Abstract

Aims:

To examine how female sex worker’s motivations, desires, intentions, and behaviors towards childbearing and childbearing avoidance inform their contraceptive decision-making. We explored the influence of social determinants of health in the domains of social context (sexual partners, experiences of violence), healthcare access, economic instability on the contraceptive decision-making process.

Design:

We conducted a qualitative descriptive study informed by Miller’s Theory of Childbearing Motivations, Desires, and Intentions through the lens of social determinants of health.

Methods:

Participants were recruited from a parent study, EMERALD, in July-September, 2020. Data were collected from 22 female sex workers ages 18–49 using semi-structured 45-to-60-minute audio-recorded interviews and transcribed verbatim. Theory guided the development of the study’s interview guide and thematic analytic strategy.

Results:

Five themes emerged related to contraceptive decision-making: Motivations (value of fatherhood), Desires (relationships with love), Intentions and Behaviors (drugs overpower everything, contraceptive strategies, and having children means being a protector). Women’s contraceptive decision-making often included intentions to use contraception. However, social determinants such relationships with clients and intimate partners, interpersonal violence, and challenges accessing traditional healthcare offering contraceptive services often interfered with these intentions and influenced contraceptive behaviors.

Conclusion:

Women’s contraceptive decision-making process included well-informed desires related to childbearing and contraceptive use. However, social determinants across domains of health interfered with autonomous contraceptive decision-making. More effort is needed to examine the influence of social determinants on the reproductive health of this population.

Impact:

Findings from this study build on existing research that examines social determinants impacting reproductive health among female sex workers. Existing theoretical frameworks may not fully capture the influence constrained reproductive autonomy has on contraceptive decision-making. Future studies examining interpersonal and structural barriers to contraception are warranted.

Patient or Public Contribution:

The parent study, EMERALD, collaborated with community service providers in the study intervention.

Keywords: Sexual health, reproductive health, violence, decision-making, inequalities in health, nursing

Introduction

Reproductive health inequities are experienced by sex workers around the world (Schwartz and Baral, 2015). Nearly 60% of female sex workers (FSW), defined as cisgender women who exchange sex for goods, drugs, or money, experience an unintended pregnancy (Bowring et al., 2020). Sex work often involves high coital frequency among a reproductive aged population of women, thereby increasing risks for pregnancy if contraceptive methods are inconsistently or incorrectly used. FSW who sell sex through street-based settings (soliciting and meeting clients on the street in public places) are a population of women who have unique adversities characterized by challenges to accessing quality healthcare as well as navigating complex social marginalizations. These social determinants of FSW health can increase vulnerabilities to unintended pregnancy risk factors (Zemlak et al., 2020). Globally, sex workers experience high rates of unintended pregnancies yet there has been little attention given to how social determinants of health (SDOH) influence contraceptive decision-making among this highly marginalized population.

Leading public health organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) describe SDOH as conditions contributing to health inequities (World Health Organization, 2017). Broad, accepted categories of SDOH can include economic stability or employment, healthcare access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, education access, and the social context in which groups live, work, and play. Specific to sex work, SDOH are complex and often driven by stigmatization and social exclusion because the industry is outlawed or unregulated in many countries (Schwartz and Baral, 2015). In this paper, we focus on the SDOH that are most pernicious in the lives of sex workers that may influence contraceptive decision-making: social context (sexual partners, experiences of violence), healthcare access, economic instability.

Contraceptive decision-making is a proactive and intentional strategy woman across the spectrum of social positions use to manage the occurrence and timing of pregnancies (Downey et al., 2017). The goal is to avoid unintended pregnancies that can affect their health and well-being in the short and long-term, and the type of contraceptive method women decide to use has an important role. The contraceptive methods women choose to use vary in their efficacy to prevent pregnancy as well as women’s ability to control the use of the method with or without male partner cooperation. Partner controlled contraception (PCC) are methods such as condoms or withdrawal that require a male partner’s cooperation for use; efficacy varies if methods are incorrectly or inconsistently used with each sex act. Over 65% of FSW rely on PCC (Zemlak et al., 2020). Fewer FSW use female-controlled contraception (FCC) which are highly effective, coital independent, and offer women discrete control over their use without the male partner’s cooperation. Use of FCC methods such as intrauterine devices, implants, injections, and birth control pills has resulted in declining rates of unintended pregnancies in the previous decade (Kavanaugh and Jerman, 2018). However, these statistics mask rates of unintended pregnancy among populations of marginalized women such as FSW who often have higher than average unintended pregnancy rates and continue to experience unintended pregnancy despite declining trends (Schwartz and Baral, 2015). The SDOH factors associated with contraceptive decision-making and the selection of FCC or PCC by FSW have not yet been investigated.

The emphasis in prior research has been individual-level influences on contraceptive decision-making such as knowledge and beliefs about methods. For example, increased knowledge about contraceptive methods is associated with use of more effective FCC (Melbostad et al., 2020). Among marginalized populations such as FSW, broader SDOH such as healthcare access and social and work environments might impact reproductive autonomy and the contraceptive decision-making process (Zemlak, et al., 2020; Schwartz and Baral, 2015). Social factors such as relationship contexts with different types of sexual partners (clients and intimate partners), interpersonal violence, healthcare access, and economic instability may have important implications on health outcomes such as contraceptive decision-making and unintended pregnancy (Zemlak et al., 2021). A deeper understanding of the contraceptive decision-making process and how these SDOH impact this process may provide an understanding of how to reduce inequities in FSW experiences of unintended pregnancy.

Background

Contraceptive decision-making is a process that involves conscious and unconscious motivations, desires, intentions, and behaviors that influence childbearing (Alexander et al., 2019; Miller, 1994). This decision-making process informs women’s selection of FCC or PCC to prevent unintended pregnancies. Among FSW, this decision-making process might be influenced by the SDOH related to sex work such as overlapping relationships with different sexual partners, experiences of violence, healthcare access, and economic instability (World Health Organization, 2017; Zemlak et al., 2020). Sex work is an industry that involves unique social contexts and is associated with working conditions that can impinge healthcare access and may influence the contraceptive decision-making process.

