Abstract

Objective To assess whether the monomanual or bimanual training of laparoscopic suture following the same technique may interfere with the knots' performance time and/or quality.

Methods A prospective observational study involving 41 resident students of gynecology/obstetrics and general surgery who attended a laparoscopic suture training for 2 days. The participants were divided into two groups. Group A performed the training using exclusively their dominant hand, and group B performed the training using both hands to tie the intracorporeal knot. All participants followed the same technique, called Romeo Gladiator Rule. At the end of the course, the participants were asked to perform three exercises to assess the time it took them to tie the knots, as well as the quality of the knots.

Results A comparative analysis of the groups showed that there was no statistically significant difference (p = 0.334) between them regarding the length of time to tie one knot. However, when the time to tie 10 consecutive knots was compared, group A was faster than group B (p = 0.020). A comparison of the knot loosening average, in millimeters, revealed that the knots made by group B loosened less than those made by group A, but there was no statistically significant difference regarding the number of knots that became untied.

Conclusion This study demonstrated that the knots from group B showed better quality than those from group A, with lower loosening measures and more strength necessary to untie the knots. The study also demonstrated that group A was faster than B when the time to tie ten consecutive knots was compared.

Keywords: laparoscopic training, suture training

Abstract

Resumo

Objetivo O objetivo deste estudo é avaliar se o treinamento monomanual ou bimanual de sutura laparoscópica seguindo a mesma técnica pode interferir no tempo de realização e/ou qualidade dos nós.

Métodos Estudo prospectivo observacional envolvendo 41 estudantes residentes de ginecologia /obstetrícia e cirurgia geral que participaram de um treinamento de sutura laparoscópica por 2 dias. Os participantes foram divididos em dois grupos. O grupo A realizou o treinamento usando exclusivamente a mão dominante, e o grupo B realizou o treinamento usando as duas mãos para amarrar o nó intracorpóreo. Todos os participantes seguiram a mesma técnica, chamada Regra do Gladiador, descrita por Armando Romeo. No final do curso, os participantes foram convidados a realizar três exercícios para avaliar o tempo de realização e a qualidade dos nós.

Resultados Uma análise comparativa dos grupos mostrou que não houve diferença estatística significativa (p = 0,334) entre eles quanto ao período de tempo para amarrar um nó. No entanto, quando o tempo para amarrar 10 nós consecutivos foi comparado, o grupo A foi mais rápido do que o grupo B (p = 0,020). A comparação da média de afrouxamento de nó, em milímetros, revelou que os nós do grupo B afrouxaram menos do que os do grupo A, mas não houve diferença estatística significativa quanto ao número de nós que desamarraram.

Conclusão Este estudo demonstrou que os nós do grupo B apresentaram melhor qualidade do que os nós do grupo A, com menores medidas de afrouxamento e maior força necessária para desamarrar os nós. Também demonstrou que o grupo A foi mais rápido do que B quando o tempo para amarrar dez nós consecutivos foi comparado.

Palavras-chave: treinamento laparoscópico, treinamento de sutura

Introduction

The revolutionary development of minimally invasive surgery has enabled the implementation of new technologies in the medical practice with remarkable benefits in the treatment of several diseases.1 However, the pace at which these advances have been incorporated into medicine under certain circumstances was not followed by the training and qualification of novice surgeons,2 or by the improvement of evaluation methods in training programs.3

It seems appropriate that, in addition to the skills required for open surgery (manual dexterity, knowledge of anatomy and surgical techniques), the laparoscopic surgeon develops other laparoscopy-specific skills, such as depth perception in a two-dimensional screen, hand-eye coordination, bimanual coordination, the handling of long instruments that provide less tactile feedback, and, finally, the knowledge of the laparoscopic operating room.4 5

Although training in surgery is challenging, it seems obvious that a surgeon needs to have theoretical and practical knowledge and skills prior to performing a laparoscopic surgical intervention.4 6 7 8 9

Training with synthetic rubber models that mimic human tissues offers an opportunity for beginners to practice unfamiliar techniques in an artificial environment, thereby maximizing the acquisition and retention of knowledge in laparoscopy,10 and potentially leading to a decrease in errors in the operating room11 and optimizing the surgical time.12

In this context, the learning curve of laparoscopic suture is considered a challenging task; suturing is probably the most difficult skill to master in endoscopic surgery.13 14 The time required for suturing is also considered a potential obstacle in certain surgical techniques. Therefore, it is important to concentrate efforts to develop effective teaching tools to improve these skills.13 14 15

In our service, in order to meet the demand for advanced laparoscopic suture training, we developed bimanual training protocols. We recommend the use of both hands to make the intracorporeal knots following the technique called Romeo Gladiator Rule, which was described by Armando Romeo.16

