ABSTRACT

Palmitoylation of viral proteins is crucial for host-virus interactions. In this study, we examined the palmitoylation of Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) nonstructural protein 2A (NS2A) and observed that NS2A was palmitoylated at the C221 residue of NS2A. Blocking NS2A palmitoylation by introducing a cysteine-to-serine mutation at C221 (NS2A/C221S) impaired JEV replication in vitro and attenuated the virulence of JEV in mice. NS2A/C221S mutation had no effect on NS2A oligomerization and membrane-associated activities, but reduced protein stability and accelerated its degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. These observations suggest that NS2A palmitoylation at C221 played a role in its protein stability, thereby contributing to JEV replication efficiency and virulence. Interestingly, the C221 residue undergoing palmitoylation was located at the C-terminal tail (amino acids 195 to 227) and is removed from the full-length NS2A following an internal cleavage processed by viral and/or host proteases during JEV infection.

IMPORTANCE An internal cleavage site is present at the C terminus of JEV NS2A. Following occurrence of the internal cleavage, the C-terminal tail (amino acids 195 to 227) is removed from the full-length NS2A. Therefore, it was interesting to discover whether the C-terminal tail contributed to JEV infection. During analysis of viral palmitoylated protein, we observed that NS2A was palmitoylated at the C221 residue located at the C-terminal tail. Blocking NS2A palmitoylation by introducing a cysteine-to-serine mutation at C221 (NS2A/C221S) impaired JEV replication in vitro and attenuated JEV virulence in mice, suggesting that NS2A palmitoylation at C221 contributed to JEV replication and virulence. Based on these findings, we could infer that the C-terminal tail might play a role in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence despite its removal from the full-length NS2A at a certain stage of JEV infection.

KEYWORDS: Japanese encephalitis virus, NS2A, palmitoylation, replication, virulence, protein stability

INTRODUCTION

The Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is a zoonotic arthropod-borne virus belonging to the genus Flavivirus of the family Flaviviridae, which includes more than 70 species of flaviviruses, such as Zika virus (ZIKV), dengue virus (DENV), and yellow fever virus (YFV) (1). It is an enveloped RNA virus with a single-stranded positive-sense RNA genome encoding a single polyprotein. Following translation, the polyprotein is cleaved proteolytically by a combination of viral nonstructural proteins NS2B-NS3 and host proteases into three structural proteins (C, prM/M, and E) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) (2, 3). The structural proteins are essential for receptor binding, entry, and membrane fusion at the early stage of viral infection and the formation and maturation of progeny virus at the late stage of viral infection. The nonstructural proteins are involved mainly in viral RNA synthesis, virion assembly, and evasion of host innate immune response (4, 5).

Flavivirus NS2A is a multifunctional transmembrane protein that is involved in viral RNA replication, virion assembly, evasion of the innate immune response, and disease pathogenesis (6–13). JEV NS2A shares similar biological characteristics and functions with its counterpart in other flaviviruses (12). Previous observations indicate that JEV NS2A is involved in viral growth and tissue tropism in vitro (14), virulence in animals (15), and evasion of host antiviral response (16), suggesting that NS2A plays a role in JEV infection. It is known that an internal proteolytic cleavage site is present at the C terminus of flavivirus NS2A (17). Following cleavage by a combination of viral NS2B-NS3 and host cell proteases, the C-terminal tail is removed from the full-length NS2A and a C-terminally truncated form of NS2A (NS2Aα) is produced, which along with the full-length form of NS2A are copresent in flavivirus-infected cells. The C-terminally truncated NS2Aα is the major form in cells compared with the full-length NS2A, which is nearly undetectable in YFV- and ZIKV-infected cells (8, 18). Abolishing the internal cleavage blocks the production of both NS2Aα and infectious YFV (18), suggesting that the internal cleavage is essential for flavivirus replication. In the case of JEV, the internal cleavage site is considered to be present between the residues K194 and G195 (KKK↓GAV) in NS2A (17), but it is unknown whether the cleavage occurs during JEV infection. In addition, it would be interesting to know whether the C-terminal tail (amino acids 195 to 227), which is removed from the full-length NS2A, plays a role in JEV infection.

Palmitoylation is a posttranslational lipid modification of protein, in which a palmitoyl chain is covalently attached to a cysteine residue of substrate protein via a thioester bond, and determines the biological characteristics and functions of different proteins in cells by affecting their hydrophobicity, stability, trafficking, subcellular localization, and association with membranes (19, 20). Previous observations suggest that palmitoylation occurs on viral proteins of different virus species from a variety of virus families and is crucial for host-virus interactions, viral replication, and pathogenesis (19). For example, palmitoylation regulates the subcellular localization of bovine foamy virus envelope glycoprotein (21) and hepatitis C virus nonstructural protein 2 (22), the intracellular trafficking of influenza B virus NB protein (23), the membrane association of hepatitis E virus ORF3 protein (24), and Sindbis virus TF proteins (25).

The topology model of flavivirus NS2A demonstrates that NS2A contains five integral transmembrane segments across the lipid bilayer of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane and a C-terminal tail located in the cytosol (6). NS2A forms oligomers and interacts with viral RNA and proteins during flavivirus infection (6, 8, 26). We previously observed that JEV NS2A is localized to the ER in JEV-infected cells (27). Given the regulatory role of palmitoylation on biological characteristics and functions of viral proteins, such as membrane-associated activities and subcellular localization (22, 24, 25), we examined the palmitoylation of JEV NS2A and explored its role in viral replication and pathogenesis. We observed that NS2A was palmitoylatable and the inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation attenuated JEV replication efficiency in BHK-21 cells and virulence in mice.

RESULTS

NS2A is palmitoylatable, and the C221 residue is identified as the palmitoylation site.

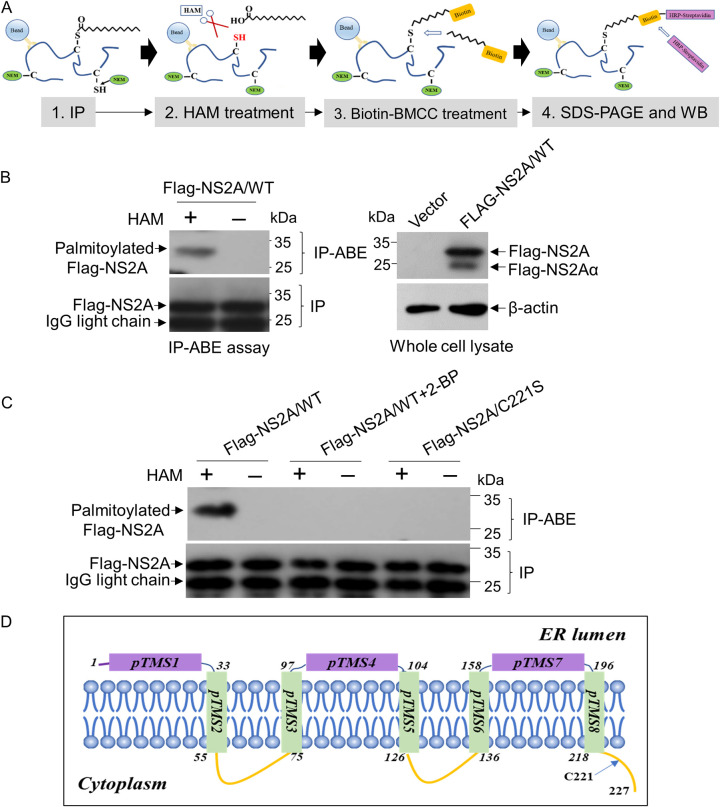

To determine whether NS2A was a palmitoylated protein, Flag-tagged wild-type NS2A (Flag-NS2A/WT) was expressed in HEK-293T cells and analyzed for palmitoylation by an immunoprecipitation and acyl-biotin exchange (IP-ABE) assay (Fig. 1A). In this procedure, cells expressing Flag-NS2A/WT were treated with N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to preblock free thiol groups and immunoprecipitated by anti-Flag antibodies. The palmitoylated thiol of cysteine in Flag-NS2A/WT was unmasked by treatment with hydroxylamine (HAM) and subsequently labeled with biotin-BMCC {1-biotinamido-4-[4′-(maleimidomethyl)cyclohexane-carboxamido]butane}. The labeled biotin was detected by Western blot analysis with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-streptavidin (28). A 27-kDa band corresponding to the palmitoylated Flag-NS2A/WT was detected in the HAM-treated sample (HAM+) compared with the mock-treated sample (HAM−) (Fig. 1B), suggesting that Flag-NS2A/WT was palmitoylated. To confirm this result, Flag-NS2A/WT was expressed in HEK-293T cells and subsequently treated with the protein palmitoylation inhibitor 2-bromopalmitate (2-BP) (29) to inhibit protein palmitoylation. No band corresponding to the palmitoylated Flag-NS2A/WT was present in cells treated with 2-BP (Fig. 1C, Flag-NS2A/WT + 2-BP) compared with the mock-treated sample (Fig. 1C, Flag-NS2A/WT), confirming that Flag-NS2A/WT was palmitoylated.

