Abstract

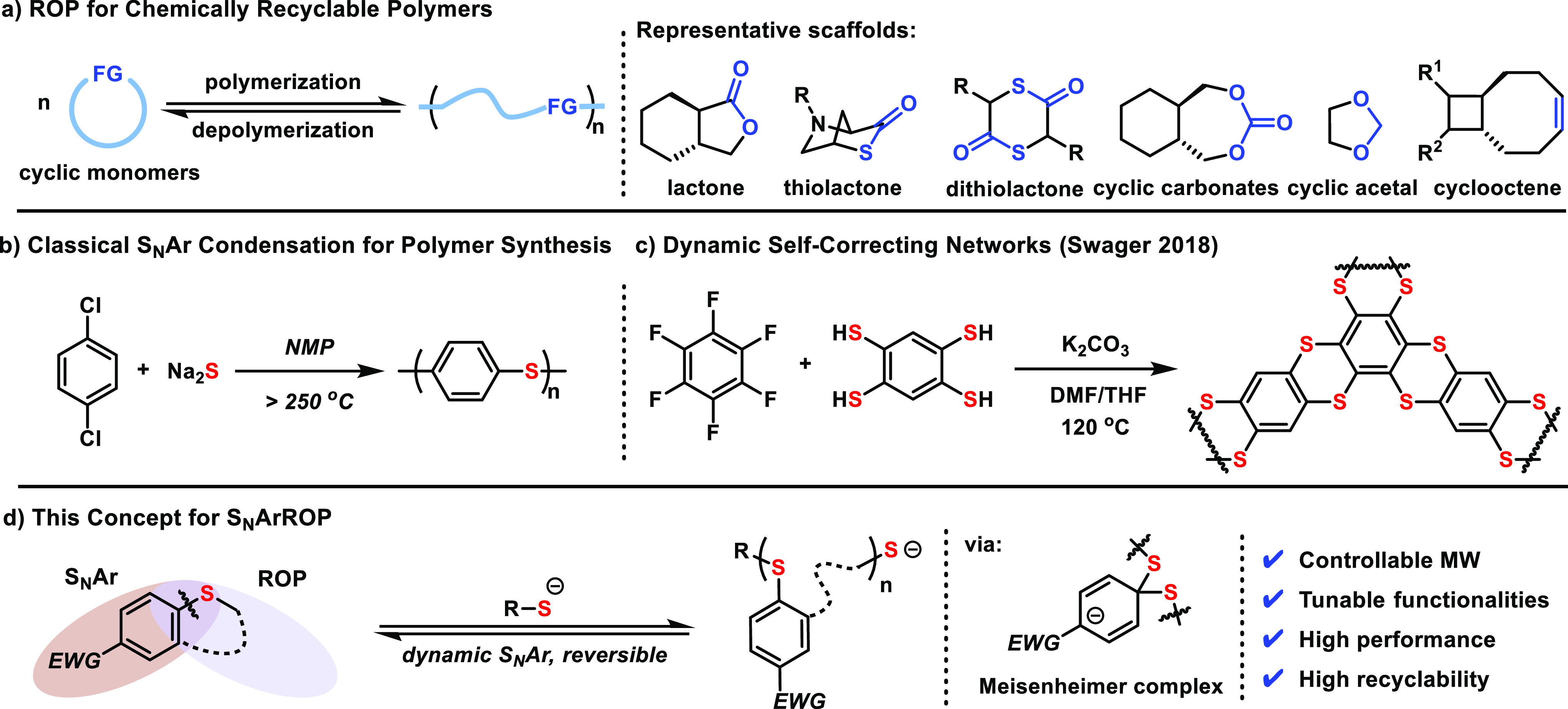

The development of chemically recyclable polymers with desirable properties is a long-standing but challenging goal in polymer science. Central to this challenge is the need for reversible chemical reactions that can equilibrate at rapid rates and provide efficient polymerization and depolymerization cycles. Based on the dynamic chemistry of nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr), we report a chemically recyclable polythioether system derived from readily accessible benzothiocane (BT) monomers. This system represents the first example of a well-defined monomer platform capable of chain-growth ring-opening polymerization through an SNAr manifold. The polymerizations reach completion in minutes, and the pendant functionalities are easily customized to tune material properties or render the polymers amenable to further functionalization. The resulting polythioether materials exhibit comparable performance to commercial thermoplastics and can be depolymerized to the original monomers in high yields.

Introduction

Synthetic polymers are widely used in daily life owing to their wide-ranging functionalities and properties. However, their mass production and consumption, coupled with high durability, result in enormous plastic waste at the end of their useful life.1−3 This end-of-life issue of polymers not only has caused serious environmental and economic challenges but also makes them unsustainable if they cannot be recycled, as 90% of synthetic polymers are derived from finite fossil fuels.4 Existing approaches to addressing the sustainability issue include mechanical recycling,5−7 upcycling to value-added chemicals,8−12 and chemical recycling to monomer (CRM),13−16 among which CRM enables an attractive circular monomer life cycle and economy.

