Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HBV DNA can get integrated into the hepatocyte genome to promote carcinogenesis. However, the precise mechanism by which the integrated HBV genome promotes HCC has not been elucidated.

AIM

To analyze the features of HBV integration in HCC using a new reference database and integration detection method.

METHODS

Published data, consisting of 426 Liver tumor samples and 426 paired adjacent non-tumor samples, were re-analyzed to identify the integration sites. Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38 (GRCh38) and Telomere-to-Telomere Consortium CHM13 (T2T-CHM13 (v2.0)) were used as the human reference genomes. In contrast, human genome 19 (hg19) was used in the original study. In addition, GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend was used to detect HBV integration sites, whereas high-throughput viral integration detection (HIVID) was applied in the original study (HIVID-hg19).

RESULTS

A total of 5361 integration sites were detected using T2T-CHM13. In the tumor samples, integration hotspots in the cancer driver genes, such as TERT and KMT2B, were consistent with those in the original study. GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend detected integrations in more samples than by HIVID-hg19. Enrichment of integration was observed at chromosome 11q13.3, including the CCND1 pro-moter, in tumor samples. Recurrent integration sites were observed in mitochondrial genes.

CONCLUSION

GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend using T2T-CHM13 is accurate and sensitive in detecting HBV integration. Re-analysis provides new insights into the regions of HBV integration and their potential roles in HCC development.

Keywords: Carcinoma, Hepatocellular, Hepatitis B virus, Virus integration

Core Tip: To understand the role of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development, we re-analyzed HBV integration sites using publicly available data. We found that chromosome 11q13.3 is a frequently observed HBV integration site. This region contains important cancer driver genes, such as CCND1 and FGF19, which are amplified in HCC. This finding supports a mechanism of carcinogenesis promoted by HBV-induced genomic instability in the liver and provides insights into treating a subset of liver cancers.

INTRODUCTION

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). When HBV infects liver cells, HBV DNA can be integrated into the human genome. Integration events typically occur during the early stages of an infection[1,2], and are known to promote carcinogenesis via several mechanisms: (1) Increasing the expression levels of neighboring genes; (2) induction of genomic instability and somatic copy number alterations of genes; (3) deletion of tumor suppressor genes through structural mutations[3]; and (4) inducing expression of HBV X protein (HBx) or HBx fusion proteins that contribute to carcinogenesis.

To investigate the effect of HBV on hepatocarcinogenesis, several studies have been conducted using next-generation sequencing technology to identify integration sites of HBV DNA. Examples of such technologies include whole genome sequencing[4] and HBV capture sequencing[5]. These studies revealed frequent integration into the promoter regions of TERT and KMT2B in tumor tissues and FN1 in normal tissues. In an examination of an HBV-infected human-hepatocyte chimeric mouse model, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was thought to be a frequent site of integration[1]. A European study reported a lower frequency of KMT2B insertion and a higher frequency of integration into ADH genes in normal tissues[6].

Most previous studies have used Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37) or human genome 19 (hg19) as the reference genomes. In GRCh37/hg19 and Genome Reference Con-sortium Human Build 38 (GRCh38)[7], tandem repeats, microsatellites, and minisatellites found in telomeres and centromeres remained unresolved. The complete human genome sequence, Telomere-to-Telomere Consortium CHM13 (T2T-CHM13 (v2.0))[8], was released in 2022.

Various methods have been used to detect integration breakpoints. High-throughput viral integration detection (HIVID), a detection method based on a pair-read assembly strategy[9], was applied in the analysis of 426 HCC cases[5]. GRIDSS is a multithreaded structural variant caller from a combination of assembly, split read, and read pair support[10]. VIRUSBreakend utilizes a virus-centric variant calling and assembly approach to identify viral integrations with high sensitivity and low false discovery rate, allowing the identification of integrations in repetitive host regions[11].

Here, we report new features observed by re-analyzing the published data using GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend based on GRCh38 and T2T-CHM13.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequence data were obtained from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) with accession number SRA335342[5]. The dataset consisted of 426 tumor samples and 426 paired adjacent non-tumor samples.

