Abstract

This paper analyzes the impact of widowhood on the health of mid-aged and older individuals in China using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) data. Our results show that widowhood significantly increases the risk of depression, chronic diseases, and body pain while reducing cognitive function, sleeping time, and daily activity functions. The effects on depression and daily functions are immediate, that on chronic diseases is lagged, and the effects on cognitive function and sleeping hours persist over time. We find that rural widows are particularly vulnerable to negative health outcomes due to their weaker economic positions, for whom widowhood leads to more grandchild care responsibility and corresponding workforce and social withdrawals. Moreover, rural widows’ income loss is not compensated by children, either by co-residence or financial transfers, leading to reduced living standards. Overall, our findings suggest that China needs to strengthen economic security for older people, especially among rural women, in order to avoid significant negative consequences of widowhood.

Keywords: Widowhood, Short-term Effects, Health Outcomes, CHARLS, Time Allocation

JEL Codes: J14, J12, H55

Introduction

Every married couple eventually faces the death of one spouse. With increased life expectancy, widowhood is becoming more common at older ages. The seventh population census of China in 2020 reported 41.58 million older persons who are widowed, of which 73.12% were women (National Bureau of Statistics, 2020).

Extensive literature has demonstrated that losing a spouse significantly affects physical health, mental and cognitive health, and mortality in many countries (Waite and Gallagher, 2001; Simeonova, 2013; Espinosa and Evans, 2008). The mechanisms underlying these effects may include income loss, unexpected healthcare costs associated with spousal death, loss of daily living care and spouse's social network, or reduced healthcare utilization (McGarry and Schoeni, 2005; Goda et al., 2013; Iwashyna and Christakis, 2004; Simeonova, 2013).

There are reasons to believe that the challenges of widowhood can be more severe in China, especially for women. Unlike many high-income countries, China does not offer social security survivor benefits.2 In addition, gendered labor market outcomes make men more likely to receive generous social pensions than women (Zhao and Zhao, 2018). As a result, the financial impact of widowhood is greater for women than men. In rural areas, where social pension amounts are minimal (Fang and Feng, 2018), accumulated wealth is small, and farming is the primary source of income for an elderly couple, losing the husband may be especially devastating. Although the negative impacts of widowhood on health outcomes have been observed in China (Zhang et al., 2019), research on the underlying mechanisms is limited.

This paper investigates the impact of widowhood from the perspective of family dynamics. Chinese rural people are known for depending on their children for financial support after they become unable to work (Giles et al., 2023). Research has demonstrated that elderly independence is a normal good (Costa, 1999). The absence of social security support or financial resources suggests that economically vulnerable widowed individuals may be dependent on their children, which could harm their well-being.

One task that children often give to their widowed mothers is to care for their grandchildren. However, childcare can be physically and mentally demanding, involving cooking, cleaning, washing clothes and other onerous tasks, and depriving them of income and social opportunities. Thus, childcare is not a favorite activity for many older people. In addition, research has indicated that caregiving can impede labor market participation and negatively impacts health (Chen and Liu, 2012; Hughes et al., 2007). Our findings suggest that widowhood reduces rural women's time on agricultural work, a vital source of livelihood in old age (Giles and Mu, 2007). At the same time, rural women are more likely to provide care for their grandchildren and do not increase their social activities.

Our study adds to the existing body of research on the impact of bereavement on older adults. While previous studies have predominantly examined the financial implications of widowhood, our research offers a more comprehensive understanding of how losing a spouse can alter intergenerational relations and result in older women becoming reliant on their children for support.

We begin by using a short-term individual fixed-effect model to analyze the impact of bereavement on health and confirm that the effects of widowhood are greater for women. We then examine Hukou3 differences and verify that rural women experience more adverse effects from widowhood than their urban counterparts. Next, we investigate the impact of widowhood on farming labor input and find that rural women are more likely to withdraw from farming after losing their spouse. We also study the effects of widowhood on living arrangements and grandchild caregiving and confirm that rural women are more likely to take care of grandchildren after widowhood, but they are not more likely to change their living arrangements. Because most older Chinese have adult children or their families living in the same household or community (Lei et al., 2015), grandparents often help with grandchildren care without moving. However, we also find that with more time devoted to grandchildren care, rural widows have less time to engage in social activities. We further discover that rural widows do not receive more transfers from non-coresident children. Coupled with a reduction in agricultural and non-farm income, they are more likely to fall into economic poverty, reflected in a decrease in consumption.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review the literature on the effects of widowhood on health and the mechanisms that explain those effects. Section 3, we describe the data, measures of health conditions and mechanism variables and provide descriptive statistics. Section 4 outlines our estimation strategy. We present the results and the heterogeneity analysis in Section 5. Section 6 discusses the potential mechanisms that derive the observed effects. Finally, we conclude the paper in Section 7.

Previous Literature

Many studies have found that widowhood status is associated with poorer health outcomes (Hu and Goldman, 1990; Lillard and Waite, 1995; Lillard and Panis, 1996; Sudha et al., 2006; Hughes and Waite, 2009). In recent years, there has been a shift towards using longitudinal data to estimate the effect of the transition to widowhood on health, covering a range of health variables, such as self-rated health (Liu, 2012), cardiovascular disease (Zhang and Hayward, 2006), depression symptoms, and cognition health (Simon, 2002; Sasson and Umberson, 2013; Aartsen et al., 2005). The literature consistently concludes that the transition to widowhood is negatively associated with individual health.

According to the marriage selection model, individuals who enter marriage or experience widowhood or divorce selectively differ from those who remain single, which may create endogeneity issues (Hu and Goldman, 1990; Murray, 2000; Simeonova, 2013). Several recent studies have recognized these problems and attempted to mitigate the selective bias (Espinosa and Evans, 2008; Chen et al., 2020; Tseng et al., 2017). For example, Simeonova (2013) and Goda et al. (2013) used a fixed-effect model and an event study methodology to estimate the effects of bereavement on health and out-of-pocket medical expenditures. We adopt a similar approach in this study.

Most existing literature has primarily focused on high-income countries, such as the United States (Rosnick et al., 2010; Ward et al., 2007) and Canada (Trovato and Lauris, 1989). However, few studies have examined the relationship between bereavement and health in middle- and low-income countries, including China. Although Li et al. (2005) and Zhang et al. (2019) have investigated the cross-sectional correlation between widowhood and health, there remains a gap in the literature regarding the longitudinal effects of bereavement on health outcomes in middle and low-income countries.

Most studies on widowhood and survival in China have focused solely on the correlation between the two without delving into the underlying mechanisms. This study aims to explore the mechanisms that may cause poor health in widowhood. The first mechanism is economic loss. Losing a spouse's income is the most obvious effect, particularly for women, who often face a gender earnings gap. Furthermore, marriage usually allows for a division of labor and specialization between spouses, resulting in fewer economic resources for widows and widowers due to reduced specialization (Bound et al., 1991; Gillen and Kin, 2009; Hungerford, 2001). This financial strain can also lead to decreased healthcare utilization and health investment, resulting in higher morbidity and mortality among older individuals (McGarry and Schoeni, 2005), a phenomenon known as financial embarrassment (Waite and Gallagher, 2001).

Secondly, the experience of becoming widowed may lead to a loss of social, emotional, and functional support that the spouse previously provided. Prior literature has associated harmful health behaviors such as binge-drinking and smoking with the loss of care and monitoring provided by the spouse (Umberson, 1992). Moreover, losing a spouse can reduce the availability of informal care services from the spouse, as healthier partners generally provide more significant and extensive informal assistance (Norton, 2000). Consequently, widowhood may diminish the quality of medical care the surviving spouse seeks (Iwashyna and Christakis, 2004; Simeonova, 2013).

Thirdly, losing a spouse may lead to changes in social participation. Social activities are known to positively impact older individuals' well-being (Hu et al., 2012). The emotional stress of widowhood may reduce the survivor's willingness to participate in social activities. Moreover, losing a spouse may also mean losing access to their social network (Murray, 2000). Extensive social networks have been shown to reduce mortality (Berkman and Syme, 1979). Börsch-Supan and Schuth (2014) suggest that a loss of social interactions may lead to a decline in cognitive functions.

Widowhood is not necessarily always harmful to the survivor. Long-term caregiving, particularly towards the end of life, can have a considerable emotional and financial toll on the caregiver (McGarry and Schoeni, 2005; Goda et al., 2013). The death of a spouse may relieve the caregiving burden and allow the widow or widower to re-engage in social activities.