Several classes of designed polymers that are suitable for CRM, such as polyesters,17−20 polythioesters,21−24 polyacetals,25 polycarbonates,26 fused cyclooctene derivatives,27 and others,28−32 have been recently developed (Figure 1a). A common feature among all of these monomer classes is propagation through a ring-opening polymerization (ROP) mechanism and the presence of modest monomer ring strain that gives rise to a low ceiling temperature (Tc). By subjecting these polymers to suitable triggers at elevated temperatures and/or reduced concentrations, the polymers can revert back to their constituent monomers through back-biting and cyclization reactions. Coupled to the overall thermodynamic challenge of identifying monomers with suitable Tc is the challenge of producing polymers with desirable material properties. Chen and co-workers reported the ROP of trans-cyclohexyl-fused γ-butyrolactone, and the polymer exhibited good thermal stability (decomposition temperature Td ∼ 340 °C) and high tensile strength (σB ∼ 55 MPa).18 Through a reversible deactivation cationic ROP, Coates and co-workers synthesized poly(1,3-dioxolane), a thermally stable plastic with high tensile strength (σB ∼ 40 MPa).25 Considering the relatively limited application potential of most CRM polymers reported to date, exploration of new concepts for ring-opening polymerization is targeted in this work.

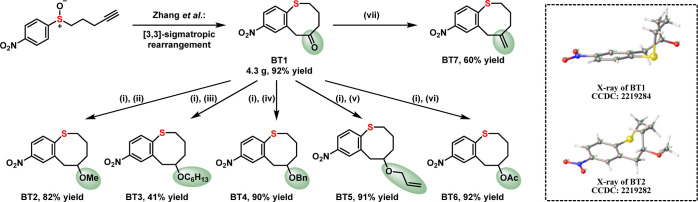

Figure 1.

Designs of nucleophilic aromatic ring-opening polymerization (SNArROP). (a) Established cyclic monomer scaffolds for preparing chemically recyclable polymers. (b) Classical SNAr condensation for the preparation of polyphenylene sulfide (PPS). (c) Dynamic self-correcting SNAr condensation for the synthesis of porous polymer networks. (d) New concept for SNArROP for the synthesis of chemically recyclable polythioethers. The combination of dynamic SNAr chemistry and an appropriate ring size for ROP enable the reversibility of this SNArROP strategy.

To identify suitable chemistries for a new CRM platform, inspiration was found in the dynamic covalent chemistry of nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr).33−38 While numerous high-performance materials have been prepared and industrially used through SNAr polymerization (Figure 1b), limited reports have taken advantage of the chemistry’s inherent reversibility.39−41 The pioneering work by Swager and Ong leveraged this feature to design error-correcting aryl sulfide network polymers (Figure 1c).42 To merge this concept with the potential for recyclability to monomer, a cyclic aromatic thioether capable of SNAr was envisioned that could be polymerized through nucleophilic aromatic ring-opening polymerization (SNArROP) (Figure 1d). While some macrocyclic systems have been shown to polymerize, a well-defined monomer for chain-growth ring-opening polymerization through SNAr chemistry has yet to be realized.43

