Abstract

Purpose The aim of this study was to evaluate the health aspects of Brazilian women older than 65 years of age.

Design This was a retrospective study that included 1,001 Brazilian women cared for in the gynecological geriatric outpatient office of our institution. We report a cross-sectional analysis of female adults aged over 65 years, including data on demographics, clinical symptoms such as vasomotor symptoms, associated morbidities, physical examination and sexual intercourse. We used the chi-squared test to assess the data.

Results The age of the patients on their first clinic visit ranged from 65 to 98 years, with a mean age of 68.56 ± 4.47 years; their mean age at the time of natural menopause was 48.76 ± 5.07 years. The most frequent clinical symptoms reported during the analyzed period were hot flashes (n = 188), followed by arthropathy, asthenia, and dry vagina. The most frequent associated morbidities after 65 years of age were systemic arterial hypertension, gastrointestinal disturbance, diabetes mellitus, and depression, among others. The assessment of the body mass index (BMI) found decreases in BMI with increased age. At the time of the visit, 78 patients reported sexual intercourse. The majority of women reporting sexual intercourse (89.75%, n = 70) were between 65 and 69 years of age, 8.97% (n = 7) were between 70 and 74 years of age, and only 1.28% (n = 1) of those were aged older than 75 years.

Conclusions Our findings suggested that vasomotor symptoms can persist after 65 years of age. There was a significant decrease in sexual intercourse with increased age. The cardiovascular disturbances in our study are health concerns in these women.

Keywords: aging, menopause, vasomotor symptoms, body mass index, sexual intercourse

Abstract

Resumo

Objetivo Avaliar os aspectos de saúde das mulheres brasileiras após os 65 anos de idade.

Métodos O estudo foi retrospectivo, e incluiu 1.001 mulheres brasileiras atendidas no ambulatório de ginecologia geriátrica de nossa instituição. Foi feita uma análise transversal de mulheres com idade acima de 65 anos, incluindo dados demográficos, sintomas clínicos (sintomas vasomotores), morbidades associadas, bem como alterações no exame físico e queixas em relação à atividade sexual. Utilizamos o teste qui-quadrado para avaliar os dados.

Resultados A idade das pacientes na primeira visita clínica variou de 65 a 98 anos, com média etária de 68,56 ± 4,47 anos. A média etária de entrada na menopausa foi de 48,76 ± 5,07 anos. Os sintomas clínicos mais frequentes relatados durante o período analisado foram os sintomas vasomotores (n = 188), seguidos de artropatia, astenia e vagina seca. As morbidades associadas mais frequentes após os 65 anos foram hipertensão arterial sistêmica, distúrbios gastrintestinais, diabete melito e depressão, entre outras. A avaliação do índice de massa corporal (IMC) mostrou redução deste parâmetro antropométrico com o progredir da idade. No momento da visita, 78 pacientes relataram ter relações sexuais. A maioria das mulheres que relatou ter relações sexuais (89,75%, n = 70) estava entre 65 e 69 anos, 8,97% (n = 7) tinham entre 70 e 74 anos, e apenas 1,28% (n = 1) eram mais velhas do que 75 anos de idade.

Conclusões Nossos achados sugerem que os sintomas vasomotores podem persistir após os 65 anos. Houve uma diminuição significativa na relação sexual com o aumento da idade. Os distúrbios cardiovasculares em nosso estudo são preocupações de saúde nestas mulheres.

Palavras-chave: envelhecimento, menopausa, sintomas vasomotores, índice de massa corporal, atividade sexual

Introduction

In 2002, the projections of the United Nations World Populations Prospects showed that in 2000 there were 600 million people in the global population older than 60 years of age, and estimated that number would double by 2015, reaching to 2 billion individuals by 2050. According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE, in the Portuguese acronym), the life expectancy at birth in Brazil has jumped from 42.7 years for those born in the 1930s to 74.8 years in 2014, a level that is similar to countries like the Dominican Republic and Nicaragua, which is low compared with developed countries. Moreover, data on Brazilian women older than 65 years of age are scarce, and the teaching hospital of our institution cares for patients from all five regions of the country. Therefore, all data may be of interest in order to understand the health aspects of women older than 65 years age.1 2 3

