Abstract

Background:

Ninety percent of parents of pediatric oncology patients report distressing, emotionally burdensome healthcare interactions. Assuring supportive, informative treatment discussions may limit parental distress. Here, we interview parents of pediatric surgical oncology patients to better understand parental preferences for surgical counseling.

Methods:

We interviewed 10 parents of children who underwent solid tumor resection at a university-based, tertiary children’s hospital regarding their preferences for surgical discussions. Thematic content analysis of interview transcripts was performed using deductive and inductive methods.

Results:

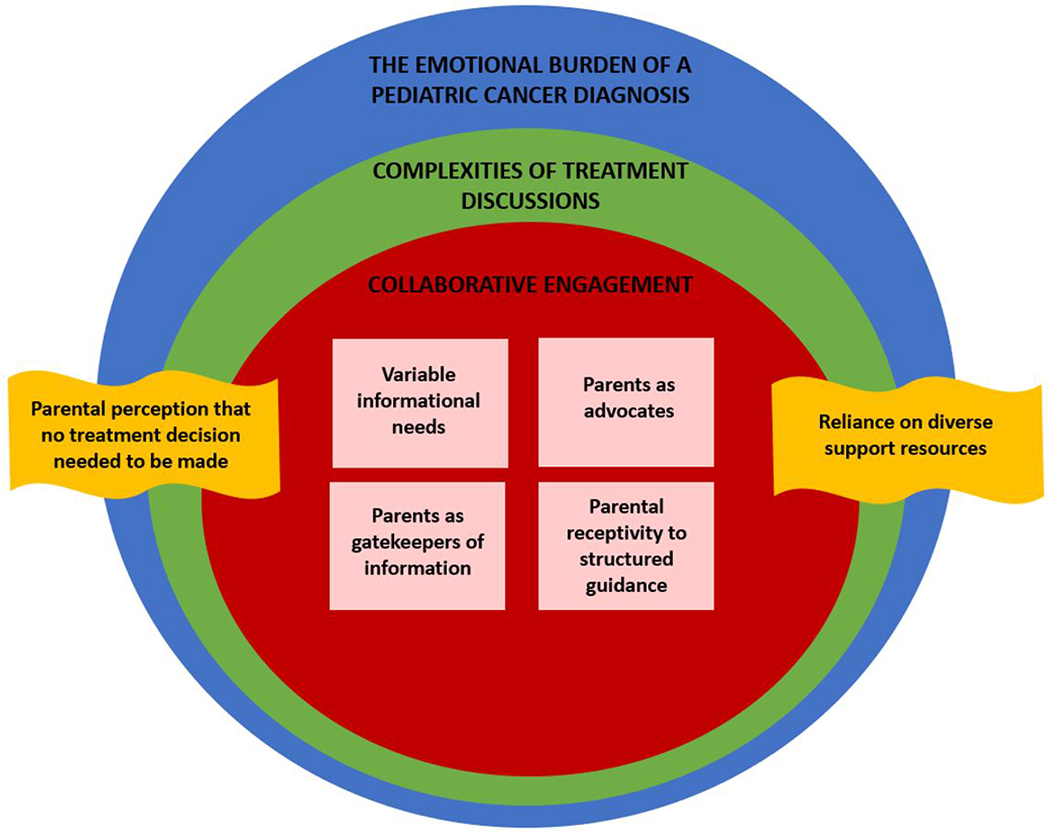

Three main themes were identified: (1) the emotional burden of a pediatric cancer diagnosis; (2) complexities of treatment discussions; (3) collaborative engagement between parents and surgeons. Within the collaborative engagement theme, there were four sub-themes: (1) variable informational needs; (2) parents as advocates; (3) parents as gatekeepers of information delivery to their children, family, friends, and community; (4) parental receptivity to structured guidance to support treatment discussions. Two cross-cutting themes were identified: (1) perception that no treatment decision needed to be made regarding surgery and (2) reliance on diverse support resources.

Conclusions:

Parents feel discussions with surgeons promote informed involvement in their child’s care, but they recognize that there may be few decisions to make regarding surgery. Even when parents perceive that there are there are no decisions to make, they prioritize asking questions to advocate for their children. The emotional burden of a cancer diagnosis often prevents parents from knowing what questions to ask. Merging this data with our prior pediatric surgeon interviews will facilitate development of a novel decision support tool that can empower parents to ask meaningful questions.

Keywords: pediatric surgery, decision making, cancer, question prompt list, collaborative engagement, parent empowerment

Introduction

Ninety percent of parents of pediatric oncology patients report significant psychologic distress and emotionally burdensome healthcare interactions [1, 2]. Parents of children with cancer have a higher prevalence of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared to parents of children without cancer [3]. Parental symptoms of anxiety and depression are most pronounced immediately following their child’s diagnosis, but these symptoms remain elevated through the first year of the child’s treatment [4]. It is estimated that as many as 30% of parents of children with recently diagnosed cancer experience moderate to severe symptoms of depression [5]. The limited data that exists surrounding the psychosocial experience of parents considering cancer surgery for their children suggests that the preoperative period is remarkably stressful [6]. Parents report feeling helpless, anxious, scared, and as if they have unmet information needs about surgery [7].

