Abstract

Background

Kidney transplantation (KT) is the preferred treatment for children with end-stage kidney disease. Recent advances in immunosuppression and advances in donor specific antibody (DSA) testing have resulted in prolonged allograft survival; however, standardized approaches for surveillance DSA monitoring and management of de novo (dn) DSA are widely variable among pediatric KT programs.

Methods

Pediatric transplant nephrologists in the multi-center Improving Renal Outcomes Collaborative (IROC) participated in a voluntary, web-based survey between 2019 and 2020. Centers provided information pertaining to frequency and timing of routine DSA surveillance and theoretical management of dnDSA development in the setting of stable graft function.

Results

29/30 IROC centers responded to the survey. Among the participating centers, screening for DSA occurs, on average, every 3 months for the first 12 months post-transplant. Antibody mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) and trend most frequently directed changes in patient management. Increased creatinine above baseline was reported by all centers as an indication for DSA assessment outside of routine surveillance testing. 24/29 centers continue to monitor DSA and/or intensify immunosuppression after detection of antibodies in the setting of stable graft function. In addition to enhanced monitoring, 10/29 centers reported performing an allograft biopsy upon detection of dnDSA even in the setting of stable graft function.

Conclusions

This descriptive report is the largest reported survey of pediatric transplant nephrologist practice patterns on this topic and provides a reference for monitoring dnDSA in the pediatric kidney transplant population.

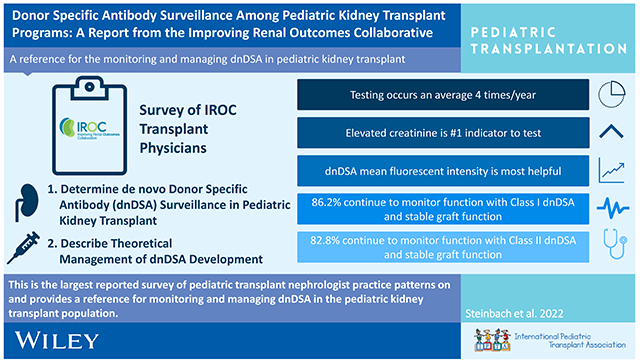

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

This descriptive report is the largest reported survey of pediatric transplant nephrologist practice patterns on this topic and provides a reference for monitoring dnDSA in the pediatric kidney transplant population.

Introduction

De novo donor specific antibody (dnDSA) development occurs in 15-45% of pediatric kidney transplant (KT) recipients within the first 2 years post-transplant [1]. The formation of dnDSA likely plays a pivotal role in the development of chronic allograft nephropathy and associated premature graft failure [2–6]. Consensus guidelines support use of routine screening for dnDSA development after KT [7]; however, there is no clear consensus on the timing or frequency of surveillance dnDSA assessment, or subsequent management once dnDSA is detected in the setting of stable allograft function. This gap is due, in part, to the relatively small number of pediatric kidney transplants performed in any given year in the United States [8, 9].

The Improving Renal Outcomes Collaborative (IROC) is a multicenter, network-based, learning health system with 38 participating academic pediatric KT centers at the time of this study. The primary aim of IROC is to characterize clinical outcome data for pediatric KT patients, provide center- and network-level analytics, and inform center-based quality improvement initiatives to improve health, longevity, and quality of life for pediatric KT patients and their families [10, 11]. Over half of all pediatric kidney transplants in the US are currently performed at centers participating in IROC.

We leveraged the IROC infrastructure to distribute a survey-based assessment to: 1) evaluate practice patterns for dnDSA surveillance across IROC centers and 2) characterize subsequent clinical management of dnDSA development in the setting of stable allograft function. Lastly, practice patterns were queried regarding the use of “for-cause” versus protocol kidney transplant biopsies in relationship to DSA surveillance protocols.

Methods

The parent IROC study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center under a master reliance agreement that was approved by each participating center. This agreement allows Cincinnati Children’s Medical Center to act as the IRB of record for the registry-specific data analyzed in this study. A separate IRB specific to this study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board (201909832).

A web-based survey was designed using the “Research Electronic Data Capture” database (REDCap). The survey was distributed electronically to IROC centers between October 2019 and March 2020. Each center was requested to identify one pediatric transplant nephrologist – specifically the IROC site principal investigator – to complete the survey. Individuals completing the survey were notified that the purpose of the survey was to report center-specific practices for DSA surveillance and general management. No patient-specific data or protected health information were required to complete the survey.

Within the survey, information was obtained pertaining to patterns of routine DSA surveillance, including time, interval, and frequency of testing post-transplant. Indication(s) for obtaining DSA, other than surveillance, was also assessed. After patterns of DSA surveillance were established, information concerning the DSA-specific parameters used for medical decisions was surveyed. These parameters included antibody locus, mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) of the antibody, C1q positivity, dnDSA MFI trend, and epitope target. Furthermore, the pediatric transplant nephrologists surveyed were asked about the theoretical practice management in the setting of dnDSA development but with stable allograft function.

