was 93.8% (346/369) in the DAPT group and 91.4% (320/350) in the alteplase group. In the full analysis set, the risk difference of having an excellent outcome at 90 days was 2.3% (unadjusted 95% CI, −1.5% to 6.2%; P < .001 for noninferiority; adjusted 95% CI, −1.6% to 6.1%; Table 2, Figure 2). The per-protocol (eFigure 2 and eTable 4 in Supplement 3) and as-treated (eFigure 3 and eTable 5 in Supplement 3) analyses yielded similar results. Similar risk difference results were observed in the last observation carried forward, worst-case scenario, and best-case scenario sensitivity analyses (eTable 6 in Supplement 3). DAPT was shown to be noninferior to intravenous alteplase because the lower boundary of the 2-sided 95% (1-sided 97.5%) CI was greater than the prespecified value of −4.5% (eTable 7 in Supplement 3). Furthermore, there was no effect of crossovers on the noninferiority result in the primary outcome (eTable 8 in Supplement 3). Results of subgroup analyses in the full analysis set, per-protocol, and as-treated populations are presented in Figure 3 and eFigure 4 and eFigure 5 in Supplement 3, respectively. There was no treatment heterogeneity in the absolute risk of having a primary outcome across these subgroups.

Table 2. Trial Outcomes in the Full Analysis Set and Safety Population.

| Outcome | No. (%) | Treatment effect metric | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual antiplatelet treatment (n = 369) | Alteplase (n = 350) | Treatment difference (95% CI) | P value | Treatment difference (95% CI) | P value | ||

| Primary outcome (full analysis set) | |||||||

| mRS score 0-1 within 90 db | 346 (93.8) | 320 (91.4) | Risk differencec,d | 2.3% (−1.5% to 6.2%) | <.001 | 2.3% (−1.6% to 6.1%) | <.001 |

| Risk ratioc | 1.38 (0.81 to 2.32) | .23 | 1.36 (0.80 to 2.30) | .22 | |||

| Secondary outcomes (full analysis set) | |||||||

| mRS score 0-2 within 90 db | 354 (95.9) | 334 (95.4) | Risk differencec | 0.5% (−2.5% to 3.5%) | .74 | 0.5% (−3.5% to 2.5%) | .83 |

| Risk ratioc | 1.12 (0.56 to 2.24) | .74 | 1.12 (0.56 to 2.25) | .64 | |||

| mRS score distribution within 90 db | Odds ratioc | 1.16 (0.83 to 1.61) | .39 | 1.11 (0.80 to 1.55) | .51 | ||

| Early neurological improvement within 24 he | 62 (16.8) | 74 (21.1) | Risk differencec | −4.1% (−9.8% to 1.7%) | .16 | −3.1% (−8.7% to 2.4%) | .27 |

| Risk ratioc | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.02) | .17 | 0.84 (0.62 to 1.14) | .27 | |||

| Early neurological deterioration within 24 hf | 17 (4.6) | 32 (9.1) | Risk differencec | −4.5% (−8.2% to −0.8%) | .02 | −4.6% (−8.3% to −0.9%) | .02 |

| Risk ratioc | 0.50 (0.29 to 0.89) | .02 | 0.50 (0.28 to 0.89) | .02 | |||

| Median change in NIHSS score at 24 h from baselineg | 0 (−0.41 to 0) | 0 (−0.69 to 0) | Geometric mean ratioc | 0.03 (−0.05 to 0.11) | .51 | 0.01 (−0.07 to 0.09) | .68 |

| Stroke or other vascular events within 90 d | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | Hazard ratioh | 0.47 (0.04 to 5.20) | .54 | 0.46 (0.04 to 5.17) | .45 |

| Death at 90 d | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.9) | Risk differencec | −0.3% (−1.5% to 0.9%) | .61 | −0.3% (−1.5% to 0.9%) | .49 |

