Abstract

This study uses National Institutes of Health RePORTER data for mentored K awards and R01-equivalent grants to all departments in US schools of medicine to characterize K-award distribution and K-to-R transition by gender and department between 1997 and 2021.

The number of biomedical scientists declined between 2012 and 2015.1 Although gender diversity is important for health care innovation,2 women are underrepresented among biomedical scientists.3 Medical schools receive a large proportion of National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding, with variability between departments.4 The transition from NIH mentored career development (K) awards to independent investigator-initiated (R) awards is an important career junction for biomedical scientists that predicts success.1 This study characterizes K-award distribution and K-to-R transition by gender and department between 1997 and 2021.

Methods

Publicly available data were queried from the NIH RePORTER for mentored K awards and R01-equivalent grants from 1997 to 2021 to all departments in schools of medicine (Supplement 1). Investigator gender was inferred based on the pronouns or photograph from their professional profiles.5 Departmental gender composition was retrieved from the Association of American Medical Colleges Faculty Roster.6 K-award distribution by gender and department was limited to 1997 to 2011 to allow 10 years of follow-up, but data from 2012 to 2021 are presented to evaluate differences over time. In addition, to account for changes in gender composition, linear regression was used to calculate annual percent change in representation of women among K awardees and departmental faculty from 1997 to 2021.

χ2 Tests were used to describe K-to-R transition rates within 10 years of K-award receipt by gender and department. Modified Poisson regression was used to estimate the relative risk of K-to-R transition by gender, adjusting for institutional NIH funding rank. This study was deemed exempt by the Yale institutional review board. Statistical significance was 2-sided with P < .05. Analyses were performed using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Between 1997 and 2011, 6786 K awards were awarded to faculty in schools of medicine, with 2887 (42.54%) to women. Most K awards were awarded to internal medicine (36.10%), nonclinical departments (17.70%), psychiatry (11.80%), and pediatrics (10.30%) (Table). Between 2012 and 2021, an additional 5547 K awards were awarded, with 1881 (33.91%) to women and similar distribution across departments (internal medicine, 32.13%; nonclinical departments, 22.99%; psychiatry, 9.57%; and pediatrics, 9.68%).

Table. Distribution of National Institutes of Health Mentored Faculty K Awards, R01-Equivalent Awards, and K-to-R Transition Rates by Gender and Department at Schools of Medicine, 1997-2011.

| Departments | K awards | R01-equivalent awards | 10-y K-to-R transition rate, % | P valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of awardees | Women awardees, No. (%) | No. of awardees | Women awardees, No. (%) | Overall | Women | ||

| All departments | 6786 | 2887 (42.53) | 2706 | 1089 (40.24) | 39.88 | 37.72 | .002 |

| Anesthesiology | 99 | 29 (29.29) | 38 | 13 (34.21) | 38.38 | 44.82 | .39 |

| Dermatology | 71 | 29 (40.85) | 35 | 16 (44.44) | 50.70 | 55.17 | .53 |

| Emergency medicine | 36 | 6 (16.67) | 15 | 2 (13.33) | 41.66 | 33.30 | .65 |

| Family medicine | 94 | 50 (53.19) | 25 | 15 (60) | 26.59 | 30.00 | .42 |

| Internal medicine | 2451 | 1006 (41.04) | 1014 | 386 (38.06) | 41.37 | 38.36 | .01 |

| Neurology | 354 | 126 (35.31) | 151 | 54 (35.76) | 42.65 | 42.85 | .95 |

| Nonclinical | 1199 | 557 (46.46) | 475 | 203 (42.73) | 39.61 | 36.44 | .03 |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 81 | 57 (70.37) | 27 | 20 (74.07) | 33.33 | 35.08 | .60 |

| Pathology | 253 | 90 (35.57) | 112 | 39 (34.82) | 44.26 | 43.33 | .82 |

| Pediatrics | 702 | 360 (51.28) | 228 | 115 (50.43) | 32.47 | 31.94 | .75 |

| Psychiatry | 802 | 402 (50.12) | 337 | 169 (50.14) | 42.01 | 42.03 | .99 |

| Radiology | 107 | 34 (31.78) | 46 | 14 (30.43) | 42.99 | 41.17 | .79 |

| Surgery | 537 | 141 (26.26) | 202 | 43 (21.28) | 37.61 | 30.49 | .04 |

By χ2test for comparison between women and men K-to-R transition rates.

