Abstract

The medicinal plant Dendrobium nobile is an important natural antioxidant resource. To reveal the antioxidants of D. nobile, high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) was employed for metabolic analysis. The H2O2-induced oxidative damage was used in human embryonic kidney 293T (H293T) cells to assess intracellular antioxidant activities. Cells incubated with flower and fruit extracts showed better cell survival, lower levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and higher catalase and superoxide dismutase activities than those incubated with root, stem, and leaf extracts (p < 0.01). A total of 13 compounds were newly identified as intracellular antioxidants by association analysis, including coniferin, galactinol, trehalose, beta-D-lactose, trigonelline, nicotinamide-N-oxide, shikimic acid, 5′-deoxy-5′-(methylthio)adenosine, salicylic acid, isorhamnetin-3-O-neohespeidoside, methylhesperidin, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, and cis-aconitic acid (R2 > 0.8, Log2FC > 1, distribution > 0.1%, and p < 0.01). They showed lower molecular weight and higher polarity, compared to previously identified in vitro antioxidants in D. nobile (p < 0.01). The credibility of HPLC-MS/MS relative quantification was verified by common methods. In conclusion, some saccharides and phenols with low molecular weight and high polarity helped protect H293T cells from oxidative damage by increasing the activities of intracellular antioxidant enzymes and reducing intracellular ROS levels. The results enriched the database of safe and effective intracellular antioxidants in medicinal plants.

Keywords: medicinal plant, oxidative damage, H293T, ROS, CAT, SOD, saccharides, phenols, molecular weight, polarity

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress is closely related to human health and many types of disease, such as ageing, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer [1]. Therefore, safe and effective antioxidants are abundantly needed for health care products and pharmaceuticals [2,3].

Medicinal plants, as important natural antioxidant resources, have attracted more and more attention in recent years [3,4]. The antioxidant capacity was reported in extracts from many medicinal plants around the world, such as Crataegus oxyacantha, Hamamelis virginiana, Hydrastis canadensis, Salvia nubicola, Acer oblongifolium, Hedera nepalensis, Curcuma longa, Zingiber officinale, Piper nigrum, and Piper longum [5,6,7]. Some species of Dendrobium, a widely used medicinal plant in Southeast Asia, also showed antioxidant effects in vitro and in vivo. Extracts from D. Officinale, D. catenatum, D. huoshanense, D. candidum, D. crepidatum, D. moniliforme, D. chrysotoxum, and D. tosaense showed protective effects on oxidative damages in PC12 cells, U251 cells, HFF-1 cells, Jurkat cells, H9c2 cells, and B16/F10 cells [8,9,10,11,12]. D. nobile extracts also showed beneficial effects in protecting cells from oxidative damage [13,14,15,16].

For better application in the health products industry and pharmaceutical industry, the core chemical compounds contributing to antioxidant activities need to be identified in Dendrobium [3,17]. To date, only some of the polysaccharides, flavonoids, and bibenzyls have been reported to be related to antioxidant activities in D. nobile, D. officinale, D. huoshanense, D. candidum, D. loddigesii, and D. pachyglossum [8,11,12,15,18]. Comprehensive and systematic analyses are still required for the antioxidant basis of Dendrobium. Along with the development of high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) technology, it has been used for metabolic analysis, chemical differentiation, quality control, and pharmaceutical identification in medicinal plants [4,14,19]. The recently established quasi-targeted metabolomics based on multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) enables HPLC-MS/MS to quickly, extensively, and accurately identify metabolites [14,20,21]. It will be helpful for functional-metabolic co-analysis in Dendrobium species [14,22].

HPLC-MS/MS is used in this article for quantitative analysis of secondary metabolites among different tissues of D. nobile. Intracellular antioxidant activities are evaluated by H2O2-induced oxidative damage in human embryonic kidney 293T cells (H293T). The key chemical basis is then revealed by a co-analysis of antioxidant activities and secondary metabolites.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

Fresh roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits of D. nobile were obtained from Hejiang, Sichuan Province (28°49′ N, 105°50′ E). Roots, stems, leaves, and flowers were collected in May 2019 and May 2020, and fruits were collected in November 2019 and November 2020. The tissue samples were obtained from more than 30 individual plants for each collection. The tissue samples were washed with pure water, dried at 40 °C for a week, ground in powder, and screened using a 50 mesh sieve for the extraction of metabolites.

2.2. Cell Lines and Chemical Reagents

H293T cell lines were purchased from the Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology (Shanghai, China). Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium-high glucose (DMEM), penicillin/streptomycin, trypsin, and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) were purchased from Wisent Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Gibco Inc. (Canyon, OR, USA). The bovine serum albumin (BSA) and bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit were purchased from Solarbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), radio immuno-precipitation assay (RIPA) buffer, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), total superoxide dismutase (SOD) assay kit with WST-8, catalase (CAT) assay kit, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) assay kit were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) was purchased from Tongren Chemical Research Institute (Kumamoto, Japan).

2.3. Metabolites Extraction for HPLC-MS/MS

Each 100 mg fine powdered sample was suspended with a 500 μL prechilled solution (80% methanol contained 0.1% formic acid) by well vortexing. The sample was incubated for 5 min and then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was diluted to a final concentration of 53% methanol by pure water. The sample was then transferred to a new tube and then centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatant was used for chromatography [14].

2.4. Metabolites Extraction for Bioactivity Analysis

Each 5 g fine powdered sample was immersed in a 200 mL solution (80% methanol contained 0.1% formic acid) at room temperature for 24 h and then filtered to remove the residues. The filtrates were subsequently condensed in a rotary evaporator at 40 °C for 2 h and then were evaporated under vacuum for final drying. The dry extracts were dissolved with DMSO at a concentration of 100 mg/mL and diluted with DMEM medium to a final concentration of 50 μg/mL and 100 μg/mL for intracellular analysis [19].

2.5. HPLC-MS/MS Analysis

HPLC-MS/MS analyses were performed using an ExionLC™ AD system coupled with a QTRAP® 6500+ mass spectrometer (AB Sciex Pte. Ltd., Framingham, MA, USA) in Novogene Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Positive ion mode: Sample was injected onto a BEH C8 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.9 μm) using a 30 min linear gradient at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min in the positive polarity mode. The eluents were eluent A (0.1% formic acid-water) and eluent B (0.1% formic acid-acetonitrile). The solvent gradient was established as follows: 5% B, 1 min; 5–100% B, 24.0 min; 100% B, 28.0 min; 100–5% B, 28.1 min; 5% B, 30 min. QTRAP® 6500+ mass spectrometer was operated in positive polarity mode with curtain gas of 35 psi, collision gas of medium, ionspray voltage of 5500 V, temperature of 500 °C, ion source gas of 1:55, and ion source gas of 2:55. Negative ion mode: Sample was injected onto a HSS T3 column (100 mm × 2.1 mm) using a 25 min linear gradient at a flow rate of 0.35 mL/min in the negative polarity mode. The eluents were eluent A (0.1% formic acid-water) and eluent B (0.1% formic acid-acetonitrile). The solvent gradient was set as follows: 2% B, 1 min; 2–100% B, 18.0 min; 100% B, 22.0 min; 100–5% B, 22.1 min; 5% B, 25 min. QTRAP® 6500+ mass spectrometer was operated in positive polarity mode with curtain gas of 35 psi, collision gas of medium, ionspray voltage of −4500 V, temperature of 500 °C, ion source gas of 1:55, and ion source gas of 2:55 [14].

2.6. Standards Database of novoDB

Chemical standards were used for key parameter collection under the chromatographic and mass spectrometry conditions above. Finally, a total of six parameters, including parent ion (Q1), daughter ion (Q3), declustering potential (DP), collision energy (CE), molecular weight (MW), and retention time (RT), were stored for each specific compound in novoDB database. Then, it was used for quasi-targeted metabolic analysis under a certain LC-MS/MS method [20,22]. Currently, more than 3250 plant compounds can be employed in the novoDB database (https://cn.novogene.com/, accessed on 25 May 2023).

2.7. Metabolites Identification by Multiple Reaction Monitoring

To quickly, accurately, and extensively identify metabolites in the extracts of D. nobile, MRM was used for scanning mainly based on the above six key parameters [21]. For the Q1/Q3 scan, ±0.7 was set, and 0–300 was set for the DP scan; ±150 was set for the CE scan, and ±0.01 was set for the RT scan. If a compound matches a standard within the set scanning channel, this compound is detected as the standard. The MS parameters and chromatographic signals of all matched compounds were exported as a raw data file for further analysis.

2.8. Metabolites Quantification

The data files generated by HPLC-MS/MS were processed using SCIEX OS Version 1.4 (AB Sciex Pte. Ltd., Framingham, MA, USA) to integrate and correct the peak. The main parameters were established as a minimum peak height of 500, a signal/noise ratio of 5, and a Gaussian smooth width of 1. The screened signal peaks were used for peak area integration. The peak area of Q3 was used for relative quantification of the corresponding metabolite [22].

2.9. Metabolites Annotation

These metabolites were further annotated using the KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/, accessed on 25 May 2023), the HMDB database (http://www.hmdb.ca/, accessed on 25 May 2023), and the Lipidmaps database (http://www.lipidmaps.org/, accessed on 25 May 2023) [14]. These annotations were used for a final classification of each compound.

2.10. Cell Survival Assay under H2O2

H293T cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Each 100 μL of cell culture included 4 × 104 cells and was transferred to a new 96-well plate. The cells were then incubated with extracts (50 µg/mL, 100 µg/mL) or the same amount of DMSO for 24 h and then exposed to H2O2 for 4 h. A half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 200 µM was used for a further H2O2-inducing assay (Figure S1). Then, the CCK-8 reagent was added to each well and incubated for 3 h at 37 °C. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm with a microplate reader. Cell survival rate = (As − Am)/(Ac − Am) × 100% (As: absorbance of sample; Am: absorbance of medium; Ac: absorbance of control) [13,23].

