ABSTRACT

Opportunistically pathogenic fungi have varying potential to cause disease in animals. Factors contributing to their virulence include specialized metabolites, which in some cases evolved in contexts unrelated to pathogenesis. Specialized metabolites that increase fungal virulence in the model insect Galleria mellonella include the ergot alkaloids fumigaclavine C in Aspergillus fumigatus (syn. Neosartorya fumigata) and lysergic acid α-hydroxyethylamide (LAH) in the entomopathogen Metarhizium brunneum. Three species of Aspergillus recently found to accumulate high concentrations of LAH were investigated for their pathogenic potential in G. mellonella. Aspergillus leporis was most virulent, A. hancockii was intermediate, and A. homomorphus had very little pathogenic potential. Aspergillus leporis and A. hancockii emerged from and sporulated on dead insects, thus completing their asexual life cycles. Inoculation by injection resulted in more lethal infections than did topical inoculation, indicating that A. leporis and A. hancockii were preadapted for insect pathogenesis but lacked an effective means to breach the insect’s cuticle. All three species accumulated LAH in infected insects, with A. leporis accumulating the most. Concentrations of LAH in A. leporis were similar to those observed in the entomopathogen M. brunneum. LAH was eliminated from A. leporis through a CRISPR/Cas9-based gene knockout, and the resulting strain had reduced virulence to G. mellonella. The data indicate that A. leporis and A. hancockii have considerable pathogenic potential and that LAH increases the virulence of A. leporis.

IMPORTANCE Certain environmental fungi infect animals occasionally or conditionally, whereas others do not. Factors that affect the virulence of these opportunistically pathogenic fungi may have originally evolved to fill some other role for the fungus in its primary environmental niche. Among the factors that may improve the virulence of opportunistic fungi are specialized metabolites––chemicals that are not essential for basic life functions but provide producers with an advantage in particular environments or under specific conditions. Ergot alkaloids are a large family of fungal specialized metabolites that contaminate crops in agriculture and serve as the foundations of numerous pharmaceuticals. Our results show that two ergot alkaloid-producing fungi that were not previously known to be opportunistic pathogens can infect a model insect and that, in at least one of the species, an ergot alkaloid increases the virulence of the fungus.

KEYWORDS: lysergic acid amides, preadaptation, accidental pathogenesis, Aspergillus, ergot alkaloids

INTRODUCTION

Fungal pathogenesis of animals often is opportunistic or accidental, with traits that are selected in fungi in their primary environmental niches translating as virulence factors when fungi enter animals (1–3). For example, the ability to grow at mammalian body temperatures has likely evolved in certain accidental pathogens, including several Aspergillus species, because of the high temperatures reached during decomposition of vegetation by these fungi. This ability to grow at elevated temperature then contributes to the pathogenic potential of these fungi, preadapting them to overcome mammalian body temperature as a barrier to colonization (1, 2). Similarly, factors such as melanin and gliotoxin that help Aspergillus fumigatus (synonym Neosartorya fumigata) escape or overcome phagocytosis by amoebae in its primary environmental niche help this fungus escape phagocytosis by cells of the innate immune systems encountered when the fungus is introduced into animals (4–7). Thus, virulence factors in opportunistically pathogenic fungi frequently evolve in contexts separate from the host in which these factors contribute to virulence.

Among the several model hosts used in studies of fungal pathogenesis of animals, larvae of the lepidopteran insect Galleria mellonella offer the advantages of low cost, ease of including large numbers of replicates per trial, and the lack of institutional regulation required for vertebrate models (8–12). Pathogenic potential of several Aspergillus species and the contributions of potential virulence factors have been studied in G. mellonella (13–19). Among the factors contributing to virulence of the opportunistic pathogen A. fumigatus in this model system are ergot alkaloids, primarily fumigaclavine C (20). Aspergillus fumigatus does not commonly parasitize insects under natural conditions; thus, the effect of fumigaclavine C on virulence of A. fumigatus to G. mellonella may be coincidental to the function of this compound in the fungus’s native niche. Aspergillus fumigatus has been listed as an occasional cause of stonebrood disease of honey bees (Apis mellifera), with Aspergillus flavus being the primary cause (21, 22). Foley et al. (21) found A. fumigatus associated with honey bee hives but neither of two tested isolates caused disease on honey bee larvae that were topically inoculated with conidia, indicating that A. fumigatus does not have an effective means of entering an insect.

In contrast to A. fumigatus, many species of the genus Metarhizium are well-adapted insect pathogens that enter insects via appressoria and sporulate profusely on dead insects (23–25). Metarhizium species are aided in pathogenesis by several specialized metabolites (26, 27), including the ergot alkaloid lysergic acid α-hydroxyethylamide (LAH) (28). LAH is the product of a different branch of the ergot alkaloid pathway relative to the branch producing fumigaclavine C in A. fumigatus (Fig. 1) (29). Phylogenetic studies indicate that M. brunneum and other ergot alkaloid-producing members of the family Clavicipitaceae evolved from an insect-infecting ancestor (30), suggesting that ergot alkaloids in this lineage of fungi may be anti-insect adaptations maintained in certain members of this family.

FIG 1.

Critical intermediates and products of the lysergic acid amide pathway. Genes controlling or hypothesized to control relevant steps are indicated. The pathway branch to fumigaclavine C, as occurs in A. fumigatus, is shown in gray. The step to ergine is shown with a dashed arrow because ergine is hypothesized to form spontaneously by hydrolysis in other fungi (35, 54, 55). iso, isomerase; red, reductase; DMAPP, dimethylallyl-pyrophosphate; Trp, tryptophan.

