Abstract

Background/Objective:

Nurses develop the care methods they learn through specific training and this enables them to provide care in a safe, effective and efficient manner. Intensive Care Units (ICU), as complex areas in terms of care, require nurses with specific training. Due to this fact, we set ourselves the objective to validate a questionnaire that detects the training needs of intensive care nurses in Spain.

Methods:

A cross-sectional descriptive study, using an electronic questionnaire, adapted and validated through the Delphi technique, in 85 ICUs in Spain, for which a psychometric analysis is conducted. To explore the dimensions and determine the factorial structure, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) were carried out. Internal consistency was determined through ordinal alpha. The statistical treatment was carried out using the statistical programmes Factor Analysis 10.9.02 and IBM AMOS version 24.

Results:

A total of 568 Spanish intensive care nurses, randomly divided into two samples, participated in the study. The EFA presented a factorial solution with suitable values for both the Kaiser-Meyer-Olsen Index and Bartlett's Sphericity. In the CFA, the model fit achieved close to ideal values with a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) close to values of 0.9. The values of individual reliability, internal consistency and average variance extracted were appropriate for this type of analysis.

Conclusion:

The dimensions detected are close to the construct that encompasses the training needs of ICU nurses. The analyses carried out indicate that there are reasonable realities for incorporating these dimensions into the field of nursing training. This study opens the possibility of incorporating new items to adjust the model to improve the explanatory variables. Our findings help us to understand the dimensions that the training programmes should incorporate.

Keywords: competency-based education, critical care, critical care nursing, nursing education, staff development, nurse clinicians, psychometrics (source: MeSH NLM)

Introduction

Nursing competencies have been approached through different studies as an assessment tool to verify the acquisition of homogeneous training that ensures safety and quality of care by new professionals. This enables, in a specific context, to identify models that ensure suitable professional training levels or detecting the areas that require adopting specific educational programmes. 1 This fact is of special interest for nurses and also for health managers, who can implement educational measures that develop and ensure quality care in the different health services, promoting synergies between the different health team members. 2 The critical care nurses need to know what dimensions make up the reality of their training in a reliable and valid way. 3

However, it must be taken into account that acquiring skills is no guarantee for success, but a proven ability to carry out activities for which a certain level of training is required. In this sense, the acquisition of generic competencies enhances the employability of graduates, 4 but it must be considered that in certain healthcare environments, such as critical care areas, professionals show a deficit in certain specific and disciplinary competencies.5,6 To achieve these, different training programmes have been developed for ICU nurses to ensure care according to needs required by critical patients5–7. The possibility of professional development and the opportunity to receive specific training for critical care areas are an attraction that makes it easier to attract and retain nurses and preserve their loyalty. 8

For this reason, the European Federation of Critical Care Nurse Association (EfCCNa) has developed a series of international consensus documents to ensure common training requirements, within the different domains that nurses incorporate in their daily practice, to treat the patient holistically. 9

The effectiveness of critical care training is proven by studies that endorse the need for quality care. 10 Therefore, it is necessary to be able to validate instruments that make it possible to assess the training needs of nurses in their different professional fields.11,12 To this end, scales have been validated through psychometric studies using factor analysis13–15. These analyses enable to compare nursing populations and help to create a reality on which to develop specific competencies in each particular area. 16

In the specific case of the ICU, being able to rely on properly trained nurses is of great interest, not only for them as a disciplinary group, but also for health managers who can thus ensure that care is being provided on the basis of the best scientific evidence available, adapting the skills, capacities and abilities of their own staff to obtain the best care results. 14

Therefore, our research has the purpose to validate a questionnaire that detects the training needs of intensive care nurses in Spain.

Methods

Design

A cross-sectional descriptive study, conducted on a national level, using an electronic questionnaire. This study was distributed to 85 ICUs belonging to 79 hospital centres in Spain.

Sample/ participants

The analysis of the centres and ICU nurses in each unit was previously collected to calculate the sample size. The number of nurses in each unit was provided by the collaborators. Total population of nurses in the participant units was 2965. After performing the calculations through an excel database, this determined the need to collect at least 500 valid questionnaires to ensure a significance level of 95% with a 4% margin of error. In order to determine the sample size, we also followed the conditions established by Lloret-Segura et al. 17 for factorial analysis. Therefore, a sample of at least 200 questionnaires was necessary to be able to perform an adequate factor analysis. For both the Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis, the sample was randomly divided 50/50.

Data collection

The questionnaire was distributed by the collaborators of each centre included in the project during the period from 31st October 2017 to 31st October 2018.

Instrument

The questionnaire was adapted and validated by a group of experts who used a modified Delphi method. 18 This instrument consisted of 66 items which explored, on the one hand, the four EfCCNa domains (Clinical domain (18 items), Professional domain (14 items), Management domain (16 items) and Educational and Development domain (6 items). On the other hand, the method consisted of a section on staff training for ICU (12 items). The nurses’ training needs were checked by means of a Likert type scale (1 to 10 points), on which the value of 1 represented “unimportant, or in disagreement with the statement given” and the value of 10 stood for “very important or totally in agreement with the statement given”.

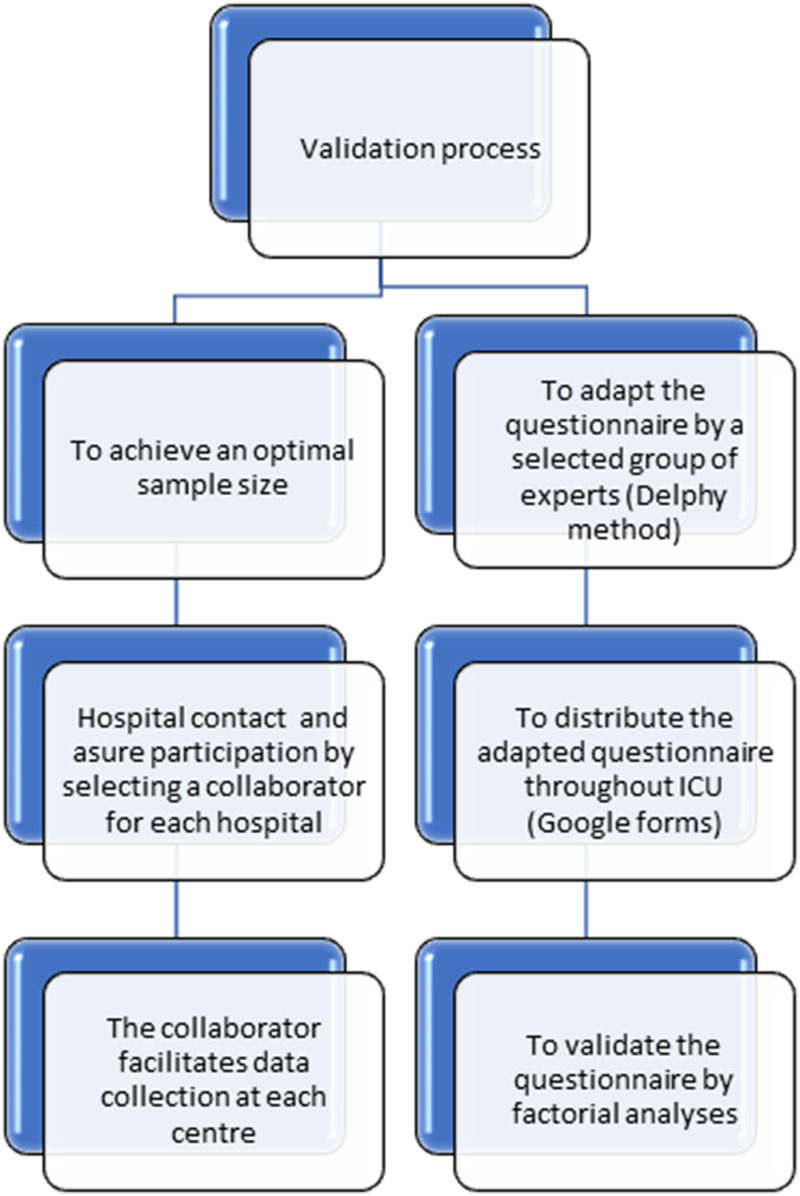

Moreover, social and demographic variables were incorporated (age, gender, years of work experience, academic level); the characteristics of the hospital centres (type of management, relation with the university, number of hospital beds), and of the organisation of the ICU (type of ICU, number of beds, nurse-to-patient ratio). The support for the online distribution of the survey was the Google form platform. Each part of the questionnaire was written in its own section. The questionnaire was pre-tested to verify that there were no comprehension problems with the items. The steps followed in the research are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Investigation procedure.

