Abstract

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells have demonstrated promising efficacy, particularly in hematologic malignancies. A challenge for CAR T-cells in solid tumors is the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME), characterized by high levels of multiple inhibitory factors, including TGFβ. We report results from a first-in-human phase 1 trial of castration-resistant prostate cancer-directed CAR T-cells armored with a dominant-negative TGFβ receptor (NCT03089203). Primary endpoints were safety and feasibility; secondary objectives included assessing CAR T-cell distribution, bioactivity, and disease response. All pre-specified endpoints were met. Eighteen patients enrolled and thirteen subjects received therapy across four dose levels. Five of 13 patients developed grade ≥2 cytokine release syndrome (CRS), including one patient who experienced a marked clonal CAR T-cell expansion, >98% reduction in PSA, and death following grade 4 CRS with concurrent sepsis. Acute increases in inflammatory cytokines correlated with manageable high-grade CRS events. Three additional patients achieved PSA declines of ≥30%, with CAR T-cell failure accompanied by upregulation of multiple TME-localized inhibitory molecules following adoptive cell transfer. CAR T-cell kinetics revealed expansion in the blood and tumor trafficking. Thus, clinical application of TGFβ-resistant CAR T-cells is feasible and generally safe. Future studies should use superior multi-pronged approaches against the TME to improve outcomes.

Introduction

Many advanced prostate cancer patients treated with androgen deprivation therapy experience relapse with inevitable progression to lethal metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) involving antibodies against programmed cell death 1/programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD1/PD-L1) or cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) results in clinically meaningful responses in a significant fraction of patients across several different cancer types. However, clinical outcomes for mCRPC remain poor due to de novo resistance to ICB as well as other treatments1,2, and novel therapeutic approaches are needed. Accordingly, adoptive immunotherapy with chimeric antigen receptor-modified (CAR) T-cells has resulted in durable remissions in a variety of hematologic malignancies3–7, but the utility of CAR T-cells for solid tumor indications such as mCRPC is still being explored. The prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is highly expressed in mCRPC and represents a promising tumor-associated antigen for immune therapy8–13. However, a primary challenge to CAR T-cell therapy in mCRPC is the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME). In particular, the TME of mCRPC is characterized by markedly elevated levels of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), which may limit the therapeutic potential of engineered T-cells14–19. Based on preclinical evidence that inhibiting TGFβ signaling via overexpression of a dominant-negative TGFβRII20 (TGFβRDN) or CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of TGFBR221 in CAR T-cells significantly enhances tumor control, we aimed to develop TGFβ-resistant CAR T-cells that could be advanced to clinical trials for mCRPC.

Here we report the preclinical development and results from a phase 1 trial of PSMA CAR-T cells optimally engineered with a TGFβRDN to block TGFβ signaling for enhancement of antitumor immunity in patients with mCRPC. In addition to safety and feasibility, we investigated peripheral blood CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell expansion, T-cell bioactivity, tumor trafficking, and conducted comprehensive profiling of the TME to identify determinants of antitumor potency and resistance.

Results

Comparison of TGFβRII signaling blockade strategies

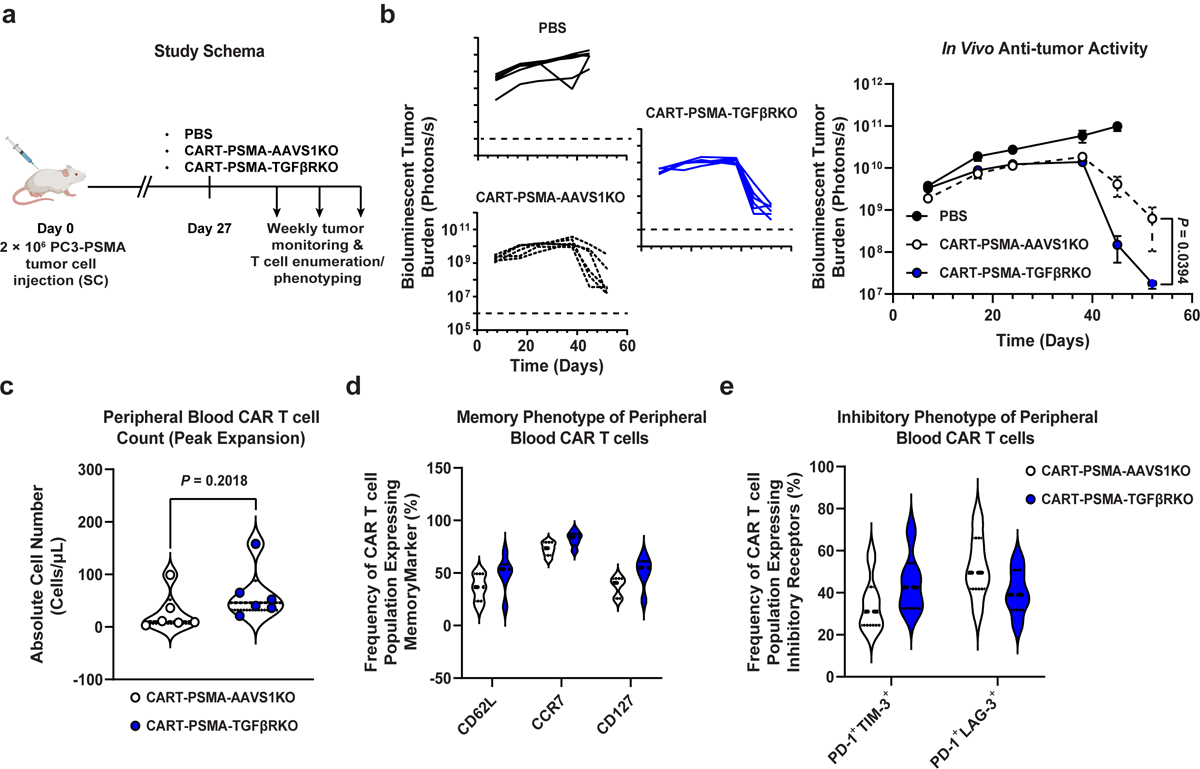

We and others have reported that TGFβRDN enhances in vivo proliferation, cytokine secretion, memory differentiation, resistance to exhaustion, persistence, and induction of tumor eradication by antigen-specific T-cells22–26, including anti-PSMA CAR T-cells20. However, because forced expression of a TGFβRDN, but not genetic deletion of the endogenous TGFβRII has been associated with T-cell hyperproliferation and cellular transformation27, we proceeded with determining whether blocking TGFβ signaling by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated TGFBR2 editing is a viable alternative strategy to improve CAR T-cell efficacy in vivo, while preserving the above-mentioned features of successful adoptive immunotherapy. PC3 prostate tumor-bearing mice were treated with a single dose of either CART-PSMA-TGFβRKO cells, CART-PSMA-AAVS1KO cells or saline alone (Extended Data Fig. 1a, Methods). Saline-treated mice exhibited a rapid increase in bioluminescent signal, necessitating euthanasia approximately 52 days after tumor inoculation. In contrast, animals treated with control CART-PSMA cells exhibited decreased tumor burden, which was significantly enhanced by TGFBR2 knockout (Extended Data Fig. 1b). The marginal therapeutic benefit of TGFBR2 editing in augmenting tumor elimination was not associated with enhanced peripheral blood CAR T-cell proliferative capacity (Extended Data Fig. 1c), increased frequencies of early memory T-cells (Extended Data Fig. 1d), or decreased proportions of CAR T-cells co-expressing multiple inhibitory receptors (Extended Data Fig. 1e).

We next directly compared the 2 different strategies to block TGFβRII signaling. Genetic ablation of TGFBR2 in CAR T-cells (Extended Data Fig. 2a) might result in a much stronger abrogation of TGFβ-mediated suppression compared to forced expression of TGFβRDN, because the latter approach leaves a functional TGFβRII that can induce some level of TGFβ signaling28,29. Even though both strategies effectively blocked TGFβ signaling through SMAD2/3 proteins (Extended Data Fig. 2b), the TGFβRDN induced a significantly higher level of PSMA CAR T-cell proliferation in a “stress test” involving serial restimulation with TGFβ-secreting PC3 cells (Extended Data Fig. 2c). Neither TGFβRII knockout (TGFβRKO) nor TGFβRDN expression affected the cytolytic capacity of PSMA-targeted CAR T-cells (Extended Data Fig. 2d), while both strategies resulted in increased effector cytokine production relative to stimulated CAR T-cells alone (Extended Data Fig. 2e).

Clinical trial design and patient characteristics

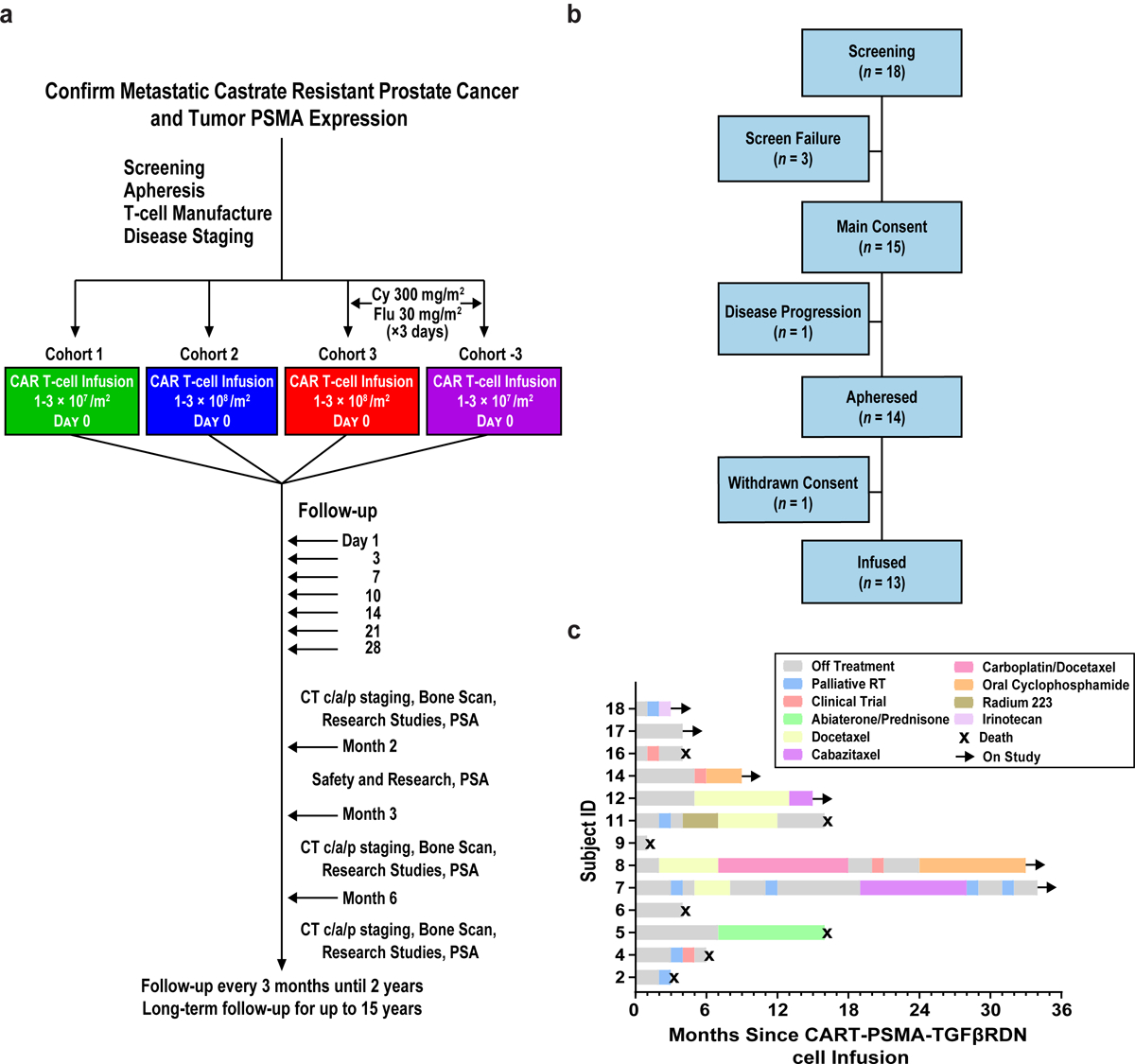

In considering the frequency of positivity and high level of PSMA expression in mCRPC8,12,30,31, the recent clinical de-risking of the TGFβRDN25, the preclinical efficacy of the CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN product20 and prior success conducting CAR T-cell clinical studies with highly potent antitumor activity3–5,32, the University of Pennsylvania opened a phase 1 single-institution trial (NCT03089203) to evaluate the safety and feasibility of lentivirally transduced PSMA-TGFβRDN autologous CAR T-cells administered with and without lymphodepletion (LD) in a 3 + 3 dose escalation design (Fig. 1a). Eighteen patients were enrolled between March 20, 2017 and October 28, 2020. Seventeen patients underwent prostate cancer tissue biopsy for confirmation of ≥10% PSMA expression by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (n = 1 screen failure due to prior therapy). Of these subjects, 14 patients proceeded to apheresis and cell collection (n = 1 inadequate PSMA expression <10%, n = 2 patients withdrew due to rapid disease progression). Thirteen of 14 subjects who underwent apheresis proceeded with planned protocol therapy (n = 1 withdrew due to patient preference) (Fig. 1b). The time on study for each subject and the duration of follow-up off study (survival beyond progression or initiation of other therapy) are indicated in Fig. 1c.

