ABSTRACT

Viral diseases are a significant risk to the aquaculture industry. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) has been reported to be involved in regulating viral activity in mammals, but its regulatory effect on viruses in teleost fish remains unknown. Here, the role of the TRPV4-DEAD box RNA helicase 1 (DDX1) axis in viral infection was investigated in mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi). Our results showed that TRPV4 activation mediates Ca2+ influx and facilitates infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV) replication, whereas this promotion was nearly eliminated by an M709D mutation in TRPV4, a channel Ca2+ permeability mutant. The concentration of cellular Ca2+ increased during ISKNV infection, and Ca2+ was critical for viral replication. TRPV4 interacted with DDX1, and the interaction was mediated primarily by the N-terminal domain (NTD) of TRPV4 and the C-terminal domain (CTD) of DDX1. This interaction was attenuated by TRPV4 activation, thereby enhancing ISKNV replication. DDX1 could bind to viral mRNAs and facilitate ISKNV replication, which required the ATPase/helicase activity of DDX1. Furthermore, the TRPV4-DDX1 axis was verified to regulate herpes simplex virus 1 replication in mammalian cells. These results suggested that the TRPV4-DDX1 axis plays an important role in viral replication. Our work provides a novel molecular mechanism for host involvement in viral regulation, which would be of benefit for new insights into the prevention and control of aquaculture diseases.

IMPORTANCE In 2020, global aquaculture production reached a record of 122.6 million tons, with a total value of $281.5 billion. Meanwhile, frequent outbreaks of viral diseases have occurred in aquaculture, and about 10% of farmed aquatic animal production has been lost to infectious diseases, resulting in more than $10 billion in economic losses every year. Therefore, an understanding of the potential molecular mechanism of how aquatic organisms respond to and regulate viral replication is of great significance. Our study suggested that TRPV4 enables Ca2+ influx and interactions with DDX1 to collectively promote ISKNV replication, providing novel insights into the roles of the TRPV4-DDX1 axis in regulating the proviral effect of DDX1. This advances our understanding of viral disease outbreaks and would be of benefit for studies on preventing aquatic viral diseases.

KEYWORDS: TRPV4, Ca2+, DDX1, ISKNV, HSV-1

INTRODUCTION

The transient receptor potentials (TRPs), as canonical cationic channels, are involved in a wide array of cellular biological processes (1). Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4), the calcium-permeable nonselective cation channel, acts as a pivotal signal transducer that is activated by various stimuli ranging from hypotonicity (2–4) to mechanical stress (5) and heat (6, 7). TRPV4 is generally regarded as an important temperature sensor in vertebrates. When activated by heat, TRPV4 can induce calcium influx for precise temperature sensing (8). Apart from that, TRPV4 links calcium influx to viral infectivity (9).

DEAD box RNA helicases (DDXs), a family of classical ATP-dependent helicases, play important roles in cellular processes such as RNA processing, metabolism, and innate immunity (10). DDX1, a member of the DEAD box protein family, participates in viral replication, which is “hijacked” by viruses for their promotion and is also involved in the host’s antiviral innate immune response in some cases (11–16). DDX1 is a highly competitive target in the ongoing “arms race” between a virus and the host’s immune system.

In recent years, global aquaculture production has continued to grow and hit record highs. In light of the statistics, the aquaculture industry provided about 17% of the animal protein for human consumption (17). Aquaculture plays an increasingly important role in providing food and nutrition for humans. However, in the context of global climate change, including shifts in water temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and acidification, the abundance and distribution of fishery resources have been seriously affected, and the prospect of the sustainable development of aquaculture still poses serious concerns (18). The deterioration of environmental factors, coupled with high-density farming, has often been relevant in continuous disease outbreaks in aquaculture, which have caused huge economic losses and potential threats to human health.

Infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV), which is a double-stranded DNA virus and a type species of the genus Megalocytivirus of the family Iridoviridae (19), is responsible for huge losses to fish farming because of its extremely high infection and lethality rates (20). In the present study, we focused on the mechanism by which the interaction between TRPV4 and DDX1 regulates ISKNV replication.

RESULTS

Activated TRPV4 facilitates viral replication.

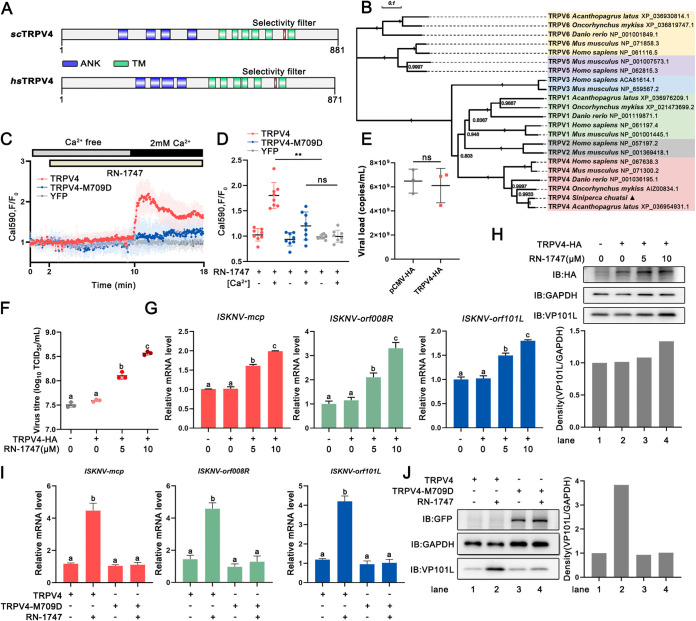

To investigate the role of teleost fish TRPV4 in virus infection, the potential function of TRPV4 from mandarin fish (Siniperca chuatsi) in ISKNV infection was explored. The characteristics of S. chuatsi TRPV4 were investigated by domain and phylogenetic analyses. As shown in Fig. 1A, the protein domain properties of S. chuatsi TRPV4 closely resemble those of the mammalian orthologs, characterized by four ankyrin (ANK) repeats and six transmembrane (TM) domains. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that S. chuatsi TRPV4 belongs to the TRPV4 family of the TRP superfamily (Fig. 1B). Activated TRPV4 can induce calcium influx (7). The relevance between Ca2+ and the S. chuatsi TRPV4 channel was studied. The activation of TRPV4 by RN-1747, an agonist of TRPV4 (21), resulted in an increase in the intracellular calcium concentration. This effect was abolished in the S. chuatsi TRPV4 mutant (TRPV4-M709D) (22) that impairs channel Ca2+ influx (Fig. 1C and D).

FIG 1.

Activated TRPV4 facilitates viral replication. (A) Protein domains of S. chuatsi TRPV4 (scTRPV4) predicted by the SMART program. hsTRPV4, Homo sapiens TRPV4. (B) Phylogenetic tree based on multiple alignments of S. chuatsi TRPV4 and TRPV proteins from the other species. The neighbor-joining tree was generated using MEGA X, and a 1,000-replicate bootstrap analysis was performed. (C) Intracellular Ca2+ signals (Calbryte-590) obtained from MFF-1 cells transfected with peYFP-N1 (n = 8) (gray line), TRPV4-eYFP-N1 (n = 8) (red line), and TRPV4-M709D-eYFP-N1 (n = 8) (blue line). Cells were exposed to 10 μM RN-1747 in the absence and presence of extracellular Ca2+, as indicated. (D) Quantitative data for the Calbryte-590 fluorescence intensity (mean ± SD) from panel C. (E) Absolute quantification of the viral load (genomic copies) of ISKNV in MFF-1 cells transfected with pCMV-HA or TRPV4-HA and then infected with ISKNV at an MOI of 1 was performed by qPCR. ns, not significant. (F) MFF-1 cells were transfected with pCMV-HA or TRPV4-HA for 24 h, followed by infection with ISKNV and treatment with different concentrations of RN-1747 (0, 5, and 10 μM). Cells were collected, and the viral titers were then measured by a TCID50 assay. (G and H) ISKNV replication in MFF-1 cells transfected with pCMV-HA or TRPV4-HA. Cells were treated with different concentrations of RN-1747 (0, 5, and 10 μM) at the time of viral infection. (G) The relative mRNA levels of ISKNV-mcp, ISKNV-orf008R, and ISKNV-orf101L were determined via RT-qPCR. (H) The expression level of ISKNV-VP101L was determined by Western blotting. (I and J) ISKNV replication in MFF-1 cells transfected with TRPV4-eYFP-N1 or TRPV4-M709D-eYFP-N1. Cells were treated with 10 μM RN-1747 during viral infection. (I) The relative mRNA levels of ISKNV-mcp, ISKNV-orf008R, and ISKNV-orf101L were determined via RT-qPCR. (J) The expression level of ISKNV-VP101L was determined by Western blotting. All immunoblot (IB) data are representative of data from three independent experiments with similar results. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance is indicated by lowercase letters. The different and same letters indicate the presence and absence of significant differences, respectively.