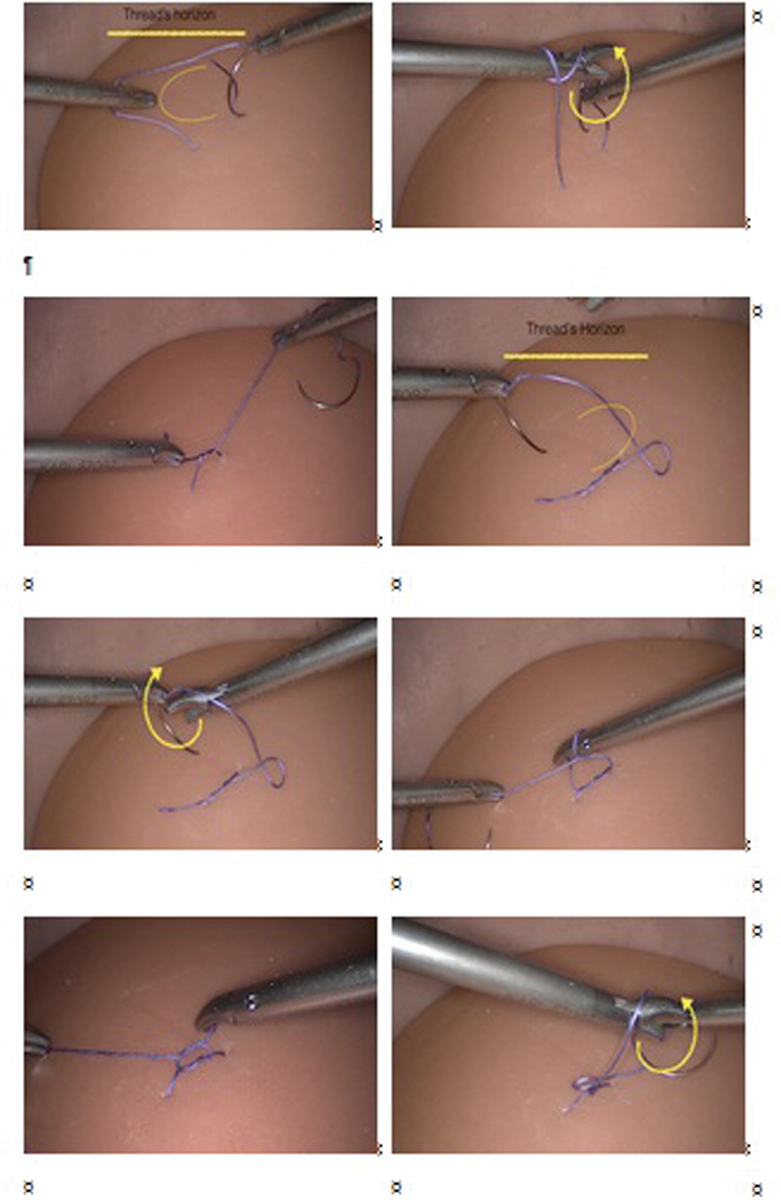

The maneuver was named Romeo Gladiator Rule because, during the knotting, the needle holder performs a clockwise turn (from 6 to 12 o'clock) or a counterclockwise turn (from 12 to 6 o'clock) with the jaws of the tip open. This maneuver resembles the pollex versus gesture made by Roman emperors to announce a verdict of condemnation or mercy to losing gladiators. The purpose of keeping the pollex versus, or the jaws of the needle holder, open is to help maintain the thread in place.16 17