| Risk ratioc | 0.63 (0.11 to 3.76) | .61 | 0.58 (0.10 to 3.51) | .49 | |||

| Safety outcomes (safety population) | |||||||

| Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhagei | 1/371 (0.3) | 3/352 (0.9) | Risk differencec | −0.6% (−1.7% to 0.5%) | .30 | −2.4% (−12.1% to 7.3%) | .63 |

| Risk ratioc | 0.32 (0.03 to 3.02) | .32 | 0.31 (0.03 to 2.99) | .36 | |||

| Any bleeding eventsj | 6/371 (1.6) | 19/352 (5.4) | Risk differencec | −3.8% (−6.5% to −1.1%) | .006 | −3.6% (−6.4% to −0.7%) | .01 |

| Risk ratioc | 0.30 (0.12 to 0.74) | .009 | 0.31 (0.12 to 0.76) | .01 | |||

Adjusted for prespecified prognostic variables (age, sex, history of diabetes, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score at randomization, time from symptom onset to receipt of assigned treatment, location of responsible vessel, and stroke etiology). The degree of vascular stenosis was planned in the covariate-adjusted analyses but was excluded due to a large percentage of missing values (see Supplement 2).

Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores range from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms; 1, symptoms without clinically significant disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability; and 6, death.

Calculated using a generalized linear model.

Noninferiority was met if the lower limit of the 1-sided 97.5% (2-sided 95%) CI for the risk difference was above −4.5%. P values for noninferiority of the crude and adjusted analyses are presented.

Early neurological improvement was defined as a decrease in NIHSS score of ≥2 between baseline and 24 hours.

Early neurological deterioration was defined as an increase in NIHSS score of ≥2 between baseline and 24 hours, but not as a result of cerebral hemorrhage.

NIHSS scores range from 0-42, with higher scores indicating greater stroke severity. The log (NIHSS + 1) was analyzed using a generalized linear model.

Calculated using Cox regression model. No violation of hazard proportionality assumption was found and the P value for the interaction was .36.

Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage was defined as any evidence of bleeding on the head computed tomographic scan associated with clinically significant neurological deterioration (≥4-point increase in NIHSS score).

There was 1 patient with symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage and 5 patients with gingival bleeding in the dual antiplatelet therapy group. There was 1 patient with epistaxis, 1 patient with asymptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, 3 patients with symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, and 14 patients with gingival bleeding in the alteplase group.

Figure 2. Distribution of Modified Rankin Scale Scores at 90 Days in the Full Analysis Set.

The raw distribution of scores is shown. Modified Rankin Scale scores ranged from 0 to 6, with 0 indicating no symptoms; 1, symptoms without clinically significant disability; 2, slight disability; 3, moderate disability; 4, moderately severe disability; 5, severe disability; and 6, death. DAPT indicates dual antiplatelet therapy.

Figure 3. Primary Outcome by Prespecified Subgroups in the Full Analysis Set.

The primary outcome was a modified Rankin Scale score of 0 to 1 at 90 days. For subcategories, black squares represent point estimates and horizontal lines represent the 95% CI. National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe neurological deficits. DAPT indicates dual antiplatelet therapy.

Secondary Outcomes

For secondary outcomes, the results in both the unadjusted and adjusted full analysis set populations are shown in Table 2. In the full analysis set, no significant differences between the groups were found in secondary outcomes, except that less patients had early neurological deterioration at 24 hours in the DAPT group than the alteplase group (unadjusted RD, −4.5% [95% CI, −8.2% to −0.8%]; adjusted RD, −4.6% [95% CI, −8.3% to −0.9%]; Table 2). In the per-protocol and as-treated analyses, similar results were obtained, but a lower risk of early neurological improvement was observed in the DAPT group (eTable 4 and eTable 5 in Supplement 3).

Adverse Events

Analyses of adverse events were based on the safety population. One patient experienced sICH and 6 patients experienced other bleeding events in the DAPT group, while 3 patients experienced sICH and 19 patients experienced other bleeding events in the alteplase group (Table 2; eTable 4 and eTable 5 in Supplement 3). The detailed intracerebral hemorrhage data are shown in eTable 9 in Supplement 3.