Surprisingly, little research has been conducted on the impact of widowhood on interactions with children. When social security is absent or meager, and older adults have significantly less wealth than their children, living arrangements and financial transfers with children are important means for the children to support their elderly parents (Lei et al., 2015). In the United States, the number of widowed older people living alone increased significantly from 1940 to 1990 (Costa, 1997; McGarry and Schoeni, 2005). Costa (1999) found that the availability of social pensions explained a large proportion of the increase. Living arrangements may influence how people cope with widowhood. Some may find interactions with their children's families a comforting substitute for the lost emotional support from the spouse, but some may feel a loss of freedom. Moving to a children's community may also make older parents feel uprooted from their familiar community.

This paper contributes to the literature on the impact of widowhood by examining additional mechanisms beyond economic factors and social activities, such as the intergeneration relationship between widows/widowers and their children. Specifically, we explore living arrangements, grandchildren care, and financial transfer from children. By providing a more comprehensive understanding, we aim to shed light on why widowhood affects the health of older people and why the widowed elderly in China, mainly rural widows, become more dependent on their children.

Data

Our data come from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS) and the China Life History Survey (CHARLS-LHS). CHARLS is a national panel survey that aims to provide high-quality data on the social, economic, health, and healthcare behavior of individuals aged 45 and over in China. CHARLS uses a multistage stratified random probability proportional to size (PPS) sampling strategy from a sampling frame containing all county-level units except Tibet. In the baseline survey conducted in 2011, 17,708 respondents were surveyed, covering 450 resident communities in 150 counties or city districts. For the second wave conducted in 2013, 18,604 respondents were interviewed. The third wave, which was completed in 2015, covered 19,667 respondents. The increase in sample size included non-respondents in earlier years and refresher samples to maintain the original age distribution.

In addition to the standard demographic attributes (age, marital status, education), CHARLS includes a rich set of health variables (self-reported health, specific chronic diseases, health behavior), mental health variables (such as depression and cognition), family background, and socioeconomic variables. Moreover, CHARLS conducted a life history survey in 2014, providing information about childhood experiences, work history, health, and healthcare history. As we aim to analyze the effects of marriage transition on individuals' health, variables that reflect the marriage life course are especially important.

Description of Marital Status and Marital Transition

CHARLS respondents provide information on their current marital status,4 marital history,5 date of most recent marriage, and the date of their spouse's death.6 By using this information, we identify individuals who have become widowed between waves. If the data on spousal death is missing, we use CHARLS-LHS to supplement the information.7

We define the bereavement group as respondents who lost spouses during the CHARLS survey period. In 2011, 15,417 out of 17,708 respondents were married or in cohabitation, and 2,291 were not (including divorced, widowed, and never married). Since our focus is on the effects of bereavement, we exclude respondents who were already widowed in the baseline wave. Only a few individuals (21) became widowed after the baseline wave and remarried or found a new partner. Therefore, we exclude these cases from our analysis.8 We also exclude 370 individuals who were younger than age 45. An additional 3,280 respondents were lost due to attrition.

Finally, our analysis includes 11,746 individuals (35,238 observations over three waves), comprising 10,994 continuously married individuals and 752 individuals who experienced widowhood during the study period. Among the 752 individuals who suffered bereavement, 361 lost their spouse between 2011 and 2013, and 391 between 2013 and 2015.

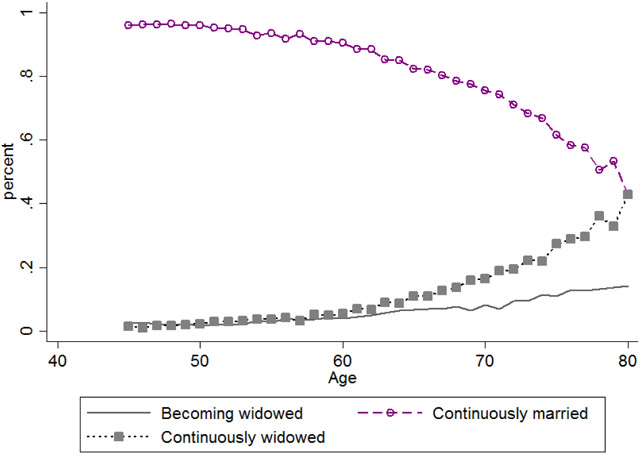

Figure 1 displays the distribution of marital status for individuals aged 45-85 using an unfiltered sample—the probability of experiencing widowed increases from 2.5% at age 45 to 14.1% at age 80. Table 1 reports descriptive statistics on marital transitions by gender and Hukou based on a filtered sample. In total, about 6% of the sample experienced spouse bereavement. The probability of widowhood was almost twice as high for women compared to men (8.4% vs. 4.3%).

Figure 1.

Distribution of martial status by age

Table 1.

Marital Status and Transition Distribution

| All | By gender | Rural | Urban | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | N | Male | Female | Difference | Male | Female | difference | Male | Female | Difference | |

| Continuously married | 0.936 | 32,982 | 0.957 | 0.916 | 0.041*** | 0.957 | 0.920 | 0.037*** | 0.958 | 0.895 | 0.063*** |

| Becoming widowed in 2011-2015 | 0.064 | 2,256 | 0.043 | 0.084 | −0.041*** | 0.043 | 0.080 | −0.037*** | 0.042 | 0.105 | −0.063*** |

| Becoming widowed in 2011-2013 | 0.031 | 1,083 | 0.018 | 0.043 | −0.025*** | 0.017 | 0.039 | −0.022*** | 0.021 | 0.064 | 0.043*** |

| Becoming widowed in 2013-2015 | 0.033 | 1,173 | 0.025 | 0.041 | −0.016*** | 0.026 | 0.041 | −0.015*** | 0.021 | 0.040 | −0.019*** |

| N | 35,238 | 17,472 | 17,766 | 13,627 | 14,709 | 3845 | 3057 | ||||

Source: CHARLS 2011, 2013 and 2015 waves.

Additionally, this gender gap in the likelihood of widowhood persists across rural and urban areas. Figure 2 illustrates widowhood probability, revealing that women with rural Hukou have the highest likelihood, while men with urban Hukou have the lowest. Notably, rural women exhibit a much higher probability of widowhood than rural men. One potential explanation for this is that rural men tend to engage in physically demanding work detrimental to their health. However, by age 75, the gap in the likelihood of widowhood between rural and urban men and women begins to narrow.

Figure 2.

The probability of becoming widowed in the next two years

Health Measures and Marital Status

We utilize subjective and objective health measures, such as self-reported health, body pain, depression, and personal assessment of mental or physical health conditions. Self-rated health is considered a useful predictor of mortality (Idler and Benyamini, 1997; Bound, 1999) and a valid indicator of overall health status. Body pain is identified when an individual reports being frequently troubled with physical pains. Because body pain is a self-reported sensation, we classify it as a subjective health variable.

Depression is a mood disorder that affects one's emotional state. To measure depression, we use a 30-point scale developed by Wallace and Herzog (1995) that accounts for the severity of depression conditions. CHARLS includes a 10-item version of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CESD). Each item is a question about how the respondent felt in the last week, with responses ranging from "rarely or none of the time" to "most or all of the time." We assign a score of 0 to the lowest response and a score of 3 to the highest level 3, with positive affect statements reverse-coded. The sum of 10 items represents the total depressive symptoms scores, ranging from 0 (no symptoms) to 30 (severe symptoms). A score above 10 indicates the presence of elevated depressive symptoms (Lei et al., 2014).

Objective variables in our study include the number of chronic diseases diagnosed by a doctor,9 indices of activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), cognition, and sleep hours. ADL in CHARLS covers basic self-care activities such as dressing, bathing and showering, eating, getting in or out of bed, using the toilet, and controlling urination and defecation. IADL includes six items: doing household chores, preparing meals, shopping for groceries, managing money, making phone calls, and taking medications. The answers for both ADL and IADL have four choices: no difficulty, have difficulty but can still do it, have difficulty and need help, and cannot do it. If the respondent reports the latter two choices, we code it as needing help in ADL or IADL.

We define episodic memory following the approach of McArdle et al. (2007) and Smith et al. (2010) as the average of immediate and delayed recall scores. Immediate recall measures the respondent's ability to repeat, in any order, 10 Chinese nouns just read to them, and delayed recall measures their ability to recall the same list of words four minutes later. Episodic memory can reflect older people's reasoning ability in all dimensions. Because poor mental health and chronic diseases are correlated with sleeping less (Newman et al., 2001), we use hours of reported actual sleep at night to reflect sleep quality as an objective variable.10

Health Measures and Marital Transition

One advantage of the CHARLS dataset is that it allows for the observation of the onset of widowhood and subsequent changes in health status in successive waves. We pay particular attention to the impact of marital transition on the surviving spouse's health outcomes. Table 2 presents the differences in health outcomes and mechanism variables between one wave before and after becoming widowed for the same 752 individuals. As shown in Table 2, apart from a slight decrease in the likelihood of having body pain, almost all other health measures worsen after becoming widowed. The different results indicate that, without controlling for other variables, needing help in ADL or IADL, CESD scores, and episodic memory scores display significant differences before and after becoming widowed. The probability of needing help in ADL or IADL increases the most, from 20.4% to 27.5% (34.8%). The CESD score after becoming widowed is 10.8 compared to 9.6 before, representing a difference of 1.2 (12.5%), and the difference in the percentage of displaying elevated depressive symptoms is 4.9 points (11.2%). Finally, episodic memory scores decline from 3.1 to 2.9 (7.1%). As some of the health declines may reflect the effect of a natural aging process, this paper aims to provide a rigorously estimate of the widowhood effects.

Table 2.

Health Outcomes Before and After widowhood

| Variable | Mean-Before Widowhood | Mean-After Widowhood |

Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Health Variables | |||

| CESD scores | 9.571 | 10.775 | −1.204*** |

| Displaying elevated depressive symptoms | 0.436 | 0.485 | −0.049 |

| Needing help in ADL or IADL (=1) | 0.204 | 0.275 | −0.071*** |

| Having body pain (=1) | 0.366 | 0.362 | 0.004 |

| Self-reported health being good, very good or excellent (=1) | 0.227 | 0.215 | 0.012 |

| Number of chronic diseases | 0.746 | 0.775 | −0.029 |

| Hours of sleep | 6.131 | 5.974 | 0.157 |

| Episodic memory scores | 3.145 | 2.923 | 0.222*** |

| B. Channel Variables | |||

| Working (=1) | 0.468 | 0.374 | 0.094*** |

| Caring for spouse (=1) | 0.112 | 0.009 | 0.103*** |

| Caring for grandchildren (=1) | 0.170 | 0.295 | −0.125*** |

| Ln hours of caring for grandchildren | 1.208 | 2.044 | −0.836*** |

| Received transfers from children (=1) | 0.646 | 0.770 | −0.124*** |

| Ln transfers from children | 4.484 | 5.325 | −0.841*** |

| Ln per capita consumption | 9.613 | 9.575 | 0.038 |

| Living with children (=1) | 0.477 | 0.451 | 0.026 |

| Having social interactions (=1) | 0.349 | 0.435 | −0.086*** |

Note: Standard deviations in brackets

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05

Source: CHARLS 2011, 2013 and 2015 waves.

Mechanism Variables

We also developed additional measures to capture individuals' economic activities and social behaviors, which could serve as potential channels for identifying the effects of spousal bereavement on health outcomes. These channels have been categorized across the following dimensions.

(1). Time allocation.

We use whether the individuals engage in work or take care of grandchildren. Labor participation is captured by individuals involved in farming work or non-farm work while taking care of grandchildren is indicated by a binary variable that equals 1 if individuals care for grandchildren below the age of 16.

We also investigate whether providing care for an infirm spouse serves as a mechanism for improving health outcomes, which is captured by the variable "Caring for spouse." In CHARLS, respondents were asked several questions, including: "Who most often helps you with [dressing/bathing/eating/getting in and out of bed/using the toilet]," "Who most often helps you with [household chores/preparing hot meals/shopping/making telephone calls/taking medications]," and "Who most often helps you manage your money?" If a person reports having difficulty in ADL or IADL and indicates that the spouse provides assistance, then the spouse is coded as providing "Caring for spouse", and the variable is defined as 1.

(2). Economic status.

We use inter-generational transfer with non-coresident children and adjusted food consumption to reflect individuals' economic situations. The CHARLS questionnaire includes the question, "In the past year, how much economic support did you or your spouse receive from your non-coresident children?" We use the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation of economic support from non-coresident children to avoid losing zero transfer cases in regression analysis. In line with Buhmann et al. (1988), food consumption per capita is adjusted using the OECD Equivalence Scale to proxy individual consumption.

(3). Social interactions.

To capture the potential impact of social interactions on health outcomes, we consider two variables: living with children and having social interactions. Living with children is captured by a dummy variable assigned a value of "1" if the respondent lives with an adult child or child-in-law. Similarly, social interactions are captured by a dummy variable assigned a value of "1" if the respondent participated in any of the following activities: regularly interacting with friends, playing chess, cards, or mahjong, or attending sporting events or clubs.

Table 2 presents changes in mechanism variables before and after bereavement.

Empirical Methods

Because losing a spouse constitutes a significant life event, we adopt a short-term perspective to analyze the dynamic effects of marital transitions.

To investigate the impacts of widowhood, we estimate the following regressions:

| (1) |

where is the respondent's health indicators or mechanism variables in the year, including subjective and objective health variables, time allocation, economic status, and social activities. Subjective health outcomes include self-reported health being good, very good or excellent, CESD scores, displaying elevated depressive symptoms, and having body pain. Objective health outcomes include the number of chronic diseases, hours of sleep, needing help in ADL or IADL, and episodic memory scores. is a dummy variable indicating whether an individual was widowed by the survey year. The coefficient on the indicator variable of widowed measures the effect of bereavement on health, holding constant the other variable in the model. captures the person-specific time-invariant fixed effect. is a year fixed effect. is a stochastic error term.

The individual fixed-effect model has the advantage of controlling for unobserved characteristics that remain constant over time. For example, weak community infrastructure and weak healthcare systems may be associated with a spouse's death and impact people's health (Smith et al., 2013). Moreover, an individual's health habits or personal preference for exercise that may have contributed to a spouse's death can also lead to poor health outcomes among respondents because they live together and influence each other (Simeonova, 2013). By differencing such omitted variables and holding them constant across waves, the fixed-effect model can help to reduce unobserved heterogeneity bias errors. To address time-variant unobserved heterogeneous bias, we introduce the following interactions. First, for variables using fixed effect, we add the interaction of 2011 health with a linear time trend , controlling for unobservable individual health characteristics that may change over time. We also introduce the interaction of county dummies with a linear time trend to control for time-variant unobserved factors such as changes in medical policy within a county.

The effects of widowhood may vary over time. For example, individuals may suffer a sudden shock after becoming widowed but over time may adapt to these changes. To examine the time-varying effects of widowhood, we employ the event study method by including dummies for the number of years before/after losing a spouse in the following model:

| (2) |

indicates time re-centered around the time of widowhood (when ). is an indicator variable taking value 1 if the person becomes widowed in the year. The coefficient captures the differential effects associated with the year of bereavement. The time frame in our analysis is restricted between one wave before widowhood and two waves after, which means that we set . The year after bereavement () is the omitted category. The definitions of the other variables are the same as for equation (1). We cluster the standard errors at the individual level in all fixed-effects estimators and make them robust to heteroscedasticity and serial correlation in the short panels. Because the CHARLS is conducted biennially, one wave of the CHARLS represents a time frame of approximately two years.

Results

Widowhood and Health

Table 3 presents the results of estimating equation (1) on health variables. The top section of the table indicates that losing a spouse has a significant negative impact on an individual's health outcomes. Specifically, widowhood is found to harm mental health. The results show that becoming widowed increases the probability of having elevated depressive symptoms by 11.7 percentage points, representing a 32.9% (0.117/0.355) increase over the mean probability of having elevated depressive symptoms in 2011. In addition, widowhood increases CESD scores by 2.02, representing a 24.7% (2.02/8.164) increase over the mean CESD scores in 2011.

Table 3.

Effects of Widowhood on Health Indicators-Individual Fixed Effects Regressions

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | CESD scores |

Displaying elevated depressive symptoms |

Needing help in ADL or IADL |

Having body pain |

Self- reported health being good, very good or excellent |

Number of chronic diseases |

Hours of sleep |

Episodic memory scores |

| Being widowed | 2.016*** | 0117*** | 0.080*** | 0.037** | −0.004 | 0.029** | −0.196** | −0.382*** |

| (0.288) | (0.024) | (0.016) | (0.018) | (0.016) | (0.013) | (0.084) | (0.069) | |

| Observations | 28,603 | 28,603 | 34,633 | 34,222 | 34,204 | 34,706 | 31,159 | 27,937 |

| R-squared | 0.166 | 0.098 | 0.167 | 0.189 | 0.213 | 0.205 | 0.163 | 0.165 |

| Year bereaved-2 indicator | −0.531* | −0.038 | −0.005 | −0.024 | −0.001 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.330*** |

| (0.322) | (0.031) | (0.019) | (0.024) | (0.021) | (0.018) | (0.110) | (0.100) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator | 1.994*** | 0.118*** | 0.080*** | 0.018 | −0.003 | 0.022 | −0.172* | −0.236*** |

| (0.324) | (0.027) | (0.019) | (0.022) | (0.019) | (0.015) | (0.102) | (0.086) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator | 1.461*** | 0.069* | 0.077*** | 0.087*** | −0.009 | 0.065*** | −0.278** | −0.502*** |

| (0.449) | (0.040) | (0.026) | (0.031) | (0.027) | (0.018) | (0.139) | (0.117) | |

| Observations | 28,603 | 28,603 | 34,633 | 34,222 | 34,204 | 34,706 | 31,159 | 27,937 |

| R-squared | 0.166 | 0.099 | 0.167 | 0.189 | 0.213 | 0.205 | 0.163 | 0.166 |

Note:

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05; robust standard errors are in parentheses. The sample includes continuously married, continuously widowed and becoming widowed people. All regressions included controls for the interactions of 2011 dependent health condition with a linear time trend, and the interactions of county dummies with time trend.

Poor mental health may trigger other health conditions (Byers et al., 2012). Becoming widowed is linked with an 8.0 percentage point rise in the likelihood of needing help in ADL or IADL and a 0.029 increase in the number of chronic diseases, which represent 57% (0.08/0.140) and 4.3% (0.029/0.677) increases, respectively, over the mean level in 2011. Losing a spouse also significantly reduces a person's cognition score by 0.382.

The lower half of Table 3 shows the short-term dynamic effects of widowhood on health outcomes using the fixed-effect model. As expected, we observe that different health variables display varying changing patterns after widowhood.

Table 3 uses the fixed-effect model to show the short-term dynamic effects of becoming widowed on health outcomes. As shown in the table, the adverse effects of widowhood on certain health variables (needing help in ADL or IADL, CESD scores, displaying elevated depressive symptoms) exhibit a short-term worsening process followed by improvement. Specifically, in the first wave after becoming widowed, depression scores increase by 1.994, and the probability of displaying elevated depressive symptoms increases by 11.8 percentage points. However, in the second wave following the spouse’s death, the depression situation improves, with the value reducing to 1.461 and the probability shrinking by 6.9 percentage points. These results are consistent with Tseng et al. (2017), which show that bereaved respondents have higher CESD scores in the two years after their spouse passed away, with a peak at two years after bereavement. In addition, the probability of needing help in ADL or IADL displays a pattern similar to that of depression, supporting the positive association between mood and a person's daily activity ability (Byers et al., 2012; Collins et al., 2008).

Several health outcomes show a delayed worsening effect after losing a spouse, indicating lagged adverse impact of bereavement. For instance, if an individual became widowed between 2011 and 2013, their likelihood of having body pain increased by 8.7 percentage points (26.3%) in 2015. Additionally, the number of chronic diseases increased by 0.065 (9.6%), revealing the negative impact of losing a spouse on chronic diseases.

Table 3 shows that some health deteriorations persist after losing a spouse. One example is sleeping hours. Additionally, cognition declines persistently, consistent with the findings of Lei et al. (2012). Notably, an individual's cognition declines immediately in the same year of widowhood. In the first wave after becoming widowed, the magnitude of the individual's episodic memory scores declines by 0.236. During the second wave, it declines further by 0.502.

Overall, the estimates of the health effects of marital transition depend on the specific health outcomes considered. Our results suggest that losing a spouse affects chronic diseases, which implies that chronic diseases reflect long-term dysregulation of major physiological systems (McEwen and Stellar, 1993). In contrast, declines in mental health are initially sharp but then reversed, consistent with previous findings that mental health responds relatively quickly to marital transitions (Marks and Lambert, 1998; Simon, 2002). However, declines in cognitive functions are long-lasting.

Heterogeneity Analysis: Gender and Hukou Effects

Considerable differences exist between rural and urban communities in China, including income levels, access to healthcare, etc. Still, the social pension system is the most glaring difference relevant for older people. Until the New Rural Pension Scheme was implemented in 2009, rural people were not entitled to public pensions, while urban people have enjoyed the urban employee pension benefits since the 1950s.11 However, rural people aged 60 years and older receive only a monthly pension of 119 RMB (19.1 USD) in 2015 yuan, a small portion of urban residents' pension (Giles et al., 2023). Even within rural areas, men receive higher pensions than women because more men have employment experiences in the urban sector (Zhao and Zhao, 2018). This subsection analyzes whether widowhood's effects differ by gender and Hukou by estimating the interacted versions of equations (1) and (2).

Column 1 of Table 4 displays the estimated results of becoming widowed based on gender. For most health variables, the coefficients for widowed×female are significant and positive, indicating that the adverse effects on women's health are more severe than men after widowhood. Specifically, widows exhibit more severe depression symptoms, a higher probability of needing help in ADL or IADL, more body pain, and more sleep problems than men after bereavement.

Table 4.

Widowhood Effects on Health Indicators by Gender and Hukou: Individual Fixed Effects Regressions

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | CESD scores |

Displaying elevated depressive symptoms |

Needing help in ADL or IADL |

Having body pain |

Self- reported health being good, very good or excellent |

Number of chronic diseases |

Hours of sleep |

Episodic memory scores |

| Being widowed | 0.736* | 0.058 | 0.045* | −0.017 | −0.014 | 0.012 | 0.058 | −0.289** |

| (0.428) | (0.038) | (0.026) | (0.028) | (0.026) | (0.024) | (0.142) | (0.114) | |

| Being widowed×female | 2.060*** | 0.096** | 0.054* | 0.083** | 0.015 | 0.025 | −0.396** | −0.143 |

| (0.565) | (0.049) | (0.032) | (0.035) | (0.032) | (0.028) | (0.174) | (0.141) | |

| Observations | 28,603 | 28,603 | 34,633 | 34,222 | 34,204 | 34,706 | 31,159 | 27,937 |

| R-squared | 0.167 | 0.099 | 0.167 | 0.189 | 0.213 | 0.205 | 0.163 | 0.165 |

| Being widowed | 0.739* | 0.058 | 0.045* | −0.017 | −0.014 | 0.012 | 0.058 | −0.290** |

| (0.428) | (0.038) | (0.026) | (0.028) | (0.026) | (0.024) | (0.142) | (0.114) | |

| Being widowed×female | 0.130 | −0.0003 | −0.038 | 0.075 | 0.058 | 0.040 | −0.333 | 0.324 |

| (0.846) | (0.070) | (0.042) | (0.056) | (0.057) | (0.037) | (0.238) | (0.229) | |

| Being widowed×female×rural | 2.418*** | 0.121* | 0.112*** | 0.010 | −0.052 | −0.018 | −0.077 | −0.576*** |

| (0.845) | (0.068) | (0.040) | (0.055) | (0.055) | (0.032) | (0.224) | (0.219) | |

| Observations | 28,603 | 28,603 | 34,633 | 34,222 | 34,204 | 34,706 | 31,159 | 27,937 |

| R-squared | 0.167 | 0.099 | 0.167 | 0.189 | 0.213 | 0.205 | 0.163 | 0.165 |

Note:

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05; robust standard errors are in parentheses. The sample includes continuously married, continuously widowed and becoming widowed people. All regressions included controls for the interactions of 2011 dependent health condition with a linear time trend, and the interactions of county dummies with time trend.

To investigate whether the adverse effects of widowhood differ by Hukou status (rural vs. urban), we estimate the interaction effects between being widowed, female, and rural Hukou. The results reveal that becoming widowed has a more detrimental impact on rural women's health than urban women. As shown in the lower section of Table 4, rural women are more likely to experience higher depressive symptoms, increased needing help with ADL or IADL, and reduced episodic memory after widowhood. Specifically, compared to urban women, the CESD scores of rural women increase by 2.418, which is statistically significant at the 1% level, and their likelihood of needing help in ADL or IADL increases by 11.2 percentage points. Similarly, rural women experience a more significant decline in episodic memory than urban women after losing a spouse. Given that Chinese women have worse cognitive function than men, declines in women's cognition after losing a spouse pose a greater threat to their health (Lei et al., 2012).

We conducted further analysis of the dynamic heterogeneity effects between gender and Hukou status, as presented in Table 5. Combining the results from columns 1 and 2 of Table 5, we observe that the adverse effects of bereavement on rural women's depression are most significant in the year following bereavement. As shown in Table 5, rural women exhibit more lasting impacts on depression, cognitive function, and disability than urban women. Moreover, sleeping hours declined persistently until the second wave after bereavement.

Table 5.

Dynamic Effects of Widowhood on Health Indicators by Gender and Hukou

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | CESD score |

Displaying elevated depressive symptoms |

Needing help in ADL or IADL |

Having body pain |

Self- reported health being good, very good or excellent |

Number of chronic diseases |

Hours of sleep |

Episodic memory scores |

| Year bereaved-2 indicator | −0.833* | −0.066 | −0.006 | 0.050 | −0.030 | −0.005 | 0.211 | 0.250* |

| (0.440) | (0.046) | (0.030) | (0.034) | (0.033) | (0.030) | (0.180) | (0.150) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator | 0.566 | 0.052 | 0.049 | 0.005 | −0.023 | 0.008 | 0.064 | −0.178 |

| (0.487) | (0.045) | (0.031) | (0.036) | (0.032) | (0.028) | (0.184) | (0.149) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator | 0.140 | −0.023 | 0.017 | −0.036 | −0.022 | 0.028 | 0.353 | −0.380* |

| (0.753) | (0.062) | (0.040) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.038) | (0.272) | (0.196) | |

| Year bereaved-2 indicator×female | 0.416 | 0.042 | 0.000 | −0.120** | 0.046 | 0.015 | −0.327 | 0.138 |

| (0.621) | (0.062) | (0.039) | (0.047) | (0.042) | (0.038) | (0.226) | (0.201) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator×female | 2.294*** | 0.105* | 0.047 | 0.020 | 0.030 | 0.021 | −0.367* | −0.090 |

| (0.642) | (0.056) | (0.039) | (0.045) | (0.040) | (0.033) | (0.219) | (0.181) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator×female | 2.035** | 0.141* | 0.086* | 0.179*** | 0.019 | 0.052 | −0.916*** | −0.178 |

| (0.929) | (0.079) | (0.051) | (0.062) | (0.059) | (0.042) | (0.314) | (0.242) | |

| Observations | 28,603 | 28,603 | 34,633 | 34,222 | 34,204 | 34,706 | 31,159 | 27,937 |

| R-squared | 0.167 | 0.099 | 0.167 | 0.190 | 0.213 | 0.205 | 0.164 | 0.166 |

| Year bereaved-2 indicator | −0.832* | −0.066 | −0.006 | 0.050 | −0.030 | −0.005 | 0.211 | 0.250* |

| (0.440) | (0.046) | (0.030) | (0.034) | (0.033) | (0.030) | (0.180) | (0.150) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator | 0.568 | 0.0523 | 0.049 | 0.005 | −0.023 | 0.008 | 0.064 | −0.178 |

| (0.487) | (0.045) | (0.031) | (0.036) | (0.032) | (0.028) | (0.184) | (0.149) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator | 0.144 | −0.023 | 0.017 | −0.036 | −0.022 | 0.029 | 0.353 | −0.381* |

| (0.753) | (0.062) | (0.040) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.038) | (0.272) | (0.196) | |

| Year bereaved-2 indicator×female | 0.413 | 0.015 | 0.002 | −0.131 | −0.054 | 0.029 | −0.140 | −0.258 |

| (1.272) | (0.100) | (0.076) | (0.083) | (0.086) | (0.060) | (0.280) | (0.338) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator×female | 0.428 | −0.000 | −0.034 | 0.024 | 0.039 | 0.032 | −0.306 | 0.159 |

| (0.866) | (0.075) | (0.050) | (0.070) | (0.070) | (0.043) | (0.277) | (0.260) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator×female | 0.137 | 0.064 | −0.039 | 0.128 | 0.090 | 0.080 | −0.672* | 0.559 |

| (1.269) | (0.112) | (0.066) | (0.094) | (0.101) | (0.049) | (0.403) | (0.400) | |

| Year bereaved-2 indicator×female×rural | 0.091 | 0.037 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.117 | −0.017 | −0.222 | 0.458 |

| (1.287) | (0.100) | (0.075) | (0.084) | (0.084) | (0.058) | (0.269) | (0.337) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator×female×rural | 2.356*** | 0.134* | 0.098** | −0.005 | −0.010 | −0.013 | −0.076 | −0.304 |

| (0.871) | (0.072) | (0.049) | (0.068) | (0.068) | (0.038) | (0.250) | (0.244) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator×female×rural | 2.425** | 0.097 | 0.154** | 0.062 | −0.087 | −0.034 | −0.308 | −0.908** |

| (1.209) | (0.111) | (0.065) | (0.091) | (0.095) | (0.039) | (0.350) | (0.381) | |

| Observations | 28,603 | 28,603 | 34,633 | 34,222 | 34,204 | 34,706 | 31,159 | 27,937 |

| R-squared | 0.168 | 0.099 | 0.167 | 0.190 | 0.213 | 0.205 | 0.164 | 0.166 |

Note:

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05; robust standard errors are in parentheses. The sample includes continuously married, continuously widowed and becoming widowed people. All regressions included controls for the interactions of 2011 dependent health condition with a linear time trend, and the interactions of county dummies with time trend.

In summary, combining the findings from Tables 4 and 5, we observe that widows, particularly rural widows, experience more pronounced adverse health declines. What accounts for the greater short-term impact of losing a spouse on women, particularly rural women? The possible explanation is that rural women are disadvantaged regarding economic status. Previous research has shown that rural women are more likely to live in poverty than rural men because of their lower participation rates in agricultural and non-agricultural labor (Giles et al., 2023). Widowhood further exacerbates economic distress and heightens their financial dependence on adult children.

Mechanism

Next, we investigate three micro-channels that have received limited attention in the literature to explain why rural widows experience more pronounced health deterioration following bereavement, including time allocation, socioeconomic status and socialization. The variables we use are labor force participation, living with children, economic transfers, social interactions, time allocation (especially childcare), and per capita consumption. The results of our analysis are presented in Table 6, which provides both the expected outcomes and the dynamic mechanical analysis.

Table 6.

Widowhood Mechanism Analysis of Health Indicators

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Working | Caring for spouse |

Caring for grandchildren |

Ln hours of caring for grandchildren |

Received transfers from children |

Ln transfers from children |

Ln per capita consumption |

Living with children |

Having social interactions |

|

| Being widowed | −0.049*** | −0.149*** | 0.056*** | 0.138 | −0.137*** | −0.597*** | −0.032 | 0.132*** | 0.066*** |

| (0.017) | (0.011) | (0.017) | (0.134) | (0.020) | (0.171) | (0.066) | (0.018) | (0.023) | |

| Observations | 34,893 | 35,238 | 34,899 | 34,899 | 34,885 | 34,427 | 34,021 | 34,766 | 33,044 |

| R-squared | 0.038 | 0.033 | 0.043 | 0.057 | 0.318 | 0.185 | 0.087 | 0.184 | 0.046 |

| Year bereaved−1 indicator | −0.026 | 0.017 | 0.016 | 0.236 | 0.038 | 0.004 | 0.115* | −0.022 | 0.023 |

| (0.024) | (0.017) | (0.022) | (0.174) | (0.029) | (0.217) | (0.060) | (0.014) | (0.031) | |

| Year bereaved +1 indicator | −0.052*** | −0.143*** | 0.068*** | 0.296** | −0.119*** | −0.526*** | 0.008 | 0.096*** | 0.087*** |

| (0.018) | (0.012) | (0.019) | (0.149) | (0.021) | (0.182) | (0.069) | (0.017) | (0.026) | |

| Year bereaved +2 indicator | −0.067** | −0.154*** | 0.024 | −0.234 | −0.165*** | −0.897*** | −0.039 | 0.257*** | 0.015 |

| (0.028) | (0.014) | (0.029) | (0.221) | (0.030) | (0.258) | (0.095) | (0.032) | (0.037) | |

| Observations | 34,893 | 35,238 | 34,899 | 34,899 | 34,885 | 34,427 | 34,021 | 34,766 | 33,044 |

| R-squared | 0.038 | 0.033 | 0.043 | 0.057 | 0.318 | 0.185 | 0.087 | 0.186 | 0.046 |

Note:

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05; robust standard errors are in parentheses. The sample includes continuously married, continuously widowed and becoming widowed people. All regressions included controls for the interactions of 2011 dependent health condition with a linear time trend, and the interactions of county dummies with time trend.

Table 6 reveals that individuals' labor force participation significantly decreases after experiencing widowhood. More specifically, widowhood is associated with a 4.9 percentage points (8.2%) reduction in working. The dynamic results of Table 6 indicate that labor market withdrawal lasts for at least two waves after bereavement. The decline is possibly due to the increased burden of caring for grandchildren. Particularly in the first wave after bereavement, the probability of caring for grandchildren increases by 6.8 percentage points (20.1%), and the number of hours doing so increases by 29.6%. Moreover, an average woman is more likely to engage in social activities, such as interacting with friends, playing cards, and attending a sports event. This is a reasonable coping strategy – friends can substitute for a spouse as a source of emotional support.

The reduction in labor force participation due to bereavement may lead to a decline in income, which could be compensated for by children’s transfers. However, widowed individuals experience a 13.7 percentage points reduction in transfers from non-coresident children. This could partly be explained by a change in living arrangements as transfers are defined by those from non-coresident children. As shown in column 8 of Table 6, the probability of an average surviving spouse living with children significantly increases after the spouse's death.

The effects are significantly different by gender and Hukou status. As shown in the lower panel of Table 7, rural widows exhibit a significantly lower probability of working by 13.2 percentage points in contrast to urban widows.

Table 7.

Mechanisms of Widowhood on Health Indicators by Gender and Hukou

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Working | Caring for spouse |

Caring for grandchildren |

Ln hours of caring for grandchildren |

Received transfer s from children |

Ln transfers from children |

Ln per capita consumption |

Living with children |

Having social interactions |

| Being widowed | −0.061*** | −0.145*** | 0.011 | −0.185 | −0.143*** | −0.700** | 0.061 | 0.119*** | 0.030 |

| (0.027) | (0.018) | (0.027) | (0.205) | (0.035) | (0.286) | (0.104) | (0.031) | (0.039) | |

| Being widowed×female | 0.018 | −0.006 | 0.069** | 0.488* | 0.008 | 0.158 | −0.139 | 0.021 | 0.056 |

| (0.034) | (0.022) | (0.035) | (0.263) | (0.042) | (0.351) | (0.134) | (0.037) | (0.047) | |

| Observations | 34,893 | 35,238 | 34,899 | 34,899 | 34,885 | 34,427 | 34,021 | 34,766 | 33,044 |

| R-squared | 0.038 | 0.033 | 0.043 | 0.057 | 0.318 | 0.185 | 0.087 | 0.184 | 0.046 |

| Being widowed | −0.061** | −0.145*** | 0.011 | −0.184 | −0.143*** | −0.700** | 0.061 | 0.119*** | 0.030 |

| (0.027) | (0.018) | (0.027) | (0.205) | (0.035) | (0.286) | (0.104) | (0.031) | (0.039) | |

| Being widowed×female | 0.127*** | 0.052** | −0.048 | −0.448 | 0.029 | −0.112 | 0.060 | 0.025 | 0.063 |

| (0.035) | (0.026) | (0.057) | (0.442) | (0.072) | (0.584) | (0.141) | (0.053) | (0.076) | |

| Being widowed×female×rural | −0.132*** | −0.073*** | 0.142*** | 1.144*** | −0.025 | 0.326 | −0.237* | −0.005 | −0.007 |

| (0.033) | (0.024) | (0.055) | (0.435) | (0.068) | (0.560) | (0.138) | (0.049) | (0.073) | |

| Observations | 34,893 | 35,238 | 34,899 | 34,899 | 34,885 | 34,427 | 34,021 | 34,766 | 33,044 |

| R-squared | 0.038 | 0.033 | 0.043 | 0.057 | 0.318 | 0.185 | 0.087 | 0.184 | 0.046 |

Note:

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05; robust standard errors are in parentheses. The sample includes continuously married, continuously widowed and becoming widowed people. All regressions included controls for the interactions of 2011 dependent health condition with a linear time trend, and the interactions of county dummies with time trend.

One important reason for work reduction among rural widows is caring for grandchildren, a typical task adult children ask their parents to do, especially since many adults children work as migrant workers in cities and leave their children behind (Giles and Mu, 2007). As shown in columns 3 and 4 of Table 7, after bereavement, rural women are 14.2 percentage points more likely to care for grandchildren and increase their care hours by 114.4% compared to urban widows.

The effects on living arrangements are also different for rural vs. urban widows. Co-residence with an adult child or the child's family is considered an important source of support for older people (Lei et al., 2012). However, rural women are not significantly more likely to live with the family of adult children after becoming widowed, even as they take on more responsibility for caring for their grandchildren. As mentioned earlier, older widows living in their own homes while caring for their grandchildren is feasible because the family of their adult sons tends to live in the same village or leave children behind while working as migrant workers.

Looking at the impact of widowhood on transfers from children, rural widows do not receive more monetary transfers from their adult non-coresident children, all relative to urban widows (columns 6 and 7 of Table 7). This phenomenon may seem bewildering given greater economic losses among rural widows due to work withdrawal and no increase in co-residence with children while caring for grandchildren. To understand this, we note that the directions of transfers differ across rural and urban areas – rural older parents are net recipients of financial transfers while their urban counterparts are net givers (Lei et al., 2012). Therefore, as the father dies, rural children see a reduced need for their transfers. Consequently, the reduction of rural widows' consumption is 23.7% more than that for urban widows, indicating greater financial difficulties for rural women.

Finally, we examine the impact of bereavement on socialization among rural women, as indicated by their likelihood of interacting with friends, playing chess or mahjong, or exercising, as presented in column 9 of Table 7. Our results suggest that rural women tend to socialize less after losing a spouse than their urban counterparts, although the effect is not statistically significant. We interpret the result as another sacrifice widows make by taking on the task of grandchildren care.

Conclusions and Discussions

We study the impact of spousal loss on the health of individuals ages 45 and older in China. Using data from CHARLS, we find spousal loss has immediate negative consequences on both mental, physical and cognitive health. Specifically, we observed an increased likelihood of having elevated depression symptoms, body pain, higher incidence of chronic diseases, requiring assistance with daily activities, reduced cognitive ability, and reduced sleeping hours. The probability of experiencing elevated depressive symptoms and requiring assistance with daily activities is highest during the initial period after losing a spouse and decreases over time, indicating that individuals are most vulnerable to adverse health outcomes in the first one to two years following spousal loss. However, declines in cognitive functions and sleeping hours of bereaved individuals persist over time.

Further analysis revealed that the negative effects are generally larger among rural women. To understand this, we show that rural widows are more likely to be called on to care for their grandchildren than urban women, reflecting their lower level of economic security and the associated bargaining position. The caregiving duty causes them to withdraw from the workforce. While rural widows do not generally change living arrangements when caring for their grandchildren because most have children living in the same house or nearby, their economic loss is not compensated by additional financial help from non-coresident children, resulting in lower living standards. Interacting with others in the community can often compensate for the spousal loss. Indeed, men and urban women tend to engage in more social activities after widowhood, but the increase in social activities for rural women is more limited, perhaps due to the additional childcare duties.

A changing trajectory of work and life for rural women in China after widowhood is evident. While this arrangement benefits adult children, it burdens rural widows heavily. Past studies indicate that caring for grandchildren may negatively affect a person's health as it involves long hours of heavy-duty work (Chen and Liu, 2012; Hughes et al., 2007). The adverse effects may be amplified by losing income and restricting social interactions due to caregiving duty.

As China transitions into a modern society with a reduced number and out-migration of children, the reliability of children as providers and caregivers is deemed to decline (Chen et al., 2022). China needs to build up a solid social pension program. The New Rural Pension Program, which has become part of the Resident Pension Program, is insufficient to prevent old-age poverty (Zhang et al., 2019; Gong et al., 2022).

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (21BJY011) , National Natural Science Foundation of China (72061137005) and the National Institute on Aging (R01AG037031, R01AG067625).

Appendix

Table A1.

Dynamic Mechanism Analysis of the Effects of Widowhood on Health Indicators by Gender and Hukou (available on request)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | Working | Caring for spouse |

Caring for grandchildren |

Ln hours of caring for grandchildren |

Received transfers from children |

Ln transfers from children |

Ln per capita consumption |

Living with children |

Having social interactions |

| Year bereaved-1 indicator | −0.009 | 0.062** | 0.020 | 0.157 | 0.041 | 0.166 | 0.075 | −0.026 | 0.078 |

| (0.039) | (0.026) | (0.033) | (0.271) | (0.046) | (0.346) | (0.090) | (0.020) | (0.048) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator | −0.066** | −0.123*** | 0.027 | −0.070 | −0.125*** | −0.531* | 0.130 | 0.101*** | 0.052 |

| (0.031) | (0.020) | (0.030) | (0.234) | (0.037) | (0.308) | (0.100) | (0.031) | (0.043) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator | −0.052 | −0.144*** | −0.040 | −0.542 | −0.167*** | −1.286*** | −0.118 | 0.178*** | 0.041 |

| (0.048) | (0.029) | (0.053) | (0.375) | (0.056) | (0.461) | (0.230) | (0.048) | (0.067) | |

| Year bereaved-1 indicator×female | −0.041 | −0.042 | −0.051 | 0.056 | 0.105 | 0.400 | 0.027 | 0.036 | −0.138 |

| (0.066) | (0.047) | (0.075) | (0.680) | (0.101) | (0.802) | (0.165) | (0.049) | (0.097) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator×female | 0.126*** | 0.040 | −0.059 | −0.409 | 0.050 | −0.020 | 0.053 | −0.045 | 0.056 |

| (0.043) | (0.031) | (0.055) | (0.451) | (0.081) | (0.670) | (0.149) | (0.050) | (0.087) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator×female | 0.100 | 0.038 | −0.036 | −0.446 | 0.040 | 0.075 | 0.143 | 0.259*** | −0.039 |

| (0.064) | (0.036) | (0.097) | (0.703) | (0.099) | (0.825) | (0.254) | (0.086) | (0.118) | |

| Year bereaved-1 indicator×female×rural | 0.012 | −0.037 | 0.055 | 0.096 | −0.130 | −0.772 | 0.036 | −0.034 | 0.059 |

| (0.063) | (0.047) | (0.074) | (0.667) | (0.098) | (0.782) | (0.163) | (0.050) | (0.095) | |

| Year bereaved+1 indicator×female×rural | −0.128*** | −0.087*** | 0.151*** | 1.183*** | −0.051 | 0.034 | −0.283* | 0.048 | −0.002 |

| (0.039) | (0.030) | (0.053) | (0.441) | (0.078) | (0.642) | (0.154) | (0.046) | (0.083) | |

| Year bereaved+2 indicator×female×rural | −0.149** | −0.068** | 0.158* | 1.114* | −0.045 | 0.585 | −0.039 | −0.188** | 0.006 |

| (0.058) | (0.028) | (0.090) | (0.666) | (0.091) | (0.767) | (0.160) | (0.085) | (0.110) | |

| Observations | 34,893 | 35,238 | 34,899 | 34,899 | 34,885 | 34,427 | 34,021 | 34,766 | 33,044 |

| R-squared | 0.039 | 0.033 | 0.043 | 0.057 | 0.318 | 0.185 | 0.087 | 0.186 | 0.047 |

Note:

p<0.001

p<0.01

p<0.05; robust standard errors are in parentheses. The sample includes continuously married, continuously widowed and becoming widowed people. All regressions included controls for the interactions of 2011 dependent health condition with a linear time trend, and the interactions of county dummies with time trend.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

In many high-income countries, individuals are often entitled to inherit a portion of their deceased spouse's pension. In contrast, in China, when an individual passes away, the household typically only receives a funeral pension and individual old-age insurance. Furthermore, unlike in high-income countries, funeral pension and basic pension funds are not necessarily allocated to the surviving spouse.

The Hukou system in China has long been regarded as a form of social and economic segregation, as it divides Chinese citizens into agricultural and non-agricultural residents.

Marital status was asked as follows: What is your marital status? Choices are: 1. married with spouse present; 2. married but not living with spouse temporarily for reasons such as work; 3. separated; 4. divorced; 5. widowed; 6. never married; 7. cohabitated.

Marital history question was: How many times have you been married since last interview?

The timing of death question was: When did your spouse pass away?

CHARLS-LHS is a life history survey that commenced in 2014. It provides comprehensive information about participants' marital histories, such as the year of marriage, divorce, spouse's death, and cause of death. Knowing whether a participant's spouse is deceased and the date of death is crucial for accurately identifying when they became widowed between survey waves. While detailed information about the spouse's death was available in 2011 and 2013, it was not available in 2015. To compensate for this missing data, we utilize the spouse's death information provided in CHARLS-LHS to augment our analysis.

Our findings remained robust when these observations were included.

Chronic diseases refer to a range of medical conditions, including but not limited to hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes or high blood sugar, cancer or malignant tumor, chronic lung diseases, liver disease, heart attack, stroke, kidney disease, stomach or other digestive disease, emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, memory-related disease, arthritis or rheumatism, and asthma.

Over the past month, how many hours of actual sleep did you get at night (average hours for one night)?

For a detailed description of rural and urban social security system, please refer to Lei et al. (2014).

Contributor Information

Qin Li, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, China.

James P. Smith, Rose Li & Associates, Rockville, MD, USA

Yaohui Zhao, Peking University, Beijing, China.

References:

- Aartsen MJ, Van Tilburg T, Smits CHM, Comijs HC, & Knipscheer KCPM (2005). Does widowhood affect memory performance of older persons? Psychological Medicine, 35, 217–226. 10.1017/S0033291704002831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, & Syme SL (1979). Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 109(2), 186–204. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan A, & Schuth M (2014). Early retirement, mental health, and social networks. In Wise D (Ed.), Discoveries in the Economics of Aging (pp. 225–250). University of Chicago Press. 10.7208/chicago/9780226146126.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bound J, & Krueger AB (1991). The extent of measurement error in longitudinal earnings data: Do two wrongs make a right? Journal of Labor Economics, 9(1), 1–24. 10.1086/298256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bound J, Schoenbaum M, Stinebrickner TR, & Waidmann T (1999). The dynamic effects of health on the labor force transitions of older workers. Labour Economics, 6(2), 179–202. 10.1016/S0927-5371(99)00015-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buhmann B, Rainwater L, Schmaus G, & Smeeding TM (1988). Equivalence scales, well-being, inequality, and poverty: sensitivity estimates across ten countries using the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database. Review of Income and Wealth, 34(2), 115–142. 10.1111/j.1475-4991.1988.tb00564.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byers AL, Covinsky KE, Barnes DE, & Yaffe K (2012). Dysthymia and depression decrease risk of dementia and mortality among older veterans. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(8), 664–672. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e31822001c1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, & Liu G (2012). The health implications of grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67B (1), 99–112. 10.1093/geronb/gbr132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Ying J, Ingles J, Zhang D, Rajbhandari-Thapa J, Wang R, Emerson KG, & Feng Z (2020). Gender differential impact of bereavement on health outcomes: evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, 2011–2015. BMC Psychiatry Public, 20(1). 10.1186/s12888-020-02916-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XX, Giles J, Yao Y, Yip WN, Meng QQ, Berkman L, Chen H, Chen X, Feng J, Feng ZL, Glinskaya E, Gong JQ, Hu P, Kan HD, Lei XY, Liu X, Steptoe A, Wang GW, Wang H, Wang HL, Wang XY, Wang YF, Yang L, Zhang LX, Zhang Q, Wu J, Wu ZY, Strauss J, Smith J, Zhao YH (2022). The path to healthy ageing in China: A Peking University–Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 400(10367), 1967–2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AL, & Goldman N (2008). Perceived social position and health in older adults in Taiwan. Social Science & Medicine, 66(3), 536–544. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa DL (1997). Displacing the family: union army pensions and elderly living arrangements. Journal of Political Economy, 105(6), 1269–1292. 10.1086/516392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costa DL, 1999. A house of her own: old age assistance and the living arrangements of older nonmarried women. Journal of Public Economics, 72(1), 39–59. 10.1016/S0047-2727(98)00094-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa J, Evans WN, 2008. Heightened mortality after the death of a spouse: marriage protection or marriage selection? Journal of Health Economics, 27(5), 1326–1342. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang H, Feng J, 2018. The Chinese pension system. NBER Working Paper, No. 25088, September 2018. 10.3386/w25088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giles J, Lei XY, Wang GW, Wang YF, & Zhao YH (2023). One Country, Two Systems: Evidence on Retirement Patterns in China. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 22(2): 188–210. 10.1017/S1474747221000391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles J, & Mu R (2007). Elderly parent health and the migration decisions of adult children: evidence from rural China. Demography, 44(2), 265–288. 10.1353/dem.2007.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillen M, & Kim H (2009). Older women and poverty transition: consequences of income source changes from widowhood. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 28(3), 320–341. 10.1177/0733464808326953 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goda GS, Shoven JB, & Slavov SN (2013). Does widowhood explain gender differences in out-of-pocket medical spending among the elderly? Journal of Health Economics, 32(3), 647–658. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JQ, Wang GW, Wang YF, & Zhao YH (2022). Consumption and poverty of older Chinese: 2011–2020. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 23. 10.1016/j.jeoa.2022.100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, & Goldman N (1990). Mortality differentials by marital status: an international comparison. Demography, 27(2), 233–250. 10.2307/2061451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu YQ, Lei XY, Smith J, & Zhao YH (2012). Effects of social activities on cognitive functions: Evidence from CHARLS. In Maimundar M and Smith JP (eds.), Aging in Asia: Findings from New and Emerging Data Initiatives, Committee on Policy Research and Data Needs to Meet the Challenge of Aging in Asia, pp.279–308, National Research Council. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, & Waite LJ (2009). Marital biography and health at mid-life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(3), 344–358. 10.1177/002214650905000307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes ME, Waite LJ, LaPierre TA, & Luo Y (2007). All in the family: the impact of caring for grandchildren on grandparents' health. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(2), S108–S119. 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford TL (2001). The economic consequences of widowhood on elderly women in the United States and Germany. The Gerontologist, 41(1), 103–110. 10.1093/geront/41.1.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, & Benyamini Y (1997). Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(1), 21–37. 10.2307/2955359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwashyna TJ, & Christakis NA (2004). Marriage, widowhood, and healthcare use. Social Science & Medicine, 57(11), 2137–2147. 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00546-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei XY, Hu Y, McArdle JJ, Smith JP, & Zhao YH (2012). Gender differences in cognition among older adults in China. The Journal of Human Resources, 47(4), 951–971. 10.3368/jhr.47.4.951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei XY, Strauss J, Tian M, & Zhao YH (2015). Living arrangements of the elderly in China: evidence from the CHARLS national baseline. China Economic Journal, 8(3), 191–214. 10.1080/17538963.2015.1102473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei XY, Sun X, Strauss J, Zhang P, & Zhao YH (2014). Depressive symptoms and SES among the mid-aged and elderly in China: evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study national baseline. Social Science Medicine, 120, 224–232. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei XY, Giles J, Hu YQ, Park A, Strauss J, Zhao YH (2012). Patterns and correlates of intergenerational non-time transfers: evidence from CHARLS. In Majmundar M and Smith JP (eds.), Aging in Asia: Findings from New and Emerging Data Initiatives, Committee on Policy Research and Data Needs to Meet the Challenge of Aging in Asia, pp.207–228, National Research Council. Washington D.C.: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Liang J, Toler A, & Gu S (2005). Widowhood and depressive symptoms among older Chinese: do gender and source of support make a difference? Social Science & Medicine, 2005, 60(3), 637–647. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, & Panis CW (1996). Marital status and mortality: the role of health. Demography, 33(3), 313–327. 10.2307/2061764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, & Waite LJ (1995). 'Til death do us part: marital disruption and mortality. American Journal of Sociology, 100(5), 1131–1156. 10.1086/230634 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H (2012). Marital dissolution and self-rated health: age trajectories and birth cohort variations. Social Science & Medicine, 74(7), 1107–1116. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks NF, & Lambert JD (1998). Marital status continuity and change among young and midlife adults: longitudinal effects on psychological well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 19(6), 652–686. 10.1177/019251398019006001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Fisher GG, & Kadlec KM (2007). Latent variable analyses of age trends of cognition in the Health and Retirement Study, 1992–2004. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 525–545. 10.1037/0882-7974.22.3.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, & Stellar E (1993). Stress and the individual: mechanisms leading to disease. Archives of Internal Medicine, 153(18), 2093–2101. 10.1001/archinte.1993.00410180039004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry K, & Schoeni RF (2005). Widow(er) poverty and out-of-pocket medical expenditures near the end of life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(3), S160–S168. 10.1093/geronb/60.3.S160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JE (2000). Marital protection and marital selection: evidence from a historical-prospective sample of American men. Demography, 37(4), 511–521. 10.1353/dem.2000.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics, 2020. Tabulation on the 2020 Population Census of the People's Republic of China. China Population Census Yearbook 2020. China Statistics Press. http://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/7rp/indexch.htm [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB, Nieto FJ, Guidry U, Lind BK, Redline S, Shahar E, Pickering TG, & Quan SF (2001). Relation of sleep-disordered breathing to cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Sleep Heart Health Study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 154(1), 50–59. 10.1093/aje/154.1.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton EC (2000). Chapter 17: Long-term care. In Culyer AJ and Newhouse JP (Eds.), Handbook of Health Economics, 1(B), (pp. 955–994). Elsevier. 10.1016/S1574-0064(00)80030-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosnick C, Small B, & Burton A (2010). The effect of spousal bereavement on cognitive functioning in a sample of older adults. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 17(3), 257–269. 10.1080/13825580903042692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson I, & Umberson DJ (2013). Widowhood and depression: new light on gender differences, selection, and psychological adjustment. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B, 69B(1), 135–145. 10.1093/geronb/gbt058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonova E (2013). Marriage, bereavement and mortality: the role of health care utilization. Journal of Health Economics, 32(1), 33–50. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2012.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW (2002). Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status, and mental health. American Journal of Sociology, 107(4), 1065–1096. 10.1086/339225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP, McArdle JJ, & Willis R (2010). Financial decision making and cognition in a family context. The Economic Journal, 120(548), F363–F380. 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02394.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JP, Tian M, Zhao YH (2013). Community effects on elderly health: Evidence from CHARLS national baseline. The Journal of the Economics of Ageing, 1(2): 50–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudha S, Suchindran C, Mutran EJ, Rajan SI, & Sarma PS (2006). Marital status, family ties, and self-rated health among elders in South India. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 21(3–4), 103–120. 10.1007/s10823-006-9027-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trovato F, & Lauris G (1989). Marital status and mortality in Canada: 1951–1981. Journal of Marriage and Family, 51(4), 907–922. 10.2307/353204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng FM, Petrie D, Wang S, Macduff C, & Stephen AI (2017). The impact of spousal bereavement on hospitalisations: evidence from the Scottish Longitudinal Study. Health Economics, 27, 120–138. 10.1002/hec.3573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D (1992). Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Social Science & Medicine, 34(8), 907–917. 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite LJ, & Gallagher M (2001). The Case for Marriage: Why Married People are Happier, Healthier, and Better Off Financially. Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RB, & Herzog AR (1995). Overview of the health measures in the Health and Retirement Study. The Journal of Human Resources, 30, S84–S107. 10.2307/146279 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward L, Mathias JL, & Hitchings SE (2007). Relationships between bereavement and cognitive functioning in older adults. Gerontology, 53(6), 362–372. 10.1159/000104787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, & Hayward M (2006). Gender, the marital life course, and cardiovascular health in late midlife. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 639–657. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00280.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Li LW, Xu H, & Liu J (2019). Does widowhood affect cognitive function among Chinese older adults? SSM - Population Health, 7, 100329. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.100329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao R, & Zhao Y (2018). The gender pension gap in China. Feminist Economics, 24(2), 218–239. 10.1080/13545701.2017.1411601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]