All reads in the dataset were aligned to the GRCh38 and T2T-CHM13 reference genomes using bwa-mem2[12,13]. VIRUSBreakend was used to detect integration sites (Supplementary Figure 1), and the analysis was performed using Nextflow[14] on Amazon Web Service. HBV integration sites were detected using GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend[11]. Integration sites were compared with the count of fragments providing breakend for the variant allele (BVF) in the variant call format files. Statistical analysis and visualization were performed using R software, and statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Comparison of HBV integration sites

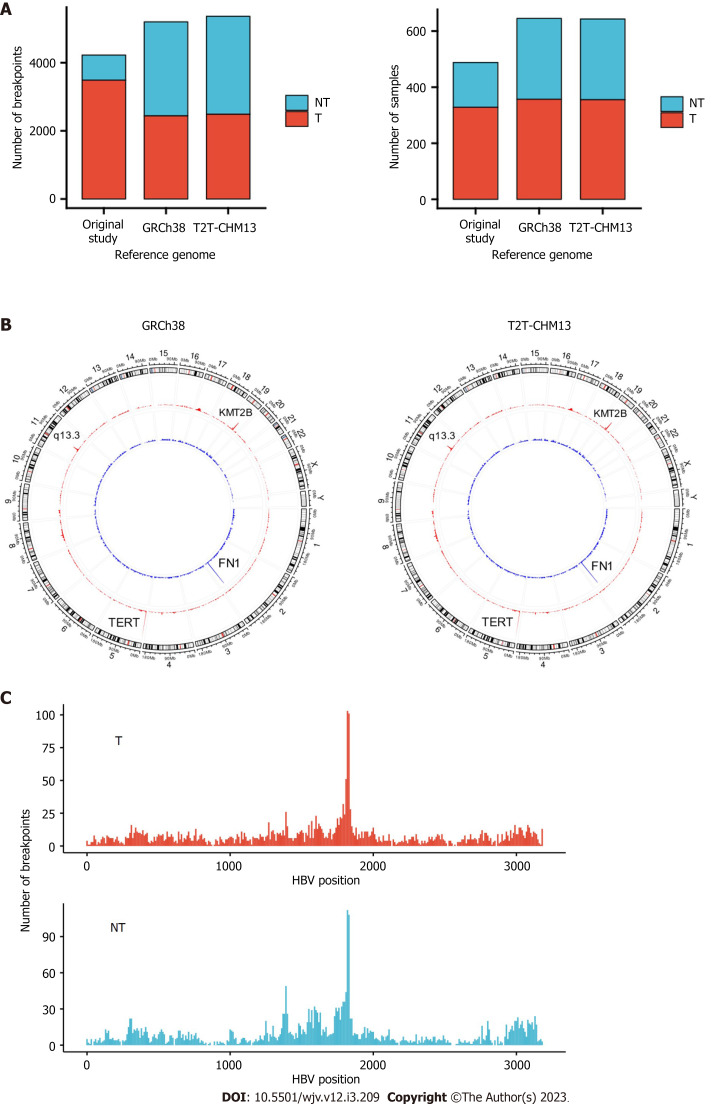

In total, 5361 and 5198 integration breakpoints were detected with T2T-CHM13 and GRCh38, respectively. The breakpoints were similar between the references using GRCh38 and T2T-CHM13 (Figure 1A and B). Consistent with previous studies, integration breakpoints were enriched in the TERT promoter region in tumor samples. In contrast, integration into FN1 was frequently observed in non-tumor samples.

Figure 1.

Hepatitis B virus integration breakpoints across the reference genomes. A: Integration breakpoints in the human reference genomes in tumor and non-tumor samples; B: Circos plot of integration breakpoints. Red represents tumor samples, and blue represents non-tumor samples; C: Hepatitis B virus genome integration breakpoints. T: Tumor; N: Non-tumor.

Compared with the original study, our analysis detected integrations in more samples (357 vs 328 in tumors; 288 vs 160 in non-tumors) (Table 1). In addition, we detected integration in the TERT region in 105 tumor samples, whereas the original study observed integration in 95 tumor samples (Table 2). In contrast, the number of breakpoints detected in tumors was lower than that in the original study (Table 1). In our study, only breakpoints validated by VIRUSBreakend were counted (Supplementary Figure 2). Integration of DDX11L was frequently detected in the original study, but no integration breakpoints were detected in our study (Table 2). The DDX11L gene family is frequently detected as a target for integration using a capture sequencing approach, but it is possible that fragments were mapped incorrectly owing to repetitive sequences[15,16]. In the non-tumor samples, our study detected more integrations, both in the number of samples and breakpoints. For example, we detected 97 integration breakpoints in the FN1 gene from 56 non-tumor samples. The earlier analysis detected only 19 breakpoints from 17 non-tumor samples (Table 2). Few oncogenic regions were affected in the non-tumor samples. Breakpoints were most frequent around direct repeat 1 of the HBV genome (Figure 1C).

Table 1.

Comparison of hepatitis B virus integration breakpoints among reference genomes

|

|

GRCh38

|

T2T-CHM13

|

Original

|

| Tumor | |||

| Number of breakpoints | 2439 | 2487 | 3486 |

| Number of samples | 357 | 355 | 328 |

| Non-tumor | |||

| Number of breakpoints | 2759 | 2874 | 739 |

| Number of samples | 288 | 288 | 160 |

Table 2.