2.11. Detection of ROS Levels

After induction by H2O2, H293T cells were collected for detection using a reactive oxygen species assay kit. The fluorescence probe was diluted to 10 μM by DMEM without fetal bovine serum. Then, it was added to cover the collected cells without culture medium. After co-culturing at 37 °C for 20 min, the cells were washed with DMEM without fetal bovine serum three times. Finally, cells were detected by the Thermo scientific Varioskan Flash (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm. Rosup was used as a positive control [13].

2.12. Cell Lysis

After induction by H2O2, H293T cells were collected and washed with 500 µL of 1× PBS (pH 7.4, without calcium and magnesium) three times. The cells were then resuspended by 1 mL of 1× PBS and transferred to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube for centrifugation at 1500 g for 5 min under 4 °C. After removing the supernatant, 200 µL of RIPA buffer (pH 7.4, 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing 1 mM PMSF was added to the lysis cells for 20 min at 4 °C. The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000× g for 10 min under 4 °C. Each 20 µL of the supernatant was used for detection of total protein, SOD activity, and CAT activity.

2.13. Detection of Total Proteins

Each 20 μL of cell lysis solution was added with 200 μL of BCA working solution (50:1 of bicinchoninic acid and Cu reagent). After mixing well, they were placed at 37 °C for 30 min. The absorbance at 562 nm was used for calculation of total proteins with BSA standard [14,19]. The standard curve of BSA is shown in Figure S2A.

2.14. Detection of SOD Enzyme Activities

Each 20 μL of cell lysis solution was added with 151 μL SOD detection solution, 8 μL WST-8, 1 μL enzyme buffer, and 20 μL reaction start solution. After mixing well, they were placed at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, it was detected at an absorbance of A450 by the Thermo scientific Varioskan Flash (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). When the inhibition rate of the xanthine oxidase coupling reaction system is 50%, the SOD activity in the reaction system is defined as one unit of enzyme activity (1 unit). SOD activity = ((A450 control − A450sample)/A450 control × 100%/(1 − ((A450 control − A450sample)/A450 control × 100%))/(20 × protein concentration) [13].

2.15. Detection of CAT Enzyme Activities

Each 20 μL of cell lysis solution was added with 20 μL CAT buffer and 10 μL hydrogen peroxide solution (250 mM). After mixing well, they were placed at 25 °C for 5 min. Then, a 450 μL stopping solution was added to stop the reaction. Each 10 μL of the reaction solution was added with 40 μL CAT buffer. Each 10 μL of the mixed solution was added with a 200 μL chromogenic solution. After placing at 25 °C for 20 min, it was detected at an absorbance of A520 by the Thermo scientific Varioskan Flash (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). One unit of enzyme activity (1 unit) of CAT means that it can catalyze the decomposition of 1 micromole hydrogen peroxide within 1 min at 25 °C and pH 7.0 [13]. CAT activity = ((A520 control − b)/k − (A520 sample − b)/k) × 250/(20 × 20 × protein concentration). The b and k are the constant of the standard curve of hydrogen peroxide concentration (Figure S2D).

2.16. Detection of Total Soluble Saccharides

Each 0.25 g fine powdered sample was used for extraction with 100 mL of 80% ethanol solution. The filtered residue was used for extraction with 100 mL of pure water once more. Reflux extraction was performed at 40 °C for 1 h. All filtrates were collected and added to a final volume of 500 mL. Then, 2 mL of extracts, 1 mL of 5% phenol solution, and 5 mL of H2SO4 were mixed and kept in a boiling water bath for 20 min. After cooling, it was detected at an absorbance of A490 by Thermo scientific Varioskan Flash (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Glucose was used for the calculation of the saccharide content [19]. The standard curve of glucose is shown in Figure S2B.

2.17. Detection of Total Phenols

Each 0.2 g fine powdered sample was used for extraction with 50 mL of pure water at 100 °C for 30 min. Each 2.5 mL filtrate of the extracts was added to 30 mL of 60% ethanol. Ultrasound extraction was performed at room temperature for 10 min. After filtration, the final volume was constant to 40 mL by 60% ethanol. Each 1 mL final extraction was added with 2.5 mL Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and 2.5 mL 15% sodium carbonate solution. The final volume was constant to 10 mL by pure water. After well mixing, they were placed at 40 °C for 1 h and room temperature for 20 min. The supernatant was used for detection at an absorbance of A778. Gallic acid monohydrate was used for the calculation of the content of total phenols [18,24]. The standard curve of gallic acid is shown in Figure S2C.

2.18. Statistics Analysis

The entire experimental procedure is shown in Figure S3. All measurements and experiments were repeated three times, and the data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Log2(fold change) (Log2(FC)) was used for the comparison of metabolic data. Correlation analysis was performed using PASW statistics 18.0 (International Business Machines Corporation, New York, USA). Pearson’s correlation coefficients and p-value were used to evaluate the correlations. Student’s t-test was used for comparison between two groups. One-way analysis of variance was used for comparison among three and more groups.

3. Results

3.1. Fine Capacity to H2O2 Induction in Flower and Fruit Extracts of D. nobile

H2O2 induction caused severe damage to cell morphology and cell viability (Figure 1). However, H293T cells incubated with D. nobile extracts showed better cell states than those incubated with DMSO only. The cells incubated with flower or fruit extracts showed an almost normal cell state to the cells without H2O2 induction. At a concentration of 50 µg/mL, the cell survival rates of root, stem, and leaf groups were approximately 60%. The cell survival rates of flower and fruit groups were more than 70% (Figure 2A). At a concentration of 100 µg/mL, the cell survival rates of root, stem, and leaf groups were less than 60%. The cell survival rates of flower and fruit groups were more than 65% (Figure 2B). Under both concentrations, the relative cell suppressing rates in root and stem groups showed no significant variances to the control group (Figure 2C,D). The relative cell suppressing rates in the leaf group were significantly lower than those in control group (p < 0.05). The relative cell suppressing rates in the flower and fruit groups were extremely significantly lower than those in control group (p < 0.01). Better cell states, higher survival rates, and lower suppression rates indicate that flower and fruit extracts of D. nobile possess a fine capacity in response to induction of H2O2.

Figure 1.

Response of H293T cells to H2O2-induced damage supplied with extracts from different parts of D. nobile. (A–C,G–I) H293T cells under DMSO or 50 µg/mL of D. nobile extracts without H2O2. (D–F,J–L) H293T cells under DMSO or 50 µg/mL of D. nobile extracts with 200 µM H2O2.

Figure 2.

Comparison of survival rates and suppressing rates in H293T cells with H2O2-induced damage. (A) Survival rates under 50 µg/mL of extracts from different parts of D. nobile. (B) Survival rates under 100 µg/mL of extracts from different parts of D. nobile. (C) Suppressing rates under 50 µg/mL of extracts from different parts of D. nobile. (D) Suppressing rates under 100 µg/mL of extracts from different parts of D. nobile. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared to control group.

3.2. Good Intracellular ROS Scavenging Effects of Flower and Fruit Extracts

ROS levels in H293T cells increased substantially after H2O2 induction (Figure 3A). ROS levels showed no significant increase after incubating with D. nobile extracts without H2O2 induction. The increased ROS levels in the root, stem, and leaf groups were significantly lower than those in the control group (Figure 3B, p < 0.05). The increased ROS levels in flower and fruit groups were extremely significantly lower than those in the control group (p < 0.01). These results clearly show the good intracellular ROS scavenging effects of D. nobile extracts, especially from flowers and fruits.

Figure 3.

Comparison of ROS levels, CAT activities, and SOD activities in response to H2O2 induction. (A) ROS levels detected in H293T cells. (B) Comparison of increased ROS levels. (C) CAT activities detected in H293T cells. (D) Comparison of suppressed CAT activities. (E) SOD activities detected in H293T cells. (F) Comparison of suppressed SOD activities. Cells were incubated with 50 µg/mL of D. nobile extracts and induced by 200 µM H2O2. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 compared to control group.

3.3. Improved CAT and SOD Activities by Flower and Fruit Extracts

CAT and SOD activities were substantially suppressed by H2O2 induction (Figure 3C,E). However, CAT and SOD activities were improved by incubating with D. nobile extracts in all groups with or without H2O2 induction. The relatively suppressed CAT activity in root group showed no significant variance to that in control group (Figure 3D). The relatively suppressed CAT activities in the stem, leaf, and flower groups were significantly lower than those in the control group (p < 0.05). The relatively suppressed CAT activities in the fruit group were extremely significantly lower than those in the control group (p < 0.01). The relatively suppressed SOD activities in the root group were significantly lower than those in the control group (Figure 3F, p < 0.05). The relatively suppressed SOD activities in the stem, leaf, flower, and fruit group were extremely significantly lower than those in the control group (p < 0.01). These results suggest that pretreatment with flower and fruit extracts can significantly help to improve CAT and SOD enzyme activities in H293T cells, which is beneficial for reducing oxidative damage.

3.4. Evaluation of the Stability and Reliability in HPLC-MS/MS

The entire procedure of HPLC-MS/MS is shown in Figure S3. To identify some more metabolites in D. nobile, a positive mode with a BEH C8 chromatographic column and a negative mode with an HSS T3 chromatographic column were used for HPLC-MS/MS analysis for each sample. A total of 712 metabolites were finally identified in the methanol extracts of D. nobile by HPLC-MS/MS (Figure 4 and Figure S4). The detailed identification information of 55 metabolites is shown in Table 1. The detailed identification information of the remaining 657 metabolites is shown in Table S1. The partial extracted ion chromatograms screened by MRM are shown in Figure S5. Furthermore, quality control (QC) samples were used to evaluate the stability and reliability of HPLC-MS/MS (Figure S4). They were mixed samples of roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits of D. nobile in this study. First, a good coincidence was obviously observed in the chromatography peaks among three repeated samples in both modes (Figure 4 and Figure S4). Then, Pearson correlation analysis further indicated the good consistence in repeated samples (coefficient > 0.98, Table 2). However, the coefficients between different types of samples were less than 0.8. These results suggested the good stability and reliability of HPLC-MS/MS, which is suitable for quantitative and comparative analysis.

