Abstract

Objectives

To document the terminology patients hear during the treatment course for a nonviable pregnancy, and to ask patients their perceived clarity and preference of terminology in order to identify a patient-centered lexicon..

Methods

We performed a preplanned sub-study survey of English-speaking participants in New York, Pennsylvania, and California, at the time of enrollment in a randomized multi-site trial of medical management of first-trimester early pregnancy loss. The six-item survey, administered on paper or electronic tablet, was developed and piloted for internal and external validity. We utilized a visual analog scale and quantified tests of associations between participant characteristics and survey responses using risk ratios.

Results

We approached 155 English-speaking participants in the parent study, of which 145 (93.5%) participated. In the process of receiving their diagnosis from a clinician, participants reported hearing the terms miscarriage (n=109, 75.2%) and early pregnancy loss (n=73, 50.3%) more than early pregnancy failure (n=31, 21.3%) and spontaneous abortion (n=21, 14.4%). The majority selected miscarriage (n= 79, 54.5%) followed by early pregnancy loss [n= 49, 33.8%] as their preferred term. In multivariable models controlling for study site, ethnicity, race, history of induced abortion, and whether the current pregnancy was planned, women indicated that spontaneous abortion and early pregnancy failure were significantly less clear than early pregnancy loss (53/145, aRR 0.12, 95% CI 0.07–0.19, and 92/145, aRR 0.38, 95% CI 0.24–0.61, respectively, as compared to 118/145 for early pregnancy loss). Miscarriage scored similarly to early pregnancy loss in clarity (119/145 aRR 1.05, 95% CI 0.62–1.77).

Conclusion

The terminology used to communicate “nonviable pregnancy in the first trimester” is highly variable. In this cohort of women, most preferred the term miscarriage, and classified both miscarriage and early pregnancy loss as clear labels for a nonviable pregnancy. Health care providers can use these terms to enhance patient-clinician communication.

PRECIS

Miscarriage and early pregnancy loss are the clearest terms when diagnosing and managing early pregnancy demise, and are preferred over spontaneous abortion and early pregnancy failure.

Introduction

First-trimester pregnancy demise is a common experience, occurring approximately one million times annually in the United States alone.1 Satisfaction with clinical care in this context is driven by patients’ perception that the health care team is sensitive and compassionate and by effective two-way communication.2–4 The language used to describe a nonviable pregnancy is varied. In the 1980s, the published medical literature transitioned from using spontaneous abortion to miscarriage,5 however shifts in the terminology used clinically are not well documented. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ (ACOG) Practice Bulletin entitled Early Pregnancy Loss states that “[i]n the first trimester, the terms miscarriage, spontaneous abortion, and early pregnancy loss are used interchangeably, and there is no consensus on the terminology in the literature.”6 Ultimately the ACOG Practice Bulletin utilizes the phrase Early Pregnancy Loss. The ACOG reVITALize gynecology terminology selects the phrase “Miscarriage/Intrauterine Pregnancy Loss” defined as “loss of a documented intrauterine pregnancy” and defines an early miscarriage as one that occurs prior to 10 weeks gestation.7 Given this variability, it is not surprising that qualitative studies have identified patient dissatisfaction with provider communication at the time of loss diagnosis as an area for quality improvement.8,9

The lack of consensus surrounding the terminology provides an opportunity to engage patients and identify language that enhances patient-clinician communication.10 In order to gain insight into the patient experience with the language of first trimester pregnancy demise, we surveyed women participating in a multisite randomized trial of medical management of early pregnancy loss.

Materials and Methods

This language preference cross-sectional study was a sub-study embedded within a randomized trial of medical management of early pregnancy loss conducted from May 2014 to May 2017 at three sites: University of Pennsylvania, University of California, Davis, and Albert Einstein College of Medicine. The primary results of this trial are published elsewhere, and included clinically stable women diagnosed with a nonviable pregnancy between 5 and 12 completed weeks of gestation.11 This language preference survey was developed and implemented as a protocol modification after the larger trial had already begun enrollment. We constructed a six-item instrument to assess participant terminology preferences. All data were collected as part of the clinical trial using REDCap, and all demographic data were obtained from the primary study.

We pretested our survey for external validity with 12 voluntary participants approached in the waiting room of a family planning clinic, half pregnant and half not pregnant, but none with a known diagnosis of an abnormal pregnancy. We then performed pilot test for internal validity within the PreFair trial on 23 participants, which allowed us to make our ultimate modifications. All English-speaking trial participants enrolled between November 2015 and May 2017 received the language preference survey. All participants provided written informed consent as part of the larger trial. The institutional review boards of participating sites approved this study and survey language.