Comparison of frequent integration breakpoints in the samples

|

Gene

|

GRCh38

|

Original

|

||

|

Breakpoints (n)

|

Samples (n)

|

Breakpoints (n)

|

Samples (n)

|

|

| Tumor | ||||

| TERT | 150 | 105 | 160 | 95 |

| KMT2B | 56 | 33 | 55 | 30 |

| DDX11L1 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 23 |

| CCNA2 | 12 | 7 | 14 | 8 |

| CCNE1 | 13 | 9 | 14 | 7 |

| Non-tumor | ||||

| FN1 | 97 | 56 | 19 | 17 |

| TERT | 12 | 10 | 8 | 3 |

| IQGAP2 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| KMT2B | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

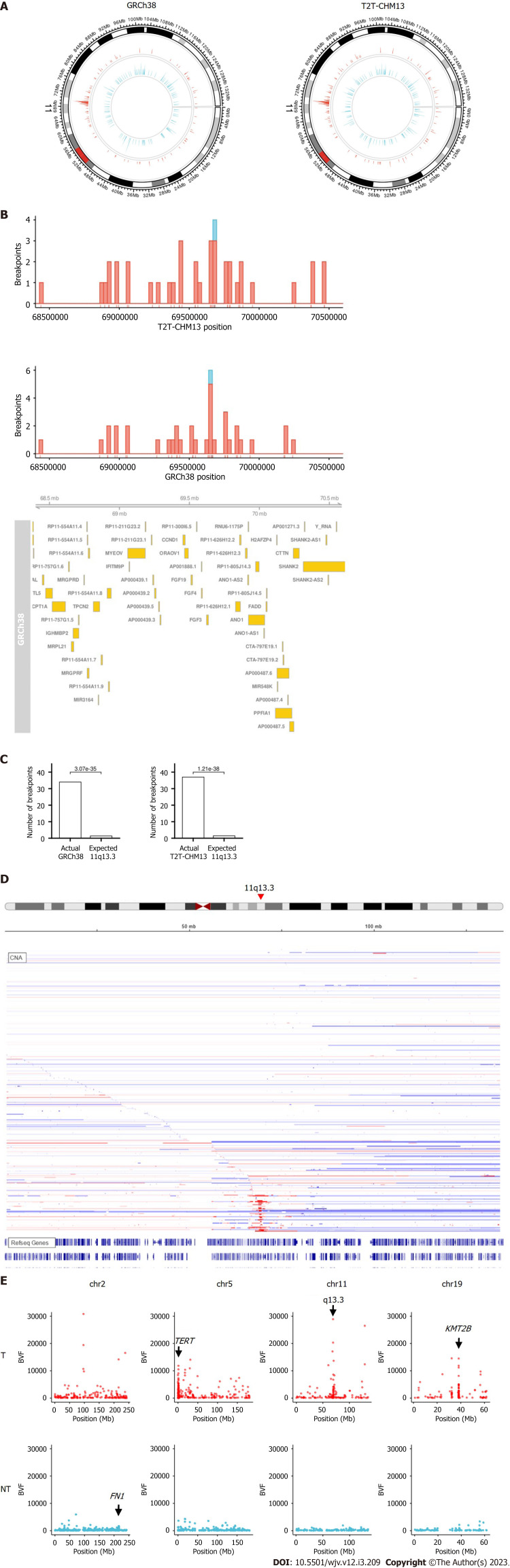

Chromosome 11q13.3 is a frequent site for HBV integration

When the chromosome region was explored, we found that the integration breakpoint at 11q13.3 was enriched with T2T-CHM13 and GRCh38 (Figures 2A-C). Breakpoints at 11q13.3 were more frequent in the tumor samples than in the non-tumor samples (16 (3.8%) of tumor samples compared to 1 (0.02%) of non-tumor samples, Figure 2B). 11q13.3 is characterized by the evolutionarily well-conserved genes CCND1, FGF19, FGF4, and FGF3[17], where copy number amplification frequently occurs in tumors (Figure 2D)[18,19]. Some breakpoints were within the genic and promoter regions of the genes, including CCND1 and FGF4. Integration appeared to be distributed more in the non-genic regions (Figure 2B). When fragments from the integration site were counted using BVF, the values were higher in tumor samples than in non-tumor samples (Figure 2E). High BVF value formed a peak in the 11q13.3 in addition to the peak in the TERT, KMT2B, and CCNE1 genes in the tumor samples (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Integration breakpoints at chromosome 11. A: Circos plot of breakpoints at chromosome 11 in the human reference genomes; B: Integration breakpoints around 11q13.3 in relation to coding genes retrieved from Ensembl. Red represents tumor samples, and blue represents non-tumor samples; C: Comparison of integration breakpoints around 11q13.3 in the tumor samples. Actual represents actual number of integration breakpoints. Expected represents expected number of integration breakpoints assuming random distribution; D: Copy number of liver cancer samples from cBioPortal[18,19]. Red represents amplification, and blue represents deletion. E: Distribution of the number of fragments that provide breakend for the variant allele. T: Tumor; NT: Non-tumor.

