Abstract

Patient: Male, 64-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Pheochromocytoma • primary aldosteronism

Symptoms: Hypertension

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Endocrinology and metabolic

Objective:

Rare coexistence of disease or pathology

Background:

Primary aldosteronism and pheochromocytoma are endocrine causes of secondary arterial hypertension. The association of primary aldosteronism and pheochromocytoma is rare and the involved mechanisms are poorly understood. Either there is a coexistence of both diseases or the pheochromocytoma stimulates the production of aldosterone. Since management approaches may differ significantly, it is important to properly diagnose the 2 conditions. We describe concomitant pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism in a patient with resistant hypertension, which demanded a challenging and individualized approach.

Case Report:

A 64-year-old man was sent for observation in our department for type 2 diabetes and resistant hypertension. Laboratory work-up suggested a primary aldosteronism and a pheochromocytoma. The abdominal CT (before and after intravenous contrast, with portal and delayed phase acquisitions) revealed an indeterminate right adrenal lesion and 3 nodules in the left adrenal gland: 1 indeterminate and 2 compatible with adenomas. A 18F-FDOPA PET-CT showed increased uptake in the right adrenal gland. The patient underwent a right adrenalectomy and a pheochromocytoma was confirmed. An improvement in glycemic control was observed after surgery but the patient remained hypertensive. A captopril test confirmed the persistence of primary aldosteronism, and he was started on eplerenone, achieving blood pressure control.

Conclusions:

This case highlights the challenges in diagnosing and treating the simultaneous occurrence of pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism. Our main goal was surgical removal of the pheochromocytoma due to the risk of an adrenergic crisis.

Keywords: Hyperaldosteronism, Hypertension, Pheochromocytoma

Background

Hypertension may be the initial clinical presentation for several endocrine diseases, including primary aldosteronism and pheochromocytoma. While the prevalence of primary aldosteronism is 5% to 10% in hypertensive patients and 20% on those with treatment-resistant hypertension [1], the prevalence of pheochromocytoma is much lower (0.05–0.1%) [2].

Simultaneous occurrence of pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism is rare, with only 15 patients described in a case series and literature review by Mao et al [2]. Hypertension was present at diagnosis in 80% of these patients. Although the small sample size does not allow establishing a definitive relationship between pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism, 2 different mechanisms may be considered – either there is a coexistence of the 2 diseases, or an aldosterone-stimulating factor is secreted by the pheochromocytoma, causing aldosteronism [2].

Since primary aldosteronism and pheochromocytoma have different therapeutic approaches, it is important to properly diagnose both conditions. While the former can be surgically or medically treated [3], pheochromocytomas demand surgical removal with proper preoperative therapy to avoid lethal hypertensive crises or malignant arrhythmias [4]. In a review by Mao et al [2], 13 patients that underwent surgery for primary aldosteronism, without suspicion for pheochromocytoma, had an intraprocedural increase in blood pressure to 200/120 mmHg.

We describe a case of concomitant pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism in a patient with resistant hypertension, which demanded a challenging and individualized approach.

Case Report

A 64-year-old man was observed in our Endocrinology Department due to type 2 diabetes (T2D) with a recent deterioration in glycemic control, and resistant hypertension. T2D was diagnosed at the age of 50 years old, and was medicated with metformin 2000 mg/day, sitagliptin 100 mg/day, and gliclazide 60 mg/day. His T2D was poorly controlled, with a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 63.9 mmol/mol (8%). Regarding T2D complications, the patient did not present atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, retinopathy, or neuropathy, but had stage 3b chronic kidney disease with a glomerular filtration rate of 0.6 ml/s (35.9 mL/min/1.73 m2).

Hypertension was diagnosed around the same time as T2D and was difficult to control. At the time of the first observation in our department, he was medicated with lercanidipine 10 mg/day, azilsartan 40 mg/day, chlorthalidone 12.5 mg/day, and nebivolol 5 mg/day. Despite this medication, he maintained a daily ambulatory record of systolic blood pressure around 190–210 mmHg and diastolic of 110–130 mmHg.

