Abstract

Background

In CheckMate 9ER, nivolumab plus cabozantinib showed superior progression-free survival, overall survival (OS), and objective response over sunitinib in patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC; median follow-up, 18·1 months). We report extended follow-up of OS and updated efficacy and safety.

Methods

In this phase 3, randomised, open-label trial, adults (≥18 years) with previously untreated advanced/metastatic clear cell RCC and Karnofsky performance status ≥70% from 125 hospitals and cancer centres in 18 countries were randomised 1:1 to nivolumab (240 mg intravenously) every 2 weeks plus cabozantinib (40 mg orally) once daily or sunitinib (50 mg orally) once daily (4 weeks per 6-week cycle). Randomisation, stratified by IMDC risk status, tumour PD-L1 expression, and geographic region, was done by permuted block via an interactive response system. The primary endpoint was progression-free survival per blinded independent central review. OS was a secondary endpoint (reported here as pre-planned final analysis per protocol). Efficacy was assessed in all randomised patients; safety was assessed in all treated patients. This ongoing study, closed to recruitment, is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03141177.

Findings

Between September 11, 2017, and May 14, 2019, 651 of 1003 patients screened for eligibility were randomised to nivolumab plus cabozantinib or sunitinib (n=323 vs n=328). With extended follow-up (median, 32·9 months [IQR 30·4–35·9]), superior OS (HR 0·70 [95% CI 0·55–0·90]) and progression-free survival (median 16·6 months [95% CI 12·8–19·8] with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus 8·3 months [95% CI 7·0–9·7] with sunitinib; HR 0·56 [95% CI 0·46–0·68]) were observed with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib. Grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse events (AEs) occurred in 208 (65%) of 320 patients with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus 172 (54%) of 320 with sunitinib. The most common grade 3–4 treatment-related AEs were hypertension (40 [13%] of 320 patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group vs 39 [12%] of 320 in the sunitinib group), palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia (25 [8%] vs 26 [8%]), and diarrhoea (22 [7%] vs 15 [5%]). Grade 3–4 treatment-related serious AEs occurred in 70 (22%) of 320 patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group and 31 (10%) of 320 in the cabozantinib group. One additional treatment-related death occurred with sunitinib (sudden death).

Interpretation

With extended follow-up and pre-planned final OS analysis per protocol, nivolumab plus cabozantinib demonstrated improved efficacy versus sunitinib, further supporting the combination in first-line treatment of advanced RCC.

Keywords: cabozantinib, clinical subgroups, nivolumab, renal cell carcinoma, sunitinib, target lesion organ site, treatment-naïve

INTRODUCTION

In the phase 3 CheckMate 9ER trial of first-line nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma, nivolumab plus cabozantinib demonstrated superiority over sunitinib after a median follow-up for overall survival of 18·1 months (minimum, 10·6 months; primary database lock, March 30, 2020).1 In the primary analysis, data were reported based on the final analysis of progression-free survival (primary endpoint), the first interim analysis of overall survival, and the final analysis of objective response. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib significantly improved progression-free survival per blinded independent central review (BICR; hazard ratio [HR] 0·51; p<0·001), overall survival (HR 0·60; p=0·0010), and objective response per BICR (55·7% vs 27·1%; p<0·001) versus sunitinib in intention-to-treat patients.1 On the basis of the CheckMate 9ER trial, nivolumab plus cabozantinib is recommended as a new standard of care for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma.2,3

Here, we report updated results including the pre-planned final analysis of overall survival per study protocol, together with updated progression-free survival, objective response, and safety outcomes with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib from the phase 3 CheckMate 9ER trial with an extended median follow-up for overall survival of 32·9 months (minimum, 25·4 months; database lock, June 24, 2021), which is almost double that of the primary analysis. Additionally, we report an assessment of efficacy in pre-specified and post-hoc patient subgroups of clinical interest at baseline (sarcomatoid features, previous nephrectomy status, and organ sites of metastasis), and a post-hoc exploratory assessment of maximal reduction from baseline of target lesions by organ site (kidney, liver, lung, lymph node, and bone).

METHODS

Study design and participants

CheckMate 9ER is a phase 3, randomised, parallel-arm, open-label trial of nivolumab combined with cabozantinib versus sunitinib monotherapy in patients with previously untreated advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma, recruited from 125 hospitals and cancer centres in 18 countries (appendix p 2). The CheckMate 9ER trial design and methods have been reported previously.1 Briefly, adult patients (age 18 years or older) were included who had histologically confirmed advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma with a clear cell component (including sarcomatoid features), no previous systemic therapy, a Karnofsky performance status of ≥70, measurable disease per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 assessed by the investigator, any International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) prognostic risk category, and available tumour tissue for programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) testing. Patients were excluded if they had active central nervous system metastases (patients with treated, stable metastases for ≥1 month were eligible), active or suspected autoimmune disease, or a condition requiring treatment with corticosteroids (>10 mg daily prednisone or equivalent) or other immunosuppressive medications within 14 days before randomisation. Patients must have had adequate organ function based on laboratory testing requirements.

CheckMate 9ER was approved by an institutional review board or ethics committee before initiation at each site and was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, as defined by the International Conference for Harmonisation and European Union Directive 2001/20/EC and the United States Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 50 (21CFR50). All enrolled patients provided written informed consent. During the study, protocol amendments on Dec 18, 2017, and May 3, 2019, were made that affected the design of the study and recruitment (these included the termination of enrolment into a nivolumab plus ipilimumab plus cabozantinib triplet arm, the inclusion of favourable-risk patients in the primary data analysis, adjustment to interim analyses and the overall alpha of endpoints, and an increase in the number of randomised patients). The study protocol with full details of revisions is available in the appendix.

Randomisation and masking

Patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to nivolumab plus cabozantinib or sunitinib through an interactive response technology system. The allocation sequence was generated by the Bristol Myers Squibb interactive response technology team. This allocation sequence was transferred to a third-party vendor for enrolment of patients and assignment to trial groups in collaboration with the investigators at the study sites. Patients were stratified according to IMDC prognostic risk score (0 [favourable] vs 1 or 2 [intermediate] vs 3 to 6 [poor]), geographic region (United States, Canada, and Europe vs the rest of the world), and tumour PD-L1 expression (≥1% vs <1% or indeterminate). Randomisation was carried out via permuted blocks within each stratum. Patients and investigators were not masked to study treatment in this open-label trial.