Figure 1. CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN protocol design and consort diagram.

(a) Protocol schema for screening, apheresis, T-cell manufacturing, treatment with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells and follow-up. (b) Consort diagram indicating the number of patients screened, enrolled in the study, and infused with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells. (c) Swimmer’s plot describing time on study for each subject, subsequent therapies and present status. Black arrows indicate ongoing survival and black X’s denote patient death.

Clinical and disease characteristics for the thirteen patients infused with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The median age at study entry was 70 years (interquartile range, IQR 57–72), with minimum of 57 to a maximum of 72 years, and the median serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was 36.6 ng/mL (IQR 11.9–284.5). Eight patients (61.5%) presented with stage 4 disease at initial prostate cancer diagnosis, 13 patients (100%) received prior androgen receptor signaling inhibitor (ARSI) therapy, and 6 patients (46.2%) received prior docetaxel chemotherapy. The median number of prior therapies for CRPC was 2, with a range of 1 to 8 previous treatment lines. The cutoff for data analysis was March 15, 2021.

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics

| Subject ID | Age (Years) | Clinical Stage at Diagnosis | PSA at Time of Treatment (ng/mL) | Gleason Score | Sites of Metastatic Disease | Time from Diagnosis to Metastatic Disease (Months) | Time from Metastatic Disease to CRPC (Months) | Prior Treatment History |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 2 | 55 | IV | 237.8 | n/a | Bo, Bl | 0a | 12 | c†,d,e,f,g†,i |

| Patient 4 | 50 | IV | 7.6 | 9 | LN | 0a | 12 | c†,d,e,f,g† |

| Patient 5 | 71 | IV | 10.47 | 7 | LN | 108 | 46 | c,d,e |

| Patient 6 | 72 | IV | 41.6 | 9 | LN | 24 | 30 | b,c,d,e |

| Patient 7 | 73 | IV | 331.2 | 9 | Bo | 3 | 15 | b,d,e,g |

| Patient 8 | 64 | III | 132.3 | 7 | Bl | 48 | 36 | c,d,e,g,i |

| Patient 9 | 71 | III | 36.6 | 7 | Bo, LN | 96 | 18 | b,c,e,h,i |

| Patient 11 | 72 | IV | 15.5 | 7 | Bo, LN | 0a | 144 | b,e,h |

| Patient 12 | 67 | III | 13.4 | 7 | LN | 12 | 24 | b,c,d,e |

| Patient 14 | 70 | II | 14.6 | 7 | Bo | 18 | 28 | b,c,d,e |

| Patient 16 | 58 | IV | 1683 | n/a | Bo, LN | 0a | 11 | e,g† |

| Patient 17 | 56 | III | 5.2 | 9 | Bo | 17 | 20 | b,c†,e |

| Patient 18 | 73 | IV | 973 | 9 | Li | 0a | 22 | d,e,g†,i |

n/a = not applicable

Sites of Metastatic Disease: Bl, bladder; Bo, bone; LN, lymph nodes; Li, liver

Patient presented with metastatic disease at time of diagnosis

Prior Treatment History:

prostatectomy;

radiation therapy;

radiation therapy with palliative intent;

first generation anti-androgen;

novel androgen receptor signaling inhibitor;

bone supportive care;

docetaxel;

docetaxel in the setting of mCSPC;

Sipuleucel-T;

other

Note: In the ‘other’ category, Patient 9 received experimental seviteronel/dexamethasone therapy.

Manufacturing and characteristics of CAR T-cell products

CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells were manufactured in all patients who underwent apheresis (n = 14; manufacturing success rate of 100%). Of these, 2 patients (14.3%) required remanufacture from the original apheresis material and 2 patients (14.3%) required repeat apheresis and manufacture prior to obtaining the final cell infusion product. The median time from manufacturing initiation to final product was 10 days (range 9–52), and the median time from manufacturing initiation to cell infusion was 35 days (range 20–111).

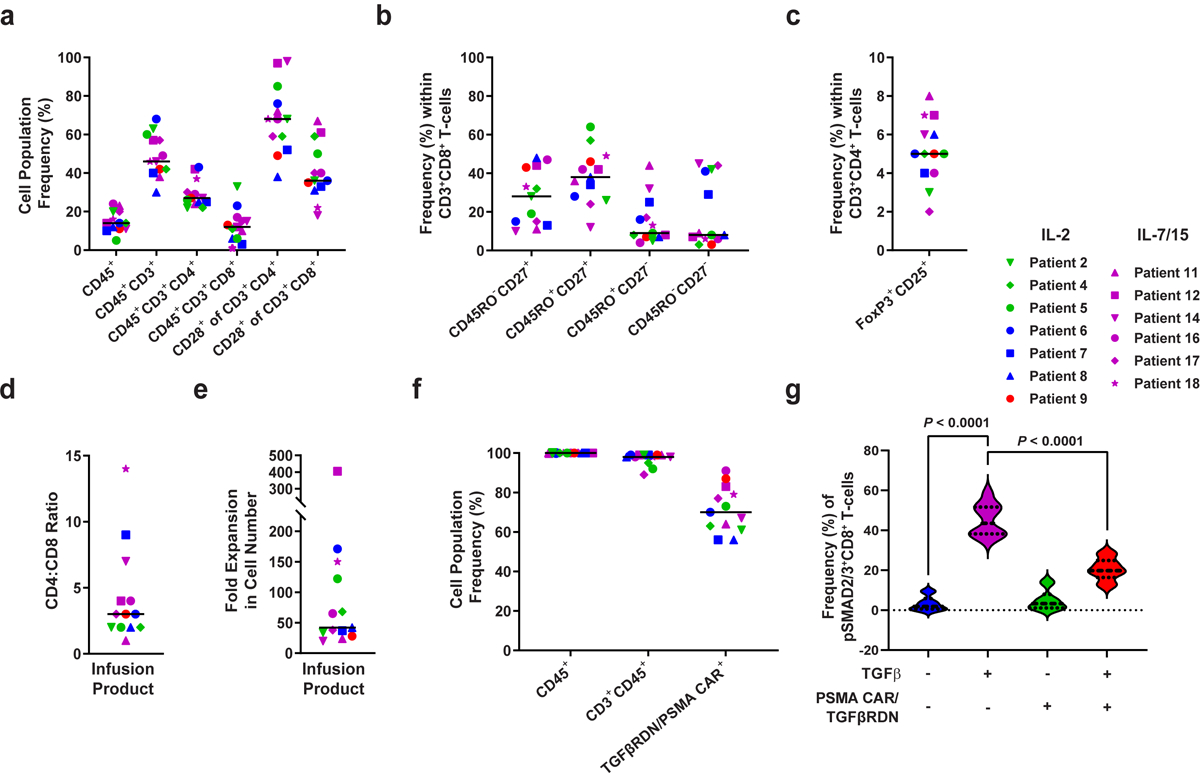

We analyzed starting apheresis material and final CAR T-cell infusion products using multiparameter flow cytometry (Extended Data Fig. 3; representative flow cytometric gating strategy, Supplementary Fig. 1). The composition of apheresis material used for clinical manufacture exhibited donor variability, which was distributed across the study cohorts. The median frequency of CD45+CD3+ T-lymphocytes was 46%. The T-cell fraction was heterogeneous and included both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets, each containing wide-ranging levels of CD28, a primary costimulatory receptor and surrogate for responsiveness and self-renewal capacity (reviewed in33) (Extended Data Fig. 3a). CD8+ T-cells from apheresis products contained a mix of naïve-like (CD27+CD45RO−; median 28%, range 10–48%), central memory (CD27+CD45RO+; median 38%, range 12–64%), effector memory (CD27−CD45RO+; median 9%, range 4–44%), and effector T-cell (CD27−CD45RO−; median 8%, range 3–45%) phenotypes (Extended Data Fig. 3b). In addition, the starting material for all thirteen subjects contained 5% of regulatory T-cells (TREG), as defined by a CD25+FoxP3+CD4+ T-cell phenotype in resting apheresis samples (Extended Data Fig. 3c). Infusion products from all patients displayed a median CD4/CD8 ratio of 3 (Extended Data Fig. 3d), a median 42-fold expansion in cell number (Extended Data Fig. 3e) and a median of 98% CD45+CD3+ T-cells (Extended Data Fig. 3f). The frequencies of anti-PSMA CAR-expressing cells in the infusion products ranged from 56–91% (median 70%, Extended Data Fig. 3f). We confirmed that the TGFβRDN potently inhibited TGFβ signaling in CAR T-cell infusion products, which was demonstrated by decreased levels of SMAD2/3 in TGFβRDN+ compared to TGFβRDN− cells following stimulation with recombinant human TGFβ (Extended Data Fig. 3g).

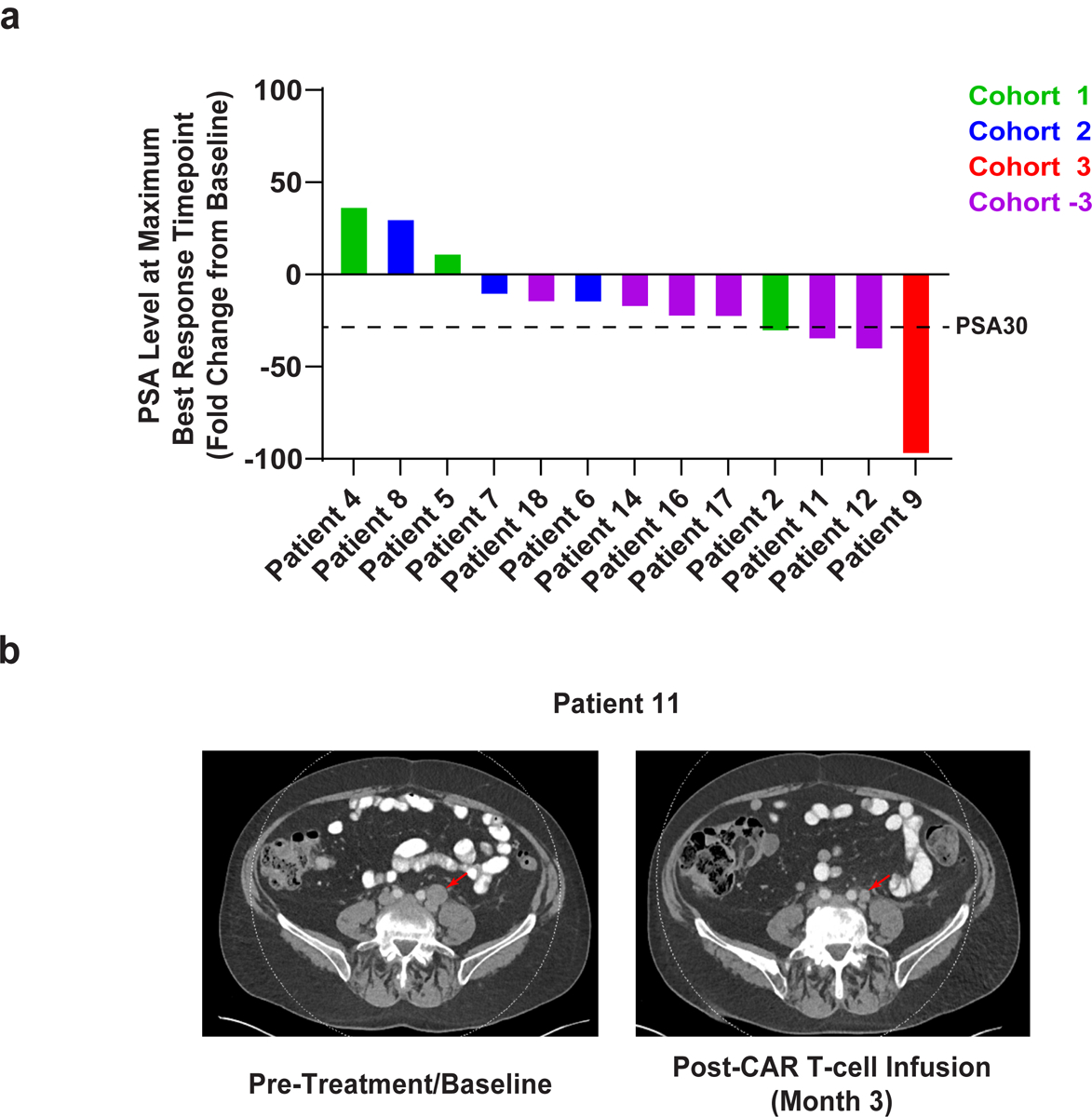

Figure 3. Pathological and radiologic evaluations after CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion.

(a) Waterfall plot depicting the maximum fold change in serum PSA levels (PSA30 marked with dashed line) after CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion. Individual patients are represented by vertical bars on the x-axis. (b) Computed tomography scans demonstrating tumor regression in Patient 11 following administration of an autologous CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN product. Radiologic studies were obtained before therapy and 3 months after adoptive transfer of CAR T-cells. The tumor site is indicated by a red arrow.