Regarding other habits or diseases, there was also a dyslipidemia diagnosis, treated with pitavastatin 2 mg. There was no history of smoking, drinking alcohol, or illicit drug use.

As for family history, both his mother and 1 sister had T2D, and his father died at 65 years old from complications related to chronic kidney disease of unknown cause to the patient.

Besides the sustained hypertension and the poor glycemic control, the patient denied other symptoms or signs suggestive of pheochromocytoma or primary aldosteronism, such as headache, sweating, palpitations, tremor, pallor, dyspnea, or weakness.

Upon observation, the patient measured 1.73 m, weighed 84 kg (body mass index of 28 kg/m2), was hypertensive (191–116 mmHg), with a normal heart rate (74 beats per minute), and normal tympanic temperature (36.7°C). The postprandial capillary blood glucose was 189 mg/dL. On physical exam, the neck inspection and palpation did not reveal any nodules, goiter, or enlarged lymph nodes. The cardiac and pulmonary auscultations were normal, the abdominal inspection and palpation were painless, without organomegaly, masses, or ascites. The lower limbs did not show signs of peripheral edema or abnormal temperature, and all pulses were normal.

To screen for endocrine hypertension, a laboratory evaluation was requested (Table 1). The results showed suppressed plasma renin activity (PRA) (<0.2 µg/L/hour [<0.2 ng/ml/hour]); high aldosterone (0.74 nmol/L [26.8 ng/dL]); high aldosterone/PRA ratio (3.72 (nmol/L)/(µg/L/h) [134 (ng/dL)/(ng/mL/h)]); and hypokalemia (3.3 mmol/L). It also revealed a high urinary excretion of metanephrines (metanephrine 2403 nmol/day [474 µg/24h]; normetanephrine 5529 nmol/day [1013 µg/24h]; 3-Methoxytyramine 1033 nmol/day [345 µg/24h]), with negative chromogranin A (3.7 nmol/L [104 ng/mL]). Despite a low ACTH (1.4 pmol/L [6.4 pg/mL]), urinary cortisol was within normal range (15.5 mmol/L [5.6 µg/24h]).

Table 1.

Initial laboratory results.

| Analyte | Conventional units | International system | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Normal range | Result | Normal range | |

| Plasma renin activity (serum) | <0.2 ng/ml/h | 0.2–1.6 | < 0.2 µg/L/hour | 0.2–1.6 |

| Aldosterone (serum) | 26.8 ng/dL | 1–16 | 0.74 pmol/L | 0.03–0.44 |

| Aldosterone/plasma renin activity | 134 (ng/dL)/(ng/mL/h) | <30 | 3.72 (nmol/L)/(µg/L/h) | <0.8 |

| Potassium | 3.3 mEq/L | 3.5–5.5 | 3.3 mmol/L | 3.5–5.5 |

| Methanephrine (urine) | 474 µg/24h | 64–302 | 2403 nmol/day | 325–1531 |

| Normetanephrine (urine) | 1013 µg/24h | 162–527 | 5529 nmol/day | 884–2877 |

| 3-Methoxytiramine (urine) | 345 µg/24h | 30–434 | 1033 nmol/day | 90–1302 |

| Chromogranin A | 3.7 nmol/L | 0–5 | 3.7 nmol/L | 25–140 |

| ACTH | 6.4 pg/mL | 7.2–63.3 | 1.4 pmol/L | 1.5–14 |

| Cortisol (urine) | 5.6 µg/24h | 4.3–176 | 15.5 mmol/L | 11.9–486 |

| TSH | 2.19 µUI/ml | 0.35–4.94 | 2.19 mIU/L | 0.35–4.94 |

| FT4 | 0.88 ng/dL | 0.7–1.48 | 11.35 pmol/L | 9–19 |

| HbA1c | 8.0% | <7% | 63.9 mmol/mol | <53 |

To confirm a primary aldosteronism diagnosis, the patient performed a recumbent saline infusion test, resulting in an inconclusive serum aldosterone of 0.26 nmol/L (9.5 ng/dL) after 4 hours (ref. <0.27 nmol/L [<10 ng/dL]), with a decrease in potassium (from 3.5 to 2.8 mmol/L).

