Abstract

There are 5.8 million Americans with Alzheimer’s disease and this number is rising. Social Work can play a key role. Yet, like other disciplines, the field is ill prepared for the growing number of individuals and family members who are impacted physically, emotionally and financially. Compounding the challenge, the number of social work students identifying interest in the field is low. This mixed methods concurrent study assessed the preliminary efficacy of a day-long education event among social work students from eight social work programs. Pre- post-training survey included: 1) dementia knowledge, assessed with the Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale, and 2) negative attitudes towards dementia, assessed by asking students to identify three words that reflected their thoughts on dementia, which were later rated as positive, negative or neutral by three external raters. Bivariate analyses showed that dementia knowledge (mean difference= 9.9) and attitudes (10% lower) improved from pre- to post-training (p<0.05). Collaboration between social work programs can increase student access to strength-based dementia education. Such programs hold the potential of improving dementia capability within the field of Social Work.

Introduction

As of 2020, nearly half of the 76 million baby boomers will be 65 or over (Gurwitz & Pearson, 2019). There are 5.8 million Americans with Alzheimer’s disease and this number is expected to increase to 14 million by 2050 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). America is not only aging, but Alzheimer’s and related dementias (ADRD) are changing the construct of identified and emerging needs within that population. Social Workers are uniquely positioned to lead efforts in addressing these needs.

Those who have ADRD and their more than 16 million family caregivers range in age, gender, ethnicity, geographic and economic status. ADRD, however, can disproportionately impact underserved and vulnerable populations. ADRD is present in virtually all social work practice settings, thus necessitating a fundamental knowledge base. While most individuals with ADRD are over the age of 65, up to 5% of those diagnosed are under 65, bringing a range of specific issues such as workplace rights and impact on childcare (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Individuals who are African American are twice as likely to develop ADRD, Latinx are 1.5 times more likely (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Cardiovascular status presents ADRD risk factors such as high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol – all of which have higher prevalence in individuals with lower economic status and those with persistent mental health issues (Al-Turk et al., 2018; Kilbourne et al., 2017). Individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) are also at a significantly higher risk for ADRD (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). Some studies indicate there may be more disease vulnerability in those that have sustained early life trauma, such as abuse and neglect (Hoeijmakers et al., 2018; Radford et al., 2017). Head injury is a risk factor for ADRD with studies showing that as many as 91% of survivors of domestic violence are hit in the head and 58% experiencing traumatic brain injury (Reisher et al., 2019). Additionally, there are significant disparities in access to support services. Financial limitations, geographic barriers and lack of ADRD capable services create inequities in diagnostic evaluation, home supports and care management (Epps et al., 2018; Manthorpe et al., 2018). Unprepared social workers add to this disparity by missing early signs of cognitive changes, failing to advocate appropriately and implementing interventions that do not match need.

Fundamental in social work practice is the relationship. Theoretical approaches to human behavior provide a foundation which is supplemented with understanding the specific cultural, environmental, systemic and individual contributors that direct the nature of the work. These essential skills are reflected in the core competencies for social work education identified by the Council of Social Work Education (CSWE, 2015). For someone with an ADRD and the families that support them, often it is the assessment piece where central omissions occur (Isaacson and Saif, 2020). As with other diseases of the brain, knowledge of what is happening in the brain, what areas are affected, specific anticipated trajectory and translation of that objective information to the person who brings a set of supports, resources, coping strategies and values is where meaningful work is found. In other words, it is required for competent practice (CSWE, 2015). Engagement simply does not happen in any meaningful way without that context. Intervention can look like a defined menu of services disconnected to true need without a skill set born from that deeper understanding of those diseases and the individual manifestation (CSWE, Sage – SW, 2006).

Despite the vast needs presented by ADRD, embedded social work curriculum to advance student understanding and ability to address those needs is limited (Tan et al., 2017). The presence, amount and content of ADRD education in social work programs are related to a variety of logistic and attitudinal issues. While ADRD specific curriculum in social work programs has not been well studied, it is logical that such curriculum would most commonly be found in aging courses. Shortages in gerontological social work faculty contribute to a reduced presence of aging focused coursework (Berkman et al., 2016). A circular component exists as there are less teaching assistantships and financial support for aging focused doctoral students, a primary pipeline for faculty (Mellor & Ivry, 2013). Studies looking at social work textbooks indicate that only 2% of the content address the aging population and aging specific issues. No studies were found that address specific content around ADRD (Ball, 2018). Universities are disinclined to offer aging courses due to low student interest and resulting impact on competitive decision making for limited resources. Integration of information about ADRD in general practice, policy, and integrated health courses is dependent on individual instructors with unclear frequency, amount and content.

Stigma, or “the assignment of negative worth on the basis of a devalued group or individual character” plays a prominent role in the world of older adults in general and even more so with those who face ADRD (Dobbs et al., 2008; Harper et al., 2019). Stigma, in this case, can also be referred to as ageism. Studies connect a reduced sense of well-being, diminished self-worth and lower quality of life to the presence of stigma (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2012). ADRD are often unilaterally attached to incompetence, loss and burden rather an integration of loss into the larger aspects of life. While the majority of individuals experiencing ADRD reside in the community, there is a false believe that the majority are found in skilling nursing facilities (Alzheimer’s Association, 2020). While valuable initiatives within long term care settings have expanded strength-based care options, systemic flaws in the long term care industry continue to limit consistent presence and therapeutic implementation of these initiatives. National initiatives for addressing needs of individuals in earlier stages are few and tend to exist only in urban areas. In the State of Kansas, for example, there are 4 support groups for those with Mild Cognitive Impairment or early stage ADRD, all located in urban areas.

Unfortunately, stigma exists in the health care provider community contributing to delayed detection of cognitive changes (Dubois et al., 2016). Delayed diagnosis and poor ADRD management can result in earlier institutionalization, inappropriate treatment for agitation and under recognition of both depression and elder abuse (Vicary et al., 2006). Diminished relationships, exclusion from conversations or events and being given recommendations that do not fit current needs are other frequently experienced examples of stigma. These are more likely to occur when helping professionals do not have enough information and understanding of ADRD are involved.