Social contexts may have an important role in FSW’s contraceptive decision-making. For example, contraceptive decision-making can be influenced by sexual relationships which are complex and fluid throughout a woman’s life. FSW may have many different types of sex partners with varied relationship contexts. Sexual partnerships among FSW can include intimate partners (sex partner for whom there is no monetary exchange for sex acts) and client partners (sexual partner who pays for sex with food, drugs, money, shelter, or goods) that add to the complexity of contraceptive decision-making (Zemlak et al., 2021). The nature of sex work often requires substantial rapid overlap of sexual encounters within short time periods, differentiating FSW from women in other types of sexual relationships and necessitating examination of contraceptive decision-making in these circumstances. Previous contraceptive decision-making studies within a marital dyad or while women were casually dating might be less applicable among FSW who have simultaneous relationships that consist of different sexual partner types (Ulibarri et al., 2019). Contraceptive decision-making among FSW may change according to sex partner type (Duff et al., 2015). For example, a FSW might engage in condomless sex with intimate partners, that might include emotional ties, to show closeness, trust, or a desire for childbearing. However, she might choose to use condoms with clients for pregnancy prevention because she has no emotional ties to that person. Thus, the social context of relationship type (client, intimate partner) may be an important SDOH influencing FSW’s contraceptive decision-making.

Violence perpetrated by sex partners can affect economic stability and often occurs within a neighborhood environment where other dangers are present. Thus, violence is a SDOH that can be associated with these contraceptive decisions and play a role in women’s childbearing intentions and behaviors (Zemlak et al., 2021). FSW experience high rates of interpersonal violence (physical or sexual violence) and condom coercion (partner removal or refusal to use a condom) by multiple partner perpetrators (Decker et al., 2020); prevalence of lifetime violence by clients 58% and intimate partners is 52% (Decker et al., 2020; Zemlak et al., 2021). Cumulative, lifetime experiences of violence influence how women make contraceptive decisions because women who experience interpersonal violence may not have the ability to safely execute their contraceptive intentions with actual behaviors (Alexander et al., 2012). For example, a woman with intentions to avoid pregnancy may decide to use PCC such as condoms with each coital act to prevent pregnancy. A violent partner’s refusal to use PCC may result in experiences of unintended pregnancy. Lifetime experiences of violence and contraceptive method failures, thus, can become part of a woman’s contraceptive decision-making journey (Downey et al., 2017). As a result, women with lifetime experiences of interpersonal violence are more likely to use covert FCC such as intrauterine devices, pills, injections, or implants that do not require a partner’s cooperation to avoid pregnancy in relationships where they cannot safely execute their contraceptive intentions into behaviors (McDougal et al., 2020; Zemlak et al., 2021). The patterns of violence experienced from clients or intimate partners, can influence what types of contraceptives FSW use, therefore understanding how violence influences contraceptive decision-making is vital among FSW.

Healthcare access and economic stability are important SDOH to consider among FSW as many FSW may have challenges accessing healthcare systems that provide contraceptive services. Economic instability may impede access to insurance, payment for medications, or transportation to medical visits necessary for most FCC. Globally, sex workers report stigma as a barrier to accessing healthcare or discussing the reproductive health risks associated with selling sex (Schwartz and Baral, 2015). Women may feel a fear of negative treatment related to disclosing sex work to healthcare provider (Schwartz and Baral, 2015). Both stigma and fear can be deterrents to accessing healthcare for contraceptive counselling. Contraceptive decision-making can be impacted as women can use PCC such as condoms without accessing healthcare providers which is necessary for most FCC methods. The unique SDOH involved in the street-based sex trade, such as economics and stigma influencing healthcare access, and how these factors impact contraceptive decision-making among FSW warrants further study.

THE STUDY

Aims

Our study aimed to gain insights into the motivations, desires, intentions, and behaviors related to contraceptive decision-making. We examined how SDOH (social context, healthcare access, and economics) influence this decision-making process.

Theoretical Framework

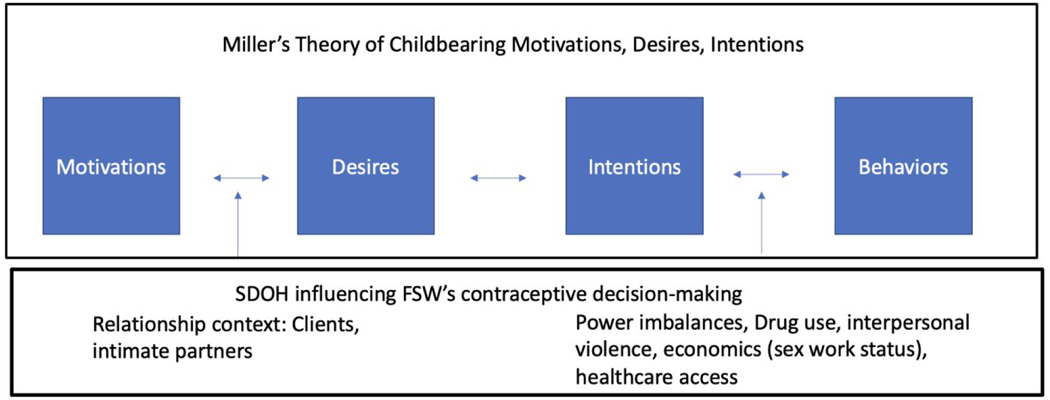

Our study examining contraceptive decision-making is guided by Miller’s Theory of Childbearing Motivations, Desires, and Intentions. This theory examines conscious and unconscious factors that might be important to the contraceptive decision-making process. The contraceptive decision-making process is comprised of four domains involving motivations, desires, and intentions towards childbearing that inform women’s contraceptive decisions (Miller, 1994). We use this theory through the lens of SDOH due to the social position of sex workers in our society. Using our theoretical framework, we describe contraceptive decision-making and uncover the social context, healthcare access, and economic SDOH that might influence contraceptive decision-making in our sample of FSW.

Design

We used a qualitative descriptive study design to gain deeper understanding of women’s experiences with the contraceptive decision-making process (Sandelowski, 2000). The semi-structured interview guide was informed by Miller’s theory and included broad questions to examine FSWs experiences related to the components contraceptive decision-making process (motivations, desires, intentions, and behaviors) (see table 1). Prompts in the interview guide explored contraceptive decision-making processes across the domains of Miller’s theory and examined influences of social context (sexual partners, experiences of violence), healthcare access, economic instability across these components of decision-making.

Table 1.