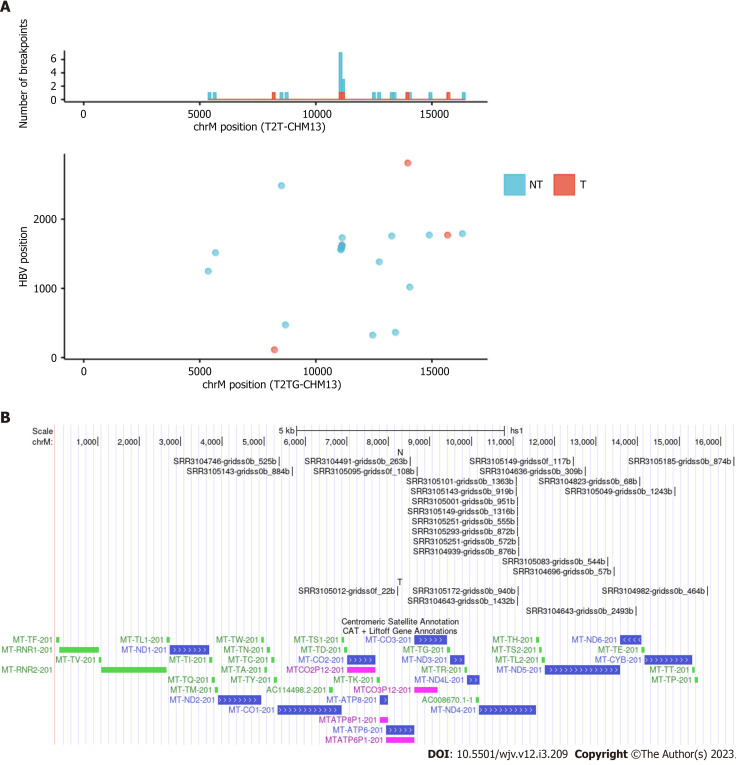

Mitochondrial DNA has sites where HBV DNA is frequently integrated

There is some debate regarding whether mtDNA is a frequent site of HBV integration. A study using a mouse model by Furuta et al[1] found that mtDNA was frequently integrated early in infection. More recently, a preprint suggested that mtDNA is indeed a site for integration[20,21]. Although the original paper on which this study was based did not mention integration into mitochondria, we detected many integration breakpoints into mtDNA and identified repeat integration sites (Table 3 and Figure 3)[22]. Integration breakpoints in mtDNA were observed in both tumor and non-tumor samples. Recurrent integration events were observed in ND4. Of these, eight events were from non-tumor samples, and two from tumor samples. Microhomologous sequences were observed in some regions. For example, the GCCNTTCTCATC sequence, where N represents any nucleotide or gap, was observed at the junction of the ND4 gene (Chromosome M:11079) and the HBV genome (HBV:1559). In contrast, the GCTTCACC sequence was observed at the junction of the ND4 gene (Chromosome M:11104) and the HBV genome (HBV:1590). It is also possible that these integration breakpoints exist in nuclear-mitochondrial segments.

Table 3.

Hepatitis B virus integration breakpoints in mitochondrial DNA

|

Sample

|

Tumor/Non-tumor

|

Chromosome

|

Position

|

HBV

|

Quality score

|

| SRR3104746 | NT | chrM | 5367 | 1247 | 6933.33 |

| SRR3105143 | NT | chrM | 5682 | 1513 | 11817.58 |

| SRR3105012 | T | chrM | 8220 | 112 | 2080.04 |

| SRR3104491 | NT | chrM | 8524 | 2482 | 33322.16 |

| SRR3105095 | NT | chrM | 8694 | 471 | 4209.06 |

| SRR3105101 | NT | chrM | 11079 | 1559 | 2937.33 |

| SRR3105143 | NT | chrM | 11079 | 1559 | 14876.83 |

| SRR3105001 | NT | chrM | 11104 | 1590 | 45538.21 |

| SRR3105149 | NT | chrM | 11104 | 1590 | 16156.63 |

| SRR3105251 | NT | chrM | 11104 | 1590 | 2276.31 |

| SRR3105293 | NT | chrM | 11104 | 1590 | 24562.69 |

| SRR3104643 | T | chrM | 11104 | 1590 | 13683.16 |

| SRR3105172 | T | chrM | 11126 | 1621 | 2610.44 |

| SRR3105251 | NT | chrM | 11130 | 1625 | 6793.43 |

| SRR3104939 | NT | chrM | 11139 | 1729 | 30830.54 |

| SRR3105149 | NT | chrM | 12453 | 323 | 2345.03 |

| SRR3104636 | NT | chrM | 12735 | 1381 | 26840.64 |

| SRR3105083 | NT | chrM | 13273 | 1755 | 4230.85 |

| SRR3104696 | NT | chrM | 13433 | 363 | 2963.36 |

| SRR3104643 | T | chrM | 13964 | 2809 | 2222.86 |

| SRR3104823 | NT | chrM | 14052 | 1017 | 1788.18 |

| SRR3105049 | NT | chrM | 14892 | 1768 | 21102.87 |

| SRR3104982 | T | chrM | 15679 | 1768 | 32371.78 |

| SRR3105185 | NT | chrM | 16319 | 1788 | 2013.53 |

HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

Figure 3.

