Abstract

Due to excess energy intake and a sedentary lifestyle, the prevalence of obesity is rising steadily and has emerged as a global public health problem. Adipose tissue undergoes structural remodeling and dysfunction in the obese state. Secreted proteins derived from the liver, also termed as hepatokines, exert multiple effects on adipose tissue remodeling and the development of obesity, and has drawn extensive attention for their therapeutic potential in the treatment of obesity and related diseases. Several novel hepatokines and their functions on systemic metabolism have been interrogated recently as well. The drug development programs targeting hepatokines also have shown inspiring benefits in obesity treatment. In this review, we outline how adipose tissue changes during obesity. Then, we summarize and critically analyze the novel findings on the effects of metabolic “beneficial” and metabolic “harmful” hepatokines to adipose tissue. We also discuss the in-depth molecular mechanism that hepatokines may mediate the liver-adipose tissue crosstalk, the novel technologies targeting hepatokines and their receptors in vivo to explore their functions, and the potential application of these interventions in clinical practice.

Keywords: FGF21, Hepatokine, Liver-adipose tissue crosstalk, Obesity, Therapeutic strategy

Abbreviations

- AAV

adeno-associated viruses

- ACVR1 and ACVR2

Activin A receptor type 1 and 2

- ANGPTL

Angiopoietin-like proteins

- ASO

antisense oligonucleotide

- BAT

brown adipose tissue

- BMPs

bone morphogenetic proteins

- CREB

cAMP responsive element binding protein

- FetA

Fetuin-A

- FFA

free fatty acids

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- FNDC4

fibronectin type III domain containing 4

- FST

Follistatin

- GalNAc

N-acetylgalactosamine

- GLUT1

glucose transporter-1

- GPNMB

glycoprotein nonmetastatic melanoma protein B

- GPR116

G-protein coupled receptor 116

- HFD

high-fat diet

- LPL

lipoprotein lipase

- LXR

liver X receptor

- MAFLD

metabolic associated fatty liver disease

- Manf

mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor

- ORM

orosomucoid

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TLR4

Toll-like receptor 4

- TSK

Tsukushi

- SREBP

sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- UCP1

uncoupling protein 1

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity has dramatically increased over the past few decades and has become a worldwide public health problem.1 Furthermore, obesity, especially visceral obesity, is strongly associated with metabolic syndromes, including type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease, and metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), therefore significantly decreasing life expectancy.1, 2, 3 In particular, excessive fat accumulation, especially unhealthy adipose tissue expansion, leads to local inflammation and insulin resistance, thereby triggering the metabolic disorders.4,5 Several secreted proteins are implicated in adipose development and function during the development of obesity through autocrine, paracrine, and endocrine mechanisms.6, 7, 8 However, there are still numerous secreted protein-mediated molecular connections between adipose tissue and obesity related metabolic disorders remaining to be unraveled.

Recently, liver-secreted proteins, known as hepatokines, have attracted great attention for their critical roles in the communication between the liver and other organs.9,10 The liver can sense alteration in energy status and secret hepatokines into circulation to regulate other organs’ functions,11, 12, 13 including adipose tissue. It has been demonstrated that hepatokines directly regulate adipose tissue expansion, inflammation, lipid metabolism, and the browning of white adipose tissue, thereby orchestrating systemic glucose and lipid homeostasis.14,15 Additionally, long-term pathologic conditions such as insulin-resistant states disrupt the expression and secretion profiles of hepatokines, which further aggravates the globe and adipose metabolic disorder.16 Lifestyle modification, such as diet restriction or exercise, may improve the production of hepatokines and ameliorate systemic and adipose metabolism.17, 18, 19, 20 Besides, there are several drugs targeting hepatokines that show benefits for obesity treatment, including weight loss, adipose tissue remodeling, reversing hepatic steatosis, and alleviating insulin resistance.21, 22, 23 Consequently, secreted proteins are a rich source of new therapeutics and drug targets. Furthermore, the identification and functional characterization of novel hepatokines may provide indispensable insights to novel therapeutic modalities for obesity and related metabolic disorders.24

This review includes: 1) the function of adipose tissue and dynamic change during obesity; 2) the molecular mechanism of metabolic beneficial and metabolic harmful hepatokines in liver-adipose cross-talk; 3) therapeutic strategies based on hepatokines.

Adipose tissue changes in obesity

First are the fundamental principles of the normal physiology of adipose tissue. Adipose tissue is a multifunctional organ functioning in systemic energy homeostasis.25 Classically, there are two major types of adipose tissue: white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT). Under physiological conditions, WAT is widely distributed under the skin or between visceral plots, for instance the perigonadal, mesenteric, and retroperitoneal fat pads.25 BAT is highly vascularized and innervated, and is located in interscapular, subscapular, axillary and periaortic regions in rodents and infants.25 Nevertheless, the BAT is regressed with age and is found to be in the supraclavicular and spinal regions in adult humans.26 The key role of WAT is to store excessive energy in the form of accumulated lipids.27 In contrast, BAT functions primarily in thermogenesis through its ample mitochondria which are induced by mitochondria biogenesis in response to external stimuli and is featured by high expression of thermogenic genes including uncoupling protein 1 (UCP-1) expression.28,29 Emerging evidence suggests that cold exposure provokes the formation of clusters of UCP-1 positive adipocytes with the brown-like phenotype within WAT.30, 31, 32 This process is termed as “browning” of WAT and is considered as a widely accepted intervention strategy to target obesity. Moreover, activation of BAT and WAT browning in humans contributes significantly to increased whole body energy expenditure, lowered body weight, and accelerated glucose disposal, which indicating pharmacological activation of BAT is a plausible therapeutic strategy against obesity and other related metabolic diseases.33

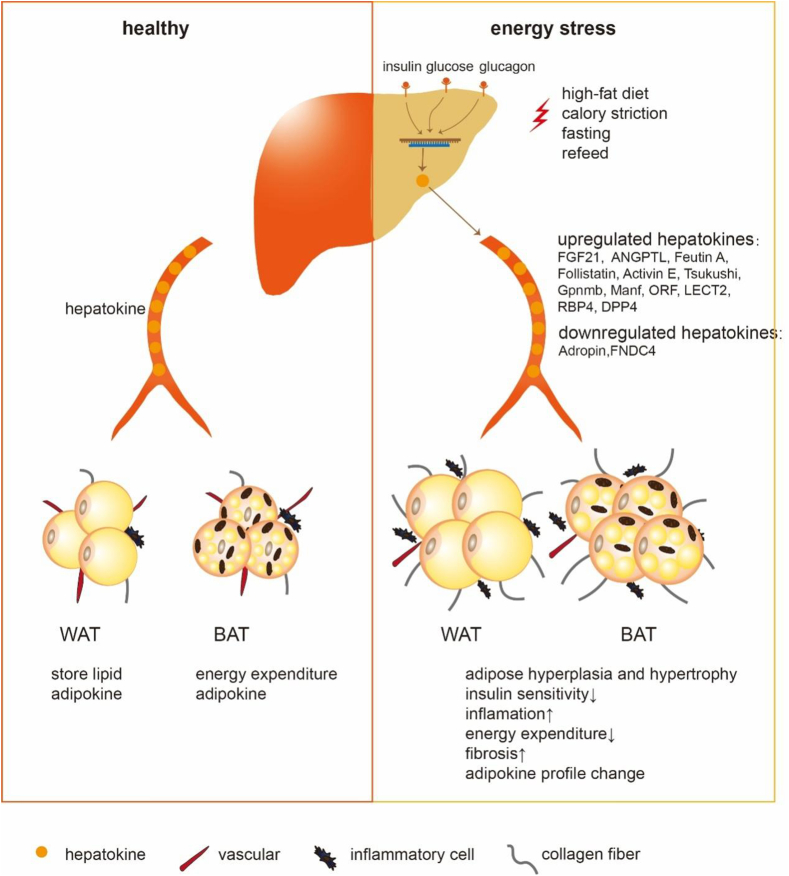

In the obese state, adipose tissue undergoes remodeling and dysfunction.34,35 To satisfy the need to store excess calories, adipose tissue expands through increasing adipocyte size (hypertrophy) and number (hyperplasia), accompanied by disproportionally limited angiogenesis and thereby ensuing hypoxia.35,36 As a result, hypoxia-induced 1α is activated, which in turn induces the fibrotic program.37,38 These alterations trigger uncontrolled inflammatory responses and subsequently evoke chronically systemic inflammation and decrease insulin sensitivity.39 Concurrently, adipose tissue remodeling contributes to impaired adipose tissue functions, including increased free fatty acids (FFA) fluxes, ectopic fat accumulation, insulin resistance, and unfavorable adipokines profiles.34 Besides, vascular insufficiency and hypoxia also drive BAT dysfunction, namely “whitening” of this tissue, resulting in impaired thermogenesis and inflammasome activation.40,41 Secreted proteins, such as hepatokines, can circulate to adipose tissue and play an important role in the (patho)physiologic remodeling of adipose tissue during the progression of obesity14,15 (Fig. 1). Pharmacological interventions targeting hepatokines can restore adipose tissue function and thus alleviate systemic metabolic disorder through promoting thermogenesis, regulating proliferation and adipogenesis, attenuating inflammation and fibrosis, suppressing excess FFA fluxes, and improving insulin sensitivity.42,43 Here we will focus on the regulation of hepatokines secretion, their role on adipose tissue, and their potential implication in clinical treatment.