Sample of questions from the semi-structured interview guide

| Theoretical Concept | Interview Guide Questions | Examples of prompts related to SDOH* |

|---|---|---|

| Motivations | • Tell me about a time when avoiding pregnancy was very important to you and why? • Tell me about your experiences from your upbringing related to having children? |

• Tell me about people in your life. • What makes you decide how to use contraception with clients? Your regular partner? |

| Desires | • Imagine for a moment you were to get pregnant now, how would you feel and why? • How has trading sex changed how you think about pregnancy? |

• Tell me about how your experiences with family or friends impacted your desires for children. |

| Intentions | • What kind of conversations have you had with (partner type) about pregnancy? | • How did your relationships with partners (clients or regular partners) impact your contraceptive decisions? • Tell me about a time when you experienced violence by (partner type). How did that experience impact your thoughts or plans around pregnancy? |

| Behaviors | • Have partners kept you from using a birth control method in the past? • How do you use contraception with clients? With your intimate partner? • What strategies have you used, or might you use to avoid pregnancy if partners are refusing to use condoms? |

• How do you access contraception in Baltimore City (blinded for peer review)? • What have been your experiences talking with a healthcare provider about contraception? |

Social Determinants of Health

Sample/Participants

Participants were recruited from a parent study, EMERALD, a longitudinal cohort study among cis-gender female (people born as female who identify as women), street-based sex workers in a large city in the Eastern United States. The EMERALD study recruited 385 FSW between 2017 and 2019 using targeted sampling to identify times and places where sex work was likely to occur using solicitation and arrest data, primary data collection with windshield surveys, and key informant input (Silberzahn et al., 2021). Parent study participants participated in quantitative surveys every six months for 18 months after their initial recruitment. EMERALD inclusion criteria were as follows: a) age 18 or older; b) assigned female sex at birth and identify as a woman; c) exchanged sex for money, goods, or drugs in Baltimore City 3 times in past 3 months; d) willing to undergo testing for HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia; and e) willing to provide locator information. Exclusion criteria were as follows: a) inability to provide written consent in English; b) too cognitively impaired by alcohol or drugs to complete the study survey; and c) enrolled in a previous cohort study among street-based sex workers in the same city.

Participants were eligible for inclusion in this qualitative study if they: a) were part of the EMERALD parent study cohort; b) were aged 18–49; and c) were willing to participate in one interview. Participants were read an Institutional Review Board approved oral consent form. After providing verbal consent, participants were enrolled in this study.

Data Collection

For this study, we used purposive sampling by screening EMERALD baseline survey responses to select participant with a range of contraceptive methods. Contraceptive methods were coded in the EMERALD data and classified for this study as: PCC (none, male condom, withdrawal) and FCC (female condom, birth control pill, patch or ring, Norplant/Implanon, injection (Depo-Provera), IUD, tubal ligation, and/or Plan B). Women using “none” were considered using PCC as their male partner could use condoms or withdrawal without a woman’s input. Data collection for this qualitative study occurred in July-September 2020 and interviews were conducted by telephone. Contraceptive method use was determined through review of baseline parent study data and confirmed by questions in the qualitative interview to assess whether participants changed their contraceptive method type from the baseline survey data collection. Interviews were conducted by the lead author (JZ), lasted 45 minutes to one hour, and were audio-recorded. When interviews were scheduled, women were encouraged to participate in a way that felt safe for them (i.e., wearing headphones, selecting a private location) owing to the sensitive and potentially triggering nature of the topic. We concluded study enrollment when we reached thematic saturation and had representation of women with FCC and PCC method use.

The PI kept detailed memos after each interview describing findings and potential themes; we reached thematic saturation when findings were repeated across many interviews. We also used an iterative coding process during the data collection phase, applying a priori coded domains from Miller’s Theory and influences of SDOH to the data as well as identifying emerging codes. When no new additional codes were emerging (about interview #20) and we had sufficient data to support the defined domains from Miller’s Theory and influences of SDOH, we determined we had reached saturation. To thank women for their time and participation in this study, we mailed a $50 Visa gift card and a study approved community resource list of supportive services.

Completed audio recordings were sent for professional transcription. Audio data recordings of interviews as well as transcripts were stored on a secure university server. When transcripts were received, they were checked against the audio recordings for accuracy and completeness by (JZ). All transcripts were de-identified.

Ethical Considerations

Confidentiality and data security were carefully monitored and Institutional Review Board approval through the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Data analysis

The transcripts were independently coded by two investigators (JZ and DW) using a thematic analysis approach to understand the iterative, non-linear process for contraceptive decision-making. An a priori codebook was developed based on the theoretical framework of this study. Coders organized data using MaxQDA software during the coding process. The code names and definitions were included in the codebook and reviewed prior to analysis by both coders. Close reading of transcripts allowed for identification of emergent, in vivo codes from the data. When in vivo codes were developed, coders added them to the codebook in MaxQDA with a coding definition memos.

The analysis team categorized and collapsed codes that were conceptually aligned and came to consensus around themes. Themes were then arranged in a spreadsheet and defined, linking each to the theoretical framework, influence of SDOH, and exemplar participant quotes. After compiling themes, the research team developed interpretations based on the study’s theoretical underpinnings and examination of how SDOH influenced contraceptive decision-making across domains.

Rigour

Procedures were in place to ensure trustworthiness of our findings. The 32-item consolidated criteria for reported qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was utilized as a reporting guideline. We ensured credibility in our findings through regular co-author review throughout our analyses. We included participants’ words through quotations in our results. Trustworthiness was assured in our data collection and analysis procedures through use of reflective memos during data collection inclusive of insights after the interview. The reflexive approach used throughout the research process considered positionality (PI is a white, cisgender woman, and nurse), knowledge, and assumptions. Dependability was ensured through documentation of using memos detailing our coding decisions, disagreements, and reconciliations.

FINDINGS

Participant Characteristics

Twenty-two women participated in the study (see table 2). Every participant reported a lifetime sexual relationship with a client and male intimate partner(s). Twenty women identified their race as white. At the time of the interview, 12 women used FCC and 10 women used PCC (male condoms). Six women were actively engaged in sex work at the time of our interview. The remaining 16 women reported exiting sex work between 2 weeks-2 years preceding the interview. The parent study was longitudinal, and all women were actively engaged in sex work during the baseline survey with some women exiting sex work at various times during the parent study. While some women can permanently exit sex work, a cyclical exit and re-entry is common (Dinse and Rice, 2021). We asked women during interviews to reflect upon contraceptive decision-making while actively engaged in sex work.

Table 2.