FIG 1.

Detection of NS2A palmitoylation. (A) Schematic representation of the IP-ABE assay for protein palmitoylation. (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with a plasmid expressing Flag-NS2A/WT and subsequently mock treated or treated with 1 M HAM. Protein palmitoylation was examined by IP-ABE assay. The palmitoylated Flag-NS2A/WT and the immunoprecipitated Flag-NS2A/WT were blotted with HRP-streptavidin and anti-Flag antibody, respectively. (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Flag-NS2A/WT and Flag-NS2A/C221S and subsequently mock treated (Flag-NS2A/WT and Flag-NS2A/C221S groups) or treated with 30 μM 2-BP (Flag-NS2A/WT + 2-BP group). Protein palmitoylation was examined by IP-ABE assay in the presence and absence of HAM. The palmitoylated Flag-NS2A and the immunoprecipitated Flag-NS2A were blotted by HRP-streptavidin and anti-Flag antibody, respectively. (D) Prediction of the residue C221 location in NS2A membrane topology using TMHMM2 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/). pTMS, position of transmembrane segment.

There are two cysteine residues at positions 180 (C180) and 221 (C221) of JEV NS2A. To predict the palmitoylation sites on NS2A, the motif-based predictor CSS-palm 4.0 (30) was used. A score of 0.712 that was lower than the cutoff value of 3.536 was predicted for the C180 residue, while a high score of 4.546 was obtained for the C221 residue, which was conserved in all the genotypes of JEV strains we examined. Therefore, C221 was considered a potential palmitoylation site (Table 1). It is known that the cysteine undergoing palmitoylation is either close to the transmembrane/cytoplasmic tail domain boundary region or located in the cytoplasmic tail domain of a protein (31). NS2A is a transmembrane protein. Topological analysis predicted that the C221 residue was located in the cytoplasmic tail of JEV NS2A (Fig. 1D).

TABLE 1.

Conservation of residue C221 among different JEV genotypes

| Genotype | Strain | GenBank no. | Peptide sequencea | Score | Cutoff |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GI | SD12 | MH753127.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 |

| SH7 | MH753129.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| YN0967 | JF706268.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| 131V | GU205163.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| HN0421 | JN381841.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| GX0519 | JN381835.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| HN0626 | JN381837.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| GSBY0801 | JF706274.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| K94P05 | AF045551.2 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| SH53 | JN381850.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| XJ69 | EU880214.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| SD0810 | JF706286.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| XZ0938 | HQ652538.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| M28 | KT957422.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| TS00 | MT253732.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| GII | Seisia810 | MT253736.1 | TIAAGLMACNPNKKR | 3.637 | 3.536 |

| FU | AF217620.1 | TIAAGLMACNPNKKR | 3.637 | 3.536 | |

| WTP-70-22 | HQ223286.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| Inj802 | MT253735.1 | TIAAGLMACNPNKKR | 3.637 | 3.536 | |

| JKT654 | HQ223287.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| GIII | ASSAM_03 | MZ702743.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 |

| SH15 | MH753130 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| SH19 | MH753131 | TIAAGLMFCNPNKKR | 4.466 | 3.536 | |

| N28 | MH753126.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| IND-WB-JE2 | JX072965.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| JEV/sw/GD/2008 | KX965684.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| Nakayama | EF571853.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| GP78 | AF075723.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| K87P39 | AY585242.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| C17 | KX945367.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| p3 | U47032.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| Beijing-1 | L48961.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| GIV | Bali 2019 | MT253731.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 |

| 19CxBa-83-Cv | LC579814.1 | TIAAGLMVCNPNKKR | 4.546 | 3.536 | |

| GV | Muar | HM596272 | IMAAGLMACNPNKKR | 4.336 | 3.536 |

| XZ0934 | JF915894 | IMAAGLMACNPNKKR | 4.336 | 3.536 |

C221 is highlighted in boldface.

To examine whether C221 was the palmitoylation site, the cysteine at position 221 was replaced by serine to generate a cysteine-to-serine mutant (C221S) of Flag-NS2A, Flag-NS2A/C221S, that was resistant to palmitoylation (28). Flag-NS2A/C221S was expressed in HEK-293T cells and subjected to an IP-ABE assay. The palmitoylated band was detectable in Flag-NS2A/WT treated with HAM (Fig. 1C, Flag-NS2A/WT), in agreement with the result shown in Fig. 1B; however, no palmitoylated band was detected in Flag-NS2A/C221S treated with HAM (Fig. 1C, Flag-NS2A/C221S). Overall, these data demonstrated that NS2A was palmitoylatable and the residue C221 was identified as the palmitoylation site.

The C-terminal tail harboring the C221 residue is removed from full-length NS2A in JEV-infected cells.

The internal cleavage processed by viral and/or host cell proteases occurs in flavivirus NS2A, which removes the C-terminal tail from full-length NS2A and produces the C-terminally truncated form NS2Aα (8, 17, 18). The internal cleavage site is considered to be between residues K194 and G195 (KKK↓GAV) in JEV NS2A (17) and the C-terminal tail (amino acids 195 to 227) containing the C221 residue for palmitoylation will be removed from the full-length NS2A following the internal cleavage (Fig. 2A). Because of a lack of antibodies specific to NS2A, we previously constructed a recombinant JEV harboring hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged NS2A (HA-NS2A) and silenced in HA-tagged NS1' (HA-NS1') production (JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1') to analyze the biological characteristics and functions of NS2A during JEV infection using anti-HA antibodies (27). The NS1' protein is generated by an RNA pseudoknot-mediated ribosomal frameshift event that occurs between the codons 8 and 9 of the NS2A gene, resulting in the synthesis of a derivative NS1 protein (NS1') harboring additional 52 amino acids at its C terminus. To eliminate HA-NS1' production that may consequently interfere with HA-NS2A functions, codon GCC for alanine at amino acid position 30 of NS2A was replaced with codon CCA for proline to generate an alanine 30-to-proline substitution mutant of HA-NS2A (JEV-HA/NS2A/ΔNS1'), in which the frameshift-stimulating pseudoknot structure was disrupted, abolishing HA-NS1' synthesis (27). Taking advantage of the recombinant JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1', we examined whether the internal cleavage occurred in JEV-infected cells. The molecular weight of HA-NS2A expressed in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' was compared with that exogenously expressed in cells transfected with the plasmid expressing full-length HA-NS2A. Two bands corresponding to the full-length HA-NS2A (23 kDa) and the C-terminally truncated HA-NS2Aα (19.5 kDa) were observed in cells transfected with plasmid exogenously expressing full-length HA-NS2A (Fig. 2B, short exposure time). However, no band corresponding to the full-length HA-NS2A was detectable, whereas a band corresponding to the C-terminally truncated HA-NS2Aα (17 kDa) was present in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' (Fig. 2B, short exposure time). The slight difference in molecular weights between the viral HA-NS2Aα and the exogenously expressed HA-NS2Aα was attributable to an additional 9-amino-acid insertion between HA and NS2A in the multiple-cloning site of the pCMV-HA vector used. When the exposure time was extended, a faint band corresponding to the full-length HA-NS2A was observed in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' (Fig. 2B, long exposure time), suggesting that the internal cleavage of NS2A occurred in JEV-infected cells and that the majority of NS2A present in JEV-infected cells was the C-terminally truncated NS2Aα.

FIG 2.

Internal cleavage of NS2A in JEV-infected cells. (A) Schematic representation of amino acid sequences of full-length NS2A and C-terminally truncated NS2Aα. A red arrow indicates the internal cleavage site. The residue C221 for palmitoylation is highlighted in blue. (B) Detection of full-length NS2A and C-terminally truncated NS2Aα. BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.01 or transfected with plasmids expressing full-length HA-NS2A. Expression of NS2A was examined by Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies. The band sizes of HA-NS2A and HA-NS2Aα in cells transfected with a plasmid expressing full-length HA-NS2A were slightly larger than those in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' because of an additional 9-amino-acid insertion present between HA and NS2A at the multiple-cloning site of pCMV-HA vector. (C and D) BHK-21 cells were transfected with RNA transcripts of the indicated recombinant viruses and incubated for 72 h. Expression of the indicated viral proteins was detected by immunofluorescence assays (C) with antibodies against HA (green) and NS3 (red) and by Western blotting (D) with antibodies against HA and NS5. (E) BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.01 and incubated for 48 h. Protein palmitoylation was examined by IP-ABE assay in the presence and absence of HAM (1 M) treatment. The palmitoylated HA-NS2A and the immunoprecipitated HA-NS2A were blotted by HRP-streptavidin and anti-HA antibody, respectively.

