Abstract

Purpose: To explore the diagnostic value and the prognostic significance of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination by flow cytometry (FC) in children with central nervous system leukemia (CNSL). Method: This is a retrospective observational study. We select 986 pediatric patients with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia from January 2012 to December 2018 as the research objects and analyze the sensitivity and specificity of different methods for diagnosing CNSL. The recurrence rate and survival rate of CNSL in different groups were compared. Results: Among the 986 cases, 31 cases (positive rate of 3.14%) were positive by FC, and the cytospin-based cytomorphology (CC) test was positive in 6 cases (positive rate of 0.61%). CC combined with FC might improve the diagnostic sensitivity (from 30% to 65%, 𝑥2 value was 5.143, P = .016). The 2-year event-free survival (EFS) of 31 FC + children was 59.5% ± 9.2%, and that of 955 FC − children was 74.1% ± 1.8% (P = .004). The 2-year overall survival (OS) of the 2 groups were 63.6% ± 9.7% and 80.2% ± 1.5%, respectively (P = .004). In order to exclude the influence of CNSL, we divided the patients into 3 groups: CNSL group and non-CNSL group with CSF FC + , FC − group. There was no significant difference in EFS between FC − group and non-CNSL group with FC + (2-year EFS were 74.1% ± 1.8% and 68.7% ± 9.8%, respectively, P = .142), and there was a significant difference in OS (2-year OS were 80.2% ± 1.5% and 67.5% ± 10.3%, respectively, P = .029). Conclusion: The test of FC combined with CC may improve the diagnostic sensitivity of CNSL. The EFS and OS of children with FC + are worse than those of children with FC −. However, for those patients with non-CNSL, but only FC + at the initial diagnosis, the EFS is not significantly affected by strengthening systemic chemotherapy and increasing the number of intrathecal injections.

Keywords: flow cytometry, cerebrospinal fluid, central nervous system leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, children

The frequency of central nervous system (CNS) involvement at initial diagnosis in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) ranges from 8% to 13%,1–3 and CNS involvement is one of the main reasons for treatment failure. Currently, targeted therapy for CNS leukemia (CNSL) includes intrathecal chemotherapy and systemic high-dose chemotherapy with or without cranial radiotherapy.4,5 However, CNS-directed therapy is associated with serious neurological side effects, including permanent cognitive and neuroendocrine defects.6,7 With the improvement of the cure rate of ALL, the long-term toxic effects of chemotherapeutic drugs and radiotherapy on the CNS and the life quality of pediatric patients have attracted attention. Therefore, how to diagnose and treat CNSL more accurately is particularly important. On the one hand, early detection of CNSL can ensure that children receive active and effective treatment in time, prevent the recurrence of CNSL, and improve the cure rate. On the other hand, accurate exclusion of CNS involvement helps to reduce the number of lumbar punctures and/or chemotherapy doses, weaken the toxicity of the nervous system, and to improve life quality.

The gold standard for the diagnosis of CNSL is to find leukemia cells by cytospin-based cytomorphology (CC) examination of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). 8 The specificity of this method is close to 100%. But due to changes in cell morphology in the process of centrifugation, preservation, and staining of CSF specimens and the small number of cells in CSF, the method is less sensitive. It will inevitably lead to the lack of timely diagnosis and treatment for some pediatric patients with CNSL, which will eventually lead to bone marrow and/or extramedullary recurrence. Previous studies have shown that more sensitive techniques such as multicolor flow cytometry (FC) can detect low levels of leukemia cells,9–11 but CC cannot. However, the diagnostic value and the prognostic significance of abnormal CSF detection by FC are still unclear. The purpose of this study is to investigate the clinical significance of CSF detection by FC in pediatric ALL.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