Participant Demographics and Descriptions

| Participant study ID | Age | Current contraceptive method | Sex worker status | Interpersonal violence experiences by perpetrator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 1 | 39 | FCC (Tubal) | Current | Client violence |

| 2 | 35 | PCC | Current | Client and intimate partner violence |

| 3 | 39 | FCC (Tubal) | Clients 2 years | Client violence |

| 4 | 45 | FCC (Tubal) | Current | Client and intimate partner violence |

| 5 | 31 | PCC | Clients 7 months ago | Client and intimate partner violence |

| 6 | 27 | FCC (Nexplanon) | Clients 1 year ago | Client and intimate partner violence |

| 7 | 32 | PCC | Clients 1 month ago | Client and intimate partner violence |

| 8 | 35 | PCC | Clients 11 months ago | Client and intimate partner violence |

| 9 | 31 | PCC | Client 8 months | Intimate partner violence |

| 10 | 35 | PCC | Client 1 year ago | None |

| 11 | 25 | FCC (Nexplanon) | Client 1 year ago | Intimate and client violence |

| 12 | 39 | PCC | Current | Client and intimate partner violence |

| 13 | 39 | FCC(Depo) | Clients 11 months ag | Client violence |

| 14 | 33 | FCC(Depo) | Clients 18 months ago | Intimate partner violence |

| 15 | 28 | FCC (Birth control pill) | Clients 18 months ago | Client violence |

| 16 | 30 | FCC (Nexplanon) | Clients 1 year ago | Client violence |

| 17 | 24 | FCC (Depo) | Clients 2 years ago | Intimate partner violence |

| 18 | 40 | PCC | Clients 18 months ago | Client violence |

| 19 | 39 | FCC (Tubal) | Clients 3 months ago | Client violence |

| 20 | 42 | PCC | Current | Client and intimate partner violence |

| 21 | 42 | FCC (IUD) | Clients 2 years ago | Client violence |

| 22 | 34 | PCC | Current | Client violence |

Note. Race was not included as only 2 women identified as a race other than white. FCC: Female controlled contraception. PCC: Partner controlled contraception

Themes in the Contraceptive Decision-making Process and SDOH Influencers

Five themes emerged as drivers of contraceptive decision-making among the FSW participants: value of fatherhood, relationships with love, drugs overpower everything, contraceptive strategies, and having children means being a protector. We identified that SDOH are influential at various points in the contraceptive decision-making process as displayed figure 1.

Figure 1. Miller’s Theory of Childbearing Motivations, Desires, and Intentions among FSW: The Influence of Social Determinants of Health.

Note: FSW (Female Sex Workers); SDOH (Social Determinants of Health)

Motivations

Miller’s Theory describes motivations for childbearing to be related to unconscious traits that propel women towards or away from childbearing. These motivations can be shaped and developed across a woman’s lifetime. These unconscious motivations in Miller’s theory shape later components of the decision-making sequence towards contraceptive behaviors. We identified one theme that aligned with motivations: value of fatherhood. SDOH, specifically the social context of having clients and intimate partners, influenced how women considered the role of fatherhood.

Value of fatherhood.

Women described the importance of the role of fathers in childbearing motivations. Women’s experiences in their own family dynamics shaped the importance of having a father for their children. Women assessed the type of sexual partner as an important motivator for childbearing and childbearing avoidance. For example, clients were viewed as unstable and transient relationships and were unlikely to have a participatory role in fathering children. Thus, clients were undesirable for childbearing:

You don’t know this person. You don’t know if you are ever going to see them again. You don’t know if they would be in the child’s life or even if you would want them to be in the child’s life. You don’t know this person, you don’t know their history, their background, nothing. (Participant 15)

The transient nature of the client relationship for this participant meant that pregnancy by that sexual partner would not be associated with a father being an active relationship or known entity in children’s lives. The client partner was lacking stability, certainty, and consistency that this woman valued as traits in a father for her children.

Other participants rebuffed childbearing with clients due to the shame associated with sex work and economic instabilities that underpinned their participation in the life:

The whole pregnancy, I think you will be reminded of a dark place that you were, and what you had to do to survive.. you don’t know this person (client), you don’t know their history, you don’t know who they are (Participant 15).

This participant engaged in sex work to survive. Sex work behavior was driven by economic instability and becoming pregnant by an unknown client partner was potentially a re-traumatizing experience for women. There was a sense of shame and stigma associated with having children fathered by client partners because it would be a reminder of a challenging time in women’s lives.

The identity of a father was important for women when they considered childbearing. Having a father in children’s lives was highly valued as a form of support and identity for children:

[I don’t know] If they would even know who their dad was or if I even knew who the dad was. Just because I didn’t have a father growing up, so I wanted my children... my kids to know who their dad was. (Participant 4)

This participant’s father was not involved in her upbringing, so lack of parental engagement by a client partner in children’s lives would be a deterrent to pregnancy with these types of sexual partners. Her own childhood experiences motivated her towards childbearing with partners who might have a role in children’s lives.

While involved in sex work with clients, participants were often in overlapping relationships with intimate partners. In contrast to clients, intimate partners were often desirable childbearing partners because women viewed more stability in that relationship; those partners might have a role in fathering children:

A relationship means understanding as far as children.. that’s what matters.. He needs to be able to have a relationship with the child. (Participant 9)

I feel like if it was (getting pregnant) by my current sex partner, we would be disappointed that it happened too early, but we would still accept it happened and be parents, but if it was with someone else (a client) I don’t know how I would feel about it (Participant 17)

For these participants, the decision to consider childbearing was associated with a partner’s potential ability to build a loving relationship with a child. The foundations with intimate partners would facilitate building this relationship with their child. This trait, valuing fatherhood, informed later steps in the desires, intentions, and behaviors process of contraceptive decision-making among this population.

Desires

The desires component of the Miller’s Theory describes women’s conscious decision-making regarding their goals and objectives around childbearing and childbearing avoidance. One theme that aligned with the desires component of the Miller’s Theory: relationships with love. Participants described specifically the desire for childbearing in relationships that were based in love. Contraceptive decision-making varied based on the love and trust present or absent in sexual relationships. The nature of sex work, often involving sex with different partner types with varied emotional ties, is a unique SDOH among FSW that influenced the contraceptive decision-making process.

Relationships with love.

Women described the importance of relationship contexts with partners in shaping desires for childbearing. Desiring pregnancy with an intimate partner was a way to show love with this partner, differentiating the relationship from client partners: Yeah, uh, (I use a) condom with everybody but the man I’m in love with. (Participant 12). Feeling love for her intimate partner resulted in contraceptive decision-making that varied between sexual partner types due to a desire for pregnancy with intimate partners.