Infused CAR T-cells were tolerated and generally safe

All patients received protocol-specified dosing of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells. Treatment-related serious adverse events (AE) are summarized in Extended Data Tables 1 and 2. In Cohort 1, 3 subjects received a single dose of 1–3 × 107/m2 cells without LD. No treatment-related grade ≥3 AEs or cases of CRS were observed. In Cohort 2, 3 subjects received a single dose of 1–3 × 108/m2 cells without LD. Two subjects developed grade 3 CRS within 12 hours of infusion, one of whom developed a concurrent grade 3 encephalopathy event, which clinically improved with tocilizumab and corticosteroid administration. As per contemporaneous protocol definition, this neurologic AE was not deemed to be CAR T-cell-related neurotoxicity but would meet clinical criteria for neurotoxicity/immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) according to a subsequent protocol amendment and revised toxicity definitions34. CRS and neurologic toxicity fully resolved within 24-hours following tocilizumab and corticosteroid therapy. In Cohort 3, one patient (Patient 9) received 1–3 × 108/m2 CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells following cyclophosphamide and fludarabine (Cy/Flu) LD. This patient developed grade 4 CRS manifesting as hypoxic respiratory failure, capillary leak syndrome, and vasopressor-dependent hypotension. Despite resolution of CRS, the patient ultimately died 30 days following infusion in the setting of multimodal immunosuppression, enterococcal sepsis, and resultant multi-organ dysfunction.

Following this occurrence of dose-limiting toxicity (DLT), 6 additional patients were treated under an amended protocol in Cohort −3 at a modified, de-escalated dose-level of 1–3 × 107/m2 cells following Cy/Flu LD. One subject developed grade 2 CRS, which fully resolved with anti-IL-6R therapy. Another patient developed grade 2 CRS lasting 5 days, which self-resolved without immunosuppressive intervention. A third subject developed delayed, recurrent episodes of grade 1 CRS up to 1-month post-infusion, which were reversed with supportive measures. Three additional subjects developed grade 1 CRS, which resolved with supportive measures. Non-CRS- related grade ≥3 AEs were not observed in Cohort −3.

CAR T-cell expansion, persistence, and cytokine analysis

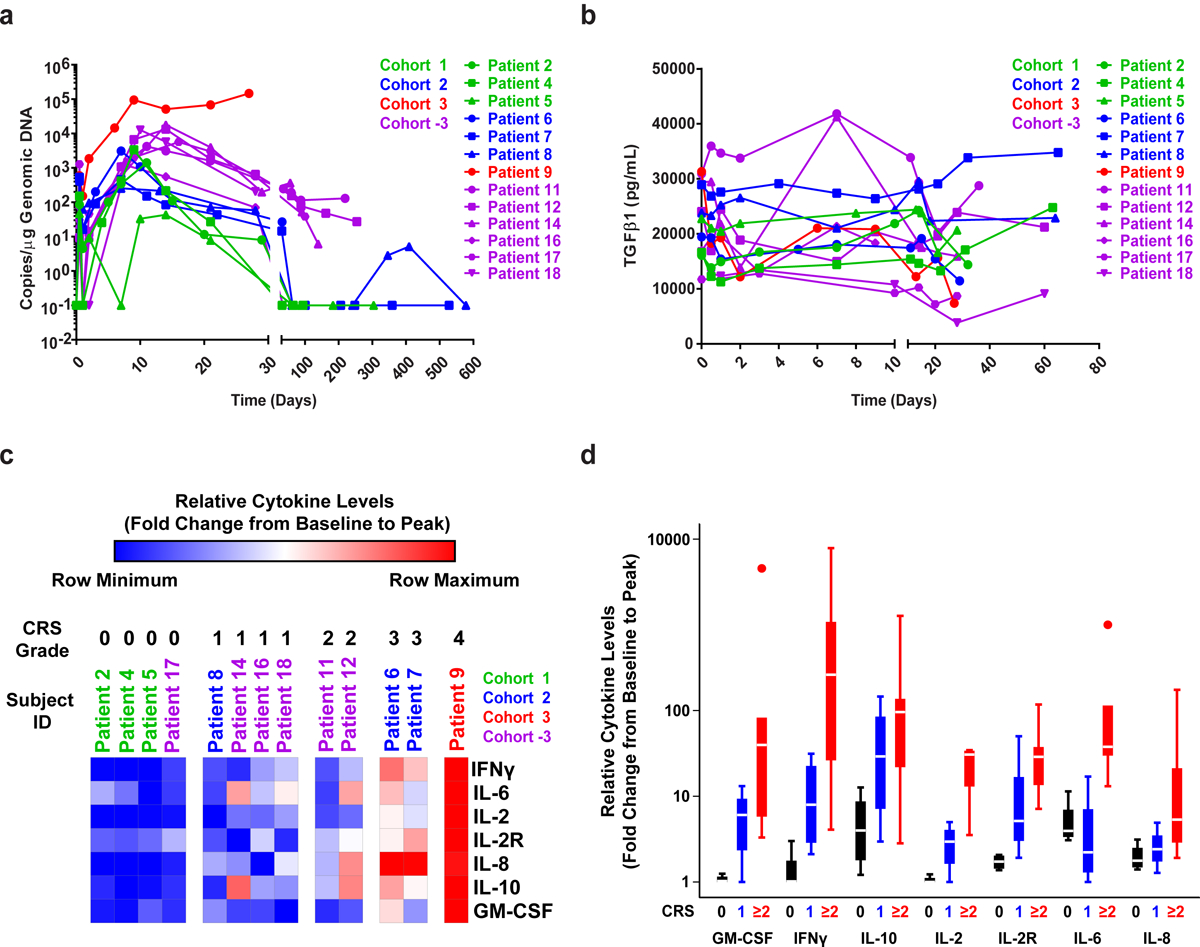

The post-infusion kinetics of peripheral CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell expansion and persistence are displayed in Fig. 2a. An initial expansion phase was observed, peaking within the first 14 days, followed by a decline in CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell levels. The magnitude of peak expansion generally increased with dose escalation, as patients in Cohort 2 with 1–3 × 108/m2 infused cells had a higher average peak CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN level than patients in Cohort 1 with 1–3 × 107/m2 infused cells. In addition, the use of Cy/Flu LD clearly increased CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN CMAX, as five out of six patients in Cohort −3 had higher peak levels than any of the patients in Cohorts 1 and 2, and two patients in Cohort −3 (Patients 11 and 12) maintained measurable persistence in peripheral blood at >200 days post-infusion (Fig. 2a). The only patient treated in Cohort 3 (Patient 9), who received 1–3 × 108/m2 CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells following Cy/Flu LD, demonstrated a very large expansion of the CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN product to a first peak of 94,368 copies/microgram at day 9 and a second peak of 147,019 copies/microgram at day 27 post-infusion (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2. Engraftment of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells and cytokine elaboration in the peripheral blood.

(a) CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell engraftment in the peripheral blood by qPCR detecting CAR-specific sequences in genomic DNA. CAR T-cell pharmacokinetics over the first month for all subjects and beyond that time point for evaluable patients are shown. (b) Changes in serum TGFβ1 levels in the peripheral blood of each patient infused with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells are depicted over time. (c) Heat maps (grouped by individual patients) and (d) boxplots (grouped by CRS grade: 0, n = 4; 1, n = 4; 2, n = 2; 3, n = 2; 4, n = 2) depicting the fold changes in pro-inflammatory cytokine production from baseline/pre-CAR T-cell infusion to the peak of CAR T-cell expansion are shown. Box plots indicate the range of the central 50% of the data, with a central line marking the median value. Whiskers extend from each box to show the range of the remaining data, with dots placed past the line edges to indicate outliers.

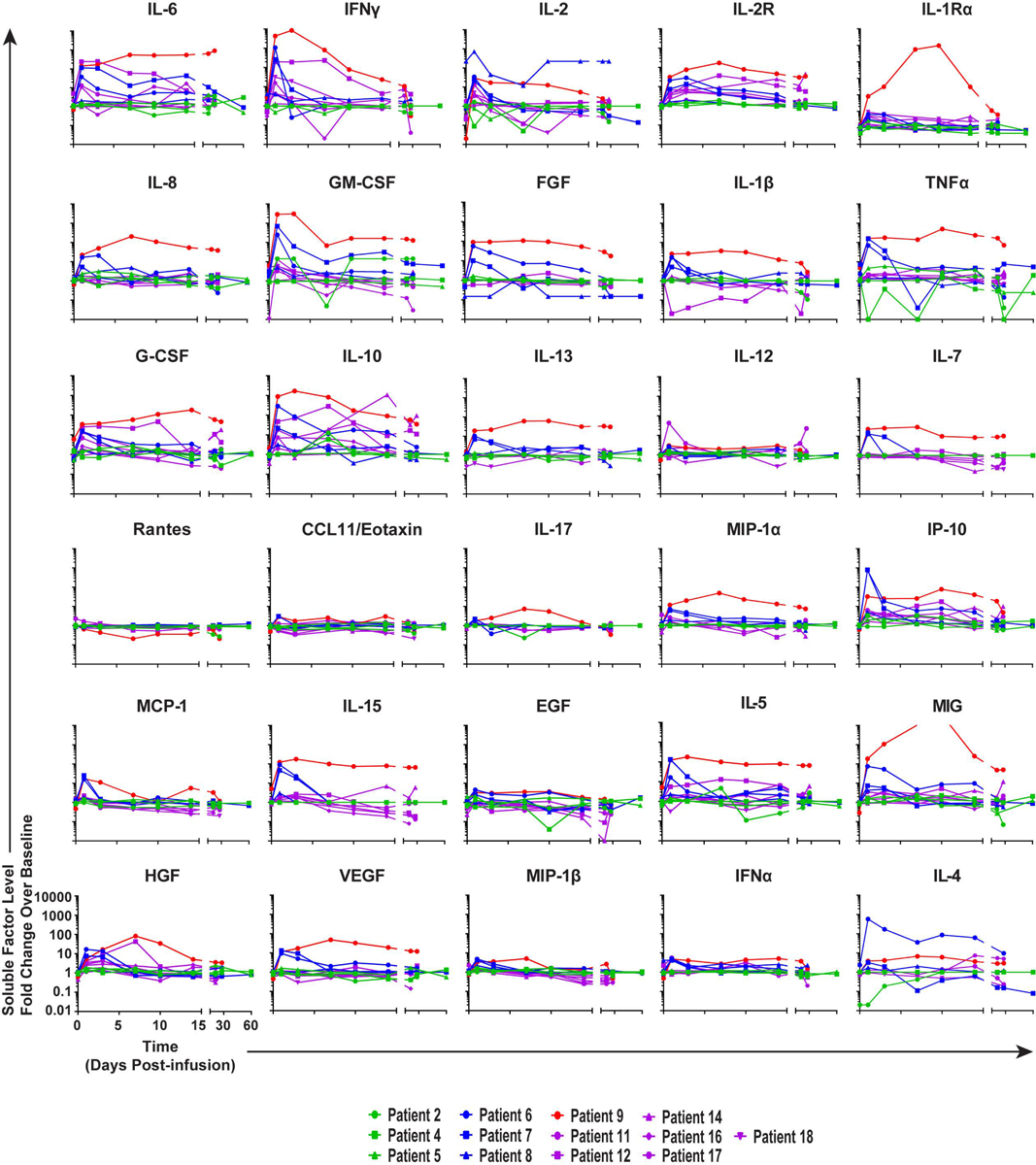

Patient 9, who also experienced the largest in vivo CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell expansion, demonstrated a decline of serum TGFβ from 30,000 pg/ml at baseline to under 10,000 pg/ml at day 27 post-treatment (Fig. 2b). The kinetics of serum cytokines for thirty different analytes are displayed in Extended Data Fig. 4. The relationship between CRS grade and maximum fold change from day 0 pre-infusion to post-infusion of 6 cytokines (IFNγ, IL-6, IL-2, IL-8, IL-10, GM-CSF) and soluble IL-2 receptor was also examined (Fig. 2c–d). Higher grade CRS was associated with a larger fold change in levels of these analytes from pre-infusion to post-infusion time points. Interestingly, there was marked increase in IL-8 in two patients who received CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells but did not experience a robust response despite development of grade 3 CRS. It is possible that the high levels of IL-8 could have had a dominant negative effect on the cellular response and that lack of lymphodepletion/cellular clearance may perhaps explain the increased IL-835,36.