Results and Discussion

Monomer Design and Synthesis

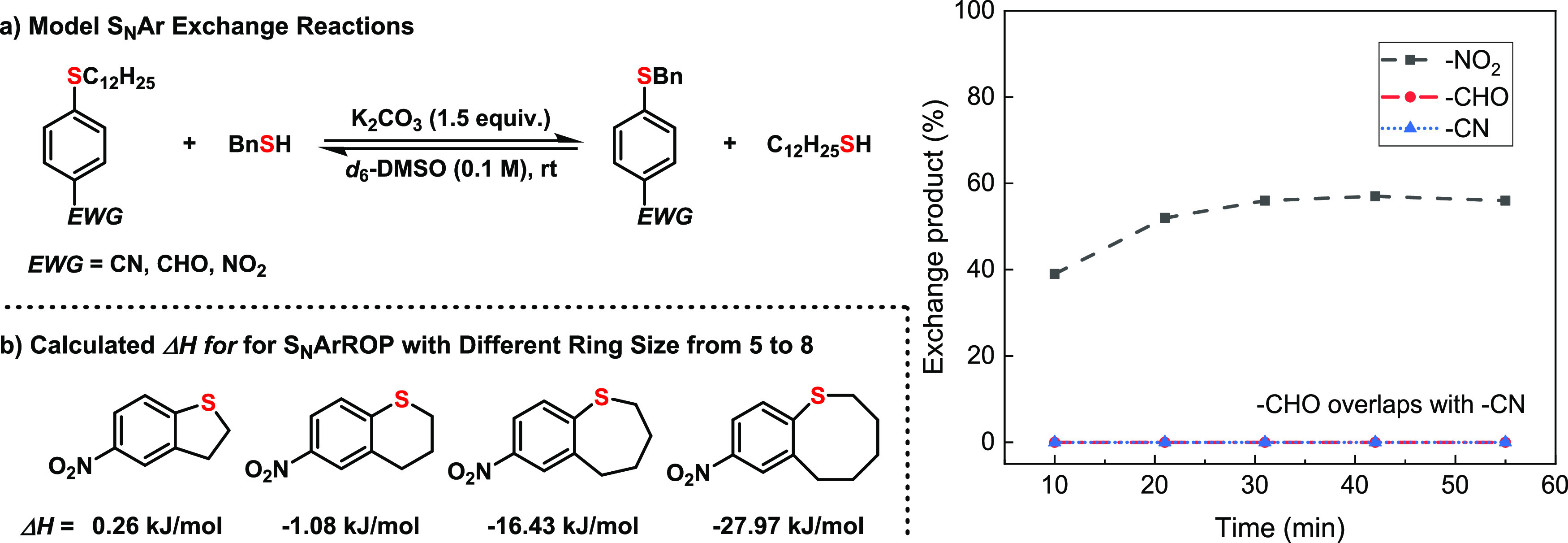

To identify the feasibility of a ring-opening monomer for SNAr, exchange reactions were examined between benzyl mercaptan (BnSH) and aryl dodecyl sulfides with different electron-withdrawing para-substituents (CN, CHO, and NO2). While p-CN and p-CHO-substituted substrates provide no conversion at room temperature and low conversion at 60 °C, p-NO2-phenyl dodecyl sulfide reacted with BnSH smoothly and reached equilibrium in approximately 30 min at room temperature (Figure 2a and Supplementary Figures S7–S9). Based on our recently developed first-principles computational methodology, the ring-opening polymerization (ROP) enthalpy (ΔH) for NO2-substituted cyclic monomer scaffolds was calculated (Figure 2b).44 The results showed that the 7- and 8-membered cyclic aryl thioethers have sufficient ΔH values to promote polymerization (−16.43 and −27.97 kJ/mol, respectively), whereas the 5- and 6-membered substrates were predicted to be insufficiently strained (0.26 and −1.08 kJ/mol). Fortunately, the [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement of alkynyl sulfoxides reported by Zhang and co-workers offered expedient and scalable access to 8-membered ring aryl sulfides (BT1) bearing the requisite nitro-group substitution (Figure 3).45 Additionally, the parent ketone (BT1) was readily reduced to an alcohol that could be further derivatized with a variety of electrophiles to install side-chain functionalities (BT2-BT6) or transformed to BT7 containing an exocyclic C=C double bond through the Wittig reaction (Figure 3). In addition to full characterization of all monomers through 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and mass spectrometry, X-ray structures of BT1 and BT2 were also obtained (Figure 3). The X-ray studies showed that BT1 and BT2 exist in the crystal state exclusively in the boat-chair conformation, and there were two rotamers in BT1 with populations of 97.7 and 2.3%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Identifying the appropriate electron withdrawing group and ring size for the BT monomers. (a) Exchange reactions showing rapid equilibrium established with p-NO2 substituted phenyl sulfide substrate at room temperature but no conversion from the −CN, and −CHO substrates. (b) Calculated ΔH for SNArROP with different ring sizes from 5 to 8, suggesting enthalpically favorable polymerization of 7- and 8-membered ring substrates.

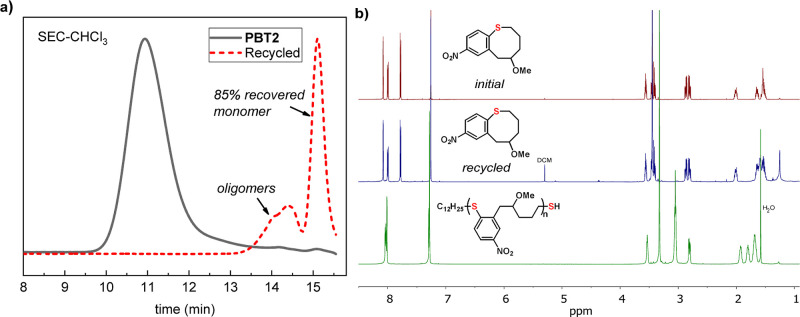

Figure 3.

Synthesis and characterization of the BT monomers. Synthesis of the 8-membered ring substrate BT1 through an efficient [3,3]-sigmatropic rearrangement and its convenient transformation to BT2-BT7. (i) NaBH4, MeOH, 0 °C. (ii) NaH, MeI, THF. (iii) NaH, C6H13I, THF. (iv) NaH, BnBr, DMF. (v) NaH, allyl bromide, DMF. (vi) Ac2O, DMAP, pyridine. (vii) tBuOK, PPh3PMeBr, THF. The X-ray of BT1 and BT2 are shown as the insert.