Lastly, to understand the relationship between DSA surveillance and allograft biopsy practice patterns within the IROC cohort, participating centers were asked whether the center performed surveillance biopsies as a standard of care after transplant and the practice pattern of obtaining “for-cause” biopsies in the setting of dnDSA development.

Results

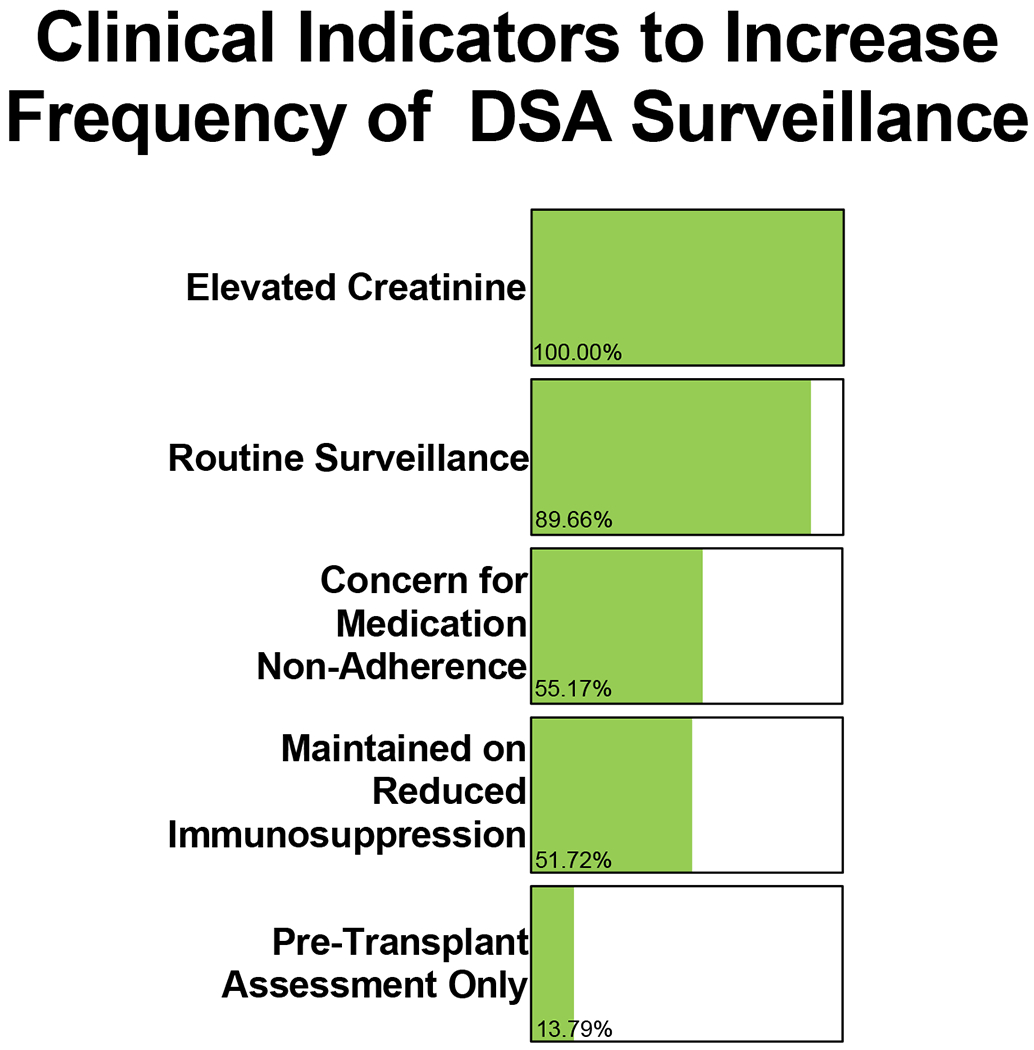

Of the 30 IROC centers surveyed at the time of this study, 29 centers provided data for analysis. All 29 IROC centers completed 17/17 (100.0%) questions queried by this survey. The survey questions and responses can be found in Tables 1–4. 26/29 (89.7%) reported performing routine DSA surveillance after transplant whereas one center reported assessment for dnDSA occurred “for cause” only (Table 1). All 29 centers indicated that elevated creatinine above baseline was used as a clear indication to evaluate for dnDSA post-transplant. Of the 29 participating centers, 16 centers (55.2%) indicated that DSA testing was performed routinely if there were concerns for medication non-adherence and 15 centers (51.7%) reported additional monitoring for dnDSA in the setting of reduction of immunosuppression for either infectious or malignant complications (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Survey questions pertaining to general DSA testing practices and biopsy performance at IROC centers.