Stigma also impacts student interest in the field. Only 3% of social work students identify an aging focus (Scharlach et al., 2000; Wang & Chonody, 2013). In one study of 172 MSW and BSW students, only 30% of the students strongly disagreed with the statement “All elders are memory impaired” (Kane, 2006). Ageist attitudes, significance of interaction with older adults and lack of knowledge are primary contributors to student low interest (Ball, 2018). A part of this stigma is the perception that social work practice with individuals with ADRD and their families is confined to referral to resources - primarily those focused on direct assistance in the home or placement into long term care or excessive paperwork- rather than the spectrum of emotional, educational, logistical and relational needs that present as they would with any other population.

Students often do not realize the variety of practice areas impacted by ADRD. The reality is that ADRD are present in virtually all areas of social work practice, such as mental health settings, substance abuse services, child protective services, homeless shelters, domestic violence programs, community police departments, veteran services, clinics settings, emergency assistance agencies and employee assistance programs. Some settings, such as prisons, acknowledge an ever-growing population of individuals with ADRD but do not have the structure to manage these needs (Peacock et al., 2019; Vogel, 2016). In other settings, there are significant gaps in prevalence data and in understanding of the role of ADRD as seen through narratives from social workers in the field.

To understand more about this experience across practice settings, the social work departments participating in the Dementia Intensive, the education event this study describes, extended an open request for their social work alumni and others to share the nature of a presence of ADRD within their work. Suggested questions to address included: 1) Did you anticipate that individuals with ADRD would be among those you work with in your position? 2) Are there trends or specific circumstances in which you might see someone with ADRD? 3) Provide an example of a time ADRD played a role in your work and 4) Discuss impact of your ADRD knowledge or knowledge gaps on your work with individuals with ADRD. The following excerpts are from narratives received from that exploration, each highlighting the need for ADRD knowledge across practice areas.

“I work as the Mental Health Co-Responder for the Police Department. I assist on-scene officers with individuals who are going through a behavioral health crisis. Before working as a Co-Responder, I did not have, quite frankly, any experience working with dementia. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I knew it might be a possibility I would encounter individuals with dementia living in our city, but I didn’t realize how prevalent it would be.”

Behavioral Health Social Worker, M.S.W.

“I work as a substance use disorder counselor/case manager. We provide supportive housing for people living with severe mental illness who are or have been chronically homeless. Most have a co-occurring substance use disorder. I anticipated that dealing with dementia would be part of this work, due to the impact of substance use on the aging brain and the fact dementia is more prevalent in people living with severe mental illness. What I had not anticipated was how prevalent it would be, how early it would be, and how difficult dementia would make other aspects of already impaired functioning. What would have helped me in the above case was what questions to ask this client’s providers. I knew none of these questions, nor did this person’s on-site housing case manager. Further, his medical doctor didn’t ask him or us any of the relevant questions nor engage in what kinds of things a doctor would look for.”

Substance Abuse Counselor, M.S.W.

“I am a clinical social worker in pediatric hematology and oncology at a local children’s hospital. I provide therapeutic support and case management services for children and teens with cancer and their families. Since I work with children/teens and their parents/caregivers, I did not anticipate working with many persons with dementia. There are times that the children I work with are cared for primarily by grandparents or older family members. In these cases, there is always a possibility that dementia could be affecting caregivers of patients I see. Currently, I have a 17-year-old patient (will call him David) who has a cancer diagnosis. He lives with his mother, who is a single parent with limited income, limited resources, and limited psychosocial support. A few months after David’s diagnosis, his maternal grandmother had to move in with the family due to health concerns of her own. She has since been diagnosed with dementia. David’s mother is now not only responsible for providing care for David through his cancer treatment, but also has to manage her mother’s needs. His grandmother cannot be left alone and requires 24-hour supervision and care. This has caused a significant increase in stress within the family dynamic and household. It would be helpful for me to know more about specific resources that could help my patient’s mother obtain respite care and other supports.”

Pediatric Medical Social Worker, M.S.W.

“When starting to work with prisoners 10 year ago I knew that dementia was going to be a concern, especially as the baby boomer generation is approachingthat time of life. Prisons are having to deal with inmates having dementia resulting in an ever-increasing need for changes to interventions. I presently have one inmate who is showing early signs of his dementia as evidenced by his confusion. He looksfor the words as he speaks, trying to inform others of his wants, and he regularly asks where he is supposed to go in the cell house. The discharge planning department is trying to find a structured environment for him upon his release, but an inmate with a felony history is a difficult placement.”

Correctional Social Worker, M.S.W

“I work as a Senior Strategic Planning Consultant. I work with various departments in our health system to assess how we can best serve the patients in our market, while remaining a financially sustainable institution. Even though I no longer work at the bedside with individual patients and families, the work I do directly affects the services these patients receive. Even today, I’m working on a project to ensure that patients with Alzheimer’s, across the state of Kansas, have access to the memory care services they need.”

Healthcare Administrator, B.S.W, M.S.W.

“I provide in home family therapy for at risk families and children at risk for being removed and placed in foster care. These families are at risk due to hotlinecalls to DCF due to abuse and neglect. Honestly, I didn’t think I would ever run into anyone with a dementia while working in children’s mental health services. But I do. I was working with a sibling group living with their grandmother after being removed from their mother. The grandmother began to forget the dates of the mental health appointments specifically medication services. Once an appointment is missed, it becomes difficult to obtain another appointment quickly. The missed appointments created issues for the children to function in the classroom setting due to lack of medication. In addition, the grandmother was not supervising the children appropriately and their hygiene became an issue. The case manager began to notice the grandmother having difficulties and began to staff the concerns in supervision. We sent an email to the medication provider who shared the sameconcerns. Due to the concerns, we had to hotline the concerns to DCF. The children eventually had to be removed from the grandmother’s home. If the symptoms and behaviors could have been identified earlier, it would have decreased the children struggling academically. The oldest child became somewhat parentified due to the grandmother struggling to care for the children.”

Child Welfare Worker, M.S.W.

