Summary

Despite the high burden of child and adolescent mental health problems in LMICs, attributable to poverty and childhood adversity, access to quality mental healthcare services is poor. LMICs, due to paucity of resources, also contend with shortage of trained mental health workers and paucity of standardized intervention modules and materials. In the wake of these challenges, and given that child development and mental health concerns cut across a plethora of disciplines, sectors and services, public health models need to incorporate integrated approaches to responding to the mental health and psychosocial care needs of vulnerable children. This article presents a working model for convergence, and the practice of transdisciplinary Public Health, in order to address the gaps and challenges in child and adolescent mental healthcare in LMICs. Located in a state tertiary mental healthcare institution, this national level model reaches (child care) service providers and stakeholders, duty-bearers, and citizens (namely parents, teachers, protection functionaries, health workers and other interested parties) through capacity building initiatives and tele-mentoring services, public discourse series, developed for a South Asian context and delivered in diverse languages.

Role of Funding Source

The Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India, provides financial support to the SAMVAD initiative.

Keywords: Child and adolescent mental health, LMIC, South Asia, Public health models, Transdisciplinary approaches, Adverse childhood experiences

A large proportion of children and adolescents live in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs) with limited access to mental health services1 and high exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).2 Developmental disabilities, emotional disorders and disruptive behaviour disorders, contribute heavily to the global burden of mental health concerns in children, and are a focus for child mental health service development.3 Given the ethno-diversity in LMICs, child and adolescent mental health (CAMH) also entails cross-cultural considerations in risk and protective factors, and the manifestation of child psychopathology.4 Barriers to implementation of CAMH services in LMICs include shortage of CAMH specialists, insufficient financial resources, a paucity of culturally-appropriate methods and materials for intervention. Such settings thus require the optimization of their limited resources by task sharing, particularly through intersectoral collaboration between departments of health, education and social development and community-based service delivery.5 The Lancet Global Mental Health CAMH Series, emphasizing universal and targeted interventions in early childhood through school and community-based programs6 is also in concurrence with global public mental health agendas aimed at reduction of mental ill-health disparities by taking cognizance of social determinants of CAMH.7 Capacity building of primary care providers, found to enhance psychosocial outcomes in children,8 is a cornerstone of such integration and task-sharing approaches.9

In recent years, situational factors in India, including protection violations amongst institutionalized children (namely abuse and neglect), and a social audit revealing gaps in implementation of mental health and rehabilitation-related provisions in the juvenile justice law,10 propelled CAMH issues into public discourse and consciousness. In response, the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), a tertiary-level mental healthcare institution, under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, established a unique country-wide initiative called SAMVAD (Support, Advocacy & Mental health interventions for children in Vulnerable circumstances And Distress). Supported by the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MoWCD), Government of India, SAMVAD is an expanded and scaled up version of what was previously a community-based CAMH service project. A one-of-a kind initiative, it serves as a resource for the country, to increase access to and availability of child and adolescent mental health and protection support and services through the use of integrated approaches to child well-being.

