Abstract

When conducting a literature review, medical authors typically search for relevant keywords in bibliographic databases or on search engines like Google. After selecting the most pertinent article based on the title’s relevance and the abstract’s content, they download or purchase the article and cite it in their manuscript. Three major elements influence whether an article will be cited in future manuscripts: the keywords, the title, and the abstract. This indicates that these elements are the “key dissemination tools” for research papers. If these three elements are not determined judiciously by authors, it may adversely affect the manuscript’s retrievability, readability, and citation index, which can negatively impact both the author and the journal. In this article, we share our informed perspective on writing strategies to enhance the searchability and citation of medical articles. These strategies are adopted from the principles of search engine optimization, but they do not aim to cheat or manipulate the search engine. Instead, they adopt a reader-centric content writing methodology that targets well-researched keywords to the readers who are searching for them. Reputable journals, such as Nature and the British Medical Journal, emphasize “online searchability” in their author guidelines. We hope that this article will encourage medical authors to approach manuscript drafting from the perspective of “looking inside-out.” In other words, they should not only draft manuscripts around what they want to convey to fellow researchers but also integrate what the readers want to discover. It is a call-to-action to better understand and engage search engine algorithms, so they yield information in a desired and self-learning manner because the “Cloud” is the new stakeholder.

Keywords: Medical Subject Headings, Key words, Search engine optimization, Access, Citation, Impact factor

Core Tip: Reputable journals like Nature and British Medical Journal lay emphasis on ‘online searchability’ of articles in their author guidelines. This article urges medical colleagues to ‘look inside-out’ when drafting manuscript – to not only draft manuscripts around what we want to tell fellow researchers, but rather draft it in such a way that it embeds well what they are looking for. We hope that following these best practices will make it easier for search engines to crawl, index, and understand your articles to present them higher on the web-based-search results. Employing these strategies are often about making small modifications to the manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The famous joke, “Where should you bury something that you do not want people to find? - On the second page of Google,” carries an important message for medical researchers on what the authors need to pay close attention to. Studies show that nearly 75% of users never scroll past the first page of search results when searching for general information on Google[1]. Additionally, the first position on Google’s organic search results has a 32% click-through rate[2].

In medical literature, when performing a literature review for draft manuscript “A”, the usual sequence of actions involves searching for keywords within bibliographic databases or search engines like Google. After selecting the most relevant article “B” based on the title’s relevance and reading the abstract’s content, they download or purchase the article and cite it in their manuscript “A.” In this process, three major elements drive the reader to ultimately cite the article “B”: The keyword, the title, and the abstract. This indicates that title, abstract, and keywords are “key dissemination tools” for research papers. If these three elements are not determined judiciously by authors, it may adversely affect the manuscript’s retrievability, readability, and citation index, which can negatively impact both the author and the journal.

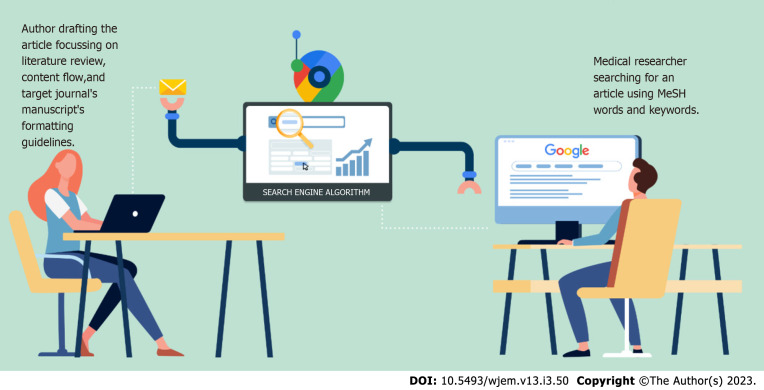

By comparison, when an author writes an article “B” that deserves to be cited in another article “A,” their efforts are mainly focused on conducting a literature review, ensuring a content flow, and meeting the target journal’s manuscript formatting requirements. As a result, “keywords”, “title,” and “abstract” are often considered the last steps in this exhaustive process and are sometimes trivialized or obliviously determined while submitting the manuscript in the journal’s portal.