Some investigators described the disturbance in the quality of health in patients older than 65 years,4 particularly due to cardiovascular disease and depression, which may limit the physical activity and contribute to reclusion from society and avoidance of medical consultations, which might aggravate these diseases. In addition, other factors such as race, education, culture, and feeding aspects may explain the disturbances in the wellbeing of women in this period of life. However, few data regarding menopausal symptoms and sexual intercourse have been reported in the Brazilian population in this age group.4 5 6 In fact, those factors may also influence the quality of life. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the health aspects, as well as the gynecologic disturbances and sexual intercourse of Brazilian women older than 65 years without any previous gynecological treatment.

Patients and Methods

Study Participants

The protocol of this study was designed with a specific questionnaire and patient chart of the included patients who came to the gynecological screening.

This retrospective study initially included 1,325 Brazilian women older than 65 years who visited the gynecologic geriatric outpatient office of our institution from 1983 to 2010. Data were obtained from their medical records.

Eligibility Criteria

In order to be included, the patients had to be older than 65 years of age and have enough chart data for the analysis of the study variables. We excluded patients who had a surgically induced menopause (ovariectomy or/and hysterectomy) or menopause before the age of 40 years, which is considered an early menopause. After applying these criteria, 1,001 women were included, with ages ranging from 65 to 98 years. These women were stratified into the following 4 groups: from 65 to 69 years; from 70 to 74; from 75 to 79; and 80 years or older. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for the Analysis of Research Projects of our institution.

Methods

Study Variables

Individual interviews were conducted to obtain data. We elaborated a questionnaire and patient chart to investigate the health aspects and the performance of sexual intercourse. The following variables were included in the present study: the patient's age at the first clinic visit; the age at natural menopause; the clinical symptoms during the analyzed period; the vasomotor symptoms, as assessed by the Kupperman Menopausal Index (KMI) and age; the personal background and its relationship with the family background; the relationship between the Quetelet index, or body mass index (BMI – weight in Kg/ height in m2), and age; the age at the time of the patient's first sexual relationship; and sexual intercourse at the time of the visit.7 8

We included data on smoking and physical activity in our interview. Regular physical activity was defined as 40 minutes of activity at least 3 times a week. The patients with cancer and the disease were controlled in our sample. The number of cases of breast cancer was too low to influence our data.

Statistical Analysis

We determined the means and standard deviations of all of the variables. We used the chi-squared test to assess the relationship between the aforementioned categorical variables; values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il, US) software, version 16.01.

Results

The regional composition of the patients at the teaching hospital seems to mirror the geographic distribution of the Brazilian population: 23.3% were form the North, 14.1% were from the Northeast, 27.5% were from the Midwest, 17.3% were from the Southeast, and 17.3% were from the South. These five macro regions together form Brazil.9 Thus, our study sample is representative of the Brazilian population. Moreover, our study included the patients invited for gynecological screening.

