Abstract

Healthcare systems intend to address health needs of a community, but unfortunately may also inadvertently exacerbate the climate crisis through increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Clinical medicine has not evolved to promote sustainability practices. New attention to the enormous impact of healthcare systems on GHG emissions and an escalating climate crisis has resulted in some institutions taking proactive measures to mitigate these negative effects. Some healthcare systems have made large-scale changes to conserve energy and materials, resulting in significant monetary savings. In this paper, we share our experience with developing an interdisciplinary work “green” team within our outpatient general pediatrics practice to implement changes, albeit small, to reduce our workplace carbon footprint. We share our experience with reducing paper usage by consolidating vaccine information sheets into a single use information sheet with quick response (QR) codes. We also share ideas for all workplaces to raise awareness of sustainability practices and to foster new ideas to address the climate crisis in both our professional and personal realms. These can help promote hope for the future and shift the collective mindset about climate action.

Keywords: sustainability, pediatric practice, climate change

Introduction – The Need for Environmental Action

Healthcare systems comprise nearly one-fifth of the United States economy, and collectively have a significant carbon footprint. They have been reported to be responsible for over 10% of annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1]. In addition, healthcare institutions are estimated to be responsible for 12% of acid rain, 10% of smog formation, 9% of criteria air pollutants (carbon monoxide, ground-level ozone, lead, nitrogen dioxide, particulate matter, and sulfur dioxide), 1% of stratospheric ozone depletion, and 1-2% of carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic air toxins [2]. US healthcare systems have increased GHG emissions over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2018, greenhouse gas emissions rose 6% [3]. This has resulted in the US having the highest rate of emissions among all high-income nations, totaling 1,692 kg per capita in 2018 [3]. Healthcare systems, which are intended to address health needs of individuals and communities, are unwittingly promoting pollution in the external environment at an alarming rate.

Quantifying the impact of healthcare systems on global GHG emissions is challenging because of poor compliance with sustainability reporting. Forty-nine of the largest US healthcare-related organizations (both for-profit and non-profit) failed to provide sustainability reports. Surprisingly, other kinds of large corporations have significantly higher rates of reporting sustainability data, compared to healthcare systems. For example, sustainability reports were published by 78% of companies on the Fortune 500, and 82% on the S&P 500, across all economic sectors, excluding healthcare. In comparison, only 12% of the 49 largest US healthcare systems as of 2015 and 2016 had reported their impacts on carbon footprints [4].

Efforts at Other Institutions

Fortunately, efforts to reduce carbon emissions and to promote green practices are currently ongoing in many healthcare institutions. For example, Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, WA has implemented a solar panel system which significantly reduced carbon emissions, cut energy costs, and provided life-saving power during emergencies [5]. Overlook Medical Center (Atlantic Health), Summit, NJ, lessened their impact on the environment by eliminating one million pounds of surgical blue wrap: this was found to be equivalent to taking 250 cars off the road. In 2019, their recycled tote bags prevented the use of 100,000 plastic bags, which saved the hospital $30,000 in waste handling costs. Moreover, they are repurposing their recycled blue wrap into sleeping bags for the homeless [5]. Finally, the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, adopted all-electric buses to transport patients, staff, and materials throughout the institution, thus reducing fuel costs and emission levels. Their future goal is to convert 2% of all parking spaces into electric vehicle stations [5]. These examples demonstrate a variety of institution-wide approaches to positive environmental change. The collective impact of these changes demonstrates not only benefits to the external environment, but institutional paybacks, both financial and social.

At a systems level, other institutions have demonstrated significant cost savings by adopting sustainability practices. In 2006, the Memorial Hermann Health System in the greater Houston, TX area established a baseline energy consumption audit at each hospital, and healthcare leaders identified opportunities to improve construction, training, and use of energy-smart technology [6]. The system implemented goals for energy reduction and reprogrammed their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. Memorial Hermann was innovative in creating healthy competition between the technician teams and staff, who vied to achieve the lowest level of energy consumption per square foot, while continuing to provide satisfaction to each customer. The system projected spending $3.8 million over 5 years to implement these new programs. By the end of 2 years, they already had immediate return on investment, and at 5 years they had saved a total of $47 million in utility reductions. Their efforts to increase energy efficiency increased their ENERGY STAR score from below the 40th percentile in 2008 to the 68th percentile in 2012 [6]. This example should convince other institutions to implement sustainability practices, which will reap long-term changes with co-benefits to the institution and the Earth.