Polymerization Studies

At the outset, the polymerizability of BT1 was probed via measuring its exchange reaction with BnSH, and a rapid exchange reaction was finished between BT1 and BnSH in DMSO-d6 with K2CO3 as the base at room temperature (Supplementary Figure S10). To keep the polymerization homogeneous, the organic base DBU instead of the inorganic base K2CO3 was used. A preliminary polymerization test with a [BT1]0/[DBU]0/[C12H25SH]0 ratio of 50:1:1 yielded a poorly soluble polymer PBT1 with almost full conversion (Figure 4a, entry 1). The methyl ether side-chain of BT2 improved the solubility of the corresponding polymer and facilitated the study of the molecular weight and dispersity through gel permeation chromatography (GPC) while still maintaining high conversions. Solvent choice proved to be critical for polymerization. Fast reaction rates and high conversions were generally found in polar aprotic solvents, including dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), dimethylformamide (DMF), dimethylacetamide (DMA), N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), and N,N′-dimethylpropyleneurea (DMPU), while no reaction at all in relatively less polar solvents such as chloroform (CHCl3), 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE), and tetrahydrofuran (THF) (Supplementary Table S1). These results can be explained by the requirement of a polar environment to stabilize the Meisenheimer intermediate (Figure 1d) in the nucleophilic aromatic substitution step.46−48 While the experimental Mn values were slightly higher than those calculated from the ratio of [M]0/[I]0 and conversion, targetable molecular weights were readily obtained. A small peak in the lower molecular weight range was observed in the GPC traces, suggesting the possible formation of cyclic oligomer byproducts, which was further confirmed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Supplementary Figures S12 and S13). By increasing the monomer concentration, the cyclic oligomer byproducts were limited, and a unimodal high-molecular-weight polymers were obtained (Supplementary Table S2). Interestingly, the polymerization was found to readily proceed to high conversion at a wide range of temperatures (90 to 140 °C) (Supplementary Table S2). A variety of bases and thiol initiators were further screened, and strong bases with higher pKa and more nucleophilic thiolates were found beneficial for the polymerization (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5).

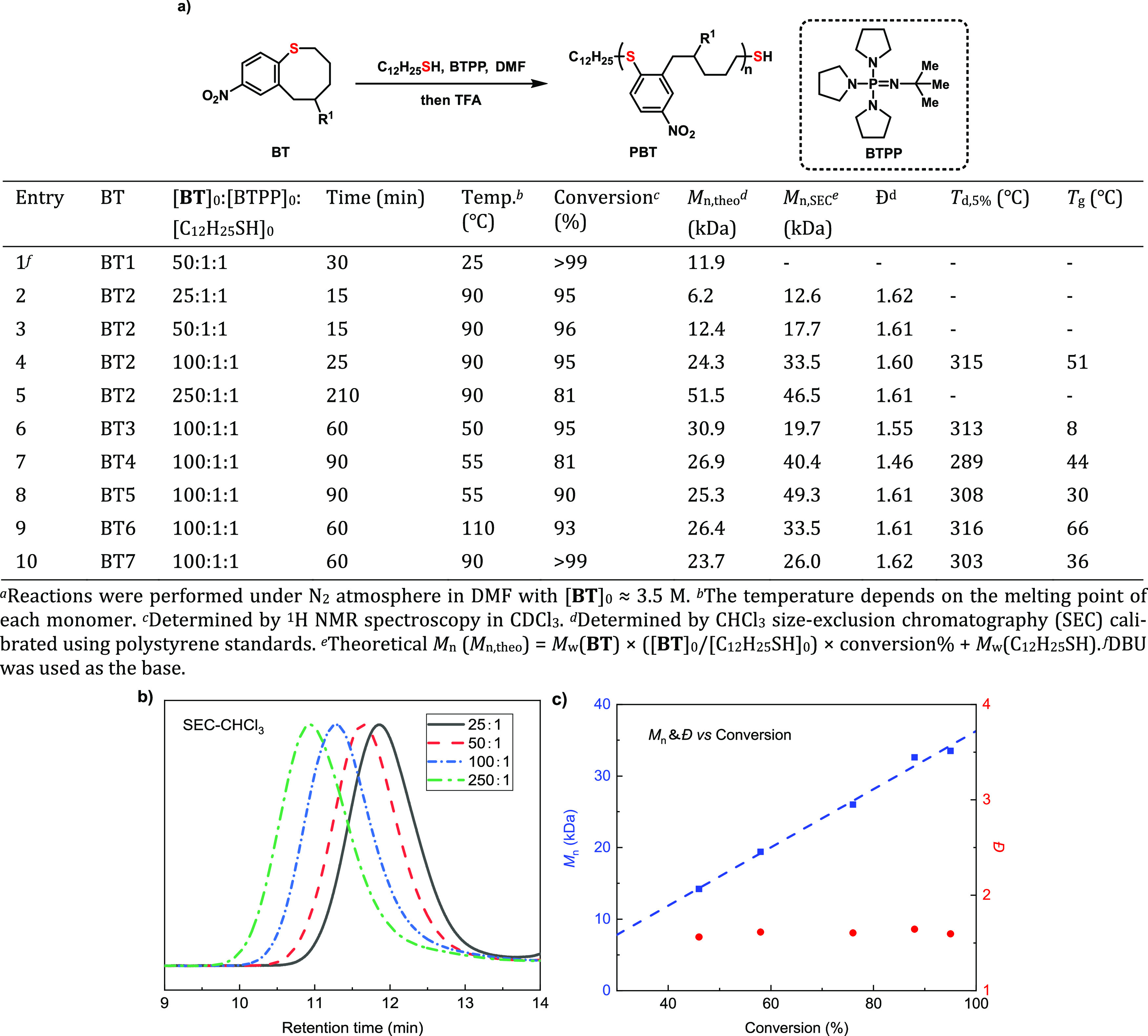

Figure 4.