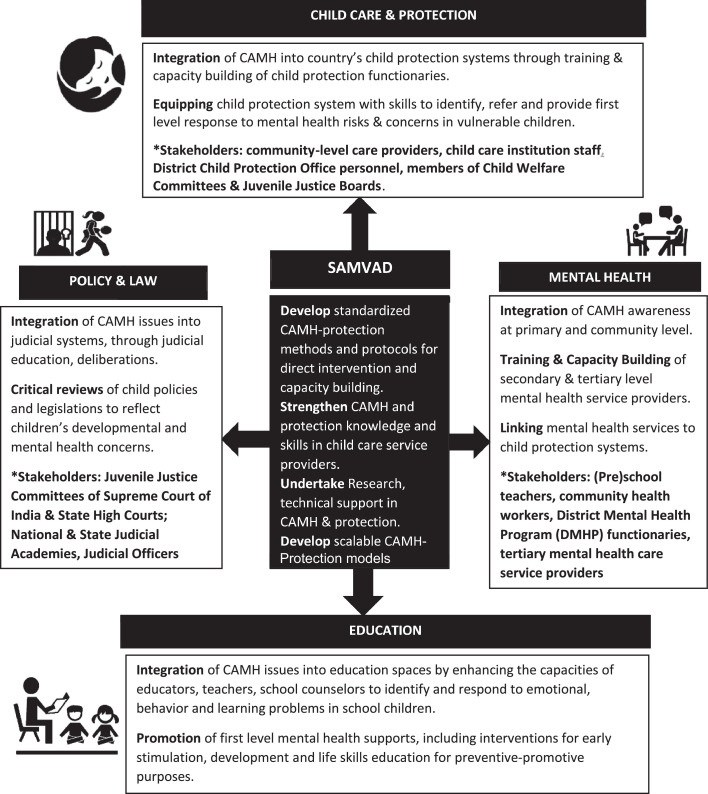

Working in four verticals, Care and Protection,1 Education, Mental Health and Law and Policy, the SAMVAD model (refer to Figure 1) is unique in that it employs transdisciplinary approaches, to enable solutions to complex CAMH problems through dialogue and capacitation of stakeholders from multiple disciplines. SAMVAD undertakes research, training and capacity building and related services, using methodologies that draw upon mono-disciplinary expertise, whilst also amalgamating the diverse viewpoints that characterize systemic and sectoral priorities of individual stakeholders interacting with children.

Figure 1.

The SAMVAD model. *(For further details, refer to: www.nimhanschildprotect.in).

In line with transdisciplinary frameworks, SAMVAD applies innovative teaching and learning methods of participatory, creative and skill-based pedagogies, to deliver innovations in CAMH awareness and capacitation. SAMVAD's essential training program focuses on the fundamentals of child mental health and protection work, that would be relevant to LMICs, namely: sensitization to children and childhood experiences, application of child development concepts, identification of vulnerability and protection risks and contexts, communication and counseling techniques with children, provision of first level responses to common child mental health disorders, and key provisions of child law in India, so as to locate the implementation of the law in relevant child psychosocial and protection contexts. This content is adapted to the specific professional needs and functions of various types of child care workers and service providers. More in-depth and specialized programs, such as those focusing on child sexual abuse, children in conflict with the law and children with disability, and early childhood education are also delivered, particularly to secondary and tertiary level child care workers across various sectors. Recent training initiatives include: the launch of India's first training program on child forensics—integrating mental health & legal dimensions in child sexual abuse; incorporation of education, mental health and protection perspectives into interventions for children with disability; percolation of CAMH and protection concerns into grassroot levels through training of the Panchayati Raj, the rural system of local self-government in India; engagement with the country's judicial (education) systems, enabling them to integrate knowledge of CAMH, into areas of judicial interface with child witnesses, in the contexts of child sexual abuse, juvenile justice and child custody.

While the effectiveness of SAMVAD's training programs have yet to be systematically studied, there is much anecdotal information and communication from child care workers that stands as a testimony to the relevance of the content, in terms of skill-building and of responding to the challenges of field practice. However, what makes the training and capacity building scalable are the conceptual frameworks, containing universally relevant constructs of child development, mental health and protection, and the easy-to-use activity-based methodologies,2 that allow for roll out in a standardized manner, as well for flexibility to adapt the materials to specific contexts and issues.

Assuming operations in during the COVID pandemic, in the wake of heightened protection and CAMH concerns,3 SAMVAD leveraged technology, through creation of virtual knowledge networks and adaptation of in-person training workshops to online programs, enabling CAMH to permeate to remote districts of the country. In its relatively short tenure so far, it has reached across the country, to cover 1,16,243 (child care) service providers and duty-bearers, through capacity building initiatives and tele-mentoring services, and 26,32,875 stakeholders and citizens (namely parents, teachers, protection functionaries, health workers and other interested parties) through public discourse series, all of which are delivered in diverse Indian languages.

