Abstract

Purpose of Review

People living with HIV (PLWH) are at an increased risk for osteoporosis, a disease defined by the loss of bone mineral density (BMD) and deterioration of bone quality, both of which independently contribute to an increased risk of skeletal fractures. While there is an emerging body of literature focusing on the factors that contribute to BMD loss in PLWH, the contribution of these factors to bone quality changes are less understood. The current review summarizes and critically reviews the data describing the effects of HIV, HIV disease-related factors, and antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) on bone quality.

Recent Findings

The increased availability of high resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography has confirmed that both HIV infection and ARVs negatively affect bone architecture. There is considerably less data on their effects on bone remodeling or the composition of bone matrix. Whether changes in bone quality independently predict fracture risk, as seen in HIV uninfected populations, is largely unknown.

Summary

The available data suggests that bone quality deterioration occurs in PLWH. Future studies are needed to define which factors, viral or ARVs, contribute to loss of bone quality and which bone quality factors are most associated with increased fracture risk.

Keywords: Bone mineral density, Bone quality, remodeling, microarchitecture, matrix composition

Introduction

The success of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) has reduced HIV-associated death and thus increased the life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLWH) [1]. Early onset of age-related comorbidities has been observed among PLWH. Osteoporosis and the resulting osteoporotic fractures occur at nearly three times the rate in PLWH when compared to demographically-matched uninfected individuals [2, 3]. Osteoporosis is defined by a loss of bone mineral density (BMD) and deterioration of bone quality, which contribute to an increased risk of fracture. Low BMD is consistently reported in PLWH when compared to demographically matched uninfected individuals [4, 5] and is likely driven by a combination of HIV, HIV viral proteins [6–8], and antiretroviral (ARV) drugs [9–11]. While there have been several reviews focused on the factors that contribute to loss of BMD and increased fracture risk in PLWH on ARVs [3, 9, 12–16], to our knowledge, no reviews have critically evaluated the state of knowledge regarding the impact of HIV and/or ARVs on bone quality.

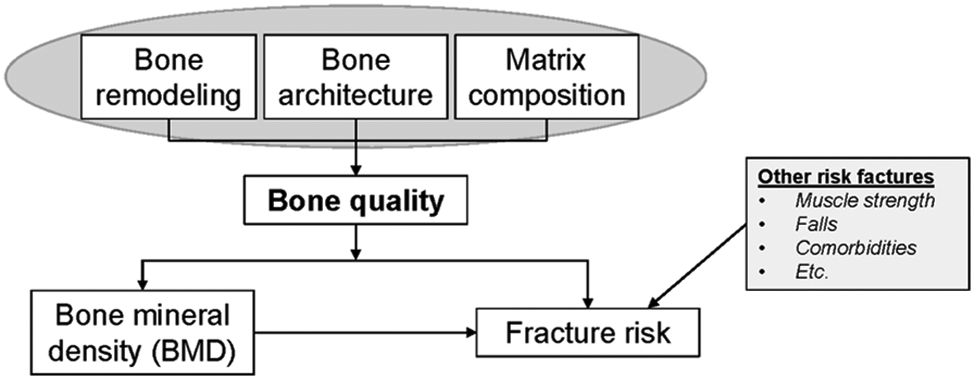

Bone quality describes the factors that contribute to bone strength independent of bone mass or BMD, assessed by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA, Figure 1). Bone quality factors parameters include bone remodeling dynamics, or the activity of bone resorbing osteoclasts and bone forming osteoblasts, the spatial distribution of bone tissue in space (cortical geometry and trabecular microarchitecture), chemical composition of the bone extracellular matrix [17], all of which contribute to fracture risk independent of BMD [18–20]. A large number of review articles have been written on the importance of [19, 21–23] and measurement strategies to assess bone quality [24, 25], therefore, we will refer the reader to these articles for a formal description of these concepts. Instead, this review focuses on the effects of HIV and the antiretroviral drugs on bone quality. This review is timely as recent data suggests that decreased BMD does not fully explain the increased fracture risk noted in PLWH [26], and that loss of bone quality occurs coincident with the loss of DXA-defined BMD.

Figure 1:

Bone quality schematic. Bone quality is defined as factors, such as bone remodeling rates, bone architecture, and matrix composition, that can affect dual energy x-ray absorptiometry measures of bone mineral density (BMD) and independently contribute to skeletal fracture risk. The current review focuses on the effects of HIV and ARVs on the factors that make up bone quality. A variety of other non-skeletal risk factors also contribute to fracture risk, such as muscle strength and falls, that are outside of the scope of the current review.

HIV and ARV Effects on Bone Cell Activity

The skeleton undergoes continuous self-renewal through a process known as bone remodeling. Bone remodeling is defined by the coordinated actions of bone resorbing osteoclasts and bone forming osteoblasts [27]. Due to the complexity of bone remodeling and the yet fully defined coupling factors linking osteoclasts with osteoblasts, it is common practice to investigate the effects of outside stimuli directly on primary osteoclasts and osteoblasts separately in vitro. Additionally, various studies have assessed osteoclast or osteoblast activity in response to the HIV, HIV viral products, or ARVs in preclinical animal models and human subjects. Below we provide a narrative review of the published data and include summary tables of the effects of the HIV virus and HIV viral products (Table 1) or ARVs (Table 2) on osteoclasts and osteoblasts.

Table 1:

HIV effects on osteoclast and osteoblast activity

| Citation | Virus/Viral Product | Model System | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoclasts | |||

| Gohda et al. [30] |

|

|

|

| Raynaud-Messina et al. [31] |

|

|

|

| Mascarau et al. [38] |

|

|

|

| Fakruddin et al. [41] |

|

|

|

| Osteoblasts | |||

| Nacher et al. [56] |

|

|

|

| Gibellini et al. [55] |

|

|

|

| Cummins et al. [71] |

|

|

|

| Cotter et al. [57] |

|

|

|

| Beaupere et al. [58] |

|

|

|

Table 2:

ARV effects on osteoclast and osteoblast activity

| Citation | ARV Treatment | Model System | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Osteoclasts | |||

| Jain et al. [49] |

|

|

|

| Yin et al. [51] |

|

|

|

| Modarressi et al. [50] |

|

|

|

| Osteoblasts | |||

| Jain et al. [49] |

|

|

|

| Hernandez-Vallejo et al. [61] |

|

|

|

| Malizia et al. [63] |

|

|

|

| Malizia et al. [64] |

|

|

|

| Barbieri et al. [68] |

|

|

|

| Cazzaniga et al. [62] |

|

|

|

HIV and ARV effects on Osteoclasts

Bone resorbing osteoclasts differentiate from the monocyte/macrophage lineage [28], which are known to be infected by HIV [29]. Therefore, it is not surprising that osteoclasts themselves are also targets for HIV infection [30, 31]. Raynaud-Messina et al. confirmed the presence of HIV-infected osteoclasts in bones derived from HIV-1–infected BLT-humanized mice and in human synovial explant tissues [31]. HIV-infection promotes osteoclast differentiation, expression of pro-resorptive genes, and osteolytic activity in vitro [30, 31].