The C-terminal tail (amino acids 195 to 227) containing the C221 residue for palmitoylation was removed from the full-length NS2A following internal cleavage, and the full-length NS2A was nearly undetectable in JEV-infected cells (Fig. 2A). This would result in the difficulty of detecting NS2A palmitoylation in JEV-infected cells. To bypass this difficulty, we attempted to construct a recombinant JEV harboring HA-NS2A with lysine-to-serine substitution (K194S) at residue 194 (JEV-HA/NS2A/K194S-ΔNS1') to abolish the cleavage site and determine NS2A palmitoylation in JEV-infected cells. However, blocking the internal cleavage of NS2A failed to rescue the recombinant JEV-HA/NS2A/K194S-ΔNS1' (Fig. 2C and D), in agreement with a previous observation in which abolishing the internal cleavage of NS2A blocks the production of infectious YFV (18).

Although the full-length NS2A was nearly undetectable compared with NS2Aα in JEV-infected cells, we attempted to examine NS2A palmitoylation in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1'. As expected, no full-length NS2A was immunoprecipitated and no palmitoylated HA-NS2A was detectable (Fig. 2E), probably due to the extremely smaller amount of full-length NS2A present in JEV-infected cells. Overall, these data suggested that NS2A was cleaved and the C-terminal tail containing the C221 residue for palmitoylation was removed from the full-length NS2A in JEV-infected cells, which thereby resulted in the difficulty of detecting NS2A palmitoylation in JEV-infected cells.

In addition, a band corresponding to HA-NS2Aα was observed with the full-length HA-NS2A in cells transfected with plasmid expressing full-length HA-NS2A (Fig. 2B), suggesting that host cell proteases processed the internal cleavage of NS2A, in agreement with a previous observation that host cell protease can cleave the sites that are processed by viral NS2B-NS3 protease (3).

Inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation by C221S mutation impairs JEV replication in vitro.

Although the C-terminal tail containing the C221 residue for palmitoylation was removed from the full-length NS2A in JEV-infected cells, we evaluated the role of NS2A palmitoylation on JEV replication. A recombinant JEV (JEV-NS2A/C221S) harboring a cysteine-to-serine mutation at residue C221 (C221S) of NS2A (NS2A/C221S) was generated, and the NS2A/C221S mutation in the rescued JEV-NS2A/C221S was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Fig. 3A). BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S and its parental virus (JEV-NS2A/WT), and the replication kinetics were monitored using a 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) assay. The viral titers of JEV-NS2A/WT were higher than those of JEV-NS2A/C221S, and significant differences were observed from 48 to 72 h postinfection (hpi) (Fig. 3B). A similar difference in levels of viral E gene expression between JEV-NS2A/WT and JEV-NS2A/C221S was also observed (Fig. 3C). These data suggested that inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation by C221S mutation impaired JEV replication in vitro. To confirm this result, the difference in levels of viral replication between JEV-NS2A/WT and JEV-NS2A/C221S was further determined by immunofluorescence assay, Western blot analysis, and plaque assay. The number of JEV-positive cells immunostained with antibodies specific to JEV NS3 protein in cells infected with JEV-NS2A/WT was higher than that in cells infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S (Fig. 3D). Analysis of JEV NS5 protein abundance showed that NS5 was detectable at 12 hpi and expressed at a higher level at 24 hpi in cells infected with JEV-NS2A/WT than in cells infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S (Fig. 3E). To further examine the expression of viral proteins of JEV-NS2A/C221S, we generated a recombinant JEV harboring the HA-tagged NS2A/C221S mutation (JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1') based on the backbone of JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' (27) and analyzed the difference in levels of NS2A and NS5 expression between JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1'. Reduced expression of both HA-NS2Aα and NS5 was observed in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' compared with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' (Fig. 3F). Analysis of plaque sizes formed in BHK-21 cells indicated that JEV-NS2A/WT formed plaques ~3-fold larger than those formed by JEV-NS2A/C221S (Fig. 3G and H). Overall, these results suggested that JEV-NS2A/C221S replicates less efficiently in BHK-21 cells than JEV-NS2A/WT, indicating that NS2A palmitoylation contributed to the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency in vitro.

FIG 3.

Effect of NS2A/C221S mutation on JEV replication. (A) Sequencing chromatogram of NS2A/C221S mutation from the rescued JEV-NS2A/C221S. The vial RNAs of JEV-NS2A/C221S rescued were amplified by RT-PCR and subjected to DNA sequencing to confirm the C221S mutation of NS2A. (B and C) BHK-21 cells were infected with the indicated JEV at an MOI of 0.01 and harvested at different time points for analysis of viral replication by TCID50 (B) and qRT-PCR (C) assays. (D) BHK-21 cells were infected with the indicated JEV strain, and the expression of NS3 protein was examined by immunofluorescence assay with anti-NS3 antibody (red). The nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (blue). (E) BHK-21 cells were infected with the indicated JEV strain at an MOI of 0.01 and harvested at different time points for analysis of NS5 expression by Western blot analysis with anti-NS5 antibody. Intensities of protein bands were determined by densitometric analysis. Relative levels of NS5 were normalized to β-actin levels and are presented relative to the levels in JEV-NS2A/WT at 12 hpi (set as 1). (F) BHK-21 cells were infected with the indicated JEV strain at an MOI of 0.01 and harvested at different time points for analysis of expression of NS5 and HA-NS2Aα by Western blotting. Intensities of protein bands were determined by densitometric analysis. Relative levels of NS5 or HA-NS2Aα were normalized to β-actin levels and are presented relative to the levels in JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' at 12 h postinfection (set as 1). (G and H) BHK-21 cells were infected with the indicated JEV strain at 100 PFU, and the plaques were stained at 5 days postinfection (G). The plaque diameters were measured and plotted (H). All data are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. Significant differences between groups were tested by an unpaired Student's t test. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01.

Inhibiting NS2A palmitoylation by C221S mutation attenuates JEV virulence in mice.

To investigate the role of NS2A palmitoylation on JEV virulence, C57BL/6 mice were infected intraperitoneally with JEV-NS2A/WT and JEV-NS2A/C221S at doses ranging from 101 to 104 PFU, respectively, and monitored for 14 days. The mortality of the mice was observed in a dose-dependent manner from 8 days postinfection (dpi) in both groups (Fig. 4A). The histopathological lesions of JEV encephalitis, such as the lymphohistiocytic perivascular cuff and glial cell nodule, were detected in the brain samples from dead mice from both infected groups (Fig. 4B). The viral RNAs were amplified from the brains of dead mice and sequenced to confirm the presence of NS2A/C221S mutation. No reversion of the NS2A/C221S mutation was observed in the brain samples of mice infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S. Analysis of the survivors showed that infection by JEV-NS2A/WT caused mouse death, with mortalities of 30% to 90% that were significantly higher (P = 0.0163) than those of 10% to 80% in mice infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S (Fig. 4C). The 50% lethal dose (LD50) values for JEV-NS2A/WT and JEV-NS2A/C221S were 102 and 102.8 PFU, respectively. In addition, analysis of the survival times revealed that the survival times of mice infected with JEV-NS2A/WT were significantly shorter (P = 0.0038) than those of mice infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S (Fig. 4D). JEV develops a phase of transient viremia in certain vertebrate hosts after infection, which usually appears from 2 to 5 dpi with a peak at 3 dpi in JEV-infected mice (32). Blood samples were collected from the infected mice at 2, 3, and 5 dpi for analysis of RNAemia. RNAemia was detectable in all mice infected. However, significantly higher levels of RNAemia were observed in mice infected with JEV-NS2A/WT at doses of 103 and 104 PFU at 2 and 3 dpi compared with mice infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S (Fig. 4E). The levels of viremia in mice infected with JEV-NS2A/WT at 5 dpi were relatively higher than those in mice infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S, but no significant difference between the two viruses was observed. This was probably attributable to the difficulty in comparing JEV levels at the ending phase of viremia when the levels of viremia were low and about to disappear. Overall, these results suggested that JEV-NS2A/C221S was attenuated in mice compared with JEV-NS2A/WT, indicating that NS2A palmitoylation at residue C221 contributed to the maintenance of JEV virulence in mice.

FIG 4.