Figure 1.

The metabolic effects of hepatokines on adipose tissue. During the healthy state, the liver can secret hepatokines to the circulation, then hepatokines exert roles in both white and brown adipose tissue (WAT and BAT) physiological function, such as energy storing and expenditure. During energy stress, such as high-fat diet, calorie restriction, fasting, and refeed, several modulators including insulin, glucose, and glucagon levels alter, thereby disrupt the expression and secretion of hepatokines. The dysregulated hepatokines then circulate to adipose tissue, resulting in adipocytes hyperplasia and hypertrophy, reducing insulin sensitivity, increasing inflammation, decreasing energy expenditure, promoting fibrosis, and altering adipokine profiles.

Hepatokines mediate the liver-adipose cross-talk

Metabolic beneficial hepatokines

FGF21

The fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) signal through FGF receptors (FGFRs) to regulate the early development of multiple organ systems and maintain the metabolic homeostasis, of which FGF21 is the most prominent hepatokine.44 The production of FGF21 is highly dependent on nutritional perturbation. Various nutritional stresses including starvation, high fat diet or ketogenic diet feeding, amino acid restriction, and alcoholic intemperance can induce the production of FGF21 in the liver.19,45 Mechanistically, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα) binds to the FGF21 promotor thereby directly upregulates FGF21 at transcription levels in response to fasting,11,46 while activation of another transcription factor, carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) increases the production of FGF21 in response to high concentrations of carbohydrate.47

FGF21 mediates multifaceted pharmacologically beneficial effects on the obesity and related diseases. Long-term FGF21 treatment reduced body fat mass, increased energy expenditure, and improved glucose and lipid homeostasis in high-fat diet (HFD) fed mice.48 Mechanistically, FGF21 binds to a cell surface receptor complex comprised of two proteins: an FGF receptor (FGFR) and a co-receptor b-Klotho (KLB), thereby activating FGFR signaling.45,49 In line with this, adipocyte-specific depletion of FGF1R or KLB abrogated the metabolic benefits of FGF21, suggesting adipocytes play an indispensable role in mediating the action of FGF21.50,51 Moreover, FGF21 treatment reduced adiposity via triggering the BAT activation and the browning of WAT.52 In detail, FGF21 induced the phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor, cAMP responsive element binding protein (CREB), and upregulated the transcription of Pgc1α and Ucp1 via FGF21-KLB/FGFR1c-pERK-pCREB-PGC1α-UCP1 pathway.52 Besides, FGF21 also can activate PGC1α in a post-translational manner by activating the AMPK-SIRT1-PGC1α pathway.53 Furthermore, FGF21 treatment improved insulin sensitivity and increased glucose uptake in adipose tissue, particularly in BAT, which was mediated by elevated phosphorylation of ERK, thereby enhancing the expression of glucose transporter-1 (GLUT1) in adipocytes.54,55 Besides, FGF21 overexpression or FGF21 treatment induced lipolysis in WAT when fed a chow diet, while it suppressed lipolysis when challenged with a high-fat, low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet.46,56 In vitro, FGF21 treatment increased basal lipolysis in 3T3L1 adipocytes, but it inhibited hormone-induced lipolysis in 3T3L1 adipocytes and human adipocytes.46,57 These studies suggest FGF21 may exert contrary function on adipocyte lipolysis in adipocytes in response to distinct metabolic states. Moreover, FGF21 robustly stimulated adiponectin secretion in adipocytes.58 Importantly, adiponectin-knockout mice were refractory to several therapeutic benefits of FGF21, including promotion of energy expenditure, alleviation of hypertriglyceridemia, and insulin resistance.58,59 These observations indicate the adiponectin may serve as the main downstream mediator of FGF21. Notably, Han et al identified a feed-forward regulatory loop of FGF21-adiponectin axis in adipose tissue that mediated organ crosstalk.60 In adipocytes, FGF21 autocrine signaling was mediated by JNK pathway and it increased expression of adiponectin.60 The adiponectin subsequently stimulated hepatic FGF21 expression and augmented FGF21 effect in vivo60.

FGF21 is still considered as a promising therapeutic target to treat obesity. Various FGF21 analogs and FGF21 receptor agonists that mimic FGF21 ligand activity are being intensively investigated in clinical trials. For instance, Cui et al found B1344, a PEGylated human FGF21 analog with extended half-life and pharmacokinetics, can promote weight loss, improve glycemic control and alleviate the NASH progression via subcutaneous injection in cynomolgus monkeys with NAFLD.21 Besides, Several FGF21 analogs and mimetics have progressed to clinical trials, such as LY2405319, Pegbelfermin, and AKR-001.24,61, 62, 63 Administration of these drugs reduced hepatic fat fraction, diminished expression of fibrosis biomarkers, and normalized systemic lipid and glucose metabolism in humans.24,61, 62, 63 However, future studies need to cautiously address issues such as the difference in species (e.g., murine vs. human recombinant FGF21), dose, pharmacokinetics, and timing of FGF21 analog treatment.

Adropin

Adropin, first isolated in 2008 by Kumar et al in the liver and brain tissue, is encoded by the Energy Homeostasis Associated Gene (Enho) and is positively regulated by LXRa (a nuclear receptor involved in cholesterol and triglyceride metabolism).64 Adropin is a secretory protein implicated in energy metabolism and inflammatory regulation.65,66 Short-term food intake upregulated its expression, however, chronic exposure to HFD reduced its abundance.64 Consistently, serum Adropin levels were significantly lower in patients with obesity and T2DM, thus may serve as a potential biomarker in predicting obesity-related metabolic disorders.67,68 Compared to wildtype mice, Adropin-transgenic mice showed a resistance to HFD-induced obesity and improved systemic glucose metabolism, although the beneficial effects may be ascribed to decreased food intake.64 Conversely, Adropin knockout mice showed significantly increased adiposity, yet Adropin ablation had little influence on food intake,69 suggesting Adropin may exert a profound impact on adipose tissue per se. Nevertheless, the authors used global overexpression or knockout models in their studies, so liver-specific transgenic models are needed for further investigation on its functions in liver. Intriguingly, short-time administration of the putative secreted domain of Adropin (Adropin34-76) exhibited improved glucose clearance and obese phenotype in HFD fed mice,64,70 indicating Adropin was a promising therapeutic agent for treating obesity and diabetes.

Adropin modulated the proliferation and differentiation of both white and brown preadipocytes.71,72 Mechanistically, Adropin stimulated the proliferation of 3T3-L1 cells and rat primary pre-adipocytes via ERK1/2 and AKT pathway.71 Meanwhile, Adropin reduced lipid accumulation via downregulation the expressions of pro-adipogenic genes, such as Pparg, C/ebpα, C/ebpβ, and Fabp4, suggesting that it antagonizes differentiation of preadipocytes into mature adipocytes.71 Moreover, Stein et al identified a putative Adropin receptor, the orphan G protein-coupled receptor 19 (GPR19) by profiling orphan GPCRs expression and functional validation.73 Besides, the Adropin-mediated GPR19 signal controls mitochondrial fuel metabolism in cardiac cells and water/food intake in the brain,70,73,74 which may expand the scope of the potential therapeutic value of Adropin or its targets for the treatment of metabolic disorders. Nevertheless, the functional validation of GPR19 in adipose tissue using tissue-specific GPR19 knockout model is still missing; thus, it can't exclude the possibility that the Adropin-GPR19 axis expressing in other tissues is mainly responsible for the amelioration of systemic glucose metabolism. Further in-depth studies to investigate Adropin's receptor, cellular targets, and function on adipose tissue in vitro and vivo are in urgent need.

Besides the multiple benefits of Adropin against obesity and diabetes, recombinant Adropin also improved cognitive function in aging mice and enhanced the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in myocardial infarction.75,76 Moreover, the large-scale preparation of Adropin34-76 is also quite facile as it was synthesized by peptide synthesizer, which was a well-established technique with low cost and circumvents the sophisticated post-translational modifications that some other recombinant hepatokine require for their essential functions (see FcsFNDC4).68 Taken together, Adropin may be a promising drug target in the development of treatments against several diseases. Nevertheless, the anti-diabetes and anti-obesity effects are observed after acute treatment with recombined Adropin, thus long-term observation of its benefits needs to be carried out to guarantee its robust function, stability, and therapeutic use on metabolic diseases.

Manf

Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor (Manf) is an endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced secreted protein and originally known as a neuroprotective effector.77,78 Recent reports indicated that Manf was expressed in the liver with highest level and it exerted important roles in systemic metabolic homeostasis.79,80 Dietary restriction and refeeding can induce the Manf expression and secretion in the liver of obese mice.79,81 Meanwhile, circulation Manf level was increased in patients with diabetes and associated with insulin resistance.82,83 However, the underlying mechanism regulating Manf expression has not been further explored.

Liver-specific overexpression of Manf protected mice from HFD-induced obesity, especially lowered adipose mass.79 Mechanistically, Manf treatment promoted whole-body energy expenditure, as evidenced by significant induction of thermogenic genes such as Ucp1, Cidea, Pgc-1α, Dio2 in iWAT, but not in BAT of mice, indicating that increased adaptive thermogenesis was due to iWAT browning, but not BAT activation.79 At cellular level, recombinant Manf treatment significantly induced the phosphorylation of p38 and ATF2 and expression of thermogenic genes in primary adipocytes, and these alterations were completely abolished upon administration of SB203580, a well-established inhibitor of p38α and p38β.79 It suggested that Manf regulated the expression of thermogenic genes via the P38 MAPK pathway. Moreover, Manf also induced lipolysis in the iWAT and eWAT, which further promoted thermogenesis.79 Besides thermogenesis, hepatic overexpression of Manf also reduced proinflammatory M1 macrophages (F4/80+/CD11b+/CD11c+) infiltration and downregulated expression of inflammatory genes such as IL-1β, Tnf-α, leading to amelioration of adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance.79 Taken together, Manf exerts a multifaceted role in adipose tissue function. Moreover, Yagi et al identified Neuroplastin as a receptor for Manf in a rat β-cell line INS-1 832/13 cells.84 However, it remains unclear whether Neuroplastin would be the bona fide receptor for Manf in adipose tissues, thus it is intriguing to assess whether Manf physically interacts with Neuroplastin and mediates Manf's signal pathway in adipose tissue.

In view of its therapeutic application, Wu et al generated a long-acting form of Manf (Manf-Fc) via fusing Manf with the mouse IgG Fc fragment, and weekly administration of recombinant Manf-Fc protein to obese mice lowered their body weight and improved the systemic glucose metabolism.79 Fc fusion ensures the long-term stability of recombinant Manf in vivo. Its long-term pharmacokinetics, toxicity, and side effects in mice and human subjects need to be cautiously assessed.

FNDC4

Fibronectin type III domain containing 4 (FNDC4) is a type I transmembrane protein containing an extracellular domain (FNIII domain), which can be cleaved and released as a secreted protein.85 FNDC4 shows the strongest homology with FNDC5/irisin.86 Unlike FNDC5/irisin, few studies investigate the role of FNDC4 in metabolic disease. FNDC4 expression is highest in the liver and brain, and its plasma level is lower in human with obesity.87

Georgiadi et al found liver-specific silencing FNDC4 exacerbated glucose intolerance and promoted a state of prediabetes.88 Indeed, FNDC4 increased insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake in WAT.88 Besides, FNDC4 also downregulated the expression of the inflammatory genes in WAT.88 Mechanistically, Georgiadi et al identified G-protein coupled receptor 116 (GPR116) as a candidate receptor for soluble FNDC4 with a fluorescence-based binding assay.88 GPR116 was convincingly a functional receptor for FNDC4 as the improvement of glucose tolerance and adipose inflammation mediated by FNDC4 was impaired in adipose tissue-specific GPR116 knockout mice.88 Moreover, the FNDC-GPR116 axis triggered an early Gs-cAMP signaling and subsequent CREB-PKA pathway, and antibody targeting GPR116 inhibited FNDC4-upregulated p-AKT levels in white adipocytes, but the underlying mechanism that the FNDC4-GPR116-Gs-cAMP axis modulates insulin sensitivity and inflammation remains elusive.88 It may ameliorate the insulin resistance via dampening inflammation, as recombinant FNDC4 significantly attenuated severity of colitis in mouse models.85 Meanwhile, FNDC4 treatment inhibited the expression of adipogenesis genes, increased mitochondrial biogenesis and fat browning in human adipocytes,87 indicating FNDC4 may reduce fat accumulation and promote energy expenditure. In consistent, several studies showed GPR116 was involved in the modulation of adipocyte differentiation and adipokines expression, thereby altering systemic insulin sensitivity.87,89 These data further corroborate the hypothesis that agonizing FNDC4-GPR116 signaling may ameliorate insulin resistance and generate metabolic benefits.

For therapeutic application, intraperitoneal injections of long-lived Fc fusion soluble FNDC4 (FcsFNDC4) once every two days improve insulin sensitivity, especially in adipose tissue for as long as 4 weeks,88 indicating targeting the liver–adipose axis by exogenous administration of stable FcsFNDC4 to treat diabetes is promising. Moreover, recombinant FcsFNDC4 has also been investigated as an anti-colitis agent in mouse models and exhibited inspiring effects and safety.85 FNDC4 is likely to be the prototype for drug development in the future. Yet the challenges are: (1) The recombinant FcsFNDC4 was expressed in mammalian cells (CHO cells), it would be of significance to explore whether it can be expressed in bacteria/Drosophila cells as these systems facilitate large-scale production; (2) although administration of FcsNDC4 gave rise to metabolic benefits for up to 4 weeks, it is essential to observe long-term effects for comprehensive evaluation of its potency and side effects.

ORM

Orosomucoid (ORM), a kind of acute-phase protein, is mainly expressed in the liver and also in other tissues under pathological conditions.90 The serum ORM level was higher in obese mice and was positively correlated with BMI and blood glucose levels in humans.91, 92, 93 Lee et al found ORMs were dramatically induced and mainly secreted from the livers of a genetic mouse model with hepatic bile acid accumulation.94 Another study found liver nuclear bile acid receptor FXR could directly bind to the promoter of ORM and stimulate its expression in a tissue- and specie-specific manner.94,95 Besides, the expression of ORM in the liver was also regulated by short-term nutritional stimuli, such as fasting and refeeding.93

Sun et al found ORM1-deficient mice became more obese and showed impaired glucose tolerance, which may be ascribed to ORM1's capability to directly bind with the leptin receptor in the hypothalamus, and activate the JAK2-STAT3 pathway to suppress food intake.93 As for its function in adipose tissue, purified ORM inhibited lipid accumulation and halted adipocyte differentiation in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and primary preadipocytes in a dose-dependent manner.94 To explore which phase of adipogenesis is regulated by ORM, Lee et al treated 3T3-L1 preadipocytes with purified ORM at the initial commitment stage and subsequent differentiation stage, respectively, and found the primary impact of ORM was to decrease the expression of adipogenic transcription factors such as C/ebpβ, and Kruppel-like factor 5 at the commitment phase, and ultimately inhibiting adipocyte differentiation.94 Besides, ORM1-knockout mice were also accompanied with abnormal collagen deposition and upregulation of extracellular matrix regulators, indicating ORM1 represses fibrosis in adipose tissue.96 In line with this conclusion, exogenous ORM1 administration for 7 consecutive days alleviated fibrosis of iWAT in HFD fed mice by increasing abundance of total and phosphorylated AMPK and subsequently inhibiting its downstream targets, TGF-β1-Smad3 signaling in vivo.96 Notably, unlike its binding to leptin receptor in the brain, the anti-fibrotic effect of ORM on adipose tissue existed in leptin-receptor deficient db/db obese mice, suggesting its function on adipose tissue was not directly through leptin receptor.96 As adipose tissue also express ORM locally, liver-specific knockdown instead of global knockdown of ORM is critical for further confirming its function in adipose tissue.

Several lines of evidence propose that ORM can directly bind with cell membrane receptors, such as CCR5 and Siglec-5 neutrophils and mediate its action in vitro.97,98 Especially, like ORM induced AMPK pathway to alleviate fibrosis in adipose tissue, ORM bound with CCR5 and activated the AMPK pathway to increase muscle glycogen accumulation,97 suggesting CCR5 may be a potential receptor for ORM in adipose tissue. It is necessary to construct adipose-specific knockout mice to evaluate whether the anti-obesity effects were abolished upon ablation of CCR5.

Unlike most the other hepatokines, ORM directly ameliorates fibrosis of adipose tissue, which suggests a novel approach to combat obesity. Yet it is premature to define it as a promising therapeutic target as more studies are urgently needed to understand its functioning receptors and its downstream mechanisms.

Activin E

Activin E is a liver-secreted peptide belonging to the TGF-β superfamily and interacts with two types of cell surface transmembrane receptors, Activin A receptor type 1 and 2, which have intrinsic serine/threonine kinase activities in their cytoplasmic domains.99 Recently, Activin E has been recognized as a hepatokine involved in regulating glucose/energy metabolism.100, 101, 102 The expression of Activin E was upregulated in the liver of humans with diabetes and HFD-fed mice.100,103 In vitro studies revealed that insulin can stimulate Activin E production in HepG2 cells through the transcription factor C/EBP.100,104

Sekiyama et al found that global overexpression of Activin E improved systemic insulin sensitivity and elevated Ucp1 expression in BAT as well as in mesenteric WAT even when fed a chow diet.105 Consistently, Hashimoto et al reported that hepatic overexpression of Activin E (Alb-ActE) enhanced energy expenditure and improved systemic glucose metabolism in HFD-fed mice.101 Besides, both BAT, mesenteric WAT, and iWAT of Alb-ActE mice showed an increase in mitochondrial density, multi-locular lipid droplets, and UCP1 positive adipocyte, which indicating browning of WAT and activation of BAT.101 Indeed, Activin E-knockout mice were cold-intolerant compared with wide-type mice.101 Additionally, researchers found that treatment of brown adipocytes with condition medium from hepatocytes with Activin E overexpression can directly upregulate Ucp1 and Cidea expression, and the phenotype can be selectively blocked by SB431542, an inhibitor of TGF-β or activin type I receptors, suggesting Activin E may exert its role through TGF-β or activin type I receptors.101 However, it can't rule out the possibility that unidentified factors in the conditioned medium that were regulated by Activin E could influence adipocytes thermogenesis, thus purified Activin E is in urgent need to investigate its function per se. Given that pharmacological inhibition of TGF-β only provided indirect evidence that TGF-β might be functioning, it is insufficient to claim TGF-β is involved in Activin E's signaling transduction.

Inconsistently, Sugiyama et al disclosed that short-time silencing hepatic Activin E by siRNA decreased fat mass via enhancing lipid utilization in db/db mice.103 The reason for the discrepancy is unknown, probably due to the different genetic mice models used in these studies (such as the knockdown efficiency of Activin E by siRNA was up to 60% in db/db mice for 2 weeks, compared to the Alb-ActE and Activin E knockout mice fed with HFD for 3 months), or the notorious off-target effects of siRNA, and future studies are required to clarify the detailed function of Activin E in adipose tissue metabolism.

For the therapeutic perspective, up to now, it has been still unknown whether the administration of recombinant Activin E can combat obesity and improve insulin sensitivity or not. Future studies are required for further elucidation of its function in vivo and therapeutic application.

Metabolic harmful hepatokines

ANGPTL3

Angiopoietin-like proteins (ANGPTLs) are important secretory proteins governing plasma lipid levels and adiposity.14,106,107 Among them, ANGPTL3 is exclusively secreted from the liver and is a master regulator of lipoprotein metabolism.107,108 ANGPTL3 expression is induced by liver X receptor (LXR) agonists and suppressed by insulin, leptin, and lipopolysaccharide.109 Recent studies showed that serum ANGPTL3 levels were elevated during obesity and T2DM in both mice and humans.110, 111, 112

The association of ANGPTL3 with lipid metabolism was initially found in KK/San mice. KK/San is an obese mouse strain exhibited intriguing diabetic phenotypes with hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, yet with extremely low plasma lipid levels due to loss-of-function mutation in the Angptl3.107,113 In support of this, injection of adenoviruses overexpression Angptl3 or recombinant ANGPTL3 to KK/San mice re-elevated circulating plasma lipid levels.107,113 Further study found that strong binding of fluorescent ANGPTL3 with receptors was observed only in adipose tissue, and administration of recombinant ANGPTL3 directly targeted adipocytes and induced lipolysis to stimulate the release of FFA and glycerol from adipocytes into plasma in vivo.114 ANGPTL3 has two functional domains, an N-terminal coiled-coil domain, and a C-terminal fibrinogen-like domain. Structural analysis indicated that ANGPTL3 formed a complex with ANGPTL8, and the ANGPTL3/8 complex induced significant conformational change in LPL and attenuated its activity.115 Mechanistically, the N-terminal coiled-coil region of ANGPTL3 could bind with LPL and reversibly inhibited the catalytic activity of LPL and promoted furin-mediated LPL cleavage.115

The uptake of FFA from very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) in the blood by extrahepatic tissues depends on LPL activity.116 Feeding suppresses LPL activity in BAT while increases LPL activity in WAT, resulting in inhibiting VLDL-TG uptake by BAT and directing VLDL-TG for uptake and storage by WAT.117,118 Wang et al found that in ANGPTL3 deficient mice, feeding failed to inhibit LPL activity in BAT, and thus further increased VLDL-TG hydrolysis and uptake in oxidative tissues (liver, muscle and BAT), which finally promoted plasma VLDL clearance.119 Meanwhile, ANGPTL3 deficiency decreased VLDL-TG uptake in WAT, concomitantly with a remarkable compensatory increase in glucose uptake and de novo lipogenesis in WAT.119 Pharmacological blockade of circulating ANGPTL3 in wild-type mice showed similar effects,119 indicating neutralizing ANGPTL3 could improve both hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia in obese rodents.

In terms of its clinical relevance, Yang et al identified the variant c. A956G:p.K319R of ANGPTL3 in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia may provide unique insights into the role of ANGPTL3 in risk prediction of dyslipidemia,120 and biochemical study suggested that K319R may be a gain-of-function mutation as potentially increasing ANGPTL3 expression levels.120 Subcutaneous injections of antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) drug targeting Angptl3 mRNA lowered protein levels of ANGPTL3 and atherogenic lipids and lipoproteins, such as triglycerides, LDL-cholesterol, and VLDL both in mice and humans.43,121 Besides, several clinical studies reported that Evinacumab, a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to ANGPTL3 and blocks the ANGPTL3/8-induced inhibition of LPL enzyme activity, decreased serum lipid levels and therefore reduced cardiovascular risk.122, 123, 124 Future study is still needed to define their safety and dissect the exact effect of ANGPTL3 antagonists on obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Fetuin-A

Fetuin-A (FetA), also known as α2-HS-glycoprotein, is the first hepatokine proposed to regulate metabolic homeostasis through organ crosstalk.125 Circulating FetA levels were higher in patients with T2DM compared to patients without T2DM.126,127 Palmitate can promote FetA expression by increasing NF–κB binding to its promotor in vitro.128

As for its role on metabolism, FetA can aggravate WAT dysfunction and insulin resistance during obesity.129 As a classical insulin inhibitor, purified FetA can directly inhibit insulin induced insulin-receptor tyrosine kinase activity and autophosphorylation of the receptor in a cell-free system.130 In vivo, global FetA knockout mice were protected from HFD induced insulin resistance and inflammatory activation in WAT, as evidenced by increased phosphorylation of AKT and decreased phosphorylation of NF-κB.129 Meanwhile, the beneficial effect of FetA deletion was blocked by treatment of recombinant FetA in vivo and vitro.129 Mechanistically, FetA acted as an endogenous ligand for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), thereby inducing FFA-TLR4-mediated inflammatory signaling.129 FetA-TLR4 complex showed a concentration-dependent binding with enormous affinity.129 Pal et al also performed a yeast-based two-hybrid assay and found FetA interacted with the extracellular domain of TLR4,129 and further study identified that leucine-rich repeats sites 2 and 6 of TLR4 bound with FetA and exerted their deleterious effect on insulin sensitivity in 3T3-L1 adipocytes.129 They also identified the terminal β-galactoside moiety of FetA was crucial for recognizing TLR4.129 What's more, Dasgupta et al found FetA entered into adipocytes in a Ca2+-dependent manner and incubated 3T3L1 adipocytes with recombinant FetA and Ca2+ significantly reduced lipid droplets formation.128 In consistent, FetA treatment downregulated the expression of adipogenic factor Pparg and its downstream factors Adiponectin, CD36, and Fabp4, upregulated inflammation markers, and inhibited insulin stimulated glucose uptake, indicating severe impairment of adipose function.128

As for clinical application, a clinical trial (NCT04218305) and meta-analysis found a statistically significant association between FetA levels and T2DM risk, suggesting it may be a useful screening and diagnostic biomarker of T2DM.131 Although the regulatory mechanism of FetA remains largely unknown, FetA is an intriguing target for tuning inflammatory responses, and the antagonists of FetA may efficiently combat insulin resistance. In order to develop FetA-based therapy, specific monoclonal antibodies against Fetuin A should be raised and test their efficacy in vivo.

Follistatin

Follistatin (FST), known as a secreted glycoprotein, binds to and neutralizes diverse ligands of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, such as activin A, myostatin, and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs).132 FST has two isoforms: secreted FST (FST315) and membrane-anchored FST (FST288). Moreover, FST is mainly produced by the liver and its expression is directly regulated by FOXO1.133 FST abundance was upregulated in mice with metabolic disorders and bariatric surgery lowered FST levels in diabetic and obese individuals.132, 133, 134 Tao et al identified that hepatic-derived FST down-regulated insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue.133 Indeed, AAV-mediated overexpression FST315 in the liver attenuated AKT phosphorylation (pT308 and pS473) and diminished insulin-induced glucose uptake in muscle, iWAT, and eWAT, without change in BAT.133 In consistent, hepatic overexpression FST315 attenuated AKT phosphorylation (pT308 and pS473) in WAT.133 Thus hepatic-derived circulated FST promoted insulin resistance in WAT, glucose intolerance and hepatic glucose production.

Intriguingly, CRISPR-Cas9 knockout of FST in adipocyte and preadipocyte (KO) effectively diminished the proliferation of adipocytes, increased lipolysis, lowered the triglyceride levels and abolished p-AKT levels,135 suggesting a reduction of insulin signal in KO cells. The discrepancy may primarily due to the different effects of secreted FST from liver and membraned-bound FST inside adipocytes on metabolism in adipocytes. More efforts are still needed to verify the detail effects of FST on metabolism in different organs by utilization of murine models with liver, adipose tissue, brain-specific knockout respectively and using biochemical approaches to identify the interacting receptors. Specific antibodies against FST to neutralize circulating FST are also essential to leave membrane-bound FST intact and assess their function on systemic metabolism. Thus, the exact function of circulating and intracellular FST can be decoupled and studies separately.

Tsukushi

Tsukushi (TSK), a member of the Small Leucine-Rich Proteoglycan family, contributes to diverse developmental events via binding to distinct molecules such as BMP4/7, FGF8b, TGF-β, and Frizzled.136 TSK is a hepatokine in response to increased energy expenditure induced by triiodothyronine treatment or acute cold exposure.15 Moreover, serum TSK levels were markedly higher in patients with obesity, NASH, and diabetes.137, 138, 139 Besides, Li et al identified single nucleotide polymorphisms rs11236956 variant in TSK from Chinese population to be significantly associated with higher serum TSK levels and multiple metabolic traits such as higher visceral fat accumulation, poor liver function and, and higher propensity for type 2 diabetes in humans with obesity,140 suggesting it may exert important roles on obesity.

Indeed, global TSK knockout mice exhibited lower WAT, BAT, and liver weight than control mice following HFD feeding, concomitant with smaller adipocyte size and lower inflammation in adipose tissue.15 The metabolic effects of TSK inactivation to attenuate obesity were due to stimulated energy expenditure, as evidenced by enhanced lipolysis pathway (PKA-HSL) and subsequent higher expression of thermogenic genes.15 Consistently, the pro-thermogenesis effects of TSK inactivation were blocked by sympathetic denervation.15 Moreover, Wang et al found tyrosine hydroxylase, a rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis was higher in the BAT of TSK knockout mice.15 However, in cellular experiment, recombinant TSK had no significant effects on the differentiation and thermogenesis of brown adipocytes,15 suggesting the influence of TSK on energy expenditure may primarily depend on regulating sympathetic outflow to BAT. Nevertheless, Mouchiroud et al reported that the loss of TSK did not affect the thermogenic activation of BAT, while the overexpression of TSK also failed to modulate thermogenesis, maybe partly because of the alteration in house conditions, diet composition, or gut microbiota composition.141 Furthermore, the function of TSK was performed in genetically ablated models or models with overexpression of TSK, with the conclusion significantly varied with different genetic backgrounds. On the other hand, the administration of recombinant TSK, especially neutralization antibody to obese mice to observe the metabolic phenotype will be more convincing. For identification of its binding partner in adipose tissue, a hormone-binding assay was established and it was found TSK could binding to BAT,15 but the receptor and cellular targets of TSK remained unknown.

As TSK influences sympathetic outflow to BAT, it is important to investigate whether the effects of TSK on sympathetic neurons could cause potential side-effects, such as cardiovascular diseases. Thus, identification of the underlying mechanism of TSK may be necessary prior to design an intervention approach against TSK to combat obesity.

GPNMB

Glycoprotein nonmetastatic melanoma protein B (GPNMB) is classified as a type 1 membrane protein containing an N-terminal signal peptide and expressed in the osteoblasts, melanoma, liver, and WAT.142,143 The cleaved soluble form of GPNMB exerts functions through interaction with cell membrane proteins, such as integrin α5β1, CD44, and Na+/K+-ATPase.144, 145, 146 Recently, several studies found that serum GPNMB level was elevated in both HFD fed mice and patients with obesity and NASH.146, 147, 148 Besides, the transcription of GPNMB in hepatocytes was inversely regulated by SREBP.146

Intriguingly, Gong et al identified GPNMB as a hepatokine modulating fatty acid synthesis in adipose tissue.146 Indeed, recombinant GPNMB treatment induced the expression of lipogenic genes, such as Fasn, Srebp1c, Acc, Acs, Acc, Acl, and Lce in vitro and in vivo146 Mechanistically, the cleaved soluble form of GPNMB bound with membrane receptor CD44 in adipocytes, and activated downstream PI3K-AKT-mTORC1-Srebp1c pathway to promote de novo lipogenesis.146 As confirmation of its function, GPNMB-mediated phosphorylation of AKT and lipogenesis can be mainly blunted by silencing CD44 both in adipocytes and in HFD-fed mice.146 The function was further verified in several distinct mouse models, including administrated with recombinant GPNMB, AAV mediated overexpression or silencing of GPNMB in mice, and transgenic mice with enforced GPNMB expression (Alb-TgGPNMB).146 Moreover, injection of GPNMB neutralization antibody promotes cold-induced BAT activation, reverses pre-existing obesity in mice, dramatically stimulates glucose uptake in BAT, and improves systemic insulin sensitivity.146 These studies support that inhibition of GPNMB by neutralization antibody may warrant therapeutic application in metabolic disorders. Notably, GPNMB is implicated in the progression of breast cancer and melanoma, and is a novel target for cancer treatment.145 Moreover, antibodies against GPNMB have already exhibited their efficacy and safety in cancer treatment, and entered clinical trials.149 These studies raise the possibility that the antibodies aiming at treating cancer may be repurposed to target GPNMB to treat metabolic diseases.

Nevertheless, the inconsistent phenomenon of GPNMB on inducing phosphorylation of AKT in WAT and decreasing glucose uptake in BAT and whole-body insulin sensitivity has not been well studied, which warrants further investigation.

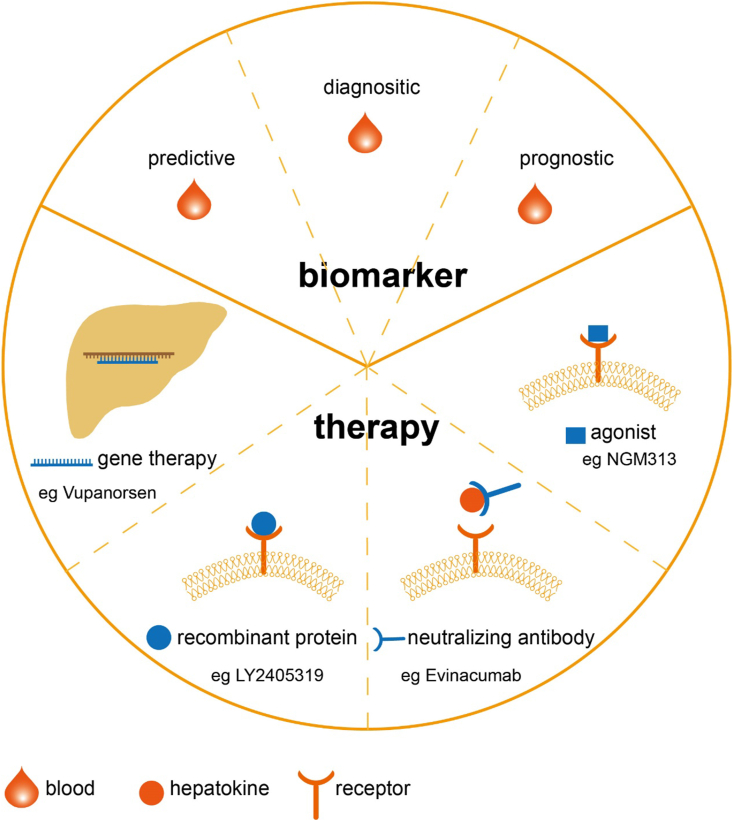

The therapy strategies of hepatokines

As secreted protein accounts for 1/10 in the total human proteome, and they can extravasate into most organs and tissues through circulation, secreted protein and its membrane receptors are attractive therapeutic targets.150 As discussed above, the liver is the essential organ for protein secretion and metabolic regulation, so therapies targeting hepatokines for metabolic diseases have been increasingly appreciated and interrogated. Here we will review the four main hepatokines-based strategies: (1) recombinant hepatokines protein, (2) neutralizing antibodies against hepatokines, (3) agonist or antagonist towards hepatokines receptors, and (4) gene therapy with novel vectors (Fig. 3), which will be extensively discussed below.

Figure 3.

The clinical application of hepatokines. The hepatokines can be known as biomarkers and pharmacological targets in obesity diagnosis and treatment. Noninvasive blood tests evaluating hepatokines levels can help clinical doctors predict and diagnose the metabolic disorder, and provide information for a likely outcome. There are four strategies targeting hepatokines applied in clinical practice. Gene therapy is designed to regulate the expression of hepatokines. Vupanorsen is N-acetylgalactosamine conjugates antisense oligonucleotide thereby degrade ANGPTL3 mRNA. Injection recombinant proteins, such as LY2405319, a PEGylated FGF21, into the circulation can also mimic its role. Besides, agonists activating the receptor of hepatokines, such as NGM313, an agonist towards FGFR1/Klothoβ complex, also restore metabolic homeostasis. At last, neutralizing antibodies are produced to block excess hepatokines. Evinacumab is such a monoclonal antibody against ANGPTL3.

Recombinant hepatokine proteins

For those hepatokines that either lost their functions or downregulated during the progression of metabolic disorders, supplementation of recombinant proteins in vivo to restore their normal function is the most efficient strategy for clinical practice. As secreted proteins suffer from multiple pathways leading to rapid degradation, stabilization of hepatokine in circulation is essential for its application. Given the fact that proteins with low molecular weights are susceptible to renal clearance and secreted proteins might be degraded by proteases in circulation, recombinant proteins often exhibit a short half-life (only a few minutes or hours) and thus frequent injections are needed.151 Several strategies have been developed to delay clearance of circulating hepatokines, increase their bioavailability, and extend half-life time. The most well-established strategies are polyethylene glycol (PEG) modification and fusion protein.151 PEG is a neutral polyether polymer, and proteins modified with PEG show a dramatic increase in molecular size and thereby reduced renal clearance. Meanwhile, the long hydrophilic chain of PEG shields the target protein from recognition by the circulating proteases and protects them from degradation. For example, LY2405319 and Pegbelfermin, the PEGylated FGF21, both exhibited high potency mimicking FGF21 in vivo and entered clinical trials.61,152 Other post-translational modifications, such as glycosylation, also increased biological activity and half-life.153

As for fusion protein hybrids to improve the pharmacokinetics of target proteins, the most widely used scaffolds are human serum albumin and Fc.154 Albumin has a long average half-life (19 days) and is responsible for transporting endogenous and exogenous molecules in circulation. The fusion of therapeutic proteins with albumin ligands (the best ligand is an 18-amino acids peptide named 89D03) in a non-covalent way stabilizes the protein in the circulation; secondly, albumin can be directly fused with target proteins to enhance the stability.154 Bern et al demonstrated that human albumin variant E505Q/T527M/K573P fused with recombinant activated coagulation factor VII enhanced its plasma half-life and enabled it to penetrate through nasal mucosal barriers.155 Fusion with the Fc region also increases the size and molecular weights. Besides, it can also promote Fc-mediated recycling, thereby minimizing cellular degradation. Rolph et al found injection with an Fc-FGF21 analog, AKR-001, once per week, can improve insulin sensitivity in T2DM patients.62 Recently, protein–drug nanocarriers via non-covalent self-assembly also showed several advantages, but their application in metabolic disease has just started.156 Another strategy to produce long-acting protein is to generate site-specific mutant proteins. For example, a few amino acid substitutions in the GLP1 (A8G/G22E/R36G) resulted in resistance to DPP4 digestion, improved solubility, and reduced immunogenicity.157

In conclusion, these promising recombinant proteins can elicit sustained therapeutic efficacy through prolonged half-life in vivo. One future strategy is that they can be modified with the hydrophobic chains and increased their binding affinity to albumin or Fc in circulation. Meanwhile, the mutagenesis of conserved residues recognized by proteases renders their higher stability. It is thus likely to combine these strategies to generate synergistic effects.

Antibodies against hepatokines

For those hepatokines with upregulation during the progression of metabolic diseases or promoting these diseases, monoclonal antibodies are rapid growing therapeutics as they are the most facile drugs to inactivate these dysregulated hepatokines. The primary strategies to develop therapeutic antibodies are a combination with chemical conjugation and fusion protein to improve stability, affinity maturation to enhance affinity and reduce cross-reactivity, and humanized antibodies to reduce immunogenicity.158,159

Currently, several studies have already exhibited their metabolic benefits in preclinical models and human subjects, which paves the way for their translational studies in the future. For instance, Mita et al have raised neutralizing antibody AE2 against Selenoprotein P, a hepatokine promoting insulin resistance.160 AE2 effectively improved glucose intolerance and insulin secretion in vivo.160 More surprisingly, Evinacumab, a monoclonal antibody against ANGPTL3, significantly reduced the LDL cholesterol level of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia patients in a phase III trial.161

Notably, repurposing of existing hepatokine antibodies that treating other diseases may offer alternative therapeutic modalities since their efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety are known and well-tolerated. GPNMB is overexpressed in a variety of tumors and promotes tumorigenesis, and its monoclonal antibody Glembatumumab conjugated with cytotoxic agents has entered clinical trials to treat multiple cancers.149 This study has at least two potential implications in hepatokine therapy and the concept is worthy of testing: (1) As an efficacious antibody against GPNMB, Glembatumumab alone may neutralize GPNMB in circulation and enhance energy expenditure; (2) Glembatumumab may conjugate with small molecule modulators of metabolic diseases, such as rosiglitazone and targets adipose tissues to remodel the metabolism inside and improves insulin resistance. In summary, the concept of antibody-small molecule conjugate that is well-established in cancer research can facilitate the enrichment of small molecules targeting hepatokine signaling pathways in adipose tissues, while lowering their adverse effects.

Agonist or antagonist towards hepatokines receptors

Protein-based agonist or antagonist

Agonizing hepatokine receptors by delivering protein agonists in vivo mimics the effects of hepatokines. A major subcategory of protein-agonists is the modified-recombinant proteins, also termed analogs. The strategy to prepare these recombinant proteins has been described in section: Recombinant hepatokine proteins. Thus, the key points discussed here are antibody-based agonists and antagonists towards hepatokines receptors. For example, NGM313 and bispecific BFKB8488A (an anti- FGFR1/Klothoβ agonist antibody), are agonists of FGFR1/Klothoβ complex, and specifically activate FGFR signaling, thereby improving metabolic parameters.162,163 More inspiring is that in randomized trials, transient body weight loss was observed and cardiometabolic parameters were persistently improved in human subjects with obesity.162

For antibodies antagonizing receptors of hepatokines, the current well-established therapeutic antibodies may be repurposed to blockade the signaling of pathogenic hepatokines. Fetuin-A binds to TLR4 to mediate subclinical WAT inflammation, targeting TLR4 may be more pragmatic compared to design novel Fetuin-A antibodies as TLR4 antagonists are extensively evaluated to treat immune, infectious or other diseases.164, 165, 166, 167 Studies indicate that human anti-TLR4 IgGs protected mice from the sepsis induced by the LPS challenge and prolonged the survival rate,164 its application in treating obesity and other metabolic disorders thus warrants further investigation as it effectively abolished the inflammation, which is beneficial to treat metabolic disorders.

The small molecule agonist and antagonist of receptors

Compared with therapeutic proteins, small molecules show satisfying pharmacokinetics and compliance for oral administration, thus consisting of an important class of drugs. As receptors of hepatokines also regulate other pivotal (patho)physiological processes, small molecules for receptors of hepatokines have already been developed for treating various diseases.

Although there are few studies about the small molecular-based agonists or antagonists of hepatokines, numerous agonists or antagonists towards other hormone receptors have been well-studied and exhibiting great potential. The most well-known agonist in treating metabolic disease is rosiglitazone, a PPARγ-selective agonist, which significantly improves insulin sensitivity in vivo.168 As TLR4 play a key role in mediating inflammation, numerous small molecule modulators have been intensely interrogated, ranging from anti-neoplasm, anti-inflammation, nephropathy, anti-fibrosis, etc.169 Some TLR4 antagonists have entered clinical trials for treating MAFLD/NASH.170 Extensive investigations indicate TLR4 as a reliable therapeutic target and it merits further study in blocking TLR4 signaling in adipose tissue with small molecules to suppress Fetuin-A signaling.

Inhibiting proteases that degrading hepatokines can enhance their efficacies in vivo as well. Recently, Cho et al reported a novel small molecule-based study to enhance the stability of FGF21 by inhibition of endogenous protease that degrades FGF21.171 Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) is a member of the DPP family of serine proteases that cleaves both N- and C-terminus of FGF21 in circulation and contributes to its short half-life in vivo.172 Inhibition of FAP by the inhibitor BR103354 ameliorated diabetic phenotypes and liver steatosis in mice.171 BR103354 is highly potent (IC50 = 14 nM) and dramatically elevated plasma FGF21 levels.171 As high throughput screening of protease inhibitors is well-established in pharmaceutical research, it points out an alternative approach to agonize hepatokine function in vivo.

Nevertheless, there is still a large number of hepatokines that lack effective recombinant proteins or antibodies. Besides, preclinical and clinical studies are also needed to explore these therapies, including their potential mechanisms, pharmacokinetics, best dosages, side effects, and so on.

Highly efficient and specific gene editing for studying hepatokine function and their therapeutic applications

Although several secreted protein based therapeutic agents apply to clinical trials, effective therapies are still missing for most hepatokines. Gene-editing technology that selectively manipulating the expression levels of hepatokines in the liver and adipose tissue will be pivotal for in-depth study of their functions. Here we will summarize the development of novel technologies in hepatokine research and propose strategies to target them for translational research in future studies.

Adeno-associated viruses

Viral vectors are highly efficient vehicles that infect target organs and tissues by interacting with specific membrane receptors and internalized them to express transgenes in host cells. Among the viral vectors, adeno-associated viruses (AAV) are the well-established vectors that several AAV-based gene therapies have been approved in the USA and European Union for treating various genetic disorders in human subjects.173 AAVs persistently transduce organs with high infection rates, which depending on distinct serotypes. Then they are internalized into the host cells and enter the nucleus, where they are uncoated to release their genome and initiate the transcription of transgenes.174 AAV serve as the most effective gene therapy due to (1) Their low immunogenicity in vivo; (2) High transduction rate of target organs and high expression levels of transgenes; (3) Their sustainable expressions last for months, and specifically target the liver, adipose, eyes, muscle, etc. (4) Unlike lentiviral and retroviral vectors, AAVs usually don't incorporate into host genomes, thus they are safe at genomic levels. Currently, there are 166 undergoing AAV-based clinical trials in the USA treating hematologic diseases, muscular diseases, and HIV infection, indicating an unprecedented burgeoning field of AAV technology.

Tissue-specific knockout or knock-in of target genes usually requires rounds of animal mating and is time-consuming, and if the knockout of critical genes in vivo is lethal or generates developmental defects, it will confound the interpretation of the results. AAV circumvents the problems by transducing adult animals and is a powerful tool to rapidly decipher the functions of secreted proteins. For example, overexpression of FGF21 in murine livers showed a sustainable expression level for at least 8 months and induced a stable decrease in body weight of obese mice.175 AAV encoding shRNA and CRISPR-Cas9 editing enzymes/gRNA are also implicated in loss-of-function study. For CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, the liver-specific transduction of AAV and gene editing can be ensured by the tissue-specific promoters such as thyroxine binding globulin (TBG) and albumin. Song and co-workers silenced hepatic GPNMB mRNA with AAV8-shRNA and greatly enhanced energy expenditure and GTT response.146 Consistent with this, hepatic inactivation of other hepatokines, for instance, Follistatin,133 Tsukushi15 expression with AAV-CRISPR-Cas9, and DPP4176 with shRNA resulted in alleviated hyperglycemia, improved insulin sensitivity, and improved glucose homeostasis, respectively.

As for clinical practice, several AAV-drugs targeting hepatokines or liver diseases come to clinical trial. Among these, AAV-based overexpression of coagulation factors to raise their plasma levels to treat hemophilia is most commonly used. AAV-treated patients with severe hemophilia B exhibited partially rescued coagulation factor IX activity from 1% to 6% of the normal value and remained constant for a median of 3.2 years.177 AAV-based heptokines to treat metabolic disorders may also hold promise as liver transduction is usually the most efficient. Although AAV has the numerous advantages of in vivo therapy, during long-term administration, it has some drawbacks of future application in hepatokine-based therapy:(1) It has a 4.7 kb of package limit, thus limiting the transgenes that it can express in vivo; (2) Its long-term use and repetitive dosage may evoke a host immune response that generates autoantibodies and thus may compromise the efficacy of AAV.174

Novel non-viral delivery systems for silencing hepatokine

GalNAc-siRNA is a novel non-viral delivery system that exhibits low immunogenicity, high selectivity targeting hepatocytes, and is resistant to protein degradation systems. GalNAc conjugates exert function through binding with the asialoglycoprotein receptor, facilitating them internalized into hepatocytes and releasing conjugated siRNA or antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) in acidic endosomes and lysosomes.178 ASOs are chemically modified oligonucleotides that bind to mRNA sequences to knockdown target genes.179 The chemical modifications stabilize ASO and enhance its binding affinity. ASO demonstrated high potency in silencing genes in human subjects and by 2020, there are 9 FDA-approved ASO-based therapies and 39 ongoing clinical trials in USA.179

For the application of GalNAc-ASO in anti-obesity studies, Mahlapuu and co-workers delivered ASO of serine/threonine-protein kinase 25 in hepatocytes of mice fed with an HFD.180 It remarkably silenced STK25 and protected mice from diet-induced obesity.180 Particularly, Vupanorsen, a GalNAc modified ASO targeting hepatokine ANGPTL3 mRNA, has entered a phase II clinical trial and showed improved serum lipid and lipoprotein profile.43

Besides liver, delivery systems targeting adipose tissue and silencing of target genes exhibited anti-obesity activities.181, 182, 183 Notably, Hiradate et al constructed the PPARγ agonist, Rosiglitazone-loaded nanoparticles with two types of PEG spacers (PEG5k and PEG2k) as cores.184 The surface of PEG is then modified with a cell-penetrating peptide motif (RRRRRRRR) and a peptide motif (CKGGRAKDC) that recognizes prohibitin expressed in vascular endothelial cells of WAT. This nanoparticle effectively targeted adipose tissues of HFD mice and release rosiglitazone to induce browning activity.184 Moreover, Chung et al reported that the same motifs are conjugated with nanoparticles containing dCas9/sgFabp4, the CRIPSRi system that repressed the expression of Fabp4.185 In vivo white adipocyte-specific delivery rendered reduction in body weight, inflammation, and hepatic steatosis in mice.185 It will shed new light on the development of adipose-targeting therapies as the small molecule, protein modulators, and Cas9/sgRNAs of hepatokine receptors. For genetic manipulation, researchers could decide to manipulate hepatokine expression in the liver or knockdown its downstream effectors in adipose tissue with vectors bearing tissue-specific ligands binding to the cell surface of adipocytes. We propose that GalNAc-siRNA, as well as adipose-targeting nanoparticles, can greatly accelerate hepatokine studies in terms of mechanistic and translational research in the long run.

Summary

To maintain energy homeostasis, multiple metabolic organs (such as liver, adipose tissue, and muscle) crosstalk with each other via distinct signals. These interactions are remodeled under pathological conditions such as obesity and T2DM. In this review, we summarize well-established mechanisms of hepatokines mediating liver-adipose tissue crosstalk (Fig. 2 and Table 1) and outline how this network helps us to re-shape therapeutic strategies to promote healthy living styles and combat metabolic disorders (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Hepatokines can be categorized into two subgroups in terms of their function on obesity: metabolic beneficial hepatokines and metabolic harmful hepatokines. Hepatokines remodel adipose tissue in a two-pronged way: on one hand, metabolic beneficial hepatokines counter obesity through interacting with specific receptors in adipose tissue, leading to enhanced glucose uptake and thermogenesis (e.g., FGF21, Adropin), or inhibiting excess fat accumulation, inflammation and fibrosis of adipose tissue (e.g., ORM1); on the other hand, metabolic harmful hepatokines (e.g., ANGPTL3) act at the opposite direction by interacting with their distinct cognate receptors to promote obesity.

Figure 2.

The functional roles of hepatokines on adipose tissue metabolism. Metabolic beneficial or harmful hepatokines bind with and signal through their receptors on adipose tissue and influence downstream pathway, further regulate multifaceted function of adipocytes, including glucose uptake, thermogenesis, lipolysis, inflammation, fibrosis, adipogenesis, proliferation and lipogenesis, which finally modulate fat accumulation and insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue and whole-body metabolism.

Table 1.

Functions of hepatokines on adipose tissue and clinical application.

| Hepatokine | Full name | Source of hepatokine | Transcriptional regulation | Receptors or ligands | Functions on adipose tissue | Serum concentration in metabolic disorder | Clinical use in metabolic disorder (https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) | references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGF21 | Fibroblast growth factor 21 | Mainly liver, pancreas, brain, adipose tissue | PPARγ, PPARα and ChREBP | FGF receptor 1c/β-klotho complex | WAT: glucose uptake↑; lipolysis↑/↓, adiponectin↑ and WAT browning↑ | Humans with obesity, T2DM↑ HFD feed mice, ob/ob, db/db mice↑ |

Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker treatment (FGF21 analog): LY2405319, Pegbelfermin (BMS-986036), AKR-001 GLP-1-Fc-FGF21 dual antibody; B1344; and PF-05231023 |

22,24,42,46,47,49,55,57,61, 62, 63,188, 189, 190, 191, 192 |

| BAT: energy expenditure and fat utilization↑, thermogenic genes (e g., UCP1) ↑ | ||||||||

| ANGPTL3 | Angiopoietin-like protein 3 | Mainly liver | liver X receptor | lipoprotein lipase (LPL) | WAT: LPL activity↓, lipolysis↑, FFA uptake↑ thereby decreasing DNL and glucose uptake↓ | Humans with obesity, coronary artery disease ↑ | Treatment: Evinacumab (antibody of ANGPTL3); Vupanorsen (an N-acetyl galactosamine-conjugated antisense oligonucleotide drug to ANGPTL3 mRNA) | 43,107,109,110,114,119,122, 123, 124,193 |

| ANGPTL4 | Angiopoietin-like protein 4 | Liver, adipose tissue | PPARs and HIF1α | lipoprotein lipase (LPL) | WAT: LPL activity↓ | Humans with obesity, NAFLD ↑ | Treatment: REGN1001 (ANGPTL4-neutralizing fully human monoclonal antibody) | 193, 194, 195, 196, 197 |

| ANGPTL6 | Angiopoietin-like protein 6 | Mainly liver, adipose tissue | BAT and WAT: stimulates energy expenditure↑, PGC-1 and UCP1 ↑ | Humans with diabtes, obesity↑ | 198, 199, 200 | |||

| FetA | Fetuin-A | Mainly liver, adipose tissue | NF-κB | Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) | WAT: subclinical inflammation ↑; macrophage migration and polarization of macrophages↑; adiponectin↓ | Humans with obesity, T2DM↑ | Diagnostic biomarker | 126, 127, 128,131,201,202 |

| Adropin | Adropin | Liver, brain | liver X receptor α | G protein-coupled receptor, GPR19 | WAT: fat accumulation↓, adiponectin↑, lipogenesis↓; proliferation↑; differentiation↓; adipose inflammation↓ | Humans with obesity, T2DM, NAFLD↓ Mice feed a NASH diet↓ |

Diagnostic and prognostic biomarker | 64,66,67,69,71,73,203, 204, 205 |

| FST | Follistatin | Mainly liver | FOXO1 | Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily, such as activin A, myostatin, and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) | WAT: Akt phosphorylation and glucose uptake↓; insulin sensitivity↓ | Humans with T2DM↑ | 132, 133, 134,206 | |

| Activin E | Activin E | Mainly liver | C/EBP | Activin receptor type-1 and type-2 (ACVR1 and ACVR2) | WAT: fat mass↑/↓, WAT browning↑ and UCP1 and FGF21↑ | 99, 100, 101,103, 104, 105 | ||

| BAT: energy expenditure↑ | ||||||||

| TSK | Tsukushi | Mainly liver | BMP4/7, FGF8b, TGF-β and Frizzled | WAT: adipocytes size↑, genes associated with macrophages and adipose inflammation↑ | Mice feed a HFD, NASH diet, MCD diet, db/db mice↑ | 15,136,138,139 | ||

| BAT: energy expenditure↓ | ||||||||

| GPNMB | Glycoprotein nonmetastatic melanoma protein B | Osteoblasts, melanoma, liver, adipose tissue | SREBP | integrin α5β1, CD44 and Na+/K+-ATPase | WAT: adipocytes size↑, lipogenesis↑, WAT browning BAT: UCP1↓, energy expenditure↓ |

Humans with obesity, NAFLD↑ HFD feed mice, ob/ob mice↑ |

142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147 | |

| Manf | Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor | Liver, brain | Neuroplastin | WAT: adipocytes size↓, lipolysis↑, WAT browning, inflammation↓, insulin sensitivity↑ | Humans with T1DM, T2DM↑ HFD feed mice, ob/ob mice↑ |

77, 78, 79,81 | ||

| FNDC4 | Fibronectin type III domain containing 4 | Liver, brain | G-protein coupled receptor 116 (GPR116) | WAT: inflammation↓, insulin sensitivity↑ | Humans with obesity↓ HFD fed mice ↑ |

86,88,89 | ||

| ORM | Orosomucoid | Mainly liver, also adipocytes, heart, and brain | CCR5 and Siglect-5 | WAT: adipogenesis↓ | Humans with T1DM ↑ HFD feed mice, db/db mice↑ |

94, 93, 92, 91 | ||

| LECT2 | Leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin 2 | Mainly liver | Toll-Like Receptor 3 | tyrosine kinase with immunoglobulin-like and EGF-like domains 1 (Tie1) | 3T3L1: P38 phosphorylation↑; inflammation markers↑; insulin signaling↓; lipid accumulation↑ | Humans with obesity, T2DM, NAFLD ↑ | 212, 211, 210, 209, 208, 207 | |

| RBP4 | Retinol-binding protein-4 | Mainly liver, also adipose tissue | stimulated by retinoic acid-6 (STRA6) and RBP4 receptor-2 (RBPR2) | WAT: antigen-presenting cells↑; macrophage and CD4 T-cell ↑, and adipose tissue inflammation↑, and may increases mobilization of FFAs from adipocytes↑ | Humans with obesity, T2DM↑ | Prognostic biomarker | 218, 217, 216, 215, 214, 213 | |

| DPP4 | Dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 | Liver, adipose tissue and Intestinal | NF-κB, HIF1α | caveolin-1 (Cav1) and proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR2) | WAT: fat mass↑; adipose tissue inflammation↑; and impair insulin pathway↓ | Humans with obesity, T2DM, NAFLD↑ | Treatment (DPP4 inhibitor): linagliptin; saxagliptin; DBPR108; alogliptin and anagliptin |

176,187,224, 223, 222, 221, 220, 219 |

| BAT: PPAR-α, PGC-1, and UCP1↓ | ||||||||

| Selenoprotein P, SHBG, Hepassocin: mainly expressed and secreted by the liver, also play significant roles in glucose and lipid metabolism, but there are little studies demonstrate their functions in adipose tissue. | 160,230, 229, 228, 227, 226, 225 | |||||||

However, it has not been clear so far whether abnormal secretion of hepatokines causes metabolic dysfunction or whether dysregulation of hepatokines is secondary to the onset of metabolic disorders, or possibly both. Emerging evidence documents that liver steatosis and inflammation lead to altered expression and secretion in some hepatokine (e.g., FetA, Adropin, TSK, GPNMB), which further deteriorates the metabolic dysregulation in adipose tissue. On the other hand, numerous studies also revealed that the abundance of some hepatokine (e.g., Activin E, FGF21) surges during the development of obesity, which counteracts metabolic disorder, suggesting a resistant status of these secreted proteins under pathological conditions.

It is clinically more pragmatic to manipulate the abundance of secreted proteins in circulation with antibody or recombinant protein compared to intracellular proteins, and thus circulating proteins are a rich reservoir of druggable targets, such as DPP4 and GLP1.186,187 Hepatokines circulate throughout the body and, therefore, have access to most organs and tissues. Mimicking or blockade the function of hepatokines may be a promising therapeutic strategy against metabolic diseases. Indeed, several studies with the hepatokine analogs displayed clinically relevant effects on several metabolic comorbidities associated with obesity. Alternatively, pathogenic hepatokines could be silenced in situ by the specific RNA interference approach, instead of blockade its end products-circulating proteins. GalNAc-siRNA/ASO delivery system thus enables researchers to shut down the expression of these hepatokines and it is well-tolerated and effective as revealed by preclinical studies and clinical trials. Yet overall speaking, there is still tremendous work to be done to understand the physiological functions of hepatokines in humans as well as their pathophysiological roles and pharmacological potencies on human metabolic disease. Also repurposing of current therapies against hepatokine receptors or antibodies that aim at treating other diseases are of great value, as preclinical and clinical studies have validated the potency and safety of these interventions.

In summary, the hepatokines function as highly specific and efficient mediators for the crosstalk between the liver and adipose tissue to maintain energy homeostasis. They have served as not only causative biomarkers and/or predictors but also promising drug targets for the onset of obesity-associated metabolic disorders. Further preclinical and clinical studies are necessary to confirm these hypotheses.

Author contributions

Yao Zhang and Junli Liu designed the study. Yao Zhang, Yibing Wang, and Junli Liu wrote the manuscript. Yibing Wang and Junli Liu supervised the revision of the manuscript. All authors take responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interests

Authors declare no conflict of interests.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2018YFA0800600); National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81770797); National Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars (No. 31722028); Training Program of the Major Research Plan of the National Natural Science Foundation (No. 91857111); Shanghai Municipal Commission of Science and Technology (No. 20410713200); National Facility for Translational Medicine (Shanghai)(NO. TMSK-2020-102); Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (No. 20SG10); and Shanghai University of Sports and National Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars (No. 31722028).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chongqing Medical University.

Contributor Information

Yibing Wang, Email: 0022706@fudan.edu.cn.

Junli Liu, Email: liujunli@sjtu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Bhupathiraju S.N., Hu F.B. Epidemiology of obesity and diabetes and their cardiovascular complications. Circ Res. 2016;118(11):1723–1735. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Goblan A.S., Al-Alfi M.A., Khan M.Z. Mechanism linking diabetes mellitus and obesity. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:587–591. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S67400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polyzos S.A., Kountouras J., Mantzoros C.S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: from pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism. 2019;92:82–97. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longo M., Zatterale F., Naderi J., et al. Adipose tissue dysfunction as determinant of obesity-associated metabolic complications. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(9):2358. doi: 10.3390/ijms20092358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kusminski C.M., Bickel P.E., Scherer P.E. Targeting adipose tissue in the treatment of obesity-associated diabetes. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(9):639–660. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leal L.G., Lopes M.A., Batista M.L., Jr. Physical exercise-induced myokines and muscle-adipose tissue crosstalk: a review of current knowledge and the implications for health and metabolic diseases. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1307. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caron A., Lee S., Elmquist J.K., et al. Leptin and brain-adipose crosstalks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19(3):153–165. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2018.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jensen-Cody S.O., Potthoff M.J. Hepatokines and metabolism: deciphering communication from the liver. Mol Metabol. 2021;44:101138. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefan N., Haring H.U. The role of hepatokines in metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9(3):144–152. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meex R.C.R., Watt M.J. Hepatokines: linking nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(9):509–520. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smati S., Régnier M., Fougeray T., et al. Regulation of hepatokine gene expression in response to fasting and feeding: influence of PPAR-α and insulin-dependent signalling in hepatocytes. Diabetes Metab. 2020;46(2):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seo J.A., Kang M.C., Yang W.M., et al. Apolipoprotein J is a hepatokine regulating muscle glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2024. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15963-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montgomery M.K., Bayliss J., Devereux C., et al. SMOC1 is a glucose-responsive hepatokine and therapeutic target for glycemic control. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(559) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz8048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheja L., Heeren J. Metabolic interplay between white, beige, brown adipocytes and the liver. J Hepatol. 2016;64(5):1176–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q., Sharma V.P., Shen H., et al. The hepatokine Tsukushi gates energy expenditure via brown fat sympathetic innervation. Nat Metab. 2019;1(2):251–260. doi: 10.1038/s42255-018-0020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watt M.J., Miotto P.M., De Nardo W., et al. The liver as an endocrine organ-linking NAFLD and insulin resistance. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(5):1367–1393. doi: 10.1210/er.2019-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peppler W.T., Castellani L.N., Root-McCaig J., et al. Regulation of hepatic Follistatin expression at rest and during exercise in mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1116–1125. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Banerjee S., Ghoshal S., Stevens J.R., et al. Hepatocyte expression of the micropeptide adropin regulates the liver fasting response and is enhanced by caloric restriction. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(40):13753–13768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.014381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pineda C., Rios R., Raya A.I., et al. Hypocaloric diet prevents the decrease in FGF21 elicited by high phosphorus intake. Nutrients. 2018;10(10):1496. doi: 10.3390/nu10101496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seo D.Y., Park S.H., Marquez J., et al. Hepatokines as a molecular transducer of exercise. J Clin Med. 2021;10(3):385. doi: 10.3390/jcm10030385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cui A., Li J., Ji S., et al. The effects of B1344, a novel fibroblast growth factor 21 analog, on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in nonhuman primates. Diabetes. 2020;69(8):1611–1623. doi: 10.2337/db20-0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geng L., Lam K.S.L., Xu A. The therapeutic potential of FGF21 in metabolic diseases: from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(11):654–667. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-0386-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]