To clarify the link between S. chuatsi TRPV4 and ISKNV replication, we transfected the cells with an empty vector or hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged TRPV4 (TRPV4-HA) for 24 h, followed by ISKNV infection at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. As shown in Fig. 1E to H, the overexpression of TRPV4 had no significant effect on ISKNV replication compared with the control group. Importantly, the treatment of TRPV4-transfected cells with RN-1747 obviously increased the virus titer (Fig. 1F), the relative mRNA expression levels of ISKNV (Fig. 1G), and the level of ISKNV-VP101L (Fig. 1H) in a dose-dependent manner. However, the promotion of ISKNV replication due to the activation of TRPV4 by RN-1747 was eliminated (Fig. 1I and J) as a result of a mutation of M709 (TRPV4-M709D) that renders the TRPV4 channel insensitive to RN-1747. The above-described results suggested that activated TRPV4 facilitated ISKNV replication and that this effect was dependent on channel Ca2+ influx.

Ca2+ is critical for viral replication.

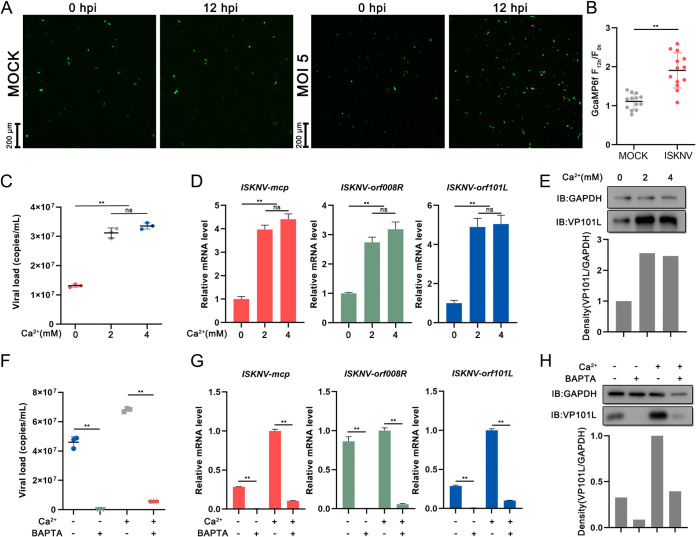

Activated TRPV4 induces Ca2+ influx (7, 23, 24). Several mammalian viruses are adept at utilizing intracellular Ca2+ to benefit their life cycles and pathogenesis (25–31). To explore the role of Ca2+ in ISKNV replication, the levels of intracellular Ca2+ using GCaMP6f signals were determined. The results showed that the level of intracellular Ca2+ at 12 h postinfection (hpi) was elevated in ISKNV-infected cells compared with those in mock-infected cells (Fig. 2A). The quantitation of the GCaMP6f signals showed a significant increase at 12 hpi (Fig. 2B). To understand the relationship between Ca2+ and ISKNV replication, the levels of extracellular and intracellular Ca2+ were manipulated to investigate the effects on ISKNV replication. As shown in Fig. 2C to E, in contrast to the normal medium group (~2 mM Ca2+), doubling the extracellular Ca2+ concentration (~4 mM) did not affect ISKNV replication, but the level of ISKNV replication was significantly reduced in the context of Ca2+-free medium (~0 mM). Subsequently, to investigate the role of intracellular Ca2+ during ISKNV replication, we treated the cells with BAPTA-AM (1,2-bis[2-aminophenoxy]ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid tetrakis [acetoxymethyl ester]), which is a selective chelator for calcium and is widely used to buffer cytosolic Ca2+ (32). As shown in Fig. 2F to H, the viral loads (Fig. 2F), mRNA levels (Fig. 2G), and protein levels (Fig. 2H) were significantly decreased in the 2 mM Ca2++BAPTA group (BAPTA-AM added to normal medium) compared with those in the negative-control group (normal medium [2 mM Ca2+]). This inhibition was more pronounced in the 0 mM Ca2++BAPTA group (BAPTA-AM added to Ca2+-free medium). These results indicated that Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ were critical for ISKNV replication.

FIG 2.

Ca2+ is critical for viral replication. (A) Representative images at 0 and 12 hpi of mock-infected (left) and ISKNV-infected (MOI = 5) (right) GCaMP6f cells. (B) Quantification of GCaMP6f fluorescence from panel A. (C to E) Buffering out extracellular calcium hinders ISKNV replication, significantly reducing the total viral load (C), the relative viral mRNA level (D), and the level of the viral protein VP101L (E), and excess extracellular Ca2+ (~4 mM) does not impact replication. (F to H) The stunted ISKNV replication in the presence of BAPTA-AM (20 μM) was detected via qPCR (F), RT-qPCR (G), and Western blot analysis (H). As a Ca2+ chelator, BAPTA-AM can significantly reduce the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

TRPV4 interacts with DDX1.

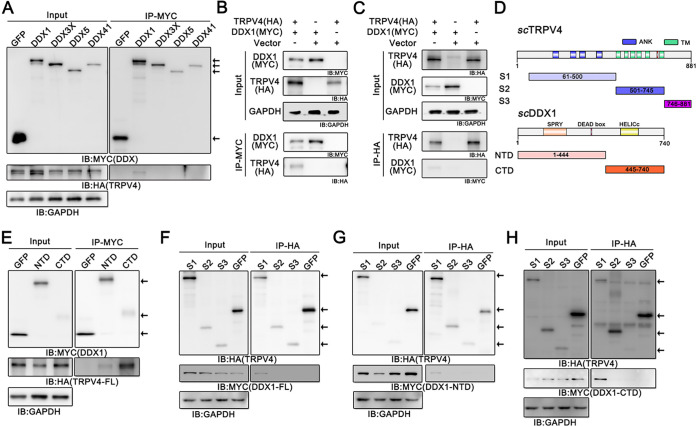

The TRPV4 cation channel binds to DDX3X and regulates its function, as described previously (9). To investigate the molecular mechanisms of activated TRPV4 facilitating ISKNV replication apart from Ca2+ influx, we detected the interaction of TRPV4 with members of the DDX helicase family of proteins (DDX1, DDX3X, DDX5, and DDX41) from S. chuatsi by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays. As shown in Fig. 3A, S. chuatsi TRPV4 specifically bound to DDX1 but not DDX3X, DDX5, or DDX41. Given this, the interactions between TRPV4 and DDX1 were further verified. Using anti-Myc magnetic beads to immunoprecipitate DDX1, TRPV4 as a coprecipitant of DDX1 was observed (Fig. 3B). Likewise, DDX1 was also identified from immunoprecipitates of TRPV4 (Fig. 3C) using anti-HA magnetic beads to immunoprecipitate TRPV4. These results suggested that S. chuatsi TRPV4 interacted with DDX1.

FIG 3.