We chose to query participants about the terms spontaneous abortion, miscarriage, early pregnancy loss, and early pregnancy failure, since the first three are referenced as interchangeable terms by the ACOG practice bulletin, and the fourth term, early pregnancy failure, is often used in medical literature. 6,7,12

We asked all participants to report which of these terms they heard during their clinical encounters for this pregnancy. We additionally asked, “What word would you prefer your doctors use to describe your diagnosis?”: spontaneous abortion, miscarriage, early pregnancy loss, and early pregnancy failure and to score these four terms on a 100-mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) from “least clear” to “most clear”. The visual analog scale has been shown to be a valid scale type for assessing patient satisfaction,13 and can discern subtler distinctions than an ordinal scale.14,15,16 However, when the distribution of the VAS measures for clarity were evaluated, they were bimodal (responses clustered at the low end of the scale “least clear” and the high end “most clear”). We then derived a new dichotomous clarity variable for each term where the term was 0 if the VAS score was <50 and 1 when clarity score was >= 50mm. A score >50mm on the visual analog scale was considered to be clear. Descriptive statistics were performed with ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. We tested associations between terms heard and demographic characteristics. Separate models were developed for clarity and preferred term with early pregnancy loss considered as the reference based on the ACOG’s use of the term in the most recent Practice Bulletin.6 All multivariable models employed a backwards stepwise approach of all baseline variables identified as associated with the outcome from bivariate tests of association. For the analysis of preferred term, a multivariable multinomial logistic regression model was developed in order to determine if terminology preferences varied depending on demographic characteristics. The 4 women who indicated that their preferred term was spontaneous abortion could not be included in this analysis as this group’s size was too small. Clarity for each term (0 versus 1) was modeled jointly using a generalization of the logistic regression model which accounts for the correlation among responses within individuals using a generalized estimating equation approach (GEE) using the xtgee command in Stata (version 14.2).

Results

We received completed surveys from 145 of 155 approached patients at the 3 sites for a total response rate of 93.5%. The mean age of participants was 30.3±6.1 years and the majority of respondents self-identified as Black–African American or White (n=65, 44.8% and n=62, 42.7%, respectively). Fifty-two (35.9%) participants self-identified as Hispanic or Latina (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographics by term preferred for non-viable pregnancy diagnosis

| Characteristic | All Respondents Mean±SD or N (%) | Spontaneous Abortion* Mean±SD or N (%) | Miscarriage Mean±SD or N (%) | Early Pregnancy Loss Mean±SD or N (%) | Early Pregnancy Failure Mean±SD or N (%) | None of the Above Mean±SD or N (%) | P † |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N=145 | N=4 (2.8) | N=79 (54.5) | N=49 (33.8) | N=11 (6.9) | N=2 (1.4) | ||

| Age (y) | 30.3±6.1 | 31.3±5.1 | 30.8±6.0 | 29.9±6.4 | 28.7±6.8 | 28±0.0 | 0.217 |

| Race | 0.058 | ||||||

| White | 62 (42.8) | 2 (50.0) | 40 (50.6) | 17 (34.6) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Black or African-American | 65 (44.8) | 2 (50.0) | 26 (32.9) | 29 (59.2) | 7 (63.6) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Other | 18 (12.4) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (16.5) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic or Latina | 52 (35.9) | 2 (50.0) | 34 (43.0) | 10 (20.4) | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.024 |

| Insurance | 0.409 | ||||||

| Medicaid | 78 (53.8) | 4 (100.0) | 38 (48.1) | 26 (53.1) | 8 (72.7) | 2 (100.0) | |

| Private | 47 (32.4) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (36.7) | 17 (34.7) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 20 (13.8) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (15.2) | 6 (12.2) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Site | 0.001 | ||||||

| UPenn | 78 (53.8) | 1 (25.0) | 34 (43.0) | 38 (77.6) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (50.0) | |

| UC Davis | 24 (16.6) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (20.3) | 5 (10.2) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Einstein | 43 (29.7) | 3 (75.0) | 29 (36.7) | 6 (12.2) | 5 (45.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Level of Education13 | 0.340 | ||||||

| Some High School/High School Diploma/GED or Trade School |

89 (61.4) | 4 (100.0) | 45 (57.0) | 31 (63.3) | 7 (63.6) | 2 (100.0) | |

| Any College/College Graduate/Graduate or Professional School | 56 (38.6) | 0 (0.0) | 34 (43.0) | 18 (36.7) | 4 (36.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gravidity | 0.88 | ||||||