Figure 4.

HPLC-MS/MS total ion chromatograms of extracts from D. nobile fruits. (A) Positive ion mode. (B) Negative ion mode.

Table 1.

Detailed information of 55 metabolites identified by HPLC-MS/MS in D. nobile 1.

| Compound ID | Name | Formula | MW (Da) |

RT (min) | Q1 (m/z) | Class | Peak Areas | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower1 | Flower2 | Flower3 | Fruit1 | Fruit2 | Fruit3 | QC1 | QC2 | QC3 | |||||||

| Com_405_pos | (−)-trans-Carveol | C10H16O | 152.233 | 1.09 | 153.13 | Lipids | 124,600 | 107,900 | 92,890 | 103,500 | 121,200 | 90,420 | 89,580 | 82,780 | 101,400 |

| Com_245_neg | (+)-Dihydrojasmonic acid | C12H20O3 | 212.285 | 13.03 | 211.10 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 36,260 | 26,710 | 22,320 | 27,540 | 36,160 | 30,830 | 28,420 | 20,820 | 17,560 |

| Com_131_neg | 13-HOTrE | C18H30O3 | 294.000 | 12.70 | 293.00 | Lipids | 24,070 | 22,970 | 32,880 | 26,400 | 29,030 | 28,130 | 18,910 | 20,200 | 25,650 |

| Com_558_pos | 2-Methyladenosine | C11H15N5O4 | 281.268 | 0.77 | 282.10 | Nucleotide And Its Derivates | 4,340,000 | 1,754,000 | 1,430,000 | 2,165,000 | 1,921,000 | 2,051,000 | 1,351,000 | 1,199,000 | 1,256,000 |

| Com_437_pos | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylpentane-1,5-dioic acid | C6H10O5 | 162.141 | 4.23 | 163.00 | Amino Acid And Its Derivatives | 1,626,000 | 683,500 | 1,504,000 | 1,670,000 | 1,635,000 | 1,518,000 | 508,700 | 453,400 | 506,600 |

| Com_375_pos | 3-Methylcrotonylglycine | C7H11NO3 | 157.167 | 0.61 | 158.10 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 154,600 | 131,500 | 110,400 | 154,400 | 150,700 | 159,300 | 120,400 | 94,650 | 67,130 |

| Com_271_neg | 3-O-p-Coumaroyl shikimic acid O-hexoside | C22H26O12 | 482.100 | 5.30 | 481.10 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 244,000 | 33,630 | 7233 | 110,400 | 104,900 | 104,000 | 44,740 | 43,480 | 43,210 |

| Com_247_neg | 4-Hydroxy-2-oxoglutaric acid | C5H6O6 | 162.098 | 0.68 | 161.00 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 5,392,000 | 3,086,000 | 3,504,000 | 4,633,000 | 5,496,000 | 4,981,000 | 4,075,000 | 3,752,000 | 3,866,000 |

| Com_195_neg | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | 138.121 | 0.78 | 137.02 | Phenols | 4,686,000 | 3,329,000 | 2,630,000 | 2,804,000 | 2,826,000 | 2,589,000 | 1,798,000 | 1,737,000 | 1,761,000 |

| Com_647_pos | 4-Nitrophenol | C6H5NO3 | 139.109 | 29.43 | 140.00 | Phenols | 1,210,000 | 1,138,000 | 1,205,000 | 1,245,000 | 1,166,000 | 1,228,000 | 698,600 | 1,059,000 | 1,281,000 |

| Com_485_pos | 5′-Deoxy-5′-(methylthio)adenosine | C11H15N5O3S | 297.333 | 2.57 | 298.00 | Nucleotide And Its Derivates | 2,370,000 | 22,660,000 | 16,880,000 | 11,170,000 | 10,400,000 | 10,500,000 | 4,789,000 | 4,347,000 | 4,120,000 |

| Com_300_neg | beta-D-Lactose | C12H22O11 | 342.297 | 0.74 | 341.11 | Carbohydrates | 37,570,000 | 44,770,000 | 54,900,000 | 54,530,000 | 52,990,000 | 51,770,000 | 31,150,000 | 33,200,000 | 35,770,000 |

| Com_487_pos | Biochanin A 7-O-beta-D-glucoside | C22H22O10 | 446.404 | 5.46 | 447.20 | Flavonoids | 1,057,000 | 74,550 | 72,300 | 325,800 | 352,000 | 323,100 | 132,500 | 220,300 | 177,900 |

| Com_368_pos | Biotin | C10H16N2O3S | 244.311 | 9.67 | 245.10 | Terpenoids | 563,500 | 363,600 | 393,000 | 402,600 | 388,600 | 456,800 | 274,300 | 390,400 | 416,400 |

| Com_728_pos | Camelliaside A | C33H40O20 | 756.668 | 4.21 | 757.22 | Flavonoids | 47,800 | 67,980 | 40,690 | 55,470 | 50,270 | 77,070 | 14,590 | 23,090 | 15,770 |

| Com_417_pos | Chrysophanol | C15H10O4 | 254.238 | 8.17 | 255.06 | Phenols | 131,998 | 22,440 | 6,259 | 56,540 | 44,750 | 66,440 | 45,470 | 53,540 | 51,910 |

| Com_178_neg | cis-Aconitic acid | C6H6O6 | 174.108 | 0.60 | 173.00 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 4,248,000 | 2,009,000 | 3,113,000 | 3,624,000 | 3,708,000 | 3,272,000 | 1,294,000 | 1,589,000 | 1,520,000 |

| Com_672_pos | Cytidine monophosphate | C9H14N3O8P | 323.197 | 0.74 | 324.00 | Nucleotide And Its Derivates | 246,900 | 253,000 | 226,900 | 218,300 | 227,000 | 206,500 | 108,300 | 126,100 | 124,600 |

| Com_253_neg | Coniferin | C16H22O8 | 342.341 | 0.87 | 341.00 | Phenols | 169,400,000 | 223,900,000 | 251,000,000 | 240,200,000 | 223,600,000 | 240,500,000 | 149,200,000 | 160,000,000 | 170,700,000 |

| Com_277_neg | Coumalic acid | C6H4O4 | 140.094 | 1.15 | 141.02 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 98,560 | 90,310 | 69,600 | 77,940 | 114,800 | 110,700 | 56,040 | 70,340 | 62,880 |

| Com_32_neg | Curcumin | C21H20O6 | 368.380 | 4.53 | 367.12 | Phenols | 118,100 | 49,710 | 60,470 | 126,100 | 108,100 | 120,400 | 30,700 | 36,390 | 33,940 |

| Com_134_neg | Cyclic adenosine monophosphate | C10H12N5O6P | 329.206 | 3.60 | 328.10 | Nucleotide And Its Derivates | 478,100 | 2,589,000 | 2,549,000 | 2,181,000 | 2,054,000 | 2,283,000 | 870,500 | 880,800 | 980,400 |

| Com_29_neg | D-Galacturonic acid | C6H10O7 | 194.139 | 0.71 | 193.04 | Carbohydrates | 137,000 | 118,200 | 342,900 | 180,000 | 226,200 | 225,000 | 92,630 | 87,140 | 103,400 |

| Com_27_neg | D-Glucono-1,5-lactone | C6H10O6 | 178.140 | 0.80 | 177.14 | Amino Acid And Its Derivatives | 254,700 | 128,600 | 83,170 | 230,200 | 222,400 | 235,300 | 136,800 | 166,100 | 145,300 |

| Com_4_neg | Echinacoside | C35H46O20 | 786.737 | 7.70 | 685.22 | Phenols | 275,200 | 311,500 | 448,500 | 365,900 | 334,300 | 344,500 | 171,900 | 154,800 | 117,000 |

| Com_194_neg | Forsythoside B | C34H44O19 | 756.702 | 7.52 | 755.24 | Phenylpropanoids | 446,900 | 549,000 | 325,000 | 486,400 | 465,100 | 469,100 | 183,700 | 190,800 | 194,700 |

| Com_238_neg | Galactinol | C12H22O11 | 342.116 | 0.87 | 341.10 | Carbohydrates | 192,900,000 | 203,400,000 | 234,800,000 | 208,300,000 | 191,200,000 | 238,000,000 | 151,100,000 | 148,800,000 | 156,700,000 |

| Com_79_neg | Geniposidic acid | C16H22O10 | 374.340 | 0.75 | 373.11 | Terpenoids | 104,700 | 43,100 | 36,340 | 65,210 | 45,800 | 56,160 | 33,990 | 36,810 | 28,020 |

| Com_273_neg | Glucarate O-phosphoric acid | C6H11PO11 | 290.100 | 0.63 | 289.10 | Carbohydrates | 280,000 | 47,750 | 48,560 | 164,600 | 145,500 | 167,800 | 79,100 | 80,190 | 102,700 |

| Com_707_pos | Homovanillic Acid | C9H10O4 | 182.173 | 9.37 | 183.10 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 90,000 | 5,783 | 4,315 | 25,880 | 24,000 | 24,810 | 12,050 | 14,070 | 18,100 |

| Com_588_pos | iP9G | C16H23N5O5 | 365.384 | 0.77 | 366.20 | Others | 810,100 | 906,900 | 1,022,000 | 911,800 | 893,000 | 955,300 | 651,900 | 691,700 | 753,500 |

| Com_111_neg | Isorhamnetin-3-O-neohespeidoside | C28H32O16 | 624.544 | 7.93 | 623.16 | Flavonoids | 4,094,000 | 10,180,000 | 10,700,000 | 10,560,000 | 9,969,000 | 10,810,000 | 3,783,000 | 4,058,000 | 4,088,000 |

| Com_213_neg | Jionoside A1 | C36H48O20 | 800.760 | 8.14 | 799.27 | Others | 50,711 | 14,330 | 17,309 | 40,330 | 32,340 | 45,130 | 11,840 | 11,080 | 9100 |