Another participant described her feelings if she became pregnant by a client as “horrible because that’s not somebody I would want to spend my life with. And that’s my goal” (Participant 10). Her goal for childbearing was to have an interpersonal, loving relationship with the father. When that loving interpersonal relationship was absent, for example with client partners, women described feeling a desire to avoid pregnancy with those partners:

I use condoms with clients.. (when referring to her intimate partner).. I should keep using them (condoms) but I might not. Maybe cause it’s special and you’re in love. (Participant 1)

This participant used condoms with her clients because there was no love in those relationships. However, with her intimate partner, she felt a close interpersonal connection that made her consider childbearing with this partner and thus did not desire to use condoms with this partner.

Some women described close, loving relationships with intimate partners and planned pregnancy with their intimate partners while avoiding pregnancy with their clients. Participants described using condoms as a contraceptive method to allow flexibility between sexual partner types and pregnancy planning:

No my boyfriend we didn’t use them (condoms). Getting pregnant with him was different... our twins were planned babies. (Participant 11)

Women described use of PCC with male condoms to allow for flexibility in planning pregnancy with intimate partners with whom they were in a loving relationship and avoiding pregnancy with client partners.

Intentions and Behaviors

Women’s descriptions of childbearing desires with intimate partners were consistent among participants and conveyed women perceived reproductive autonomy over those choices. The examination of the intentions and behaviors components of Miller’s Theory, considered separate domains, highlighted the SDOH (interpersonal violence, substance use, economic instability, and healthcare access) that impacted women’s autonomy over contraceptive decision-making.

The intentions component of Miller’s Theory represents the psychological state of what a woman plans to do related to childbearing and their intention of which contraceptive method (i.e. FCC or PCC) they will use. For example, women might have the intention to avoid pregnancy through use of condoms with each sexual encounter. The behaviors component of Miller’s Theory includes the actual actions taken to regulate contraception. For the woman who intended to use condoms, this is the behavior of using condoms with each sex act. In some cases, women’s contraceptive intentions and contraceptive behaviors align; in other cases, barriers between intention and actual behavior were present due to confounding SDOH.

SDOH that align with the domain of social context affected women’s individual autonomy over their contraceptive intentions as well as their contraceptive behaviors. Participants described power imbalances within client and intimate relationships manifesting through drug use, condom coercion, and violence. Our analysis identified three themes aligned with the intentions and behaviors components of Miller’s Theory: drugs overpower everything, contraceptive strategies, and having children means being a protector.

Drugs overpower everything.

For many women, drug use was inextricably tied with engagement in sex work. Women who were not actively engaged in sex work at study interviews were often also in recovery from substance use. Women described using PCC while engaged in sex work but starting FCC upon exit from sex work. These women described that intentions for use of contraception and desires towards childbearing were not changed upon exit from sex work, rather changes in SDOH associated with exiting sex work (i.e., cessation of substance use, healthcare access) made aligning contraceptive use intentions with actual contraceptive behaviors possible.

While women were using drugs, intentions to avoid pregnancy often did not align with contraceptive behaviors. Drug use was a salient part of the social context, a key SDOH, of women’s lives and often complicated healthcare access. Women described how drug use often overpowered their intentions towards of childbearing avoidance and resulted in contraceptive behaviors that did not align with their desires to avoid pregnancy:

When I was prostituting, I didn’t want to get pregnant even more than I don’t want to now. Because I was using drugs, my only thought at the time was about that drug...Condoms were the most common (method) because I am not taking time to go to no doctor to get a prescription, to go to the pharmacy, you’ve got to pay for it, to forget to take it. (Participant 18)

(When referring to obtaining contraception locally) We all know where everything is. But, at the same time, I don’t think it’s a priority (obtaining FCC)... if you are an addict, it doesn’t matter. That’s the last thing on their mind... the only thing they are worried about is that high. (Participant 10)

If I really wanted it (FCC), I could have went and got it, but that was my least worries at the time. I was too worried about getting drugs. (Participant 6)

Economic instability and the need to support substance use often drove sex work behavior and influenced contraceptive decision-making. The time and effort required to earn money and obtain drugs interfered with receiving care in traditional reproductive care settings that provide FCC. Knowledge about FCC methods were not barriers to use for these participants. They did not want or intend to become pregnant. However, their ability to execute that intention to avoid pregnancy through use of FCC was impaired by drug use.

The cyclical need to meet clients multiple times per day to earn money for drug use made it difficult for women to utilize traditional health care models (primary care or gynecologists office visits) needed to access most FCC:

If they’re (FSW) taking time out to go to the doctor (to get FCC) they’re taking time off the street. That means they are missing money which is going to get them high. If we can go to a van on the corner.. and get a depo shot, a pill or something, we would do it. (Participant 18)

Many women were engaged in sex work related to substance use. Leaving the street where they worked to attend the medical appointments needed to obtain FCC was not possible for many women. Instead, women often described a preference of having contraceptive services such as mobile vans or condom distributions co-located where they worked.

In addition to substance use and economic instability, other women struggled with the logistics required for accessing traditional reproductive healthcare services. This participant describes wanting to access FCC stating “It is something I need that I don’t have.. I don’t have my insurance card and transportation is kind of messed up”(Participant 12). These health care settings require appointments, planning, transportation, and time away from earning money. Therefore, despite intentions to avoid pregnancy, behaviors were not always aligned with this intention because cycle or rhythm of drug use interfered with accessing the healthcare systems needed to obtain FCC.

Contraceptive Strategies: ‘The Pill was my best friend.’

Most women described intentions to avoid pregnancy while engaged in sex work. However, they also knew that contraceptive behaviors aligned with those intentions could be impacted by the refusal of partners to respect or acknowledge those contraceptive intentions. Participants described contraceptive methods and behavioral strategies to avoid pregnancy with coercive partners who were unwilling to use PCC methods such as male condoms:

I don’t feel it’s fair to bring a baby into our situation.. it’s not fair. I took it upon myself (to get Depo-Provera). Yeah, like there’s a backup. If you decide one day that you are not going to wear one (a condom), well there’s a backup plan (Depo-Provera) for me (Participant 14).

I’ve had people take them (condoms) off in the middle of it (and I’m) not knowing... You get done and the condom is already on the floor.. I just made sure I will take a pill. I was taking birth control... Nothing’s really 100 percent but abstinence. Condoms can break.. (the pill) was my best friend (Participant 4).