This is a retrospective observational study. A total of 986 pediatric patients with newly diagnosed ALL admitted to the Pediatrics Department of Peking University People's Hospital from January 2012 to December 2018 were selected as the subjects. The diagnosis and classification were based on the recommendations for diagnosis and treatment of pediatric ALL. 12 Acute mixed phenotype leukemia conforming to the diagnostic criteria of the European Collaborative Group on Immunological Typing of Leukemia (EGIL) 13 was excluded. The patients who did not receive regular chemotherapy at Peking University People's Hospital were not counted. We have de-identified all patient details. Diagnosis of CNSL: When any of the following conditions are met and other causes of CNS lesions are excluded, CNSL can be diagnosed: (1) white blood cell count (WBC) > 5 × 106/L and the presence of morphologically leukemia cells in the CSF; (2) symptoms of cranial nerve paralysis; (3) there are brain or meningeal lesions and spinal meningeal lesions in imaging examinations (computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging). 12 We have de-identified all patient details.

Treatment

Risk stratification was made according to the recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric ALL. 12 The chemotherapy regimen was a modified BFM95 regimen. Induction therapy adopted CODPL (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, dexamethasone or prednisone acetate, daunorubicin or idarubicin, L-asparaginase, or pegaspargase). Consolidation and intensive therapy used high-dose methotrexate, high-dose cytarabine, and other drugs sequentially and alternately. Re-induction therapy of the CODPL regimen is applied every 6 months or so, with a total of 2 courses. Maintenance therapy included oral mercaptopurine and intramuscular methotrexate. The total duration of treatment was 2.5 years for SR patients and 3 years for IR/HR patients. All patients received a triple intrathecal injection (Ara-c 30 mg/m2, maximum dose 40 sensitives; MTX 5 mg/time within 1 year old, 7.5 mg/time for 1-3 years old, 10 mg/time for 3-7 years old, 12.5 mg/time for >7 years old; dexamethasone < 1 year old, 2.5 mg/time, > = 1 year old, 5 mg/time) 20 to 25 times totally to prevent CNSL. For patients with confirmed CNSL or FC + in CSF, intensive triple intrathecal injection should be given including in the early period, intrathecal injection was given twice a week until the CSF returns to normal, and then once a week, at least 4 times, and totally 28 to 30 times during chemotherapy. There were 2 patients who received CNS radiation therapy. One was diagnosed as CNSL during induction chemotherapy and received CNS radiation therapy before bone marrow transplantation. So far, his bone marrow is in continuous remission and he has no extramedullary recurrence. Another one was diagnosed as CNSL during subsequent consolidation chemotherapy. His CSF was normal during induction chemotherapy, so he was classified into the FC− group in this article. He received CNS radiation therapy and obtained disease-free survival.

Collection and Examination of CSF

During induction chemotherapy, all patients underwent the first lumbar puncture after the peripheral blood blasts disappeared, and all patients had a simultaneous evaluation of CSF both by cytospin-based CC and FC. The fresh samples were processed within a few hours after collection. At least 2 mL CSF was required for FC analysis. Cells were concentrated by centrifugation (10 min, 300g), discarded supernatant, then labeled with antibody, incubated in the dark for 15 min, diluted with 10 times of hemolysin 1000 µL, protected from light for 8 min, then centrifuged (10 min, 300g), discarded supernatant, finally added with 300 µL of PBS. FC used an 8-color scheme. Different antibody combinations were selected according to the subtype of leukemia and the bone marrow immune phenotype at the time of onset. Routine antibody combinations of ALL-B included CD19, CD45, CD58, CD10, CD34, CD123, CD38, and CD20. The B cell lineages were identified by bidirectional gating with SSC/CD19 and CD45/CD19, and then by using other antigen combinations to see if CD19 + B cells are on a normal differentiation trajectory. Routine antibody combinations of ALL-T included CD2, CD45, CD56, CD99, CD34, CD5, CD7, and CD3. The T cell lineage was identified by bi-directionally gating with SSC/CD7 and CD45/CD7, (ensure that CD56 is negative to exclude NK cells) and then looking for abnormal cells according to the antigen at the time of onset. Flow-positive was defined as at least 10 abnormal cells with a leukemia-related phenotype that should be detected.