Assuring supportive, yet informative, discussions about surgery for pediatric cancer may limit parental distress during treatment discussions with their child’s surgeon [6]. This may be challenging when discussing the complex, often high-risk operations needed to treat pediatric cancer. Refining our understanding of how surgeons can best facilitate such discussions is an initial step toward promoting the psychologic wellbeing of parents. To better understand pediatric surgeon preferences for treatment discussions with parents, we interviewed pediatric surgeons regarding their preferences for discussing surgery with parents [8]. Pediatric surgeons overwhelmingly prefer a collaborative approach to counseling that engages parents through education. Surgeons prioritize tailoring discussions to meet the unique social and emotional needs of an individual parent [8]. Learning more about the specific needs of parents of pediatric surgical oncology patients will help inform surgeons on how to modify their approach to counseling for this population.

In this study, we interviewed parents of pediatric surgical oncology patients to enhance our understanding of parental preferences for surgical counseling in pediatric oncology. Insight gained from this work will guide development of a decision support tool designed to offset the emotional burden and decisional conflict experienced by parents of pediatric surgical oncology patients while empowering their participation in discussions with the surgeon.

Methods

Setting

This qualitative study was performed at a university-based, tertiary children’s hospital in the Midwestern United States. The study was approved by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board and is reported according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Appendix 1) [9].

Recruitment

We used purposive sampling to identify English-speaking parents of pediatric patients (<18 years old) who had undergone resection of a solid tumor between 2014 and 2020. Purposive sampling is a sampling technique that involves identifying individuals who are experienced with or knowledgeable about the issue being studied [10]. The criteria we selected ensured that study participants would have previously engaged in discussion about cancer surgery for their children. We identified and recruited parent participants in two ways. We conducted a retrospective chart review of our hospital’s electronic medical record as well as the Iowa Oncology Registry. We also recruited parents through our hospital’s Facebook page and Twitter feed.

Eligible parent participants were sent an initial email followed by a phone call from a member of the research team if there was no response after two weeks. Interested parents were asked to complete a brief online survey to ensure that their child met the eligibility criteria. Informed consent was obtained verbally at the commencement of each interview. Participants received a $20 Amazon gift card after completion of the interview.

Interview process

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by phone between September 25, 2019, and April 15, 2021. All interviews were conducted by an anthropologist (ML) trained in the process of semi-structured interviews. We designed an interview guide composed of main questions and probes based upon review of the literature and our prior survey data (Appendix 2). The questions built an illness narrative by asking parents to discuss their child’s medical journey as well as their own experiences during the process. The questions in the interview guide emphasized the amount of guidance and interaction parents desired and experienced from the surgeon, the amount of involvement in the decision-making process parents preferred and experienced, how much procedural detail or information regarding procedural risks was desired and received, preferred approaches for receiving information, and feelings regarding the outcome of the surgery and the surgeon. Parents were also asked about whether they thought a Question Prompt List (QPL), a structured list of questions designed to help patients ask important questions during discussions with clinicians would be a useful discussion support tool [11, 12]. The interview guide was intended to direct the conversation. However, the interview was not limited to the questions in the guide, but rather shaped by each parent’s responses. Throughout the study, questions in the interview guide were refined based upon consensus of the research team as well as concurrent iterative analysis. Interviews were digitally recorded on a secure device. Audio files were transcribed verbatim by a member of the research team and deidentified.

Data analysis

Our analysis was conducted as previously described [8]. Thematic content analysis was performed using deductive and inductive coding [13]. A codebook was developed and repeatedly refined as the research team transitioned between gathering and analyzing the data (Appendix 3). Specifically, three research team members (EC, LS, ML) independently coded interview transcripts upon completion of each interview. Team members met weekly to reach coding consensus and discuss potential refinements of the codebook. This constant comparative analysis, a process of analyzing qualitative data in which the information is coded and compared to identify patterns that can refine collection of subsequent data (i.e., modifications to the codebook based on concepts that were identified in interview transcripts), was continued until data saturation was achieved [14]. Data saturation is defined as the point at which new data are redundant of previously collected data [15, 16]. For this study, data saturation occurred when the codes identified during analysis of interview transcripts became redundant, and no new codes were identified during subsequent interview transcript analysis [16]. MAXQDA 2020 (Verbi Software, 2019) was used for data management. Quantitative results are presented only for those questions that every participant was asked.

