Abstract

Objective

Schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) share common clinical manifestations, genetic vulnerability, and environmental risk factors. We aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the comorbid prevalence of PTSD among schizophrenia-spectrum disorders.

Methods

We performed a meta-analysis to identify possible contributing factors to the heterogeneity among these studies. We systematically searched electronic databases with no restrictions on language of articles.

Results

We extracted 24 samples (18 for current prevalence and 6 for lifetime prevalence) from 22 studies and used a random effects model to estimate the pooled prevalence of PTSD among schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. The current and life prevalence of comorbid PTSD was 10.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]=6.3%–17.3%) and 13.0% (95% CI=5.3%–28.6%), respectively. Studies assessing psychotic experiences/involuntary admission reported the highest prevalence of comorbid PTSD (57.1%, 95% CI=43.6%–59.7%), whereas those assessing various anxiety disorders reported the lowest prevalence (1.1%, 95% CI=1.0%–5.5%). Heterogeneities of the subgroup analysis by similar objectives were largely homogeneous (I2=7.1–34.1). In the qualitative assessment, only two studies (9.1%) were evaluated as having a low risk of bias.

Conclusion

Our results showed that a careful approach with particular attention to assessing PTSD is essential to reliably estimate the prevalence of PTSD comorbid with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. The reason for the wide discrepancy in the prevalence of comorbid PTSD among the four groups of studies should be addressed in future research.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Meta-analysis, Systematic review, Prevalence

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a mental disorder characterized by positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms and often marked by chronic deterioration [1]. Like most other mental disorders, schizophrenia occurs as a result of gene-environment interactions [2-4]. Although a genetic predisposition is considered to play a substantial role in the onset and prognosis of schizophrenia [5], early-life adversity, such as traumatic experiences, influences the ultimate expression of the genetic factors [6,7].

Indeed, patients with schizophrenia commonly report having experienced traumatic events. Previous research indicates that approximately 40% to 80% of patients report a history of traumatic childhood experiences [8]. Traumatic experiences are associated with severe positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms in patients with schizophrenia [8-10], along with an absence of insight into their disease [11]. Patients also experience increased suicidal risk [12], impaired sensory gating [13], and disturbances in brain activity [14]. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and schizophrenia also share genetic predispositions; schizophrenia has a small but significantly overlapping polygenetic score with PTSD [15].

However, the relationship between schizophrenia and PTSD may be bidirectional. Prior research has suggested that psychosis, such as that caused by schizophrenia, can result in the onset of PTSD [16,17]. Indeed, psychotic symptoms such as auditory hallucinations with commanding voices could threaten patients who experience them [18,19]. When people first experience psychotic symptoms, they perceive that they are losing control over themselves, and that they are “crazy” and may be forced to be hospitalized involuntarily [18].

Given the possible bidirectional association of traumatic experiences and schizophrenia, it is likely that co-occurring PTSD is common in schizophrenia. As comorbid psychiatric disorders contribute to a poor prognosis of the illness for patients with schizophrenia [20], evaluating the prevalence of comorbid PTSD in schizophrenia is an important priority.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses conducted to date have not been able to accurately identify the prevalence of PTSD and its correlates in patients with schizophrenia. A meta-analysis first reported that the pooled prevalence of comorbid PTSD in schizophrenia was 12.4% (95% confidence interval [CI]=4.0%–20.8%) [21]. However, there was significant heterogeneity (χ2=294.1, p<0.001) among the included individual studies. As PTSD was not the primary focus of that meta-analysis, possible contributing factors for the heterogeneity were not reported. Two recent systematic reviews have focused on the prevalence of PTSD in schizophrenia [22,23]; however, several aspects of these reviews limit our ability to draw definitive conclusions. For instance, the two systematic reviews included studies that used only self-report instruments for diagnosing PTSD. In addition, there were no considerations for recruitment methods (e.g., consecutive, randomized) and the primary objective of the studies (e.g., measuring the prevalence of various anxiety disorders, specifically focused on PTSD).

In this meta-analysis, we aimed to investigate: 1) the pooled prevalence of comorbid PTSD in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders and 2) potential demographic and clinical moderators that influence the prevalence of PTSD. Given the substantial heterogeneity of the previous studies [21], we hypothesized that the pooled prevalence of comorbid PTSD in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders would depend on the demographic and clinical moderators.

METHODS

We conducted a meta-analysis and systematic review according to both the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines [24] and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [25].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included observational, cross-sectional, and cohort studies that measured the prevalence of PTSD among patients with schizophrenia. As schizophrenia and PTSD share essential symptoms such as hallucinations, anxiety, and intense fear, distinguishing these disorders requires a cautious approach [26]. Hence, we rigorously set the inclusion and exclusion criteria. First, the proportion of the sample with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophreniform disorder) was above 70%. When possible, the subpopulation of participants with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder was extracted and used for meta-analysis. Second, all participants were 18 years old or above. Third, only studies that used validated diagnostic and clinical interviewing instruments were included. We excluded studies that assessed participants without validated interviewer-rated diagnostic tools for PTSD. We also excluded studies that included patients at risk for PTSD (e.g., veterans, patients with comorbid substance use disorder).

Literature search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search of electronic databases (i.e., MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, and PsycINFO).

We set the search period to retrieve articles published before February 28, 2022. The search strategy was “posttraumatic stress disorder AND schizophrenia.” There were no language restrictions. We selectively searched the literature cited in the identified articles, along with systematic reviews and relevant news articles.

Study selection

We uploaded the final set of article to Covidence (www.covidence.org), an Internet-based program that enables a systematic selection of literature and facilitates independent reviews.

Two authors, KSN and AS, independently screened the titles and abstracts of the literature. KSN and AS obtained full texts for all studies that appeared to be eligible according to the predetermined criteria mentioned above. Potentially eligible studies were also assessed. When there were discrepancies between the two authors, a third author (SEC) resolved any disagreements about the relevance of the literature. If the information contained within a study was insufficient, or there was some uncertainty, one author (SEC) contacted the corresponding author of the study for clarification. If duplicate data were suspected, the study with the larger sample size was selected.

Data extraction

We extracted the number of patients with PTSD comorbid with schizophrenia in each study. If only the percentage of study participants with PTSD was available, we calculated the number of patients with PTSD by multiplying the total sample size by the percentage given. We separately estimated the lifetime and current prevalence of PTSD.

Risk of bias of individual studies

We assessed the risk of bias using instruments developed for the systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies [27].

Data synthesis

We estimated the prevalence of PTSD comorbid with schizophrenia by using an odds ratio with a 95% CI. We used a random effects model to estimate the pooled prevalence. We conducted a test for heterogeneity by using the Q-statistic and I2. Generally, an I2 of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, 25% represents low, 50% moderate, and 75% high heterogeneity [28]. In this study, an I2 of ≥50% was considered heterogeneous.

We conducted a subgroup analysis to identify factors contributing to heterogeneity. We conducted a meta-regression to identify the contributing factors for the results of the meta-analysis. Subgroup analysis and meta-regression were conducted on the primary objective, interviewing instruments, diagnostic criteria, and recruitment methods. All meta-analysis processes were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA).

Publication bias

Publication bias was visually inspected through a funnel plot. We also statistically estimated the degree of publication bias using Egger’s method [29].

Ethical considerations

The secondary data was collected from databases following clear systemic review guidelines. No personal information was collected and all data was stored electronically in accordance with the Gil Medical Center’s data protection policy. All research was conducted in accordance with Gil Medical Center’s Research Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

Literature search and selection

Figure 1 is a PRISMA diagram showing the process from literature identification to inclusion. Thirty studies underwent a full-text review. One study was excluded because the proportion of patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders was less than 70% [30]. Two were excluded because they did not use a structured clinical interview for diagnosing PTSD [31,32]. One was excluded because it included patients under 18 years of age [33]. Two studies were excluded because they only measured non-affective psychotic disorder [34,35]. One study was excluded because a validated structured interview tool was not used for diagnosing psychiatric disorders [36]. One study was excluded because only self-report instruments for diagnosing PTSD were used [37]. Ultimately, 22 studies were included in the meta-analysis and systematic review.

Figure 1.

Flow doagram of study selection process by PRISMA.

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Out of 22 studies, 18 studies measured current prevalence and six studies measured lifetime prevalence. Two studies measured both current and lifetime prevalence. Most studies focused on the prevalence of PTSD (n=11), followed by various anxiety disorders (n=5), various psychiatric disorders (n=4), and psychotic experiences/involuntary admission (n=2). Approximately half of the studies (n=12) consecutively recruited participants, whereas half of the studies (n=10) did not mention the recruitment methods. Most studies (n=16) diagnosed PTSD according to DSM-IV criteria [58].

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

| Study | Country | Objective | Recruitment | Total N | PTSD N | Interview | Diagnosis | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braga et al. [38] (2005) | Brazil | Various anxiety disorders | Consecutive | 53 | 2 | SCID | DSM-IV | Lifetime |

| Ciapparelli et al. [39] (2007) | Italy | Various anxiety disorders | N/A | 98 | 0 | SCID | DSM-IV | Current |

| DeTore et al. [45] (2021) | United States | PTSD | N/A | 404 | 20 | SCID | DSM-IV | Lifetime |

| Halász et al. [46] (2013) | Hungary | PTSD | N/A | 125 | 21 | SCID | DSM-IV | Current |

| Karatzias et al. [42] (2007) | United Kingdom | Various psychiatric disorders | Consecutive | 136 | 1 | SCID | DSM-IV | Current |

| Kiran and Chaudhury [47] (2016) | India | Various anxiety disorders | Consecutive | 93 | 1 | MINI | ICD-10 | Current |

| Neria et al. [48] (2002) | United States | PTSD | N/A | 170 | 17 | SCID | DSM-III-R | Lifetime |

| Newman et al. [49] (2010) | United States | PTSD | Consecutive | 52 | 22 | SCID | DSM-IV | Lifetime |

| 9 | Current | |||||||

| Pallanti et al. [50] (2004) | Italy | Various anxiety disorders | Consecutive | 80 | 1 | SCID | DSM-IV | Current |

| Peleikis et al. [51] (2013) | Norway | PTSD | Consecutive | 292 | 21 | SCID | DSM-IV | Lifetime |

| Priebe et al. [16] (1998) | Germany | Involuntary admission | N/A | 105 | 54 | PTSD-I | DSM-III-R | Current |

| Resnick et al. [52] (2003) | United States | PTSD | N/A | 47 | 6 | CAPS | DSM-IV | Current |

| Sarkar et al. [53] (2005) | United Kingdom | PTSD | N/A | 55 | 22 | PSS-I | DSM-IV | Lifetime |

| 15 | Current | |||||||

| Schäfer et al. [54] (2015) | Germany | PTSD | Consecutive | 121 | 14 | SCID | DSM-IV | Current |

| Seedat et al. [41] (2007) | South Africa | Various psychiatric disorders | Consecutive | 70 | 3 | MINI | DSM-IV | Current |

| Shaw et al. [17] (2002) | Australia | Psychotic experiences | Consecutive | 42 | 22 | CAPS | DSM-III-R | Current |

| Sim et al. [44] (2006) | Singapore | Various psychiatric disorders | Consecutive | 142 | 0 | SCID | DSM-IV | Current |

| Sin et al. [57] (2010) | Singapore | PTSD | N/A | 45 | 7 | CAPS | DSM-IV-TR | Current |

| Steel et al. [55] (2011) | United Kingdom | PTSD | N/A | 165 | 30 | CAPS | DSM-IV | Current |

| Strakowski et al. [40] (1993) | United States | Various psychiatric disorders | Consecutive | 10 | 0 | SCID | DSM-III-R | Current |

| Tibbo et al. [43] (2003) | Canada | Various anxiety disorders | N/A | 30 | 0 | MINI | DSM-IV | Current |

| Vogel et al. [56] (2009) | Germany | PTSD | Consecutive | 74 | 11 | SCID | DSM-III-R | Current |

PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; N, number; N/A, not available; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision; CAPS, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; PTSD-I, PTSD Interview; PSS-I, PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview

Qualitative assessment

Table 2 presents the qualitative scores of the studies. In the summary item on the overall risk of study bias, only two studies (9.1%) were evaluated as having a low risk of bias, seven (31.8%) were moderate, and 13 (59.1%) were assessed as high risk. Except for one study, Item 10 was largely met (95.4%). Eighteen studies (81.8%) evaluated the study instrument that measured the parameter of interest as valid and reliable (Item 7), and 16 (72.7%) were evaluated as using an acceptable case definition (Item 6). However, only one study included a target population that was a close representation of the national population (Item 1). In addition, only one study reported a response rate (Item 4).

Table 2.

Risk of bias of included studies

| Study | 1. Was the study’s target population a close representation of the national population in relation to relevant variables? | 2. Was the sampling frame a true or close representation of the target population? | 3. Was some form of random selection used to select the sample, OR was a census | 4. Was the likelihood of nonresponse bias minimal? | 5. Were data collected directly from the subjects (as opposed to a proxy)? | 6. Was an acceptable case definition used in the study? | 7. Was the study instrument that measured the parameter of interest shown to have validity and reliability? | 8. Was the same mode of data collection used for all | 9. Was the length of the shortest prevalence period for the parameter of interest appropriate? | 10. Were the numerator(s) and denominator(s) for the parameter of interest | 11. Summary item on the overall risk of study bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braga et al. [38] (2005) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | High |

| Ciapparelli et al. [39] (2007) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| DeTore et al. [45] (2021) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Low |

| Halász et al. [46] (2013) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | High |

| Karatzias et al. [42] (2007) | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | High |

| Kiran and Chaudhury [47] (2016) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | High |

| Neria et al. [48] (2002) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | High |

| Newman et al. [49] (2010) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | High |

| Pallanti et al. [50] (2004) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | High |

| Peleikis et al. [51] (2013) | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Moderate |

| Priebe et al. [16] (1998) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Resnick et al. [52] (2003) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | High |

| Sarkar et al. [53] (2005) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | High |

| Schäfer et al. [54] (2015) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Seedat et al. [41] (2007) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | High |

| Shaw et al. [17] (2002) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Sim et al. [44] (2006) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Sin et al. [57] (2010) | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Steel et al. [55] (2011) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Moderate |

| Strakowski et al. [40] (1993) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Tibbo et al. [43] (2003) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | High |

| Vogel et al. [56] (2009) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Low |

Meta-analysis

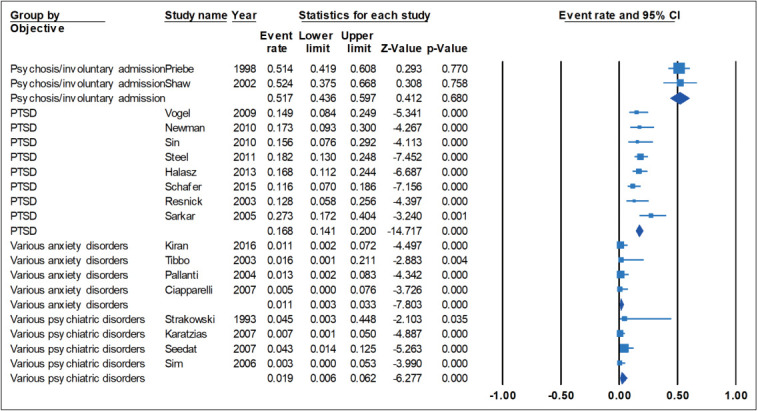

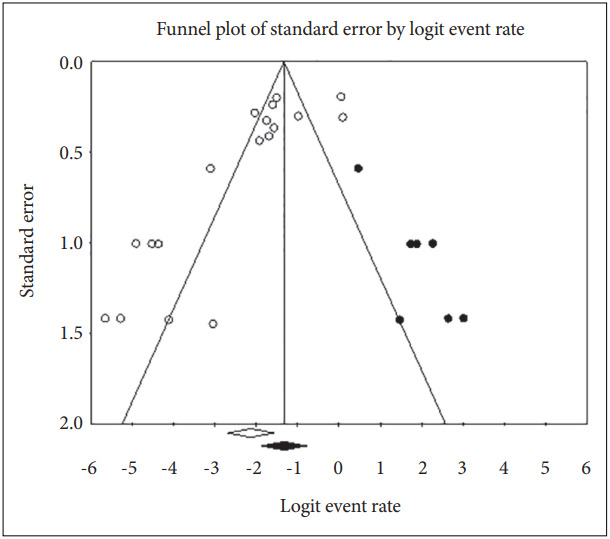

The current prevalence of PTSD comorbid with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder was 10.6% (95% CI=6.3%–17.3%) (Figure 2). The heterogeneity was substantially high (Q=148.9, I2=88.6). The funnel plot of standard error by logit event rate showed that there were substantial small study effects, which means that the results from the small sample size studies unduly influenced the pooled prevalence rate (Figure 3). The funnel plot shows that seven studies were needed to adjust for publication bias.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the prevalence of PTSD among patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder.

Figure 3.

Publication bias assessment for the prevalence of PTSD among patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. The white circles represent the actual studies. The black circles represent the imputed studies, which were assumed to have been present if the funnel plot had been symmetrical. The vertical line indicates the pooled log of the relative risk after adjustment for publication bias.

Six studies examined the lifetime prevalence of PTSD. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD was 13.0% (95% CI=5.3%–28.6%), with substantial heterogeneity (Q=96.0, I2=94.8).

Subgroup analysis and meta-regression

The subgroup analysis for current prevalence of PTSD is presented in Table 3. Unlike the results for the total sample, subgroup analysis shows that studies grouped by similar objectives were largely homogeneous. The I2 statistics were zero in the groups of studies of psychotic experiences/involuntary admission and various anxiety disorder groups. The groups of studies of PTSD (I2=7.1) and various psychiatric disorders (I2=34.1) also had low heterogeneity. The current prevalence of PTSD was widely varied across the four subgroups. Subgroup of psychotic experiences/involuntary admission reported the highest prevalence (57.1%, 95% CI=43.6%–59.7%), which was followed by PTSD (16.9%, 95% CI=14.2%–19.9%), various psychiatric disorders (2.3%, 95% CI=1.0%–5.5%), and various anxiety disorders (1.1%, 95% CI=0.3%–3.3%).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the prevalence of current PTSD among patients with schizophrenia

| Variables | N | Mean prevalence (%) | 95% CI (%) | p | Q | I2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | |||||||

| Psychosis/involuntary admission | 2 | 51.7 | 43.6–59.7 | 0.917 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| PTSD | 8 | 16.9 | 14.2–19.9 | 0.375 | 7.5 | 7.1 | |

| Various anxiety disorders | 4 | 1.1 | 0.3–3.3 | 0.941 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |

| Various psychiatric disorders | 4 | 2.3 | 1.0–5.5 | 0.207 | 4.5 | 34.1 | |

| Recruitment | |||||||

| Consecutive | 10 | 6.1 | 2.4–14.4 | <0.001 | 74.7 | 87.9 | |

| Not reported | 8 | 17.2 | 9.3–29.7 | <0.001 | 62.3 | 88.8 | |

| Diagnostic criteria | |||||||

| DSM-III-R | 4 | 31.8 | 13.8–57.5 | <0.001 | 28.1 | 89.3 | |

| DSM-IV | 13 | 9.6 | 6.1–14.9 | <0.001 | 48.2 | 75.1 | |

| ICD-10 | 1 | 1.1 | 0.2–7.2 | >0.999 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Diagnostic interview | |||||||

| CAPS | 4 | 22.6 | 10.6–41.6 | <0.001 | 24.0 | 87.5 | |

| MINI | 3 | 2.8 | 1.1–6.9 | 0.437 | 1.6 | 0.0 | |

| SCID | 9 | 7.0 | 3.6–13.0 | <0.001 | 31.1 | 74.3 | |

| PSS-I | 1 | 27.3 | 17.2–40.4 | >0.999 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| PTSD-I | 1 | 51.4 | 41.9–60.8 | >0.999 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

N, number; CI, confidence interval; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; CAPS, Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; MINI, Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; SCID, Structured Clinical Interview for DSM Disorders; PSS-I, PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview; PTSD-I, PTSD Interview

The meta-regression model, which evaluated the impact of the objective of the study (psychotic experiences/involuntary admission, various anxiety disorders, various psychiatric disorders, and PTSD) showed an R2 of 1.0, which means that these variables explain 100% of the total variance in true effects. Recruitment type (R2=0.0), clinical interview conducted (R2=0.42), and diagnostic criteria used (R2=0.45) did not adequately explain the total variance.

Due to the small number of individual studies, subgroup analysis and meta-regression were not conducted for lifetime prevalence of PTSD.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the comorbid prevalence of PTSD among schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. The pooled prevalence of current comorbid PTSD, 10.6% (95% CI=6.3%–17.3%), is slightly lower than that estimated 10 years ago, 12.4% (95% CI=4.5%–20.8%). In contrast with the previous meta-analysis, which estimated the combined lifetime and current prevalence of PTSD [21], we estimated it separately since lifetime prevalence is usually higher than current prevalence. There were no meaningful differences between the two types of prevalence in both previous research and the current results. We suggest that the imbalanced proportion of studies targeting various anxiety or psychiatric disorders caused the non-discrepant results between lifetime and current prevalence. Only one out of eight (12.5%) studies of various anxiety or psychiatric disorders were included in the lifetime prevalence group, but seven out of eight (87.5%) studies of various anxiety or psychiatric disorders were included in the current prevalence group. Hence, the lifetime prevalence of PTSD may have been diluted by studies targeting various psychiatric disorders.

Heterogeneity among studies was high in previous research [21] and in this meta-analysis. Whereas the previous meta-analysis did not report which factors contributed to such high heterogeneity [21], we aimed to identify these factors via subgroup analysis and meta-regression. Our results showed that the prevalence of comorbid PTSD was mostly dependent on the objective of the studies. Studies that estimated the prevalence of various anxiety disorders and psychiatric disorders beyond solely PTSD showed the lowest prevalence (1.1%, 95% CI=0.3%–3.3%), whereas studies that investigated the possible role of psychotic experiences and involuntary admission had the highest prevalence, 51.7% (95% CI=43.6%–59.7%) [16,17]. Studies that focused solely on the prevalence of PTSD reported a prevalence of 16.9% (95% CI=14.2%–19.9%), which is similar to the pooled prevalence rate in the total sample. In the subgroup analysis based on the primary objective of the individual studies, heterogeneity was not revealed to be more prominent. This result means that the prevalence of comorbid PTSD in schizophrenia-spectrum disorder is highly dependent on the primary focus of the individual studies.

There are several reasons for the apparent discrepancy in the prevalence of comorbid PTSD among the four groups of studies. The extremely low prevalence reported among studies of various psychiatric disorders and various anxiety disorders may have arisen from a lack of specific focus on PTSD. Indeed, no studies paid particular attention to the etiology or correlates of the prevalence of PTSD. Because PTSD and schizophrenia often have common etiological factors (e.g., early-life adversity) and clinical symptoms (e.g., hallucinations) [26], the diagnosis of PTSD comorbid with schizophrenia is not merely adding one disease to another. Careful attention is needed to detect PTSD in patients with a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder. Such efforts usually include the use of additional diagnostic tools such as the Impact of Event Scale-Revised [59] and the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire [60] for traumatic experiences and PTSD. However, no studies to date have used any additional instruments specifically designed to assess PTSD [38-44]. Without sufficient information on traumatic experiences and PTSD symptoms, those studies appeared to conclude that there was no comorbid PTSD.

On the other hand, two studies reported a relatively high prevalence of comorbid PTSD (51.7%, 95% CI=43.6%–59.7%) [16,17]. These studies both assessed external factors impacting the prevalence of PTSD, such as traumatic experiences or psychiatric admission. However, this is the only similarity between the two studies. Priebe et al. [16] and Shaw et al. [17] used PTSD-specific diagnostic instruments such as the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale [61] and PTSD interview [62], respectively. Other factors, such as the recruitment method, diagnostic criteria, and diagnostic tool, could not explain why only these two studies reported a substantial prevalence of comorbid PTSD. However, as shown in one study [16], the severity of PTSD correlated with the severity of psychopathology. As Priebe et al. [16] described, it might be challenging to distinguish symptoms of PTSD from those of schizophrenia. Although psychotic experiences and involuntary admission to a psychiatric ward could induce intense anxiety and fear, which consequently may have led to the onset of PTSD, an excessively high prevalence than other types of traumatic experiences could not be easily understood. Subsequent studies with similar objectives and design should be conducted to confirm the high prevalence of PTSD reported in these two studies.

Unlike previous systematic reviews [22,23], we applied rigorous criteria to exclude risk groups for PTSD, such as those with substance use disorder [63] and veterans [64]. As these populations are prone to PTSD, estimating the prevalence of PTSD among those groups may have led to an overestimation of PTSD in those reviews.

This study has several limitations which should be noted. First, variables related to traumatic events of PTSD, such as type and onset of trauma, were not systematically collected in most of studies. Second, subgroup analysis and meta-regression for the lifetime prevalence of comorbid PTSD could not be measured due to small numbers of individual studies. Third, most of the individual studies were conducted in the Western countries such as the United States and Europe, whereas only three studies were conducted in the Eastern countries (one in India and two in Singapore). Given the cross-cultural sensitivity to the traumatic response [65], more studies from the East Asian countries are needed.

Our meta-analysis has several implications of note. First, studies should primarily focus on PTSD rather than merely including PTSD as one of the various anxiety disorders. Second, studies should obtain supplemental information about PTSD symptoms and history beyond the use of a structured diagnostic interview. For example, a lifetime history of traumatic events should be collected and PTSD-specific rating instruments should be used. Third, transparent reporting of recruitment of participants is recommended for future studies. Only half of all studies (12 out of 24) consecutively recruited participants, whereas others did not mention how they recruited participants.

In conclusion, we showed that the prevalence of PTSD among patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders is highly dependent on the objective of the studies. Thus, solely estimating the prevalence of PTSD in schizophrenia-spectrum disorders might lead to a biased conclusion. Before amalgamating the results of individual studies, it is necessary to categorize studies according to the appropriate criteria. Future studies are needed to accurately estimate the prevalence of PTSD among patients with schizophrenia.

Footnotes

Availability of Data and Material

The datasets generated or analyzed during the suty are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Anna Seong, Kyoung-Sae Na. Data curation: Anna Seong, Kyoung-Sae Na. Formal analysis: Kyoung-Sae Na. Investigation: all authors. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: Kyoung-Sae Na. Software: Kyoung-Sae Na. Supervision: Kyoung-Sae Na. Validation: Kyoung-Sae Na. Visualization: Kyoung-Sae Na. Writing—original draft: all authors. Writing—review & editing: all authors.

Funding Statement

None

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punzi G, Bharadwaj R, Ursini G. Neuroepigenetics of schizophrenia. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2018;158:195–226. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stilo SA, Murray RM. Non-genetic factors in schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:100. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1091-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lieslehto J, Kiviniemi VJ, Nordström T, Barnett JH, Murray GK, Jones PB, et al. Polygenic risk score for schizophrenia and face-processing network in young adulthood. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:835–845. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henriksen MG, Nordgaard J, Jansson LB. Genetics of schizophrenia: overview of methods, findings and limitations. Front Hum Neurosci. 2017;11:322. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2017.00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Husted JA, Ahmed R, Chow EW, Brzustowicz LM, Bassett AS. Early environmental exposures influence schizophrenia expression even in the presence of strong genetic predisposition. Schizophr Res. 2012;137:166–168. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BP. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468:203–212. doi: 10.1038/nature09563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacioglu Yildirim M, Yildirim EA, Kaser M, Guduk M, Fistikci N, Cinar O, et al. The relationship between adulthood traumatic experiences and psychotic symptoms in female patients with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55:1847–1854. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popovic D, Schmitt A, Kaurani L, Senner F, Papiol S, Malchow B, et al. Childhood trauma in schizophrenia: current findings and research perspectives. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:274. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dauvermann MR, Donohoe G. The role of childhood trauma in cognitive performance in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder - A systematic review. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2019;16:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2018.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pignon B, Lajnef M, Godin O, Geoffray MM, Rey R, Mallet J, et al. Relationship between childhood trauma and level of insight in schizophrenia: a path-analysis in the national FACE-SZ dataset. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohammadzadeh A, Azadi S, King S, Khosravani V, Sharifi Bastan F. Childhood trauma and the likelihood of increased suicidal risk in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2019;275:100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li XB, Bo QJ, Tian Q, Yang NB, Mao Z, Zheng W, et al. Impact of childhood trauma on sensory gating in patients with first-episode schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:258. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1807-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quidé Y, Ong XH, Mohnke S, Schnell K, Walter H, Carr VJ, et al. Childhood trauma-related alterations in brain function during a Theory-ofMind task in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2017;189:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumner JA, Duncan L, Ratanatharathorn A, Roberts AL, Koenen KC. PTSD has shared polygenic contributions with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in women. Psychol Med. 2016;46:669–671. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Priebe S, Bröker M, Gunkel S. Involuntary admission and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in schizophrenia patients. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39:220–224. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(98)90064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaw K, McFarlane AC, Bookless C, Air T. The aetiology of postpsychotic posttraumatic stress disorder following a psychotic episode. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15:39–47. doi: 10.1023/A:1014331211311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunkley JE, Bates GW, Findlay BM. Understanding the trauma of first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2015;9:211–220. doi: 10.1111/eip.12103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry K, Ford S, Jellicoe-Jones L, Haddock G. PTSD symptoms associated with the experiences of psychosis and hospitalisation: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:526–538. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckley PF, Miller BJ, Lehrer DS, Castle DJ. Psychiatric comorbidities and schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:383–402. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achim AM, Maziade M, Raymond E, Olivier D, Mérette C, Roy MA. How prevalent are anxiety disorders in schizophrenia? A meta-analysis and critical review on a significant association. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:811–821. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dallel S, Cancel A, Fakra E. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatry. 2018;8:1027–1037. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seow LSE, Ong C, Mahesh MV, Sagayadevan V, Shafie S, Chong SA, et al. A systematic review on comorbid post-traumatic stress disorder in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2016;176:441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.OConghaile A, DeLisi LE. Distinguishing schizophrenia from posttraumatic stress disorder with psychosis. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2015;28:249–255. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer H, Taiminen T, Vuori T, Aijälä A, Helenius H. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms related to psychosis and acute involuntary hospitalization in schizophrenic and delusional patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1999;187:343–352. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199906000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mueser KT, Goodman LB, Trumbetta SL, Rosenberg SD, Osher fC, Vidaver R, et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:493–499. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng LC, Petruzzi LJ, Greene MC, Mueser KT, Borba CP, Henderson DC. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and social and occupational functioning of people with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204:590–598. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strakowski SM, Keck PE, Jr, McElroy SL, Lonczak HS, West SA. Chronology of comorbid and principal syndromes in first-episode psychosis. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36:106–112. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(95)90104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessler RC, Birnbaum H, Demler O, Falloon IR, Gagnon E, Guyer M, et al. The prevalence and correlates of nonaffective psychosis in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendler KS, Gallagher TJ, Abelson JM, Kessler RC. Lifetime prevalence, demographic risk factors, and diagnostic validity of nonaffective psychosis as assessed in a US community sample. The national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:1022–1031. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830110060007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garvey M, Noyes R, Jr, Anderson D, Cook B. Examination of comorbid anxiety in psychiatric inpatients. Compr Psychiatry. 1991;32:277–282. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(91)90075-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogel M, Spitzer C, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, Grabe HJ. The role of trauma and PTSD-related symptoms for dissociation and psychopathological distress in inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 2006;39:236–242. doi: 10.1159/000093924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braga RJ, Mendlowicz MV, Marrocos RP, Figueira IL. Anxiety disorders in outpatients with schizophrenia: prevalence and impact on the subjective quality of life. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:409–414. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ciapparelli A, Paggini R, Marazziti D, Carmassi C, Bianchi M, Taponecco C, et al. Comorbidity with axis I anxiety disorders in remitted psychotic patients 1 year after hospitalization. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:913–919. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900015704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strakowski SM, Tohen M, Stoll AL, Faedda GL, Mayer PV, Kolbrener ML, et al. Comorbidity in psychosis at first hospitalization. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:752–757. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seedat S, Fritelli V, Oosthuizen P, Emsley RA, Stein DJ. Measuring anxiety in patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:320–324. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000253782.47140.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karatzias T, Gumley A, Power K, O’Grady M. Illness appraisals and self-esteem as correlates of anxiety and affective comorbid disorders in schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2007;48:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tibbo P, Swainson J, Chue P, LeMelledo JM. Prevalence and relationship to delusions and hallucinations of anxiety disorders in schizophrenia. Depress Anxiety. 2003;17:65–72. doi: 10.1002/da.10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sim K, Chua TH, Chan YH, Mahendran R, Chong SA. Psychiatric comorbidity in first episode schizophrenia: a 2 year, longitudinal outcome study. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeTore NR, Gottlieb JD, Mueser KT. Prevalence and correlates of PTSD in first episode psychosis: Findings from the RAISE-ETP study. Psychol Serv. 2021;18:147–153. doi: 10.1037/ser0000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halász I, Levy-Gigi E, Kelemen O, Benedek G, Kéri S. Neuropsychological functions and visual contrast sensitivity in schizophrenia: the potential impact of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Front Psychol. 2013;4:136. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiran C, Chaudhury S. Prevalence of comorbid anxiety disorders in schizophrenia. Ind Psychiatry J. 2016;25:35–40. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.196045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neria Y, Bromet EJ, Sievers S, Lavelle J, Fochtmann LJ. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in psychosis: findings from a first-admission cohort. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:246–251. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newman JM, Turnbull A, Berman BA, Rodrigues S, Serper MR. Impact of traumatic and violent victimization experiences in individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:708–714. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181f49bf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Hollander E. Social anxiety in outpatients with schizophrenia: a relevant cause of disability. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:53–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Peleikis DE, Varga M, Sundet K, Lorentzen S, Agartz I, Andreassen OA. Schizophrenia patients with and without post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have different mood symptom levels but same cognitive functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127:455–463. doi: 10.1111/acps.12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Resnick SG, Bond GR, Mueser KT. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in people with schizophrenia. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:415–423. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sarkar J, Mezey G, Cohen A, Singh SP Olumoroti O. Comorbidity of post traumatic stress disorder and paranoid schizophrenia: a comparison of offender and non-offender patients. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2005;16:660–670. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schäfer I, Eiroa-Orosa FJ, Schroeder T, Aderhold V. [Posttraumatic disorders in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders] Nervenarzt. 2015;86:818–825. doi: 10.1007/s00115-014-4237-x. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steel C, Haddock G, Tarrier N, Picken A, Barrowclough C. Auditory hallucinations and posttraumatic stress disorder within schizophrenia and substance abuse. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199:709–711. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318229d6e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vogel M, Schatz D, Spitzer C, Kuwert P, Moller B, Freyberger HJ, et al. A more proximal impact of dissociation than of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder on schneiderian symptoms in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50:128–134. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sin GL, Abdin E, Lee J, Poon LY, Verma S, Chong SA. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2010;4:299–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weiss DS, Marmar CR. In: Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. The impact of event scale: revised; pp. 399–411. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The Harvard trauma questionnaire. Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992;180:111–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, et al. The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Watson CG, Juba MP, Manifold V, Kucala T, Anderson PE. The PTSD interview: rationale, description, reliability, and concurrent validity of a DSM-III-based technique. J Clin Psychol. 1991;47:179–188. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199103)47:2<179::aid-jclp2270470202>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Picken A, Tarrier N. Trauma and comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder in individuals with schizophrenia and substance abuse. Compr Psychiatry. 2011;52:490–497. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Calhoun PS, Stechuchak KM, Strauss J, Bosworth HB, Marx CE, Butterfield MI. Interpersonal trauma, war zone exposure, and posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2007;91:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel AR, Hall BJ. Beyond the DSM-5 diagnoses: a cross-cultural approach to assessing trauma reactions. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ) 2021;19:197–203. doi: 10.1176/appi.focus.20200049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]