Practicing healthcare providers may feel that they have limited agency to make changes in their clinical settings. We want to urge clinical settings to make changes that will require minimal effort but may also help to reduce pervasive eco-anxiety. Providers in healthcare practices such as our pediatric practice, care for patients who are underserved, and who are disproportionately affected by the climate crisis. We recognize that there is a complex interplay between social determinants of health and disproportionate burden of health effects due to climate change, which is not easy to remediate, but speaks to the intersection of environmental justice and underlying structural racism and health disparities [7]. Others have called attention to the urgency of clinician action regarding impact of the climate crisis on pediatric populations [8-10]. Medical education is shifting towards teaching trainees how to address the climate crisis and its health effects for their patients [11]. For this paper, however, we urge that our sense of helplessness can be replaced by optimism by promoting a sense of community and collaboration to promote sustainability practices. Clinicians and healthcare workers who are oriented to promoting sustainability can help infuse hope and action into daily clinical work.

Local Efforts

To address the collective desire to “do something” about the mounting problem of hospital waste and ongoing fossil fuel use, the Golisano Pediatric Practice (Strong Memorial Hospital) at the University of Rochester, Rochester, NY, created a “Green and Clean Sustainability Team” to reduce waste and promote sustainability inside and outside our clinical space. The team is comprised of pediatricians, nurse practitioners, nurses, secretarial staff, environmental services staff, and administrators who meet by Zoom or in-person. Specific action items that we identified were excessive paper waste, lack of recycling bins, and limited education on sustainability.

Our stepwise approach to promoting sustainability required a needs-assessment of current practices. We first obtained recycling bins for our clinical and non-clinical spaces and arranged for environmental services to assist us with collection of materials. We made a commitment to recycle all items that could be recycled, including cans and bottles. We placed these recycling bins in easily accessible locations that would encourage compliance; however, we discussed the importance of making sure that recycled paper items did not include any confidential patient information, and we also place our recycling bins near the locked bin reserved for confidential patient materials.