Results

Participants

Data saturation was achieved after 10 interviews. Interview length ranged from 33-96 minutes. Patient demographics are presented in Table 1. We interviewed parents of 6 girls and 4 boys, ranging in age from 5 months to 11 years. Patients underwent surgery by pediatric general surgeons, neurosurgeons, and orthopedic surgeons.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Participant ID | Patient Gender | Patient Diagnosis | Patient Age at Tumor Resection | Surgeon Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | F | Wilms tumor | 2 years old | General |

| P2 | F | Wilms tumor | 3 years old | General |

| P3 | F | Ganglioneuroblastoma | 2 years old | General & Neurosurgery |

| P4 | F | Brain Tumor | 5 months old | Neurosurgery |

| P5 | M | Brain Tumor | 5 years old | Neurosurgery |

| P6 | F | Brain Tumor | 8 years old | Neurosurgery |

| P7 | M | Hepatoblastoma | 6 months old | General |

| P8 | F | Wilms tumor | 2 years old | General |

| P9 | M | Brain Tumor | 8 years old | Neurosurgery |

| P10 | M | Osteosarcoma | 11 years old | Orthopedic |

Main Findings

We identified three inter-connected main themes: (1) the emotional burden of a pediatric cancer diagnosis; (2) complexities of treatment discussions; and (3) collaborative engagement between parents and surgeons. Within the theme of collaborative engagement between parents and surgeons, there were four sub-themes: (1) variable informational needs; (2) parents as advocates; (3) parents as gatekeepers of information delivery to their children, family, friends, and community, and (4) parental receptivity to structured guidance to support treatment discussions. We also identified two cross-cutting themes that extended across the three main themes: (1) perception that no treatment decision needed to be made regarding surgery and (2) reliance on diverse support resources. Figure 1 outlines a thematic schema that highlights the interrelatedness of each theme. Themes did not vary based upon the age or specific diagnosis of the patient.

Figure 1.

Thematic Schema

Main theme 1: The emotional burden of a pediatric cancer diagnosis

Regardless of the type of cancer, the complexity of the recommended treatment, or the prognosis, nearly all parents interviewed described the profound emotional toll that their child’s cancer diagnosis had upon them. Parents described the cancer diagnosis as, “a tough journey” [P3], “very traumatic” [P4], “a blur” [P5], “overwhelming” [P8], “a complete shock” [P8], and “devastating news” [P9]. One parent stated, “It was a lot of shock and a lot of frustration. It was just kind of a “why me” sort of feeling, “why us,” right? Uhhh, it was tough” [P6].

Much of this emotional burden related to uncertainty about the future. One parent described this uncertainty as an inability “to come to grips with reality. Just having no idea what [the future] looked like was very scary” [P4]. Anxiety about the uncertainty of their child’s future extended far past the time of diagnosis and treatment. Many parents worried about the cancer recurring. As described by one parent, “You know, we‘re three, three and a half years out, but you always worry” [P10]. Another described “every time she gets a headache, I’ll admit, I get a little panicky, like do you think it’s a brain tumor headache or…” [P5].

A sense that cancer requires emergent intervention added to this emotional burden. As stated by one parent, “it always felt rushed regardless of how much time there was. Because the cancer was growing, right, it wasn’t getting better. So, I’ll say I felt a sense of urgency” [P8].

Many parents identified feeling helpless yet responsible for their child’s diagnosis and treatment. As stated by one parent, “you can’t do anything to fix it, but…my kid wonders why I’m doing this to them,” [P10], and another lamented, “you wish you could take their place” [P2]. For some parents, the emotional burden manifested into physical symptoms, “I just felt nauseous and sick and light-headed…just a numb feeling” [P5].

Main theme 2: Complexities of treatment discussions

Parents all emphasized the complexities surrounding decision making in pediatric surgical oncology. Several parents expressed that the amount of engagement an individual parent may desire in the decision-making process is variable, noting that it’s, “…not like a cut and dry thing. It’s kind of complicated” [P1]. Further, parents highlighted that involvement in the process does not only need to be about major decisions such as whether the surgery should be performed. Instead, parents often preferred to focus their decision-making involvement on factors surrounding the surgery, such as the institution in which the surgery will occur, or which surgeon will perform the procedure. For example, one parent noted, “And it was our decision to transfer” [P2], while another commented that, “Well right away with that MRI, we had to decide where we were going” [P5].

Some parents described significant decisional conflict when they did engage in decision making regarding the care of their children. For example, when considering whether to pursue adjuvant chemotherapy for her child, one parent describes feeling pressured by family members to try everything, “Even if it means she might get sick or it might not work, we gotta try it…. If I was the one who decided not to do it and then she ends up dying, then it’s my fault…. My husband would probably never forgive me if I didn’t try everything” [P1]. Some parents describe decisional conflict lasting for years following the initial diagnosis and treatment of their children. As one parent states, “you always wonder if, you know if he needed that amputation. If he’d still have his leg” [P10].

Parents describe that their level of regret correlates with their child’s outcome. For example, when discussing a missed finding on pre-operative imaging that could have impacted his child’s surgery, one parent states, “You know it worked out fine, so ultimately, it’s easy for me to say I don’t care, and I really don’t fault anyone for missing this. But there was evidence in retrospect that maybe it was a little more serious than anyone had noted before. So, if there was a complication because of that, then maybe my view would be different” [P8]. Another parent said: “in my head it’s done and over, that’s the direction we took. But if he didn’t have that amputation, and the cancer came back, I would feel so bad” [P10].

Parents felt like they were offered a recommendation or presented with a range of options, even if they did not feel that there was a decision to be made. Parents appreciated the recommendations, stating “I think surgeons should definitely outline all the potential options, even if one is a prominent choice or recommendation” [P6], but, “I want to know what [the surgeon] would do if it [were his her] child. That would be a big question I would want to ask” [P2]. Parents also appreciated when a recommendation was supported by all members of the healthcare team. For example, one parent commented on the importance of discussing the surgeon’s recommendation with the oncologist, stating “I know [the surgeon] wanted what was best for [my child]. His oncologist, we’d talk things over with him too, so it wasn’t like it was just one person’s opinion [P10].

Similarly, parents often solicited a second opinion about their child’s care. Second opinions ranged from clinical evaluations at other institutions to informal discussions of their child’s case with another surgeon at the same hospital. Some parents viewed the second opinion as a means to seek more options. Others expressed finding comfort in confirmation of a planned course of treatment, stating “just knowing that somebody else thought the same thing” [P2]. Other parents sought a second opinion due to concern regarding their child’s planned surgery or distrust of the surgeon. One parent commented that, “the doubt got so great at one point that we went to [another institution] to see the [surgical] group up there, which was a big burden on us in terms of more time away from work and long travel with [our child], but we did do it, and it did put things into perspective for us” [P4]. Especially when considering a rare diagnosis, parents valued knowing that their surgeons had sought input from colleagues at other institutions. One parent noted, “We didn’t reach out [for a second opinion] ourselves…it felt like we already had those second opinions from the doctors that [our surgeon] reached out to” [P3].

Main theme 3: Collaborative engagement between parents and surgeons

Parents valued engaging collaboratively with surgeons in the care of their children. When asked how they defined this collaborative engagement, parents described, “a group discussion” [P2]; feeling involved or part of the team; “every parent wants to be heard and feel like they’re helping” [P8]; “just making the guardian or the parent or the patient feel involved in the decision-making process ” [P3]; “[parents] should feel like they’re listened to, and they have some kind of a voice, even if it’s small” [P8]. Parents emphasized that it is not the magnitude of the decision being made that is important, but rather their involvement in the process, “They would involve us in the decisions of what to do next, even if it’s just what she’s going to eat” [P5].

However, parents noted that not all parents desire the same level of collaboration with the surgeon. As one parent commented, “it all depends on the person” [P1]. That is why it is so important for the surgeon to “read the room” [P8]. Thus, surgical consultation should be “a dynamic tactic, not just a single prescribed method” [P8].

Parents identified several barriers to engaging collaboratively with surgeons. They highlighted that feeling uninformed or uninvolved limited their engagement. As one parent stated, “I was a pawn in what they needed to do… I didn’t have guidance. I didn’t know I wasn’t making decisions” [P4]. Parents sometimes described feeling too overwhelmed to participate in discussions. As noted by one parent “I’m sure they showed us and went through everything, but those first few days were kind of a blur” [P7]. Another parent suggested that they could overcome feeling overwhelmed by focusing on smaller decision points as opposed to the entire spectrum of issues. This parent stated, “It had to be like in steps. Like we’re dealing with this right now. We’re dealing with that right now. Okay that might have to happen, but I cannot deal with that right now because we’re not even there yet” [P9].

Sub-theme 1: Variable informational needs

Parents prioritized developing an understanding of the diagnosis, risks, prognosis (“chance of success” [P8]), overall timeline of treatment, and planned operative interventions. How parents preferred to receive such information was variable. Some parents valued population-based statistics and discussion of outcomes data, while others appreciated application of a surgeon’s anecdotal experience to the specific situation of their child. As stated by one parent, “they can tell you, different things like the percentage of people that survived it, or that kind of thing, and we chose not to know those things. We just wanted to focus on [our child]” [P7]. As emphasized by another parent, “it was really the anecdotal information, [that] is all I wanted” [P4]. Regardless of the exact details being shared, parents preferred, “[the surgeon] be honest and straight-forward about their opinion” [P4].

Most parents highlighted the importance of in-person discussions with the surgeon. However, parental attitudes toward information adjuncts were variable. Some appreciated viewing “pictures of the tumor” [P8], while others valued printed materials and review of therapeutic protocols. One parent commented, “You know they would show us the tumor and all the organs and everything. So, I think that’s good to be able to visualize and see it” [P3]. Another highlighted, “You know immediately after the surgery, [the surgeon] met with us and he had the camera from the surgery, where they were taking pictures. He showed us what he was doing…that was also helpful to really, to figure out what he had done and then for future conversations when we talked about recovery” [P8].

Sub-theme 2: Parents as advocates

Parents emphasized the importance of advocating for their children. One parent commented, “you are the best advocate for your child. It’s not because physicians have any other intentions, but I think parents have an incredible ability to influence the quality of care that their children get and the decisions that are being made about their kids” [P6]. The need to serve as an advocate for one’s child was rationalized by one parent in that, “we like to think that everybody, every hospital professional are perfect communicators, perfect at their jobs, but just like every other human, doctors are human, and they can make mistakes. They can miscommunicate… So, for me I would like to be very much involved” [P8].