Effect of NS2A/C221S mutation on JEV virulence. (A to D) Mice (n = 10) were intraperitoneally mock infected or infected with the indicated JEV strain at doses ranging from 101 to 104 PFU and monitored daily for 14 days. Survival rates were calculated and plotted (A). Histopathological lesions of brains from the dead mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (B). The lymphohistiocytic perivascular cuff and glial cell nodule are indicated by black and blue arrows, respectively. Bar, 40 μm. The significant differences in mortality (C) and survival time (D) between groups were analyzed by two-way ANOVA. (E) Mice (n = 5) were intraperitoneally mock infected or infected with the indicated JEV strain at doses of 103 and 104 PFU, and blood samples were collected at 2, 3, and 5 dpi. The levels of RNAemia were examined by qRT-PCR. All data are presented as the mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. Significant difference in RNAemia levels between groups was analyzed by an unpaired Student's t test. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

NS2A/C221S mutation shows no significant effect on NS2A oligomerization.

Inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation by the C221S mutation reduced JEV replication efficiency in BHK-21 cells and attenuated JEV virulence in mice, suggesting the role of NS2A palmitoylation at residue C221 in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence. It is known that flavivirus NS2A forms dimers and higher orders of oligomers (6, 8, 33). The residue C221 might be involved in NS2A oligomerization via forming a disulfide bond and the attenuated phenotypes of JEV-NS2A/C221S in virus replication and virulence might be resulted from the impaired NS2A oligomerization by NS2A/C221S mutation. To exclude this possibility, BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and NS2A oligomerization was examined by Western blot analysis with anti-HA antibody under nonreducing (in the absence of β-mercaptoethanol [2-ME]) (2-ME−) or reducing (in the presence of 2-ME) (2-ME+) conditions. A single band of 35 kDa corresponding to the dimer of HA-NS2Aα and multiple bands of >50 kDa, probably representing the higher orders of HA-NS2Aα oligomers, were observed in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' under the nonreducing condition (2-ME−) compared with the samples examined under the reducing condition (2-ME+) (Fig. 5A), suggesting that JEV NS2A formed dimers and higher orders of oligomers. The 35-kDa band corresponding to the dimer of HA-NS2Aα and the multiple bands of >50 kDa, probably representing the higher orders of HA-NS2Aα, were also observed in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' under nonreducing conditions (2-ME−), showing a pattern of NS2A oligomerization similar to that in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1'. This result suggested that the NS2A/C221S mutation showed no obvious effect on NS2A oligomerization. Furthermore, we validated this result using the exogenously expressed HA-NS2A/WT and HA-tagged NS2A/C221S mutation (HA-NS2A/C221S) in HEK-293T cells. The dimer of HA-NS2A was observed in both cells transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2A/C221S under nonreducing conditions (2-ME−) (Fig. 5B), confirming that the NS2A/C221S mutation showed no obvious effect on NS2A oligomerization. These data suggest that residue C221 was not involved in NS2A oligomerization, excluding the possibility that the NS2A/C221S mutation reduced virus replication and virulence via impairing NS2A oligomerization.

FIG 5.

Effect of NS2A/C221S mutation on NS2A oligomerization. (A) BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.01 and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.05 and harvested for Western blot analysis. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing (in the absence of 2-ME) or reducing (in the presence of 2-ME) conditions and examined by Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibodies. The internal control β-actin was examined under the reducing condition. (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT or HA-NS2A/C221S and harvested at 24 h posttransfection. The samples were separated by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing or reducing conditions and examined by Western blot analysis using anti-HA antibodies. The internal control β-actin was examined under the reducing condition.

NS2A/C221S mutation shows no significant effect on membrane-associated activities of NS2A.

Flavivirus NS2A is an ER-resident transmembrane protein (8, 34). Recent observations show that JEV NS2A can localize to the ER (27). It is known that palmitoylation mediates the membrane association of viral proteins (24, 25). Therefore, we analyzed the effect of NS2A palmitoylation on its membrane-associated activities to explore mechanisms underlying the role of NS2A palmitoylation in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence. To this end, HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2A/C221S were exogenously expressed in HEK-293T cells and subsequently subjected to a membrane flotation assay using a density gradient of 10% to 20% to 30% iodixanol. Twenty-four fractions were collected from the top (low density) to bottom (high density) of the iodixanol density gradient tube and assayed by Western blotting to detect the presence of HA-NS2A. Calnexin, a well-known ER integral membrane protein (22, 35), and β-actin were used as references for the membrane-associated proteins and soluble proteins, respectively. HA-NS2A/WT was found to be distributed in the high-density fractions where β-actin was present. However, a portion of HA-NS2A/WT floated to the low-density fractions where calnexin existed (Fig. 6A), suggesting that JEV NS2A was able to associate with membranes, in agreement with findings that flavivirus NS2A is a membrane-associated protein (34). Analysis of the distribution of HA-NS2A/C221S in both high-density and low-density fractions showed a pattern similar to that of HA-NS2A/WT (Fig. 6A). No remarkable differences in the distribution of HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2A/C221S in either the high-density or low-density fractions were observed, suggesting that the inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation by C221S mutation had no significant effect on its membrane-associated activities.

FIG 6.

Effect of NS2A/C221S mutation on NS2A membrane association. (A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2A/C221S and harvested at 24 h posttransfection for the membrane flotation assay. The presence of HA-NS2A in fractions was examined by Western blot analysis with anti-HA antibodies. The fractions containing membrane-associated proteins and soluble proteins were identified by antibodies specific to calnexin and β-actin, respectively. Intensities of protein bands were determined by densitometric analysis. Asterisks note the percentage of the indicated protein present in the fraction of membrane-associated proteins, which was calculated by dividing the level of protein detectable from the fraction of membrane-associated proteins by that from all fractions. (B) BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.01 and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.05 and harvested at 48 hpi for isolation of the DRM. The top nine fractions were collected from the centrifugation tube, and the presence of HA-NS2A was detected by Western blot analysis with anti-HA antibodies. The DRM within the ER was identified by antibodies specific to Erlin-2. Intensities of protein bands were determined by densitometric analysis. The symbol # indicates the percentage of the indicated protein present in the DRM fraction, which was calculated by dividing the level of protein detectable from the DRM fraction by that from all fractions. (C) BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.01 and harvested at 24 hpi for analysis of NS2A subcellular localization to the ER. The subcellular localization of HA-NS2A (green) and the ER (red) was detected by immunofluorescence assay with antibodies specific to HA and Erlin-2, respectively. (D and E) BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-NS2A/WT and JEV-NS2A/C221S at an MOI of 0.01 and harvested at 24 hpi for morphological analysis of membrane vesicles (Ves) by transmission electron microscopy. The Ves formed by JEV are indicated with red arrowheads (D). The numbers of Ves counted from five visual fields randomly selected were statistically compared between groups and plotted (E). All data are presented as mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Student's t test.

Although the C-terminal tail containing the C221 residue for palmitoylation was removed from the full-length NS2A in JEV-infected cells, NS2A palmitoylation at C221 might play a role in the regulation of its membrane-associated activity before the occurrence of internal cleavage. Therefore, we analyzed the effect of NS2A palmitoylation on its localization to the ER in JEV-infected cells. To this end, BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' and treated with Triton X-100. The cell lysates were subjected to isolation of the detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs) within the ER (22). Nine fractions were collected from the top gradient (low density) of the sucrose density gradient tube and assayed by Western blotting to detect the presence of HA-NS2A (Fig. 6B). The detergent-resistant fractions corresponding to the DRMs were identified by antibodies specific to the ER lipid raft-associated protein 2 (Erlin-2), a marker of the DRM within the ER (22). Because the full-length NS2A was nearly undetectable in JEV-infected cells (Fig. 2B), we alternatively examined the presence of HA-NS2Aα. Both HA-NS2Aα expressed in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' were detected in the top fractions containing the DRM where Erlin-2 was present, with a similar distribution pattern (Fig. 6B), suggesting that inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation by the C221S mutation had no significant effect on its localization to the ER. Furthermore, the effect of NS2A palmitoylation on its subcellular localization to the ER was examined by immunofluorescence assay. No significant difference in the colocalization of HA-NS2A with Erlin-2 between JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' was observed (Fig. 6C).

Flavivirus NS2A associates with the ER and remodels the ER membrane to generate the membrane vesicles (Ves) for viral replication (11, 36, 37). Although the NS2A/C221S mutation showed no significant effect on NS2A membrane association, we analyzed the effect of NS2A palmitoylation on Ve formation. To this end, BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-NS2A/WT and JEV-NS2A/C221S and subsequently subjected to transmission electron microscopy analysis. Ultrathin transmission electron microscopy images indicated that the Ve morphology formed by JEV-NS2A/C221S was similar to that formed by JEV-NS2A/WT; no obvious difference was observed between them (Fig. 6D). The number of Ves formed by JEV-NS2A/C221S was also similar to that formed by JEV-NS2A/WT (Fig. 6E). Overall, these observations indicated that the inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation by C221S mutation showed no significant effect on its membrane-associated activities, therefore excluding the possibility that NS2A/C221S mutation reduced JEV replication and virulence via impairing its membrane-associated activities.

