Abstract

The majority of patients affected by Crohn’s disease (CD) develop a chronic condition with persistent inflammation and relapses that may cause progressive and irreversible damage to the bowel, resulting in stricturing or penetrating complications in around 50% of patients during the natural history of the disease. Surgery is frequently needed to treat complicated disease when pharmacological therapy failes, with a high risk of repeated operations in time. Intestinal ultrasound (IUS), a non-invasive, cost-effective, radiation free and reproducible method for the diagnosis and follow-up of CD, in expert hands, allow a precise assessment of all the disease manifestations: Bowel characteristics, retrodilation, wrapping fat, fistulas and abscesses. Moreover, IUS is able to assess bowel wall thickness, bowel wall stratification (echo-pattern), vascularization and elasticity, as well as mesenteric hypertrophy, lymph-nodes and mesenteric blood flow. Its role in the disease evaluation and behaviour description is well assessed in literature, but less is known about the potential space of IUS as predictor of prognostic factors suggesting response to a medical treatment or postoperative recurrence. The availability of a low cost exam as IUS, able to recognize which patients are more likely to respond to a specific therapy and which patients are at high risk of surgery or complications, could be a very useful instrument in the hands of IBD physician. The aim of this review is to present current evidence about the prognostic role that IUS can show in predicting response to treatment, disease progression, risk of surgery and risk of post-surgical recurrence in CD.

Keywords: Intestinal ultrasound, Crohn’s disease, Postoperative recurrence, Bowel wall thickness, Remission, Intestinal surgery

Core Tip: Intestinal ultrasound (IUS) and magnetic resonance enterography are better tolerated and safer than endoscopy, with IUS more easily available and less expensive than magnetic resonance imaging. Moreover, IUS allows complete visualization of the small-bowel even in patients with stenoses and/or severe inflammation, and can assess for extraintestinal disease. In addition, IUS may predict outcomes better than endoscopic mucosal assessment, possibly identifying more relevant therapeutic targets. This review discusses the role of IUS in Crohn’s disease not only as first line investigation but as an extremely useful instrument in predicting response to medical treatment, disease evolution and risk of recurrence before and after surgery.

INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory condition that can affect the whole gastrointestinal tract, more frequently involving the ileum and colon, usually presenting in its active phases with abdominal pain, diarrhoea (bloody or non-bloody), urgency, fatigue and weight loss[1]. The majority of patients affected by CD show chronic relapsing disease with potential chronic continuous abdominal symptoms after diagnosis[2].

The available treatments often fail to achieve disease remission or lose their efficacy over time. Moreover, in CD, chronic inflammation and relapses may cause progressive and irreversible damage to the bowel[3], which results in stricturing or penetrating complications in approximately 50% of patients during the natural history of the disease, with a high risk of surgery or repeated surgery[4].

It has been realized that patients’ symptoms in CD do not necessarily reflect the underlying inflammatory burden of the disease and that, independent of clinical symptoms, patients can have different rates of disease progression and outcomes[2]. Most CD patients at the time of diagnosis have a disease with inflammatory features, but in some patients, it can evolve to a stenosing or penetrating pattern during follow-up[5]. Therefore, the possibility of identifying which patients are nonresponsive to medical treatment and prone to develop stricturing and penetrating CD would be very important to properly address the treatment. Prognostic factors for favourable or unfavourable outcomes of CD have been extensively researched and assessed with both invasive and noninvasive methods.

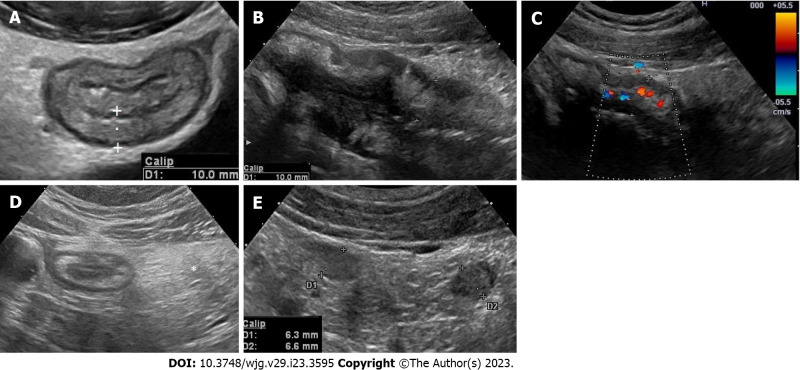

Intestinal ultrasound (IUS) is a non-invasive, cost-effective, radiation free and reproducible method for the diagnosis and follow-up of CD, with an accuracy comparable to magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography[6,7]. IUS can assess several features of the bowel wall and surrounding tissue: Bowel wall thickness (BWT) (Figure 1A), bowel wall stratification (echo-pattern) (Figure 1B), vascularization (Figure 1C) and elasticity, as well as mesenteric hypertrophy (Figure 1D), lymph-nodes (Figure 1E) and mesenteric blood flow. IUS is also able to assess complications such as stenosis, dilations, fistulas and abscesses[8]. During the follow-up of CD patients undergoing biological therapy, IUS features have been correlated with clinical activity, endoscopic activity, laboratory markers (faecal calprotectin and C-reactive protein) and drug serum levels[9-13]. However, IUS specific features have also been suggested as predictive factors for evaluating the response to medical treatment, the risk of clinical relapse or surgery, and the risk of postoperative recurrence[14-17]. We present the current evidence on the prognostic value of IUS and especially the IUS features of the bowel wall in predicting response to treatment and risk of relapse in CD.

Figure 1.