SAMVAD embodies how a tertiary mental healthcare facility, instead of confining itself to the care and treatment of a small population sub-group, can play a critical public health role, integrating CAMH at grassroots and frontline levels of child work, thereby expanding access to quality CAMH support and services. It is an exemplar of a national model for child mental health, one that is replicable and adaptable in LMICs, where child mental health systems are often weak or fragmented, through the convergence of multiple stakeholders—building safety nets and social supports for vulnerable children, and when necessary, enabling access to specialized CAMH services.

Contributors

S.R. contributed to drafting (writing) of the article, including structuring and content; conceptualization of the SAMVAD model and initiation and implementation of the project (as Technical and Operational Lead on the project).

J.V.S. contributed to content of article and corrections to the draft; administration of the SAMVAD project (as Principal Investigator to the project).

S.S. contributed to conceptualization of the SAMVAD model and initiation and implementation of the project (earlier as Principal Investigator and now as Advisor to the project) correction and inputs into content; grammatical & syntax edits; assistance with revisions in accordance with reviewer comments.

Declaration of interests

The resources to implement SAMVAD are supported by the Ministry of Women & Child Development, Government of India. There are no other conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank Aakanksha Kulkarni, Project Officer, SAMVAD, for her assistance with the development of the figure.

Footnotes

The child protection system, constituted under the Juvenile Justice Act of India, specifically under the Integrated Child Protection Scheme, provides programs and services for children living in adverse circumstances. It ensures provision of supplemental or substitute care, to promote well-being of children, through ensuring basic needs of shelter and care, and prevention of neglect, abuse and exploitation. Child protection functionaries comprise of members of Child Welfare Committees and Juvenile Justice Boards, officers of the District Child Protection Unit, and staff for Institutional and non-institutional child care. SAMVAD works with the functionaries within these systems, to integrate CAMH with protection concerns.

SAMVAD's training materials are contained in manuals that are freely accessible on its website.

COVID lockdown restrictions as well as the impact of COVID i.e. loss of employment/family income, and illness and mortality-related issues, placed children at protection risk of child labour, trafficking, neglect and loss of caregivers, also resulting in mental health problems.

References

- 1.Simelane SRN, de Vries PJ. Child and adolescent mental health services and systems in low and middle-income countries: from mapping to strengthening. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2021;34(6):608–616. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kidman R, Piccolo LR, Kohler H-P. Adverse childhood experiences: prevalence and association with adolescent health in Malawi. Am J Prev Med. 2020;58(2):285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murray CJL, Vos T, Lozano R, et al. Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2197–2223. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atilola O. Cross-cultural child and adolescent psychiatry research in developing countries. Glob Ment Health. 2015;2 doi: 10.1017/gmh.2015.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babatunde GB, van Rensburg AJ, Bhana A, Petersen I. Barriers and facilitators to child and adolescent mental health services in low-and-middle-income countries: a scoping review. Glob Soc Welf. 2021;8(1):29–46. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maselko J. Social epidemiology and global mental health: expanding the evidence from high-income to low- and middle-income countries. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2017;4(2):166–173. doi: 10.1007/s40471-017-0107-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vostanis P, Eruyar S, Haffejee S, O'Reilly M. How child mental health training is conceptualized in four low- and middle-income countries. Int J Child Care Educ Policy. 2021;15(1):10. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2021.1982881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juengsiragulwit D. Opportunities and obstacles in child and adolescent mental health services in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the literature. WHO South-East Asia J Public Health. 2015;4(2):110–122. doi: 10.4103/2224-3151.206680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MoWCD . Ministry of Women & Child Development, Government of India; 2018. The Report of the Committee For Analysing Data of Mapping and Review Excercise of Child Care Institutions under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 and Other Homes [Internet] p. 250.https://wcd.nic.in/sites/default/files/CIF%20Report%201.pdf [cited 2020 Dec 15]. Report No.: Volume I. Available from: [Google Scholar]