Abstract

Background:

The emergence of the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, which causes COVID-19 disease, has been a major public health challenge and an increase in the feeling of uncertainty of the population, who is also experiencing an increase in levels of anxiety and fear regarding the COVID-19 disease.

Objective:

The objective of the study was the construct and criterion validation of the Escala de evaluación de la Ansiedad y MIedo a COVID-19 (AMICO, for its acronym in Spanish) to measure both constructs in the general Spanish population

Methods:

Descriptive study of psychometric validation. A field study was carried out to execute univariate and bivariate analyses, in addition to the exploratory and confirmatory factorial analysis of the scale. For the criteria validity study, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and sensitivity and specificity values were calculated.

Results:

The study sample was composed of 1036 subjects over 18 years of age, who resided in Spain, where 56.3% were women with a mean age of 48.11 years (SD = 15.13). The study of construct validity reported two factors and 16 items, with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.92. The scale was concurrently valid with the used gold standard and obtained sensitivity values of 90.48% and specificity values of 76%.

Conclusions:

The AMICO scale is valid and reliable for assessing the level of anxiety and fear of COVID-19 in the adult Spanish population and is highly sensitive.

Keywords: Fear, anxiety, COVID-19, public health, mental health, instrument development

Background

The new disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is caused by a new coronavirus and has affected all countries worldwide since its first case in Wuhan (China) in December 2019. In this context, the lack of knowledge of the epidemiology of the new disease, as well as the high mortality and infection rates due to the disease, have led to increased concern about the infection in the population, thus mediating the emergence of psychological distress. 1 In addition, the exceptional situation of confinement has had important psychological implications, including depressive symptoms, emotional distress, insomnia, anxiety and feelings of loneliness.2,3

Other epidemics that occurred in earlier historical moments, such as those caused by the plague in the Middle Ages and the one caused by cholera, already involved scenes of panic and fear in the population that suffered them due to the lack of knowledge of the diseases themselves and their catastrophic consequences. 4

In this sense, the construct of fear is defined as a cognitive response to threat, and it is thanks to this response that humans can prepare for and adapt to certain dangers. 5 However, if this state of alertness persists over time, it can lead to the development of physical illnesses and/or psychological disorders, which can also aggravate previous pathologies. 6

In the current situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, different studies describe the negative impact of the pandemic on the mental health of the population, and more specifically, the increased presence of stress, anxiety and depression in people.7–10 It has also been described that these emotional alterations tend to be prolonged over time, and coronaphobia has recently appeared on the scene. In particular, this syndrome is associated with avoidance behaviours, increased anxiety and functional limitation of individuals in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic. 11

Given the context of the emotional impact of the pandemic on the population, and the need for valid tools to specifically assess the presence of fear of COVID-19 (FCV-19), Ahorsu et al. 12 designed the FCV-19 scale. This instrument was developed in a sample of the Iranian population, with the aim of detecting fearful situations that could benefit from specific interventions. 12 Initially, the instrument consisted of 10 items which, after psychometric study, resulted in a 7-item scale, weighed on a single factor, which demonstrated adequate psychometric properties in the Iranian population. 12 After its publication, the FCV-19 has been validated in different countries such as Italy, 13 the United States, 14 Turkey, 15 Paraguay, 16 Poland 17 and Saudi Arabia. 18 In the specific case of Spain, Martínez-Lorca et al. 19 applied its cultural adaptation and validation in a sample of university students from the central part of the country. In their study, they demonstrated that the tool was valid and reliable, with seven items loading on a single factor, although it is worth mentioning that the study sample was under 30 years old and did not represent the entire Spanish population. 19 In addition, they also studied the convergent validity of the Spanish-validated scale by calculating the correlation, which was positive, between the Spanish-validated FCV-19 scale and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). 20 The STAI scale specifically measures the presence of anxiety and is widely validated internationally. It has to be said that expert opinion is that anxiety shares characteristics with fear, although the latter would disappear when the stimulus ceases, and anxiety may be somewhat longer lasting. 21

In a previous study, our research team designed the Escala de evaluación de la Ansiedad y MIedo a COVID-19 (AMICO) scale and made the cross-cultural adaptation. 22 The design of this tool was based on the initial 10 items that were evaluated by a panel of experts in the study by Ahorsu et al. 12 Unlike the FCV-19 scale, the AMICO scale incorporated eight new items that also measured the presence of COVID-19 specific anxiety, as the aim of the research team was to incorporate the construct of anxiety, in addition to fear, into the scale. Thus, the instrument consists of 16 items, and proved to be reliable as a screening tool. 22

The aim of the present study is to develop the construct and criterion validation of the Anxiety and Fear Assessment of COVID-19 – Escala de evaluación de la Ansiedad y MIedo a COVID-19 (AMICO, for its acronym in Spanish) scale by means of a new field study.