Intestinal ultrasound assess several features of the bowel wall and surrounding tissue. A: Bowel wall thickness should be measured perpendicular to the anterior wall of the bowel (or where it is better visible) avoiding haustrations and mucosal folds. The cursor/calipers should be placed at the end of the interface echo between the serosa and the proper muscle to the start of the interface echo between the lumen and the mucosa; B: Bowel wall stratification. The wall layers in case of active disease may appear focally or extensively disrupted (disrupted or hypoechoic echo pattern); C: Bowel wall vascularity. Bowel wall vascularity can be determined both by colour Doppler or power Doppler signal at the level of the most thickened segments, using special presets optimized for slow flow detection; D: Mesenteric hypertrophy. Mesenteric hypertrophy also called fat wrapping or creeping fat appears on ultrasound (US) as hyperechoic tissue or “mass effect” encircling the diseased bowel; E: Lymphnodes. Enlarged inflammatory mesenteric lymph nodes related to Crohn’s disease are usually described at US as oval or elongated with lesser diameter > 5 mm and seem to be correlated with young age, early disease, or disease with shorter duration, and with the presence of fistulae and abscesses.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Search strategy and selection criteria

Two authors (Manzotti C and Maconi G) searched the literature using the PubMed database from January 2000 to January 2022. The search used the following terms in different combinations: “intestinal ultrasound”, “bowel ultrasound”, “transabdominal ultrasound”, “IUS”, “bowel wall thickness”, “Doppler”, “CEUS”, “transmural healing”, “Crohn”, “Crohn’s disease”, “IBD”, “inflammatory bowel disease”, “surgery”, “clinical remission”, “remission”, “predictive value”, “outcome”, and “post-surgical recurrence”. In particular, the following string was used: [(ultrasound OR sonography) AND (bowel OR intestinal) AND (Crohn’s disease OR IBD) AND (remission OR response OR transmural OR outcome OR predictive)].

Additional potentially eligible articles were manually searched through the bibliography of relevant articles. Eligible articles were randomized controlled trials, prospective or retrospective cohort studies, reviews, and systematic reviews with a meta-analysis; duplications and studies in languages other than English were excluded. In each eligible paper, we searched for information on the predictive value of IUS for patients affected by active or quiescent CD in terms of response to treatment, disease course, transmural healing, risk of surgery, and risk of postsurgical recurrence. Two authors (Manzotti C and Maconi G) screened the title and abstract of potentially eligible papers, followed by a full-text analysis of relevant articles. Starting from a total of 1040 articles, 49 were considered suitable and were included in this review.

DISCUSSION

Active disease

Intestinal US, before and early after the start of biologic treatment, showed high accuracy in predicting long-term clinical and endoscopic remission and response[17,18]. Although few data have shown that pretreatment IUS features may predict the outcome and somewhat drive the choice of treatment, much more data have shown that sonographic improvement of BWT, echopattern and vascularization as early as weeks 2-4 of biologic treatment may predict a better long-term response compared to those of patients without an early treatment response[19]. Studies considering predictive value of IUS parameters for response to treatment and course of CD are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Predictive value of intestinal ultrasound parameters for response to treatment and course of Crohn’s disease

|

Ref.

|

Treatment

|

Timing of IUS after start of treatment

|

IUS parameter

|

Predictive value for

|

| Albshesh et al[18], 2020 | Anti-TNF | > 14 wk | BWT > 4 mm | Treatment failure |

| BWT < 4 mm | Duration of failure-free response | |||

| Calabrese et al[52], 2022 | Anti-TNF, vedolizumab, ustekinumab | Baseline | “Higher BWT” | Low risk of TR |

| Colonic localization | High risk of TR | |||

| Chen et al[19], 2022 | Anti-TNF | Baseline-2 wk | Reduction in BWT, vascularization, SWE | Response to treatment |

| De Voogd et al[17], 2022 | Anti-TNF | Baseline-4/8 wk | BWT reduction > 18% | Endoscopic response and remission at 12-34 wk |

| Helwig et al[32], 2022 | All available biological therapies | Baseline-12 wk | BWT reduction > 25% | Clinical remission and no therapy change at 52 wk |

| Les et al[20], 2021 | 5-ASA, budesonide, AZA, anti TNF | Worsened BWT, echopattern, vascularization | Need for treatment escalation, negative disease course | |

| Orlando et al[29], 2018 | Anti-TNF | Baseline | SWE strain ratio > 2 | Surgery |

| Paredes et al[53], 2019 | Anti-TNF | 12 wk | BWT ≤ 3 mm | “Good outcome” (no treatment intensification, no surgery) at 1 yr |

| Ripollés et al[21], 2016 | Anti-TNF | Baseline-12 wk | Sonographic response (BWT decrease > 2 mm, diminution of one grade of ECD, decrease > 20% of mural enhancement, disappearance of transmural complications or stenosi | 1-yr sonographic response and further 1-yr clinical response and treatment efficacy |

| Smith et al[22], 2022 | All available biological therapies and thiopurines | Baseline-14 wk | Sonographic response (BWT decreasing > 0.5 mm and vascularity improvement by ≥ one grade) | Treatment response at 46 wk |

| Zorzi et al[23], 2020 | Anti-TNF, budesonide, thiopurines | Baseline-18 mo | Normalization of SICUS (BWT, disease extension, complications) | Long term lower cumulative probability of need for surgery, hospitalization, and need for steroids |

| Laterza et al[54], 2021 | Anti-TNF | 12 wk | CEUS increased PI and Pw | Clinical relapse within 6 mo |

| Ungar et al[55], 2020 | Adalimumab | NA | Terminal ileum BWT < 4 mm | Therapy retention |

| Quaia et al[56], 2019 | Anti-TNF | Baseline-6 wk | CEUS pretreatment values and % variations of peak enhancement, AUC, AUC during wash-in, AUC during wash-out | Long term response to therapy |

IUS: Intestinal ultrasound; BWT: Bowel wall thickness; ECD: Eco-color-doppler; SWE: Shear wave elastography; UEI: Ultrasound elastography imaging; TR: Transmural remission; CEUS: Contrast enhanced ultrasound; AUC: Area under the curve; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; NA: Not available; 5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylic acid; AZA: Azacitidine.