The patient was started on spironolactone, obtaining a good blood pressure response (130–80 mmHg), which supported a primary aldosteronism diagnosis.

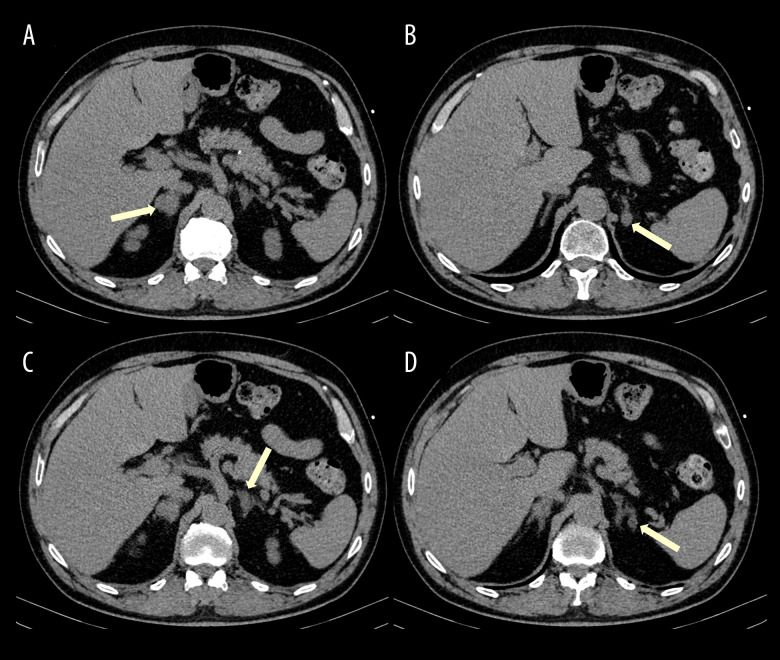

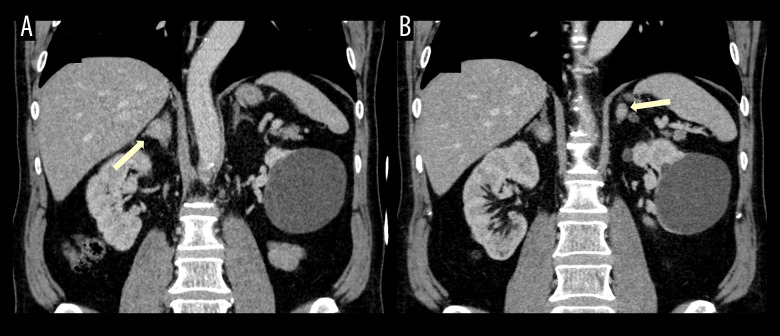

An enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed nodules in both adrenal glands. A single nodule was located in the right adrenal gland measuring around 2 cm (Figures 1A and 2A), with 23 HU on non-enhanced scan and absolute and relative washout pattern of 60% and 35.1%, a pattern of non-adenoma. The CT also identified 3 other nodules in the left adrenal gland: 1 indeterminate nodule (Figures 1B and 2B) with 1.4 cm, 12 HU with 12HU before intravenous contrast injection and absolute and relative wash-out of 50% and 37.5%, respectively; and 2 others with 1.3 and 1 cm (Figure 1C, 1D), less than 10 HU on non-enhanced scan, compatible with adenomas.

Figure 1.

Non-enhanced abdominal CT, axial plane. Four nodules (yellow arrows) can be detected in the adrenal glands: 2 indeterminate (one in the right gland – A; the other in the left gland – B) and 2 compatible with adenomas in the left adrenal gland – C and D.

Figure 2.

Intravenous contrast-enhanced abdominal CT (portal phase), coronal reconstructions, showing the 2 indeterminate adrenal nodules (yellow arrows, A – right adrenal gland; B – left adrenal gland).