High concentrations of LAH and lesser amounts of other lysergic acid amides were recently discovered outside of the family Clavicipitaceae in three species of Aspergillus (31). One of the species, A. leporis, was originally isolated from jackrabbit dung (32), and the other two, A. hancockii and A. homomorphus, were isolated from soil in Australia (33) and Israel (34), respectively. These Aspergillus species produce predominantly LAH, with smaller amounts of other lysergic acid amides (31), making their ergot alkaloid profiles similar to that of the entomopathogen M. brunneum. Considering the role of LAH in insect pathogenesis by M. brunneum (28), we investigated the pathogenic potential of the LAH-producing Aspergillus species in G. mellonella and the potential contribution that LAH may make to their virulence.

RESULTS

Pathogenic potential of Aspergillus species.

When injected into larvae of G. mellonella, A. leporis, and A. hancockii killed insects at a higher rate than A. homomorphus and the negative phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) control (Fig. 2A). Aspergillus leporis-inoculated larvae died at the highest rate. The survival rate for A. homomorphus-injected larvae was not significantly different from the survival rate of larvae injected with the PBS solution alone, indicating A. homomorphus has little pathogenic potential. Aspergillus leporis and A. hancockii both emerged from infected larvae and sporulated well on cadavers (Fig. 2B to D). Sclerotia of A. hancockii, resembling those formed in culture, formed on several cadavers (Fig. 2D and E). The consistent emergence and abundant reproduction on their insect hosts separated A. leporis and A. hancockii from the well-studied opportunistic pathogen A. fumigatus, which kills larvae of G. mellonella after injection but emerges rarely and conidiates only sparsely on dead insects (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

Pathogenic potential of three lysergic acid amide-producing species of Aspergillus on G. mellonella larvae. (A) Survival of larvae inoculated by injection of 20 μL of PBS containing 3,000 conidia/μL of the indicated species. The PBS control contained no fungal conidia. Survival curves contain data compiled from three independent trials and are marked with different letters when they differed significantly in log-rank tests (with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha set at 0.0083). (B and C) Aspergillus leporis emerging from and conidiating on dead larvae. (D) Aspergillus hancockii conidiating on a dead larva and forming sclerotia. (E) Sclerotia formed by A. hancockii in culture for comparison. Scale bars (B to E), 5 mm. The photos in panels B to E were taken 2 weeks after inoculation. (F) Survival of larvae inoculated by exposure to conidiating cultures of the indicated fungi. Data were compiled from three trials and were analyzed as described above for injected larvae.

When G. mellonella larvae were inoculated topically, by exposure to conidia and hyphae of the Aspergillus species for 24 h on agar-based cultures, fewer insects died from infection than in the injection trials (Fig. 2). Insects exposed to A. leporis and A. hancockii died at a higher rate than those exposed to A. homomorphus and those not exposed to fungal cultures (Fig. 2F). The differences in survival of larvae injected with A. leporis or A. hancockii compared to those exposed to cultures of these two fungi suggest that these Aspergillus species have pathogenic potential but lack effective means of entering an insect. During their time on cultures of the fungi, G. mellonella larvae were observed eating mycelia of the fungi (see Video S1 in supplemental material). This behavior may have provided a means of entry of the fungus into the insect; wounds or natural openings provide other possible modes of entry. Insects from two other orders––adult banded crickets (Gryllodes sigillatus [Orthoptera]) and meal worms (larvae of the beetle Tenebrio molitor [Coleoptera])––also were exposed to conidiating cultures of A. leporis, A. hancockii, and A. homomorphus. No infections were observed, indicating that although A. leporis and A. hancockii have pathogenic potential on the lepidopteran G. mellonella, these fungi may lack a mechanism to infect these other insects. Potential reasons may be related to taxonomy, anatomy (e.g., cuticle thickness), or behavior (e.g., lack of consumption).

Accumulation of ergot alkaloids in larvae inoculated with Aspergillus species.

Larvae of G. mellonella killed by the Aspergillus species accumulated ergot alkaloids. Abundant lysergic acid amides (LAH and ergine) were detected in insects infected with A. leporis, with significantly smaller amounts detected in larvae inoculated with A. hancockii (Table 1). Larvae of G. mellonella were rarely killed by A. homomorphus, but two dead larvae resulting from A. homomorphus infections were examined for ergot alkaloids, and each contained modest quantities (relative to those accumulating in A. leporis-infected larvae) of LAH and its degradation product, ergine (Table 1). Several live insects that had been inoculated with A. homomorphus also were analyzed for ergot alkaloids with negative results. In an additional experiment with A. leporis, insects that were dead (as a result of freezing) at the time of inoculation accumulated ergot alkaloids to concentrations that were slightly lower than, but not significantly different from, those observed when larvae were alive at the time of inoculation with A. leporis (Table 1). These data contrast with results from a similar experiment conducted previously with M. brunneum in which G. mellonella larvae that were alive at inoculation elicited >10-fold higher concentrations of ergot alkaloids than did larvae that were dead at the time of inoculation (35).

TABLE 1.

Accumulation of ergot alkaloids 8 days postinoculation of Aspergillus species into G. mellonella larvae

| Species | n | Mean concn (ng/larva) ± SEa |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAHb | Ergine | Total | ||

| A. leporis | 16 | 3,964 ± 672A | 254 ± 59A | 4,218 ± 724A |

| A. hancockii | 6 | 9 ± 1B | 2 ± 1B | 11 ± 2B |

| A. homomorphus | 2 | 110 ± 27AB | 158 ± 85AB | 268 ± 113AB |

| Dead larvae injected with A. leporis | 10 | 1,678 ± 763A | 74 ± 25A | 1,752 ± 442A |

Mean separations, indicated by different superscript capital letters, were assessed by using the Steel-Dwass multiple-comparison test (alpha = 0.05) and apply only within columns.

LAH and ergine values were calculated from the sums of stereoisomers and are based on the fluorescence relative to ergonovine.