Osteoclast survival, proliferation, differentiation, and activation are driven by interactions between soluble receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) and its receptor, the receptor activator of nuclear factor κB (RANK). Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a soluble antagonist to RANKL [32, 33] and the RANKL/OPG ratio is commonly used to monitor bone remodeling activity [34]. The OPG/RANKL ratio is significantly lower in cART naïve PLWH with low BMD and RANKL levels are positively associated with HIV viral load [35]. However, circulating OPG levels and not the OPG/RANKL ratio have been reported to be associated with BMD [36, 37]. Changes in the expression of OPG and RANKL in PLWH appear to be due to aberrant expression by HIV-infected immune cells. For example, macrophages [38], B-cells [7], and T-cells [39] are all reported to have increased RANKL and decreased OPG expression in response to HIV infection. Mechanistic studies using cultured human T-cells have shown that exposure to HIV viral proteins such as Vpr [40] or gp120 [41] is sufficient to upregulate the expression of RANKL. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that elevated bone resorption in PLWH is likely a combination of both direct HIV infection and indirect activation of HIV-infected immune cells. A more detailed description of the role of RANKL and OPG in HIV can be found here [42].

The initiation of cART therapy can also promote osteoclast differentiation and activation either directly or indirectly through immune cell-mediated effects. The initiation of cART is associated with suppression of HIV replication, resulting in immune reconstitution including repopulation of the CD4+ T-cells [43]. Despite the importance of ARV-induced immune reconstitution in prolonging the lifespan of PLWH, immune reconstitution is also associated with an increased release of pro-inflammatory cytokines [44], which may contribute to bone loss. For example, immune reconstitution following cART initiation is associated with an increase in circulating RANKL and TNFα [45], which promote osteoclastogenesis [46]. Ofotokun et al. reported that the degree of bone loss in PLWH is positively associated with the magnitude of immune reconstition. PLWH with the greatest increase in CD4+ cell count following cART initaition experience the greatest BMD loss [45].

ARVs can also directly influence osteoclast activity. While one study found that an association between tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) exposure and increased circulating RANKL levels after cART initiation [47], others have failed to find an association between RANKL or the OPG/RANKL ratio and bone loss regardless of the cART regimen initiated [47, 48]. While some of the cART initiation data suggest that direct effects of ARVs on bone cells may contribute to the observed decrease in BMD, because regimens are given as combinations of 2 to 3 ARVs it is difficult to sort out independent effects. Relatively few studies have investigated the direct effects of ARVs on osteoclasts in vitro. The three studies that have been performed have primarily focused on protease inhibitors (PI) which are no longer used in the management of HIV. Jain et al. noted that osteoclast activity is elevated in response to treatment with nelfinavir (NFV), indinavir (IDV), saquinavir (SQV), or ritonavir (RTV) [49]. In contrast, Fakruddin et al. reported that RTV and SQV, but not IDV or NFV enhanced osteoclast differentiation [41]. The same group further reported that these effects are likely driven by the suppression of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in osteoclast precursors [50]. The increased osteoclast activity following PI exposure was confrimed by Yin et al. who demonstrated greater osteoclast differentiation potential of PBMCs isolated from PLWH treated with RTV when compared to other ARVs [51]. However, at least one study using murine bone marrow macrophages reported that RTV inhibits osteoclast differentiation and function [52]. These contradictory findings may be due to differences in human versus mouse cells or the significant differences in the concentrations of ARVs investigated, which ranged from 0.7–3.6 μg/mL [41, 50] to 10–20 μg/mL [52], stressing the importance of future experiments to determine the concentration of ARVs that reach the bone microenvironment. Further, it is important to determine the effects of newer, more widely used ARVs on osteoclast function to fully appreciate their effects on bone.

HIV and ARV effects on Osteoblasts

Bone matrix is formed by osteoblasts, which differentiate from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). After synthesizing the new bone matrix, a small fraction of osteoblasts become trapped within the bone and terminally differentiate into osteocytes [53], a long-lived cell responsible for mediating the skeletal response to mechanical loading and producing bone-derived hormones [54]. Despite detectable mRNA expression of HIV binding receptors CD4 and CCR5 [55], neither cultured osteoblasts nor osteoblasts isolated from PLWH show evidence of HIV infection [55, 56]. However, viral products, including gp120 [55], gag p55 [57], Tat and Nef [58] all of which continue to circulate even in well controlled PLWH [59, 60], have all been reported to impair osteoblast differentiation or function in vitro (summarized in Table 1).

In vitro studies have demonstrated the deleterious effects of various ARVs on the differentiation and function of osteoblasts [49, 61, 62]. For instance, treatment of cultured MSCs with PIs, atazanavir (ATV) or lopinavir (LPV), induced cell senesence and inhibited osteoblast differentiation [61]. Interestingly, RTV alone had no effect on osteoblast differentiation [61]. A similar study by Jain et al. comparing the effects of several PIs on MSCs reported that NFV, SQV, LPV, and RTV were all able to inhibit osteoblast differentiation, as measured by alkaline phosphatase staining, while amprenavir (APV) and IDV had no effect [49]. While the two studies differed in their conclusions regarding the effects of RTV on osteoblast differentiation, the discrepancy likely stems from the differences in ARV concentrations employed. The former study by Hernandez-Vallejo et al. [61] used 10 μM LPV and 2 μM RTV, while the study by Jain et al. [49] used 10 or 20 μM for each PI tested; highlighting the need for future work defining the concentration of ARVs that reach the bone microenvironment in vivo.

Protease inhibitors also inhibit the function of mature osteoblasts. Malizia et al. exposed mature human osteoblasts to several PIs, including SQV, RTV, NFV and IDV, and found that NFV and IDV impaired matrix formation in vitro [63]. Subsequent microarray analysis identified that the extracellular matrix regulator TIMP-3 is upregulated in response to NFV and IDV, and suppression of TIMP-3 transcription prevented NFV and IDV induced matrix inhibition [63]. Cazzaniga et al. investigated the terminal differentiation of osteoblasts by monitoring the expression of the osteocyte markers sclerostin and dental matrix protein 1 (DMP1) and noted that ATV but not darunavir (DRV) inhibited osteocyte-related gene expression [62]. In addition to inhibiting differentiation and matrix production, NFV and RTV are also reported to promote the osteoblast expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP)-1 and interleukin-8 (IL-8) [64], both of which are associated with increased osteoclastogenesis and subsequent bone resorption [65, 66].

Relatively little is known about the effects of non-PI ARVs on osteoblast function. Despite the well-described bone loss associated with TDF [67], only one study has investigated its effects on osteoblast function and found that TDF inhibited matrix formation by reducing the extent of calcification and suppressing the expression of collagen I [68]. Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) are now recommended as part of first line cART regimens, yet, to date, only one study has investigated the effects of INSTIs on osteoblasts, reporting that dolutegravir (DTG), inhibits both the differentiation of osteoblasts from MSCs and the terminal differentiation of osteoblasts into osteocytes, as evidenced from impaired expression of sclerostin and DMP1 [62]. Further work is necessary to establish the effects of newer generation INSTIs such as bictegravir, or commonly used nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), such as emtricitabine, lamivudine or abacavir on osteoblast function. Finally, apart from the study by Cazzaniga et al. [62], the effects of ARVs on osteocytes remain largely unknown. Importantly, osteocytes constitute between 90 and 95% of bone cells and are master regulators of bone remodeling, as well as the primary producer of fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a bone-derived hormone responsible for controlling phosphate metabolism [69, 70].