Clinical anti-tumor efficacy

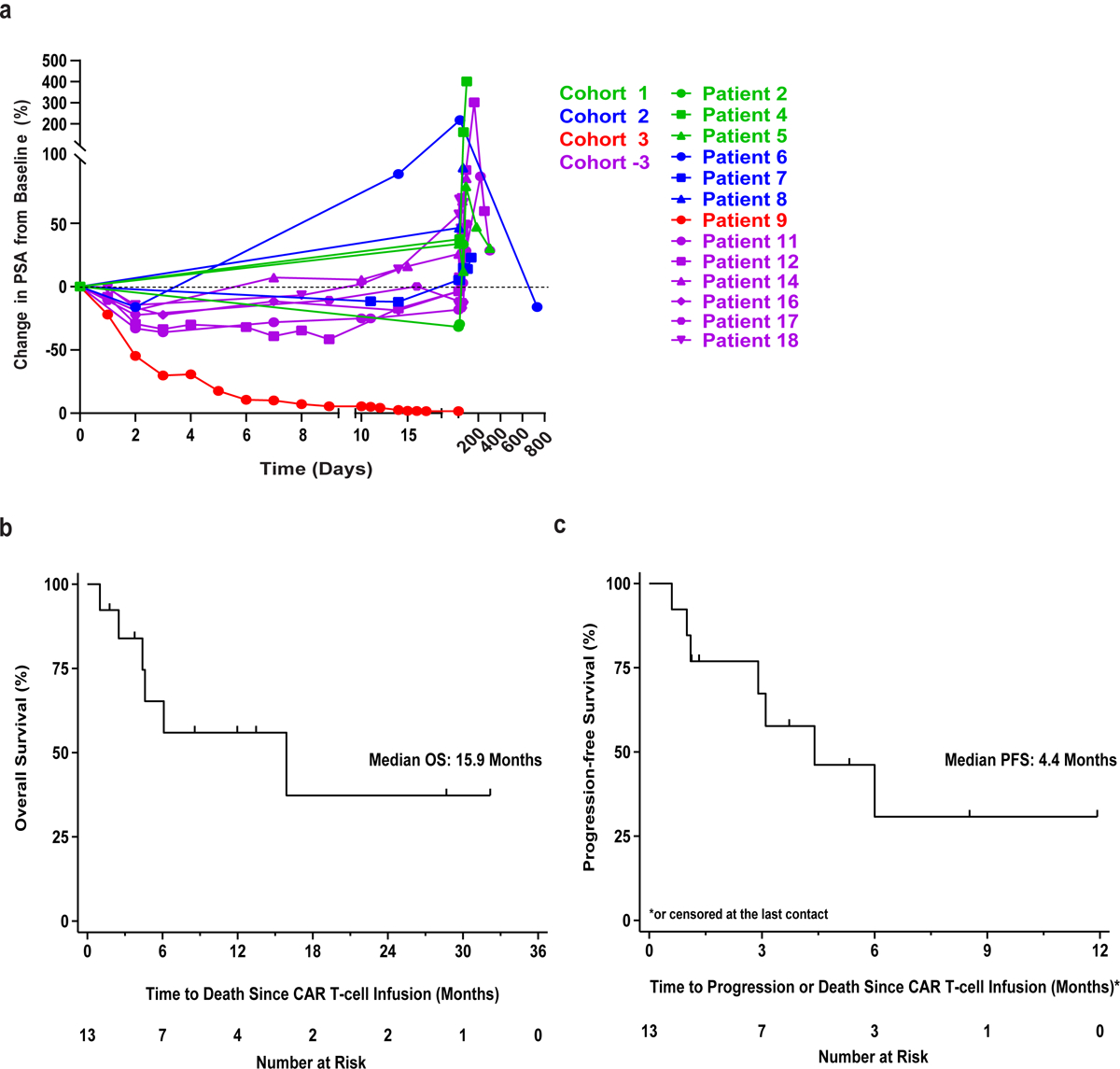

Preliminary antitumor response, as measured by maximum decline in PSA from baseline, is shown in Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 5a. A decrease in PSA levels of at least 30% (PSA30 response) was observed in four of thirteen infused subjects (30.1%), with a higher frequency of PSA decline observed in dose-level cohorts with LD. The median observed PSA decline was 22.35% (range: 12% to 98.33%), including Patient 9 who rapidly achieved a PSA level of <0.1 ng/ml within 2 weeks of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion and prior to the grade 5 AE.

Best radiographic response as assessed by Prostate Cancer Working Group 2 (PCWG2) criteria40 was stable disease (SD), with 5 patients (38.5%) maintaining SD at the 3-month imaging assessment. Evidence of tumor regression was observed following CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell treatment of Patient 11 who experienced a 36% decrease in his serum PSA levels following CAR T-cell infusion (Fig. 3a–3b). Overall, no partial responses per standard Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)41 were observed. A Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival (OS) is shown, with median OS of 477 days (15.9 months; Extended Data Fig. 5b) and PFS of 132 days (4.4 months; Extended Data Fig. 5c) in these 13 subjects. The OS reflects that most patients were well enough and chose to go on to other treatments (Figure 1c).

CAR T-cell trafficking and characterization of the TME

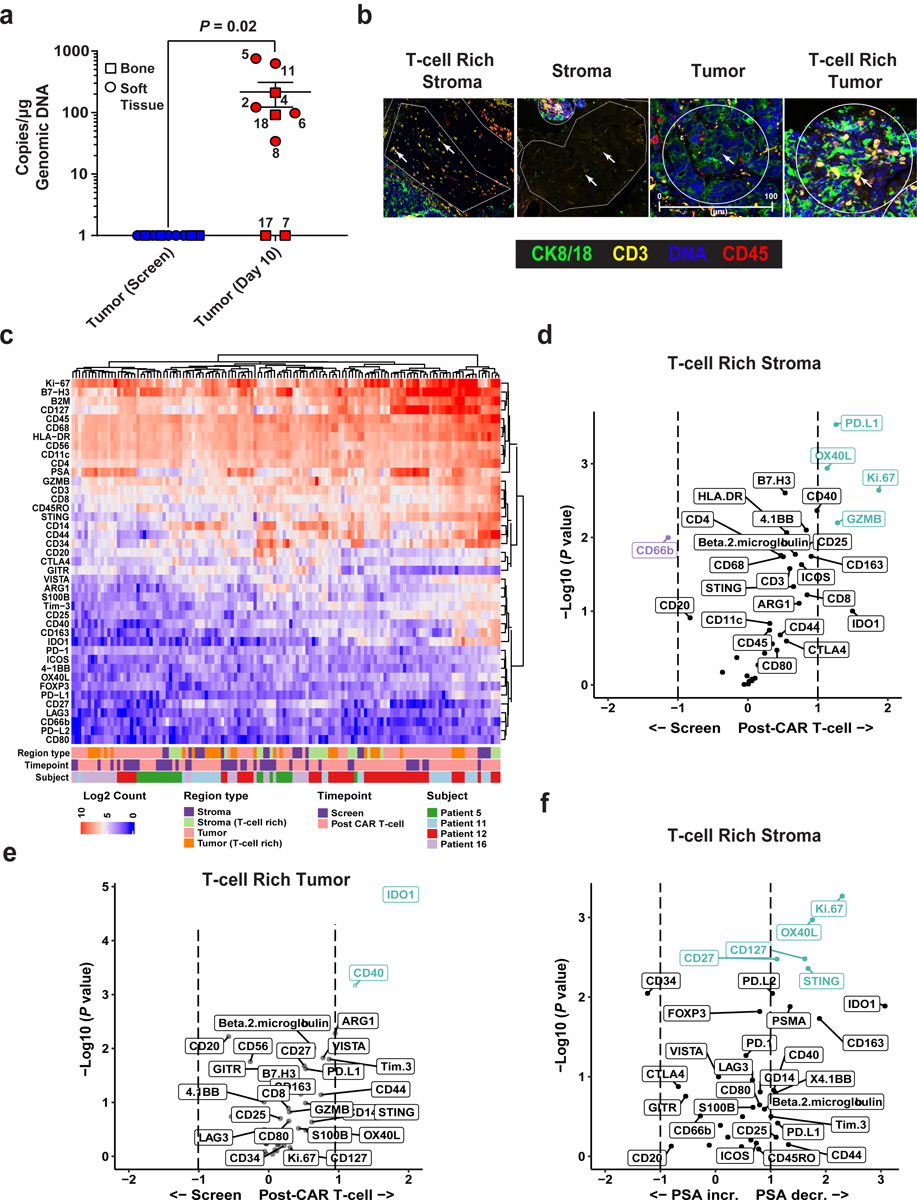

CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells were detectable at approximately 10 days post-infusion in 7 out of 9 metastatic biopsies examined (Fig. 4a, Methods). The level of CAR marking seen in metastatic tumor samples was generally 1-log lower than that seen in peripheral blood at the same time point for five patients. Notably, in one subject (Patient 5), the marking in the metastatic tumor was 759 copies/microgram compared to 44 copies in the peripheral blood and represented the highest level of marking seen in any of the metastatic tumor biopsies (Fig. 4a). We did not observe significant correlations between the frequencies of infusion product CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells and CAR levels in tumors or the peripheral blood. However, there was a significant negative correlation seen between proportions of infusion product CAR T-cells and serum TGFβ1 at the peak of in vivo CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell expansion (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 4. T-cell trafficking and digital spatial profiling (DSP) of the TME in CRPC biopsies before and after CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion.

(a) CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN quantification by qPCR in tumor biopsies at baseline relative to post-CAR T-cell infusion time points in evaluable patients is plotted. Biopsy type (bone or soft tissue) indicated by different shapes. Subject identification numbers are indicated next to data points. Error bars represent the mean with SEM. P value determined using a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired samples. (b) Multi-label immunofluorescent staining of a post-CAR T cell infusion tumor biopsy to visualize tissue morphology and identify various regions of interest (ROIs) for DSP is shown. Cytokeratin (CK) 8/18 was used to identify tumor cells. Other morphology markers included CD3, CD45 and Cyto83 stain for DNA content analysis. Four illustrative ROIs are presented (scale bars, 100μm). Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. (c) Heat map depicts the relative quantification of 42 proteins that were detected in stromal, tumor, and T-cell rich ROIs in biopsy specimens at baseline (screen) and post-CAR T-cell administration. (d) Volcano plots presenting an overview of fold changes in protein expression in T-cell rich stromal ROIs and (e) T-cell rich tumor regions at pre- versus post-CAR T-cell treatment time points. (f) Protein correlates of PSA increase (incr.) and decrease (decr.) in the T-cell rich stromal portion of the TME at 10 days following CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell administration. For d-f, protein names colored in purple and green denote markers with a FDR < 0.05.

We explored the TME (Fig. 4b) for expression of T-cell activation/effector function, myeloid and tumor markers as well as immunosuppressive molecules (Fig. 4c) using protein-based digital spatial profiling (DSP). A relative increase in proliferation (as denoted by increased Ki-67 expression) and activation (increased Granzyme B (GZMB) and OX40L expression) of T-cells localized to the stroma in situ post-PSMA-TGFβRDN CAR T-cell administration was observed (Fig. 4d). While we cannot directly enumerate the number of activated T-cells that appeared to increase from baseline to day 10, there is strong evidence that an elevation in T-cell activation markers is most correlated with the presence of T-cells and not other immune cell types, as expected. Based on the expression of CD11c, CD163, CD20, CD56, CD66b, CD68, CD3, CD4, CD8, FOXP3, CD45, and CD34, there is no overall change in immune cell types between time points. Yet across all 138 regions of profiled T-cell activation markers, most are positively correlated with the presence of T-cells versus other cell types. In T-cell rich tumor regions, factors associated with myeloid activation and suppression (e.g., IDO1, CD40) as well as a trend in expression of inhibitory molecules including T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-3 (Tim-3), programmed death-ligand 2 (PD-L2), V-domain Ig suppressor of T-cell activation (VISTA) and B7-H3/CD276 were upregulated (Fig. 4e).

Interestingly, Ki-67, OX40L, CD27 and CD127 were among the most significant direct correlates of PSA decrease in the T-cell rich stromal compartment. In contrast, expression of the CD34 single-pass transmembrane protein trended with PSA increase (Fig. 4f). Upregulated expression of this endothelial marker has previously been associated with high levels of serum PSA, tumor progression and aggressiveness in prostate adenocarcinoma42–45. An unexpected trend in increased PSMA expression was also observed in T-cell rich stroma and upregulated expression of PSMA, Ki-67, CD44, CD14 and CD40 was significantly associated with PSA decline in regions of T-cell/tumor co-localization (Supplementary Figure 3). Upon ranking the analyzed proteins in all 138 regions across evaluable biopsy samples in order of positive correlation with PSMA, the only significant correlations are CD127 (R = 0.48, P = 5.1e−09), CD25 (R = 0.37, P = 9.9e−06), Ki-67 (R = 0.49, P = 1.4e−09), and Beta-2-microglobulin (R = 0.38, P = 4.1e−06). Consistent with the results of a recent study46, our findings suggest that PSMA expression itself correlates with the presence of inflammation as reflected by these markers of T-cell activation, cell division and pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, respectively.

An unusual case of clonal CAR T-cell expansion

Patient 9 was a 72-year-old man diagnosed with metastatic progression of prostate cancer approximately 4 years prior to study enrollment. No soft tissue or visceral metastatic disease was present, and tumor burden was low at study enrollment (Fig. 5a). As described above, following CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion, the massive expansion of CAR T-cells in the peripheral blood of Patient 9 correlated with a >98% reduction in his serum PSA levels (Fig. 5b). Notably, serum TGFβ1 also decreased following administration (Fig. 5c), which trended with increased CAR T-cell proliferation over time (Fig. 5b). The patient developed fever and hypotension, accompanied by rapid elevations in IL-6 and ferritin. The ensuing high-grade CRS required multi-modal immunosuppressive measures (Fig. 5d).

Figure 5. Evaluation of clinical responses and other correlatives following adoptive transfer of CAR T-cells in an mCRPC patient.