“I was tasked to expand the existing day program to meet the increasing number of individuals with an IDD who were aging, many of whom had a diagnosis of dementia. Before taking on that position I had never thought of dementia or had much experience with it. It seems silly but in a span of a year it consumed me and I was constantly thinking of dementia supports and how we, as a provider, could meet the increasing number of those who would likely need them. It changed my focus on providing supports to individuals for them to become more independent and forward thinking to understanding a new role where the focus was more on where they are now and helping them maintain.”

Disabilities Social Worker, M.S.W.

Education and exposure to individuals with ADRD are key elements in changing ageist and inaccurate views (Ball, 2018; Chonody, 2018).

This manuscript’s aim is to assess the preliminary efficacy of the Dementia Intensive Program. This manuscript also aims to explore the acceptability of the Dementia Intensive Program and discuss its value by considering both its preliminary efficacy and acceptability. The Dementia Intensive Program objectives were to 1) increase ADRD knowledge among social work students, 2) reduce ageist beliefs among students, 3) increase student interest in working with individuals and families impacted by ADRD and 4) provide a feasible structure for ADRD education for social work programs across the region. We hypothesized that participating in the Dementia Intensive training would increase participants’ ADRD knowledge and reduce negative attitudes.

Methods

Overview

This was a mixed-methods concurrent study, in which quantitative and qualitative data were collected at the same time. The quantitative method dominates, while the qualitative method is nested within. The quantitative method included a pre-post trial design, whereas the qualitative method included a qualitative descriptive approach. The Dementia Intensive was a day-long educational event jointly funded by the Administration of Community Living and a private donor. The Dementia Intensive was a collaboration of eight social work programs in the region led by the KU Alzheimer’s Disease Center, one of 31 NIH-designated Alzheimer’s Research Centers. The day included the following topic areas:

1) Disease Overview 2) Social Work Assessment with focus on key areas of need in ADRD such as varying presentation of depression 3) Elements of a Dementia Adapted Empowerment Model 4) Experience Panel – Individuals diagnosed with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or Early Stage ADRD 5) Experience Panel – Care Partners of individuals with ADRD 6) Current state of ADRD research. The panel of those diagnosed included four individuals who shared their journey from recognizing symptoms, diagnostic process, what they expect from professionals, how they adapt and cope and how they find purpose. There were five people on the care partner panel, including spouses, adult children and a teenager whose father began showing symptoms in his late 40’s. The speakers on the caregiver panel exposed the students to the reality of younger onset ADRD. The panel discussed where professionals have helped and failed to help them, the complexity of grief and their own search for acceptance and meaning. The audience was then invited to ask the panelists questions. The topic areas were selected to provide general ADRD education, to provide a framework for social work practice and to provide the direct exposure to individuals impacted by MCI or early ADRD that studies have indicated align with increased interest in the field and reduced ageist attitudes.

While other diseases have long subscribed to an empowerment-based model, that has been absent in work with individuals and families with ADRD. The KU Alzheimer’s Disease Center has adapted these empowerment principles to their work with individuals with a ADRD and their families. The Dementia Adapted Empowerment Model is in concert with strength based social work philosophy. It incorporates existing healthcare empowerment components including knowledge/health literacy, shared decision making, personal control and positive patient-provider interaction based on the stage of ADRD and can serve as a guide to ADRD capable practice (Polesce, 2018).

Each of the eight social work programs promoted the event to their own students. All the social work programs had student representation at the event. Two of the schools also had faculty representation. The KU Alzheimer’s Disease Center opened participation to area social workers and other related professionals as space allowed.

Partner Collaboration

All nine social work programs in the region were contacted to explore need and interest in ADRD specific collaborative education. Eight agreed to participate. Participation included collaborating to identify key topic areas, assistance with framing logistics and promoting the event with students. Participating schools also alerted field instructors of the event to increase approval of attendance should it conflict with practicum schedules. Most field instructors supported attendance counting as a part of required practicum hours. Conversations between partners took place through conference calls and email exchange.

Voices from the Field Exhibit.

The “Voices from the Field” exhibit highlighted artistically displayed letters from various social workers across multiple settings sharing their perspectives about ADRD, how ADRD appear in their work and how ADRD knowledge, or lack of, impacted the quality of their work with their clients. Excerpts from some of those letters are reflected in the narrative passages above. Participants were able to view the exhibit as they arrived, at breaks and during the lunch hour.

Data Collection and Measures

Pre-training survey socio-demographic information included age, gender, race, ethnicity, occupation, their veteran status and the three first digits of their zip codes. We identified the location corresponding to the zip code information and determined whether those locations were predominantly rural or urban based US Census criteria (Ratcliffe, 2016).

Preliminary efficacy outcomes included ADRD knowledge and attitudes measured via the following survey instruments: 1) ADRD knowledge: The Dementia Knowledge Assessment Scale (DKAS; Annear et al., 2015), a validated 27-item scale was used to measure ADRD knowledge. This scale includes statements addressed the themes of ADRD characteristics, symptoms and progression, diagnosis and assessment, treatment and prevention, and care. Response options include a 4‐point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree) with an auxiliary “I don’t know” option. Answers are scored as follows: 2= “true” answer to a true statement or “false” answer to an untrue statement; 1= “probably true” answer to a true statement or “probably false” answer to an untrue statement; 0= “probably true or true” answer to an untrue statement, “probably false or false” answer to a true statement or a “don’t know” answer. We analyzed total (range 0 to 54) and individual item scores (range 0 to 2), with higher scores meaning higher ADRD knowledge. This scale showed an internal consistency of 0.89, no statistically significant change in three weeks (test-retest reliability), and a correlation of 0.56 with another ADRD knowledge scale (concurrent validity) in a professionally diverse sample in Australia (DKAS; Annear et al., 2015). In the current study, the DKAS had an internal consistency Alpha of 0.85, indicating a high level of reliability. 2) ADRD attitudes: Attitudes towards ADRD were assessed in two different ways. First, pre and post-training surveys included one Likert scale item developed by the research team that asked participants how likely they were to work with individuals with ADRD in their career. Response options ranged from 1 (definitely not) to 5 (definitely). Second, pre and post-training surveys included an open-ended question developed by the research team that asked participants to write three words they associate with ADRD. All words written by the participants were given to 3 raters, social work faculty who did not attend the Dementia Intensive. The raters were blinded to participant and timepoint and asked to rate each word as negative, neutral or positive. Discrepancies of affective valence were determined by majority. There were no instances where a word was assigned neutral, negative, and positive, meaning that a majority affective valence assignment was made for each word. Acceptability was assessed by asking an open-ended question to participants in the post-training survey about what they found most useful in the Dementia Intensive training.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted for the total sample, social work students and non-social work students. Means, standard deviations, percentages and frequencies were calculated for pre-training survey characteristics. Paired samples t-tests were conducted to assess the mean differences in total ADRD knowledge scores and participants’ likelihood to work with individuals with ADRD in their career. Dementia knowledge item scores for pre- and post-training were represented using error bars and compared using Wilcoxon tests. Differences in attitudes associated with ADRD were calculated using Chi Square tests. We used SPSS 20 to run quantitative analyses and used a significance of p<.05. To analyze acceptability, we coded qualitative answers and later defined acceptability domains that summarized different discourses (e.g. liking the training overall or a specific section of the training such as discussion panels with caregivers and persons with ADRD). We quantified the number of times each domain was mentioned.

