Abstract

BACKGROUND

The American Heart Association funded a Health Equity Research Network on the prevention of hypertension, the RESTORE Network, as part of its commitment to achieving health equity in all communities. This article provides an overview of the RESTORE Network.

METHODS

The RESTORE Network includes five independent, randomized trials testing approaches to implement non-pharmacological interventions that have been proven to lower blood pressure (BP). The trials are community-based, taking place in churches in rural Alabama, mobile health units in Michigan, barbershops in New York, community health centers in Maryland, and food deserts in Massachusetts. Each trial employs a hybrid effectiveness-implementation research design to test scalable and sustainable strategies that mitigate social determinants of health (SDOH) that contribute to hypertension in Black communities. The primary outcome in each trial is change in systolic BP. The RESTORE Network Coordinating Center has five cores: BP measurement, statistics, intervention, community engagement, and training that support the trials. Standardized protocols, data elements and analysis plans were adopted in each trial to facilitate cross-trial comparisons of the implementation strategies, and application of a standard costing instrument for health economic evaluations, scale up, and policy analysis. Herein, we discuss future RESTORE Network research plans and policy outreach activities designed to advance health equity by preventing hypertension.

CONCLUSIONS

The RESTORE Network was designed to promote health equity in the US by testing effective and sustainable implementation strategies focused on addressing SDOH to prevent hypertension among Black adults.

Keywords: blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, health equity, hypertension, social determinants of health

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

The 2024 American Heart Association’s (AHA) Impact Goal is to advance cardiovascular health for all, including identifying and removing barriers to health care access and quality.1 In 2021, the AHA initiated a series of investments that enhanced its commitment to address the social determinants of health (SDOH) and achieve health equity for all communities. As a key commitment to achieving its 2024 Impact Goal, the AHA is funding Health Equity Research Networks (HERNs) to provide data informing approaches to achieve health equity. The first HERN is focused on the prevention of hypertension.

Elevated blood pressure (BP) and hypertension contribute to more cardiovascular events than any other modifiable risk factors in the United States and worldwide.2 Data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) indicate that less than 30% of 18 year old US adults have elevated BP or hypertension, but this percentage increases with age, such that over 90% of 75 year-old US adults have elevated BP or hypertension.3 In the United States, the incidence and prevalence of hypertension is higher among Black adults compared with those from other race/ethnicity groups. According to NHANES 2017–2020, the age-adjusted prevalence of hypertension was 58.9% among non-Hispanic Black adults compared with 44.7%, 46.5%, and 45.6% among non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Asian, and Hispanic US adults, respectively.4 Additionally, in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, the cumulative incidence of hypertension by 55 years of age was 75.5%, 75.7%, 54.5%, and 40.0% in Black men, Black women, White men, and White women, respectively.5 A substantial proportion of the excess CVD mortality in Black compared to White adults has been attributed to the higher prevalence of hypertension and lower prevalence of BP control among those with hypertension.6

The higher prevalence and incidence of hypertension in Black adults compared with other race/ethnic groups is not biological and is preventable. Data from the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study has indicated that lifestyle factors explain most of the excess risk for hypertension in Black versus White adults.7 Additionally, data from the NHANES have demonstrated that socioeconomic status, social disadvantage and lack of healthcare access are associated with poor hypertension outcomes.8,9 In the United States, Black adults are more likely to live in neighborhoods with extreme deprivation characterized by poor access to healthcare, food insecurity, limited availability of healthy foods, lack of safe places to engage in physical activity, and low health literacy. To achieve health equity, effective strategies must address barriers that hinder the uptake of evidence-based lifestyle interventions to prevent and treat hypertension in these communities.

While treating hypertension with antihypertensive medication reduces the risk for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and mortality, it does not return the risk to the level experienced by people with similar BP levels without the use of antihypertensive medication.10,11 Therefore, preventing the development of hypertension has the potential to avert more CVD events and delay mortality more than relying on treating people once they develop hypertension. Non-pharmacological approaches have been proven to prevent the development of hypertension and lower BP for those with elevated BP and hypertension. These approaches include weight loss; reduced sodium consumption; increased potassium consumption; diets rich in low-fat dairy, fruits, and vegetables; alcohol reduction/cessation; and adequate physical activity.12 These strategies were endorsed by the Joint National Committee (JNC) on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High BP (JNC-5, JNC-6, JNC-7) guidelines and are currently recommended by the 2017 American College of Cardiology (ACC)/AHA BP Guideline.13–16 However, despite proven efficacy and guideline recommendations, implementation of these non-pharmacological interventions is low among US adults.17