Bone remodeling

Bone cell activity

Bone remodeling involves the coordinated action of osteoclasts and osteoblasts. A variety of studies have investigated the effects of HIV and ARVs on osteoclast and osteoblast activity separately, and from these results, inferred the cumulative effects on bone remodeling. A more complete understanding of bone remodeling requires directly investigating bone tissues from PLWH.

Due to the inherent difficulty of obtaining bone samples from PLWH, many of the tissue-level remodeling measurement studies have been performed in preclinical animal models. Raynaud-Messina et al. [31] and Vikulina et al. [72] used the Nef overexpressing mouse and the HIV transgenic rat, respectively, to model HIV infection and demonstrated elevated tissue-level osteoclast activity in both animal models. Relatively few studies have evaluated the effects of ARVs on bone tissue and those that have are limited primarily to characterization of the effects of tenofovir, which reduces the number of osteoblasts and increases the number of osteoclasts in mice [73], zebrafish [74], and primates [75]. Although ARVs are administered in combination clinically, to our knowledge, there have been no studies evaluating the effects of cART regimens on tissue-level remodeling in these preclinical models.

At least two studies have evaluated tissue-level remodeling in human biopsies. Serrano et al. evaluated bone tissue biopsies taken from cART naïve PLWH and compared histological measures of bone remodeling according to HIV-uninfected controls [76]. Bone samples from PLWH had decreased osteoblast and osteoclast surfaces, bone formation rate, and activation frequency when compared to tissues from uninfected patients and the all parameters were further reduced in those with the most severe disease. Ramalho et al. evaluated bone tissue biopsies taken from men with HIV prior to and 12-months after initiating a fixed dose cART regimen of TDF/3TC/EFV [77]. Prior to cART initiation, PLWH have an elevated number of osteoclasts and increased eroded surface, a measure of osteoclast activity. Additionally, bone formation rate was lower and the mineralization lag time was elevated among PLWH prior to cART initiation when compared to an uninfected reference cohort. After cART initiation, osteoid volume, osteoblast surface, and osteoclast surface indices all increased, confirming the elevated bone remodeling in response to ARVs. A detailed summary of the in vivo effects of HIV and ARVs on bone remodeling is presented in Table 3.

Table 3:

HIV and ARV effects on tissue-level bone remodeling parameters.

| Citation | Treatment | Model | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raynaud-Messina et al. [31] |

|

|

|

| Vikulina et al. [72] |

|

|

|

| Ofotokun et al. [113] |

|

|

|

| Weitzmann et al [116] |

|

|

|

| Serrano et al [76] |

|

|

|

| Matuszewska et al. [117] |

|

|

|

| Castillo et al. [75] |

|

|

|

| Carnovali et al. [74] |

|

|

|

| Conesa-Buend et al. [73] |

|

|

|

| Conradie et al. [118] |

|

|

|

| Ramalho et al. [77] |

|

|

|

The tenofovir isoform used in this study was specifically designed for preclinical studies [119].

Bone turnover markers (BTMs)

In lieu of bone biopsies, bone cell activity is commonly assessed clinically using circulating bone turnover markers (BTMs), or the protein products of bone remodeling released into the circulation due to bone cell activity. BTMs are used to compliment DXA-based BMD measures in the diagnosis of osteoporosis and have been reported to predict fracture risk independent of BMD [78, 79]. Moreover, changes in BTMs have been proposed as a method to monitor the response to osteoporosis treatments [80], including in PLWH [81, 82]. In cART naïve PLWH, serum calcium, phosphate, and 25-hydroxy vitamin D are all reduced when compared to HIV-uninfected individuals, as are BTMs commonly associated with bone formation, including osteocalcin and amino-terminal propeptide of type 1 procollagen (P1NP) [7, 83–86]. In contrast, BTMs released during bone resorption, such as C-terminal telopeptide of collagen (CTX), are elevated when compared to HIV uninfected individuals [7].

The initiation of cART is also associated with changes in the circulating levels of BTMs. Indeed, cART initiation increases osteoblast-derived, osteocalcin and P1NP, and osteoclast-derived, CTX, as early as 3 to 6 months post cART initiation [85, 87–89]. The peak levels of circulating BTMs are generally achieved between 12–48 weeks following cART initiation before reaching a new steady state [85, 89–92], which appears to be higher than what is reported in cART naïve PLWH.

BTMs have also been used to evaluate the extent of ARV effects on bone. For example, changes in both bone resorption (CTX) and bone formation (P1NP and bone specific alkaline phosphatase) were reported to be greater in PLWH initiating TDF/FTC when compared to abacavir (ABC)/3TC [90, 93]. The initiation of TDF-based cART increases circulating RANKL levels more than TDF-sparing cART regimens [47]. Compared to TDF based therapy, cART containing INSTIs appear to cause less bone remodeling. For example, compared to PLWH initiating TDF-based therapy, those receiving either raltegravir (RAL) [94] or DTG-based treatment [92] exhibit smaller changes in BTM levels. Switching regimens can also affect BTM levels. For example, switching from zidovudine (AZT)-based cART onto a TDF-based regimen resulted in a significant increase in the circulating levels of CTX, P1NP, and osteocalcin [95]. Switching from TDF-based cART onto a regimen of ABC/3TC+ATV resulted in reduced circulating bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, CTX, and osteocalcin [96, 97] and switching from TDF-based cART to either RAL- [98] or DTG-based cART [99] similarly reduced BTM level. For a more detailed review on the various studies that have assessed BTMs in PLWH, the reader is referred to the following review specifically addressing this topic [100].

Circulating bone-related proteins have also been measured to assess the mechanistic drivers of HIV and ARV-associated bone loss. Sclerostin is an osteocyte-derived regulator of bone remodeling that is reported to decrease with the initiation of cART [84]. Switching from more bone-toxic TDF-containing cART regimens to those containing ABC led to increased sclerostin levels [96]. Importantly, higher sclerostin levels have been shown to be positively associated with increased BMD in PLWH [101, 102] and findings from Ross et al. [101] suggest that the relationship between sclerostin and BMD is influenced by HIV-serostatus [101]. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is another regulator of bone remodeling that is reported to be elevated in both cART naïve PLWH and following cART initiation [85, 89]. The extent of PTH increase following cART is greater in PLWH receiving TDF-containing cART [103], which may be due to low circulating vitamin D levels [104] or TDF-induced alterations the PTH and vitamin D relationship responsible for regulating circulating mineral homeostasis [105]. While vitamin D is a critical regulator of calcium homeostasis and bone health, a formal review of the potential role of vitamin D in HIV is outside of the scope of the current review and the reader is instead pointed to a recent summary [106]. Finally, novel studies evaluating potential mechanistic drivers of bone loss have reported that extracellular vesicles expressing markers of bone activity [107] and bone remodeling regulating microRNAs, 23a-3p, 24–2-5p, and 21–5p [108], are associated with BMD in PLWH.

The circulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines have also been evaluated as a potential mechanism of bone loss. Markers of immune activation remain elevated in PLWH on cART when compared to uninfected people [109, 110]. Higher baseline levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines known to affect bone cell function [111] including IL-6 are associated with greater BMD loss after cART initiation [112]. Soluble CD14 levels, a marker of immune activation, found on the surface of monocytes and macrophages, are also associated with greater BMD loss [112], confirming that immune reconstitution contributes to HIV and ARV-induced bone loss. Indeed, immune reconstitution suppresses histomorphometric indices of osteoblast activity in a mouse model of T-cell reconstitutiuon [113]. Additionally, both Gazzola et al. [114] and Manavalan et al. [115] showed that immune activation in PLWH is associated with lower BMD and Manavalan et al. further implicated a reduction in circulating osteoblast precursor cells as a probable mechanism of bone loss.

Bone Architecture

Osteoporosis is also characterized by a deterioration of bone architecture, which can negatively affect bone strength and fracture resistance independently of BMD [94, 120–122]. A variety of preclinical rodent studies have leveraged the widespread availability of micro-computed tomography (μCT) to investigate the effects of HIV and ARVs on bone architecture. For example, μCT measurements have only been performed in the HIV transgenic rat model, which confirmed the negative effects of HIV viral proteins on bone architecture in addition to the negative effects on bone mass [72]. Several well-designed studies have utilized the TCRβ knockout (KO) mouse model to simulate immune reconstitution following cART initiation in PLWH [113, 123]. These studies have demonstrated the negative effects of immune reconstitution on bone architecture [113], confirmed the importance of CD4+ T-cells on these negative effects [123] and more recently confirmed that the effects of immune reconstitution accelerate age-related bone architectural deterioration [116].

The individual effects of ARVs have been tested in uninfected rodents. These studies have included confirmation that tenofovir negatively affect bone architecture in both mouse and rat models, in addition to its negative effects on bone mass [73, 117]. Interestingly, while femoral architecture is affected in both models, Matuszewska et al. [117] reported that tenofovir had no effects in the lumbar vertebra or tibia, which may suggest site-specificity. In contrast, ABC may have positive effects on bone architecture, with increased bone volume fraction and trabecular number noted in the tibiae following long-term ABC administration in growing rats [124].

The first studies evaluating bone architecture in PLWH used DXA data from the lumbar spine to assess the trabecular bone score (TBS), which has been reported to be a risk factor for osteoporotic fracture independent of BMD [125]. In further support of the clinical relevance of TBS, Ciullini et al. demonstrated that TBS is significantly reduced in PLWH with vertebral fractures compared to those without, while BMD was not [126]. Additionally, McGinty et al. reported that HIV-serostatus significantly reduces TBS independently of lumbar spine bone mineral content (BMC) [127]. Interestingly, while several studies have confirmed that HIV-serostatus reduces TBS [126–128], the age-related change in TBS does not appear to vary according to HIV-serostatus [129]. TBS relies on DXA-based imaging to obtain an indirect measure of bone architecture, which are relatively well correlated with more direct architecture measures [130] but can be negatively impacted by imaging noise [131].

The increasing availability of high resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography (HRpQCT) has made it possible to perform high resolution imaging of bone architecture in PLWH (Table 4). Kazakia et al. showed that despite having comparable BMD, HIV infected men on long term cART have reduced bone architecture when compared to age-matched HIV uninfected men [132]. Biver et al. [133] reported that HIV-serostatus negatively affects bone architecture independently of classical clinical risk factors, such as age, BMI, and low vitamin D levels. Instead, HIV-induced architectural degradation was primarily associated with CTX levels, suggesting that increased resorption with HIV infection was the driver of architectural loss [133]. In addition to HIV infection-induced impairment of bone architecture [134–136], cART use, particularly TDF, negatively affects bone architecture [134, 137, 138]. Additional risk factors, such as poor nutrition and low physical activity have been reported to negatively affect bone architecture in PLWH [139]. To date, HRpQCT studies in PLWH have been cross-sectional, therefore future studies are needed to determine whether the age-related change in architectural parameters differ as a function of HIV serostatus.

Table 4:

Summary table of clinical findings of the effects of HIV and ARV on bone architecture

| Citation | Study Design | Imaging Strategy | Primary Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| McGinty et al. [127] |

|

|

|

| Kim et al. [128] |

|

|

|

| Sharma et al. [129] |

|

|

|

| Guerri-Fernandez et al. [142] |

|

|

|

| Guerri-Fernandez et al. [144] |

|

|

|

| Ciullini et al. [126] |

|

|

|

| Pitukcheewanont et al. [145] |

|

|

|

| Kazakia et al. [132] |

|

|

|

| Biver et al. [133] |

|

|

|

| Yin et al. [137] |

|

|

|

| Macdonald et al. [134] |

|

|

|

| Shiau et al. [135] |

|

|

|

| Sellier et al [138] |

|

|

|

| Tan et al. [146] |

|

|

|

| Calmy et al. [136] |

|

|

|

| Foreman et al. [139] |

|

|

|

| Abraham et al. [147] |

|

|

|

Failure load was estimated using finite element analysis

Combining HRpQCT measurements with finite element (FE) analysis is a powerful tool to non-invasively and non-descriptively assess mechanical properties of bone tissue. Importantly, FE-based estimates of bone strength have been shown to be significant predictors of fracture risk after adjusting for BMD in HIV uninfected people [140, 141]. Macdonald et al. [134] noted decreased FE-based bone strength measures in HIV-infected women when compared to uninfected women that remained significant after adjusting for a variety of characteristics and risk factors. Foreman et al. [139] further noted that longer-term HIV-infection and the combination of TDF and PI use were associated with decreased FE-based estimates of bone strength. It is yet to be determined whether these FE-based bone strength measures are similarly predictive of fracture risk as has been established in the uninfected population.

Additional studies by Guerri-Fernandez et al. [142, 143] used micro-indentation to directly measure bone strength. Their results have shown that after adjusting for sex, age, BMI and vitamin D status, bone material strength index (BMSi) was reduced in PLWH independently of BMD [143] and that TDF treatment significantly reduced BMSi when compared to ABC-based cART [142]. Importantly, BMSi assesses changes in the material properties of bone, suggesting that both HIV infection and cART treatments negatively affect the matrix composition of the bone material.

Matrix Composition

Bone as a structure derives its strength from the amount of bone, bone mass, the organization of bone, architecture, and the chemical makeup of the bone tissue, matrix composition. Changes to matrix composition can significantly affect bone strength even with minimal changes in BMD [148]. Although micro-indentation studies by Guerri-Fernandez et al. [142, 143] suggest that HIV-serostatus and cART treatment can negatively affect matrix composition, there have been no direct measures in either preclinical models or in human samples. Histological based measurements of mineralization are the best proxy to evaluate matrix composition in PLWH. As such, the study by Ramalho et al. evaluating biopsies from PLWH found no difference prior to and after cART initiation in either osteoid thickness or mineralization lag time measures [77]. However, it is worth noting that both prior to and post-cART, the mineralization lag time values were nearly double that of the reference population [77], which may suggest delayed skeletal mineralization occurs in PLWH. This measure, combined with the data presented in Tables 1 and 2, showing impaired osteoblast differentiation and function provide further motivation for future studies to directly compare the effects of HIV and cART on bone matrix composition.

Conclusion and Persective

While osteoporosis is diagnosed clinically by low BMD, there is a growing appreciation for the BMD-independent factors, termed bone quality, that contribute to increase fracture risk. Additional investigation is necessary to fully define the contribution of HIV-related factors to bone quality changes as PLWH age. For example, while BTMs have become more commonly evaluated in PLWH, the direct effect of HIV on bone cells is limited to in vitro culture systems studying each bone cell separately. Although these in vitro studies can separately investigate the contribution of individual ARVs or specific HIV-associated viral factors, they have not investigated the potential synergistic effects of the multitude of factors experienced by PLWH. Further, it is difficult to study osteocytes using in vitro systems and therefore, the effects of HIV, HIV-related factors, and antiretrovirals on the longest lived and most abundant bone cells is largely unknown. Direct investigation of bone tissue samples from PLWH would overcome many of the current limitations in the published studies, including establishing the consequences of altered osteoblast and osteoclast function, determining the response of osteocytes, determining whether these cellular effects lead to changes in the bone matrix composition or mechanical properties of bone. However, the difficulty in obtaining bone tissue for PLWH makes these studies complicated and therefore, efforts should be made to establish preclinical HIV models of bone mass and quality loss. An effective model would help to disentangle the individual and combined contributions of HIV, HIV-related factors, and antiretrovirals to bone quality changes, establish the mechanisms of action, and potentially identify disease modifying treatment strategies.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a subcontract from Cook County Clinical Research Site of the MWCCS (U01HL146245) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin (NIAMS) under grant number AR079309 (RDR), National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) under grant K24AI155230 (MTY), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) under grant number 1U01HL14204 (AS). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Reference

- 1.Wandeler G, Johnson LF, and Egger M, Trends in life expectancy of HIV-positive adults on antiretroviral therapy across the globe: comparisons with general population. Curr Opin HIV AIDS, 2016. 11(5): p. 492–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown TT and Qaqish RB, Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis: a meta-analytic review. AIDS, 2006. 20(17): p. 2165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Premaor MO and Compston JE, The Hidden Burden of Fractures in People Living With HIV. JBMR Plus, 2018. 2(5): p. 247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran CA, Weitzmann MN, and Ofotokun I, Bone Loss in HIV Infection. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis, 2017. 9(1): p. 52–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang CJ, et al. , People with HIV infection had lower bone mineral density and increased fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Arch Osteoporos, 2021. 16(1): p. 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeng YQ, et al. , Prevalence and risk factors for bone mineral density changes in antiretroviral therapy-naive human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults: a Chinese cohort study. Chin Med J (Engl), 2020. 133(24): p. 2940–2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Titanji K, et al. , Dysregulated B cell expression of RANKL and OPG correlates with loss of bone mineral density in HIV infection. PLoS Pathog, 2014. 10(10): p. e1004497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoy JF, et al. , Immediate Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection Accelerates Bone Loss Relative to Deferring Therapy: Findings from the START Bone Mineral Density Substudy, a Randomized Trial. J Bone Miner Res, 2017. 32(9): p. 1945–1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compston J, HIV infection and osteoporosis. Bonekey Rep, 2015. 4: p. 636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGinty T, et al. , Does systemic inflammation and immune activation contribute to fracture risk in HIV? Current opinion in HIV and AIDS, 2016. 11(3): p. 253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr A, et al. , The rate of bone loss slows after 1–2 years of initial antiretroviral therapy: final results of the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Therapy (START) bone mineral density substudy. HIV Med, 2020. 21(1): p. 64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McComsey GA, et al. , Bone disease in HIV infection: a practical review and recommendations for HIV care providers. Clin Infect Dis, 2010. 51(8): p. 937–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delpino MV and Quarleri J, Influence of HIV Infection and Antiretroviral Therapy on Bone Homeostasis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne), 2020. 11: p. 502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiau S, Arpadi SM, and Yin MT, Bone Update: Is It Still an Issue Without Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate? Curr HIV/AIDS Rep, 2020. 17(1): p. 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grant PM and Cotter AG, Tenofovir and bone health. Curr Opin HIV AIDS, 2016. 11(3): p. 326–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran CA, Weitzmann MN, and Ofotokun I, The protease inhibitors and HIV-associated bone loss. Curr Opin HIV AIDS, 2016. 11(3): p. 333–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt HB and Donnelly E, Bone quality assessment techniques: geometric, compositional, and mechanical characterization from macroscale to nanoscale. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab, 2016. 14(3): p. 133–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nih Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, D. and Therapy, Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA, 2001. 285(6): p. 785–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seeman E and Delmas PD, Bone quality--the material and structural basis of bone strength and fragility. N Engl J Med, 2006. 354(21): p. 2250–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner CH, Biomechanics of bone: determinants of skeletal fragility and bone quality. Osteoporos Int, 2002. 13(2): p. 97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouxsein ML, Bone quality: where do we go from here? Osteoporosis International, 2003. 14(5): p. 118–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unnanuntana A, et al. , Diseases Affecting Bone Quality: Beyond Osteoporosis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®, 2011. 469(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Compston J, Bone quality: what is it and how is it measured? Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol, 2006. 50(4): p. 579–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donnelly E, Methods for assessing bone quality: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2011. 469(8): p. 2128–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Surowiec RK, Allen MR, and Wallace JM, Bone hydration: How we can evaluate it, what can it tell us, and is it an effective therapeutic target? Bone Rep, 2022. 16: p. 101161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Starup-Linde J, et al. , Management of Osteoporosis in Patients Living With HIV—A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 2020. 83(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hadjidakis DJ and Androulakis II, Bone remodeling. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 2006. 1092: p. 385–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kylmaoja E, et al. , Peripheral blood monocytes show increased osteoclast differentiation potential compared to bone marrow monocytes. Heliyon, 2018. 4(9): p. e00780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell JH, et al. , The importance of monocytes and macrophages in HIV pathogenesis, treatment, and cure. AIDS, 2014. 28(15): p. 2175–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gohda J, et al. , HIV-1 replicates in human osteoclasts and enhances their differentiation in vitro. Retrovirology, 2015. 12(1742–4690 (Electronic)): p. 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raynaud-Messina B, et al. , Bone degradation machinery of osteoclasts: An HIV-1 target that contributes to bone loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2018. 115(11): p. E2556–E2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Simonet WS, et al. , Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell, 1997. 89(2): p. 309–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson DM, et al. , A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature, 1997. 390(6656): p. 175–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyce BF and Xing L, Functions of RANKL/RANK/OPG in bone modeling and remodeling. Arch Biochem Biophys, 2008. 473(2): p. 139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gibellini D, et al. , RANKL/OPG/TRAIL plasma levels and bone mass loss evaluation in antiretroviral naive HIV-1-positive men. J Med Virol, 2007. 79(10): p. 1446–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelesidis T, et al. , Brief Report: Changes in Plasma RANKL-Osteoprotegerin in a Prospective, Randomized Clinical Trial of Initial Antiviral Therapy: A5260s. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2018. 78(3): p. 362–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seminari E, et al. , Osteoprotegerin and bone turnover markers in heavily pretreated HIV-infected patients. HIV Med, 2005. 6(3): p. 145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mascarau R, et al. , HIV-1-Infected Human Macrophages, by Secreting RANK-L, Contribute to Enhanced Osteoclast Recruitment. Int J Mol Sci, 2020. 21(9): p. 3154. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Titanji K, et al. , T-cell receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand/osteoprotegerin imbalance is associated with HIV-induced bone loss in patients with higher CD4+ T-cell counts. AIDS, 2018. 32(7): p. 885–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fakruddin JM and Laurence J, HIV-1 Vpr enhances production of receptor of activated NF-κB ligand (RANKL) via potentiation of glucocorticoid receptor activity. Archives of Virology, 2005. 150(1): p. 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fakruddin JM and Laurence J, HIV envelope gp120-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis via receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) secretion and its modulation by certain HIV protease inhibitors through interferon-gamma/RANKL cross-talk. J Biol Chem, 2003. 278(48): p. 48251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelesidis T, et al. , Role of RANKL-RANK/osteoprotegerin pathway in cardiovascular and bone disease associated with HIV infection. AIDS Rev, 2014. 16(3): p. 123–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mayer KH, et al. , Immune Reconstitution in HIV-Infected Patients. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2004. 38(8): p. 1159–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Müller M, et al. , Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis, 2010. 10(4): p. 251–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ofotokun I, et al. , Antiretroviral therapy induces a rapid increase in bone resorption that is positively associated with the magnitude of immune reconstitution in HIV infection. AIDS (London, England), 2016. 30(3): p. 405–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ponzetti M and Rucci N, Updates on Osteoimmunology: What’s New on the Cross-Talk Between Bone and Immune System. Frontiers in endocrinology, 2019. 10: p. 236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown TT, et al. , Bone turnover, osteoprotegerin/RANKL and inflammation with antiretroviral initiation: tenofovir versus non-tenofovir regimens. Antivir Ther, 2011. 16(7): p. 1063–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathiesen IH, et al. , Complete manuscript Title: Changes in RANKL during the first two years after cART initiation in HIV-infected cART naive adults. BMC infectious diseases, 2017. 17(1): p. 262–017-2368-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jain RG and Lenhard JM, Select HIV protease inhibitors alter bone and fat metabolism ex vivo. The Journal of biological chemistry, 2002. 277(22): p. 19247–19250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Modarresi R, et al. , WNT/beta-catenin signaling is involved in regulation of osteoclast differentiation by human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor ritonavir: relationship to human immunodeficiency virus-linked bone mineral loss. Am J Pathol, 2009. 174(1): p. 123–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yin MT, et al. , Effects of HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy with ritonavir on induction of osteoclast-like cells in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int, 2011. 22(5): p. 1459–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang MW, et al. , The HIV protease inhibitor ritonavir blocks osteoclastogenesis and function by impairing RANKL-induced signaling. J Clin Invest, 2004. 114(2): p. 206–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rutkovskiy A, Stenslokken KO, and Vaage IJ, Osteoblast Differentiation at a Glance. Med Sci Monit Basic Res, 2016. 22: p. 95–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robling AG and Bonewald LF, The Osteocyte: New Insights. Annu Rev Physiol, 2020. 82: p. 485–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gibellini D, et al. , HIV-1 triggers apoptosis in primary osteoblasts and HOBIT cells through TNFalpha activation. Journal of medical virology, 2008. 80(9): p. 1507–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nacher M, et al. , Osteoblasts in HIV-infected patients: HIV-1 infection and cell function. AIDS (London, England), 2001. 15(17): p. 2239–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cotter EJ, et al. , Mechanism of HIV protein induced modulation of mesenchymal stem cell osteogenic differentiation. BMC musculoskeletal disorders, 2008. 9: p. 33–2474-9–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beaupere C, et al. , The HIV proteins Tat and Nef promote human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell senescence and alter osteoblastic differentiation. Aging cell, 2015. 14(4): p. 534–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Imamichi H, et al. , Defective HIV-1 proviruses produce novel protein-coding RNA species in HIV-infected patients on combination antiretroviral therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(31): p. 8783–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Imamichi H, et al. , Defective HIV-1 proviruses produce viral proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2020. 117(7): p. 3704–3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hernandez-Vallejo SJ, et al. , HIV protease inhibitors induce senescence and alter osteoblastic potential of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells: beneficial effect of pravastatin. Aging Cell, 2013. 12(6): p. 955–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cazzaniga A, et al. , Unveiling the basis of antiretroviral therapy-induced osteopenia: the effects of Dolutegravir, Darunavir and Atazanavir on osteogenesis. Aids, 2021. 35(2): p. 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Malizia AP, et al. , HIV protease inhibitors selectively induce gene expression alterations associated with reduced calcium deposition in primary human osteoblasts. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 2007. 23(2): p. 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Malizia AP, et al. , HIV1 protease inhibitors selectively induce inflammatory chemokine expression in primary human osteoblasts. Antiviral Res, 2007. 74(1): p. 72–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bendre MS, et al. , Interleukin-8 stimulation of osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption is a mechanism for the increased osteolysis of metastatic bone disease. Bone, 2003. 33(1): p. 28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kim MS, et al. , MCP-1-induced human osteoclast-like cells are tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, NFATc1, and calcitonin receptor-positive but require receptor activator of NFkappaB ligand for bone resorption. J Biol Chem, 2006. 281(2): p. 1274–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Grigsby IF, et al. , Tenofovir-associated bone density loss. Ther Clin Risk Manag, 2010. 6: p. 41–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barbieri AM, et al. , Suppressive effects of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, an antiretroviral prodrug, on mineralization and type II and type III sodium-dependent phosphate transporters expression in primary human osteoblasts. Journal of cellular biochemistry, 2018. 119(6): p. 4855–4866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bonewald LF, The amazing osteocyte. J Bone Miner.Res, 2011. 26(2): p. 229–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Delgado-Calle J and Bellido T, The osteocyte as a signaling cell. Physiological Reviews, 2022. 102(1): p. 379–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cummins NW, et al. , Human immunodeficiency virus envelope protein Gp120 induces proliferation but not apoptosis in osteoblasts at physiologic concentrations. PloS one, 2011. 6(9): p. e24876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Vikulina T, et al. , Alterations in the immuno-skeletal interface drive bone destruction in HIV-1 transgenic rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2010. 107(31): p. 13848–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Conesa-Buendia FM, et al. , Tenofovir Causes Bone Loss via Decreased Bone Formation and Increased Bone Resorption, Which Can Be Counteracted by Dipyridamole in Mice. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research, 2019. 34(5): p. 923–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carnovali M, et al. , Tenofovir and bone: age-dependent effects in a zebrafish animal model. Antivir Ther, 2016. 21(7): p. 587–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Castillo AB, et al. , Tenofovir treatment at 30 mg/kg/day can inhibit cortical bone mineralization in growing rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). J Orthop Res, 2002. 20(6): p. 1185–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Serrano S, et al. , Bone remodelling in human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected patients. A histomorphometric study. Bone, 1995. 16(2): p. 185–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ramalho J, et al. , Treatment of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection With Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate-Containing Antiretrovirals Maintains Low Bone Formation Rate, But Increases Osteoid Volume on Bone Histomorphometry. J Bone Miner Res, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Johansson H, et al. , A meta-analysis of reference markers of bone turnover for prediction of fracture. Calcif Tissue Int, 2014. 94(5): p. 560–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Garnero P, et al. , Type I collagen racemization and isomerization and the risk of fracture in postmenopausal women: the OFELY prospective study. J Bone Miner Res, 2002. 17(5): p. 826–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eastell R and Szulc P, Use of bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol, 2017. 5(11): p. 908–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ofotokun I, et al. , A Single-dose Zoledronic Acid Infusion Prevents Antiretroviral Therapy-induced Bone Loss in Treatment-naive HIV-infected Patients: A Phase IIb Trial. Clin Infect Dis, 2016. 63(5): p. 663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bolland MJ, et al. , Effects of intravenous zoledronate on bone turnover and bone density persist for at least five years in HIV-infected men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2012. 97(6): p. 1922–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Han WM, et al. , Bone mineral density changes among people living with HIV who have started with TDF-containing regimen: A five-year prospective study. PLOS ONE, 2020. 15(3): p. e0230368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Slama L, et al. , Changes in bone turnover markers with HIV seroconversion and ART initiation. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy, 2017. 72(5): p. 1456–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang L, et al. , Bone turnover and bone mineral density in HIV-1 infected Chinese taking highly active antiretroviral therapy -a prospective observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2013. 14: p. 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wattanachanya L, et al. , Antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected patients had lower bone formation markers than HIV-uninfected adults. AIDS Care, 2019: p. 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Marques de Menezes EG, et al. , Serum extracellular vesicles expressing bone activity markers associate with bone loss after HIV antiretroviral therapy. Aids, 2020. 34(3): p. 351–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oster Y, et al. , Increase in bone turnover markers in HIV patients treated with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate combined with raltegravir or efavirenz. Bone Rep, 2020. 13: p. 100727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Focà E, et al. , Prospective evaluation of bone markers, parathormone and 1,25-(OH)₂ vitamin D in HIV-positive patients after the initiation of tenofovir/emtricitabine with atazanavir/ritonavir or efavirenz. BMC Infect Dis, 2012. 12: p. 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Haskelberg H, et al. , Changes in bone turnover and bone loss in HIV-infected patients changing treatment to tenofovir-emtricitabine or abacavir-lamivudine. PLoS One, 2012. 7(6): p. e38377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stellbrink HJ, et al. , Comparison of changes in bone density and turnover with abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine in HIV-infected adults: 48-week results from the ASSERT study. Clin Infect Dis, 2010. 51(8): p. 963–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tebas P, et al. , Greater change in bone turnover markers for efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus dolutegravir + abacavir/lamivudine in antiretroviral therapy-naive adults over 144 weeks. AIDS (London, England), 2015. 29(1473–5571 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stellbrink H-J, et al. , Comparison of Changes in Bone Density and Turnover with Abacavir-Lamivudine versus Tenofovir-Emtricitabine in HIV-Infected Adults: 48-Week Results from the ASSERT Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2010. 51(8): p. 963–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bernardino JI, et al. , Bone mineral density and inflammatory and bone biomarkers after darunavir-ritonavir combined with either raltegravir or tenofovir-emtricitabine in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1: a substudy of the NEAT001/ANRS143 randomised trial. Lancet HIV, 2015. 2(11): p. e464–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cotter AG, et al. , Impact of switching from zidovudine to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate on bone mineral density and markers of bone metabolism in virologically suppressed HIV-1 infected patients; a substudy of the PREPARE study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013. 98(4): p. 1659–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Negredo E, et al. , Switching from tenofovir to abacavir in HIV-1-infected patients with low bone mineral density: changes in bone turnover markers and circulating sclerostin levels. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy, 2015. 70(7): p. 2104–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wohl DA, et al. , The ASSURE study: HIV-1 suppression is maintained with bone and renal biomarker improvement 48 weeks after ritonavir discontinuation and randomized switch to abacavir/lamivudine + atazanavir. HIV Med, 2016. 17(2): p. 106–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bloch M, et al. , Switch from tenofovir to raltegravir increases low bone mineral density and decreases markers of bone turnover over 48 weeks. HIV Med, 2014. 15(6): p. 373–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ibrahim F, Samarawickrama A, and Hamzah L, Bone mineral density, kidney function, weight gain and insulin resistance in women who switch from TDF/FTC/NNRTI to ABC/3TC/DTG. 2021. 22(2): p. 83–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Haskelberg H, Carr A, and Emery S, Bone turnover markers in HIV disease. AIDS Rev, 2011. 13(4): p. 240–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ross RD, et al. , Circulating sclerostin is associated with bone mineral density independent of HIV-serostatus. 2020. p. 100279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Erlandson KM, et al. , Plasma Sclerostin in HIV-Infected Adults on Effective Antiretroviral Therapy. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 2015. 31(7): p. 731–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Masiá M, et al. , Early changes in parathyroid hormone concentrations in HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy with tenofovir. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2012. 28(3): p. 242–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Childs KE, et al. , Short communication: Inadequate vitamin D exacerbates parathyroid hormone elevations in tenofovir users. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses, 2010. 26(8): p. 855–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Havens PL, et al. , Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate appears to disrupt the relationship of vitamin D and parathyroid hormone. Antivir Ther, 2018. 23(7): p. 623–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hsieh E and Yin MT, Continued Interest and Controversy: Vitamin D in HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep, 2018. 15(3): p. 199–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Menezes EGM, et al. , Serum extracellular vesicles expressing bone activity markers associate with bone loss after HIV antiretroviral therapy. AIDS (London, England), 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yavropoulou MP, et al. , Circulating microRNAs Related to Bone Metabolism in HIV-Associated Bone Loss. Biomedicines, 2021. 9(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lerma-Chippirraz E, et al. , Inflammation status in HIV-positive individuals correlates with changes in bone tissue quality after initiation of ART. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy, 2019. 74(5): p. 1381–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.French MA, et al. , Serum Immune Activation Markers Are Persistently Increased in Patients with HIV Infection after 6 Years of Antiretroviral Therapy despite Suppression of Viral Replication and Reconstitution of CD4+ T Cells. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2009. 200(8): p. 1212–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Guder C, et al. , Osteoimmunology: A Current Update of the Interplay Between Bone and the Immune System. Frontiers in Immunology, 2020. 11(58). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Brown TT, et al. , Changes in Bone Mineral Density After Initiation of Antiretroviral Treatment With Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine Plus Atazanavir/Ritonavir, Darunavir/Ritonavir, or Raltegravir. J Infect Dis, 2015. 212(8): p. 1241–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ofotokun I, et al. , Role of T-cell reconstitution in HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy-induced bone loss. Nature communications, 2015. 6: p. 8282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gazzola L, et al. , Association between peripheral T-Lymphocyte activation and impaired bone mineral density in HIV-infected patients. J Transl Med, 2013. 11: p. 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Manavalan JS, et al. , Abnormal Bone Acquisition With Early-Life HIV Infection: Role of Immune Activation and Senescent Osteogenic Precursors. J Bone Miner Res, 2016. 31(11): p. 1988–1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Weitzmann MN, et al. , Immune Reconstitution Bone Loss Exacerbates Bone Degeneration Due to Natural Aging in a Mouse Model. LID - jiab631 [pii] LID - 10.1093/infdis/jiab631 [doi]. (1537–6613 (Electronic)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Matuszewska A, et al. , Effects of efavirenz and tenofovir on bone tissue in Wistar rats. Adv Clin Exp Med, 2020. 29(11): p. 1265–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Conradie MM, et al. , A Direct Comparison of the Effects of the Antiretroviral Drugs Stavudine, Tenofovir and the Combination Lopinavir/Ritonavir on Bone Metabolism in a Rat Model. Calcified Tissue International, 2017. 101(4): p. 422–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Watkins ME, et al. , Development of a Novel Formulation That Improves Preclinical Bioavailability of Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate. J Pharm Sci, 2017. 106(3): p. 906–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bone architecture alterations assessed by CT aid prediction of fragility fracture. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2007. 3(7): p. 500–500. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Peacock M, et al. , Better discrimination of hip fracture using bone density, geometry and architecture. Osteoporosis International, 1995. 5(3): p. 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sheu Y, et al. , Bone strength measured by peripheral quantitative computed tomography and the risk of nonvertebral fractures: the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study. J Bone Miner Res, 2011. 26(1): p. 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Weitzmann MN, et al. , Homeostatic Expansion of CD4+ T Cells Promotes Cortical and Trabecular Bone Loss, Whereas CD8+ T Cells Induce Trabecular Bone Loss Only. J Infect Dis, 2017. 216(9): p. 1070–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Matuszewska A, et al. , Long-Term Administration of Abacavir and Etravirine Impairs Semen Quality and Alters Redox System and Bone Metabolism in Growing Male Wistar Rats. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2021. 2021: p. 5596090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Harvey NC, et al. , Trabecular bone score (TBS) as a new complementary approach for osteoporosis evaluation in clinical practice. Bone, 2015. 78: p. 216–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ciullini L, et al. , Trabecular bone score (TBS) is associated with sub-clinical vertebral fractures in HIV-infected patients. J Bone Miner Metab, 2018. 36(1): p. 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.McGinty T, et al. , Assessment of trabecular bone score, an index of bone microarchitecture, in HIV positive and HIV negative persons within the HIV UPBEAT cohort. PLoS One, 2019. 14(3): p. e0213440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kim YJ, et al. , Trabecular bone scores in young HIV-infected men: a matched case-control study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord, 2020. 21(1): p. 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sharma A, et al. , HIV Infection Is Associated With Abnormal Bone Microarchitecture: Measurement of Trabecular Bone Score in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2018. 78(4): p. 441–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Winzenrieth R, Michelet F, and Hans D, Three-dimensional (3D) microarchitecture correlations with 2D projection image gray-level variations assessed by trabecular bone score using high-resolution computed tomographic acquisitions: effects of resolution and noise. J Clin Densitom, 2013. 16(3): p. 287–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rajan R, et al. , Trabecular Bone Score-An Emerging Tool in the Management of Osteoporosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab, 2020. 24(3): p. 237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kazakia GJ, et al. , Trabecular bone microstructure is impaired in the proximal femur of human immunodeficiency virus-infected men with normal bone mineral density. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery, 2018. 8(1): p. 5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Biver E, et al. , Microstructural alterations of trabecular and cortical bone in long-term HIV-infected elderly men on successful antiretroviral therapy. Aids, 2014. 28(16): p. 2417–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Macdonald HM, et al. , Deficits in bone strength, density and microarchitecture in women living with HIV: A cross-sectional HR-pQCT study. Bone, 2020: p. 115509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Shiau S, et al. , Deficits in Bone Architecture and Strength in Children Living With HIV on Antiretroviral Therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2020. 84(1): p. 101–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Calmy A, et al. , Long-term HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy are associated with bone microstructure alterations in premenopausal women. Osteoporos Int, 2013. 24(6): p. 1843–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Yin MT, et al. , Trabecular and cortical microarchitecture in postmenopausal HIV-infected women. Calcif Tissue Int, 2013. 92(6): p. 557–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Sellier P, et al. , Disrupted trabecular bone micro-architecture in middle-aged male HIV-infected treated patients. HIV Medicine, 2016. 17(7): p. 550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Foreman SC, et al. , Factors associated with bone microstructural alterations assessed by HR-pQCT in long-term HIV-infected individuals. Bone, 2020. 133: p. 115210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Vilayphiou N, et al. , Finite element analysis performed on radius and tibia HR-pQCT images and fragility fractures at all sites in men. J Bone Miner Res, 2011. 26(5): p. 965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Wang X, et al. , Prediction of new clinical vertebral fractures in elderly men using finite element analysis of CT scans. J Bone Miner Res, 2012. 27(4): p. 808–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Guerri-Fernandez R, et al. , Bone Density, Microarchitecture, and Tissue Quality After Long-Term Treatment With Tenofovir/Emtricitabine or Abacavir/Lamivudine. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999), 2017. 75(3): p. 322–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Güerri-Fernández R, et al. , Brief Report: HIV Infection Is Associated With Worse Bone Material Properties, Independently of Bone Mineral Density. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 2016. 72(3): p. 314–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Soldado-Folgado J, et al. , Bone density, microarchitecture and tissue quality after 1 year of treatment with dolutegravir/abacavir/lamivudine. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2020. 75(10): p. 2998–3003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Pitukcheewanont P, et al. , Bone measures in HIV-1 infected children and adolescents: disparity between quantitative computed tomography and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry measurements. Osteoporosis International, 2005. 16(11): p. 1393–1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Tan DH, et al. , Novel imaging modalities for the comparison of bone microarchitecture among HIV+ patients with and without fractures: a pilot study. HIV Clin Trials, 2017. 18(1): p. 28–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Abraham AG, et al. , The combined effects of age and HIV on the anatomic distribution of cortical and cancellous bone in the femoral neck among men and women. AIDS, 2021. 35(15): p. 2513–2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Boskey AL, Bone composition: relationship to bone fragility and antiosteoporotic drug effects. Bonekey Rep, 2013. 2: p. 447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]