| 1 | 38 (26.2) | 0 (0.0) | 23 (29.1) | 13 (26.5) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 2+ | 106 (73.1) | 4 (100.0) | 55 (69.6) | 36 (73.5) | 9 (81.9) | 2 (100.0) | |

| Parity | 0.923 | ||||||

| 0 | 55 (37.9) | 1 (25.0) | 30 (38.0) | 20 (40.8) | 4 (36.4) | 0 (0) | |

| 1+ | 90 (62.1) | 3 (75.0) | 49 (62.0) | 29 (59.2) | 7 (63.6) | 2 (100) | |

| Prior Miscarriage | 0.136 | ||||||

| No | 98 (67.6) | 1 (25.0) | 51 (64.6) | 38 (77.6) | 7 (63.6) | 1 (50.0) | |

| Yes | 47 (32.4) | 3 (75.0) | 28 (35.4) | 11 (22.4) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (50) | |

| Prior Induced Abortion | 0.013 | ||||||

| No | 98 (67.6) | 0 (0.0) | 59 (74.7) | 31 (63.3) | 6 (54.5) | 2 (100.0) | |

| Yes | 47 (32.4) | 4 (100.0) | 20 (25.3) | 18 (36.7) | 5 (45.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gestational Age (weeks) | 10.6±2.9 | 9.7±3.1 | 10.8±3.1 | 10.4±2.8 | 9.7±2.0 | 9.8±1.5 | 0.302 |

| Planned Pregnancy | 0.174 | ||||||

| No | 73 (50.3) | 4 (100.0) | 37 (46.8) | 26 (53.1) | 6 (54.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Yes | 72 (49.7) | 0 (0.0) | 42 (53.2) | 23 (47.0) | 5 (45.5) | 2 (100.0) | |

Includes spontaneous, threatened, incomplete, and complete abortion

p-values determined by Fisher’s exact test or Type III Anova

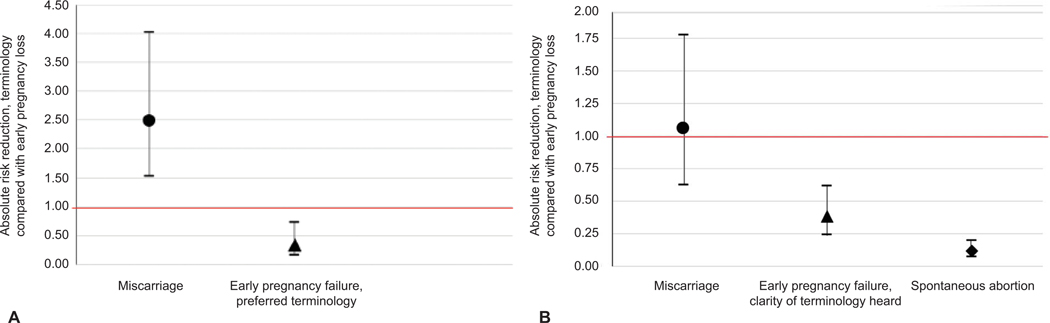

Participants most frequently chose miscarriage as their preferred diagnosis term (n=79, 54.5%) followed by early pregnancy loss (n=49, 33.8%), whereas fewer participants chose early pregnancy failure (n=11, 7.6%) or spontaneous abortion (n=4, 2.8%) (Figure 1a). The distribution of terminology preference (Table 1) varied significantly by ethnicity (p=0.02), study site (p=0.001), and history of induced abortion (p=0.01). Two participants chose “none of the above” when asked to select their preferred term and thus were excluded from the analysis. Neither of these participants offered a suggestion for alternative language. We found no differences in the distribution of preferred term by intendedness of the pregnancy (p=0.17) or gestational age of the current pregnancy (p=0.30). When compared with early pregnancy loss, early pregnancy failure was less preferred (11/145 versus 49/145 for early pregnancy loss, aRR=0.34, 95% CI 0.16–0.73, p<.006) and miscarriage was more preferred by participants (79/145, aRR=2.48, 95% CI 1.53–4.02, p<.001) after adjusting for site and ethnicity (Table 2). As only 4 participants (2.8%) chose spontaneous abortion as their preferred term and, due to this low frequency, we omitted this term from the multivariable model of preference.

Figure 1.

A. Preferred diagnosis terminology by women diagnosed with first-trimester nonviable pregnancy. Absolute risk reduction adjusted for study site and ethnicity. B. Clarity rankings of diagnosis terms by women diagnosed with first-trimester nonviable pregnancy. Clarity measured on a 100 mm visual analog scale and dichotomized such that >50 on visual analog scale is considered “clear.” Absolute risk reduction adjusted for site, ethnicity, race, prior induced abortions, and planned pregnancy.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic models for clarity and preferred terminology

| N (%) | RR | 95% CI | p-value | aRR* | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Clarity | |||||||

| Early Pregnancy Loss | 118 (81.4) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Spontaneous Abortion | 53 (36.6) | 0.132 | 0.083–0.209 | <0.001 | 0.119* | 0.073–0.193 | <0.001 |

| Miscarriage | 119 (82.1) | 1.047 | 0.629–1.745 | 0.859 | 1.048* | 0.621–1.773 | 0.858 |

| Early Pregnancy Failure | 92 (63.4) | 0.397 | 0.250–0.631 | <0.001 | 0.380* | 0.235–0.614 | <0.001 |

| Preferred Terminology | |||||||

| Early Pregnancy Loss | 49 (33.8) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Miscarriage | 79 (54.5) | 0.224 | 0.117–0.432 | <0.001 | 0.341† | 0.159–0.732 | 0.006 |

| Early Pregnancy Failure | 11 (7.6) | 1.612 | 1.129–2.303 | 0.009 | 2.478† | 1.529–4.016 | <0.001 |

Adjusted for Site, Ethnicity, Race, Prior Induced Abortions, Planned Pregnancy

Adjusted for Site and Ethnicity

Eighty-two percent of women found the term miscarriage (82.1%) to be clear followed closely by early pregnancy loss (81.4%), and early pregnancy failure (63.4%) with only 36.6% of women indicating the term spontaneous abortion was clear. [After controlling for potential confounders (study site, ethnicity, race, history of induced abortion, and whether the current pregnancy was planned), we found spontaneous abortion and early pregnancy failure to be significantly less clear than early pregnancy loss (53/145 aRR 0.12, 95% CI 0.07–0.19, p<0.0001 and 92/145 aRR 0.38, 95% CI 0.24–0.61, p<0.0001, respectively versus 118/145 for early pregnancy loss). Miscarriage scored similarly to early pregnancy loss in clarity rankings (119/145 aRR 1.05, 95% CI 0.62–1.77, p= 0.86) (Figure 1b, Table 2). 8

Individual participants heard multiple terms throughout their encounters for diagnosis. Patients most commonly heard the terms miscarriage (n=109, 75.2%), and early pregnancy loss (n=73, 50.3%). We did not find any 9anyastatistically significant differences in the bivariate analyses of participant demographic characteristics and terms most commonly heard. While participants did not hear the less preferred terms as frequently as the more preferred terms, 14.4% of participants heard spontaneous abortion (n=21) and 21.3% of participants heard the phrase early pregnancy failure (n=31) during their care.

Discussion

Miscarriage was found to be the most preferred of the four suggested terms when trial participants were asked to select a single term to label their diagnosis of a non-viable first trimester pregnancy. However, when asked to rate the clarity of each of the terms individually, there was no difference between miscarriage and early pregnancy loss, making both of these terms suitable for use. The terms spontaneous abortion and early pregnancy failure were classified as less clear and less preferred by patients, and thus should not be the first choice terminology.

Our data were collected as part of a clinical trial of women with first trimester pregnancy demise, which may limit generalizability. However, we included women from diverse geographic locations in the United States, and our population was socio-demographically varied. We included only women who self-identify as English-speaking, and results may be different for women who speak other languages. The complex nature of language and how women from different backgrounds understand words differently is highlighted by our finding that terminology preferences varied by race and ethnicity. While those who identified as Hispanic also preferred the terms miscarriage and early pregnancy loss overall, they were more likely than others to prefer the terms early pregnancy failure and spontaneous abortion. When adjusting for these differences, our findings show an overall superior clarity and patient preference for miscarriage and early pregnancy loss. Level of education did not significantly influence clarity level or language preference choice between these two terms so they can be used for women from a range of educational backgrounds.

The prevalence of unintended pregnancy was high in our sample and representative of the U.S. population.17 10We did not find differences in language preferences according to intendedness of the pregnancy. This finding is supported by a recent study that suggested that pregnancy loss can impact women in complex and seemingly contradictory ways regardless of original reactions to the pregnancy.18 Our univariate analysis did show differences in language preference among women who stated they had a history of induced abortion compared with those who did not. A prior study in a similar population showed that history of induced abortion influences women’s decision-making at the time of miscarriage treatment, both because the treatments for two conditions are similar and prior abortion experience provides a knowledge-base, and because some women wished to distance their miscarriage experience from their abortion experience.2 Our data did not suggest that women with a history of a prior miscarriage have unique language preferences.

Limitations of the study include that we did not identify the point of care at which each of these terms were heard, so it is possible that participants selected the two most clear and preferred terms because they were more familiar from their treatment course. Additionally, this study is limited by the fact that all data was self-reported by participants and there were no objective recordings or data reflecting what was actually said by clinicians.

Spontaneous abortion was the least commonly heard term, which is consistent with its diminishing use in the medical literature.5 The clinical meaning of abortion is “the spontaneous or induced termination of pregnancy before the fetus reaches a viable age,”19 but socio-political forces have co-opted the term to primarily infer induced abortion, which is accompanied by stigma that women with fetal demise may find additionally alienating.20

Our findings suggest that, of the currently used diagnosis terminology, both miscarriage and early pregnancy loss are acceptable, clear terms within our lexicon for discussing first trimester pregnancy demise with patients from a variety of backgrounds. Others have called for a shift in language choice to the use of miscarriage.21 Our data support that patients, too, prefer the term miscarriage to all other commonly used terms. However, given that just over fifty percent of participants chose miscarriage as the most preferred term, additional research to improve patient-centered communication is warranted. For now, clinicians and the systems that support clinical practice can improve communication by preferentially using the terms miscarriage and early pregnancy loss.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH R01-HD0719-20 and the Society of Family Planning Research Fund Midcareer Mentor Award (Schreiber).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal’s requirements for authorship.

Clinical Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02012491.

References

- 1.Jones RK, Kost K. Underreporting of induced and spontaneous abortion in the United States: an analysis of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Stud Fam Plann 2007;38:187–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schreiber CA, Chavez V, Whittaker PG, Ratcliffe SJ, Easley E, Barg FK. Treatment Decisions at the Time of Miscarriage Diagnosis. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:1347–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conversations Van P., coping, & connectedness: a qualitative study of women who have experienced involuntary pregnancy loss. Omega (Westport) 2012;65:71–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Layne LL. Pregnancy and infant loss support: a new, feminist, American, patient movement? Soc Sci Med 2006;62:602–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moscrop A ‘Miscarriage or abortion?’ Understanding the medical language of pregnancy loss in Britain; a historical perspective. Med Humanit 2013;39:98–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Early pregnancy loss. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 200. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002899. Epub 2018 August 29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharp HT, Johnson JV, Lemieux LA, Currigan SM. Executive summary of the reVITALize initiative: standardizing gynecologic data definitions. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129:603–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong MK, Crawford TJ, Gask L, Grinyer A. A qualitative investigation into women’s experience after a miscarriage: implications for the primary healthcare team. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:697–702. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radford EJ, Hughes M. Women’s experiences of early miscarriage: implications for nursing care. J Clin Nurs 2015;24:1457–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pieterse AH, Jager NA, Smets EM, Henselmans I. Lay understanding of common medical terminology in oncology. Psychooncology 2013;22:1186–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreiber CA, Creinin MD, Atrio J, Sonalkar S, Ratcliffe SJ, Barnhart KT. Mifepristone Pretreatment for the Medical Management of Early Pregnancy Loss. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2161–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnhart KT. Early pregnancy failure: beware the pitfalls of modern management. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:1061–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Voutilainen A, Pitkaaho T, Kvist T, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. How to ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vulnerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric Likert scale. J Adv Nurs 2015;72:946–957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reips UD, Funke F Interval-level measurement with visual analogue scales in Internet-based research: VAS Generator.Behavior Research Methods 2008; 40:699–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funke F, Rieps UD. Why Semantic Differentials in Web-Based Research Should Be Made from Visual Analogue Scales and not from 5-Point Scales. Field Methods. 2012; 24; 310–327. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Couper MP, Tourangeau R, Conrad FG, Singer E. Evaluating the effectiveness of visual analog scales: A Web experiment. Social Science Computer Review. 2006;24:227–245. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flink-Bochacki R, Hamm ME, Borrero S, Chen BA, Achilles SL, Chang JC. Family Planning and Counseling Desires of Women Who Have Experienced Miscarriage. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venes D, Taber CW. Taber’s Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary, 23rd ed. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodroffe C Miscarriage or abortion. Lancet 1985;326:1245. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutchon DJR. Understanding miscarriage or insensitive abortion: Time for more defined terminology? Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179:397–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.