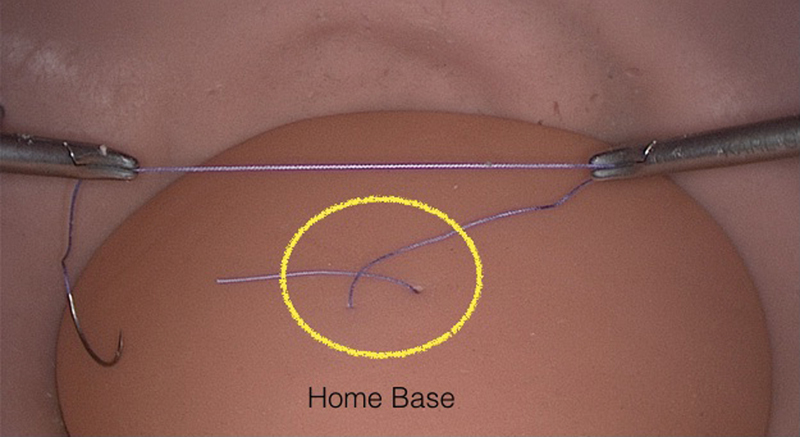

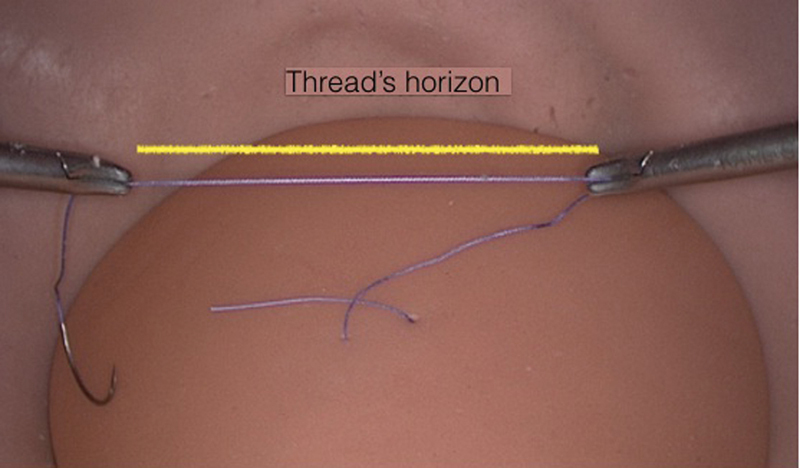

During the preparation for knot tying, there are some rules that must be followed: create two landmarks before starting the maneuver. The first reference point is the home base, which is defined as the cylindrical area where the knot is placed. In a right-handed surgeon's point of view, the assistant forceps (left hand) picks up the thread 2 cm from the needle. The second reference point is the thread horizon, which is defined as the rectilinear portion of the thread created by displacing the thread to the opposite side to the assistant forceps (Figs. 1 and 2). In the next step, the needle holder (right hand) performs a clockwise or counterclockwise turn with the jaws open, passing behind or in front of the thread horizon, depending on the blocking sequence.16 17

Fig. 1.

Home base.

Fig. 2.

Thread horizon.

The aim of this study is to assess whether the training in laparoscopic suture with the exclusive use of the dominant hand or with the use of both hands, by applying the same suturing technique (Romeo Gladiator Rule), may influence the time it takes to tie the knots, and their quality.

Methods

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Santa Casa de São Paulo. Before the beginning of the study, we explained to the participants the aim, and how it would be performed. Only the resident students who voluntarily agreed and signed the informed consent form participated in the study.

The present study was a prospective observational study conducted at Santa Casa de São Paulo; a total of 41 residents were selected for the study during 3 regular training courses on laparoscopic suture between March 2016 and July 2016. All courses were administered by the same team of teachers and instructors, and the lectures were the same in the three courses.

The inclusion criteria of the study consisted of resident students in the second and third years of gynecology/obstetrics and general surgery at Santa Casa de São Paulo without prior training in laparoscopic suture.

All students attended a two-day training course on laparoscopic suture. The course consisted of 5 hours and 30 minutes of a theoretical session, including the basic topics for beginner surgeons (ergonomics, energy and suture), and 8 hours and 30 minutes of a practical session involving hands-on training in a pelvic trainer simulator.

Romeo Gladiator Rule16 17 was used to teach intracorporeal suturing using one or both hands to perform the knot-tying technique. After the sessions, the residents were trained under the supervision of an experienced professional, also called a tutor. The participants were stratified and divided randomly into two groups at the beginning of the practical session. The stratification was based on the result of the pretest performed before the beginning of the course. Those who were able to perform the knot in the pretest were divided into groups A and B. The randomization was performed using a random number generator, and the generated numbers were stored in manila envelopes with the letters A or B written on them.

The students from group A were divided into groups of 3 residents per work station, and each work station was supervised by a tutor. In this group, the exercises proposed were performed using only one hand, meaning that Romeo Gladiator Rule was performed with the student's dominant hand.

The students from group B were also divided into groups of 3 residents per work station, and were also supervised by a tutor. In this group, the exercises were performed following the same technique, Romeo Gladiator Rule, but using both hands.

Each work station included 1 pelvic trainer (Fig. 3), which consists of a multiple-suture model connected to an all-in-one laparoscopic video system (KARL STORZ, Tuttlingen, Germany) (monitor, light source, and video camera) (Fig. 4). A central 12-mm trocar-simulating transumbilical insertion of 10 mm optics, 0 degrees (using a Hopkins Straight Forward Telescope, Karl Storz SE & Co. KG, Tuttlingen, Germany), and two 5-mm lateral trocars were introduced through the abdominal wall of the pelvic trainer with two straight handle and curve tip needle holders (KOH Macro Needle Holder, Karl Storz SE & Co. KG).

Fig. 3.

EVA II Generation ETX A1 LAP (Pro-Delphus Simuladores Cirúrgicos, Olinda, Brazil).

Fig. 4.

All-in-one video system.

First, a pre-test questionnaire was administered to obtain demographic data and information concerning the previous surgical experience, previous laparoscopic suture training, and the dominant hand.

Before the beginning of the activities, each participant had five minutes to tie a complete intracorporeal knot under the supervision of a tutor. After the randomization of the groups, we started the training, and the exercises were the same for all groups, but they maintained the specific considerations of each group. The exercise in group A was performed using the dominant hand; in group B, the same exercise was performed with both hands.

The positioning of the trocars was the same in both groups. During this step of our training program, the trocars were placed on the right and left sides of the pelvic trainer.

Training on the first day focused on learning how to perform one basic knot, the half knot, and the blocking sequence for the formation of a complete intracorporeal knot. The exercises evolved step by step with the tying of the knot following the Romeo Gladiator Rule, and each group had its respective blocking sequence.

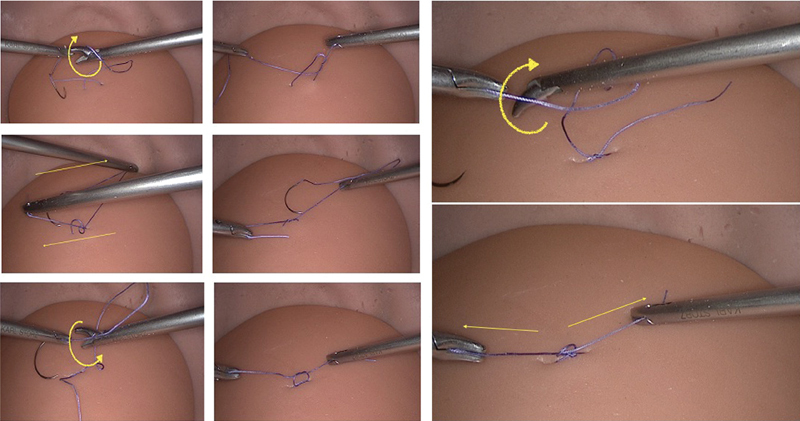

For group A, the correct blocking sequence begins with a double half knot tied with the dominant hand. For this knot to become a square double half knot, the surgeon must uncross the thread, that is, cross the instruments. This is followed by one half knot in the opposite turning direction from the prior double knot, thus forming a stable square knot. To ensure the complete blocking of this knot, a third half knot is made in the same direction as the initial double knot, or the opposite turning direction of the second movement ( Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Blocking sequence for group A – monomanual.

The blocking sequence for group B follows other characteristics: it begins with a double half knot with the opposite hand passing the thread in the tissue. The thread horizon takes a different position, and is opposite to the tail of the thread (Fig. 6). At the end of the knot, it is not necessary to uncross the threads or cross the instruments. This is followed by one half knot with the opposite hand with a turning movement in the same direction as the previous one. To block this sequence, a third half knot is made with the same hand, and in the direction of the first double knot (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Blocking sequence for group B – bimanual.

On the second day, the training started with correct needle positioning exercises, followed by the correct passage of the needle in the tissue by conducting exercises about running sutures and always respecting the differences between groups A and B.

At the end of the course, the participants performed three exercises that assessed the length of time to tie the knots and their quality. The parameters evaluated in the final test were the time it took to to tie a complete intracorporeal knot, the time it took to tie 10 consecutive half knots, the number of complete knots tied in 10 minutes, and an evaluation of the quality of the knots by the measurement of knot loosening in millimeters using strength to open it.

Each exercise began when the tutor gave a signal, and ended when the resident finished the knot, or when the predetermined time expired. Each tutor used a timer to record the time required to perform each exercise. The resident was not allowed to receive help, information, or corrections. The exercises were performed under the supervision of a master tutor.

The final test was based on three different exercises:

Exercise 1: Measurement of the time it took to tie a complete intracorporeal knot. Each participant had three chances to tie the complete knot, and an average of the time it took to tie each knot was calculated. The timer was started with the visualization of the two needle holders centralized in the monitor and after the passage of the thread and the needle, which was performed by the tutor of each table. This passage was made with the right hand.

Suture thread used: polyglactin 2–0, with a standard size of 18 cm.

Exercise 2: Measurement of the time it took to tie 10 consecutive half knots with the same thread without cutting, thus obtaining a final result similar to a braid. The passage of the needle was also performed by the tutor of each table, always with the right hand.

Suture thread used: polyglactin 2–0, with a standard size of 18 cm.

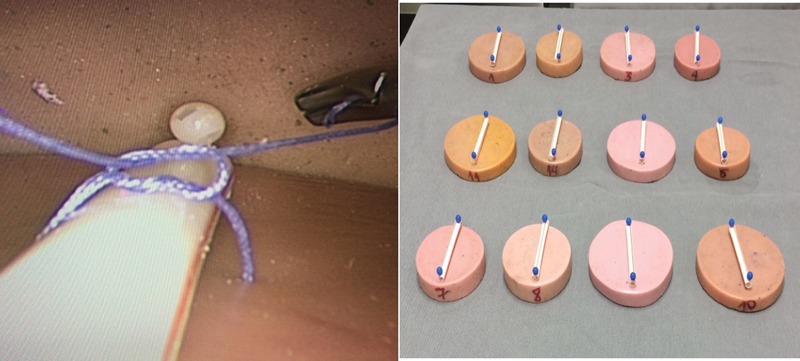

Exercise 3: Numbers of complete knots performed in 10 minutes on a fixed straw in a flat mold. The time was recorded only for the tying of the knot made by the participant; the timer was paused when the student cut the thread, and was restarted after the thread and needle were passed by the tutor with the right hand. Therefore, the tutor's work was not considered in the total time. Later, the straw was removed, thus enabling the evaluation of the quality of the knots.

Materials used: suture thread - polyglactin 2–0, with a standard size of 25 cm (up to 5 threads per participant); one 6-cm straw; and 2 pins to fix the straw in the flat mold (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Flat mold with straw fixed.

The evaluation of the quality of the knots was performed with the assistance of two engineers the day after at the engineering laboratory of the Brazilian headquarters of the company called Medtronic. The suture molds were sent to the laboratory with the straw fixed, which was removed at the knot evaluation.

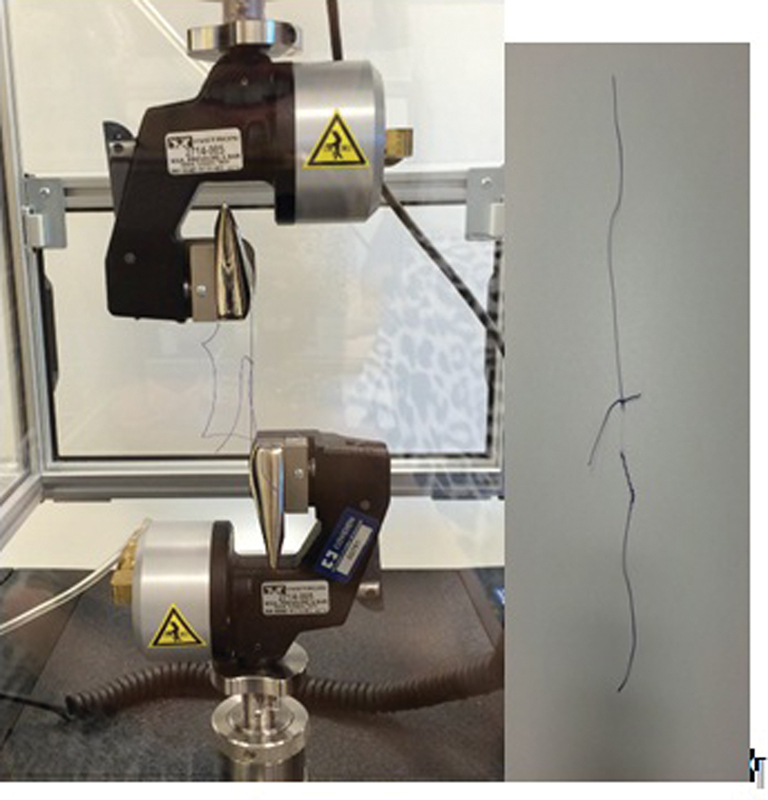

First, we evaluated the quality of the thread (polyglactin 2–0) used in the tests. One knot was made following the principles of the blocking sequence, and the thread was cut in equal lengths from both sides of the knot. To evaluate the force required to break the thread, it was placed in a dynamometer machine (Universal Testing Machine 5965, Instron, Norwwod, MA, US) and submitted to equivalent force traction in each extremity until the thread broke (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Evaluation of the quality of the thread and thread breaks.

The maximum breaking strength of the thread was of 18 newtons (N), and the breaking occurred at the level of the knot, the site of the greatest friction and fragility.

Based on this value of rupture strength (18 N), we chose a force value of 17 N because our objective was to evaluate how much the knot loosens before the thread breaks.

The quality of the knots was evaluated using a caliper rule or pachymeter (Kingtools, SP, Brazil) and dynamometer. First, we measured the length of the edges of the knot with a pachymeter after the knot was submitted to traction with the dynamometer up to a force of 17 N, and then, the length of the knot edges was measured again. The difference between the length of the edges pre- and posttraction was evaluated to obtain a measurement of knot loosening in millimeters (mm).

For the sample size calculation, we conducted a pilot study with twelve doctors participating in a regular training course on laparoscopic suture offered by our department. They were divided in two groups (monomanual and bimanual), and submitted to the same methodology of training as previously described. Two exercises were used as the standard to calculate the sample size: a) the amount of time needed to tie a complete intracorporeal knot; and b) measurement of the knot loosening in millimeters. Using the data obtained in this pilot study, applying a bicaudal test with a significance level of 95% and a power of 80%, the suggested sample size was 20 subjects in each group.

The statistical analysis of all the collected information was initially performed in a descriptive way.

In the present study, none of the variables followed a normal distribution; therefore, we opted for data evaluation of the application of non-parametric tests. Variables with non-normal distribution were expressed as medians (minimum-maximum variation).

The Fisher exact test was used to compare the qualitative variables, and the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the non-parametric continuous variables of the two groups. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the non-parametric continuous variables pre- and post-training. For the inferential analysis, the significance level α was equal to 5%. The statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, US), version 18.0 for Windows.

Results

The 41 participants who took part in this study were divided into group A (dominant hand, with 21 participants) and group B (bimanual, with 20 participants). A total of 21 participants were gynecology/obstetrics (GO) residents, and 20 were general surgery (GS) residents. The average age of the study population was 27 years and 3 months, ranging from 25 to 30 years of age. Of the total, 14 participants were men (34.1%) and 27 were women (65.9%). Only 3 (7.3%) participants reported the left hand as preferred for the surgical practice.

All participants were subjected to a pretest, and 22 (53.7%) of them were able to tie 1 knot in up to 5 minutes. A total of 5 (12.2%) participants performed the blocking sequence correctly, and all participants used only the dominant hand.

Confirming the homogeneity of the sample, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups with regards to the controlling variables: gender, dominant hand, medical residency, and pretest knot performance (Table 1).

Table 1. Control variables between the groups of individuals submitted to monomanual (group A) and bimanual (group B) laparoscopic suture training.

| Group | A | B | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Gender | Female | 17 (81) | 10 (50) | 0.078 |

| Male | 4 (19) | 10 (50) | ||

| Dominant Hand | Right | 19 (90.5) | 19 (95) | 1.000 |

| Left | 2 (9.5) | 1 (5) | ||

| Specialty of the medical Student | Gynecology/obstetrics | 10 (47.6) | 11(55) | 0.873 |

| General surgery | 11 (52.4) | 9 (45) | ||

| Pretest | No | 12 (57.1) | 7 (35) | 0.268 |

| Yes | 9 (42.9) | 13 (65) | ||

A comparative analysis of the groups showed that there was no statistically significant difference between the groups when the time to tie one knot was compared.

Similarly, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups when comparing the number of complete knots tied in 10 minutes (Table 2).

Table 2. Comparative analysis between groups of individuals undergoing monomanual (group A) and bimanual (group B) laparoscopic suture training.

| Group | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time it took to tie a complete intracorporeal knot | A | 107.0 (43.2) | 94.7 (199.3) | 0.334 |

| B | 118.3 (51.2) | 112.7 (223.7) | ||

| Time it took to tie 10 consecutive half knots | A | 225.5 (91.4) | 188.0 (310) | 0.020 |

| B | 289.7 (99.4) | 289.5 (363) | ||

| Number of complete knots tied in 10 minutes | A | 4.71 (1.74) n = 99 |

5 (7) | 0.354 |

| B | 4.25 (1.94) n = 85 |

4 (7) | ||

| Numbers of knots that became untied | A | 1.43 (1.12) n = 30 |

1 (3) | 0.448 |

| B | 1.15 (0.99) n = 23 |

1 (3) | ||

| Knot loosening average in millimeters | A | 3.27 (1.37) | 3.53 (5.5) | 0.011 |

| B | 2.36 (1.44) | 2.1 (6.77) | ||

| Force (N) required to open the knots | A | 6.5 (4.7) | 5.1 (15.2) | 0.001 |

| B | 11.5 (4.8) | 14 (14) | ||

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; N, newtons.

The amount of time to tie 10 consecutive knots was shorter in group A than in group B (225.5 s and 289.7 s respectively; Table 2).

A statistically significant difference was also identified when comparing the knot loosening average in mm; group A had an average of 3.27 mm of loosening, and group B, 2.36 mm. Thus, as a result, the knots made by group B loosened less than those made by group A (Table 2), but there was no statistically significant difference between both groups regarding the number of knots that became untied. The force required to untie the knots was significantly higher in group B, with a median of 14 N, than in group A, with a median of 5.1 N (Table 2).

After the end of the course and evaluation, all participants answered a posttest questionnaire about the training. All the participants considered the training outcome positive; 36 participants (87.8%) reported a positive change in surgical motivation with the training, and 40 out of the 41 participants (97.6%) agreed that simulation training sessions should be part of the resident's curriculum.

Discussion

The results observed in the present study emphasize the importance of training in the learning curve of surgeons. Prior to the course, 22 participants (53.7%) could perform an intracorporeal knot in up to 5 minutes, and at the end of the training, all of them were able to perform it. Among the individuals who tied the knot, in both groups there was a significant improvement in the amount of time it took them to tie the knot after training. The average time to perform this exercise in the pre-test was of 205.25 s, and after the end of the course, the time was halved: 102.4 seconds. Similarly, after supervised training, the participants who could not tie the knot in the pretest achieved a result similar to the participants who had tied the knot in the pretest, thereby confirming the relevance of the training.

A comparative analysis of the groups showed no statistically significant difference between the groups when comparing the amount of time it took them to tie one knot. However, when the amount of time taken to tie 10 consecutive knots was compared, group A was faster than group B. This result may suggest that for operations that require a greater number of sutures, such as surgery for myomectomy, it would be advantageous to opt to suture with the dominant hand, tying as much knots as possible in a single period of time, and taking into consideration the quality of the knots, in order to avoid unexpected bleeding. Since the time it takes to perform the suturing of the myometrial defect is described as the main factor that influences intraoperative uterine bleeding, this is a result of the length of time that the myometrium remains open. Therefore, the reduction in blood loss depends on a fast and efficient suture, and this implies that suturing with adequate tension and hemostasis at the time of surgery is fundamental to the success of the patient's recovery.18 19

However, for surgeries that require fewer sutures, suturing with the dominant hand or with both hands does not make a difference in terms of time in the initial phase of the learning curve, and this is because continuous practice can make the groups' time to tie multiple knots match.

No statistically significant difference was observed between the groups regarding the number of knots that became untied, but the results drew attention to the quality of the knots that were tied even after supervised training. The number of knots tied by the dominant hand group and the bimanual group was 184, and, of these, 53 knots became untied, that is, 28.8% of the sutures were performed with poor quality. The application of this data in the surgical practice was not evaluated, but there is a possibility of an increase in intraoperative and postoperative complications.

Another key point observed in the results was the measurement in millimeters of the knot loosening average, which lead us to affirm that the knots tied bimanually had loosened less than those tied using the dominant hand alone. In addition, the median strength in newtons required for the knot to become untied was significantly lower in the dominant hand group (5.1 N) than in the bimanual group (14 N); therefore, the knot made with the dominant hand became untied more easily than the knot made with both hands. The strength needed to break the thread used in our study was of 18 N; thus, the median force needed to untie the knots of the bimanual group was very close to the breaking strength of the thread.

It is possible that crossing the instruments to uncross the threads during the suturing technique with one hand can lead to instability of the square knot if the surgeon pulls more to one side, that is, if the surgeon does not apply symmetrical forces at the ends of the thread, as this will compromise the blocking sequence.

In addition, the knot made with both hands was tied by alternating the hands and maintaining the same direction of the Romeo Gladiator Rule movement. This is another fact that suggests greater confidence, because unconsciously we choose to perform simple and repeatable movements that are less difficult. Therefore, maintaining the same direction ensures that we instinctively maintain the easier direction to perform the movement, which will be the same as before.

No statistically significant difference was observed between the groups regarding the number of knots that became untied, but a loosened knot is not as effective, and can lead to postoperative complications, with different impacts on the health and recovery of the patient.

The clinical application of this finding was not tested; however, according to practice and experiences, knot loosening may make sutures ineffective, causing complications and bleeding. Considering the suture of the vaginal cuff in a total hysterectomy, if there is some looseness in the suture, not only bleeding may occur, but also dehiscence of the vaginal cuff in the postoperative period, leading to complications and causing discomfort to the patient.

The results of the present study confirm the literature findings regarding the efficacy of the pelvic trainer simulator for the improvement of laparoscopic skills and abilities,13 20 21 among them psychomotor control and spatial orientation, which are fundamental for the practice of laparoscopic suture,22 and also demonstrate the difficulty in achieving such proficiency.

Achieving proficiency in laparoscopic suture is of extreme importance for surgeons, especially gynecologists, because it is a fundamental step for the most common procedures in their daily practice, such as hysterectomy and myomectomy.22 23 The good quality of the suture is fundamental for the success of the postoperative result, with a lower rate of complications. This is corroborated by studies that demonstrate a lower rate of surgical complications according to the surgical technique used and previous training.23 24

It is also important to stress that the data herein demonstrated reflects specifically the studied population in a specific condition of knowledge and training. Although we personally agree that the bimanual knot tying technique seems safer and may be faster, it could be true that with a longer training or larger sample size this concept would change. Another weak point of our study is related to the studied population: would the results be the same were this study conducted among experts or surgeons with at least 40 surgeries performed, as required by the Brazilian Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Associations (Febrasgo, in the Portuguese acronym) in order for one to become a specialist in gynecological endoscopy? Can the experience of a surgeon correct a tendency to neglect the correct blocking sequence in a monomanual knot tying procedure?

In the present study, the interference of the studied forms of knot tying (monomanual or bimanual) in the clinical practice, dealing with living tissue in an actual surgery, was not tested. In order to complement the data obtained from the present study, the clinical applicability of these results should be tested. Today we can compare this study to some literature findings regarding the knot tying time; however, there are no studies associating the quality of the knots with intra- and postoperative incidents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the knots from the bimanual group showed better quality than those from the dominant hand group, with lower loosening measured in millimeters and more strength required to untie the knots. The group using the dominant hand was faster than the bimanual group when the amounts of time it took them to tie 10 consecutive knots were compared. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups when comparing the amount of time it took to tie one knot. Further studies will be needed to confirm our findings in other medical communities, and to broaden the horizons of didactic knowledge in video surgery.