Efficacy Evaluation and Follow-Up

The evaluation of efficacy was based on the “Guidelines Insights: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Version 1.2019.” 14 CR was defined as active or markedly active myeloproliferation with <5% leukemia cells. Event-free survival (EFS) was defined as the period from the date of diagnosis to that of the first event (relapse, second tumor, death, or end of follow-up). Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time between the date of diagnosis and the date of death or the last follow-up. The follow-up cut-off date was May 1, 2020, and the median follow-up time was 48 (16-100) months.

Statistics

The reporting of this study conforms to STROBE guidelines. 15 SPSS 25.0 statistical software was used for data processing and analysis. The measurement data was expressed with median (range); the count data was shown by percentage (%), and the chi-square test was used to compare the rates. In the calculation process, if the expected count was between 1 and 5, the chi-square test needed continuity correction, and then the continuity correction result would be selected. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. P < .05 means the difference is statistically significant.

Results

General Features

Among the 986 patients, there were 881 cases of ALL-B and 105 cases of ALL-T. There were 578 males and 408 females. The median age at diagnosis was 6 (0.5-18) years old, and 31.03% of patients (306/986) were older than 10. The median white blood cell count of newly diagnosed patients was 12.6 (0.5-831.9) × 109/L, while 23.83% of patients (235/986) had the result ≥ 50 × 109/L (see Table 1 for details). The median time for the first lumbar puncture was the sixth day (4-11 days) of induction chemotherapy.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of 986 Children With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.

| Total number | ALL-B | ALL-T | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 986 | 881 (89.35%) | 105 (10.65%) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 578 (58.62%) | 504 57.21%) | 74 (70.48%) |

| Female | 408 (41.38%) | 377 (42.79%) | 31 (29.52%) |

| WBC, n (%) | |||

| ≥ 50 × 109/L | 235 (23.83%) | 170 (19.30%) | 65 (61.90%) |

| < 50 × 109/L | 751 (76.17%) | 711 (80.70%) | 40 (38.10%) |

| Age, n (%) | |||

| ≥ 10 | 306 (31.03%) | 258 (29.28% | 48 (45.71%) |

| < 10 | 680 (68.97%) | 623 (70.72%) | 57 (54.29%) |

| FC, n (%) | |||

| + | 31 (3.14%) | 25 (2.84%) | 6 (5.71%) |

| − | 955 (96.86%) | 856 (97.16%) | 99 (94.29%) |

Abbreviations: ALL-B, acute B-lymphocytic leukemia; ALL-T, acute T-lymphocytic leukemia; n, number of patients; %, percentage of patients in each part; WBC, white blood cell; FC, flow cytometry.

Sensitivity and Specificity of the Different Examinations of CSF

During induction chemotherapy, 20 cases (2.03%) were diagnosed as CNSL, including 5 cases with CC + alone, 12 cases with cranial nerve palsy alone, 2 cases with abnormal imaging, and 1 case with both CC + and cranial nerve palsy.

Among the 986 cases, 31 cases (3.14%) were CSF-positive by FC, out of which 8 cases were diagnosed as CNSL, and the diagnostic rate was 25.81%. 955 cases were CSF negative by FC, out of which 12 cases were diagnosed as CNSL, and the diagnostic rate was 1.26%. There was a statistical difference between the 2 rates (P = .000). The CSF CC test was positive in 6 cases (positive rate 0.61%). The sensitivity of the CC method was 30% and the specificity was 100%, while the sensitivity of the FC method was 40% and the specificity was 97.62%. The sensitivity of CC and/or FC was 65%, and the specificity was 97.62%. Using CC combined with FC can improve diagnostic sensitivity from 30% to 65%. The value of 𝑥2 was 5.143, the difference was statistical significance (P = .016) (see Tables 2 to 5 for details).

Table 2.