| Survey Question | Response “Yes” | Response “No” |

|---|---|---|

| Do you check DSA post-transplant at your program? (%) | 29/29 (100.0) | 0/29 (0.0) |

| Indications used to inform obtaining DSA- mark all that apply. | ||

| Elevated serum creatinine | 29/29 (100.0) | |

| Routine surveillance | 25/29 (86.2) | |

| Pre-transplant assessment only | 4/29 (13.8) | |

| Review of medication adherence/ concern for non-adherence | 16/29 (55.2) | |

| Need for chronic under-immunosuppression | 15/29 (51.7) | |

| Do you have an HLA Lab on site? | 21/29 (72.4) | 8/29 (27.6) |

| What is the turnaround time for a “STAT” DSA order? | ||

| < 24 hours | 12/29 (41.4) | |

| 24 – 48 hours | 15/29 (51.7) | |

| > 48 hours | 2/29 (6.9) | |

| Are surveillance biopsies performed at your center? | 12/29 (41.4) | 17/29 (58.96) |

| If DSA is detected, is a biopsy performed? | 10/29 (34.5) | 19/29 (65.5) |

Table 4.

Dosing and frequency for the theoretical management of Class I and Class II DSA with IVIG alone and IVIG + Rituximab.

| Dosing and Frequency | IVIG Alone | IVIG + Rituximab |

|---|---|---|

| 1 g/kg x 3 months | 8/29 (27.6) | |

| 2 g/kg x 6 months | 2/29 (6.9) | |

| Other * | 10/29 (34.5) | |

| IVIG alone not used at our center | 9/29 (31.0) | |

| 375 mg/m2 x 1 dose | 11/29 (37.9) | |

| 375 mg/m2 x 2 dose, 6 months apart | 6/29 (20.7) | |

| Other ** | 13/29 (44.8) | |

| IVIG + Rituximab not used at our center | 2/29 (6.9) |

Other responses include: IVIG alone 1g/kg x 1 month (3), 2 g/kg x 1 month (1), 1-2 g/kg x 4 months (2), 2 g/kg x 2 months with repeat biopsy (1), 2 g/kg x 6 months with repeat biopsy (1), IVIG 1 g/kg + 05 g/kg SQ x 1 month (1), 2 g/kg/month until C1q is negative for 2 months (1), 1 g/kg/week x 4 weeks (1).

Other responses include: Rituximab 375 mg/m2 x 2 – two weeks apart + IVIG 2 g/kg x 1 for 4 months (2), Rituximab 375 mg/m2 x 2 – two weeks apart (3), Rituximab 375 mg/m2 x 4 (1), Rituximab 375 mg/m2 at week 1 and week 4 + IVIG 1 g/kg/week x 4 weeks (1), Rituximab 375 mg/m2 + IVIG 1 g/kg x 2 – two weeks apart (1), Rituximab 375 mg/m2 x 2 with repeat DSA testing (1), Rituximab 500 mg/m2 x 1 with monitoring for second dose (1), only dosing with Rituximab 375 mg/m2 x 1 with a second dose if CD19/20 is not suppressed after dose 1 (1), Rituximab 375 mg/m2 x 2 – six months apart (1), Rituximab 375 mg/m2 x 1 + IVIG 1 g/mg + plasmapheresis x 5 with repeat biopsy (1).

Figure 1. Clinical indicators leveraged to increase the frequency of DSA surveillance.

29/29 (100.0%) IROC centers reported elevated creatinine is one indication for obtaining DSA surveillance. 26/29 (89.7%) IROC centers reported obtaining DSA testing for routine surveillance for graft rejection. 4/29 (13.8%) IROC centers reported obtaining DSA surveillance as part of the pre-transplant assessment only. 16/29 (55.2%) IROC centers reported concerns for medication non-adherence in patients is an indication for obtaining DSA surveillance and 15/29 (51.7%) IROC centers reported obtaining DSA testing to evaluate patients requiring reduced immunosuppression due to infectious or malignant complications. Centers were asked to select “all that apply.”

Frequency of surveillance

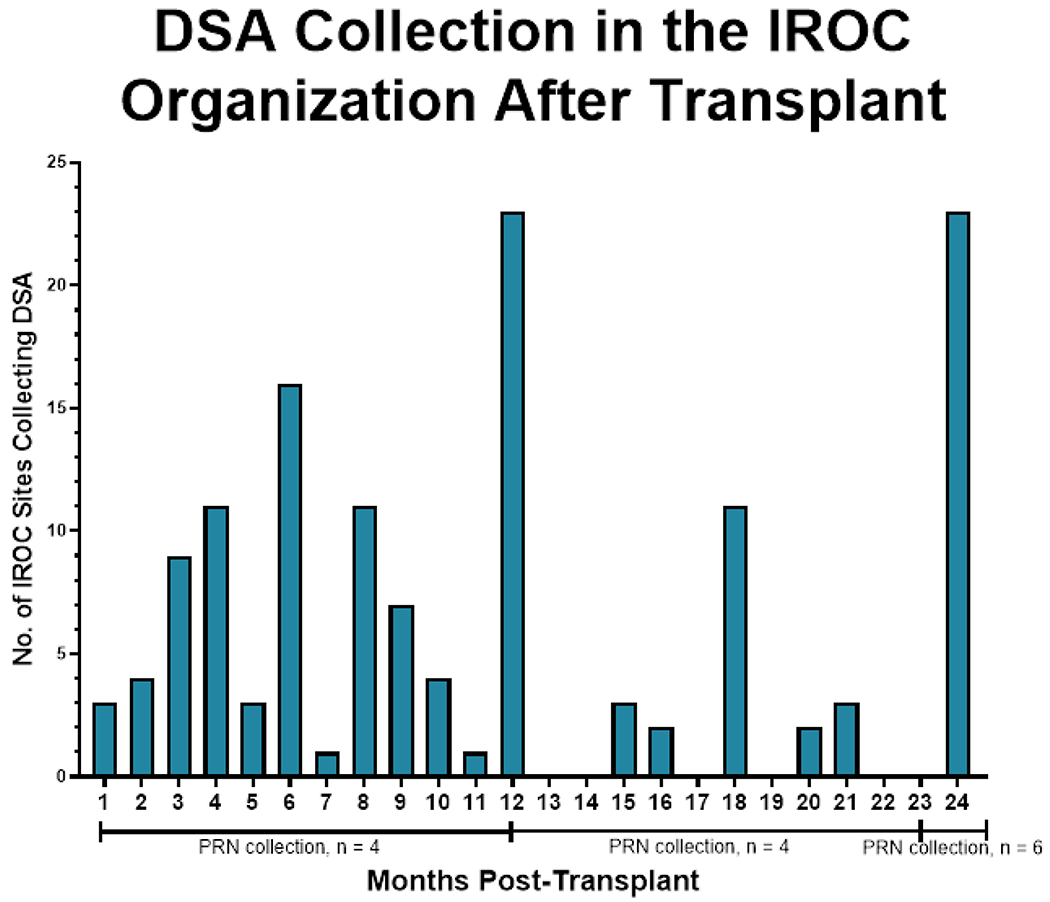

IROC centers were also asked to indicate the frequency of DSA surveillance through the first-year post-transplant (0-12 months), between 12-24 months, and 24+ months post-transplant. There was wide variability in the frequency of DSA monitoring post-transplant across all IROC participating centers (Figure 2). One center indicated they obtain DSA testing only as needed; conversely, one center reported DSA surveillance every month for the first year after transplant. On average, IROC centers perform DSA surveillance testing four times in the first-year post-transplant (once every 3 months). Between 12-24 months post-transplant, DSA surveillance occurs an average of two times per year (once every 6 months) with no centers reporting routine DSA surveillance more than four times per year, unless indicated otherwise. After 24 months post-transplant, routine DSA surveillance occurs an average of 1.5 times per year- with an increased number of centers moving towards PRN (as needed) or yearly monitoring. The full response list of DSA surveillance frequencies can be found in Table 2.

Figure 2. Frequency of routine DSA surveillance after kidney transplantation.

The most frequent time points for DSA collection were at 12 months and 24 months post-transplantation (23/29, 79.3%) at both time points. As needed DSA surveillance, as indicated by Figure 1, increases after 24 months post-transplantation (PRN collection).

Table 2.

DSA testing frequency for centers from 0-12 post-kidney transplantation, 12-24 months post-transplantation, and +24 months post-transplantation.

| DSA Testing Frequency | 0-12 Months Post-Transplant | 12-24 Months Post-Transplant | +24 Months Post-Transplant |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly | 4/29 (13.8) | ||

| At 1 month | 4/29 (13.8) | ||

| At 2 months | 3/29 (10.3) | ||

| At 3 months | 4/29 (13.8) | ||

| At 6 months | 13/29 (44.8) | 1/29 (3.4) | |

| At 9 months | 1/29 (3.4) | ||

| At 12 months | 12/29 (41.4) | 11/29 (37.9) | 18/29 (62.1) |

| Every 3 months | 8/29 (27.6) | 6/29 (20.7) | 3/29 (10.3) |

| Every 6 months | 2/29 (6.9) | 3/29 (10.3) | 1/29 (3.4) |

| Every 12 months | 2/29 (6.9) | ||

| PRN | 4/29 (13.8) | 4/29 (13.8) | 6/29 (20.7) |

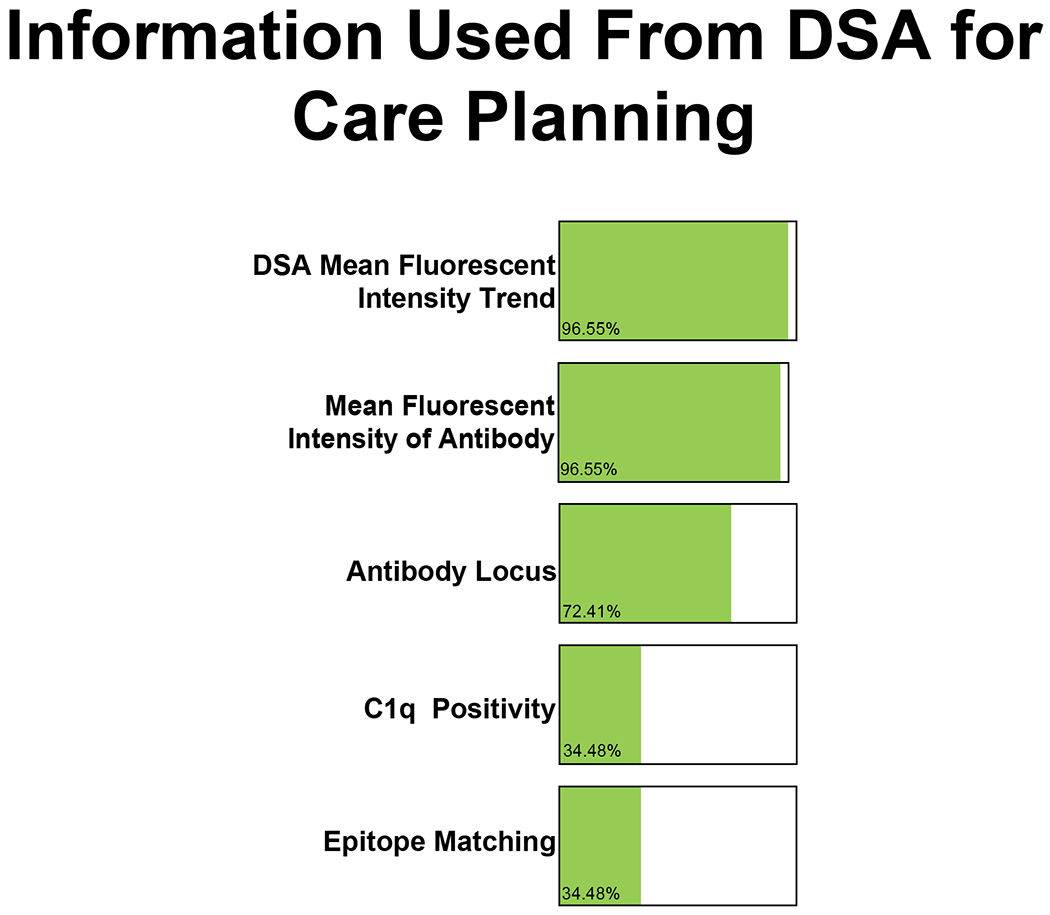

In addition to the frequency of monitoring, centers were asked about the components of DSA surveillance testing used to inform changes in clinical care. Survey prompts are displayed in Table 3. 28/29 (96.5%) centers used DSA mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) level and trend of MFI intensity to guide care planning. 21/29 (72.4%) centers indicated the use of antibody locus, 10/29 (34.5%) centers indicated the use of complement binding (C1q positivity), and 10/29 (34.5%) epitope matching to determine clinical care. In their approach to surveillance, IROC centers were most likely to use DSA MFI and trend of MFI intensity to direct management (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Questions surveying practice patterns used for care planning in the setting of DSA positivity.

| Survey Question | Response “Yes” |

|---|---|

| Information used from DSA for care planning- mark all that apply. | |

| Mean fluorescent intensity of antibody | 28/29 (96.6) |

| Antibody locus | 21/29 (72.4) |

| C1q positivity | 10/29 (34.5) |

| DSA mean fluorescent intensity trend | 28/29 (96.6) |

| Epitope matching | 10/29 (34.5) |

| Theoretical practice of Class I DSA but stable creatinine- mark all that apply. | |

| Continue to monitor | 25/29 (86.2) |

| Intensify immunosuppression | 18/29 (62.1) |

| High dose IVIG (1 g/kg) and Rituximab | 2/29 (6.9) |

| IVIG alone | 3/29 (10.3) |

| Plasmapheresis | 0/29 (0.0) |

| Theoretical practice of Class II DSA but stable creatinine- mark all that apply. | |

| Continue to monitor | 24/29 (82.8) |

| Intensify immunosuppression | 19/29 (65.5) |

| High dose IVIG (1 g/kg) and Rituximab | 3/29 (10.3) |

| IVIG alone | 3/29 (10.3) |

| Plasmapheresis | 1/29 (3.4) |

Figure 3. Information used from DSA surveillance to inform clinical care planning.

28/29 (96.6%) IROC centers indicated that the mean fluorescent intensity of the antibody and mean fluorescent intensity trend from DSA testing are the most used information from DSA surveillance. 21/29 (72.4%) centers indicated that antibody locus is also used for care planning and 10/29 (34.5%) IROC centers indicated the use of C1q positivity and epitope matching data to inform their future care planning. Centers were asked to select “all that apply.”

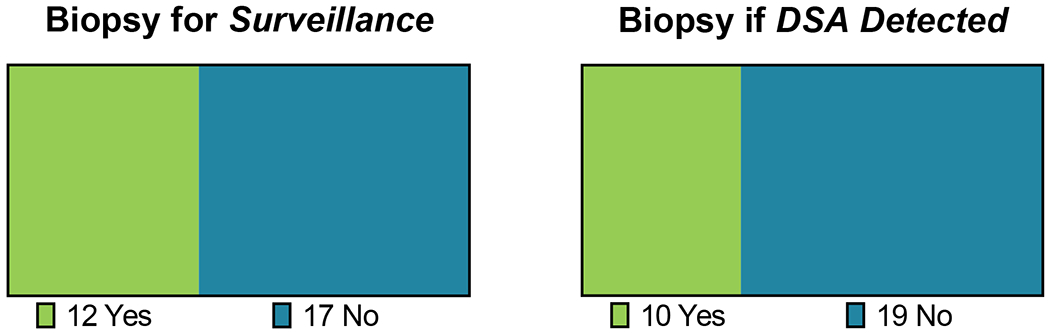

Relationship of surveillance DSA assessment with kidney biopsy

Indications for kidney transplant biopsy were surveyed from the IROC centers as well. 12/29 (41.4%) centers perform surveillance (protocol) biopsies in parallel with routine DSA surveillance as part of their center protocol. 10/29 (34.5%) IROC centers indicated they would perform a biopsy “for-cause” if dnDSA were detected on surveillance testing (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Temporal relationship between kidney biopsy and DSA surveillance.

12/29 (41.4%) IROC centers also reported performing routine, surveillance biopsies in the post-transplant period with surveillance DSA performed at the same timepoint(s). 10/29 (34.5%) IROC centers indicated they would perform a biopsy “for-cause” if dnDSA were detected on surveillance testing.

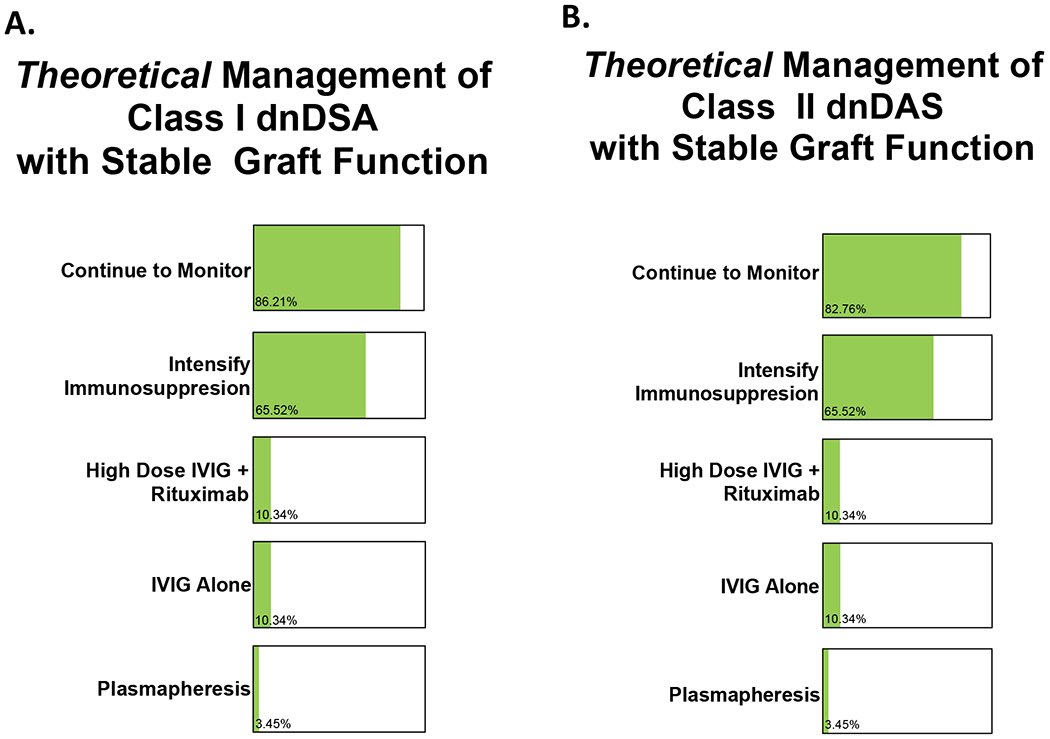

Theoretical management of class I dnDSA

Respondents were queried regarding their theoretical management of new class I dnDSA with stable allograft function. Survey prompts specific to theoretical IVIG and rituximab dosing and frequency in the setting of class I dnDSA can be found in Table 4. In the setting of detected class I dnDSA, 19/29 (65.5%) would intensify the immunosuppressive therapy as a first line intervention (Figure 5A). Conversely, 3 centers (10.3%) indicated they would initiate high-dose (2 g/kg) intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIG) with rituximab while an additional 3 centers (10.3%) reported they would initiate IVIG alone (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Differences in management of class I and class II dnDSA.

Centers were asked to select “all that apply.”

A. Theoretical management of class I dnDSA with stable allograft function is represented below. 25/29 (86.2%) would continue monitoring donor-specific antibodies and 19/29 (65.5%) would intensify immunosuppressive therapy. 3/29 (10.3%) of the IROC centers would initiate high dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) therapy and rituximab with 3/29 (10.3%) opting for IVIG alone. 1/29 (3.5%) would also initiate plasmapheresis.

B. Theoretical management of class II dnDSA with stable allograft function did not significantly differ from class I DSA management. 24/29 (82.8%) IROC centers would continue to monitor donor-specific antibodies with 19/25 (65.5%) intensifying immunosuppressive therapy. 3/29 (10.3%) IROC centers would initiate high dose IVIG and rituximab with another 3/29 (10.3%) initiating IVIG alone and 1/29 (3.5%) opting for initiation of plasmapheresis.

Theoretical management of class II dnDSA

Respondents were queried regarding their theoretical management of new class II dnDSA with stable allograft function. Survey prompts specific to theoretical IVIG and rituximab dosing and frequency in the setting of class II dnDSA can be found in Table 4. In the setting of detected class II dnDSA, 19/29 (65.5%) would intensify the immunosuppressive therapy as a first line intervention (Figure 5B). Conversely, 3 centers (10.3%) indicated they would initiate high-dose IVIG with rituximab while an additional 3 centers (10.3%) reported they would initiate IVIG alone (Figure 5B).

Discussion

Like many chronic diseases in children, pediatric kidney transplantation is a rare condition such that no single institution cares for enough patients to easily produce generalizable knowledge—a limitation that can be overcome with collaborative, network-based learning health systems [12]. IROC has previously leveraged this network-based infrastructure to evaluate kidney transplant outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic using a similar data capture tool within REDCap [13]. Through use of a REDCap-based assessment, we were able to leverage a simple, time-efficient data collection tool to collect information specific to DSA surveillance and management. The data capture tool within REDCap was emphasized on a recurring basis during the network wide IROC meetings in 2019-2020 to facilitate timely, accurate, and complete data entry across participating centers.

Based on this network-based survey, we found that routine post-transplant DSA surveillance occurs at all reporting centers within the IROC collaborative; however, the frequency and indications for assessment varies widely. Most IROC centers report monitoring DSA an average of four times in the first-year post-transplant (approximately once every 3 months) with ongoing monitoring through 24 months post-transplant. The primary indicators for DSA testing outside of standard surveillance include increased creatinine above baseline, reported or suspected non-adherence with immunosuppressive therapy, and/or need for chronic reduction in immunosuppression. Although, many centers perform surveillance (protocol) biopsies in parallel with routine DSA surveillance, almost 35% of IROC centers indicated they would perform a biopsy “for-cause” if dnDSA were detected on surveillance testing.

In parallel with the reported frequency of DSA surveillance, we obtained vital information regarding management of DSA in the setting of stable creatinine. The decision to “treat” antibody positivity is nuanced. Based on this survey, IROC centers were most likely to continue to monitor and/or increase immunosuppressive therapies as a response to development of dnDSA with stable allograft function. Antibody strength – as reported by the MFI trend - was the primary feature guiding the decision to change approach. MFI measurements and trends are semi-quantitative measurements and may be influenced by epitope sharing [14]. Epitopes are the immunogenic regions of human leukocyte antigens (HLAs), and recent findings suggest that evaluation of epitope specificity of the antibody may be more predictive of pathogenicity [15]. In parallel with MFI trend, 10/29 (34.5%) centers reported the use of epitope assessment as part of DSA surveillance post-transplant. In addition to MFI and epitope matching, the ability of an antibody to interact and fix complement component (C1q) may also be a valid predictor of overall graft survival and/or acute antibody-mediated rejection [16–18]. At present, C1q positivity appears to be used by approximately one-third (10/29, 34.5%) of IROC centers.

Centers were asked to report their theoretical management of dnDSA in the setting of stable allograft functioning. In this scenario, there was again variable practice patterns; however, most centers (19/29 [66.5%]) reported the first-line response would be to increase and intensify the maintenance immunosuppressive therapy in the setting of newly detected dnDSA. A minority of centers reported use of either IVIG alone or as part of a combination therapy with Rituximab for patients with new dnDSA but stable allograft function.

The most notable strength of this work is centered around the broad capture of practice patterns and general management strategies for dnDSA development in the pediatric KT population. Limitations certainly exist and should be acknowledged. First, the data collected from the REDCap collection tool were provided on a voluntary basis; thus, only submitted information was considered. In line with this, self-reported data is at risk for confounding factors due to reporting and selection biases. At the time of this survey, there was less wide-spread use of cell free DNA in the monitoring of rejection within the pediatric KT population. In contrast, cell free DNA is currently more widely used to monitor for rejection – and often in parallel with DSA surveillance. We did not solicit responses on use of cell free DNA monitoring as part of this study; certainly, this would be an area for future evaluation. Although we have detailed information regarding surveillance practices, the reported management strategies represent a theoretical patient scenario and actual management of dnDSA may not fully reflect the reported practices within this survey. Despite this weakness, we believe the responses – capturing over half of all pediatric KT programs in the United States - offer a valuable reference point for pediatric nephrologists providing transplant care.

Our work highlights the variation in DSA surveillance patterns and theoretical clinical management of dnDSA at pediatric KT centers in the United States. Future work should leverage the opportunity to standardize DSA surveillance across a multicenter collaborative with the inclusion of emerging biomarkers for rejection such as cell free DNA in an effort to improve long-term allograft and patient outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all those participating in the Improving Renal Outcomes Collaborative study.

Funding

EJS is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (T32DK007690-29). LAH is funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01DK128835).

Abbreviations

- KT

kidney transplantation

- DSA

donor specific antibody

- IROC

Improving Renal Outcomes Collaborative

- MFI

mean fluorescent intensity

- REDCap

Research Electronic Data Capture

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

Footnotes

Disclosures

DKH is a consultant for Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, Kaneka, Bioporto, and Maximus.

Data statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Schinstock CA, Gandhi MJ, and Stegall MD, Interpreting Anti-HLA Antibody Testing Data: A Practical Guide for Physicians. Transplantation, 2016. 100(8): p. 1619–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hidalgo LG, et al. , De novo donor-specific antibody at the time of kidney transplant biopsy associates with microvascular pathology and late graft failure. Am J Transplant, 2009. 9(11): p. 2532–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Everly MJ, et al. , Reducing de novo donor-specific antibody levels during acute rejection diminishes renal allograft loss. Am J Transplant, 2009. 9(5): p. 1063–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willicombe M, et al. , De novo DQ donor-specific antibodies are associated with a significant risk of antibody-mediated rejection and transplant glomerulopathy. Transplantation, 2012. 94(2): p. 172–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiebe C, et al. , Evolution and clinical pathologic correlations of de novo donor-specific HLA antibody post kidney transplant. Am J Transplant, 2012. 12(5): p. 1157–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JJ, et al. , The clinical spectrum of de novo donor-specific antibodies in pediatric renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant, 2014. 14(10): p. 2350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tait BD, et al. , Consensus guidelines on the testing and clinical management issues associated with HLA and non-HLA antibodies in transplantation. Transplantation, 2013. 95(1): p. 19–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.OPTN/SRTR 2018 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients; 2018. [cited 2022 05/31/2022]; Available from: https://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annual_reports/2018/Kidney.aspx#:~:text=Figure%20KI%20128).-,Transplant,representing%20only%2036.2%25%20in%202018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Arendonk KJ, et al. , National trends over 25 years in pediatric kidney transplant outcomes. Pediatrics, 2014. 133(4): p. 594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooper DK, et al. , Multicenter data to improve health for pediatric renal transplant recipients in North America: Complementary approaches of NAPRTCS and IROC. Pediatr Transplant, 2021. 25(1): p. e13891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kelly B, et al. , Quality initiatives in pediatric transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant, 2019. 24(1): p. 64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forrest CB, et al. , PEDSnet: how a prototype pediatric learning health system is being expanded into a national network. Health Aff (Millwood), 2014. 33(7): p. 1171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varnell C Jr., et al. , COVID-19 in pediatric kidney transplantation: The Improving Renal Outcomes Collaborative. Am J Transplant, 2021. 21(8): p. 2740–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konvalinka A and Tinckam K, Utility of HLA Antibody Testing in Kidney Transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2015. 26(7): p. 1489–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miettinen J, et al. , Donor-specific HLA antibodies and graft function in children after renal transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol, 2012. 27(6): p. 1011–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayde N, et al. , C1q-binding DSA and allograft outcomes in pediatric kidney transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant, 2021. 25(2): p. e13885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang R, Donor-Specific Antibodies in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, 2018. 13(1): p. 182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freitas MC, et al. , The role of immunoglobulin-G subclasses and C1q in de novo HLA-DQ donor-specific antibody kidney transplantation outcomes. Transplantation, 2013. 95(9): p. 1113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]