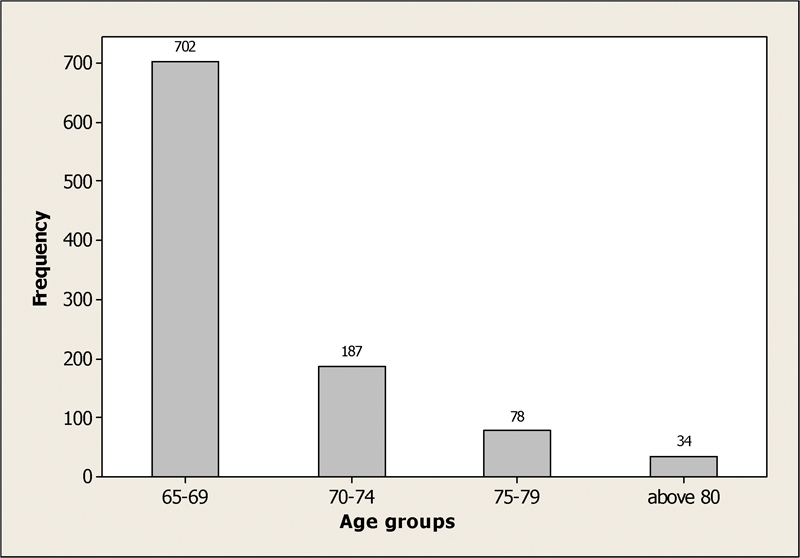

At the first clinic visit, the patients were aged between 65 to 98 years (Fig. 1); their mean age at the time of natural menopause was 48.76 ± 5.07 years. The number of patients with smoking habits was 72, and all of those patients were younger than 69 years. Not all patients reported performing regular physical activity.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the age groups at the first clinic visit (years).

Clinical Symptoms

In 910 patients, the most frequent self-reported clinical symptoms during the analyzed period were hot flashes (n = 188, 20.66%); arthropathy (n = 147, 16.15%); asthenia (n = 71, 7.80%); dry vagina (n = 57, 6.26%); urinary incontinence (n = 39, 4.29%); breast pain (n = 20, 2.20%); pelvic pain (n = 18, 1.98%); depression (n = 14, 1.54%); vertigo (n = 13, 1.48%); body pain (n = 12, 1.32%); and genital bleeding (n = 9, 0.99%) (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical symptoms.

| Clinical symptoms | Age groups (years old) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 65 to 69 | 70 to 74 | 75 to 79 | 80 or more | |||||

| n | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Hot flashes | 188 | 143 | 76.08 | 36 | 19.14 | 6 | 3.19 | 3 | 1.59 |

| Arthropathy | 147 | 88 | 59.87 | 33 | 22.44 | 21 | 14.28 | 5 | 3.41 |

| Asthenia | 71 | 57 | 80.28 | 10 | 14.08 | 2 | 2.82 | 2 | 2.82 |

| Dry vagina | 57 | 49 | 85.97 | 7 | 12.28 | 1 | 1.75 | – | – |

| Urinary incontinence | 39 | 25 | 64.11 | 7 | 17.95 | 4 | 10.25 | 3 | 7.69 |

| Breast pain | 20 | 15 | 75.00 | 2 | 10.00 | 3 | 15.00 | – | – |

| Pelvic pain | 18 | 15 | 83.34 | 2 | 11.11 | 1 | 5.55 | – | – |

| Depression | 14 | 8 | 57.15 | 6 | 42.85 | – | – | – | – |

| Vertigo | 13 | 6 | 46.16 | 4 | 30.76 | 3 | 23.08 | – | – |

| Body pain | 12 | 6 | 50.00 | 6 | 50.00 | – | – | – | – |

| Genital bleeding | 9 | 5 | 55.56 | 3 | 33.33 | 1 | 11.11 | – | – |

Note: A total of 91 patients had no clinical symptoms; the chi-squared test was applied.

Relationship between Hot Flashes by KMI and Age

As shown in Table 1, the hot flashes, which were measured by KMI, decreased over time, and older women had fewer symptoms, demonstrating the association between hot flashes and the patients' age at the first clinic visit (p = 0.001).

Personal Background and its Relationship with Family Background

The most frequent comorbidities during the analyzed period were systemic arterial hypertension (n = 500, 57.08%); gastrointestinal disturbance (n = 237, 27.02%); diabetes mellitus (n = 141, 16.02%); depression (n = 136, 15.54%); arthropathy (n = 116, 13.20%); heart problems (n = 48, 5.50%); liver diseases (n = 31, 3.53%); breast cancer (n = 28, 3.20%); stroke (n = 20, 2.29%); and deep venous thrombosis (n = 19, 2.17%; Table 2). Only arthropathy showed significant differences with age.