Intestinal US to predict response to treatment and disease course

Increased BWT and bowel wall vascularity assessed by colour Doppler or IV contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS), variably powered in bowel US scores, was identified as an independent predictor of a negative disease course, namely, the need for steroids, change of therapy, treatment intensification, hospitalization, or need for surgery through 6-12 mo[20,14]. In addition, increased echopatterns coupled with disrupted echopatterns of the bowel wall or lack of bowel wall stratification were independent predictors for the need for subsequent therapeutic optimization[20].

Sonographic response and clinical response

It seems that sonographic response after 12 or 14 wk of therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drugs predicts the 1-year sonographic response, which in turn correlates with the 1-year clinical response, predicts efficacy of further treatment and inversely correlated with the need for surgery. Stricturing behaviour, namely, the detection of strictures with prestenotic dilatation, seems to be the only sonographic feature associated with a long-term negative predictive value of clinical response[21,22].

Similar results were demonstrated by using small intestinal contrast US (SICUS), which is used to monitor patients undergoing anti-TNF therapy. An improvement in BWT, a reduction of disease extension, or the absence of intestinal complications as detected by SICUS predicted a better response after 1 year of therapy, as well as a reduction in steroid therapy and hospital admissions[23].

Monitoring BWT with IUS also showed predictive value for patients starting therapy with ustekinumab. A decrease in BWT > 1 mm at week 8 after the start of therapy was a helpful parameter for selecting patients with an early response to ustekinumab and for providing assistance in terms of further treatment intervals[24]. The thickening of each single layer of the bowel wall and its clinical significance in CD have been poorly investigated thusfar. It seems that the thickening of the proper muscle layer in active CD patients is correlated with poor clinical and sonographic responses to vedolizumab treatment[25]. In this regard, smooth muscle hyperplasia has been underlined as a central contributor to the stricturing phenotype, whereas fibrosis is less significant, and the ‘inflammation-smooth muscle hyperplasia axis’ seems to be the most important step in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s strictures[26].

Additionally, the assessment of bowel wall vascularity by CEUS seems to provide relevant prognostic information regarding treatment efficacy in patients with CD. The improvement of several perfusion parameters, such as peak contrast enhancement, rate of wash-in and wash-out and the area under the time intensity curve of the intestinal wall 4-6 wk after starting anti-inflammatory treatment (anti-TNF-alpha), were correlated with a favourable response[25,27,28]. Finally, the evaluation of ultrasound elasticity of the bowel wall may have a predictive role as well, correlating with therapeutic outcomes for CD patients treated with anti-TNF[29].

With regard to extra bowel findings, especially mesenteric lymphadenopathy and mesenteric fat hypertrophy, their prognostic role in response to treatment remains controversial. Regional mesenteric lymphadenopathy detected by IUS is a common but nonspecific sonographic finding in early CD and could be linked to young age, early disease, and the presence of abscesses or fistulae[30]. However, its prognostic significance remains poorly investigated. Mesenteric fat hypertrophy is associated with clinical and biochemical disease activity, and it may disappear or improve in patients who have responded to medical treatment[31]. However, its prognostic value in predicting response to therapy and risk of relapse is debatable[16,31].

IUS to predict transmural remission

Transmural remission (TR) or transmural healing with different definitions in literature, is now considered as an objective and relevant target in CD. It may be assessed by IUS taking into account BWT normalization (≤ 3 mm) with or without normalization of Doppler vascular signs and peri-intestinal inflammatory signs[32]. It is correlated with improved clinical outcome, such as a reduced demand of medication escalation, corticosteroid use, hospitalization and CD-related surgery.

The rate of TR, with more or less extensive definitions, in patients undergoing biological therapy was obtained from 12% to 46.2% of patients after 12 wk to 2 years of therapy (see Table 2). TR was strictly correlated with time, being higher at later assessments compared with early assessments. Moreover, it is more prevalent in colic CD than in ileal CD and it is associated with lower BWT and lower shear wave elastography strain ratio at baseline (see Table 2). However, a few studies have evaluated baseline or early IUS factors predictive of TR. Further prospective trials are needed to reach more consistent evidence on IUS predictive value, to help in properly selecting the right treatment for the right CD patient and plain maintenance therapy.

Table 2.

Rate of transmural remission and intestinal ultrasound parameters predictive of transmural remission in Crohn’s disease patients treated with biologics

|

Ref.