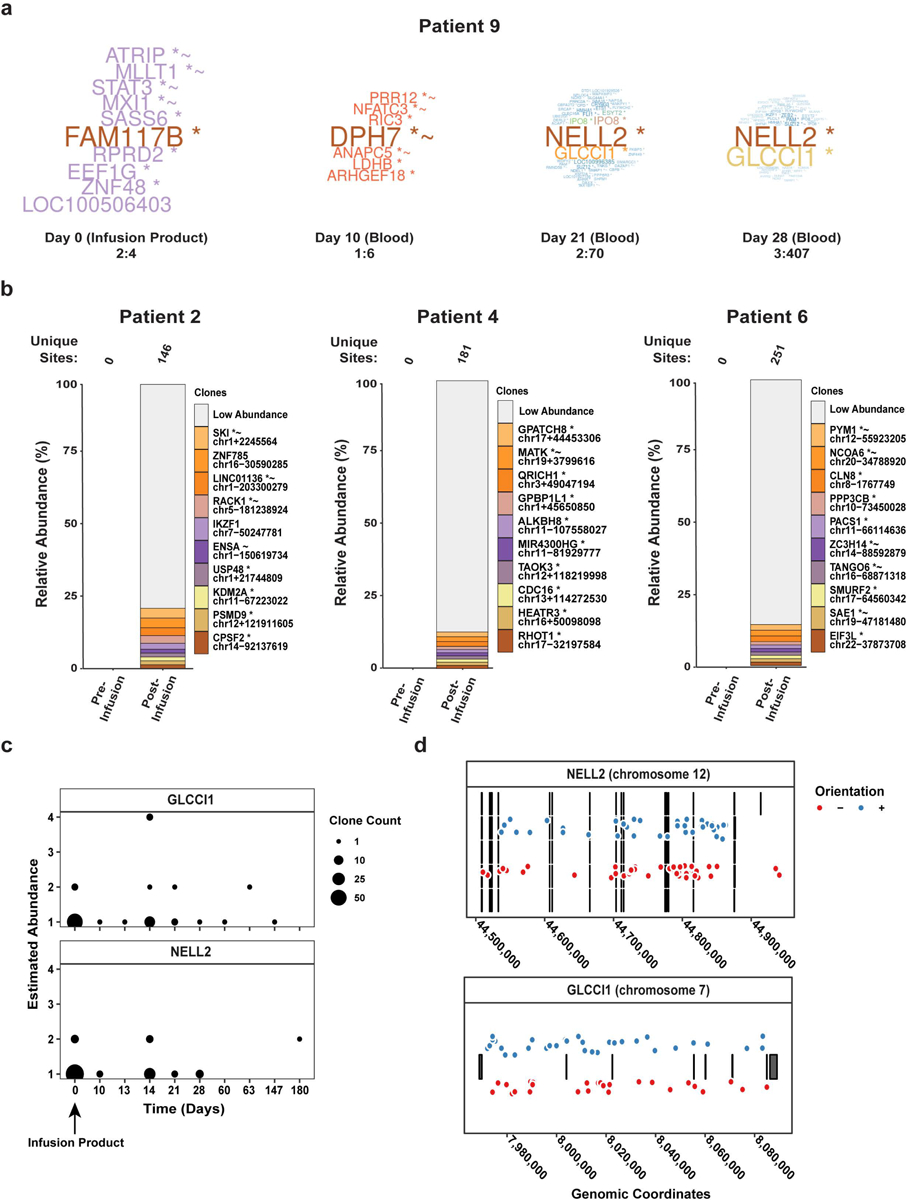

(a) Bone scintigraphy (anterior-posterior and posterior-anterior views) for bone metastasis detection in a 71-year-old patient diagnosed with mCRPC is shown. (b) In vivo expansion kinetics of CAR T-cells plotted with changes in serum PSA and (c) TGFβ1 levels over time are depicted. (d) Longitudinal measurements of serum IL-6 and ferritin before and after CAR T-cell infusion are displayed. Various interventions administered for management of cytokine-related toxicity are displayed. (e) Flow cytometric proportions of HLA-DR positive CAR T-cells before and after infusion are shown. (f) Analysis of TCRVβ repertoire diversity in the CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion product and following transfer are presented. Each pie chart segment denotes the frequency of clones belonging to a particular TCRVβ family. The annotated nucleotide sequence of the dominant TCRVβ18.1 clone appears below the pie charts. (g) Longitudinal CAR T-cell clonal abundance as indicated by lentiviral integration sites is shown. Different colors (horizontal bars) indicate major cell clones. A key to the sites, named according to the nearest gene, is shown below the graph (abundances < 3% were categorized as “Low Abundance”).

At day 10 post-CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion, 90% of peripheral blood CD3+ T-cells expressed the anti-PSMA CAR, 83% of which were highly activated as denoted by HLA-DR expression (Fig. 5e). Pre-infused CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells and the peripheral blood CD8+ T-cell compartment on day 10 following administration were polyclonal, with multiple TCRVβ families similar between the samples (Fig. 5f). At the peak of in vivo CAR T-cell expansion, TCRVβ18 family usage exhibited a skewing, with a clonal dominance of approximately 60% occurring in CD8+ CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells (Fig. 5f). Deep sequencing of the T-cell receptor beta repertoire indicated that the day 28 CD8+ CAR T-cell compartment was dominated by a Vβ18–01, D02, J02–07 rearrangement representing an expanded clone (Fig. 5f, Supplementary Fig. 4).

Analysis of the Patient 9 CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion product detected 12,986 unique CAR lentiviral vector integration sites, which at day 10 declined to 2,833 sites in the blood (Fig. 3g). At day 21 post-infusion, two dominant integration sites were observed among abundant clones, indicative of a clonal expansion. One site was in chromosome 2 in the neural EGFL like 2 (NELL2) gene, and the second occurred in chromosome 12 in the glucocorticoid-induced transcript 1 protein (GLCCI1) gene (Fig. 3g, Extended Data Fig. 6a). These two integration sites increased in frequency in the blood by day 28 but were not detected in the infusion product or at day 10 post-treatment (Fig. 3g). Confirmatory quantitative digital PCR analysis of NELL2 and GLCCI1 in post-infusion PBMCs showed similar frequencies of cells harboring these integration sites by day 14 (Supplementary Fig. 5). We did not observe single integration sites at a frequency as high as that of NELL2 or GLCCI1 in other selected patients treated with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells (Extended Data Fig. 6b).

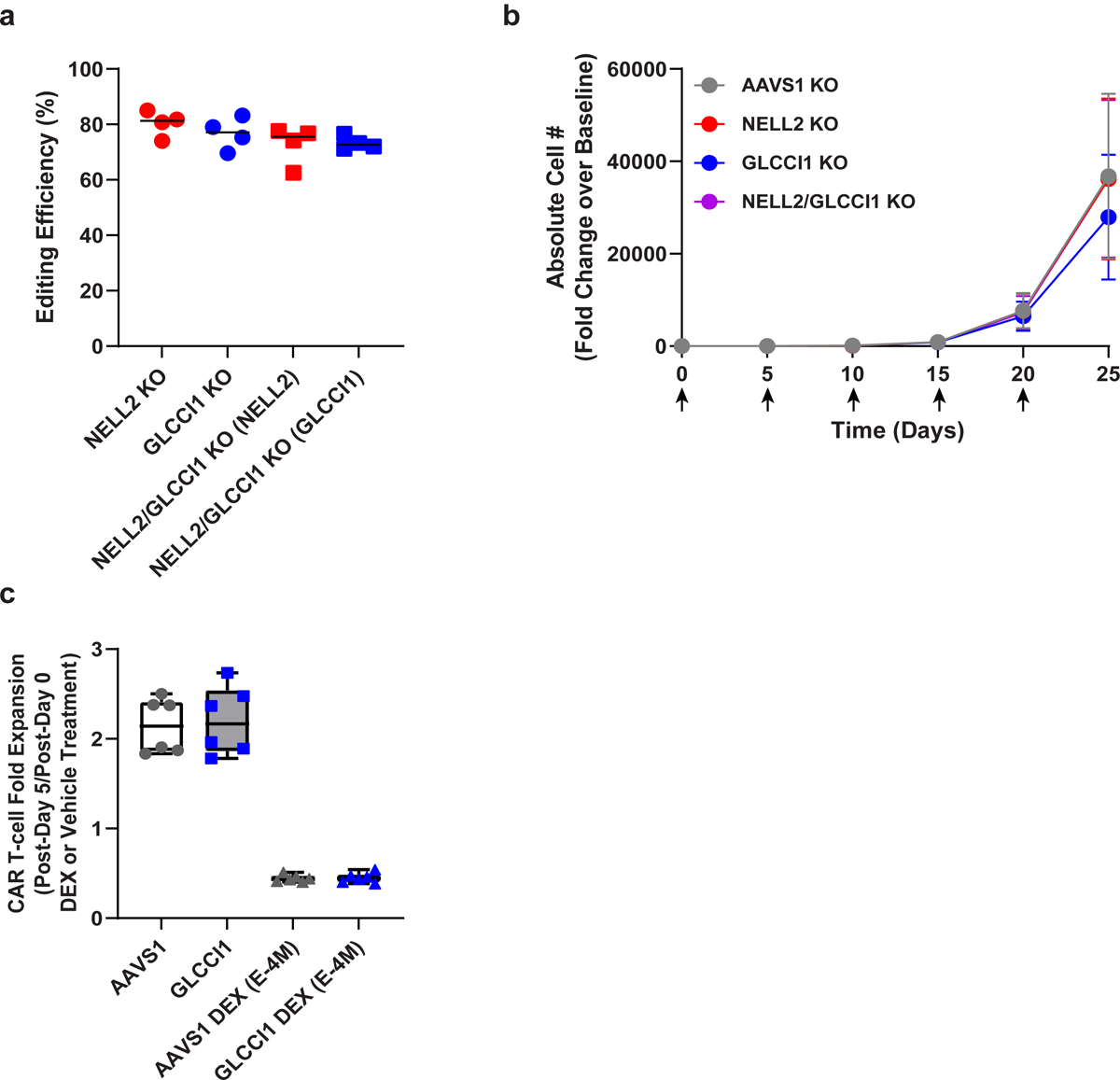

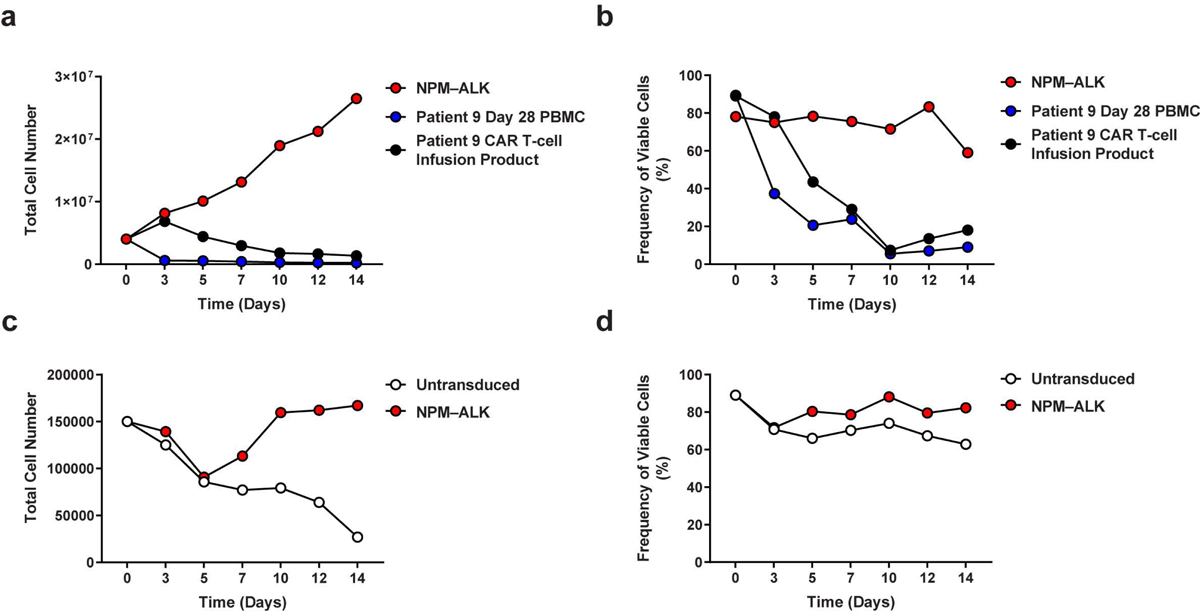

The heterotrimeric protein encoded by NELL2 may be involved in cell growth regulation as well as differentiation37, while GLCCI1 is expressed in both lung cells and immune cells and prevents glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis38. Examination of our previous trials of CD19 CAR T-cell therapy for acute and chronic leukemia revealed NELL2 and GLCCI1 integrants in 35 and 33 patients, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 6c–d, Supplementary Table 3). Three clones were identified at more than one time point, but their frequency in the blood decreased over time in subjects treated for advanced leukemia (Supplementary Fig. 6). CRISPR/Cas9-based mutagenesis of NELL2 and GLCCI1 did not alter the antigen-dependent proliferation (Extended Data Fig. 7a–b) or viability of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells. We also examined whether GLCCI1 knockout potentiates resistance to glucocorticoid treatment. Genetic disruption of GLCCI1 did not potentiate in vitro CAR T-cell expansion nor survival in the presence of a synthetic glucocorticoid compound (Extended Data Fig. 7c). Finally, neither the Patient 9 CAR T-cell infusion product nor clonally-expanded CAR T-cells from the day 28 post-administration time point exhibited antigen-independent growth in in vitro transformation assays that include cytokine- and stimulation-free conditions or pan-antigen receptor activation in the presence of IL-2 and forced expression of the NPM-ALK kinase as a positive control39 (Extended Data Fig. 8).

Discussion

In this first-in-human study, we evaluated the feasibility and safety of PSMA-directed TGFβ-resistant CAR T-cells in patients with treatment-refractory mCRPC. The inclusion of a TGFβRDN as functional “armor” in our CAR construct sought to attenuate a common immunosuppressive barrier in the mCRPC TME, with the goal of potentiating improved proliferation, effector cytokine elaboration, and CAR T-cell persistence. A recent study demonstrates that tumor-specific T-cells engineered to express a dominant-negative TGFβ receptor type 2 safely expand and persist in Hodgkin lymphoma patients without LD prior to infusion; these engineered cells induced complete responses even in subjects with resistant disease25. Our analysis of the pre-infusion cell product demonstrated successful attenuation of TGFβ activity, and we noted decreased serum TGFβ1 levels post-CAR T cell transfer in Patient 9 who had the highest degree of in vivo CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell expansion. Although it is possible that this observed reduction is attributed to clearance of TGFβ-secreting tumor cells, an alternative explanation is that the presence of very large numbers of CAR T-cells expressing a dominant-negative cytokine receptor acted as a “sink” for free TGFβ.

As demonstrated in Cohorts 3 and −3, pre-infusion LD significantly potentiated CAR T-cell proliferation. This favorable effect of chemotherapy pre-conditioning on CAR T-cell kinetics is consistent with previous reports describing the use of Cy/Flu LD to enhance anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and large cell lymphoma47–49. In Cohort 3, we observed peripheral blood CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell proliferation comparable to levels of the highest expansions seen in acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients achieving complete remission with anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy4.

Expression of inflammatory cytokines was also observed in higher-dose level cohorts infused with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells and strongly correlated with the onset and resolution of CRS. This finding is consistent with multiple prior trials of anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy for leukemia4,32,50. However, unlike many of the leukemia and lymphoma CAR T-cell trials, CRS observed in this study does not consistently appear to be related to in vivo product expansion over time. With respect to the post-infusion course of Patient 9, this is one of the first reports to demonstrate dramatic changes in the levels of serum cytokines associated with CRS due to systemic CAR T-cell administration for a solid tumor indication.

In CAR T-cell therapies for cancer, DNA encoding the CAR is typically delivered to cells using integrating viral vectors, raising the question of whether insertional mutagenesis by vector integration influences subsequent T-cell expansion. We and others have previously identified multiple loci marked by vector integration that are associated with CAR T-cell proliferation, persistence, and in some cases, clonal outgrowth51–53. Although our data cannot definitively exclude the possibility of integration events contributing to the clonal expansion of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells in Patient 9, they do not point to a single vector integration site as the main driver of clonal proliferation. However, the finding that the dominant clonotype was only detected following the onset of refractory grade 4 CRS is consistent with previous work showing that clonal T-cell expansion requires prolonged exposure to inflammatory cytokines in concert with the presence of antigen and co-stimulation54,55.

Preliminary evidence for early antitumor function was observed in this trial, including a PSA30 decline in approximately 30% of treated patients although PSA responses were of limited durability. The relatively small patient sample size and inclusion of subjects with extensive prior treatment histories limits interpretation of survival outcomes. Given the transient antitumor effects and bioactivity of these CAR T-cells, other potency-enhancing measures will likely be required for a sustained therapeutic benefit. Further, the safety window for CAR T-cell administration in a primarily elderly prostate cancer population with common medical comorbidities was narrow and requires further investigation. Importantly, while Patient 9 demonstrated a rapid and marked PSA decline of >98%, this subject experienced fatal toxicity. It is intriguing to speculate that the TGFβRDN may have played a role in severe CRS and the eventual death of Patient 9, but we do not have direct evidence to support this hypothesis and several other various factors (i.e., cell dose, lymphodepletion regimen, etc.) could have contributed to toxicity, marked PSA response and outcome in this subject. Thus, although the subsequent reduction in CAR T-cell dose in Cohort −3 was safe and feasible, it also appeared to result in lower peak cytokine levels and CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell expansion, relative to what was documented in Patient 9.

Our findings informed the design of a second clinical study of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells in patients with mCRPC (clinicaltrials.gov NCT04227275). The initial dose levels in the second multi-center phase 1 trial were influenced by two key findings from our study: 1) the importance of lymphodepletion to enhance cell proliferation and function and 2) the need for further refinement of the transduced cell dose, given the observed dose-dependent toxicity. These collective findings suggest that future studies should seek to augment clinical efficacy, while incorporating enhanced toxicity mitigation strategies to improve the therapeutic window.

We found that within the first 2 weeks of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN infusion, there was some infiltration of CAR T-cells into the tumor, although this observation was not consistent in all evaluable patients. In this regard, locoregional administration of CAR T-cells has been found to improve T-cell tumor infiltration and antitumor activity both pre-clinically56–60 and in recent human trials61–63. Additionally, DSP analysis of over 40 different proteins in the TME of five patients suggests that upregulated expression of multiple immunosuppressive molecules after CAR T-cell administration may hamper in situ activation and elicitation of sufficient antitumor effector function. Notably, molecules associated with myeloid activation and suppression were among the most significantly increased factors in T cell-rich tumor regions following treatment with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells. In accordance with these findings, myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) abundance is known to correlate with PSA levels and metastasis in advanced prostate cancer patients64–66. The upregulation of additional inhibitory mediators is in line with our previous clinical trial of EGFRvIII-directed T-cells for recurrent glioblastoma in which the TME became even more immunosuppressive after intravenous CAR T-cell administration67. Further, the density of activated T-cells in the tumor stroma was most associated with PSA decline, paralleled by protein expression patterns reminiscent of a favorable T-cell/TME immune contexture (i.e., increased expression of Ki-67, OX40L, CD27 and CD127). In contrast, upregulated expression of the endothelial marker, CD34, post-CAR T cell infusion was associated with increased PSA levels. These results define a contexture rich in select T-cell and T-cell-modulating molecules and suggest new intervention strategies as well as potential biomarkers of response.

In conclusion, this first-in-human clinical trial of PSMA-redirected TGFβ-resistant CAR T-cells demonstrated feasibility and safety. Due to the practical implications of this work, further validation and investigation in large, prospective, randomized studies is warranted. These findings lay the foundation for CAR T-cell therapy prostate cancer clinical trials, including ongoing and future studies to enhance efficacy, predict response or resistance and optimize the therapeutic window to eradicate solid tumors.

Methods

Cell lines and viral vectors

The PC3 prostate cancer cell line was originally isolated from a bone metastasis of a 62-year-old Caucasian with grade IV adenocarcinoma of the prostate and purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). This cell line was engineered to express the PSMA protein, click beetle green luciferase and green fluorescent protein (CBG-GFP), followed by single-cell purification and expansion of master banks20. The engineered PC3 cells were maintained in D10 media consisting of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium supplemented with 10% FBS (GeminiBio), HEPES, penicillin, and streptomycin. Low passage working banks of PC3 cells were routinely tested for mycoplasma with the MycoAlert kit as per the manufacturer’s (Lonza) instructions. Cell line authentication was performed by the University of Arizona (USA) Genetics Core using criteria established by the International Cell Line Authentication Committee. Short tandem repeat (STR) profiling showed that the identity of this line was above the 80% match threshold.

The CAR-PSMA-TGFβRDN construct (Supplementary Fig. 7) and control CAR-CD1968 were assembled as previously described20. Lentiviruses were packaged in HEK 293T cells (i.e., routinely screened for identity and mycoplasma contamination) and titered according to our published methods20,68,69.

Generation of CAR T-cells for pre-clinical studies

Autologous T-cells were collected by leukapheresis and activated using anti-CD3 and -CD28 agonistic antibody-coated polystyrene beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by transduction with the above lentiviral vectors at a multiplicity of infection of 2.5. CAR T-cell expansion was carried out for 10 days20,68,69. Cell counts and viability assessments were obtained during T-cell expansion with a Luna automated cell counter (Logos Biosystems).

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout of TGFBR2, NELL2 and GLCCI1

The genomic guide RNA (gRNA) TGFBR2, NELL2, GLCCI1 and control AAVS1 target sequences were 5′-ATTGCACTCATCAGAGCTAC-3′, 5′-CAGGTCCCGGGGCTGCATAA-3′, 5′-GATCGCCAGTCACCTCTTCA-3′ and 5′-CCATCGTAAGCAAACCTTAG-3′, respectively. Corresponding chemically-modified sgRNAs were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. and complexed with TrueCut Cas9 protein (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ribonucleoprotein complexes were then delivered into primary human T-cells, followed by lentiviral transduction with CAR-PSMA or CAR-PSMA-TGFβRDN vectors and expansion of edited CAR T-cells carried out as previously described70. Knockout efficiencies were determined by amplification of purified genomic DNA with primers (Supplementary Table 4) and Sanger sequencing, followed by Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) analysis71.

Xenograft model of human prostate cancer

Animal experiments were performed with 8- to 12-week-old male NOD/SCID/IL-2Rγ-null (NSG) mice (University of Pennsylvania Stem Cell and Xenograft Core), under an approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol. Animals were maintained in pathogen-free conditions at a 12 light/12 dark cycle and an ambient temperature of 21 ± 2°C with 60 ± 20% relative humidity. Ad libitum access to acidified water and autoclaved food was provided. Mice were subcutaneously implanted with 2 × 106 PC3-PSMA-luciferase expressing tumor cells. On day 27, when average tumor size reached ~200 mm3, 1.7 × 105 PSMA-CAR T-cells (i.e., with TGFβRII KO or AAVS1 KO as a targeted “safe harbor” locus to control for gene editing) were injected intravenously. Tumor growth was monitored weekly using live bioluminescence imaging. Luciferase activity was analyzed using Living Image Software version 4.5.2 (PerkinElmer). Peripheral blood was collected at the peak of CAR T-cell expansion for flow cytometric enumeration and immunophenotyping of these lymphocytes.

Preclinical in vitro cellular assays

CAR T-cell in vitro proliferative “stress tests” on CAR-PSMA-AAVS1KO, CAR-PSMA-TGFβRIIKO, CAR-PSMA-NELL2KO, CAR-PSMA-GLCCI1KO, CAR-PSMA-NELL2/GLCCI1KO, CAR-PSMA-TGFβRDN (produced in the same manner as the KO groups) were carried out as previously described20,68,69. Briefly, following assessment of CAR transduction and target knockout efficiencies, engineered T-cells were isolated using anti-phycoerythrin (PE) or -allophycocyanine (APC) MultiSort Kits (Miltenyi Biotech). Purity was confirmed using flow cytometry and CAR T-cells were serially exposed (i.e., every 5 days) to irradiated PC3-PSMA tumor cells at an effector to target cell ratio of 1:1. To examine glucocorticoid sensitivity, gene-edited CAR T-cells were exposed to dexamethasone (Sigma) at indicated concentrations during the course of the restimulation assay. Absolute cell counts were obtained with a Luna automated cell counter (Logos Biosystems) during this assay.

The kinetics of CAR T-cell-mediated PC3-PSMA tumor cell lysis was evaluated using the impedance-based xCELLigence system (ACEA Biosciences Inc.). First, PC3-PSMA cell targets were plated in a 96-well, resistor-bottomed plate in triplicate according to the manufacturer’s (ACEA Biosciences Inc.) instructions. CAR-PSMA-AAVS1KO, CAR-PSMA-TGFβRIIKO, CAR-PSMA-TGFβRDN or an irrelevant CART-CD19 control were then added to achieve the desired effector-to-target (E:T) ratio 24 hours later. Impedance was assessed in 20-minute intervals over 100 hours and results are reported as normalized cell index values.

Study treatment and patients

This is a single center, single arm Phase 1 study to establish the safety and feasibility of intravenously administered lentivirally transduced CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells in mCRPC patients with a total of four dose-level cohorts. The site initiation visit occurred on March 8, 2017. This trial is conducted in accordance with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice, the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable institutional review board requirements (study protocol approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board). All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with local regulatory review. The Data Safety Monitoring Board provided appropriate oversight and monitoring of the conduct of this study to ensure the safety of participants and the validity as well as integrity of the data.

The rationale for our original three-cohort dose-escalation was informed by prior CD19 CAR T-cell (CTL019) trials from our group. We aimed to initiate dosing at a log-level below the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of CTL019, and to incorporate the lymphodepletion regimen after a single agent MTD dose was determined. Importantly, due to the unknown effects of targeting both PSMA as a tumor-associated antigen, as well as incorporation of a TGFβRDN, we designed our first-in-human dose-escalation with a more conservative dosing regimen as compared to the initial doses evaluated in a prior phase I dose-escalation study in mCRPC evaluating PSMA re-directed CAR T-cells following cyclophosphamide lymphodepletion (NCT01140373). Given these uncertainties, we aimed to first test the PSMA-TGFBRDN CAR T-cell product at comparably lower dose levels, prior to incorporation of lymphodepletion (i.e., which we anticipated to enhance T-cell proliferation, anti-tumor activity and treatment-related toxicity). The dose escalation regimen we selected for Cohorts 1–3 was also similar to that used by our group in a trial evaluating the safety of anti-mesothelin CAR T-cells in other solid tumor indications, such as mesothelioma, ovarian cancer and pancreatic cancer with and without lymphodepleting chemotherapy (NCT02159716).

Patients received a single infusion of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells per the 3 + 3 dose-escalation design with the following dose levels: Cohort 1, 1–3 × 107/m2 CAR T-cells without LD; Cohort 2, 1–3 × 108/m2 CAR T-cells without LD; Cohort 3, 1–3 × 108/m2 CAR T-cells following a LD regimen using 3 daily doses of cyclophosphamide 300 mg/m2 and fludarabine 30 mg/m2 (Cy/Flu) both initiated 4 to 6 days prior to the planned CAR T-cell infusion. Following a DLT observed at the Cohort 3 dose level, the protocol was amended to treat up to 6 additional patients at a modified, de-escalated dose-level (Cohort −3) of 1–3 × 107/m2 CAR T-cells following Cy/Flu LD. All patients received CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusions with inpatient clinical monitoring for a minimum of 72 hours. Tocilizumab, corticosteroids, or other immunosuppressive measures were administered per investigator discretion for toxicity management. Eligible subjects included men with histologically confirmed mCRPC with evidence of progressive disease per PCWG2 criteria40.

Additional enrollment criteria included: ≥10% tumor cells expressing PSMA as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry analysis on fresh tissue; radiographic evidence of osseous metastatic disease and/or measurable, non-osseous metastatic disease (nodal or visceral); patients > or = 18 years of age; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 – 1; adequate organ function, as defined by serum creatinine ≤ 1.5 mg/dl or creatinine clearance ≥ 60 cc/min, serum total bilirubin < 1.5x upper limit of normal (ULN) and serum aspartate transaminase (ALT)/alanine transaminase (AST) < 2x ULN; adequate hematologic reserve within 4 weeks of study enrollment as defined by hemoglobin > 10 g/dl, platelet (thrombocyte) count (PLT) > 100 k/ul, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) > 1.5 k/ul and subjects must not be transfusion dependent; evidence of progressive castrate resistant prostate adenocarcinoma, as defined by castrate levels of testosterone (< 50 ng/ml) with or without the use of androgen deprivation therapy and evidence of one of the following measures of progressive disease in the 12 weeks preceding study enrollment: soft tissue progression by RECIST 1.1 criteria, osseous disease progression with 2 or more new lesions on bone scan (as per PCWG2 criteria), increase in serum PSA of at least 25% and an absolute increase of 2ng/ml or more from nadir (as per PCWG2 criteria); prior therapy with at least one standard 17α lyase inhibitor or second-generation anti-androgen therapy for the treatment of metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer; provision of written informed consent. Subjects of reproductive potential must agree to use acceptable birth control methods. Prior treatment with an immune-based therapy for the treatment of prostate cancer, including cancer vaccine therapies (such as Sipuleucel-T, PROSTVAC) are allowable. Under protocol-specified conditions, immune checkpoint inhibitors, radium-223 and immunoconjugate therapies are also allowable. Exclusion criteria included: history of an active non-curative non-prostate primary malignancy within the prior 5 years; subjects who require the chronic use of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Patients may be on a low dose of steroids (≤10 mg equivalent of prednisone); subjects with Class III/IV cardiovascular disability according to the New York Heart Association Classification; subjects with symptomatic vertebral metastases affecting spinal cord function (as determined by clinical history, physical exam, or MRI imaging); history of active or severe autoimmune disease requiring immunosuppressive therapy; patients with ongoing or active infection; history of allergy or hypersensitivity to study product excipients (human serum albumin, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and Dextran 40); active hepatitis B, hepatitis C or HIV infection.

During study enrollment, we did not pursue selection of patients based on perceived disease biology and/or ease of metastatic biopsy sampling. We note that among the thirteen patients treated with CAR T-cell therapy, seven patients had bone metastases, seven patients had lymph node metastases, three patients had ‘bone-only’ metastases, and three patients had ‘lymph-node only’ metastases. A final patient had liver metastasis. Thus, ultimately, there was equal balance between bone and lymph node metastatic sites across the study enrollment. As bone and lymph nodes are the most common sites for metastatic dissemination in mCRPC, we feel that this distribution is reflective of a general late-stage mCRPC population.

CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell manufacturing

Following confirmation of tumor tissue PSMA expression, patients underwent ~10-liter apheresis at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania Apheresis Center. The manufacture and release testing of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells was performed by the Clinical Cell and Vaccine Production Facility at the University of Pennsylvania according to Phase 1 IND current Good Manufacturing Practice guidelines and FACT Common Standards for Cellular Therapies. PSMA-TGFβRDN CAR T-cells were produced using a bi-cistronic lentiviral vector allowing co-expression of TGFβ dominant negative receptor II transgene (TGFβRDN) and the anti-PSMA (comprised of the J591 single chain variable fragment and 4–1BB/CD3ζ endodomains)20. T-cells were enriched from autologous leukapheresis products and activated with anti-CD3 and -CD28 antibody coated magnetic beads, followed by transduction with the lentiviral vector containing the PSMA-TGFβRIIDN CAR transgene. The transduced T-cells were expanded in cell culture in media containing IL-2 or a combination of IL-7 and IL-15. Two patient products were originally manufactured in IL-7/IL-15 because there was an unplanned failure to meet the study-specified expansion threshold/cell dose for formulation of the infusion product in the IL-2-based culture conditions. An IND amendment permitted us to re-manufacture products for these two subjects using IL-7/IL-15, which resulted in successful expansion and dose formulation. Following this amendment, subsequent large-scale patient CAR T-cell expansion was done with IL-7/IL-15 to avoid manufacturing failures. Cell products were released for infusion following confirmation of FDA-specified criteria, including transduction efficiency of ≥2%. If the initial harvest of the CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell product did not meet release criteria, enrolled patients had the option to undergo repeat leukapheresis and/or manufacture from retained cell collection.

Outcome and clinical study assessments

The primary outcome measure was the occurrence of AEs experienced by subjects infused with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells (time frame: week −8 through end of study approximately 24 months after infusion) assessed using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.03. Secondary outcome measures included assessment of the clinical anti-tumor effect of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells (time frame: week −2, day 28. month 3 and 6) assessed using RECIST 1.1 criteria; evaluation of the clinical anti-tumor effect of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells (time frame: week −2, day 28. month 3 and 6) using PCWG2 criteria for bone disease; determination of the clinical anti-tumor effect of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells [time frame: week −2, day 28. month 2, 3 and 6] using serum PSA measurements. Patients were assessed for safety on days 1, 3, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28 following CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion. Peripheral blood was collected at serial time points for evaluation of CAR T-cell expansion and persistence by quantitative PCR (qPCR) of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN DNA and for assessment of the bioactivity by multiplex immunoassays. Subjects underwent a metastatic tissue biopsy approximately 10 days following CAR T-cell infusion for evaluation of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN tumor tissue trafficking. Serum PSA and CRPC disease imaging, including computed tomography and Tc-99m bone scintigraphy, were performed at baseline, day 28, month 3 and month 6 following CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN infusion.

T-cell characterization in apheresis and infusion products

Archive vials of cryopreserved leukapheresis samples from each subject were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD4/CD8 ratio and the proportion of CD8+ T-cell memory subsets as previously described69. Briefly, the samples were thawed in 37°C water bath, washed and resuspended with R10 culture media (RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS) and stained with live dead aqua dye (catalog # L34957, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After washing, the cells were stained in FACS buffer (PBS + 1% FBS + 0.2% sodium azide) containing surface mouse-anti-human antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD27, CD28, CD45 and CD45RO. Intracellular staining was carried out following fixation and permeabilization of cells using the FoxP3 Fixation/Permeabilization Kit (eBioscience). Cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde prior to acquisition on a Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using FCS Express version 7 (De Novo software) or FlowJo software version 10 (FlowJo, LLC).

Resistance of patient T-cell infusion products co-expressing TGFβRDN and CAR transgenes to TGFβ signaling was tested via acute exposure to 10 ng/ml of recombinant human TGF-β1 (catalog # 240-B-010, R&D Systems). Following cytokine stimulation, cells were fixed and stained for flow cytometric detection of SMAD2 protein phosphorylated at Ser465/467 sites and the SMAD3 protein phosphorylated at Ser423/425 sites according to the manufacturer’s protocols (catalog # 562586, BD Biosciences)20.

Quantitative PCR analyses

Each amplification reaction contained 200 ng genomic DNA per time-point for peripheral blood and marrow samples. To determine copy number per unit DNA, an 8-point standard curve was generated consisting of 5 to 106 copies of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN lentivirus plasmid spiked into 200 ng of non-transduced control genomic DNA. The number of copies of plasmid present in the standard curve was verified using digital qPCR with the same primer/probe set and performed on a QuantStudio™ 3D digital PCR instrument (Life Technologies). Each data-point (i.e., sample, standard curve) was evaluated in triplicate with a positive cycle threshold (Ct) value in 3/3 replicates with %CV (coefficient of variation) less than 0.95% for all quantifiable values. To control for the quantity of interrogated DNA, a human genomic DNA reference assay was performed using 10 ng genomic DNA and a primer/probe combination specific for a non-transcribed genomic sequence upstream of the CDKN1A (p21) gene as previously described50. These amplification reactions generated a correction factor to adjust for calculated versus actual DNA input. Copies of transgene per microgram DNA were calculated according to the formula: Copies/microgram genomic DNA = copies calculated from CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN standard curve × correction factor/amount DNA evaluated (ng) × 1000 ng.

A PCR assay was developed to amplify regions of DNA harboring NELL2 and GLCCI1 integration sites as wells as TCRVβ18.1 clone-specific sequences (Supplementary Fig. 5) and conducted according to our previously reported methods51. Primer sequences can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Serum cytokine profiling

Serum samples prior to and after infusion cryopreserved at −80°C were thawed and analyzed for cytokine measurements using human cytokine magnetic 30-plex panel (Life Technologies), or a 31-plex panel (Millipore Sigma) as previously described72. Serum TGFβ1 was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Human/Mouse/Rat/Porcine/Canine TGF-beta 1 Quantikine ELISA, R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of CAR T-cell clonal diversity

Genomic DNA from pre-infusion CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells and sorted post-infusion CAR T-cells was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Initial flow cytometric assessment the T-cell repertoire by flow cytometry was conducted using the Beta Mark TCRVβ repertoire kit and Kaluza analysis software (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences). Subsequent TCRVβ deep sequencing was carried out by immunoSEQ (Adaptive Biotechnologies). Only productive TCR rearrangements were used in the evaluation of clonotype frequencies.

Lentiviral integration site analysis

Sites of CAR vector integration were detected from genomic DNA as described previously51,73–76. BLAT (hg38, version 35, >95% identity) was used for alignment of genomic sequences to the human genome. The statistical methods used to analyze distributions of integration sites were carried out according to our published methods77. The abundance of cell clones was inferred from integration site data via the Sonic Abundance method75. Analysis of all samples was done independently in quadruplicate to mitigate any PCR-based founder effects and stochastics of sampling.

In vitro transformation assay

To determine whether CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells from Patient 9 exhibited aberrant growth patterns potentially indicative of transformation, two different in vitro assays were conducted. In the first method, 60 million infusion product T-cells and 8 million PBMC corresponding to the day 28 post-CAR T-cell infusion time point were thawed and maintained in cytokine-free X-VIVO15 media (Lonza) supplemented as previously described78 in the absence of antigen stimulation for 14 days. Unrelated donor T-cells previously transformed with the Y664F NPM–ALK mutant39 served as a positive control for antigen- and cytokine- independent growth in these conditions. In a separate experiment, day 28 PBMCs from Patient 9 were thawed and subjected to monocyte removal. Cells were then placed into supplemented X-VIVO15 media containing recombinant human IL-2 (100 units/mL, Peprotech). Anti-CD3/CD28 agonistic antibody-coated Dynabeads were then added to cell cultures at a bead:cell ratio of 3:1. Following a 24-hour incubation, a lentivirus encoding an NPM-ALK fusion kinase39 or vehicle alone was added to the appropriate culture. T-cells were maintained in the presence of IL-2 and counted over 14 days.

For both assays, cells in long-term culture were enumerated and viability was assessed using acridine orange/propidium iodide staining.

Digital spatial profiling of the TME

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue from pre- and post-CAR T cell treatment biopsies were profiled using GeoMx® digital spatial profiling (DSP)79. Tissue morphology was visualized using fluorescent CK8/18, CD45 and CD3 antibodies and Cyto83. Regions of interest (ROI) of ~100 μm geometric shapes (squares, polygons, circles) were selected in tumor only (CK8/18+), areas comprising T-cells in tumor (CD3+, CK8/18+) as well as T-cells in stroma (CD3+, CK8/18). DSP Human Protein Immune Cell Profiling Core, IO Drug Target, Immune Cell Typing and Pan-Tumor panels (NanoString Technologies) were assessed using an nCounter®-based read out.

Raw GeoMx® data were ERCC-normalized followed by normalization based on control molecules. Briefly, the two classes of control molecules (Housekeeping proteins [S6, Histone H3, and GAPDH] and isotype controls [MS IgG1, Ms IgG2a, and Rb IgG]) were used to check for internal consistency and to ensure treatment type (pre-treatment versus post-treatment) was not confounded with control molecule expression. Consistency within each class was done by comparing the root mean squared error between each of the three molecules across all ROIs for a given class. Housekeepers showed the least between-molecule variation (i.e., more consistency) and was therefore chosen as the normalization factor. Specifically, for each ROI, the geometric mean of the housekeeping protein expression values was computed. The normalization factor for each sample was then computed as the grand mean of geometric means divided by the sample-specific geometric mean. Finally, ERCC-normalized expression values for each protein were multiplied by its sample-specific normalization factor. A visual inspection of the normalization factors was done to ensure no ROI showed extreme values (i.e., +/− 4 in log2 space). Feature-based filtering was done by comparing a modified signal to standard deviation (SSD) approach80. The SSD was computed for each protein p and sample s by:

Where and are the geometric mean and standard deviation of isotype controls for sample s, respectively. Proteins were retained if at least one sample had an SSD > 1 (i.e., 42 proteins were retained).

