Abstract

Synaptotagmin 7 (Syt7) is a multifunctional calcium sensor expressed throughout the body. Its high calcium affinity makes it well suited to act in processes triggered by modest calcium increases within cells. In synaptic transmission, Syt7 has been shown to mediate asynchronous neurotransmitter release, facilitation, and vesicle replenishment. In this review we provide an update on recent developments, and the newly emerging roles of Syt7 in frequency invariant synaptic transmission and in suppressing spontaneous release. Additionally, we discuss Syt7’s regulation of membrane fusion in non-neuronal cells, and its involvement in disease. How such diversity of functions is regulated remains an open question. We discuss several potential factors including temperature, presynaptic calcium signals, the localization of Syt7, and its interaction with other Syt isoforms.

Background

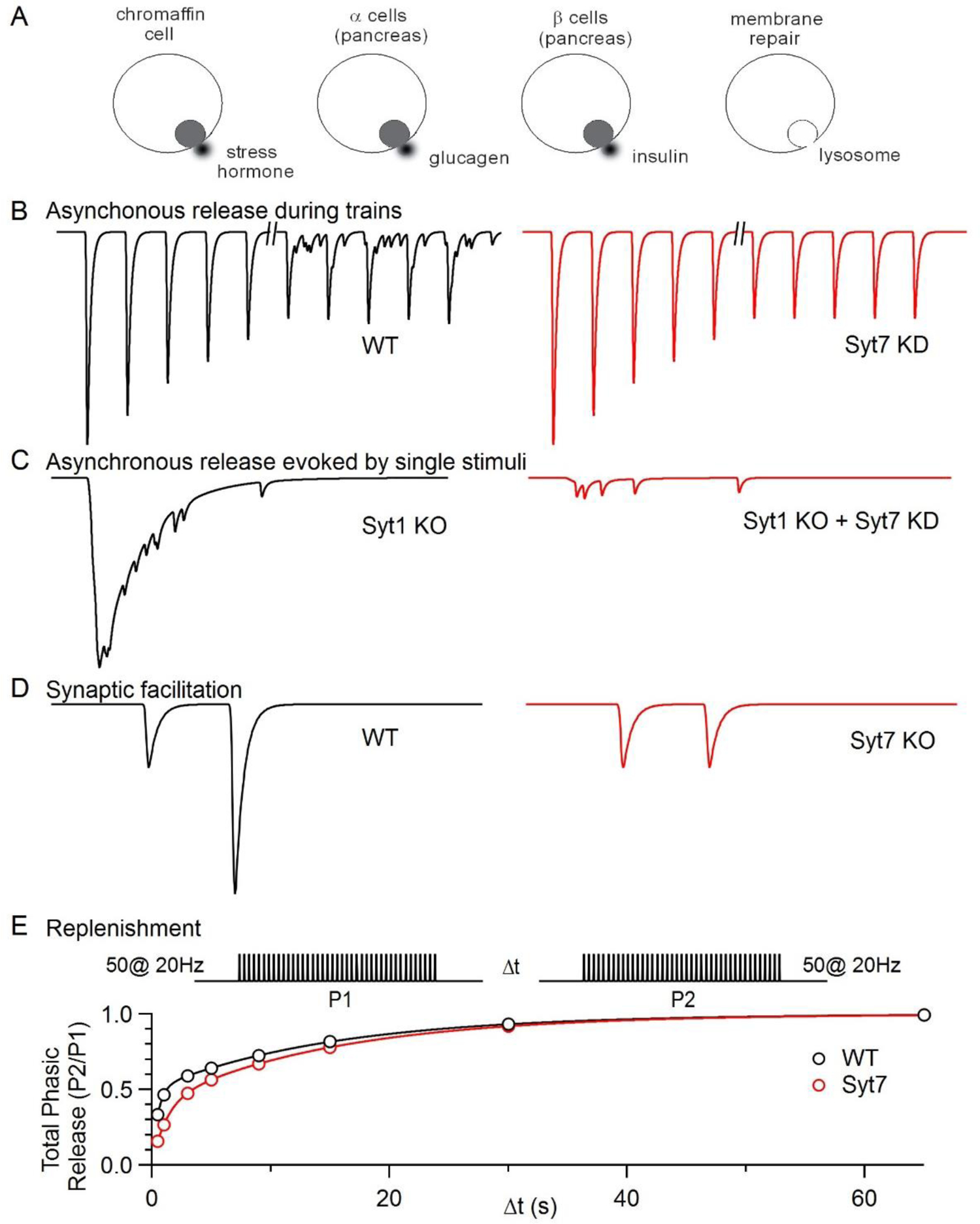

Syt7 binds calcium with high-affinity and slow kinetics [1–3], making it well suited to sense low levels of residual calcium (typically submicromolar) that linger long after elevated activity. This contrasts with the fast Syt isoforms, Syt1 and Syt2, which mediate synchronous vesicle fusion, by binding calcium rapidly with low affinity [4,5]. Syt7 is involved in many processes in non-neuronal cells (Fig. 1A), including chromaffin cells, and pancreatic α and β cells. Here, Syt7 mediates secretion of stress hormone, insulin, and glucagon. In addition, Syt7 also mediates lamellar body exocytosis, phagocytosis, bone remodeling, lysosomal exocytosis and membrane repair (reviewed in [6]). Early reports placed Syt7 on the plasma membrane in synapses [7,8], while in PC12 and chromaffin cells it was found on the secretory granule [9–11], suggesting its localization might differ depending on the cell type.

Figure 1. Proposed functional roles of Synaptotagmin 7.

Simplified schematics summarize some of the primary roles proposed for Syt7.

A. Secretion of stress hormone (chromaffin cell), glucagen (α cells pancreas), insulin (β cells pancreas), and lysosomes for membrane repair.

B. At the zebrafish NMJ 100 Hz activation initially evokes rapid EPSCs without AR but after several minutes AR is apparent in WT animals but not in Syt7 KO animals. Schematic based on [13].

C. AR is evoked by single stimuli in cultured hippocampal cells in Syt1 KO animals and this release is largely eliminated by knocking down Syt7. Schematic based on [14].

D. Activation of synapses with two closely spaced stimuli results in synaptic facilitation in WT animals that is absent in Syt7 KO animals. Schematic based on [15].

E. (left) Synapses were activated with 50 action potentials at 20 Hz and the total charge transfer arising from this stimulus was quantified (P1). After waiting Δt, synapses were again activated and the total charge transfer was quantified (P2). Recovery was more rapid at short times for WT animals. Similar experiments, but using sucrose, also found that recovery from depression was more rapid in WT mice. Schematic based on [17].

Syt7 is also implicated in diverse aspects of synaptic transmission. It contributes to asynchronous release (AR), a component of release that is not tightly locked to presynaptic action potentials, but triggered by a small residual calcium signal that remains elevated for tens of milliseconds following an action potential [12]. This was first shown at the zebrafish neuromuscular junction (NMJ). Here, release evoked by stimulus trains was initially synchronous, but during sustained stimulation AR became prominent. This AR component was strongly attenuated by Syt7 knockdown (Fig. 1B, [13]). After a single presynaptic action potential, AR is usually small or absent, but it can become prominent in the absence of fast Syt isoforms (Fig. 1C). Calcium binding to the C2A domain of Syt7 was shown to be required for this AR [14]. These findings suggested that AR does not require the involvement of fast Syt isoforms, and is evoked by Syt7 responding to residual calcium. In addition, Syt7 can mediate synaptic facilitation in which the second of two closely spaced stimuli is more effective at evoking neurotransmitter release (Fig. 1D, [15]). Synaptic facilitation is distinct from AR in that it involves Syt7 enhancing synchronous release mediated in part by fast Syt isoforms. Facilitation is a widespread form of plasticity that is apparent at many synapses with a low initial release probability (PR) [16]. Finally, Syt7 can also interact with calmodulin to promote rapid calcium-dependent recovery from depression (Fig. 1E, [17]). Syt7’s high affinity calcium binding appears to be essential for it to function in these processes, and in many cases, Syt7 appears to work in concert with other Syt isoforms [18].