SNArROP of BT monomersand characterization of PBTs. (a) Results of BT polymerizations by BTPP-based catalytic systems. (b) SEC curves for PBT2 produced at different [BT2]0/[BTPP]0/[C12H25SH]0 ratios. (c) Mn–conversion correlation (blue) and D̵–conversion correlation (red) of SNArROP of BT2.

Under the optimized reaction conditions, a series of molecular weight targets were obtained by adjusting the monomer-to-initiator ratio ([BT2]0/[BTPP]0/[C12H25SH]0) from 25:1:1 to 250:1:1 (Figure 4a, entries 2–5). Moreover, the molecular weight increased linearly as the monomer to initiator ratio increased, while the corresponding dispersity (Đ) remained at a modest value (∼1.60) during polymerization (Figure 4b). These data strongly support a chain-growth mechanism to the polymerization with chain-transfer events occurring between propagating polymers and the aryl sulfide backbone. Next, the generality of the SNArROP strategy was investigated using monomers bearing different substituents (O–C6H13, O–Bn, O–allyl, O–Ac, and C=C). The SNArROP of these monomers was achieved at a temperature slightly higher than their melting points at a 3.5 M monomer concentration to ensure solubility throughout the polymerization (Figure 4a, entries 6–10). The corresponding polymers with molecular weight ranging from 19.7 to 49.3 kDa and consistent Đ values ranging from 1.46 to 1.62 were obtained from a [BT]0/[BTPP]0/[C12H25SH]0 ratio of 100:1:1. The substituents showed a slight influence on the polymerization reactivity, as shown by the conversion ranging from 81 to 99%. The convenient introduction of these various functional groups enables the tuning of the resulting material’s properties as shown below.

Thermal and Mechanical Properties

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) were used to measure the thermal properties for each poly(aryl thioether). All the produced polymers obtained with [BT]0/[BTPP]0/[C12H25SH]0 = 100:1:1 displayed high thermal stability with a range of thermal decomposition temperature Td (defined as the temperature causing a 5% weight loss) from 289 to 316 °C (Figure 4a and Supplementary Figure S16). Depending on the pendant groups on the monomers, a wide range of Tgs from 8 to 66 °C can be accessed (Figure 4a and Supplementary Figure S16). The absence of clear melting transitions indicates the amorphous character of these polymers, which could be explained by atactic microstructures generated from the racemic monomers.