Integration breakpoints in the mitochondrial genome. A: The upper panel displays integration breakpoints across mitochondrial genomes according to tumor and non-tumor samples, and the lower panel shows integration breakpoints along the human and hepatitis B virus genomes. Red represents tumor samples, and blue represents non-tumor samples; B: Integration breakpoints on the mitochondrial genome annotated using UCSC genome browser (NT: Non-tumor; T: Tumor)[22].

DISCUSSION

In this study, GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend, with an updated human reference genome, was used to detect HBV integration using public sequencing data from liver tumor and non-tumor samples. HBV integration was detected in more samples than in the original analysis (Table 1). The difference in methods could account for the discordant results. We investigated an example of HBV integration sites in the TERT region detected by GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend, but not in the original study (Supplementary Figures 4 and 5). In the original study, the HIVID pipeline, based on paired-end read assembly, was applied to detect integration[9]. In the sequencing data, some paired-end reads could not be assembled because of the absence of overlapping bases. These reads were also included in our analysis to detect integration sites more accurately. It should be noted that the GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend uses genotype D HBV for viral genome reference, whereas genotype C HBV is dominant in the current dataset, which may affect the sensitivity of virus detection.

We found HBV integration clusters in the 11q13.3 region (Figure 2). Unlike previously known single gene integration sites, such as TERT and KMT2B, 11q13.3 spans multiple gene regions. Although these clusters can be observed in the supplemental data of the original paper, to our knowledge, it has not been previously mentioned. Enrichment of 11q13.3 was more significant in tumors than in non-tumor tissues. CCND1, FGF19, FGF4, and FGF3 are located at 11q13.3, where copy number amplification frequently occurs in tumors.

Integration into CCND1, located at 11q13.3, is a potential driver event[23], but its frequency is not high. Although recent studies have not detected integration at 11q13.3[1,6], several studies have detected these events only as supplementary data[4,5,24] and they have been reported since 1988[25,26]. According to a study by Bok et al[27], the expression levels of cancer-related genes, including CCND1 and FGF19, are elevated near the viral integration site on 11q13.3 in an HCC cell line. HBV integration at this locus may be linked to cancer gene activation, as FGF19 amplification was associated with chronic HBV infection[28,29].

HBV integration may be associated with copy number alterations[3]. Chromosomal instability often leads to copy number alterations in the short and long arms of the chromosome. However, 11q13.3 causes strong copy number amplification in a localized region in the middle of the chromosome (Figure 2D). Previous results using whole genome sequencing indicated that the integration allele frequency was high in the tumor samples, especially in the recurrent integration in tumors such as TERT[4]. By comparing fragment counts from the integration site using BVF, the values were found to be higher in the tumor samples than in the non-tumor samples. Some of the integration breakpoints at 11q13.3 had extremely high fragment counts (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figure 3). If BVF correlates with the integration allele frequency, it is possible that these events reflect the clonal expansion of tumors with integration breakpoints or the amplification of integrated genes. CCND1-FGF19 amplification occurred at later points in the evolution of HCC[30]. Further research is needed to investigate the relationships between integration, copy number alteration, and cancer gene activation at 11q13.3.

In our analysis, HBV integration in the mtDNA was observed in 2.3% (20/852) of the samples, and the ND4 gene was a frequent target of HBV integration (Table 3). According to a previous study, HBV integration into mtDNA has occurred in only 0.1% of human clinical liver tissues[1]. Mouse model experiments have suggested that this integration primarily occurs during the early stages of HBV infection through microhomology-mediated end joining[1]. It is also possible that HBV integration occurs in nuclear copies of mtDNA sequences rather than in the mitochondria. Giosa et al[21] detected HBV integration in DNA isolated from mitochondria. The D-loop region is the target of HBV integration. Our analysis suggests that ND4 genes may also be targeted for integration through microhomology-mediated mechanisms.

This study has several limitations. First, the analysis was conducted using existing data and the findings were not validated using independent data. Second, the original data were based on HBV capture sequencing, and gene copy numbers were not available. Finally, the integration data were obtained from short-read sequencing and have not been validated using long-read sequencing data.