Syt7 involvement in many different processes in many types of cells, has been reviewed recently [6,18]. In this review we will summarize advances of the past two years, and conclude by highlighting the open questions that remain regarding the functions and mechanisms, including a discussion of the many potential factors regulating Syt7.

Recent Progress

Asynchronous Release

Recent studies revealed that Syt7 makes diverse contributions to AR at different synapses. At both the molecular layer interneuron to Purkinje cell (MLI to PC) synapse and the calyx of Held synapse, AR is similar to the zebrafish NMJ (Fig. 1B). In these synapses, AR is not apparent following single stimuli, but AR increases during prolonged stimulus trains [•19,•20]. At MLI to PC synapses most release was synchronous, but a component of AR became apparent during 20 Hz stimulation; this component was reduced to about 50% in Syt7 knock-out (KO) mice [•20]. At the calyx of Held synapse, prolonged 100 Hz activation led to buildup of a steady-state component, which was attributed to AR. This component was reduced to ~50% in Syt7 KO mice. It was concluded that stimulus trains activate Syt7 to promote AR, which could allow high frequency presynaptic activation to more reliably evoke postsynaptic firing [•19]. Similarly, in somatosensory cortex pyramidal cell to Martinotti cell (SSC-PC to MC) synapses pronounced AR during (and after) 100Hz stimulation was reduced to ~50% in Syt7 KO mice [21]. Contrary to the examples above, at the granule cell to Purkinje cell (grC to PC) synapse single stimuli evoked synchronous release that is accompanied by AR, which decayed with a time constant of ~4 ms. In Syt7 KO animals, AR was reduced to ~35% [•22]. These findings indicate that in wild-type (WT) animals most AR at the grC to PC synapse is Syt7 dependent.

However, at the PC to deep cerebellar nuclei (DCN) synapse, AR was not apparent following single stimuli or during high frequency trains, despite the presence of Syt7 [••23]. This seemingly contradictory finding may be explained by the presence of Syt isoforms (Syt1 or Syt2) with low calcium affinity and rapid kinetics, which have a profound effect on AR at other synapses. When these are knocked out, rapid vesicle fusion is eliminated and AR becomes prominent [4,5]. Fast Syt isoforms can suppress AR [24–26], although the extent of suppression is strongly reduced at room temperature [•27]. It is possible that sensors for rapid release and AR are in competition [28,29]. As such, in order to promote AR levels of fast sensors need to be low and levels of sensors for AR must be high. This is consistent with a recent study of inhibitory synapses made by DCN neurons onto cells in the inferior olive (IO). DCN to IO synapses have exclusively AR [•30]. These synapses lack fast Syt isoforms in WT animals, but viral expression of Syt1 in presynaptic cells makes these synapses exclusively rapid and eliminates AR. Interestingly, in Syt7 KO animals AR is still present at the DCN to IO synapse, but it has extremely slow kinetics. This suggests that Syt7 helps to mediate AR at this synapse in WT animals, but in the absence of Syt7 an additional unidentified calcium sensor mediates slow AR.

The recent studies of AR at the calyx of Held, the PC to MC, the MLI to PC, the grC to PC, the PC to DCN and the DCN to IO synapse found that AR was reduced but not eliminated in Syt7 KO mice [•19–••23,•30]. This is in line with the idea that other calcium sensors can also mediate AR. At the calyx of Held, a further reduction in AR in Syt2/Syt7 DKO mice suggests that Syt2 contributes to AR [•19]. At the grC to PC synapse, AR evoked by Syt7 and the AR that remains in Syt7 KO mice have similar kinetics [•22]. However, at the DCN to IO synapse the kinetics are slowed considerably in Syt7 KO mice [•30]. Together, these studies suggest that multiple calcium sensors can evoke AR, some with even slower kinetics than Syt7.

Facilitation

The properties of synaptic facilitation are highly variable at different synapses, but in most cases facilitation is completely or substantially Syt7 dependent (Table 1). Perhaps the simplest measure of facilitation is to quantify the paired-pulse ratio (PPR) as a function of interstimulus interval. For paired-pulse facilitation PPR>1, and for paired-pulse depression PPR<1. At a number of hippocampal, cerebellar and corticothalamic synapses, the magnitude of paired-pulse facilitation ranges from 1.2 to 3.2 and the time constant of facilitation ranges from 18 to 150 ms [15,•20,•22]. Despite the diverse properties of paired-pulse facilitation, Syt7 has a major influence on facilitation at all of these synapses. At three hippocampal synapses, thalamocortical synapses, and the MLI to PC synapse, facilitation is entirely eliminated in Syt7 KO [15,•20].

Table 1.

Contribution of Syt7 to synaptic transmission at different synapses.

| Synapse | Wild-type | Syt7 KO | Syt7− dependent recovery | T (°C) | Cae mM | Reference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPF | τ (ms) | train | ARs | ARt | PPF | τ (ms) | train | ARs | ARt | |||||

| PP to grC | 0.8 | 150 | 0.14 | − | − | − | − | 33 | 2 | [15] | ||||

| MF to CA3 | 1.3 | 18 | 10 | − | − | 1.9 | − | 33 | 2 | |||||

| CA3 to CA1 | 1.2 | 105 | 0.6 | − | − | − | − | 33 | 2 | |||||

| corticothalamic | 2.2 | 103 | 2.8 | − | − | − | − | 33 | 2 | |||||

| SSC-PC to MC | 0.4 | 2.2 | ++ | 0.2 | 1.2 | + | 35 | 2 | [21] | |||||

| MLI to PC | 1.2 | − | ++ | − | − | + | yes | 22 | 2 | [•20] | ||||

| grC to PC | 2.1 | 85 | ++ | 1 | 46 | + | 22 | 2 | [•22] | |||||

| 1.8 | 64 | 0.9 | 17 | 35 | 1.5 | |||||||||

| grC to MLI | 1.5 | 132 | ++ | 0.7 | 35 | + | 22 | 2 | ||||||

| PC to DCN | 0.2 | 1.1 | − | − | − | −0.4 | − | − | 35 | 0.3 | [••23] | |||

| − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | no | 35 | 1.5 | ||||

| vestibular | 0.8 | − | − | − | 0.1 | − | − | 35 | 0.5 | |||||

| − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | no | 35 | 1.5 | ||||

| calyx of Held | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.55 | 1.2 | 22 | 0.6 | [•19] | |||||||

| − | − | − | ++ | − | + | no | 22 | 2 | ||||||

Abbreviations:

PP to grC: perforant path to hippocampal granule cell synapse

MF to CA3: Mossy fiber to CA3 pyramidal cell synapse

CA3 to CA1: hippocampal CA3 to CA1 pyramidal cell synapse

Corticothalamic: synapse between layer VI cells and thalamic relay neurons

SSC-PC to MC: Somatosensory cortex pyramidal cell to Martinotti cell

MLI to PC: synapse between cerebellar molecular layer interneurons and Purkinje cells

grC to PC: cerebellar granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse

grC to MLI: cerebellar granule cell to molecular layer interneuron synapse

PC to DCN: Purkinje cell to deep cerebellar nuclei synapse

PPF: amplitude of paired pulse facilitation for 2 closely spaced stimuli (A2/A1−1).

