Abstract

Background

Most patients with malignant hyperthermia susceptibility diagnosed by the in vitro caffeine–halothane contracture test (CHCT) develop excessive force in response to halothane but not caffeine (halothane-hypersensitive). Hallmarks of halothane-hypersensitive patients include high incidence of musculoskeletal symptoms at rest and abnormal calcium events in muscle. By measuring sensitivity to halothane of myotubes and extending clinical observations and cell-level studies to a large group of patients, we reach new insights into the pathological mechanism of malignant hyperthermia susceptibility.

Methods

Patients with malignant hyperthermia susceptibility were classified into subgroups HH and HS (positive to halothane only and positive to both caffeine and halothane). The effects on [Ca2+]cyto of halothane concentrations between 0.5 and 3 % were measured in myotubes and compared with CHCT responses of muscle. A clinical index that summarises patient symptoms was determined for 67 patients, together with a calcium index summarising resting [Ca2+]cyto and spontaneous and electrically evoked Ca2+ events in their primary myotubes.

Results

Halothane-hypersensitive myotubes showed a higher response to halothane 0.5% than the caffeine-halothane hypersensitive myotubes (P<0.001), but a lower response to higher concentrations, comparable with that used in the CHCT (P=0.055). The HH group had a higher calcium index (P<0.001), but their clinical index was not significantly elevated vs the HS. Principal component analysis identified electrically evoked Ca2+ spikes and resting [Ca2+]cyto as the strongest variables for separation of subgroups.

Conclusions

Enhanced sensitivity to depolarisation and to halothane appear to be the primary, mutually reinforcing and phenotype-defining defects of halothane-hypersensitive patients with malignant hyperthermia susceptibility.

Keywords: calcium signalling, excitation–contraction coupling, malignant hyperthermia, skeletal muscle, volatile anaesthetics

Editor's key points.

-

•

Diagnosis of malignant hyperthermia susceptibility (MHS) is made by either genotypic identification of pathogenic variants in known susceptibility genes or phenotypic results from the invasive caffeine–halothane contracture test (CHCT) performed on a muscle biopsy.

-

•

Positive responses to the CHCT in malignant hyperthermia susceptible patients show two distinct phenotypes: contraction in response to halothane alone or in response to both halothane and caffeine.

-

•

The pathological basis for this difference was investigated in myotubes prepared from patient muscle biopsies, which identified enhanced susceptibility to depolarisation and halothane in the halothane hypersensitive subgroup compared with the halothane–caffeine subgroup.

-

•

Further study is required to identify the novel genes, genetic variants, or epigenetic changes that determine the halothane hypersensitivity phenotype.

Malignant hyperthermia susceptibility (MHS) presents as a skeletal muscle predisposition to hypermetabolic crises associated with uncontrolled increase in myoplasmic calcium, triggered by volatile anaesthetics and depolarising neuromuscular blocking agents.1 The diagnosis of MHS relies on either the presence of a pathogenic variant in RYR1, CACNA1S, or STAC3,1,2 or a positive result of in vitro caffeine–halothane contracture tests (CHCT3 or IVCT4), which measure the force developed by excised muscle alternatively exposed to caffeine and halothane. In our testing centre, most patients diagnosed as MHS via the CHCT are hyperreactive to halothane (a subgroup dubbed ‘HH’) but not caffeine, whereas other MHS patients (‘HS’) are hyper-responsive to both agonists. Interestingly, there were no patients hypersensitive to caffeine only in our cohort.

Our primary aim was to test whether the defining pathophysiological mechanisms are fundamentally different between HH and HS patients. The hypothesis is based on the distinct mechanisms of action of the drugs used in the contracture tests: caffeine enhances the sensitivity of ryanodine receptor 1 (RyR1) to activation by calcium,5 and halothane increases the sensitivity of RyR1 to activation by voltage.6

We previously tested the same hypothesis by comparing the clinical features of HH and HS patients who underwent CHCT in our clinic, and calcium signalling in patient-derived myotubes.7,8 The abnormalities in calcium homeostasis and signalling proved greater in myotubes derived from HH than from HS patients. This observation was surprising, because the CHCT response to halothane was much greater in HS patients. Thus, HH patients suffer a ‘non-classical’ MHS condition, which features a greater cell-level functional alteration despite lower CHCT force values. Here, we attempt to resolve this conundrum, evaluating the response of myotubes derived from MHS patients to various halothane concentrations. The study revealed a critical difference between subgroups, which provides additional insights into the mechanistic differences between the MHS patient subgroups.

Methods

Human subjects

Of the patients included in this study, 88% were referred to our clinic for presenting adverse episodes of anaesthesia, family history of malignant hyperthermia, or both; the others were included for presenting recurrent exercise- or heat-induced rhabdomyolysis, or idiopathic elevation of serum creatine kinase. The study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board of Toronto General Hospital, Toronto, Canada. Most comparisons comprised just the larger group. In some cases, we distinguish those as Fx and the rest as not Fx.