Sensitivity and Specificity of CC.

| CC | CNSL | Non-CNSL |

|---|---|---|

| + | 6 | 0 |

| − | 14 | 966 |

Abbreviations: CNSL, central nervous system leukemia; CC, cytospin-based cytomorphology.

Table 3.

Sensitivity and Specificity of FC.

| FC | CNSL | Non-CNSL |

|---|---|---|

| + | 8 | 23 |

| − | 12 | 943 |

Abbreviations: CNSL, central nervous system leukemia; FC, flow cytometry.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and Specificity of CC Combined FC.

| CC and/or FC | CNSL | Non-CNSL |

|---|---|---|

| + | 13 | 23 |

| − | 7 | 943 |

Abbreviations: CNSL, central nervous system leukemia; FC, flow cytometry; CC, cytospin-based cytomorphology.

Table 5.

Comparison of Sensitivity Between CC and CC Combined FC.

| CC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | Total | ||

| FC and/or CC | + | 6 | 7 | 13 |

| − | 0 | 7 | 7 | |

| Total | 6 | 14 | 20 | |

Abbreviations: FC, flow cytometry; CC, cytospin-based cytomorphology.

Kappa: 0.375, chi-square value 5.143, P = .016.

Recurrence Rate of CNSL

Out of the 986 patients, 31 cases were FC − positive in CSF, and the CNSL recurrence rate was 9.68% (3/31). For the remaining 955 patients with FC negative in CSF, the CNSL recurrence rate was 6.18% (59/955). There was no statistical difference (the chi-square value is 0.171, P = .679). Out of 966 children who were not diagnosed as CNSL at the initial diagnosis, 23 were FC positive and 943 were FC negative, and their recurrence rate of CNSL was 13.04% (3/23) and 6.26% (59/943), respectively. The former rate was higher than the latter, but the difference was not statistically significant (chi-square value 0.777, P = .378).

Among the 20 patients diagnosed with CNSL, 5 died from various causes (4 from bone marrow relapse and 1 from chemotherapy complications), and 15 had long-term survival without CNSL recurrence (7 of them underwent bone marrow transplantation). Among the FC + patients who were not diagnosed as CNSL, there were 3 cases of CNSL recurrence, including 2 cases of CNSL recurrence alone, and 1 case of bone marrow recurrence combined with CNSL recurrence, but they all survived for a long time. Among the FC − patients who were not diagnosed with CNSL, there were 59 cases of CNSL recurrence, the median recurrence period was 11 months (1 month to 87 months). In these cases, 12 patients had both bone marrow recurrence with CNSL recurrence at the same time, 5 patients experienced CNSL recurrence and then bone marrow recurrence, 1 patient had CNSL recurrence after bone marrow recurrence, and 41 cases of bone marrow leukemia recurrence alone. A total of 16 patients died and the remaining patients survived for a long time.