| Com_522_pos | L-Homoarginine | C7H16N4O2 | 188.227 | 2.59 | 189.00 | Amino Acid And Its Derivatives | 176,900 | 833,600 | 723,000 | 888,500 | 785,800 | 780,400 | 332,100 | 317,700 | 304,100 |

| Com_182_neg | L-Homocitrulline | C7H15N3O3 | 189.212 | 0.82 | 188.10 | Amino Acid And Its Derivatives | 9204 | 7947 | 6433 | 8819 | 6806 | 10,430 | 7105 | 7172 | 3215 |

| Com_164_neg | Lobetyolin +HCOOH | C21H30O10 | 442.460 | 0.81 | 441.18 | Others | 291,200 | 16,640 | 18,360 | 73,710 | 70,290 | 71,450 | 65,130 | 61,160 | 34,790 |

| Com_301_neg | LysoPA 18:0 | C21H35O7P | 438.270 | 0.80 | 437.27 | Lipids | 25,280 | 19,130 | 29,190 | 27,660 | 22,070 | 23,370 | 23,600 | 21,710 | 17,100 |

| Com_320_neg | Methylhesperidin | C29H36O15 | 624.587 | 7.95 | 623.20 | Flavonoids | 3,760,000 | 9,394,000 | 10,600,000 | 10,530,000 | 9,403,000 | 9,479,000 | 3,518,000 | 3,835,000 | 3,961,000 |

| Com_47_neg | Methylophiopogonanone A | C19H18O6 | 342.343 | 0.76 | 341.10 | Flavonoids | 39,480 | 67,950 | 78,550 | 75,730 | 75,180 | 75,100 | 49,290 | 35,960 | 53,470 |

| Com_103_neg | N,N-Dimethylglycine | C4H9NO2 | 103.120 | 0.64 | 102.06 | Amino Acid And Its Derivatives | 754,700 | 222,600 | 124,000 | 297,800 | 361,300 | 377,700 | 257,600 | 287,000 | 124,000 |

| Com_600_pos | Narcissoside | C28H32O16 | 624.544 | 5.92 | 625.18 | Flavonoids | 1,213,000 | 3,106,000 | 4,647,000 | 2,422,000 | 1,918,000 | 2,037,000 | 983,100 | 1,251,000 | 1,191,000 |

| Com_51_neg | Nicotinamide-N-oxide | C6H6N2O2 | 138.043 | 0.70 | 137.00 | Terpenoids | 32,870,000 | 33,780,000 | 31,940,000 | 34,720,000 | 38,290,000 | 33,330,000 | 20,920,000 | 18,380,000 | 19,710,000 |

| Com_446_pos | Nicotinic acid-hexoside | 1.09 | 286.00 | Phenols | 144,700 | 104,500 | 130,100 | 120,400 | 104,000 | 84,530 | 65,870 | 67,680 | 70,900 | ||

| Com_171_neg | Palmitaldehyde | C16H32O | 240.425 | 14.03 | 239.00 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 63,100 | 32,180 | 16,110 | 33,370 | 51,830 | 32,360 | 46,760 | 35,500 | 19,610 |

| Com_460_pos | Palmitic acid | C16H32O2 | 256.424 | 18.32 | 257.25 | Lipids | 17,060 | 17,170 | 13,510 | 15,500 | 15,020 | 17,780 | 13,480 | 15,510 | 15,230 |

| Com_304_neg | Purpureaside C | C35H46O20 | 786.728 | 7.61 | 785.25 | Phenylpropanoids | 242,900 | 239,600 | 345,200 | 275,900 | 278,200 | 239,000 | 120,500 | 112,200 | 109,800 |

| Com_196_neg | Salicylic acid | C7H6O3 | 138.121 | 0.67 | 137.10 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 18,580,000 | 9,875,000 | 10,580,000 | 12,990,000 | 12,950,000 | 11,250,000 | 7,783,000 | 7,140,000 | 7,478,000 |

| Com_218_neg | Shikimic acid | C7H10O5 | 174.151 | 0.57 | 173.05 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 23,910,000 | 15,040,000 | 15,710,000 | 16,810,000 | 17,570,000 | 17,540,000 | 11,030,000 | 10,600,000 | 10,850,000 |

| Com_65_neg | Suberic acid | C8H14O4 | 174.194 | 0.63 | 173.10 | Organic Acid And Its Derivatives | 2,458,000 | 1,542,000 | 1,552,000 | 1,737,000 | 1,788,000 | 1,937,000 | 1,051,000 | 1,212,000 | 1,131,000 |

| Com_311_neg | Sucralose | C12H19Cl3O8 | 397.634 | 0.63 | 395.01 | Carbohydrates | 317,600 | 314,900 | 204,600 | 294,400 | 315,100 | 316,600 | 250,000 | 225,000 | 195,300 |

| Com_38_neg | trans-Ferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 194.184 | 2.87 | 193.00 | Phenols | 628,200 | 94,470 | 155,500 | 348,700 | 242,900 | 271,700 | 295,000 | 166,100 | 138,000 |

| Com_262_neg | Trehalose | C12H22O11 | 342.297 | 0.74 | 341.11 | Carbohydrates | 175,400,000 | 207,700,000 | 216,200,000 | 209,200,000 | 192,200,000 | 196,300,000 | 137,600,000 | 147,400,000 | 162,400,000 |

| Com_263_neg | Trehalose 6-phosphate | C12H23O14P | 422.276 | 0.51 | 421.08 | Carbohydrates | 740,600 | 528,700 | 634,900 | 673,200 | 668,300 | 615,900 | 328,800 | 325,700 | 397,700 |

| Com_340_pos | Trigonelline | C7H7NO2 | 137.136 | 0.73 | 138.06 | Alkaloids | 38,200,000 | 29,560,000 | 36,390,000 | 45,160,000 | 43,450,000 | 41,950,000 | 17,400,000 | 17,590,000 | 17,930,000 |

| Com_268_neg | Vitamin D3 | C27H44O | 384.339 | 0.75 | 383.00 | Terpenoids | 576,800 | 175,500 | 249,600 | 235,800 | 227,100 | 242,000 | 145,600 | 209,500 | 229,500 |

1 MW molecular weight. RT retention time. Q1 parent ion. QC quality control.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation among different samples detected by HPLC-MS/MS.

| Names | Flower1 | Flower2 | Flower3 | Fruit1 | Fruit2 | Fruit3 | QC1 | QC2 | QC3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower1 | 1.000 | 0.985 ** | 0.983 ** | 0.729 | 0.724 | 0.729 | 0.539 | 0.556 | 0.562 |

| Flower2 | 0.985 ** | 1.000 | 0.986 ** | 0.711 | 0.710 | 0.713 | 0.542 | 0.559 | 0.567 |

| Flower3 | 0.983 ** | 0.986 ** | 1.000 | 0.665 | 0.667 | 0.668 | 0.542 | 0.561 | 0.568 |

| Fruit1 | 0.729 | 0.711 | 0.665 | 1.000 | 0.987 ** | 0.986 ** | 0.543 | 0.570 | 0.542 |

| Fruit2 | 0.724 | 0.710 | 0.667 | 0.987 ** | 1.000 | 0.986 ** | 0.550 | 0.577 | 0.543 |

| Fruit3 | 0.729 | 0.713 | 0.668 | 0.986 ** | 0.986 ** | 1.000 | 0.547 | 0.570 | 0.538 |

| QC1 | 0.539 | 0.542 | 0.542 | 0.543 | 0.550 | 0.547 | 1.000 | 0.982 ** | 0.986 ** |

| QC2 | 0.556 | 0.559 | 0.561 | 0.570 | 0.577 | 0.570 | 0.982 ** | 1.000 | 0.989 ** |

| QC3 | 0.562 | 0.567 | 0.568 | 0.542 | 0.543 | 0.538 | 0.986 ** | 0.989 ** | 1.000 |

** p < 0.01.

3.5. Distribution of Metabolites in D. nobile Fruits by HPLC-MS/MS

As shown in Figure 5, the 712 metabolites were classified into 11 classes, including amino acids and their derivatives, flavonoids, organic acids and their derivatives, phenols, nucleotide and its derivatives, carbohydrates, lipids, terpenoids, alkaloids, phenylpropanoids, and others. The top four distributed classes were carbohydrates (25.76%), organic acids and their derivatives (24.79%), phenols (14.57%), and amino acid and its derivatives (12.96%) in fruits of D. nobile (Figure 5C). In detail, 21 metabolites showed more than 1% relative content in D. nobile fruits, such as coniferin, galactinol, trehalose, malate, and citric acid (Figure 5D). Moreover, there were 17 metabolites that showed a significant enrichment in fruits of D. nobile compared to root, stem, leaf, and flower (Log2(FC) > 2, p < 0.01), such as isorhamnetin, kaempferide, naringerin, L-arabinose, and D-xylose (Figure 5B). These results clearly display the distribution of main metabolites in D. nobile fruits by the identification and relative quantification based on HPLC-MS/MS.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the detected metabolites in D. nobile fruits. (A) Fruits of D. nobile. (B) Significantly highly accumulated metabolites in fruits compared to roots, stems, leaves, and flowers. Each of Log2(Fruit/Root), Log2(Fruit/Stem), Log2(Fruit/Leaf), Log2(Fruit/Flower) of the 17 components were more than 2 (p < 0.01). (C) The detected metabolites were classified into 11 kinds of chemical compounds (n = 712). (D) The proportion of each individual metabolite in the fruit.

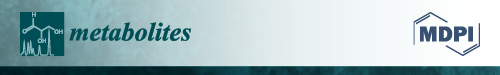

3.6. Intracellular Antioxidant Activities Associated Metabolites

After correlation analysis, there were 55 metabolites that showed significant association (coefficient > 0.8, p < 0.05) with cell survival/suppressing rates, ROS levels, CAT activities, and SOD activities (Table 3). As shown in Figure 6, the 55 metabolites were mainly belonging to seven classes of phenols (n = 20), carbohydrates (n = 8), organic acid and its derivatives (n = 8), nucleic acid derivative (n = 5), amino acid and its derivatives (n = 4), vitamins (n = 4), and others (n = 6). All showed a higher proportion in flowers or fruits compared to that in roots, stems, and leaves (Figure 6A). However, carbohydrates (12.58% in flowers, 19.90% in fruits) and phenols (6.99% in flowers, 11.77% in fruits) showed a substantially higher distribution in flower/fruit compared to other classes of metabolites (<2% in flowers and fruits). These results indicate that some carbohydrates and phenol metabolites are significantly associated with intracellular antioxidant activities in D. nobile flowers and fruits.