τ: time constant of decay of PPF.

Train: peak amplitude of enhancement during a stimulus train (An/A1−1). Consult original references for details.

ARs: AR following a single stimulus.

ARt: AR during a prolonged trains of high frequency stimulation.

Syt7 dependent recover is a qualitative assessment of whether recovery from depression after high frequency stimulation is Syt7 dependent.

Cae: external calcium levels.

Grey, no information; dark green, large effects; light green, small effects; red, no effect.

An increase in the initial PR can indirectly influence short term plasticity, as increased pool depletion may obscure facilitation. However, no difference in initial PR was observed at numerous types of synapses in Syt7 KO mice, across a number of different methods [15,17,•19–••23,31]. Furthermore, even when extracellular calcium was lowered, facilitation did not reappear in Syt7 KO mice, arguing against a role for depletion [15].

Other synapses, such as the PC to DCN synapse, the calyx of Held and vestibular synapses have a high PR that depletes the release ready pool (RRP) [•19,••23]. Under standard experimental conditions, this leads to strong paired pulse depression, obscuring any contribution of facilitation. However, decreasing external calcium lowers PR, reduces depletion and can reveal facilitation. At the PC to DCN and vestibular synapses, in low external calcium, paired pulse facilitation is small, but an approximately two-fold facilitation is apparent during prolonged high frequency stimulation that is absent in Syt7 KO animals [••23]. At the calyx of Held synapse facilitation is apparent in low calcium, but the extent of facilitation is unaltered in Syt7 KO animals [•19]. This is consistent with previous studies suggesting that other mechanisms, such as use-dependent increases in calcium entry, contribute to facilitation [32–34], but it is not clear why Syt7-dependent facilitation is absent at this synapse.

At synapses made by cerebellar grCs onto MLIs and PCs, a facilitation component also remains in Syt7 KO animals, though greatly reduced in magnitude and duration. This component remained EGTA sensitive, indicating that the mechanism for this facilitation is also calcium dependent [•22]. The more rapid kinetics suggest that it could be mediated by a calcium sensor with different calcium binding properties than Syt7. Additionally, at the grC to PC synapse the decrease in time course of facilitation in Syt7 KO animals is much more pronounced under physiological conditions, than at room temperature (Table 1). This indicates that the remaining facilitation mechanism in Syt7 KO animals is highly temperature dependent.

Thus, although numerous mechanisms may contribute to synaptic facilitation, at most facilitating synapses characterized to date, Syt7 determines a substantial fraction, or all, of the facilitation.

Regulation of vesicle pools

Syt7 has also been implicated in regulation of vesicle pools. A Syt7-dependent increase in replenishment of the RRP could provide a means of increasing steady state synaptic strength during high frequency stimulation [17]. The original study of Syt7 and replenishment was not performed in physiological conditions (10 mM external Ca, room temperature [17]). However, a recent study found that Syt7 also promotes replenisment in more physiological conditions at the MLI to PC synapse (2 mM external Ca, room temperature [•20]). Based on plots of cummulative Inhibitory Post-Synaptic Current (IPSC) amplitude vs stimulus number, it was concluded that replenishment rates during 100 Hz trains were reduced by ~22% in Syt7 KOs. Furthermore, following high frequency stimulation, synaptic strength recovered with a time constant of 4 s in WT animals and 7 s in Syt7 KO animals [•20]. In contrast, at the calyx of Held synapse, the amplitude of Excitatory Post-Synaptic Currents (EPSCs) evoked by high-frequency trains was unaffected in Syt7 KOs, suggesting that replenishment is not impaired [•19]. Similarly, at the PC to DCN synapse, recovery from depression was not slowed in Syt7 KO animals. Though Syt7 KO reduced steady-state synaptic strength during high-frequency trains in this synapse, this could be entirely accounted for by a reduction in facilitation [••23]. Overall, replenishment estimates based on cumulative synaptic current need to be interpreted with caution, as many different synaptic properties can influence this measure [•35,36].

Contributions from Syt7 to additional processes have recently been identified. The size of the reserve and resting pools were found to be larger in Syt7 KOs [37], though this is not in line with previous observations [17,38]. Several Syts, including Syt7, have also been shown to regulate endocytosis [8,39–41]. Multi-vesicular asynchronous release, was found to be specifically targeted to a slower Syt7-dependent endocytic pathway that, enigmatically, did not require Syt7’s C2 domains [42].

In conclusion, while there are several indications of Syt7 regulating vesicle pools, the mechanism behind this and the impact on release remain unclear.

Frequency Invariance

It had been established that Syt7 can facilitate evoked transmission and mediate AR. However, Syt7 is also present in PCs, that make depressing synapses onto DCN neurons and that do not have prominent AR. What could Syt7 be doing at PC to DCN synapses? Frequency invariant synaptic transmission, an unusual property of PC to DCN synapses, provided a clue.

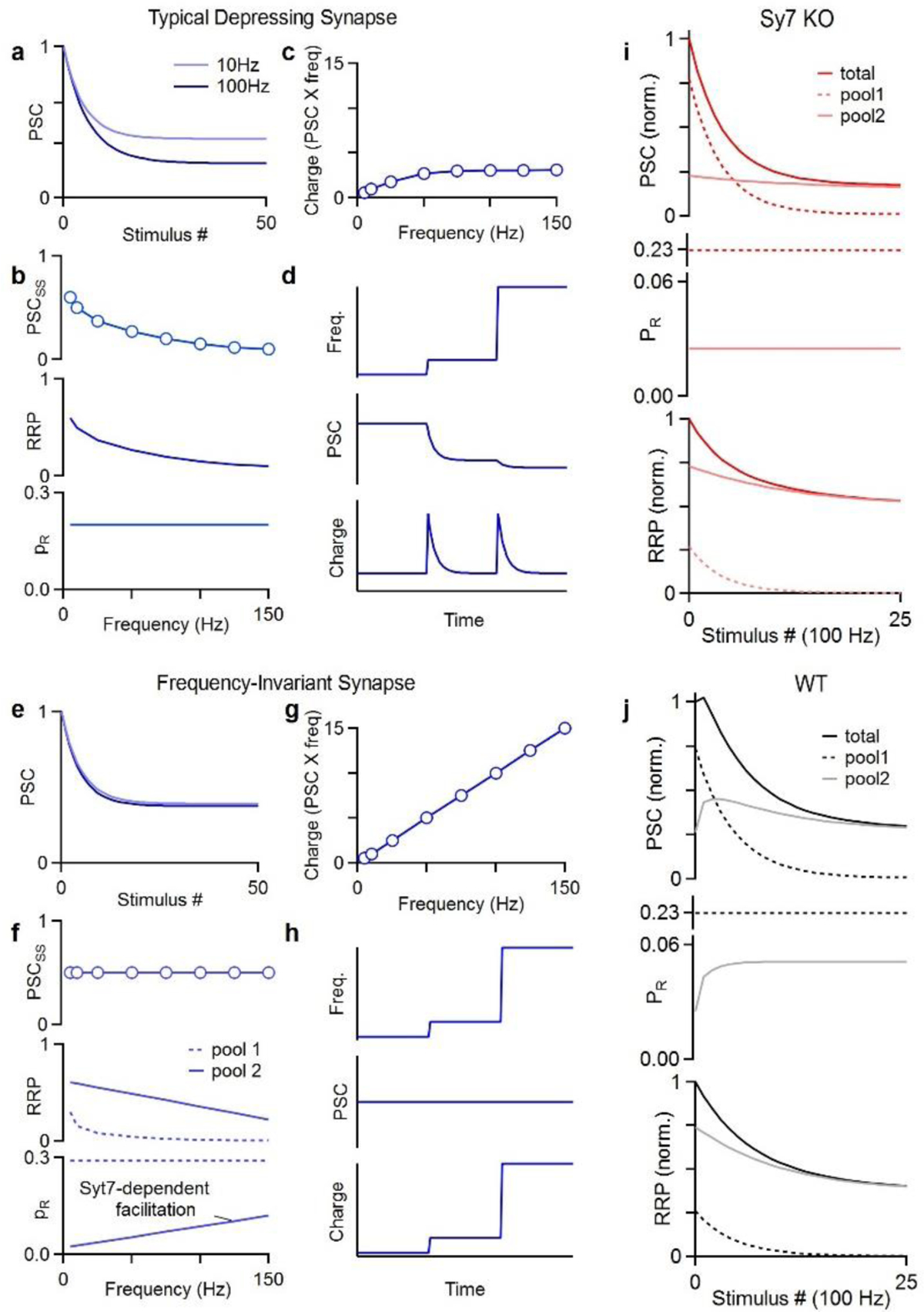

Most synapses depress more prominently when the activation frequency is increased (Fig. 2a, b top). This is attributed to depletion of the RRP (Fig. 2b). For such synapses, the charge transfer (synaptic current amplitude × frequency) is sublinear (Fig. 2c). Such synapses are very effective at conveying a change in stimulus frequency rather than absolute frequency (Fig. 2d [43]). In contrast, frequency invariant synapses depress to the same steady-state levels for a broad range of stimulus frequencies (Fig. 2e, f top). Frequency invariance is a relatively rare synaptic attribute that was first described at vestibular synapses [44], but has subsequently been observed at PC to DCN synapses and MLI to PC synapses [•20,45,46]. Such synapses convey charge transfer that scales linearly with stimulation frequency (Fig. 2g), and they faithfully convey the rate of presynaptic activation (Fig. 2h).

Figure 2. Syt7 allows synapses to be frequency invariant.

a. For a typical depressing synapse, high frequency stimulation results in depression to a steady-state level that is smaller for higher frequencies (100 Hz vs 10 Hz).

b. The frequency dependence of steady-state synaptic strength (PSCSS) is attributed to depletion of the RRP that is more pronounced when there is less time for recovery between stimuli.

c. The charge transfer (PSC × stimulus frequency) as a function of stimulus frequency is sublinear and eventually plateaus.

d. An example schematic showing what happens to such a synapse when the stimulus frequency is increased by a factor of five and then by another factor of five.

e. For a small subset of synapses steady-state synaptic strength is frequency invariant and 10 Hz and 100 Hz plateau at the same synaptic strength.

f. Steady-state synaptic strength (PSCSS) is the same for a broad range of stimulus frequencies. This is thought to be achieved by having transmission mediated by 2 pools of vesicles. One pool is very effective for low frequency stimulation but it depletes at high frequencies. The second pool has a very low initial PR but facilitates in a frequency dependent manner to overcome frequency dependent depletion. Facilitation is Syt7 dependent and in Syt7 KOs transmission exhibits the frequency dependence of typical depressing synapses.

g. Such a synapse provide linear charge transfer.

h. Frequency invariant synapse are excellent at conveying rate codes as illustrated in a schematic for increases in stimulus frequencies.

i. Model of the response of a synapse from a Syt7 KO animal to 100 Hz stimulation with release mediated by 2 pools of vesicles with different properties. Steady-state transmission at the synapse is frequency dependent.

j. Same as i but for a WT animal in which Syt7-dependent facilitation enhances release from pool 2 during repetitive stimulation. Steady-state transmission at this synapse is frequency independent.

The properties of PC to DCN synapses, required for frequency invariance, were found to be inconsistent with a single pool of homogeneous vesicles. As such, it had been proposed that transmission must be mediated by two pools of vesicles. One pool with a high initial PR that depresses, and a second with a low initial PR that facilitates [46]. Syt7-dependent facilitation of the low PR component allows a frequency dependent increase in PR. This compensates for a frequency dependent increase in depletion of the RRP, resulting in frequency invariance (Fig. 2f, [••23]). When considering contributions from different vesicle pools during 100 Hz stimulation, the importance of facilitation becomes clear (Fig. 2i, j). The high PR pool depletes with high frequency activation so that, by the end of the train, transmission is mediated primarily by the low PR pool. In WT animals, facilitation increases PR counteracting depletion (Fig. 2j). In Syt7 KO animals, facilitation is absent, and, consequently, depletion of the pools dictates transmission (Fig. 2i). This shows how facilitation alone counteracts depletion to produce frequency invariance at PC to DCN and vestibular synapses. Nevertheless, at the MLI to PC synapse, Syt7-dependent regulation of facilitation and replenishment have both been implicated in frequency invariance [•20].

The widespread expression of Syt7 in the brain raises the possibility that Syt7-dependent frequency invariant synapses may be more prevalent than is currently appreciated.

Suppressing spontaneous vesicle fusion

Recent studies suggest that Syt7 is similar to fast Syt isoforms in its ability to suppress (clamp) spontaneous vesicle fusion. At the calyx of Held, miniature EPSC (mEPSC) frequency is elevated 8-fold in Syt2 KO mice, which is consistent with the described role of fast Syts in clamping spontaneous vesicle fusion. Although mEPSC frequency is not significantly elevated in Syt7 KO mice (relative to control), there is a larger increase in mEPSC frequency in Syt2/7 double KO mice (> 20-fold) than in Syt2 single KO mice [•19]. This suggests that at the calyx of Held, Syt7 suppresses spontaneous vesicle fusion in the absence of Syt2.

It appears that in some circumstances Syt7 can also suppress spontaneous vesicle fusion in WT animals. In regions of the IO where inhibitory synapses lack fast Syt isoforms, mIPSC frequency is low in WT animals and is elevated ~10-fold in Syt7 KO animals [•30]. These findings suggest that Syt7 strongly suppresses spontaneous vesicle fusion in WT animals at synapses lacking fast Syt isoforms.

Several molecular mechanisms have been advanced for Syt1 clamping. Fusion may be inhibited directly by locking the SNARE complex in a tripartite interface of the C2B domain together with Complexin [47]. Steric hindrance may also play a role, either by forcing the SNARE C-terminals to point away from the lipid membrane [48], or with ring oligomers of C2 domains keeping opposing membranes apart [49]. The latter hypothesis is also supported by the observation that disruption of oligomerization, through mutating the Syt1 C2B domain, increases constitutive fusion in PC12 cells [50]. Further studies are needed to determine whether Syt7 uses these mechanisms to clamp vesicle fusion.

Non-neuronal regulation of exocytosis

Recent findings have advanced our understanding of Syt7 in non-neuronal cells. In chromaffin cells, Syt7 and Syt1 trigger rapid and slow granule exocytosis, respectively [51]. Syt7 has been shown to be themain granule fusion sensor when calcium signals are small, consistent with its high calcium affinity [11]. It was also shown that fusion mediated by Syt1 and Syt7 tended to occur at different fusion sites, and that different types of calcium channels differentially contribute to Syt1 and Syt7-mediated fusion. Together, these findings reinforce the view that Syt7 is present on a specialized population of granules, comprising a distinct pool from Syt1 regulated granules.

Syt7 is also implicated as a major Ca2+-sensor in promoting insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells [52]. Recently, Syt4, a Ca2+-insensitive isoform, was found to interact with Syt7 to attenuate Syt7-mediated exocytosis, thereby increasing the threshold for glucose-stimulated insulin release [•53]. This observation is reminiscent of the finding that Syt4 can form hetero-oligomers with Syt1, which decreases neurotransmitter release by preventing the calcium-triggered insertion of Syt1 into the plasma membrane [54]. The finding that Syt4 can also prevent Syt7-dependent release raises the possibility that association between different Syt isoforms might provide a general means of regulating Syt-dependent signaling.

Disease

Recent studies have implicated Syt7 in several different disease mechanisms. The absence of presenilin, a protein long implicated in Alzheimer’s disease [55,56], has been found to decrease Syt7 levels and alter synaptic transmission [•57]. A role for Syt7 in mediating lysosome exocytosis for plasma membrane repair [58–60] has been implicated in treatment of muscular dystrophies with halofuginone, an inhibitor of the TGFβ/Smad3-signaling pathway. In the presence of halofuginone, Syt7 compensates for disruption of dysferlin, the default mediator of membrane repair in muscle cells [61]. Finally, Syt7 also promotes proliferation in several different cancer cell lines [62–65].

Regulation of Syt7’s functional diversity

As discussed in the previous paragraphs, Syt7 is a highly multifunctional protein, influencing synaptic transmission through many separate processes, such as AR and facilitation (Table 1). Many factors could contribute to this diversity, including: external calcium levels, temperature, initial PR, residual calcium signals, local calcium signals, different Syt7 isoforms, the localization of Syts, the presence of fast calcium sensitive Syts, the contribution of multiple vesicle pools with different properties, the presence of calcium-insensitive Syts and the levels of Syt7 present in the terminals.

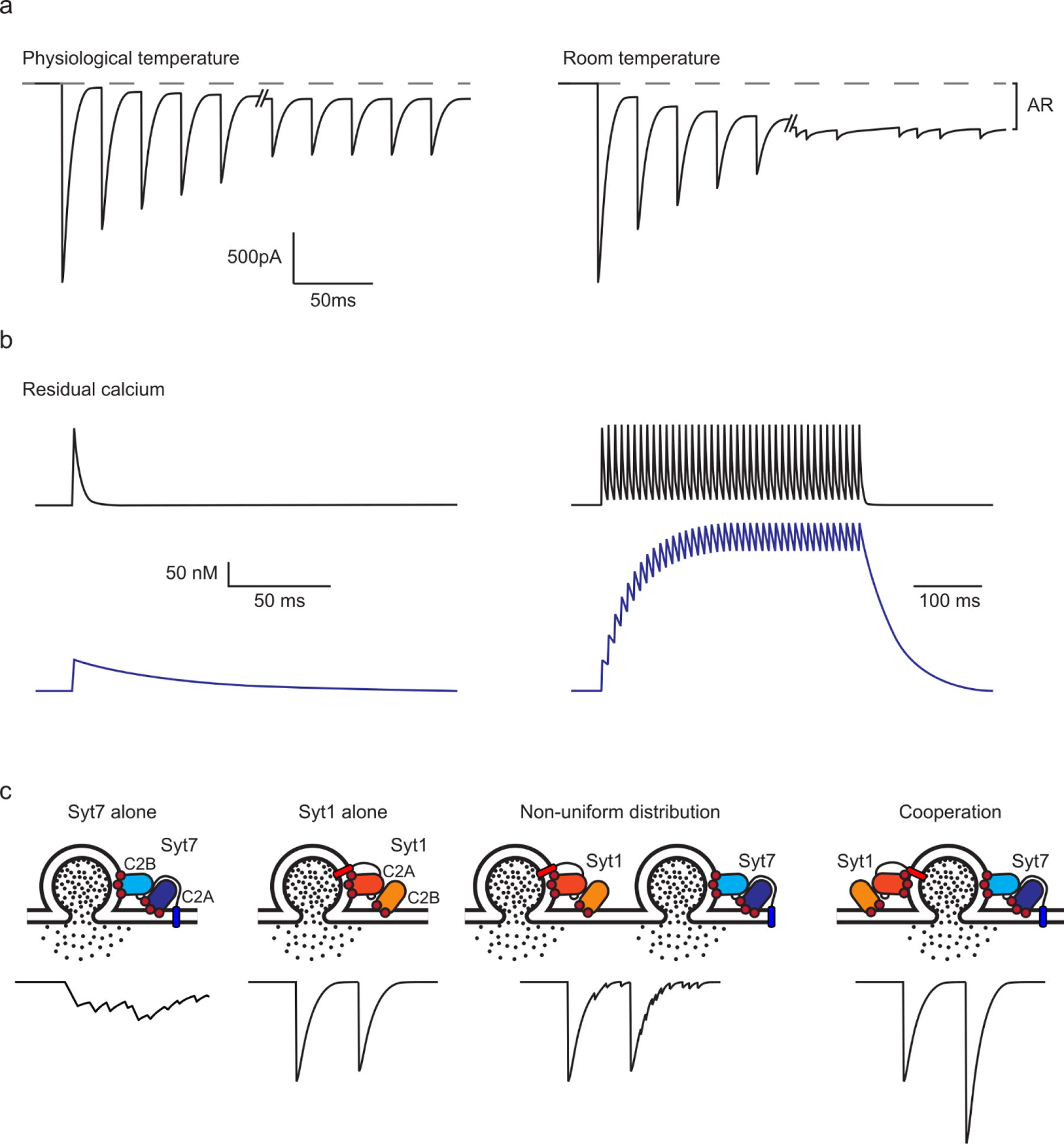

External calcium levels and temperature are controlled by the experimenter, and a departure from physiological conditions can artificially alter the relative contributions of Syt7 to AR and facilitation. At elevated temperatures, sustained high frequency stimulation reliably evokes synchronous release, but at room temperature release becomes desynchronized as a result of the impaired ability of Syt1 to suppress AR (Fig. 3a, [•27]). Elevated external calcium levels (above physiological levels) can increase the initial PR, thereby promoting depletion that can decrease or even mask facilitation. In addition, it will increase the size of the residual calcium signals that can promote AR. Typical departures from physiological conditions (decreased temperature and elevated external calcium) will artificially accentuate the contribution of AR and decrease the extent of facilitation.

Figure 3. Factors that can influence the role of Syt7 in synaptic transmission.

a. The effect of temperature on the properties of transmission. Figure inspired by [•27].

b. Example of different types of residual presynaptic calcium signaling that can influence the activation of Syt7. Large amplitude, short-lived signals in black; small amplitude, long-lived signals in blue.

c. Schematics showing the arrangement of Syt7 and Syt1 C2 domains controlling vesicle fusion and the corresponding expected transmission. Syt1 is shown tethered to the vesicle. Syt7 is drawn tethered to the plasma membrane, in line with [7,8], though its subcellular location remains a subject of debate.

Presynaptic residual calcium signals are an important factor in controlling Syt7 activation. The amplitudes and time courses of residual calcium signals can vary greatly (Fig. 3b, [66–68]), and this could lead to differential contributions of Syt7 to AR and facilitation, because of the different calcium dependencies of these processes. If single stimuli evoke large residual calcium signals, then there is the potential to effectively activate Syt7 and produce facilitation or AR. However, if the calcium transients are short-lived, then there will not be a large enough buildup during sustained activation to activate Syt7. In contrast, during sustained activation, even a small residual calcium signal will build up substantially, provided it is long-lived. This would lead to a situation where Syt7 is not very effectively activated by single stimuli, but sustained stimulation would lead to a large buildup of residual calcium that could effectively activate Syt7 and produce AR and/or facilitation.

High levels of fast and calcium-insensitive Syts will suppress AR and could contribute to the lack of AR at many synapses [24–26,•30,•53,54]. The localization of Syt7 and fast Syts could also be an important factor (Fig. 3c). If release is only mediated by Syt7, then stimulation will produce AR, whereas if release is mediated only by Syt1 release will be synchronous and non-facilitating. When transmission is the summated response of multiple vesicles, there are two extreme cases to consider. If there is combined fusion of some vesicles that rely exclusively on Syt7, and others that rely solely on Syt1, then release should be a mixture of non-facilitating fast transmission and facilitating AR (Fig. 3c; Non-uniform distribution). Conversely, when the fusion of all vesicles relies on both Syt7 and Syt1, then AR should be small due to suppression by Syt1, and facilitation should be prominent (Fig. 3c; Cooperation). The relative sensitivity of AR and facilitation to Syt7 levels is not known, but it is another potential factor in determining Syt7’s effect on neurotransmitter release.

Concluding remarks

These are just some of the issues that could regulate the ability of Syt7 to evoke AR and produce facilitation, as well as to regulate other functions such as accelerating replenishment and suppressing spontaneous vesicle fusion. Many fundamental issues remain unclear regarding the mechanisms of Syt7 in transmission. For example, the ability of different Syt7 isoforms to contribute to different aspects of transmission is not known [7,8,69]. The location of Syt7 within a bouton, plasma membrane, vesicle or elsewhere, is not known [7–10,58,69,70]. Additional exploration of molecular mechanisms will provide insight into the diverse contributions of Syt7.

Highlights.

Syt7 is a Ca sensor for facilitation, asynchronous release, and replenishment

Facilitation by Syt7 can allow depressing synapses to be frequency invariant

Syt7 can suppress spontaneous vesicle fusion.

Ca, temperature, other Syts, and location influence Syt7’s effect on transmission

References

- 1.Sugita S, Shin O-H, Han W, Lao Y, Südhof TC: Synaptotagmins form a hierarchy of exocytotic Ca 2+ sensors with distinct Ca 2+ affinities. EMBO J 2002, 21:270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hui E, Bai J, Wang P, Sugimori M, Llinas RR, Chapman ER: Three distinct kinetic groupings of the synaptotagmin family: candidate sensors for rapid and delayed exocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102:5210–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C, Ullrich B, Zhang JZ, Anderson RG, Brose N, Südhof TC: Ca(2+)-dependent and -independent activities of neural and non-neural synaptotagmins. Nature 1995, 375:594–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geppert M, Goda Y, Hammer RE, Li C, Rosahl TW, Stevens CF, Südhof TC: Synaptotagmin I: a major Ca2+ sensor for transmitter release at a central synapse. Cell 1994, 79:717–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pang ZP, Sun J, Rizo J, Maximov A, Südhof TC: Genetic analysis of synaptotagmin 2 in spontaneous and Ca2+-triggered neurotransmitter release. EMBO J 2006, 25:2039–2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDougall DD, Lin Z, Chon NL, Jackman SL, Lin H, Knight JD, Anantharam A: The high-affinity calcium sensor synaptotagmin-7 serves multiple roles in regulated exocytosis. J Gen Physiol 2018, 150:783–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugita S, Han W, Butz S, Liu X, Fernández-Chacón R, Lao Y, Südhof TC: Synaptotagmin VII as a plasma membrane Ca(2+) sensor in exocytosis. Neuron 2001, 30:459–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Virmani T, Han W, Liu X, Sudhof TC, Kavalali ET: Synaptotagmin 7 splice variants differentially regulate synaptic vesicle recycling. EMBO J 2003, 22:5347–5357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda M, Kanno E, Satoh M, Saegusa C, Yamamoto A: Synaptotagmin VII is targeted to dense-core vesicles and regulates their Ca2+ -dependent exocytosis in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 2004, 279:52677–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang P, Chicka MC, Bhalla A, Richards DA, Chapman ER: Synaptotagmin VII Is Targeted to Secretory Organelles in PC12 Cells, Where It Functions as a High-Affinity Calcium Sensor. Mol Cell Biol 2005, 25:8693–8702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao TC, Santana Rodriguez Z, Bradberry MM, Ranski AH, Dahl PJ, Schmidtke MW, Jenkins PM, Axelrod D, Chapman ER, Giovannucci DR, et al. : Synaptotagmin isoforms confer distinct activation kinetics and dynamics to chromaffin cell granules. J Gen Physiol 2017, 149:763–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atluri PP, Regehr WG: Delayed Release of Neurotransmitter from Cerebellar Granule Cells. J Neurosci 1998, 18:8214–8227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wen H, Linhoff MW, McGinley MJ, Li G, Corson GM, Mandel G, Brehm P: Distinct roles for two synaptotagmin isoforms in synchronous and asynchronous transmitter release at zebrafish neuromuscular junction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107:13906–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bacaj T, Wu D, Yang X, Morishita W, Zhou P, Xu W, Malenka RC, Südhof TC: Synaptotagmin-1 and synaptotagmin-7 trigger synchronous and asynchronous phases of neurotransmitter release. Neuron 2013, 80:947–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackman SL, Turecek J, Belinsky JE, Regehr WG: The calcium sensor synaptotagmin 7 is required for synaptic facilitation. Nature 2016, 529:88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jackman SL, Regehr WG: The Mechanisms and Functions of Synaptic Facilitation. Neuron 2017, 94:447–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu H, Bai H, Hui E, Yang L, Evans CS, Wang Z, Kwon SE, Chapman ER: Synaptotagmin 7 functions as a Ca2+-sensor for synaptic vesicle replenishment. Elife 2014, 3:e01524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Volynski KE, Krishnakumar SS: Synergistic control of neurotransmitter release by different members of the synaptotagmin family. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2018, 51:154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.•.Luo F, Südhof TC: Synaptotagmin-7-Mediated Asynchronous Release Boosts High-Fidelity Synchronous Transmission at a Central Synapse. Neuron 2017, 94:826–839.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study examines the role of Syt7 in transmission at the mouse calyx of Held using Syt7 and Syt2 KOs and Syt2/7 double KOs. They find that the small facilitation revealed in low external calcium was unaffected in Syt7 KO mice. They found that mEPSC frequency was strongly elevated in Syt2/7 double KOs compared to Syt2 KO mice, suggesting that Syt7 can clamp spontaneous vesicle fusion. They did not resolve individual quantal events that led to AR, but instead used a basal synaptic current built during sustained stimulation as a measure of AR. They concluded that this basal current was in part (50%) produced by Syt7-dependent AR. Experiments were done at 21–23 °C, so it will be interesting to extend these studies to more physiological temperatures. This study suggests that Syt7 plays a similar role in promoting AR during trains at the mouse calyx of Held, as previously shown at the zebrafish neuromuscular junction [13].

- 20.•.Chen C, Satterfield R, Young SM, Jonas P: Triple Function of Synaptotagmin 7 Ensures Efficiency of High-Frequency Transmission at Central GABAergic Synapses. Cell Rep 2017, 21:2082–2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Studies of the molecular layer interneuron to Purkinje cell (MLI to PC) synapses revealed that in Syt7 KO mice facilitation is eliminated, extremely low rates of AR observed during 20 Hz trains are significantly reduced, and based on cumulative EPSCs during trains they conclude that replenishment rates are reduced. They conclude that Syt7 has three functions at the same synapse.

- 21.Deng S, Li J, He Q, Zhang X, Zhu J, Li L, Mi Z, Yang X, Jiang M, Dong Q, et al. : Regulation of Recurrent Inhibition by Asynchronous Glutamate Release in Neocortex. Neuron 2020, 105:522–533.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.•.Turecek J, Regehr WG: Synaptotagmin 7 Mediates Both Facilitation and Asynchronous Release at Granule Cell Synapses. J Neurosci 2018, 38:3240–3251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; At synapses made by cerebellar granule cells, elevated presynaptic activity evokes both AR and synaptic facilitation. Syt7 contributes to both of these phenomena, even though AR is more steeply dependent upon calcium and shorter-lived than facilitation. Small, short-lived calcium-dependent components of AR and facilitation are present in Syt7 KO mice, indicating that additional mechanisms can contribute to both AR and facilitation at granule cell synapses.

- 23.••.Turecek J, Jackman SL, Regehr WG: Synaptotagmin 7 confers frequency invariance onto specialized depressing synapses. Nature 2017, 551:503–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This paper examines the role of Syt7 in transmission at the PC to DCN synapse. During development, PC to DCN synapses transform from typical frequency-dependent depressing synapses to frequency-invariant synapses. As this transformation occurs, Syt7 levels increase from very low levels in young animals to high levels in adults. It was found that in adults, frequency invariance was lost in Syt7 KO animals. Syt7-dependent facilitation of synaptic transmission was apparent in low calcium, and could be unmasked in physiological calcium. As had been shown previously, in WT animals the properties of this synapses cannot be explained by having a single pool of vesicles with uniform properties [46]. Instead, during high frequency stimulation release is mediated by a pool with a low PR that undergoes Syt7-dependent facilitation. The frequency dependence of Syt7-induced facilitation allows it to offset frequency dependent depression, which leads to a frequency-invariant synapse. Extending these studies to vestibular synapses suggested that this could be a general mechanism for a frequency-invariant synapse.

- 24.Littleton JT, Stern M, Perin M, Bellen HJ: Calcium dependence of neurotransmitter release and rate of spontaneous vesicle fusions are altered in Drosophila synaptotagmin mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91:10888–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishiki T, Augustine GJ: Dual roles of the C2B domain of synaptotagmin I in synchronizing Ca2+-dependent neurotransmitter release. J Neurosci 2004, 24:8542–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kochubey O, Schneggenburger R: Synaptotagmin increases the dynamic range of synapses by driving Ca2+-evoked release and by clamping a near-linear remaining Ca2+ sensor. Neuron 2011, 69:736–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.•.Huson V, van Boven MA, Stuefer A, Verhage M, Cornelisse LN: Synaptotagmin-1 enables frequency coding by suppressing asynchronous release in a temperature dependent manner. Sci Rep 2019, 9:11341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Here the effect of recording temperature on the ability of Syt1 to maintain synchronous release was examined. The authors performed voltage clamp recordings at 22°C or 32°C in hippocampal autaptic cultures lacking Syt1, or expressing a Syt1 mutant where release inhibition was impaired. Syt1’s inhibition of AR was found to be specifically impaired at 22°C, compared with 32°C. While this did not affect synchronous release of the first evoked EPSC, reduced synchronous release and increased asynchronous release were observed during high-frequency trains. This finding highlights the importance of recording temperatures on the extent of AR in synaptic transmission.

- 28.Otsu Y, Shahrezaei V, Li B, Raymond LA, Delaney KR, Murphy TH: Competition between phasic and asynchronous release for recovered synaptic vesicles at developing hippocampal autaptic synapses. J Neurosci 2004, 24:420–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagler DJ, Goda Y: Properties of synchronous and asynchronous release during pulse train depression in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol 2001, 85:2324–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.•.Turecek J, Regehr WG: Neuronal Regulation of Fast Synaptotagmin Isoforms Controls the Relative Contributions of Synchronous and Asynchronous Release. Neuron 2019, 101:938–949.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Some DCN to IO synapses are exclusively asynchronous. This study examined the mechanism responsible for this unusual synaptic transmission. Immunohistochemistry revealed that fast synaptotagmin isoforms (Syt1 and Syt2) were absent at asynchronous inhibitory synapses in the IO. They show that viral expression of Syt1 transforms these synapses into rapid synapses that lack asynchronous release. Unexpectedly, in Syt7 KO mice AR was still present, but with much slower kinetics. The main conclusions are that AR is prominent at DCN to IO synapses, which Syt7 plays a role in. However, an additional calcium sensor is present that can mediate AR, although with slower kinetics than AR mediated by Syt7. The identity of this sensor is not known.

- 31.Weber JP, Toft-Bertelsen TL, Mohrmann R, Delgado-Martinez I, Sørensen JB: Synaptotagmin-7 Is an Asynchronous Calcium Sensor for Synaptic Transmission in Neurons Expressing SNAP-23. PLoS One 2014, 9:e114033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuttle MF, Tsujimoto T, Forsythe ID, Takahashi T: Facilitation of the presynaptic calcium current at an auditory synapse in rat brainstem. J Physiol 1998, 512:723–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borst JGG, Sakmann B: Facilitation of presynaptic calcium currents in the rat brainstem. J Physiol 1998, 513:149–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller M, Felmy F, Schneggenburger R: A limited contribution of Ca 2+ current facilitation to paired-pulse facilitation of transmitter release at the rat calyx of Held. J Physiol 2008, 586:5503–5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thanawala MS, Regehr WG: Determining synaptic parameters using high-frequency activation. J Neurosci Methods 2016, 264:136–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; They examine different methods of determining synaptic parameters such as replenishment rate, the PR and the size of the readily releasable pool. They conclude that for many experimental conditions it can be exceedingly difficult to determine which of these synaptic parameters is responsible for a change in the cumulative synaptic current during train stimulation. This is particularly true if release cannot be described by a single pool of vesicles with uniform release and replenishment properties. For example, as appears to be the case for the PC to DCN synapse, if the PR is low, or if the stimulus frequency and the replenishment rate are high. As a result it may be premature to conclude that replenishment is responsible for alterations in cumulative synaptic currents arising from reducing or eliminating Syt7.