Results

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Ninety-seven individuals RSVP’d and 89 individuals attended the training. A total of 68 participants completed the pre-training survey and 60 (88.2%) of those completed both pre- and post-training measures, 33 (48.5%) were social work students and 35 (51.5%) were not. Among those who were not social work students, 21 (60.0%) were social workers and the other 40.0% included other professions such as case managers, information and retrieval providers, first responders, clergy, advocates, community activists, psychologists and other professions. The average age of participants was 39.0 (SD 15.6), the age range was 20 to 76 and social work students were in average 17.8 years older than non-students. Most participants were women (86.8%) and non-Latino White (85.3%), although almost all races and ethnicities were represented, and racial and ethnic minorities were more common in the non-social work student group (22.9%). The percentage of non-social work students who lived in a rural area was 14.4 % and 8.6% were veterans. None of the social work students had these characteristics.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

| Sample characteristic | Total (n=68) | Social work students (n=33) | Non-students (n=35) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Age in years | 39.0 | 15.6 | 30.1 | 8.9 | 47.9 | 16.1 |

| % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| Women | 86.8% | 59 | 87.9% | 29 | 85.7% | 30 |

| Non-Latino White | 85.3% | 58 | 87.9% | 29 | 77.1% | 27 |

| Rural | 7.4% | 5 | 0.0% | 0 | 14.4% | 5 |

| Veteran status | 4.4% | 3 | 0.0% | 0 | 8.6% | 3 |

| Main profession | ||||||

| Social work student | 48.5% | 33 | 100.0% | 33 | - | |

| Social worker | 30.9% | 21 | - | 60.0% | 21 | |

| Other professions | 20.6% | 14 | - | 40.0% | 14 | |

Short-term efficacy of the Dementia Intensive Training on ADRD knowledge and attitudes