Parents described advocating for their children by independently researching their child’s diagnosis and care plan and by learning the details of the care plan and speaking up when concerns arise. Some parents described themselves as an intermediary between their child and the healthcare team and identified that it was up to them to protect their children. One parent stated, “I would like to be right in the middle of it because I wanna know what’s going on. I wanna make sure I agree, and I wanna make sure that things aren’t being missed “[P8]. When reflecting upon a time a parent thought his child’s care was being mismanaged, he notes, “I regret not acting quicker or being empowered to say you’re doing it wrong. I regret not standing up for [my child] quicker, and I have a little guilt that resides with me for not having the self-confidence to be able to stand up for him” [P4].

Parents also advocate for their children by asking questions. One parent commented that, “parents will have a lot of questions, and [surgeons] just need to take the time to answer their questions and then make them feel heard, so they feel like they can trust the people that they’re putting the child in their hands to” [P9]. Parents said that they “feel confident with what’s going to happen” [P2] when they can ask questions. They expressed frustration when they did not feel as if their questions were being answered: “I had questions, I had a lot of questions, and it almost seemed like an inconvenience [for the surgeon]” [P9].

Parents identified that they often struggled with knowing what questions to ask the surgeon. One parent highlighted, “[The surgeon] did welcome questions, but it was just the shock factor. You just don’t know what to ask” [P4]. This parent further commented “I had no idea what I didn’t know…I never really knew exactly what questions to ask… I was really frustrated because I didn’t understand the road or the possible roads ahead. We don’t know what to know because we don’t know what we don’t know. And so, it was hard to ask all the right questions up front to feel comfortable with it” [P4].

Sub-theme 3: Parents as gatekeepers of information delivery to their children, family, friends, and community

Parents described serving as gatekeepers of how and when their child’s diagnosis and need for surgery was delivered to the child, family, friends, and their community. When reflecting on how the child’s surgeon initially disclosed her child’s diagnosis, one parent remembers telling the surgeon, “If you ever have to deliver that kind of news to parents again, please make sure that the other parent is there and you’re not announcing it in front of an 8-year-old child” [P9]. Another parent notes that, “We didn’t tell [our child] what was going on. We just said oh we have to go to another hospital and see what’s going on. I mean she was in kindergarten. I didn’t want her to panic” [P5]. Another parent states, “[Our child] didn’t know he had a brain tumor that needed to be removed until 30 minutes before [the operation]. That was our decision. We just felt like he didn’t need that burden. We were gonna tell him when it was necessary” [P9]. However, parents recognize that shielding their children from their diagnoses, may become less appropriate as children age. One parent noted, “It’s different than when they’re three. They’re older…. they wanna know what’s going on. You gotta be honest with them and tell them the truth about everything” [P1]. Parents also described different approaches to communicating their child’s diagnosis to their communities. For some, community support was very helpful, however, others valued their family’s privacy. One parent highlighted, “There were people who wanted to do news stories and this and that, but you know we’ve got two other kids and just try to keep life as normal as possible. We just kind of kept to ourselves and did our thing” [P10].

Subtheme 4: Parental receptivity to structured guidance to support treatment discussions

Question Prompt Lists (QPLs) are structured lists of questions designed to help patients ask important questions during discussions with healthcare professionals [11,12]. None of the parents in this study were familiar with the phrase “question prompt list.” Some parents thought that their own record-keeping and research “would’ve gone beyond any generic prompt list that could’ve been put together” [P8]. However, all parents saw the value of a question prompt list because “when you’re in the middle of all of it, yon can’t think of everything” [P10]. One parent described the QPL as empowering, noting that “some people may not even know what to ask or feel weird asking questions. So, to give people permission basically to ask questions and give them example questions to ask so that they feel empowered and involved. I do think [the OPL] would be a powerful thing” [P8]. Overall, parents saw potential benefits of the QPL as increased comfort, decreased frustration, and decreased uncertainty. As summarized by one parent, “Because these situations can be so overwhelming you might not be thinking clearly, or questions that could be obvious to others outside the circumstance, you don’t even think of. So, I think it can help parents ask the right questions. And it would probably just give parents some comfort that they feel equipped with something. Otherwise, in these circumstances, you feel like you have no control. So, having a list you can work from gives you some sense of something you can control” [P6].

Cross-cutting theme 1: Perception that no treatment decision needed to be made regarding surgery

All parents discussed who (parent or surgeon) has decision making responsibility as well as the degree to which parents should be involved in the decision-making process. Most parents felt that they “absolutely need[ed] to be” [P5] involved in the discussion or decision-making process. However, all parents expressed feeling like there was really no decision to be made regarding the surgical care of their children. They described feeling that surgery had to be done. Parents felt, “there really wasn’t any other decision making because it was already crystal clear what needed to be done” [P5]. Surgery for their child “wasn’t really an optional type thing” [P7]. Despite parents feeling like there were no decisions to be made, they felt they could still be part of the discussion process with the surgeon. As one parent pointed out, “…I know there was a conversation, but I don’t remember it being a decision, I remember being part of the process of discussing it, but I don’t believe it was ever like our decision to make” [P8]. This parent goes on to say, “because we’d been in contact with the oncologist and the surgical team the whole time, it didn’t really feel like a decision. It felt like where the journey ended up” [P8].

Cross-cutting theme 2: Reliance on diverse support resources

Parents expressed reliance on a diverse array of support resources. They mentioned family, online resources, and faith as the resources they called upon most for support. Parents mentioned the importance of having at least one family member or friend to rely on for issues such as babysitting other children while parents were at the hospital; serving as “a sounding board” [P10]; and being confidants. Another way that parents sought support was by talking to parents that had been through similar situations. As one parent articulated, “they helped to keep our sanity a little bit” [P7]. Several parents described only being able to rely on their spouse or partner for support stating, “we make a good team together, but really, it’s just been her and I who’ve done this. We’ve not relied on anyone else for guidance” [P4].

Some parents sought support from online resources. Those parents who pursued support online typically engaged in social media or online support groups. One parent mentioned, “I have a group of Wilms parents with like 500 people on Facebook, and we all talk to each other” [P1]. This parent went on to state, “I think there’s a much bigger support [network] on the internet because you can reach people all over the world” [P1]. Alternatively, some parents expressed skepticism about seeking support online because, “that’s not a trustworthy source of information” [P8], “I didn’t wanna google too much and scare myself” [P10], and “I couldn’t handle anything negative” [P7].

Parents also expressed variable viewpoints about the role of faith in their support system. For one parent, “our church was very big in calling us and checking on us and praying with us and supporting us in that time” [P5]. For others, faith was not a component of their support system. One parent commented, “We didn’t need to take prayers…not to be dismissive of it because I know it’s very helpful to a lot of people…It just seemed so superficial and fake to us. It didn’t add any value for us” [P4].

Discussion

Our investigation of parental preferences for surgical counseling in pediatric oncology identified three main themes: the emotional burden of a pediatric cancer diagnosis, the complexities of treatment discussions, and the value of collaborative engagement between parents and surgeons. Taken together, analysis of these themes reveals that when discussing cancer surgery for their children, parents value open, collaborative discussions with surgeons. They view such discussions as a means of promoting informed involvement in their child’s care. Parents recognize that, at times, there may be few decisions to make regarding the surgical approach to their child’s care. However, even when parents perceive that there are no decisions to be made regarding surgery, they prioritize asking questions to advocate for their children. Parents emphasized the importance of deciding when and how their child’s diagnosis was disclosed to the child, family members, and the community. Parents relied on diverse support resources to manage the expressed conflict between feeling helpless yet responsible for their children’s suffering. They were receptive to structured guidance during treatment discussions and thought that this may be a means to offset some of the complexities and emotional burden associated with such discussions.

Consistent with prior studies, all the parents we interviewed emphasized the emotional burden resulting from their child’s cancer diagnosis [7]. Similar sentiments were not expressed by parents engaging in decision making regarding more elective pediatric surgical procedures [17–19]. This discrepancy highlights that for parents, discussing cancer surgery is different than discussing elective procedures. The emotionally charged nature of cancer discussions likely contributed to our prior finding that parents desired increased guidance from surgeons when discussing cancer operations for their children [20].

Intentional focus on the emotional burden of treatment discussions is critical, as it likely contributes to the high amount of post-traumatic stress parents experience following surgery for their children [21]. Such stress is even further elevated when surgery is complex or the diagnosis is life threating - such as pediatric cancer operations [21,22]. For example, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has been observed in as many as 20% of parents whose children have undergone cancer surgery - well over twice the rate of PTSD in the general population [22, 23]. Assuring adequate peri-operative parental support may offset development of PTSD following surgery.

A more nuanced understanding of parental preferences during complex treatment discussions may aid surgeons in modifying their approach to counseling to offset the emotional burdens that parents of children with cancer experience [1–3]. Inherent to each of our interviews was the finding that parents placed tremendous value on being included in discussions about the care of their children even when they felt there was no specific decision to make regarding the surgical plan. This complements our prior findings that surgeons want to engage parents in these discussions [8]. Surgeons value identifying the specific needs of the parent and modifying their approach to counseling to meet these needs [8]. The parents we interviewed recognize how such accommodation may be difficult, as different parents may have drastically different preferences for engagement and information delivery. However, assuring meaningful communication is critical, as parents who feel they have received sufficient information regarding their child’s upcoming cancer surgery report more positive peri-operative experiences [7]. The parents we interviewed highlighted the need for surgeon flexibility and responsiveness when gauging how to best engage, inform, and support parents. Assuring adequate parental support is essential for both parental wellness and the health of their children in that available data suggests that parents and children’s experiences are highly interconnected [6]. For example, parents who experience adverse psychosocial experiences preoperatively are more likely to have distressed, anxious children [6]. Further, peri-operative parental anxiety is associated with subsequent peri-procedural behavioral challenges in children that may persist for months after surgery [24, 25].

The complexity of treatment discussions is also likely to impact parental regret. Unlike parents considering circumcision, tonsillectomy, or other elective procedures, the parents we interviewed did not describe high levels of regret regarding the decision to pursue surgery for their child’s cancer [17–19]. This may stem from the decision-making responsibility parents felt when considering these more elective procedures as compared to the lack of decision-making responsibility the parents in our study reported. Perhaps this perceived lack of decision-making responsibility prevented feelings of regret [26–27]. Interestingly, several parents in our study expressed regret about “smaller” decisions they made during their child’s treatment. For example, one parent regretted not “speaking up” when he perceived his child’s care was being poorly managed. Such findings prompt one to ponder the relative value of autonomy and shared decision making in healthcare in that promotion of more decision-making autonomy or assignment of more decision-making responsibility to parents may prompt increased regret. Perhaps more directed counseling with clear recommendations from surgeons would offset parental regret in emotionally charged settings.

The parents we interviewed also described experiencing regret when outcomes were poor but not feeling regret when outcomes were favorable. This phenomenon has been described in other medical settings. For example, patients undergoing prophylactic total gastrectomy in the setting of a CDH1 gene mutation experienced regret when they did not have cancer or when they had a post operative complication but not when final pathology revealed cancer or their postoperative course was unremarkable [28]. While debate exists regarding the degree to which an individual’s decision-making agency impacts feelings of regret, there is general acceptance that people experience more regret when outcomes are negative [26].

Facilitating collaborative engagement between parents and surgeons during treatment discussions may be one way to support parents in the peri-operative setting. The parents we interviewed consistently described the importance of engagement through advocacy. Parental prioritization of advocating for their children has been seen throughout healthcare. For example, in an assessment of what it means to “be a good parent,” when caring for a child with incurable cancer, parents highlighted “Being an advocate for my child” as one of the top 5 traits of a “good parent,” preceded only by “Being there for my child,” “Conveying love to my child, “Doing right by my child,” and “Being a good life example.” [29]. Parental focus on advocacy is not isolated to children with cancer. Parents of children with severe neurological impairment also stress the value of advocating for their children [30]. The parents we interviewed highlighted that asking questions can help them gain the knowledge base needed to effectively advocate for their children, but they described often feeling too overwhelmed to know which questions to ask.

Parents expressed enthusiasm for a Question Prompt List (QPL) that could help prepare them to ask relevant questions when discussing cancer surgery. The themes we have identified in this study will guide development of a QPL that will empower parents to engage more effectively in surgical discussions. For example, parents in this study highlighted the value of a surgeon’s recommendation. Including a question such as, “What operation do you recommend for my child?” would be a simple way to facilitate this discussion. Parents also expressed their desire to decide when and how to disclose information to family, friends and their community. A question such as, “How can I explain this surgery to my family and friends?” may help parents prepare for such disclosure. Additionally, parental comments about the anxiety and emotional burden resulting from uncertainty about their child’s future suggest that a question such as, “Will my child’s life be different after surgery- will there be new limitations or restrictions?” may be helpful for parents.

Our study has several limitations. This was a single institution study, so parental perceptions may be biased by institutional policies and practices. This limits the generalizability of our results. Performing a qualitative investigation of this issue as opposed to a quantitative study also adds some degree of subjectivity to our results which may impact generalizability [31]. Additionally, we interviewed parents with children of variable ages and diagnoses. This heterogeneity may have prevented identification of specific themes in given patient populations. Our decision to interview parents after children had recovered may also have biased our results in that parents’ reflections on their initial discussions with their child’s surgeon may have been influenced by their overall satisfaction with their child’s treatment course as well as their child’s outcome. Parents of children with more favorable outcomes may have been more likely to participate in our study than parents of children with negative outcomes. The parents we interviewed also all had living children thus suggesting a potential selection bias in that perhaps those parents whose children had died were less likely to participate in the study. Use of social media to identify participants may also have contributed to selection bias in our study. Our work also fails to account for the perspectives of the pediatric patients. Subsequent work should account for the attitudes and preferences of children and adolescents as appropriate based on ability to participate in discussion with the surgeon. Additionally, in our attempt to focus specifically on the interaction between parents and surgeons, we failed to meaningfully explore the impact of other clinicians on parent-surgeon discussions. Although beyond the scope of the current study, future work should address how parent’s interactions with oncologists, radiologists, and other care providers impact parental perceptions of discussions with surgeons.

Conclusions

When discussing cancer surgery for their children, parents view open, honest discussions with surgeons as a means of promoting informed involvement in their child’s care. Parents recognize that, at times, there may be few decisions to make regarding the overall surgical approach to their child’s care. However, they still prioritized asking questions to advocate for their children and valued being made to feel that they were part of a team. The emotional burden of a new cancer diagnosis often prevents parents from knowing which questions to ask. Our work suggests that surgeons should strive to promote opportunities for parents to ask meaningful questions when discussing cancer operations for their children. Parents are enthusiastic about the potential of a QPL to help identify meaningful questions to ask the surgeon. We look forward to merging what we have learned from interviews with parents of pediatric surgical oncology patients with our prior interviews with pediatric surgeons to develop a novel QPL that can empower parents to ask the questions that are most meaningful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the participants for the time and energy they devoted to participating in these often emotional interviews.