Ethical considerations

The study was conducted following the ethical and legal principles of biomedical research 14/2007 and the EU regulation 2016/679 on confidentiality. The ethical committee of the main researcher authorised the study with the code Las Palmas: 2018-080-1/1016. In addition, 15 centres requested approval from their own ethical committees of the investigation. Each centre authorised the distribution of the questionnaire among their nurses by requesting their prior consent while ensuring the anonymity of the participants.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Accept affirmatively the informed consent expressed at the beginning of the questionnaire. Since it was explored through an electronic questionnaire and with the aim of ensuring non-automatic responses, two control questions were included throughout the questionnaire. After items 22 and 43, the control questions were included. After items 22 was worded as follows: “If you are filling in this survey accurately, please tick answer five in this item (control question)”. After question 43, it had the same wording but, in this question, we requested that answer number 3 was ticked.

Statistical analysis

In order to explore the dimensions and determine their factorial structure, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was carried out using polychoric matrices. These matrices arise from the fact that there are latent variables or common factors that explain the answers of a test. 19 The extraction method used was Unweighted Least Squares (ULS) with Promin rotation and the optimal factor implementation was developed through the Parallel Analysis (PA) method. 20 To increase the accuracy of the questionnaire, items with factor saturation below 0.40 were removed. Internal consistency and content validity were maintained at all times, and at least 3 items per factor were ensured to be considered a valid response. For the labelling of each factor, the link between all elements that constitute each factor was maintained. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olsen Index (KMO), Bartlett's Sphericity and Kelly Criterion (KC) tests of suitability were applied. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed using the Unweighted Least Squares (ULS) test and the following goodness-of-fit measures were applied: Chi-Square values with respect to the experimental factor Χ2/df, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), as suggested by other studies. 21

The statistical treatment was carried out using the statistical programmes Factor Analysis 10.9.02 and IBM AMOS version 24.

Validity and reliability

Cronbach′s alpha values in these kind of studies are reported to be between 0.78 and 0.91, 13 0.80–0.91 22 and 0.78–0.91. 12 In the present study, which is a novel analysis of the Spanish reality where this kind of study has not been previously carried out. We have considered important to give confidence and replicability to the study to incorporate the general and ordinal Cronbach's alpha of the general construct and the factorials individually. For the analysis of individual reliability, we used the standardised estimators and for internal consistency: Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability; in addition to the Average Variance Extracted (AVE). This study was performed in Spanish. To guarantee the rigour of this study, a professional translator carried out the translation process of all the sections of this research.

Results

A total of 630 questionnaires were received, of which 62 were excluded due to failing some of the control questions. Therefore, the sample consisted of 568 questionnaires. The characteristics of the participant nurses are shown in Table 1. Women comprised the majority with a total of 426 nurses (81.30%), and 409 (72%) being over 36 years old. Of the nurses consulted, 52.11%, i.e. 296, had only a nursing degree certificate, and the rest had several postgraduate studies. 76.05% (432) reported a total work experience as nurses of > 11 years, while 376 nurses (66.20%) had > 6 years’ experience in ICUs. The majority worked in publicly managed hospitals 520 (91.54%), 491 nurses worked in university hospitals (86.44%) and 287 nurses (50.33%) worked in hospital centres with over 500 beds.

Exploratory Factor Analysis.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics.

| Items (n = 568) |

Frequency | Percentage (%) | Items (n = 568) |

Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 22–25 yo | 19 | 3.35 | Sex | Male | 106 | 18.7 | |||

| 26–30 yo | 50 | 8.80 | ||||||||

| 31–35 yo | 90 | 15.85 | ||||||||

| 36–40 yo | 146 | 25.70 | Female | 462 | 81.3 | |||||

| 41–45 yo | 117 | 20.60 | ||||||||

| Over 45 yo | 146 | 25.70 | ||||||||

| Academic Degrees | University Degree | 296 | 52.11 | |||||||

| University Expert | 95 | 16.73 | ||||||||

| Non-Official Master | 90 | 15.85 | ||||||||

| Official University Master | 79 | 13.90 | ||||||||

| Doctorate | 8 | 1.41 | ||||||||

| Professional experience as a Nurse | Less than 1 year | 2 | 0.35 | Professional experience as an ICU Nurse | Less than 1 year | 20 | 3.52 | |||

| 1–5 years | 50 | 8.80 | 1–5 years | 172 | 30.28 | |||||

| 6–10 years | 84 | 14.79 | 6–10 years | 138 | 24.30 | |||||

| 11–15 years | 130 | 22.89 | 11–15 years | 96 | 16.90 | |||||

| 16–20 years | 124 | 21.83 | 16–20 years | 61 | 10.74 | |||||

| 21–25 years | 75 | 13.21 | 21–25 years | 42 | 7.39 | |||||

| More than 25 years | 103 | 18.13 | More than 25 years | 39 | 6.87 | |||||

| Participants according to the number of beds | Less than 200 beds | 61 | 10.74 | Management type | Public management | 520 | 91.55 | |||

| 200–500 beds | 220 | 38.73 | Mixed management | 27 | 4.76 | |||||

| More than 500 beds | 287 | 50.53 | Private management | 3.69 | 3.69 | |||||

| Structure of the intensive care unit | Cardiology and Coronary unit | 38 | 6.69 | |||||||

| Intermediate care | 5 | 0.88 | ||||||||

| Medical intensive care unit | 28 | 4.93 | ||||||||

| Pediatric intensive care unit | 47 | 8.27 | ||||||||

| Polyvalent intensive care unit | 405 | 71.30 | ||||||||

| Surgical intensive care unit | 30 | 5.28 | ||||||||

| Burn intensive care unit | 3 | 0.53 | ||||||||

| Respiratory intensive care unit | 3 | 0.53 | ||||||||

| Trauma intensive care unit | 9 | 1.59 | ||||||||

Note: Results expressed in frequency and percentage. yo = years old.

The sample was randomly divided into two groups (n = 284), one used for the EFA and the other for the CFA, with no significant differences between the two groups in demographic variables such as gender or age. Thus, in the EFA, the PA indicated that the number of factors greater than the unit corresponded to a factorial solution of 13 factors for the 66 items studied. As shown in Table 2, where the EFA data are included, the KMO Index and Bartlett's Sphericity suggest that the dimensionality of the scale should be reduced. The EFA values also determined correct internal consistency values with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.934. The GFI gives appropriate values, and when comparing the RMSR it was lower than the KC value. This finding indicates an appropriate model (see table 2).

Table 2.