Procedures

Patients received either nivolumab (240 mg) intravenously every 2 weeks and cabozantinib (40 mg) orally once daily, or sunitinib (50 mg) orally once daily for 4 weeks and 2 weeks off in each 6-week cycle. Patients received up to a maximum of 2 years of nivolumab treatment or until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent, whichever occurred first. Crossover between treatment groups was not permitted. Dose delays for the management of adverse events were allowed for nivolumab, cabozantinib, and sunitinib; dose reductions were allowed only for cabozantinib and sunitinib. Assessments for discontinuation were made separately for nivolumab and cabozantinib; if discontinuation criteria were met for one drug but not the other, treatment may have been continued with the drug believed to be unrelated to the reported toxicity. Tumour assessments were done with CT or MRI of the chest, abdomen, pelvis, brain (baseline only), and all known sites of disease at baseline (within 28 days before randomisation), at 12 weeks (±7 days) after randomisation, then every 6 weeks (±7 days) until week 60, then every 12 weeks (±14 days) until disease progression per RECIST version 1.1 (as assessed by the investigator and confirmed by BICR). Adverse events were reported at each study visit for a minimum of 100 days after last dose per the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. PD-L1 expression status was evaluated using the validated PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx immunohistochemical assay (Dako, an Agilent Technologies, Inc. company, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

Immune-mediated adverse events were also monitored, as was the use of glucocorticoids (≥40 mg prednisone daily or equivalent) to manage these events. Immune-mediated adverse events were defined as events occurring within 100 days of the last dose, regardless of causality, treated with immune-modulating medication with the exception of endocrine events (adrenal insufficiency, hypophysitis, hypothyroidism/thyroiditis, hyperthyroidism, and diabetes mellitus), which are included regardless of treatment, and no clear alternate cause based on investigator assessment or with an immune-mediated component).

Outcomes

Overall survival was a secondary endpoint of CheckMate 9ER. The primary endpoint was RECIST version 1.1–defined progression-free survival per BICR. Other secondary endpoints were objective response per BICR (including time to and duration of response), safety and tolerability (including treatment-related adverse events and adverse events leading to discontinuation). Exploratory endpoints included health-related quality of life, predictive biomarkers, pharmacokinetics of nivolumab and cabozantinib and exposure response relationships, immunogenicity of nivolumab, and progression-free survival after subsequent line of treatment (progression-free survival 2). Health-related quality of life and progression-free survival 2 outcomes have been reported previously; further reporting of exploratory endpoints here is beyond the scope of this manuscript.1,4,5

Overall survival was defined as the time between the date of randomisation and the date of death due to any cause. Progression-free survival was defined as the time between the date of randomisation and the first date of documented progression, or death due to any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients who died without a reported progression (and died without starting subsequent anticancer therapy) were considered to have progressed on the date of death. Patients who received subsequent anticancer therapy were censored at the date of last evaluable tumour assessment conducted on or before the date of initiation of the subsequent anticancer therapy. Objective response was defined as the proportion of randomised patients who achieve a best response of complete response or partial response per RECIST version 1.1.

Statistical analysis

Details of the statistical analyses have been reported previously.1 Overall, 638 patients were to be randomised. This study used an overall α of 0·05 (two-sided) using a hierarchical testing procedure for progression-free survival per BICR, overall survival, and objective response per BICR. Progression-free survival per BICR (primary endpoint; single final analysis) was evaluated at an α of 0·05 with at least 95% power. As the between-group difference in progression-free survival per BICR was statistically significant, the evaluation of overall survival (secondary endpoint; planned at an overall α of 0·05 with 80% power in two interim analyses and a final analysis with 254 events [α of 0·011, 0·025, 0·041, all two-sided, respectively, using the O’Brien and Fleming α spending function6]) was planned. As the first interim analysis of overall survival crossed the pre-specified boundary for statistical significance and showed between-group difference (statistical significance level p<0·0111), further formal analysis of overall survival was not required. Objective response (secondary endpoint) was then tested hierarchically at an overall α of 0·05. Here, after hierarchical testing was complete, we report the pre-planned final analysis of overall survival per study protocol that was set to occur after 254 events.

Between-group comparisons of overall survival and progression-free survival were done using a stratified log-rank test with HRs calculated using a stratified Cox proportional-hazards model for the intention-to-treat population. The same stratification factors used in randomisation were used for all stratified analyses. For subgroups, unstratified models were used. The assumption of proportional hazards in the Cox regression model was examined at the primary analysis by adding into the model a time-dependent variable defined by treatment by time interaction. The two-sided Wald chi-square p value was 0·1408 at the primary analysis, confirming the proportional-hazards assumption was met before this long-term follow-up. Kaplan–Meier methodology was used to estimate overall survival, progression-free survival, and duration of response. The proportion of patients achieving an objective response per BICR and exact two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Clopper–Pearson method.7 P values were descriptive and a significance threshold of less than 0·05 was used.

Analysis of efficacy endpoints was done using data from the intention-to-treat population (ie, all randomly assigned patients). Additional analyses of efficacy endpoints were conducted in patient subgroups at baseline, based on disease and demographic characteristics, either as pre-specified in the protocol (age, geographic region, race, IMDC prognostic score, ethnicity, previous nephrectomy, previous radiotherapy, tumour PD-L1 expression, sarcomatoid features, disease stage at initial diagnosis, bone metastasis) or post-hoc (liver metastasis, lung metastasis) and evaluated per RECIST version 1.1 by BICR. Exposure, safety, and tolerability were analysed using data from all treated patients (patients who received at least one dose of any study drug).

A post-hoc analysis of depth of response in target lesions by organ site was done, whereby maximum reduction from baseline in the sum of diameters of target lesions was evaluated per RECIST version 1.1 by BICR (kidney, liver, lung, and lymph node), or by investigator (bone) in patients with a target lesion at baseline and at least one on-treatment tumour assessment and analysed descriptively. The prevalence of grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse events over time by most common system organ classes of clinical relevance was evaluated post-hoc for all treated patients in each treatment group and summarised using vector density plots.

A data monitoring committee provided oversight of efficacy, safety, and study conduct. All statistical analyses were done with SAS, version 9.2. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT03141177.

Role of funding source

The funders contributed to the study design, data analysis, and data interpretation in collaboration with the authors. The funders did not have a role in data collection. Financial support for editorial and writing assistance was provided by the funders. All authors had complete access to the data in the study.