Discussion

This randomized trial showed that among patients with nondisabling minor acute ischemic stroke, DAPT was noninferior to intravenous alteplase when administered within 4.5 hours of stroke onset for the primary outcome of excellent functional outcome at 90 days. More early neurological deterioration and bleeding events occurred in the alteplase group. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups regarding other secondary outcomes and subgroup analyses.

The PRISMS study was the first randomized multicenter trial, to the authors’ knowledge, to investigate the effect of intravenous alteplase vs single antiplatelet therapy in patients presenting with acute minor ischemic stroke,7 but the trial was inconclusive due to early study termination. Based on this result, intravenous alteplase is not recommended for minor nondisabling stroke according to current guidelines.1,2 However, a subgroup analysis of patients with minor ischemic stroke showed the superiority of intravenous alteplase compared with standard medical treatment in the IST-3 randomized trial.13 Furthermore, there was an increasing proportion of these patients receiving thrombolytic therapy in routine clinical practice,14,15 although the ratio of minor nondisabling vs disabling stroke was uncertain. Because it can be challenging for stroke physicians to decide whether to prescribe intravenous alteplase in patients with minor nondisabling stroke, it was important to investigate whether intravenous alteplase should be administered for minor nondisabling stroke.

The ARAMIS study was the first study to attempt to address this issue with a strategy different from the PRISMS study.7 A combination of aspirin plus clopidogrel (a loading dose of 300 mg) was administered for 12 (±2) days, followed by guideline-based antiplatelet treatment until 90 days in the current trial, whereas aspirin, 325 mg, alone was used for 90 days in the PRISMS study. The choice of DAPT was based on the CHANCE8 and POINT9 studies, which demonstrated the superiority of DAPT to aspirin alone in acute minor stroke. The 12 (±2) days of DAPT was based on the CHANCE trial, suggesting that the benefit of DAPT was offset by the potential risk of bleeding events approximately at the 10th day.10 Collectively, this trial demonstrated that short-term DAPT (12 [±2] days) initiated in patients presenting within 4.5 hours of a nondisabling minor stroke had noninferior efficacy to intravenous alteplase on 90-day functional outcome with less bleeding risk. In this trial, the percentage of patients with excellent functional outcome (91.5% vs 93.7%) was higher than that achieved in the PRISMS study (78.2% vs 81.5%),7 which may partially be attributed to the different percentage of Asian patients included (100% vs 0.3%), differing comorbidities, or vascular risk factor profile. Moreover, 2 studies reported a comparable percentage of excellent outcome among Chinese patients with minor stroke (87%-89.4%).12,16 In addition, in the subgroup with NIHSS scores greater than 3, the point estimate for the primary outcome of excellent functional outcome favored the alteplase group over the DAPT group, although this was not statistically significant. The potential benefit of alteplase in this population warrants further investigation.

In the secondary outcomes, compared with DAPT, there was more early neurological deterioration (9.1%) in patients receiving alteplase, which was comparable to a recent study that reported 13.3% early neurological deterioration in Chinese patients with mild stroke after intravenous alteplase.17 This could be related to thrombus progression or stroke reoccurrence due to the lack of an antithrombotic treatment effect within 24 hours after alteplase, considering its short half-life. In contrast, greater early neurological recovery was found in the alteplase vs DAPT group in the per-protocol and as-treated analyses, but this effect was lost in the full analysis set. The lost effect may be due to more patients who started receiving DAPT in the alteplase group vs patients in the DAPT group who started receiving alteplase in the full analysis set, which may have weakened the potential benefit of alteplase on early neurological improvement. Collectively, these results may suggest the possible benefit of alteplase on early neurological improvement. There were no significant differences between the groups in the other secondary outcomes, such as recurrent stroke. Given the benefit of DAPT in minor stroke,8,9 the lack of effect on recurrent stroke may be attributed to the relatively small sample and low rate of recurrent stroke in this population. The lack of an a priori plan for multiple comparisons of secondary outcomes precludes firm conclusions, and these findings should be interpreted with caution.