CONCLUSION

HBV integration in HCC samples has been characterized using the complete human reference. GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend using T2T-CHM13 is accurate and sensitive in detecting HBV integration. HBV frequently integrates at the 11q13.3 region, where the CCND1 gene is located, and this region is frequently amplified in several types of cancer, including HCC. Further research is needed to examine how HBV integration interacts with driver gene expression and copy number alteration.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Many hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infected patients suffer from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), but a little focus is given to detect HBV integration pattern in the treatment of HCC. Detection of HBV integration can be improved by introducing a reliable detection method.

Research motivation

HBV frequently integrates at the 11q13.3 region, where the CCND1 gene is located, and this region is frequently amplified in several types of cancer, including HCC.

Research objectives

We aimed to analyze the features of HBV integration in HCC using a new reference database and integration detection method.

Research methods

Published data, consisting of 426 liver tumor samples and 426 paired adjacent non-tumor samples, were re-analyzed to identify the integration sites. Updated human reference genomes, Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38 (GRCh38), and Telomere-to-Telomere Consortium CHM13 (T2T-CHM13 (v2.0)) were used. In addition, GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend, which utilizes a virus-centric variant calling and assembly approach, was used to detect HBV integration sites.

Research results

A total of 5361 integration sites were detected using T2T-CHM13. In the tumor samples, integration hotspots in the cancer driver genes, such as TERT and KMT2B, were consistent with those in the original study. GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend detected integrations in more samples than original analysis. Enrichment of integration was observed at chromosome 11q13.3, including the CCND1 promoter, in tumor samples. Recurrent integration sites were observed in mitochondrial genes.

Research conclusions

GRIDSS VIRUSBreakend using T2T-CHM13 is accurate and sensitive in detecting HBV integration and provides new insights into the regions of HBV integration and their potential roles in HCC development.

Research perspectives

Further research is needed to examine how HBV integration interacts with driver gene expression and copy number alteration.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study is not applicable as it is a re-analysis of publicly available data.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

ARRIVE guidelines statement: The authors have read the ARRIVE guidelines, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the ARRIVE guidelines.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: December 28, 2022

First decision: January 17, 2023

Article in press: April 12, 2023

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chaturvedi HTC, India; Zhao G, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Chen YX

Contributor Information

Ryuta Kojima, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Shingo Nakamoto, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan. nakamotoer@faculty.chiba-u.jp.

Tadayoshi Kogure, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Yaojia Ma, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Keita Ogawa, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Terunao Iwanaga, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Na Qiang, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Junjie Ao, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Ryo Nakagawa, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Ryosuke Muroyama, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Masato Nakamura, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Tetsuhiro Chiba, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Jun Kato, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Naoya Kato, Department of Gastroenterology, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8670, Japan.

Data sharing statement

All the data supporting this study are stored in the SRA database with accession number SRA335342.