TRPV4 interacts with DDX1. (A) Results of the detection of the interactions between TRPV4 and S. chuatsi DDX family proteins. (B and C) Co-IP of TRPV4-HA and Myc-DDX1 in FHM cells. (B) TRPV4 as a coprecipitant of DDX1; (C) the reverse result. (D) Schematic showing the domain structures of scTRPV4 and scDDX1. The amino acid residues of the TRPV4 and DDX1 fragments used in this study are indicated. S1, aa 61 to 500 of TRPV4; S2, aa 501 to 745 of TRPV4; S3, aa 746 to 881 of TRPV4; NTD, aa 1 to 444 of DDX1; CTD, aa 445 to 740 of DDX1. (E) Myc immunoprecipitates from lysates of FHM cells expressing the Myc-tagged NTD and CTD were immunoblotted for the detection of TRPV4. (F to H) HA immunoprecipitated from the lysates of FHM cells expressing HA-tagged S1, S2, and S3 of TRPV4 were immunoblotted for the detection of full-length DDX1 (F) and the NTD (G) and CTD (H) of DDX1.

The TRPV4 protein is composed of 881 amino acids (aa), containing an N-terminal domain (NTD) and a C-terminal domain (CTD). As shown in Fig. 3D, the NTD (aa 1 to 500) contains four ANK repeats that are critical for channel oligomerization (33). The in-between sequences (aa 501 to 745) comprise six TM segments, with a putative pore loop between TM5 and TM6 (34). The CTD (aa 746 to 881) presents a calmodulin-binding site (35, 36) and a PDZ-binding motif-like domain responsible for the targeting or anchoring of ion channels and transporters (37). The DDX1 protein, consisting of 740 aa, contains variable N- and C-terminal regions that are considered the docking sites for interactions with RNA, proteins, or other biomolecules (38). To map the regions of interactions between S. chuatsi TRPV4 and DDX1, we constructed their mutants and explored their interaction domains. Fathead minnow (FHM) cells overexpressing the NTD or CTD of DDX1 together with full-length TRPV4 (Fig. 3E), truncated fragments of TRPV4 together with full-length DDX1 (Fig. 3F), and the NTD (Fig. 3G) or CTD (Fig. 3H) of DDX1 together with truncated fragments of TRPV4 were used to carry out co-IP experiments. The results showed that the CTD of DDX1 was the main TRPV4-interacting domain and that fragment S1 of TRPV4 was the main DDX1-interacting domain (Fig. 3E to H), whereas the NTD of DDX1 interacted weakly with TRPV4 (Fig. 3E to G). These observations indicated that the interaction between TRPV4 and DDX1 was mediated predominantly by the domains spanning aa 61 to 500 (containing the ankyrin repeats) of TRPV4 and the CTD of DDX1 (containing the helicase superfamily C-terminal [HELICc] domain).

DDX1 has a proviral effect, benefiting from its ATPase/helicase activity.

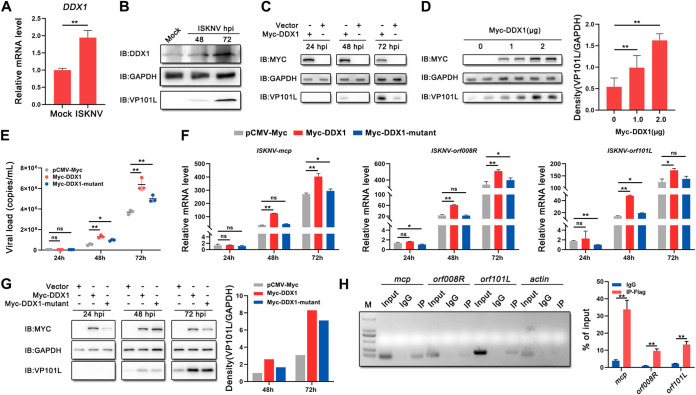

DDX1 is involved in the host’s innate immune response by inhibiting viral replication or being hijacked by the virus (11–15). However, the role of teleost fish DDX1 in the response to viral infection remains unknown. We found that the mRNA (Fig. 4A) and protein (Fig. 4B) levels of endogenous DDX1 were upregulated after ISKNV infection. To assess the role of DDX1 during ISKNV infection, we infected cells transfected with Myc-DDX1 or an empty vector with ISKNV at 24 h posttransfection (hpt). As shown in Fig. 4C, the protein levels of ISKNV-VP101L were significantly increased at 48 and 72 hpi in Myc-DDX1-transfected cells compared with those in pCMV-Myc-transfected cells. Consistent with these results, the overexpression of different doses of Myc-DDX1 also upregulated the ISKNV-VP101L level in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4D).

FIG 4.

DDX1 has a proviral effect, benefiting from its ATPase/helicase activity. (A and B) Endogenous DDX1 mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels after mock infection or ISKNV infection (MOI = 1). (C) Expression levels of ISKNV-VP101L determined by Western blotting in MFF-1 cells overexpressing Myc-DDX1 or pCMV-Myc 24, 48, and 72 h after ISKNV infection (MOI = 1). (D) Expression levels of ISKNV-VP101L determined by Western blotting in MFF-1 cells overexpressing 0, 1, or 2 μg of the Myc-DDX1 plasmid at 72 hpi (MOI = 1). Quantitative analysis of the data obtained from two replicates was performed using ImageJ software. (E to G) ISKNV replication in MFF-1 cells transfected with pCMV-Myc, Myc-DDX1, or the Myc-DDX1 mutant. Cells were infected with ISKNV (MOI = 1) at 24 hpt and collected at 24, 48, and 72 hpi. (E) The viral loads (genomic copies) of ISKNV were determined by qPCR. (F) The relative mRNA levels of ISKNV-mcp, ISKNV-orf008R, and ISKNV-orf101L were determined by RT-qPCR. (G) The expression level of ISKNV-VP101L was determined by Western blotting. (H) Interaction between FLAG-tagged DDX1 protein and ISKNV RNA analyzed by PCR (left) and RT-qPCR (right). The agarose gel electrophoresis schematic shows the amplification efficiency of PCR products derived from the lysates. The enrichment of ISKNV RNA pulled down with anti-FLAG antibody or IgG is indicated as a percentage of the input. All immunoblot data are representative of data from three independent experiments with similar results. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). M, molecular weight marker.

The ATPase/helicase activity of DDX1 is essential for viral replication (15). To explore the effect of the ATPase/helicase activity of DDX1 on ISKNV replication, a mutation (DDX1-DECD370-373AAAA) in the conserved DEAD box motif was constructed to abrogate its ATPase/helicase activity. The replication of the virus was analyzed in cells transfected with the Myc-DDX1 mutant or Myc-DDX1 (wild-type DDX1) and then infected with ISKNV. The results showed that the viral loads (Fig. 4E), mRNA levels (Fig. 4F), and protein levels (Fig. 4G) were significantly attenuated in cells transfected with the Myc-DDX1 mutant compared with those in cells transfected with Myc-DDX1, indicating that the promotion of ISKNV replication by DDX1 was dependent mainly on the ATPase/helicase activity of DDX1. To validate the link between DDX1 and ISKNV, we carried out RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments. The observations showed that the amounts of viral mRNA (ISKNV-mcp, ISKNV-orf008R, or ISKNV-orf101L) immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody were far larger than those immunoprecipitated with control IgG (Fig. 4H), suggesting that DDX1 could bind to ISKNV RNA.

The interplay of TRPV4-DDX1 regulates ISKNV replication.