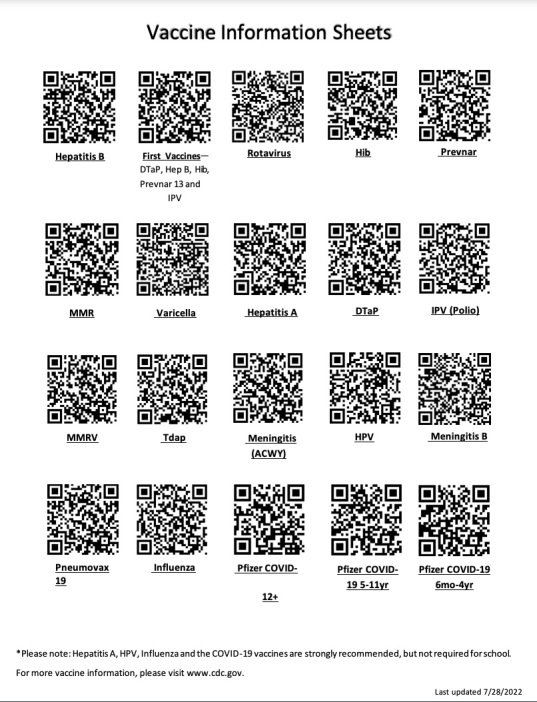

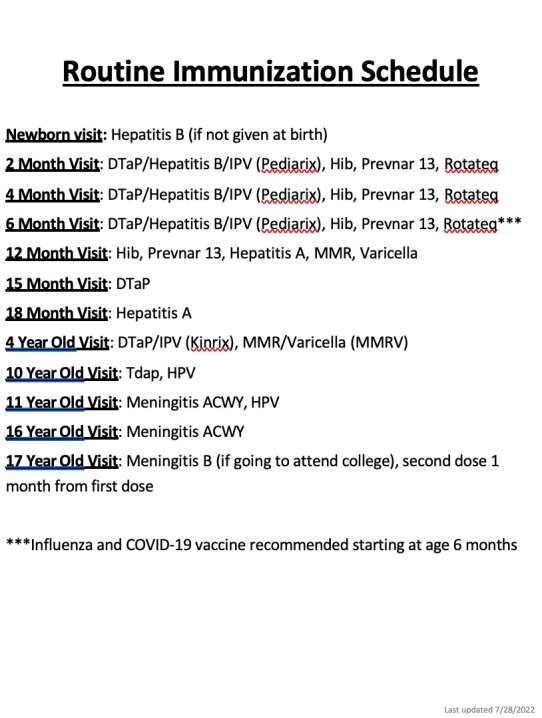

We next assessed paper forms that were printed in color and could be changed to electronic format or printed in black and white. In particular, we targeted immunization information sheets that included two color-printed pages of information per vaccine administered. Providers and nursing staff noted that patients and families usually did not read these multi-colored information sheets, either leaving them in the room or throwing them in the garbage, not in the recycling bins. In response, we piloted use of a single sheet that compiled quick response (QR) codes linking each vaccine to an electronic vaccine information sheet and having this all consolidated on a single sheet of black and white paper (Figure 1). For example, for a one-year-old child, who routinely receives five or six vaccines, we were able to replace six pages of double-sided color-printed information with a single sheet, on which the provider circled the relevant QR codes for the parent. On the back side of the single sheet of black and white paper with QR codes for vaccine information sheets, we listed the vaccine administration schedule by age. This was helpful because parents could take this single sheet of paper home, and anticipate what vaccines were needed by the child at a particular age (Figure 2). This method of consolidating vaccine information sheets by using QR codes enables our office to update vaccine information with ease when new vaccines are given (for example, the COVID vaccine or booster, or seasonal influenza vaccine). This also reduces paper waste, because we can update vaccine information with the most current versions. These documents are available for use in both English and Spanish. They are easily updated with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations.

Figure 1.

Vaccine information sheets.

Figure 2.

Routine immunization schedule.

Upon review of our documentation in the New York State Immunization Information System, in 2022, our pediatric office administered 19,350 individual vaccines and 4,328 COVID vaccines. In our pediatric office, prior to implementing this change in reducing paper usage, this would have involved distribution of approximately 23,678 pages of color-printed paper (front/back). Using estimates on number of patients seen in our pediatric practice, which is the largest pediatric practice in Rochester, we estimated that in 2022, we would have given 87,810 vaccine information sheets. This data is based upon a review of the number of routine well-child examinations in our practice for 2022, which was 14,418 patients. Using the CDC Recommended Immunization schedule, we estimated this number of vaccines would have been given if all patients were compliant with recommended vaccines at their routine well-child examinations. Since initiation of this project, we have markedly reduced usage of paper for distribution of vaccine information sheets, as we now have a single laminated (front/back, Figure 1 and Figure 2) paper which is displayed in every examination room and has the QR codes, which families can scan with their phone to review vaccine information, as is required by federal law. For caregivers who request paper copies of the vaccine information forms, we still have this available, but we have found that now that this information is readily available electronically, families are not requesting additional paper-based forms.

In the future, additional initiatives to promote sustainability practices are being planned. Our Green and Clean Sustainability Team makes regular 5-minute updates at our clinic-wide meetings to share information and remind our staff to implement greener habits, such as using recycling bins, reducing paper use, and encouraging the carrying of reusable water bottles.

Our Green and Clean Sustainability Team has shared our new methods with the larger pediatric practice workgroup, which operates the largest pediatric practice in Rochester, NY, serving over 14,000 children. We have also shared ideas with colleagues in other institutions about how to reduce waste in the workplace. We are also working with the University of Rochester Medical Center Medical Student Sustainability Team (MSST) to identify joint projects, such as promoting restoration of the public market hosted at the medical center (closed due to COVID). We have also joined a project to promote gardening in collaboration with another medical center. They have set up a demonstration garden in their clinical space to teach families how to grow their own vegetables.

To promote health and sustainability in our home and workplaces, our Green and Clean Sustainability Team is promoting public education and disseminating information on green living. We have posted informational flyers in public places, such as on our staff refrigerator and in the bathrooms, on the importance of limiting water usage and making sustainable eating choices, such as plant-based, locally sourced food that can reduce GHG emissions by avoiding long-distance transportation. Clinicians across healthcare institutions can do a life-cycle analysis to assess how the healthcare sector can reduce its emissions [12,13]. We join others in climate action to draw attention to lowering healthcare’s carbon footprint [14,15]. As clinicians, we are charged with encouraging our patients to make healthy choices in response to the climate crisis, although many of our patients, especially those who are underserved, are least responsible for greenhouse gas emissions but are disproportionately affected by health effects related to climate change.

Conclusions and Outlook

In an effort to foster sustainability in the workplace, our Green and Clean Sustainability Team found the following effective: 1) forming an interdisciplinary team of like-minded individuals who are interested in promoting sustainability, 2) setting goals to enhance sustainability in the workplace, ours included increasing recycling and decreasing paper usage, 3) piloting changes and evaluating effectiveness through a quality improvement process (eg, Plan/Do/Study/Act cycle) as demonstrated with our VIS QR sheet project, which is now a single laminated form available in patient rooms and electronically, 4) sharing successes (and failures) of the workflow changes with the larger work community, eliciting their feedback, and to engaging colleagues in the joint mission of promoting sustainability through updates at clinic wide meetings, and 5) disseminating and sharing ideas broadly, in both academic and community settings by distributing informational flyers in common spaces. This approach can educate others about the climate crisis and help to allay eco-anxiety by promoting mitigation actions.

Our goal with this strategy is to promote the responsibility of healthcare systems in being stewards of the earth. We are not proposing the steps we have initiated will alone have a measurable impact on reducing GHG emissions, but it is a starting place. By sharing our process, we hope other healthcare centers may come to realize how re-evaluating their daily workflow processes through a sustainability lens can impact the collective carbon footprint from healthcare institutions. Through collective action and purposeful choices, healthcare systems that currently contribute significantly to carbon emissions can become part of the solution for a better future.

Acknowledgments

There was no funding source for this manuscript. Sandra Jee gratefully acknowledges support from the NYS Children’s Environmental Health Center Network. Authors acknowledge comments by Constance D. Baldwin, PhD on an earlier draft of this manuscript, and Sarah Rizzo, RN for technical assistance with vaccine information sheets.

Glossary

- GHG

greenhouse gas

- QR

quick response

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

- Carroll L. Healthcare not very green compared to other industries. Healthcare and Pharma. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-hospitals-sustainability/healthcare-not-very-green-compared-to-other-industries-idUSKBN1KR23D. 2018. Accessed 12 Nov 2022.

- Eckelman MJ, Sherman J. Environmental Impacts of the U.S. Health Care System and Effects on Public Health. PLoS One. 2016. Jun;11(6):e0157014. 10.1371/journal.pone.0157014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, Senay E, Dubrow R, Sherman JD. Health Care Pollution And Public Health Damage In The United States: an Update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020. Dec;39(12):2071–9. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senay E, Landrigan PJ. Assessment of Environmental Sustainability and Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting by Large Health Care Organizations. JAMA Netw Open. 2018. Aug;1(4):e180975–180975. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Practice Greenhealth 25 Hospitals Setting the Standard for Sustainability in Health Care. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://practicegreenhealth.org/about/news/25-hospitals-setting-standard-sustainability-health-care. Accessed 12 November 2022

- Health Research & Educational Trust (2014, May). Environmental sustainability in hospitals: The value of efficiency. Chicago, IL: Health Research & Educational Trust. Accessed at www.hpoe.org on 13 November 2022

- Gutschow B, Gray B, Ragavan MI, Sheffield PE, Philipsborn RP, Jee SH. The intersection of pediatrics, climate change, and structural racism: ensuring health equity through climate justice. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2021. Jun;51(6):101028. 10.1016/j.cppeds.2021.101028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson JA, Ahdoot S, Baum CR, Bole A, Brumberg HL, Campbell CC, et al. COUNCIL ON ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH Global Climate Change and Children’s Health. Pediatrics. 2015. Nov;136(5):992–7. 10.1542/peds.2015-3232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Sheffield PE, Hu W, Su H, Yu W, Qi X, et al. Climate change and children’s health—a call for research on what works to protect children. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012. Sep;9(9):3298–316. 10.3390/ijerph9093298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng SZ, Jalaludin BB, Antó JM, Hess JJ, Huang CR. Climate change, air pollution, and allergic respiratory diseases: a call to action for health professionals. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020. Jul;133(13):1552–60. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillai P, Patz JA, Seibert CS. Climate chane and environmental health must be integrated into medical education. Acad Med. 2021. Nov;96(11):1501–2. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew J, Christie S D, Tyedmers P, Smith-Forrestor J, Rainham D. Operating in a climate crisis: a state-of-the science review of life cycle assessment within surgical and anesthetic care. Environ Health Persepct. 2021; 129(7):076001. https://doi.org/ 10.1289/EHP8666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richie, Cristina. Environmental sustainability and the carbon emissions of pharmaceuticals. J Med Ethics. (2022):48(5):334-337. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/medethics-2020-106842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess JJ, Salas RN. Invited Perspective: Life Cycle Analysis: A Potentially Transformative Tool for Lowering Health Care’s Carbon Footprint. Environ Health Perspect. 2021. Jul;129(7):71302. 10.1289/EHP9630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson T, Ballard T. Sustainable medicine: good for the environment, good for people. Br J Gen Pract. 2011. Jan;61(582):3–4. 10.3399/bjgp11X548875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]