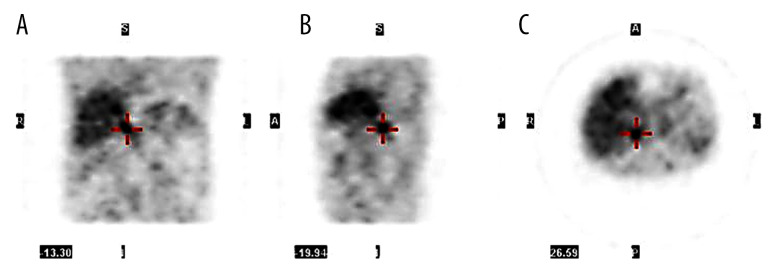

To clarify whether there was a single pheochromocytoma or if it was a bilateral presentation, we requested a 6-[F-18]-L-fluoro-L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (F-18 FDOPA) positron emission tomography with CT (PET-CT), which showed an elevated dihydroxiphenylalanine uptake exclusively in the right adrenal gland (Figure 3). A multidisciplinary group discussed the approach and decided on a laparoscopic right adrenalectomy.

Figure 3.

Positron emission tomography with complementary CT (PET/CT). An elevated di-hydroxiphenylalanine uptake exclusively in the right adrenal gland can be observed in the different planes, coronal (A), sagittal (B), transverse (C).

The patient was admitted in our hospital 2 weeks before surgery, according to our department protocol, for blood pressure, heart rate, and glycemic control, and to correct any volume depletion or hydroelectrolytic imbalance. On admission he was started on phenoxybenzamine and insulin for blood pressure and glycemic control, and intravenous fluids. During this period, a dose of 210 mg/day (2.8 mg/kg/day) of phenoxybenzamine combined with nebivolol 5 mg was not enough to achieve adequate blood pressure control. Only by reintroducing spironolactone was it possible to maintain a profile below 140-90 mmHg. The glycemic control was also difficult to achieve, and the patient needed 66 units/day of insulin to maintain the target inpatient glycemia (100–180 mmHg). The procedure went well, without complications.

Histology revealed a pheochromocytoma with 20×18×15 mm, trabecular neoplasm, negative for spindle cells, cytoplasm with hemosiderin, melanin, neuromelanin and lipofuscin granules, nuclei with moderate anisokaryosis, less than 3 mitoses per 10 high-power fields, no atypical mitoses, no necrosis, no lymphangioinvasion, no capsular or adipose tissue invasion, and with tumor-free surgical margins. These findings summed a zero PASS score, suggesting a low aggressive tumor potential.

Next-generation sequencing did not identify any pathologic somatic variants or germinal mutations.

One month after surgery, the patient maintained a difficult-to-control hypertension (170–90 mmHg) with the same therapeutic approach, despite normal urinary metanephrine levels (metanephrine 456 nmol/day [90 µg/24h]; normetanephrine 2074 nmol/day [380 µg/24h]; 3-Methoxytyramine 783 nmol/day [261 µg/24h]). Glycemic control had improved (100–170 mg/dL), and the insulin treatment had been switched to a combination of sitagliptin 50 mg/day and an association of metformin 2000 mg/day and dapagliflozin 10 mg/day.

A captopril test revealed primary aldosteronism maintenance (aldosterone lowered from 35.5 ng/dL [0.98 nmol/L] to 34.3 ng/dL [0.95 nmol/L] after 4 hours), and spironolactone was reintroduced, but due to iatrogenic gynecomastia was replaced by eplerenone (50 mg/day) with spontaneous regression of glandular tissue.

In a recent reevaluation 1 year after surgery, he presented a normal-high blood pressure (135–140 mmHg and 85–90 mmHg), medicated with azilsartan 40 mg/day, nifedipine 60 mg/day; eplerenone 100 mg/day; and nebivolol 5 mg/day. Urinary meta-nephrines were negative (metanephrine 684 nmol/day [135 μg/24h], normetanephrine 1583 nmol/day [290 μg/24h], and 3-Methoxytiramine 525 nmol/day [175 μg/24h]). Regarding T2D, his HbA1c was 49.7 mmol/mol (6.7%), maintaining the same therapeutic approach.

Discussion

This report describes a resistant hypertension work-up, in which the case’s complexity was only revealed after the first laboratory results.