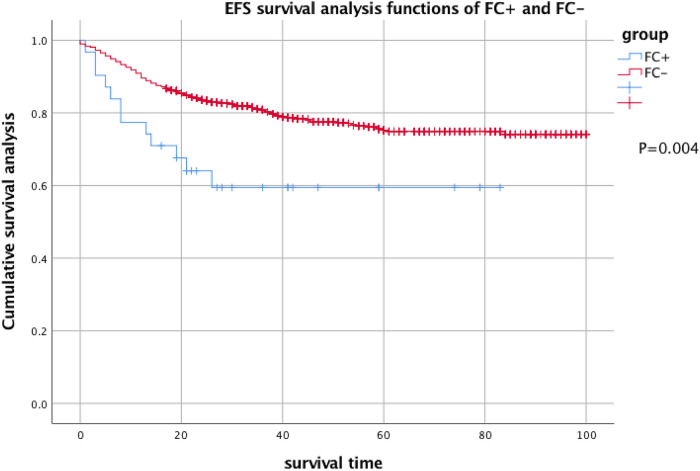

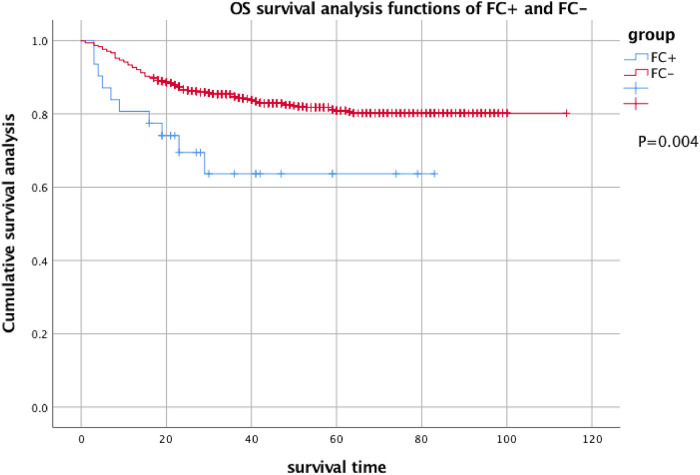

The Comparison of EFS and OS Between Different Groups

The 2-year EFS of 31 patients with FC + at the first CSF test was 59.5% ± 9.2%, and the 2-year EFS of 955 FC − patients was 74.1% ± 1.8%. There was a significant difference between the results (P = .004). The 2-year OS was 63.6% ± 9.7% and 80.2% ± 1.5%, respectively, and there was a significant difference between them (P = .004) (see Figures 1 and 2 for details).

Figure 1.

EFS analysis of FC + and FC− children with acute lymphocytic disease. Two-year EFS of FC + : 59.5% ± 9.2% and 2-year EFS of FC−: 74.1% ± 1.8%.

Abbreviations: EFS, event-free survival; FC, flow cytometry.

Figure 2.

OS analysis of FC + and FC− children with acute lymphocytic disease. Two-year OS of FC + : 63.6% ± 9.7% and 2-year OS of FC−: 80.2% ± 1.5%.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; FC, flow cytometry.

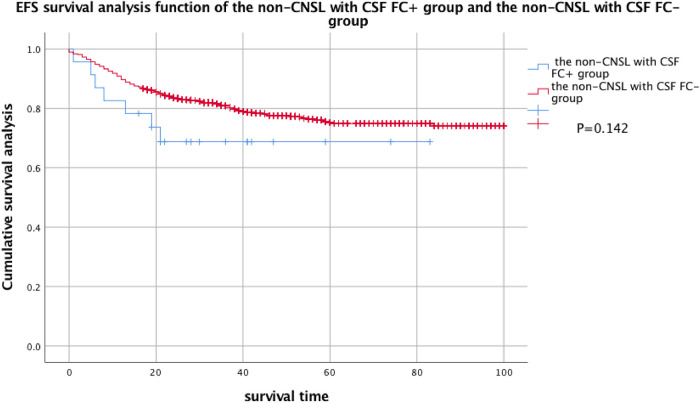

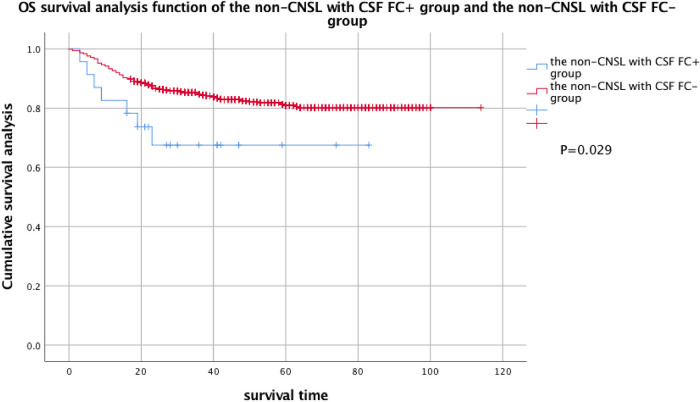

Considering that a large part of FC + pediatric patients were diagnosed with CNSL at the initial diagnosis, in order to exclude the influence of CNSL on EFS and OS, the patients were divided into CNSL FC + group, non-CNSL FC + group, and FC − group so as to compare the EFS and OS of these 3 groups. By comparison, there was no statistical difference in EFS between the FC − group and the non-CNSL FC + group, but there was a statistical difference in OS (see Figures 3 and 4 for details).