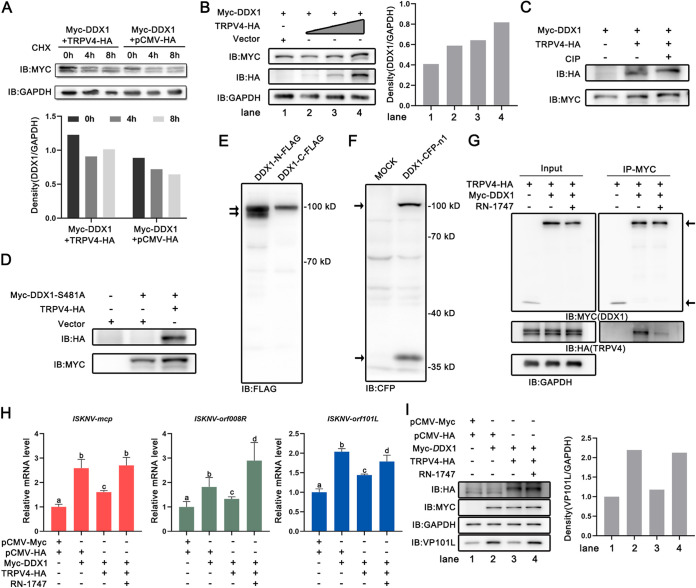

To figure out the effect of the interaction of TRPV4 and DDX1 on the protein level of DDX1, cells were cotransfected with DDX1 and the empty vector/TRPV4, followed by treatment with cycloheximide (CHX) (an inhibitor of protein synthesis in eukaryotes) for 0, 4, and 8 h, and their protein levels were then measured by a Western blot (WB) assay. As shown in Fig. 5A, the levels of DDX1 were significantly decreased in cells treated with CHX at 4 h and 8 h compared with those at 0 h; the levels of the DDX1 protein in cells coexpressing TRPV4 and DDX1 were higher than those in cells coexpressing the empty vector and DDX1 at the indicated time, indicating that TRPV4 could stabilize the DDX1 protein content. Cells were overexpression of DDX1 and different doses of the TRPV4 vector. As shown in Fig. 5B, the level of the DDX1 protein was increased by the overexpression of TRPV4 in a dose-dependent manner. Meanwhile, a lower-molecular-weight band of the DDX1 protein was observed. To investigate whether TRPV4 has an influence on the phosphorylation modification of DDX1, cells were coexpressed DDX1 and TRPV4, and the lysates were then treated with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP) (a catalyst of the dephosphorylation reaction) (Fig. 5C). Cells were coexpressed DDX1-S481A (DDX1-phosphorylated mutant construct) and the empty vector/TRPV4 (Fig. 5D). The results showed that the lower-molecular-weight band of DDX1 had no change (Fig. 5C and D). These observations indicated that the interplay between TRPV4 and DDX1 influenced not the phosphorylation but the stabilization of DDX1. To explore whether the two bands of DDX1 were different splicing isoforms, DDX1 with an N-terminal FLAG tag or a C-terminal FLAG tag was transfected and measured using a WB assay. As shown in Fig. 5E, DDX1 with an N-terminal FLAG tag showed two bands, whereas DDX1 with a C-terminal FLAG tag showed only one band, indicating that the modification of DDX1 was related to splicing. At the same time, cells transfected with DDX1-CFP-N1 (cyan fluorescent protein [CFP] tag located at the C terminus of DDX1) were collected for WB assays using anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody, and wild-type DDX1 as well as the DDX1 splicing fragment with the CFP tag were observed (Fig. 5F), which further demonstrated that the two bands of DDX1 were different splicing isoforms. To explore the effect of activated TRPV4 on DDX1, cells coexpressing TRPV4 and DDX1 were treated with RN-1747 to carry out co-IP assay using anti-Myc magnetic beads to immunoprecipitate DDX1. The band of TRPV4 (Fig. 5G, right lane) as the coprecipitant of DDX1 was weak in the RN-1747 treatment group compared with that in the normal group (Fig. 5G, middle lane), indicating that activated TRPV4 attenuated the interaction with DDX1. The above-described observations suggested that the connection between TRPV4 and DDX1 might be due to the interaction and the dissociation of both.

FIG 5.

The interplay of TRPV4-DDX1 regulates ISKNV replication. (A) Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates cotransfected with the Myc-DDX1 plasmid and an empty vector or the TRPV4-HA plasmid. Cells were treated with CHX for 0, 4, and 8 h before sampling. (B) Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates cotransfected with the Myc-DDX1 plasmid and different doses of the TRPV4-HA plasmid. (C) Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates cotransfected with the Myc-DDX1 plasmid and the TRPV4-HA plasmid or an empty vector. Protein dephosphorylation was conducted at 37°C for 45 min in 100-μL reaction mixtures made up of 100 μg of cell protein and 10 U of CIP. (D) Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates cotransfected with the Myc-DDX1-S481A plasmid and the TRPV4-HA plasmid or an empty vector. (E and F) Immunoblot analysis of cell lysates overexpressing the DDX1-N-FLAG, DDX1-C-FLAG, or DDX1-CFP-N1 plasmid. (G) Co-IP of TRPV4-HA and Myc-DDX1 in FHM cells. Cells were treated with RN-1747 or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (negative control) overnight before sampling. (H and I) ISKNV replication in MFF-1 cells transfected with different plasmids. Cells were treated with 10 μM RN-1747 or DMSO at the time of viral infection. (H) The relative mRNA levels of ISKNV-mcp, ISKNV-orf008R, and ISKNV-orf101L were determined via RT-qPCR. (I) The expression level of ISKNV-VP101L was determined by Western blotting. All immunoblot data are representative of data from three independent experiments with similar results. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance is indicated by lowercase letters. The different and same letters indicate the presence and absence of significant differences, respectively.

To further investigate the influence of the interplay between TRPV4 and DDX1 on ISKNV replication, cells were cotransfected with various plasmids and then infected with ISKNV. As shown in Fig. 5H, the levels of the viral mRNAs (ISKNV-mcp, ISKNV-orf008R, and ISKNV-orf101L) were significantly increased in cells coexpressing TRPV4 and DDX1 and treated with RN-1747 compared to cells coexpressing TRPV4 and DDX1. The levels of viral protein (ISKNV-VP101L) showed similar results (Fig. 5I). These results together suggested that activated TRPV4 weakened its interaction with DDX1, thereby benefiting the proviral effect of DDX1.

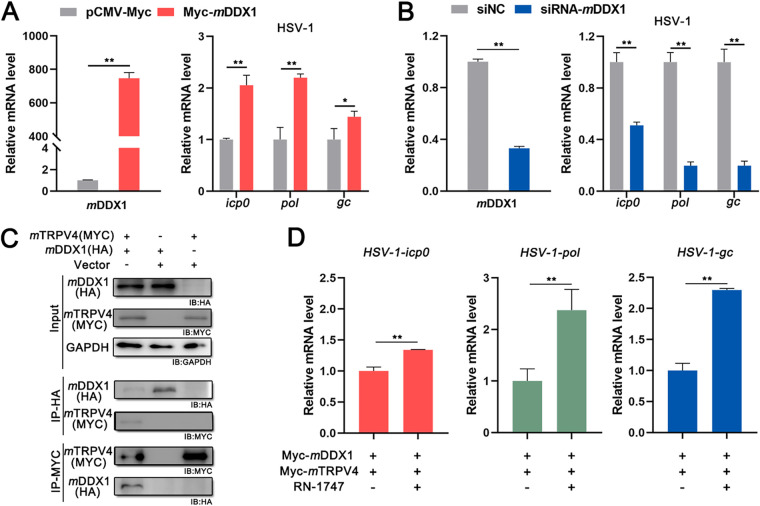

The TRPV4-DDX1 axis regulates HSV-1 replication.

To investigate whether the mechanism of the TRPV4-DDX1 axis regulates mammalian virus replication in the same manner as the mechanism in teleost fish, Mus musculus DDX1 (mDDX1) promoting herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) replication, the mDDX1-M. musculus TRPV4 (mTRPV4) interaction, and mTRPV4 activation regulating the proviral effect of DDX1 were demonstrated in baby hamster kidney 21 (BHK-21) cells. Cells transfected with Myc-mDDX1/empty vector or small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting mDDX1 (siRNA-mDDX1)/negative-control siRNA (siNC) were infected with HSV-1 at 24 hpt, and the levels of HSV-1 mRNAs were determined. As shown in Fig. 6A, the relative levels of viral mRNAs (HSV-1-icp0, HSV-1-pol, or HSV-1-gc) were significantly increased in Myc-mDDX1-transfected cells compared with those in pCMV-Myc-transfected cells; in contrast, the relative levels of viral mRNAs were remarkably decreased in siRNA-mDDX1-transfected cells (Fig. 6B). These results indicated that mDDX1 could promote HSV-1 replication. Furthermore, mDDX1 interacted with mTRPV4, as indicated by co-IP assays (Fig. 6C); the relative levels of HSV-1 mRNAs (HSV-1-icp0, HSV-1-pol, or HSV-1-gc) were significantly increased in cells treated with RN-1747 compared with control cells coexpressing mTRPV4 and mDDX1 (Fig. 6D). These results suggested that the TRPV4-DDX1 axis regulates the proviral effect of DDX1 for HSV-1, consistent with the results for ISKNV.

