Abstract

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disorder with limited treatment options for adolescents with moderate-to-severe disease. Lebrikizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin (IL)-13, demonstrated clinical benefit in previous Phase 3 trials: ADvocate1 (NCT04146363), ADvocate2 (NCT04178967), and ADhere (NCT04250337). We report 52-week safety and efficacy outcomes from ADore (NCT04250350), a Phase 3, open-label study of lebrikizumab in adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe AD. The primary endpoint was to describe the proportion of patients who discontinued from study treatment because of adverse events (AEs) through the last treatment visit.

Methods

Adolescent patients (N = 206) (≥ 12 to < 18 years old, weighing ≥ 40 kg) with moderate-to-severe AD received subcutaneous lebrikizumab 500 mg loading doses at baseline and Week 2, followed by 250 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) thereafter. Safety was monitored using reported AEs, AEs leading to treatment discontinuation, vital signs, growth assessments, and laboratory testing. Efficacy analyses included Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA), Body Surface Area (BSA), (Children’s) Dermatology Life Quality Index ((C)DLQI), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Anxiety, and PROMIS Depression.

Results

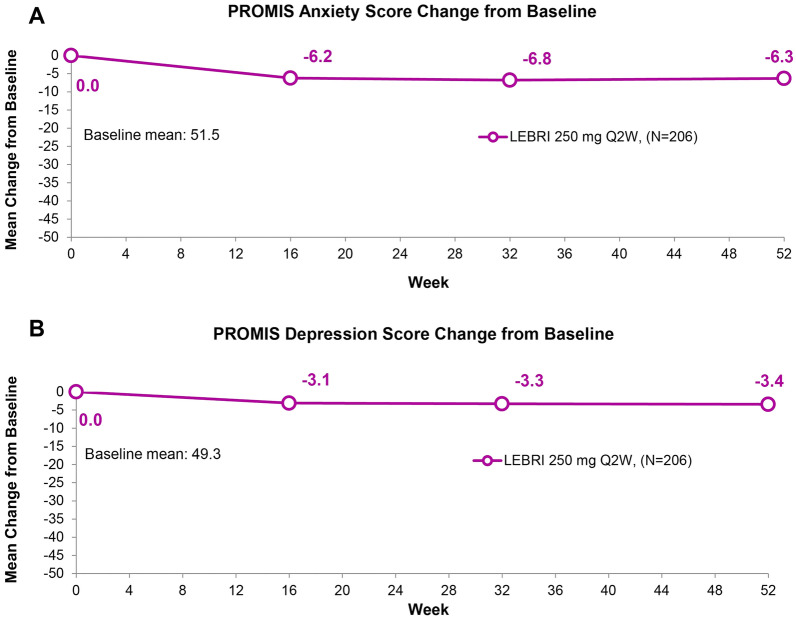

172 patients completed the treatment period. Low frequencies of SAEs (n = 5, 2.4%) and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation (n = 5, 2.4%) were reported. Overall, 134 patients (65%) reported at least one treatment-emergent AE (TEAE), most being mild or moderate in severity. In total, 62.6% achieved IGA (0,1) with ≥ 2-point improvement from baseline and 81.9% achieved EASI-75 by Week 52. The EASI mean percentage improvement from baseline to Week 52 was 86.0%. Mean BSA at baseline was 45.4%, decreasing to 8.4% by Week 52. Improvements in mean change from baseline (CFB) to Week 52 were observed in DLQI (baseline 12.3; CFB − 8.9), CDLQI (baseline 10.1; CFB − 6.5), PROMIS Anxiety (baseline 51.5; CFB − 6.3), and PROMIS Depression (baseline 49.3; CFB − 3.4) scores.

Conclusions

Lebrikizumab 250 mg Q2W had a safety profile consistent with previous trials and significantly improved AD symptoms and quality of life, with meaningful responses at Week 16 increasing by Week 52.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT04250350.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-023-00942-y.

Keywords: Adolescents, Efficacy, IL-13, Lebrikizumab, Moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis, Safety

Plain Language Summary: Lebrikizumab in Adolescent Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disease that affects up to 15% of adolescents worldwide, with up to 50% suffering from moderate-to-severe disease. Signs and symptoms include dry, cracked skin; redness; itching; and painful lesions, which can negatively affect quality of life and lead to complications, including skin infections. Adolescents also report increased rates of anxiety and stress. Lebrikizumab is a novel monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity and slow off-rate to interleukin (IL)-13, the key cytokine in atopic dermatitis, blocking the downstream effects of IL-13 with high potency. Lebrikizumab has been shown previously to improve symptoms of atopic dermatitis, including itch, skin clearance, and quality of life in ADvocate1, ADvocate2 and ADhere. The ADore study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of lebrikizumab in adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Investigators recruited patients ≥ 12 to < 18 years old, weighing ≥ 40 kg, from Australia, Canada, Poland, and the US who were diagnosed with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. These patients received a loading dose of 500 mg of lebrikizumab at Weeks 0 and 2, followed by 250 mg every 2 weeks for 52 weeks. The safety profile of lebrikizumab was consistent with previously published reports, with mostly mild or moderate adverse events, which did not lead to treatment discontinuation. Lebrikizumab improved skin clearance; 62.6% of patients had clear or almost clear skin by the end of the trial. Lebrikizumab also improved the patients’ quality of life. These safety and efficacy results support lebrikizumab’s role in treating adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis.

Safety and Efficacy of Lebrikizumab in Adolescent Patients with Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis: A 52-Week, Open-Label, Phase 3 Study (MP4 44681 KB)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-023-00942-y.

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Lebrikizumab (interleukin (IL)-13 inhibitor) has shown efficacy up to Week 52 in Phase 3 monotherapy trials (ADvocate 1 and 2) and in combination with topical corticosteroids (ADhere) for the treatment of adults and adolescents with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. |

| This 52-week open-label study is the first to evaluate the safety and efficacy of lebrikizumab exclusively in adolescent patients (≥ 12 to < 18 years old) with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Lebrikizumab demonstrated a safety profile that was consistent with the established safety profile previously published and showed robust and sustained efficacy in this population with meaningful Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) and Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) responses. |

| This study suggests that lebrikizumab 250 mg every 2 weeks (Q2W) has positive benefit-risk and efficacy profiles in adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis up to 52 weeks of continuous treatment. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a video abstract to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22801229.

Introduction

The prevalence of AD in adolescents is estimated at approximately 15% worldwide, with up to 50% suffering from moderate-to-severe disease [1]. Adolescent populations with moderate-to-severe AD have also been reported to have a higher baseline disease severity, rate of atopic comorbidities, and use of rescue treatments compared to adult patients [2].