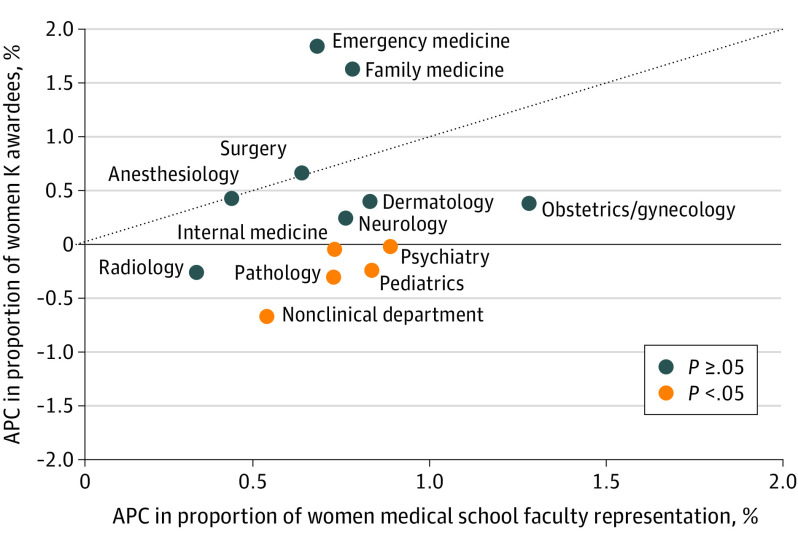

Between 1997 and 2011, gender distribution of K awards varied by department, with obstetrics and gynecology having the highest percentage of women recipients (57/81 [70.37%]) and emergency medicine the lowest (6/36 [16.67%]) (Table). Between 1997 and 2021, the annual percent change of women K awardees was significantly less than the annual percent change in women faculty representation in 5 of 13 departments, including internal medicine (−0.04% vs 0.73%; P = .001), pathology (−0.30% vs 0.72%; P = .01), pediatrics (−0.24% vs 0.83%; P = .002), psychiatry (−0.04% vs 0.89%; P < .001), and nonclinical departments (−0.65% vs 0.54%; P < .001) (Figure).

Figure. Annual Percent Change in Gender Distribution Among Departments and National Institutes of Health Mentored K Awardees, 1997-2021.

Dotted line indicates a line of identity where the annual percent change (APC) in proportion of women K awardees is equivalent to the APC in women representation in the department. F statistics were computed to determine significance in APC in women representation among K awardees and departmental faculty.

Between 1997 and 2021, there were 2706 R01-equivalent awards, with 1089 (40.24%) awarded to women. The 10-year K-to-R transition rate was 39.87% overall; 37.72% among women vs 41.47% among men (P = .002). After adjusting for institutional NIH funding rank, the relative risk was 0.91 (95% CI, 0.85-0.96) for women compared with men. The K-to-R transition rate varied across departments, with dermatology having the highest rate (36/71 [50.70%]) and family medicine the lowest (25/94 [26.59%]). The K-to-R transition rate was higher among men than women in surgery (40.15% for men vs 30.49% for women; difference, 9.66% [95% CI, 0.60%-18.6%]; P = .04), nonclinical departments (42.36% for men vs 36.44% for women; difference, 5.92% [95% CI, 0.4%-11.45%]; P = .03), and internal medicine (43.46% for men vs 38.36% for women; difference, 5.10% [95% CI, 1.15%-9.03%]; P = .01) (Table). Other departmental differences in K-to-R transition rates by gender were not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this study, the annual increase in women receiving K awards between 1997 and 2021 was less than the annual increase in women faculty in more than one-third of departments. Furthermore, K-to-R transition rates varied across departments, but most had statistically nonsignificant differences in transition rates for women and men.

Study limitations include the age of the data on K awards, although gender and department distributions were similar in later years, and the lack of information about faculty’s other demographic information, such as faculty track and race and ethnicity,3 or the number of grants submitted for review by gender or department, which may influence K-to-R transition rates. Greater support and mentorship for women faculty to obtain K awards and, in certain departments, to transition to R awards are needed.

Section Editors: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor; Kristin Walter, MD, Senior Editor.

eMethods

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Yin HL, Gabrilove J, Jackson R, Sweeney C, Fair AM, Toto R; Clinical and Translational Science Award “Mentored to Independent Investigator” Working Group Committee . Sustaining the clinical and translational research workforce: training and empowering the next generation of investigators. Acad Med. 2015;90(7):861-865. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofstra B, Kulkarni VV, Munoz-Najar Galvez S, He B, Jurafsky D, McFarland DA. The diversity-innovation paradox in science. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9284-9291. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915378117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen M, Chaudhry SI, Desai MM, Dzirasa K, Cavazos JE, Boatright D. Gender, racial, and ethnic and inequities in receipt of multiple National Institutes of Health research project grants. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(2):e230855. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roskoski R Jr. Trends in NIH funding to medical schools in 2011 and 2020. Acad Med. 2023;98(1):67-74. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver JK, Ghalib R, Poorman JA, et al. Analysis of gender equity in leadership of physician-focused medical specialty societies, 2008-2017. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):433-435. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association of American Medical Colleges . AAMC faculty roster. Accessed June 2022. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/faculty-institutions/report/faculty-roster-us-medical-school-faculty

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement