Abstract

Audiovisual recordings are under-utilized for capturing interactions in inpatient settings. Standardized procedures and methods improve observation and conclusion validity drawn from audiovisual data. This article provides specific approaches for collecting, standardizing, and maintaining audiovisual data based on a study of parent–nurse communication and child and family outcomes. Data were collected using audio and video recorders at defined time points simplifying its collection. Data were downloaded, edited for size and privacy, and securely stored, then transcribed, and subsequently reviewed to ensure accuracy. Positive working relationships with families and nurses facilitated successful study recruitment, data collection, and transcript cleaning. Barriers to recruitment and data collection, such as privacy concerns and technical issues, were successfully overcome. When carefully coordinated and obtained, audiovisual recordings are a rich source of research data. Thoughtful protocol design for the successful capture, storage, and use of recordings enables researchers to take quick action to preserve data integrity when unexpected situations arise.

Keywords: audiovisual recording, parent-nurse communication, pediatrics, family nursing practice

Audiovisual recording is an under-utilized research tool in clinical inpatient settings, particularly in pediatrics (Golembiewski et al., 2023).

The study described herein provides recommendations for collecting audiovisual research data that captures the patient and family-caregiver experience as well as their interactions with nursing staff. These recommendations span study recruitment and coordination, as well as data collection, storage, cleaning, and transcription. Future studies seeking to utilize audiovisual recording in a similar context will benefit greatly by taking a structured and well-planned approach that can accommodate unexpected scenarios.

Prior Use and Significance of Audiovisual Recording

Audiovisual recordings have been utilized in research studies in other disciplines such as music, history, education, and the social sciences (Duan et al., 2019; Maltese et al., 2016; Martin et al., 2021; Pallotti et al., 2020). In health care settings, audiovisual recordings are often used for training purposes or for observing staff workflow (DiGioia et al., 2012; Edman et al., 2022; MacLean et al., 2019; Van Gelderen et al., 2016), or more recently, to conduct research utilizing video or telehealth platforms with families (Bogulski et al., in press; Holuszko et al., 2022; Lobe et al., 2020). Often, audio-only recordings or observations are used to study interactions between nurses and families, particularly in pediatrics (Choe et al., 2021; Walter et al., 2019). Less frequently, audiovisual recordings have been used to document nurse communication with patients (Happ et al., 2014; Nilsen et al., 2013). However, there is great potential in audiovisual data to document and explain patient and family care experiences beyond simply observing participants, particularly in qualitative studies such as those employing focus groups (to differentiate between speakers) and ethnography (to capture situational or environmental elements) (Martínez-Guiu et al., 2022; Sarabia-Cobo et al., 2020). This form of data is especially useful as it can capture both verbal and nonverbal communication and contextual factors essential for understanding family nursing practice such as assessment of caregiver comprehension through observation, demonstration of skills, nonverbal affirmations and reassurances, and eye contact (Giambra et al., 2018; Grant & Luxford, 2009; Zhou et al., 2021). The recordings can also be examined an infinite number of times rather than relying solely on real-time observation that is subject to the bias of the researcher capturing the data (Haidet et al., 2009). However, identifying specific instances of relevant concepts or findings among audiovisual data rather than just the transcripts created from them can be cumbersome and time-consuming (Subramanian et al., 2021). Standardized data capture procedures and analysis methods may improve the validity of observations and conclusions based on audiovisual data. Data capturing verbal and nonverbal parent–nurse communication is scarce (Giambra et al., 2018; Lenzen et al., 2018; Lipstein et al., 2014). In addition, there is a lack of specific guidance on successfully capturing, storing, and modifying audiovisual data (Spiers et al., 2000).

Study Context and Purpose

In this article, we describe the unique use of audiovisual recordings to collect data on family–nurse communication in a pediatric hospital setting for a quantitative study. As an under-utilized method, we review our research method, challenges, and successes with this method of data collection.

Parents have expert knowledge about the care they and others provide at home for children with complex conditions such as long-term ventilator dependence (LTVD). When the child is hospitalized, parents communicate their expert knowledge to the nurses caring for them, and the nurses communicate with parents their own expertise about the child’s medical care and changes in that care. Hospital stays during which nurses provide care for the child may result in modifications to the child’s care routine, requiring additional learning and adaptations to home care on the part of the family. We sought to explain which specific communication behaviors, enacted by parents, nurses, or both, were associated with improved ability to manage the child’s care, family and child quality of life, and child clinical outcomes such as respiratory infections and health care utilization. The observational, descriptive, quantitative study portrayed here used audiovisual recordings to capture parent–nurse communication about the care of the child with LTVD hospitalized on a unit dedicated to providing care for such children at a free-standing, Midwestern, quaternary children’s hospital. The aims were to identify the observed communication behaviors and their association with family management of the child’s care and clinical outcomes.

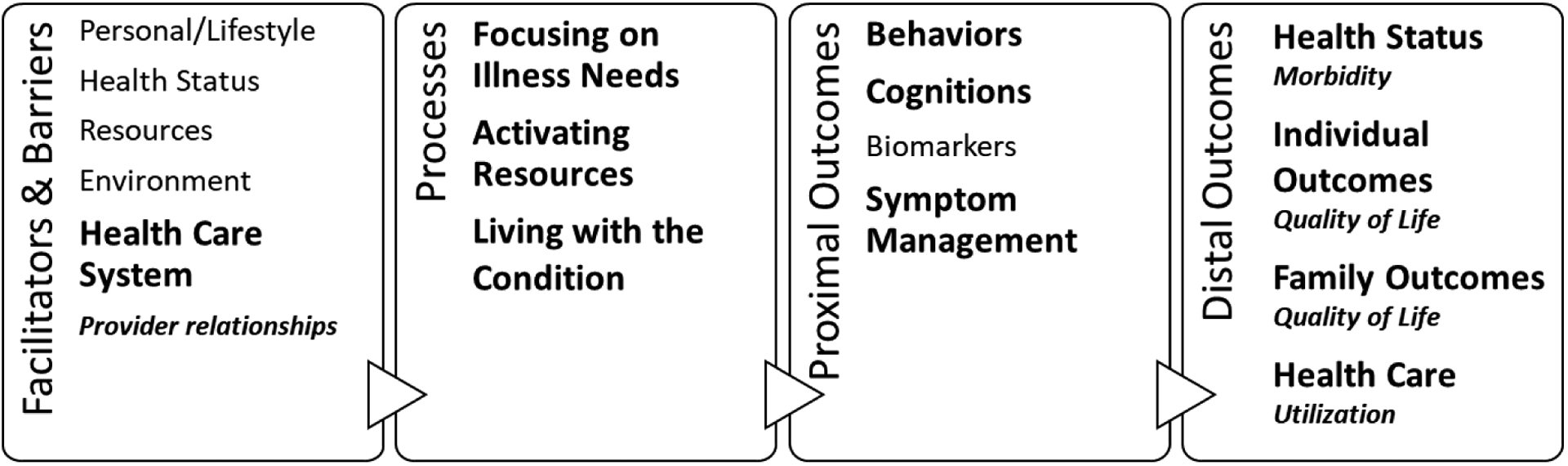

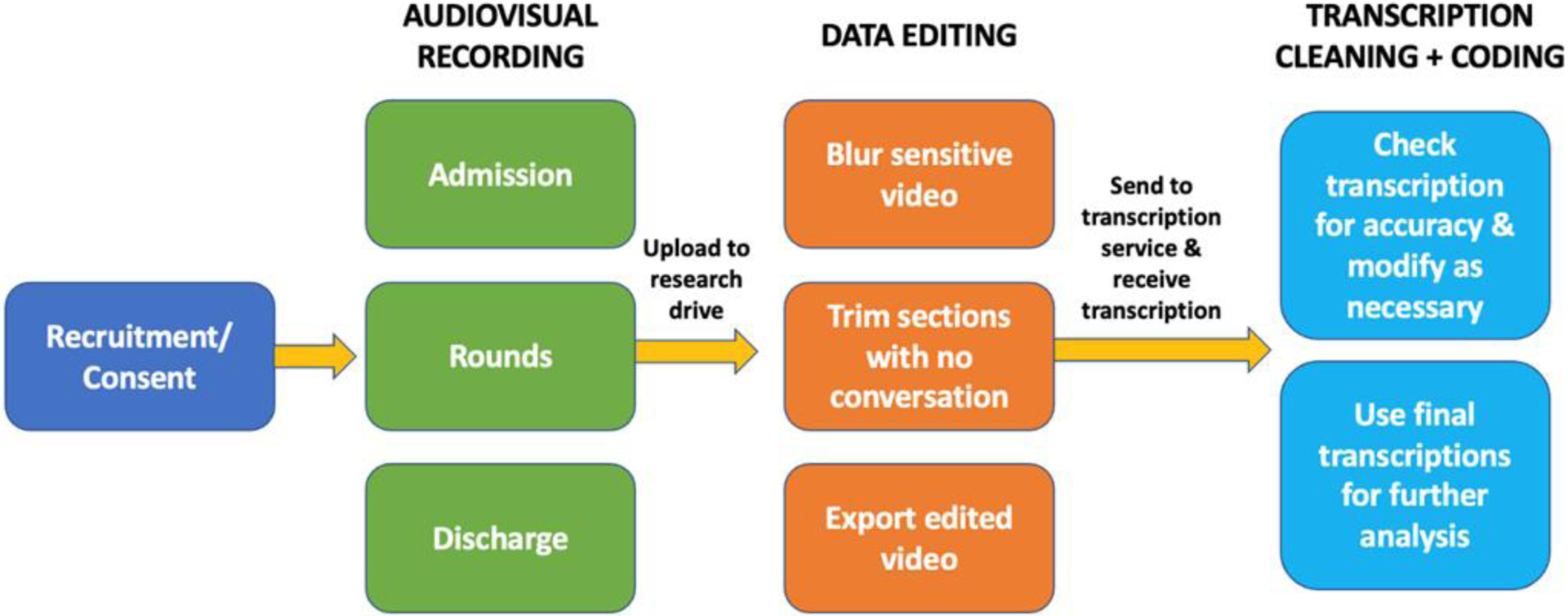

The study was based on both the Theory of Shared Communication (Giambra et al., 2017) and the Self- and Family Management Framework (Grey et al., 2015). The Theory of Shared Communication illustrates the process and communication behaviors parents and nurses use to communicate about and reach mutual understanding of the care of the child including asking, listening, explaining, verbalizing understanding, advocating, and role negotiation (Giambra et al., 2017). The Self- and Family Management Framework (SFMF) posits that personal, health status, resources, environmental, and health care system factors, such as relationships with providers, are facilitators/barriers to self- and family management of chronic illness. The links between the SFMF and the present study are highlighted in Figure 1. Briefly, our methods included recording parent–nurse communication during admission, after rounds once each day and at discharge. The transcripts of the recordings were then coded for the number of communication behaviors of interest enacted. Descriptive and inferential statistics were used to demonstrate associations with the outcomes collected through surveys upon enrollment, at discharge, and 1 week and 1 month after discharge. (see Figure 2) Details regarding the present study are provided in the following sections to highlight our experiences, barriers encountered, and solutions devised to overcome them, to inform future research in which audiovisual data are collected and analyzed.

Figure 1.

Links Between the Self- and Family-Management Framework and the Current Study.

Adapted from the Revised Self- and Family Management Framework (Grey, et al., 2015)

Figure 2.

Flow Chart Demonstrating Study Procedures Discussed in This Paper

Procedures

Recruitment

Communication is a social and relational process that occurs between at least two people. Therefore, to assess the association between parent–nurse communication and child and family outcomes, we enrolled both nurses and parents. Nurses who met inclusion criteria had completed unit orientation, were functioning independently, provided direct patient care, worked during 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. shifts and might care for the child of a study parent. Parents who met the inclusion criteria as the primary caregiver were English-speaking and self-identified as the provider of the most home care for children 2 to 17 years of age who had been LTVD dependent for at least 6 months and admitted to the study unit. We also recruited any other English-speaking parents or caregivers communicating with the child’s nurse during the child’s hospitalization as secondary caregivers.

Following Institutional Review Board approval in November 2018, we began actively recruiting nurses using emails, flyers, and staff meetings. Within 3 months, we recruited 20 nurses, enough to have 1 to 2 enrolled nurses for each day shift. Overall, 67 nurses were approached and 48 enrolled (72%). Parents were recruited between February 2019 and October 2021. Parents were recruited in the emergency department, perioperative area, in the child’s room as they arrived on the study unit, or prior to rounds the morning after an evening/overnight admission. Children aged 7 through 17 years of age were asked for assent if they had the communicative and developmental ability to do so. If a child meeting the criteria declined to give assent, the family was not enrolled. Families were able to enroll up to 4 times. A total of 135 unique families were approached and 100 enrolled (74%). Study staff obtained verbal consent to be recorded from providers, staff, family, and friends who happened to be in or entered the room during recording.

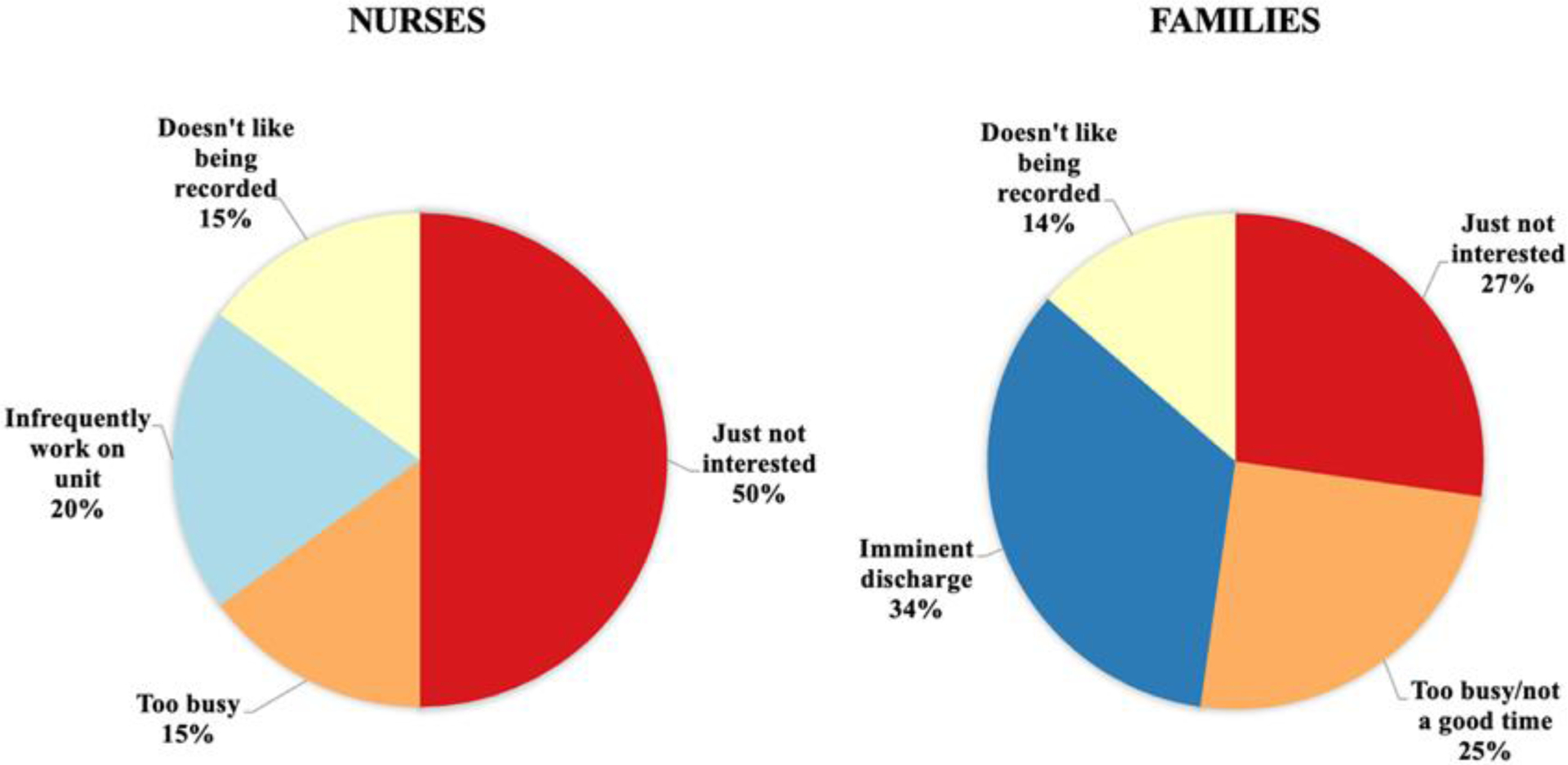

Recruitment was dynamic as nurses started on or left the unit throughout the study and parents were admitted from several locations necessitating a multifaceted approach. As the study progressed and the unit nursing staff evolved, we enrolled additional nurses to continue to have at least 1 to 2 enrolled nurses available each day. Although it was most efficient to recruit and enroll families as they arrived on the study unit, and then begin recording the admission conversations, this approach often seemed stressful for families and was more interruptive for the admitting nurse. Therefore, we sought to recruit and enroll families when they had more time to consider the study; preoperatively, while waiting for their child’s surgical procedure to finish or while awaiting transfer from the emergency department or intensive care unit (ICU) when possible. Only a few of the families and nurses reported declining participation due to feeling rushed. However, 14% to 15% of both families and nurses who declined did so due to dislike of being recorded (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Reasons Given by Eligible Participants for Declining Joining the Study.

Due to the busy nature of the study unit during the day shift, nonparticipants were frequently in or entering the room during recordings. We attempted to let people know a recording was in progress by posting a sign on the door and stopping people before they entered the room to explain the study and obtain verbal consent to be on the recording or other options, such as waiting until the recording was done, or being blurred. Verbal consent was given by nonparticipants for 388 of the 652 recordings captured, many with multiple nonparticipants. Those who did not provide consent represented a wide variety of professions (n = 14).

Data Collection

Audiovisual data collection occurred at three distinct time points: admission to the inpatient unit, once after rounds each day, and discharge from the unit. If a nurse enrolled in the study was assigned to an enrolled child/family at any of these time points, study staff attempted to collect data. The research team member collecting data verified the nursing assignments and ensured that the enrolled parent was present at the bedside. Study staff followed handwashing guidelines and wore appropriate personal protective equipment whenever entering the patient rooms. The camera (GoPro HERO7) and audio recorder (Sony IC Recorder) were placed at different locations in the patient’s room to capture the conversation from various angles with the intent of maximizing understanding of what was said when staff reviewed the recordings at a later time, and in case one device failed. The camera was often placed on top of a cabinet across the room from the child’s bed, providing a view of the patient, the parent/caregiver, the door to the inpatient room, and various medical devices and monitors. The audio recorder was then situated in another secure and suitable spot in the room. The devices were retrieved when either the nurse finished providing care or the parent left the room. Finally, parents and nurses were told upon enrollment that they could stop the recording devices themselves at any time if they wished due to the voluntary nature of participation.