All three species of Aspergillus studied were capable of growing in culture at 37°C, though each species grew best at 30°C among the temperatures tested (Table 2). LAH accumulated most abundantly in cultures of the fungi grown at 30°C and were detected at 37°C only in cultures of A. homomorphus, which showed the least pathogenic potential in studies with G. mellonella. One survival trial was conducted as described above but with insects incubated at 37°C after inoculation. As with the room temperature trials, A. leporis reduced survival at the greatest rate, followed by A. hancockii (see Fig. S2). Survival of larvae inoculated with A. homomorphus was again not different from the that of the PBS-injected control larvae. At this elevated temperature, larvae infected with A. leporis contained only 3 ng (±1 ng standard error [SE]) of lysergic acid amides and those infected with A. hancockii contained 1 ng (±0.5 ng SE) lysergic acid amides.

TABLE 2.

Colony diameters and LAH accumulations in Aspergillus species grown at different temperatures

| Aspergillus species | Temp (°C) | Mean ± SEa |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Colony diam (mm), day 4 | LAH concn (μM), day 6b | ||

| A. leporis | 20 | 23 ± 0.6 | 8 ± 0.2 |

| 30 | 42 ± 0.9 | 15 ± 1.7 | |

| 37 | 25 ± 1.9 | ND | |

| A. hancockii | 20 | 28 ± 0.3 | ND |

| 30 | 50 ± 1.0 | 2 ± 0.8 | |

| 37 | 26 ± <0.1 | ND | |

| A. homomorphus | 20 | 40 ± 0.9 | 168 ± 23.7 |

| 30 | 69 ± 1.9 | 356 ± 21.7 | |

| 37 | 33 ± 0.7 | 226 ± 11.5 | |

The means of three determinations are shown. ND, not determined.

Values were calculated from the sums of stereoisomers and are based on the fluorescence relative to ergonovine.

Effects of LAH on virulence of A. leporis to G. mellonella.

To test the effects of lysergic acid amides on virulence of A. leporis, a CRISPR-Cas9-derived knockout was made in the easD gene of A. leporis. This fungus and gene were selected for mutation for several reasons: (i) we had developed a genetic transformation system for A. leporis but not for the other Aspergillus species; (ii) A. leporis was more virulent and produced significantly higher concentrations of ergot alkaloids in insects compared to the other Aspergillus species tested (Fig. 2 and Table 1); (iii) easD is the only single-copy ergot alkaloid synthesis gene in the two LAH-associated gene clusters of A. leporis (31); and (iv) knockout of easD should block synthesis of LAH, which had been observed to contribute to virulence of the entomopathogen M. brunneum (28).

Transformants in which easD was knocked out were found by a PCR screen spanning the target site for the mutagenic sgRNA. Two colonies contained target site amplicons of greater length than that obtained from wild-type A. leporis (see Fig. S3), indicating insertion of a DNA fragment into the target site during repair of the Cas9-cut locus, a phenomenon we had observed routinely when applying a similar mutagenesis strategy in M. brunneum (28, 36, 37). One particular easD mutant chosen for further study (easD ko 1) had a 2.1-kb increase in the length of the target site amplicon. Sanger sequencing of that amplicon indicated that Cas9 had cut at the target site (3 bp on the 5′ side of the PAM site) and that a fragment of the phleomycin resistance-conferring plasmid (which had been cotransformed as a selectable marker) had been integrated into the cut site during repair (see Fig. S3). This recombination event disrupted easD in such a way as to reduce or eliminate its function, as supported by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of ergot alkaloids in the easD knockout strain compared to wild-type A. leporis (Fig. 3). The mutant strain lacked detectable LAH and ergine, which were abundant in the wild type extract, but accumulated higher concentrations of chanoclavine-I, the substrate for EasD (Fig. 1 and 3).

FIG 3.

High-performance liquid chromatograms of extracts from cultures of A. leporis, an easD knockout mutant of A. leporis, and authentic standard for chanoclavine-I. Analytes were analyzed by fluorescence with excitation at 310 nm and emission at 410 nm to detect lysergic acid amides (upper panel) and with excitation and emission at 272 nm/372 nm to detect chanoclavine-I (lower panel). LAH, lysergic acid alpha-hydroxyethylamide. Lysergic acid derivatives stereoisomerize in protic solvents leading to detection of multiple peaks, as indicated.

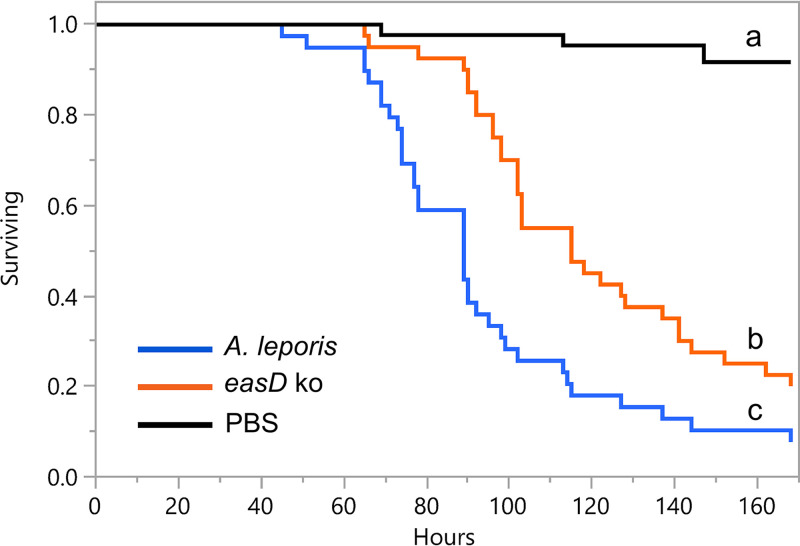

To test the effects of lysergic acid amides on the virulence of A. leporis, the A. leporis easD knockout mutant and the LAH-accumulating, wild-type strain were injected into larvae of G. mellonella, and larval survival was monitored for 1 week. Larvae injected with the easD mutant strain died at a significantly lower rate than did larvae injected with the wild type (P < 0.0001, with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha = 0.016) (Fig. 4). Survival rates for both strains of A. leporis were significantly different from that of the PBS-injected, control larvae (P < 0.0001). The virulence assays were repeated in two trials conducted at a lower inoculum concentration (injections of 20 μL containing 250 conidia/μL as opposed to 3,000 conidia/μL), and the easD mutant was again significantly less virulent than the wild type (P = 0.0002, with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha = 0.0016) (see Fig. S4).