Genetics and bioinformatics

RNA was isolated from blood or muscle biopsy; cDNA synthesis and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of RYR1 and CACNA1S transcripts were performed as described.7,9 Variants were validated using ClinVar.10

Clinical index

Five symptoms or signs (s) were collected and quantified for each patient: weakness/fatigability (s1), muscle cramps/twitches (s2), heat and exercise sensitivity/rhabdomyolysis (s3), elevated serum creatine kinase (s4), and muscle histopathology (s5). Each was assigned severity scores of 0–2. The index is the equal-weight average of these components,7 rescaled to between 0 and 10.

Caffeine–halothane contracture test

Increases in force in response to caffeine and halothane (FC and FH) were measured on fresh biopsies of Gracilis muscle that met viability criteria.3.

Muscle bundles were exposed to incremental [caffeine] (0.5–32 mM), or halothane 3 %. The threshold responses for a positive diagnosis were FC≥0.3 g in caffeine 2 mM and FH≥0.7 g. Patients were diagnosed as ‘malignant hyperthermia negative’ (MHN) if the force was below the threshold for both agonists, and ‘malignant hyperthermia susceptible’ (MHS) if the threshold was exceeded for at least one of the exposures.

Primary muscle cell cultures

Myoblasts were derived from biopsies and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2/95% air with growth medium7 consisting of DMEM/F12 (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), fetal bovine serum 10% (FBS; Foundation™; Gemini Bioproducts, West Sacramento, CA, USA), and antibiotic/antimycotic 1% (Gemini Bioproducts). Myotube differentiation was induced with horse serum 2.5% (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) at 70–80% confluence. Myotubes were used 5–10 days into the differentiation process.

Solutions

Myotube Krebs (mM): 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2.6 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2 10 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 5.6 glucose. Stock solutions of halothane (MilliporeSigma) in Krebs were prepared as described.11 Halothane concentrations in stocks were estimated by ultraviolet spectral analysis.12 Solutions were adjusted to pH 7.3.

Cell-level calcium measurements

Cytosolic [Ca2+], [Ca2+]cyto, and Ca2+ events were measured in myotubes loaded with indo-1 AM or fluo-4 AM (ThermoFisher) as described.7 Experiments were performed at 20–22°C.

Calcium index

Four cell-level Ca2+ features (x1–x4) were measured in cultures from 67 patients: x1 – resting [Ca2+]cyto, x2 – fraction of myotubes having spontaneous Ca2+ events, x3 – fraction of myotubes having Ca2+ waves after electrical stimulation, and x4 – fraction of myotubes having cell-wide Ca2+ spikes. Their separations from normalcy (s1–s4) were summarised by their average and rescaled to the 0–10 range.7

Halothane assays in myotubes

Halothane (0.5, 1, 2, and 3 % in Krebs buffer) was applied to myotubes loaded with indo-1 AM, separately in three cultures for each patient and halothane concentration. The response was quantified by the maximum [Ca2+]cyto attained during the response.

Statistical analysis

Distributions are illustrated with plots including mean (dashed), median (solid), and 25th and 75th percentiles (box bounds). Distributions satisfying normality and equality of deviation were compared parametrically, and otherwise by their rank-sum (Mann–Whitney U-test). A principal component analysis (PCA) of myotube-level variables7 was modified to equalise the contributions of all variables by first normalising variables by their standard deviation.

Results

Caffeine–halothane contracture test

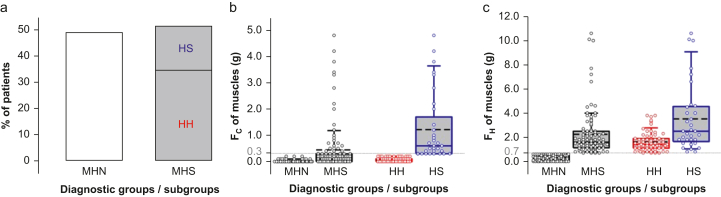

We recruited 195 patients undergoing CHCT for this study; their characteristics and CHCT status are shown in Supplement 1. Of these, 171 (88%), identified as Fx, had had one of more episodes of malignant hyperthermia themselves or in their family. Based on CHCT results, patients were classified as MHN and MHS, comprising 49% and 51% of the cohort, respectively (Fig. 1a). Median ages were 36 yr for females and 38 yr for males; a lower female/male ratio was observed in the MHS group (Supplement 2). The MHS patients were divided into diagnostic subgroups: 33 were hyperresponsive to both halothane and caffeine (HS), 67 to halothane only (HH), and none to caffeine only (HC). The distribution of the contracture force to caffeine 2 mM (FC) or halothane 3 vol% (FH) is shown in Fig. 1b and c. In the MHS group, the FH was significantly greater in HS compared with HH muscle; this difference existed independently of the referral reason, although with lower significance for not Fx patients (Supplement 3). According to these measures, HS have the most severe phenotype.

Fig 1.

Classification of patients by caffeine–halothane contracture test in a cohort of 195 patients. (a) Percentages of patients in each malignant hyperthermia (MH) diagnostic group (95 MHN, 100 MHS), and subgroups (67 HH, 33 HS). (b) Contractile force in response to caffeine 2 mM (FC) in biopsied muscle strips. (c) Contractile force in response to halothane 3 vol% (FH) in biopsied muscle strips. The threshold responses for a positive diagnosis were FC≥0.3 g, and FH≥0.7 g (dotted lines). Patients were diagnosed as ‘malignant hyperthermia negative’ (MHN) if the force was below the threshold for both agonists, and ‘malignant hyperthermia susceptible’ (MHS) if at least one of the exposures exceeded the threshold. Box plots show the quartiles, the 5th and 95th percentiles (whiskers), median (dissecting solid line), and mean (dissecting dashed line). Symbols plot averages in three muscle strips per patient. Distributions satisfying normality and equality of deviation were compared by t-test, otherwise by Mann–Whitney rank-sum test.

Genetic analysis

A complete screening of RYR1/CACNA1S genes was performed on 79 MHS patients. Variants of unknown significance (VUS) were found in 26 patients (nine HH and 17 HS). Pathogenic mutations G341R RYR1 and T2206M RYR1 were found in two HS individuals (Supplement 4).

Responses to halothane

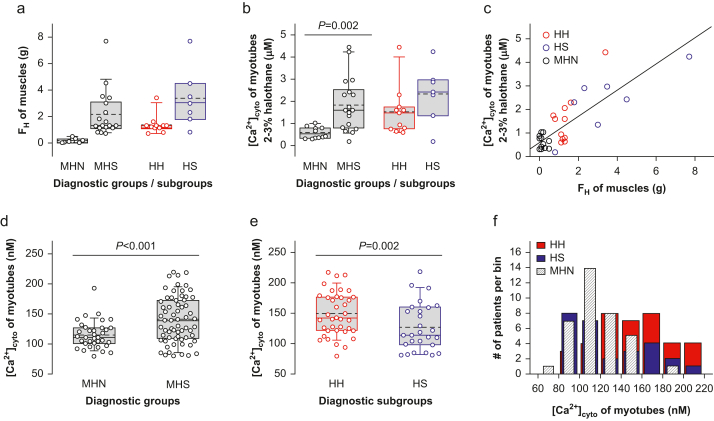

We compared the FH response to halothane of muscles from 29 Fx patients and the [Ca2+]cyto response of their derived myotubes. As with the larger cohort, FH was greater in the HS than in the HH subgroup of MHS muscle (Fig. 2a).

Fig 2.

Responses to halothane and resting [Ca2+]cyto. (a) Contractile force in response to halothane 3 vol% (FH) in biopsied muscle strips from 29 patients with personal or family history of malignant hyperthermia (11 MHN, 18 MHS; 11 HH, 7 HS). Symbols plot averages in three muscle strips per patient. (b) Maximum [Ca2+]cyto in response to halothane 2–3 vol% in myotubes derived from patients in (a). (c) Responses to halothane of muscle strips vs average responses in myotubes derived from the same patients (data from panels a and b). The first-order regression line is represented (r=0.82; N=29; P of no correlation <0.001). (d and e) Resting [Ca2+]cyto in myotubes for major diagnostic groups (36 MHN, 65 MHS), and MHS subgroups (38 HH, 27 HS). For panels (b), (d), and (e), the symbols represent data from 10 to 30 myotubes. (f) Distribution of resting [Ca2+]cyto in myotubes for each patient studied.

The response of myotubes derived from the same patients was quantified by the maximum [Ca2+]cyto reached in multiple concentrations of halothane. Owing to the limited number of primary cells available, it was not possible to test all concentrations in cultures from the same patient. Therefore, to gain sensitivity and power, for the comparison we grouped together the responses to ‘high’ concentrations (halothane 2 or 3 %), comparable with 3 % in the CHCT (Fig. 2b). The average maximum [Ca2+]cyto induced by halothane was higher in MHS than in MHN myotubes (P=0.002), with no significant difference between HH and HS (P=0.176). FH was highly positively correlated with the amplitude of the calcium transient in myotubes (r=0.82; Fig. 2c).

Resting cytosolic calcium of MHS myotubes

The average resting [Ca2+]cyto of myotubes from MHS patients was significantly higher than from MHN patients (Fig. 2d). It was also higher in HH than in HS myotubes (Fig. 2e). Myotubes from not Fx patients did not show a significant difference between subgroups (Supplement 3), and although [Ca2+]cyto in the HH subgroup was far above normal, in the HS subgroup it was not significantly different from MHN myotubes (Fig. 2f).