NS2A palmitoylation at residue C221 is essential for protein stability.

Palmitoylation plays a role in the regulation of protein stability (38, 39). Therefore, we examined the effect of NS2A palmitoylation on the stability of the protein and explored mechanisms underlying the role of NS2A palmitoylation in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence. To this end, HA-NS2A/WT was exogenously expressed in HEK-293T cells, and the cells were treated with different doses of 2-BP to inhibit palmitoylation. The changes in HA-NS2A/WT abundance were examined by Western blotting. In response to 2-BP, the abundance of the HA-NS2A/WT protein gradually decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 7A), suggesting that the inhibition of palmitoylation might result in the degradation of the HA-NS2A/WT protein. As a control, the effect of 2-BP treatment on Flag-NS5 expressed in HEK-293T cells was analyzed parallelly and no significant change in the Flag-NS5 abundance was observed in response to 2-BP treatment (Fig. 7A).

FIG 7.

Effect of NS2A/C221S mutation on NS2A protein stability. (A) HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT or Flag-NS5 and treated with the indicated concentrations of 2-BP to inhibit palmitoylation. Changes in protein levels of HA-NS2A and Flag-NS5 were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against HA and Flag. Intensities of protein bands were determined by densitometric analysis. Relative levels of HA-NS2A/WT and Flag-NS5 were normalized to β-actin levels and are presented relative to the levels in mock-treated cells (set as 1). (B) HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT or HA-NS2Aα and mock treated or treated with 2-BP (30 μM), NH4Cl (10 μM), CQ (100 μM), or MG132 (10 μM). Changes in HA-NS2A protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. Intensities of protein bands were determined by densitometric analysis. Relative levels of HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2Aα were normalized to β-actin levels and are presented relative to the levels in mock-treated cells (set as 1). (C) HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT and treated with 30 μM 2-BP or a combination of 2-BP (30 μM) and NH4Cl (10 μM), 2-BP (30 μM) and CQ (100 μM), or 2-BP (30 μM) and MG132 (10 μM). Changes in HA-NS2A protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies. Intensities of protein bands were determined by densitometric analysis. Relative levels of HA-NS2A/WT were normalized to β-actin levels and are presented relative to the levels in mock-treated cells (set as 1). (D) BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.01 and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.05 and subjected to CHX chase assay. (E) HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT and treated with 30 μM 2-BP. The effect of 2-BP on NS2A protein stability was analyzed by CHX chase assay. (F) HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2A/C221S and mock treated or treated with 10 μM MG132. The effect of NS2A/C221S mutation on NS2A protein stability was analyzed by a CHX chase assay. The curves of HA-NS2A degradation were generated using GraphPad Prism 7.01. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA.

It is known that proteins are degraded through several pathways, such as the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and the autophagy-lysosome pathway (40, 41). Therefore, we inhibited the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and the autophagy-lysosome pathway to examine the effects on JEV NS2A protein stability. The cells expressing HA-NS2A/WT or HA-NS2Aα were treated with MG132, an inhibitor of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (42), or treated with NH4Cl and chloroquine (CQ), inhibitors of the autophagy-lysosome pathway (43, 44), and the abundances of HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2Aα in the treated cells were examined by Western blotting. The treatment with NH4Cl and CQ slightly altered the abundances of HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2Aα, whereas MG132 treatment resulted in an obvious increase in the abundances of both HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2Aα compared with the mock-treated control (Fig. 7B), suggesting that NS2A was degraded mainly via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. These observations agreed with a previous suggestion that JEV NS2A is degraded via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (43). Interestingly, 2-BP treatment reduced the abundance of HA-NS2A/WT, but not HA-NS2Aα (Fig. 7B), suggesting that palmitoylation might contribute to NS2A/WT stability. To explore the degradation pathways of NS2A in response to 2-BP, cells expressing HA-NS2A/WT were treated with 2-BP to inhibit palmitoylation and subsequently treated with MG132 or treated with NH4Cl and CQ. The abundance of HA-NS2A/WT in the treated cells was examined by Western blotting. The inhibition of the autophagy-lysosome pathway by NH4Cl or CQ slightly rescued the degradation of HA-NS2A/WT induced by 2-BP (Fig. 7C, NH4Cl and CQ panels). However, inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by MG132 completely rescued the degradation of HA-NS2A/WT induced by 2-BP. The level of accumulated HA-NS2A/WT in MG132-treated cells was higher than that in MG132-untreated cells (Fig. 7C, MG132 panel). These data suggested that inhibition of palmitoylation by 2-BP might destabilize HA-NS2A/WT and result in its degradation mainly via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

To evaluate the effect of NS2A palmitoylation at C221 on protein stability, BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' and subjected to a cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay. Because the full-length HA-NS2A was nearly undetectable in JEV-infected cells (Fig. 2B), the degradation kinetics of HA-NS2Aα, instead of the full-length HA-NS2A, were analyzed by Western blotting. No significant difference in the degradation kinetics of HA-NS2Aα between JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' was observed (Fig. 7D). This similarity in degradation kinetics of HA-NS2Aα between JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' was probably because NS2Aα was not palmitoylated as the C-terminal tail containing the residue C221 for palmitoylation was removed following the internal cleavage.

Taking advantage of the fact that full-length NS2A was the major form of exogenously expressed NS2A (Fig. 2B), the effect of NS2A palmitoylation on its protein stability was analyzed by CHX chase assay using exogenously expressed HA-NS2A/WT. To this end, HA-NS2A/WT was exogenously expressed in cells and the cells were subsequently treated with 2-BP. Following CHX treatment, degradation kinetics were analyzed by Western blotting. The half-life of HA-NS2A/WT in 2-BP-treated cells was ~2.2 h, which was remarkably shorter than the 7.6 h half-life of HA-NS2A/WT in ethanol-treated control cells (Fig. 7E). These data suggested that the inhibition of palmitoylation by 2-BP-reduced NS2A protein stability. To confirm this result, HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2A/C221S were exogenously expressed in cells and subsequently subjected to a CHX chase assay. The half-life of HA-NS2A/C221S was ~1.7 h and was shorter than the 4.2-h half-life of HA-NS2A/WT (Fig. 7F). In addition, MG132 prolonged the half-life of HA-NS2A/C221S. Overall, these data indicated that inhibiting NS2A palmitoylation by 2-BP or C221S mutation reduced its protein stability and accelerated its degradation, suggesting that palmitoylation was essential for NS2A protein stability, thereby contributing to the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence.

DISCUSSION

Flavivirus NS2A is involved in viral RNA synthesis, virion assembly, and evasion of the innate immune response as well as disease pathogenesis (33). It is cleaved at the internal proteolytic cleavage site by a combination of viral and host cell proteases, resulting in the occurrence of two forms of NS2A in virus-infected cells: the major form of the C-terminally truncated NS2Aα and the minor form of the full-length NS2A (8, 17, 18). In this study, we also observed the two forms of NS2A present in JEV-infected cells: the C-terminally truncated NS2Aα and the full-length NS2A. The C-terminally truncated NS2Aα accounted for the majority of NS2A, whereas the full-length NS2A was nearly undetectable in JEV-infected cells. A previous observation suggests that abolishing the internal cleavage of NS2A blocks the production of infectious YFV (18). In this study, we also observed that abolishing the internal cleavage of NS2A failed to rescue the recombinant JEV, suggesting that the internal cleavage was essential for JEV replication. However, it was interesting to discover whether the C-terminal tail (amino acids 195 to 227) removed from the full-length NS2A played a role in JEV infection.