For these participants, pregnancy was not desired, but they realized client condom coercion, refusal or removal of condoms, was common. Therefore, women used FCC as a strategy and backup to partner-controlled condoms ensure that pregnancy could be avoided in these cases.

Decisions to use FCC also had economic implications because there was often an incentive for condomless sex. Using FCC provided protection against pregnancy and an ability to earn more money:

Basically, if you were taking birth control pills, if you’re on the Depo, you know you’re protected because there are a lot of people that did pay more if you’re not using condoms, but at least you know you are backed up when you’re taking birth control (Participant 15).

This participant described inconsistent use of PCC to meet her economic needs. She used her FCC method as a strategy to ensure she was able to avoid pregnancy if she engaged in condomless sex with clients.

In addition to using FCC to avoid pregnancy related to client condom coercion, women also described behavioral strategies to avoid pregnancy with clients. In instances of condom coercion by clients and pressure for condomless sex, one participant described negotiating for other sex acts that would reduce risk of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections:

Mostly, you know, because you didn’t want to do something they (clients) wanted to do or how they (clients) wanted to do it and you know kind of getting aggressive with you...I tried new options., like blowjobs. You know you were trying to do that (blowjobs) even though they (clients) weren’t planning on it. (Participant 13)

This participant described feeling pressured and threatened by clients to engage in sex acts that did not feel safe to her. In these instances, directed these partners to sex acts that reduced her risk to experiencing an unintended pregnancy such as oral sex.

Other women described taking both behavioral and FCC strategies in response to condom coercion or misuse by clients:

That (clients removing condoms) makes me want to keep the Nexplanon more, and then I started putting the condoms on myself (Participant 16).

This participant describes decision-making characterized by agency and autonomy when responding to condom coercion. She found a FCC method that met her needs and adjusted behaviors with clients to ensure condom protections.

Having children means being a protector.

All but one woman in the study was a mother and women expressed the importance of the role of having children in their lives. Physical and sexual violence was commonly experienced among women and was perpetrated by all sexual partner types. Violence was an important SDOH impacting women’s ability to execute contraceptive behaviors. However, only intimate partner perpetrator experiences were considered in contraceptive decisional processes among participants:

It (intimate partner violence) makes you not want to bring kids into that situation.. I put myself there... They (children) didn’t choose that. I did. Those were the choices I made. I don’t want to bring another child unto that situation (Participant 20).

This participant expressed feeling guilt about being in an abusive relationship. She takes responsibility for what she describes as a choice of remaining in the relationship. She views using FCC to better protect against future children being born into a family with violence.

Using FCC was viewed as way to protect potential children from experiencing violence by their father should a woman become pregnant by that partner. This participant described how experiences of violence by her intimate partner impacted her contraceptive method use:

It made me want to use it more (birth control) because I was scared to bring a child into a relationship where there was abuse (Participant 4).

She used FCC because she was worried any potential children she had might be threatened or unsafe with her violent intimate partner as a father. Both intimate partner violence and client violence were commonly described by participants, however intimate partners were viewed as having a likely role as a father in child’s life thus violence by these partners was influential in women’s contraceptive decisions. In contrast, clients were not viewed as threats to the safety of potential children because they would not have a role as father thus, client-initiated violence did not influence contraceptive decision-making:

I think with a regular partner as a boyfriend or something, it’s important because you don’t want to have a child with somebody really that violent. You don’t know how they would be violent toward your child if you did become pregnant...You want to make sure that you’re on birth control and you have protection because you don’t want that violence to move onto your child (Participant 15)

Having children meant protecting children and keeping them safe. This participant experienced violence by both her clients and her intimate partner. However, the violence with her intimate partner was a consistent part of the relationship. She used FCC methods to avoid pregnancy with this partner because she felt that this partner would be dangerous as a father to her children.

DISCUSSION

For FSW, contraceptive decision-making is a complex and nuanced concept that is shaped by social context, interpersonal relationships within and outside sex work, and SDOH such as interpersonal violence and access to healthcare. In a theoretical exploration of their contraceptive decision-making processes, we found that women had well-formed desires and intentions for childbearing and childbearing avoidance. However, contraceptive intentions were often not aligned with actual contraceptive behaviors due to SDOH innate to the street-based sex trade. We found that having children, fatherhood, and protection of potential children from harm were important factors in women’s contraceptive decision-making process. However, SDOH such as substance use, healthcare access, economic instability, and interpersonal violence complicated women’s autonomy over their fertility decisions.

Globally, most sex workers have children and supporting children is one reason some women sell sex (Nestadt et al., 2021). In our study, all but one woman was a had a child. The concept of having children was featured in how women described childbearing desires and resultant contraceptive-decision making. Women described a desire to create a safe, loving upbringing for children and carefully considered how their contraceptive decisions might or might not result in this type of upbringing. As a result, most women’s individual motivations and desires for childbearing were concrete and developed. However, their desires for childbearing were often interrupted due to struggles with substance use and interpersonal violence. This resulted in difficulty implementing contraceptive behaviors aligned with their desires and intentions.

This misalignment between contraceptive use intentions and contraceptive behaviors among FSW often occurred because of the gendered power imbalances permeating sex work (Thaller and Cimino, 2017). These power imbalances deepen inequities in SDOH such as economic inequities or interpersonal violence experiences, both of which can interfere with women’s contraceptive autonomy (Matjasko et al., 2013). Economic imbalances between FSW and clients or intimate partners might result in pressure for condomless sex, which may have reproductive health implications. These economic imbalances can be driven by or amplified by such factors as substance use, which was common among the current population of street-recruited FSW. Women described substance use and the need to obtain money for drugs as a reason for reliance on PCC. These methods were easy to access without stopping sex work to seek traditional medical care with a primary care provider or gynecologist (Benoit et al., 2019). Social conditions such as economic instability and inadequate access to healthcare are conditions ubiquitous to street-based sex work that impacted contraceptive method use for participants.

Although women described knowing how to access FCC, they often did not access care with these providers. Women described barriers and complexity of the healthcare system as reasons for relying on PCC (e.g. access to phones for making appointments, arranging transportation). There has been a focus on HIV risk reduction strategies among this population related to this type of structural barrier, however similar holistic reproductive health care is lacking (Schwartz and Baral, 2015). As a potential strategy to address the dual needs of substance use harm reduction efforts and reproductive care, pilot studies integrating needle exchange services and contraceptive care in a mobile van where women live and work have been well received among FSW (Moore et al., 2012). Research exploring alternative care models integrating reproductive care and harm reduction services might improve health outcomes among this vulnerable population. Bringing care to where FSW live and work may have important implications for their contraceptive behaviors.