For the safety outcomes, compared with the DAPT group, there were numerically more instances of sICH and significantly more bleeding events in the alteplase group, which was expected given the known higher rate of hemorrhage with alteplase. The 0.9% rate of sICH with alteplase in this study was comparable to other studies of Chinese patients with minor stroke who were treated with alteplase (0%-1.0%).18,19

The strengths of this randomized trial were its large sample size, multicenter recruitment, and dual antiplatelet strategy, which enhances the generalizability of the results. Age, sex, medical history, time from onset of symptoms to treatment, and presumed stroke cause in the trial were similar to routine clinical practice.12 The results were confirmed in various sensitivity analyses. This finding, along with better safety outcomes, provides robust evidence for the effectiveness of DAPT being noninferior to intravenous alteplase in patients with minor nondisabling acute ischemic stroke.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the noninferiority design of the trial may be a main limitation due to DAPT as a standard treatment in this target population according to the current guidelines,1,2 which were published after patient enrollment began for this trial. The 2018 American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guideline and the 2020 Chinese Stroke Association guidelines stated that in patients with mild nondisabling AIS within 3 hours of symptom onset, intravenous alteplase may be considered.3,20 However, in this target population of patients with minor nondisabling stroke, the uncertain benefit of DAPT on 90-day mRS score,8,9 inconclusive evidence of intravenous alteplase,7 and increasing percentage of patients receiving alteplase14,15 render the current noninferiority design important to inform the best treatment. Second, there was a high crossover rate (20.4%) in this trial, which may have compromised the integrity of the recruitment and consent process and clinical equipoise. However, the demonstration of the noninferiority of DAPT to intravenous alteplase was robust given the concordance of findings by the full analysis set, per-protocol and as-treated analyses, and various sensitivity analyses. Third, the lack of vessel imaging data in some patients makes the subgroup analysis of etiology (large artery atherosclerosis vs small artery occlusion) and large artery occlusion (yes vs no) less powerful, because previous studies showed the possible benefit of alteplase or tenecteplase in patients with mild stroke with large artery atherosclerosis or large artery occlusion,21,22,23 which will be further assessed in the TEMPO-2 trial (NCT02398656) comparing tenecteplase vs standard of care in patients with minor stroke with a confirmed large vessel occlusion. Fourth, this trial was an open-label design; blinded end point evaluations were used to reduce bias in the assessment of the primary end point. For secondary end points, the neurologist who was unblinded to the treatment assessment conducted the early neurological assessment, which may have led to assessment bias for the early neurological outcomes. Fifth, patients with possible cardioembolism were excluded and a lower percentage of women than men were enrolled in this trial, which may affect the generalizability of the findings from this study. Sixth, high rates of the primary end point in the DAPT and alteplase groups may have created a ceiling effect that limited the opportunity for either agent to show superiority to the other. Seventh, further confirmation of the findings outside China may be needed, given the differences in etiology of ischemic stroke in other populations.

Conclusions

Among patients presenting with minor nondisabling acute ischemic stroke within 4.5 hours of symptom onset, dual antiplatelet treatment was noninferior to intravenous alteplase with regard to excellent functional outcome at 90 days.