Table 3.

Correlation of intracellular antioxidant indexes to metabolites in D. nobile 1.

| NO. | Name | Cell Survival Rate | Cell Suppressing Rate | ROS1 | ROS2 | CAT1 | CAT2 | SOD1 | SOD2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 100 | 50 | 100 | ||||||||

| 1 | (-)-trans-Carveol | 0.996 ** | 0.940 * | −0.984 ** | −0.982 ** | −0.980 ** | −0.929 * | 0.976 ** | −0.897 * | 0.993 ** | −0.916 * |

| 2 | (+)-Dihydrojasmonic acid | 0.913 * | 0.861 | −0.839 | −0.817 | −0.871 | −0.816 | 0.933 * | −0.899 * | 0.921 * | −0.877 |

| 3 | 13-HOTrE | 0.976 ** | 0.932 * | −0.975 ** | −0.935 * | −0.999 ** | −0.990 ** | 0.921 * | −0.892 * | 0.938 * | −0.899 * |

| 4 | 2-Methyladenosine | 0.876 | 0.816 | −0.935 * | −0.892 * | −0.927 * | −0.937* | 0.789 | −0.714 | 0.855 | −0.752 |

| 5 | 3-Hydroxy-3-methylpentane- 1,5-dioic acid |

0.966 ** | 0.965 ** | −0.924 * | −0.923 * | −0.967 ** | −0.935 * | 0.937 * | −0.964 ** | 0.943 * | −0.952 * |

| 6 | 3-Methylcrotonylglycine | 0.895 * | 0.981 ** | −0.883 * | −0.922 * | −0.945 * | −0.941 * | 0.817 | −0.949 * | 0.898 * | −0.882 * |

| 7 | 3-O-p-coumaroyl shikimic- acid O-hexoside |

0.924 * | 0.906 * | −0.946 * | −0.904 * | −0.978 ** | −0.995 ** | 0.839 | −0.848 | 0.885 * | −0.824 |

| 8 | 4-Hydroxy-2-oxoglutaric acid | 0.955 * | 0.930 * | −0.899 * | −0.888 * | −0.937 * | −0.895 * | 0.947 * | −0.946 * | 0.926 * | −0.950 * |

| 9 | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 0.937 * | 0.873 | −0.975 ** | −0.952 * | −0.960 ** | −0.943 * | 0.874 | −0.782 | 0.929* | −0.847 |

| 10 | 4-Nitrophenol | 0.973 ** | 0.952 * | −0.926 * | −0.953 * | −0.940 * | −0.873 | 0.975 ** | −0.944 * | 0.979 ** | −0.894 * |

| 11 | 5′-Deoxy-5′-(methylthio)- adenosine |

0.883 * | 0.837 | −0.937 * | −0.907 * | −0.932 * | −0.937 * | 0.796 | −0.736 | 0.869 | −0.772 |

| 12 | beta-D-Lactose | 0.827 | 0.917 * | −0.845 | −0.864 | −0.910 * | −0.938 * | 0.717 | −0.863 | 0.818 | −0.772 |

| 13 | Biochanin A-7-O-beta- D-glucoside |

0.846 | 0.863 | −0.896 * | −0.899 * | −0.912 * | −0.924 * | 0.746 | −0.768 | 0.847 | −0.761 |

| 14 | Biotin | 0.938 * | 0.867 | −0.934 * | −0.974 ** | −0.889 * | −0.800 | 0.945 * | −0.801 | 0.978 ** | −0.945 * |

| 15 | Camelliaside A | 0.822 | 0.877 | −0.851 | −0.832 | −0.912 * | −0.955 * | 0.705 | −0.819 | 0.790 | −0.728 |

| 16 | Chrysophanol | 0.832 | 0.815 | −0.884 * | −0.823 | −0.916 * | −0.961 ** | 0.719 | −0.734 | 0.784 | −0.693 |

| 17 | cis-Aconitic acid | 0.923 * | 0.909 * | −0.945 * | −0.906 * | −0.978 ** | −0.994 ** | 0.838 | −0.851 | 0.886 * | −0.826 |

| 18 | Cytidylic acid | 0.856 | 0.818 | −0.915 * | −0.870 | −0.922 * | −0.946 * | 0.757 | −0.720 | 0.828 | −0.728 |

| 19 | Coniferin | 0.816 | 0.912 * | −0.837 | −0.866 | −0.899 * | −0.924 * | 0.705 | −0.853 | 0.815 | −0.766 |

| 20 | Coumalic acid | 0.870 | 0.836 | −0.900 * | −0.817 | −0.943 * | −0.987 ** | 0.772 | −0.784 | 0.801 | −0.733 |

| 21 | Curcumin | 0.891 * | 0.888 * | −0.894 * | −0.833 | −0.955 * | −0.988 ** | 0.803 | −0.861 | 0.827 | −0.789 |

| 22 | Cyclic adenylic acid | 0.839 | 0.834 | −0.882 * | −0.825 | −0.924 * | −0.970 ** | 0.726 | −0.763 | 0.789 | −0.708 |

| 23 | D-Galacturonic acid | 0.880 * | 0.900 * | −0.911 * | −0.895 * | −0.949 * | −0.971 ** | 0.779 | −0.831 | 0.858 | −0.790 |

| 24 | D-Glucono-1,5-lactone | 0.863 | 0.954 * | −0.820 | −0.837 | −0.910 * | −0.916 * | 0.797 | −0.968 ** | 0.837 | −0.857 |

| 25 | Echinacoside | 0.989 ** | 0.966 ** | −0.969 ** | −0.982 ** | −0.980 ** | −0.931 * | 0.965 ** | −0.932 * | 0.991 ** | −0.975 ** |

| 26 | Ferulic acid | 0.984 ** | 0.890 * | −0.996 ** | −0.942 * | −0.991 ** | −0.971 ** | 0.941 * | −0.833 | 0.948 * | −0.892 * |

| 27 | Forsythoside B | 0.962 ** | 0.908 * | −0.976 ** | −0.924 * | −0.994 ** | −0.995 ** | 0.897 * | −0.855 | 0.920 * | −0.865 |

| 28 | Galactinol | 0.825 | 0.908 * | −0.853 | −0.883 * | −0.903 * | −0.922 * | 0.717 | −0.838 | 0.831 | −0.772 |

| 29 | Geniposidic acid | 0.834 | 0.819 | −0.893* | −0.855 | −0.910 * | −0.941 * | 0.726 | −0.724 | 0.808 | −0.710 |

| 30 | Glucarate O-phosphoric acid | 0.853 | 0.912 * | −0.866 | −0.853 | −0.933 * | −0.967 ** | 0.748 | −0.869 | 0.821 | −0.777 |

| 31 | Homovanillic acid | 0.966 ** | 0.867 | −0.978 ** | −0.975 ** | −0.937 * | −0.874 | 0.954 * | −0.793 | 0.978 ** | −0.923 * |

| 32 | N6-Isopentenyl adenine- 9-glucoside |

0.849 | 0.906 * | −0.880 * | −0.891 * | −0.924 * | −0.944 * | 0.744 | −0.834 | 0.844 | −0.780 |

| 33 | Isorhamnetin-3-O- neohespeidoside |

0.845 | 0.878 | −0.874 | −0.841 | −0.930 * | −0.971 ** | 0.734 | −0.821 | 0.806 | −0.743 |

| 34 | Jionoside A1 | 0.946 * | 0.893 * | −0.917 * | −0.852 | −0.960 ** | −0.956 * | 0.909 * | −0.894 * | 0.882 * | −0.875 |

| 35 | L-Homoarginine | 0.942 * | 0.885 * | −0.938 * | −0.862 | −0.976 ** | −0.989 ** | 0.881 * | −0.861 | 0.874 | −0.839 |

| 36 | L-Homocitrulline | 0.845 | 0.986 ** | −0.803 | −0.910 * | −0.869 | −0.831 | 0.794 | −0.975 ** | 0.889 * | −0.911 * |

| 37 | Lobetyolin +HCOOH | 0.837 | 0.810 | −0.900 * | −0.897 * | −0.885 * | −0.884 * | 0.749 | −0.696 | 0.846 | −0.743 |

| 38 | LysoPA 18:0 | 0.957 * | 0.941 * | −0.907 * | −0.956 * | −0.911 * | −0.828 | 0.969 ** | −0.930 * | 0.981 ** | −0.856 |

| 39 | Methylhesperidin | 0.846 | 0.880 * | −0.875 | −0.845 | −0.930 * | −0.970 ** | 0.735 | −0.821 | 0.808 | −0.745 |

| 40 | Methylophiopogonanone A | 0.971 ** | 0.971 ** | −0.943 * | −0.940 * | −0.983 ** | −0.958 * | 0.931 * | −0.957 * | 0.950 * | −0.945 * |

| 41 | N,N-Dimethylglycine | 0.866 | 0.975 ** | −0.850 | −0.952 * | −0.889 * | −0.847 | 0.811 | −0.932 * | 0.919 * | −0.910 * |

| 42 | Narcissoside | 0.832 | 0.812 | −0.896 * | −0.883 * | −0.892 * | −0.903 * | 0.735 | −0.702 | 0.830 | −0.727 |

| 43 | Nicotinamide-N-oxide | 0.944 * | 0.914 * | −0.963 ** | −0.925 * | −0.988 ** | −0.994 ** | 0.868 | −0.856 | 0.910 * | −0.850 |

| 44 | Nicotinic acid-hexoside | 0.971 ** | 0.836 | −0.969 ** | −0.946 * | −0.922 * | −0.849 | 0.982 ** | −0.779 | 0.970 ** | −0.929 * |