Many participants were not able to access a type of contraception aligned with their pregnancy intentions until they exited from sex work. Exit from sex work was often associated with improved stability (i.e. transportation, access to phones to make appointments) needed to navigate the healthcare system to obtain FCC. While participants in this study all engaged in street-based sex work when recruited into the parent study, at the time of the interview more than half of women had exited sex work for a period of weeks or longer. Ten of the 17 women who exited sex work in this study reported using FCC. Their contraceptive intentions were unchanged upon exit from sex work, however factors such as improved social support and stability in their lives made aligning contraceptive intentions and actual contraceptive behaviors possible. These women’s experiences further highlight the critical need to address SDOH impacting access of medical care for marginalized populations of women.

In addition to structural barriers and economic power imbalances that impacted reproductive health, FSW are also vulnerable to physical violence, sexual violence, and condom coercion by all sexual partner types. The physical context of where women in our study solicited sex, the street, is associated with elevated rates of violence compared to indoor settings (i.e. brothels, massage parlors) (Thaller and Cimino, 2017). Thus, for street-based sex workers who wish to avoid pregnancy by using PCC with each client, the threat of violence innate to these interactions may make this an impossibility. Reducing risk of violence among street-based FSW is integral to improving reproductive health and autonomy among this population.

The illicit nature of sex work increases women’s vulnerability to violence. A recent meta-analysis found that repressive policing (where all aspects of buying and selling sex are illegal) of sex workers was associated with 3-fold increased odds of experiences of violence (Platt et al., 2018). Women, fearing arrest, may be less likely to carry condoms or rush negotiations with clients (Footer et al., 2016). Thus, if a FSW is relying on condoms, a form of PCC, to prevent pregnancy and/or HIV/Sexually Transmitted Infections, she is vulnerable to a range of negative reproductive health outcomes secondary to fear of arrest. Street-based sex workers are particularly vulnerable to policing because of the visibility of their work in the community. Reforming laws governing sex work has potential benefits reducing experiences of client violence and improving the reproductive health of FSW.

Women in our study experienced violence by clients and intimate partners; however, only violence by intimate partners was influential in how women described contraceptive decision-making. This aligns with previous research examining interpersonal violence and contraceptive method use among this population (Zemlak, et al., 2021). This finding regarding relationship context as it relates to violence and contraceptive use has important implications for clinicians providing reproductive care to this population as well as for researchers examining interpersonal violence experiences among FSW. In current clinical screening practices, some clinicians utilize the one key question method for pregnancy intention screening “Would you like to become pregnant this year?” However, this limited assessment might not fully capture the complexities of contraceptive decision-making among FSW (Baldwin Singhal R. Allen D., 2018). Women may have varied intentions between sexual partner types. For example, she may wish to be pregnant with her intimate partner but not her clients, thus answering such a question might be difficult. Additionally, women may answer that they do not wish to be pregnant this year but without additional screening for interpersonal violence and condom coercion women may not receive adequate contraceptive counseling from providers. Among women experiencing interpersonal violence, they may not be able to safely execute a PCC plan. Thus, it is critically important that reproductive care providers screen women for interpersonal violence as well as assess sexual partner types as part of contraceptive counseling visits.

We explored contraceptive decision-making among FSW using Miller’s theory through the lens of SDOH. SDOH, such as gendered power imbalances, experienced among this population had influenced the application of this theory. These power imbalances made it difficult for us to separate contraceptive intentions and contraceptive behaviors because imbalances in power in contraceptive decision-making were present for many women in our study. Women who experience power inequities, whether driven by economics or violence, may not retain full autonomy over her childbearing intentions and contraceptive behaviors. Our findings suggest inclusion of SDOH concepts such as gendered power imbalance, interpersonal violence, and health care accessibility to existing conceptual models that focus on relationship factors in contraceptive acceptability would be beneficial (Higgins and Smith, 2016). Half of FSW and a third of women in the world experience interpersonal violence a form of power imbalance with important reproductive health implications in their lifetime (CDC, 2015). Thus, expansion of current conceptual models and development of future theories are needed that explore contraceptive decision-making among populations of women experiencing gendered power imbalances.

Limitations

Our study exploring contraceptive decision-making among FSW should be considered in light of some key study limitations. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions to conducting in-person research during our study, we collected interview data by telephone. This required that our participants have access to a phone and a private space to participate in an interview. These requirements might have resulted in a sample of women with more stability in their lives than those who would have been interviewed on the street where sex work occurs. Most of the women in this study identified their race as white potentially reducing transferability to more diverse populations; studies with a more diverse sample of women are needed. These results are not generalizable to other populations in different social contexts. Our interview prompts did not examine practices such as pregnancy coercion (including questions exploring participants’ perception about the intentions of their partner to cause their pregnancy); research examining experiences of reproductive coercion among FSW is necessary.

CONCLUSION

Contraceptive decision-making is a complex process for FSW influenced by SDOH that threaten autonomous decision-making. Future research and interventions focused on integration of reproductive health care services with harm reduction services are warranted. Tailored screening and service provision focused on the unique needs and vulnerabilities of FSW are necessary to improve the health and well-being of this marginalized population. Examination of contraceptive decision-making theories inclusive of social and structural factors that constrain reproductive autonomy such as experiences of interpersonal violence and stigma is warranted.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Dr. Susan Sherman is an expert witness for plaintiffs in opioid litigation.

Contributor Information

Jessica L. Zemlak, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, 525 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21205 USA Marquette University College of Nursing, 530 N. 16th Street, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 53233 USA.

Kamila A. Alexander, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, 525 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21205 USA Department of Population, Family, and Reproductive Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States.

Deborah Wilson, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, 525 N. Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21205 USA.