Conflicts to Interest The authors have none to declare.

Contributions

Asencio FA, Ribeiro HASA, Romeo A, Wattiez A and Ribeiro PAGA contributed with the project and the interpretation of data, the writing of the article, the critical review of the intellectual content, and the final approval of the version to be published.

References

- 1.Adrales G L, Chu U B, Hoskins J D, Witzke D B, Park A E.Development of a valid, cost-effective laparoscopic training program Am J Surg 200418702157–163.. Doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peracchia A. Presidential Address: Surgical education in the third millennium. Ann Surg. 2001;234(06):709–712. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200112000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adrales G L, Chu U B, Witzke D B et al. Evaluating minimally invasive surgery training using low-cost mechanical simulations. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(04):580–585. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campo R, Molinas C R, De Wilde R L et al. Are you good enough for your patients? The European certification model in laparoscopic surgery. Facts Views Vis ObGyn. 2012;4(02):95–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campo R, Wattiez A, Tanos Vet al. Gynaecological Endoscopic Surgical Education and Assessment. A diploma programme in gynaecological endoscopic surgery Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016199183–186.. Doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munz Y, Kumar B D, Moorthy K, Bann S, Darzi A.Laparoscopic virtual reality and box trainers: is one superior to the other? Surg Endosc 20041803485–494.. Doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-9043-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zapardiel I, Hernandez A, De Santiago J. The efficacy of robotic driven handheld instruments for the acquisition of basic laparoscopic suturing skills. Eur J Obst Gynecol. 2015;186:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castillo R, Buckel E, León Fet al. Effectiveness of learning advanced laparoscopic skills in a brief intensive laparoscopy training program J Surg Educ 20157204648–653.. Doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satava R M.Historical review of surgical simulation--a personal perspective World J Surg 20083202141–148.. Doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9374-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubrowski A, Park J, Moulton C A, Larmer J, MacRae H. A comparison of single- and multiple-stage approaches to teaching laparoscopic suturing. Am J Surg. 2007;193(02):269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bridges M, Diamond D L. The financial impact of teaching surgical residents in the operating room. Am J Surg. 1999;177(01):28–32. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen C R, Soerensen J L, Grantcharov T Pet al. Effect of virtual reality training on laparoscopic surgery: randomised controlled trial BMJ 2009338b1802. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hendrie J D, Nickel F, Bruckner Tet al. Sequential learning of psychomotor and visuospatial skills for laparoscopic suturing and knot tying - study protocol for a randomized controlled trial “The shoebox study” Trials 20161714. Doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1145-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munz Y, Almoudaris A M, Moorthy K, Dosis A, Liddle A D, Darzi A W. Curriculum-based solo virtual reality training for laparoscopic intracorporeal knot tying: objective assessment of the transfer of skill from virtual reality to reality. Am J Surg. 2007;193(06):774–783. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckley C E, Kavanagh D O, Nugent E, Ryan D, Traynor O J, Neary P C.The impact of aptitude on the learning curve for laparoscopic suturing Am J Surg 201420702263–270.. Doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liceaga A, Fernandes L F, Romeo A. Tuttlingen: Endo Press; 2013. Classification of knots in laparoscopy; pp. 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mereu L, Carri G, Albis Florez E Det al. Three-step model course to teach intracorporeal laparoscopic suturing J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2013230126–32.. Doi: 10.1089/lap.2012.0131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan C C, Lee C Y. Feasibility and safety of absorbable knotless wound closure device in laparoscopic myomectomy. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:2.849476E6. doi: 10.1155/2016/2849476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Ma D, Li X, Zhang Q.Role of barbed sutures in repairing uterine wall defects in laparoscopic myomectomy: a systemic review and meta-analysis J Minim Invasive Gynecol 20162305684–691.. Doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz R, Nadu A, Olsson L E et al. A simplified 5-step model for training laparoscopic urethrovesical anastomosis. J Urol. 2003;169(06):2041–2044. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000067384.35451.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Win G, Van Bruwaene S, De Ridder D, Miserez M.The optimal frequency of endoscopic skill labs for training and skill retention on suturing: a randomized controlled trial J Surg Educ 20137003384–393.. Doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tunitsky-Bitton E, Propst K, Muffly T.Development and validation of a laparoscopic hysterectomy cuff closure simulation model for surgical training Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016214033920–3.92E8.. Doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Escobar P A, Gressel G M, Goldberg G L, Kuo D Y. Delayed presentation of vaginal cuff dehiscence after robotic hysterectomy for gynecologic cancer: a case series and review of the literature. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2016;2016:5.296536E6. doi: 10.1155/2016/5296536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuchs Weizman N, Einarsson J I, Wang K C, Vitonis A F, Cohen S L. Vaginal cuff dehiscence: risk factors and associated morbidities. JSLS. 2015;19(02):e2013. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2013.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]