Figure 3.

EFS analysis of the non-CNSL with CSF FC + group and the non-CNSL with CSF FC− group. Two-year EFS of the non-CNSL with CSF FC + group: 68.7% ± 9.8% and 2-year EFS of the non-CNSL with CSF FC− group: 74.1% ± 1.8%.

Abbreviations: EFS, event-free survival; FC, flow cytometry; CNSL, central nervous system leukemia; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Figure 4.

OS analysis of the non-CNSL with CSF FC + group and the non-CNSL with CSF FC− group. Two-year OS of the non-CNSL with CSF FC + group: 67.5% ± 10.3% and 2-year OS of the non-CNSL with CSF FC− group: 80.2% ± 1.5%.

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; FC, flow cytometry; CNSL, central nervous system leukemia; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid.

Discussion

Currently, CNS involvement in all leukemia patients remains underdiagnosed, as demonstrated by autopsy findings of CNS infiltration in patients with leukemia limited to the bone marrow. 16 The rapid development of FC has enabled complex immunophenotype analysis of both normal and leukemic cells in the CSF. The current FC analysis could detect phenotypically abnormal cells with a sensitivity of at least 0.01% (1 target cell in 104 events). In this study, by introducing FC analysis, the detection ability of CSF tumor cells has been improved to a certain extent, and the evidence of CNS involvement in patients with ALL increased from 0.61% to 3.14%. The combination of CC and FC significantly improved the sensitivity of leukemic cell detection in CSF (from 30% to 65%, 𝑥2 value 5.143, P = .016, see Table 5), which is consistent with the findings of other studies.9,17,18 Therefore, FC combined with CC detection may be used as an effective detection method to detect early, asymptomatic CNS infiltration.

In our hospital, the FC positive rate in the first CSF test was 3.14%. Previous studies reported that 17% to 28% of patients with ALL were positive in CSF by FC. 19 In contrast, this rate in our center is lower than that in other studies, which may be related to the delay of lumbar puncture.

In terms of the recurrence rate of CNSL, there is no statistical difference between the FC + and FC − patients. Among the patients who were not diagnosed with CNSL, FC + patients had a higher recurrence rate than FC − patients, but the difference is not statistically significant, which may be due to the strengthening of triple intrathecal injection in patients with FC + in our department.

In this study, the CNSL diagnosis rate in CSF FC + patients was significantly higher than that in FC − patients, and there was a statistical difference. The EFS and OS of FC + patients were also lower than those with FC −, suggesting that detection of FC + in CSF was associated with CNS infiltration or poor prognosis, which should draw attention.

There were significant differences in EFS and OS between the FC − group and the FC + with CNSL group patients, suggesting that there was a significant prognostic value of CNSL diagnosis. Among patients not being diagnosed with CNSL, there was no statistical difference in EFS between the FC − group and the FC + group. It seems that the pure FC + of CSF at the initial diagnosis has little effect on the prognosis, but it may be due to the strengthening systemic chemotherapy and/or increasing the number of intrathecal injections. Therefore, large-scale, prospective studies are needed for further demonstration.

Limitations

The number of CC + was too small, resulting in low consistency between CC and FC results. Large-scale, prospective studies are needed for further demonstration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the combination examination of CSF by CC and FC may improve the diagnostic sensitivity of CNSL. The EFS and OS of the FC + patients were worse than those of the FC − patients. However, for the patients who were not diagnosed as CNSL but had FC positive in the CSF at the initial diagnosis, strengthening systemic chemotherapy and or increasing the number of intrathecal injections may improve their EFS. This research needs to be further confirmed by large-scale and prospective studies.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Statement: Approval was given by the Ethics Review Committee of Peking University People's Hospital (2023PHB054-001). This is a retrospective study and did not require additional collection of human specimens. There was no need to obtain consent from the patient’s parents.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article

ORCID iD: Lian Xue https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3095-6292

References

- 1.Schultz KR, Pullen DJ, Sather HN, et al. Risk- and response-based classification of childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a combined analysis of prognostic markers from the pediatric oncology group (POG) and children’s cancer group (CCG). Blood. 2007;109(3):926‐935. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-024729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winick N, Devidas M, Chen S, et al. Impact of initial CSF findings on outcome among patients with national cancer institute standard- and high-risk B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the children’s oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2527‐2534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.4774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levinsen M, Taskinen M, Abrahamsson J, et al. Clinical features and early treatment response of central nervous system involvement in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(8):1416‐1421. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pui CH, Howard SC. Current management and challenges of malignant disease in the CNS in paediatric leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(3):257‐268. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vora A, Andreano A, Pui CH, et al. Influence of cranial radiotherapy on outcome in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with contemporary therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):919‐926. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.2850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krull KR, Hardy KK, Kahalley LS, Schuitema I, Kesler SR. Neurocognitive outcomes and interventions in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(21):2181‐2189. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Follin C, Erfurth EM. Long-term effect of cranial radiotherapy on pituitary-hypothalamus area in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia survivors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2016;17(9):50. doi: 10.1007/s11864-016-0426-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlain MC, Glantz M, Groves MD, Wilson WH. Diagnostic tools for neoplastic meningitis: detecting disease, identifying patient risk, and determining benefit of treatment. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(4 Suppl 2):S35‐S45. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander P, Guenter H, Tatiana V, et al. Absolute count of leukemic blasts in cerebrospinal fluid as detected by flow cytometry is a relevant prognostic factor in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncol. 2019;145(5):1331‐1339. doi: 10.1007/s00432-019-02886-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maria G, Silvia D, Pamela S, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis by 8-color flow cytometry in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(11):2825‐2828. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2019.1602269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maria T, Hanne VM, Mette L, et al. Flow cytometric detection of leukemic blasts in cerebrospinal fluid predicts risk of relapse in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Nordic society of pediatric hematology and oncology study. Leukemia. 2020;34(2):336‐346. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0570-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hematology Group of Pediatric Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Editorial Committee of Chinese Journal of Pediatrics. Recommendations on diagnosis and treatment of children’s acute lymphoblastic leukemia (fourth revision). Chin J Pediat. 2014;52(9):641‐644. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1310.2014.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bene MC, Castoldi G, Knapp W, et al. Proposals for the immunological classification of acute leukemias. European group for the immunological characterization of leukemias (EGIL). Leukemia. 1995;9(10):1783‐1786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown PA, Wieduwilt M, Logan A, et al. Guidelines insights: acute lymphoblastic leukemia, version 1.2019. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17(5):414‐423. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):573‐577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Del Principe MI, Maurillo L, Buccisano F, et al. Central nervous system involvement in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: diagnostic tools, prophylaxis, and therapy. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2014;6(1):e2014075. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2014.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nückel H, Novotny JR, Noppeney R, Savidou I, Dührsen U. Detection of malignant haematopoietic cells in the cerebrospinal fluid by conventional cytology and flow cytometry. Clin Lab Haem. 2006;28(1):22‐29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2257.2006.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bromberg JEC, Breems DA, Kraan J, et al. CSF flow cytometry greatly improves diagnostic accuracy in CNS hematologic malignancies. Neurology. 2007;68(20):1674‐1679. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000261909.28915.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranta S, Nilsson F, Harila-Saari A, et al. Detection of central nervous system involvement in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia by cytomorphology and flow cytometry of the cerebrospinal fluid. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(6):951‐956. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]