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eAppendix

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2019;50(12):e344-e418. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berge E, Whiteley W, Audebert H, et al. European Stroke Organisation (ESO) guidelines on intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. Eur Stroke J. 2021;6(1):I-LXII. doi: 10.1177/2396987321989865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu L, Chen W, Zhou H, et al. ; Chinese Stroke Association Stroke Council Guideline Writing Committee . Chinese Stroke Association guidelines for clinical management of cerebrovascular disorders: executive summary and 2019 update of clinical management of ischaemic cerebrovascular diseases. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2020;5(2):159-176. doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saber H, Saver JL. Distributional validity and prognostic power of the national institutes of health stroke scale in US administrative claims data. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(5):606-612. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong Y, Gu H, Zhao XQ, et al. Clinical characteristics and in-hospital outcomes of varying definitions of minor stroke: from a large-scale nation-wide longitudinal registry. Stroke. 2021;52(4):1253-1258. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demaerschalk BM, Kleindorfer DO, Adeoye OM, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention . Scientific rationale for the inclusion and exclusion criteria for intravenous alteplase in acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2016;47(2):581-641. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khatri P, Kleindorfer DO, Devlin T, et al. ; PRISMS Investigators . Effect of alteplase vs aspirin on functional outcome for patients with acute ischemic stroke and minor nondisabling neurologic deficits: the PRISMS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(2):156-166. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.8496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. ; CHANCE Investigators . Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):11-19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. ; Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators . Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):215-225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan Y, Jing J, Chen W, et al. ; CHANCE investigators . Risks and benefits of clopidogrel-aspirin in minor stroke or TIA: time course analysis of CHANCE. Neurology. 2017;88(20):1906-1911. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang XH, Tao L, Zhou ZH, Li XQ, Chen HS. Antiplatelet vs R-tPA for acute mild ischemic stroke: a prospective, random, and open label multi-center study. Int J Stroke. 2019;14(6):658-663. doi: 10.1177/1747493019832998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Li X, Xu Y, et al. ; INTRECIS Investigators . Effectiveness of intravenous r-tPA versus UK for acute ischaemic stroke: a nationwide prospective Chinese registry study. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2021;6(4):603-609. doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khatri P, Tayama D, Cohen G, et al. ; PRISMS and IST-3 Collaborative Groups . Effect of intravenous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator in patients with mild stroke in the Third International Stroke Trial-3: post hoc analysis. Stroke. 2015;46(8):2325-2327. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asdaghi N, Wang K, Ciliberti-Vargas MA, et al. ; FL-PR CReSD Investigators and Collaborators . Predictors of thrombolysis administration in mild stroke: Florida-Puerto Rico Collaboration to Reduce Stroke Disparities. Stroke. 2018;49(3):638-645. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saber H, Khatibi K, Szeder V, et al. Reperfusion therapy frequency and outcomes in mild ischemic stroke in the United States. Stroke. 2020;51(11):3241-3249. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang P, Zhou M, Pan Y, et al. ; CHANCE investigators . Comparison of outcome of patients with acute minor ischaemic stroke treated with intravenous t-PA, DAPT or aspirin. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2021;6(2):187-193. doi: 10.1136/svn-2019-000319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang H, Yan S, Wu C, Zhang Y. Characteristics and outcomes of intravenous thrombolysis in mild ischemic stroke patients. Front Neurol. 2021;12:744909. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.744909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao G, Lin F, Wang Z, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy after intravenous thrombolysis for acute minor ischemic stroke. Eur Neurol. 2019;82(4-6):93-98. doi: 10.1159/000505241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lan L, Rong X, Shen Q, et al. Effect of alteplase versus aspirin plus clopidogrel in acute minor stroke. Int J Neurosci. 2020;130(9):857-864. doi: 10.1080/00207454.2019.1707822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council . 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heldner MR, Chaloulos-Iakovidis P, Panos L, et al. Outcome of patients with large vessel occlusion in the anterior circulation and low NIHSS score. J Neurol. 2020;267(6):1651-1662. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-09744-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang D, Zhang L, Hu X, et al. Intravenous thrombolysis benefits mild stroke patients with large-artery atherosclerosis but no tandem steno-occlusion. Front Neurol. 2020;11:340. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coutts SB, Dubuc V, Mandzia J, et al. ; TEMPO-1 Investigators . Tenecteplase-tissue-type plasminogen activator evaluation for minor ischemic stroke with proven occlusion. Stroke. 2015;46(3):769-774. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol

Statistical analysis plan

eAppendix

Nonauthor collaborators

Data sharing statement