Sightlines, noise, workflows, and safety all proved to be barriers to optimal recordings. Having the camera at the head of the bed initially seemed an ideal position, but this is also where the most noise making equipment (e.g., suction, oxygen, ventilator, pumps, lights) and staff/parent activity was found. To avoid loud ambient noise and the camera being in the way or potentially falling on the child, the opposite position, across the room, was chosen. However, the camera’s view was sometimes unavoidably obstructed if the inpatient room layout varied, or if medical equipment such as IV poles were blocking the line of sight. Study staff chose alternate positions on those cases, prioritizing capture of the parent and nurse over the patient, as easy identification of who was speaking at any given time streamlined the analysis process. In addition, while no participants stopped the recordings, one nurse and two parents each turned the camera away from the child during bathing, allowing audio data to still be captured. When placing recording devices and while waiting to retrieve them after data collection, study staff tried to be as unobtrusive as possible and sat outside of the patient room during recording.

Noise proved to be a consistent barrier to obtaining good quality recordings. The inpatient hospital room is rife with noise from the hum of the overbed light to the noise of suction canisters and ringing of multiple device alarms. The population of interest, children with LTVD, also contributed to the noise level through intermittent verbalizations, talking, singing, and ventilator noise. These children often required frequent suctioning and liked to listen to music and watch movies on a tablet or television, all of which added to the ambient noise in the room. Also, parents using cell phones and additional people in the room increased the chance for concurrent dialogue, which could obscure the conversation intended for capture.

The cameras we used had a variety of features that were easily accessible from the home screen of the device. On rare occasions, with a single touch study staff unintentionally activated an alternative recording mode such as slow motion or time lapse, both of which eliminated the audio component of the recording and thus resulted in data loss. The audio recorders also had different modes for recording. It was important to double check that each device was recording in the intended mode, before leaving the room. There were also unavoidable technical difficulties. For instance, a corrupt memory card, rather than overheating as first suspected, caused the camera to shut off unexpectedly during recording and had to be replaced. Also, a few times, the camera was knocked off the cabinet on which it was placed by a parent who had forgotten it was there. Fortunately, our cameras were enclosed in a protective case and were resilient; no data were lost in this way and the families returned quickly the camera to its place. The audio recorders were not as hardy and if dropped, the battery compartment occasionally opened. If the batteries fell out, the recording was lost. Moreover, of course, making sure the batteries were charged and the devices were in good working order before each use was good practice.

Several additional strategies were adopted throughout the course of the study to increase the likelihood of successful data capture. For instance, the study team consistently attended to their surroundings, both around the unit and on the patient video monitors to ensure a nurse–parent conversation was not missed; such data are most robust when captured in their entirety from hello to goodbye. Also, awareness of what isolation precautions were required for entering the specific patient’s room prior to the nurse entering allowed conversations to be captured more fully (i.e., data were not missed while donning personal protective equipment). In addition, study team members listened carefully to information families and nurses provided about changes in the child’s care that could potentially affect data collection such as impending procedures for the child or discharges.

Coordination

This study required significant coordination with the inpatient care team. The primary investigator met with the study unit’s nurse manager and medical team leads to inform them of the study and brainstorm ways to enhance cooperation and coordination among the various team members. The charge nurses on the unit were identified as knowledge brokers. Therefore, the nurse manager facilitated adding all the research team members to specific unit email groups; a weekly pulmonary team email describing potential planned admissions to the unit and the frequently used charge nurses’ group email which proved to be vital to the study’s success. The charge nurse email provided information such as unit census, pending and planned admissions, procedures, and discharges for the following shift. In this way, study staff were made aware of potential families to screen for recruitment and who might be available for data collection. In addition, each morning, a member of the study team called the charge nurse at a prescribed time before rounds, to (a) let them know which families we planned to collect data on that day and at what times, (b) verify whether enrolled nurses were caring for enrolled families, and (c) identify potential discharges and admissions from the emergency department, intensive care units, and postoperative area.

Rounds usually started before 9 a.m. for the primary medical team on the unit (Pulmonary) and at various times for other services. The study team tried to arrive well in advance of rounds. When more than one family was enrolled at the same time, data were collected sequentially using two sets of recording devices and in collaboration with each child’s nurse to optimize data capture. Study staff also discussed potential admission times with the assigned nurses, charge nurse, and unit coordinator to coordinate appropriate timing for efficient data collection. If an admission or discharge was planned for the afternoon, study staff left the unit after morning data collection and returned before the time predicted. Study staff discussed the timing for discharges with both the nurse and family and planned to arrive earlier than discharge was predicted to ensure data collection.

A reminder about the study was added to the template for the charge nurse email asking for the charge nurse to call the PI for any emergent admissions before 5 p.m., however the charge nurse rarely called. Therefore, study staff frequently checked the unit census on the electronic medical record (EMR) system looking for potential admissions. In addition, potential participants were screened based on the Pulmonary department’s registry of ventilator-dependent children and study staff notifications of their admission set up in the EMR which proved to be useful. Often the charge nurse was too busy to answer the pre-rounds morning call, and in those instances, we found the unit coordinator was usually able to provide the needed information.

Knowing when to be on the unit and ready to collect data was a challenge. Study staff made themselves well known on the inpatient unit so both providers and patient families were comfortable with their presence and to avoid missing data capture opportunities. Individual patient acuity often dictated the order in which patients were discussed leading to variation. Also, some of the children of enrolled families were admitted to different medical teams such as orthopedics or hospital medicine. Therefore, study staff arrived early and often had to wait up to an hour or more for rounds to be completed prior to data collection. Estimating the timing of transfers was also challenging. The charge nurse was one source for an estimate. Often, the study staff were able to use the EMR to estimate the timing of transfers from the post-anesthesia or ICU. Occasionally, the child’s ICU nurse or enrolled parent provided the best estimate of timing for transfers.

Data Storage and Editing

After the devices were collected from the patient’s room, the audio data were immediately downloaded to the study’s secure research drive. MP3 (audio) files were much smaller than MP4 (video) files and thus downloaded more quickly, especially when the researcher’s laptop was connected to hospital Wi-Fi, rather than an ethernet. Immediate download ensured that the data had been captured, and in the case of collecting data from multiple enrolled families the same day, that the data would not be over-ridden or confused with that of another participant. Both audio and video files were named using a prespecified combination of participant identification numbers to identify which participants were recorded while maintaining confidentiality, as well as the date and context (admission, rounds, discharge).

Once downloaded onto the research drive and properly named, all video files were edited with Wondershare Filmora software. This software was chosen because it could be housed on the user’s computer and did not require uploading the video to the web or a cloud, thus maintaining control over the confidentiality of the data. This software was particularly useful when considering privacy, as a blurring feature could be used to hide part or all of the screen and select portions of the audio could be distorted. For people who entered the room and did not provide consent to be recorded, or asked for their image to be blurred, or to protect patient privacy, the blurring tool was used to obscure faces or exposed body parts and voices were distorted by lowering the pitch substantially. The software also allowed the user to remove any selected portion of the video and insert captions. In the event that either the parent or nurse left the room and returned during recording, the intermittent period could be removed and marked with a caption such as “nurse leaves room.”

Video file size was one of the most challenging barriers encountered in this study. The video files were much larger than the audio files and generally took too long to successfully download over the available internet bandwidth on the inpatient unit. Therefore, they were downloaded in offices with an ethernet connection. Also, although the camera itself recorded videos in one segment, the computer onto which it was downloaded broke the recordings up into approximately 15-min segments. Each one of these segments could take up to 7 min to download while connected to hospital ethernet and up to 45 when on the Wi-Fi. If broken into multiple segments, “part #” was added to the file name for ease of rejoining during editing. Running the raw video through the file editing software reduced the file size by approximately 50%. Videos were also trimmed at their beginning and end, just before and after participants left the child’s room, to further reduce the file size. To conserve storage space on the research drive, the raw video data were transferred to two external hard drives (Seagate Backup Plus) and removed from the research drive once the edited versions were created. These hard drives were kept in separate locations to protect data in the event of fire or other physical damage. When study staff finished using the audio and edited video, they too were moved to the external drives. This process prevented the need for additional in-network drive space while making room for new participant data.

Data Transcription

Once raw video data were successfully edited, the primary investigator reviewed each video in its entirety and kept a log of all the instances of parent–nurse communication about the child’s care, using time marks from the recording. The log identified the pertinent portions of the recordings to be transcribed, based on the research questions. The edited recordings and corresponding log were sent in a batched data file using a secure web-based file sharing service (Box) to a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA)-compliant transcriptionist who transcribed and deidentified the data. To ensure the accuracy of the data extracted from the recordings, study staff then “cleaned” the transcripts. Cleaning entailed double-checking, and if necessary, editing the transcriptionist’s work while watching the file from which it was transcribed. The original, untouched versions of the transcript, a copy with Microsoft Word’s “Track Changes” feature enabled for easy viewing of edits, and a final “cleaned” copy that was used in analysis were all stored on a secure drive.

Transcription services are costly. While some recordings were only a few minutes long, others were over an hour in length. Therefore, only having the pertinent portions of the recording transcribed reduced overall costs. In addition, while it was ethically important to obtain verbal consent from nonparticipants who may have been captured on the recordings, their communication was excluded from transcription as much as was feasible, as it was not relevant to the research questions.

The transcriptionist only used the audio portion of the recordings; therefore, they were often unaware of who was actually speaking and generally labeled the speaker as woman or man. By viewing the video recording while cleaning the transcript, the research staff were able to more accurately identify the speakers by role (Mom, Dad, Nurse, child, etc.). This was especially beneficial when there were multiple people in the room and/or contributing to a given conversation. In addition, transcriptionists may not be familiar with clinical terms or colloquial expressions, making some words and phrases difficult to understand. Developing a rapport with the nurses and families also aided in accurate identification as it enabled the study staff to better understand patterns of speech and accents. Familiarity with the participants’ speech also enabled a more precise understanding of what was said, enhancing the accuracy of the cleaned data.

Viewing the video also allowed the research staff to add non-verbal communication to the transcripts. For example, a caregiver may answer a nurse’s question by pointing to something. Someone nodding, shaking their head, or grimacing acts as a response as well. A caregiver and nurse working together in silence, such as when bathing or positioning the child, adds context and additional meaning to the surrounding conversation. In cases where background noise is overpowering, observers may be able to corroborate their audio transcription by lip reading simple, short responses like “yes” or “no” in the video recording.

Discussion

Families and nurses alike declined participation in the research for various reasons (see Figure 3). Despite its usefulness for researchers, audiovisual data collection in and of itself may deter potential recruits from participating. Participants’ understanding of privacy protection practices in place for the study is critical (Broyles et al., 2008). For example, participants may worry that they will be penalized for expressing dissatisfaction with their child’s medical care if they are recorded. Likewise, nurses may worry their conversations with parents may be used in performance evaluations or have legal repercussions (Prictor et al., 2021; Themessl-Huber et al., 2008). In addition, ethical issues such as consent for recordings to be used for training or quality improvement activities or for future research presentations should be planned for, discussed with participants, and included in consent forms (Broyles et al., 2008; Iserson et al., 2019). National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded studies are now issued a Certificate of Confidentiality which prohibits identifiable information from being disclosed, an important point to discuss with potential participants (National Institute of Health, 2022). Assuring participants that such sensitive study data cannot and will not be released encourages them to speak more freely. Families were provided this information during recruitment for our study, and our enrollment was robust, albeit similar to other studies involving audiovisual recordings in a health care setting (Jepsen et al., 2022; Seuren et al., 2020). This may reflect the ubiquitous nature of recordings in current society and the increased use and acceptability of telehealth.

Some families and nurses declined participation, particularly if they perceived they were too busy. Unfortunately, busyness is a characteristic of an inpatient unit; different family members come and go and may have to balance a job or caring for other children with being at the bedside (Bruneau et al., 2021; Urbanosky et al., in press). Nurses may not wish to add study participation to their already busy schedules or infrequently work on the study unit (Roxburgh, 2006). Similarly, families who are expecting imminent discharge from the hospital and have limited time remaining on the unit may also decline participation. Finally, potential participants may opt not to join the study when they don’t value research or are simply not interested (Jacobson et al., 2008).

Developing a rapport with individual nurses and families is also beneficial to the progress of such a study as a whole (Gabbert et al., 2021; Yeager & Bauer-Wu, 2013). A stranger setting up a camera in their child’s room can feel intrusive or intimidating if not done with empathy; familiarity with both study staff members and the purpose of the research alleviates that discomfort. This may range from simply asking a nurse or parent how they and their child are doing, to educating oneself on a family’s specific cultural background. Awareness of religious practices or cultural factors that prohibit the use of electronics, or in some way impact the collection or use of such recordings, for example, shows families that study staff respect their needs (Kulkarni et al., 2014; Nevins, 2012; Vaarzon-Morel et al., 2021). Offering to suspend recording during a parent or child’s mental or physical crisis also demonstrates that the research team cares about and prioritizes their well-being. In addition, following infection control practices emphasizes respect for patient and family safety as well as that of the study team (Rathore et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2007). Families can also be reassured that video data can easily be blurred so that their child is hidden during baths, changing, procedures, or any other sensitive situation. Demonstrating respect for patient and parent space in the rooms and nurse workflow both in and out of the rooms is paramount for developing and maintaining a good working relationship and study success.

Continuous recording of parent–nurse interactions during the entire hospitalization of the child would have been ideal for capturing all the eligible interactions, particularly as each room had integrated cameras for monitoring the child for ventilator disconnection or acute decompensation. However, that type of undertaking would have required significantly more study personnel and time to monitor recordings, consent people going in and out of rooms, and determine the relevant parent–nurse communication to be transcribed. In addition, continuous recording would have required exponentially more secure storage space and potentially created more burden on the parent and nurse participants, possibly reducing enrollment (Parry et al., 2016; Themessl-Huber et al., 2008).

Selection of the recording devices was also important to ensure the quality of the data being collected (Henry et al., 2020). Although study participants consented to being recorded, the presence of a camera might have altered their natural behavior; prior research has shown this to be infrequent (Penner et al., 2007). A smaller, less conspicuous device is far less intrusive (Gross, 2016). Thus, incorporating the recording devices into the surrounding environment makes the data as close to naturalistic observation as possible. The inpatient hospital environment is known to be noisy (Darbyshire et al., 2019; Salandin et al., 2011). The use of video recordings in addition to audio was instrumental in overcoming some of the difficulty ambient noise created in understanding the recorded conversations. Editing software can also provide some solutions for overcoming the barriers created by noise such as filters and the ability to increase sound and change pitch.

Communication between health care providers and family caregivers is foundational for quality health care and importantly is bidirectional, relational, dependent on context, and consists of verbal, nonverbal, written, demonstrated, and observed elements (Franck & O’Brien, 2019; Khan et al., 2018; Molina-Mula & Gallo-Estrada, 2020). Audiovisual recordings enable capture of more communication behaviors and influences on those behaviors than audio recordings alone and enhance our understanding of the context associated with any communication encounter. The methods we have described can be used not only for studies of health care communication but also for diverse types of family nursing research and methods such as studies of how nurses do their work or intervene with patients and families, in addition to those involving mixed methods, telehealth, and ethnography (Bonafide et al., 2017; Tietbohl & White, 2022). Future studies may include interventions for tailoring patient care and family education by supplying family nurses with individualized feedback on their communication skills. Alternatively, communication skills training for families may also improve family education, family nursing, and child and family outcomes. Audiovisual recordings can significantly enhance our understanding of family nursing practice by capturing the nuances of interactions between family members and the nurses caring for them in new ways. This method can capture the formation and maintenance of relationships and processes nurses and families use to communicate, educate, and work with one another as well as the unique impacts of family nursing interventions on the care and health of patients and their families.

Conclusion

Audio and visual recordings are a rich trove of valuable data, and their use was well accepted in our recent research study. Audiovisual recordings are an excellent way to capture the unique bidirectional and contextual elements of the relationship between a family and their provider(s) and can be useful across a wide variety of study designs for family research, as well as for student education, and patient, caregiver, nurse, and other provider training. While recordings provide rich communication data, there are many caveats to their use. Planning for the best use of audiovisual recordings to capture study data must begin with the study design and ideally be woven throughout every aspect of the study including family, student, or provider recruitment and consent, data collection and management, dissemination of findings, and future use of recordings. A structured approach using the methods described herein will create a good foundation. While every attempt should be made to plan for all scenarios, researchers and educators must expect the unexpected and be prepared to problem solve and take quick action to mitigate potential data loss when it does. Through careful planning and execution, audio and visual recordings can be used to enhance a multitude of research designs and provide objective answers to future clinical family nursing practice questions.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23NR017396. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Erin K. Cash, BSc., is a second-year doctoral student in Biomedical Informatics at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), USA. Her work focuses on improving workflow efficiency, automating data synchronization between institutions, and incorporating physician feedback into the design and display of research results in the electronic medical record. Recent publications include:

Stewart, H. J., Cash, E. K., Hunter, L. L., Maloney, T., Vannest, J., & Moore, D. R. (2022). Speech cortical activation and connectivity in typically developing children and those with listening difficulties. NeuroImage: Clinical, 36, 103172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103172

Stewart, H. J., Cash, E. K., Pinkl, J., Nakeva von Mentzer, C., Lin, L., Hunter, L. L., & Moore, D. R. (2021). Adaptive hearing aid benefit in children with mild/moderate hearing loss: A registered, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. Ear and Hearing, 43(5), 1402–1415. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001230

Barbara K. Giambra, PhD, APRN, CPNP-PC, is an assistant professor in the Division of Research in Patient Services, Nursing and a Volunteer Assistant Professor with the James M. Anderson Center for Health System Excellence in the Department of Pediatrics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, USA. She is also an assistant professor - Research Affiliate with the College of Nursing at the University of Cincinnati. As a Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Dr. Giambra specializes in the care of children with chronic conditions. Her research focuses on families and children with complex chronic conditions and those who may be dependent on technology such as tracheotomy tubes, ventilators and feeding tubes. Her work has led to new methods for determining the prevalence of hospitalized long-term ventilator dependent children, risks of aspiration among children with aerodigestive disorders, and the effects of communication between the families of children with chronic conditions and their clinicians on family management of the child’s care and child and family well-being. Recent publications include: Giambra, B. K., & Spratling, R. (in press). Examining children with complex care and technology needs in the context of social determinants of health. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2022.11.004

Giambra, B. K., Mangeot, C., Benscoter, D., & Britto, M. T. (2021). A description of children dependent on long term ventilation via tracheostomy and their hospital resource use. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 61(8), 96–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2021.03.028 Giambra, B. K., Hass, S. M., Britto, M. T., & Lipstein, E. A. (2018). Exploration of parent-provider communication during clinic visits for children with chronic conditions. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 32(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.06.005

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Bogulski CA, Payakachat N, Rhoads SJ, Jones RD, McCoy HC, Dawson LC, & Eswaran H (in press). A comparison of audio-only and audio-visual tele-lactation consultation services: A mixed methods approach. Journal of Human Lactation, 39, 93–106. 10.1177/08903344221125118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonafide CP, Localio AR, Holmes JH, Nadkarni VM, Stemler S, MacMurchy M, Zander M, Roberts KE, Lin R, & Keren R (2017). Video analysis of factors associated with response time to physiologic monitor alarms in a children’s hospital. JAMA Pediatrics, 171(6), 524–531. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyles LM, Tate JA, & Happ MB (2008). Videorecording in clinical research: Mapping the ethical terrain. Nursing Research, 57(1), 59–63. 10.1097/01.NNR.0000280658.81136.e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruneau J, Moralejo D, Donovan C, & Parsons K (2021). Recruitment of healthcare providers into research studies. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research/Revue Canadienne de Recherche en Sciences Infirmieres, 53(4), 426–432. 10.1177/0844562120974911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe AY, Thomson JE, Unaka NI, Wagner V, Durling M, Moeller D, Ampomah E, Mangeot C, & Schondelmeyer AC (2021). Disparity in nurse discharge communication for hospitalized families based on English proficiency. Hospital Pediatrics, 11(3), 245–253. 10.1542/hpeds.2020-000745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darbyshire JL, Müller-Trapet M, Cheer J, Fazi FM, & Young JD (2019). Mapping sources of noise in an intensive care unit. Anaesthesia, 74(8), 1018–1025. https://doi.org/10.1111.anae.14690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGioia AM III, Greenhouse PK, & DiGioia CS (2012). Digital video recording in the inpatient setting: A tool for improving care experiences and efficiency while decreasing waste and cost. Quality Management in Healthcare, 21(4), 269–277. 10.097/QMH.0b013e31826d1d69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Essid S, Liem CCS, Richard G, & Sharma G (2019). Audiovisual analysis of music performances: Overview of an emerging field. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine, 36(1), 63–73. 10.1109/MSP.2018.2875511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edman K, Gustafsson AW, & Cuadra CB (2022). Recognising children’s involvement in child and family therapy sessions: A microanalysis of audiovisual recordings of actual practice. The British Journal of Social Work, 2021, 1–21. 10.1093/bjsw/bcab248 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franck LS, & O’Brien K (2019). The evolution of family-centered care: From supporting parent-delivered interventions to a model of family integrated care. Birth Defects Research, 111(15), 1044–1059. 10.1002/bdr2.1521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabbert F, Hope L, Luther K, Wright G, Ng M, & Oxburgh G (2021). Exploring the use of rapport in professional information-gathering contexts by systematically mapping the evidence base. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35, 329–341. 10.1002/acp.3762 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giambra BK, Broome ME, Sabourin T, Buelow J, & Stiffler D (2017). Integration of parent and nurse perspectives of communication to plan care for technology dependent children: The theory of shared communication. Journal of Pediatric Nursing: Nursing Care of Children and Families, 34, 29–35. 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giambra BK, Haas SM, Britto MT, & Lipstein EA (2018). Exploration of parent–provider communication during clinic visits for children with chronic conditions. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 32, 21–28. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembiewski EH, Espinoza Suarez NR, Maraboto Escarria AP, Yang AX, Kunneman M, Hassett LC, & Montori VM (2023). Video-based observation research: A systematic review of studies in outpatient health care settings. Patient Education and Counseling, 106, 42–67. 10.1016/j.pec.2022.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J, & Luxford Y (2009). Video: A decolonising strategy for intercultural communication in child and family health within ethnographic research. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 3(3), 218–232. 10.5172/mra.3.3.218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Schulman-Green D, Knafl K, & Reynolds NR (2015). A revised self-and family management framework. Nursing Outlook, 63(2), 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D (2016). Issues related to validity of videotaped observational data. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 13(5), 658–663. 10.1177/019394599101300511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidet KK, Tate J, Divirgilio-Thomas D, Kolanowski A, & Happ MB (2009). Methods to improve reliability of video-recorded behavioral data. Research in Nursing and Health, 32(4), 465–474. 10.1002/nur.20334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ MB, Garrett KL, Tate JA, DiVirgilio D, Houze MP, Demirci JR, George E, & Sereika SM (2014). Effect of a multi-level intervention on nurse-patient communication in the intensive care unit: Results of the SPEACS trial. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care, 43(2), 89–98. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SG, White AEC, Magnan EM, Hood-Medland EA, Gosdin M, Kravitz RL, Torres PJ, & Gerwing J (2020). Making the most of video recorded clinical encounters: Optimizing impact and productivity through interdisciplinary teamwork. Patient Education and Counseling, 103(10), 2178–2184. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holuszko O, Abdulcadir J, Abbott D, & Clancy J (2022). Health care providers’ (HCPs) readiness to adopt an interactive 3D webapp in consultations about female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): Qualitative evaluation of a prototype. Authorea. 10.22541/au.165659242.20197688/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iserson KV, Allan NG, Geiderman JM, & Goett RR (2019). Audiovisual recording in the emergency department: Ethical and legal issues. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 37(12), 2248–2252. 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson AF, Warner AM, Fleming E, & Schmidt B (2008). Factors influencing nurses’ participation in clinical research. Gastroenterology Nursing: The Official Journal of the Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates, 31(3), 198–208. 10.1097/01.SGA.0000324112.63532.a2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen C, Lüchau EC, Assing Hvidt E, & Grønning A (2022). Healthcare in the hand: Patients’ use of handheld technology in video consultations with their general practitioner. Digital Health, 8, 20552076221104669. 10.1177/20552076221104669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan A, Spector ND, Baird JD, Ashland M, Starmer AJ, Rosenbluth G, Garcia BM, Litterer KP, Rogers JE, Dalal AK, Lipsitz S, Yoon CS, Zigmont KR, Guiot A, O’Toole JK, Patel A, Bismilla Z, Coffey M, Langrish K, …Landrigan CP (2018). Patient safety after implementation of a coproduced family centered communication programme: Multicenter before and after intervention study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 363, Article k4764. 10.1136/bmj.k4764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni NG, Dalal JJ, & Kulkarni TN (2014). Audio-video recording of informed consent process: Boon or bane. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 5(1), 6–10. 10.4103/2229-3485.124547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen SA, Stommel W, Daniëls R, van Bokhoven MA, van der Weijden T, & Beurskens A (2018). Ascribing patients a passive role: Conversation analysis of practice nurses’ and patients’ goal setting and action planning talk. Research in Nursing and Health, 41(4), 389–397. 10.1002/nur.21883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipstein EA, Dodds CM, & Britto MT (2014). Real life clinic visits do not match the ideals of shared decision making. The Journal of Pediatrics, 165(1), 178–183.e1. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.03.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobe B, Morgan D, & Hoffman KA (2020). Qualitative data collection in an era of social distancing. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–8. 10.1177/1609406920937875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean S, Kelly M, Della PR, & Geddes F (2019). Video reflection in discharge communication skills training with simulated patients: A qualitative study of nursing students’ perceptions. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 28, 15–24. 10.1016/j.ecns.2018.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maltese AV, Danish JA, Bouldin RM, Harsh JA, & Bryan B (2016). What are students doing during lecture? Evidence from new technologies to capture student activity. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 39(2), 208–226. 10.1080/1743727X.2015.1041492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B, Huijgen T, & Henkes B (2021). Listening like a historian? A framework of “oral historical thinking” for engaging with audiovisual sources in secondary school education. Historical Encounters: A Journal of Historical Consciousness, Historical Cultures, and History Education, 8(1), 120–138. 10.52289/hej8.108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Guiu J, Arroyo-Fernández I, & Rubio R (2022). Impact of patients’ attitudes and dynamics in needs and life experiences during their journey in COPD: An ethnographic study. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine, 16(1), 121–132. 10.1080/17476348.2021.1891884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Mula J, & Gallo-Estrada J (2020). Impact of nurse-patient relationship on quality of care and patient autonomy in decision-making. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 835. 10.3390/ijerph17030835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health. (2022). Certificates of confidentiality. National Institute of Environmental Health Services. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/clinical/patientprotections/coc/index.cfm [Google Scholar]

- Nevins DS (2012). The use of electrical and electronic devices on Shabbat. https://www.rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/public/halakhah/teshuvot/2011-2020/electrical-electronic-devices-shabbat.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen ML, Sereika S, & Happ MB (2013). Nurse and patient characteristics associated with duration of nurse talk during patient encounters in ICU. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Critical Care, 42(1), 5–12. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2012.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallotti F, Weldon SM, & Lomi A (2020). Lost in translation: Collecting and coding data on social relations from audiovisual recordings. Social Networks, 69, 102–112. 10.1016/j.socnet.2020.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parry R, Pino M, Faull C, & Feathers L (2016). Acceptability and design of video-based research on healthcare communication: Evidence and recommendations. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(8), 1271–1284. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penner LA, Orom H, Albrecht TL, Franks MM, Foster TS, & Ruckdeschel JC (2007). Camera-related behaviors during video recorded medical interactions. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 31(2), 99–117. 10.1007/s10919-007-0024-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prictor M, Johnston C, & Hyatt A (2021). Overt and covert recordings of health care consultations in Australia: Some legal considerations. The Medical Journal of Australia, 214(3), 119–123.e1. 10.5694/mja2.50838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore MH, & Jackson MA, & Committee on Infectious Diseases. (2017). Infection prevention and control in pediatric ambulatory settings. Pediatrics, 140(5), Article e20172857. 10.1542/peds.2017-2857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roxburgh M (2006). An exploration of factors which constrain nurses from research participation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(5), 535–545. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01374.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salandin A, Arnold J, & Kornadt O (2011). Noise in an intensive care unit. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 130(6), 3754–3760. 10.1121/1.3655884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarabia-Cobo C, Taltavull-Aparicio JM, Miguélez-Chamorro A, Fernández-Rodríguez A, Ortego-Mate C, & Fernández-Peña R (2020). Experiences of caregiving and quality of healthcare among caregivers of patients with complex chronic processes: A qualitative study. Applied Nursing Research, 56, 151344. 10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seuren LM, Wherton J, Greenhalgh T, Cameron D, A’Court C, & Shaw SE (2020). Physical examinations via video for patients with heart failure: Qualitative study using conversation analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(2), e16694. 10.2196/16694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, & Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. (2007). 2007 Guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. American Journal of Infection Control, 35(10, Suppl. 2), S65–S164. 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiers JA, Costantino M, & Faucett J (2000). Video technology: Use in nursing research. AAOHN Journal, 48(3), 119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian K, Maas J, Borchers JO, & Hollan JD (2021). From detectables to inspectables: Understanding qualitative analysis of audiovisual data. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘21). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA,Article 518, 1–10. 10.1145/3411764.3445458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Themessl-Huber M, Humphris G, Dowell J, Macgillivray S, Rushmer R, & Williams B (2008). Audio-visual recording of patient-GP consultations for research purposes: A literature review on recruiting rates and strategies. Patient Education and Counseling, 71(2), 157–168. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tietbohl CK, & White AEC (2022). Making conversation analysis accessible: A conceptual guide for health services researchers. Qualitative Health Research, 32(8–9), 1246–1258. 10.1177/10497323221090831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbanosky C, Merritt L, & Maxwell J (in press). Fathers’ perceptions of the NICU experience. Journal of Neonatal Nursing. 10.1016/j.jnn.2022.11.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaarzon-Morel P, Barwick L, & Green J (2021). Sharing and storing digital cultural records in Central Australian Indigenous communities. New Media & Society, 23(4), 692–714. 10.1177/1461444820954201 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gelderen S, Krumwiede N, & Christian A (2016). Teaching family nursing through simulation: Family-care rubric development. Clinical Simulation in Nursing, 12(5), 159–170. 10.1016/j.ecns.2016.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walter JK, Sachs E, Schall TE, Dewitt AG, Miller VA, Arnold RM, & Feudtner C (2019). Interprofessional team-work during family meetings in the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 57(6), 1089–1098. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager KA, & Bauer-Wu S (2013). Cultural humility: Essential foundation for clinical researchers. Applied Nursing Research, 26(4), 251–256. 10.1016/j.apnr.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Roberts PA, & Della PR (2021). Nurse-caregiver communication of hospital-to-home transition information at a tertiary pediatric hospital in Western Australia: A multi-stage qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 60, 83–91. 10.1016/j.pedn.2021.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]