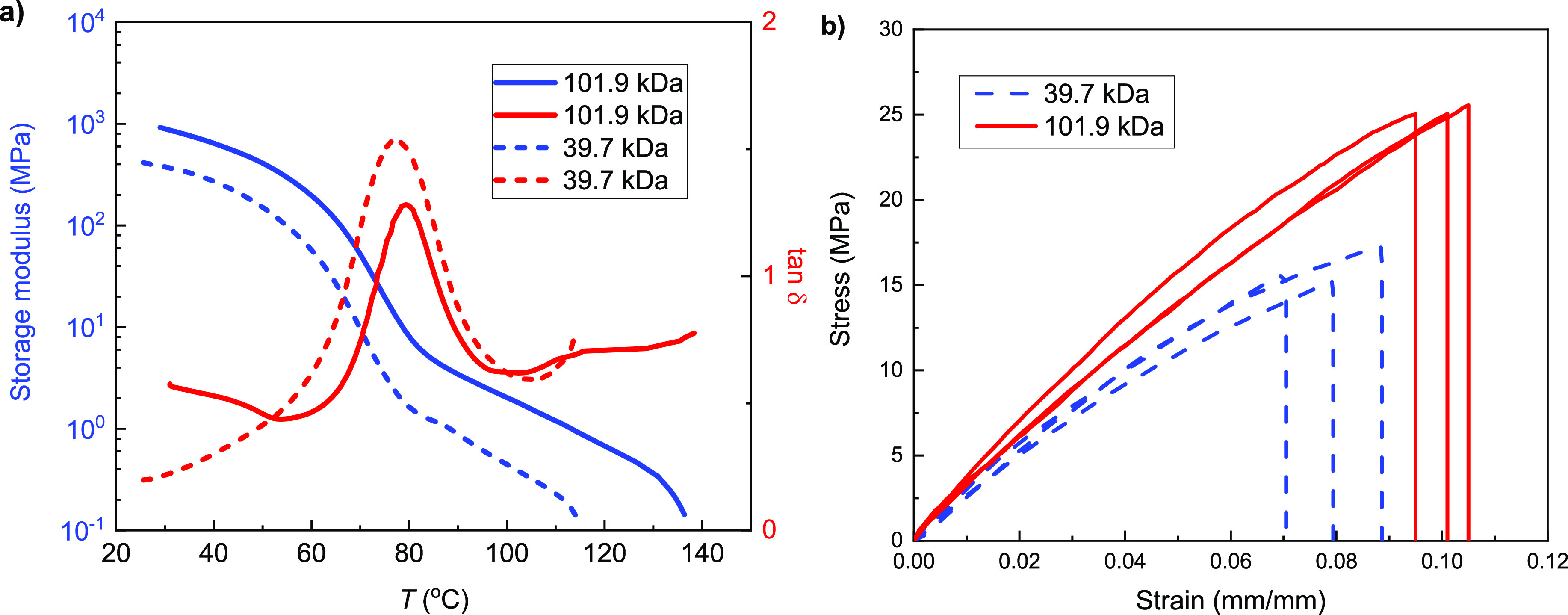

Further investigation was focused on the thermal and mechanical properties of these PBT samples, especially the effect of the molecular weight on these properties. PBT2 with two different Mn (39.7 kDa and 101.9 kDa) was prepared. PBT2s exhibited the typical behavior of a thermoplastic polymer as shown by dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) (Figure 5). Both samples possessed relatively high storage modulus (E′) at room temperature as glassy polymers. However, after the glass transition region with Tg values around 80 °C (as defined by the peak maxima of tanδ), E′ continually decreased until a quick drop to the viscous flow state due to melting (Figure 5a). The sample with a higher molecular weight displayed both higher E′ and Tg as expected (Mn = 39.7 kDa: E′ = 375.1 MPa (30 °C), Tg = 77.8 °C; Mn = 101.9 kDa: E′ = 1243.8 MPa (30 °C), Tg = 79.5 °C). Furthermore, tensile testing of the PBT2 showed the same trend as a glassy polymer with Young̀s modulus E = 275.6 ± 19.9 and 349.9 ± 18.76 MPa, ultimate tensile strength σ = 16.07 ± 0.84 and 25.21 ± 0.24 MPa, and elongation at break ε = 7.95 ± 0.74 and 10.03 ± 0.41% for the 39.7 and 101.9 kDa samples, respectively (Figure 5b). The tensile performance is within the range of some commonly used thermoplastics such as polyethylene (PE), ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), suggesting applications potential upon further increases to molecular weight or the addition of plasticizers.

Figure 5.

Mechanical properties of PBT2. (a) DMA storage modulus and tan δ profiles of PBT2 with different molecular weights. (b) Tensile stress–strain curves of PBT2 with different molecular weights.

Chemical Recyclability

As an effort to achieve the original purpose of designing recyclable polymers with robust and durable behavior, the advantages of PBTs in mechanical properties led us to explore the recyclability to monomers of these polymers. The initial attempts to depolymerize the parent polymer PBT2 from the chain end by adding the DBU were unsuccessful, but the introduction of additional thiol was found to help conversion through cleaving segments from the polymer backbone for depropagation (Supplementary Figure S19 and Figure S20). By adding 0.55 equivalent of DBU and C12H25SH relative to the repeat unit at a temperature of 90 °C and a concentration of 10 mg/mL, an isolated yield of 85% for BT2 was achieved (Figure 6). This depolymerization is likely initiated through backbone cleavage due to reversible SNAr chemistry, which is further supported by the successful depolymerization of an end-capped PBT5 (capped with iodoacetamide) producing monomer BT5 in 70% yield (Supplementary Figure S21).

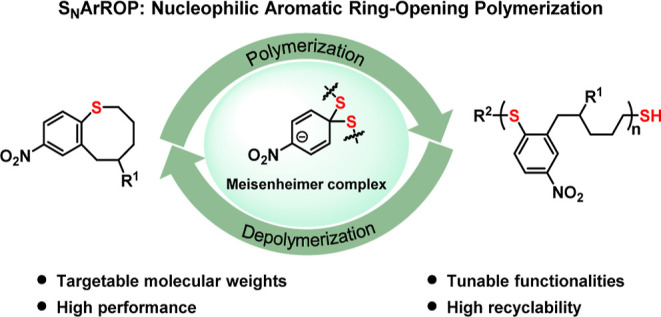

Figure 6.

Chemical recyclability of PBT2. (a) SEC curves for depolymerization of PBT2 (46.5 kDa) with substoichiometric DBU and C12H25SH (0.55 equiv relative to repeat units). (b) Overlays of 1H NMR spectra of initial and recycled BT2 and PBT2.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the dynamic reversibility of SNAr chemistry and ring-opening polymerization have been successfully merged into a well-defined monomer platform for the first time. SNArROP of BTs is an effective and powerful strategy for the synthesis of chemically recyclable polythioethers. The facile modification of the monomer scaffold leads to readily tunable material properties, and the high recyclability suggests that the BT platform is a robust candidate for the design of new dynamic and depolymerizable polymers capable of CRM. Further studies on post-polymerization modification to chemically crosslink and 3D print recyclable materials are currently underway.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by ONR MURI N00014-20-1–2586. We acknowledge support from the Organic Materials Characterization Laboratory (OMCL) at GT for use of the shared characterization facility. We thank Dr. John Bacsa (Emory University) for assistance with X-ray crystallography.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.3c03455.

Experimental procedure and spectroscopic data for all new compounds and X-ray crystallographic data for BT1 and BT2 (PDF).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Stubbins A.; Law K. L.; Muñoz S. E.; Bianchi T. S.; Zhu L. Plastics in the Earth System. Science 2021, 373, 51–55. 10.1126/science.abb0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod M.; Arp H. P. H.; Tekman M. B.; Jahnke A. The Global Threat from Plastic Pollution. Science 2021, 373, 61–65. 10.1126/science.abg5433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer R.; Jambeck J. R.; Law K. L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, 25–29. 10.1126/sciadv.1700782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the Future of Plastics and Catalysing Action Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017.