References

- 1.Furuta M, Tanaka H, Shiraishi Y, Unida T, Imamura M, Fujimoto A, Fujita M, Sasaki-Oku A, Maejima K, Nakano K, Kawakami Y, Arihiro K, Aikata H, Ueno M, Hayami S, Ariizumi SI, Yamamoto M, Gotoh K, Ohdan H, Yamaue H, Miyano S, Chayama K, Nakagawa H. Characterization of HBV integration patterns and timing in liver cancer and HBV-infected livers. Oncotarget. 2018;9:25075–25088. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chauhan R, Michalak TI. Earliest hepatitis B virus-hepatocyte genome integration: Sites, mechanism, and significance in carcinogenesis. Hepatoma Research. 2021;7:20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Álvarez EG, Demeulemeester J, Otero P, Jolly C, García-Souto D, Pequeño-Valtierra A, Zamora J, Tojo M, Temes J, Baez-Ortega A, Rodriguez-Martin B, Oitaben A, Bruzos AL, Martínez-Fernández M, Haase K, Zumalave S, Abal R, Rodríguez-Castro J, Rodriguez-Casanova A, Diaz-Lagares A, Li Y, Raine KM, Butler AP, Otero I, Ono A, Aikata H, Chayama K, Ueno M, Hayami S, Yamaue H, Maejima K, Blanco MG, Forns X, Rivas C, Ruiz-Bañobre J, Pérez-Del-Pulgar S, Torres-Ruiz R, Rodriguez-Perales S, Garaigorta U, Campbell PJ, Nakagawa H, Van Loo P, Tubio JMC. Aberrant integration of Hepatitis B virus DNA promotes major restructuring of human hepatocellular carcinoma genome architecture. Nat Commun. 2021;12:6910. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26805-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung WK, Zheng H, Li S, Chen R, Liu X, Li Y, Lee NP, Lee WH, Ariyaratne PN, Tennakoon C, Mulawadi FH, Wong KF, Liu AM, Poon RT, Fan ST, Chan KL, Gong Z, Hu Y, Lin Z, Wang G, Zhang Q, Barber TD, Chou WC, Aggarwal A, Hao K, Zhou W, Zhang C, Hardwick J, Buser C, Xu J, Kan Z, Dai H, Mao M, Reinhard C, Wang J, Luk JM. Genome-wide survey of recurrent HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2012;44:765–769. doi: 10.1038/ng.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhao LH, Liu X, Yan HX, Li WY, Zeng X, Yang Y, Zhao J, Liu SP, Zhuang XH, Lin C, Qin CJ, Zhao Y, Pan ZY, Huang G, Liu H, Zhang J, Wang RY, Wen W, Lv GS, Zhang HL, Wu H, Huang S, Wang MD, Tang L, Cao HZ, Wang L, Lee TL, Jiang H, Tan YX, Yuan SX, Hou GJ, Tao QF, Xu QG, Zhang XQ, Wu MC, Xu X, Wang J, Yang HM, Zhou WP, Wang HY. Genomic and oncogenic preference of HBV integration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12992. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Péneau C, Imbeaud S, La Bella T, Hirsch TZ, Caruso S, Calderaro J, Paradis V, Blanc JF, Letouzé E, Nault JC, Amaddeo G, Zucman-Rossi J. Hepatitis B virus integrations promote local and distant oncogenic driver alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2022;71:616–626. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-323153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider VA, Graves-Lindsay T, Howe K, Bouk N, Chen HC, Kitts PA, Murphy TD, Pruitt KD, Thibaud-Nissen F, Albracht D, Fulton RS, Kremitzki M, Magrini V, Markovic C, McGrath S, Steinberg KM, Auger K, Chow W, Collins J, Harden G, Hubbard T, Pelan S, Simpson JT, Threadgold G, Torrance J, Wood JM, Clarke L, Koren S, Boitano M, Peluso P, Li H, Chin CS, Phillippy AM, Durbin R, Wilson RK, Flicek P, Eichler EE, Church DM. Evaluation of GRCh38 and de novo haploid genome assemblies demonstrates the enduring quality of the reference assembly. Genome Res. 2017;27:849–864. doi: 10.1101/gr.213611.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nurk S, Koren S, Rhie A, Rautiainen M, Bzikadze AV, Mikheenko A, Vollger MR, Altemose N, Uralsky L, Gershman A, Aganezov S, Hoyt SJ, Diekhans M, Logsdon GA, Alonge M, Antonarakis SE, Borchers M, Bouffard GG, Brooks SY, Caldas GV, Chen NC, Cheng H, Chin CS, Chow W, de Lima LG, Dishuck PC, Durbin R, Dvorkina T, Fiddes IT, Formenti G, Fulton RS, Fungtammasan A, Garrison E, Grady PGS, Graves-Lindsay TA, Hall IM, Hansen NF, Hartley GA, Haukness M, Howe K, Hunkapiller MW, Jain C, Jain M, Jarvis ED, Kerpedjiev P, Kirsche M, Kolmogorov M, Korlach J, Kremitzki M, Li H, Maduro VV, Marschall T, McCartney AM, McDaniel J, Miller DE, Mullikin JC, Myers EW, Olson ND, Paten B, Peluso P, Pevzner PA, Porubsky D, Potapova T, Rogaev EI, Rosenfeld JA, Salzberg SL, Schneider VA, Sedlazeck FJ, Shafin K, Shew CJ, Shumate A, Sims Y, Smit AFA, Soto DC, Sović I, Storer JM, Streets A, Sullivan BA, Thibaud-Nissen F, Torrance J, Wagner J, Walenz BP, Wenger A, Wood JMD, Xiao C, Yan SM, Young AC, Zarate S, Surti U, McCoy RC, Dennis MY, Alexandrov IA, Gerton JL, O'Neill RJ, Timp W, Zook JM, Schatz MC, Eichler EE, Miga KH, Phillippy AM. The complete sequence of a human genome. Science. 2022;376:44–53. doi: 10.1126/science.abj6987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li W, Zeng X, Lee NP, Liu X, Chen S, Guo B, Yi S, Zhuang X, Chen F, Wang G, Poon RT, Fan ST, Mao M, Li Y, Li S, Wang J, Jianwang. Xu X, Jiang H, Zhang X. HIVID: an efficient method to detect HBV integration using low coverage sequencing. Genomics. 2013;102:338–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron DL, Baber J, Shale C, Valle-Inclan JE, Besselink N, van Hoeck A, Janssen R, Cuppen E, Priestley P, Papenfuss AT. GRIDSS2: comprehensive characterisation of somatic structural variation using single breakend variants and structural variant phasing. Genome Biol. 2021;22:202. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02423-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cameron DL, Jacobs N, Roepman P, Priestley P, Cuppen E, Papenfuss AT. VIRUSBreakend: Viral Integration Recognition Using Single Breakends. Bioinformatics. 