Statistical analyses

For pre-clinical studies, statistical analyses were performed using the D’Agostino-Pearson omnibus test for normality, a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test, or a parametric Student’s t- as appropriate for paired or unpaired samples. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 8-GraphPad (GraphPad Software). P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

The primary objective of the clinical trial was to determine the safety and feasibility of a single infusion of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN. Because this study implements the traditional 3+3 design with 3 cohorts, up to 21 safety endpoint evaluable subjects will be enrolled. Safety was assessed by the occurrence and severity of AEs per National Cancer Institute (NCI) – Common Terminology Criteria (v4.03)34. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) was graded per the ASTCT consensus grading system34. A DLT was defined as any of the following when deemed related to PSMA-TGFβRDN CAR T-cell therapy: any Grade 3 or higher hematologic or non-hematologic toxicity, except asymptomatic Grade 3 electrolyte abnormalities, Grade 3 nausea, vomiting, diarrhea or fatigue, or Grade 3 non-hematologic toxicities that could be controlled to ≤ Grade 1 with appropriate management. A total of 13 subjects were treated at the conclusion of the trial as described in the Results section, all of whom were included for analyses of the safety and secondary efficacy endpoints. All subjects who received PSMA-TGFβRDN CAR-T cell therapy at the protocol-defined target dose were evaluable for safety assessment. Subjects who did not receive protocol-defined therapy were replaced.

The feasibility of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN therapy was assessed as the proportion of manufacture failures, defined as the inability to produce the minimum product amount required for infusion, and the proportion of subjects who received lower than protocol-specified dosing.

Safety and feasibility data were summarized descriptively by cohort and combined. Proportions and 95% exact confidence intervals were provided when appropriate. Clinical response was assessed by the proportion of patients achieving ≥ 30% decline in serum PSA from baseline (PSA30), as well as by radiographic response per PCWG2 criteria. Descriptive statistics including mean, median, interquartile range (IQR) and range were produced for quantitative measures of persistence and cytokine levels. The relationship between CRS grade and maximum fold change from Day 0 pre-infusion to post-infusion in seven cytokines/soluble mediators (IFNγ, IL-6, IL-2, sIL-2R, IL-8, IL-10, GM-CSF) were examined by boxplots and heat maps.

For NanoString DSP analyses, hierarchical clustering of ROIs was done using the R package ComplexHeatmap81 using Z-scores of log2 protein expression. Differential expression across regions of tumor (n = 90) or T-cell-enriched stroma (n = 22) was done using a linear mixed-effects model via the R package lme4 1.1–27.182 to account for experimental batch and within-patient sampling. For each protein, the log2 expression was regressed with time point (2 levels: pre- versus post-treatment) and experimental batch (2 levels) as fixed effects and patient identity (4 levels) as a random effect. P values were estimated using a likelihood ratio test via the R package lmtest 0.9–38. Significance at a false discovery rate of 5% was estimated using the Bioconductor package qvalue (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/qvalue.html) after confirming that null P values followed a Uniform (0,1) distribution.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1. Knockout of the endogenous TGFβRII in CART-PSMA cells enhances in vivo prostate tumor control independently of T cell proliferative capacity, early memory differentiation or inhibitory phenotype.

(a) Schema of CAR T cell transfer into prostate tumor (luciferase-expressing PC3 cell)-engrafted mice. (b) Longitudinal bioluminescent tumor burden of PBS or CAR T cell treated mice (n = 6). Error bars depict s.e.m. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test between the two CAR T cell treated groups at day 52 post-tumor injection. (c) Violin plots showing the absolute counts (d) memory and (e) inhibitory phenotypes of CART-PSMA-AAVS1KO or CART-PSMA-TGFβRKO cells in the peripheral blood of mice at the peak of T cell expansion (day 48). Thick dashed lines indicate the median and thin dotted lines show the first and third quartiles. P values were determined with a two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Transgenic expression of TGFβRDN significantly increases the proliferative capacity, but not the effector function of CART-PSMA cells compared to knockout of the endogenous TGFβRII.

(a) Efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout (KO) of the endogenous TGFβRII (TGFβRKO) in CART-PSMA cells derived from n = 4 different subjects, as determined by Sanger sequencing and TIDE analysis. Editing efficiency is presented relative to AAVS1 knockout in donor-matched CART-PSMA cells. Error bars depict the SEM. (b) Representative flow cytometry showing levels of pSMAD2/3 in CART-PSMA cells with knockout of AAVS1, TGFβRII or co-expression of TGFβRDN that were unstimulated or stimulated with recombinant human TGFβ (representative of 3 independent experiments). (c) Expansion capacity of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN versus CART-PSMA-TGFβRKO cells following serial re-stimulation (indicated by black arrows) with TGFβ-expressing irradiated PC3 prostate tumor cells. Proliferation is presented as a change in fold expansion over the longitudinal growth of stimulated CART-PSMA-AAVS1KO cells. Cells were manufactured from 4 different subjects, with pooled data from 3 independent experiments. Error bars depict the s.e.m. P values were calculated using a two-tailed t-test. (d) Killing kinetics of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN, CART-PSMA-TGFβRKO and CART-PSMA-AAVS1KO cells co-cultured with PC3 tumor targets. CAR T cells directed against CD19 (irrelevant CAR) served as a negative control. Data are representative of 3 individual experiments performed with engineered T cells from 3 independent subjects. Error bars indicate the s.e.m. (e) Cytokine production from CART-PSMA-TGFβRKO and CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN compared to control CART-PSMA cells following stimulation with PC3 cells. Each data point represents a CAR T cell sample derived from an independent donor. Error bars depict the s.e.m. P values were calculated with a two-tailed t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Characterization of baseline apheresis products and preinfusion TGFβRDN expressing PSMA-directed CAR T cells (CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN).

(a) Frequencies of apheresed CD45+, CD45+CD3+, CD45+CD3+CD4+, CD45+CD3+CD8+ cells and CD28+ T cells were assessed by flow cytometry. (b) Proportions of various CD3+CD8+ T cell subsets at the time of apheresis are shown: naive-like, CD27+CD45RO−; central memory, CD27+CD45RO+; effector memory, CD27−CD45RO+; effector, CD27−CD45RO−. (c) Percentages of FoxP3+CD25+ regulatory T cells in apheresis material. (d) CD4:CD8 cell ratio in the pre-infusion CAR T cell product is depicted. (e) Fold expansion of CAR T cell infusion product over 9-days of clinical manufacturing is shown. (f) Frequencies of expanded patient CD3+CD45+ T cells expressing the anti-PSMA CAR and TGFβRDN are plotted. Individual data points for each patient and means (denoted by a black horizontal line) are shown in panels a-f. (g) Expression of a TGFβRDN on manufactured PSMA-targeted CAR T cells prevents TGFβ signaling through SMAD2/3 phosphorylation. Individual data points for each patient and means are shown in all panels. IL-2 denotes patient products manufactured in the presence of this cytokine; IL-7/15 indicates CAR T cell manufacturing using these cytokines. Thick dashed lines in violin plots depict the median and thin dotted lines indicate the first and third quartiles. P values were determined with a two-tailed Student’s t-test for paired samples.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Longitudinal cytokine, chemokine and growth factor profiles in the peripheral blood of mCRPC patients treated with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells.

Fold changes in serum cytokine, chemokine and growth factor levels from baseline (preCAR T cell infusion) to each time point postCART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell administration were measured in patients by multiplex analysis and are depicted as line graphs.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Antitumor responses and clinical outcomes in subjects infused with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells.

(a) Spider plot showing longitudinal serum PSA changes in patients treated with CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells. (b) Overall survival (OS) and (c) progression-free survival (PFS) graphed as Kaplan-Meier estimates for all patients. The x-axis is shown in months. Tick marks indicate each censored subject (that is, patients who are alive at the data cutoff point).

Extended Data Fig. 6. Analysis of CAR lentiviral integration sites in mCRPC and advanced leukemia patients.

(a) The word clouds illustrate CAR-PSMA-TGFβRDN lentiviral integration sites near genes of the most abundant clones from each Patient 9 sample, where the numeric ranges represent the upper and lower clonal abundances. (b) The relative abundances of cell clones are summarized as stacked bar plots. The different bars in each panel denote the major cell clones, as marked by integration sites where the x-axis indicates timepoints and the y-axis is scaled by the proportion of total cells sampled. The top 10 most abundant clones have been named by the nearest gene while the remaining sites are grouped as low abundance. The total number of unique sites are listed above each plot. (c) This panel displays the frequency of NELL2- and GLCCI1-disrupted clones observed at each timepoint across advanced leukemia patients treated with CD19 CAR T cells. The size of the points indicates the number of clones observed at the same timepoint and sharing the same abundance. (d) The distribution of integrated pro-vectors across NELL2 and GLCCI1. Each row of lines and boxes indicates a different splice variant of the transcription unit (5 for NELL2 and 1 for GLCCI1). The points indicate the observed integrated pro-vectors. The color of the points indicates the orientation of the integrated element. Points were displaced vertically for aesthetics, as the vertical distances between points hold no value.

Extended Data Fig. 7. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutagenesis of NELL2 and GLCCI1 does not alter the proliferative capacity of CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells.

(a) Efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9-induced mutagenesis of NELL2 and GLCCI1 in CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells from n = 4 different individuals, as assessed by Sanger sequencing and TIDE analysis. Knockout (KO) effectiveness is shown relative to AAVS1 in subject-matched CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells. (b) In vitro proliferative capacity of CRISPR/Cas9-edited CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells (n = 4 independent donor samples) following serial restimulation (indicated by black arrows) with irradiated PC3 prostate tumor cells. Error bars indicate the s.e.m. (c) Antigen-dependent fold expansion of AAVS1 and GLCCI1 KO CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells in the presence or absence of dexamethasone (DEX; E-4M). Box plots show minimum, lower quartile, median, upper quartile and maximum (n = 6 biologically independent samples).

Extended Data Fig. 8. In vitro assessment of Patient 9 CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell transformation.

(a) Assessment of proliferation and (b) viability of Patient 9 CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cells (derived from the CAR T cell infusion product and day 28 postinfusion PBMC) under cytokine- and stimulation-free conditions. T cells from an unrelated donor transformed with an NPM-ALK fusion kinase were cultured in parallel as a control. (c) Absolute cell counts and (d) viability measurements of the same day 28 cells from Patient 9 above that were stimulated in the presence of anti-CD3/CD28 agonistic antibodies and IL-2 (untransduced = not transduced with NPM-ALK). The patient’s cells were transduced with a lentivirus encoding NPM-ALK and cultured separately as a control for transformation.

Extended Data Table 1.

Study-related SAEs following CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion

| SAE Grade | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 2 (n = 3) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Cytokine Release Syndrome (CRS) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Syncope | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Acute Kidney Injury | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cohort 3 (n = 1) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Anemia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepatic Failure | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cytokine Release Syndrome | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Acute Kidney Injury | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Respiratory Failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cohort −3 (n = 6) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Cytokine Release Syndrome | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Upper Respiratory Infection | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Renal and Urinary Disorders - Other (SIADH*) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoxia | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypotension | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Syndrome of innaproriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

Extended Data Table 2.

Individual patient SAEs following CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN cell infusion

| Subject ID | Cohort | CART-PSMA-TGFβRDN Cell Attribution | Toxicity | Grade | Duration (Days) | Time from Infusion to Event (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 2 | 1 | Unrelated | Hematuria | 4 | 52 | 26 |

| Patient 5 | 1 | Unrelated | Hip fracture | 3 | 2 | 14 |

| Patient 6 | 2 | Definitely | Cytokine release syndrome | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Probably | Encephalopathy | 3 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Possibly | Syncope | 3 | 1 | 17 | ||

| Possibly | Acute kidney injury | 3 | 3 | 30 | ||

| Patient 7 | 2 | Definitely | Cytokine release syndrome | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Probably | Hypotension | 3 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Patient 8 | 2 | Unrelated | Urinary tract infection | 3 | 7 | 26 |

| Patient 9 | 3 | Definitely | Cytokine release syndrome | 4 | 9 | 0 |

| Probably | Hypotension | 4 | 8 | 1 | ||

| Probably | Respiratory failure | 4 | 28 | 2 | ||

| Possibly | Anemia | 3 | 26 | 4 | ||

| Possibly | Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 3 | 26 | 4 | ||

| Probably | Acute kidney injury | 4 | 24 | 6 | ||

| Probably | Hepatic failure | 3 | 24 | 6 | ||

| Unrelated | Sepsis | 5 | 10 | 20 | ||

| Patient 11 | −3 | Definitely | Cytokine release syndrome | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Probably | Hypoxia | 3 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Patient 12 | −3 | Definitely | Cytokine release syndrome | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| Patient 14 | −3 | Definitely | Cytokine release syndrome | 1 | 3 | 25 |

| Possibly | Renal and urinary disorders - other (SIADH) | 3 | 5 | 26 | ||

| Patient 17 | −3 | Possibly | Hypotension | 3 | 2 | 9 |

| Possibly | Upper respiratory infection | 3 | 5 | 9 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements