Abstract

Objective The objective of the study is to describe the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Lymphoedema Functioning, Disability, and Health Questionnaire for Lower Limb Lymphoedema (Lymph-ICF-LL) into (Brazilian) Portuguese.

Methods The process was comprised of five steps – translation, back translation, revision by an expert panel, pretest, and final translation. The first translation was performed by two professionals of the healthcare area, and the back translation was performed by two translators. An expert panel assessed the questions for semantics and idiomatic, cultural, and conceptual equivalence. The pretest was conducted on 10 patients with lymphedema.

Results Small differences were identified between the translated and back-translated versions, which were revised by the expert panel. The patients included in the pretest found 10 questions difficult to understand; these questions were reassessed by the same expert panel.

Conclusion The results of the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Lymph-ICF-LL resulted in a Brazilian Portuguese version, which still requires validation with various samples of the local population.

Keywords: translation, lymphedema, international classification of functioning, disability and health

Abstract

Resumo

Objetivo Descrever o processo de tradução e adaptação transcultural para o português (Brasil) do instrumento Lymphoedema Functioning, Disability and Health Questionnaire for Lower Limb Lymphoedema (Lymph-ICF-LL).

Métodos O processo foi realizado em cinco fases: tradução, retro-tradução, revisão por um comitê de especialistas, pré-teste e tradução final. A tradução inicial foi realizada por dois profissionais e a retro-tradução por dois tradutores. Um comitê de especialistas avaliou a semântica, equivalências idiomática, cultural, e conceitual das questões. Foi realizado um pré-teste em 10 pacientes com linfedema.

Resultados Durante o processo de tradução e retro-tradução, foram identificadas pequenas diferenças que foram revisadas pelo comitê. Os pacientes incluídos no pré-teste identificaram 10 questões como sendo de difícil compreensão, as quais foram reavaliadas pelo mesmo comitê de especialistas.

Conclusão Os resultados obtidos após o processo de tradução e adaptação transcultural permitiram a criação de um instrumento que necessita ser validado em diferentes populações brasileiras.

Palavras-chave: tradução, linfedema, classificação internacional de funcionalidade, incapacidade e saúde

Introduction

Lower-limb lymphedema is a frequent complication of cancer treatment.1 2 3 4 It is characterized by the reduced absorption of protein-rich interstitial fluid caused by obstruction of the lymphatic system, which mainly occurs following the removal of the lymphatic collecting vessels and lymph nodes as a result of tumor invasion, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, wound healing problems, or infection.5 6 7

Established lower-limb lymphedema is associated with considerable functional, social, and mental changes that impair the quality of life of the affected individuals.8 9 Patients with lymphedema exhibit symptoms such as swelling, feelings of heaviness, pain, and discomfort, which significantly reduce their physical functioning, mobility, and ability to perform activities of daily life. These patients also exhibit mental and emotional concerns, commonly including increased levels of anguish, feelings of helplessness, fear of the possible progression of disease, and adverse changes in body image and self-esteem.10

Complex physical therapy (CPT) is the standard treatment for lymphedema; it works by minimizing and controlling the limb volume.11 However, the functional and mental problems caused by lymphedema might persist even when therapeutic intervention is adequate.8

Accurate knowledge of human functioning (body functions, activities, and participation) and disability (impairments, activity limitations, or restrictions to participation) are essential to assess the functioning of individuals in various situations in life.12 The World Health Organization (WHO) developed the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), which describes functioning and disability related to health conditions. It assesses the function of organs and body structures as well as a person's restrictions to social participation relative to the environment where he or she lives.13 14

However, one of the main difficulties in applying ICF to clinical practice is the lack of validated instruments to measure the complexity of the processes involved in functioning and in the main disabilities associated with each particular health situation. In this regard, studies are currently aimed at identifying instruments likely to be used in the cancer care context, relative to both clinical practice and research protocols.15 16 17 18 19 20 21

This is a multicenter study involving patients with lower-limb lymphedema that sought to develop the Lymphoedema Functioning, Disability, and Health Questionnaire for Lower Limb Lymphoedema (Lymph-ICF-LL). This instrument seeks to assess problems related to functioning, such as impairments in functions, activity limitations, and restriction to participation. It exhibited satisfactory validity and reliability when it was applied to a European population.22

The aim of the present study was to translate and perform the cross-cultural adaptation of the Lymph-ICF-LL into (Brazilian) Portuguese.

Methods

The present study consisted of the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Lymph-ICF-LL. Nele Devoogdt, the first author of the original version, granted authorization for translation.22

The Lymph-ICF-LL comprises 28 questions; it was developed based on information collected from patients with primary and secondary lower-limb lymphedema. The respondents are requested to score their responses on an 11-point numerical scale (from 0 to 10). For each question, the respondents indicate the number that best describes their situation. The score ranges from “0” (zero), indicating that the patient does not have any problem related to the described complaint, to “10,” indicating that the patient has very serious problems in regard to the described complaint. The response option “non-applicable” should be selected whenever a given complaint does not apply to the respondent. The questions are distributed across three domains: physical function, mental function and mobility.22 The process of translation and adaptation of the Lymph-ICF-LL comprised 5 steps: translation, back translation, revision by an expert panel, pretest, and final translation.23 24

The initial translation from English into Portuguese was independently performed by two translators with experience in oncology and lymphology who were aware of the study aims. The two translations (T1 and T2) were merged into a single translation (T1/T2) by the main researchers. The combined version was independently back-translated into English by two translators (BT1 and BT2) who were blinded to the study aims.

The expert panel, composed of 17 professionals from three different Brazilian states (São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Paraná), was contacted via a SurveyMonkey platform and was requested to compare the two back-translated versions (BT1 and BT2) to the original version and to indicate potential flaws in translation. Thus, the first Brazilian version of the instrument (BV1) was elaborated. In this version, the response option “non-applicable” was added to all of the questions in which it was not present, and in the questions already including the option “non-applicable,” the answer option “I didn't understand this question” was added.

The BV1 was subjected to pretest on 10 individuals with lymphedema; these patients had lower-limb lymphedema secondary to cancer, without active neoplastic disease and had finished elementary school at minimum. Patients with visual or cognitive impairments that prevented them from reading and understanding the questionnaire were excluded, as were patients who were unable to walk and patients who refused to sign an informed consent form.

We collected data relative to demographic (gender, age, marital status) and clinical (date of diagnosis of lymphedema, degree of lymphedema) variables to characterize the studied population. We performed a descriptive analysis by means of measures of central tendency and variance (continuous variables) and absolute and relative frequencies (dichotomous variables). We described the scores on the BV1 as means and standard deviations (SD).

Questions that received the responses “non-applicable” or “I didn't understand this question” in the pretest were reevaluated by the expert panel for semantics (transfer of the meaning of the concepts in the original instrument's questions to the new version), idiomatic equivalence (whether idioms and colloquialisms were correctly translated), and cultural (whether the questionnaire items seek to grasp the experience of daily life) and conceptual equivalence (to analyze concepts and the meaning of words within the English and Brazilian cultural contexts).23 24 This step was also performed via a SurveyMonkey platform.

The proportion of concordance among the panel experts relative to semantics and idiomatic, cultural and conceptual equivalence was assessed by means of the content validity index (CVI) using a Likert scale (ranging from 1 to 4): 1 = item is not relevant or representative; 2 = item requires major revisions to become representative; 3 = item requires minor revisions to become representative; and 4 = item is relevant or representative. The CVI was calculated by adding the items attributed scores of 3 and 4 and dividing by the total number of responses.25 The principal researchers assessed by consensus the expert panel responses and made the final changes in the translated instrument, which was thus considered the final Brazilian translated version (BVF).

The study design complied with the regulations included in the National Health Council resolution no. 466/2012 and was approved by the research and ethics committee of the National Cancer Institute (Instituto Nacional de Câncer - INCA), Certificate of Presentation for Ethical Appraisal (Certficado de Apresentação para Apreciação Ética – CAAE) no. 35272614.0.0000.5274. All of the participants (panel experts and patients) were informed of the study aims and signed an informed consent form.

Results

The original version of the Lymph-ICF-LL was translated (T1/T2) and back-translated, and changes were made in its title and in the instructions to respondents by the expert panel (supplementary material #1). Small differences were found in some words in the translated versions after comparison to the back-translated versions, without any change in meaning. According to the expert panel evaluation, changes were made in the instructions to respondents in version T1/T2, resulting in the BV1. When there were no suggested changes, we kept the text from version T1/T2.

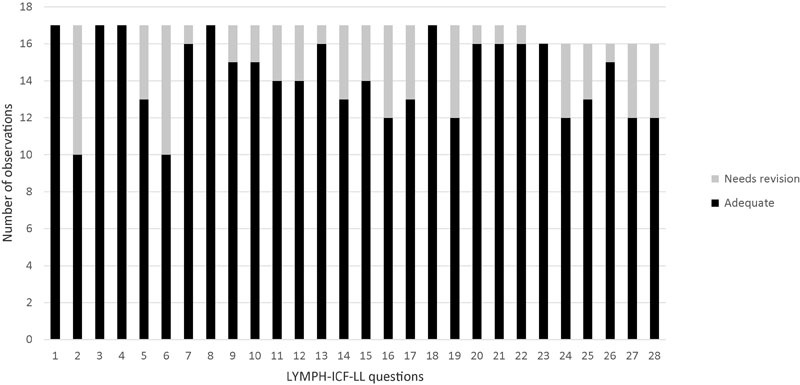

Relative to the Lymph-ICF-LL questions, the frequency of the items that required revision after evaluation by the expert panel is graphically represented in Fig. 1. Approximately 10% of the questions in the translated version (T1/T2) required changes according to the evaluation performed by the expert panel.

Fig. 1.

Expert panel's evaluation of translated version (T1/T2).

Differences between the back-translated version and the original version were found regarding some symptoms of lymphedema, which were changed by the principal researchers by consensus (supplementary material #2). These were very small changes and concerned idiomatic equivalence only.

Ten women with an average age of 54 years (SD = 12.27) were included in the pretest; 50% were married. Half of the women had lymphedema secondary to treatment for gynecological cancer, and the other half were receiving treatment for melanoma, with 20% of the women in lower limb lymphedema stage 1, 40% in stage 2, 30% in stage 3, and 10% in stage 4. Lymphedema had been diagnosed an average of 2.6 years (SD = 4.94) earlier. Ten of the questions in the Lymph-ICF-LL were rated difficult to understand, and 7 were rated as “non-applicable” (supplementary material #3).

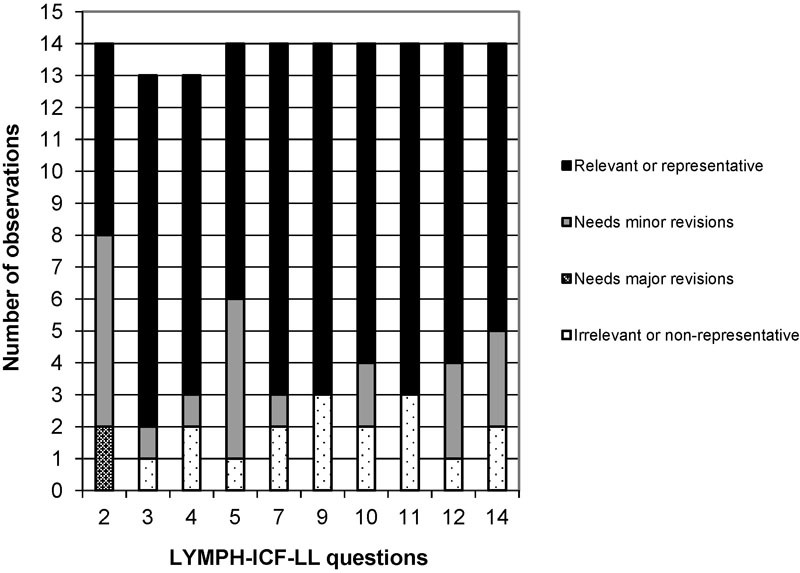

After the pretest, the expert panel only evaluated again the questions that the participants rated as difficult to understand (supplementary material #4). The panel assessed those questions based on the CVI and reported most of them as relevant and representative (Fig. 2). Five consensus questions judged relevant by the panel were revised, leading to the final Brazilian version (supplementary material #5).

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of BV1 after pretest.

Discussion

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of instruments that assess the state of health of different populations allow for a better knowledge of various cultures; in addition, they also contribute to health public policies.12

Cross-cultural adaptation is a necessary methodology that aims to achieve equivalence between the original and other languages. Thus, both translation and cross-cultural adaptation must maintain content validity of the instrument in the different languages.26

The translated versions, T1 and T2, of the Lymph-ICF-LL title and instructions to respondents were similar, and no changes were required upon merging them into the single version, T1/T2. This was not the case for the back translation, which exhibited small differences in referential meaning, particularly in the case of the questions related to the symptoms of lymphedema; however, the back translation did not display any loss in general meaning.

According to another author,27 these results show that as a rule, the problems become manifest when back-translating a sentence into the original language. For that reason, the performance of two independent translations is important because it broadens the scope of options for the elaboration of a new version of the translated questionnaire.

The BV1 of the title and questions required changing the text of ∼10% of the questions because of problems in their idiomatic equivalence. After the pretest, the participants rated 10 questions as difficult to understand; these questions were reassessed by the expert panel, and 5 of the questions were revised and modified by the main researchers by consensus. Once the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation was complete, the results of the assessment of the questionnaire semantics and idiomatic, cultural, and conceptual equivalence enabled the creation of an instrument that requires validation in different Brazilian populations.

The present study has several limitations; the main limitation results from the inclusion of patients with lymphedema secondary to cancer treatment only. To minimize such bias, we selected the specialists involved from different Brazilian areas, but all of the specialists had considerable experience in the care of patients with lymphedema by various causes. Nevertheless, it is recommended to apply the questionnaire to Brazilian patients with lower-limb lymphedema by different causes to establish its reliability and validity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the expert panel for their significant contributions to the present study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Deura I, Shimada M, Hirashita K. et al. Incidence and risk factors for lower limb lymphedema after gynecologic cancer surgery with initiation of periodic complex decongestive physiotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015;20(3):556–560. doi: 10.1007/s10147-014-0724-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beesley V L, Rowlands I J, Hayes S C. et al. Incidence, risk factors and estimates of a woman's risk of developing secondary lower limb lymphedema and lymphedema-specific supportive care needs in women treated for endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyngstrom J R, Chiang Y J, Cromwell K D. et al. Prospective assessment of lymphedema incidence and lymphedema-associated symptoms following lymph node surgery for melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2013;23(4):290–297. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e3283632c83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campanholi L L, Duprat Neto J P, Fregnani J H. Mathematical model to predict risk for lymphoedema after treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Int J Surg. 2011;9(4):306–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernas M. Assessment and risk reduction in lymphedema. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2013;29(1):12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohba Y, Todo Y, Kobayashi N. et al. Risk factors for lower-limb lymphedema after surgery for cervical cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2011;16(3):238–243. doi: 10.1007/s10147-010-0171-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graf N, Rufibach K, Schmidt A M, Fehr M, Fink D, Baege A C. Frequency and risk factors of lower limb lymphedema following lymphadenectomy in patients with gynecological malignancies. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2013;34(1):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yost K J Cheville A L Al-Hilli M M et al. Lymphedema after surgery for endometrial cancer: prevalence, risk factors, and quality of life Obstet Gynecol 2014124(2 Pt 1):307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowlands I J, Beesley V L, Janda M. et al. Quality of life of women with lower limb swelling or lymphedema 3-5 years following endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;133(2):314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finnane A, Hayes S C, Obermair A, Janda M. Quality of life of women with lower-limb lymphedema following gynecological cancer. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2011;11(3):287–297. doi: 10.1586/erp.11.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Society of Lymphology . The diagnosis and treatment of peripheral lymphedema: 2013 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology. 2013;46(1):1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silveira C, Parpinelli M A, Pacagnella R C. et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS 2.0) into Portuguese. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2013;59(3):234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ramb.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farias N, Buchalla C M. A Classificação Internacional de Funcionalidade, Incapacidade e Saúde da Organização Mundial da Saúde: conceitos, usos e perspectivas. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2005;8(2):187–193. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castaneda L, Bergmann A, Bahia L. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: a systematic review of observational studies. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2014;17(2):437–451. doi: 10.1590/1809-4503201400020012eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carvalho F N, Koifman R J, Bergmann A. International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health in women with breast cancer: a proposal for measurement instruments. Cad Saude Publica. 2013;29(6):1083–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nascimento de Carvalho F, Bergmann A, Koifman R J. Functionality in women with breast cancer: the use of International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) in clinical practice. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26(5):721–730. doi: 10.1589/jpts.26.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darcy L, Enskär K, Granlund M, Simeonsson R J, Peterson C, Björk M. Health and functioning in the everyday lives of young children with cancer: documenting with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health—Children and Youth (ICF-CY) Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(3):475–482. doi: 10.1111/cch.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nund R L, Scarinci N A, Cartmill B, Ward E C, Kuipers P, Porceddu S V. Application of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to people with dysphagia following non-surgical head and neck cancer management. Dysphagia. 2014;29(6):692–703. doi: 10.1007/s00455-014-9563-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Roekel E H, Bours M J, de Brouwer C P. et al. The applicability of the international classification of functioning, disability, and health to study lifestyle and quality of life of colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(7):1394–1405. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khan F, Amatya B. Use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to describe patient-reported disability in primary brain tumour in an Australian community cohort. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(5):434–445. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bornbaum C C, Doyle P C, Skarakis-Doyle E, Theurer J A. A critical exploration of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) framework from the perspective of oncology: recommendations for revision. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:75–86. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S40020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devoogdt N, De Groef A, Hendrickx A. et al. Lymphoedema Functioning, Disability and Health Questionnaire for Lower Limb Lymphoedema (Lymph-ICF-LL): reliability and validity. Phys Ther. 2014;94(5):705–721. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D. Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(12):1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaton D E, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz M B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25(24):3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexandre N MC, Coluci M ZO. Validade de conteúdo nos processos de construção e adaptação de instrumentos de medidas. Ciênc. Saúde Coletiva. 2011;16(7):3061–3068. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232011000800006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.São-João T M, Rodrigues R CM, Gallani M CBJ, Miura C TP, Domingues GdeB, Godin G. Cultural adaptation of the Brazilian version of the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire. Rev Saude Publica. 2013;47(3):479–487. doi: 10.1590/s0034-8910.2013047003947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matta S R, Luiza V L, Azeredo T B. Adaptação brasileira de questionário para avaliar a adesão terapêutica em hipertensão arterial. Rev Saude Publica. 2013;47(2):292–300. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2013047003463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]