|

Patients, n

|

TR definition

|

Study drug

|

Treatment duration

|

Rate of TR

|

IUS parameters predictive of TR

|

| Calabrese et al[52], 2022 | 188 | Normalization of BWT, no ECD, no extra bowel signs of inflammation | Adalimumab, infliximab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab | 52 wk | 27.5% (26.8% adalimumab; 37% infliximab; 27.2% vedolizumab; 20% ustekinumab | Colonic localization, lower BWT at baseline |

| Castiglione et al[57], 2013 | 66 | NA | Anti-TNF | 2 yr | 25% | |

| 67 | Thiopurines | 4% | ||||

| Castiglione et al[58], 2017 | 40 | BWT ≤ 3 mm | Anti-TNF | 2 yr | 25% | |

| Castiglione et al[59], 2019 | 218 | BWT ≤ 3 mm | Anti-TNF | 12 wk | 31.2% | |

| Helwig et al[32], 2022 | 180 | BWT ≤ 2 mm terminal ileum or ≤ 3 mm colon; BWT ≤ 2 mm terminal ileum or ≤ 3 mm colon + two factors among no ECD, no fibrofatty proliferation, normal stratification; normalization of all parameters | All available biologics | 12 wk | 33.3%; 38.5%; 24.4% (18.4% I; 29% C) | |

| 78 | 46 wk | 46.2%; NA; NA | ||||

| Kucharzik et al[60], 2023 | 77 | Normalization of all IUS parameters | Ustekinumab | 48 wk | 24.1% (13.2% I; 50.0% C) | |

| Miranda et al[61], 2021 | 35 | BWT ≤ 3 mm | Ustekinumab | 52 wk | 31.4% | |

| Orlando et al[29], 2018 | 30 | BWT ≤ 3 mm | Anti-TNF | 14 wk | 29% | UEI strain ratio |

| 52 wk | 30% | |||||

| Paredes et al[53], 2019 | 36 | BWT ≤ 3 mm | Anti-TNF | 52 wk | 39% | |

| Ripollés et al[21], 2016 | 51 | BWT ≤ 3 mm, no ECD, absence of complications | Anti-TNF | 12 wk | 14% | |

| 52 wk | 29.5% | |||||

| Civitelli et al[62], 2016 | 32 | BWT < 3 mm, no ECD, normal stratification, absence of strictures and dilatation | Anti-TNF | 9-12 mo | 14% | |

| Paredes et al[63], 2010 | 24 | BWT < 3 mm, no increased ECD | Anti-TNF | 2 wk | 20.8% | |

| Vaughan et al[64], 2022 | 79 | BWT ≤ 3 mm, no increased ECD | Infliximab | 12 wk | 41% | |

| Han et al[65], 2022 | 92 | BWT ≤ 3 mm, no increased ECD | Anti-TNF | 14 wk | 12% | |

| 52 wk (only 22 patients) | 22.7% | |||||

| Dolinger et al[66], 2021 | 13 | BWT ≤ 3 mm | Infliximab | 14 wk | 23% | |

| Zorzi et al[23], 2020 | 80 | SICUS normal value for BWT, absence of any length of disease, and absence of perienteric inflammation, fistulas, phlegmon, or abscess) | Anti-TNF, budesonide, thiopurines | 18 mo | 41% |

TR: Transmural remission; BWT: Bowel wall thickness; ECD: Eco-color-doppler vascular signal; I: Ileal Crohn’s disease; C: Colonic Crohn’s disease; UEI: Ultrasound elastography imaging; SICUS: Small intestine contrast ultrasonography; IUS: Intestinal ultrasound; TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; NA: Not available.

IUS to predict the risk of surgery

The ileal localization and stricturing and perforating behaviour of CD are well-known risk factors for surgery both in children and in adults. Children with ileal CD requiring surgical resection may have more severe IUS manifestations (such as loss of mural stratification and severe fibrofatty proliferation) associated with both active inflammation and chronic fibrosis than those managed medically[33].

Even in adults, the routine use of IUS in CD patients may identify a subgroup at high risk of surgery, taking into account that nearly half of patients with CD may require surgery within 10 years of diagnosis[1]. Irrespective of the treatment performed, BWT > 7 mm at IUS, altered bowel wall echopattern, and the presence of complications such as fistulas or stenosis are risk factors for intestinal resection over a short period of time[34-36]. In particular, the presence of strictures, fistulae, and abscesses at baseline bowel US seems to predict the need for surgery through 12 mo[14].

The assessment of fibrosis by means of strain elastography may identify patients who are nonresponsive to anti-TNF and need surgery. Orlando et al[29] in a small series of patients, showed that the strain ratio of the thickened bowel wall may predict surgery much better than the degree of its thickening and vascularization and that a strain ratio ≥ 2 before starting anti-TNF was the cut-off value correlated with poor lack of improvement, surgery and worst outcome. Likewise, the lack of improvement or the increase in BWT after the start of treatment is correlated with a high risk of surgery[21,34]. It is debatable whether in selected populations at high risk of surgery, such as CD patients with well-known strictures and fistulas, the features of BWT may suggest the response to treatment and ultimately surgery. In the STRIDENT study, 77 CD patients with a de novo or postoperative anastomotic intestinal stricture with symptoms consistent with chronic or subacute intestinal obstruction were randomly assigned to receive adalimumab alone or combined with thiopurines. IUS at 12 mo showed improvement (> 25%) in BWT in 45% of patients, with no significant difference between the two groups of patients and an overall low risk of surgery, but no predictors of improvement were given[10].

IUS to predict post-surgical recurrence

Several studies and systematic reviews have assessed the role of IUS in postoperative follow-up, showing that a BWT > 3 mm of the anastomosis or neoterminal ileum is an accurate indicator for recurrence[11]. In this regard, prospective studies have shown that the use of PEG solution (SICUS)[37] and colour Doppler or CEUS[38] can increase the sensitivity, albeit with a decrease in specificity in detecting postoperative recurrence at 1 year after surgery. Moreover, both IUS and SICUS, adopting different cut-off levels for bowel thickness (> 5 mm for conventional sonography and > 4 mm for SICUS), can suggest severe endoscopic postoperative recurrence and could accordingly replace endoscopy in postsurgical follow-up[37] (for detection of recurrence).