Financial Support:

This work was supported by Grant IRG – 18-165-43 from the American Cancer Society, administered through the Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center at The University of Iowa. Dr. Reisinger would like to acknowledge funding from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002537 she received to support her contribution to this research. These funding bodies had no role in the design of the study or collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, or writing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- COREQ

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research

- PTSD

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- QPL

Question Prompt List

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of Interest: None

Level of Evidence: III

References

- 1.Sisk BA, et al. , Emotional Communication in Advanced Pediatric Cancer Conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2020. 59(4): p. 808–817 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vrijmoet-Wiersma CM, et al. , Assessment of parental psychological stress in pediatric cancer: a review. J Pediatr Psychol, 2008. 33(7): p. 694–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Warmerdam J, et al. , Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder in parents of children with cancer: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2019. 66(6): p. e27677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katz LF, et al. , Trajectories of child and caregiver psychological adjustment in families of children with cancer. Health Psychol, 2018. 37(8): p. 725–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Compas BE, et al. , Mothers and fathers coping with their children’s cancer: Individual and interpersonal processes. Health Psychol, 2015. 34(8): p. 783–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gabriel MG, et al. , The Psychosocial Experiences and Needs of Children Undergoing Surgery and Their Parents: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr Health Care, 2018. 32(2): p. 133–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gabriel MG, et al. , Paediatric surgery for childhood cancer: Lasting experiences and needs of children and parents. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl), 2019. 28(5): p. e13116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carlisle EM, et al. , “Reading the room:” A qualitative analysis of pediatric surgeons’ approach to clinical counseling. J Pediatr Surg, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tong A, Sainsbury P, and Craig J, Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care, 2007. 19(6): p. 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palinkas LA, et al. , Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health, 2015. 42(5): p. 533–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McJannett M, et al. , Asking questions can help: development of a question prompt list for cancer patients seeing a surgeon. Eur J Cancer Prev, 2003. 12(5): p. 397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sansoni JE, Grootemaat P, and Duncan C, Question Prompt Lists in health consultations: A review. Patient Educ Couns, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard G.W.R.a.H.R., Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods 2016. 15(1): p. 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glaser BG The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Grounded Theory Review. 12.8.22]; Available from: https://groundedtheoryreview.com/2008/11/29/the-constant-comparative-method-of-qualitative-analysis-1/.

- 15.Urquhart C, Grounded theory for qualitative research: A practical guide. 2013: Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saunders B, et al. , Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant, 2018. 52(4): p. 1893–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bar-Yaakov N, et al. , Parental Regret Following Decision to Revise Circumcision. Front Pediatr, 2022. 10: p. 855893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ritchie KC, Chorney J, and Hong P, Parents’ decisional conflict, self-determination and emotional experiences in pediatric otolaryngology: A prospective descriptive-comparative study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, 2016. 86: p. 114–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghidini F, Sekulovic S, and Castagnetti M, Parental Decisional Regret after Primary Distal Hypospadias Repair: Family and Surgery Variables, and Repair Outcomes. J Urol, 2016. 195(3): p. 720–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlisle EM, et al. , Discrepancies in decision making preferences between parents and surgeons in pediatric surgery. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak, 2021. 21(1): p. 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turgoose DP, et al. , Prevalence of traumatic psychological stress reactions in children and parents following paediatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Paediatr Open, 2021. 5(1): p. e001147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karadeniz Cerit K, et al. , Post-traumatic stress disorder in mothers of children who have undergone cancer surgery. Pediatr Int, 2017. 59(9): p. 996–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Affairs U.D.o.V. How Common is PTSD in Adults? accessed 8.31.22; Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp.

- 24.Kain ZN, et al. , Preoperative anxiety in children. Predictors and outcomes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 1996. 150(12): p. 1238–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caes L, et al. , The relationship between parental catastrophizing about child pain and distress in response to medical procedures in the context of childhood cancer treatment: a longitudinal analysis . J Pediatr Psychol, 2014. 39(7): p. 677–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matarazzo O, et al. , Regret and Other Emotions Related to Decision-Making: Antecedents, Appraisals, and Phenomenological Aspects. Front Psychol, 2021. 12: p. 783248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeelenberg M, et al. , Emotional Reactions to the Outcomes of Decisions: The Role of Counterfactual Thought in the Experience of Regret and Disappointment. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process, 1998. 75(2): p. 117–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gamble LA, et al. , Decision-making and regret in patients with germline CDH1 variants undergoing prophylactic total gastrectomy. J Med Genet, 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hinds PS, et al. , “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children. J Clin Oncol, 2009. 27(35): p. 5979–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogetz JF, et al. , Parents Are the Experts: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Parents of Children With Severe Neurological Impairment During Decision-Making. J Pain Symptom Manage, 2021. 62(6): p. 1117–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carminati L, Generalizability in Qualitative Research: A Tale of Two Traditions. Qual Health Res, 2018. 28(13): p. 2094–2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.