The palmitoylation of viral proteins is crucial for host-virus interactions during viral infection and contributes to viral replication and pathogenesis (19). Given the role of NS2A in JEV infection, we examined NS2A palmitoylation. There are two cysteine residues (C180 and C221) present at NS2A. The C180 residue was located at the side of the endoplasmic reticulum lumen of NS2A, while the C221 residue was present in the cytoplasmic tail of NS2A. Prediction of NS2A palmitoylation sites by the motif-based predictor CSS-palm 4.0 revealed that the C221 residue, but not the C180 residue, was a potential palmitoylation site. In addition, the cysteine undergoing palmitoylation is either close to the transmembrane/cytoplasmic tail domain boundary region or located in the cytoplasmic tail domain of a protein (31). Therefore, we selected the C221 residue, but not the C180 residue, for analysis of NS2A palmitoylation. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the C180 residue may be a palmitoylation site during JEV infection. The IP-ABE assay demonstrated that NS2A was palmitoylatable, and the C221 residue located at the C-terminal end of NS2A was identified as the palmitoylation site. However, the C221 residue undergoing palmitoylation was removed along with the C-terminal end of the full-length NS2A following the internal cleavage at an unknown stage of JEV infection. Therefore, it would be interesting to know whether NS2A palmitoylation at the residue C221 played a role in JEV infection; the outcome would also be useful for understanding the role of the C-terminal tail in JEV infection. Using the recombinant JEV-NS2A/C221S harboring NS2A/C221S mutations, we observed that the inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation by the mutation of C221S reduced JEV replication efficiency in BHK-21 cells and attenuated JEV virulence in mice. The viral titers of JEV-NS2A/C221S were significantly lower than those of JEV-NS2A/WT in BHK-21 cells. The survival rate of mice infected with JEV-NS2A/C221S was significantly higher than that of mice infected with JEV-NS2A/WT. These data demonstrated that NS2A palmitoylation at C221 contributed to the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence. However, the effect of NS2A palmitoylation at C221 on JEV virulence was relatively weak compared to the effect of JEV E protein, which plays a major role in determination of JEV virulence (45, 46). Based on these findings, we could also extrapolate that the C-terminal tail of NS2A might play, at least in part, a similar role in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence. This potential role of the C-terminal tail in JEV replication was in agreement with previous findings observed from other flavivirus infections, in which mutation of the residues R207, R222, and K193 present in the C-terminal tail of ZIKV (26) and residue G200 located at the C-terminal tail of DENV (33) reduce viral production. However, it was unknown whether the role of the C-terminal tail of NS2A in JEV replication and virulence was performed prior to or after occurrence of the internal cleavage. In addition, the fate of the C-terminal tail of NS2A after the internal cleavage and the effect of NS2A palmitoylation at C221 on the internal cleavage remained unknown.

Although we observed the role of NS2A palmitoylation in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence, the mechanisms underlying this role were unknown. It is known that flavivirus NS2A forms dimers and higher orders of oligomers (6, 8, 33); therefore, we examined whether NS2A/C221S mutation impaired the NS2A oligomerization that is essential for JEV infection. NS2A was observed to form dimers and higher orders of oligomers in JEV-infected cells, but NS2A/C221S mutation showed no effect on NS2A oligomerization, excluding the possibility that the NS2A/C221S mutation reduced JEV replication and virulence via impairing NS2A oligomerization.

Flavivirus NS2A, including JEV NS2A is an ER-resident transmembrane protein (8, 27, 34). Given that palmitoylation mediates the membrane association of viral proteins (24, 25), we analyzed the effect of NS2A palmitoylation on its membrane-associated activities to explore the mechanisms underlying the role of NS2A palmitoylation in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence. Inhibition of NS2A palmitoylation by the C221S mutation showed no significant effect on its association with the membrane or the DRM within the ER, suggesting that NS2A palmitoylation at C221 did not contribute to its membrane-associated activities. These data excluded the possibility that the NS2A/C221S mutation reduced JEV replication and virulence by impairing NS2A membrane-associated activities.

Palmitoylation plays a role in the regulation of protein stability (38, 39). Therefore, we examined the effect of NS2A palmitoylation on protein stability to explore the mechanisms underlying the role of NS2A palmitoylation in the maintenance of JEV efficient replication and virulence. Inhibition of palmitoylation by 2-BP destabilized the exogenously expressed HA-NS2A and led to degradation mainly via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The half-life of the exogenously expressed HA-NS2A with C221S mutation was remarkably reduced compared with that of HA-NS2A/WT. These data demonstrated that palmitoylation at residue C221 was essential for the maintenance of NS2A stability. However, it should be noted that no significant difference in the half-life of NS2Aα was observed between cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and those infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1'. This was probably because NS2Aα was not palmitoylated after the C-terminal tail containing the residue C221 for palmitoylation was removed following internal cleavage. Based on these observations, we speculated that palmitoylation at C221 played a role in the maintenance of NS2A stability before internal cleavage, thereby benefiting its functions, such as viral RNA synthesis, virion assembly, and evasion of the innate immune response, as well as finally contributing to the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence (Fig. 8A).

FIG 8.

Proposed model for the role of NS2A palmitoylation in JEV replication and virulence. JEV polyprotein after translation is proteolytically cleaved into three structural proteins and seven nonstructural proteins, including the full-length NS2A. (A) NS2A palmitoylation at C221 occurs before the internal cleavage and plays a role in the maintenance of NS2A stability, thereby benefiting its functions, such as viral RNA synthesis and virion assembly, and finally contributing to the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence. In contrast, blocking NS2A palmitoylation by C221S mutation reduces NS2A protein stability and accelerates its degradation, finally attenuating JEV replication efficiency and virulence. (B) NS2A palmitoylation at C221 occurs after the internal cleavage, and the palmitoylated C terminus plays a role in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence via unknown mechanisms.

The JEV polyprotein after translation is cleaved by a combination of viral and host cell proteases at intergenic junctions of C/prM, prM/E, E/NS1, NS1/NS2A, NS2A/NS2B, NS2B/NS3, NS3/NS4A, NS4A/NS4B, and NS4B/NS5, as well as at internal sites within C, NS2A, NS3, and NS4A, according to the knowledge of polyprotein processing of other flaviviruses (2, 3). However, the details of polyprotein processing as well as the viral and host factors involved during JEV infection remain to be defined. In the case of NS2A processing, it is unknown at what stage of JEV infection the internal cleavage occurs and whether NS2A is palmitoylated at C221 prior to or after the occurrence of the internal cleavage. The possibility that the C-terminal tail of NS2A might be palmitoylated at C221 after the internal cleavage, subsequently playing a role in the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence via unknown mechanisms, cannot be excluded (Fig. 8B). The occurrence of internal cleavage results in the removal of the C-terminal tail harboring the C221 residue for palmitoylation from the full-length NS2A, and this generated difficulty in validating NS2A palmitoylation as well its role in NS2A protein stability in JEV-infected cells. We have attempted to block the internal cleavage by mutation K194S at residue 194 but failed to rescue the recombinant virus. Therefore, the development of alternative approaches is needed for the validation of NS2A palmitoylation in JEV-infected cells.

In conclusion, NS2A was palmitoylatable and residue C221 located at the C-terminal tail of NS2A was identified as the palmitoylation site. Inhibiting NS2A palmitoylation at residue C221 by C221S mutation impaired JEV replication in BHK-21 cells and attenuated JEV virulence in mice. The NS2A/C221S mutation showed no effect on NS2A oligomerization and membrane-associated activities, but reduced its protein stability remarkably and accelerated its degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. These observations suggest that NS2A palmitoylation at C221 played a role in protein stability, thereby contributing to the maintenance of JEV replication efficiency and virulence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, China (IACUC no. SHVRI-Mo-2020090806), and performed in compliance with the “Guidelines on the Humane Treatment of Laboratory Animals” (Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China, policy no. 2006 398).

Cells, viruses, and reagents.

HEK-293T and BHK-21 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C under a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The JEV SD12 strain (GenBank no. MH753127), previously isolated from pigs (47), was used in this study. All JEV strains were grown and titrated using a TCID50 assay in BHK-21 cells. The reagents used in this study included IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), protease inhibitor cocktail tablet (Sigma), hydroxylamine (HAM) (Sigma), OptiPrep density gradient medium (Sigma), 2-bromohexadecanoic acid (2-BP) (Sigma), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) (Sigma), cycloheximide (CHX) (Sigma), biotin-BMCC (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), HRP-conjugated streptavidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), Dynabeads conjugated with protein G (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), β-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) (Sigma), and MG132 (MedChemExpress, Shanghai, China). The commercial antibodies used in this study were anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (Sigma), anti-HA monoclonal antibody (Sigma), anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL, USA), rabbit anti-calnexin polyclonal antibody (Sigma), and anti-Erlin-2 antibody (Abcam, Shanghai, China). The mouse anti-JEV NS3 polyclonal and rabbit anti-JEV NS5 polyclonal antibodies were prepared and preserved in our laboratory.

Plasmids and transfection.

The cDNAs encoding JEV NS2A were amplified from the JEV SD12 strain and cloned into an N-terminal p3×FLAG-CMV vector (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and pCMV-HA vector (Clontech) to generate Flag-NS2A and HA-NS2A, respectively. To substitute for cysteine with serine at position 221 of NS2A (NS2A/C221S), a site-directed mutation was used to generate plasmids expressing Flag-NS2A/C221S or HA-NS2A/C221S on the plasmids Flag-NS2A or HA-NS2A, respectively. Transfection of cells with recombinant plasmids was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen).