THE RESTORE NETWORK

In July 2021, the AHA selected the RESTORE (addREssing Social determinants TO pRevent hypErtension) Network as the HERN to prevent hypertension. The RESTORE Network was established as a collaboration between eight universities (New York University [NYU], University of Alabama at Birmingham [UAB], Columbia University [CU], Johns Hopkins University [JHU], Wayne State University [WSU], Tuskegee University [TU], Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center [BIDMC; a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard Medical School], and University of California at San Francisco [UCSF]). The network was designed with the vision of advancing the science of health equity and investigating approaches to reduce racial inequities in CVD outcomes by translating evidence-based interventions for hypertension prevention into community settings. In this section, we describe factors that informed the vision of the RESTORE Network.

It has been known for decades that population-based strategies that modestly shift the systolic BP (SBP) distribution lower can yield a large reduction in CVD mortality.18 To lower the entire SBP distribution, evidence-based interventions should be implemented in places where people live, work, and play, to maximize their impact on population health. Thus, the RESTORE Network tests approaches for translating evidence-based interventions for hypertension prevention into community settings with high neighborhood deprivation.

The World Health Organization defines social determinants of health (SDOH) as the environments in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks.19 Negative SDOH, such as food insecurity, low health literacy, and neighborhood deprivation, are pervasive in Black communities and have been linked to hypertension and BP control (Figure 1).8,20 While structural in nature, most SDOH are modifiable, as shown by strategies developed and implemented in previous studies by several RESTORE Network investigators. For example, in a cluster-randomized trial of 32 Black churches in New York City that enrolled 400 Black adults with uncontrolled BP, a faith-based lifestyle intervention delivered by community health workers (CHWs) decreased SBP by nearly 6 mm Hg compared with health education control.21 In a cluster randomized trial of 17 Black-owned barbershops in Dallas, Texas among 1,297 Black men with hypertension, a health promotion intervention delivered by barbers and peers resulted in an 8.8% greater hypertension control rate compared with AHA educational pamphlets.22 To date, widespread implementation of strategies addressing SDOH by stakeholders to lower BP is lacking.

Figure 1.

Social Determinants of Health contributing to the high prevalence of hypertension in Black communities.

SPECIFIC AIMS OF THE RESTORE NETWORK

Aim 1. Work with Black communities to achieve health equity in the prevention of hypertension by mitigating the negative impact of SDOH on BP in Black adults.

Aim 2. Develop and evaluate strategies for implementing evidence-based lifestyle interventions, shifting the BP distribution lower for the entire US population, thereby preventing hypertension.

Aim 3. Disseminate findings to policy makers, payers, and stakeholders to ensure sustainability of hypertension prevention strategies in Black communities.

Aim 4. Train the next generation of early-career scientists in health equity and CVD research.