IUS is accurate not only in detecting postoperative clinical recurrence but also in predicting endoscopic and surgical recurrence. IUS assessment 3 mo after surgery showed high sensitivity in predicting postoperative recurrence at 12 mo, with lower sensitivity[38] but higher specificity than calprotectin[39]. A retrospective study showed that in postoperative CD patients, independent of the time elapsed from earlier surgery, patients with BWT > 3 mm had a doubled risk of surgical recurrence compared with patients with BWT < 3 mm, and that the absolute incidence of new surgical interventions positively correlated with increased BWT[40]. In this respect, the prognostic value of increased BWT, as assessed by IUS several years after surgery, needs further confirmation, and in particular, the usefulness of therapy escalation for these patients remains unconfirmed[12].

Additionally, in CD patients treated with conservative surgery (e.g., strictureplasty or minimal bowel resections), IUS is useful for monitoring the postoperative behaviour of BWT and can provide prognostic information: US detection of unchanged or worsened wall thickness 6 mo after surgery or the postoperative persistence of wall thickness > 6 mm is predictive of a high risk of recurrence[41].

In this subset of patients, the estimated 5-year survival probability of symptomatic CD recurrence was 90% and 33%, respectively, for unchanged/worsened BWT vs improved BWT at 12 mo after surgery. A BWT > 6.0 mm at 12 mo after surgery was directly associated with the risk of CD recurrence. Hence, systematic IUS follow-up of diseased bowel walls after conservative surgery seems to allow the early identification of patients at high risk of clinical/surgical recurrence[42].

Clinical remission

In CD patients, bowel wall changes such as increased BWT and vascularization may persist after therapy and despite clinical remission. The meaning and prognostic significance of these IUS findings have been widely investigated. In quiescent CD, increased vascularity, detected either by colour Doppler or CEUS, after treatment may suggest an increased risk of relapse[21,43,44].

Vascularization and BWT currently represent the main features of sonographic activity scores, and the investigation on prognostic significance of these scores in clinical studies is still ongoing. However, it is clear that normalization of the bowel wall (the so-called TR), namely, a BWT < 3 mm[45] or a more stringent definition such as the combination of BWT < 3 mm, normalization of vascularity and wall stratification, absence of mesenteric fat hypertrophy, node enlargement, or disease complications (i.e., strictures, fistulas)[46,47], is associated with favourable prognostic long-term outcomes[40,43,46,48,49].

Indeed, it has been demonstrated that sonographic remission evaluated after one year of anti-TNF therapy is associated with a longer remission without the need for a therapy change and a reduced need for surgery[21]. In patients with CD in clinical remission, achieving TR is associated with reduced clinical complications, including medication escalation, corticosteroid use, hospitalization, and surgery. When examining clinical complications occurring more than 90 d following IUS, sonographic inflammation remains associated with an increased risk of clinical complications such asmedication escalation, hospitalization, and surgery[46,50,51].

CONCLUSION

IUS is a useful imaging method to assess CD disease activity and can have a prognostic role in predicting response to treatment, disease progression, risk of surgery and risk of postsurgical recurrence. Response to treatment may be predicted by increased BWT and vascularization, reduced elasticity and absence of CD complications. Disease progression or risk of surgery may be predicted by increased BWT, loss of bowel stratification and the presence of CD complications. Postoperative clinical and surgical relapse may be predicted by increased BWT. As more biological therapies become available in the coming years, further prospective trials will be needed to reach definite evidence on IUS predictive value at baseline, to recognize which patients are more likely to respond to a specific therapy and which patients are at high risk of surgery or complications, needing early intensive treatment.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: March 9, 2023

First decision: March 20, 2023

Article in press: May 23, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Iizuka M, Japan; Miyoshi E, Japan S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

Contributor Information

Cristina Manzotti, Gastroenterology Unit, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Milan, L.Sacco University Hospital, Milano 20157, Italy.

Francesco Colombo, Division of General Surgery, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Milan, L.Sacco University Hospital, Milano 20157, Italy. colombo.francesco@asst-fbf-sacco.it.

Tommaso Zurleni, Division of General Surgery, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Milan, L.Sacco University Hospital, Milano 20157, Italy.

Piergiorgio Danelli, Division of General Surgery, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Milan, L.Sacco University Hospital, Milano 20157, Italy.

Giovanni Maconi, Gastroenterology Unit, Department of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Milan, L.Sacco University Hospital, Milano 20157, Italy.