Table 2. Reported associated comorbidities.

| Affections | Age groups (years old) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65 to 69 | 70 to 74 | 75 to 79 | 80 or more | Total | p | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Systemic arterial hypertension | 353 | 57.87 | 90 | 52.63 | 39 | 59.09 | 18 | 62.07 | 500 | 57.08 | 0.585 |

| Gastrointestinal disturbance | 165 | 26.96 | 44 | 25.88 | 18 | 27.69 | 10 | 33.33 | 237 | 27.02 | 0.865 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 101 | 16.48 | 33 | 19.30 | 4 | 6.06 | 3 | 10.00 | 141 | 16.02 | 0.068 |

| Depression | 94 | 15.44 | 28 | 16.47 | 11 | 16.67 | 3 | 10.00 | 136 | 15.54 | 0.830 |

| Arthropathy | 63 | 10.31 | 37 | 21.51 | 7 | 10.61 | 9 | 30.00 | 116 | 13.20 | < 0.01 |

| Heart problems | 32 | 5.27 | 9 | 5.29 | 6 | 9.09 | 1 | 3.33 | 48 | 5.50 | 0.576 |

| Liver diseases | 25 | 4.08 | 4 | 2.35 | 2 | 3.03 | – | – | 31 | 3.53 | 0.503 |

| Breast cancer | 21 | 3.44 | 4 | 2.37 | 1 | 1.52 | 2 | 6.67 | 28 | 3.20 | 0.819 |

| Stroke | 12 | 1.97 | 4 | 2.37 | 3 | 4.55 | 1 | 3.33 | 20 | 2.29 | 0.927 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 10 | 1.64 | 6 | 3.55 | 3 | 4.55 | – | – | 19 | 2.17 | 0.999 |

Note: The chi-square test was applied.

This study showed that women with a family background of systemic arterial hypertension (p < 0.001), heart problems (p < 0.001), diabetes mellitus (p < 0.001), depression (p < 0.001), arthropathy (p < 0.001), breast cancer (p < 0.001), or stroke (p < 0.001) had a higher tendency of developing those diseases.

Relationship between Body Mass Index and Age

The BMI calculated during the first clinical visit in 954 women indicated that 35 (3.67%) were thin (BMI < 20); 236 (24.74%) had normal weight (BMI between 20 and 25); 376 (39.41%) were overweight (BMI between 25 and 30); 217 (22.75%) were obese (BMI between 30 and 35); and 90 (9.43%) were morbidly obese (BMI > 35; Table 3).

Table 3. Body mass index according to age groups (years).

| Body mass index | Age groups (years old) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65 to 69 | 70 to 74 | 75 or more | Total | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Thin (< 20) | 24 | 3.61 | 2 | 1.10 | 9 | 8.41 | 35 | 3.67 |

| Normal (20–25) | 159 | 23.91 | 46 | 25.27 | 31 | 28.97 | 236 | 24.74 |

| Overweight (25–30) | 245 | 36.84 | 83 | 45.61 | 48 | 44.86 | 376 | 39.41 |

| Obese (30–35) | 161 | 24.21* | 41 | 22.53 | 15 | 14.02 | 217 | 22.75 |

| Morbid obesity (> 35) | 76 | 11.43* | 10 | 5.49 | 4 | 3.74 | 90 | 9.43 |

| Total | 665 | 100.0 | 182 | 100.0 | 107 | 100.0 | 954 | 100.0 |

Notes: *p = 0.001 compared with other age intervals; the Chi-square test was applied.

When assessing the BMI across different age groups, it decreased as the age increased, showing a statistically significant difference (p = 0.001).

Sexual Intercourse

The ages at the time of the first sexual relationships for 657 women ranged from 12 years (minimum) to 49 years (maximum), with a mean age of 20.5 ± 4.85 years; at the time of the visit, 78 patients reported performing sexual intercourse regularly, and the majority of the women (n = 70, 89.75%) were between 65 and 69 years of age; 7 (8.97%) were between 70 and 74 years of age; and only 1 (1.28%) patient older than 75 years of age reported regular sexual intercourse. All of the patients who performed regular sexual intercourse had a partner. Moreover, the patients who did not perform regular intercourse reported that it was due to a health issue of their partners and psychological problems. There was a significant decrease in sexual intercourse as the age increased (p < 0.001). Additionally, the patients denied homosexual or bisexual behaviors, as well as performing masturbation.

Discussion

Knowledge of female evolution and behavior during different periods of life, mainly after 65 years of age, is important due to special clinical and psychological aspects, as well as due to the association of diseases during this period. In fact, these factors may interfere with the intensity of the symptoms related to hypoestrogenism and cause an increase in sexual disturbances.2 Our patients presented with a large number of comorbidities, and a low number of women were having sexual intercourse. Our findings may suggest that Brazilian patients older than 65 years of age have poor health.

We tried to find a cause for the high number of health disturbances in our patients. One possibility may be the age at menopause, which is a time of many changes in the psychophysical and social functioning of women, with reduced ovarian hormonal activity and estrogen levels. However, the menopausal age of our women was similar to those of other studies.10 11

Fonseca et al11 observed that older women during menopause have fewer and less intense hot flashes than younger women. However, we found that 188 women reported vasomotor symptoms during this period. We expected that a low number of patients would present with these types of symptoms. A recent systematic review of vasomotor symptoms showed that a considerable proportion of older women complained of them.12 Another study demonstrated that the hot flashes are related to emotional factors, marital and social stata, and stress.13

The associated diseases may explain this high number of patients with vasomotor symptoms: we observed a large number of women with systematic arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Those conditions may influence the cardiovascular symptoms, and may also be associated with endothelial dysfunction.10 Other causes may be psychological factors due to depression, emotional problems, or physical disturbances.14 15 16 17 18 19 In fact, we observed a large number of patients with arthropathy that may limit their physical activity and worsen their quality of life. Moreover, our data showed that not all patients performed regular physical activity. The clinical conditions of the patients with cancer and other diseases were compensated in our study. The number of smokers was too low to negatively influence our data.

In the general population, the yearly incidence of depression is ∼10 to 25%, and it occurs in different levels according to race and culture. The predisposition to develop depression in response to stress is associated with the gene sequence of the short allele of the gene encoding the serotonin transporter.14 Regardless of the mechanism, we found a high number of patients with depression, which decreases the quality of life.14 15 16 17 18

Fonseca et al11 observed that ∼ 68% of the patients were overweight or obese during the climacterium. According to Lynch et al,20 the excess weight may affect the overall health and the quality of life of women. Analyzing women older than 65 years of age in our sample, we could observe a tendency toward a decrease in BMI, which was probably due to alterations in metabolism. However, we observed a large number of diabetic patients, which is a health concern during the analyzed period of life. Additionally, McMinn et al21 reported that weight loss may increase morbidity and mortality after 65 years of age. Physiological changes related to anorexia of aging, including weight loss, bone loss, and a lower metabolic basal index, as well as taste, smell and signs of advanced gastric satiety would be responsible for the weight loss. In our study, we believe that the number of associated comorbidities may be another cause.

In the present study, only 78 women maintained sexual intercourse after 65 years of age, with the majority of these patients being between 65 and 69 years old. Different aspects, such as a drop in hormonal levels, vaginal drying, genital atrophy with pain, partners with clinical problems, fear of vascular problems and fear of meeting their partners' expectations contribute to the progressive decline in sexual activity.22 23 24 In addition, associated comorbidities, such as depression and vasomotor symptoms, may influence the sexual activity of these women after 65 years of age, as well as the health problems of their partners or problems in the marriage. Smith et al25 evaluated sexual activity in midlife women, and their study showed a high percentage of patients who do not perform sexual activity. The main reasons for this result were physical fatigue and sexual difficulties felt by the couples. In addition, the sexual function of postmenopausal women can be improved by a sexual enhancement program.26

Finally, the limitations of our study were: a) the fact that it was a retrospective study; b) the loss of data from the records; and c) no specific quality of life or sexuality questionnaire were applied. The strength of our study was the large number of patients included.

Conclusion

Our findings suggested that vasomotor symptoms can persist after 65 years of age. There was a significant decrease in sexual intercourse as the age increased. The cardiovascular disturbances in our study are health concerns. Aging in good physical and psychological conditions is not an easy task for the women and the institutions and people who are part of this process, such as their families, health professionals, social services, and government agencies. The analysis of our observations contributes to the knowledge of female aging and, consequently, to improve the quality of life of these women.