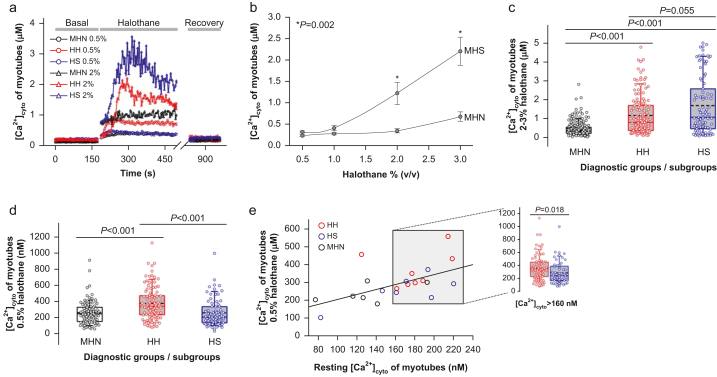

Dependence of responses on halothane concentration

We exposed myotube cultures to halothane in the concentration range of tests (3 % for CHCT, 0.5–3 % for IVCT). Myotubes derived from MHS patients had a greater response than MHN myotubes at all concentrations tested (Fig. 3a and b), with statistical significance at 2 % and 3 % halothane. At 2–3 %, HS myotubes from Fx patients showed on average a greater response than HH myotubes (P=0.055; Fig. 3c), in agreement with the observation of a greater FH in muscle exposed to halothane 3 %. At 0.5 %, the response was instead greater in the HH subgroup (Fig. 3d).

Fig 3.

Concentration dependence of myotube responses to halothane. (a) Representative traces [Ca2+]cyto (t) of responses of single patient-derived myotubes to halothane 0.5 % (circles) and halothane 2 % (triangles). (b) Maximum [Ca2+]cyto response of myotubes vs concentration of halothane. Symbols plot mean (standard error of the mean [sem]) for patients (variable numbers of patients, N, were included, depending on concentration: 6–10 MHN, 10–18 MHS). Significant differences between diagnostic groups are shown with an asterisk. (c, d) Maximum [Ca2+]cyto reached at 0.5 vol% and at 2–3 vol% halothane in myotubes derived from patients with personal or family history of malignant hyperthermia. Box plots represent the distribution of single myotube maxima (cells measured at the two concentrations were 96–179 MHN, 101–140 HH, 75–91 HS). (e) Maximum [Ca2+]cyto in halothane 0.5 % vs the corresponding resting value averaged for individual patients, with first order regression line (r=0.58; N=21; P of no correlation=0.005). The grey box highlights symbols for patients with average resting [Ca2+]cyto values >160 nM. The inset shows maximum [Ca2+]cyto in the response to halothane 0.5 % for each myotube (83 HH, 53 HS) from patients included in the box. MHN, malignant hyperthermia negative; MHS, malignant hyperthermia susceptible.

Halothane sensitivity versus resting cytosolic calcium

Having found in HH myotubes a higher resting [Ca2+]cyto and a greater response to low halothane concentrations than in HS myotubes, we evaluated whether the latter could be attributable to the elevated [Ca2+]cyto (as observed for RyR1 channels in bilayers13). The hypothesis was tested by analysing the relationship between response to halothane and resting [Ca2+]cyto, irrespective of diagnostic status, which showed a weak correlation (r=0.58; Fig. 3e). As a complementary test, comparison of responses to low halothane between HH and HS was limited to myotubes that had elevated [Ca2+]cyto (defined as >160 nM), thus removing [Ca2+]cyto as cause of the differences. As illustrated in the inset, a significant difference remained.

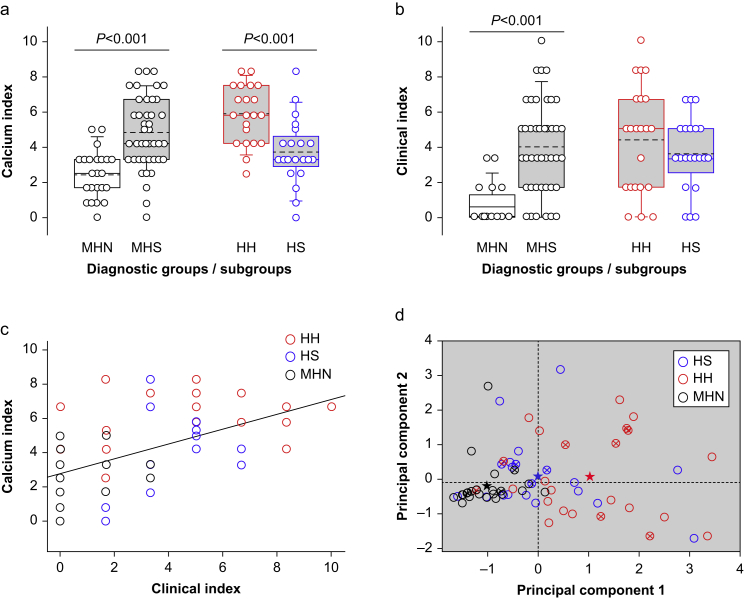

Cell-level events

Abnormal Ca2+ events were observed at a higher frequency in myotubes derived from MHS patients (Table 1). Spontaneous events were more frequent in the HH than in the HS subgroup (P=0.022); however, Ca2+-evoked events did not significantly differ. The calcium index, combining all cell-level variables, was higher in the MHS than in the MHN group (Fig 4a), and in the HH compared with the HS subgroup.

Table 1.

Cell-level measurements and clinical index. Values listed are means (standard error of the mean [sem]) over patients in the same diagnostic group or subgroup. Cell-level measurements are means of 10–40 myotubes per culture. Clinical index means (see Methods for calculation) are listed for the 67 individual subjects with complete determination of calcium index. Distributions satisfying normality and equality of deviation were compared using t-test; otherwise, by Mann–Whitney rank sum test.

| Variable | MHN | P-value MHN vs HH | HH | P-value HH vs HS | HS | P-value MHN vs HS | MHS | P-value MHN vs MHS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resting [Ca2+]cyto (nM) | x1 | 118.4 (5.1) | 0.005∗ | 148.0 (7.7) | 0.011∗ | 120.1 (6.9) | 0.829 | 137.1 (5.6) | 0.055 |

| Spontaneous Ca2+ events (%) | x2 | 2.8 (1.0) | <0.001∗ | 28.7 (6.2) | 0.022∗ | 14.3 (5.4) | 0.174 | 21.7 (4.2) | 0.002∗ |

| Evoked Ca2+ waves (%) | x3 | 1.9 (1.1) | 0.048∗ | 5.9 (1.6) | 0.862 | 5.6 (1.9) | 0.030∗ | 5.7 (1.2) | 0.020∗ |

| Evoked Ca2+ spikes (%) | x4 | 5.4 (1.5) | <0.001∗ | 32.8 (4.0) | 0.073 | 21.7 (3.0) | <0.001∗ | 27.4 (2.6) | <0.001∗ |

| Calcium index | ∑xi / 4 | 2.5 (0.3) | <0.001∗ | 5.9 (0.3) | <0.001∗ | 3.7 (0.4) | 0.011∗ | 4.8 (0.3) | <0.001∗ |

| Clinical index | see methods | 0.5 (0.2) | <0.001∗ | 4.4 (0.6) | 0.305 | 3.6 (0.4) | <0.001∗ | 3.9 (0.4) | <0.001∗ |

| n | 24 | 22 | 21 | 43 |

∗, statistically significant; MHN, malignant hyperthermia negative; MHS, malignant hyperthermia susceptible.

Fig 4.

Quantitative indexes of disease in patients and derived myotubes. (a) Calcium index of malignant hyperthermia diagnostic groups and MHS subgroups. Symbols represent individual values for 24 MHN and 43 MHS (22 HH, 21 HS). The values of variables used to derive the calcium index are listed in Table 1. (b) Clinical index by groups and MHS subgroups. The variables used to derive the clinical index are described in Methods. (c) Relationship between calcium index and clinical index. r=0.56; N=67; P of no correlation <0.001. Distributions satisfying normality and equality of deviation were compared by t-test, otherwise by Mann–Whitney rank-sum test. (d) Plots of the two first principal components of the four variables measured in myotubes (listed in Table 1). Symbols represent PC1 and PC2 values from individual patients from (a). Stars plot group means. Note that they differ by the abscissa (PC1), but only minimally by the ordinate (PC2). Crossed circle symbols represent not Fx patients.

The significant difference observed between subgroups was independent of the reason for CHCT (Supplement 3). No significant differences associated with patient age or sex were observed in the calcium index or in the clinical index (Supplement 2).

Clinical index

A significantly elevated clinical index was found in the 67 MHS patients with calcium index completed (Fig 4b). The average index was not significantly different between subgroups (Table 1 and Supplement 3). The calcium and clinical indexes had a weak positive correlation (r=0.56; Fig 4c).

Principal component analysis

A cross-plot of the first two principal components of the cell-level measurements (Fig 4d) shows that group averages (stars) were well separated, and aligned along the PC1 axis, which indicates that the combination of variables in PC1 contributes the most to the separation of groups. The normal phenotype locations clustered in the lower left quadrant. The HH values were visibly shifted to high values of PC1, but neither these nor the HS values showed clustering. The PCA eigenvectors are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Principal component analysis of cell-level data. Eigenvectors, in columns, are the arrays of four coefficients or weights used to generate the principal components as linear combinations of the variables listed in the first column. The rank (1–4) of a principal component is determined by its variance (eigenvalues). Note the large value of eigenvalue 1 and the comparable values of coefficients in principal component 1.

| Eigenvectors |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Resting [Ca2+]cyto | 0.41 | 0.18 | –0.86 | –0.26 |

| Spontaneous Ca2+ events | 0.59 | –0.30 | 0.41 | –0.62 |

| Evoked Ca2+ waves | 0.16 | 0.94 | 0.30 | –0.10 |

| Evoked Ca2+ spikes | 0.67 | –0.07 | 0.09 | 0.73 |

| Eigenvalues | 1.71 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.38 |

Discussion

The goal of the study was to reveal the pathophysiologic differences between muscle hyperreactive to both agonists of the CHCT (caffeine and halothane; HS) and those hyperreactive to halothane but not caffeine (HH). More specifically, we sought to understand why the HH subgroup, which responds with less force to both agonists, has more severe cell-level dysfunction. Here and in previous work7,14 we probed primary myotubes to evaluate the pathophysiology of individual patients. Although this approach is reasonable given the inheritable nature of the disease, and was generally upheld by observations made on cultured cells,15, 16, 17 it was never validated in a cohort of patients with heterogeneous genetic backgrounds. For this purpose, we compared the response to halothane of muscle biopsies with that of myotubes cultured from the same biopsies. The significant positive correlation found shows that the abnormal response is retained in the primary cultures.

This observation is evidence of the genetically determined nature of these conditions. It is important to note that variants in RYR1 and CACNA1S were present in only 32% of the MHS patients, leaving room for future investigations, including the search for novel genes and genetic variants18,19 or epigenetic factors33 that may contribute to the heritable HH phenotype.

As a group, resting [Ca2+]cyto in primary myotubes from MHS patients was elevated ∼20%, with high significance. The HH myotubes, with [Ca2+]cyto greater than normal by 30 nM, were the main contributors to the difference; in contrast, [Ca2+]cyto of HS myotubes was nearly the same as in MHN myotubes. This disparity adds to the conundrum noted earlier: HH muscles respond less forcefully to agonists, whereas their derived myotubes exhibit a more severe phenotype than HS myotubes.7 Matching the contracture testing of adult muscles, the responses of myotubes to high halothane concentrations were greater in the HS subgroup. However, at the lowest concentration tested, the response of HH myotubes was the greatest. This ‘crossing’ of the dose-dependence curves implies that HH myotubes respond to halothane with lower intensity but greater sensitivity, consistent with the hypothesis that the mechanisms underlying the HH and HS phenotypes are fundamentally distinct.

The differences in responses to caffeine between the MHS subgroups provide an additional clue. Caffeine and Ca2+ affect RyRs as synergic agonists,21 which destabilise the closed state by binding to channel sites that are structurally close and interact allosterically.22,23 Although Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) does not contribute to physiological Ca2+ release in normal mammalian muscle,5,24 an exaggerated response to caffeine suggests its operation in muscle from HS patients.

Halothane instead is believed to enhance CaV1.1-mediated voltage sensitivity of Ca2+ release.6 A plausible interpretation of the observations is that halothane concentrations sub-threshold for HS cells activate HH cells because of their primarily heightened sensitivity to voltage. In contrast, HS cells' enhanced sensitivity to Ca2+ enables CICR, potentiating the response to halothane (at higher concentrations) beyond that of HH cells.

The correlation between resting [Ca2+]cyto and the response to halothane 0.5 vol% suggests that the hypersensitivity to halothane might be a consequence of the abnormally high [Ca2+]cyto. The comparison of HH and HS myotubes selected for having a similarly elevated [Ca2+]cyto, intended to detect a primary difference in halothane sensitivity, found a small but significant difference in favour of the HH myotubes. The result is thus consistent with a primary difference in halothane sensitivity; its smaller size when the differences in [Ca2+]cyto are removed, indicates that the hypersensitivity is enhanced by the higher [Ca2+]cyto in HH myotubes.

Although MHS is referred to as a susceptibility (rather than an overt disease), patients often present with pathologic skeletal muscle signs and symptoms: elevated creatine kinase, myalgia, rhabdomyolysis, muscle cramps, fatigability, and they can experience life-threatening malignant hyperthermia-like reactions to heat, exercise, or both.20,25,26 Their clinical index,7 which summarises quantitatively these features, was significantly increased and correlated with the corresponding calcium index. The correlation implies that disease severity is generally explained by the cell-level alterations that we detected. Instead, the clinical index was minimally higher in the HH vs the HS subgroup. That myotube-level Ca2+ signalling differences between subgroups seldom translate to clinically demonstrable variation indicates that the disease phenotype, although partially explicable by the variables measured in cultured cells, is critically affected by variables and processes not fully captured by measurements made in myotubes. Other studies in progress underscore the range of variables (protein expression, metabolic use of glucose, etc.27,28) involved in the pathophysiology of MHS.

PCA applied to the cell-level variables showed that PC1 contains much of the relevant information for separating MHS from MHN, and HH from HS. The high values of coefficients 1 (weight of resting [Ca2+]cyto) and 2 (weight of frequency of local spontaneous Ca2+ events) reported in a previous study,7 implied a strong association of the HH condition with these variables (x1 and x2). The present study updates the PC1 with more data and better normalisation to yield a new large value of coefficient 4, which bestows relevance to x4, the frequency of Ca2+ spikes after electrical stimuli, both for the MHS phenotype and for the separation of HH and HS subgroups.

This finding has mechanistic implications; delayed spikes – fast, spatially homogeneous, and often repetitive – are similar to triggered events in cardiac myocytes.29 As is the case for cardiac triggered activity, their properties imply activation by delayed, endogenous action potentials.

That MHS muscle is more sensitive to membrane depolarisation has been shown using various experimental models and approaches.30, 31, 32 The emergence of electrically triggered activity in myotubes of the HH subgroup adds evidence of the augmented voltage sensitivity of its myofibres.

These findings recall the detailed observations of Zullo and colleagues6 on myofibres of an MHS mouse model, which revealed two features that mutually reinforce: a shift to lower voltage of activation of Ca2+ release and an increased sensitivity to halothane, which further increases the sensitivity to voltage. The combined increases in sensitivity to halothane and sensitivity to depolarisation observed in the HH myotubes are evidence of a similar reinforcing interaction, which in this case separates the HH from other MHS phenotypes.

In conclusion, the present results are consistent with interpretation of susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia as the consequence of two primary defects that alter the two main mechanisms of activation of Ca2+ release for excitation–contraction coupling. Muscles of individuals in the HS diagnostic subgroup have an alteration that mainly enhances the sensitivity of RyR1 channels to Ca2+, with the possible involvement of CICR. The primary defect in the HH subgroup is instead an enhanced sensitivity to depolarisation, combined with increased sensitivity to halothane. These defects alter Ca2+ homeostasis more severely, thus explaining their greater disruption of function at the cellular level.

Authors’ contributions

Study conception: LF

Experiment design: LF, ER, SR

Design and performance of cell studies: LF

Development of electrophysiological and imaging techniques: CM

Performance of clinical studies and analyses: NK, CAIM, SR

Performance of caffeine–halothane contracture test and genetic analyses: NK, SR

Data acquisition and analysis: LF, ER, SR

Figure and table preparation: LF

Writing original draft: LF

Review and editing: LF, NK, CM, CAIM, ERT, SR, ER

All authors approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR 071381 to SR and ER); US National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01 AR 072602 to ER); US National Center for Research Resources (S1055024707 to ER and others).

Handling editor: Hugh C Hemmings Jr

Footnotes

This article is accompanied by an editorial: What is malignant hyperthermia susceptibility? by Phil M. Hopkins, Br J Anaesth 2023:131:5–8, doi:10.1016/j.bja.2023.04.014

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2023.01.008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Rosenberg H., Pollock N., Schiemann A., Bulger T., Stowell K. Malignant hyperthermia: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:93. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0310-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riazi S., Kraeva N., Hopkins P.M. Malignant hyperthermia in the post-genomics era: new perspectives on an old concept. Anesthesiology. 2018;128:168–180. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larach M.G. Standardization of the caffeine halothane muscle contracture test. North American Malignant Hyperthermia Group. Anesth Analg. 1989;69:511–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopkins P.M., Rüffert H., Snoeck M.M., et al. European Malignant Hyperthermia Group guidelines for investigation of malignant hyperthermia susceptibility. Br J Anaesth. 2015;115:531–539. doi: 10.1093/bja/aev225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endo M. Calcium-induced calcium release in skeletal muscle. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1153–1176. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00040.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zullo A., Textor M., Elischer P., et al. Voltage modulates halothane-triggered Ca2+ release in malignant hyperthermia-susceptible muscle. J Gen Physiol. 2018;150:111–125. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201711864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Figueroa L., Kraeva N., Manno C., Toro S., Ríos E., Riazi S. Abnormal calcium signalling and the caffeine-halothane contracture test. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dirksen R.T., Allen P.D., Lopez J.R. Understanding malignant hyperthermia: each move forward opens our eyes to the distance left to travel. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:8–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraeva N., Riazi S., Loke J., et al. Ryanodine receptor type 1 gene mutations found in the Canadian malignant hyperthermia population. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58:504–513. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9494-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landrum M.J., Lee J.M., Benson M., et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1062–D1067. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valtcheva R., Stephanova E., Jordanova A., Pankov R., Altankov G., Lalchev Z. Effect of halothane on lung carcinoma cells A 549. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;146:191–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanck TJJ, Thompson M. Measurement of halothane by ultraviolet spectroscopy. Anesth Analg. 1980;59:481–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diaz-Sylvester P.L., Porta M., Copello J.A. Halothane modulation of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptors: dependence on Ca2+, Mg2+, and ATP. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C1103–C1112. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.90642.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibarra Moreno C.A., Kraeva N., Zvaritch E., et al. A multi-dimensional analysis of genotype–phenotype discordance in malignant hyperthermia susceptibility. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:995–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Girard T., Treves S., Censier K., Mueller C.R., Zorzato F., Urwyler A. Phenotyping malignant hyperthermia susceptibility by measuring halothane-induced changes in myoplasmic calcium concentration in cultured human skeletal muscle cells. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:571–579. doi: 10.1093/bja/aef237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wehner M., Rueffert H., Koenig F., Olthoff D. Calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum is facilitated in human myotubes derived from carriers of the ryanodine receptor type 1 mutations Ile2182Phe and Gly2375Ala. Genet Test. 2003;7:203–211. doi: 10.1089/109065703322537214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi M., Mukaida K., Migita T., Hamada H., Kawamoto M., Yuge O. Analysis of human cultured myotubes responses mediated by ryanodine receptor 1. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39:252–261. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1103900216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bjorksten A.R., Gillies R.L., Hockey B.M., Du Sart D. Sequencing of genes involved in the movement of calcium across human skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum: continuing the search for genes associated with malignant hyperthermia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2016;44:762–768. doi: 10.1177/0310057X1604400625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller D.M., Daly C., Aboelsaod E.M., et al. Genetic epidemiology of malignant hyperthermia in the UK. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:944–952. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmins M.A., Rosenberg H., Larach M.G., Sterling C., Kraeva N., Riazi S. Malignant hyperthermia testing in probands without adverse anesthetic reaction. Anesthesiology. 2015;123:548–556. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.López J.R., Linares N., Pessah I.N., Allen P.D. Enhanced response to caffeine and 4-chloro-m-cresol in malignant hyperthermia-susceptible muscle is related in part to chronically elevated resting [Ca2+]i. Am J Physiol-Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C606–C612. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00297.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chirasani V.R., Pasek D.A., Meissner G. Structural and functional interactions between the Ca2+-, ATP-, and caffeine-binding sites of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor (RyR1) J Biol Chem. 2021;297 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murayama T., Ogawa H., Kurebayashi N., Ohno S., Horie M., Sakurai T. A tryptophan residue in the caffeine-binding site of the ryanodine receptor regulates Ca2+ sensitivity. Commun Biol. 2018;1:98. doi: 10.1038/s42003-018-0103-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figueroa L., Shkryl V.M., Zhou J., et al. Synthetic localized calcium transients directly probe signalling mechanisms in skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 2012;590:1389–1411. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.225854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snoeck M., Treves S., Molenaar J.P., Kamsteeg E.J., Jungbluth H., Voermans N.C. Human Stress Syndrome” and the expanding spectrum of RYR1-related myopathies. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2016;74:85–87. doi: 10.1007/s12013-015-0704-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang H.J., Lee C.S., Yee R.S.Z., et al. Adaptive thermogenesis enhances the life-threatening response to heat in mice with an Ryr1 mutation. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5099. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18865-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tammineni E., Kraeva N., Figueroa N., et al. Intracellular calcium leak lowers glucose storage in human muscle, promoting hyperglycemia and diabetes. eLife. 2020;9 doi: 10.7554/eLife.53999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tammineni E., Figueroa L., Manno C., et al. Muscle calcium stress cleaves junctophilin1, unleashing a gene regulatory program predicted to correct glucose dysregulation. e-Life. 2023;12:e78874. doi: 10.7554/eLife.78874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen M.R. A short, biased history of triggered activity. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2009;50:170–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donaldson S.K., Gallant E.M., Huetteman D.A. Skeletal muscle excitation-contraction coupling: I. Transverse tubule control of peeled fiber Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in normal and malignant hyperthermic muscles. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol. 1989;414:15–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00585621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andronache Z., Hamilton S.L., Dirksen R.T., Melzer W. A retrograde signal from RyR1 alters DHP receptor inactivation and limits window Ca2+ release in muscle fibers of Y522S RyR1 knock-in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:4531–4536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812661106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Avila G., Dirksen R.T. Functional effects of central core disease mutations in the cytoplasmic region of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:277–290. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray K., Laitano O., Sheikh L., et al. Epigenetic responses to exertional heat stroke in mice: a potential link to long term Ca2+ dysregulation in skeletal muscle. FASEB J. 2018;32:590–614. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.