| 45 | Palmitaldehyde | 0.962 ** | 0.992 ** | −0.935 * | −0.966 ** | −0.973 ** | −0.938 * | 0.920 * | −0.968 ** | 0.965 ** | −0.901 * |

| 46 | Palmitic acid | 0.971 ** | 0.952 * | −0.974 ** | −0.959 ** | −0.997 ** | −0.983 ** | 0.912 * | −0.903 * | 0.951 * | −0.910 * |

| 47 | Purpureaside C | 0.949 * | 0.974 ** | −0.948 * | −0.982 ** | −0.971 ** | −0.942 * | 0.892 * | −0.921 * | 0.962 ** | −0.929 * |

| 48 | Salicylic acid | 0.944 * | 0.912 * | −0.970 ** | −0.944 * | −0.983 ** | −0.980 ** | 0.871 | −0.841 | 0.923 * | −0.856 |

| 49 | Shikimic acid | 0.960 ** | 0.913 * | −0.982 ** | −0.951 * | −0.989 ** | −0.980 ** | 0.896 * | −0.845 | 0.938 * | −0.874 |

| 50 | Suberic acid | 0.961 ** | 0.887 * | −0.985 ** | −0.931 * | −0.989 ** | −0.985 ** | 0.898 * | −0.821 | 0.923 * | −0.856 |

| 51 | Sucralose | 0.857 | 0.898 * | −0.882 * | −0.863 | −0.937 * | −0.970 ** | 0.749 | −0.841 | 0.827 | −0.768 |

| 52 | Trehalose | 0.823 | 0.910 * | −0.850 | −0.886 * | −0.899 * | −0.916 * | 0.716 | −0.839 | 0.832 | −0.775 |

| 53 | Trehalose 6-phosphate | 0.884 * | 0.913 * | −0.913 * | −0.906 * | −0.951 * | −0.968 ** | 0.787 | −0.844 | 0.869 | −0.805 |

| 54 | Trigonelline | 0.880 * | 0.871 | −0.906 * | −0.848 | −0.953 * | −0.990 ** | 0.780 | −0.818 | 0.826 | −0.762 |

| 55 | Vitamin D3 | 0.841 | 0.866 | −0.881 * | −0.938 * | −0.872 | −0.842 | 0.769 | −0.763 | 0.886 * | −0.811 |

1 50 and 100 indicate the concentration of D. nobile extracts. ROS1 ROS accumulation, ROS2 ROS increasing, CAT1 CAT activities, CAT2 suppressed CAT activities, SOD1 SOD activities, SOD2 suppressed SOD activities. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Distribution of metabolites associated with antioxidant activities in D. nobile flowers and fruits. (A) Proportion in flowers and fruits compared to roots, stems, and leaves. (B) Distribution of metabolites associated with antioxidant activities in flowers. (C) Distribution of metabolites associated with antioxidant activities in fruits. Metabolites associated with antioxidant activities were classified into seven types of chemical compounds (n = 55).

3.7. The Main Intracellular Antioxidant Basis in Flowers and Fruits of D. nobile

In detail, 36 of the above 55 metabolites showed a higher proportion in the flower/fruit compared to the root, stem, and leaf, such as methylhesperidin, isorhamnetin-3-O-neohespeidoside, narcissoside, galactinol, coniferin, and trehalose (Log2(FC) > 1, Figure 7A). Furthermore, only 13 of them showed a relatively high distribution in flowers or fruits, simultaneously (Log2(FC) > 1, distribution > 0.1%, Figure 7B,C). They are coniferin, galactinol, trehalose, beta-D-lactose, trigonelline, nicotinamide-N-oxide, shikimic acid, 5′-deoxy-5′-(methylthio)adenosine, salicylic acid, isorhamnetin-3-O-neohespeidoside, methylhesperidin, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, and cis-aconitic acid. Among them, three carbohydrates, including galactinol, trehalose, and beta-D-lactose, showed proportions of 54.65% and 56.26% to the contents of all 13 metabolites in fruits and flowers, respectively. Five phenols, including coniferin, salicylic acid, isorhamnetin-3-O-neohespeidoside, methylhesperidin, and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, showed proportions of 31.76% and 30.55% to the contents of the 13 metabolites in fruits and flowers, respectively. In particular, each of coniferin, galactinol, and trehalose counted for more than 5% of all the 712 compounds detected in fruits and flowers. Substantially, the accumulation of carbohydrates and phenols in flowers and fruits resulted in an improvement in CAT and SOD activities, a reduction in ROS levels, and an increase in survival in response to H2O2 stimulation (Figure 8). These results clearly display the main intracellular antioxidant basis in flowers and fruits of D. nobile.

Figure 7.

Distribution of each single metabolite associated to antioxidant activities in D. nobile flowers and fruits. (A) Proportion in flowers and fruits compared to roots, stems, and leaves. (B) Distribution of each metabolite associated with antioxidant activities in flowers. (C) Distribution of each single metabolite associated to antioxidant activities in fruits.

Figure 8.

Diagram for the antioxidant basis in flowers and fruits of D. nobile. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

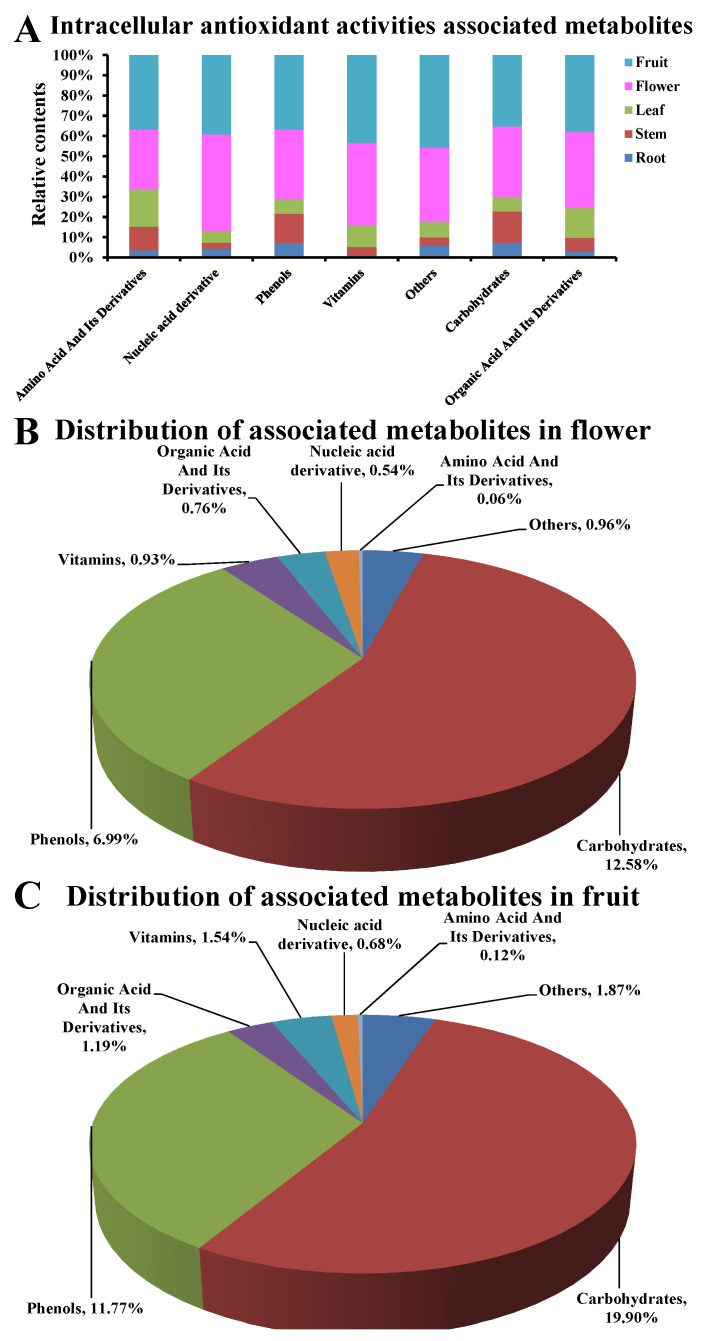

3.8. Differences between In Vitro and Intracellular Antioxidants

There was no overlap between the in vitro antioxidants and intracellular antioxidants in D. nobile (Figure 9A). The in vitro and intracellular antioxidant activities associated metabolites (coefficient > 0.8, p < 0.05) showed about 50% of the relative concentration in flowers and fruits. The relative concentration of key components (Log2(FC) > 1, distribution > 0.1%) for intracellular antioxidant activities was obviously higher than those for in vitro antioxidant activities in both of flowers and fruits (Figure 9B). In vitro antioxidants were only significantly accumulated in D. nobile flowers. However, intracellular antioxidants were significantly accumulated in flowers and fruits of D. nobile (Figure 9C,D). Moreover, the average molecular weights of intracellular antioxidants were significantly lower than those of in vitro antioxidants, when compared as key components (p < 0.01, Figure 9E). The average retention times of intracellular antioxidants were also significantly lower than those of in vitro antioxidants, when compared as key components (p < 0.01, Figure 9F). These results suggest that the in vitro and intracellular antioxidants were completely different types of compounds with different characteristics.

Figure 9.

Comparison of in vitro and intracellular antioxidants in D. nobile. (A) Overview of in vitro and intracellular antioxidants. (B) Distribution of in vitro and intracellular antioxidants in flowers and fruits. (C) Proportion of in vitro and intracellular antioxidant activities associated metabolites in flowers or fruits to the sum of roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits. (D) Proportion of key components for in vitro and intracellular antioxidant activities in flowers or fruits to the sum of roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits. (E) Comparison of molecular weights. (F) Comparison of retention times. The in vitro antioxidants in D. nobile were reported previously [14]. ** p < 0.01.