2021;37:3115–3119. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. e-pub ahead of print 2013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasimuddin Md, Misra S, Li H, Aluru S. Efficient Architecture-Aware Acceleration of BWA-MEM for Multicore Systems. In: 2019 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS). Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: IEEE, 2019: 314–324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Tommaso P, Chatzou M, Floden EW, Barja PP, Palumbo E, Notredame C. Nextflow enables reproducible computational workflows. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:316–319. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tatsuno K, Midorikawa Y, Takayama T, Yamamoto S, Nagae G, Moriyama M, Nakagawa H, Koike K, Moriya K, Aburatani H. Impact of AAV2 and Hepatitis B Virus Integration Into Genome on Development of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Prior Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:6217–6227. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-4041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Midorikawa Y, Tatsuno K, Moriyama M. Genome-wide analysis of hepatitis B virus integration in hepatocellular carcinoma: Insights next generation sequencing. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2021;10:548–552. doi: 10.21037/hbsn-21-228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katoh M, Katoh M. Evolutionary conservation of CCND1-ORAOV1-FGF19-FGF4 Locus from zebrafish to human. Int J Mol Med. 2003;12:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, Jacobsen A, Byrne CJ, Heuer ML, Larsson E, Antipin Y, Reva B, Goldberg AP, Sander C, Schultz N. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, Cerami E, Sander C, Schultz N. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Science Signaling. 2013:6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giosa D, Lombardo D, Musolino C, Chines V, Raffa G, Tocco FC di, D’Aliberti D, Caminiti G, Saitta C, Alibrandi A, Cigliano RA, Romeo O, Navarra G, Raimondo G, Pollicino T. Mitochondrial DNA is a frequent target of HBV integration. In Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giosa D, Lombardo D, Musolino C, Chines V, Raffa G, Casuscelli di Tocco F, D’Aliberti D, Saitta C, Alibrandi A, Aiese Cigliano R, Romeo O, Navarra G, Raimondo G, Pollicino T. A new high-throughput HBV integration sequencing approach shows that mitochondrial DNA is frequently targeted by virus integration in liver cells with active HBV replication. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:S8–S9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler D. The human genome browser at UCSC. Genome Res. 2002;12:996–1006. doi: 10.1101/gr.229102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Comprehensive and Integrative Genomic Characterization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cell. 2017;169:1327–1341.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoo S, Wang W, Wang Q, Fiel MI, Lee E, Hiotis SP, Zhu J. A pilot systematic genomic comparison of recurrence risks of hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma with low- and high-degree liver fibrosis. BMC Med. 2017;15:214. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0973-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatada I, Tokino T, Ochiya T, Matsubara K. Co-amplification of integrated hepatitis B virus DNA and transforming gene hst-1 in a hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 1988;3:537–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokino T, Matsubara K. Chromosomal sites for hepatitis B virus integration in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Virol. 1991;65:6761–6764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6761-6764.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bok J, Kim KJ, Park MH, Cho SH, Lee HJ, Lee EJ, Park C, Lee JY. Identification and extensive analysis of inverted-duplicated HBV integration in a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. BMB Rep. 2012;45:365–370. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2012.45.6.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn SM, Jang SJ, Shim JH, Kim D, Hong SM, Sung CO, Baek D, Haq F, Ansari AA, Lee SY, Chun SM, Choi S, Choi HJ, Kim J, Kim S, Hwang S, Lee YJ, Lee JE, Jung WR, Jang HY, Yang E, Sung WK, Lee NP, Mao M, Lee C, Zucman-Rossi J, Yu E, Lee HC, Kong G. Genomic portrait of resectable hepatocellular carcinomas: implications of RB1 and FGF19 aberrations for patient stratification. Hepatology. 2014;60:1972–1982. doi: 10.1002/hep.27198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang HJ, Haq F, Sung CO, Choi J, Hong SM, Eo SH, Jeong HJ, Shin J, Shim JH, Lee HC, An J, Kim MJ, Kim KP, Ahn SM, Yu E. Characterization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients with FGF19 Amplification Assessed by Fluorescence in situ Hybridization: A Large Cohort Study. Liver Cancer. 2019;8:12–23. doi: 10.1159/000488541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou SL, Zhou ZJ, Song CL, Xin HY, Hu ZQ, Luo CB, Luo YJ, Li J, Dai Z, Yang XR, Shi YH, Wang Z, Huang XW, Fan J, Zhou J. Whole-genome sequencing reveals the evolutionary trajectory of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma early recurrence. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:24. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00838-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All the data supporting this study are stored in the SRA database with accession number SRA335342.