References

- 1.Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1741–1755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Diamond R, Rutgeerts P, Tang LK, Cornillie FJ, Sandborn WJ. Clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein normalisation and mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease in the SONIC trial. Gut. 2014;63:88–95. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pariente B, Cosnes J, Danese S, Sandborn WJ, Lewin M, Fletcher JG, Chowers Y, D’Haens G, Feagan BG, Hibi T, Hommes DW, Irvine EJ, Kamm MA, Loftus EV Jr, Louis E, Michetti P, Munkholm P, Oresland T, Panés J, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Sands BE, Schoelmerich J, Schreiber S, Tilg H, Travis S, van Assche G, Vecchi M, Mary JY, Colombel JF, Lémann M. Development of the Crohn’s disease digestive damage score, the Lémann score. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1415–1422. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farmer RG, Whelan G, Fazio VW. Long-term follow-up of patients with Crohn’s disease. Relationship between the clinical pattern and prognosis. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1818–1825. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Høie O, Stray N, Sauar J, Jahnsen J, Moum B, Lygren I IBSEN Study Group. Clinical course in Crohn’s disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1430–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez-Montpetit E, Ripollés T, Martinez-Pérez MJ, Vizuete J, Martín G, Blanc E. Ultrasound findings of Crohn’s disease: correlation with MR enterography. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2021;46:156–167. doi: 10.1007/s00261-020-02622-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rimola J, Torres J, Kumar S, Taylor SA, Kucharzik T. Recent advances in clinical practice: advances in cross-sectional imaging in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2022;71:2587–2597. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-326562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maconi G, Nylund K, Ripolles T, Calabrese E, Dirks K, Dietrich CF, Hollerweger A, Sporea I, Saftoiu A, Maaser C, Hausken T, Higginson AP, Nürnberg D, Pallotta N, Romanini L, Serra C, Gilja OH. EFSUMB Recommendations and Clinical Guidelines for Intestinal Ultrasound (GIUS) in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Ultraschall Med. 2018;39:304–317. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-125329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dillman JR, Dehkordy SF, Smith EA, DiPietro MA, Sanchez R, DeMatos-Maillard V, Adler J, Zhang B, Trout AT. Defining the ultrasound longitudinal natural history of newly diagnosed pediatric small bowel Crohn disease treated with infliximab and infliximab-azathioprine combination therapy. Pediatr Radiol. 2017;47:924–934. doi: 10.1007/s00247-017-3848-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulberg JD, Wright EK, Holt BA, Hamilton AL, Sutherland TR, Ross AL, Vogrin S, Miller AM, Connell WC, Lust M, Ding NS, Moore GT, Bell SJ, Shelton E, Christensen B, De Cruz P, Rong YJ, Kamm MA. Intensive drug therapy versus standard drug therapy for symptomatic intestinal Crohn’s disease strictures (STRIDENT): an open-label, single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7:318–331. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00393-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calabrese E, Maaser C, Zorzi F, Kannengiesser K, Hanauer SB, Bruining DH, Iacucci M, Maconi G, Novak KL, Panaccione R, Strobel D, Wilson SR, Watanabe M, Pallone F, Ghosh S. Bowel Ultrasonography in the Management of Crohn’s Disease. A Review with Recommendations of an International Panel of Experts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1168–1183. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraquelli M, Castiglione F, Calabrese E, Maconi G. Impact of intestinal ultrasound on the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease: how to apply scientific evidence to clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puca P, Del Vecchio LE, Ainora ME, Gasbarrini A, Scaldaferri F, Zocco MA. Role of Multiparametric Intestinal Ultrasound in the Evaluation of Response to Biologic Therapy in Adults with Crohn’s Disease. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12081991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allocca M, Craviotto V, Bonovas S, Furfaro F, Zilli A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Fiorino G, Danese S. Predictive Value of Bowel Ultrasound in Crohn’s Disease: A 12-Month Prospective Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:e723–e740. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang X, Li X. Predictive Value of Bowel Ultrasound in Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:e345–e346. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maconi G, Sampietro GM, Sartani A, Bianchi Porro G. Bowel ultrasound in Crohn’s disease: surgical perspective. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Voogd F, Bots S, Gecse K, Gilja OH, D’Haens G, Nylund K. Intestinal Ultrasound Early on in Treatment Follow-up Predicts Endoscopic Response to Anti-TNFα Treatment in Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:1598–1608. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albshesh A, Ungar B, Ben-Horin S, Eliakim R, Kopylov U, Carter D. Terminal Ileum Thickness During Maintenance Therapy Is a Predictive Marker of the Outcome of Infliximab Therapy in Crohn Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:1619–1625. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izaa219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YJ, Chen BL, Liang MJ, Chen SL, Li XH, Qiu Y, Pang LL, Xia QQ, He Y, Zeng ZR, Chen MH, Mao R, Xie XY. Longitudinal Bowel Behavior Assessed by Bowel Ultrasound to Predict Early Response to Anti-TNF Therapy in Patients With Crohn’s Disease: A Pilot Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28:S67–S75. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izab353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Les A, Iacob R, Saizu R, Cotruta B, Saizu AI, Iacob S, Gheorghe L, Gheorghe C. Bowel Ultrasound: a Non-invasive, Easy to Use Method to Predict the Need to Intensify Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2021;30:462–469. doi: 10.15403/jgld-3726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ripollés T, Paredes JM, Martínez-Pérez MJ, Rimola J, Jauregui-Amezaga A, Bouzas R, Martin G, Moreno-Osset E. Ultrasonographic Changes at 12 Weeks of Anti-TNF Drugs Predict 1-year Sonographic Response and Clinical Outcome in Crohn’s Disease: A Multicenter Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2465–2473. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith RL, Taylor KM, Friedman AB, Gibson DJ, Con D, Gibson PR. Early sonographic response to a new medical therapy is associated with future treatment response or failure in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;34:613–621. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zorzi F, Ghosh S, Chiaramonte C, Lolli E, Ventura M, Onali S, De Cristofaro E, Fantini MC, Biancone L, Monteleone G, Calabrese E. Response Assessed by Ultrasonography as Target of Biological Treatment for Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:2030–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoffmann T, Fusco S, Blumenstock G, Sadik S, Malek NP, Froehlich E. Evaluation of bowel wall thickness by ultrasound as early diagnostic tool for therapeutic response in Crohn’s disease patients treated with ustekinumab. Z Gastroenterol. 