Susan G. Sherman, Department of Health, Behavior and Society, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 615 N Wolfe Street, Baltimore, Maryland, 21205 USA

References

- Alexander KA, Coleman CL, Deatrick JA, Jemmott LS, 2012. Moving beyond safe sex to women-controlled safe sex: a concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 68, 1858–1869. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05881.x [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KA, Perrin N, Jennings JM, Ellen J, Trent M, 2019. Childbearing Motivations and Desires, Fertility Beliefs, and Contraceptive Use among Urban African-American Adolescents and Young Adults with STI Histories. J Urban Health 96, 171–180. 10.1007/s11524-018-0282-2 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen ST, Footer KHA, Galai N, Park JN, Silberzahn B, Sherman SG, 2018. Implementing Targeted Sampling: Lessons Learned from Recruiting Female Sex Workers in Baltimore, MD. J Urban Health 96, 442–451. 10.1007/s11524-018-0292-0 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin Singhal R Allen D,S, 2018. Optimizing Care for Women of Reproductive Age with One Key Question. Rx for Prevention 8. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit C, Smith M, Jansson M, Magnus S, Maurice R, Flagg J, Reist D, 2019. Canadian Sex Workers Weigh the Costs and Benefits of Disclosing Their Occupational Status to Health Providers. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 16. 10.1007/s13178-018-0339-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowring AL, Schwartz S, Lyons C, Rao A, Olawore O, Njindam IM, Nzau J, Fouda G, Fako GH, Turpin G, Levitt D, Georges S, Tamoufe U, Billong SC, Njoya O, Zoung-Kanyi A-C, Baral S, 2020. Unmet Need for Family Planning and Experience of Unintended Pregnancy Among Female Sex Workers in Urban Cameroon: Results From a National Cross-Sectional Study. Glob Health Sci Pract 8, 82–99. 10.9745/GHSP-D-19-00330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2015. National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2015 Data Brief-Update Release. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and. [Google Scholar]

- Decker MR, Park JN, Allen ST, Silberzahn B, Footer K, Huettner S, Galai N, Sherman SG, 2020. Inconsistent Condom Use Among Female Sex Workers: Partner-specific Influences of Substance Use, Violence, and Condom Coercion. AIDS Behav 24, 762–774. 10.1007/s10461-019-02569-7 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinse L, Rice K, 2021. Barriers to Exiting and Factors Contributing to the Cycle of Enter/Exit/Re-Entering Commercial Sex Work. Social Work & Christianity 48. 10.34043/swc.v48i2.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downey MM, Arteaga S, Villasenor E, Gomez AM, 2017. More Than a Destination: Contraceptive Decision Making as a Journey. Women’s Health Issues 27, 539–545. https://doi.org/S1049-3867(16)30089-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drescher-Burke K, 2014. Contraceptive risk-taking among substance-using women. Qualitative Social Work 13, 636–653. 10.1177/1473325013498110 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Footer KH, Silberzahn BE, Tormohlen KN, Sherman SG, 2016. Policing practices as a structural determinant for HIV among sex workers: a systematic review of empirical findings. J Int AIDS Soc 19, 20883. 10.7448/IAS.19.4.20883 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JA, Smith NK, 2016. The Sexual Acceptability of Contraception: Reviewing the Literature and Building a New Concept. J Sex Res. 10.1080/00224499.2015.1134425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh ML, Jerman J, 2018. Contraceptive method use in the United States: trends and characteristics between 2008, 2012 and 2014. Contraception 97, 14–21. https://doi.org/S0010-7824(17)30478-X [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matjasko JL, Niolon PH, Valle LA, 2013. The Role of Economic Factors and Economic Support in Preventing and Escaping from Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 10.1002/pam.21666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougal L, Silverman JG, Singh A, Raj A, 2020. Exploring the relationship between spousal violence during pregnancy and subsequent postpartum spacing contraception among first-time mothers in India. EClinicalMedicine 23. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melbostad HS, Badger GJ, Rey CN, MacAfee LK, Dougherty AK, Sigmon SC, Heil SH, 2020. Contraceptive Knowledge among Females and Males Receiving Medication Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder Compared to Those Seeking Primary Care. Subst Use Misuse 55. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1823418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WB, 1994. Childbearing motivations, desires, and intentions: a theoretical framework. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr 120, 223–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore EM, Han J, Serio-Chapman CE, Mobley C, Watson C, Terplan M, 2012. Contraception and clean needles: Feasibility of combining mobile reproductive health and needle exchange services prioritizing female exotic dancers. Journal of Adolescent Health 50, S23. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestadt DF, Park JN, Galai N, Beckham SW, Decker MR, Zemlak J, Sherman SG, 2021. Sex Workers as Mothers: Correlates of Engagement in Sex Work to Support Children. Global Social Welfare. 10.1007/s40609-021-00213-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt L, Grenfell P, Meiksin R, Elmes J, Sherman SG, Sanders T, Mwangi P, Crago AL, 2018. Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoS Med 15, e1002680. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002680 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SR, Baral S, 2015. Fertility-related research needs among women at the margins. Reprod Health Matters 23, 30–46. 10.1016/j.rhm.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Tomko C, White RH, Nestadt DF, Silberzahn BE, Clouse E, Haney K, Galai N, 2021. Structural and Environmental Influences Increase the Risk of Sexually Transmitted Infection in a Sample of Female Sex Workers. Sex Transm Dis 48. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000001400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberzahn BE, Tomko CA, Clouse E, Haney K, Allen ST, Galai N, Footer KHA, Sherman SG, 2021. The EMERALD (enabling mobilization, empowerment, risk reduction, and lasting dignity) study: Protocol for the design, implementation, and evaluation of a community-based combination HIV prevention intervention for female sex workers in Baltimore, Maryland. JMIR Res Protoc 10. 10.2196/23412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaller J, Cimino AN, 2017. The Girl Is Mine: Reframing Intimate Partner Violence and Sex Work as Intersectional Spaces of Gender-Based Violence. Violence Against Women 23, 202–221. 10.1177/1077801216638766 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulibarri MD, Salazar M, Syvertsen JL, Bazzi AR, Rangel MG, Orozco HS, Strathdee SA, 2019. Intimate Partner Violence Among Female Sex Workers and Their Noncommercial Male Partners in Mexico: A Mixed-Methods Study. Violence Against Women 25, 549–571. 10.1177/1077801218794302 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2017. WHO | About social determinants of health. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Zemlak JL, Bryant AP, Jeffers NK, 2020. Systematic Review of Contraceptive Use Among Sex Workers in North America. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 49, 537–548. 10.1016/j.jogn.2020.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemlak JL, White RH, Nestadt DF, Alexander KA, Park JN, Sherman SG, 2021a. Interpersonal Violence and Contraceptive Method Use by Women Sex Workers. Women’s Health Issues 31, 516–522. 10.1016/j.whi.2021.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]