Construction of recombinant JEV.

Construction of recombinant JEV was performed as described previously (27, 48). The recombinant JEV with the K194S mutation in HA-NS2A (JEV-HA/NS2A/K194S-ΔNS1') and the recombinant JEV with C221S mutation in HA-NS2A (JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1') were constructed based on the backbone of JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' (27). The recombinant JEV with C221S mutation in NS2A (JEV-NS2A/C221S) was generated based on the backbone of the JEV SD12 strain. All recombinant viruses were rescued from BHK-21 cells and confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China). The clones of recombinant viruses containing any unwanted mutation were discarded.

Immunoprecipitation and acyl-biotin exchange assay.

NS2A palmitoylation was determined by the immunoprecipitation and acyl-biotin exchange (IP-ABE) assay as described previously (28). Briefly, HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Flag-NS2A/WT and Flag-NS2A/C221S and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. The cells were washed with prechilled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and subsequently treated with a lysis buffer (1% IGEPAL CA-630, 50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors [pH 7.5]) containing 50 mM NEM on ice for 30 min to irreversibly block unmodified cysteine thiol groups. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and incubated with anti-Flag antibody-pretreated Dynabeads conjugated with protein G overnight at 4°C. The Dynabeads were collected by magnetic adsorption and washed with lysis buffer containing 10 mM NEM. The collected Dynabeads were resuspended with lysis buffer (pH 7.2) and divided into two equivalent parts. One-half was incubated with lysis buffer (pH 7.2) containing 1 M HAM, and the remainder was incubated with lysis buffer (pH 7.2) without HAM as a control. Following incubation for 1 h at room temperature, the Dynabeads were collected by magnetic adsorption, washed with the lysis buffer (pH 6.2), and subsequently incubated with lysis buffer (pH 6.2) containing 4 μM biotin-BMCC for 1 h at 4°C to label the exposed cysteines with biotin. The Dynabeads were collected by magnetic adsorption and washed with the lysis buffer (pH 6.2), followed by washes with the lysis buffer (pH 7.5). The washed Dynabeads were incubated in 2× sample buffer containing 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) for 10 min at 80°C, and the eluted samples were subjected to Western blot analysis. The palmitoylated proteins that were labeled with biotin were detected by HRP-conjugated streptavidin. The immunoprecipitated Flag-NS2A was blotted by using anti-Flag antibody. Detection of HA-NS2A palmitoylation in cells infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' was performed accordingly with anti-HA antibodies.

Western blotting, immunofluorescence, and quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR assays.

Western blot and immunofluorescence assays were performed as described previously (49). For the quantitative real-time reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) assay, total RNA was extracted from JEV-infected cells or blood samples using AG RNAex Pro reagent (AG, Hunan, China) and reverse-transcribed with an Evo M-MLV RT premix (AG) following the manufacturer’s instructions. qRT-PCR was performed to measure the levels of the JEV E gene as described previously (50).

Infection of mice with recombinant JEV.

Three-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (n = 10) were intraperitoneally mock infected or infected with recombinant JEV at doses ranging from 101 to 104 PFU and monitored daily for 14 days. Mice showing neurological signs were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, followed by cervical dislocation according to the “Guidelines on the Humane Treatment of Laboratory Animals” (policy no. 2006 398). For histopathological assay, the tissue sections of brains from the dead mice were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The LD50 values were determined by the method of Reed and Muench for recombinant viruses (51). To measure RNAemia in JEV-infected mice, 3-week-old female C57BL/6 mice (n = 5) were intraperitoneally mock infected or infected with recombinant JEV at doses of 103 and 104 PFU. Blood samples were collected from the infected mice at 2, 3, and 5 days postinfection, and RNAemia was determined by qRT-PCR assay.

Growth kinetics and viral plaque assays.

Growth kinetics and viral plaque assays were performed as described previously (48). Briefly, BHK-21 cells were precultured until 80% confluent and subsequently infected with JEV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. Following 2 h of incubation, the cells were washed three times with prewarmed PBS and cultured in DMEM containing 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C. The supernatants were sampled from JEV-infected cells at different time points and titrated using a TCID50 assay in BHK-21 cells. For the viral plaque assay, BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV at 100 PFU and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Plaque morphology formed by JEV was determined as described previously (48).

Detection of NS2A oligomerization.

BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.01 and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' at an MOI of 0.05 and harvested at 48 hpi for Western blot analysis. The harvested samples were lysed and separated by nonreducing SDS-PAGE (in the absence of 2-ME) or reducing SDS-PAGE (in the presence of 2-ME), followed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibodies. To detect oligomerization of exogenously expressed HA-NS2A, HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT or HA-NS2A/C221S and harvested at 24 h posttransfection. The harvested samples were lysed and separated by nonreducing or reducing SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting using anti-HA antibodies.

Membrane flotation assay.

A membrane flotation assay was performed as described previously (52). Briefly, HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2A/C221S and harvested at 24 h posttransfection. The harvested cells were pelleted, resuspended in PBS containing 250 mM sucrose and protease inhibitor, and subsequently homogenized with a Dounce homogenizer. The supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 10 min and mixed with OptiPrep density gradient medium to prepare the lysate-iodixanol mixture containing 30% iodixanol. The lysate-iodixanol mixture (4 mL) was loaded at the bottom of a centrifuge tube and then gently overlaid with 20% iodixanol (4 mL) and then 10% iodixanol (4 mL). The resulting discontinuous iodixanol gradient was centrifuged at 200,000 × g for 16 h at 4°C in a Beckman SW41 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A total of 24 fractions (500 μL each) were collected from top to bottom of the centrifuge tube and subjected to Western blot analysis. The fractions containing membrane-associated proteins were identified by antibodies specific to calnexin.

DRM isolation.

BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' and harvested at 48 hpi for the isolation of DRM. The DRM isolation was performed as described previously (27, 52). The top nine fractions were collected from the centrifugation tube and subjected to Western blot analysis. The DRM was identified by antibodies specific to Erlin-2.

Transmission electron microscopy.

BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV at an MOI of 5 and scraped off at 24 hpi. The infected cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,000 rpm for 1 min and fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at room temperature. Following two washes with PBS, the pellets were postfixed with 1% OsO4 for 30 min, dehydrated in a serial concentration of acetone ranging from 50% to 100%, and subsequently treated with LR white. Ultrathin sections (70 nm) of the cell pellets were cut on a Leica EM UC7 ultramicrotome (Leica Microsystems) and stained with 5% aqueous uranyl acetate for 30 min. Finally, the ultrathin sections were stained with 0.4% lead citrate in water for 3 min and examined under a Tecnai G2 Spirit transmission electron microscope at 60 kV.

CHX chase assay.

To analyze the effect of 2-BP on NS2A protein stability, HEK-293T cells precultured at 37°C for 12 h were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT and treated with 30 μM 2-BP at 10 h posttransfection. Following incubation at 37°C for 14 h, the culture medium was replaced with medium containing 200 μg/mL CHX and the transfectants were further incubated at 37°C for the indicated periods from 0 h to 10 h. For the analysis of the C221S mutation on NS2A protein stability, HEK-293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT and HA-NS2A/C221S and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. MG132 at a concentration of 10 μM was added to the medium at 10 h posttransfection, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 14 h. The culture medium was replaced with medium containing 200 μg/mL CHX, and the transfectants were further incubated at 37°C for the indicated periods from 0 h to10 h. For the analysis of the effects of the C221S mutation on NS2A protein stability in JEV-infected cells, BHK-21 cells were infected with JEV-HA/NS2A/WT-ΔNS1' and JEV-HA/NS2A/C221S-ΔNS1' and incubated at 37°C for 48 h. The culture medium was replaced with medium containing 200 μg/mL CHX, and the infected cells were further incubated at 37°C for the indicated periods from 0 h to10 h. Changes in HA-NS2A protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies. The HA-NS2A protein half-life was determined using GraphPad Prism 7.01 (two-phase decay model).

Drug administration.

Cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-NS2A/WT or Flag-NS2A/WT and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The transfectants were treated with 2-BP at the indicated concentrations at 37°C and harvested at 14 h posttreatment for palmitoylation analysis or Western blotting. To examine the degradation pathways of NS2A in response to 2-BP, the transfectants were treated with 30 μM 2-BP at 10 h posttransfection and subsequently treated with 10 μM MG132, 10 μM NH4Cl, or 100 μM CQ for 14 h. Changes in NS2A abundance in the drug-treated cells were examined by Western blotting.

Bioinformatic analysis.