Regarding primary aldosteronism, the first laboratory results suggested the diagnosis, revealing spontaneous hypokalemia, low PRA, and an aldosterone higher than 20 ng/dL, and the good blood pressure response after the introduction of spironolactone was as expected. Regarding hypokalemia, it is noteworthy that although it occurs in a minority of patients with primary aldosteronism (9% to 37%) [3], it is frequently observed (87%) [2] when there is concomitant pheochromocytoma.

Due to gynecomastia, spironolactone was later replaced by eplerenone, which is a shorter-acting agent and not so effective in controlling blood pressure as spironolactone but is more specific for the aldosterone receptor and is associated with fewer adverse effects [3].

The coexistence of pheochromocytoma was suggested by elevated fractioned urinary metanephrines, demanding an image identification. The abdominal CT (triphasic acquisition: non-enhanced, portal venous phase and delayed phase) revealed, in addition to 2 lesions compatible with adenomas in the left gland, 2 other indeterminate nodules in the adrenal glands: one in the right and the other in the left gland. Since there were 2 indeterminate nodules, we decided on a functional exam.

In recent studies, Gallium-68 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid–octreotate (Ga-68 DOTATATE) PET/CT has been described as the most sensitive exam (97.6%) and could be considered as a first choice [5]. Since Ga-68 DOTATATE PET/CT was not available, we chose F-18 FDOPA PET/CT, which has 93% sensitivity and 85% specificity for diagnosing pheochromocytoma [6]. This exam showed uptake exclusively in the right adrenal.

Considering the treatment approach, we considered 2 different outcomes. If the right adrenal pheochromocytoma was producing aldosterone-stimulating factors, an adrenalectomy would treat both diseases. But if the primary aldosteronism originated from a contralateral adenoma or a bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, this would remain after the surgical procedure.

In a review by Mao et al including 9 patients [2,7–12], adrenal vein sampling (AVS) confirmed the origin of PA and helped to decide on either unilateral or bilateral adrenalectomy. In the reported case, after a multidisciplinary discussion, it was decided that an AVS would not change the treatment approach for this specific situation. The rationale was that since a right adrenal pheochromocytoma was diagnosed, then performing a right adrenalectomy was mandatory, even if an aldosterone-producing lesion was suspected in the left adrenal gland. In addition, the comorbidities resulting from performing a bilateral adrenalectomy to treat both diseases would likely surpass those of a remaining primary aldosteronism, if proper medicated.

In a retrospective study on the outcome of bilateral adrenalectomy for patients with ectopic Cushing syndrome, Cushing’s disease with failed trans-sphenoidal resection of pituitary tumor, or bilateral primary adrenal hyperplasia, 36.3% of patients developed at least 1 episode of adrenal crisis and an overall mortality rate of 22% was observed [13].

Although some centers have described good outcomes performing a partial adrenalectomy [2,7], which could be an option for a small contralateral aldosterone-producing adenoma, the existence of 3 nodules occupying the left adrenal made this procedure impracticable.

Before surgery, the patient underwent preoperative blockade to prevent perioperative cardiovascular complications and reverse catecholamine-induced blood volume contraction that could lead to severe hypotension after tumor removal [4].

However, as the medication was progressively substituted by a high dose of phenoxybenzamine, there was a marked increase in blood pressure despite the combination with a β-blocker. This could be explained by the presence of primary aldosteronism and the absence of a mineralocorticoid antagonist, as spironolactone was suspended to help prevent volume contraction. When considering the best course of action, instead of choosing a calcium channel blocker or metyrosine, which are both recommended to supplement the combined α- and β-adrenergic blockade protocol [4], we opted for spironolactone. Although this decision may be controversial, as it might have increased the risk of volume depletion, we considered the existence of aldosteronism, and the excellent ambulatory blood pressure profile achieved with this diuretic. In fact, as described, following spironolactone reintroduction, blood pressure control was restored without associated adverse events.

The persistence of high blood pressure after surgery, as was observed, was also described in 6 patients in a review by Mao et al [2,12]. Three patients had bilateral primary aldosteronism, 1 had a contralateral aldosterone-producing adenoma, and 2 did not undergo AVS. Five of these patients required long-term mineralocorticoid receptor blockade.

After confirming hyperaldosteronism persistence with a captopril test, the patient was restarted on eplerenone. After surgery, urinary metanephrines normalized, as observed in 93% patients in the Mao et al review [2,7–12,14].

Glycemic control also improved. The production of catecholamines by pheochromocytomas and their actions in the target receptors can stimulate gluconeogenesis (β-receptors) and decrease insulin release (α-2 receptors), inducing glucose intolerance and T2D [15]. Epinephrine-secreting pheochromocytomas are more likely to induce T2D due their affinity to the β-receptors [15]. Although resecting the pheochromocytoma usually leads to T2D resolution, this was not observed in the present case, despite an improvement on glycemic control, indicating that there were probably other T2D-predisposing factors present.

Conclusions

There are few described cases of concomitant pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism; therefore, there is a lack of specific guidelines to diagnose and manage this rare combination.

Two scenarios should be taken into consideration: an aldosterone-producing pheochromocytoma or 2 separate diseases. For both, the main goal should focus on surgical removal of the pheochromocytoma due to the elevated cardiovascular risk.

A presentation with bilateral nodules may complicate the decision on the best treatment approach. In such cases, a one-side adrenalectomy is the preferable approach, since performing a bilateral adrenalectomy poses a high risk for post-surgical adrenal crisis and the primary aldosteronism can often be controlled with medical therapy.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher

Declaration of Figures’ Authenticity

All figures submitted have been created by the authors who confirm that the images are original with no duplication and have not been previously published in whole or in part.

References:

- 1.Young WF, Calhoun DA, Lenders JWM, et al. Screening for endocrine hypertension: An endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev. 2017;38(2):103–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao JJ, Baker JE, Rainey WE, et al. Concomitant pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism: A case series and literature review. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5(8):1–12. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvab107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funder JW, Carey RM, Mantero F, et al. The management of primary aldosteronism: Case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(5):1889–916. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenders JWM, Duh Q, Eisenhofer G, et al. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(6):1915–42. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janssen I, Chen CC, Millo CM, et al. PET/CT comparing 68 Ga-DOTATATE and other radiopharmaceuticals and in comparison with CT/MRI for the localization of sporadic metastatic pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;43(10):1784–91. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3357-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noordzij W, Glaudemans AWJM, Schaafsma M, et al. Adrenal tracer uptake by 18F-FDOPA PET/CT in patients with pheochromocytoma and controls. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(7):1560–66. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan GH, Carney JA, Grant CS, Young WF., Jr Coexistence of bilateral adrenal phaeochromocytoma and idiopathic hyperaldosteronism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1996;44(5):603–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1996.709530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh BS, Chen FW, Hsu HC, et al. Hyperaldosteronism with coexistence of adrenal cortical adenoma and pheochromocytoma. Taiwan Yi Xue Hui Za Zhi. 1979;78(5):455–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon RD, Bachmann AW, Klemm SA, et al. An association of primary aldosteronism and adrenaline-secreting phaeochromocytoma. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1994;21(3):219–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1994.tb02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyazawa K, Kigoshi T, Nakano S, et al. Hypertension due to coexisting pheochromocytoma and aldosterone-producing adrenal cortical adenoma. Am J Nephrol. 1998;18(6):547–50. doi: 10.1159/000013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakamoto N, Tojo K, Saito T, et al. Coexistence of aldosterone-producing adrenocortical adenoma and pheochromocytoma in an ipsilateral adrenal gland. Endocr J. 2009;56(2):213–19. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k08e-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohta Y, Sakata S, Miyata E, et al. Case report: Coexistence of pheochromocytoma and bilateral aldosterone-producing adenomas in a 36-year-old woman. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:555–57. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prajapati OP, Verma AK, Mishra A, et al. Bilateral adrenalectomy for Cushing’s syndrome: Pros and cons. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(6):834–40. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.167544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wajiki M, Ogawa A, Fukui J, et al. Coexistence of aldosteronoma and pheochromocytoma in an adrenal gland. J Surg Oncol. 1985;28(1):75–78. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930280118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ronen JA, Gavin M, Ruppert MD, Peiris AN. Glycemic disturbances in pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma variable hyperglycemic presentations. Cureus. 2019;11(4):e4551. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]