Methods

Design

Descriptive cross-sectional and psychometric validation study, based on questionnaires.

Instrument

The COVID-19 Anxiety and Fear Assessment Scale-Escala de evaluación de la Ansiedad y Miedo a COVID-19 (AMICO) was designed following the methodology proposed by Epstein et al. 23 Initially, it was based on the 10 items of the FCV-19 scale, which were evaluated by their panel of experts, prior to the psychometric analyses of that study. 12 With these 10 items, a translation-backtranslation process was implemented, and the cross-cultural adaptation was studied by a panel of experts. It was composed of 10 subjects, professors and researchers from different Spanish universities, with an academic level of Doctor or Official Master, and whose areas of knowledge were public health, family medicine, clinical psychology, nursing and social work. In addition to the 10 items, the panel of experts proposed and agreed, using the Delphi technique, on the consideration of eight new items measuring the anxiety construct. The 18 proposed items were submitted to a new Delphi round, and the analysis of inter-observer agreement obtained an overall value of Kappa = 0.89 (p < 0.05). 22 Following the process of cross-cultural adaptation of the scale, a pilot study was conducted with the final 18-item version. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) finally yielded a dimensional matrix of 16 items and two factors, explaining 64.8% of the variance (KMO test = 0.94; Barlett's test: p = 0.001). The reliability study gave a Cronbach's α value of = 0.92. 22 The response options of the AMICO scale range from 1 to 10 points, where 1 corresponds to ‘strongly disagree’ and 10 to ‘strongly agree’. 22

On the other hand, for the present study, the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, in its Spanish validated version, 24 was also used as a method of comparison with a gold standard. 25 This scale is widely used to assess the level of anxiety in the adult population. Specifically, for the present study, the anxiety-state subscale was used, which assesses the presence of anxiety at the present moment and is composed of 20 items, with a Cronbach's alpha reliability of 0.93 and optimal goodness-of-fit values (root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.07; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) = 0.94; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.93). 24 The STAI has a Likert-type response format with four options (0 = almost never/not at all; 1 = sometimes/sometimes; 2 = quite often/frequently; 3 = a lot/almost always). The score for each subscale ranges from 0 to 60 and is corrected from a standardised score table. 24

Participants

Considering the criterion of 10 subjects per questionnaire item and a 25% success rate in the sample, the required sample size was 200 subjects. 26 However, a total sample of 1038 subjects was obtained, born in Spain and resident in the country, which were the inclusion criteria for the sample.

Non-probabilistic snowball sampling was carried out through social networks (WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter and Linkedin), sending the link to the survey, created using the GoogleForms© application, and an introductory text of the study. In addition, the same text specified the need to give consent for voluntary participation in the study, as well as information about the research team and an email address to ask questions about the study. Once the subject accessed the form, the options of voluntary participation and informed consent had to be compulsorily selected in order to continue with the completion of the survey.

Variables

The questionnaire contained sociodemographic variables (sex, age, country of residence, marital status, employment status and level of study) and the scale variable (18 items of the AMICO scale and the 20 items included in the STAI scale).

Procedure

The study was carried out in two phases: (1) sampling phase, by disseminating the link to the survey and its introductory text, during the months of October and November 2020. All team members actively participated in the dissemination of the study through the social networks of different groups in Spain; (2) data analysis phase, during the months of December 2020 and January 2021.

Data analysis

SPSS Statistics© v26 software was used for the univariate and bivariate descriptive analysis. 27 The normality of the distribution of scores was also analysed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, obtaining a significance of 0.01, indicating non-normality. Based on this result, the Mann-Whitney U, Kruskal-Wallis, Kendall's Tau-b or Spearman's Rho-a tests were used.

To explore the factor structure of the AMICO scale, an EFA was carried out using maximum likelihood and varimax rotation criteria. Items with a weight of less than 0.5 were eliminated. The Kaiser–Guttman criterion was used to determine the number of factors, considering eigenvalues greater than one.28,29

On the other hand, for the study of criterion validity, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was carried out using the AMOS© software. 30 An unweighted least-squares estimation procedure was used, since the observed indicators did not follow a continuous normal distribution.31,32 To assess the goodness of fit of the confirmatory model, the following were used: the penalty function (Chi-squared degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) (values ≤ 3 indicated a good fit); the RMSEA index (values ≤ 0.05 or 0.08 indicated a good fit); the NFI (normalised fit index); CFI; TLI (values ≥ 0.96 indicated a good fit); and the SRMR (normalised root mean square residual) (values ≤ 0.80 indicated a good fit).

Ethical considerations

This study is part of the IMPACTCOVID-19 project, which aims to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the emotional well-being and psychological adjustment of healthcare professionals and the general population in Spain, and which obtained due permission from the Ethics and Research Committee of the Regional Government of Andalusia to be implemented (Ref. PI 036/20).

All subjects in the sample confirmed their voluntary and confidential participation in the study through a specific box, in which they had to check the option ‘I agree to participate’. Otherwise, the application did not allow access to the questionnaire.

In addition, the informed consent form explained that participants could contact the principal investigator, if psychological support after completing the questionnaire was needed. The full name and e-mail address of this contact were provided.

Results

Descriptive analysis

Regarding the online questionnaire filling process, a 100% response rate was obtained, so no subjects were excluded from the sample. Also, the average time required to complete the survey was 14 min.

The total sample consisted of 1036 subjects, over 18 years of age and residing in Spain. Of this sample, 56.3% were women with a mean age of 48.11 years (SD = 15.13). Likewise, 54.82% were married, 29.53% single and 15.65% had another status (divorced, separated, widowed, living as a couple). In addition, 55.5% of the sample was working, 15.2% were unemployed, and 29.4% were in retirement or engaged in household chores. Regarding the academic level, 40.7% of the sample had completed undergraduate studies, 19.3% postgraduate studies, 31.7% Baccalaureate and/or Vocational Training, and 8.3% had completed Primary and/or Secondary studies (Table 1)

Table 1.

Description of the sample profile.

| Total

sample (n = 1038) |

Mean AMICO score | Hypothesis contrast* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 583 (56.3%) | 5.3 | p = 0.01 a |

| Male | 453 (43.7%) | 5.00 | |

| Age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 48.11 (15.13%) | Tau = 0.08 b | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 567 (54.82%) | 5.55 | p = 0.02 c |

| Single | 306 (29.53%) | 5.10 | |

| Other | 163 (16.65%) | 4.15 | |

| Level of studies | |||

| Postgraduate | 421 (40.7%) | 4.84 | p < 0.01 c |

| Degree | 200 (19.3) | 5.33 | |

| Baccalaureate/Vocat. Train. | 329 (31.7%) | 5.66 | |

| Primary and/or Secondary | 86 (8.3%) | 6.00 |

U-Mann Whitney.

Kendall Tau-B.

ANOVA.

*Non-parametric contrast statistics:

The mean score obtained on the AMICO scale was 5.41 points (SD = 1.83), with a score range of 1.22–10.

The bivariate analysis only demonstrated statistically significant differences in the mean score of the scale and the sex, marital status and academic level variables (Table 1). Thus, the group of women had higher levels of anxiety and fear ( = 5.3 points) than men ( = 5 points). In addition, married subjects also had higher levels of anxiety and fear ( = 5.55), followed by people living together as a couple, divorced or widowed ( = 5.10); sample subjects who were single had the lowest levels of anxiety and fear ( = 4.15). On the other hand, subjects with Primary and/or Secondary studies had the highest levels of anxiety and fear ( = 6 points), followed by people who had Baccalaureate or Vocational Training studies ( = 5.66). Subjects in the sample with undergraduate ( = 5.33) and Postgraduate ( = 4.84) studies had the lowest levels of anxiety and fear.

Psychometric analysis

Construct validity and reliability

Through EFA, the dimensional matrix of the 16 items was extracted, as well as two factors explaining 64.8% of the variance (Table 2). No items were removed, as their factorial loads were all > 0.6. The reliability study offered a total value of Cronbach's α = 0.92, of 0.92 for factor 1 (Anxiety) and of 0.90 for factor 2 (Fear).

Table 2.

Exploratory factor analysis.

| Scale items | Factors | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Fear | |

| ITEM_1 | 0.742 | |

| ITEM_2 | 0.659 | |

| ITEM_3 | 0.784 | |

| ITEM_4 | 0.790 | |

| ITEM_5 | 0.768 | |

| ITEM_6 | 0.687 | |

| ITEM_7 | 0.867 | |

| ITEM_8 | 0.857 | |

| ITEM_9 | 0.687 | |

| ITEM_10 | 0.727 | |

| ITEM_11 | 0.710 | |

| ITEM_12 | 0.634 | |

| ITEM_13 | 0.683 | |

| ITEM_14 | 0.640 | |

| ITEM_15 | 0.753 | |

| ITEM_16 | 0.726 | |

A CFA was performed for the study of the construct validity, which offered the following values: CMIN/DF = 1.622 (p = 0.15 = ; NFI = 0.968; TLI = 0.964; CFI = 0.974; RMSEA = 0.06; and SRMR = 0.037 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

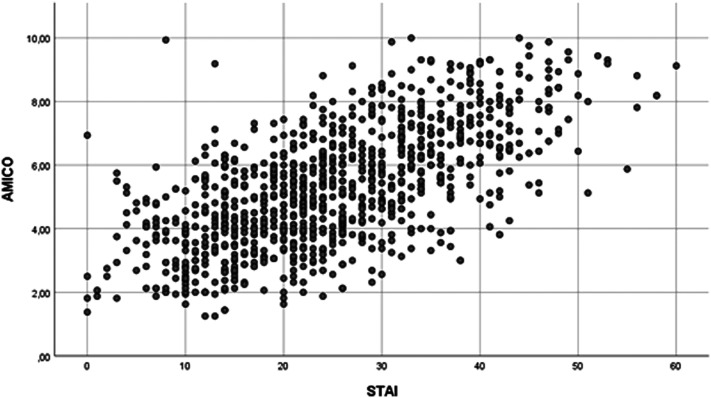

Concurrent validity

As for the validity of concurrent criterion, the AMICO scale and STAI-State questionnaire obtained a Spearman coefficient of 0.726 (p < 0.001), showing concurrent validity with the significant STAI-State scale (Figure 2). In order to study the sensitivity and specificity of the AMICO scale, the area under the curve was calculated and a value of 0.84 (p = 0.008) was obtained. The sensitivity value of the scale was 90.48%, and the specificity value was 76%.

Figure 2.

AMICO and STAI scales concurrent validity.

STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; AMICO: Escala de evaluación de la Ansiedad y MIedo a COVID-19.

Criterion validity

Regarding the criteria validity, by using the STAI questionnaire as a gold standard and considering its scoring scale for a high level of anxiety, a cut-off point of 6.4 was established on the AMICO scale. In addition, based on the distribution of mean scores of the AMICO scale, a score of 4.31 is set in quartile 1, and a score of 6.4 in quartile 2. With this, and the cut-off point obtained by gold pattern, the following correction scale was set for the AMICO scale: low level from 0 to 4.31 points; intermediate level from 4.32 to 6.4 points; high level, with a score greater than 6.4. Figure 3 shows the distribution of the sample at the three anxiety levels proposed, using a box-and-whisker plot.

Figure 3.

Distribution of scores according to anxiety and fear level.

The analysis of the statistical significance of the differences between the different identified levels, by using the U-Mann Whitney statistic for each pair of levels tested, always offered a value of p = 0.001. Thus, there are significant differences between the identified levels, and therefore their consideration and identification can be found in the correction scale of the AMICO scale.

Discussion

The objective of this study was, as discussed above, the validation of a construct and criterion of the AMICO scale to assess fear and anxiety regarding the COVID-19 disease. The obtained results have provided good goodness-of-fit rates as well as a high Cronbach's alpha internal consistency value. It has a final structure of 16 items and two factors, which measure anxiety and fear, respectively, extracted by an exploratory and CFA, which explain 64.8% of the variance. Likewise, the AMICO scale was concurrently valid with the STAI questionnaire, 24 and through its use as a gold standard, a cut-off point of 6.4 points has been obtained for the AMICO scale. With this result, and the distribution of mean scores according to quartiles, the research team made the decision to identify three levels of anxiety/fear. The differences between these were statistically significant, so they can be considered as a scale of results.

The study of the sensitivity of the scale concluded with a percentage of 90.48%. This value indicates that the AMICO scale is highly capable of detecting cases where there is anxiety and FCV-19. However, the scale achieved a specificity of 76%, and this value indicates that the AMICO scale is moderately capable of diagnosing a healthy subject (without the presence of anxiety levels and fear of COVID-19) as non-sick or without anxiety/fear. It may be thought that the scale can be used as a screening tool in the Spanish population, given its high sensitivity, for the detection of subjects with levels of anxiety and FCV-19. It would therefore become a primary and secondary prevention tool, with the aim of detecting the needs of the population regarding mental and public health.

The results of the bivariate analysis show differences between the AMICO scale scores and the sex variable. Thus, women have a higher level of anxiety than men. In this regard, population studies on the prevalence of symptoms of psychological distress and affective disorders in Spain show that females present some sort of mental health problem in 14% of the population, as compared to 7.2% of males. In addition, 6.7% of adults report chronic anxiety, with a higher prevalence again in females (9.1%) than in males (4.3%). 33

The initial design of the AMICO scale was based on the FCV-19 questionnaire created by Ahorsu et al. 12 In this sense, FCV-19 only evaluates the presence of the fear of COVID-19 construct, and has been widely validated in different countries in recent months: United Kingdom, Brazil, Taiwan, Italy, New Zealand, Cuba, Iran, Pakistan, Japan and France. 34 However, the AMICO scale has an added value that differentiates it from the FCV-19 scale, since it not only evaluates the fear construct but also anxiety. 22 In addition, a recent systematic review of the FCV-19 scale validations in different countries concludes that it is necessary to study its sensitivity, specificity and criterion validity, since there is no study that reports these data. 35 On the contrary, in the present study, data are presented about the construct validity and criterion of the AMICO scale.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health should be studied from a social and sex perspective, putting women at the forefront of the disease response. 36 On the one hand, 70% of care tasks fall to women who, with the situation of alarm and confinement and the consequent closure of schools, have experienced an increase in this quantity. This situation, in addition to teleworking at home, caused an emotional overload in the Spanish population. 36

This study also showed significant differences between the AMICO scale scores and the marital status and academic training variables. Thus, the higher the level of training, the lower the levels of anxiety and FCV-19. In addition, married subjects, followed by single subjects, showed higher levels of anxiety. In contrast, divorced participants and/or widowers had low anxiety levels. Recent studies have also reported results that show that the level of academic training favours the search for and identification of relevant and rigorous information in relation to COVID-19, improving the emotional impact of the disease on Spanish subjects. 37 Likewise, it seems sensible to think that married subjects have higher levels of anxiety than single participants and/or widowers, considering that there is a feeling of protection and fear of contagion of cohabitants. 38 In relation to these results, a study by Carreira Capeáns and Facal 39 on the Spanish population also showed higher levels of anxiety in the female group, and lower levels in subjects with higher academic degrees. However, the same authors concluded that married subjects and/or participants living as a couple had lower levels of anxiety, 39 contrary to the results of this study. In addition, on a sample of subjects over the age of 50 years in their study, they also indicated that, at an older age, lower levels of anxiety are shown. On the contrary, in a systematic review by Cisneros and Ausín, 40 it is concluded that the prevalence of anxiety levels in subjects over 65 years of age is 20%, and is above the prevalence in the adult population. 40 However, this study, in relation to the pandemic situation by COVID-19, has shown no significant relationship between the AMICO scale score and the age variable.

In relation to the levels of fear and anxiety regarding COVID-19, a recent study in Colombia showed that 72.9% of the adult population had symptoms of anxiety, of which 37.1% were afraid of COVID-19 disease. 41 The FCV-19 present in the population has also been linked to an increase in the consumption of toxic substances such as alcohol or cannabis. 42 In addition, other studies have revealed the presence of psychological distress, anxiety and work overload among health professionals at the forefront of care for patients with COVID-19, both in Spain and in other countries.43,44 However, these studies have not reported data regarding the levels of FCV-19 in this population.

The results of this study indicated a mean score of 5.41 points, and according to the validated scale, that score results in an average level of anxiety and fear. It therefore indicates that the Spanish population has suffered the emotional impact, in terms of specific anxiety and fear, of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding the relevance of the design of the AMICO scale, and its criterion and construct validation in the present study, there are recent studies that describe the presence of high levels of worry, depression, and anxiety regarding COVID-19 disease in the Spanish population. Moreover, this situation has been related to an increase in psychological distress and seems to be predictive of morbidity in the Spanish population.7,45,46 In this sense, other authors have concluded that subjects with higher levels of anxiety and FCV-19 have greater adherence to protective behaviours and exhibit them more,46,47 although other studies obtain contrary findings.19,20

Other countries have designed intervention programmes to improve public health, as is the case of China. 48 Among the measures proposed are the evaluation of the information offered to the population and the improvement of the social support system, although it is necessary to first know the state of the mental health of the population to design these programmes. In this context, it is necessary to have a reliable tool to assess the levels of anxiety and fear in the Spanish adult population in order to identify and measure the presence of these symptoms so as to implement specific intervention strategies. The proposal of the research team is to use the AMICO scale as a screening tool in the different social and health centres and services in the country, thus allowing the early identification of critical situations. It is worth considering the need to implement specific individual or group interventions, with the ultimate aim of improving the public health of citizens. Moreover, the AMICO scale could also be used as a quality evaluation tool for these specific interventions, as it could be a process and outcome indicator. 49

New studies could be developed that assess the presence of anxiety and FCV-19 in specific groups or in people experiencing certain health situations, like elderly people, children, people with mental health problems, and frailty people. In addition, future studies should study the association of the emotional and mental health impact of COVID-19 on the consumption of toxic substances or other risky behaviours of the Spanish population.

Limitations

Regarding the limitations of the study, non-probabilistic sampling for the selection of participants should be considered, as well as the higher presence of women in the sample. Although it was sought to match the sample size for both sexes, the female group was eventually somewhat larger than that of men. It is then necessary to discuss whether the sex variable could have any impact on the construct validation of the AMICO scale.

Conclusions

The AMICO scale has construct and criterion validity as an instrument for measuring the presence of anxiety and fear related to COVID-19 disease in Spain. It consists of 16 items with a ten-point Likert response. It has also been shown to be highly sensitive for case detection.

The Spanish population has moderate, if relevant, levels of anxiety and fear with respect to COVID-19 disease. There is also the need to evaluate these traits with the AMICO tool in specific groups, and to intervene with interdisciplinary health programmes with the aim of specifically screening and improving the mental and public health of the Spanish population.

Author biographies

Juan Gómez-Salgado, PhD, is a Professor at the University of Huelva (Spain). Specialist in Preventive Medicine and Public Health. Nurse Specialist in Occupational Health and Mental Health.

Regina Allande-Cussó, PhD, RN, is a Lecturer at the Nursing Department of the University of Seville (Spain). Nurse in the Emergency Unit of the Virgen del Rocío University Hospital (Seville).

Carmen Rodríguez-Domínguez, PhD, is a Professor at Department of Psychology, Universidad Loyola Andalucía (Spain).

Sara Domínguez Salas, PhD, is a Professor at Department of Psychology, Universidad Loyola Andalucía (Spain).

Selena Camacho-Martín, MNs, Nurse in Juan Ramón Jiménez Hospital in Huelva (Spain)

Adolfo Romero Ruiz, PhD, RN, Professor at Department of Nursing and Podiatry, Health Sciences School, University of Málaga. Researcher at Instituto de Investigación Biomédica de Málaga (IBIMA) (Spain).

Carlos Ruiz-Frutos, PhD, MD, is a University professor of the Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health at the University of Huelva (Spain). Master of Science in Occupational Medicine, University of London (United Kongdom).

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Carlos Ruiz-Frutos https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3715-1382

Juan Gómez-Salgado https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9053-7730

Regina Allande-Cussóhttps://orcid.org/0000-0001-8325-0838

Sara Domínguez-Salashttps://orcid.org/0000-0002-5666-1487

References

- 1.Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJet al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty 2020; 9: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li X, Dai T, Wang Het al. Clinical analysis of suspected COVID-19 patients with anxiety and depression. Journal of Zhejiang University. Med Sci (Basel) 2020; 49: 203–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiu J, Shen B, Zhao Met al. et al. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry 2020; 33: 19–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Páez D, Fernández I, Martín Beristain C. Catástrofes, traumas y conductas colectivas: procesos y efectos culturales. In: San Juan C. (ed) Catástrofes y ayuda En emergencia: estrategias de evaluación, prevención y tratamiento. Barcelona, Spain: Icaria, 2001, pp.85–148. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck A, Emery G. Anxiety disorders and phobias: a cognitive perspective. NY, USA: Basic Books, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sylvers P, Lilienfeld SO, LaPrairie JL. Differences between trait fear and trait anxiety: implications for psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 2011; 31: 122–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Domínguez-Salas S, Gómez-Salgado J, Andrés-Villas Met al. et al. Psycho-emotional approach to the psychological distress related to the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: a cross-sectional observational study. Healthcare 2020; 8: 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gómez-Salgado J, Domínguez-Salas S, Romero-Martín M, Ortega-Moreno M, García-Iglesias JJ, Ruiz-Frutos C. Sense of coherence and psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Sustain 2020; 12(17): 6855. doi: 10.3390/su12176855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gómez-Salgado J, Andrés-Villas M, Domínguez-Salas S, Díaz-Milanés D, Ruiz-Frutos C. Related health factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020; 17(11): 3947. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17113947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panzeri M, Ferrucci R, Cozza Aet al. et al. Changes in sexuality and quality of couple relationship during the COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson J.COVID-19’s Psychological Impact Gets a Name. Medscape [Internet]. 2020. Available at: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/938253 (Accessed 21 March, 2021).

- 12.Ahorsu DK, Lin CY, Imani V, Saffari M, Griffiths MD, Pakpour AH.The fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 27]. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020; 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soraci P, Ferrari A, Abbiati FA, Del Fante E, De Pace R, Urso A, Griffiths MD. Validation and Psychometric Evaluation of the Italian Version of the Fear of COVID-19 Scale. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020 May 4; 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00277-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perz CA, Lang BA, Harrington R.Validation of the fear of COVID-19 scale in a US College sample [published online ahead of print, 2020 Jun 25]. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020; 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00356-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satici B, Gocet-Tekin E, Deniz ME, Satici SA. Adaptation of the fear of COVID-19 scale: its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020; 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrios I, Ríos-González C, O'Higgins M, et al. Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Fear of COVID-19 scale in Paraguayan population [published online ahead of print, 2021 Feb 2]. Ir J Psychol Med 2021; 1–6. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2021.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilch I, Kurasz Z, Turska-Kawa A. Experiencing fear during the pandemic: validation of the fear of COVID-19 scale in polish. PeerJ 2021; 9: e11263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alyami M, Henning M, Krägeloh CU, Alyami H.Psychometric evaluation of the Arabic version of the fear of COVID-19 scale [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 16]. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020; 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00316-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martínez-Lorca M, Martínez-Lorca A, Criado-Álvarez JJet al. et al. The fear of COVID-19 scale: validation in Spanish university students. Psychiatry Res 2020; 293: 113350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spielberger C, Gorsuch R, Lushene Ret al. et al. STAI: cuestionario de ansiedad estado-rasgo: manual. 8th ed. Madrid, Spain: TEA Ediciones, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomás-Sábado J. Miedo y ansiedad ante la muerte en el contexto de la pandemia de la COVID-19. Rev Enfermería y Salud Ment 2020; 16: 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gómez-Salgado J, Allande-Cussó R, Domínguez-Salas S, García-Iglesias JJ, Coronado-Vázquez V, Ruiz-Frutos C. Design of fear and anxiety of COVID-19 assessment tool in Spanish adult population. Brain Sciences 2021; 11(3): 328. doi: 10.3390/brainsci11030328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein J, Miyuki R, Guillemin F. A review of guidelines for cross-cultural adaptation of questionnaires could not bring out a consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 2015; 68: 435–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ortuño-Sierra J, García-Velasco L, Inchausti Fet al. et al. Nuevas aproximaciones en el estudio de las propiedades psicométricas del STAI. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2016; 44: 83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Streiner D, Geoffrey N, Carney J. Validity. In: Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and Use. 5TH ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2015, pp.227–250. doi: 10.1093/med/9780199685219.001.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox N, Hunn A, Mathers N. Sampling and sample size calculation. In: National Institute for Health Research-Research Design Service, ed. Surveys and questionnaires. UK: Yorkshire and The Humber, 2009, pp.12–24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS statistics for windows. Armonk, New York, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guttman L. Some necessary conditions for common-factor analysis. Psychometrika 1954; 19: 149–161. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaiser HF. A second generation little Jiffy. Psychometrika 1970; 35: 401–415. http://www.springerlink.com/index/4175806177113668.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arbuckle J. AMOS [Computer program]. Chicago: Estados Unidos, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lloret-Segura S, Ferreres-Traver A, Hernández-Baeza Aet al. et al. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. An Psicol 2014; 30: 1151–1169. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prudon P. Confirmatory factor analysis as a tool in research using questionnaires: a critique. Comprehensive Psychology 2015; 4(10): 1–18. doi: 10.2466/03.CP.4.10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos-Lira L. ¿Por qué hablar de género y salud mental? Salud Ment 2014; 37: 75. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CY, Hou WL, Mamun MA, et al. Fear of COVID-19 scale (FCV-19S) across countries: measurement invariance issues. Nurs Open 2021; 8: 1892–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller AE, Himmels JPW, Van de Velde S. Instruments to measure fear of COVID-19: a diagnostic systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2021; 21: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Instituto de la Mujer y para la Igualdad de Oportunidades. La perspectiva de género, esencial en la respuesta a la COVID-19. Madrid, España: Instituto de la Mujer. Ministerio de Igualdad, 2020. p.3. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruiz-Frutos C, Ortega-Moreno M, Allande-Cussó R, Domínguez-Salas S, Dias A, Gómez-Salgado J. Health-related factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among non-health workers in Spain. Saf Sci 2021; 133: 104996. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vásquez G, Urtecho-Osorto ÓR, Agüero-Flores Met al. Salud mental, confinamiento y preocupación por el coronavirus: un estudio cualitativo. Rev Interam Psicol J Psychol 2020; 54: e1333. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carreira Capeáns C, Facal D. Anxiety in a representative sample of the Spanish population over 50 years-old. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2017; 52: 197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cisneros GE, Ausín B. Prevalence of anxiety disorders in people over 65 years-old: a systematic review. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol 2019; 54: 34–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Monterrosa-Castro A, Dávila-Ruiz R, Mejía-Mantilla Aet al. Estrés laboral, ansiedad y miedo al COVID-19 en médicos generales colombianos. MedUNAB 2020; 23: 195–213. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Konstantinov V, Berdenova S, Satkangulova Get al. et al. COVID-19 impact on Kazakhstan university student fear, mental health, and substance use. Int J Ment Health Addict 2020; 9: –7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gómez-Salgado J, Domínguez-Salas S, Romero-Martín M, Romero A, Coronado-Vázquez V, Ruiz-Frutos C. Work engagement and psychological distress of health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nurs Manag 2021; 29: 1016–1025. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahmood QK, Jafree SR, Jalil Aet al. et al. Anxiety amongst physicians during COVID-19: cross-sectional study in Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2021; 21: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodríguez-Rey R, Garrido-Hernansaiz H, Collado S. Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic among the general population in Spain. Front Psychol 2020; 11: 1540. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tee ML, Tee CA, Anlacan JPet al. et al. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. J Affect Disord 2020; 277: 379–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rubin GJ, Wessely S. The psychological effects of quarantining a city. Br Med J 2020; 368: m313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao Y, Sun Y, Meng Set al. et al. 2019-nCoV epidemic: address mental health care to empower society. Lancet 2020; 395: e37–e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005; 83: 691–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]