- Schyns Z. O. G.; Shaver M. P. Mechanical recycling of packaging plastics: A review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2021, 42, e2000415 10.1002/marc.202000415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billiet S.; Trenor S. R. 100th Anniversary of Macromolecular Science Viewpoint: Needs for Plastics Packaging Circularity. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 1376–1390. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.0c00437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer I.; Jenks M. J. F.; Roelands M. C. P.; White R. J.; Harmelen T.; Wild P.; Laan G. P.; Meirer F.; Keurentjes J. T. F.; Weckhuysen B. M. Beyond Mechanical Recycling: Giving New Life to Plastic Waste. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15402–15423. 10.1002/anie.201915651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi A.; García J. M. Chemical Recycling of waste plastics for new materials production. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0046. 10.1038/s41570-017-0046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jehanno C.; Perez-Madrigal M. M.; Demarteau J.; Sardon H.; Dove A. P. Organocatalysis for Depolymerisation. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 172–186. 10.1039/c8py01284a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F.; Zeng M.; Yappert R. D.; Sun J.; Lee Y. H.; LaPointe A. M.; Peters B.; Abu-Omar M. M.; Scott S. L. Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromatics by tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science 2020, 370, 437–441. 10.1126/science.abc5441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korley L. T. J.; Epps T. H.; Helms B. A.; Ryan A. J. Toward polymer upcycling-adding value and tackling circularity. Science 2021, 373, 66–69. 10.1126/science.abg4503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis L. D.; Rorrer N. A.; Sullivan K. P.; Otto M.; McGeehan J. E.; Román-Leshkov Y.; Wierckx N.; Beckham G. T. Chemical and biological catalysis for plastics recycling and upcycling. Nat. Catal. 2021, 4, 539–556. 10.1038/s41929-021-00648-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong M.; Chen E. Y. X. Chemically Recyclable Polymers: A Circular Economy Approach to Sustainability. Green Chem 2017, 19, 3692–3706. 10.1039/c7gc01496a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman D. K.; Hillmyer M. A. 50th Anniversary Perspective: There Is a Great Future in Sustainable Polymers. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 3733–3749. 10.1021/acs.macromol.7b00293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X.-B.; Liu Y.; Zhou H. Learning Nature: Recyclable Monomers and Polymers. Chem.–Eur. J. 2018, 24, 11255–11266. 10.1002/chem.201704461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates G. W.; Getzler Y. D. Y. L. Chemical Recycling to Monomer for an Ideal, Circular Polymer Economy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 501–516. 10.1038/s41578-020-0190-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman D. K.; Vanderlaan M. E.; Mannion A. M.; Panthani T. R.; Batiste D. C.; Wang J. Z.; Bates F. S.; Macosko C. W.; Hillmyer M. A. Chemically Recyclable Biobased Polyurethanes. ACS Macro Lett. 2016, 5, 515–518. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.6b00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.-B.; Watson E. M.; Tang J.; Chen E. Y.-X. A Synthetic Polymer System with Repeatable Chemical Recyclability. Science 2018, 360, 398–403. 10.1126/science.aar5498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X.; Chen E. Y. X. Toward Infinitely Recyclable Plastics Derived from Renewable Cyclic Esters. Chem 2019, 5, 284–312. 10.1016/j.chempr.2018.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Häußler M.; Eck M.; Rothauer D.; Mecking S. Closed-Loop Recycling of Polyethylene-like Materials. Nature 2021, 590, 423–427. 10.1038/s41586-020-03149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan J.; Xiong W.; Zhou X.; Zhang Y.; Shi D.; Li Z.; Lu H. 4-Hydroxyproline-Derived Sustainable Polythioesters: Controlled Ring-Opening Polymerization, Complete Recyclability, and Facile Functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4928–4935. 10.1021/jacs.9b00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Li M.; Chen J.; Tao Y.; Wang X. O-to-S Substitution Enables Dovetailing Conflicting Cyclizability, Polymerizability, and Recyclability: Dithiolactone vs. Dilactone. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 22547–22553. 10.1002/anie.202109767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellmach K. A.; Paul M. K.; Xu M.; Su Y.-L.; Fu L.; Toland A. R.; Tran H.; Chen L.; Ramprasad R.; Gutekunst W. R. Modulating Polymerization Thermodynamics of Thiolactones Through Substituent and Heteroatom Incorporation. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11, 895–901. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.2c00319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Zhu Y.; Lv W.; Wang X.; Tao Y. Tough while Re-cyclable Plastics Enabled by Monothiodilactone Monomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 1877–1885. 10.1021/jacs.2c11502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abel B. A.; Snyder R. L.; Coates G. W. Chemically Recyclable Thermoplastics from Reversible-Deactivation Polymerization of Cyclic Acetals. Science 2021, 373, 783–789. 10.1126/science.abh0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Dai J.; Wu Y.-C.; Chen J.-X.; Shan S.-Y.; Cai Z.; Zhu J.-B. Highly Reactive Cyclic Carbonates with a Fused Ring toward Functionalizable and Recyclable Polycarbonates. ACS Macro Lett. 2022, 11, 173–178. 10.1021/acsmacrolett.1c00653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathe D.; Zhou J.; Chen H.; Su H.-W.; Xie W.; Hsu T.-G.; Schrage B. R.; Smith T.; Ziegler C. J.; Wang J. Olefin Metathesis-Based Chemically Recyclable Polymers Enabled by Fused-Ring Monomers. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 743–750. 10.1038/s41557-021-00748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.; Jia Y.; Wu Q.; Moore J. S. Architecture-Controlled Ring-Opening Polymerization for Dynamic Covalent Poly(Disulfide)S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17075–17080. 10.1021/jacs.9b08957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen P. R.; Scheuermann A. M.; Loeffler K. E.; Helms B. A. Closed-Loop Recycling of Plastics Enabled by Dynamic Covalent Diketoenamine Bonds. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 442–448. 10.1038/s41557-019-0249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Giardino G. J.; Chen R.; Yang C.; Niu J.; Wang D. Photocatalytic Depolymerization of Native Lignin toward Chemically Recyclable Polymer Networks. ACS Cent. Sci. 2023, 9, 48–55. 10.1021/acscentsci.2c01257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. C.; Li M. S.; Wang S. X.; Tao Y. H.; Wang X. H. S. -Carboxyanhydrides: Ultrafast and Selective Ring-Opening Polymerizations Towards Well-defined Functionalized Polythioesters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 10798–10805. 10.1002/anie.202016228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X.; Wei Z.; Seo B.; Hu Q.; Wang X.; Romo J. A.; Jain M.; Cakmak M.; Boudouris B. W.; Zhao K.; Mei J.; Savoie B. M.; Dou L. Circularly Recyclable Polymers Featuring Topochemically Weakened Carbon-Carbon Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 16588–16597. 10.1021/jacs.2c06417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan S. J.; Cantrill S. J.; Cousins G. R. L.; Sanders J. K. M.; Stoddart J. F. Dynamic covalent chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 898–952. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Jin Y.. Dynamic Covalent Chemistry: Principles, Reactions, and Applications; John Wiley & Sons,2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y.; Wang Q.; Taynton P.; Zhang W. Dynamic covalent chemistry approaches toward macrocycles, molecular cages, and polymers. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1575–1586. 10.1021/ar500037v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou W.; Dong J.; Luo Y.; Zhao Q.; Xie T. Dynamic covalent polymer networks: from old chemistry to modern day innovations. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1606100. 10.1002/adma.201606100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrillo A. G.; Furlan R. L. E. Sulfur in Dynamic Covalent Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, e202201168 10.1002/anie.202201168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z.; Chen H.; Luo C.; Rong Y.; Hu Y.; Jin Y.; Long R.; Yu K.; Zhang W. Recyclable and malleable thermosets enabled by activating dormant dynamic linkages. Nat. Chem. 2022, 14, 1399–1404. 10.1038/s41557-022-01046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robb M. J.; Knauss D. M. Poly(Arylene Sulfide)s by Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution Polymerization of 2,7-Difluorothianthrene. J. Polym. Sci., Part A: Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 2453–2461. 10.1002/pola.23341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins M. J.; Woo E. P.; Balon K. E.; Murray D. J.; Chen C. C. U.S. Patent 5 264 538, 1993.

- Jiang H.; Chen T.; Qi Y.; Xu J. Macrocyclic Oligomeric Arylene Ether Ketones: Synthesis and Polymerization. Polym. J. 1998, 30, 300–303. 10.1295/polymj.30.300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ong W. J.; Swager T. M. Dynamic self-correcting nucleophilic aromatic substitution. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 1023–1030. 10.1038/s41557-018-0122-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagnaro P.; Brunengo E.; Conzatti L. ED-ROP of macrocyclic oligomers: A synthetic tool for multicomponent polymer materials. ARKIVOC 2021, 2021, 174–221. 10.24820/ark.5550190.p011.600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tran H.; Toland A.; Stellmach K.; Paul M. K.; Gutekunst W.; Ramprasad R. Toward Recyclable Polymers: Ring-Opening Polymerization Enthalpy from First-Principles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 4778–4785. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c00995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B.; Li Y.; Wang Y.; Aue D. H.; Luo Y.; Zhang L. [3,3]- Sigmatropic Rearrangement versus Carbene Formation in Gold-Catalyzed Transformations of Alkynyl Aryl Sulfoxides: Mechanistic Studies and Expanded Reaction Scope. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 8512–8524. 10.1021/ja401343p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrier F.Modern Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitutions; Wiley-VCH:Weinheim,2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kwan E. E.; Zeng Y.; Besser H. A.; Jacobsen E. N. Concerted Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitutions. Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 917–923. 10.1038/s41557-018-0079-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbach S.; Murphy J. A.; Tuttle T. Computational Study on the Boundary Between the Concerted and Stepwise Mechanism of Bimolecular SNAr Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 14871–14876. 10.1021/jacs.0c01975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.