References

- 1.United Nations. [Internet]. World Populations Prospects: the 2002 revision, highlights New York: United Nations; 2003 [cited 2004 Jan 21]. (ESA/P/WP. 180). Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/wpp2002

- 2.World Health Organization. World Health Statistics Annual – Statistics of Seniors Geneva: WHO; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. População Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodrigues G H, Gebara O C, Gerbi C C, Pierri H, Wajngarten M. Depression as a clinical determinant of dependence and low quality of life in elderly patients with cardiovascular disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2015;104(06):443–449. doi: 10.5935/abc.20150034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Randolph J F, Jr, Sowers M, Gold E B et al. Reproductive hormones in the early menopausal transition: relationship to ethnicity, body size, and menopausal status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(04):1516–1522. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranzijn R, Luszcz M. Measurement of subjective quality of life of elders. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2000;50(04):263–278. doi: 10.2190/4B0W-AMGU-2NDX-CYUQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kupperman H S, Wetchler B B, Blatt M H. Contemporary therapy of the menopausal syndrome. J Am Med Assoc. 1959;171:1627–1637. doi: 10.1001/jama.1959.03010300001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quételet A. Brussels: C. Muquardt; 1870. Antropométrie ou mesure des différentes facultés de l'homme. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagnoli V R, Fonseca A M, Arie W M et al. Metabolic disorder and obesity in 5027 Brazilian postmenopausal women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2014;30(10):717–720. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2014.925869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makara-Studzińśka M T, Kryś-Noszczyk K M, Jakiel G. Epidemiology of the symptoms of menopause - an intercontinental review. Przegl Menopauz. 2014;13(03):203–211. doi: 10.5114/pm.2014.43827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Da Fonseca A M, Bagnoli V R, Souza M A et al. Impact of age and body mass on the intensity of menopausal symptoms in 5968 Brazilian women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(02):116–118. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2012.730570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zeleke B M, Davis S R, Fradkin P, Bell R J. Vasomotor symptoms and urogenital atrophy in older women: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2015;18(02):112–120. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.978754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huicochea-Gómez L, Sievert L L, Cahuich-Campos D, Brown D E. An investigation of life circumstances associated with the experience of hot flashes in Campeche, Mexico. Menopause. 2017;24(01):52–63. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vousoura E, Spyropoulou A C, Koundi K L et al. Vasomotor and depression symptoms may be associated with different sleep disturbance patterns in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22(10):1053–1057. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palacios S, Henderson V W, Siseles N, Tan D, Villaseca P. Age of menopause and impact of climacteric symptoms by geographical region. Climacteric. 2010;13(05):419–428. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2010.507886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Dam R M, Li T, Spiegelman D, Franco O H, Hu F B. Combined impact of lifestyle factors on mortality: prospective cohort study in US women. BMJ. 2008;337:a1440. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee. 2003 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension J Hypertens 200321061011–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, text revised Washington (DC)American Psychiatric Association; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coleman M P.Trends in breast cancer incidence, survival, and mortality Lancet 2000356(9229):590–591., author reply 593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch C P, McTigue K M, Bost J E et al. Excess weight and physical health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(08):1449–1458. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMinn J, Steel C, Bowman A. Investigation and management of unintentional weight loss in older adults. BMJ. 2011;342:d1732. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wellings K, Collumbien M, Slaymaker Eet al. Sexual behaviour in context: a global perspective Lancet 2006368(9548):1706–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syme M L, Cohn T J. Examining aging sexual stigma attitudes among adults by gender, age, and generational status. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(01):36–45. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1012044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeleke B M, Bell R J, Billah B, Davis S R. Vasomotor and sexual symptoms in older Australian women: a cross-sectional study. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(01):149–550. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith R L, Gallicchio L, Flaws J A. Factors affecting sexual activity in midlife women: results from the Midlife Health Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2017;26(02):103–108. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2016.5881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nazarpour S, Simbar M, Ramezani Tehrani F, Alavi Majd H. The impact of a sexual enhancement program on the sexual function of postmenopausal women. Climacteric. 2016;19(05):506–511. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2016.1219984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]