STRUCTURE OF THE NETWORK

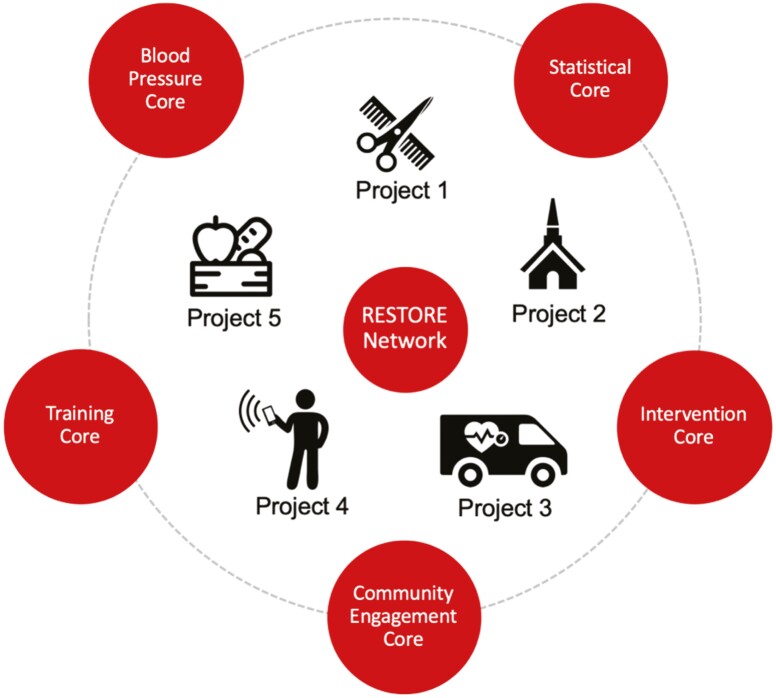

The RESTORE Network is conducting five randomized controlled trials that test the implementation of evidence-based approaches to lower SBP. These trials are being conducted in five different US states by separate investigators, but were explicitly designed to be highly synergistic through their focus on lowering BP and preventing hypertension among adults without hypertension, developing interventions focused on Black adults, implementing interventions in communities with structural barriers to health equity, using a common conceptual framework, collecting and assessing implementation science metrics, employing the same BP measurement protocol, collecting common data elements, and a priori choosing the same primary outcome. Additionally, each of the trials is supported by five cores that focus on standardization (Figure 2). The AHA established an Oversight Advisory Committee, comprising patients and leaders in hypertension and health equity research, to monitor the progress of the network, assist in addressing challenges, and provide guidance on strategies to engage stakeholders and advance the RESTORE Network’s mission.

Figure 2.

Cores and projects that define the RESTORE Network structure.

OVERVIEW OF THE 5 RESTORE NETWORK TRIALS

The following five trials are included in the RESTORE Network and are described in detail in accompanying articles in this American Journal of Hypertension compendium.

The Community-to-Clinic Linkage Implementation Program (CLIP) trial is testing in-barbershop facilitation implementation and scaling of a community-to-clinic linkage program with trained CHWs on SBP in Black men.

The Equity in Prevention and Progression of Hypertension by Addressing barriers to Nutrition and Physical Activity (EPIPHANY) trial is testing church-based peer support from a CHW delivered over the telephone to help set and meet diet and physical activity goals on SBP.

The Linkage, Empowerment, and Access to Prevent Hypertension trial (LEAP-HTN) is testing care delivered remotely by CHWs using an innovative strategy termed PAL2 (Pragmatic, Personalized, Adaptable Approaches to Lifestyle and Life Circumstances) on SBP.

The Home Blood Pressure Telemonitoring Linked with Community Health Workers to Improve Blood Pressure (LINKED-BP) trial is testing the effect of home BP monitoring, BP telemonitoring, and CHW telehealth visits for education and counseling on lifestyle modification on SBP in community health centers.

The Groceries for Black Residents to Stop Hypertension Trial (GO-FRESH) is testing the use of dietician support and a virtual grocery list with weekly Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-compliant food delivery to the homes of Black adults on SBP.

The five projects have access to the City Health Dashboard, an established website designed to propel improvements in population health and health equity by providing reliable measures of health and health determinants at the city and neighborhood levels.23,24 Project investigators are using the dashboard to develop site-specific reports describing local SDOH and hypertension risk factors to target recruitment efforts and facilitate community engagement.

SYNERGY

Synergy is being achieved in the RESTORE Network through the use a common conceptual framework, the evaluation of implementation measures, the collection of common data elements, and the use of five cores to facilitate the use of common protocols, when feasible. These aspects of the RESTORE Network are described below.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

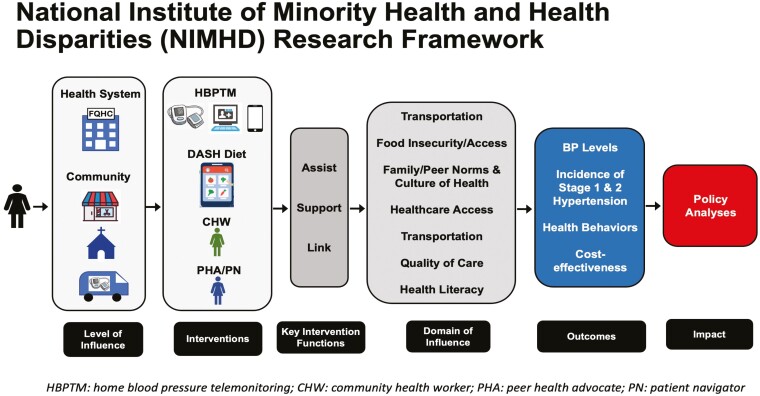

All five RESTORE projects are based on a unifying research framework developed by the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities that conceptualizes factors influencing minority health and health disparities at multiple levels and domains of influence (Figure 3). Each project tests an implementation strategy that engages individuals in the community (e.g., churches, barbershops, mobile vans) or clinical settings (community health centers) and then assists, supports, and links participants to community resources that will help them address domains of influence (e.g., SDOH), adopt lifestyle behaviors, and lower BP. Through this framework, each study will evaluate the level of influence that needs to be addressed to implement interventions in the community.

Figure 3.

RESTORE Network trials applied to the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities research framework. HBPTM, home blood pressure telemonitoring; CHW, community health worker; PHA, peer health advocate; PN, patient navigator.

IMPLEMENTATION SCIENCE MEASURES

Scientific evidence from trials has often failed to lead to meaningful, sustained change in clinical practice, community settings, or health policy—and when change does occur, it may not be experienced equitably. The poor translation of research into practice results from the focus of clinical trials on efficacy, without data being collected and formally evaluated on generalizability and implementation needs. To overcome this limitation, each trial in the RESTORE Network has an aim designed to provide information on the implementation of the program being tested. Evaluation of each implementation strategy in the RESTORE Network will be guided by RE-AIM, an established framework that assesses the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance of evidence-based interventions in clinical and community settings.25–27 RE-AIM outcomes in each project will be collected to allow stakeholders to compare the potential impact of various implementation strategies across diverse settings and assess their potential for translation to other high-risk populations beyond Black adults (Table 1). The factors assessed in the RE-AIM framework are often multi-level and provide information on issues related to the context and generalizability of an intervention.

Table 1.

Descriptions of the domains that comprise the RE-AIM Framework

| Domains | Description |

|---|---|

| Reach | Are we reaching the intended audience? Number of sites and people engaged in the intervention |

| Effectiveness | Is the intervention providing benefits? (clinical outcomes, cost-effectiveness) |

| Adoption | Is there organizational support? Number of sites and providers that utilized the intervention |

| Implementation | Is the program delivered consistently and as intended? |

| Maintenance | Are the intervention and its benefits ongoing? |

OVERVIEW OF THE COORDINATING CENTER

The RESTORE Network coordinating center resides at NYU Langone Health and is responsible for the centralized management and coordination of the scientific, administrative, and financial aspects of the five trials. The coordinating center also oversees the implementation of five Cores that support the trials: (i) Blood Pressure Measurement, (ii) Statistical, (iii) Intervention, (iv) Community Engagement, and (v) Training. As described below, the cores provide scientific expertise, foster synergy, and enhance the comparison of results from the trials.

BLOOD PRESSURE MEASUREMENT CORE

The BP Measurement Core developed a standard protocol for the measurement of BP across all sites, which was adapted from recommendations in the AHA Scientific Statement on BP measurement.28 Each site is using an Omron HEM-907XL device, with three BP measurements obtained at every study visit. One site (JHU, LINKED-BP) is additionally performing home BP monitoring and one site (BIDMC, GO-FRESH) is performing ambulatory BP monitoring. Participants will have their upper arm measured to select the appropriate cuff size. The BP measurement core leaders conducted staff training and certification for each trial prior to initiating recruitment and will monitor the collection of BP data. They will also re-train staff annually and perform additional training as needed. Members of the BP measurement core will provide guidance to the Statistical Core on BP data management, quality assurance procedures, and analysis.

STATISTICAL CORE

The Statistical Core oversees the collection and analysis of data for the RESTORE Network. This core reviewed the statistical power calculations for each trial, developed databases with interfaces for the administration and electronic capture of data in the trials, and created randomization assignments. The Statistical Core coordinated the development of data collection instruments to ensure that a key set of common data elements was collected across the five RESTORE Network trials (Table 2). Beyond the common data elements, the Statistical Core and investigators from the five trials coordinated the collection of other key elements including sociodemographic factors, medical history, anthropometrics, digital and health literacy, stress, discrimination, the AHA’s Life’s Essential 8 and adverse events. The statistical core will monitor data collection and conduct quality control and statistical analyses.

Table 2.

Common data elements in the five RESTORE Network Trials

| CLIP | Trial | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPIPHANY | LEAP-HTN | LINKED-BP | GOFRESH | ||

| Physical activity | IPAQ | IPAQ | Medical Record- Modified Medicare AHC | IPAQ | IPAQ |

| Diet | MEPA | MEPA | N/A | MEPA | FFQ, 24-hour recall |

| Office BP | RESTORE developed form | RESTORE developed form |

RESTORE developed form |

Medical record | RESTORE developed form |

| Quality of Life | SF-12 | SF-12 | SF-12 | SF-12 | SF-12 |

| SDOH | Medicare AHC | Medicare AHC | Medicare AHC | Medicare AHC | Medicare AHC |

| Perceived risk | Heart disease Stroke Hypertension |

Heart disease Stroke Hypertension |

Heart disease Stroke ASCVD Risk Score Hypertension |

Heart disease Stroke Hypertension |

ASCVD Risk Score |

| Depression | PHQ-2 | PHQ-8 | PHQ-2 | PHQ-8 | PHQ-2 |

| Stress | PSS-4 | PSS-4 | PSS-4 | PSS-4 | PSS-4 |

| Social support | Functional Social Support | Functional Social Support |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Sleep | PROMIS + sleep duration | PROMIS + sleep duration | PROMIS + sleep duration | PROMIS + sleep duration | Sleep duration |

| Health Care utilization | 6 questions | 6 questions | 6 questions | 6 questions | 6 questions |

| Discrimination‡ | Kreiger + EDS | Kreiger + EDS | Kreiger + EDS | Kreiger + EDS | Kreiger + EDS |

| Digital literacy | eHEALS | eHEALS | N/A | eHEALS | eHEALS |

| Health literacy | SILS | SILS | N/A | SILS | SILS |

AHC, Accountability Health Communities; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; EDS, Everyday Discrimination Scale; eHEALS, eHealth Literacy Scale; FFQ, Food Frequency Questionnaire; IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire; MEPA, Mediterranean Eating Pattern for Americans; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PROMIS, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; SDOH, Social determinants of health; SF-12, Short-form Health Survey; SILS, Single Item Literacy Screener; N/A, this data element was not collected in the trial.

‡Two questions from the EDS.

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT CORE

The community engagement core works with each trial to operationalize community-based participatory research principles through community-engagement best practices. A Community engagement committee Advisory Board (CAB) has been established and is composed of community members from the sites of all trials; local and national stakeholders from healthcare, business, faith, educational, non-profit and governmental sectors; and project investigators, including investigators from Tuskegee University, a historically Black university. The investigators for each trial consulted with the Community Engagement Core’s leadership and their partners during the protocol-, instrument- and intervention-development stages, asking them to review materials, pilot-test surveys, and provide feedback. This core includes staff from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity, who will support developing a charter, mission, and vision, to guide its activities and initiatives, hosting quarterly CAB meetings, contributing community-related updates to the network’s regular newsletter, and supporting research teams in communicating their results to study participants, community partners, and other community members. The Core will track the number and types of stakeholder engagement, administer post-meeting surveys of the committee CAB to identify areas for improvement, and provide trials with tools to execute their own community engagement plans.

INTERVENTION CORE

The Intervention Core is working with each trial to ensure that requisite data needed to evaluate the adoption and implementation domains of the RE-AIM framework are being collected. The Core will contribute to cross-trial comparisons of the use and effectiveness of RESTORE Network interventions in different communities, and will lead efforts to disseminate implementation strategies shown to be effective. The Intervention Core is also developing new research collaborations to adapt and test hypertension prevention implementation strategies outside RESTORE Network communities. Within the core, a CHW intervention component has been established, which will co-develop research protocols and evaluation tools with CHWs engaged in RESTORE Network trials. This component will also identify, implement, and disseminate best practices for engaging CHWs to support cardiovascular health, and will explore multi-level factors related to CHWs’ integration into healthcare systems.

TRAINING CORE

The Training Core is recruiting AHA HERN fellows and will oversee professional development and training activities. A competitive selection process has been developed to identify post-doctoral fellows and early-stage faculty members with a research focus on hypertension, health equity, implementation science, and community-based participatory research. All trainees will participate as an investigator on a RESTORE Network trial and develop and implement an individual development plan and attend professional development and training workshops on health equity, implementation science, community-based participatory research, team science, compliance training, and grant and manuscript writing. Scholars will be encouraged to conduct their own research project. When possible, trainees will collaborate on trials at other RESTORE Network sites as part of mini-rotations, to gain additional experiential learning and networking. The Training Core will host quarterly meetings with trainees to review their progress and site specific training. The core will also host an annual presentation by the fellows of their progress and work to all RESTORE Network investigators.

ASSESSMENT OF COST EFFECTIVENESS

The health economics team is developing standardized tools to systematically measure intervention costs and participant quality-of-life metrics in each RESTORE Network trial to allow for cost-effectiveness analysis of developed trials that demonstrate efficacy.29 We will use the validated CVD Policy Model to assess alongside-trial cost-effectiveness, project long-term BP and CVD outcomes, and evaluate the cost-effectiveness of implementing interventions more broadly in communities throughout the United States.30–33 We will estimate ten-year and lifetime cost-effectiveness of each RESTORE Network trial intervention arm compared to their corresponding control arm. These analyses will generate estimates of the number of hypertension cases, CVD events and deaths that could be averted or delayed along with healthcare savings from prevented disease, the budget impact associated with large-scale implementation, and sustainability of RESTORE Network interventions in US communities.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The vision of the RESTORE Network extends beyond the five trials that have been funded. The RESTORE Network infrastructure is established and available for future research studies focused on hypertension prevention, prevention of CVD for those with hypertension, and health equity. For example, an early-stage investigator received a career development award to extend the RESTORE Network infrastructure to study a non-pharmacological BP-lowering intervention in adolescents with high BP. The RESTORE Network investigators are also engaging health systems, health departments, and other external stakeholders on initiatives focused on hypertension prevention, and will leverage the City Health Dashboard to disseminate findings on effective implementation approaches to these stakeholders to prevent hypertension in communities across the United States. In 2022, the AHA funded a HERN focused on disparities in maternal-fetal health outcomes. The RESTORE Network has met with the investigators from this HERN and are exploring approaches to catalyze their intellectual and physical resources and build cross-HERN synergy.

CONCLUSION

The AHA funded the RESTORE Network to provide data towards the goal of achieving health equity in the prevention of hypertension. The RESTORE Network will accomplish this goal by developing and evaluating strategies for implementing evidence-based interventions focused on addressing SDOH and removing barriers to lifestyle modifications that could help reduce BP for the US population, disseminating findings, and training scientists in health equity and hypertension and CVD research. The RESTORE Network investigators have established the infrastructure to accomplish these goals and collaborate, with external investigators and community partners, to build a society where every person lives a healthy life free of hypertension and CVD.

Contributor Information

Tanya M Spruill, Department of Population Health, NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Institute for Excellence in Health Equity, NYU Langone Health; New York, New York, USA.

Paul Muntner, Department of Epidemiology, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Collin J Popp, Department of Population Health, NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Institute for Excellence in Health Equity, NYU Langone Health; New York, New York, USA.

Daichi Shimbo, Department of Medicine, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA.

Lisa A Cooper, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Andrew E Moran, Department of Medicine, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA.

Joanne Penko, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, USA.

Chidinma Ibe, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Ijeoma Nnodim Opara, Department of Internal Medicine, Internal-Medicine-Pediatrics Section, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

George Howard, Department of Biostatistics, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Brandon K Bellows, Department of Medicine, Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, New York, USA.

Ben R Spoer, Department of Population Health, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, NYU Langone Health; New York, New York, USA.

Joseph Ravenell, Department of Population Health, NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Institute for Excellence in Health Equity, NYU Langone Health; New York, New York, USA.

Andrea L Cherrington, Department of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, Alabama, USA.

Phillip Levy, Departments of Emergency Medicine and Physiology, Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Yvonne Commodore-Mensah, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Stephen P Juraschek, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Nancy Molello, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Katherine B Dietz, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Deven Brown, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Alexis Bartelloni, Department of Population Health, NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Institute for Excellence in Health Equity, NYU Langone Health; New York, New York, USA.

Gbenga Ogedegbe, Department of Population Health, NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Institute for Excellence in Health Equity, NYU Langone Health; New York, New York, USA.

FUNDING

This study was supported by American Heart Association, 878088.

DISCLOSURE

Phil Levy is PI of LEAP HTN and ACHIEVE GREATER (5P50MD017351). He is the past chair of the Accreditation Oversight Committee of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and a current member of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Oversight Committee, also of the ACC. Dr. Levy is or has served as a consultant for Astra Zeneca, BMS, Bayer Healthcare, Beckman Coulter, Cardionomics, Novartis, Siemens, Roche Diagnostics, Ortho Diagnostics, Siemens, Pathfast, Quidel, UltraSight Medical, and Patient Insight, and has received funding for research from Novartis, Pfizer, Amgen, CardioSounds, and Edwards Lifesciences.