FIG 6.

The TRPV4-DDX1 axis regulates HSV-1 replication. (A) HSV-1 replication in BHK-21 cells transfected with pCMV-Myc or Myc-mDDX1. Cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) at 24 hpt and collected at 48 hpi. The relative mRNA levels of mDDX1, HSV-1-icp0, HSV-1-pol, and HSV-1-gc were determined by RT-qPCR. (B) HSV-1 replication in BHK-21 cells transfected with siNC or siRNA-mDDX1. Cells were infected with HSV-1 (MOI = 1) at 24 hpt and collected at 48 hpi. The relative mRNA levels of mDDX1, HSV-1-icp0, HSV-1-pol, and HSV-1-gc were determined by RT-qPCR. (C) Co-IP of Myc-tagged mTRPV4 and HA-tagged mDDX1 in BHK-21 cells. (D) HSV-1 replication in BHK-21 cells transfected with Myc-mDDX1 and Myc-mTRPV4. Cells were treated with 10 μM RN-1747 or DMSO during viral infection. The relative mRNA levels of HSV-1-icp0, HSV-1-pol, and HSV-1-gc were determined via RT-qPCR. Data are shown as means ± SD (n = 3). Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks.

DISCUSSION

Aquaculture is an indispensable productive activity for human beings. As aquaculture production continues to grow, so does the incidence of viral disease, raising strong concerns about the prospect of the sustainable development of aquaculture. Viral disease outbreaks in aquaculture have caused huge economic losses and harmed human health. Therefore, understanding the potential molecular mechanism of how aquatic organisms respond to and regulate viral replication is of great significance.

In the present study, models of mandarin fish (S. chuatsi) and ISKNV were selected for research. S. chuatsi TRPV4 could be activated by RN-1747 and induced Ca2+ influx after activation. TRPV4 itself had no effect on ISKNV, but activated TRPV4 significantly promoted ISKNV replication, and this effect was nearly eliminated by an M709D mutation. This mutation may be related to the inhibition of Ca2+ channel permeability. Furthermore, a link between ISKNV and Ca2+ was found; that is, the cellular Ca2+ concentration was increased during ISKNV infection, and ISKNV replication benefited from Ca2+. In addition to Ca2+, a potential signaling pathway associated with the TRPV4-DDX1 axis affecting ISKNV replication was identified. Co-IP experiments revealed that TRPV4 interacted with DDX1 proteins but not with DDX3X/DDX5/DDX41, and the interaction was mediated primarily by the NTD of TRPV4 and the CTD of DDX1. This interaction was attenuated by TRPV4 channel activation by RN-1747, resulting in DDX1 dissociation, thereby increasing ISKNV replication levels. Meanwhile, DDX1 bound to ISKNV mRNA and facilitated ISKNV replication, which required the ATPase/helicase activity of DDX1. The molecular weight band of the DDX1 protein decreased, and a splicing effect was observed. The reason for splicing in DDX1 and the role of this process in viral infection should be explored.

TRPV4 participates in a variety of pathophysiological processes in cells. However, there have been few studies that have explored the effects of TRPV4 on innate immunity, especially against viruses. Jiang et al. (39) found that TRPV4 acts as a Ca2+-permeable channel and promotes herpes simplex virus 2 infection in human epithelial cells. Bai et al. (40) showed that TRPV4 may serve as one of the effectors that modulate the impact of breathing motions on the activation of protective innate immune responses in epithelial and endothelial cells, thereby suppressing influenza A virus replication. Kuebler et al. (41) identified TRPV4 as a promising target for protecting the alveolar-capillary barrier in severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Donate-Macian et al. (42) validated that TRPV4 inhibition provides an antiviral effect against the Zika virus. Recent research demonstrated that TRPV4 can regulate viral infectivity through the nuclear translocation of DDX3X, requiring the participation of the Ca2+/CaM/CaM KII pathway (9). Our results revealed that TRPV4 activation facilitates ISKNV replication, which is mediated by Ca2+ and the interaction between TRPV4 and DDX1. Overall, our data, in conjunction with those of previous studies, suggest that TRPV4 is a potential target of increasing importance in viral regulation. Thus, the roles of TRPV4 in host innate immunity and virus infection should be considered. An understanding of these roles can facilitate transformative developments in therapeutic applications against viruses.

DDX1 plays a two-sided role in viral infection. On the one hand, DDX1 can promote viral replication. For instance, the interaction of DDX1 with nonstructural protein 14 of the coronaviruses infectious bronchitis virus and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus enhances viral replication (11). DDX1 links with the Rev protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to facilitate viral assembly (12, 13). On the other hand, DDX1 can inhibit the replication of viruses, including transmissible gastroenteritis viruses (14), foot-and-mouth disease virus (15), Newcastle disease virus, and avian influenza virus (16), through the induction of the type I interferon signaling pathway. In the present study, we found that DDX1 promotes ISKNV replication by binding to viral RNA. Moreover, due to the low siRNA transfection efficiency of mandarin fish fry 1 (MFF-1) cells, BHK-21 cells were used for the reverse genetic validation of DDX1 function. The results showed that the overexpression of M. musculus DDX1 (mDDX1) promoted HSV-1 replication, and the knockdown of mDDX1 by siRNA inhibited HSV-1 replication. Notably, this result may deepen our understanding of HSV-1 and provide novel insights into HSV-1.

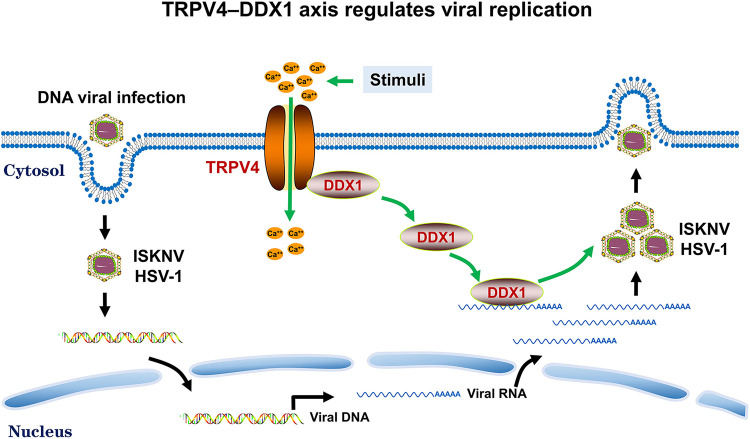

Here, we propose a novel molecular mechanism underlying the interplay between TRPV4 and DDX1 for the regulation of viral replication (Fig. 7). In a resting state, TRPV4 anchors DDX1. Upon TRPV4 activation, an increase in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration was accompanied by the dissociation of DDX1 from TRPV4. The dissociated DDX1 bound to ISKNV RNA and was hijacked by viruses to facilitate replication, thus benefiting the life cycles of the viruses. The applicability of this model was then tested using HSV-1 in BHK-21 cells. As expected, the results were consistent with those for the regulation of ISKNV in MFF-1 cells, demonstrating the universality of our proposed model. The regulation of RNA viruses by the TRP-DDX interaction was observed, as described in a previous study (11), but the mechanism of their interaction in the regulation of DNA viruses remains unclear. Our work provides a novel mechanism and research direction for the TRP-DDX interaction involved in DNA virus regulation. In summary, our work provides novel insights into the roles of the TRPV4-DDX1 axis in the regulation of the proviral effects of DDX1 and may contribute to the study of the molecular mechanism for host involvement in viral regulation.