Results of the exploratory factor analysis.

| Items | COM | FAC1 | FAC2 | FAC3 | FAC4 | FAC5 | FAC6 | FAC7 | FAC8 | FAC9 | FAC10 | FAC11 | FAC12 | FAC13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The help and support from colleagues with more experience helps to solve problems in complex situations | 0.631 | 0.732 | 0.583 | 0.291 | 0.325 | 0.269 | 0.306 | 0.273 | 0.305 | 0.112 | 0.592 | 0.171 | 0.205 | 0.024 |

| Observation is a necessary tool for obtaining data in the assessment of the critically ill patient | 0.709 | 0.731 | 0.566 | 0.410 | 0.264 | 0.323 | 0.329 | 0.547 | 0.388 | 0.050 | 0.449 | 0.268 | 0.258 | 0.127 |

| ICU nurses need to develop specific skills for critical patient care | 0.677 | 0.726 | 0.509 | 0.458 | 0.338 | 0.228 | 0.255 | 0.369 | 0.308 | 0.014 | 0.300 | 0.191 | 0.135 | 0.023 |

| To prevent unnecessary noises, dim lights or lower the volume of alarms are actions that promote rest for the critically ill patient | 0.716 | 0.722 | 0.712 | 0.149 | 0.294 | 0.412 | 0.234 | 0.381 | 0.419 | 0.075 | 0.603 | 0.353 | 0.185 | 0.119 |

| The nurses are able to plan interventions over the course of their work shift | 0.641 | 0.684 | 0.648 | 0.289 | 0.273 | 0.368 | 0.265 | 0.284 | 0.576 | 0.097 | 0.521 | 0.341 | 0.301 | 0.057 |

| Empathy and respect for privacy are essential for ICU nurses | 0.744 | 0.660 | 0.652 | 0.310 | 0.173 | 0.532 | 0.194 | 0.625 | 0.482 | 0.019 | 0.396 | 0.303 | 0.219 | 0.096 |

| Nurses can cope with complex decisions as a result of the work experience they have obtained in the ICU | 0.607 | 0.633 | 0.311 | 0.349 | 0.265 | 0.381 | 0.343 | 0.150 | 0.172 | 0.277 | 0.471 | 0.103 | 0.008 | 0.208 |

| In an ICU, it is essential that the nurses have the ability to adapt in urgent and emerging situations | 0.509 | 0.610 | 0.549 | 0.334 | 0.278 | 0.334 | 0.441 | 0.232 | 0.345 | 0.022 | 0.520 | 0.205 | 0.122 | 0.080 |

| Comprehensive care of a critically ill patient is part of the nurse's main area of action | 0.548 | 0.590 | 0.543 | 0.509 | 0.280 | 0.379 | 0.218 | 0.371 | 0.394 | 0.113 | 0.381 | 0.244 | 0.260 | 0.119 |

| Critical care teams in ICUs are able to conduct their work in a stressful and pressurised environment | 0.625 | 0.560 | 0.512 | 0.229 | 0.244 | 0.299 | 0.495 | 0.206 | 0.552 | 0.106 | 0.492 | 0.484 | 0.152 | 0.031 |

| To register the care given is the best measure possible to ensure continuity | 0.684 | 0.514 | 0.762 | 0.379 | 0.271 | 0.388 | 0.193 | 0.412 | 0.332 | 0.101 | 0.462 | 0.247 | 0.039 | 0.232 |

| The main communication tools are assertiveness, empathy and active listening with users and families, in addition to professionals | 0.674 | 0.581 | 0.757 | 0.385 | 0.234 | 0.462 | 0.377 | 0.463 | 0.462 | 0.097 | 0.584 | 0.322 | 0.118 | 0.007 |

| Verbal and non-verbal language are essential in ICU communication | 0.674 | 0.684 | 0.755 | 0.302 | 0.337 | 0.495 | 0.302 | 0.399 | 0.383 | 0.032 | 0.506 | 0.255 | 0.108 | 0.052 |

| Monitoring of the care that the nurses provide is indispensable for the continuity and assessment of patient care | 0.652 | 0.525 | 0.746 | 0.381 | 0.269 | 0.396 | 0.429 | 0.411 | 0.337 | 0.084 | 0.491 | 0.244 | 0.048 | 0.099 |

| Regular training is necessary to ensure clinical safety | 0.640 | 0.539 | 0.677 | 0.496 | 0.390 | 0.484 | 0.512 | 0.335 | 0.358 | 0.080 | 0.539 | 0.273 | 0.165 | 0.011 |

| Written communication in ICUs must always be encouraged, as it is essential for the continuity of care | 0.583 | 0.474 | 0.646 | 0.375 | 0.261 | 0.387 | 0.220 | 0.420 | 0.348 | 0.138 | 0.542 | 0.312 | 0.024 | 0.239 |

| A good coordination of the health team is essential | 0.596 | 0.585 | 0.638 | 0.438 | 0.271 | 0.387 | 0.347 | 0.305 | 0.332 | 0.010 | 0.463 | 0.273 | 0.279 | 0.214 |

| In stressful situations, nurses must communicate in a technical, concise and clear manner, adjusting the information to the characteristics of the speaker | 0.564 | 0.538 | 0.615 | 0.297 | 0.291 | 0.363 | 0.455 | 0.329 | 0.377 | 0.115 | 0.501 | 0.306 | 0.108 | 0.051 |

| ICU nurses should be trained in the care of different types of shock | 0.672 | 0.231 | 0.232 | 0.764 | 0.391 | 0.287 | 0.321 | 0.291 | 0.161 | 0.341 | 0.301 | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.289 |

| The ability to prioritise is an essential skill | 0.651 | 0.395 | 0.490 | 0.739 | 0.350 | 0.273 | 0.251 | 0.179 | 0.294 | 0.072 | 0.468 | 0.218 | 0.081 | 0.198 |

| Clinical reasoning (what is happening and what can happen) should be encouraged in ICU nurses | 0.648 | 0.135 | 0.371 | 0.738 | 0.334 | 0.455 | 0.358 | 0.316 | 0.174 | 0.152 | 0.293 | 0.217 | 0.011 | 0.218 |

| Data integration and interrelation is a very important skill for ICU nurses | 0.674 | 0.334 | 0.301 | 0.694 | 0.289 | 0.440 | 0.301 | 0.556 | 0.223 | 0.155 | 0.408 | 0.165 | 0.050 | 0.127 |

| Calculation of drugs and medicines is an essential skill | 0.651 | 0.099 | 0.149 | 0.686 | 0.313 | 0.304 | 0.103 | 0.129 | 0.207 | 0.365 | 0.117 | 0.014 | 0.050 | 0.461 |

| Continual reassessment is the main measure that nurses must implement, in order to assess improvement strategies in the nursing care plan. | 0.615 | 0.544 | 0.592 | 0.596 | 0.219 | 0.417 | 0.363 | 0.456 | 0.379 | 0.157 | 0.493 | 0.292 | 0.085 | 0.193 |

| Decisions regarding patient care are very complex and require extensive training | 0.536 | 0.489 | 0.314 | 0.556 | 0.385 | 0.409 | 0.430 | 0.193 | 0.181 | 0.146 | 0.366 | 0.149 | 0.090 | 0.150 |

| ICU nurses must have extensive knowledge of basic nursing | 0.583 | 0.529 | 0.389 | 0.534 | 0.229 | 0.152 | 0.304 | 0.284 | 0.127 | 0.060 | 0.180 | 0.148 | 0.047 | 0.186 |

| The first week, new nurses must be supervised at all times | 0.692 | 0.363 | 0.338 | 0.356 | 0.788 | 0.302 | 0.267 | 0.248 | 0.258 | 0.146 | 0.377 | 0.171 | 0.186 | 0.231 |

| There should be a nurse tutor in the unit to help new nurses | 0.647 | 0.254 | 0.345 | 0.457 | 0.742 | 0.311 | 0.260 | 0.236 | 0.113 | 0.152 | 0.258 | 0.021 | 0.008 | 0.344 |

| Previous postgraduate ICU training is necessary for new nurses | 0.623 | 0.215 | 0.105 | 0.348 | 0.725 | 0.258 | 0.128 | 0.078 | 0.086 | 0.106 | 0.221 | 0.187 | 0.165 | 0.191 |

| The training must end with a real intervention, always under the supervision of an experienced professional | 0.658 | 0.232 | 0.242 | 0.402 | 0.660 | 0.478 | 0.495 | 0.289 | 0.164 | 0.119 | 0.329 | 0.191 | 0.086 | 0.121 |

| The training must be supported by theoretical and practical events and simulation, before putting this knowledge into practice | 0.662 | 0.448 | 0.467 | 0.342 | 0.642 | 0.578 | 0.422 | 0.411 | 0.309 | 0.115 | 0.400 | 0.180 | 0.145 | 0.058 |

| A newly incorporated nurse should have knowledge on haemodynamics, mechanical ventilation, basic and advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation, in addition to monitoring | 0.640 | 0.505 | 0.516 | 0.398 | 0.600 | 0.377 | 0.123 | 0.122 | 0.467 | 0.145 | 0.522 | 0.146 | 0.057 | 0.079 |

| ICU nurses need to develop emotional intelligence | 0.660 | 0.469 | 0.508 | 0.376 | 0.413 | 0.756 | 0.253 | 0.210 | 0.329 | 0.049 | 0.494 | 0.219 | 0.048 | 0.136 |

| Nurses need specific training to cope with patients' death | 0.645 | 0.061 | 0.160 | 0.319 | 0.285 | 0.713 | 0.100 | 0.211 | 0.094 | 0.115 | 0.061 | 0.028 | 0.081 | 0.259 |

| ICU nurses should develop the following skills: to be calm, methodical and decisive | 0.698 | 0.664 | 0.610 | 0.277 | 0.399 | 0.674 | 0.232 | 0.295 | 0.373 | 0.009 | 0.561 | 0.268 | 0.153 | 0.007 |

| Empathy is an essential attitude to develop within the health team | 0.696 | 0.569 | 0.626 | 0.341 | 0.357 | 0.653 | 0.388 | 0.437 | 0.400 | 0.045 | 0.531 | 0.317 | 0.181 | 0.078 |

| Veteran personnel require specific annual training programmes | 0.580 | 0.405 | 0.466 | 0.229 | 0.496 | 0.589 | 0.282 | 0.269 | 0.202 | 0.052 | 0.322 | 0.204 | 0.006 | 0.160 |

| How users confront death will depend on the beliefs, experiences and values of the nursing staff | 0.483 | 0.128 | 0.098 | 0.278 | 0.079 | 0.453 | 0.241 | 0.064 | 0.207 | 0.205 | 0.249 | 0.201 | 0.265 | 0.325 |

| ICU nursing professionals, within their competence, seek excellence at the clinical level | 0.505 | 0.336 | 0.317 | 0.307 | 0.140 | 0.308 | 0.584 | 0.183 | 0.370 | 0.280 | 0.433 | 0.295 | 0.128 | 0.141 |

| Extensive and specific training in critical care makes it easier for professionals to reach their degree of excellence | 0.699 | 0.566 | 0.495 | 0.310 | 0.521 | 0.507 | 0.568 | 0.490 | 0.328 | 0.051 | 0.462 | 0.232 | 0.207 | 0.076 |

| ICU nurses must be able to act quickly in the event of patient deterioration and adverse events | 0.651 | 0.536 | 0.549 | 0.444 | 0.297 | 0.314 | 0.560 | 0.211 | 0.381 | 0.070 | 0.558 | 0.267 | 0.225 | 0.052 |

| New staff must be incorporated slowly and progressively | 0.514 | 0.323 | 0.447 | 0.211 | 0.457 | 0.395 | 0.471 | 0.228 | 0.069 | 0.138 | 0.324 | 0.065 | 0.042 | 0.133 |

| The use of scales is required to assess critically ill patients | 0.650 | 0.312 | 0.386 | 0.318 | 0.287 | 0.330 | 0.143 | 0.750 | 0.325 | 0.144 | 0.244 | 0.215 | 0.123 | 0.181 |

| The patient and the family have to be involved in the recovery process | 0.634 | 0.436 | 0.525 | 0.383 | 0.191 | 0.546 | 0.228 | 0.677 | 0.353 | 0.019 | 0.426 | 0.330 | 0.083 | 0.017 |

| Observing, analysing and interpreting situations and/or problems in a critically ill patient is necessary to perform a physical examination. | 0.676 | 0.500 | 0.448 | 0.543 | 0.229 | 0.442 | 0.363 | 0.671 | 0.332 | 0.102 | 0.461 | 0.215 | 0.151 | 0.017 |

| Information and communication technologies (ICTs) are essential tools for training, learning and professional development | 0.613 | 0.323 | 0.542 | 0.389 | 0.364 | 0.362 | 0.318 | 0.593 | 0.293 | 0.087 | 0.514 | 0.392 | 0.050 | 0.114 |

| Monitoring is a fundamental tool for obtaining data in the assessment of the critically ill patient | 0.640 | 0.540 | 0.373 | 0.245 | 0.311 | 0.175 | 0.254 | 0.538 | 0.434 | 0.337 | 0.370 | 0.300 | 0.019 | 0.111 |

| Quality indicators are monitored | 0.841 | 0.344 | 0.354 | 0.143 | 0.097 | 0.278 | 0.082 | 0.271 | 0.886 | 0.021 | 0.320 | 0.461 | 0.093 | 0.074 |

| Nurses working in ICU collect data related to quality indicators | 0.784 | 0.313 | 0.327 | 0.284 | 0.212 | 0.337 | 0.165 | 0.323 | 0.851 | 0.095 | 0.309 | 0.349 | 0.060 | 0.096 |

| ICU nurses are involved in clinical safety | 0.650 | 0.276 | 0.436 | 0.335 | 0.116 | 0.241 | 0.527 | 0.214 | 0.615 | 0.166 | 0.279 | 0.302 | 0.074 | 0.044 |

| Respiratory care is a priority that ICU nurses need to develop | 0.725 | 0.081 | 0.136 | 0.234 | 0.123 | 0.164 | 0.192 | 0.095 | 0.217 | 0.820 | 0.151 | 0.259 | 0.068 | 0.077 |

| The main pathologies that an ICU nurse must know are cardiovascular, respiratory and neurological | 0.685 | 0.248 | 0.276 | 0.255 | 0.243 | 0.223 | 0.200 | 0.115 | 0.223 | 0.759 | 0.332 | 0.145 | 0.050 | 0.128 |

| The support measures are the fundamental pillar of the nurses’ activities | 0.776 | 0.130 | 0.027 | 0.543 | 0.180 | 0.035 | 0.182 | 0.098 | 0.062 | 0.686 | 0.000 | 0.119 | 0.184 | 0.376 |

| Nurses cope worse with futile care | 0.640 | 0.396 | 0.491 | 0.234 | 0.323 | 0.340 | 0.156 | 0.062 | 0.304 | 0.080 | 0.752 | 0.165 | 0.073 | 0.095 |

| Nurses should participate in decisions to limit vital support (therapeutic effort) | 0.595 | 0.435 | 0.508 | 0.261 | 0.235 | 0.440 | 0.243 | 0.339 | 0.373 | 0.026 | 0.724 | 0.185 | 0.166 | 0.060 |

| ICU nurses usually deal well with the decision to limit vital support (therapeutic effort) | 0.594 | 0.290 | 0.237 | 0.291 | 0.154 | 0.132 | 0.298 | 0.256 | 0.241 | 0.119 | 0.700 | 0.247 | 0.074 | 0.017 |

| Appropriate actions for the comfort and rest of patients are encouraged | 0.802 | 0.330 | 0.301 | 0.070 | 0.161 | 0.159 | 0.195 | 0.123 | 0.283 | 0.107 | 0.256 | 0.865 | 0.087 | 0.020 |

| In ICUs, measures are taken to help prevent or avoid delirium or confusion | 0.752 | 0.129 | 0.149 | 0.206 | 0.077 | 0.221 | 0.144 | 0.196 | 0.316 | 0.146 | 0.229 | 0.835 | 0.007 | 0.138 |

| Workload for the ICU nurses is managed appropriately | 0.524 | 0.114 | 0.128 | 0.032 | 0.011 | 0.021 | 0.111 | 0.001 | 0.261 | 0.227 | 0.134 | 0.498 | 0.453 | 0.162 |

| The completion of this training depends on the nurse's motivation | 0.673 | 0.017 | 0.024 | 0.223 | 0.244 | 0.168 | 0.229 | 0.079 | 0.161 | 0.093 | 0.199 | 0.065 | 0.593 | 0.474 |

| The institution collaborates on specific ICU training | 0.576 | 0.074 | 0.159 | 0.008 | 0.012 | 0.096 | 0.059 | 0.209 | 0.340 | 0.084 | 0.045 | 0.457 | 0.576 | 0.024 |

| The nurses carry out intensive care training activities | 0.656 | 0.047 | 0.250 | 0.224 | 0.029 | 0.165 | 0.077 | 0.182 | 0.298 | 0.153 | 0.191 | 0.464 | 0.572 | 0.025 |

| ICU nurses act as a link between the different professionals | 0.640 | 0.113 | 0.185 | 0.312 | 0.185 | 0.247 | 0.147 | 0.132 | 0.247 | 0.275 | 0.132 | 0.303 | 0.062 | 0.706 |

| Nurses carry out ICU training mainly due to incentive payments, job listings and public examinations | 0.482 | 0.124 | 0.297 | 0.034 | 0.066 | 0.256 | 0.186 | 0.029 | 0.165 | 0.183 | 0.059 | 0.107 | 0.183 | 0.544 |

| Training activities have a positive impact at the clinical level | 0.604 | 0.241 | 0215 | 0359 | 0311 | 0272 | 0520 | 0254 | 0052 | 0112 | 0247 | 0163 | 0114 | 0539 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.492 | 5486 | 4344 | 3371 | 3162 | 3152 | 3072 | 3041 | 2836 | 2589 | 2171 | 1884 | 1777 | |

| Partial percentage of explained variance | 31.620 | 6420 | 4841 | 3444 | 2863 | 2394 | 2153 | 2023 | 1805 | 1749 | 1703 | 1645 | 1559 | |

| Total percentage of explained variance | 64.219 | |||||||||||||

| Cronbach's Alpha | 0.934 | |||||||||||||

| Ordinal Alpha | 0.949 | |||||||||||||

| Suitability Tests: | ||||||||||||||

| KMO Index: 0.948 | Goodness of Fit Index (GFI): 0.971 | |||||||||||||

| Bartlett's Sphericity: 17165.7 | Root Mean Square Residuals (RMSR) = 0.0341 | |||||||||||||

| Level of significance: 0.000 | Kelly Criterion (KC) = 0.0420 | |||||||||||||

Note: COM = communalities FAC = Factorial. Extraction method: Unweighted Least Squares (ULS). Rotation Method: Promin. In bold, higher factor loadings per factor.

The aforementioned indicated that the factorial matrix generated with 65 of the 66 items of the original questionnaire had loadings greater than ≥0.40, each of them obtaining at least 3 items. Thus, we observed that FAC1 was explained through 10 items, and factors 8 to 13 through 3 items. Only one item of 66 did not match correctly in any factorial. This item was question 22 (P22): “ICU nurses have a lot of autonomy, so it is necessary to get formal training appropriate to the job position”. This item was not included in the analysis.

The final model established by the EFA is shown in Table 2. They consist of 65 items, which have been named according to the common characteristics of each one of the items that make up each factor. The internal consistency of each factor separately was reflected by the ordinal alpha applied to each of the detected items. 23 Thus, despite the existence of appropriate Cronbach's alpha and total ordinal alpha, we have detected the existence of three factors that have an ordinal alpha lower than 0.7. On the other hand, we obtain 10 factors with a consistency higher than this value.(see table 3)

(b) Confirmatory Factor Analysis.

Table 3.

Groupings of dimensions detected in the EFA, proposed by the authors.

| Factorial | Dimensions | Items | Alpha Ordinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAC1 | Skills in critical patient care | 10 | 0.887 |

| FAC2 | Communication and Clinical Safety | 8 | 0.884 |

| FAC3 | Nursing knowledge and clinical reasoning | 8 | 0.862 |

| FAC4 | Induction Programmes for new nurses | 6 | 0.846 |

| FAC5 | Specific and ongoing training of staff nurses | 6 | 0.804 |

| FAC6 | Excellence in care | 4 | 0.628 |

| FAC7 | Critical patient assessment, tools and technology | 5 | 0.780 |

| FAC8 | Health management | 3 | 0.822 |

| FAC9 | Applying support measures | 3 | 0.798 |

| FAC10 | Decision-making and coping with end of life | 3 | 0.768 |

| FAC11 | Measures to improve care | 3 | 0.766 |

| FAC12 | Motivation to continue with the training | 3 | 0.603 |

| FAC13 | Impact of training | 3 | 0.620 |

The other half of the sample (n = 284) was used to contrast the findings of the EFA, and to indicate whether it was equally applicable to the rest of the nursing population. For this purpose, a CFA was carried out, which needed to be filtered by eliminating items with factor loadings lower than 0.5, provided that two items remained that were explanatory for each latent variable. After the analysis of numerous models, it was noted that the one with the best statistical values was the solution with 10 factors and 33 variables (see Figure 2). The CFA value showed a value of χ2 = 8952 with a CMIN/DF ratio = 2.780. The CFI of the generated model was 0.883 and the TLI reached 0.830. These values fall short of the ideal values which are ≥0.90 in both cases. However, the RMSEA value was 0.055 with a 95% confidence interval of (0.052–0.059). This value is considered reasonable in this type of study as the values obtained were ≤0.08. 21 Despite the approximation generated, other factors must be considered that influence our subjects' responses to their needs as ICU nurses.

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis. Method: Unweighted Least Squares (ULS).

Table 4 shows the covariances of each of the latent variables and their relation with the other variables in a pairwise comparison. These data are also shown in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Covariances between latent variables in the CFA.

| Pairs of Latent Variables | Covariance | p | Pairs of Latent Variables | Covariance | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1SK-F2CS | 0.362 | ** | F4FN-F5FS | 0.425 | ** |

| F1SK-F3CR | 0.324 | ** | F4FN-F7EV | 0.266 | ** |

| F1SK-F4FN | 0.218 | ** | F4FN-F8GT | 0.296 | ** |

| F1SK-F5FS | 0.315 | ** | F4FN-F9SV | 0.166 | 0.002* |

| F1SK-F7EV | 0.251 | ** | F4FN-F11MJ | 0.291 | ** |

| F1SK-F8GT | 0.329 | ** | F4FN-F12MT | 0.018 | 0.710 |

| F1SK-F9SV | 0.037 | 0.325 | F5FS-F7EV | 0.341 | ** |

| F1SK-F11MJ | 0.039 | 0.265 | F5FS-F8GT | 0.392 | ** |

| F1SK-F12MT | 0.199 | ** | F5FS-F9SV | 0.023 | 0.665 |

| F2CS-F3CR | 0.294 | ** | F5FS-F11MJ | 0.453 | ** |

| F2CS-F4FN | 0.255 | ** | F5FS-F12MT | 0.080 | 0.107 |

| F2CS-F5FS | 0.367 | ** | F7EV-F8GT | 0.399 | ** |

| F2CS-F7EV | 0.276 | ** | F7EV-F9SV | 0.167 | ** |

| F2CS-F8GT | 0.328 | ** | F7EV-F11MJ | 0.317 | ** |

| F2CS-F9SV | 0.096 | 0.037* | F7EV-F12MT | 0.206 | ** |

| F2CS-F11MJ | 0.369 | ** | F8GT-F9SV | 0.049 | 0.616 |

| F2CS-F12MT | 0.121 | 0.002* | F8GT-F11MJ | 0.510 | ** |

| F3CS-F4FN | 0.284 | ** | F8GT-F12MT | 0.711 | ** |

| F3CS-F5FS | 0.401 | ** | F9SV-F11MJ | 0.035 | 0.578 |

| F3CS-F7EV | 0.399 | ** | F9SV-F12MT | 0.330 | ** |

| F3CS-F8GT | 0.331 | ** | F11MJ-F12MT | 0.222 | ** |

| F3CS-F9SV | 0.298 | ** | |||

| F3CS-F11MJ | 0.277 | ** | |||

| F3CS-F12MT | 0.185 | ** | |||

Note: F1SK: Skills in critical patient care; F2CS: Communication and Clinical Safety; F3CR: Nursing knowledge and clinical reasoning; F4FN: Induction programmes for new nurses; F5FS: Specific and ongoing training of staff nurses; F7EV: Critical patient assessment, tools and technology; F8GT: Health management; F9SV = Applying support measures; F11MJ: Measures to improve care; F12MT: Motivation to continue with the training. ** p ≤ 0.01 *p ≤ 0.05.

In order to be able to assess the final results of the CFA, and despite not having appropriate goodness of fit values - although reasonable according to the literature - it is important to provide data on composite reliability and internal consistency in the CFAs that include a correlation matrix of ordinal data. Composite reliability gives us information between the items and the latent variable measured, and an appropriate value is considered to be above 0.7, which means that 6 of the 10 factors have appropriate values. In contrast, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indicates the value of the variance of the extracted construct; all values obtain appropriate values greater than 0.5. It should be noted that the removal of variables to refine the model has caused the model's Cronbach's alpha to fall below 0.7 in several latent variables (Table 5).

Table 5.

Internal consistency of the results of the confirmatory factor analysis.

| Relations | Individual Reliability | Internal consistency | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardised Estimators | t | p | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | ||

|

Skills in critical patient care (F1SK) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 40483, p = 0.000, CFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.935, RMSEA = 0.110 (0.080–0.143) | ||||||

| P3←F1SK | 0.645 | 0.749 | 0.782 | 0.612 | ||

| P6←F1SK | 0.694 | 13.289 | 0.000 | |||

| P14←F1SK | 0.534 | 11.243 | 0.000 | |||

| P15←F1SK | 0.558 | 11.669 | 0.000 | |||

| P37←F1SK | 0.637 | 13.048 | 0.000 | |||

|

Communication and Clinical Safety (F2CS) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 32502, p = 0.000, CFI = 0.977, TLI = 0.968, RMSEA = 0.067 (0.043–0.093) | ||||||

| P40←F2CS | 0.630 | 0.818 | 0.852 | 0.658 | ||

| P34←F2CS | 0.578 | 12.000 | 0.000 | |||

| P33←F2CS | 0.644 | 13.107 | 0.000 | |||

| P30←F2CS | 0.730 | 14.440 | 0.000 | |||

| P29←F2CS | 0.624 | 12.783 | 0.000 | |||

| P28←F2CS | 0.727 | 14.404 | 0.000 | |||

|

Nursing knowledge and clinical reasoning (F3CR) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 2164, p = 0.339, CFI = 0.999, TLI = 0.992, RMSEA = 0.012 (0.000–0.084) | ||||||

| P9←F3CR | 0.716 | 0.594 | 0.624 | 0.753 | ||

| P16←F3CR | 0.834 | 8.322 | 0.000 | |||

|

Induction programmes for new nurses (F4FN) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 42149, p = 0.000, CFI = 0.930, TLI = 0.922, RMSEA = 0.113 (0.083–0.146) | ||||||

| P55←F4FN | 0.549 | 0.653 | 0.667 | 0.625 | ||

| P61←F4FN | 0.749 | 11.160 | 0.000 | |||

| P62←F4FN | 0.605 | 10.147 | 0.000 | |||

|

Specific and ongoing training of staff nurses (F5FS) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 12238, p = 0,002, CFI = 0930, TLI = 0,922, RMSEA = 0113 (0083–0146) | ||||||

| P60←F5FS | 0.645 | 0.767 | 0.798 | 0.665 | ||

| P63←F5FS | 0.614 | 12.743 | 0.000 | |||

| P65←F5FS | 0.695 | 14.118 | 0.000 | |||

| P66←F5FS | 0.745 | 14.888 | 0.000 | |||

|

Critical patient assessment, tools and technology (F7EV) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 1529, p = 0.466, CFI = 1.000, TLI = 0.996, RMSEA = 0.000 (0.000–0.076) | ||||||

| P5←F7EV | 0.584 | 0.710 | 0.735 | 0.689 | ||

| P7←F7EV | 0.675 | 11.591 | 0.000 | |||

| P8←F7EV | 0.647 | 11.304 | 0.000 | |||

| P31←F7EV | 0.693 | 10.697 | 0.000 | |||

|

Health management (F8GT) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 3254, p = 0.654, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.994, RMSEA = 0.554 (0.515–0.574) | ||||||

| P38←F8GT | 0.756 | 0.837 | 0.841 | 0.853 | ||

| P39←F8GT | 0.958 | 14.444 | 0.000 | |||

|

Applying support measures (F9SV) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 10536, p = 0,005, CFI = 0976, TLI = 0,971, RMSEA = 0086 (0040–0140) | ||||||

| P11←F9SV | 0.742 | 0.715 | 0.727 | 0.692 | ||

| P10←F9SV | 0.598 | 10.729 | 0.000 | |||

| P15←F9SV | 0.683 | 11.177 | 0.000 | |||

|

Measures to improve care (F11MJ) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 2.782, p = 0.751, CFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.974, RMSEA = 0.457 (0.431–0.484) | ||||||

| P46←F11MJ | 0.701 | 0.593 | 0.612 | 0.596 | ||

| P48←F11MJ | 0.531 | 8.391 | 0.000 | |||

|

Motivation to continue with the training (F12MT) Goodness of fit: χ2 = 2.935, p = 0.732, CFI = 0.894, TLI = 0.919, RMSEA = 0.251 (0.229–0.268) | ||||||

| P49←F12MT | 0.696 | 0.632 | 0.644 | 0.678 | ||

| P52←F12MT | 0.702 | 9.262 | 0.000 | |||

Discussion

This study aims at detecting the underlying dimensions behind the training needs of Spanish nurses through the findings of previous studies.18,24 The fact of having achieved the participation of a significant number of ICUs throughout the national territory gives it the possibility of detecting common characteristics of the training needs of ICU nurses. A large proportion of the participants had significant experience both as nurses in other settings and in the ICU.

The EFA has enabled us to detect areas of consensus among the 66 items explored in the questionnaire. The use of Oblique Rotation and Parallel Analysis determined the need to extract 13 factors from the data provided.17,25 The explained variance in the EFA is greater than 64%, which supports the findings obtained with appropriate goodness-of-fit requirements. 19 Internal consistency, with appropriate levels of Cronbach's alpha, indicates that the EFA has been able to maintain an appropriate structure of the detected components.19,20

The components detected confirm the need for training in certain fields of critical care nursing, included in table 3. Previous studies focusing on competency acquisition report very similar areas of consensus.26,27 If we focus on the fields of the EfCCNA which were used to create the questionnaire, 9 we observe the presence of specific areas included in the sub-domains as needs of the actual Spanish nurses.

In addition, two elements are noteworthy. The first is the incorporation into the dimensions detected of the specific training of new nurses in the ICU, which has also been studied in other studies.28,29 The second is the detection of elements that encourage nurses to train, such as improvement of care, motivation and the impact of training, which other authors have quoted. 8

The items detected could be grouped into (authors′suggestion):

-

–

The need to acquire training in skills and interventions related to: critical patient care skills (10 items), communication and clinical safety (8 items), critical patient assessment, tools and technology (5 items) and Applying support measures (3 items).

-

–

Nursing knowledge consisting of: knowledge and clinical reasoning (8 items), decision making and coping with end of life (3 items), health management (3 items).

-

–

Reasoning for care made up of: measures to improve care (4 items) and excellence in care (3 items).

-

–

The elements specific to training: induction programmes for new nurses (6 items), specific and ongoing training for staff nurses (6 items) and impact of the training (3 items).

-

–

And the personal values that influence training: motivation to continue training (3 items).

The need to acquire specific knowledge for ICU through training has been studied by different authors who have implemented training focused on nursing skills and interventions in order to adapt to the needs that are required at any given moment. 30 Communication and clinical safety are closely related elements, as also recognised by other research 31 The critical thinking they must apply is an element that underlies other studies and which they link with the complexity of the care required by critical patients. 32 According to the bibliography consulted, nurses detect a progressive and continuous need to adapt to the requirements that the very essence of critical care requires of them. 33 There is a need to implement, at all times, care based on the latest scientific evidence. 33 This improved care must be approached from the set of needs detected by nurses and noted in our findings.

This first approach in the Spanish health system environment has given us the possibility of detecting similarities with previous factor analyses in other health environments.14,26,34 The findings confirm the need to continue detecting the training needs of nurses in order to create specific training for this context.

The CFA, despite the filtering performed in the model, does not reach values considered ideal.17,21 We note results that tend to be close to these ideal values in terms of the explained variance and the suitability analyses carried out 19 (table 5). Composite reliability and AVE shows higher values than those considered ideal. This fact should be sufficient to assess the overall construct to decide which areas of consensus can be included as items to have higher factor loadings that could improve our current findings.

Limitations of the study

This study may have been limited by its structure. Firstly, the survey was conducted online. We controlled the survey dissemination through the contributors of each centre. The number of responses from each ICU may have been influenced by the charisma of each partner. Secondly, as a cross-sectional study, responses may have been influenced by the personal situation of each nurse at the time of filling the survey.

The achievement of acceptable values according to the methodology used would allow us, in future research, to achieve a better model that would guide the adoption of specific training programmes for critical care nurses in Spain.

Conclusions

The outcomes of the present study show the specific needs of nurses in Spanish critical care units. These findings must be taken into account when health institutions organise training activities that guarantee homogeneous abilities and skills. Health organisations must pay special attention to the importance that nurses recognise their critical care skills, communication and safety and critical thinking.

Nurses as central elements of ICU care take a leading role in assessing, monitoring, implementing and evaluating therapeutic measures that are unique to this healthcare setting. Training needs are associated with the increased complexity of the care they have to deal with on a daily basis. This study shows us the factors that should be included in the different training strategies that societies and institutions can carry out in this field. Moreover, it allows the validation of an instrument from which to start in order to adapt the training of intensive care nurses to the clinical reality. There is a need for further development of the instrument; especially,it should continually considered adding those activities that ensure the best care for critically ill patients.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sci-10.1177_00368504221076823 for The training needs of critical care nurses: A psychometric analysis by Yeray Gabriel Santana-Padilla, María Desamparados Bernat-Adell and Luciano Santana-Cabrera in Science Progress

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-sci-10.1177_00368504221076823 for The training needs of critical care nurses: A psychometric analysis by Yeray Gabriel Santana-Padilla, María Desamparados Bernat-Adell and Luciano Santana-Cabrera in Science Progress

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-sci-10.1177_00368504221076823 for The training needs of critical care nurses: A psychometric analysis by Yeray Gabriel Santana-Padilla, María Desamparados Bernat-Adell and Luciano Santana-Cabrera in Science Progress

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the collaborators of the 70 hospitals that participated in this study.

Author biographies

Yeray Gabriel Santana-Padilla, RN, MSc, PhD, works as a scrub nurse in the emergency surgery unit at Complejo Hospitalario Insular Materno-Infantil de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain. He has received training in a master's degree in health management in the UNED University in 2009. He has an extensive work activity related to critical care. On the one hand, he is a member of several working groups related to the training of critical care nurses. On the other had hand, he has carried out numerous training activities focused on improving the quality of care in the ICU. He has led some final degree projects as associate professor at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria between 2013 and 2017. In 2014, he received his Master of Science in Nursing in Jaume I University. He is the author and contributor of several scientific articles and is also the author of a book and two book chapters related to intensive care. He is an evaluator of the continuous training activities of the health workers for the Canarian Health Service. In 2021, he finished his Doctoral degree at the Jaume I University, Castellón de La Plana, Spain.

María Desamparados Bernat-Adell, RN, MSc, PhD, is a nurse and has worked for more than 30 years in several Intensive Care Units, being ICU-head nurse for 10 years at the Hospital General Universitario de Castellón, Spain. María was the vice-president and president of the Spanish Society of Critical Intensive Care Nursing and Coronary Units from 2003 to 2006. From 2014 to de date, Maríahas been an Associated Professor and the Director of the Nursing Department at Faculty of Health Sciences, Jaume I University of Castellón, Spain. Member of the Care and Health research group (CYS group). María’s research profile is related to the field of critical patient care and family care, participation in the Congresses of the Spanish Society of Critical Intensive Care Nursing and Coronary Units, in the European Congresses of the European Federation of Critical Care Nurses Associations and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, 100 oral communications and collaboration as a speaker at several round tables and conferences, as well as the author of 26 articles and 6 book chapters related to the field of critical patients.

Luciano Santana-Cabrera, PhD, MD, is a section chief of Intensive Care Unit of Complejo Hospitalario Universitario Insular Materno Infantil de Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain. He made his specialty in intensive medicine between the years 1992 and 1996 at Nuestra Señora del Pino-Sabinal Hospital (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain). Since then he has been working in the adult intensive care unit. He received his PhD in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria University (2013). His main interest in research is related to critical care, emergency medicine and quality of healthcare processes. He has more than 100 articles in Pubmed journals as author or co-author. He is also the author of 2 books and 5 book chapters on critical care medicine. Currently, he is an external reviewer for several journals on critical care medicine and member of the Editorial Board for two International Journals of Critical Illness and other Journal of Hospital Administration. He has achieved different awards for his research work. He was a participant in the process of elaboration of the project called “Implementation of a Quality Management System in the Intensive Medicine Service of the Insular University Hospital of Gran Canaria”, which received the Annual Award for the Quality of Public Service and Best Practices in the Public Administration of the Autonomous Community of the Canary Islands of 2010.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Yeray Gabriel Santana-Padilla https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2330-1933

María Desamparados Bernat-Adell https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6616-6925

Luciano Santana-Cabrera https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8310-1197

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Flinkman M, Leino-Kilpi H, Numminen O, et al. Nurse competence scale: a systematic and psychometric review. J Adv Nurs 2017; 73: 1035–1050. Available from: 10.1111/jan.13183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lalloo D, Demou E, Stevenson M, et al. Comparison of competency priorities between UK occupational physicians and occupational health nurses. Occup Environ Med 2017; 74: 384–386. Available from: 10.1136/oemed-2016-104049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ääri RL, Tarja S, Helena LK. Competence in intensive and critical care nursing: a literature review. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2008; 24: 78–89. Available from: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García Manjón JV, Pérez López MC. Espacio europeo de educación superior, competencias profesionales y empleabilidad. Rev Iberoam Educ 2008; 46(9) :1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray DJ, Boyle WA, Beyatte MB, et al. Decision-making skills improve with critical care training: using simulation to measure progress. J Crit Care 2018; 47: 133–138. Available from: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lomero MDM, Jiménez-Herrera MF, Llaurado-Serra M, et al. Impact of training on intensive care providers’ attitudes and knowledge regarding limitation of life-support treatment and organ donation after circulatory death. Nurs Health Sci 2018; 20(2): 187–196. Available from: 10.1111/nhs.12400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Souza RdS, Bersaneti MDR, Siqueira EMP, et al. Nurses’ training in the use of a delirium screening tool. Rev Gauch Enferm 2017; 38: e64484. Available from: 10.1590/1983-1447.2017.01.64484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macedo AdC, Padilha KG, Püschel VdA. Professional practices of education/training of nurses in an intensive care unit. Rev Bras Enferm 2019; 72: 321–328. Available from: 10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waters D, Kokko A, Strunk H, et al. Competencias enfermeras según la EfCCNa para las enfermeras de cuidados intensivos en Europa. Eur Fed Crit Care Nurse Assoc 2013. [cited 2021 Sep 10]; 14. Available from: https://seeiuc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/competencias_enfermeras.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almarhabi M, Cornish J, Lee G. The effectiveness of educational interventions on trauma intensive care unit nurses’ competence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2021; 64: 102931. Available from: 10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castillo Martínez A. Percepción de competencias en enfermeras de ‘roting’. Index de Enfermería 2011; 20: 26–30. Available from: 10.4321/S1132-12962011000100006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meretoja R, Isoaho H, Leino-Kilpi H. Nurse competence scale: development and psychometric testing. J Adv Nurs 2004; 47: 124–133. Available from: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wangensteen S, Johansson IS, Björkström ME, et al. Newly graduated Nurses’ perception of competence and possible predictors: a cross-sectional survey. J Prof Nurs 2012; 28: 170–181. Available from: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wangensteen S, Johansson IS, Nordström G. Nurse competence scale - psychometric testing in a Norwegian context. Nurse Educ Pract 2015; 15: 22–29. Available from: 10.1016/j.nepr.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Müller M. Nursing competence: psychometric evaluation using rasch modelling. J Adv Nurs 2013; 69: 1410–1417. Available from: 10.1111/jan.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faraji A, Karimi M, Azizi SM, et al. Evaluation of clinical competence and its related factors among ICU nurses in Kermanshah-Iran: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Sci 2019; 6: 421–425. Available from: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lloret-Segura S, Ferreres-Traver A, Hernández-Baeza A, et al. El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: Una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. An Psicol 2014; 30: 1151–1169. Available from: 10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Santana-Padilla YG, Santana-Cabrera L, Bernat-Adell MD, et al. Necesidades de formación detectadas por enfermeras de una unidad de cuidados intensivos: un estudio fenomenológico. Enferm Intensiva 2019; 30(4): 181–191. Disponible en: 10.1016/j.enfi.2019.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Freiberg Hoffmann A, Stover JB, De la Iglesia G, et al. Correlaciones policóricas y tetracóricas en estudios factoriales exploratorios y confirmatorios. Ciencias Psicológicas 2013; VII: 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmerman ME, Lorenzo-Seva U. Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychol Methods 2011; 16: 209–220. Available from: 10.1037/a0023353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morata-Ramirez MÁ, Holgado Tello FP, Barbero-García MI, et al. Análisis factorial confirmatorio. Recomendaciones sobre mínimos cuadrados no ponderados en función del error tipo I de Ji-cuadrado y RMSEA. Acción Psicológica 2015; 12: 79. Available from: 10.5944/ap.12.1.14362. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Macey A, Green C, Jarden RJ. ICU Nurse preceptors’ perceptions of benefits, rewards, supports and commitment to the preceptor role: a mixed-methods study. Nurse Educ Pract 2021; 51: 102995. Available from: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.102995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Contreras Espinoza S, Novoa-Muñoz F. Ventajas del alfa ordinal respecto al alfa de cronbach ilustradas con la encuesta AUDIT-OMS. Rev Panam Salud Pública 2018; 42: 1–6. Available from: 10.26633/RPSP.2018.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palominos E, López I. Competencias del profesional de enfermería de cuidados intensivos pediátricos: reflexiones desde la mirada experta. Rev Educ Cienc la salud 2011; 8: 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorenzo-Seva U. Promin: a method for oblique factor rotation. Multivariate Behav Res 1999; 34: 347–365. Available from: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3403_3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn S V, Lawson D, Robertson S, et al. The development of competency standards for specialist critical care nurses. J Adv Nurs 2000; 31: 339–346. Available from: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakanmaa R-L, Suominen T, Perttilä J, et al. Basic competence in intensive and critical care nursing: development and psychometric testing of a competence scale. J Clin Nurs 2014; 23: 799–810. Available from: 10.1111/jocn.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juers A, Wheeler M, Pascoe H, et al. Transition to intensive care nursing: a state-wide, workplace centred program—12 years on. Aust Crit Care 2012; 25: 91–99. Available from: 10.1016/j.aucc.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lakanmaa R-L, Suominen T, Perttilä J, et al. Graduating nursing students’ basic competence in intensive and critical care nursing. J Clin Nurs 2014; 23: 645–653. Available from: 10.1111/jocn.12244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boling B, Hardin-Pierce M. The effect of high-fidelity simulation on knowledge and confidence in critical care training: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Pract 2016; 16: 287–293. Available from: 10.1016/j.nepr.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Escrivá Gracia J, Brage Serrano R, Fernández Garrido J. Medication errors and drug knowledge gaps among critical-care nurses: a mixed multi-method study. BMC Health Serv Res 2019; 19(1): 640. Available from: 10.1186/s12913-019-4481-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali-Abadi T, Babamohamadi H, Nobahar M. Critical thinking skills in intensive care and medical-surgical nurses and their explaining factors. Nurse Educ Pract 2020; 45: 102783. Available from: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNett M, O’Mathúna D, Tucker S, et al. A scoping review of implementation science in adult critical care settings. Crit Care Explor 2020; 2: e0301. Available from: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lakanmaa R-L, Suominen T, Ritmala-Castrén M, et al. Basic competence of intensive care unit nurses: cross-sectional survey study. Biomed Res Int 2015; 2015: 1–12. Available from: 10.1155/2015/536724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sci-10.1177_00368504221076823 for The training needs of critical care nurses: A psychometric analysis by Yeray Gabriel Santana-Padilla, María Desamparados Bernat-Adell and Luciano Santana-Cabrera in Science Progress

Supplemental material, sj-doc-2-sci-10.1177_00368504221076823 for The training needs of critical care nurses: A psychometric analysis by Yeray Gabriel Santana-Padilla, María Desamparados Bernat-Adell and Luciano Santana-Cabrera in Science Progress

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-sci-10.1177_00368504221076823 for The training needs of critical care nurses: A psychometric analysis by Yeray Gabriel Santana-Padilla, María Desamparados Bernat-Adell and Luciano Santana-Cabrera in Science Progress