FIG 4.

Survival curves for larvae of G. mellonella inoculated by injection with A. leporis (blue line c) or an easD knockout mutant (orange line b) of A. leporis. The PBS control (black line a) contained no fungal conidia. Survival curves contain data compiled from three independent trials with larvae inoculated with 20 μL of PBS containing 3,000 conidia/μL. Curves marked with different letters differed significantly in log-rank tests (with Bonferroni-adjusted alpha set at 0.016).

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that A. leporis and A. hancockii have considerable pathogenic potential and that lysergic acid amides contribute to the pathogenic potential of A. leporis. Aspergillus leporis and A. hancockii killed larvae of G. mellonella when injected, and both fungi emerged from and sporulated on insect cadavers. The profuse sporulation of A. leporis and A. hancockii after killing injected larvae demonstrates their ability to complete their asexual life cycles in an insect. Considering the lower rate of infection by A. leporis and A. hancockii when its host was naturally inoculated, the only trait separating these fungi from successful, natural insect pathogens appears to be their inability to efficiently breach the insect cuticle. Aspergillus leporis, and to a lesser extent the other Aspergillus species, produced ergot alkaloids in infected insects. The concentration of lysergic acid amides detected in A. leporis-infected larvae (4.2 μg/larva) was comparable to those recorded by Leadmon et al. (35) for the insect pathogen M. brunneum (5.5 μg/larva) at the same, 8-day time point. An additional Aspergillus species, A. homomorphus, which had accumulated high concentrations of ergot alkaloids in vitro (31), had very little pathogenic potential in the present study, indicating that the capacity to produce ergot alkaloids is not sufficient for conferring pathogenic potential and that A. leporis and A. hancockii must have additional traits preadapting them for success in insects.

Very little research has been done previously on the ecology of the three Aspergillus species studied here. Aspergillus leporis has not been reported previously to be pathogenic to animals, but it has been associated with the digestive system of rabbits. It was originally isolated from freshly deposited dung of a white-tailed jackrabbit (Lepus townsendii) (32), and in subsequent experiments it was fed to a laboratory rabbit in an agar-based coating of pelletized food, passed through the digestive system of the rabbit, and conidiated and formed sclerotia on resulting dung pellets (38). Leporin A, an anti-insect compound, was isolated from sclerotia of A. leporis that had been grown in culture (39), but the literature contains no information on the interaction of A. leporis with insects. Aspergillus leporis also has been isolated from multiple samples of arid soils in Wyoming (40).

Aspergillus hancockii, whose genome encodes theoretical biosynthetic capacity for 75 specialized metabolites, has been isolated from soil in Australia as well as from dried peas (33), but the literature is lacking reports on its ecology. Aspergillus leporis and A. hancockii both belong to Aspergillus section Flavi. The type species for this section, Aspergillus flavus, has been reported as a pathogen of several insects (13, 14, 21, 41). St Leger et al. (13) reported that isolates of A. flavus from a variety of sources infected G. mellonella upon injection and that the resulting dead larvae erupted with conidiating colonies of A. flavus. In other studies, isolates of A. flavus were reported to infect insects after topical inoculation (14, 21, 41) and ingestion (21), indicating that A. flavus has superior ability to infect intact insects than do the Aspergillus species from the present study.

Aspergillus homomorphus was isolated from soil near the Dead Sea (34) and was formally described several years later (42). Another isolate of this species was later obtained from millet grain in Yemen (43). We are not aware of any published ecological studies with A. homomorphus. An isolate of Aspergillus niger, the type species for Aspergillus section Nigri (to which A. homomorphus belongs), was unable to cause disease on honey bee larvae (21).

Knocking out easD inhibited A. leporis from accumulating LAH and reduced virulence of the fungus to larvae of G. mellonella. The degree of reduction in virulence was modest and similar to that observed when LAH was eliminated from M. brunneum (28), with mutations in both species delaying the median time of death by about 26 h. The function of EasD as the enzyme that oxidizes the primary alcohol of the ergot alkaloid pathway intermediate chanoclavine-I to the aldehyde of chanoclavine-I aldehyde had been established by in vitro expression studies by Wallwey et al. (44), who called easD of A. fumigatus fgaDH. The ergot alkaloid profile of our easD knockout mutant is consistent with the data presented by Wallwey et al. (44). The observation that all other genes in the pathway to LAH in A. leporis were present in two copies (31), along with the position of easD at an early point in the pathway, made easD a reasonable target for mutagenesis to inhibit accumulation of lysergic acid amides. Moreover, chanoclavine-I, the pathway intermediate accumulating in the easD knockout strain, has not been demonstrated to have strong anti-insect effects in previous studies. Potter et al. (45) found that perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) infected with a strain of an Epichloë endophyte that accumulated predominantly chanoclavine-I but no lysergic acid derivatives was significantly less toxic to black cutworm (Agrotis ipsilon) than was a symbiotum comprised of perennial ryegrass and a strain of the same Epichloë species accumulating the lysergic acid derivatives ergovaline and ergine in addition to chanoclavine-I. Similarly, Hudson et al. (46) showed that perennial ryegrass-Epichloë symbiota accumulating clavines (predominantly chanoclavine-I) were less effective in protecting perennial ryegrass from feeding damage by African black beetle (Heteronychus arator) than were strains of Epichloë producing ergovaline in addition to clavines.

Our genetic analysis of the role of ergot alkaloids in virulence focused on A. leporis because it produced the highest concentrations of lysergic acid amides in infected insects and because we had established a genetic transformation system for that species. The relatively low concentration of lysergic acid amides detected in larvae infected with A. hancockii were consistent with the relative quantities detected in cultures of these fungi (31) and suggests these compounds are less likely to play a significant role in the virulence of that fungus to insects. Perhaps A. hancockii is aided in its virulence (which was, in fact, lower than that observed for A. leporis) by specialized metabolites additional to, or other than, lysergic acid amides. The genome of A. hancockii contains at least 75 biosynthetic gene clusters for predicted specialized metabolites (including 26 encoding polyketide synthases and 16 encoding nonribosomal peptide synthetases), many of which appear to encode novel metabolites (33). Indeed 11 of the 15 most abundant specialized metabolites detected in A. hancockii cultured on rice grains were new to science (33). Among the previously described specialized metabolites produced by this species were 7-hydroxytrichothecolone, a potentially bioactive trichothecene (33, 47), and aflavarin (47), a compound with anti-insect activities (48).

Ergot alkaloids from the lysergic acid branch of the pathway have been documented to have activities against insects in several additional studies. Gene knockout studies with M. brunneum (28) showed that particular Metarhizium species uses ergot alkaloids (specifically LAH) as a weapon against insects. The observation that several other Metarhizium species produce LAH during insect pathogenesis (35) suggests this trait may be common in fungi of this genus. Studies by Potter et al. (45) and Hudson et al. (46), described above, demonstrated anti-insect effects of lysergic acid derivatives of Epichloë species symbiotic with grasses. Similarly, ergopeptine and amide derivatives of lysergic acid that accumulate in Periglandula species symbiotic with morning glories also have anti-insect effects (49, 50). In these plant-fungus symbioses, the fungi are not infecting insects; rather their interactions are indirect in that the fungus has colonized the plant, and the insects are feeding on the plants. The results of these studies do, nonetheless, support the hypotheses that lysergic acid derivatives can adversely affect insects and that members of the Clavicipitaceae maintain ergot alkaloids, at least in part, because these compounds contribute to the ability of the fungi to acquire (in the case of Metarhizium species) or preserve (in the case of Epichloë and Periglandula species) important resources.

An ergot alkaloid from a different branch of the pathway, compared to that resulting in the lysergic acid derivatives, increases the pathogenic potential of A. fumigatus. Aspergillus fumigatus produces fumigaclavine C, and elimination of this compound reduced the virulence of the fungus to larvae of G. mellonella (20). Although A. fumigatus must certainly encounter and interact with insects in its natural environment, it is not a well-established insect pathogen. The data suggest that although fumigaclavine C preadapts the fungus to have greater pathogenic potential, this ergot alkaloid probably contributes to the success of A. fumigatus in some other way in its primary habitat of decaying vegetation.

Ergot alkaloids have been observed in fungi occupying a variety of ecological niches, including pathogens of plants, mutualistic symbionts of plants, pathogens of insects, and saprotrophs. Since A. leporis and A. hancockii have not been reported as pathogens of insects under natural conditions (presumably because their difficulty in entering a living insect), the effect that lysergic acid amides have in A. leporis-insect interactions may be considered a preadaptation that increases their pathogenic potential. The data from studies on M. brunneum (28, 35) and the present study on Aspergillus species indicate that LAH is a versatile compound that can benefit fungi occupying a variety of ecological niches.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungi and culture conditions.

Aspergillus leporis NRRL 3216 (CBS 151.66) (representing the type specimen) was obtained from the U.S. Departmental of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service’s culture collection (NRRL; Peoria, IL). Cultures representing the type specimens of A. hancockii (CBS 142002; originally called FRR 3425) and A. homomorphus (CBS 101889) were obtained from the culture collection of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (Utrecht, The Netherlands). Cultures of all three species were maintained on sucrose-yeast extract agar (20 g sucrose, 10 g yeast extract, 1 g magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, and 15 g agar per L) at room temperature.

Inoculation of insects.

Larvae of the model insect G. mellonella were purchased from Josh’s Frogs (Owosso, MI) and injected with conidia (20 μL at 3,000 conidia/μL or, in one experiment, 250 conidia/μL) of A. leporis, A. hancockii, and A. homomorphus according to previously described methods (20, 35). Unless otherwise noted, data were derived from at least three independent trials with 12 to 15 larvae per treatment per trial. Larvae were injected with conidial suspensions with the aid of a 29-gauge insulin syringe. Control groups of 12 to 15 larvae per trial were injected with 20 μL of PBS solution lacking Aspergillus spores. Injected larvae were incubated at room temperature (or in one trial at 37°C) and observed for 1 to 2 weeks following inoculation; any dead larvae were removed throughout this observation period. Larvae that died from bacterial infection (as evidenced by dark, soft, putrescent cadavers) were excluded from counts. Among the 12 or 15 larvae injected in each treatment of each trial, the number of larvae excluded due to bacterial infection ranged from 0 to 4, with a median of 0 and a mean of 0.6. Insects also were inoculated topically by placing larvae on sporulating cultures of the three Aspergillus species grown on sucrose-yeast extract agar for 24 h before removing them to empty petri dishes. Insects inoculated through this topical, or natural, approach were observed for 16 days following inoculation. Additional insects inoculated by exposure to sporulating cultures included adult banded crickets (Gryllodes sigillatus) and meal worms (larvae of Tenebrio molitor) obtained from Ghann’s Crickets Farm (Martinez, GA).

Analysis of ergot alkaloids.

Alkaloids were extracted from individual larvae 8 days postinoculation by bead beating in 1 mL of methanol as described previously (28, 35). Alkaloids also were extracted from fungi cultured on sucrose-yeast extract agar medium for at least 6 days at room temperature, at 30°C, or at 37°C. Samples (400 μL, containing the hyphae and spores of the fungus and the supporting agar medium) were combined with 400 μL of methanol, rotated end-over-end (~40 rpm) for 30 min, and then centrifuged for 10 min for clarification. Extracts (20 μL) were analyzed by HPLC with fluorescence detection as described previously (28, 51). Fluorescence of lysergic acid derivatives was detected by exciting analytes at 310 nm and measuring emission at 410 nm; chanoclavine-I, which has a different double bond structure in its ring system, was detected with fluorescence settings of 272 nm/372 nm. The identity of the peak corresponding to chanoclavine-I was confirmed by comparison to an authentic standard (obtained from Alfarma, Prague, Czech Republic) and by previous experiments using liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (52). Identities of peaks containing lysergic acid amides were determined in previously published LC-MS studies (28, 31, 35). Concentrations of lysergic acid amides were estimated by comparison of areas under HPLC peaks to a standard curve prepared from dilutions of ergonovine, which contains the same fluorophore as the other lysergic acid amides. Because of this comparison to ergonovine, the concentrations of LAH and ergine should be considered “relative to ergonovine” rather than absolute.

Mutagenesis of easD.

Aspergillus leporis contains two copies of the LAH-associated ergot alkaloid synthesis gene cluster, but only one of those clusters has a functional copy of easD (31). The functional copy of easD was mutated by introducing a transiently expressed Cas9 complex containing a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) synthesized from the template 5′-TTCTAATACGACTCACTATAGAGCAGCCACCTGCCGTCTGCGTTTTAGAGCTAGA-3′ (the target sequence containing a G at its 5′ end is underlined) with the EnGen sgRNA synthesis kit (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The resulting sgRNA was purified with the Monarch RNA cleanup kit (New England BioLabs) and complexed with EnGen Spy Cas9 NLS (New England BioLabs). The Cas9-sgRNA complex was cotransformed into protoplasts of A. leporis along with a phleomycin resistance gene from pBCphleo (53) (Fungal Genetics Stock Center, Manhattan, KS). Protoplasts were prepared by application of the procedure described by Davis et al. (36) for M. brunneum and involving the cell wall degrading enzyme mixtures VinoTaste Pro (Crush2Cellar, Newberg, OR) and Driselase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Transformed colonies were regenerated in TM102 agar (36) containing phleomycin at 400 μg/mL. Colonies were tested for possible mutation through PCR analysis primed from oligonucleotides 5′-CTACTCCAACGACTAGGACCTC-3′ and 5′-GTTGCGATAATGCTATGCATCC-3′ using 35 cycles of amplification as follows: 15 s at 98°C, 15 s at 64°C, and 90 s at 72°C with Phusion Green master mix (Thermo Scientific). PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis, and products differing in size from that obtained from wild-type A. leporis were purified with the Zymo Research (Irvine, CA) DNA Clean and Concentrator kit and sequenced by Sanger technology at Eurofins Genomics (Louisville, KY). Ergot alkaloid profiles of easD knockout mutants compared to wild-type A. leporis were analyzed by HPLC with fluorescence detection as described above.

Statistical analyses.

Larval survival was plotted on Kaplan-Meier curves and differences among curves from experimental treatments and controls were assessed with log-rank tests. The alpha level for each experiment was adjusted by Bonferroni correction to account for multiple comparisons. Comparisons of ergot alkaloid concentrations among different species were made by Steel-Dwass multiple-comparison tests (with alpha set at 0.05). This nonparametric test was chosen because of unequal variances among samples as determined with Brown-Forsythe tests (P < 0.05). All statistical analyses were conducted using JMP software (SAS, Cary, NC).

Data availability.

Data documenting the survival of inoculated insects, the accumulation of ergot alkaloids in cultures and in infected insects, and the diameters of colonies of Aspergillus species are available in a file accessible via datadryad.org (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.r7sqv9shm).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was funded by NIH grant 2R15-GM114774-3, with additional salary support for D.G.P. from USDA Hatch project NC1183. A.M.J. is a Beckman Scholar supported by the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation.

This paper is published with the approval of the West Virginia Agriculture and Forestry Experiment Station as article number 3455.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Daniel G. Panaccione, Email: danpan@wvu.edu.

Irina S. Druzhinina, Royal Botanic Gardens

REFERENCES

- 1.Casadevall A, Pirofski L. 2007. Accidental virulence, cryptic pathogenesis, Martians, lost hosts, and the pathogenicity of environmental microbes. Eukaryot Cell 6:2169–2174. doi: 10.1128/EC.00308-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siscar-Lewin S, Hube B, Brunke S. 2022. Emergence and evolution of virulence in human pathogenic fungi. Trends Microbiol 30:693–704. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rokas A. 2022. Evolution of the human pathogenic lifestyle in fungi. Nat Microbiol 7:607–619. doi: 10.1038/s41564-022-01112-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinekamp T, Thywissen A, Macheleidt J, Keller S, Valiante V, Brakhage AA. 2013. Aspergillus fumigatus melanins: interference with the host endocytosis pathway and impact on virulence. Front Microbiol 3:440. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillmann F, Novohradská S, Mattern DJ, Forberger T, Heinekamp T, Westermann M, Winckler T, Brakhage AA. 2015. Virulence determinants of the human pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus protect against soil amoeba predation. Environ Microbiol 17:2858–2869. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akoumianaki T, Kyrmizi I, Valsecchi I, Gresnigt MS, Samonis G, Drakos E, Boumpas D, Muszkieta L, Prevost M-C, Kontoyiannis DP, Chavakis T, Netea MG, van de Veerdonk FL, Brakhage AA, El-Benna J, Beauvais A, Latge J-P, Chamilos G. 2016. Aspergillus cell wall melanin blocks LC3-associated phagocytosis to promote pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 19:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadevall A, Fu MS, Guimaraes AJ, Albuquerque P. 2019. The “amoeboid predator-fungal animal virulence” hypothesis. J Fungi 5:10. doi: 10.3390/jof5010010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavanagh K, Reeves EP. 2004. Exploiting the potential of insects for in vivo pathogenicity testing of microbial pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 28:101–112. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mylonakis E, Moreno R, El Khoury JB, Idnurm A, Heitman J, Calderwood SB, Ausubel FM, Diener A. 2005. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Cryptococcus neoformans pathogenesis. Infect Immun 73:3842–3850. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.7.3842-3850.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs BB, O’Brien E, Khoury JBE, Mylonakis E. 2010. Methods for using Galleria mellonella as a model host to study fungal pathogenesis. Virulence 1:475–482. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.6.12985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borman AM. 2018. Of mice and men and larvae: Galleria mellonella to model the early host-pathogen interactions after fungal infection. Virulence 9:9–12. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2017.1382799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pereira MF, Rossi CC, da Silva GC, Rosa JN, Bazzolli DM. 2020. Galleria mellonella as an infection model: an in-depth look at why it works and practical considerations for successful application. Pathog Dis 78:ftaa056. doi: 10.1093/femspd/ftaa056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.St Leger RJ, Screen SE, Shams-Pirzadeh B. 2000. Lack of host specialization in Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:320–324. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.1.320-324.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scully LR, Bidochka MJ. 2005. Serial passage of the opportunistic pathogen Aspergillus flavus through an insect host yields decreased saprobic capacity. Can J Microbiol 51:185–189. doi: 10.1139/w04-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fallon JP, Reeves EP, Kavanagh K. 2011. The Aspergillus fumigatus toxin fumagillin suppresses the immune response of Galleria mellonella larvae by inhibiting the action of hemocytes. Microbiology (Reading) 157:1481–1488. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.043786-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brauer VS, Pessoni AM, Bitencourt TA, de Paula RG, de Oliveira Rocha L, Goldman GH, Almeida F. 2020. Extracellular vesicles from Aspergillus flavus induce M1 polarization in vitro. mSphere 5:e00190-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00190-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knowles SL, Mead ME, Silva LP, Raja HA, Steenwyk JL, Goldman GH, Oberlies NH, Rokas A. 2020. Gliotoxin, a known virulence factor in the major human pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus, is also biosynthesized by its nonpathogenic relative Aspergillus fischeri. mBio 11:e03361-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03361-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stączek S, Zdybicka-Barabas A, Pleszczyńska M, Wiater A, Cytryńska M. 2020. Aspergillus niger α-1,3-glucan acts as a virulence factor by inhibiting the insect phenoloxidase system. J Invertebr Pathol 171:107341. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2020.107341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durieux MF, Melloul É, Jemel S, Roisin L, Dardé ML, Guillot J, Dannaoui É, Botterel F. 2021. Galleria mellonella as a screening tool to study virulence factors of Aspergillus fumigatus. Virulence 12:818–834. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1893945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Panaccione DG, Arnold SL. 2017. Ergot alkaloids contribute to virulence in an insect model of invasive aspergillosis. Sci Rep 7:8930. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09107-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foley K, Fazio G, Jensen AB, Hughes WHO. 2014. The distribution of Aspergillus spp. opportunistic parasites in hives and their pathogenicity to honey bees. Vet Microbiol 169:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UN Food and Agriculture Organization. 2017. Chalkbrood and stonebrood. UN Food and Agriculture Organization, New York, NY. https://www.fao.org/3/ca4052en/ca4052en.pdf. Accessed 10 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 23.St Leger RJ, Wang JB. 2020. Metarhizium: jack of all trades, master of many. Open Biol 10:200307. doi: 10.1098/rsob.200307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone LB, Bidochka MJ. 2020. The multifunctional lifestyles of Metarhizium: evolution and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 104:9935–9945. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10968-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheng H, McNamara PJ, Leger RJ. 2022. Metarhizium: an opportunistic middleman for multitrophic lifestyles. Curr Opin Microbiol 69:102176. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2022.102176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang B, Kang Q, Lu Y, Bai L, Wang C. 2012. Unveiling the biosynthetic puzzle of destruxins in Metarhizium species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:1287–1292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115983109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tong X, Wang Y, Yang P, Wang C, Kang L. 2020. Tryptamine accumulation caused by deletion of MrMao-1 in Metarhizium genome significantly enhances insecticidal virulence. PLoS Genet 16:e1008675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steen CR, Sampson JK, Panaccione DG. 2021. A Baeyer-Villiger monooxygenase gene involved in the synthesis of lysergic acid amides affects the interaction of the fungus Metarhizium brunneum with insects. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e00748-21. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00748-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panaccione DG. 2023. Derivation of the multiply-branched ergot alkaloid pathway of fungi. Microb Biotechnol 16:742–756. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.14214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spatafora JW, Sung G-H, Sung J-M, Hywel-Jones NL, White JF. 2007. Phylogenetic evidence for an animal pathogen origin of ergot and the grass endophytes. Mol Ecol 16:1701–1711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones AM, Steen CR, Panaccione DG. 2021. Independent evolution of a lysergic acid amide in Aspergillus species. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e01801-21. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01801-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.States JS, Christensen M. 1966. Aspergillus leporis, a new species related to A. flavus. Mycologia 58:738–742. doi: 10.2307/3756848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitt JI, Lange L, Lacey AE, Vuong D, Midgley DJ, Greenfield P, Bradbury MI, Lacey E, Busk PK, Pilgaard B, Chooi YH, Piggott AM. 2017. Aspergillus hancockii sp. nov., a biosynthetically talented fungus endemic to southeastern Australian soils. PLoS One 12:e0170254. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steiman R, Guiraud P, Sage L, Seigle-Murandi F. 1995. New strains from Israel in the Aspergillus niger group. System Appl Microbiol 17:620–624. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80084-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leadmon CE, Sampson JK, Maust MD, Macias AM, Rehner SA, Kasson MT, Panaccione DG. 2020. Several Metarhizium species produce ergot alkaloids in a condition-specific manner. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e00373-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00373-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis KA, Sampson JK, Panaccione DG. 2020. Genetic reprogramming of the ergot alkaloid pathway of Metarhizium brunneum. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e01251-20. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01251-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Britton KN, Steen CR, Davis KA, Sampson JK, Panaccione DG. 2022. Contribution of a novel gene to lysergic acid amide synthesis in Metarhizium brunneum. BMC Res Notes 15:183. doi: 10.1186/s13104-022-06068-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wicklow DT. 1985. Aspergillus leporis sclerotia form on rabbit dung. Mycologia 77:531–534. doi: 10.2307/3793351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.TePaske MR, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT, Dowd PF. 1991. Leporin A: an antiinsectan N-alkoxypyridone from the sclerotia of Aspergillus leporis. Tetrahedron Lett 32:5687–5690. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)93530-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.States JS, Christensen M. 2001. Fungi associated with biological crusts in desert grasslands of Utah and Wyoming. Mycologia 93:432–439. doi: 10.2307/3761728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta A, Gopal M. 2002. Aflatoxin production by Aspergillus flavus isolates pathogenic to coconut insect pests. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 18:325–331. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samson RA, Houbraken JA, Kuijpers AF, Frank JM, Frisvad JC. 2004. New ochratoxin A- or sclerotium-producing species in Aspergillus section Nigri. Stud Mycol 50:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hussein N, Abdel-Hafez SI, Abdel-Sater MA, Ismail MA, Eshraq AL. 2017. Aspergillus homomorphus, a first global record from millet grains. CREAM 7:82–89. doi: 10.5943/cream/7/2/4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallwey C, Matuschek M, Li SM. 2010. Ergot alkaloid biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus: conversion of chanoclavine-I to chanoclavine-I aldehyde catalyzed by a short-chain alcohol dehydrogenase FgaDH. Arch Microbiol 192:127–134. doi: 10.1007/s00203-009-0536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Potter DA, Stokes JT, Redmond CT, Schardl CL, Panaccione DG. 2008. Contribution of ergot alkaloids to suppression of a grass-feeding caterpillar assessed with gene-knockout endophytes in perennial ryegrass. Entomol Experimental Applicat 126:138–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.2007.00650.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hudson D, Mace W, Popay A, Jensen J, McKenzie C, Cameron C, Johnson R. 2021. Genetic manipulation of the ergot alkaloid pathway in Epichloë festucae var. lolii and its effect on black beetle feeding deterrence. Toxins 13:76. doi: 10.3390/toxins13020076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frisvad JC, Hubka V, Ezekiel CN, Hong S-B, Nováková A, Chen AJ, Arzanlou M, Larsen TO, Sklenář F, Mahakarnchanakul W, Samson RA, Houbraken J. 2019. Taxonomy of Aspergillus section Flavi and their production of aflatoxins, ochratoxins and other mycotoxins. Stud Mycol 93:1–63. doi: 10.1016/j.simyco.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.TePaske MR, Gloer JB, Wicklow DT, Dowd PF. 1992. Aflavarin and β-aflatrem: new anti-insectan metabolites from the sclerotia of Aspergillus flavus. J Nat Prod 55:1080–1086. doi: 10.1021/np50086a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaur N, Cooper WR, Duringer JM, Badillo-Vargas IE, Esparza-Diaz G, Rashed A, Horton DR. 2018. Survival and development of potato psyllid (Hemiptera: Triozidae) on Convolvulaceae: effects of a plant-fungus symbiosis (Periglandula). PLoS One 13:e0201506. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen XD, Kaur N, Horton DR, Cooper WR, Qureshi JA, Stelinski LL. 2021. Crude extracts and alkaloids derived from Ipomoea-Periglandula symbiotic association cause mortality of Asian citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Insects 12:929. doi: 10.3390/insects12100929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panaccione DG, Ryan KL, Schardl CL, Florea S. 2012. Analysis and modification of ergot alkaloid profiles in fungi. Methods Enzymol 515:267–290. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394290-6.00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bragg PE, Maust MD, Panaccione DG. 2017. Ergot alkaloid biosynthesis in the maize (Zea mays) ergot fungus Claviceps gigantea. J Agric Food Chem 65:10703–10710. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b04272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silar P. 1995. Two new easy to use vectors for transformations. Fungal Genet Rep 42:73. doi: 10.4148/1941-4765.1353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kleinerova E, Kybal J. 1973. Ergot alkaloids IV. Contribution to the biosynthesis of lysergic acid amides. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 18:390–392. doi: 10.1007/BF02875934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Flieger M, Sedmera P, Vokoun J, Ricicova A, Rehacek Z. 1982. Separation of four isomers of lysergic acid α-hydroxyethylamide by liquid chromatography and their spectroscopic identification. J Chromatogr 236:453–459. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S4. Download aem.00415-23-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.4 MB (441KB, pdf)

Video S1. Download aem.00415-23-s0002.mp4, MP4 file, 9.3 MB (9.3MB, mp4)

Data Availability Statement

Data documenting the survival of inoculated insects, the accumulation of ergot alkaloids in cultures and in infected insects, and the diameters of colonies of Aspergillus species are available in a file accessible via datadryad.org (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.r7sqv9shm).