FIG 7.

Model of the interplay between TRPV4 and DDX1 in the regulation of viral replication. TRPV4 anchors DDX1 in a resting state. Upon TRPV4 activation by stimuli (heat or RN-1747), the intracellular Ca2+ concentration increases, and DDX1 dissociates from TRPV4. Dissociated DDX1 is transported to bind to viral RNA and is hijacked by viruses to induce their translation. Altogether, the interaction between TRPV4 and DDX1 regulates viral replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

Mandarin fish fry (MFF-1) cells and fathead minnow (FHM) cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) at 27°C with 5% CO2 (43, 44). The baby hamster kidney 21 (BHK-21) cell line was kindly provided by Jin Lu from the Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention and was cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS at 37°C with 5% CO2. The ISKNV strain was separated and stored in our laboratory (45). The herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) strain was kindly provided by Yiping Li from the School of Medicine, SYSU. Cells were plated, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then infected with virus diluted in fresh medium at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. Subsequently, the DNA, RNA, and proteins were collected from the infected cells at the indicated time points for analysis.

Plasmid and mutant construction.

The full-length cDNA of S. chuatsi DDX1 was inserted into the pCMV-Myc vector (Clontech, Tokyo, Japan) to generate a Myc-tagged expression construct (named Myc-DDX1). The truncated fragments of DDX1 corresponding to aa 1 to 444 (containing the SPRY domain and DEAD box) and aa 445 to 740 (containing the HELICc domain) and the point mutant at aa positions 370 to 373 (DECD370-373AAAA), which was named the Myc-DDX1 mutant, were subcloned into the pCMV-Myc vector. The TRPV4-HA expression construct was generated by the insertion of an HA tag into the first extracellular loop of TRPV4. The fragments of TRPV4 corresponding to aa 61 to 500 (containing the ankyrin repeats and proline-rich domain), aa 501 to 745 (containing the transmembrane regions), and aa 746 to 881 were inserted into the pCMV-HA vector (Clontech, Tokyo, Japan) for the generation of HA-tagged expression constructs. Furthermore, the cDNA of TRPV4 and the TRPV4 mutant corresponding to M709D were cloned into the pEYFP-N1 vector (Clontech, Tokyo, Japan) for the generation of the TRPV4-eYFP (enhanced yellow fluorescent protein)-N1 and TRPV4-M709D-eYFP-N1 expression constructs, respectively. The related gene cloning primers used are listed in Table 1. All plasmids constructed in this article were sequenced correctly and verified for expression.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for PCR cloning in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| Myc-DDX1-EcoR I-F | CGGAATTCCGGCAGCGTTTACTGAAATG |

| Myc-DDX1-Not I-R | ATAAGAATGCGGCCGCTCAGAAGGCTTTGAAAAGTTG |

| Myc-DDX3X-EcoR I-F | CGGAATTCCGAGTCATGTGGTCGTTGATAATC |

| Myc-DDX3X-Kpn I-R | GGGGTACCCTAGTTGCCCCACCAATCCAC |

| Myc-DDX5-EcoR I-F | CGGAATTCCGCCTGGATATTCCGACAGAG |

| Myc-DDX5-Kpn I-R | GGGGTACCTTACTGAGAGAACTGAGGAGG |

| Myc-DDX41-EcoR I-F | CGGAATTCCGGAGACCGACAATCGACCC |

| Myc-DDX41-Kpn I-R | GGGGTACCTTAGAAGTCCATTGAGCTATGAGC |

| DDX1-mutant-overlap F | CTTTCTAGTCCTGGCAGCAGCAGCAGGTCTTCTGTC |

| DDX1-mutant-overlap R | GACAGAAGACCTGCTGCTGCTGCCAGGACTAGAAAG |

| TRPV4-eYFP-N1-EcoR I-F | CCGAATTCGGATGCAGCTCACTCAGAA |

| TRPV4-eYFP-N1-SaI I-R | TTGTCGACAAGTGCCTGTGCGTCAG |

| TRPV4-M709D-overlap F | GCTGACAATTGGGGACGGAGAACTGGACATGATCC |

| TRPV4-M709D-overlap R | GGATCATGTCCAGTTCTCCGTCCCCAATTGTCAGC |

| Myc/HA-mDDX1-Xho I-F | CTGCTCGAGGTATGGCGGCCTTCTCCGAAATG |

| Myc/HA-mDDX1-Not I-R | TAAAGCGGCCGCTCAGAAGGTTCGGAACAGCTG |

Absolute quantitative real-time PCR.

The virus load was determined as viral genomic copies using absolute quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) as previously described (46). Briefly, DNA from cultured cells was extracted using a DNA isolation minikit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The levels of ISKNV and HSV-1 genomic copies were quantified according to the levels of viral major capsid protein (ISKNV-mcp and HSV-1-mcp) gene copies, which were determined using a standard curve. The gene-specific primers used are listed in Table 2. qPCR was performed using 2× TaqMan real PCR easy mix according to the following program: 95°C for 1 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 s.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for qPCR or RT-qPCR in this study

| Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|

| ISKNV MCP TaqMan probe | CAGGAGTTTAGTGTGACGGT |

| ISKNV-mcp-RT-F | CAATGTAGCACCCGCACTGACC |

| ISKNV-mcp-RT-R | ACCTCACGCTCCTCACTTGTC |

| ISKNV-orf008R-RT-F | TGACCTGTGGCCTAGATGATAAC |

| ISKNV-orf008R-RT-R | AGAGGCAGAGCAGCAGCATGTAGAGT |

| ISKNV-orf101L-RT-F | AAGCCGAGGACCCCAAGAAGT |

| ISKNV-orf101L-RT-R | GTCCTGACCGCCCACCAGTAT |

| DDX1-RT-F | GCCAGATGAGAAGCAGAACTATGT |

| DDX1-RT-R | TTCAGTCGGGTGTTGTAGCAG |

| TRPV4-RT-F | CAAGAATGAGACCTGCCAAACC |

| TRPV4-RT-R | TGCCTGTGCGTCAGCGACT |

| β-actin-RT-F | CCCTCTGAACCCCAAAGCCA |

| β-actin-RT-R | CAGCCTGGATGGCAACGTACA |

| mDDX1-RT-F | CTCCGAAATGGGTGTTATGCC |

| mDDX1-RT-R | ATGGGATAGATTCTGCCTGGAT |

| mTRPV4-RT-F | CGTCCAAACCTGCGAATGAAGTTC |

| mTRPV4-RT-R | CCTCCATCTCTTGTTGTCACTGG |

| mGAPDH-RT-F | AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG |

| mGAPDH-RT-R | TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA |

| HSV-1-icp0-RT-F | AAGCTTGGATCCGAGCCCCGCCC |

| HSV-1-icp0-RT-R | AAGCGGTGCATGCACGGGAAGGT |

| HSV-1-pol-RT-F | CAGCAGATCCGCGTCTTTAC |

| HSV-1-pol-RT-R | GCAGAATAAAGCCCTTCTGGT |

| HSV-1-gc-RT-F | TGTAACTTCGACCCGCAAC |

| HSV-1-gc-RT-R | CGAGACAGACCGCAGTACAC |

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

Total RNAs from cultured cells were isolated using a total RNA extraction kit (Promega, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA samples were reverse transcribed to cDNA using a PrimeScript reverse transcription (RT) reagent kit (TaKaRa, China). An RT-qPCR assay was conducted using a 10-μL reaction mixture system containing a mixture of 1 μL of the cDNA template, primers, double-distilled water (ddH2O), and 2× SYBR with a Roche LightCycler 480 thermal cycler. The reaction program was as follows: 50°C for 2 min and 95°C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s. The gene-specific primers used are listed in Table 2.

Determination of the virus titer.

To determine the ISKNV titer, the infection titration 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) was measured using a limiting dilution method. After 7 days, the virus-specific cytopathogenic effect was assessed microscopically, and the TCID50 value was calculated as described in a previous study (46).