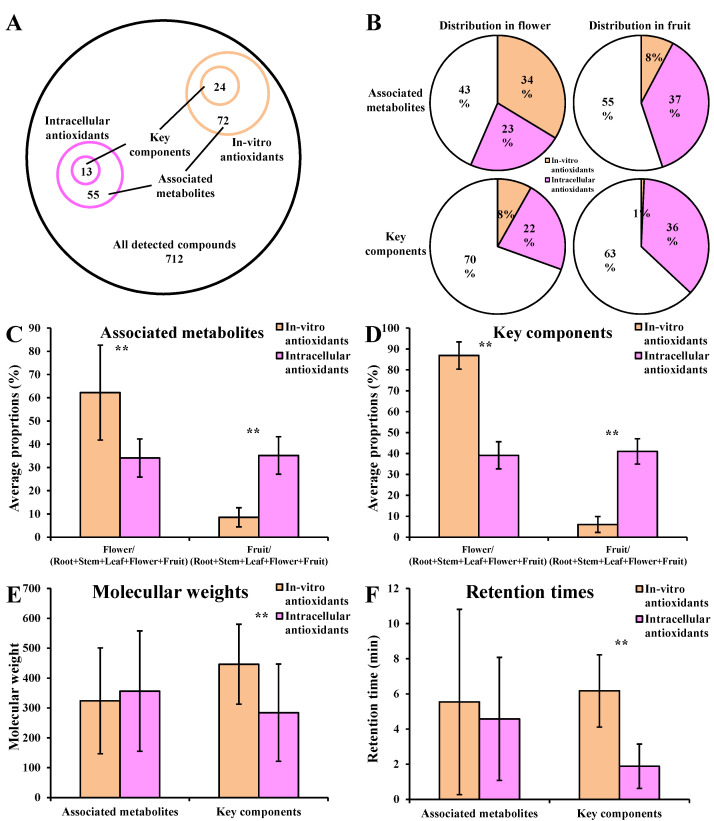

3.9. Verification of the HPLC-MS/MS Results

The colorimetric method showed that the total saccharides contents in roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits were 15.59 mg/g, 54.41 mg/g, 29.78 mg/g, 58.22 mg/g, and 91.28 mg/g, respectively (Figure 10A). Relative quantification by HPLC-MS/MS showed that the distributions of carbohydrates in roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits were 7.21%, 17.65%, 9.69%, 30.96%, and 34.48%, respectively (Figure 10B). Linear analysis showed a good consistency in saccharide contents detected by the two methods (R2 > 0.8, Figure 10C). The colorimetric method showed that the total phenol contents in the roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits were 9.09 mg/g, 14.68 mg/g, 9.41 mg/g, 34.40 mg/g, and 22.16 mg/g, respectively (Figure 10D). Relative quantification by HPLC-MS/MS showed that the distributions of total phenols in roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits were 13.81%, 10.54%, 21.56%, 25.02%, and 29.06%, respectively (Figure 10E). Linear analysis also showed a good consistency in phenol contents detected by the two methods (R2 > 0.8, Figure 10F). Together with the previously observed consistence in amino acids and their derivatives, organic acid and its derivatives, and flavonoids [14], these results suggest the credibility of HPLC-MS/MS in the identification and relative quantification for metabolic analysis in D. nobile.

Figure 10.

Comparison of the results detected by HPLC-MS/MS and the common determination method in D. nobile. (A) Total saccharides detected by colorimetry. (B) Sum of saccharides detected by HPLC-MS/MS (n = 62). (C) Linear analysis of saccharides contents by two methods. (D) Total phenols detected by colorimetry. (E) Sum of phenols detected by HPLC-MS/MS (n = 173). (F) Linear analysis of phenols contents by two methods.

4. Discussions

4.1. Accumulation of Saccharides and Phenols Resulted in Fine Intracellular Antioxidant Activities in D. nobile Flowers and Fruits

The H2O2 induced oxidative model has been widely used for the evaluation of intracellular antioxidant activities in many types of cells [8,12,13]. In this model, the methanolic extracts from the flowers and fruits of D. nobile showed a good antioxidant capacity in reducing ROS, improving CAT and SOD, and surviving (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3). The metabolic analysis of HPLC-MS/MS clearly indicated the enrichment of amino acid and its derivatives, organic acids and their derivatives, carbohydrates, and phenols in flowers and fruits of D. nobile (Figure 5) [14]. This firstly gives a comprehensive and systematic insight into the secondary metabolism of D. nobile [14,16]. Then, the co-analysis of antioxidant activities and secondary metabolites revealed that some saccharide and phenol compounds played a key role in protecting cells from oxidative damage (Table 3, Figure 6 and Figure 7). The monosaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polysaccharides from medicinal plants had been widely reported to confer antioxidant activities by reversing ROS levels and restoring antioxidant enzyme activities [25,26]. Polysaccharides from D. officinale attenuated H2O2-induced oxidative stress in H9c2 cells by increasing SOD activities and inhibiting intracellular ROS [8]. Polysaccharides from D. nobile attenuated UVB-induced damage by regulating SOD and CAT activities and decreasing malondialdehyde level in the mice model [16]. Some phenolic compounds in the extracts of D. catenatum, D. loddigesii, D. officinale, and D. nobile had been reported in in vitro antioxidant actions, such as ABTS and DPPH scavenging [10,11,14]. Rich-polyphenols extract of D. loddigesii also showed the antioxidant abilities to reduce malondialdehyde level and increase SOD and CAT contents in mice [18]. These reports further confirmed the feasibility and accuracy of the metabolism-activity co-analysis method in this study. In a word, the accumulated saccharides and phenols in the flowers and fruits of D. nobile helped them in protecting H293T cells from H2O2-induced oxidative damage by increasing intracellular SOD and CAT activities and reducing intracellular ROS levels. Moreover, the accuracy of quasi-targeted metabolomics based on HPLC-MS/MS was verified on flavonoid content with rutin standard, total protein content with BSA standard, total organic acid content with citric acid standard, total phenol content with gallic acid monohydrate standard, and saccharide content with glucose standard [14].

4.2. Intracellular Antioxidants Showed Different Characteristics from In Vitro Antioxidants in D. nobile

Previously, some flavonoids, organic acids and their derivatives, and amino acids and their derivatives were identified as key compounds involved in the in vitro antioxidant activities of ferric-reducing and ABTS- and DPPH-scavenging in D. nobile, such as rutin, astragalin, isomucronulatol-7-O-glucoside, quercetin 4′-O-glucoside, methylquercetin O-hexoside, caffeic acid, caffeic acid O-glucoside, and p-coumaric acid [14]. Here, some of the saccharides and phenols were identified as the key compounds involved in intracellular antioxidant activities in D. nobile, such as coniferin, salicylic acid, isorhamnetin-3-O-neohespeidoside, methylhesperidin, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, galactinol, trehalose, and beta-D-lactose (Figure 8). Firstly, they were completely different compounds, and they showed different distributions in roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and fruits of D. nobile. Second, intracellular antioxidants showed lower molecular weights than in vitro antioxidants. This is consistent with the fact that small-molecule plant secondary metabolites have been reported to show superiority in intracellular activities. For example, small-molecule procyanidin B1 significantly reduced ROS levels in response to H2O2 accumulation in mouse somatic cell nuclear transfer embryos [27]. Small-molecule flavonoids from Sorbus pohuashanensis were related to antitumor activity [28]. Thirdly, the intracellular antioxidants showed lower retention times than the in vitro antioxidants. Under the chromatographic conditions in this study, lower retention time means larger polarity for a component. The polarity was important for functional performing of plant extracts. For example, the polar character of the phenolic components significantly influenced their antioxidant capacity and biological activities [29]. The polarity of the metabolites in D. nobile was also reported to be related to intracellular activities. Less-polar components in ethanol extracts of D. nobile showed strong suppressing efficacy to A549 lung cancer cells [19]. Weak polar compounds of the ether extract exhibited a strong anticancer effect in HepG2 liver cancer cells [23]. In conclusion, the newly identified intracellular antioxidants showed significantly lower molecular weight and larger polarity than previously identified in vitro antioxidants in D. nobile. The different characteristics of intracellular antioxidants could provide new information about the development of antioxidant products from medicinal plants.

4.3. The Newly Identified Intracellular Antioxidants Will Further Enrich the Prospects of Dendrobium on Pharmaceuticals and Health-Care Products

The extracts of Dendrobium species have been reported to show good antioxidant ability in many assays [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. However, effective antioxidants were poorly identified in Dendrobium, especially for intracellular antioxidant activities [14,17,22]. In this paper, five phenolic compounds, three oligosaccharides, and five other metabolites were newly identified as key intracellular antioxidants in protecting H293T cells from oxidative damage. For the five phenolic compounds, only 4-hydroxybenzoic acid had been reported to associate with recovering of antioxidant enzymes and decreasing of oxidative stress in porcine kidney cells PK15 in the extracts of D. nobile [30]. The rest of them were poorly reported as intracellular antioxidants in Dendrobium and some other medicinal plants. Coniferin and its derivative from Linum usitatissimum have recently been reported to be involved in antioxidant activity in the β-carotene-linoleic acid emulsion system [24]. For the three oligosaccharides, galactinol, trehalose, and beta-D-lactose had not been reported as intracellular antioxidants in Dendrobium in previous studies. However, beta-D-lactose has been reported as a bioactive constituent in the extract of a standardized herbal cocktail that modulates oxidative stress in mouse models of major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder [25]. Trehalose has also been reported to alleviate oxidative stress in peripheral blood mononuclear cells stimulated by lipopolysaccharides [26]. This means that some oligosaccharides were still important for the antioxidant activities of Dendrobium extracts but not only polysaccharides. The five other metabolites, trigonelline, nicotinamide-N-oxide, shikimic acid, 5′-deoxy-5′-(methylthio)adenosine, and cis-aconitic acid were also poorly reported in Dendrobium for antioxidant activities. Trigonelline significantly alleviated UV-B-induced cell death effects in primary human dermal fibroblasts [31]. Shikimic acid from Artemisia absinthium enhanced antioxidant activity in diabetic rats [32]. cis-Aconitic acid was an important antioxidant constituent of Echinodorus grandiflorus for inhibiting antigen-induced arthritis and monosodium urate-induced arthritis in mice [33]. Substantially, almost all of the 13 compounds had not been reported for antioxidant activities in Dendrobium before this study. They enriched the library of safe and effective antioxidants, which was helpful for the utilization of Dendrobium in pharmaceuticals and health-care products. The following studies will focus on the targeted identification, isolation, bioactivities, and biosynthesis of these key metabolites.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/metabo13060702/s1, Table S1: Detailed information of 657 metabolites identified by HPLC-MS/MS in D. nobile. Figure S1: The survival rates of H293T cells under different concentrations of H2O2. Figure S2: Standard curves used for quantification of total proteins, total soluble saccharides, total phenols, and CAT activities. Figure S3: Schematic diagram for the entire experimental procedure in this study. Figure S4: HPLC-MS/MS total ion chromatograms of QC samples. Figure S5: Partial extracted ion chromatograms screened by MRM.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R. and S.Z.; methodology and project administration, D.R. and R.Z.; software, formal analysis, and visualization, Y.H. and H.L.; investigation and validation, Z.C.; resources, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, R.Z. and S.Z.; funding acquisition, R.Z. and S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