AD in adolescents is associated with poorer performance in school, difficulties in forming social relationships, and increased rates of anxiety and depression [2]. A cross-sectional study reported that 90.0% of adolescent patients reported intense itching, 69.2% sleep disturbance, 60.2% fatigue, and 74.1% physical deterioration of AD lesions with stress during high school [3]. Furthermore, a study of Norwegian adolescents with AD showed a correlation between clinical severity and increased levels of psychological stress [4], and a further study reported that among clinical features of AD, itch was significantly correlated with levels of anxiety [5].

Current therapeutic approaches for moderate-to-severe AD in adolescents include regular use of topical emollients and anti-inflammatory agents such as topical corticosteroids (TCS), calcineurin inhibitors (TCI), and phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitors. The currently approved systemic agents for moderate-to-severe AD include the biologics dupilumab and tralokinumab and the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors upadacitinib, baricitinib, and abrocitinib [2, 6–9]. Due to the heterogeneity of AD, additional systemic therapy options suitable for long-term management of moderate-to-severe AD in adolescents are required [10, 11].

Lebrikizumab is a novel, high-affinity monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to interleukin (IL)-13, the dominant skin cytokine in AD pathogenesis [12]. Lebrikizumab prevents the formation of the IL-13Rα1/IL-4Rα heterodimer receptor signaling complex, thus blocking IL-13 bioactivity. Lebrikizumab exhibits high binding affinity, a slow dissociation rate, and neutralizes IL-13 with high potency [13]. The use of lebrikizumab in AD is supported by studies that have shown that IL-13 expression levels in AD lesional skin are correlated with disease severity [14, 15]. Lebrikizumab has demonstrated clinical benefit in adolescent and adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD in three Phase 3 trials: two 52-week monotherapy studies (ADvocate1 [NCT04146363] and ADvocate2 [NCT04178967]) and a 16-week combination study with TCS (ADhere [NCT04250337]) [16, 17].

The objective of this study was to describe the 52-week safety and efficacy outcomes from ADore (NCT04250350), a Phase 3, open-label study of lebrikizumab in adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe AD. The primary endpoint was to describe the proportion of patients who discontinued from study treatment because of adverse events (AEs) through the last treatment visit. The secondary endpoints included the percentage of patients who achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 and a ≥ 2-point improvement from baseline; percentage of patients achieving ≥ 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index from baseline (EASI-75), EASI-50, and EASI-90; percentage change from baseline in EASI score at Week 52; mean change from baseline in Body Surface Area (BSA); mean change from baseline in Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) measures of anxiety and depression; and mean change from baseline in Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Children’s DLQI (CDLQI).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

ADore was a multicenter, open-label, single-arm Phase 3 clinical trial designed to assess the safety and efficacy of lebrikizumab in adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe AD. The study population was recruited from 55 centers in Australia (4), Canada (5), Poland (9), and the US (37) between 27 February 2020 and 22 June 2022. This study was conducted in accordance with the protocol and consensus ethical principles derived from international guidelines including the Declaration of Helsinki and Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, applicable ICH GCP guidelines, and applicable laws and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before study procedures were initiated. The informed consent met the requirements of 21 CFR 50, local regulations, ICH guidelines on Good Clinical Practice, HIPAA requirements, and the IRB/IEC of the study center. The written consent of the parent or legal guardian, as well as the assent of the minor, was obtained.

Eligible patients included adolescents (≥ 12 to < 18 years old, weighing ≥ 40 kg) with moderate-to-severe AD for at least 1 year, defined according to the American Academy of Dermatology Consensus Criteria [18], and with an EASI score of ≥ 16, an IGA score of ≥ 3, and BSA of ≥ 10%. Patients were not eligible if they had uncontrolled chronic disease that might require bursts of oral corticosteroids, had been diagnosed with an active endoparasitic infection or were at high risk of these infections, or had a history of anaphylaxis as defined by the Sampson criteria [19]. Patients with a history of malignancy, including mycosis fungoides, within 5 years before the screening visit; severe concomitant illness (es); and any medical or psychological condition that would adversely affect the patient’s participation in the study were also ineligible. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in supplementary material.

At baseline and Week 2, all patients were administered a loading dose of 500 mg lebrikizumab by subcutaneous (SC) injection, followed by 250 mg lebrikizumab SC every 2 weeks (Q2W) through Week 52. Adolescent patients in this study received the same dose of lebrikizumab as was administered to adult and adolescent patients in previous lebrikizumab Phase 3 clinical trials, based on an evaluation of safety, efficacy, and pharmacokinetic data. Efficacy assessments were performed at baseline, Weeks 4, 8, 16, 32, and 52 for EASI, IGA, and BSA. DLQI, CDLQI, and PROMIS assessments were carried out at baseline, Weeks 16, 32, and 52.

Patients were required to wash out from topical and systemic therapy prior to enrollment. The use of systemic medications for conditions known to affect AD, including mycophenolate mofetil, interferon (IFN)-y, JAK inhibitors, cyclosporine, azathioprine, methotrexate, topical crisaborole, phototherapy, or photochemotherapy, was not permitted during the study. Systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of AEs or other medical conditions were permitted for short periods of time as per medical judgment. However, patients requiring systemic corticosteroids for > 2 weeks were discontinued from the study, and this was assessed on a case-by-case basis. Non-medicated moisturizers were used daily during the study. The use of any potency topical corticosteroid, topical calcineurin inhibitor, or topical PDE-4 inhibitor was permitted as rescue treatment throughout the trial when a patient experienced clinical worsening of symptoms that were intolerable.

Safety and Efficacy Assessments

The primary endpoint of ADore was the proportion of patients who discontinued from study treatment because of AEs through the last treatment visit. Safety was assessed by monitoring AEs, including serious AEs (SAEs), AEs leading to treatment discontinuation, vital signs, growth assessments including height and weight, and laboratory testing. An independent external Data Safety Monitoring Board monitored patient safety by conducting periodic reviews of accumulated safety data throughout the trial.

The secondary endpoints included the percentage of patients who achieved an IGA score of 0 or 1 and a ≥ 2-point improvement from baseline; percentages of patients achieving ≥ 75% improvement in EASI from baseline (EASI-75), EASI-50, and EASI-90; percentage change from baseline in EASI score at Week 52; and mean change from baseline in BSA. Quality of life was assessed using the DLQI, CDLQI, and PROMIS measures of anxiety and depression. The DLQI (> 16 years old) and CDLQI (≤ 16 years) asked about the impact of AD on quality of life over the last week. The PROMIS Anxiety Short Form (8 questions) and PROMIS Depression Short Form (8 questions) for pediatric patients (ages 8 to < 18 years) were used in this study, which assessed the patients’ symptoms over the previous week.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size of 206 patients was based on regulatory requirements for safety exposure in adolescents. All patients who received at least one confirmed dose of lebrikizumab 250 mg were included in the safety population, which was used for all safety and efficacy analyses, as well as for summarizing patient demographic and baseline characteristics.

All data collected after treatment discontinuation due to lack of efficacy were imputed as non-responders by setting values to the subject’s baseline value. Data collected after treatment discontinuation due to other reasons were set to missing and imputed with multiple imputation. Patients requiring long-term use of systemic rescue medication were discontinued from the study as per the protocol requirements. These patients were imputed as non-responders after their date of treatment discontinuation. All other uses of rescue medication were not considered intercurrent events. Remaining missing data were imputed with multiple imputation.

No inferential testing was performed in this study. For categorical parameters, the number and percentage of patients in each category was reported. A 95% confidence interval constructed using the asymptotic method without continuity correction for the percentage was also provided for efficacy analyses. For continuous parameters, descriptive statistics included number of patients, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum, and maximum. All summaries were performed using SAS Software, version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Disposition, Baseline Demographics, and Disease Characteristics

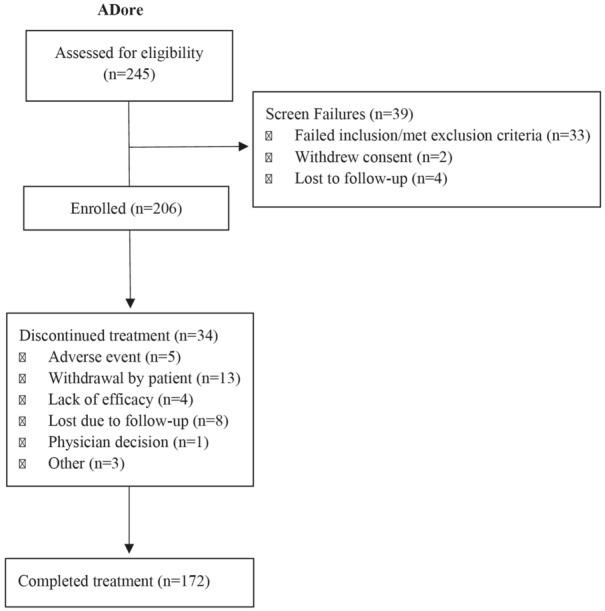

A total of 245 patients entered the study: 39 failed screening, 206 received treatment, and 172 completed the treatment period (Fig. 1). The most frequent reasons for treatment discontinuation were withdrawal by subject (n = 13, 6.3%) and lost to follow-up (n = 8, 3.9%). The population was largely balanced between females (52.4%) and males (47.6%). The mean (SD) age of patients at baseline was approximately 14.6 (1.8) years, the mean (SD) weight was 66.3 (20.4) kg, and the mean (SD) disease duration since AD onset was 12.4 (3.9) years. At baseline, 73 patients (35.4%) had severe AD (IGA score 4), and the remainder had moderate AD (IGA score 3). The mean EASI score was 28.5, and the mean BSA was 45.4% (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram outlining patient disposition, including patient numbers assessed for eligibility (N = 245), excluded (N = 39), enrolled (N = 206), discontinued treatment (N = 34), and completed treatment (N = 172)

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics in the safety population

| Attribute | LEB 250 mg Q2W (N = 206) |

|---|---|

| Baseline demographics | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 14.6 (1.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 108 (52.4) |

| Male, n (%) | 98 (47.6) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 138 (67.0) |

| Black or African American | 26 (12.6) |

| Asian | 24 (11.7) |

| Multiple | 11 (5.3) |

| Not reported | 3 (1.5) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (1.0) |

| Othera | 2 (1.0) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 66.3 (20.4) |

| ≥ 40 and < 60 kg, n (%) | 92 (44.7) |

| ≥ 60 to < 100 kg, n (%) | 95 (46.1) |

| ≥ 100 kg, n (%) | 19 (9.2) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 24.3 (6.3) |

| Country, n (%) | |

| US | 111 (53.9) |

| Poland | 63 (30.6) |

| Canada | 20 (9.7) |

| Australia | 12 (5.8) |

| Disease characteristics | |

| Duration since AD onset (years), mean (SD) | 12.4 (3.9) |

| IGA score, n (%) | |

| 3, moderate | 133 (64.6) |

| 4, severe | 73 (35.4) |

| EASI, mean (SD) | 28.5 (11.8) |

| %BSA affected, mean (SD) | 45.4 (22.3) |

| Baseline DLQI, mean (SD) | 12.3 (5.5) |

| Baseline CDLQI, mean (SD) | 10.1 (5.7) |

| Baseline PROMIS Anxiety Score, mean (SD) | 51.5 (11.2) |

| Baseline PROMIS Depression Score, mean (SD) | 49.3 (11.4) |

| AD treatment history at Baseline | |

| None | 5 (2.4) |

| Topical corticosteroids | 200 (97.1) |

| Topical calcineurin inhibitors | 97 (47.1) |

| Systemic treatment | 90 (43.7) |

| Systemic corticosteroids | 64 (31.1) |

| Phototherapy | 27 (13.1) |

| Cyclosporine | 17 (8.3) |

| Janus kinase inhibitors | 12 (5.8) |

| Dupilumab | 9 (4.4) |

| Methotrexate | 4 (1.9) |

| Photochemotherapy (PUVA) | 2 (1.0) |

| Azathioprine | 1 (0.5) |

| Other biologics (eg, cell depleting biologics) | 1 (0.5) |

| Tralokinumab | 1 (0.5) |

| Other non-biologic medication/treatmentb | 40 (19.4) |

Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified

Abbreviations: AD atopic dermatitis, BSA Body Surface Area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, LEB lebrikizumab, N number of patients in the analysis population, n number of patients in the specified category, PROMIS Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, SD standard deviation, Q2W every 2 weeks, US United States

a1 patient reported Native American and 1 reported Mexican

bMajority (50%) of other treatments included anti-histamine drugs

Safety

There were 134 patients (65%) who reported at least one treatment-emergent AE (TEAE; Table 2). Most TEAEs were non-serious and mild (33.5%) or moderate (29.6%) in severity. TEAEs that were most frequently reported (> 5%) during the study were AD (13.1%), nasopharyngitis (9.7%), COVID-19 infection (8.7%), upper respiratory tract infection (6.3%), headache (5.8%), and oral herpes (5.3%). Reported SAEs were atopic dermatitis, bile duct stone, cardiac arrest, allergic conjunctivitis, multiple injuries, and testicular torsion. No single SAE was reported by more than one patient. The allergic conjunctivitis SAE was assessed as related to study treatment and resulted in treatment discontinuation, while the remainder of the events were assessed as unrelated by the investigator.

Table 2.

Overview of AEs through Week 52 in the safety population. Data are presented as n (%)

| Safety events | LEB 250 mg Q2W (N = 206) n (%) |

|---|---|

| TEAEs | 134 (65.0) |

| Mild | 69 (33.5) |

| Moderate | 61 (29.6) |

| Severe | 4 (1.9) |

| SAEs | 5 (2.4) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1 (0.5) |

| Bile duct stone | 1 (0.5) |

| Cardiac arresta | 1 (0.5) |

| Conjunctivitis allergicb | 1 (0.5) |

| Multiple injuriesc | 1 (0.5) |

| Testicular torsiond | 1 (1.0) |

| Deatha | 1 (0.5) |

| AEs leading to treatment discontinuation | 5 (2.4) |

| Cardiac arresta | 1 (0.5) |

| Conjunctivitis allergicb | 1 (0.5) |

| Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | 1 (0.5) |

| Hemolytic anemia | 1 (0.5) |

| Injection site pain | 1 (0.5) |

| TEAEs reported in ≥ 2% of patientse | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 27 (13.1) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 20 (9.7) |

| COVID-19 | 18 (8.7) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 13 (6.3) |

| Headache | 12 (5.8) |

| Oral herpes | 11 (5.3) |

| Conjunctivitis | 10 (4.9) |

| Eosinophilia | 8 (3.9) |

| Acne | 7 (3.4) |

| Cough | 7 (3.4) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (2.9) |

| Urticaria | 6 (2.9) |

| Herpes dermatitis | 5 (2.4) |

| Pruritus | 5 (2.4) |

| Nausea | 5 (2.4) |

| AEs of clinical interest | |

| Conjunctivitis clusterf | 14 (6.8) |

| Conjunctivitis | 10 (4.9) |

| Conjunctivitis allergic | 4 (1.9) |

| Conjunctivitis bacterial | 1 (0.5) |

| Keratitis clusterg | 1 (0.5) |

| Atopic keratoconjunctivitis | 1 (0.5) |

| Injection site reactionsh | 5 (2.4) |

| Overall infections | 74 (35.9) |

| Skin infections | 5 (2.4) |

| Herpes infectioni | 15 (7.3) |

| Zoster infections | 0 (0) |

| Parasitic infections | 0 (0) |

| Potential opportunistic infectionsj | 4 (1.9) |

| Confirmed opportunistic infections | 0 (0) |

| Eosinophiliak | 8 (3.9) |

| Eosinophil-related disorders | 0 (0) |

| Anaphylaxis | 0 (0) |

| Malignancyl | 1 (0.5) |

| NMSC | 0 (0) |

| Non-NMSC | 1 (0.5) |

Abbreviations: AE adverse event, LEB lebrikizumab, MedDRA Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities, N number of patients in the analysis population, n number of patients in the specified category, NMCS non-melanoma skin cancer, PT preferred term, Q2W every 2 weeks, SAE serious adverse event, TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

aSAEs and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation are inclusive of death. Death was a single patient with cardiac arrest that was fatal, serious, and led to discontinuation. Hospital records noted cardiac arrest and COVID-19 as cause of death, and the death was assessed by investigator as related to COVID-19 and not to the study drug

bConjunctivitis allergic event led to treatment discontinuation

cMultiple injuries after falling from a bicycle

dDenominator-adjusted because of gender-specific event for males: N = 98

eTEAEs are defined using the MedDRA preferred terms

fConjunctivitis cluster includes the following preferred terms: conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis allergic, conjunctivitis bacterial, conjunctivitis viral, and giant papillary conjunctivitis

gKeratitis cluster includes the following preferred terms: keratitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, allergic keratitis, ulcerative keratitis, and vernal keratoconjunctivitis

hInjection site reactions were defined as MedDRA based on high level term Injection Site Reactions

iHerpes infections were defined using MedDRA high-level term Herpes Viral Infections. No herpes zoster was reported

jAll infections were non-serious and all potential opportunistic infections were medically reviewed prior to database lock and were assessed as not opportunistic based on the Winthrop criteria [20]

kEosinophilia was reported as an AE by the investigator

lMalignancy event was a suspected case of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

The proportion of patients who discontinued study treatment because of AEs through the last treatment visit is summarized in Table 2. Five patients (2.4%) reported at least one AE leading to permanent discontinuation of study treatment. Events that led to treatment discontinuation included cardiac arrest, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, hemolytic anemia, allergic conjunctivitis, and injection site pain, reported by one patient each. One death occurred during the study (cardiac arrest); this was assessed as related to COVID-19 and assessed by investigator as not related to the study drug. The suspected case of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and event of hemolytic anemia were also assessed by the investigator as not related to the study drug.

Protocol-defined AEs of special interest (AESIs) included conjunctivitis cluster (n = 14, 6.8%), herpes infection (n = 15, 7.3%), and parasitic infections (0%). Conjunctivitis cluster includes the following preferred terms: conjunctivitis, conjunctivitis allergic, conjunctivitis bacterial, conjunctivitis viral, and giant papillary conjunctivitis. All potential opportunistic infections (n = 4, 1.9%) were medically reviewed and were assessed as not opportunistic based on the Winthrop criteria [20]. Potential opportunistic infections included herpes simplex (n = 3, 1.5%), eczema herpeticum (n = 1, 0.5%), and herpes ophthalmic (n = 1, 0.5%), and none of these were confirmed as opportunistic based on the Winthrop criteria [20]. Skin infections were reported in five patients (2.4%), and no severe infection was reported during the study. Injection site reactions were reported for five patients (2.4%), and all events were mild or moderate in severity. One patient reported injection site pain at the baseline visit. This event was mild in severity, and the patient discontinued treatment because of this AE. No anaphylactic reactions were reported.

Eosinophilia, defined using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) preferred terms, was reported as a TEAE for eight patients (3.9%); none of these events led to treatment discontinuation. Approximately 30% of patients had increased post-baseline eosinophil counts at any time. Mean and median blood eosinophil counts remained stable from baseline through Week 52. No severe (> 5000 per μl) increases in blood eosinophils were observed. The changes were not considered clinically important, and no TEAEs due to eosinophil-related disorders were reported.

Growth was monitored during the study using height and weight. Mean changes from baseline to Week 16 for z-scores were near zero (± 0.04) for all parameters, and the same was observed from baseline to Week 52. The data suggested no clinically significant differences in the growth parameters (height, weight, and body mass index) between baseline and end of the study (data not shown).

Efficacy

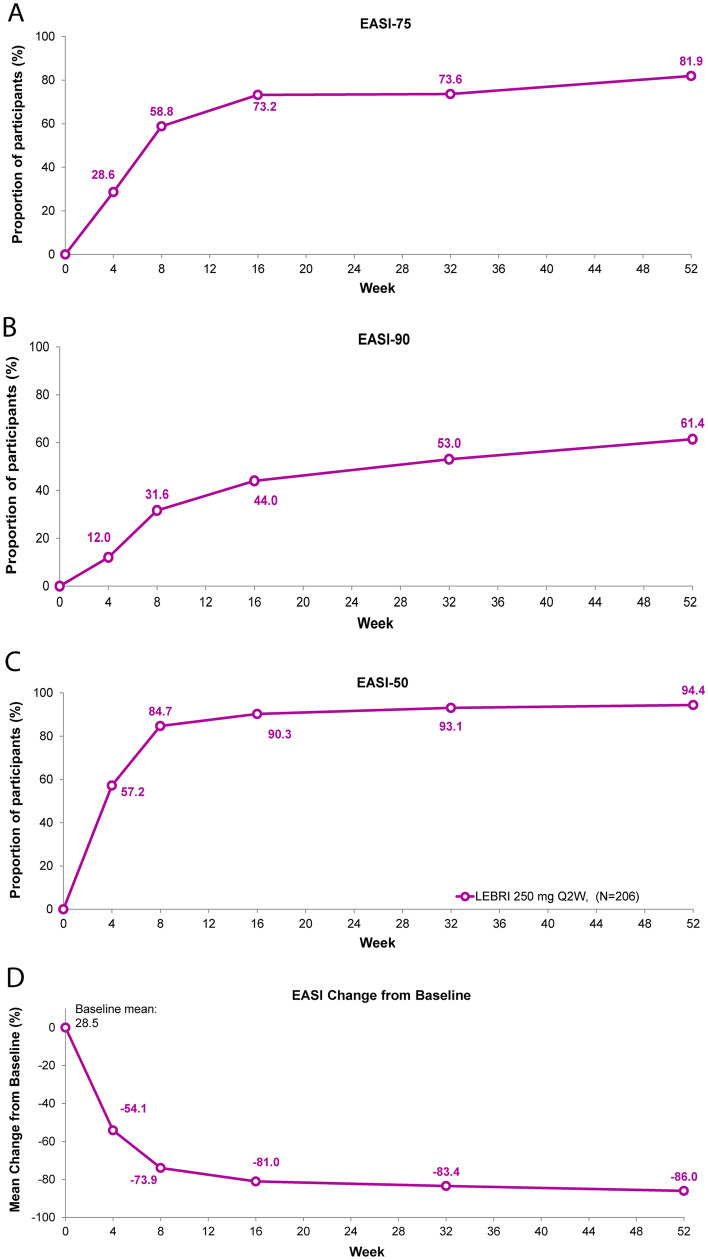

All efficacy analyses were conducted in the safety population (Table 3). EASI-75 was achieved by 28.6% of patients at the first study measurement at Week 4, increasing to 73.2% at Week 16 and 81.9% at Week 52 (Fig. 2A). EASI-90 was achieved by 12% of patients at the first study measurement at Week 4, 44.0% at Week 16, and 61.4% at Week 52 (Fig. 2B). Similarly, EASI-50 was achieved by 57.2% of patients at the first study measurement at Week 4, increasing to 90.3% at Week 16, and 94.4% of patients by Week 52 (Fig. 2C). The EASI percentage change from baseline was − 54.1% at Week 4, increasing to − 81.0% by Week 16 and to − 86.0% by Week 52 (Fig. 2D).

Table 3.

Summary of efficacy outcomes in the safety population

| Efficacy outcome | LEB 250 mg Q2W |

|---|---|

| EASI-75 | |

| Week 4 | 59 (28.6) [22.4, 34.8] |

| Week 16 | 151 (73.2) [67.0, 79.4] |

| Week 52 | 169 (81.9) [76.5, 87.4] |

| EASI-90 | |

| Week 4 | 25 (12.0) [7.5, 16.5] |

| Week 16 | 91 (44.0) [37.1, 50.9] |

| Week 52 | 127 (61.4) [54.5, 68.3] |

| EASI-50 | |

| Week 4 | 118 (57.2) [50.4, 64.0] |

| Week 16 | 186 (90.3) [86.2, 94.5] |

| Week 52 | 194 (94.4) [91.1, 97.7] |

| EASI % change from baseline, mean (SE) | |

| Week 4 | − 54.1 (2.1) |

| Week 16 | − 81.0 (1.6) |

| Week 52 | − 86.0 (1.6) |

| IGA (0,1) with ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline | |

| Week 4 | 30 (14.4) [9.5, 19.2] |

| Week 16 | 95 (46.3) [39.3, 53.2] |

| Week 52 | 129 (62.6) [55.6, 69.6] |

| BSA change from baseline, mean (SD) | |

| Week 4 | − 19.9 (16.9) |

| Week 16 | − 33.5 (19.4) |

| Week 52 | − 37.6 (21.1) |

| DLQI change from baseline, mean (SE) | |

| Week 16 | − 6.9 (0.9) |

| Week 32 | − 8.6 (0.9) |

| Week 52 | − 8.9 (0.9) |

| CDLQI change from baseline, mean (SE) | |

| Week 16 | − 6.1 (0.4) |

| Week 32 | − 6.2 (0.4) |

| Week 52 | − 6.5 (0.5) |

| PROMIS anxiety score change from baseline, mean (SD) | |

| Week 16 | − 6.2 (9.4) |

| Week 32 | − 6.8 (10.3) |

| Week 52 | − 6.3 (10.0) |

| PROMIS depression score change from baseline, mean (SD) | |

| Week 16 | − 3.1 (8.5) |

| Week 32 | − 3.3 (8.7) |

| Week 52 | − 3.4 (9.1) |

Data are presented as N (%) [95% CI] unless specified in the table

Abbreviations: BSA Body Surface Area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-50 50% reduction in EASI, EASI-75 75% reduction in EASI, EASI-90 90% reduction in EASI, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, LEB lebrikizumab, n number of patients in the specified category, PROMIS Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, Q2W every 2 weeks, SD standard deviation, SE standard error

Fig. 2.

Time course response for EASI clinical outcomes. Percentage of patients (%) achieving EASI-75 (A), EASI-90 (B), EASI-50 (C), and EASI percentage change from baseline (D) through 52 weeks. Missing data due to lack of efficacy were imputed with non-responder imputation. Other missing data were imputed with multiple imputation. Abbreviations: EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-50 50% reduction in EASI, EASI-75 75% reduction in EASI, EASI-90 90% reduction in EASI, LEBRI lebrikizumab, Q2W every 2 weeks

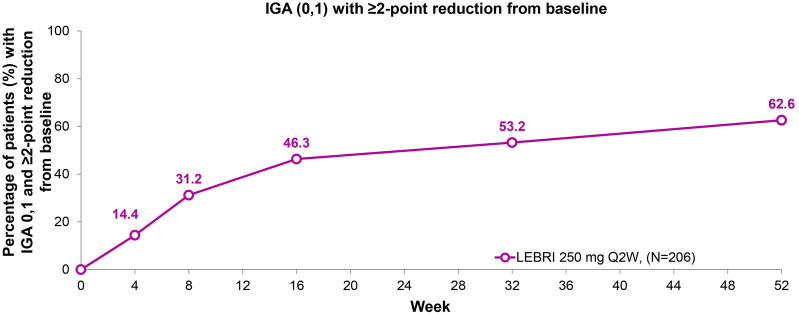

At Week 52, 62.6% of patients (n = 129) achieved an IGA score of 0 or 1 with ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline (Fig. 3). The response increased steadily at each time point, with 14.4% of patients achieving IGA (0,1) at the first study measurement at Week 4, 46.3% achieving IGA (0,1) at Week 16, and increasing to 62.6% at Week 52.

Fig. 3.

Time course response for IGA (0,1) with ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline. Percentage of patients (%) with IGA 0,1 and ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline through 52 weeks. A total of 62.6% of patients (N = 129) achieved IGA 0 or 1 with ≥ 2-point reduction from baseline at Week 52. Missing data due to lack of efficacy were imputed with non-responder imputation. Other missing data were imputed with multiple imputation. Abbreviations: IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, LEBRI lebrikizumab, Q2W every 2 weeks

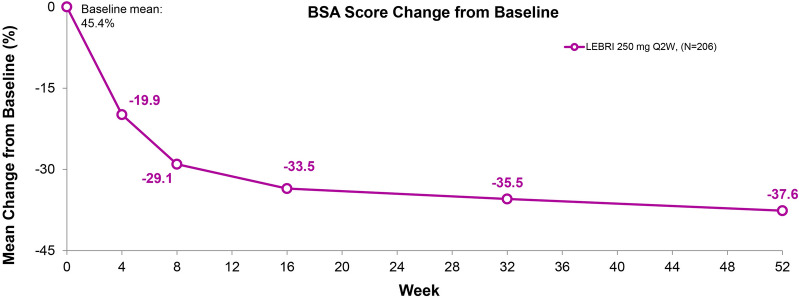

The mean BSA score at baseline was 45.4%, decreasing to 8.4% by Week 52 (Fig. 4). This response was observed by the first study measurement at Week 4 (− 19.9%), − 33.5% by Week 16, and improved further by Week 52 (− 37.6%).

Fig. 4.

Time course response for BSA mean change from baseline. Mean change from baseline in BSA score. Data presented as observed value by visit. Abbreviations: BSA Body Surface Area, LEBRI lebrikizumab, Q2W every 2 weeks

A total of 56 patients (27.2%) used at least one rescue therapy (Table S1). Most of the patients who used rescue therapy used TCS (26.2%), including both low- to moderate-potency (18.4%) and high-potency (10.2%) TCS. TCIs were used by 6.3% of patients, while a total of five (2.4%) patients used systemic corticosteroids. Of these, only one patient used systemic corticosteroids to treat AD; this patient was terminated early from the study as per protocol requirements. The only rescue immunosuppressant used in one patient was cyclosporine for allergic conjunctivitis, resulting in study termination as per protocol requirements.

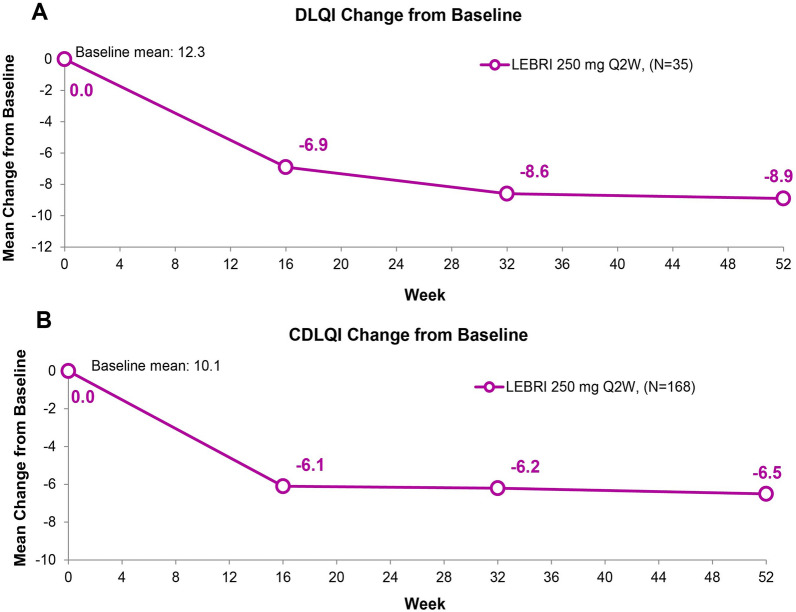

A total of 35 patients completed the DLQI questionnaire and 168 patients completed the CDLQI questionnaire. The mean change in DLQI score from the baseline score of 12.3 was consistent at Weeks 16 (− 6.9), 32 (− 8.6), and 52 (− 8.9) (Fig. 5A). A total of 13 patients (36.9%) with baseline DLQI score > 1 reported a DLQI score of 0 or 1 at Week 52. The mean change in CDLQI score from a baseline score of 10.1 was consistent at Weeks 16 (− 6.1), 32 (− 6.2), and 52 (− 6.5) (Fig. 5B). A total of 61 patients (37.2%) with baseline CDLQI score > 1 reported a CDLQI score of 0 or 1 at Week 52.

Fig. 5.

Mean change from baseline in DLQI (A) and CDLQI (B) scores. Missing data due to lack of efficacy were imputed with non-responder imputation. Other missing data were imputed with multiple imputation. Abbreviations: CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, DLQI Dermatology Life Quality Index, LEBRI lebrikizumab, Q2W every 2 weeks

Mean reductions from baseline in the PROMIS Anxiety and PROMIS Depression scores were reported at all measured time points (Fig. 6). The mean change in PROMIS Anxiety score from the baseline score of 51.5 was consistent between Weeks 16 (− 6.2), 32 (− 6.8), and 52 (− 6.3). The mean change in PROMIS Depression score from the baseline score of 49.3 was consistent at Weeks 16 (− 3.1), 32 (− 3.3), and 52 (− 3.4).

Fig. 6.

Mean change from baseline in PROMIS Anxiety (A) and PROMIS Depression (B) scores. Data presented as the as-observed analyses. Abbreviation: PROMIS patient-reported outcomes measurement information system

Discussion

In this Phase 3, 52-week open-label study of lebrikizumab in adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe AD, lebrikizumab 250 mg Q2W had a safety profile consistent with previous trials, including in patients from 12 years and older. Lebrikizumab demonstrated efficacy, with meaningful EASI and IGA responses at Week 16 that increased by Week 52, and improvements in quality of life. In total, 134 patients (65.0%) reported at least one TEAE. Most AEs were non-serious and mild or moderate in severity. Low frequencies of SAEs and AEs leading to permanent discontinuation of study treatment were reported. One death occurred during the study and was assessed by the investigator as unrelated to lebrikizumab. The safety profile of adolescents in ADore was consistent with the established safety profile of lebrikizumab.

Lebrikizumab 250 mg Q2W resulted in significant improvements in AD signs and symptoms. Clinically meaningful improvements in skin clearance, as assessed by IGA and EASI, were achieved as early as the first measurement at Week 4 with increasing efficacy over time. At Week 52, 62.6% of patients achieved IGA 0 or 1 and 81.9% of patients achieved EASI-75. The mean changes in DLQI/CDLQI, PROMIS Anxiety, and PROMIS Depression scores from baseline to Week 52 represent meaningful improvements in important patient-reported outcomes and were consistent across all measured time points. The efficacy results reported here are consistent with previous studies of lebrikizumab in moderate-to-severe AD.

Previously, lebrikizumab demonstrated significant clinical benefit in adolescent and adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD when used as monotherapy in two identically designed Phase 3 trials, ADvocate1 (NCT04146363) and ADvocate2 (NCT04178967). Primary and all key secondary endpoints were met at Weeks 4 and 16, as lebrikizumab 250 mg (vs. placebo) significantly improved skin clearance [as measured by IGA (0,1) and EASI-75], itch [Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)], interference of itch on sleep (Sleep-Loss Scale), and quality of life (DLQI) in both studies. Similarly, the ADhere study (NCT04250337) evaluated lebrikizumab treatment in combination with low to mid-potency TCS (vs. placebo + TCS) in both adolescent and adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD. Clinical benefit was evident in the ADhere study where significant improvements were observed in investigator-reported signs of AD as well as patient-reported outcomes of pruritus and quality of life in patients who received lebrikizumab and TCS compared with patients who received placebo and TCS. The results reported here from the ADore study are consistent with the safety and efficacy profile described in previous Phase 3 trials ADvocate 1 and 2 and ADhere [16, 17].

While the previous Phase 3 trials included adults and adolescents, the ADore study focused exclusively on lebrikizumab safety and efficacy in adolescent patients (≥ 12 to < 18 years old). Therefore, ADore provides valuable insight into lebrikizumab treatment in this population. The ADore study had a diverse patient population, including 11.7% Asian patients and 12.6% Black or African American patients. A notable strength of the ADore study was the 52-week duration, which demonstrated robust long-term efficacy of lebrikizumab in this population, with the majority of patients achieving IGA (0,1) (62.6%) and EASI-75 (81.9%) by Week 52. This study also demonstrated long-term safety and tolerability of lebrikizumab in adolescents consistent with results observed in previous trials and a positive benefit-risk profile.

One of the limitations of the ADore study is that it was a single-arm, open-label study, and therefore direct comparisons cannot be made to placebo or other treatment options reported in the literature. Also, study participants were limited to four countries in North America, Europe, and Australia, and clinical trial populations may not be directly translatable to general patient populations. Finally, patients remained on lebrikizumab Q2W for the duration of the study, and, in contrast to other lebrikizumab trials, Q4W maintenance dosing for 16-Week responders was not initiated. Considering the results observed in ADvocate 1 and ADvocate 2 studies, future studies should consider less frequent dosing for patients who achieved adequate clinical response at Week 16.

Conclusion

Lebrikizumab open-label, 250 mg Q2W had a safety profile in adolescents with moderate-to-severe AD, which was consistent with that observed in previous trials, with low frequencies of SAEs and AEs leading to treatment discontinuation. Lebrikizumab treatment also demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in investigator-assessed outcomes of skin clearance (IGA and EASI) over 52 weeks of treatment. Skin improvement was observed as early as the first measurement at Week 4, with increasing percentages of patients achieving improvement over the treatment period. Clinically meaningful improvements were also observed across multiple patient-reported outcomes. The positive benefit-risk profile demonstrated in this study provides evidence that targeting IL-13 with lebrikizumab is a meaningful approach for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD in the adolescent population.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Eli Lilly and Company and Almirall S.A. would like to thank the clinical trial participants and their caregivers, without whom this work would not be possible. Amber Reck Atwater, MD, of Eli Lilly and Company provided assistance with critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Funding

The ADore study was funded by Dermira, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly and Company. The journal’s Rapid Service Fee is funded by Eli Lilly and Company. Almirall, S.A. has licensed the rights to develop and commercialize lebrikizumab for the treatment of dermatology indications including atopic dermatitis in Europe. Eli Lilly and Company has exclusive rights for development and commercialization of lebrikizumab in the US and the rest of the world outside of Europe.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance and process support were provided by Niamh Wiley, PhD, of Eli Lilly and Company. Support for this assistance was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Author Contributions

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship, take responsibility for the integrity of the work, and have given their approval for this version to be published. Ana Pinto Correia, Chitra R. Natalie, Claudia Rodriguez Capriles, Evangeline Pierce, Sarah Reifeis, Renata Gontijo Lima, and Clara Armengol Tubau contributed to the study concept and design and drafted the manuscript. Sarah Reifeis conducted the statistical analyses of the data. Amy S. Paller, Carsten Flohr, Lawrence F. Eichenfield, Alan D. Irvine, Jamie Weisman, Jennifer Soung, Ana Pinto Correia, Chitra R. Natalie, Claudia Rodriguez Capriles, Evangeline Pierce, Sarah Reifeis, Renata Gontijo Lima, Clara Armengol Tubau, Vivian Laquer, and Stephan Weidinger contributed to acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript.

List of Investigators

The list of study investigators is included in supplementary material (Table S2).

Prior Publication

The results of this study were presented as a poster with oral presentation at the 2023 AAD Annual Meeting in New Orleans, US on 17 March 2023.

Disclosures

Amy S. Paller is a consultant with honorarium from AbbVie, Acrotech, Almirall, Amgen, Amryt, Arcutis, Arena, Azitra, BioCryst, BiomX, Boeringer Ingelheim, Botanix, Bridgebio, Castle Biosciences, Catawba, Eli Lilly and Company, Exicure, Gilead, Incyte, Janssen, Kamari, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, RAPT, Regeneron, Sanofi/Genzyme, Seanergy, UCB, and Union. She is an investigator for AbbVie, AnaptysBio, Dermavant, Eli Lilly and Company, Incyte, Janssen, Krystal, Regeneron, and UCB. She is on the Data Safety Monitoring Board for AbbVie, Abeona, Bausch, Bristol Myers Squibb, Galderma, Inmed, and Novan. Carsten Flohr is Chief Investigator of the UK National Institute for Health Research-funded TREAT (ISRCTN15837754) and SOFTER (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT03270566) trials as well as the UK-Irish Atopic eczema Systemic Therapy Register (A-STAR; ISRCTN11210918) and a Principal Investigator in the European Union (EU) Horizon 2020-funded BIOMAP Consortium (http://www.biomap-imi.eu/). He also leads the EU Horizon 2020 Joint Program Initiative-funded Trans-Foods consortium. His department has received funding from Sanofi Genzyme and Pfizer for skin microbiome work. Lawrence F. Eichenfield has been a consultant/advisory board member, speaker, and/or has served as an investigator for Amgen, AbbVie, Arcutis, Aslan, Bausch, Castle Biosciences, Dermavant, Eli Lilly and Company, Forte, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Seanergy, and UCB. Alan D. Irvine is a consultant/advisory board member/DSMB for AbbVie, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, Benevolent AI, LEO Pharma, and Arena. He has received research grants from AbbVie and Pfizer; is on the board of directors of the International Eczema Council; provides research support to Regeneron; and is in the speakers bureau for AbbVie, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, and Eli Lilly and Company. Jamie Weisman is an advisory board member for Sanofi, Regeneron, UCB, Eli Lilly and Company, and Novartis. She has received speaking fees from Eli Lilly and Company, Sanofi, Regeneron, and AbbVie and research grants from AbbVie, Aclaris, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dermavent, Glaxo Smith Kline, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sanofi, and UCB. Jennifer Soung has received speaker honoraria from AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Celgene, Dermira, Eli Lilly and Company, National Psoriasis Foundation, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, and Regeneron; consulting/advisory board honoraria from LEO Pharma, Lilly, and Novartis; and grant/research grant funding from AbbVie, Actavis, Actelion, Allergan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cassiopea, Dr Reddy’s, Galderma, Glaxo Smith Kline, Janssen, Kadmon, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Menlo, Novan, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologics, Pfizer, and UCB. Ana Pinto Correia was a full-time employee of Eli Lilly and Company at the time of the study and authoring of the manuscript. She is now a full-time employee of Glaxo Smith Kline; Chitra R. Natalie, Claudia Rodriguez Capriles, Evangeline Pierce, Sarah Reifeis, and Renata Gontijo Lima are full-time employees and stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. Clara Armengol Tubau is a full-time employee of Almirall. Vivian Laquer is consultant with honorarium from Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, and Cara. She is investigator for AbbVie, Amgen, Anaptys Bio, Arcutis, Argenx, Aslan, Biofrontera, Bristol Meyers Squibb, Castle, Dermavant, Eli Lilly and Company, Galderma, Incyte, Janssen Research & Development, Kiniksa, LEO Pharma, Moonlake, Novartis, Pfizer, Rapt Therapeutics, Sun Pharma, and UCB. Stephan Weidinger is a speaker, advisory board member, and/or investigator for AbbVie, Almirall, Galderma, Kymab, LEO Pharma, Eli Lilly and Company, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi. He has received research grants from Sanofi, Pfizer, LEO Pharma, and La Roche Posay.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was conducted in accordance with the protocol and consensus ethical principles derived from international guidelines including the Declaration of Helsinki and Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences International Ethical Guidelines, applicable ICH GCP guidelines, and applicable laws and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all patients before study procedures were initiated. The informed consent met the requirements of 21 CFR 50, local regulations, ICH guidelines on Good Clinical Practice, HIPAA requirements, and the IRB/IEC of the study center. The written consent of the parent or legal guardian, as well as the assent of the minor, was obtained.

Data Availability

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data are available for request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

References

- 1.Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, Simpson EL, Weidinger S, Mina-Osorio P, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(4):417–428. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Sher L, Gooderham MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):44–56. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brenninkmeijer EEA, Legierse CM, Sillevis Smitt JH, Last BF, Grootenhuis MA, Bos JD. The course of life of patients with childhood atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2009;26(1):14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2008.00745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunes M, Smidesang I, Holmen TL, Johnsen R. Atopic dermatitis in adolescent boys is associated with greater psychological morbidity compared with girls of the same age: the Young-HUNT study. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(2):283–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh SH, Bae BG, Park CO, Noh JY, Park IH, Wu WH, et al. Association of stress with symptoms of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90(6):582–588. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wollenberg A, Blauvelt A, Guttman-Yassky E, Worm M, Lynde C, Lacour JP, et al. Tralokinumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from two 52-week, randomized, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase III trials (ECZTRA 1 and ECZTRA 2) Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(3):437–449. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simpson EL, Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Chu C-Y, Hong HC-H, Katoh N, et al. Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in patients with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of follow-up data from the measure up 1 and measure up 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(4):404–413. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Thyssen JP, Gooderham M, Chan G, Feeney C, et al. Efficacy and safety of abrocitinib in patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(8):863–873. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreira S, Guttman-Yassky E, Torres T. Selective JAK1 inhibitors for the treatment of atopic dermatitis: focus on upadacitinib and abrocitinib. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(6):783–798. doi: 10.1007/s40257-020-00548-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thibodeaux Q, Smith MP, Ly K, Beck K, Liao W, Bhutani T. A review of dupilumab in the treatment of atopic diseases. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(9):2129–2139. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2019.1582403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stölzl D, Weidinger S, Drerup K. A new era has begun: treatment of atopic dermatitis with biologics. Allergologie Select. 2021;5:265. doi: 10.5414/ALX02259E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bieber T. Interleukin-13: targeting an underestimated cytokine in atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2020;75(1):54–62. doi: 10.1111/all.13954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okragly A, Ryuzoji A, Daniels M, Patel C, Benschop R, editors. Comparison of the affinity and in vitro activity of lebrikizumab, tralokinumab, and cendakimab2021 2021: WILEY 111 RIVER ST, HOBOKEN 07030-5774, NJ USA.

- 14.Szegedi K, Lutter R, Bos JD, Luiten RM, Kezic S, Middelkamp-Hup MA. Cytokine profiles in interstitial fluid from chronic atopic dermatitis skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29(11):2136–2144. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ungar B, Garcet S, Gonzalez J, Dhingra N, da Rosa JC, Shemer A, et al. An integrated model of atopic dermatitis biomarkers highlights the systemic nature of the disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137(3):603–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverberg JI, Guttman-Yassky E, Thaçi D, Irvine AD, Stein Gold L, Blauvelt A, et al. Two phase 3 trials of lebrikizumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2023 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson EL, Gooderham M, Wollenberg A, Weidinger S, Armstrong A, Soung J, et al. Efficacy and safety of lebrikizumab in combination with topical corticosteroids in adolescents and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized clinical trial (ADhere) JAMA Dermatol. 2023 doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.5534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, Feldman SR, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: se ction 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):338–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sampson HA, Muñoz-Furlong A, Campbell RL, Adkinson NF, Jr, Bock SA, Branum A, et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: summary report—Second National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease/Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Network symposium. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;117(2):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.12.1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winthrop KL, Novosad SA, Baddley JW, Calabrese L, Chiller T, Polgreen P, et al. Opportunistic infections and biologic therapies in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: consensus recommendations for infection reporting during clinical trials and postmarketing surveillance. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(12):2107–2116. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data are available for request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.