2022;60:1212–1220. doi: 10.1055/a-1283-6550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saevik F, Nylund K, Hausken T, Ødegaard S, Gilja OH. Bowel perfusion measured with dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasound predicts treatment outcome in patients with Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:2029–2037. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen W, Lu C, Hirota C, Iacucci M, Ghosh S, Gui X. Smooth Muscle Hyperplasia/Hypertrophy is the Most Prominent Histological Change in Crohn’s Fibrostenosing Bowel Strictures: A Semiquantitative Analysis by Using a Novel Histological Grading Scheme. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:92–104. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quaia E, Sozzi M, Angileri R, Gennari AG, Cova MA. Time-Intensity Curves Obtained after Microbubble Injection Can Be Used to Differentiate Responders from Nonresponders among Patients with Clinically Active Crohn Disease after 6 Weeks of Pharmacologic Treatment. Radiology. 2016;281:606–616. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016152461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pecere S, Holleran G, Ainora ME, Garcovich M, Scaldaferri F, Gasbarrini A, Zocco MA. Usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:761–767. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orlando S, Fraquelli M, Coletta M, Branchi F, Magarotto A, Conti CB, Mazza S, Conte D, Basilisco G, Caprioli F. Ultrasound Elasticity Imaging Predicts Therapeutic Outcomes of Patients With Crohn’s Disease Treated With Anti-Tumour Necrosis Factor Antibodies. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:63–70. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maconi G, Di Sabatino A, Ardizzone S, Greco S, Colombo E, Russo A, Cassinotti A, Casini V, Corazza GR, Bianchi Porro G. Prevalence and clinical significance of sonographic detection of enlarged regional lymph nodes in Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1328–1333. doi: 10.1080/00365510510025746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kucharzik T, Wittig BM, Helwig U, Börner N, Rössler A, Rath S, Maaser C TRUST study group. Use of Intestinal Ultrasound to Monitor Crohn’s Disease Activity. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:535–542.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Helwig U, Fischer I, Hammer L, Kolterer S, Rath S, Maaser C, Kucharzik T. Transmural Response and Transmural Healing Defined by Intestinal Ultrasound: New Potential Therapeutic Targets? J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:57–67. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbaum DG, Conrad MA, Biko DM, Ruchelli ED, Kelsen JR, Anupindi SA. Ultrasound and MRI predictors of surgical bowel resection in pediatric Crohn disease. Pediatr Radiol. 2017;47:55–64. doi: 10.1007/s00247-016-3704-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Castiglione F, de Sio I, Cozzolino A, Rispo A, Manguso F, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Di Girolamo E, Castellano L, Ciacci C, Mazzacca G. Bowel wall thickness at abdominal ultrasound and the one-year-risk of surgery in patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1977–1983. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rigazio C, Ercole E, Laudi C, Daperno M, Lavagna A, Crocella L, Bertolino F, Viganò L, Sostegni R, Pera A, Rocca R. Abdominal bowel ultrasound can predict the risk of surgery in Crohn’s disease: proposal of an ultrasonographic score. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:585–593. doi: 10.1080/00365520802705992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunihiro K, Hata J, Manabe N, Mitsuoka Y, Tanaka S, Haruma K, Chayama K. Predicting the need for surgery in Crohn’s disease with contrast harmonic ultrasound. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:577–585. doi: 10.1080/00365520601002716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Castiglione F, Bucci L, Pesce G, De Palma GD, Camera L, Cipolletta F, Testa A, Diaferia M, Rispo A. Oral contrast-enhanced sonography for the diagnosis and grading of postsurgical recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1240–1245. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paredes JM, Ripollés T, Cortés X, Moreno N, Martínez MJ, Bustamante-Balén M, Delgado F, Moreno-Osset E. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography: usefulness in the assessment of postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Orlando A, Modesto I, Castiglione F, Scala L, Scimeca D, Rispo A, Teresi S, Mocciaro F, Criscuoli V, Marrone C, Platania P, De Falco T, Maisano S, Nicoli N, Cottone M. The role of calprotectin in predicting endoscopic post-surgical recurrence in asymptomatic Crohn’s disease: a comparison with ultrasound. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2006;10:17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cammarota T, Sarno A, Robotti D, Bonenti G, Debani P, Versace K, Astegiano M, Pera A. US evaluation of patients affected by IBD: how to do it, methods and findings. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maconi G, Sampietro GM, Cristaldi M, Danelli PG, Russo A, Bianchi Porro G, Taschieri AM. Preoperative characteristics and postoperative behavior of bowel wall on risk of recurrence after conservative surgery in Crohn’s disease: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2001;233:345–352. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parente F, Sampietro GM, Molteni M, Greco S, Anderloni A, Sposito C, Danelli PG, Taschieri AM, Gallus S, Bianchi Porro G. Behaviour of the bowel wall during the first year after surgery is a strong predictor of symptomatic recurrence of Crohn’s disease: a prospective study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:959–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ripollés T, Martínez MJ, Barrachina MM. Crohn’s disease and color Doppler sonography: response to treatment and its relationship with long-term prognosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36:267–272. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Di Sabatino A, Fulle I, Ciccocioppo R, Ricevuti L, Tinozzi FP, Tinozzi S, Campani R, Corazza GR. Doppler enhancement after intravenous levovist injection in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:251–257. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zacharopoulou E, Craviotto V, Fiorino G, Furfaro F, Zilli A, Gilardi D, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S, Allocca M. Targeting the gut layers in Crohn’s disease: mucosal or transmural healing? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;14:775–787. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2020.1780914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nardone OM, Calabrese G, Testa A, Caiazzo A, Fierro G, Rispo A, Castiglione F. The Impact of Intestinal Ultrasound on the Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: From Established Facts Toward New Horizons. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:898092. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.898092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kucharzik T, Tielbeek J, Carter D, Taylor SA, Tolan D, Wilkens R, Bryant RV, Hoeffel C, De Kock I, Maaser C, Maconi G, Novak K, Rafaelsen SR, Scharitzer M, Spinelli A, Rimola J. ECCO-ESGAR Topical Review on Optimizing Reporting for Cross-Sectional Imaging in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16:523–543. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma L, Li W, Zhuang N, Yang H, Liu W, Zhou W, Jiang Y, Li J, Zhu Q, Qian J. Comparison of transmural healing and mucosal healing as predictors of positive long-term outcomes in Crohn’s disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211016259. doi: 10.1177/17562848211016259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Geyl S, Guillo L, Laurent V, D’Amico F, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Transmural healing as a therapeutic goal in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:659–667. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaughan R, Tjandra D, Patwardhan A, Mingos N, Gibson R, Boussioutas A, Ardalan Z, Al-Ani A, Gibson PR, Christensen B. Toward transmural healing: Sonographic healing is associated with improved long-term outcomes in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56:84–94. doi: 10.1111/apt.16892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilkens R, Novak KL, Maaser C, Panaccione R, Kucharzik T. Relevance of monitoring transmural disease activity in patients with Crohn’s disease: current status and future perspectives. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211006672. doi: 10.1177/17562848211006672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Calabrese E, Rispo A, Zorzi F, De Cristofaro E, Testa A, Costantino G, Viola A, Bezzio C, Ricci C, Prencipe S, Racchini C, Stefanelli G, Allocca M, Scotto di Santolo S, D’Auria MV, Balestrieri P, Ricchiuti A, Cappello M, Cavallaro F, Guarino AD, Maconi G, Spagnoli A, Monteleone G, Castiglione F. Ultrasonography Tight Control and Monitoring in Crohn’s Disease During Different Biological Therapies: A Multicenter Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:e711–e722. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paredes JM, Moreno N, Latorre P, Ripollés T, Martinez MJ, Vizuete J, Moreno-Osset E. Clinical Impact of Sonographic Transmural Healing After Anti-TNF Antibody Treatment in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64:2600–2606. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05567-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laterza L, Ainora ME, Garcovich M, Galasso L, Poscia A, Di Stasio E, Lupascu A, Riccardi L, Scaldaferri F, Armuzzi A, Rapaccini GL, Gasbarrini A, Pompili M, Zocco MA. Bowel contrast-enhanced ultrasound perfusion imaging in the evaluation of Crohn’s disease patients undergoing anti-TNFα therapy. Dig Liver Dis. 2021;53:729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2020.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ungar B, Ben-Shatach Z, Selinger L, Malik A, Albshesh A, Ben-Horin S, Eliakim R, Kopylov U, Carter D. Lower adalimumab trough levels are associated with higher bowel wall thickness in Crohn’s disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2020;8:167–174. doi: 10.1177/2050640619878974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quaia E, Gennari AG, Cova MA. Early Predictors of the Long-term Response to Therapy in Patients With Crohn Disease Derived From a Time-Intensity Curve Analysis After Microbubble Contrast Agent Injection. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:947–958. doi: 10.1002/jum.14778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Castiglione F, Testa A, Rea M, De Palma GD, Diaferia M, Musto D, Sasso F, Caporaso N, Rispo A. Transmural healing evaluated by bowel sonography in patients with Crohn’s disease on maintenance treatment with biologics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1928–1934. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31829053ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Castiglione F, Mainenti P, Testa A, Imperatore N, De Palma GD, Maurea S, Rea M, Nardone OM, Sanges M, Caporaso N, Rispo A. Cross-sectional evaluation of transmural healing in patients with Crohn’s disease on maintenance treatment with anti-TNF alpha agents. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49:484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castiglione F, Imperatore N, Testa A, De Palma GD, Nardone OM, Pellegrini L, Caporaso N, Rispo A. One-year clinical outcomes with biologics in Crohn’s disease: transmural healing compared with mucosal or no healing. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:1026–1039. doi: 10.1111/apt.15190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kucharzik T, Wilkens R, D’Agostino MA, Maconi G, Le Bars M, Lahaye M, Bravatà I, Nazar M, Ni L, Ercole E, Allocca M, Machková N, de Voogd FAE, Palmela C, Vaughan R, Maaser C STARDUST Intestinal Ultrasound study group. Early Ultrasound Response and Progressive Transmural Remission After Treatment With Ustekinumab in Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:153–163.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miranda A, Gravina AG, Cuomo A, Mucherino C, Sgambato D, Facchiano A, Granata L, Priadko K, Pellegrino R, de Filippo FR, Camera S, Cuomo R, Melina R, D’Onofrio V, Manguso F, Ciacci C, Romano M. Efficacy of ustekinumab in the treatment of patients with Crohn’s disease with failure to previous conventional or biologic therapy: a prospective observational real-life study. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2021;72 doi: 10.26402/jpp.2021.4.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Civitelli F, Nuti F, Oliva S, Messina L, La Torre G, Viola F, Cucchiara S, Aloi M. Looking Beyond Mucosal Healing: Effect of Biologic Therapy on Transmural Healing in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:2418–2424. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paredes JM, Ripollés T, Cortés X, Martínez MJ, Barrachina M, Gómez F, Moreno-Osset E. Abdominal sonographic changes after antibody to tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) alpha therapy in Crohn’s Disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:404–410. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0759-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaughan R, Murphy E, Nalder M, Gibson RN, Ardalan Z, Boussioutas A, Christensen B. Infliximab Trough Levels Are Associated With Transmural Sonographic Healing in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1093/ibd/izac186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Han ZM, Elodie WH, Yan LH, Xu PC, Zhao XM, Zhi FC. Correlation Between Ultrasonographic Response and Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Drug Levels in Crohn’s disease. Ther Drug Monit. 2022;44:659–664. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dolinger MT, Choi JJ, Phan BL, Rosenberg HK, Rowland J, Dubinsky MC. Use of Small Bowel Ultrasound to Predict Response to Infliximab Induction in Pediatric Crohn’s Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:429–432. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]