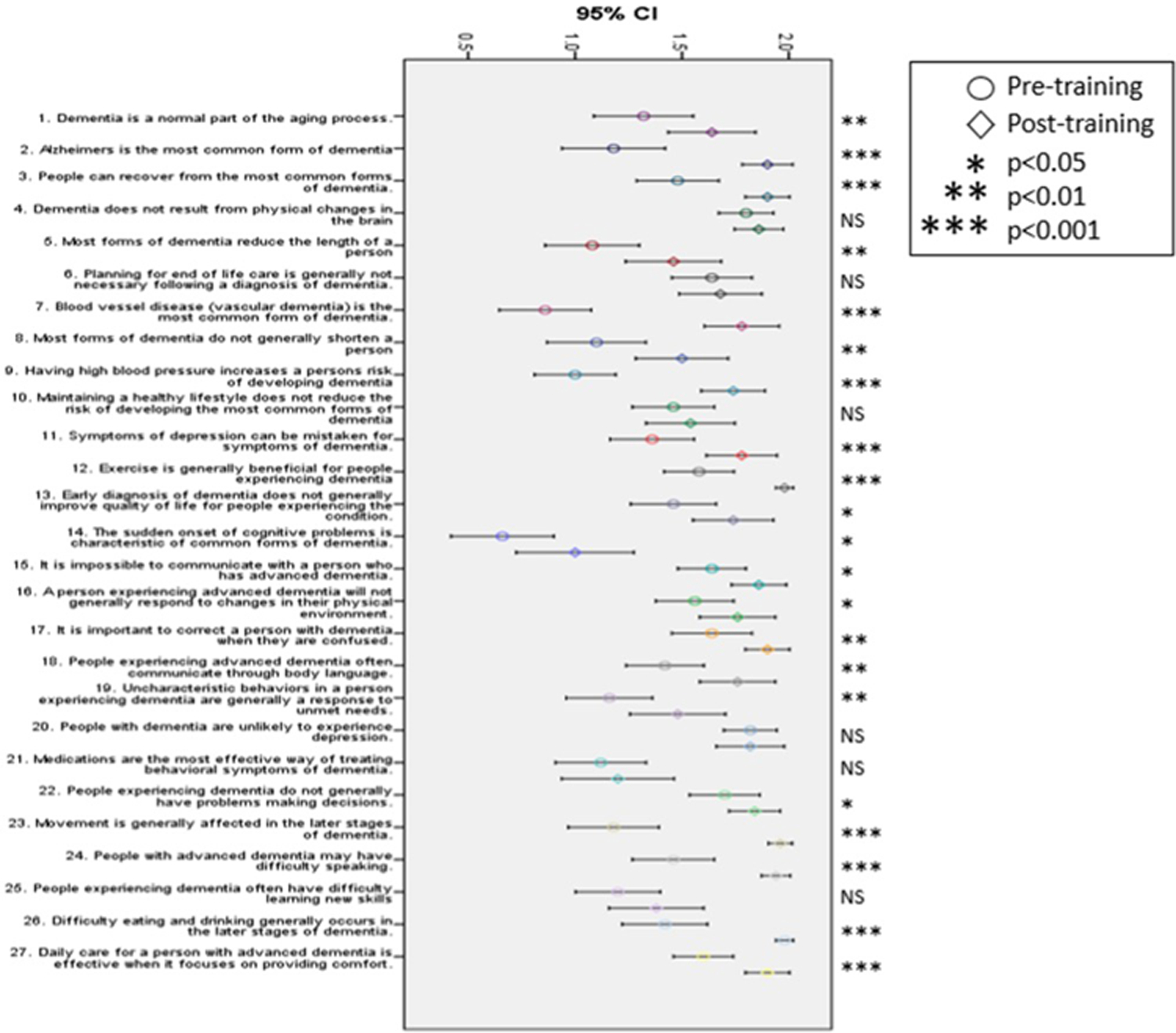

The mean ADRD knowledge score for the whole sample at the pre-training assessment was 36.2 (SD 8.4) and increased almost 10 points up to 46.1 (SD 5.3) at post-training (p < .001- Table 2). Estimates and p values remained similar among social work students and non-social work students. Figure 1 shows the average pre- and post-training ADRD knowledge scores for the 27 items of the DKAS (and standard error bars). Participants statistically significantly improved their answers to all questions except for six from pre- to post-training: ADRD does not result in physical changes in the brain, planning for end of life care is generally not necessary following a diagnosis of ADRD, maintaining healthy lifestyle does not reduce the risk of developing the most common forms of ADRD, people with ADRD are unlikely to experience depression, medications are the most effective way of treating behavioral symptoms of ADRD, people experiencing ADRD often have difficulty learning new skills. Participants’ likelihood to work with individuals with ADRD was 4 out of a 1 to 5 Likert scale (1 definitely not and 5 definitely) in their career did not change statistically in any group (P>0.05).

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Paired Samples T-Tests in Pre vs Post-Dementia Intensive Training on the Dementia Knowledge Total Score and Likelihood to Work with Dementia Patients in Their Social Work Career.

| Outcome | Pre-training | Post-training | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | p value (pre vs post-training) | |

| Total sample (n=54) | |||||

| Dementia knowledge (range 0–54) | 36.2 | 8.4 | 46.1 | 5.3 | <.001** |

| Likelihood to work with dementia patients (range 1–5) | 4.0 | 1.2 | 4.1 | 1.2 | 0.47 |

| Sample of social work students (n=24) | |||||

| Dementia knowledge (range 0–54) | 35.8 | 7.3 | 44.8 | 5.1 | <.001** |

| Likelihood to work with dementia patients (range 1–5) | 3.8 | 1.2 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 0.89 |

| Sample of non-students (n=30) | |||||

| Dementia knowledge (range 0–54) | 36.5 | 9.2 | 47.0 | 5.3 | <.001** |

| Likelihood to work with dementia patients (range 1–5) | 4.1 | 1.3 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 0.39 |

p<0.05;

p<0.001

Figure 1. Error Bars and Paired Samples Wilcoxon Tests in Pre vs Post Dementia Knowledge Item Scores.a.

a: 2= “true” answer to a true statement or “false” answer to an untrue statement. 1= “probably true” answer to a true statement or “probably false” answer to an untrue statement. 0= “probably true or true” answer to an untrue statement, “probably false or false” answer to a true statement or a “don’t know” answer.

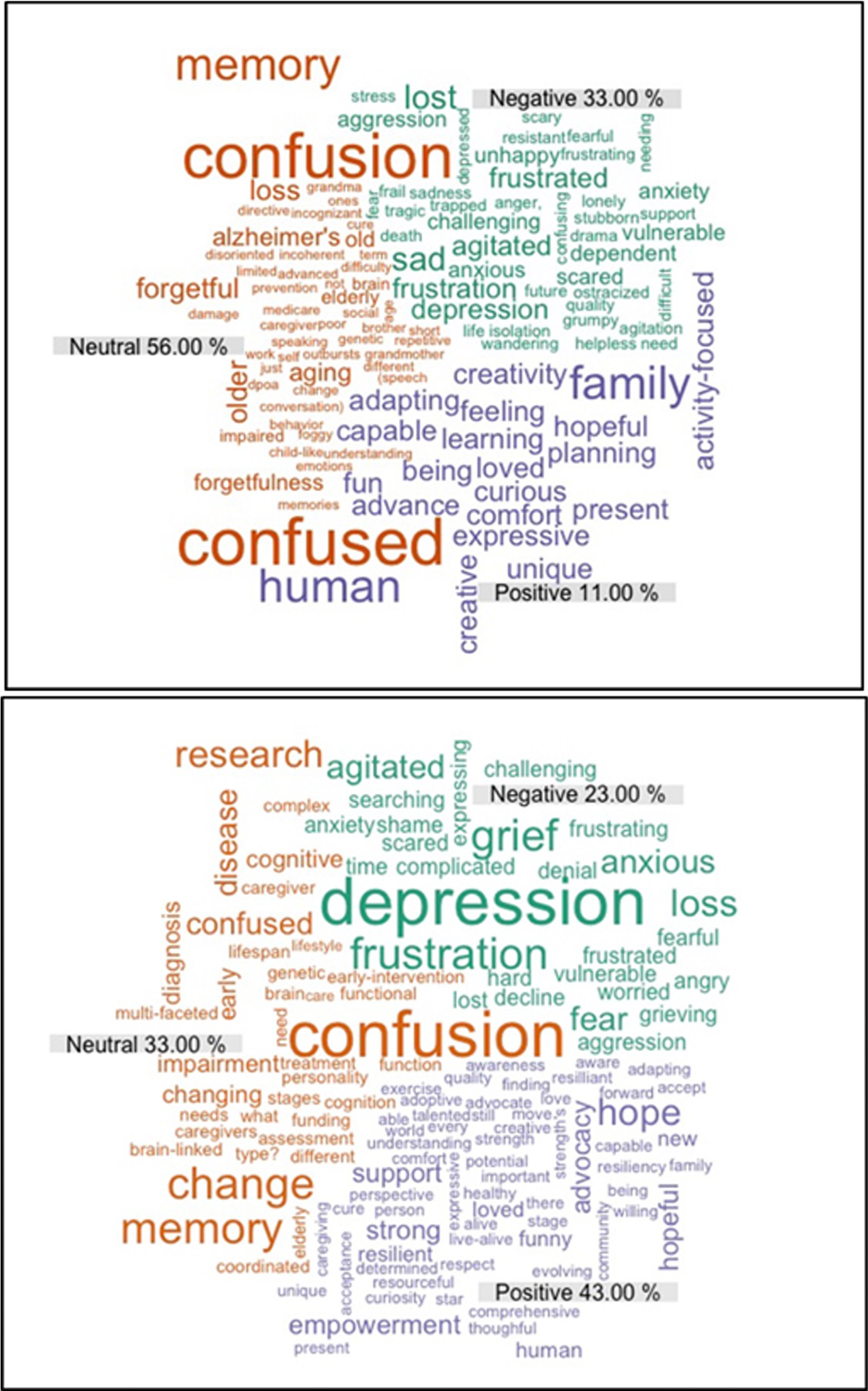

Analysis of words associated with ADRD showed that negative and neutral words decreased, while positive words increased from pre- to post-training in all groups (p<0.001). Figure two shows the short-term efficacy of the Dementia Intensive Training on the whole sample’s attitudes towards ADRD via a word cloud summarizing participants’ responses to “what three words do you most associate with the word dementia”. At pre-training, most words were generally defined as neutral (56.0%), including “confusion”, “aging”, “child-like”, “outbursts” or “incognizant”. The percentage of neutral words was declined at post-intervention (33.0%) and included more often words such as “research”, “personality”, “multi-faceted”, “early” or “diagnosis”. The percentage of negative words went down from 33.0% at pre-training to 23.0% at post-training. Common negative words at pre-training included “lost”, “frustration”, “agitation” and “aggression” along with words such as “stubborn”, “drama” and “grumpy”. The representation of words including “depression” and “grief” increased substantially from pre- to post-training, key areas covered in the curriculum. The percentage of positive words went up from 11.0% at pre-training to 43.0% at post-training. Words most common at pre-training included “human” and “family”, whereas “hope”, “advocacy” and “resilient” were more common at post-training. These results apply to both students and non-students separately as well.

Forty-nine participants responded to the acceptability question. Domains of acceptability include: general satisfaction with the training (n=11), satisfaction with the discussion panel (n=31), focus on assessment (n=6), focus on dementia signs, symptoms and types (n=9), focus on the client empowerment model (n=4), focus on medication and research (n=1), gaining of insight into the disease (n=8), positive presentation skills such as giving detailed examples (n=6), the opportunity to make connections (n=1) and need for a handout with slides so that participants can pay more attention to what is being said rather than writing information down.

Discussion

This manuscript’s aim was to assess the preliminary efficacy of the Dementia Intensive Program. The Dementia Intensive was a day-long event that aimed to 1) increase ADRD knowledge among social work students, 2) reduce ageist beliefs among students, 3) increase student interest in working with individuals and families impacted by ADRD and 4) provide a feasible structure for ADRD education for social work programs across the region. The Dementia Intensive increased ADRD knowledge and improved perceptions of ADRD among social work students and other groups. However, the Dementia Intensive did not change student likelihood to work with individuals and families impacted by ADRD. The satisfaction with the program as a whole and its different sections is evidence that the current Dementia Intensive format provides a feasible structure for ADRD education for social work programs across the region.

Information was presented in a variety of ways including lecture, discussion, the experience panels and the Voices from the Field exhibit. The Dementia Intensive provided direct exposure to individuals who have been diagnosed in early stage and able to share not only their stories but also a picture of resilience, a view that most of the students had not experienced. The care partners also added an honesty and depth to what social work support can offer them and the impact when it is absent. It is important that the curriculum included more than disease information, but also a specific guiding framework to support social workers in understanding their role in working with individuals and families. This framework could be separated and embedded in curriculum in a variety of formats to fit the needs of individual or collective social work programs. A virtual option could also expand access to students. The creation of a ADRD curriculum manual is being considered.

Integrating both education and confronting negative, often ageist, attitudes did meaningfully impact perspective. The three words measure indicated that attendees moved from thinking about ADRD from a passive and problematic frame to a fuller picture of the continuing person and the range of emotions and strengths that become central in social work interventions. In other words, it is important to not only understand the what, but also the why and how. This change in perspective is a primary extension of ADRD capability. Even for those who will never work in a practice setting primarily serving those with ADRD, to be able recognize and see value in addressing cognitive concerns in those that do cross their path is critical. The shifts seen in the three words measure was profound. It is unclear if the length of the event contributed to this positive result. It is possible the full day, larger audience format provided a momentum and energy that might not be sustained if in smaller doses separated by time. Such a comparison is worthy of future study. This intensive format may be applicable to other fields of practice such as intellectual and developmental disabilities.

It is also important that this was a collaboration of a number of social work programs, all of whom recognized the limited student education in this area, expressed a desire to do more and all of whom provided valuable input in the development of the event. In the eight social work programs participating in the Dementia Intensive, only half have a dedicated class to aging issues. None have more than one. All the participating programs expressed interest in repeating the Dementia Intensive in the future. The collaboration offered a feasible approach to increasing access to social work specific ADRD education.

The Dementia Intensive was not able to increase the student forecast of working with someone with a ADRD in their career. While this was not the desired result, it does not represent a sole indicator of potential reach. Given the wide range of possibilities within social work practice, many students struggle with identifying a specific population focus. Additionally, some students believe their primary interest is in one population and that evolves into others over the course of time. Finally, there are students who accept positions with populations other than their preferred population simply due to job availability. In these situations where the path to social work practice with individuals and families experiencing ADRD is meandered, advancing ADRD knowledge and improving strength-based attitudes become primary tools in improving their future service to ADRD clients.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations. We used a small non-probabilistic convenience sample and most participants were women, urban and non-Latino White, limiting external validity. The study sample only included individuals who decided to attend, potentially introducing selection bias leading to a sample with high baseline likelihood to work with people with ADRD. This self-selected sample might be a reason why student interest in working with individuals and families impacted by ADRD did not increase from pre- to post-training. It is possible that if the training had an expanded focus on working with older adults in general with ADRD as a part, participation from a broader audience may have been elicited. A comparison study could assist in understanding the specificity impact. The trial lacked a control group and randomization, thus preventing causality inference. The training did not include direct assessment in skills (e.g. role-playing communicating information to individuals with ADRD or conducting assessments). However, we believe direct, more interactive skills training would require more than a day-long session, which would reduce the feasibility of integrating this training into social work standard education. Also, knowledge and attitudes are needed prior to developing more advanced skills. Future studies should expand understanding of ADRD specific curriculum in social work programs through a larger sample of social work programs and data collected from faculty. This data could be used to advance an understanding of the connections between how and what we teach and the systemic impact on ADRD services.

Conclusion

The addition of ADRD specific curriculum in social work education is vital. There are not enough ADRD specialized social workers. There are not even enough social workers with sufficient ADRD practice knowledge, regardless of specialty. Limiting ADRD education to only disease education fails to close the loop to the translation of that knowledge into the social work role. Limiting in that way also fails to apply a strength-based framework that is the foundation of social work practice. The lack of ADRD prepared social workers, however, translates to more than just numbers. It is about lack of access to appropriate help. It is about a widely accepted hopelessness that doesn’t leave room for effective coping. It is about losing sight of both human complexity and the value that recognition adds as we walk with people down a path of losing and finding. We can and must do more.

Figure 2.

Frequency of Use of Negative, Positive and Neutral Attitude Words Towards Dementia in Pre- Vs Post- Dementia Intensive Training.

Acknowledgements:

The authors thank Linda Carson, The University of Kansas School of Social Welfare, The University of Central Missouri Department of Social Work, Kansas State University Department of Social Work, University of Missouri at Kansas City School of Social Work, Pittsburg State University Department of Social Work, Avila University Department of Social Work, Washburn University Department of Social Work and Wichita State University School of Social Work for their collaboration and support of this initiative.

Funding:

This work was supported, in part, by the Administration on Community Living [ACL - 90ALGG009 to M.N, A.Y., E.V. and K.B] and to a generous donation by the Carson family.

Biography

Michelle Niedens, LSCSW: KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology. Bio: Michelle Niedens, LSCSW, is director of the Cognitive Care Network, a community-based program focused on early detection, provider partnerships, and integration of interdisciplinary supports. Ms. Niedens’ background is in social work. Ms. Niedens’ special interests include assessment and intervention for associated neuropsychiatric challenges and advancing programs and services for individuals living with early-stage dementia.

Amy Yeager, LMSW: KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology. Bio: Amy Yeager is a social worker and lead community navigator with the Cognitive Care Network at the KU Alzheimer’s Disease Center. In addition to her direct work with individuals and families who are experiencing cognitive changes, her career focus has included a specialization in the dual diagnosis of and intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDD) and a dementia.

Eric D. Vidoni, PT, PhD: KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology. Bio: KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology. Bio: Eric Vidoni is a physical therapist and an associate professor in the Department of Neurology at the University of Kansas Medical Center. He leads the Outreach, Recruitment and Engagement Core of the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center which is tasked with increasing community engagement in dementia research. His research focus is using brain imaging and other techniques to quantify change in brain health as we age or develop Alzheimer’s disease.

Kelli Barton, PhD: UMKC Institute for Human Development. Kelli Barton is the Director of Health and Aging at the University of Missouri—Kansas City Institute for Human Development. Dr. Barton is a gerontologist with an interest in aging with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and expertise in conducting community-based research and policy and program evaluation.

Jaime Perales-Puchalt, PhD, MPH : KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology. Bio: Jaime Perales Puchalt, Ph.D., MPH, is an Assistant Professor at the University of Kansas Alzheimer’s Disease Center. His background is in psychology and public health. In addition to conducting research in Spain, England and the United States, Perales Puchalt has collaborated with teams from other countries in the European Union and the Americas. With a primary focus on reducing Latino dementia disparities, his research has led to the development of a dementia educational/recruitment tool for Latinos. He has also studied the risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment among sexual and ethnoracial minorities.

Rhonda Peterson Dealey, DSW, LSCSW: Washburn University, Department of Social Work. is an assistant professor of social work and the Master of Social Work Program Director at Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. She has been a licensed clinical social work practitioner for more than 25 years, working with individuals and families across the lifespan in the arenas of child welfare, health care, and school social work. Dr. Dealey earned a BA in social work and psychology from Bethany College, Lindsborg, KS, a Master of Social Work degree from University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and a Doctor of Social Work degree from Aurora University, Aurora, IL.

Dory Quinn, EdD, MSW: Pittsburg State University, Department of History, Philosophy & Social Sciences. Dory Quinn, EdD, MSW is an Assistant Professor of social work at Pittsburg State University. Her teaching emphasis is human behavior and professional skills development. She holds a doctorate degree in educational leadership and policy analysis and a master’s degree in social work. Her research interests include first-generation college students, social work education, and afterschool programs for low-income youth and families.

L. Ashley Gage, Ph.D., MSW: University of Central Missouri, Department of Social Work. Dr. Ashley Gage, Assistant Professor of Social Work, teaches Social Work Methods of Inquiry and Evaluation for Social Workers, Social Work Practice: Interventions with Communities and Organizations, Social Policy and Economic Justice, and other courses across the curriculum. Her research interests focus on medical social work, with emphasis on end of life. Dr. Gage is currently conducting research evaluating the use of Mental Health First Aid.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest

Contributor Information

Michelle Niedens, KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology.

Amy Yeager, KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology..

Eric D. Vidoni, KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology..

Kelli Barton, UMKC Institute for Human Development..

Jaime Perales-Puchalt, KU Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Department of Neurology..

Rhonda Peterson Dealey, Washburn University, Department of Social Work.

Dory Quinn, Pittsburg State University, Department of History, Philosophy & Social Sciences..

L. Ashley Gage, University of Central Missouri, Department of Social Work..

Data availability statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

- Al-Turk B, Harris C, & Nelson G (2018). Poverty, a risk factor overlooked: a cross-sectional cohort study comparing poverty rate and cardiovascular disease outcomes in the state of Florida. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 66, 693–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2020). Alzheimer’s Association Facts and Figures, https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2012). Alzheimer’s Disease International World Alzheimer’s Report 2012; Overcoming the Stigma of Dementia. http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimer’sReport2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ball E (2018). Ageism in social work education: A factor in the shortage of geriatric social workers [Master’s Thesis, School of Social Work California State University, Long Beach]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. https://pqdtopen.proquest.com/doc/2036363775.html?FMT=AI [Google Scholar]

- Berkman B, Silverstone B, Simmons W, Volland P, & Howe J (2016). Social work gerontological practice: The need for faculty development in the new millennium, Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 59(2), 162–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chonody J (2018). Perspectives on aging among graduate social work students: Using photographs as an online pedagogical activity. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 18(2). 158–173. [Google Scholar]

- Council on Social Work Education. (2015). Final 2015 educational policy. Retrieved from https://www.cswe.org/getattachment/Accreditation/Accreditation-Process/2015-EPAS/2015EPAS_Web_FINAL.pdf.aspx

- Council on Social Work Education Sage – SW Project. (2006). SAGE-SW Competencies. Retrieved from https://www.cswe.org/Centers-Initiatives/Centers/Gero-Ed-Center/Educational-Resources/Gero-Competencies/Competencies-History#SAGE-SW_Competencies

- Dobbs D, Eckert JK, Rubinstein B, Keimig L, Clark L, Frankowski AC, & Zimmerman S (2008). An ethnographic study of stigma and ageism in residential care or assisted living. The Gerontologist, 48(4), 517–526. 10.1093/geront/48.4.517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Padovani A, Scheltens P, Rossi A, & Dell’Agnello G. (2016). Timely diagnosis for Alzheimer’s Disease: A literature review on benefits and challenges. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 49(3), 617–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps F, Weeks G, Graham E, & Luster D(2018). Challenges to aging in place for African American older adults living with dementia and their families. Geriatric Nursing, 39(6), 646–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwitz JH, & Pearson SD. (2019). Novel therapies for an aging population: Grappling with price, value, and affordability. JAMA, 321(16), 1567–1568. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.2633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper L, Dobbs B, Stites S, Sajatovic M, & Buckwalter K (2019). Stigma in dementia: It’s time to talk about it. Current Psychiatry, 18(7),16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeijmakers L, Lesuis S, Krugers H, Lucassen P, & Korosi A (2018). A preclinical perspective on the enhanced vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease after early-life stress. Neurobiology of Stress, 8, 172–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson RS, & Saif N (2020). A missed opportunity for dementia prevention? Current challenges for early detection and modern-day solutions. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, 7, 291–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane M (2006). Social work students’ perceptions about incompetence in elders. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 47(3–4), 153–171. DOI: 10.1300/J083v47n03_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Barbaresso MM, Lai Z, Nord KM, Bramlet M, Goodrich DE, Post EP, Almirall D, & Bauer MS (2017). Improving physical health in patients with chronic mental disorders: Twelve-month results from a randomized controlled collaborative care trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(1), 129–137. 10.4088/JCP.15m10301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manthorpe Jill, Hart Cathryn, Watts Sue, Goudie Fiona, Charlesworth Georgina, Fossey Jane, & Moniz-Cook Esme (2018). Practitioners’ understanding of barriers to accessing specialist support by family carers of people with dementia in distress. International Journal of Care and Caring, 2(1), 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor J, Ivry J (2013). Advancing Gerontological Social Work Education. The Haworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock S, Burles M, Hodson A, Kumaran M, MacRae R, Peternelj-Taylor C & Holtslander L (2019). Older persons with dementia in prison: an integrative review. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 16(1), 1–16. 10.1108/IJPH-01-2019-0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polese F, Tartaglione A, & Cavasese Y (2016; September 5–6)) Patient empowerment for health service quality improvements: A value co-creation view; 19th Toulon-Verona International Conference, University of Huelva Excellence in Services, Huelva (Spain). Conference Proceedings ISBN 9788890432767. [Google Scholar]

- Radford K, Delbaere K, Draper B, Mack H, Daylight G, Cumming R, Chalkley S, Minogue C, & Broe G (2017). Childhood stress and adversity is associated with late-life dementia in aboriginal Australians. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(10), 1097–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram S, Reisher P, Garlinghouse M,Chiou K, Aaron M, & Ojha T,& Smith L (2019) Screening for brain injury among survivors of domestic violence. Nebraska American Public Health Association Annual Meeting. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, & Fields A. (2016) Defining rural at the US Census Bureau. American community survey and geography brief. 1(8). [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach A, Damron-Rodriguez J, Robinson B, & Feldman R (2000). Educating social workers for an aging society: A vision for the 21st Century. Journal of Social Work Education, 36(3), 521–538. [Google Scholar]

- Sneed RS, & Schulz R (2019). Grandparent caregiving, race, and cognitive functioning in a population-based sample of older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 31(3), 415–438. 10.1177/0898264317733362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z, Damron‐Rodriguez J, Cadogan M, Gans D, Price R, Merkin S, Jennings L, Schickedanz H, Shimomura H, Osterweil D, Chodosh J;(2017). Team‐Based Interprofessional Competency Training for Dementia Screening and Management. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Vol 65:1. 207–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickery B, Mittman B, Connor K, Pearson M, Della Penna R, Ganiats T, DeMonte R,Chodosh J, Cui X, Vassar S, Duan N & Lee M (2006). The effect of a disease management intervention on quality and outcomes of dementia care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 145(10), 713–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel Rachele. Dementia in prison: An argument for training correctional officers (2016). Graduate School of Professional Psychology: Doctoral Papers and Masters Projects. 220. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/capstone_masters/220 [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, & Chonody J (2013). Social workers’ attitudes toward older adults: A review of the literature. Journal of Social Work Education, 49, 150–172. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.