To predict the palmitoylation sites on NS2A, the amino acid sequences of NS2A from different JEV strains (Table 1) were downloaded from GenBank and analyzed using the motif-based predictor CSS-palm 4.0 (csspalm.biocuckoo.org/) (30). For analysis of the location of C221 in NS2A membrane topology, the NS2A topology of the JEV SD12 strain was predicted using TMHMM2 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/).

Statistics.

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from triplicate experiments and were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistically significant differences were assessed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student's t test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2022YFD1800100) awarded to Y.Q., the Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (no. ZD2021CY001) awarded to Z.M., the Project of Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (no. 22N41900400) awarded to Z.M., the Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 32273096) awarded to Z.M., the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (no. Y2020PT40) awarded to J.W., and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (no. 19ZR1469000) awarded to J.W. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jianchao Wei, Email: jianchaowei@shvri.ac.cn.

Zhiyong Ma, Email: zhiyongma@shvri.ac.cn.

Rebecca Ellis Dutch, University of Kentucky College of Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mansfield KL, Hernández-Triana L, Banyard AC, Fooks AR, Johnson N. 2017. Japanese encephalitis virus infection, diagnosis and control in domestic animals. Vet Microbiol 201:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unni SK, Růžek D, Chhatbar C, Mishra R, Johri MK, Singh SK. 2011. Japanese encephalitis virus: from genome to infectome. Microbes Infect 13:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wahaab A, Liu K, Hameed M, Anwar MN, Kang L, Li C, Ma X, Wajid A, Yang Y, Khan UH, Wei J, Li B, Shao D, Qiu Y, Ma Z. 2021. Identification of cleavage sites proteolytically processed by NS2B-NS3 protease in polyprotein of Japanese encephalitis virus. Pathogens 10:102. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yun SI, Lee YM. 2018. Early events in Japanese encephalitis virus infection: viral entry. Pathogens 7:68. doi: 10.3390/pathogens7030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Elsen K, Quek JP, Luo D. 2021. Molecular insights into the flavivirus replication complex. Viruses 13:956. doi: 10.3390/v13060956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie X, Gayen S, Kang C, Yuan Z, Shi PY. 2013. Membrane topology and function of dengue virus NS2A protein. J Virol 87:4609–4622. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02424-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie X, Zou J, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Routh AL, Kang C, Popov VL, Chen X, Wang Q-Y, Dong H, Shi P-Y. 2019. Dengue NS2A protein orchestrates virus assembly. Cell Host Microbe 26:606–622.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, Xie X, Xia H, Zou J, Huang L, Popov VL, Chen X, Shi P-Y. 2019. Zika virus NS2A-mediated virion assembly. mBio 10:e02375-19. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02375-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung JY, Pijlman GP, Kondratieva N, Hyde J, Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA. 2008. Role of nonstructural protein NS2A in flavivirus assembly. J Virol 82:4731–4741. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00002-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackenzie JM, Khromykh AA, Jones MK, Westaway EG. 1998. Subcellular localization and some biochemical properties of the flavivirus Kunjin nonstructural proteins NS2A and NS4A. Virology 245:203–215. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nemésio H, Villalaín J. 2014. Membrane interacting regions of dengue virus NS2A protein. J Phys Chem B 118:10142–10155. doi: 10.1021/jp504911r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voßmann S, Wieseler J, Kerber R, Kümmerer BM. 2015. A basic cluster in the N terminus of yellow fever virus NS2A contributes to infectious particle production. J Virol 89:4951–4965. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03351-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu RH, Tsai MH, Chao DY, Yueh A. 2015. Scanning mutagenesis studies reveal a potential intramolecular interaction within the C-terminal half of dengue virus NS2A involved in viral RNA replication and virus assembly and secretion. J Virol 89:4281–4295. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03011-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajima S, Taniguchi S, Nakayama E, Maeki T, Inagaki T, Lim CK, Saijo M. 2020. Amino acid at position 166 of NS2A in Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) is associated with in vitro growth characteristics of JEV. Viruses 12:709. doi: 10.3390/v12070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye Q, Li XF, Zhao H, Li SH, Deng YQ, Cao RY, Song KY, Wang HJ, Hua RH, Yu YX, Zhou X, Qin ED, Qin CF. 2012. A single nucleotide mutation in NS2A of Japanese encephalitis-live vaccine virus (SA14-14-2) ablates NS1' formation and contributes to attenuation. J Gen Virol 93:1959–1964. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043844-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tu YC, Yu CY, Liang JJ, Lin E, Liao CL, Lin YL. 2012. Blocking double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase PKR by Japanese encephalitis virus nonstructural protein 2A. J Virol 86:10347–10358. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00525-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bera AK, Kuhn RJ, Smith JL. 2007. Functional characterization of cis and trans activity of the flavivirus NS2B-NS3 protease. J Biol Chem 282:12883–12892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kümmerer BM, Rice CM. 2002. Mutations in the yellow fever virus nonstructural protein NS2A selectively block production of infectious particles. J Virol 76:4773–4784. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.10.4773-4784.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Shen L, Xu Z, Liu W, Li A, Xu J. 2022. Protein palmitoylation modification during viral infection and detection methods of palmitoylated proteins. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12:821596. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.821596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sobocińska J, Roszczenko-Jasińska P, Ciesielska A, Kwiatkowska K. 2017. Protein palmitoylation and its role in bacterial and viral infections. Front Immunol 8:2003. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.02003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chai K, Wang Z, Xu Y, Zhang J, Tan J, Qiao W. 2020. Palmitoylation of the bovine foamy virus envelope glycoprotein is required for viral replication. Viruses 13:31. doi: 10.3390/v13010031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu MJ, Shanmugam S, Welsch C, Yi M. 2019. Palmitoylation of hepatitis C virus NS2 regulates its subcellular localization and NS2-NS3 autocleavage. J Virol 94:e00906-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00906-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demers A, Ran Z, Deng Q, Wang D, Edman B, Lu W, Li F. 2014. Palmitoylation is required for intracellular trafficking of influenza B virus NB protein and efficient influenza B virus growth in vitro. J Gen Virol 95:1211–1220. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.063511-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gouttenoire J, Pollán A, Abrami L, Oechslin N, Mauron J, Matter M, Oppliger J, Szkolnicka D, Dao Thi VL, van der Goot FG, Moradpour D. 2018. Palmitoylation mediates membrane association of hepatitis E virus ORF3 protein and is required for infectious particle secretion. PLoS Pathog 14:e1007471. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramsey J, Renzi EC, Arnold RJ, Trinidad JC, Mukhopadhyay S. 2017. Palmitoylation of Sindbis virus TF protein regulates its plasma membrane localization and subsequent incorporation into virions. J Virol 91:e02000-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02000-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Xie X, Zou J, Xia H, Shan C, Chen X, Shi PY. 2019. Genetic and biochemical characterizations of Zika virus NS2A protein. Emerg Microbes Infect 8:585–602. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1598291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma X, Li C, Xia Q, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Wahaab A, Liu K, Li Z, Li B, Qiu Y, Wei J, Ma Z. 2022. Construction of a recombinant Japanese encephalitis virus with a hemagglutinin-tagged NS2A: a model for an analysis of biological characteristics and functions of NS2A during viral infection. Viruses 14:706. doi: 10.3390/v14040706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brigidi GS, Bamji SX. 2013. Detection of protein palmitoylation in cultured hippocampal neurons by immunoprecipitation and acyl-biotin exchange (ABE). J Vis Exp 18:50031. doi: 10.3791/50031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jennings BC, Nadolski MJ, Ling Y, Baker MB, Harrison ML, Deschenes RJ, Linder ME. 2009. 2-Bromopalmitate and 2-(2-hydroxy-5-nitro-benzylidene)-benzo[b]thiophen-3-one inhibit DHHC-mediated palmitoylation in vitro. J Lipid Res 50:233–242. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800270-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren J, Wen L, Gao X, Jin C, Xue Y, Yao X. 2008. CSS-Palm 2.0: an updated software for palmitoylation sites prediction. Protein Eng Des Sel 21:639–644. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzn039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bijlmakers MJ, Marsh M. 2003. The on-off story of protein palmitoylation. Trends Cell Biol 13:32–42. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng X, Wei J, Shi Z, Yan W, Wu Z, Shao D, Li B, Liu K, Wang X, Qiu Y, Ma Z. 2016. Tumor suppressor p53 functions as an essential antiviral molecule against Japanese encephalitis virus. J Genet Genomics 43:709–712. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie X, Zou J, Puttikhunt C, Yuan Z, Shi PY. 2015. Two distinct sets of NS2A molecules are responsible for dengue virus RNA synthesis and virion assembly. J Virol 89:1298–1313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02882-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]