Dr. Collin Popp is a Sports Nutrition Coach for Renaissance Periodization.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lloyd-Jones DM, Elkind M, Albert MA. American Heart Association’s 2024 impact goal: every person deserves the opportunity for a full, healthy life. Circulation 2021; 144:e277–e279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Bull F, Burnett RT, Byers TE, Calabria B, Carapetis J, Carnahan E, Chafe Z, Charlson F, Chen H, Chen JS, Cheng ATA, Child JC, Cohen A, Colson KE, Cowie BC, Darby S, Darling S, Davis A, Degenhardt L, Dentener F, des Jarlais DC, Devries K, Dherani M, Ding EL, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Edmond K, Ali SE, Engell RE, Erwin PJ, Fahimi S, Falder G, Farzadfar F, Ferrari A, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Fowkes FGR, Freedman G, Freeman MK, Gakidou E, Ghosh S, Giovannucci E, Gmel G, Graham K, Grainger R, Grant B, Gunnell D, Gutierrez HR, Hall W, Hoek HW, Hogan A, Hosgood HD, Hoy D, Hu H, Hubbell BJ, Hutchings SJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacklyn GL, Jasrasaria R, Jonas JB, Kan H, Kanis JA, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Khang YH, Khatibzadeh S, Khoo JP, Kok C, Laden F, Lalloo R, Lan Q, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Leigh J, Li Y, Lin JK, Lipshultz SE, London S, Lozano R, Lu Y, Mak J, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Marcenes W, March L, Marks R, Martin R, McGale P, McGrath J, Mehta S, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Micha R, Michaud C, Mishra V, Hanafiah KM, Mokdad AA, Morawska L, Mozaffarian D, Murphy T, Naghavi M, Neal B, Nelson PK, Nolla JM, Norman R, Olives C, Omer SB, Orchard J, Osborne R, Ostro B, Page A, Pandey KD, Parry CDH, Passmore E, Patra J, Pearce N, Pelizzari PM, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Pope D, Pope CA, Powles J, Rao M, Razavi H, Rehfuess EA, Rehm JT, Ritz B, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, Rodriguez-Portales JA, Romieu I, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Roy A, Rushton L, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Sapkota A, Seedat S, Shi P, Shield K, Shivakoti R, Singh GM, Sleet DA, Smith E, Smith KR, Stapelberg NJC, Steenland K, Stöckl H, Stovner LJ, Straif K, Straney L, Thurston GD, Tran JH, van Dingenen R, van Donkelaar A, Veerman JL, Vijayakumar L, Weintraub R, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams W, Wilson N, Woolf AD, Yip P, Zielinski JM, Lopez AD, Murray CJL, Ezzati M, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380:2224–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Muntner P, Jaeger BC, Hardy ST, Foti K, Reynolds K, Whelton PK, Bowling CB. Age-specific prevalence and factors associated with normal blood pressure among US Adults. Am J Hypertens 2022; 35:319–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muntner P, Miles MA, Jaeger BC, Hannon L, Hardy ST, Ostchega Y, Wozniak G, Schwartz JE. Blood pressure control among US Adults, 2009 to 2012 through 2017 to 2020. Hypertension 2022; 79:1971–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Justin Thomas S, Booth JN, Dai C, Li X, Allen N, Calhoun D, Carson AP, Gidding S, Lewis CE, Shikany JM, Shimbo D, Sidney S, Muntner P. Cumulative Incidence of Hypertension by 55 Years of Age in Blacks and Whites: The CARDIA Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018; 7:1–10. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fiscella K, Holt K. Racial disparity in hypertension control: tallying the death toll. Ann Fam Med 2008; 6:497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Howard G, Cushman M, Moy CS, Oparil S, Muntner P, Lackland DT, Manly JJ, Flaherty ML, Judd SE, Wadley VG, Long DL, Howard VJ. Association of clinical and social factors with excess hypertension risk in black compared with white US Adults. JAMA 2018; 320:1338–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Commodore-Mensah Y, Turkson-Ocran RA, Foti K, Cooper LA, Himmelfarb CD. Associations between social determinants and hypertension, stage 2 hypertension, and controlled blood pressure among men and women in the United States. Am J Hypertens 2021; 34:707–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muntner P, Hardy ST, Fine LJ, Jaeger BC, Wozniak G, Levitan EB, Colantonio LD. Trends in blood pressure control among US adults with hypertension, 1999–2000 to 2017–2018. JAMA 2020; 324:1190–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Howard G, Banach M, Cushman M, Goff DC, Howard VJ, Lackland DT, McVay J, Meschia JF, Muntner P, Oparil S, Rightmyer M, Taylor HA. Is blood pressure control for stroke prevention the correct goal? The lost opportunity of preventing hypertension. Stroke 2015; 46:1595–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu K, Colangelo LA, Daviglus ML, Goff DC, Pletcher M, Schreiner PJ, Sibley CT, Burke GL, Post WS, Michos ED, Lloyd-Jones DM. Can antihypertensive treatment restore the risk of cardiovascular disease to ideal levels?: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study and the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). J Am Heart Assoc 2015; 4:1–12. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, Cutler JA, Havas S, Kotchen TA, Roccella EJ, Stout R, Vallbona C, Winston MC, Karimbakas J; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee.; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Primary prevention of hypertension: clinical and public health advisory from The National High Blood Pressure Education Program. JAMA 2002; 288:1882–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, DePalma SM, Gidding S, Jamerson KA, Jones DW, MacLaughlin EJ, Muntner P, Ovbiagele B, Smith SC, Spencer CC, Stafford RS, Taler SJ, Thomas RJ, Williams KA, Williamson JD, Wright JT. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71:2199–2269.29146533 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chobanian A., Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Roccella EJ, Lenfant C, Carter BL, Cohen JD, Colman PJ, Cziraky MJ, Davis JJ, Ferdinand KC, Gifford RW, Glick M, Havas S, Hostetter TH, Kirby L, Kolasa KM, Linas S, Manger WM, Marshall EC, Merchant J, Miller NH, Moser M, Nickey WA, Randall OS, Reed JW, Shaughnessy L, Sheps SG, Snyder DB, Sowers JR, Steiner LM, Stout R, Strickland RD, Vallbona C, Weiss HS, Whisnant JP, Wilson GJ, Winston M, Karimbakas J. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003; 289:2560–2572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carey RM, Cutler J, Friedewald W, Gant N, Hulley S, Iacono J, Maxwell M, McNellis D, Payne G, Shapiro A, Weiss S. The fifth report of the Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC V). Arch Intern Med 1993; 153:9–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roccella EJ. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157:2413–2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Booth JN, Li J, Zhang L, Chen L, Muntner P, Egan B. Trends in prehypertension and hypertension risk factors in US Adults: 1999–2012. Hypertension 2017; 70:275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stamler R. Implications of the INTERSALT study. Hypertension 1991; 17:I-16 to I-20. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.17.1_SUPPL.I16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1. Accessed 7 December 2022.

- 20. Havranek EP, Mujahid MS, Barr DA, Blair I, Cohen MS, Cruz-Flores S, Davey-Smith G, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, Lauer MS, Lockwood DW, Rosal M, Yancy CW. Social determinants of risk and outcomes for cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 132:873–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schoenthaler AM, Lancaster KJ, Chaplin W, Butler M, Forsyth J, Ogedegbe G. Cluster Randomized clinical trial of FAITH (faith-based approaches in the treatment of hypertension) in blacks. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018; 11:e004691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Victor RG, Ravenell JE, Freeman A, Leonard D, Bhat DG, Shafiq M, Knowles P, Storm JS, Adhikari E, Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson PG, Pletcher MJ, Hannan P, Haley RW. Effectiveness of a barber-based intervention for improving hypertension control in black men: the BARBER-1 study: a cluster randomized trial. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:342–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spoer BR, Feldman JM, Gofine ML, Levine SE, Wilson AR, Breslin SB, Thorpe LE, Gourevitch MN. Health and health determinant metrics for cities: a comparison of county and city-level data. Prev Chronic Dis 2020; 17:E137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gourevitch MN, Athens JK, Levine SE, Kleiman N, Thorpe LE. City-level measures of health, health determinants, and equity to foster population health improvement: the city health dashboard. Am J Public Health 2019; 109:585–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health 1999; 89:1322–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, Ory MG, Estabrooks PA. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health 2019; 7:8–16. doi: 10.3389/FPUBH.2019.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health. 2013; 103:e38–e46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muntner P, Shimbo D, Carey RM, Charleston JB, Gaillard T, Misra S, Myers MG, Ogedegbe G, Schwartz JE, Townsend RR, Urbina EM, Viera AJ, White WB, Wright JT. Measurement of blood pressure in humans: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2019; 73:E35–E66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care 1996; 34:220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bibbins-Domingo K, Chertow GM, Coxson PG, Moran A, Lightwood JM, Pletcher MJ, Goldman L. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:590–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bibbins-Domingo K, Coxson P, Pletcher MJ, Lightwood J, Goldman L. Adolescent overweight and future adult coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:2371–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kazi DS, Wei PC, Penko J, Bellows BK, Coxson P, Bryant KB, Fontil V, Blyler CA, Lyles C, Lynch K, Ebinger J, Zhang Y, Tajeu GS, Boylan R, Pletcher MJ, Rader F, Moran AE, Bibbins-Domingo K. Scaling up pharmacist-led blood pressure control programs in black barbershops: projected population health impact and value. Circulation 2021; 143:2406–2408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bryant KB, Moran AE, Kazi DS, Zhang Y, Penko J, Ruiz-Negrón N, Coxson P, Blyler CA, Lynch K, Cohen LP, Tajeu GS, Fontil V, Moy NB, Ebinger JE, Rader F, Bibbins-Domingo K, Bellows BK. Cost-effectiveness of hypertension treatment by pharmacists in black barbershops. Circulation 2021; 143:2384–2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]