No humans or animals were involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Sichuan Science and Technology Program, grant number 2020YFN0001, 2021YFYZ0012, 2021YFH0080, and 2023NSFSC1281, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 32100305 and T2192971.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Forman H.J., Zhang H. Targeting oxidative stress in disease: Promise and limitations of antioxidant therapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2021;20:689–709. doi: 10.1038/s41573-021-00233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pisoschi A.M., Pop A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015;97:55–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu D.P., Li Y., Meng X., Zhou T., Zhou Y., Zheng J., Zhang J.J., Li H.B. Natural antioxidants in foods and medicinal plants: Extraction, assessment and resources. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:96. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zafar F., Asif H.M., Shaheen G., Ghauri A.O., Rajpoot S.R., Tasleem M.W., Shamim T., Hadi F., Noor R., Ali T., et al. A comprehensive review on medicinal plants possessing antioxidant potential. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2023;50:205–217. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Periera da Silva A., Rocha R., Silva C.M., Mira L., Duarte M.F., Florêncio M.H. Antioxidants in medicinal plant extracts. A research study of the antioxidant capacity of Crataegus, Hamamelis and Hydrastis. Phytother. Res. 2000;14:612–616. doi: 10.1002/1099-1573(200012)14:8<612::AID-PTR677>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inayatullah S., Prenzler P.D., Obied H.K., Rehman A.U., Mirza B. Bioprospecting traditional Pakistani medicinal plants for potent antioxidants. Food Chem. 2012;132:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.10.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swain S., Rautray T.R. Estimation of trace elements, antioxidants, and antibacterial agents of regularly consumed indian medicinal plants. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021;199:1185–1193. doi: 10.1007/s12011-020-02228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao X., Dou M., Zhang Z., Zhang D., Huang C. Protective effect of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides on H2O2-induced injury in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;94:72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan C.F., Wu C.T., Huang W.Y., Lin W.S., Wu H.W., Huang T.K., Chang M.Y., Lin Y.S. Antioxidation and melanogenesis inhibition of various Dendrobium tosaense extracts. Molecules. 2018;23:1810. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paudel M.R., Chand M.B., Pant B., Pant B. Antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of Dendrobium moniliforme extracts and the detection of related compounds by GC-MS. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2018;18:134. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2197-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X., Zhang S., Gao B., Qian Z., Liu J., Wu S., Si J. Identification and quantitative analysis of phenolic glycosides with antioxidant activity in methanolic extract of Dendrobium catenatum flowers and selection of quality control herb-markers. Food Res. Int. 2019;123:732–745. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2019.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warinhomhoun S., Muangnoi C., Buranasudja V., Mekboonsonglarp W., Rojsitthisak P., Likhitwitayawuid K., Sritularak B. Antioxidant sctivities and protective effects of dendropachol, a new bisbibenzyl compound from Dendrobium pachyglossum, on hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in HaCaT keratinocytes. Antioxidants. 2021;10:252. doi: 10.3390/antiox10020252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X., Zhao R., Zheng S., Chun Z., Hu Y. Dendrobium liquor eliminates free radicals and suppresses cellular proteins expression disorder to protect cells from oxidant damage. J. Food Biochem. 2020;44:e13509. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao D., Hu Y.D., Zhao R.X., Li H.J., Chun Z., Zheng S.G. Quantitative identification of antioxidant basis for Dendrobium nobile flower by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2022;2022:9510598. doi: 10.1155/2022/9510598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lei H., Zou S., Lin J., Zhai L., Zhang Y., Fu X., Chen S., Niu H., Liu F., Wu C., et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of constituents isolated from Dendrobium nobile (Lindl.) Front. Chem. 2022;10:988459. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2022.988459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long Y., Wang W., Zhang Y., Zhang S., Li Z., Deng J., Li J. Dendrobium nobile Lindl polysaccharides attenuate UVB-induced photodamage by regulating oxidative stress, inflammation and MMPs expression in mice model. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023:online. doi: 10.1111/php.13780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng S.G., Hu Y.D., Zhao R.X., Yan S., Zhang X.Q., Zhao T.M., Chun Z. Genome-wide researches and applications on Dendrobium. Planta. 2018;248:769–784. doi: 10.1007/s00425-018-2960-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X.W., Chen H.P., He Y.Y., Chen W.L., Chen J.W., Gao L., Hu H.Y., Wang J. Effects of rich-polyphenols extract of Dendrobium loddigesii on anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and gut microbiota modulation in db/db mice. Molecules. 2018;23:3245. doi: 10.3390/molecules23123245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng S., Hu Y., Zhao R., Zhao T., Li H., Rao D., Chun Z. Quantitative assessment of secondary metabolites and cancer cell inhibiting activity by high performance liquid chromatography fingerprinting in Dendrobium nobile. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2020;1140:122017. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2020.122017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C., Qiu J., Li G., Wang J., Liu D., Chen L., Song X., Cui L., Sun Y. Application and prospect of quasi-targeted metabolomics in age-related hearing loss. Hear Res. 2022;424:108604. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2022.108604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao J.N., Li Y., Liang J., Chai J.H., Kuang H.X., Xia Y.G. Direct acetylation for full analysis of polysaccharides in edible plants and fungi using reverse phase liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2023;222:115083. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2022.115083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo Z., Liu L., Nie Q., Huang M., Luo C., Sun Y., Ma Y., Yu J., Du F. HPLC-based metabolomics of Dendrobium officinale revealing its antioxidant ability. Front. Plant. Sci. 2023;14:1060242. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2023.1060242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao R., Zheng S., Li Y., Zhang X., Rao D., Chun Z., Hu Y. As a novel anticancer candidate, ether extract of Dendrobium nobile overstimulates cellular protein biosynthesis to induce cell stress and autophagy. J. Appl. Biomed. 2022;21:23–35. doi: 10.32725/jab.2022.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gai F., Janiak M.A., Sulewska K., Peiretti P.G., Karamać M. Phenolic compound profile and antioxidant capacity of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) harvested at different growth stages. Molecules. 2023;28:1807. doi: 10.3390/molecules28041807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Munter J., Pavlov D., Gorlova A., Sicker M., Proshin A., Kalueff A.V., Svistunov A., Kiselev D., Nedorubov A., Morozov S., et al. Increased oxidative stress in the prefrontal cortex as a shared feature of depressive- and PTSD-like syndromes: Effects of a standardized herbal antioxidant. Front. Nutr. 2021;8:661455. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.661455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastin A.R., Nazari-Robati M., Sadeghi H., Doustimotlagh A.H., Sadeghi A. Trehalose and N-acetyl cysteine alleviate inflammatory vytokine production and oxidative stress in LPS-stimulated human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Immunol. Investig. 2022;51:963–979. doi: 10.1080/08820139.2021.1891095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao W., Yu T., Li G., Shu W., Jin Y., Zhang M., Yu X. Antioxidant activity and anti-apoptotic effect of the small molecule procyanidin B1 in early mouse embryonic development produced by somatic cell nuclear transfer. Molecules. 2021;26:6150. doi: 10.3390/molecules26206150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiaojin Y., Caiyan L., Lianrong Y., Guoliang X., Zhengqing L., Shizhe C., Xiaodi Y., Hua H. Study on the antioxidant and anticancer activities of Sorbus pohuashanensis (hance) Hedl flavonoids in vitro and its screen of small molecule active components. Nutr. Cancer. 2022;74:2243–2253. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2021.1998560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arzola-Rodríguez S.I., Muñoz-Castellanos L.N., López-Camarillo C., Salas E. Phenolipids, amphipilic phenolic antioxidants with modified properties and their spectrum of applications in development: A review. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1897. doi: 10.3390/biom12121897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin H.K., Kim T.W., Kim Y.J., Park S.R., Seo C.S., Ha H., Jung J.Y. Protective effects of Dendrobium nobile against cisplatin nephrotoxicity both in-vitro and in-vivo. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2017;16:197–206. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanveer M.A., Rashid H., Nazir L.A., Archoo S., Shahid N.H., Ragni G., Umar S.A., Tasduq S.A. Trigonelline, a plant derived alkaloid prevents ultraviolet-B-induced oxidative DNA damage in primary human dermal fibroblasts and BALB/c mice via modulation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase-Akt-Nrf2 signalling axis. Exp. Gerontol. 2023;171:112028. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2022.112028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Malki A.L. Shikimic acid from Artemisia absinthium inhibits protein glycation in diabetic rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019;122:1212–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Oliveira D.P., Garcia E.F., de Oliveira M.A., Candido L.C.M., Coelho F.M., Costa V.V., Batista N.V., Queiroz-Junior C.M., Brito L.F., Sousa L.P., et al. cis-Aconitic Acid, a constituent of Echinodorus grandiflorus leaves, inhibits antigen-induced arthritis and gout in mice. Planta Med. 2022;88:1123–1131. doi: 10.1055/a-1676-4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article and Supplementary Materials.