Western blot analysis.

Transfected or infected cells were harvested at the indicated times, lysed, and used to determine the protein concentration with a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein quantification kit (Genesand, Beijing, China). Equal amounts of protein samples were separated via SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Protein expression was analyzed with the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. The protein expression levels of ISKNV were determined using anti-VP101L (an ISKNV viral structural protein) antibody (mAb2D8, from C. F. Dong). The expression level of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was determined to ensure equal protein sample loading by using anti-GAPDH (Abways, China). Finally, the images of protein bands were acquired using an Amersham Image 600 instrument with a High-sig ECL Western blotting substrate kit (Tanon, China).

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Cells in six-well plates were cotransfected with various plasmids. After 36 h, the transfected cells were collected and lysed for 30 min at 4°C in 500 μL cell lysis buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail at a ratio of 1:100. After the lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min, 100 μL of the supernatant was used for the quantification and adjustment of the protein concentration, and the remainder was used for coimmunoprecipitations (co-IPs) with the Pierce c-Myc tag magnetic IP/co-IP kit or the Pierce anti-HA magnetic IP/co-IP kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequently, the immunoprecipitated complexes were used for Western blot analysis.

RNA immunoprecipitation.

An RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assay was performed with an RIP kit (BersinBio, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, cells were lysed and divided into three parts corresponding to samples of the immunoprecipitate, IgG (as a control), and the input. Thereafter, the lysates were incubated with the required antibodies at 4°C with rotation overnight. Immunoprecipitated RNAs were isolated and reverse transcribed to cDNA. Finally, the interaction between RNA and protein was detected and analyzed by PCR and RT-qPCR.

Calcium imaging.

The calcium indicator dye Calbryte-590/AM (AAT Bioquest, USA) was used for calcium imaging experiments. Cells seeded into glass-bottom dishes were transfected, stained with Calbryte-590/AM for 1 h, and then washed three times with Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) buffer (Biosharp, China). The cells were transferred to the temperature-controlled stage of an inverted microscope for visualization. The emission intensity of Calbryte-590/AM excited at 555 nm was recorded using a Leica TCS SP8 stimulated emission depletion (STED) 3X instrument (Leica, Germany) for image acquisition and analysis. The cytosolic Ca2+ levels in cells were determined by the expression of the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f (47), which was excited at 488 nm, and the emission was collected at 525 nm.

Small interfering RNA assay.

The target sequence of small interfering RNA (siRNA) for Mus musculus DDX1 (5′-GCTGTGGAGGAGATGGATT-3′) was obtained from the literature (48) and chemically synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology (Beijing, China). The knockdown of endogenous DDX1 in BHK-21 cells was conducted by transfection with DDX1 siRNA. Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A negative-control RNA (siNC) was used as a negative control.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism. Data were normalized and are represented as means ± standard deviations (SD). All experiments in this article were conducted in triplicate (unless otherwise stated). Significance between groups was evaluated by using two-tailed/unpaired Student’s t test. P values of <0.05 (indicated by * in the figures) and <0.01 (indicated by **) were considered significant and extremely significant differences, respectively; ns represents a nonsignificant value.

Data availability.

We confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplemental material.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (no. 2022YFE0203900), the Guangdong Key Research and Development Program (no. 2022B1111030001 and 2021B0202040002), the Guangdong Laboratory for Lingnan Modern Agriculture (no. NZ2021018), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (no. 2021A1515010647), the China Agriculture Research System (no. CARS-46), the Innovation Group Project of the Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai) (no. 311021006), and the Guangdong Provincial Special Fund for Modern Agriculture Industry Technology Innovation Teams (no. 2022KJ143).

We also thank Yiping Li for the HSV-1 strain, C. F. Dong for the ISKNV-VP101L monoclonal antibody (mAb2D8), and Jin Lu for BHK-21 cells.

C.G. conceived the study. Z.L. and Z.Z. performed the experiments. S.W. provided fish and ISKNV samples. X.Q., W.P., M.L., and C.L. performed data and laboratory analyses. Z.L. and C.G. wrote the article. C.G. and J.H. conceived the study and provided funding acquisition. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jianguo He, Email: lsshjg@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Changjun Guo, Email: gchangj@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Lori Frappier, University of Toronto.