The success of the author is typically measured by the number of manuscripts they have authored and the number of citations those articles have received. However, for an article to be cited, it must be retrievable by readers through a search engine[3]. It is evident from the above comparison that the medical community has not yet fully explored the potential offered by search engines to rank higher for specific search terms within the vast expanse of the internet and thereby enhance access to medical literature. This discrepancy between the approach of embedding keywords when an author drafts an article versus when a reader searches for it is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The discrepancy between the approach of embedding keywords when an author drafts an article vs when a reader searches for it.

In this manuscript, we share our informed perspective on writing strategies that can enhance the searchability and citation of medical articles. These strategies are adapted from the principles of search engine optimization (SEO) in content marketing. We do not intend to cheat or manipulate the search engines but rather adopt a reader-centric content writing methodology that embeds well-researched keywords that are targeted towards those readers who are searching for them, thereby enhancing the article’s discoverability and reach. The central theme of this article is to encourage medical authors to shift their perspective and “look inside-out” when drafting manuscripts. In other words, they should not only draft manuscripts around what they want to convey to fellow researchers but also integrate what the readers want to discover. Within this manuscript, we describe the medical article indexing systems and propose strategies for enhancing the retrievability of published articles across search engines. A tabular comparison with the non-medical content writing strategies of SEO is also included.

SETTING THE BACKDROP: WHAT ARE THE MEDICAL MANUSCRIPT INDEXING SYSTEMS?

For brevity, the indexing systems employed by PubMed and Google are discussed here.

PubMed

PubMed is a web-based resource that provides free access to research publications. It is an excellent first choice to review medical research topics, as it indexes over 5000 journals and nearly 30 million journal article references, covering all of the pre-clinical sciences and biomedicine. Phrases in PubMed are recognized through the subject translation table used in the system’s Automatic Term Mapping. For example, if we enter “fever of unknown origin,” PubMed recognizes this phrase as a Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) term. The National Library of Medicine (NLM) created a controlled, pre-defined, hierarchically organized vocabulary called the MeSH thesaurus, which is used for searching, indexing, and listing biomedical and health-related information. MeSH includes the subject headings appearing in MEDLINE, PubMed, the NLM Catalog, and other NLM databases. When standardized terms are used to search a topic, all the articles indexed in NLM's PubMed and MEDLINE are retrieved, resulting in an increase in citations for the article. Controlled vocabularies are systematic, hierarchical arrangements of words and phrases designed to describe and categorize the major subject concepts and conditions contained within a database. They can be different for different databases. The hierarchical nature of these lists narrows the search to fewer yet more specific results, keeping it consistent within that framework. Before adding an item to a database or catalog, the subject matter is determined, and specific terms that apply to those subjects are chosen from a predetermined list, regardless of the terminology used by the author within the item. The listing is standardized and predictable to an extent, ensuring a uniform system for retrieving the same concepts even when different terminology is used. For example, the term "heart attack" is always listed as "myocardial infarction" within a controlled vocabulary structure such as MeSH, the vocabulary used by MEDLINE. The disadvantages of MeSH are enumerated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Disadvantages of Medical Subject Headings

|

Disadvantages of MeSH

|

| 1 MeSH terms are manually assigned to articles after an article is made available on PubMed. Manually assigned MeSH terms are not available for recently published articles. This is a time-consuming process, and hence, these articles fail to appear in search results when only MeSH terms are used for searching |

| 2 In a scenario where no appropriate MeSH term is found while searching for a concept, it becomes important to search for relevant words in the title and abstract as well |

| 3 Mesh search allows us to restrict our PubMed search to only find articles where the MeSH term is the main topic. In this way, articles in which the term and any selected subheadings are indexed as a major topic are displayed. For example, searching for "mechanical ventilation"[Majr] will exclude articles where this topic is covered to a lesser extent from the search results |

| 4 Since PubMed only contains abstracts of articles, not full texts, searching the entire article for words is not possible with the use of MeSH |

| 5 Sometimes, PubMed might fail to automatically match the exact MeSH term with the search |

| 6 Additionally, some readers might not be comfortable using Boolean operators and logic. Boolean operators are not recognized by all databases, and the availability of all operators in a database might also be questionable |

| 7 Moreover, databases also differ in their way of using syntax to enter a Boolean operator. For example, in Scopus, “NOT” is entered as “AND NOT.” |

| 8 Certain databases or search systems do not affect search results based on whether the terms are entered in uppercase or lowercase, but some engines like Google Scholar may require capitalized Boolean operators for proper functioning |

MeSH: Medical Subject Headings.

PubMed uses a hierarchical structure to display MeSH terms, which includes broader and narrower “descriptors.” The top level of the MeSH tree structure consists of 16 broad categories, which are not included in the MeSH data maintained and distributed by NLM. However, they can be used to search PubMed by using the search term “category.” For example, searching for “anatomy category” will retrieve all citations indexed under any MeSH descriptor in the “A” category (anatomy). When using a MeSH descriptor to search, PubMed automatically searches for narrower descriptors listed under it in the MeSH tree structures. For example, searching “musculoskeletal neoplasm non-Hodgkins lymphoma” will show the following two trees displayed with catalog numbers called tree numbers.

Each article citation is associated with a set of MeSH terms that describe the content of the citation. When conducting a literature search, using MeSH entry terms instead of keywords can result in a more focused search and make finding more relevant citations easier. For example, if we want to search “non-Hodgkins lymphoma”, finding the corresponding MeSH term can help us narrow down our results. The actual MeSH term for this topic is "non-Hodgkins lymphoma," which is further subdivided into additional categories. Our search term may fall under multiple categories, such as neoplasms and immune system diseases, as shown in the example below. Sometimes, users may begin their search with a specific MeSH term; for example, they may start with “non-Hodgkins lymphoma,” but then realize they really want information on “lymphoma” in general. By using the MeSH tree structure, users can easily access a complete search on any term within the hierarchical tree with a single MeSH term.

Google is the world’s most popular search engine, which stores all web pages in its index. The content and location (URL) of a page are described by its index entry. The process of identifying new or updated web pages is called “Crawling.” Google discovers web page locations (URLs) by many different means, including tracing links and reading sitemaps, among others. As Google crawls the web, it looks for new pages and indexes them when appropriate. A crawler is automated software that crawls (fetches) pages from the web and indexes them.

Google websites are evaluated for their medical reliability using the “Health On Net” or “HON” code. HON is a non-profit organization that promotes transparent and reliable health information dissemination online and acts as a quality marker for online health information. Regular assessments are carried out by medical experts with great vigilance to provide reliable information. The HON Foundation is a non-governmental organization officially related to the World Health Organization, which carries out certifications.

Google releases “search quality rating guidelines” periodically to ensure that search engines provide a diverse set of reliable, high-quality search results, presented in the most helpful order. Medical content falls under the category of “Your Money or Your Life” pages. This category includes all information that could potentially impact the future happiness, health, financial stability, or safety of the individual. Google is responsible for representing such information in the required indexing manner and has very high rating standards for such pages. When Google search quality raters evaluate a website, they are guided to look for expertise, authority, and trustworthiness, abbreviated as “EAT”. Their ratings are further augmented by the algorithm, and that is when the information is displayed in a responsible manner.

WRITING STRATEGIES TO AUGMENT THE SEARCHABILITY OF PUBLISHED MANUSCRIPTS

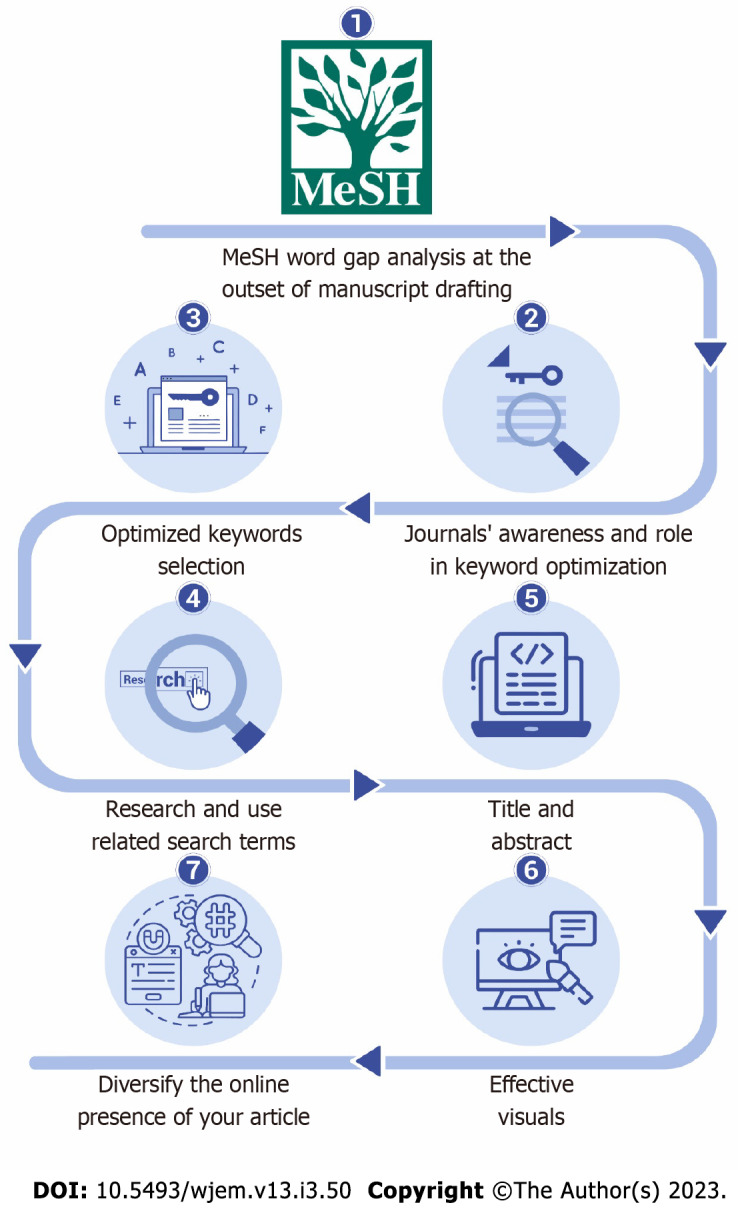

Here are some strategies to use when creating the manuscript with the intent of ranking well in the search engines and reaching the relevant readers, ultimately yielding a higher number of clicks, downloads, and citations:

MeSH keyword gap analysis during the manuscript drafting phase

To increase the chances of an article being found and cited, we suggest conducting a “MeSH keyword gap analysis” at the beginning of the manuscript writing process. This approach can potentially improve the retrievability and citation of the article. Currently, most authors only determine and mention keywords during the manuscript submission stage without putting detailed thought into it, which may result in missing out on strategic keywords.

Awareness of the journals and their role in keyword optimization

The wider reach of an article is not only important for the individual author but also beneficial for the journals. It helps the journals boost their impact factor, which is a scientometric measure of the frequency with which the average article in that journal has been cited in a particular year. The impact factor is used as a proxy for the importance or rank of a journal by calculating the number of times its articles are cited. Therefore, higher citation rates are beneficial for the ranking and credibility of journals, which implies they must focus on keyword optimization as well. The journals should hire professionals with an SEO background who are able to analyze the manuscripts for optimal use of keywords.

The list below complies the author’s instructions for keywords for selected journals. Except for Nature and the British Medical Journal (BMJ), none of the journals mention the importance of searchability, page ranking, or SEO in their author guidelines. It is evident that currently there is not much emphasis on the optimized use of keywords, their selection, or placement. The only exception is Nature publishing house, whose journal author guidelines state that “We ask authors to be aware of abstracting and indexing services when devising a title for the paper: providing one or two essential keywords within a title will be beneficial for web-search results”. They also suggest authors “choose keywords to maximize visibility in online searches as well as being suitable for indexing services”[4]. Meanwhile, the BMJ authors hub highlights that “it is essential for your paper to be correctly set up for discoverability, right from the start”, and provides six steps to make the work more visible and, as a result, more likely to be cited.

Author instructions for keywords within a few sampled high-impact factor journals

New England Journal of Medicine[5]: Three to 10 keywords or short phrases should be added to the bottom of the abstract page, which will assist us in indexing the article and which may be published with the abstract. Use terms from the MeSH in Index Medicus when possible.

PLOS One[6]: Add keywords to help expedite the processing of your manuscript (optional). You will not have an opportunity to make changes, so make sure to add concise, accurate keywords now.

Journal of Clinical Oncology[7]: Immediately after the abstract, provide a maximum of six keywords, using British spelling and avoiding general and plural terms and multiple concepts (avoid, for example, “and” and “of”). Be sparing with abbreviations; only those firmly established in the field may be eligible. These keywords will be used for indexing purposes.

Annals of Internal Medicine[8]: No mention or instructions on keywords.

BMJ[9]: “It is essential for your paper to be correctly set up for discoverability, right from the start”, and it provides some steps to make the work more visible and, as a result, more likely to be cited.

Keywords selection

Keywords play a crucial role in determining the discoverability of an article, leading to a chain reaction that includes clicking through, dwelling on, downloading, and ultimately citing the article. Citation is the critical element that generates the greatest impact factor. Keywords help readers find the best-suited article aligned with their research question and enhance the discoverability of research articles by ensuring that papers are substantially indexed by databases and search engines. It is important to select well-chosen keywords that best represent the article content and include various interchangeable terms and synonyms, be they in abbreviated or phrase form, making it easier for the manuscript to be easily identified and cited. The keywords of a manuscript should be selected by authors in such a manner that, if fed into search engines, accurate articles or the book’s contents are retrieved. However, keyword selection can be subjective and differ amongst authors, leading to difficulty retrieving similar articles by authors who are searching the relevant literature for citations in their future articles. If keywords are used incorrectly, it may affect the citation index of the article. Therefore, it is a good practice to do a dipstick test by searching for some keywords in PubMed and analyzing the search results that reflect similar papers as ours. It is also essential to integrate the keywords well in the title and abstract, as they may not yield the article in the results if the manuscript is paid and the full text is not visible, as the search is based on the title and abstract.

Keywords are essential components of a manuscript and are typically listed after the abstract. Most journals require authors to provide three to five keywords, although some may ask for up to eight. Therefore, it is recommended to have eight to ten relevant keywords prepared before submitting the manuscript. Unfortunately, keyword selection is often left as the last step during manuscript submission, which can lead to an inadequate selection.

The problem with keywords is that they are not standardized because authors generate them, which cannot be exact words as in contents and can vary from author to author. Thus, they may not retrieve similar articles from different authors who are searching for the same relevant literature. Conducting effective MeSH term research and drafting the manuscript based on MeSH terms can increase online traffic to the articles from the medical community more efficiently.

Research and use related search terms

Using synonyms and variations (related terms) of the keywords can help improve the discoverability of an article in the search results. For example, a reader looking for information on "heart attacks" may use search terms such as "heart attacks," "myocardial infarction," "myocardial infarctions," and so on. Therefore, when writing an article, it is important to embed various search terms that a researcher might use when searching for the relevant information that the article provides. Furthermore, it is important to pay attention to the terminologies that prevail in different geographies and how certain concepts and conditions are referred to based on medical, academic, and cultural backgrounds in that region. This information can be discovered through social listening and integrated into the manuscript. Although not yet widely practiced or emphasized, it is important to be mindful of MeSH keyword integration before and during manuscript writing. MeSH keywords may be searched, and all relevant words in the same hierarchy and those above and below it can be retrieved. It will help to identify keywords in the MeSH thesaurus that can be integrated throughout the article or abstract and title to perform well in the search engine algorithm.

Title and abstract

The ability to accurately highlight the core content of an article is crucial for crafting an impactful research paper title. A good title typically consists of a 10- to 12-word phrase with descriptive terms. Indexing agencies use the words used in the title to tag the article and make it easily discoverable. Making the title and abstract more action-oriented, concise, and less wordy can improve the search quality. Moreover, keywords provide an opportunity to tag the article with more relevant terms. Therefore, it is not a wise choice to use similar words or phrases both in the title and keywords.

The method of conducting a literature search differs from one person to another, which may result in different articles or a different number of articles despite looking for similar topics of interest. It is not always possible to predict how others will search the same literature. However, it is possible to elucidate how authors themselves might search the same literature. Authors should attempt to apply search strategies similar to those adopted by a reader or peer. Authors can utilize Google Trends to gain knowledge of internet search trends and discover the latest search trends for a particular word or phrase. Google Trends also helps in comparing search trends between different words and phrases, which helps authors choose the most relevant one for their title and keywords. From the perspective of the audience, study what types of topics the target audience would search for and that we would want our article to be found for and cited for.

Comparatively, an abstract is meant to provide a brief and accurate summary of the study, to aid the judgment of the reader of whether they should read the rest of the paper or not. A good understanding of the intent of the readers is foundational to this.

Effective visuals

Effective visuals help with readability and storytelling, greatly supporting learning, adding value, and keeping the reader engaged with the article. Vivid imagery is a much more effective and efficient method of communication than plain text. Articles that include images appear at the forefront of search engine results and have a viewership of up to 94% more often than those without images. Article visuals include tables, figures, clinical images, infographics, etc. Such elements can draw visual learners to our article. We can aid in the discovery process by making sure that our images and our site are optimized for Google Images. People who do not want to read an entire article but are still interested in the material can glance at these images and absorb valuable information without losing time. This helps engage and attract citations from readers who might have otherwise passed them by.

Images are proven to attract significantly more views compared to those without images, with a staggering 94% increase in views. Moreover, up to 60% of the population are visual learners, which means they prefer visual content over textual content. This is because the human brain is wired to process images faster than plain text, with images being processed 60000 times faster than text. Visuals are often available freely, even if an article is behind a paywall, and may even feature on Google Images, bringing in organic traffic to the article. It is important to carefully determine the figure legend and title by integrating the key MeSH terms. The average attention span is only around eight seconds, and visual content allows for valuable information to be distributed in a format that can be easily understood within this timeframe. In fact, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the human brain can process images in as little as 13 milliseconds. Good-quality visuals, developed with the support of professionals such as graphic designers, can lead to higher-quality traffic to the website by conveying valuable information in an engaging visual format. However, it is important to ensure that the visuals are original, as dealing with a copyright lawsuit can be an expensive affair.

Diversify the online visibility of the article

In addition to being an educational article intended for an academic and research audience, our manuscript will also be published as a webpage. A significant proportion of researchers and academicians search for articles not only on PubMed or MEDLINE but also on Google. Google attracts such traffic not only by analyzing words typed into its search box in a browser but also by using the words spoken to a mobile phone or assistant device and through “search engine auto-complete” features. This furthermore emphasizes the importance of the author’s mindful efforts towards ‘keywords and Google’s searchability of them when drafting the manuscript.

To increase the article’s online visibility, it is recommended to promote it through various channels, such as blogging, patient education, hospitals, and social media, along with linking the article. With educational content delivered in a conversational tone, our prospects get to know our target readers in a more personal way. Blogging is a particularly effective way to engage with readers, as more and more people are turning to blogs for information and sharing interesting articles on their social media networks. To leverage this behavior, it is crucial to cultivate the habit of blogging and maintain an active presence on all the relevant social media networks. Furthermore, some portals allow the authors to showcase unpublished, non-peer-reviewed articles that are ahead of print for the purpose of early clinical adoption and information sharing. However, it is only available for a limited time, mostly until publication. The SEO strategies and corresponding adapted medical writing strategies are enumerated in Table 2. Figure 2 showcases the proposed strategies for enhancing the searchability of manuscripts.

Table 2.

Search engine optimization strategies and corresponding adapted medical writing strategies

|

S. No.

|

SEO strategies

|

Corresponding medical writing strategies

|

| 1 | Backlinks to share link equity | 1 Citations of articles that enhance the credibility of articles |

| 2 Blog about the article on forums like WordPress and link to it | ||

| 3 Diversified media coverage, including social media articles linking the article, podcasts, and videos | ||

| 4 Use opportunities to target different web areas like YouTube, podcast portals, social media, blogging portals, news, etc. | ||

| 2 | Organizing information into categories, pages, and subpages on a website and linking them to each other is called site architecture or information architecture | Have impactful headings using keywords within the headings |

| 3 | The flatter the site’s structure is (requiring a lesser number of clicks to reach the desired information), the better its opportunity to rank well | MeSH terms and keywords search a manuscript by searching its abstract. Also, the abstract is commonly the only publicly available resource of an article, making it easily searchable for those on Google. Hence, incorporate critical keywords in the abstract of the article |

| 4 | The title tag is the most important on-page element to optimize for keywords, so the post has the best chance of ranking for a given keyword if that keyword appears at the beginning of the title tag (often the post headline). Also, make sure other posts linking to this one use this keyword as their link text (what SEOs call “anchor text”) | Incorporate keywords in the title of the article. Give it some thought and brainstorm with the writing team about what keywords a potential researcher will search for. Use alternative terms and broader terms throughout the text to describe the concepts the authors are writing about because too specific terms may not filter in the search method |

| 5 | An average user looks at two things before opening a webpage: headlines and meta descriptions. The latter is always displayed below the webpage title in Google search results. Search engines highlight keywords in the meta description, thus making it a genuine call-to-action booster—it encourages people to click the link and check out the content | Meta description corresponds to the abstract of the article, particularly the objective and the initial three to four sentences |

| 6 | Carefully-designed keyword strategies to make more impact on Google’s search engine algorithms | Research and integrate MeSH terms and keywords |

| 7 | Any time someone visits the website, we want them to have a positive user experience and engage with the site content | Lucid story-telling and point-to-point writing methodology |

| 8 | Visuals: when setting up pages, it is important to ensure that the pictures are always readable. “Alt” tags provide valuable details for the target audience. Google cannot understand images solely as image files | Explain the paper and integrate good-quality images and tables. Develop “at-a-glance” infographics covering key messages on the manuscript in a snapshot. Utilize digital designers, draw on easy digital tools like procreate, or hand draw and scan high-resolution images and convert them digitally to digitized images. Purchase editable vector images and templates. Determine figure legends judiciously, incorporating the keywords and MeSH terms, so their searchability is enhanced on Google Images |

| 9 | Internal linking is one of the SEO fundamentals that influence the dwell time of the target audience on the page | Generate the interest of the readers and direct them to various sections of the article by numbering the sections and structuring the topic well to enhance the time they spend on the page and article |

MeSH: Medical Subject Headings; SEO: Search engine optimization.

Figure 2.

Proposed strategies for enhancing the searchability of manuscripts—The art of being cited. MeSH: Medical Subject Headings.

LIMITATIONS

The discussion applies exclusively to the online readership, and we have naturally excluded from consideration those readers who read articles in journals in a hard copy format. The study assumed that clinicians would research information on their hand-held mobile devices and laptops in greater numbers, more so after the onset of the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic. Similarly, information stored in textbooks is not included in this discussion. To some extent, Google Books information is included.

CONCLUSION

The medical community primarily searches for articles on PubMed using keywords and MeSH terms. However, not many authors write their articles with searchability in mind. Ideally, an article that answers a specific research question with a large sample size and rigorous research methodology should appear on the first page of the search engine. In reality, it is dependent on the accurate use of keywords, and one has to sift through dozens of articles to find the most well-matched article.

To enhance the visibility of an article, medical authors and publishers use various strategies, such as “open access availability of articles” and tagging articles in blogs and multiple media formats, including “podcasts, audio, and video formats.” In addition to these existing practices, authors can improve the searchability of their articles by educating themselves about “Google keywords” and MeSH search and strategically embedding those words throughout the article. The point of this article is not to promote articles irrationally but to emphasize the importance of understanding the principles of search engine algorithms to enhance organic readership and uptake of the article.

We hope that following these best practices will make it easier for search engines to crawl, index, and understand the articles to rank them higher in the search results. Employing these strategies often involves making small modifications to the manuscript. When observed individually, these changes might seem like incremental improvements, but when combined with other optimizations, they could have a noticeable impact on the article’s performance in organic search results. The time has come that we understand and engage the search engine algorithms better, so they yield information in a desired and self-learning manner.

We acknowledge that the consumption of medical updates by healthcare professionals has become more digital in the past few years. Due to this, the updates we receive are also determined by a new ‘factor’ - the internet and its search engine which yields information based on the search words it is fed. Hence when drafting a manuscript this new factor must be considered along with technical accuracy of drafting research and grammatical flow. Hence not only the journal and the readers but also the “Internet” or the “cloud” is also a stakeholder in this process.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest for all authors.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: January 30, 2023

First decision: March 24, 2023

Article in press: April 18, 2023

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ng HY, China; Rasa HK, Turkey S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ju JL

Contributor Information

Pratishtha B Chaudhari, Manager Medical Operations, Amgen Asia, Amgen Asia Holding Ltd., Tokyo 1070062, Japan. pratishthabanga@gmail.com.

Akshat Banga, Sawai Man Singh Medical College, Jaipur 302004, India.

References

- 1.Kagan M. 100 Awesome Marketing Stats, Charts, & Graphs. HubSpot. October 20, 2016 Available from: https://blog.hubspot.com/blog/tabid/6307/bid/14416/100-awesome-marketing-stats-charts-graphs-data.aspx .

- 2.Dean B. We analyzed 4 million google search results. Here’s what we learnt about organic click-through rate. BACKLINKO. October 14, 2022] Available from: https://backlinko.com/google-ctr-stats .

- 3.Mondal H, Mondal S1, Mondal S2. How to Choose Title and Keywords for Manuscript According to Medical Subject Headings. Indian Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery . 2018;5:p 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nature Portfolio. How to publish your paper. Nature. Available from: https://www.nature.com/nature-portfolio/for-authors/publish .

- 5.Information for Authors. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:76. [Google Scholar]

- 6.PLOS One. Your step-by-step guide to the submission form. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/s/submit-now .

- 7.Clinical Oncology. Author Information Pack. April 9, 2023. Available from: https://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/623018?generatepdf=true .

- 8.Annals of Internal Medicine. February 22, 2023. Available from: www.acpjournals.org/pb-assets/pdf/AnnalsAuthorInfo-1656457118343.pdf .

- 9.BMJ Authors Hub. Writing for online visibility. Available from https://authors.bmj.com/before-you-submit/writing-for-online-visibility/