- 36.Neher E: Merits and Limitations of Vesicle Pool Models in View of Heterogeneous Populations of Synaptic Vesicles. Neuron 2015, 87:1131–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durán E, Montes MÁ, Jemal I, Satterfield R, Young S, Álvarez de Toledo G: Synaptotagmin-7 controls the size of the reserve and resting pools of synaptic vesicles in hippocampal neurons. Cell Calcium 2018, 74:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bacaj T, Wu D, Burré J, Malenka RC, Liu X, Südhof TC: Synaptotagmin-1 and −7 Are Redundantly Essential for Maintaining the Capacity of the Readily-Releasable Pool of Synaptic Vesicles. PLOS Biol 2015, 13:e1002267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicholson-Tomishima K, Ryan TA: Kinetic efficiency of endocytosis at mammalian CNS synapses requires synaptotagmin I. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2004, 101:16648–16652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poskanzer KE, Marek KW, Sweeney ST, Davis GW: Synaptotagmin I is necessary for compensatory synaptic vesicle endocytosis in vivo. Nature 2003, 426:559–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.von Poser C, Zhang JZ, Mineo C, Ding W, Ying Y, Sudhof TC, Anderson RGW: Synaptotagmin regulation of coated pit assembly. J Biol Chem 2000, 275:30916–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li YC, Chanaday NL, Xu W, Kavalali ET: Synaptotagmin-1- and Synaptotagmin-7-Dependent Fusion Mechanisms Target Synaptic Vesicles to Kinetically Distinct Endocytic Pathways. Neuron 2017, 93:616–631.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abbott LF, Varela JA, Sen K, Nelson SB: Synaptic depression and cortical gain control. Science 1997, 275:220–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bagnall MW, McElvain LE, Faulstich M, du Lac S: Frequency-independent synaptic transmission supports a linear vestibular behavior. Neuron 2008, 60:343–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Person AL, Raman IM: Purkinje neuron synchrony elicits time-locked spiking in the cerebellar nuclei. Nature 2011, 481:502–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turecek J, Jackman SL, Regehr WG: Synaptic Specializations Support Frequency-Independent Purkinje Cell Output from the Cerebellar Cortex. Cell Rep 2016, 17:3256–3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou Q, Zhou P, Wang AL, Wu D, Zhao M, Südhof TC, Brunger AT: The primed SNARE-complexin-synaptotagmin complex for neuronal exocytosis. Nature 2017, 548:420–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grushin K, Wang J, Coleman J, Rothman JE, Sindelar CV, Krishnakumar SS: Structural basis for the clamping and Ca2+ activation of SNARE-mediated fusion by synaptotagmin. Nat Commun 2019, 10:2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothman JE, Krishnakumar SS, Grushin K, Pincet F: Hypothesis - buttressed rings assemble, clamp, and release SNAREpins for synaptic transmission. FEBS Lett 2017, 591:3459–3480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bello OD, Jouannot O, Chaudhuri A, Stroeva E, Coleman J, Volynski KE, Rothman JE, Krishnakumar SS: Synaptotagmin oligomerization is essential for calcium control of regulated exocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115:E7624–E7631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schonn J-S, Maximov A, Lao Y, Südhof TC, Sørensen JB: Synaptotagmin-1 and −7 are functionally overlapping Ca2+ sensors for exocytosis in adrenal chromaffin cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105:3998–4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gustavsson N, Lao Y, Maximov A, Chuang J-C, Kostromina E, Repa JJ, Li C, Radda GK, Südhof TC, Han W: Impaired insulin secretion and glucose intolerance in synaptotagmin-7 null mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105:3992–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.•.Huang C, Walker EM, Dadi PK, Hu R, Xu Y, Zhang W, Sanavia T, Mun J, Liu J, Nair GG, et al. : Synaptotagmin 4 Regulates Pancreatic β Cell Maturation by Modulating the Ca2+ Sensitivity of Insulin Secretion Vesicles. Dev Cell 2018, 45:347–361.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study examined the mechanism behind tuning of insulin secretion in response to glucose, during the maturation of β cells. They identify Syt4 as a key protein in the maturation process, reducing insulin secretion at low glucose levels. Interestingly, Syt4 seems to do so through an interaction with Syt7, the main calcium-sensor for insulin secretion. This is another example of different Syts regulating each other’s activation to tune exocytosis (see also [•30]) suggesting this is a general mechanism.

- 54.Littleton JT, Serano TL, Rubin GM, Ganetzky B, Chapman ER: Synaptic function modulated by changes in the ratio of synaptotagmin I and IV. Nature 1999, 400:757–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sherrington R, Rogaev EI, Liang Y, Rogaeva EA, Levesque G, Ikeda M, Chi H, Lin C, Li G, Holman K, et al. : Cloning of a gene bearing missense mutations in early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 1995, 375:754–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mullan M, Crawford F, Axelman K, Houlden H, Lilius L, Winblad B, Lannfelt L: A pathogenic mutation for probable Alzheimer’s disease in the APP gene at the N-terminus of beta-amyloid. Nat Genet 1992, 1:345–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.•.Barthet G, Jordà-Siquier T, Rumi-Masante J, Bernadou F, Müller U, Mulle C: Presenilin-mediated cleavage of APP regulates synaptotagmin-7 and presynaptic plasticity. Nat Commun 2018, 9:4780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; The protease presenilin and its main substrate amyloid precursor protein (APP) are two main loci for mutations leading to early onset Alzheimer disease. This study reveals that presenilin together with APP regulates Syt7 expression. Specifically, removal of presenilin also reduced presynaptic levels of Syt7. Examining synaptic transmission in MF-CA3 synapses lacking presenilin presynaptically, the authors found impairments similar to those observed in Syt7 KO. This suggests that disruption of Syt7’s influence on synaptic transmission may be part of Alzheimer disease pathology.

- 58.Martinez I, Chakrabarti S, Hellevik T, Morehead J, Fowler K, Andrews NW: Synaptotagmin VII regulates Ca(2+)-dependent exocytosis of lysosomes in fibroblasts. J Cell Biol 2000, 148:1141–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reddy A, Caler EV, Andrews NW: Plasma Membrane Repair Is Mediated by Ca2+-Regulated Exocytosis of Lysosomes. Cell 2001, 106:157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chakrabarti S, Kobayashi KS, Flavell R a, Marks CB, Miyake K, Liston DR, Fowler KT, Gorelick FS, Andrews NW: Impaired membrane resealing and autoimmune myositis in synaptotagmin VII-deficient mice. J Cell Biol 2003, 162:543–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barzilai-Tutsch H, Dewulf M, Lamaze C, Butler Browne G, Pines M, Halevy O: A promotive effect for halofuginone on membrane repair and synaptotagmin-7 levels in muscle cells of dysferlin-null mice. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27:2817–2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kanda M, Tanaka H, Shimizu D, Miwa T, Umeda S, Tanaka C, Kobayashi D, Hattori N, Suenaga M, Hayashi M, et al. : SYT7 acts as a driver of hepatic metastasis formation of gastric cancer cells. Oncogene 2018, 37:5355–5366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang K, Xiao H, Zhang J, Zhu D: Synaptotagmin7 Is Overexpressed In Colorectal Cancer And Regulates Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation. J Cancer 2018, 9:2349–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu X, Li C, Yang Y, Liu X, Li R, Zhang M, Yin Y, Qu Y: Synaptotagmin 7 in twist-related protein 1-mediated epithelial - Mesenchymal transition of non-small cell lung cancer. EBioMedicine 2019, 46:42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fei Z, Gao W, Xie R, Feng G, Chen X, Jiang Y: Synaptotagmin-7, a binding protein of P53, inhibits the senescence and promotes the tumorigenicity of lung cancer cells. Biosci Rep 2019, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Atluri PP, Regehr WG: Determinants of the time course of facilitation at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci 1996, 16:5661–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scott R, Rusakov DA: Main Determinants of Presynaptic Ca2+ Dynamics at Individual Mossy Fiber-CA3 Pyramidal Cell Synapses. J Neurosci 2006, 26:7071–7081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brenowitz SD, Regehr WG: Reliability and Heterogeneity of Calcium Signaling at Single Presynaptic Boutons of Cerebellar Granule Cells. J Neurosci 2007, 27:7888–7898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fukuda M, Ogata Y, Saegusa C, Kanno E, Mikoshiba K: Alternative splicing isoforms of synaptotagmin VII in the mouse, rat and human. Biochem J 2002, 365:173–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rao TC, Passmore DR, Peleman AR, Das M, Chapman ER, Anantharam A: Distinct fusion properties of synaptotagmin-1 and synaptotagmin-7 bearing dense core granules. Mol Biol Cell 2014, 25:2416–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]