REFERENCES

- 1.Voets T, Talavera K, Owsianik G, Nilius B. 2005. Sensing with TRP channels. Nat Chem Biol 1:85–92. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0705-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strotmann R, Harteneck C, Nunnenmacher K, Schultz G, Plant TD. 2000. OTRPC4, a nonselective cation channel that confers sensitivity to extracellular osmolarity. Nat Cell Biol 2:695–702. doi: 10.1038/35036318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galindo-Villegas J, Montalban-Arques A, Liarte S, de Oliveira S, Pardo-Pastor C, Rubio-Moscardo F, Meseguer J, Valverde MA, Mulero V. 2016. TRPV4-mediated detection of hyposmotic stress by skin keratinocytes activates developmental immunity. J Immunol 196:738–749. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liedtke W, Choe Y, Renom MAM, Bell AM, Denis CS, Sali A, Hudspeth AJ, Friedman JM, Heller S. 2000. Vanilloid receptor-related osmotically activated channel (VR-OAC), a candidate vertebrate osmoreceptor. Cell 103:525–535. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00143-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki M, Watanabe Y, Oyama Y, Mizuno A, Kusano E, Hirao A, Ookawara S. 2003. Localization of mechanosensitive channel TRPV4 in mouse skin. Neurosci Lett 353:189–192. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guler AD, Lee H, Iida T, Shimizu I, Tominaga M, Caterina M. 2002. Heat-evoked activation of the ion channel, TRPV4. J Neurosci 22:6408–6414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06408.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe H, Vriens J, Suh SH, Benham CD, Droogmans G, Nilius B. 2002. Heat-evoked activation of TRPV4 channels in a HEK293 cell expression system and in native mouse aorta endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 277:47044–47051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208277200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng Z, Paknejad N, Maksaev G, Sala-Rabanal M, Nichols CG, Hite RK, Yuan P. 2018. Cryo-EM and X-ray structures of TRPV4 reveal insight into ion permeation and gating mechanisms. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25:252–260. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donate-Macian P, Jungfleisch J, Perez-Vilaro G, Rubio-Moscardo F, Peralvarez-Marin A, Diez J, Valverde MA. 2018. The TRPV4 channel links calcium influx to DDX3X activity and viral infectivity. Nat Commun 9:2307. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04776-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rocak S, Linder P. 2004. DEAD-box proteins: the driving forces behind RNA metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5:232–241. doi: 10.1038/nrm1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu L, Khadijah S, Fang S, Wang L, Tay FPL, Liu DX. 2010. The cellular RNA helicase DDX1 interacts with coronavirus nonstructural protein 14 and enhances viral replication. J Virol 84:8571–8583. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00392-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edgcomb SP, Carmel AB, Naji S, Ambrus-Aikelin G, Reyes JR, Saphire AC, Gerace L, Williamson JR. 2012. DDX1 is an RNA-dependent ATPase involved in HIV-1 Rev function and virus replication. J Mol Biol 415:61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamichhane R, Hammond JA, Pauszek RF, III, Anderson RM, Pedron I, van der Schans E, Williamson JR, Millar DP. 2017. A DEAD-box protein acts through RNA to promote HIV-1 Rev-RRE assembly. Nucleic Acids Res 45:4632–4641. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y, Wu W, Xie L, Wang D, Ke Q, Hou Z, Wu X, Fang Y, Chen H, Xiao S, Fang L. 2017. Cellular RNA helicase DDX1 is involved in transmissible gastroenteritis virus nsp14-induced interferon-beta production. Front Immunol 8:940. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xue Q, Liu H, Zeng Q, Zheng H, Xue Q, Cai X. 2019. The DEAD-box RNA helicase DDX1 interacts with the viral protein 3D and inhibits foot-and-mouth disease virus replication. Virol Sin 34:610–617. doi: 10.1007/s12250-019-00148-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Z, Wang J, Zhu W, Yu X, Wang Z, Ma J, Wang H, Yan Y, Sun J, Cheng Y. 2021. Chicken DDX1 acts as an RNA sensor to mediate IFN-β signaling pathway activation in antiviral innate immunity. Front Immunol 12:742074. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.742074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2022. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cascarano MC, Stavrakidis-Zachou O, Mladineo I, Thompson KD, Papandroulakis N, Katharios P. 2021. Mediterranean aquaculture in a changing climate: temperature effects on pathogens and diseases of three farmed fish species. Pathogens 10:1205. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10091205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang YQ, Lu L, Weng SP, Huang JN, Chan S-M, He JG. 2007. Molecular epidemiology and phylogenetic analysis of a marine fish infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus-like (ISKNV-like) virus. Arch Virol 152:763–773. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0870-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He JG, Wang SP, Zeng K, Huang ZJ, Chan S-M. 2000. Systemic disease caused by an iridovirus-like agent in cultured mandarinfish, Siniperca chuatsi (Basilewsky), in China. J Fish Dis 23:219–222. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2761.2000.00213.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan H, Chen XY, Zhang F, Chen J, Chu F, Sellers ZM, Xu F, Dong H. 2022. Capsaicin inhibits intestinal Cl− secretion and promotes Na+ absorption by blocking TRPV4 channels in healthy and colitic mice. J Biol Chem 298:101847. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voets T, Prenen J, Vriens J, Watanabe H, Janssens A, Wissenbach U, Bodding M, Droogmans G, Nilius B. 2002. Molecular determinants of permeation through the cation channel TRPV4. J Biol Chem 277:33704–33710. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204828200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang J, Wei Y, Bai S, Ding S, Gao H, Yin S, Chen S, Lu J, Wang H, Shen Y, Shen B, Du J. 2019. TRPV4 complexes with the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and IP3 receptor 1 to regulate local intracellular calcium and tracheal tension in mice. Front Physiol 10:1471. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.01471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phuong TTT, Redmon SN, Yarishkin O, Winter JM, Li DY, Krizaj D. 2017. Calcium influx through TRPV4 channels modulates the adherens contacts between retinal microvascular endothelial cells. J Physiol 595:6869–6885. doi: 10.1113/JP275052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Y, Frey TK, Yang JJ. 2009. Viral calciomics: interplays between Ca2+ and virus. Cell Calcium 46:1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hyser JM, Collinson-Pautz MR, Utama B, Estes MK. 2010. Rotavirus disrupts calcium homeostasis by NSP4 viroporin activity. mBio 1:e00265-10. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00265-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strtak AC, Perry JL, Sharp MN, Chang-Graham AL, Farkas T, Hyser JM. 2019. Recovirus NS1-2 has viroporin activity that induces aberrant cellular calcium signaling to facilitate virus replication. mSphere 4:e00506-19. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00506-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyser JM, Estes MK. 2015. Pathophysiological consequences of calcium-conducting viroporins. Annu Rev Virol 2:473–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-054846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dimitrov DS, Broder CC, Berger EA, Blumenthal R. 1993. Calcium ions are required for cell fusion mediated by the CD4-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein interaction. J Virol 67:1647–1652. doi: 10.1128/JVI.67.3.1647-1652.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burmeister WP, Cusack S, Ruigrok RWH. 1994. Calcium is needed for the thermostability of influenza B virus neuraminidase. J Gen Virol 75:381–388. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-2-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fujioka Y, Tsuda M, Nanbo A, Hattori T, Sasaki J, Sasaki T, Miyazaki T, Ohba Y. 2013. A Ca2+-dependent signalling circuit regulates influenza A virus internalization and infection. Nat Commun 4:2763. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hardie RC. 2005. Inhibition of phospholipase C activity in Drosophila photoreceptors by 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) and di-bromo BAPTA. Cell Calcium 8:547–556. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arniges M, Fernandez-Fernandez JM, Albrecht N, Schaefer M, Valverde MA. 2006. Human TRPV4 channel splice variants revealed a key role of ankyrin domains in multimerization and trafficking. J Biol Chem 281:1580–1586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511456200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wegierski T, Hill K, Schaefer M, Walz G. 2006. The HECT ubiquitin ligase AIP4 regulates the cell surface expression of select TRP channels. EMBO J 25:5659–5669. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strotmann R, Schultz G, Plant TD. 2003. Ca2+-dependent potentiation of the nonselective cation channel TRPV4 is mediated by a C-terminal calmodulin binding site. J Biol Chem 278:26541–26549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302590200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia-Elias A, Lorenzo IM, Vicente R, Valverde MA. 2008. IP3 receptor binds to and sensitizes TRPV4 channel to osmotic stimuli via a calmodulin-binding site. J Biol Chem 283:31284–31288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Graaf SF, Hoenderop JG, van der Kemp AW, Gisler SM, Bindels RJ. 2006. Interaction of the epithelial Ca2+ channels TRPV5 and TRPV6 with the intestine- and kidney-enriched PDZ protein NHERF4. Pflugers Arch 452:407–417. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0051-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fuller-Pace FV. 2006. DExD/H box RNA helicases: multifunctional proteins with important roles in transcriptional regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 34:4206–4215. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang P, Li S-S, Xu X-F, Yang C, Cheng C, Wang J-S, Zhou P-Z, Liu S-W. 2023. TRPV4 channel is involved in HSV-2 infection in human vaginal epithelial cells through triggering Ca2+ oscillation. Acta Pharmacol Sin 44:811–821. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00975-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bai H, Si L, Jiang A, Belgur C, Zhai Y, Plebani R, Oh CY, Rodas M, Patil A, Nurani A, Gilpin SE, Powers RK, Goyal G, Prantil-Baun R, Ingber DE. 2022. Mechanical control of innate immune responses against viral infection revealed in a human lung alveolus chip. Nat Commun 13:1928. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29562-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuebler WM, Jordt S, Liedtke WB. 2020. Urgent reconsideration of lung edema as a preventable outcome in COVID-19: inhibition of TRPV4 represents a promising and feasible approach. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 318:L1239–L1243. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00161.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donate-Macian P, Duarte Y, Rubio-Moscardo F, Perez-Vilaro G, Canan J, Diez J, Gonzalez-Nilo F, Valverde MA. 2022. Structural determinants of TRPV4 inhibition and identification of new antagonists with antiviral activity. Br J Pharmacol 179:3576–3591. doi: 10.1111/bph.15267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong C, Weng S, Shi X, Xu X, Shi N, He J. 2008. Development of a mandarin fish Siniperca chuatsi fry cell line suitable for the study of infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV). Virus Res 135:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He J, Mi S, Qin X-W, Weng S-P, Guo C-J, He J-G. 2019. Tiger frog virus ORF104R interacts with cellular VDAC2 to inhibit cell apoptosis. Fish Shellfish Immunol 92:889–896. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He JG, Deng M, Weng SP, Li Z, Zhou SY, Long QX, Wang XZ, Chan S-M. 2001. Complete genome analysis of the mandarin fish infectious spleen and kidney necrosis iridovirus. Virology 291:126–139. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zeng R, Pan W, Lin Y, He J, Luo Z, Li Z, Weng S, He J, Guo C. 2021. Development of a gene-deleted live attenuated candidate vaccine against fish virus (ISKNV) with low pathogenicity and high protection. iScience 24:102750. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen T-W, Wardill TJ, Sun Y, Pulver SR, Renninger SL, Baohan A, Schreiter ER, Kerr RA, Orger MB, Jayaraman V, Looger LL, Svoboda K, Kim DS. 2013. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 499:295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanaka K, Okamoto S, Ishikawa Y, Tamura H, Hara T. 2009. DDX1 is required for testicular tumorigenesis, partially through the transcriptional activation of 12p stem cell genes. Oncogene 28:2142–2151. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplemental material.