RESULTS

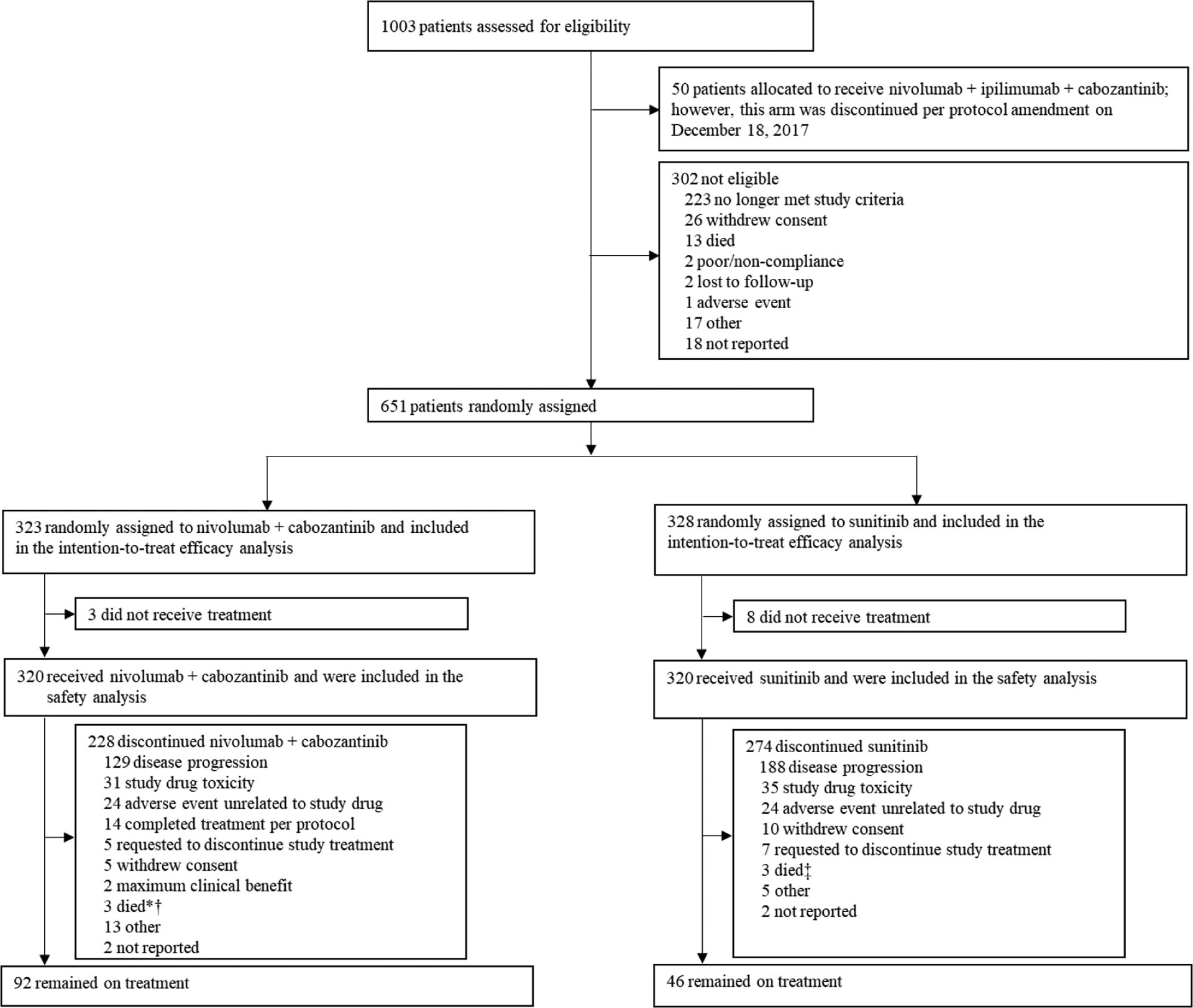

Between September 11, 2017, and May 14, 2019, 651 of 1003 patients screened for eligibility in CheckMate 9ER were randomly assigned (intention-to-treat population) to receive either nivolumab plus cabozantinib (N=323) or sunitinib (N=328; figure 1). A total of 320 patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group and 320 patients in the sunitinib group received the assigned treatment and were included in the safety analysis (all treated patients). Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline for the intention-to-treat population have been reported previously.1 Overall, baseline characteristics were balanced between treatment groups and representative of patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma (table 1).

Figure 1: Trial profile.

*In the primary database lock (March 30, 2020), four deaths were reported as the reason for discontinuation of nivolumab plus cabozantinib. In the current database lock (June 24, 2021), the reasons for discontinuation of nivolumab plus cabozantinib for three patients were reclassified from death to disease progression, adverse event unrelated to study drug, and study drug toxicity, and an additional two patients discontinued nivolumab plus cabozantinib due to death. †Reasons for death were sudden death (n=2), and cardiac arrest (n=1). ‡Reasons for death were sudden death (n=2), and unknown (n=1).

Table 1:

Demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline in the intention-to-treat population

| Characteristic* | Nivolumab plus cabozantinib (N=323) | Sunitinib (N=328) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 62 (29–90) | 61 (28–86) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 249 (77) | 232 (71) |

| Female | 74 (23) | 96 (29) |

| Race | ||

| White | 267 (83) | 266 (81) |

| Black or African American | 1 (<1) | 4 (1) |

| Asian | 26 (8) | 25 (8) |

| Other/not reported† | 29 (9) | 33 (10) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic or Latino | 38 (12) | 39 (12) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 149 (46) | 151 (46) |

| Not reported | 136 (42) | 138 (42) |

| Karnofsky performance status‡ | ||

| <90 | 66 (20) | 85 (26) |

| 90–100 | 257 (80) | 241 (73) |

| Not reported | 0 | 2 (<1) |

| IMDC prognostic score (IRT) | ||

| Favourable (0) | 74 (23) | 72 (22) |

| Intermediate (1–2) | 188 (58) | 188 (57) |

| Poor (3–6) | 61 (19) | 68 (21) |

| Region (IRT) | ||

| US/Europe | 158 (49) | 161 (49) |

| Rest of the world | 165 (51) | 167 (51) |

| Tumour PD-L1 expression | ||

| ≥1% | 83 (26) | 83 (25) |

| <1% or indeterminate | 240 (74) | 245 (75) |

| Not reported | 0 | 0 |

| No. of organ sites with target/non-target lesions | ||

| 1 | 63 (20) | 69 (21) |

| ≥2 | 259 (80) | 256 (78) |

Data are n (%) unless otherwise reported.

The ITT population includes all patients who underwent randomisation. The IMDC prognostic risk score, PD-L1 status, and geographic region (stratification factors) were recorded at screening by means of IRT in ITT patients, whereas PD-L1 status was reported per case report form in subgroups.

Other race included American Indian and Alaska Native, and answers such as Hispanic, Latino, unknown, not specified.

Karnofsky performance status scores range from 0–100, with lower scores indicating greater disability.

Data are for tumour sites defined at baseline by the investigators according to RECIST version 1.1.

IMDC=International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. IRT=interactive response technology. ITT=intention–to-treat. PD-L1=programmed death ligand 1. RECIST=Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

In part published in Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 829–41.

The data cutoff for this analysis with extended follow-up was June 24, 2021. At a median follow-up for overall survival of 32·9 months (interquartile range [IQR] 30·4–35·9]) (minimum, 25·4 months), 228 (71%) of 320 patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group and 274 (86%) of 320 patients in the sunitinib group had discontinued treatment (figure 1). The most common reason for discontinuation was disease progression in both treatment groups. At data cutoff, 92 (29%) of 320 treated patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group and 46 (14%) of 320 treated patients in the sunitinib group remained on treatment. In patients who discontinued, 70 (31%) of 228 patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group and 122 (45%) of 274 patients in the sunitinib group received subsequent systemic therapy; most commonly a VEGF(R)-targeted agent (61 [27%]) was used in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group and a nivolumab-based or other PD-(L)1 inhibitor-based therapy (92 [34%]) was used in the sunitinib group (appendix p 9).

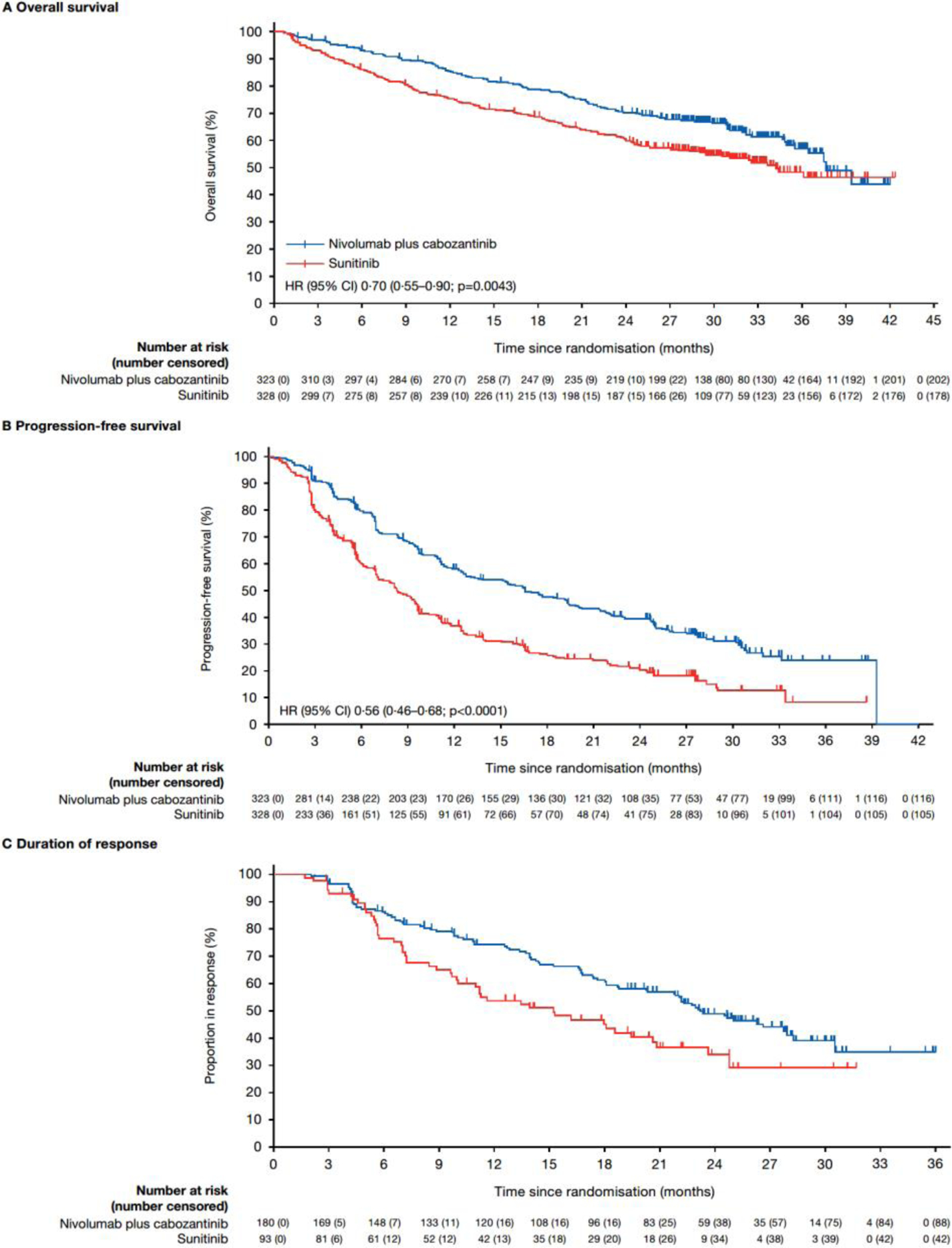

With extended median follow-up for overall survival of 32·9 months, a total of 271 events occurred, and nivolumab plus cabozantinib demonstrated a 30% reduction in the risk of death versus sunitinib (HR 0·70 [95% CI 0·55–0·90]). Median overall survival was 37·7 months (95% CI 35·5–not estimable) with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus 34·3 months (95% CI 29·0–not estimable) with sunitinib; 24-month overall survival was 10 percentage points higher with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib (70% [95% CI, 65–75] vs 60% [95% CI, 55–66]), respectively; figure 2A). Overall survival generally favoured nivolumab plus cabozantinib over sunitinib across the stratification categories of geographic region, tumour PD-L1 expression subgroups, and IMDC prognostic risk category (appendix p 19, p 23–24).

Figure 2:

Overall survival (A), progression-free survival (B), and duration of response (C) in the intention-to-treat population

Progression-free survival benefit was observed with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib with extended follow-up (HR 0·56 [95% CI 0·46–0·68]). Overall, 207 (64%) of 323 patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group and 223 (68%) of 328 patients in the sunitinib group had a progression event. Median progression-free survival was 16·6 months (95% CI 12·8–19·8) with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus 8·3 months (95% CI 7·0–9·7) with sunitinib; 24-month progression-free survival was 39·5% (95% CI 33·9–45·1) versus 20·9% (95% CI 16·0–26·3), respectively (figure 2B). Progression-free survival benefit generally favoured nivolumab plus cabozantinib over sunitinib regardless of the stratification categories of geographic region, tumour PD-L1 expression, and IMDC prognostic risk category (appendix p 20, p 24–25).

Confirmed objective response was higher in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group than in the sunitinib group (180 [56%] of 323 vs 93 [28%] of 328). A higher proportion of patients achieved a complete response with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib (40 [12%] of 323 vs 17 [5%] of 328; table 2). Median (IQR) time to response was 2·8 months (2·8–4·2) versus 4·2 months (2·8–7·1), respectively. Median (95% CI) duration of response was 23·1 months (20·2–27·9) with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus 15·1 months (9·9–20·5) with sunitinib (figure 2C), and 88 (49%) of 180 versus 42 (45%) of 93 responses were ongoing at database lock, respectively. Median (IQR) time to complete response was 11·5 months (5·6–19·2) with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus 7·1 months (4·2–19·2) with sunitinib; 26 (65%) of 40 versus 10 (59%) of 17 complete responses were ongoing at database lock, respectively. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib generally provided greater objective response benefit versus sunitinib across the stratification categories of geographic region, tumour PD-L1 expression, and IMDC prognostic risk category (appendix p 21, p 11).

Table 2:

Summary of confirmed objective response per blinded independent central review in the intention-to-treat population

| Variable* | Nivolumab plus cabozantinib (N=323) | Sunitinib (N=328) |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmed objective response, % | 56 | 28 |

| (95% CI) | (50–61) | (24–34) |

| Confirmed best overall response, n (%) | ||

| Complete response | 40 (12) | 17 (5) |

| Partial response | 140 (43) | 76 (23) |

| Stable disease | 105 (33) | 134 (41) |

| Progressive disease | 20 (6) | 45 (14) |

| Unable to determine | 18 (6) | 55 (17) |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Median time to response (IQR), months | 2·8 (2·8–4·2) | 4·2 (2·8–7·1) |

| Median duration of response (95% CI), months | 23·1 (20·2–27·9) | 15·1 (9·9–20·5) |

Response was assessed according to RECIST v1.1, per blinded independent central review.

IQR=interquartile range. RECIST=Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

Pre-specified and post-hoc analyses were performed for subgroups of clinical interest at baseline, including patients with sarcomatoid features (sarcomatoid positive, n=75; sarcomatoid negative/not reported, n=576), prior nephrectomy (with prior nephrectomy, n=455; without prior nephrectomy, n=196), liver metastases (n=127), bone metastases (n=152), and lung metastases (n=492). Baseline characteristics for these subgroups are shown in the appendix p 6. Superior overall survival was observed with nivolumab plus cabozantinib over sunitinib among patients with sarcomatoid features, with prior nephrectomy, with liver metastasis, with bone metastasis, or with lung metastasis at baseline (appendix p 19, p 26–27, p 30). Progression-free survival and objective response benefits were also generally observed with nivolumab plus cabozantinib over sunitinib among patient subgroups of clinical interest at baseline (appendix p 20–21, p 28–29, p 30, p 12).

In the post-hoc exploratory analysis of depth of response in target lesions by organ site, a higher proportion of patients experienced target lesion shrinkage with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib, regardless of target lesion organ site (appendix p 31). A higher proportion of patients experienced a ≥30% reduction from baseline with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib in kidney (33 [45%] of 73 vs 22 [30%] of 74), liver (21 [48%] of 44 vs 13 [33%] of 39), lung (120 [76%] of 158 vs 85 [46%] of 183), lymph node (90 [74%] of 121 vs 54 [48%] of 113) target lesions assessed per BICR, and bone metastases with measurable target lesions assessed per investigator (15 [56%] of 27 vs 4 [20%] of 20) (appendix p 31). Overall, three patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group and four patients in the sunitinib group underwent postbaseline delayed nephrectomy.

Treatment exposure is summarised in appendix p 14. Median (IQR) duration of treatment was 21·8 months (8·8–29·5) in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group (overall), and 8·9 months (2·9–20·7) in the sunitinib group. Treated patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group received a median of 35·0 nivolumab doses (IQR 14·0–50·0) and a median average daily dose of cabozantinib of 27·8 mg/day (IQR 20·7–38·6). The median average daily dose of sunitinib was 27·5 mg/day (IQR 22·5–32·1) over the 6-week cycle. Dose delays occurred in 238 (74%) and 270 (84%) of 320 patients treated with nivolumab and cabozantinib, respectively, and in 239 (75%) of 320 patients treated with sunitinib. The most common reason for dose delay in each case was for the management of adverse events. Dose reductions occurred in 196 (61%) patients treated with cabozantinib and in 172 (54%) patients treated with sunitinib. The most common reason for dose reduction for cabozantinib or sunitinib was for the management of adverse events. The median time to first dose level reduction due to adverse events was 108·5 days (IQR 64·5–206·0) with cabozantinib and 61·0 days (IQR 42·0–168·0) with sunitinib.

Consistent with the primary analysis,1 all-cause adverse events of any grade (319 [100%] of 320 vs 317 [99%] of 320; appendix p 16) and treatment-related adverse events of any grade (311 [97%] of 320 vs 298 [93%] of 320) occurred in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib and sunitinib groups at similar rates with extended follow-up. Treatment-related adverse events of any grade are shown in table 3 and appendix p 33. Treatment-related adverse events of any grade led to discontinuation of either trial drug in 87 (27%) of 320 patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group (34 [11%] discontinued nivolumab only; 29 [9%] discontinued cabozantinib only; 20 [6%] discontinued both nivolumab and cabozantinib simultaneously; and 4 [1%] discontinued both nivolumab and cabozantinib sequentially) and 33 (10%) of 320 in the sunitinib group (appendix p 14). Grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 208 (65%) of 320 patients with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus 172 (54%) of 320 patients with sunitinib, a nominal respective increase from the primary analysis (table 3, appendix p 33). The most common grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse events were hypertension (40 [13%] of 320 patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group vs 39 [12%] of 320 in the sunitinib group), palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia (25 [8%] vs 26 [8%]), and diarrhoea (22 [7%] vs 15 [5%]). The prevalence of the most common organ classes of grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse events over time in each treatment group is shown in appendix p 34.

Table 3:

Treatment-related adverse events in either treatment group

| Nivolumab plus cabozantinib (N=320) | Sunitinib (N=320) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Events | Grades 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grades 1–2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

| Patients with any event | 103 (32) | 186 (58) | 22 (7) | 125 (39) | 152 (48) | 20 (6) |

| Diarrhoea | 168 (53) | 20 (6) | 2 (<1) | 132 (41) | 15 (5) | 0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 115 (36) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 95 (30) | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysaesthesia | 98 (31) | 25 (8) | 0 | 108 (34) | 26 (8) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 79 (25) | 8 (3) | 0 | 86 (27) | 15 (5) | 0 |

| Nausea | 73 (23) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 87 (27) | 0 | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 71 (22) | 18 (6) | 0 | 19 (6) | 3 (<1) | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 71 (22) | 12 (4) | 0 | 33 (10) | 2 (<1) | 0 |

| Dysgeusia | 69 (22) | 0 | 0 | 67 (21) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 65 (20) | 39 (12) | 1 (<1) | 68 (21) | 39 (12) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 65 (20) | 4 (1) | 0 | 53 (17) | 2 (<1) | 0 |

| Mucosal inflammation | 62 (19) | 3 (<1) | 0 | 75 (23) | 7 (2) | 1 (<1) |

| Rash | 60 (19) | 6 (2) | 0 | 21 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 57 (18) | 2 (<1) | 0 | 14 (4) | 0 | 0 |

| Asthenia | 48 (15) | 11 (3) | 0 | 41 (13) | 8 (3) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 47 (15) | 7 (2) | 0 | 69 (22) | 8 (3) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 37 (12) | 4 (1) | 0 | 50 (16) | 2 (<1) | 0 |

| Dysphonia | 37 (12) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 8 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Hypomagnesaemia | 35 (11) | 0 | 1 (<1) | 10 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 34 (11) | 15 (5) | 5 (2) | 24 (8) | 11 (3) | 5 (2) |

| Anaemia | 33 (10) | 2 (<1) | 0 | 55 (17) | 11 (3) | 1 (<1) |

| Amylase increased | 32 (10) | 14 (4) | 0 | 23 (7) | 7 (2) | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 31 (10) | 0 | 0 | 16 (5) | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 21 (7) | 0 | 0 | 32 (10) | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 20 (6) | 1 (<1) | 0 | 49 (15) | 11 (3) | 4 (1) |

| Platelet count decreased | 18 (6) | 0 | 0 | 45 (14) | 12 (4) | 2 (<1) |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | 16 (5) | 0 | 0 | 33 (10) | 0 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 13 (4) | 2 (<1) | 1 (<1) | 39 (12) | 13 (4) | 1 (<1) |

Data are n (%) Shown are grade 1–2 treatment-related adverse events that occurred in ≥10% of patients in either group while patients were receiving the assigned treatment or within 30 days after the end of the trial treatment period. Events are listed in descending order of frequency in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group. One grade 5 event occurred in the sunitinib arm (respiratory distress

Treatment-related serious adverse events of any grade occurred in 83 (26%) of 320 treated patients in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group (grade 3–4: 70 [22%]) and 42 (13%) of 320 treated patients in the sunitinib group (grade 3–4: 31 [10%]). The most common any-grade treatment-related serious adverse events were diarrhoea (11 [3%]), pneumonitis (9 [3%]), and adrenal insufficiency (6 [2%]) in the nivolumab plus ipilimumab group and anaemia (4 [1%]), hyponatraemia (3 [1%]), and thrombocytopenia (3 [1%]) in the sunitinib group.

Grade ≥3 immune-mediated adverse events were uncommon in all patients treated with nivolumab plus cabozantinib (appendix p 18); the most common were increased alanine aminotransferase (9 [3%] of 320), diarrhoea (8 [3%] of 320), and hepatotoxicity (7 [2%] of 320). In the sunitinib group, grade ≥3 immune-mediated adverse events were reported for hypothyroidism, hepatotoxicity, and hyperbilirubinemia (each, 1 [<1%] of 320). Overall, 70 (22%) of 320 patients treated with nivolumab plus cabozantinib received corticosteroids (≥40 mg of prednisone daily or equivalent) for any duration of time to manage immune-mediated adverse events (occurring on therapy or ≤100 days after the end of the trial treatment period); 40 (13%) patients and 16 (5%) patients received corticosteroids (≥40 mg of prednisone daily or equivalent) continuously for ≥14 days and ≥30 days, respectively. Since the primary analysis (database lock, March 30, 2020), no new deaths that investigators considered to be related to treatment occurred with nivolumab plus cabozantinib; one additional death that was considered to be related to treatment occurred with sunitinib (sudden death).

DISCUSSION

Results from this longer-term follow-up (median follow-up for overall survival, 32·9 months) of the phase 3 CheckMate 9ER trial in patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma demonstrated superior efficacy with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib. In the pre-planned final analysis of overall survival per study protocol, median overall survival was longer with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib (37·7 months versus 34·3 months), and the risk of death was decreased (HR 0·70 [95% CI 0·55–0·90]). Median progression-free survival was doubled with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib, and the risk of disease progression or death was decreased by 44%. Objective response rate was higher, and durability of response favoured nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib. Most efficacy benefits favoured nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib regardless of the stratification categories of geographic region, tumour PD-L1 expression, and IMDC prognostic risk category. The IMDC favourable-risk patient subset had relatively few patients included and few deaths were recorded. The evaluation of overall survival was, therefore, challenging due to the lack of death events. Furthermore, this trial was not powered to detect differences in subsets of patients stratified by IMDC risk. The safety profile of nivolumab plus cabozantinib remained consistent with the primary analysis and with previous reports for each agent as monotherapy.1,8,9 No new safety signals emerged, and no further treatment-related deaths occurred in the nivolumab plus cabozantinib group. Some treatment-related adverse events occurred more frequently with nivolumab plus cabozantinib, including diarrhoea, aspartate aminotransferase increased, alanine aminotransferase increased, rash, and pruritus, whereas anaemia, thrombocytopaenia, platelet count decreased, and neutropenia were higher with sunitinib. Nevertheless, patients continue to report improved health-related quality of life with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib; treatment with the combination reduced the risk of meaningful deterioration in health-related quality of life scores and showed a decreased risk of being bothered by treatment side-effects.5 Taken together, these results continue to support nivolumab plus cabozantinib as an effective first-line treatment option for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma.

Other treatment regimens combining immunotherapy with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma have also shown clinical benefits in phase 3 trials versus sunitinib, including the combinations of pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib, pembrolizumab plus axitinib, and avelumab plus axitinib.10–13 However, differences between trials in baseline disease characteristics (ie, IMDC prognostic risk category, previous nephrectomy, sarcomatoid features), differences in efficacy benefits with sunitinib, and differences in follow-up make cross-trial comparisons difficult. Durability of response with nivolumab plus cabozantinib was consistent with an immunotherapy–tyrosine kinase inhibitor combination in this setting, based on evidence from other phase 3 trials.10–12

In pre-specified and post-hoc analyses of patient subgroups of clinical interest at baseline, improved progression-free survival and higher objective response rates with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib were generally observed. Improvements with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib tended to be higher in patients with sarcomatoid features versus those without, and with previous nephrectomy versus those without.

Indeed, efficacy outcomes favouring immunotherapy combined with a tyrosine kinase inhibitor versus sunitinib in subgroup analyses of advanced renal cell carcinoma with sarcomatoid features or previous nephrectomy status at baseline have been reported previously.11,14–17 Nivolumab in dual checkpoint inhibition with ipilimumab has shown substantial long-term efficacy benefits in patients with sarcomatoid features.18 Our data show improved survival and objective response with nivolumab plus cabozantinib in patients with sarcomatoid features.

Efficacy benefit with nivolumab and cabozantinib in subgroups according to organ site of metastasis at baseline (liver, bone, and lung) is consistent with benefits previously observed in bone and visceral sites with nivolumab and cabozantinib in combination versus sunitinib, and both agents as monotherapies versus everolimus.1,19–21 Bone metastasis occurs in 35–40% of advanced renal cell carcinoma cases, often leading to skeletal-related events, impaired quality of life, and poor survival outcomes.22,23 Here, nivolumab plus cabozantinib improved survival outcomes and objective responses compared with sunitinib in this patient subgroup.

In the novel post-hoc exploratory assessment of the depth of response in target lesion organ sites, a higher proportion of patients experienced tumour shrinkage with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib, regardless of organ site.

A potential limitation of this trial is the lack of masking, due to its open-label nature. This bias was mitigated in part through the use of BICR for radiographical assessments. In the subgroup analysis of efficacy by organ site of metastasis, most patients had additional organ sites of target/non-target lesions. The depth of response analysis is limited by its post-hoc exploratory nature and by the relatively small number of patients analysed with target kidney, liver, and bone lesions. Additionally, radiographical assessments of target bone lesions were only available per investigator.

Ongoing and future investigations of interest with nivolumab plus cabozantinib may include characterisation of response and safety after additional study follow-up, and also take into consideration the unmet needs identified in renal cell carcinoma.24–26 For example, a role for nivolumab plus cabozantinib in patients with advanced non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma who have not received prior PD-1/PD-L1 directed therapy is being explored in the phase 2 open-label CA209–9KU trial (NCT03635892). Promising efficacy has been observed in papillary, unclassified, or translocation-associated histologies (median progression-free survival, 12·5 months; median overall survival, 28 months; objective response, 47·5%).27 A role for nivolumab plus cabozantinib in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma and IMDC intermediate- or poor-risk disease without complete response or progressive disease after first-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab treatment is being assessed in the phase 3 PDIGREE trial (NCT03793166). Additionally, the efficacy of nivolumab plus cabozantinib in triplet combination with ipilimumab is being explored in patients with previously untreated advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma and IMDC intermediate- or poor-risk disease (COSMIC-313, NCT03937219), in which the correlation of biomarkers with clinical outcomes will also be assessed.28

Research in context panel

Evidence before this study

We performed a literature search in PubMed for published clinical trial reports, with no restrictions on language, from database inception until January 29, 2022, using the terms “nivolumab,” “advanced renal cell carcinoma,” and “renal cell carcinoma,” filtered by clinical trial article type. Our search found several published randomised phase 3 trials in patients with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma that were done to evaluate anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 agents combined with a VEGF(R)-tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Dual checkpoint inhibition with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, with its long-term efficacy and safety demonstrated in the CheckMate 214 trial, led to a paradigm shift in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. The combination of an immune checkpoint inhibitor with a VEGF(R)-tyrosine kinase inhibitor has added to the treatment armamentarium for renal cell carcinoma. The combinations of pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib, pembrolizumab plus axitinib, and avelumab plus axitinib have each demonstrated superior efficacy over sunitinib in previously untreated advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. In addition to these, the primary analysis of the randomised phase 3 CheckMate 9ER trial showed significant progression-free survival, overall survival, and objective response benefit with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib in the first-line treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma with a clear cell component. On this basis of these results, nivolumab plus cabozantinib was approved in the United States and Europe as a first-line treatment option in this setting.

Added value of this study

In this pre-planned final analysis of overall survival per study protocol from CheckMate 9ER with an extended median follow-up of 32·9 months, we report that nivolumab plus cabozantinib improved overall survival, progression-free survival, and objective response versus sunitinib among all randomised patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma, and among patient subgroups of clinical interest at baseline. We also report that tumour responses were deeper with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib in all target lesion organ sites assessed. No new safety signals were identified with nivolumab plus cabozantinib treatment.

Implications of all the available evidence

These data show improved efficacy with nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib with extended follow-up in the overall population and among multiple baseline subgroups of clinical interest, including patients with sarcomatoid features, prior nephrectomy, and different sites of metastases. Overall, these data further support nivolumab plus cabozantinib as an effective first-line treatment option for advanced renal cell carcinoma among a broad range of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by Bristol Myers Squibb in collaboration with Ono Pharmaceutical and with Exelixis, Ipsen Pharma, and Takeda Pharmaceutical. We thank the patients who participated in this study, the clinical study teams, and the representatives of the sponsor who were involved in data collection and analyses. We would like to acknowledge Tanvi Gangal (Bristol Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ) for serving as protocol manager. Medical writing support was provided by Tom Vizard, PhD, of Parexel, and was funded by Bristol Myers Squibb. Patients treated at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center were supported in part by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant (Core Grant, number P30 CA008748). Dr Porta is now with University of Bari ‘A. Moro,’ Bari, Italy.

Declaration of interests

RJM reports advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Aveo Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, EMD Serono, Exelixis, Genentech/Roche, Incyte, Lilly Oncology, Merck, Novartis, and Pfizer; and institutional funding from Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Eisai, Exelixis, Genentech/Roche, Merck, and Pfizer.

TP reports grants from AstraZeneca, Roche, BMS, Exelixis, Ipsen, Merck, Merck Sharp and Dohme (MSD), Novartis, Pfizer, Seattle Genetics, Merck Serono, Astellas Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, and Eisai; consulting fees from BMS, Merck, AstraZeneca, Ipsen, Pfizer, Novartis, Incyte, Seattle Genetics, Roche, Exelixis, MSD, Merck Serono, Astellas Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, and Eisai; and travel support from Pfizer, MSD, AstraZeneca, Roche, and Ipsen.

MB reports consulting fees from Roche/Genentech, BMS, MSD Oncology, Novartis, AstraZeneca; and speakers bureau fees from Roche/Genentech, MSD Oncology, BMS, and AstraZeneca.

BE reports institutional research grant from BMS; consulting fees from Pfizer, BMS, Ipsen, AVEO, Oncorena, and Eisai; honoraria from Pfizer, BMS, Ipsen, Oncorena, and Eisai; and travel support from BMS, Ipsen, and MSD.

MTB reports consulting fees from BMS, Asofarma, Eisai, MSD Oncology, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, Bayer, and Ferring; speakers bureau fees from Asofarma, MSD Oncology, BMS, Bayer, Eisai, Janssen Oncology, Ipsen, Pfizer, Merck, Ferring, Tecnofarma, Medicamenta, AstraZeneca, and Astellas Pharma; honoraria from BMS and Tecnofarma; payment for expert testimony from Asofarma; travel support from Asofarma, Janssen-Cilag, MSD Oncology, BMS Mexico, Pfizer, Ipsen, and Sanofi; and steering committee honoraria from BMS.

AYS reports research grants from BMS, Eisai, 4D Pharma, and EMD Serono; consulting fees from Exelixis, BMS, Pfizer, and EMD Serono; and honoraria from Eisai and Oncology Information Group.

C Suárez research grants from AB Science, Aragon Pharmaceuticals, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca AB, Bayer, Blueprint Medicines Corporation, Boehringer Ingelheim España S.A., BMS, Clovis Oncology, Exelixis, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffman-La Roche, Novartis Farmaceutica S.A., Pfizer S.L.U., and Sanofi-Aventis; speakers bureau fees from Astellas Pharma, Bayer, BMS, EUSA Pharma, Hoffmann-La Roche, Ipsen, and Pfizer; and advisory board fees from Astellas Pharma, Bayer, BMS, EUSA Pharma, Hoffman-La Roche, Ipsen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis.

AH advisory board fees from MSD and Janssen.

CP reports consulting fees from Angelini Pharma, AstraZeneca, BMS, Eisai, EUSA Pharma, Ipsen, Merck Serono, and MSD; speakers bureau fees from BMS, EUSA Pharma, General Electric, Ipsen, and MSD; payment for expert testimony from EUSA Pharma and Pfizer; and travel support from Roche.

CMH reports institutional research grant from BMS; and stock options from Telix Pharmaceuticals, Volpara Health Technologies, Alcidon, and Nanosonics.

ERK reports personal research grant from Medivation/Astellas; institutional research grant from BMS, Genentech/Roche, Pfizer, and Merck Serono; and stock options from Johnson & Johnson.

HG reports advisory board fees from BMS, Ipsen, MSD, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, Roche, and Merck Serono; speakers bureau fees from Merck Serono; and travel support from AstraZeneca.

YT reports institutional research grants from Ono Pharmaceuticals, Takeda, and Astellas; and honoraria from BMS, Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Astellas.

JB reports institutional research grants from BMS, Astellas Pharma, Ipsen, MSD Oncology, Novartis, Roche, Exelixis, Pfizer, and Seagen; consulting fees from BMS, Eisai, EUSA Pharma, Ipsen, MSD Oncology, AstraZeneca, Roche, Pfizer, and Merck KGaA; and speakers bureau fees from MSD Oncology, BMS, Merck KGaA, Pfizer, Ipsen, and Roche.

JZ is employed by and has stock ownership in BMS.

BS is employed by and has stock ownership in BMS.

C Scheffold is employed by and has stock ownership in Exelixis.

ABA has nothing to disclose.

TKC reports research grants, consulting fees, honoraria, and advisory board fees from AstraZeneca, Aravive, AVEO, Bayer, BMS, Calithera, Circle Pharma, Eisai, EMD Serono, Exelixis, GlaxoSmithKline, IQVIA, Infinity, Ipsen, Janssen, Kanaph, Lilly, Merck, NiKang, Nuscan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Surface Oncology, Takeda, Tempest, UpToDate, CME events (Peerview, OncLive, MJH, and others), outside the submitted work; institutional patents filed on molecular mutations and immunotherapy response, and ctDNA; leadership fees from NCCN, GU Steering Committee, ASCO, and ESMO; stock ownership in Pionyr, Tempest, Osel, and NuscanDx; other financial or non-financial interests include medical writing and editorial assistance support that may have been funded by communications companies in part; potential funding (in part) from non-US sources/foreign components for mentor of several non-US citizens on research projects; independent funding by drug companies and/or royalties potentially involved in research around the subject matter (institutional); support in part by the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Kidney SPORE (2P50CA101942–16) and Program 5P30CA006516–56, the Kohlberg Chair at Harvard Medical School and the Trust Family, Michael Brigham, and Loker Pinard Funds for Kidney Cancer Research at DFCI.

Contributor Information

Robert J Motzer, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA.

Thomas Powles, Department of Genitourinary Oncology, Barts Cancer Institute, Cancer Research UK Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, Queen Mary University of London, Royal Free National Health Service Trust, London, UK.

Mauricio Burotto, Bradford Hill Clinical Research Center, Santiago, Chile.

Bernard Escudier, Department of Medical Oncology, Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France.

Maria T Bourlon, Department of Hemato-Oncology, Urologic Oncology Clinic, Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, Mexico City, Mexico.

Amishi Y Shah, Department of Genitourinary Medical Oncology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Cristina Suárez, Department of Medical Oncology, Vall d’Hebron Institute of Oncology (VHIO), Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron, Vall d’Hebron Barcelona Hospital Campus, Barcelona, Spain.

Alketa Hamzaj, Department of Medical Oncology, Ospedale San Donato, Istituto Toscano Tumori, Arezzo, Italy.

Camillo Porta, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy.

Christopher M Hocking, Cancer Clinical Research Unit, Lyell McEwin Hospital, Elizabeth Vale, SA, Australia.

Elizabeth R Kessler, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA.

Howard Gurney, Department of Clinical Medicine, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Yoshihiko Tomita, Departments of Urology and Molecular Oncology, Niigata University Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Niigata, Japan.

Jens Bedke, Department of Urology, Eberhard Karls University Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany.

Joshua Zhang, Department of Clinical Research.

Burcin Simsek, Global Biometrics and Data Science, Bristol Myers Squibb, Princeton, NJ, USA.

Christian Scheffold, Department of Clinical Development, Exelixis, Inc., Alameda, CA, USA.

Andrea B Apolo, Genitourinary Malignancies Branch, Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Toni K Choueiri, Department of Medical Oncology, Lank Center for Genitourinary Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Data sharing

Bristol Myers Squibb’s policy on data sharing can be found online (https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/independent-research/datasharing-request-process.html). De-identified and anonymised datasets of clinical trial information, including patient-level data, will be shared with external researchers for proposals that are complete, for which the scientific request is valid and the data are available, consistent with safeguarding patient privacy and informed consent. Upon execution of an agreement, the de-identified and anonymised datasets can be accessed via a secured portal that provides an environment for statistical programming with R as the programming language. The protocol and statistical analysis plan will also be available. Data will be available for 2 years from the study completion or termination of the programme (May 2024).

References

- 1.Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 829–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Kidney cancer (v.2.2022). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/kidney.pdf (accessed October 20, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Powles T, Albiges L, Bex A, et al. ESMO clinical practice guideline update on the use of immunotherapy in early stage and advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2021; 32: 1511–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cella D, Motzer RJ, Suarez C, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with first-line nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated in CheckMate 9ER: an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2022; 23: 292–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cella D, Motzer RJ, Blum SI, et al. Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in previously untreated patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC): CheckMate 9ER updated results. J Clin Oncol 2022; 40(suppl 6): 323. [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics 1979; 35: 549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clopper CP, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika 1934; 26: 404–14. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choueiri TK, Hessel C, Halabi S, et al. Cabozantinib versus sunitinib as initial therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma of intermediate or poor risk (Alliance A031203 CABOSUN randomised trial): progression-free survival by independent review and overall survival update. Eur J Cancer 2018; 94: 115–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1803–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Powles T, Plimack ER, Soulieres D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-426): extended follow-up from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 1563–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ, Rini BI, et al. Updated efficacy results from the JAVELIN Renal 101 trial: first-line avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol 2020; 31: 1030–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY, et al. Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2021; 384: 1289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quhal F, Mori K, Bruchbacher A, et al. First-line immunotherapy-based combinations for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Urol Oncol 2021; 4: 755–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motzer RJ, Choueiri TK, Powles T, et al. Nivolumab + cabozantinib (NIVO+CABO) versus sunitinib (SUN) for advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC): outcomes by sarcomatoid histology and updated trial results with extended follow-up of CheckMate 9ER. J Clin Oncol 2021; 39(suppl 6): 308.33356420 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porta C, Burotto M, Suarez C, et al. First-line nivolumab + cabozantinib vs sunitinib in patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC) in subgroups based on prior nephrectomy in the CheckMate 9ER trial. Ann Oncol 2021; 32 (suppl 5): S678–S724. 10.1016/annonc/annonc675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab (pembro) plus axitinib (axi) versus sunitinib as first-line therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): outcomes in the combined IMDC intermediate/poor risk and sarcomatoid subgroups of the phase 3 KEYNOTE-426 study. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37(suppl 15): 4500. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motzer RJ, Porta C, Eto M, et al. Phase 3 trial of lenvatinib (LEN) plus pembrolizumab (PEMBRO) or everolimus (EVE) versus sunitinib (SUN) monotherapy as a first-line treatment for patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC) (CLEAR study). J Clin Oncol 2021; 39(suppl 6): 269.33275488 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tannir NM, Signoretti S, Choueiri TK, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment of patients with advanced sarcomatoid renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2021; 27: 78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Escudier B, Sharma P, McDermott DF, et al. CheckMate 025 randomized phase 3 study: Outcomes by key baseline factors and prior therapy for nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol 2017; 72: 962–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choueiri TK, Escudier B, Powles T, et al. Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR): final results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 917–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Apolo AB, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus cabozantinib (N+C) versus sunitinib (S) for advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC): outcomes by baseline disease characteristics in the phase 3 CheckMate 9ER trial. J Clin Oncol 2021; 39(suppl 15): 4553. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coleman RE, Croucher PI, Padhani AR, et al. Bone metastases. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020; 6: 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grünwald V, Eberhardt B, Bex A, et al. An interdisciplinary consensus on the management of bone metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Urol 2018; 15: 511–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choueiri TK, Atkins MB, Bakouny Z, et al. Summary from the first Kidney Cancer Research Summit, September 12–13, 2019: a focus on translational research. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021; 113: 234–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Braun DA, Bakouny Z, Hirsch L, et al. Beyond conventional immune-checkpoint inhibition— novel immunotherapies for renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021; 18: 199–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choueiri TK, Motzer RJ. Systemic Therapy for Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 354–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee CH, Voss MH, Carlo MI, et al. Phase II Trial of Cabozantinib Plus Nivolumab in Patients With Non-Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma and Genomic Correlates. J Clin Oncol 2022: JCO2101944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choueiri TK, Albiges L, Powles T, Scheffold C, Wang F, Motzer RJ. A phase III study (COSMIC-313) of cabozantinib (C) in combination with nivolumab (N) and ipilimumab (I) in patients (pts) with previously untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC) of intermediate or poor risk. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38(suppl 6): TPS767-TPS. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Bristol Myers Squibb’s policy on data sharing can be found online (https://www.bms.com/researchers-and-partners/independent-research/datasharing-request-process.html). De-identified and anonymised datasets of clinical trial information, including patient-level data, will be shared with external researchers for proposals that are complete, for which the scientific request is valid and the data are available, consistent with safeguarding patient privacy and informed consent. Upon execution of an agreement, the de-identified and anonymised datasets can be accessed via a secured portal that provides an environment for statistical programming with R as the programming language. The protocol and statistical analysis plan will also be available. Data will be available for 2 years from the study completion or termination of the programme (May 2024).